Christianity in late antiquity on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Christianity in late antiquity traces

Christianity in late antiquity traces

''De Mortibus Persecutorum''

("On the Deaths of the Persecutors") ch. 35–34 With the passage in 313 AD of the In 313, he and

In 313, he and

During this era, several Ecumenical Councils were convened.

* First Council of Nicaea (325)

* First Council of Constantinople (381)

* First Council of Ephesus (431)

* Council of Chalcedon (451)

These were mostly concerned with Christological disputes and represent an attempt to reach an orthodoxy, orthodox consensus and to establish a unified Christian theology. The Council of Nicaea (325) condemned Arian teachings as heresy and produced a creed (see Nicene Creed). The Council of Ephesus condemned Nestorianism and affirmed the Blessed Virgin Mary to be Theotokos ("God-bearer" or "Mother of God"). The Council of Chalcedon asserted that Christ had two natures, fully God and fully man, distinct yet always in perfect union, largely affirming Leo's "Tome." It overturned the result of the Second Council of Ephesus, condemned Monophysitism and influenced later condemnations of Monothelitism. None of the councils were universally accepted, and each major doctrinal decision resulted in a schism. The First Council of Ephesus caused the Nestorian Schism in 431 and separated the Church of the East, and the Council of Chalcedon caused the Chalcedonian Schism in 451, which separated Oriental Orthodoxy.

During this era, several Ecumenical Councils were convened.

* First Council of Nicaea (325)

* First Council of Constantinople (381)

* First Council of Ephesus (431)

* Council of Chalcedon (451)

These were mostly concerned with Christological disputes and represent an attempt to reach an orthodoxy, orthodox consensus and to establish a unified Christian theology. The Council of Nicaea (325) condemned Arian teachings as heresy and produced a creed (see Nicene Creed). The Council of Ephesus condemned Nestorianism and affirmed the Blessed Virgin Mary to be Theotokos ("God-bearer" or "Mother of God"). The Council of Chalcedon asserted that Christ had two natures, fully God and fully man, distinct yet always in perfect union, largely affirming Leo's "Tome." It overturned the result of the Second Council of Ephesus, condemned Monophysitism and influenced later condemnations of Monothelitism. None of the councils were universally accepted, and each major doctrinal decision resulted in a schism. The First Council of Ephesus caused the Nestorian Schism in 431 and separated the Church of the East, and the Council of Chalcedon caused the Chalcedonian Schism in 451, which separated Oriental Orthodoxy.

The council approved the current form of the Nicene Creed as used in the Eastern Orthodox Church and Oriental Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodox churches, but, except when Greek language, Greek is used, with two additional Latin phrases ("Deum de Deo" and "Filioque") in the West. The form used by the Armenian Apostolic Church, which is part of Oriental Orthodoxy, has many more additions. This fuller creed may have existed before the Council and probably originated from the baptismal creed of Constantinople.

The council also condemned Apollinarism,"Constantinople, First Council of." Cross, F. L., ed. ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church''. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005 the teaching that there was no human mind or soul in Christ. It also granted Constantinople honorary precedence over all churches save Rome.

The council did not include Western bishops or Roman legates, but it was accepted as ecumenical in the West.

The council approved the current form of the Nicene Creed as used in the Eastern Orthodox Church and Oriental Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodox churches, but, except when Greek language, Greek is used, with two additional Latin phrases ("Deum de Deo" and "Filioque") in the West. The form used by the Armenian Apostolic Church, which is part of Oriental Orthodoxy, has many more additions. This fuller creed may have existed before the Council and probably originated from the baptismal creed of Constantinople.

The council also condemned Apollinarism,"Constantinople, First Council of." Cross, F. L., ed. ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church''. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005 the teaching that there was no human mind or soul in Christ. It also granted Constantinople honorary precedence over all churches save Rome.

The council did not include Western bishops or Roman legates, but it was accepted as ecumenical in the West.

The council repudiated the Eutyches, Eutychian doctrine of monophysitism, described and delineated the "Hypostatic Union" and Hypostatic Union, two natures of Christ, human and divine; adopted the Chalcedonian Creed. For those who accept it, it is the Fourth Ecumenical Council. It rejected the decision of the Second Council of Ephesus, referred to by the pope at the time as the "Robber Council".

The Council of Chalcedon resulted in a schism, with the Oriental Orthodox Churches breaking communion with Chalcedonian Christianity.

