Christianity in the 16th century on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In 16th-century Christianity,

In 16th-century Christianity,

The

The

Since that time, the term has been used in many different senses, but most often as a general term refers to

"Martin Luther"

''The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge'', New York, London, Funk and Wagnalls Co., 1908–1914; Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1951, 71. This early portion of Luther's career was one of his most creative and productive. Three of his best known works were published in 1520: ''

Renaissance and Reformation by William Gilbert. Four years later, at the Diet of Västerås, the king succeeded in forcing the diet to accept his dominion over the national church. The king was given possession of all church property, church appointments required royal approval, the clergy were subject to the civil law, and the "pure Word of God" was to be preached in the churches and taught in the schools—effectively granting official sanction to Lutheran ideas. Under the reign of

Protestantism also spread from the German lands into France, where the Protestants were known as ''

Protestantism also spread from the German lands into France, where the Protestants were known as ''

Чин венчания на царство Ивана IV Васильевича. Российский государственный архив древних актов. Ф. 135. Древлехранилище. Отд. IV. Рубр. I. № 1. Л. 1-46

/ref> The growing might of the Russian state contributed also to the growing authority of the

Schaff's ''The Seven Ecumenical Councils''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Christianity In The 16th Century 16 16

Protestantism

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

came to the forefront and marked a significant change in the Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

world.

Age of Discovery

During the age of discovery the babyRoman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

established a number of missions in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

and other colonies in order to spread Christianity in the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

and to convert the indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

. At the same time, missionaries such as Francis Xavier

Francis Xavier (born Francisco de Jasso y Azpilicueta; Latin: ''Franciscus Xaverius''; Basque: ''Frantzisko Xabierkoa''; French: ''François Xavier''; Spanish: ''Francisco Javier''; Portuguese: ''Francisco Xavier''; 7 April 15063 December ...

as well as other Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

, Augustinians

Augustinians are members of Christian religious orders that follow the Rule of Saint Augustine, written in about 400 AD by Augustine of Hippo. There are two distinct types of Augustinians in Catholic religious orders dating back to the 12th–1 ...

, Franciscans

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

and Dominicans were moving into Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

and the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The t ...

. Under the Padroado

The ''Padroado'' (, "patronage") was an arrangement between the Holy See and the Kingdom of Portugal and later the Portuguese Republic, through a series of concordats by which the Holy See delegated the administration of the local churches and gr ...

treaty with the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

, by which the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Vatican City, the city-state ruled by the pope in Rome, including St. Peter's Basilica, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museum

The Holy See

* The Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church and sovereign entity recognized ...

delegated to the kings the administration of the local churches, the Portuguese sent missions into Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, Brasil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area an ...

and Asia. While some of these missions were associated with imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic powe ...

and oppression, others (notably Matteo Ricci

Matteo Ricci, SJ (; la, Mattheus Riccius; 6 October 1552 – 11 May 1610), was an Italian Jesuit priest and one of the founding figures of the Jesuit China missions. He created the , a 1602 map of the world written in Chinese characters. ...

's Jesuit China missions

The history of the missions of the Jesuits in China is part of the history of relations between China and the Western world. The missionary efforts and other work of the Society of Jesus, or Jesuits, between the 16th and 17th century played a si ...

) were relatively peaceful and focused on integration rather than cultural imperialism

Cultural imperialism (sometimes referred to as cultural colonialism) comprises the cultural dimensions of imperialism. The word "imperialism" often describes practices in which a social entity engages culture (including language, traditions, ...

.

The expansion of the Catholic Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire ( pt, Império Português), also known as the Portuguese Overseas (''Ultramar Português'') or the Portuguese Colonial Empire (''Império Colonial Português''), was composed of the overseas colonies, factories, and the ...

and Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

with a significant role played by the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

led to the Christianization

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

of the indigenous populations of the Americas such as the Aztec

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl ...

s and Inca

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, ( Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The adm ...

s. Later waves of colonial expansion such as the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonization of most of Africa by seven Western European powers during a short period known as New Imperialism ...

or the struggle for India by the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

led to Christianization of other native populations across the globe, eclipsing that of the Roman period and making it a truly global religion.

Protestant Reformation

The

The Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

yielded scholars the ability to read the scriptures in their original languages, and this in part stimulated the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and i ...

. Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

, a ''Doctor in Bible'' at the University of Wittenberg

Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg (german: Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg), also referred to as MLU, is a public, research-oriented university in the cities of Halle and Wittenberg and the largest and oldest university i ...

,Brecht, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:12-27. began to teach that salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its ...

is a gift of God's grace

Grace may refer to:

Places United States

* Grace, Idaho, a city

* Grace (CTA station), Chicago Transit Authority's Howard Line, Illinois

* Little Goose Creek (Kentucky), location of Grace post office

* Grace, Carroll County, Missouri, an uninc ...

, attainable only through faith

Faith, derived from Latin ''fides'' and Old French ''feid'', is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or In the context of religion, one can define faith as "belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

Religious people ofte ...

in Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and relig ...

, who in humility paid for sin.Wriedt, Markus. "Luther's Theology", in ''The Cambridge Companion to Luther''. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003, pp.88–94. Along with the doctrine of justification, the Reformation promoted a higher view of the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus ...

. As Martin Luther said, "The true rule is this: God's Word shall establish articles of faith, and no one else, not even an angel can do so." These two ideas in turn promoted the concept of the priesthood of all believers. Other important reformers were John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

, Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Univ ...

, Philipp Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lut ...

, Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer ( early German: ''Martin Butzer''; 11 November 1491 – 28 February 1551) was a German Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg who influenced Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican doctrines and practices. Bucer was originally a me ...

and the Anabaptist

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

s.

