Christianity in the 6th century on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In 6th-century Christianity, Roman Emperor

In 6th-century Christianity, Roman Emperor

Benedict of Nursia is the most influential of Western monks. He was educated in Rome but soon sought the life of a hermit in a cave at Subiaco, outside the city. He then attracted followers with whom he founded the monastery of

Benedict of Nursia is the most influential of Western monks. He was educated in Rome but soon sought the life of a hermit in a cave at Subiaco, outside the city. He then attracted followers with whom he founded the monastery of

The largely Christian Gallo-Roman inhabitants of

The largely Christian Gallo-Roman inhabitants of  In the polytheistic Germanic tradition it was even possible to worship Jesus next to the native gods like

In the polytheistic Germanic tradition it was even possible to worship Jesus next to the native gods like

Schaff's ''The Seven Ecumenical Councils

{{DEFAULTSORT:Christianity In The 6th Century 06 06

In 6th-century Christianity, Roman Emperor

In 6th-century Christianity, Roman Emperor Justinian

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

launched a military campaign in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

to reclaim the western provinces from the Germans, starting with North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

and proceeding to Italy. Though he was temporarily successful in recapturing much of the western Mediterranean he destroyed the urban centers and permanently ruined the economies in much of the West. Rome and other cities were abandoned. In the coming centuries the Western Church

Western Christianity is one of two sub-divisions of Christianity (Eastern Christianity being the other). Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the Old Catholic ...

, as virtually the only surviving Roman institution in the West, became the only remaining link to Greek culture and civilization.

In the East, Roman imperial rule continued through the period historians now call the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. Even in the West, where imperial political control gradually declined, distinctly Roman culture continued long afterwards; thus historians today prefer to speak of a "transformation of the Roman world" rather than a "Fall of Rome

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vas ...

." The advent of the Early Middle Ages was a gradual and often localised process whereby, in the West, rural areas became power centres whilst urban areas declined. Although the greater number of Christians remained in the East, the developments in the West would set the stage for major developments in the Christian world

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

during the later Middle Ages.

Second Council of Constantinople

Prior to the Second Council of Constantinople was a prolonged controversy over the treatment of three subjects, all considered sympathetic to Nestorianism, theheresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

that there are two separate persons in the Incarnation of Christ. Emperor Justinian condemned the Three Chapters, hoping to appeal to monophysite Christians with his anti-Nestorian zeal. Monophysites believe that in the Incarnate Christ there is one nature, not two. Eastern patriarchs supported the emperor, but in the West his interference was resented, and Pope Vigilius

Pope Vigilius (died 7 June 555) was the bishop of Rome from 29 March 537 to his death. He is considered the first pope of the Byzantine papacy. Born into Roman aristocracy, Vigilius served as a deacon and papal ''apocrisiarius'' in Constantino ...

resisted his edict on the grounds that it opposed the Chalcedonian decrees. Justinian's policy was in fact an attack on Antiochene theology and the decisions of Chalcedon. The pope assented and condemned the Three Chapters, but protests in the West caused him to retract his condemnation. The emperor called the Second Council of Constantinople to resolve the controversy.

The council met in Constantinople in 553, and it has since become recognized as the fifth of the

first seven Ecumenical Councils. The council condemned certain Nestorian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

writings and authors. This move was instigated by Emperor Justinian in an effort to conciliate the monophysite Christians, it was opposed in the West, and the popes' acceptance of the council caused a major schism."Constantinople, Second Council of." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

The council interpreted the decrees of Chalcedon

Chalcedon ( or ; , sometimes transliterated as ''Chalkedon'') was an ancient maritime town of Bithynia, in Asia Minor. It was located almost directly opposite Byzantium, south of Scutari (modern Üsküdar) and it is now a district of the cit ...

and further explained the relationship of the two natures of Jesus; it also condemned the teachings of Origen

Origen of Alexandria, ''Ōrigénēs''; Origen's Greek name ''Ōrigénēs'' () probably means "child of Horus" (from , "Horus", and , "born"). ( 185 – 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an early Christian scholar, ascetic, and theo ...

on the pre-existence

Pre-existence, preexistence, beforelife, or premortal existence, is the belief that each individual human soul existed before mortal conception, and at some point before birth enters or is placed into the body. Concepts of pre-existence can enc ...

of the soul, and Apocatastasis

In theology, apocatastasis () is the restoration of creation to a condition of perfection. In Christianity, it is a form of Christian universalism that includes the ultimate salvation of everyone—including the damned in hell and the devil. The ...