The council repudiated the Eutyches, Eutychian doctrine of monophysitism, described and delineated the "Hypostatic Union" and Hypostatic Union, two natures of Christ, human and divine; adopted the Chalcedonian Creed. For those who accept it, it is the Fourth Ecumenical Council. It rejected the decision of the Second Council of Ephesus, referred to by the pope at the time as the "Robber Council".

The Council of Chalcedon resulted in a schism, with the Oriental Orthodox Churches breaking communion with Chalcedonian Christianity.

The Germanic people underwent gradual Christianization from Late Antiquity. In the 4th century, the early process of Christianization of the various Germanic peoples, Germanic people was partly facilitated by the prestige of the Christian

The Germanic people underwent gradual Christianization from Late Antiquity. In the 4th century, the early process of Christianization of the various Germanic peoples, Germanic people was partly facilitated by the prestige of the Christian

History of Christianity Reading Room:

Extensive online resources for the study of global church history (Tyndale Seminary).

Sketches of Church History

From AD 33 to the Reformation by Rev. J. C Robertson, M.A, Canon of Canterbury *

Theandros

a journal of Orthodox theology and philosophy, containing articles on early Christianity and patristic studies.

Fourth-Century Christianity

{{History of Europe Christianity in late antiquity,

Christianity in late antiquity traces

Christianity in late antiquity traces Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