These reformers are distinguished from previous ones in that they considered the root of corruptions to be doctrinal (rather than simply a matter of moral weakness or lack of ecclesiastical discipline), and thus they aimed to change contemporary doctrines to accord with what they perceived to be the "true gospel." The word ''Protestant'' is derived from the Latin ''protestatio'' meaning ''declaration'' which refers to the letter of protestation by Lutheran princes against the decision of the Diet of Speyer in 1529, which reaffirmed the edict of the Diet of Worms

The Diet of Worms of 1521 (german: Reichstag zu Worms ) was an imperial diet (a formal deliberative assembly) of the Holy Roman Empire called by Emperor Charles V and conducted in the Imperial Free City of Worms. Martin Luther was summoned t ...

against the Reformation.Definition of Protestantism at the Episcopal Church websiteSince that time, the term has been used in many different senses, but most often as a general term refers to

Western Christianity

Western Christianity is one of two sub-divisions of Christianity ( Eastern Christianity being the other). Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the Old Catholi ...

that is not subject to papal authority. The term "Protestant" was not originally used by Reformation era leaders; instead, they called themselves "evangelical", emphasising the "return to the true gospel (Greek: ''euangelion'')."

The beginning of the Protestant Reformation is generally identified with Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

and the posting of the 95 Theses

The ''Ninety-five Theses'' or ''Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences''-The title comes from the 1517 Basel pamphlet printing. The first printings of the ''Theses'' use an incipit rather than a title which summarizes the content ...

on the castle church in Wittenberg

Wittenberg ( , ; Low Saxon: ''Wittenbarg''; meaning ''White Mountain''; officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg (''Luther City Wittenberg'')), is the fourth largest town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Wittenberg is situated on the River Elbe, north of ...

, Germany in 1517. Early protest was against corruptions such as simony

Simony () is the act of selling church offices and roles or sacred things. It is named after Simon Magus, who is described in the Acts of the Apostles as having offered two disciples of Jesus payment in exchange for their empowering him to i ...

, episcopal vacancies, and the sale of indulgence

In the teaching of the Catholic Church, an indulgence (, from , 'permit') is "a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for sins". The ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' describes an indulgence as "a remission before God of ...

s. The three most important traditions to emerge directly from the Protestant Reformation were the Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

, Reformed (Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

, Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

, etc.), and Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

traditions, though the latter group identifies as both "Reformed" and "Catholic", and some subgroups reject the classification as "Protestant."

The Protestant Reformation may be divided into two distinct but basically simultaneous movements, the Magisterial Reformation

The Magisterial Reformation "denotes the Lutheran, Calvinist eformed and Anglican churches" and how these denominations "related to secular authorities, such as princes, magistrates, or city councils", i.e. "the magistracy". While the Radical Ref ...

and the Radical Reformation

The Radical Reformation represented a response to corruption both in the Catholic Church and in the expanding Magisterial Protestant movement led by Martin Luther and many others. Beginning in Germany and Switzerland in the 16th century, the Ra ...

. The Magisterial Reformation involved the alliance of certain theological teachers (Latin: ''magistri'') such as Luther, Zwingli, Calvin, and Cranmer, with secular magistrates who cooperated in the reformation of Christendom. Radical Reformers, besides forming communities outside state sanction, often employed more extreme doctrinal change, such as the rejection of tenets of the Councils of Nicaea and Chalcedon

Chalcedon ( or ; , sometimes transliterated as ''Chalkedon'') was an ancient maritime town of Bithynia, in Asia Minor. It was located almost directly opposite Byzantium, south of Scutari (modern Üsküdar) and it is now a district of the cit ...

. Often the division between magisterial and radical reformers was as or more violent than the general Catholic and Protestant hostilities.