.

The council, attended mostly by Eastern bishops, condemned the Three Chapters and, indirectly, the Pope Vigilius

Pope Vigilius (died 7 June 555) was the bishop of Rome from 29 March 537 to his death. He is considered the first pope of the Byzantine papacy. Born into Roman aristocracy, Vigilius served as a deacon and papal ''apocrisiarius'' in Constantino ...

."Three Chapters." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005 It also affirmed the East's intention to remain in communion with Rome.

Vigilius declared his submission to the council, as did his successor, Pelagius I. The council was not immediately recognized as ecumenical in the West, and the churches of Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

and Aquileia even broke off communion with Rome over this issue. The schism was not repaired until the late 6th century for Milan and the late 7th century for Aquileia.

Eastern Church

In the 530s the second Church of the Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia ( 'Holy Wisdom'; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque ( tr, Ayasofya-i Kebir Cami-i Şerifi), is a mosque and major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. The cathedral was originally built as a Greek Ortho ...

) was built in Constantinople under Justinian. The first church was destroyed during the Nika riots

The Nika riots ( el, Στάσις τοῦ Νίκα, translit=Stásis toû Níka), Nika revolt or Nika sedition took place against Byzantine Emperor Justinian I in Constantinople over the course of a week in 532 AD. They are often regarded as the ...

. The second Hagia Sophia became the center of the ecclesiastical community for the rulers of the Roman Empire or, as it is now called, the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

.

Western theology before the Carolingian Empire

When the Western Roman Empire fragmented under the impact of various 'barbarian' invasions, the Empire-wide intellectual culture that had underpinned late Patristic theology had its interconnections cut. Theology tended to become more localised, more diverse, more fragmented. The classic Christianity preserved in Italy by men likeBoethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480 – 524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul, ''magister officiorum'', historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the tr ...

and Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Roman statesman, renowned scholar of antiquity, and writer serving in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senator'' ...

was different from the vigorous Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages

* Francia, a post-Roman state in France and Germany

* East Francia, the successor state to Francia in Germany ...

Christianity documented by Gregory of Tours, which was different from the Christianity that flourished in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

and Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

. Throughout this period, theology tended to be a more monastic

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religion, religious way of life in which one renounces world (theology), worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic ...

affair, flourishing in monastic havens where the conditions and resources for theological learning could be maintained.

Important writers include:

* Caesarius of Arles

Caesarius of Arles ( la, Caesarius Arelatensis; 468/470 27 August 542 AD), sometimes called "of Chalon" (''Cabillonensis'' or ''Cabellinensis'') from his birthplace Chalon-sur-Saône, was the foremost ecclesiastic of his generation in Merovingia ...

(c.468-542)

* Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480 – 524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul, ''magister officiorum'', historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the tr ...

(480-524)

* Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Roman statesman, renowned scholar of antiquity, and writer serving in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senator'' ...

(c.480-c.585)

* Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I ( la, Gregorius I; – 12 March 604), commonly known as Saint Gregory the Great, was the bishop of Rome from 3 September 590 to his death. He is known for instigating the first recorded large-scale mission from Rome, the Gregor ...

(c.540-604)

Gregory the Great

Saint Gregory I the Great waspope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

from September 3, 590 until his death. He is also known as Gregorius Dialogus (''Gregory the Dialogist'') in Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or "canonical") ...

because of the '' Dialogues'' he wrote. He was the first of the popes from a monastic background. Gregory is a Doctor of the Church and one of the four great Latin Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical per ...

of the Church. Of all popes, Gregory I had the most influence on the early medieval

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

church.