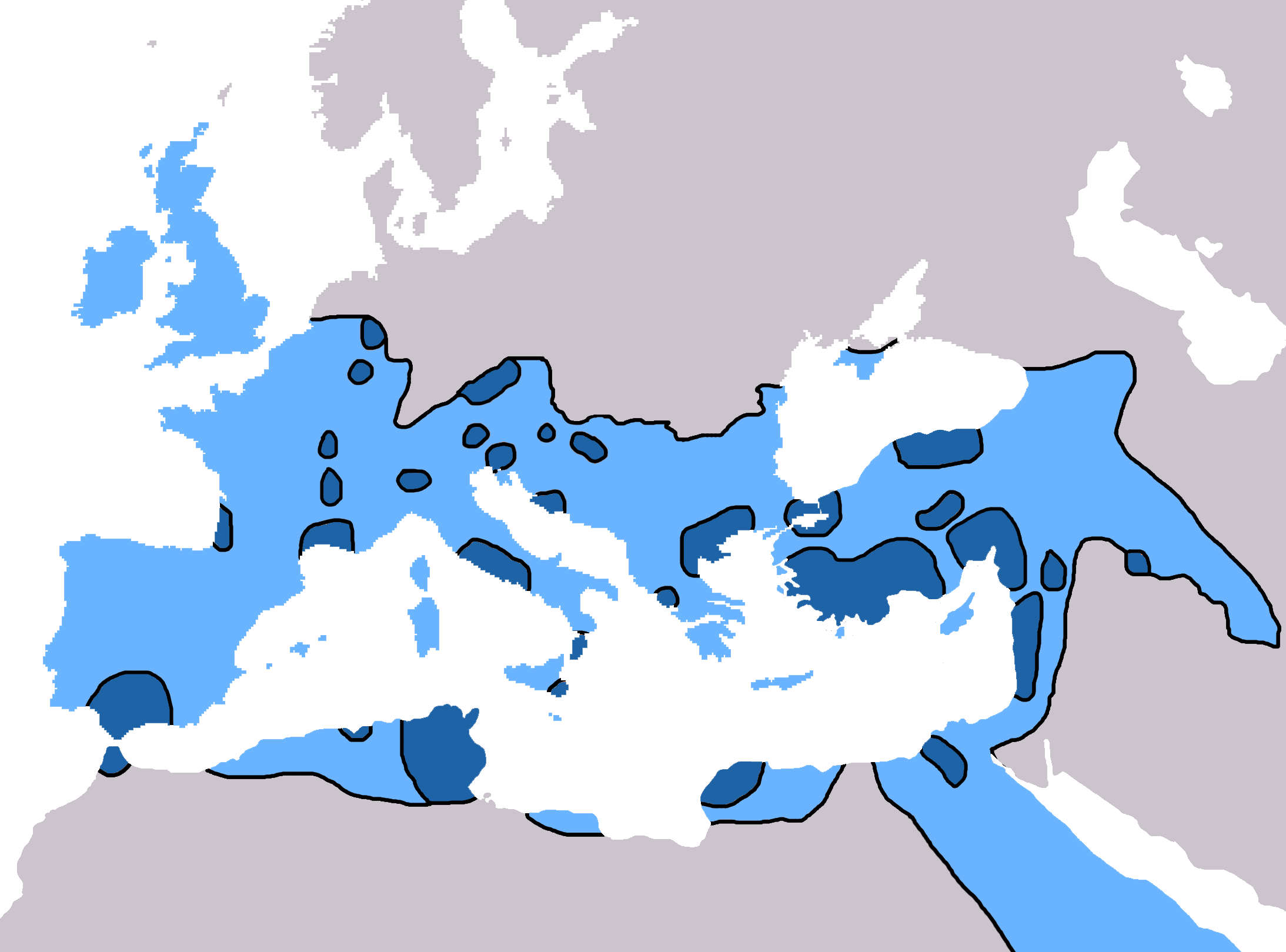

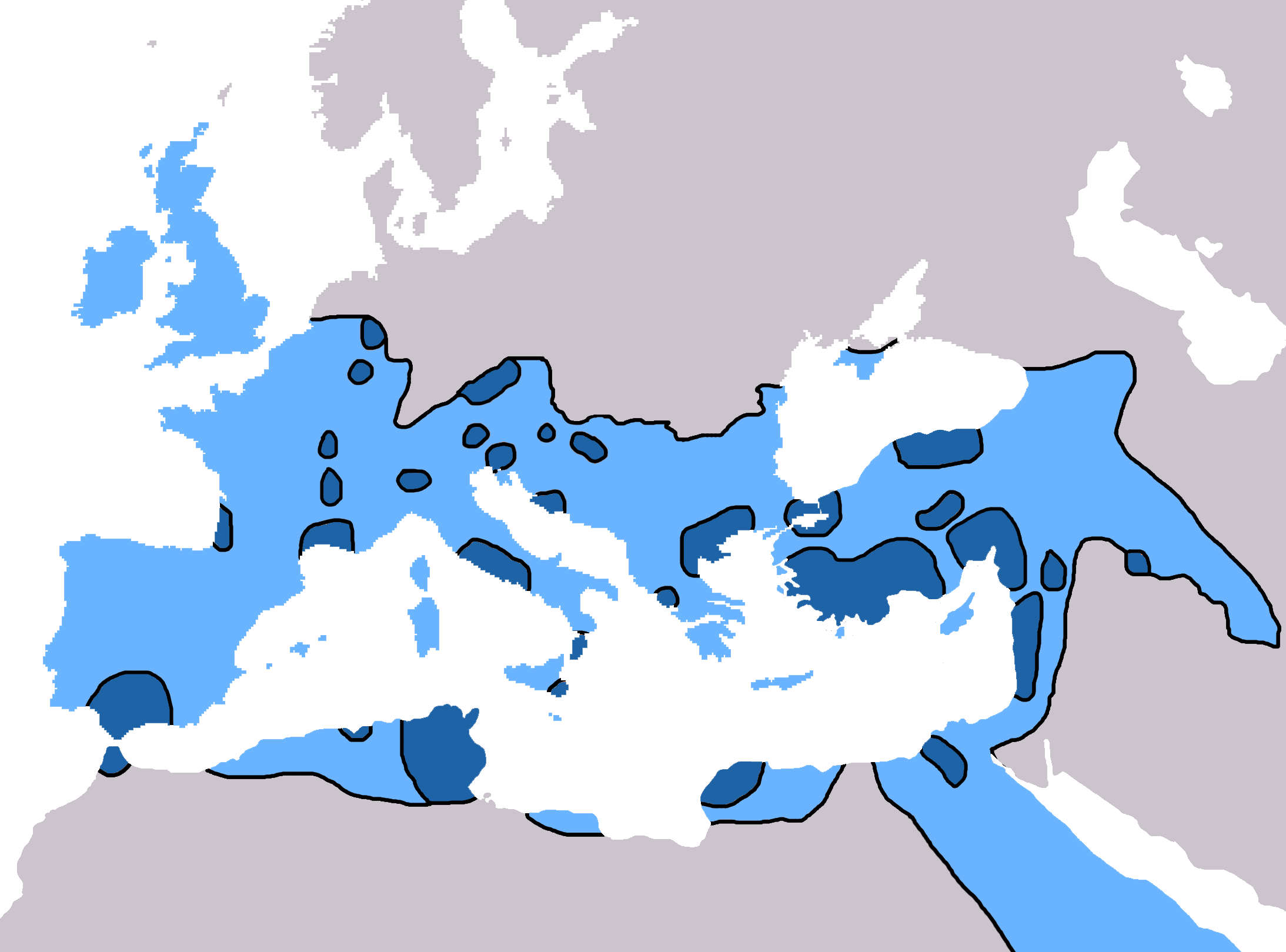

during the Christian Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

– the period from the rise of Christianity under Emperor Constantine (c. 313), until the fall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vas ...

(c. 476). The end-date of this period varies because the transition to the sub-Roman period occurred gradually and at different times in different areas. One may generally date late ancient Christianity as lasting to the late 6th century and the re-conquests under Justinian

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

(reigned 527–565) of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

, though a more traditional end-date is 476, the year in which Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustus

Romulus Augustus ( 465 – after 511), nicknamed Augustulus, was Roman emperor of the West from 31 October 475 until 4 September 476. Romulus was placed on the imperial throne by his father, the ''magister militum'' Orestes, and, at that time, ...

, traditionally considered the last western emperor.

Christianity began to spread initially from Roman Judaea without state support or endorsement. It became the state religion of Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ' ...

in either 301 or 314, of Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

in 325, and of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

in 337. With the Edict of Thessalonica

The Edict of Thessalonica (also known as ''Cunctos populos''), issued on 27 February AD 380 by Theodosius I, made the Catholicism of Nicene Christians the state church of the Roman Empire.

It condemned other Christian creeds such as Arianism ...

it became the state religion of the Roman Empire in 380.

Persecution and legalisation

TheEdict of Serdica

The Edict of Serdica, also called Edict of Toleration by Galerius, was issued in 311 in Serdica (now Sofia, Bulgaria) by Roman Emperor Galerius. It officially ended the Diocletianic Persecution of Christianity in the Eastern Roman Empire.

The E ...

was issued in 311 by the Roman emperor Galerius

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus (; 258 – May 311) was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across th ...

, officially ending the Diocletianic persecution

The Diocletianic or Great Persecution was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. In 303, the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius issued a series of edicts rescinding Christians' legal rig ...