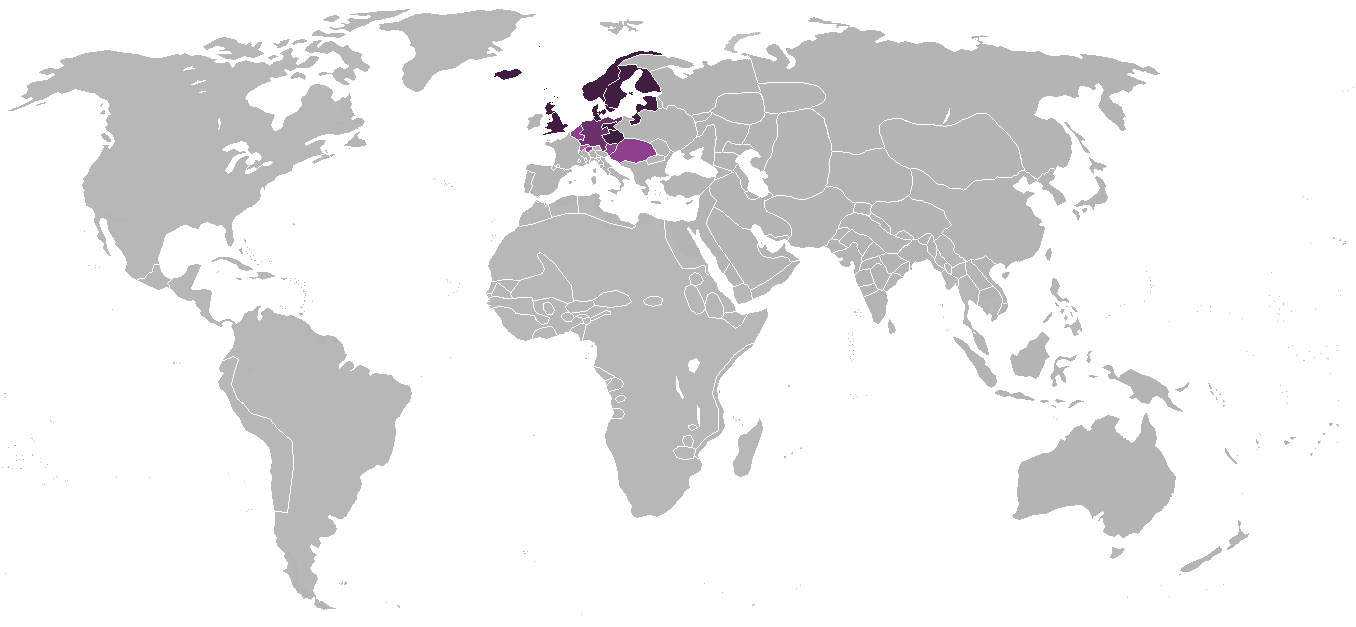

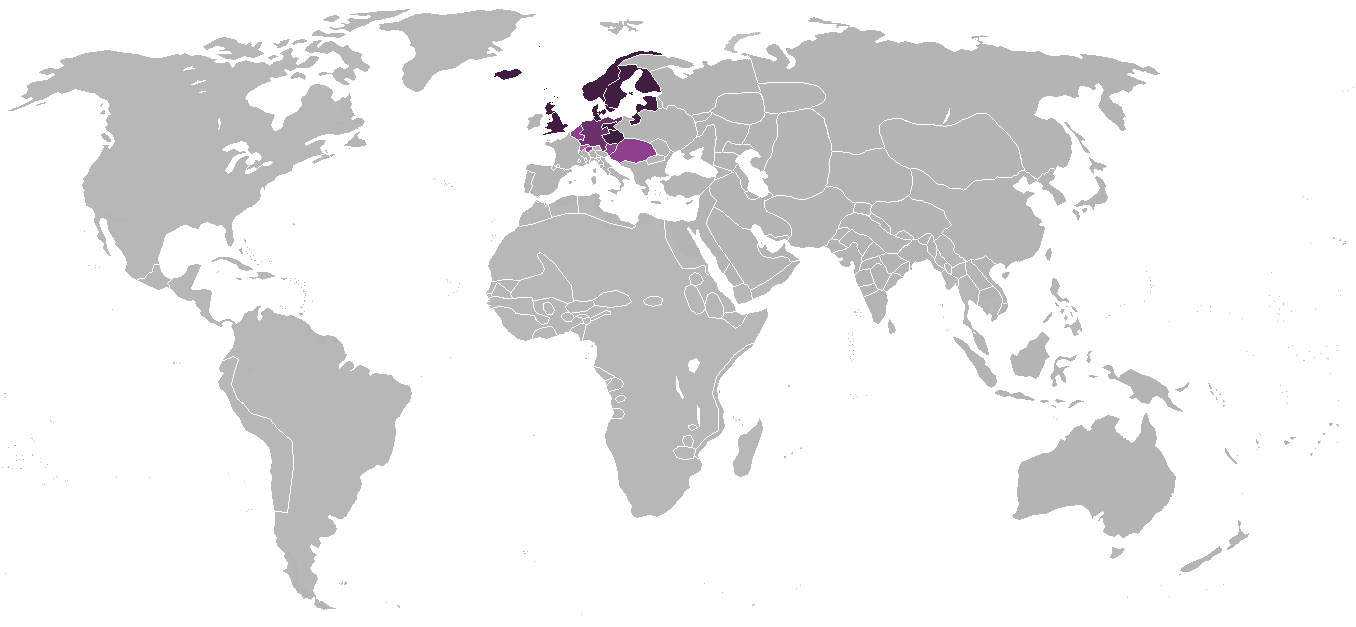

The Protestant Reformation spread almost entirely within the confines of Northern Europe

The northern region of Europe has several definitions. A restrictive definition may describe Northern Europe as being roughly north of the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, which is about 54°N, or may be based on other geographical factors ...

but did not take hold in certain northern areas such as Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

and parts of Germany. The Catholic response to the Protestant Reformation is known as the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

which resulted in a reassertion of traditional doctrines and the emergence of new religious orders aimed at both moral reform and new missionary activity. The Counter-Reformation reconverted approximately 33% of Northern Europe to Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and initiated missions in South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

and Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

, Africa, Asia, and even China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

. Protestant expansion outside of Europe occurred on a smaller scale through colonization of North America

During the Age of Discovery, a large scale European colonization of the Americas took place between about 1492 and 1800. Although the Norse had explored and colonized areas of the North Atlantic, colonizing Greenland and creating a short t ...

and areas of Africa.

Martin Luther and the Lutherans

The protests against Rome began in earnest in 1517 when Martin Luther, an Augustinian monk, called for a reopening of the debate on the sale ofindulgence

In the teaching of the Catholic Church, an indulgence (, from , 'permit') is "a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for sins". The ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' describes an indulgence as "a remission before God of ...

s. Luther's dissent marked a sudden outbreak of a new and irresistible force of discontent which had been pushed underground but not resolved. The quick spread of discontent occurred to a large degree because of the printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

and the resulting swift movement of both ideas and documents, including the ''95 Theses

The ''Ninety-five Theses'' or ''Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences''-The title comes from the 1517 Basel pamphlet printing. The first printings of the ''Theses'' use an incipit rather than a title which summarizes the content ...

''. Information was also widely disseminated in manuscript form, as well as by cheap prints and woodcut

Woodcut is a relief printing technique in printmaking. An artist carves an image into the surface of a block of wood—typically with gouges—leaving the printing parts level with the surface while removing the non-printing parts. Areas tha ...

s among the poorer sections of society.

Parallel to events in Germany was a movement began in Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

under the leadership of Ulrich Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Univ ...

. These two movements quickly agreed on most issues, but some unresolved differences kept them separate. Some followers of Zwingli believed that the Reformation was too conservative and moved independently toward more radical positions, some of which survive among modern day Anabaptists. Other Protestant movements grew up along lines of mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in ...

or humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

, sometimes breaking from Rome or from the Protestants, or forming outside of the churches.

After this first stage of the Reformation, following the excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

of Luther and condemnation of the Reformation by the pope, the work and writings of John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

were influential in establishing a loose consensus among various groups in Switzerland, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, Hungary, Germany and elsewhere.