Monasticism

Benedict

Benedict of Nursia is the most influential of Western monks. He was educated in Rome but soon sought the life of a hermit in a cave at Subiaco, outside the city. He then attracted followers with whom he founded the monastery of

Benedict of Nursia is the most influential of Western monks. He was educated in Rome but soon sought the life of a hermit in a cave at Subiaco, outside the city. He then attracted followers with whom he founded the monastery of Monte Cassino

Monte Cassino (today usually spelled Montecassino) is a rocky hill about southeast of Rome, in the Latin Valley, Italy, west of Cassino and at an elevation of . Site of the Roman town of Casinum, it is widely known for its abbey, the first ho ...

around 520, between Rome and Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

. In 530, he wrote his '' Rule of St Benedict'' as a practical guide for monastic community life. Its message spread to monasteries throughout Europe.Woods, ''How the Church Built Western Civilization'' (2005), p. 27 Monasteries became major conduits of civilization, preserving craft and artistic skills while maintaining intellectual culture within their schools, scriptoria

Scriptorium (), literally "a place for writing", is commonly used to refer to a room in medieval European monasteries devoted to the writing, copying and illuminating of manuscripts commonly handled by monastic scribes.

However, lay scribes and ...

and libraries. They functioned as agricultural, economic and production centers as well as a focus for spiritual life.Le Goff, ''Medieval Civilization'' (1964), p. 120

During this period the Visigoths and Lombards moved away from Arianism for Nicene Christianity

The original Nicene Creed (; grc-gre, Σύμβολον τῆς Νικαίας; la, Symbolum Nicaenum) was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. In 381, it was amended at the First Council of Constantinople. The amended form is ...

.Le Goff, ''Medieval Civilization'' (1964), p. 21 Pope Gregory I played a notable role in these conversions and dramatically reformed the ecclesiastical structures and administration which then launched renewed missionary efforts.Duffy, ''Saints and Sinners'' (1997), pp. 50–52

Little is known about the origins of the first important monastic rule (''Regula'') in Western Europe, the anonymous Rule of the Master

The ''Regula Magistri'' or Rule of the Master is an anonymous sixth-century collection of monastic precepts. The text of the ''Rule of the Master'' is found in the ''Concordia Regularum'' of Benedict of Aniane, who gave it its name.

History

The ...

(''Regula magistri''), which was written somewhere south of Rome around 500. The rule adds legalistic elements not found in earlier rules, defining the activities of the monastery, its officers, and their responsibilities in great detail.

Ireland

Irish monasticism maintained the model of a monastic community while, likeJohn Cassian

John Cassian, also known as John the Ascetic and John Cassian the Roman ( la, Ioannes Eremita Cassianus, ''Ioannus Cassianus'', or ''Ioannes Massiliensis''; – ), was a Christian monk and theologian celebrated in both the Western and Eastern c ...

, marking the contemplative life of the hermit as the highest form of monasticism. Saints' lives frequently tell of monks (and abbots) departing some distance from the monastery to live in isolation from the community.

Irish monastic rules specify a stern life of prayer and discipline in which prayer, poverty, and obedience are the central themes. Yet Irish monks did not fear pagan learning. Irish monks needed to learn Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, which was the language of the Church. Thus they read Latin texts, both spiritual and secular. By the end of the 7th century, Irish monastic school

Monastic schools ( la, Scholae monasticae) were, along with cathedral schools, the most important institutions of higher learning in the Latin West from the early Middle Ages until the 12th century. Since Cassiodorus's educational program, the st ...

s were attracting students from England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and from Europe. Irish monasticism spread widely, first to Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

and Northern England

Northern England, also known as the North of England, the North Country, or simply the North, is the northern area of England. It broadly corresponds to the former borders of Angle Northumbria, the Anglo-Scandinavian Kingdom of Jorvik, and the ...

, then to Gaul and Italy. Columba and his followers established monasteries at Bangor, on the northeastern coast of Ireland, at Iona, an island north-west of Scotland, and at Lindisfarne, which was founded by Aidan, an Irish monk from Iona, at the request of King Oswald of Northumbria.