of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

in the East.Lactantius''De Mortibus Persecutorum''

("On the Deaths of the Persecutors") ch. 35–34 With the passage in 313 AD of the

Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan ( la, Edictum Mediolanense; el, Διάταγμα τῶν Μεδιολάνων, ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. ( ...

, in which the Roman Emperors Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

and Licinius

Valerius Licinianus Licinius (c. 265 – 325) was Roman emperor from 308 to 324. For most of his reign he was the colleague and rival of Constantine I, with whom he co-authored the Edict of Milan, AD 313, that granted official toleration to C ...

legalised the Christian religion, persecution of Christians by the Roman state ceased.

The Emperor Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

was exposed to Christianity by his mother, Helena. There is scholarly controversy, however, as to whether Constantine adopted his mother's Christianity in his youth, or whether he adopted it gradually over the course of his life.R. Gerberding and J. H. Moran Cruz, ''Medieval Worlds'' (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004) p. 55

In 313, he and

In 313, he and Licinius

Valerius Licinianus Licinius (c. 265 – 325) was Roman emperor from 308 to 324. For most of his reign he was the colleague and rival of Constantine I, with whom he co-authored the Edict of Milan, AD 313, that granted official toleration to C ...

issued the Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan ( la, Edictum Mediolanense; el, Διάταγμα τῶν Μεδιολάνων, ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. ( ...

, officially legalizing Christian worship. In 316, he acted as a judge in a North African dispute concerning the Donatist

Donatism was a Christian sect leading to a schism in the Church, in the region of the Church of Carthage, from the fourth to the sixth centuries. Donatists argued that Christian clergy must be faultless for their ministry to be effective and the ...

controversy. More significantly, in 325 he summoned the Council of Nicaea, effectively the first Ecumenical Council

An ecumenical council, also called general council, is a meeting of bishops and other church authorities to consider and rule on questions of Christian doctrine, administration, discipline, and other matters in which those entitled to vote ar ...