As Luther began developing his own theology, he increasingly came into conflict with Thomistic scholars, most notably Cardinal Cajetan. Soon, Luther had begun to develop his theology of justification, or process by which one is "made right" (righteous) in the eyes of God. In Catholic theology, one is made righteous by a progressive infusion of grace accepted through faith and cooperated with through good works. Luther's doctrine of justification differed from Catholic theology in that justification rather meant "the declaring of one to be righteous", where God imputes the merits of Christ upon one who remains without inherent merit. In this process, good works are more of an unessential byproduct that contribute nothing to one's own state of righteousness. Conflict between Luther and leading theologians led to his gradual rejection of authority of the Church hierarchy. In 1520, he was condemned for heresy by the papal bull ''Exsurge Domine

() is a papal bull promulgated on 15 June 1520 by Pope Leo X. It was written in response to the teachings of Martin Luther which opposed the views of the Church. It censured forty-one propositions extracted from Luther's ''Ninety-five Theses'' ...

'', which he burned at Wittenberg along with books of canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is t ...

.

Luther's refusal to retract his writings in confrontation with the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain ( Castile and Aragon) fr ...

at the Diet of Worms

The Diet of Worms of 1521 (german: Reichstag zu Worms ) was an imperial diet (a formal deliberative assembly) of the Holy Roman Empire called by Emperor Charles V and conducted in the Imperial Free City of Worms. Martin Luther was summoned t ...

in 1521 resulted in his excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

by Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X ( it, Leone X; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political an ...

and declaration as an outlaw

An outlaw, in its original and legal meaning, is a person declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, all legal protection was withdrawn from the criminal, so that anyone was legally empowered to persecute or kill th ...

. His translation of the Bible into the language of the people made the Scriptures more accessible, causing a tremendous impact on the church and on German culture. It fostered the development of a standard version of the German language

German ( ) is a West Germanic language mainly spoken in Central Europe. It is the most widely spoken and official or co-official language in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and the Italian province of South Tyrol. It is also a ...

, added several principles to the art of translation, and influenced the translation of the King James Bible

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611, by sponsorship of ...

.''Tyndale's New Testament, trans. from the Greek by William Tyndale in 1534 in a modern-spelling edition and with an introduction by David Daniell''. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the w ...

Press, 1989, ix–x. His hymn

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hymn ...

s inspired the development of congregational singing within Christianity.Bainton, p.269 His marriage to Katharina von Bora

Katharina von Bora (; 29 January 1499 – 20 December 1552), after her wedding Katharina Luther, also referred to as "die Lutherin" ("the Lutheress"), was the wife of Martin Luther, German reformer and a seminal figure of the Protestant Refor ...

set a model for the practice of clerical marriage within Protestantism.

Luther's insights are generally held to have been a major foundation of the Protestant movement

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

. The relationship between Lutheranism and the Protestant tradition is, however, ambiguous: some Lutherans consider Lutheranism to be outside the Protestant tradition, while some see it as part of this tradition.

Widening breach

Luther's writings circulated widely, reaching France, England, and Italy as early as 1519, and students thronged to Wittenberg to hear him speak. He published a short commentary on Galatians and his ''Work on the Psalms''. At the same time, he received deputations from Italy and from theUtraquist

Utraquism (from the Latin ''sub utraque specie'', meaning "under both kinds") or Calixtinism (from chalice; Latin: ''calix'', mug, borrowed from Greek ''kalyx'', shell, husk; Czech: kališníci) was a belief amongst Hussites, a reformist Christi ...

s of Bohemia; Ulrich von Hutten

Ulrich von Hutten (21 April 1488 – 29 August 1523) was a German knight, scholar, poet and satirist, who later became a follower of Martin Luther and a Protestant reformer.

By 1519, he was an outspoken critic of the Roman Catholic Church. Hu ...

and Franz von Sickingen

Franz von Sickingen (2 March 14817 May 1523) was an Imperial Knight who, with Ulrich von Hutten, led the so-called "Knights' Revolt," and was one of the most notable figures of the early period of the Protestant Reformation. Sickingen was nickn ...

offered to place Luther under their protection.Macauley Jackson, Samuel and Gilmore, George William. (eds."Martin Luther"

''The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge'', New York, London, Funk and Wagnalls Co., 1908–1914; Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1951, 71. This early portion of Luther's career was one of his most creative and productive. Three of his best known works were published in 1520: ''

To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation

''To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation'' (german: An den christlichen Adel deutscher Nation) is the first of three tracts written by Martin Luther in 1520. In this work, he defined for the first time the signature doctrines of the priesth ...

'', ''On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church

''Prelude on the Babylonian Captivity of the Church'' ( la, De captivitate Babylonica ecclesiae, praeludium Martini Lutheri, October 1520) was the second of the three major treatises published by Martin Luther in 1520, coming after the '' Addres ...

'', and ''On the Freedom of a Christian

''On the Freedom of a Christian'' (Latin: ''"De Libertate Christiana"''; German: ''"Von der Freiheit eines Christenmenschen"''), sometimes also called ''"A Treatise on Christian Liberty"'' (November 1520), was the third of Martin Luther’s major ...

''.

Finally on 30 May 1519, when the pope demanded an explanation, Luther wrote a summary and explanation of his theses to the pope. While the pope may have conceded some of the points, he did not like the challenge to his authority so he summoned Luther to Rome to answer these. At that point Frederick the Wise

Frederick III (17 January 1463 – 5 May 1525), also known as Frederick the Wise (German ''Friedrich der Weise''), was Elector of Saxony from 1486 to 1525, who is mostly remembered for the worldly protection of his subject Martin Luther.

Fre ...

, the Saxon Elector, intervened. He did not want one of his subjects to be sent to Rome to be judged by the Catholic clergy

The sacrament of holy orders in the Catholic Church includes three orders: bishops, priests, and deacons, in decreasing order of rank, collectively comprising the clergy. In the phrase "holy orders", the word "holy" means "set apart for a sacre ...

so he prevailed on Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain ( Castile and Aragon) fr ...

to arrange a compromise.