Columbanus, an abbot from a Leinster noble family, traveled to Gaul in the late 6th century with twelve companions. Columbanus and his followers spread the Irish model of monastic institutions established by noble families to the continent. A whole series of new rural monastic foundations on great rural estates under Irish influence sprang up, starting with Columbanus's foundations of Fontaines and Luxeuil

Luxeuil-les-Bains () is a commune in the Haute-Saône department in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in eastern France.

History

Luxeuil (sometimes rendered Luxeu in older texts) was the Roman Luxovium and contained many fine buildings ...

, sponsored by the Frankish King Childebert II

Childebert II (c.570–596) was the Merovingian king of Austrasia (which included Provence at the time) from 575 until his death in March 596, as the only son of Sigebert I and Brunhilda of Austrasia; and the king of Burgundy from 592 to his ...

. After Childebert's death Columbanus traveled east to Metz, where Theudebert II allowed him to establish a new monastery among the semi-pagan Alemanni in what is now Switzerland. One of Columbanus' followers founded the monastery of St. Gall on the shores of Lake Constance, while Columbanus continued onward across the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Swi ...

to the kingdom of the Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the '' History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 an ...

in Italy. There King Agilulf

Agilulf ( 555 – April 616), called ''the Thuringian'' and nicknamed ''Ago'', was a duke of Turin and king of the Lombards from 591 until his death.

A relative of his predecessor Authari, Agilulf was of Thuringian origin and belonged to the A ...

and his wife Theodolinda

Theodelinda also spelled ''Theudelinde'' ( 570–628 AD), was a queen of the Lombards by marriage to two consecutive Lombard rulers, Autari and then Agilulf, and regent of Lombardia during the minority of her son Adaloald, and co-regent when ...

granted Columbanus land in the mountains between Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

and Milan, where he established the monastery of Bobbio

Bobbio ( Bobbiese: ; lij, Bêubbi; la, Bobium) is a small town and commune in the province of Piacenza in Emilia-Romagna, northern Italy. It is located in the Trebbia River valley southwest of the town Piacenza. There is also an abbey and a di ...

.