An arrangement was effected, however, whereby that summons was cancelled, and Luther went to Augsburg in October 1518 to meet the papal legate, Cardinal Thomas Cajetan

Thomas Cajetan (; 20 February 14699 August 1534), also known as Gaetanus, commonly Tommaso de Vio or Thomas de Vio, was an Italian philosopher, theologian, cardinal (from 1517 until his death) and the Master of the Order of Preachers 1508 to 151 ...

. The argument was long, but nothing was resolved.

Political maneuvering

What had started as a strictly theological and academic debate had now turned into something of a social and political conflict as well, pitting Luther, his German allies and Northern European supporters againstCharles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infa ...

, France, the Italian pope, their territories and other allies. The conflict would erupt into a religious war after Luther's death, fueled by the political climate of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

and strong personalities on both sides.

In 1526, at the First Diet of Speyer

The Diet of Speyer or the Diet of Spires (sometimes referred to as Speyer I) was an Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire in 1526 in the Imperial City of Speyer in present-day Germany. The Diet's ambiguous edict resulted in a temporary susp ...

, it was decided that until a General Council could meet and settle the theological issues raised by Martin Luther, the Edict of Worms

The Diet of Worms of 1521 (german: Reichstag zu Worms ) was an imperial diet (a formal deliberative assembly) of the Holy Roman Empire called by Emperor Charles V and conducted in the Imperial Free City of Worms. Martin Luther was summoned to t ...

would not be enforced, and each prince could decide if Lutheran teachings and worship would be allowed in his territories. In 1529, at the Second Diet of Speyer

The Diet of Speyer or the Diet of Spires (sometimes referred to as Speyer II) was a Diet of the Holy Roman Empire held in 1529 in the Imperial City of Speyer (located in present-day Germany). The Diet condemned the results of the Diet of Spey ...

, the decision the previous Diet of Speyer was reversed — despite the strong protests of the Lutheran princes, free cities and some Zwinglian

The theology of Ulrich Zwingli was based on an interpretation of the Bible, taking scripture as the inspired word of God and placing its authority higher than what he saw as human sources such as the ecumenical councils and the church fathers. He ...

territories. These states quickly became known as Protestants. At first, this term ''Protestant'' was used politically for the states that resisted the Edict of Worms. Over time, however, this term came to be used for the religious movements that opposed the Roman Catholic tradition in the 16th century.

Lutheranism would become known as a separate movement after the 1530 Diet of Augsburg

The Diet of Augsburg were the meetings of the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire held in the German city of Augsburg. Both an Imperial City and the residence of the Augsburg prince-bishops, the town had hosted the Estates in many such sessi ...

, which was convened by Charles V to try to stop the growing Protestant movement. At the Diet, Philipp Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lut ...

presented a written summary of Lutheran beliefs called the Augsburg Confession

The Augsburg Confession, also known as the Augustan Confession or the Augustana from its Latin name, ''Confessio Augustana'', is the primary confession of faith of the Lutheran Church and one of the most important documents of the Protestant Re ...

. Several of the German princes (and later, kings and princes of other countries) signed the document to define "Lutheran" territories. These princes allied to create the Schmalkaldic League

The Schmalkaldic League (; ; or ) was a military alliance of Lutheran princes within the Holy Roman Empire during the mid-16th century.

Although created for religious motives soon after the start of the Reformation, its members later came to ...

in 1531, which led to the Schmalkald War

The Schmalkaldic War (german: link=no, Schmalkaldischer Krieg) was the short period of violence from 1546 until 1547 between the forces of Emperor Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire (simultaneously King Charles I of Spain), commanded by the D ...

in 1547 that pitted the Lutheran princes of the Schmalkaldic League against the Catholic forces of Charles V.

After the conclusion of the Schmalkald War, Charles V attempted to impose Catholic religious doctrine on the territories that he had defeated. However, the Lutheran movement was far from defeated. In 1577, the next generation of Lutheran theologians gathered the work of the previous generation to define the doctrine of the persisting Lutheran church. This document is known as the Formula of Concord

Formula of Concord (1577) (German, ''Konkordienformel''; Latin, ''Formula concordiae''; also the "''Bergic Book''" or the "''Bergen Book''") is an authoritative Lutheran statement of faith (called a confession, creed, or "symbol") that, in its tw ...

. In 1580, it was published with the Augsburg Confession, the Apology of the Augsburg Confession

The ''Apology of the Augsburg Confession'' was written by Philipp Melanchthon during and after the 1530 Diet of Augsburg as a response to the '' Pontifical Confutation of the Augsburg Confession'', Charles V's commissioned official Roman Catholic ...

, the Large

Large means of great size.

Large may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Arbitrarily large, a phrase in mathematics

* Large cardinal, a property of certain transfinite numbers

* Large category, a category with a proper class of objects and morphisms ...

and Small Catechisms of Martin Luther, the Smalcald Articles

The Smalcald Articles or Schmalkald Articles (german: Schmalkaldische Artikel) are a summary of Lutheran doctrine, written by Martin Luther in 1537 for a meeting of the Schmalkaldic League in preparation for an intended ecumenical Council of the ...

and the Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope

The ''Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope'' (1537) (), ''The Tractate'' for short, is the seventh Lutheran credal document of the Book of Concord. Philip Melanchthon, its author, completed it on February 17, 1537 during the assembly o ...

. Together they were distributed in a volume entitled '' The Book of Concord''.

Results of the Lutheran Reformation

Large numbers of Europeans were excommunicated under the 1521Edict of Worms

The Diet of Worms of 1521 (german: Reichstag zu Worms ) was an imperial diet (a formal deliberative assembly) of the Holy Roman Empire called by Emperor Charles V and conducted in the Imperial Free City of Worms. Martin Luther was summoned to t ...

and subsequent attempts to reiterate it, including the majority of German speakers (the only German speaking areas where the population remained mostly in the Catholic Church were those under the domain or influence of Catholic Austria and Bavaria or the electoral archbishops of Mainz, Cologne, and Trier).

Calvinism

Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

is a system of Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology of Christian belief and practice. Such study concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Christian tradition. Christian theologians use biblical exeg ...

and an approach to Christian life and thought within the Protestant tradition articulated by John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

and subsequently by successors, associates, followers and admirers of Calvin and his interpretation of Scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual pra ...

, and perspective on Christian life and theology. Calvin's system of theology and Christian life forms the basis of the Reformed tradition, a term roughly equivalent to ''Calvinism''.

The Reformed tradition was originally advanced by stalwarts such as Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer ( early German: ''Martin Butzer''; 11 November 1491 – 28 February 1551) was a German Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg who influenced Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican doctrines and practices. Bucer was originally a me ...

, Heinrich Bullinger

Heinrich Bullinger (18 July 1504 – 17 September 1575) was a Swiss Reformer and theologian, the successor of Huldrych Zwingli as head of the Church of Zürich and a pastor at the Grossmünster. One of the most important leaders of the Swiss R ...

and Peter Martyr Vermigli

Peter Martyr Vermigli (8 September 149912 November 1562) was an Italian-born Reformed theologian. His early work as a reformer in Catholic Italy and his decision to flee for Protestant northern Europe influenced many other Italians to convert a ...

, and also influenced English reformers such as Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build the case for the annulment of Hen ...

and John Jewel

John Jewel (''alias'' Jewell) (24 May 1522 – 23 September 1571) of Devon, England was Bishop of Salisbury from 1559 to 1571.

Life

He was the youngest son of John Jewel of Bowden in the parish of Berry Narbor in Devon, by his wife Alice Bel ...

. However, because of Calvin's great influence and role in the confessional and ecclesiastical debates throughout the 17th century, this Reformed movement generally became known as Calvinism. Today, this term also refers to the doctrines and practices of the Reformed churches

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Calv ...

, of which Calvin was an early leader, and the system is perhaps best known for its doctrines of ''predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby ...

'' and ''election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operat ...

''.

The Reformation foundations engaged with Augustinianism

Augustinianism is the philosophical and theological system of Augustine of Hippo and its subsequent development by other thinkers, notably Boethius, Anselm of Canterbury and Bonaventure. Among Augustine's most important works are '' The City of ...

. Both Luther and Calvin thought along lines linked with the theological teachings of Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

. The Augustinianism of the Reformers struggled against Pelagianism

Pelagianism is a Christian theological position that holds that the original sin did not taint human nature and that humans by divine grace have free will to achieve human perfection. Pelagius ( – AD), an ascetic and philosopher from t ...

, a heresy that they perceived in the Catholic Church of their day. In the course of this religious upheaval, the German Peasants' War

The German Peasants' War, Great Peasants' War or Great Peasants' Revolt (german: Deutscher Bauernkrieg) was a widespread popular revolt in some German-speaking areas in Central Europe from 1524 to 1525. It failed because of intense oppositi ...

of 1524–1525 swept through the Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

n, Thuringia

Thuringia (; german: Thüringen ), officially the Free State of Thuringia ( ), is a state of central Germany, covering , the sixth smallest of the sixteen German states. It has a population of about 2.1 million.

Erfurt is the capital and lar ...

n and Swabia

Swabia ; german: Schwaben , colloquially ''Schwabenland'' or ''Ländle''; archaic English also Suabia or Svebia is a cultural, historic and linguistic region in southwestern Germany.

The name is ultimately derived from the medieval Duchy of ...

n principalities, leaving scores of Catholics slaughtered at the hands of Protestant bands, including the Black Company

The Black Company or the Black Troops () was a unit of Franconian farmers and knights that fought on the side of the peasants during the Peasants' Revolt in the 1520s, during the Protestant Reformation in Germany.

Name

The original German nam ...

of Florian Geier, a knight from Giebelstadt who joined the peasants in the general outrage against the Catholic hierarchy.

Ulrich Zwingli

Ulrich Zwingli was a Swiss scholar and parish priest who was likewise influential in the beginnings of the Protestant Reformation. Zwingli claimed that his theology owed nothing to Luther and that he had developed it in 1516, before Luther's famous protest, though his doctrine of justification was remarkably similar to that of Luther. In 1518, Zwingli was given a post at the wealthy collegiate church of theGrossmünster

The Grossmünster (; "great minster") is a Romanesque-style Protestant church in Zürich, Switzerland. It is one of the four major churches in the city (the others being the Fraumünster, Predigerkirche and St. Peterskirche). Its congregation f ...

in Zürich

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Z ...

, where he remained until his death. Soon he had risen to prominence in the city. Zwingli began preaching his version of reform, with certain points as the aforementioned doctrine of justification, but others (with which Luther vehemently disagreed) such as the position that veneration of icons was actually idolatry and thus a violation of the first commandment, and the denial of the real presence

The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist is the Christian doctrine that Jesus Christ is present in the Eucharist, not merely symbolically or metaphorically, but in a true, real and substantial way.

There are a number of Christian denomin ...

in the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was institu ...

. Soon the city council had accepted Zwingli's doctrines, and Zürich became a focal point of more radical reforming movements. Followers of Zwingli pushed his message and reforms far further than even he had intended, such as rejecting infant baptism. This split between Luther and Zwingli formed the essence of the Protestant division between Lutheran and Reformed theology. Meanwhile, political tensions increased; Zwingli and the Zürich leadership imposed an economic blockade on the inner Catholic states of Switzerland, which led to a battle in which Zwingli, in full armor, was slain along with his troops.

John Calvin

John Calvin was a French cleric and doctor of law. He belonged to the second generation of the Reformation, publishing his theological tome, the ''Institutes of the Christian Religion

''Institutes of the Christian Religion'' ( la, Institutio Christianae Religionis) is John Calvin's seminal work of systematic theology. Regarded as one of the most influential works of Protestant theology, it was published in Latin in 1536 (at th ...

'', in 1536 (later revised) and establishing himself as a leader of the Reformed church in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situa ...