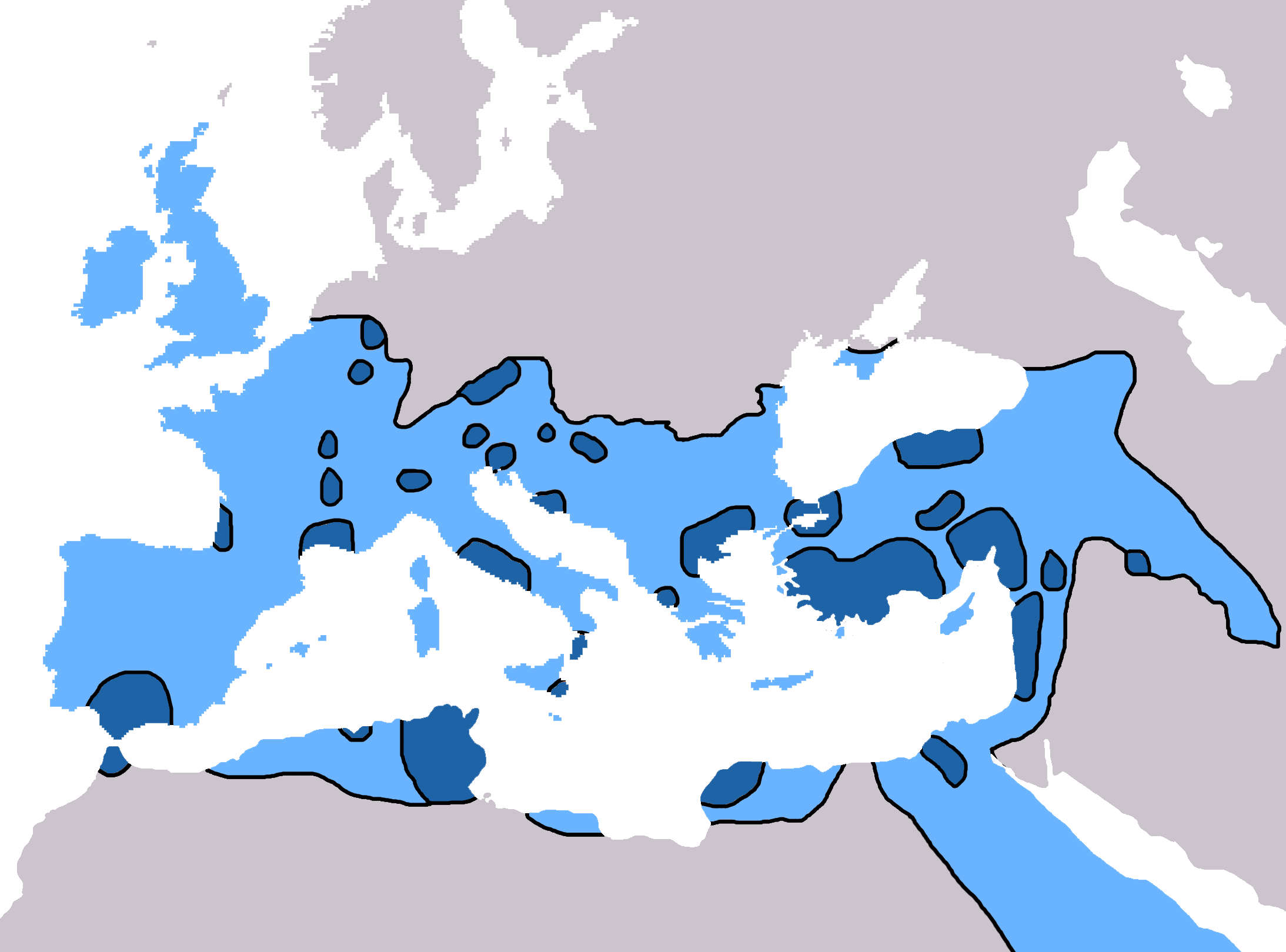

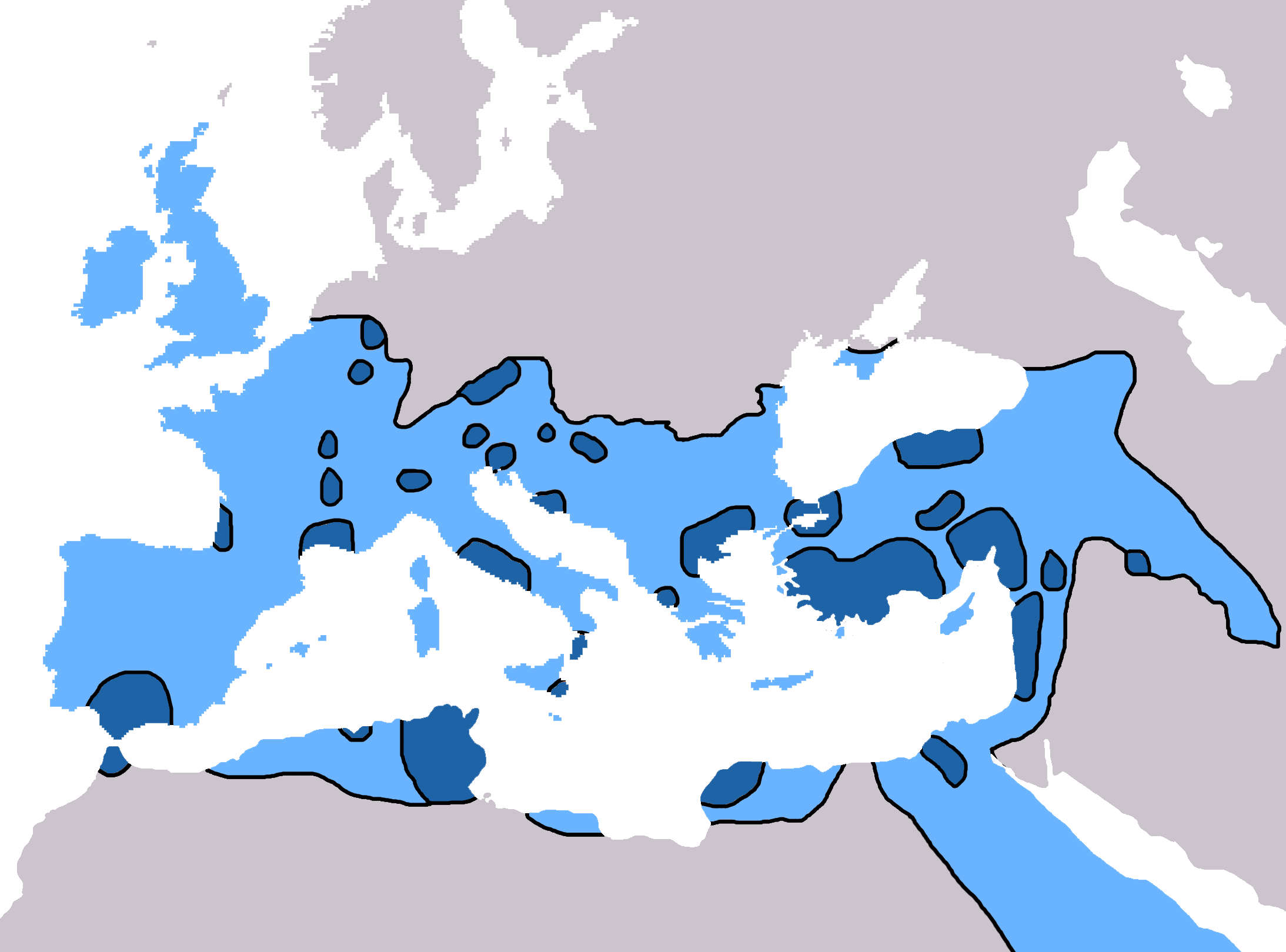

Spread of Christianity

As the political boundaries of the Western Roman Empire diminished and then collapsed, Christianity spread beyond the old borders of the empire and into lands that had never been Romanised. TheLombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the '' History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 an ...

adopted Nicene Christianity as they entered Italy.

Irish missionaries

Although Ireland had never been part of the Roman Empire, Christianity had come there and developed, largely independently from Celtic Christianity. Christianity spread fromRoman Britain

Roman Britain was the period in classical antiquity when large parts of the island of Great Britain were under occupation by the Roman Empire. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410. During that time, the territory conquered wa ...

to Ireland, especially aided by the missionary activity of Saint Patrick. Patrick had been captured into slavery in Ireland, and following his escape and later consecration as bishop, he returned to the isle to bring them the Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words a ...

.

The Irish monks had developed a concept of ''peregrinatio''. This essentially meant that a monk would leave the monastery and his Christian country to proselytize among the heathens, as self-chosen punishment for his sins. Soon, Irish missionaries such as Columba and Columbanus spread this Christianity, with its distinctively Irish features, to Scotland and the continent. From 590 onwards Irish missionaries were active in Gaul, Scotland, Wales and England.

Anglo-Saxon Britain

Although southernBritain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

had been a Roman province, in 407 the imperial legions left the isle, and the Roman elite followed. Some time later that century, various barbarian tribes went from raiding and pillaging the island to settling and invading. These tribes are referred to as the "Anglo-Saxons", predecessors of the English. They were entirely pagan, having never been part of the empire, and although they experienced Christian influence from the surrounding peoples, they were converted by the mission of St. Augustine sent by Pope Gregory I.

Franks

The largely Christian Gallo-Roman inhabitants of

The largely Christian Gallo-Roman inhabitants of Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

(modern France) were overrun by Germanic Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

in the early 5th century. The native inhabitants were persecuted until the Frankish King Clovis I converted from paganism to Nicene Christianity in 496. Clovis insisted that his fellow nobles follow suit, strengthening his newly established kingdom by uniting the faith of the rulers with that of the ruled.

The Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and e ...

underwent gradual Christianization in the course of the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

, resulting in a unique form of Christianity known as Germanic Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global populati ...