, which became an "unofficial capital" of Reformed Christianity in the second half of the 16th century. He exerted a remarkable amount of authority in the city and over the city council, such that he has (rather ignominiously) been called a "Protestant pope." Calvin established an eldership together with a consistory

Consistory is the anglicized form of the consistorium, a council of the closest advisors of the Roman emperors. It can also refer to:

*A papal consistory, a formal meeting of the Sacred College of Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church

* Consistor ...

, where pastors and the elders established matters of religious discipline for the Genevan population. Calvin's theology is best known for his doctrine of (double) predestination, which held that God had, from all eternity, providentially foreordained who would be saved (the elect

Election in Christianity involves God choosing a particular person or group of people to a particular task or relationship, especially eternal life.

Election to eternal life is viewed by some as conditional on a person's faith, and by others as ...

) and likewise who would be damned ( the reprobate). Predestination was not the dominant idea in Calvin's works, but it would seemingly become so for many of his Reformed successors.

Following the excommunication of Luther and condemnation of the Reformation by the pope, the work and writings of Calvin were influential in establishing a loose consensus among various groups in Switzerland, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, Hungary, Germany and elsewhere.

Geneva became the unofficial capital of the Protestant movement, led by the Frenchman, Jean Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

, until his death when Calvin's ally, Zwingli, assumed the spiritual leadership of the group.

Arminianism

Arminianism

Arminianism is a branch of Protestantism based on the theological ideas of the Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Arminius (1560–1609) and his historic supporters known as Remonstrants. Dutch Arminianism was originally articulated in the ''Rem ...

is a school of soteriological

Soteriology (; el, σωτηρία ' " salvation" from σωτήρ ' "savior, preserver" and λόγος ' "study" or "word") is the study of religious doctrines of salvation. Salvation theory occupies a place of special significance in many reli ...

thought in Protestant Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology of Christian belief and practice. Such study concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Christian tradition. Christian theologians use biblical exeg ...

founded by the Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

theologian Jacobus Arminius

Jacobus Arminius (10 October 1560 – 19 October 1609), the Latinized name of Jakob Hermanszoon, was a Dutch theologian during the Protestant Reformation period whose views became the basis of Arminianism and the Dutch Remonstrant movement. H ...

. Its acceptance stretches through much of mainstream Protestantism. Because of the influence of John Wesley

John Wesley (; 2 March 1791) was an English cleric, theologian, and evangelist who was a leader of a revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The societies he founded became the dominant form of the independent Meth ...

, Arminianism is perhaps most prominent in the Methodist movement

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's br ...

.

Arminianism holds to the following tenets:

* Humans are naturally unable to make any effort towards salvation

* Salvation is possible by grace alone

''Sola gratia'', meaning by grace alone, is one of the five ''solae'' and consists in the belief that salvation comes by divine grace or "unmerited favor" only, not as something earned or deserved by the sinner. It is a Christian theologica ...

* Works of human effort cannot cause or contribute to salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its ...

* God's election is conditional on faith in Jesus

* Jesus' atonement

Atonement (also atoning, to atone) is the concept of a person taking action to correct previous wrongdoing on their part, either through direct action to undo the consequences of that act, equivalent action to do good for others, or some other ...

was potentially for all people

* God allows his grace

Grace may refer to:

Places United States

* Grace, Idaho, a city

* Grace (CTA station), Chicago Transit Authority's Howard Line, Illinois

* Little Goose Creek (Kentucky), location of Grace post office

* Grace, Carroll County, Missouri, an uninc ...

to be resisted by those unwilling to believe

* Salvation can be lost, as continued salvation is conditional upon continued faith

Arminianism is most accurately used to define those who affirm the original beliefs of Jacobus Arminius, but the term can also be understood as an umbrella for a larger grouping of ideas including those of Simon Episcopius

Simon Episcopius (8 January 1583 – 4 April 1643) was a Dutch theologian and Remonstrant who played a significant role at the Synod of Dort in 1618. His name is the Latinized form of his Dutch name Simon Bisschop.

Life

Born in Amsterdam, in 1 ...

, Hugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius (; 10 April 1583 – 28 August 1645), also known as Huig de Groot () and Hugo de Groot (), was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, poet and playwright.

A teenage intellectual prodigy, he was born in Delft ...

, John Wesley

John Wesley (; 2 March 1791) was an English cleric, theologian, and evangelist who was a leader of a revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The societies he founded became the dominant form of the independent Meth ...

, and others. There are two primary perspectives on how the system is applied in detail: Classical Arminianism, which sees Arminius as its figurehead, and Wesleyan Arminianism, which (as the name suggests) sees John Wesley as its figurehead. Wesleyan Arminianism is sometimes synonymous with Methodism.

Within the broad scope of church history

__NOTOC__

Church history or ecclesiastical history as an academic discipline studies the history of Christianity and the way the Christian Church has developed since its inception.

Henry Melvill Gwatkin defined church history as "the spiritua ...

, Arminianism is closely related to Calvinism, and the two systems share both history and many doctrines. Nonetheless, they are often viewed as archrivals within Evangelicalism because of their disagreement over the doctrines of predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby ...

and salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its ...

.

Anglicanism and the English Reformation

Anglican doctrine emerged from the interweaving of two main strands of Christian doctrine during theEnglish Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and poli ...

in the 16th and 17th centuries. The first strand is the Catholic doctrine taught by the established church in England in the early 16th century. The second strand is a range of Protestant Reformed teachings brought to England from neighbouring countries in the same period, notably Calvinism and Lutheranism.

The Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

was the national branch of the Catholic Church. The formal doctrines had been documented in canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is t ...

over the centuries, and the Church of England still follows an unbroken tradition of canon law. The English Reformation did not dispense with all previous doctrines. The church not only retained the core Catholic beliefs common to Reformed doctrine in general, such as the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

, the Virgin Birth of Jesus, the nature of Jesus as fully human and fully God, the Resurrection of Jesus

The resurrection of Jesus ( grc-x-biblical, ἀνάστασις τοῦ Ἰησοῦ) is the Christian belief that God raised Jesus on the third day after his crucifixion, starting – or restoring – his exalted life as Christ and Lo ...

, Original Sin

Original sin is the Christian doctrine that holds that humans, through the fact of birth, inherit a tainted nature in need of regeneration and a proclivity to sinful conduct. The biblical basis for the belief is generally found in Genesis 3 ...

, and Excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

(as affirmed by the Thirty-Nine Articles

The Thirty-nine Articles of Religion (commonly abbreviated as the Thirty-nine Articles or the XXXIX Articles) are the historically defining statements of doctrines and practices of the Church of England with respect to the controversies of the ...

), but also retained some Catholic teachings which were rejected by true Protestants, such as the three orders of ministry and the apostolic succession

Apostolic succession is the method whereby the ministry of the Christian Church is held to be derived from the apostles by a continuous succession, which has usually been associated with a claim that the succession is through a series of bisho ...

of bishops.

Unlike other reform movements, the English Reformation began by royal influence. Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

considered himself a thoroughly Catholic king, and in 1521 he defended the papacy against Luther in a book he commissioned entitled, '' The Defence of the Seven Sacraments'', for which Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X ( it, Leone X; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political an ...

awarded him the title ''Fidei Defensor

Defender of the Faith ( la, Fidei Defensor or, specifically feminine, '; french: Défenseur de la Foi) is a phrase that has been used as part of the full style of many English, Scottish, and later British monarchs since the early 16th century. It ...

'' (Defender of the Faith). However, the king came into conflict with the papacy when he wished to annul his marriage with Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine, ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was Queen of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 11 June 1509 until their annulment on 23 May 1533. She was previously ...

, for which he needed papal sanction. Catherine, among many other noble relations, was the aunt of Emperor Charles V

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain ( Castile and Aragon) fr ...

, the papacy's most significant secular supporter. The ensuing dispute eventually led to a break from Rome. In 1534, the Act of Supremacy

The Acts of Supremacy are two acts passed by the Parliament of England in the 16th century that established the English monarchs as the head of the Church of England; two similar laws were passed by the Parliament of Ireland establishing the En ...

made Henry the Supreme Head of the Church of England. Between 1535 and 1540, under Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell (; 1485 – 28 July 1540), briefly Earl of Essex, was an English lawyer and statesman who served as chief minister to King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1540, when he was beheaded on orders of the king, who later blamed false char ...

, the policy known as the Dissolution of the Monasteries was put into effect.

There were some notable opponents to the Henrician Reformation, such as Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord ...

and Bishop John Fisher

John Fisher (c. 19 October 1469 – 22 June 1535) was an English Catholic bishop, cardinal, and theologian. Fisher was also an academic and Chancellor of the University of Cambridge. He was canonized by Pope Pius XI.

Fisher was executed by o ...

, who were executed for their opposition. There was also a growing party of reformers who were imbued with the Zwinglian and Calvinistic doctrines. When Henry died he was succeeded by his Protestant son Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

, who, through his empowered councillors (with the king being only nine years old at his succession and not yet sixteen at his death) the Duke of Somerset and the Duke of Northumberland, ordered the destruction of images in churches, and the closing of the chantries

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, which historically was an obiit, or

# a chantry chapel, a building on private land, or an area i ...

. Under Edward VI the reform of the Church of England was established unequivocally in doctrinal terms. Yet, at a popular level, religion in England was still in a state of flux. Following a brief Roman Catholic restoration during the reign of Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

1553–1558, a loose consensus developed during the reign of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

, though this point is one of considerable debate among historians. Yet it is the so-called "Elizabethan Religious Settlement

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Implemented between 1559 and 1563, the settlement is considered the end of the ...

" to which the origins of Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

are traditionally ascribed.

The political separation of the Church of England from Rome, beginning in 1529 and completed in 1536, brought England alongside this broad Reformed movement. However, religious changes in the English national church proceeded more conservatively than elsewhere in Europe. Reformers in the Church of England alternated for centuries between sympathies for Catholic traditions and Protestantism, progressively forging a stable compromise between adherence to ancient tradition and Protestantism, which is now sometimes called the via media

''Via media'' is a Latin phrase meaning "the middle road" and is a philosophical maxim for life which advocates moderation in all thoughts and actions.

Originating from the Delphic Maxim ''nothing to excess'' and subsequent Ancient Greek philosop ...

.

Monasticism

During the Reformation the teachings of Martin Luther led to the end of the monasteries, but a few Protestants followedmonastic

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religion, religious way of life in which one renounces world (theology), worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic ...

lives. Loccum Abbey

Loccum Abbey (Kloster Loccum) is a Lutheran monastery in the town of Rehburg-Loccum, Lower Saxony, near Steinhude Lake.

History

Originating as a foundation of Count Wilbrand of Hallermund, Loccum Abbey was settled from Volkenroda Abbey under th ...

and Amelungsborn Abbey

Amelungsborn Abbey, also Amelunxborn Abbey (''Kloster Amelungsborn''), is a Lutheran monastery in Germany. It is located near Negenborn and Stadtoldendorf, in the ''Landkreis'' of Holzminden in the Weserbergland. It was the second oldest Cist ...

have the longest traditions as Lutheran monasteries.

Since the 19th century there have been a renewal in the monastic life among Protestants.

Monastic life in England came to an abrupt end with Dissolution of the Monasteries during the reign of King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

. The property and lands of the monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

were confiscated and either retained by the king or given to loyal protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The character ...

. Monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedic ...

s and nun

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service, typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.''The Oxford English Dictionary'', vol. X, page 599. The term is o ...

s were forced to either flee for the continent or to abandon their vocations. For around 300 years, there were no monastic communities within any of the Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

churches.

Scandinavia

All ofScandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and S ...

ultimately adopted Lutheranism over the course of the 16th century, as the monarchs of Denmark (who also ruled Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of ...

and Iceland