. The East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fac ...

and West Germanic tribes were the first to convert through various means. However, it was not until the 12th century that the North Germanic peoples had Christianized.

In the polytheistic Germanic tradition it was even possible to worship Jesus next to the native gods like

In the polytheistic Germanic tradition it was even possible to worship Jesus next to the native gods like Wodan

Odin (; from non, Óðinn, ) is a widely revered god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, victor ...

and Thor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, an ...

. Before a battle, a pagan military leader might pray to Jesus for victory, instead of Odin, if he expected more help from the Christian God. Clovis had done that before a battle against one of the kings of the Alamanni, and had thus attributed his victory to Jesus. Such utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charac ...

thoughts were the basis of most conversions of rulers during this period.Padberg, Lutz v. (1998), p.48 The Christianization of the Franks lay the foundation for the further Christianization of the Germanic peoples.

Arabia

Cosmas Indicopleustes

Cosmas Indicopleustes ( grc-x-koine, Κοσμᾶς Ἰνδικοπλεύστης, lit=Cosmas who sailed to India; also known as Cosmas the Monk) was a Greek merchant and later hermit from Alexandria of Egypt. He was a 6th-century traveller who ma ...

, navigator and geographer of the 6th century, wrote about Christians, bishops, monks, and martyrs in Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

and among the Himyarites

The Himyarite Kingdom ( ar, مملكة حِمْيَر, Mamlakat Ḥimyar, he, ממלכת חִמְיָר), or Himyar ( ar, حِمْيَر, ''Ḥimyar'', / 𐩹𐩧𐩺𐩵𐩬) ( fl. 110 BCE–520s CE), historically referred to as the Homerit ...

. In the 5th century a merchant from Yemen was converted in Hira Hira may refer to:

Places

* Cave of Hira, a cave associated with Muhammad

*Al-Hirah, an ancient Arab city in Iraq

** Battle of Hira, 633AD, between the Sassanians and the Rashidun Caliphate

*Hira Mountains, Japan

* Hira, New Zealand, settlement no ...

, in the northeast, and upon his return led many to Christ.

Tibet

It is unclear when Christianity reachedTibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa, Taman ...

, but it seems likely that it had arrived there by the 6th century. The ancient territory of the Tibetans

The Tibetan people (; ) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Tibet. Their current population is estimated to be around 6.7 million. In addition to the majority living in Tibet Autonomous Region of China, significant numbers of Tibetans liv ...

stretched farther west and north than the present-day Tibet, and they had many links with the Turkic and Mongolian tribes of Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

. It seems likely that Christianity entered the Tibetan world around 549, the time of a remarkable conversion of the White Huns. A strong church existed in Tibet by the 8th century.

Carved into a large boulder at Tankse, Ladakh

Ladakh () is a region administered by India as a union territory which constitutes a part of the larger Kashmir region and has been the subject of dispute between India, Pakistan, and China since 1947. (subscription required) Quote: "Jammu ...

, once part of Tibet but now in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, are three crosses and some inscriptions. These inscriptions are of 19th century. The rock dominates the entrance to the town, on one of the main ancient trade routes between Lhasa

Lhasa (; Lhasa dialect: ; bo, text=ལྷ་ས, translation=Place of Gods) is the urban center of the prefecture-level Lhasa City and the administrative capital of Tibet Autonomous Region in Southwest China. The inner urban area of Lhas ...

and Bactria. The crosses are clearly of the Church of the East, and one of the words, written in Sogdian, appears to be "Jesus". Another inscription in Sogdian reads, "In the year 210 came Nosfarn from Samarkhand

fa, سمرقند

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from the top:Registan square, Shah-i-Zinda necropolis, Bibi-Khanym Mosque, view inside Shah-i-Zind ...

as emissary to the Khan of Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa, Taman ...

". It is possible that the inscriptions were not related to the crosses, but even on their own the crosses bear testimony to the power and influence of Christianity in that area.

Timeline

See also

*History of Christianity

The history of Christianity concerns the Christianity, Christian religion, Christendom, Christian countries, and the Christians with their various Christian denomination, denominations, from the Christianity in the 1st century, 1st century ...

* History of the Roman Catholic Church

*History of the Eastern Orthodox Church

The History of the Eastern Orthodox Church is the formation, events, and transformation of the Eastern Orthodox Church through time.

According to the Eastern Orthodox tradition the history of the Eastern Orthodox Church is traced back to Jesus ...

*History of Christian theology

The doctrine of the Trinity, considered the core of Christian theology by ''Trinitarians'', is the result of continuous exploration by the church of the biblical data, thrashed out in debate and treatises, eventually formulated at the First Cou ...

*History of Oriental Orthodoxy

Oriental Orthodoxy is the communion of Eastern Christian Churches that recognize only three ecumenical councils—the First Council of Nicaea, the First Council of Constantinople and the Council of Ephesus. They reject the dogmatic definitions of ...

* Church Fathers

*List of Church Fathers

The following is a list of Christian Church Fathers. Roman Catholics generally regard the Patristic period to have closed with the death of John of Damascus, a Doctor of the Church, in 749. However, Orthodox Christians believe that the Patri ...

*Christian monasticism

Christian monasticism is the devotional practice of Christians who live ascetic and typically cloistered lives that are dedicated to Christian worship. It began to develop early in the history of the Christian Church, modeled upon scriptural ...

* Patristics

*Development of the New Testament canon

The canon of the New Testament is the set of books many modern Christians regard as divinely inspired and constituting the New Testament of the Christian Bible. For historical Christians, canonization was based on whether the material was fr ...

*Christianization

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

* History of Calvinist-Arminian debate

*Timeline of Christianity

The purpose of this timeline is to give a detailed account of Christianity from the beginning of the current era ( AD) to the present. Question marks ('?') on dates indicate approximate dates.

The year one is the first year in the ''Christia ...

*Timeline of Christian missions

This timeline of Christian missions chronicles the global expansion of Christianity through a listing of the most significant missionary outreach events.

Apostolic Age

Earliest dates must all be considered approximate

* 33 – Great Commissi ...

* Timeline of the Roman Catholic Church

*Chronological list of saints in the 6th century

A list of people, who died during the 6th century, who have received recognition as Saints (through canonization) from the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian churc ...

*Transformation of the Roman World Transformation of the Roman World was a 5-year scientific programme, during the years 1992 to 1997, founded via the European Science Foundation.

The research project was to investigate the societal transformation taking place in Europe in the perio ...

Notes and references

Further reading

* Pelikan, Jaroslav Jan. ''The Christian Tradition: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600)''. University of Chicago Press (1975). . * Lawrence, C. H. ''Medieval Monasticism''. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2001. *Trombley, Frank R., 1995. ''Hellenic Religion and Christianization c. 370-529'' (in series ''Religions in the Graeco-Roman World'') (Brill) *Fletcher, Richard, ''The Conversion of Europe. From Paganism to Christianity 371-1386 AD.'' London 1997. * Eusebius, ''Ecclesiastical History

__NOTOC__

Church history or ecclesiastical history as an academic discipline studies the history of Christianity and the way the Christian Church has developed since its inception.

Henry Melvill Gwatkin defined church history as "the spiritua ...

'', book 1, chp.19

* Socrates, ''Ecclesiastical History'', book 3, chp. 1

* Mingana, ''The Early Spread of Christianity in Central Asia and the Far East'', pp. 300.

* A.C. Moule, ''Christians in China Before The year 1550'', pp. 19–26

* P.Y. Saeki, ''The Nestorian Documents and Relics in China'' and ''The Nestorian Monument in China'', pp. 27–52

* Philostorgius

Philostorgius ( grc-gre, Φιλοστόργιος; 368 – c. 439 AD) was an Anomoean Church historian of the 4th and 5th centuries.

Very little information about his life is available. He was born in Borissus, Cappadocia to Eulampia and Car ...

, ''Ecclesiastical History''.

External links

Schaff's ''The Seven Ecumenical Councils

{{DEFAULTSORT:Christianity In The 6th Century 06 06