(unless the Council of Jerusalem is so classified), to deal mostly with the Arian controversy, but which also issued the Nicene Creed, which among other things professed a belief in ''One Holy Catholic Apostolic Church'', the start of Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

.

The reign of Constantine established a precedent for the position of the Christian Emperor in the Church. Emperors considered themselves responsible to God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

for the spiritual health of their subjects, and thus they had a duty to maintain orthodoxy. The emperor did not decide doctrine — that was the responsibility of the bishops — rather his role was to enforce doctrine, root out heresy, and uphold ecclesiastical unity. The emperor ensured that God was properly worshiped in his empire; what proper worship consisted of was the responsibility of the church. This precedent would continue until certain emperors of the fifth and six centuries sought to alter doctrine by imperial edict without recourse to councils, though even after this Constantine's precedent generally remained the norm.

The reign of Constantine did not bring the total unity of Christianity within the Empire. His successor in the East, Constantius II

Constantius II (Latin: ''Flavius Julius Constantius''; grc-gre, Κωνστάντιος; 7 August 317 – 3 November 361) was Roman emperor from 337 to 361. His reign saw constant warfare on the borders against the Sasanian Empire and Germanic ...

, was an Arian who kept Arian bishops at his court and installed them in various sees, expelling the orthodox bishops.

Constantius's successor, Julian, known in the Christian world as ''Julian the Apostate'', was a philosopher who upon becoming emperor renounced Christianity and embraced a Neo-platonic

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some ide ...

and mystical form of paganism shocking the Christian establishment. Intent on re-establishing the prestige of the old pagan beliefs, he modified them to resemble Christian traditions such as the episcopal structure and public charity (hitherto unknown in Roman paganism). Julian eliminated most of the privileges and prestige previously afforded to the Christian Church. His reforms attempted to create a form of religious heterogeneity by, among other things, reopening pagan temples, accepting Christian bishops previously exiled as heretics, promoting Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in t ...

, and returning Church lands to their original owners. However, Julian's short reign ended when he died while campaigning in the East. Christianity came to dominance during the reign of Julian's successors, Jovian

Jovian is the adjectival form of Jupiter and may refer to:

* Jovian (emperor) (Flavius Iovianus Augustus), Roman emperor (363–364 AD)

* Jovians and Herculians, Roman imperial guard corps

* Jovian (lemur), a Coquerel's sifaka known for ''Zoboomafo ...

, Valentinian I

Valentinian I ( la, Valentinianus; 32117 November 375), sometimes called Valentinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 364 to 375. Upon becoming emperor, he made his brother Valens his co-emperor, giving him rule of the eastern provinces. Val ...

, and Valens

Valens ( grc-gre, Ουάλης, Ouálēs; 328 – 9 August 378) was Roman emperor from 364 to 378. Following a largely unremarkable military career, he was named co-emperor by his elder brother Valentinian I, who gave him the eastern half of ...

(the last Eastern Arian Christian Emperor).

However, although state persecution ended, by the early fifth century there was still much remaining prejudice within the empire against Christians: a popular proverb at the time was, according to Augustine of Hippo, "No rain! It's all the fault of the Christians."

State religion of Rome

On February 27, 380, the Roman Empire officially adoptedTrinitarian

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the Fa ...

Nicene Christianity

The original Nicene Creed (; grc-gre, Σύμβολον τῆς Νικαίας; la, Symbolum Nicaenum) was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. In 381, it was amended at the First Council of Constantinople. The amended form is ...

as its state religion. Prior to this date, Constantius II

Constantius II (Latin: ''Flavius Julius Constantius''; grc-gre, Κωνστάντιος; 7 August 317 – 3 November 361) was Roman emperor from 337 to 361. His reign saw constant warfare on the borders against the Sasanian Empire and Germanic ...

(337-361) and Valens

Valens ( grc-gre, Ουάλης, Ouálēs; 328 – 9 August 378) was Roman emperor from 364 to 378. Following a largely unremarkable military career, he was named co-emperor by his elder brother Valentinian I, who gave him the eastern half of ...

(364-378) had personally favored Arian or Semi-Arianism

Semi-Arianism was a position regarding the relationship between God the Father and the Son of God, adopted by some 4th-century Christians. Though the doctrine modified the teachings of Arianism, it still rejected the doctrine that Father, Son, ...

forms of Christianity, but Valens' successor Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

supported the Trinitarian doctrine as expounded in the Nicene Creed.

On this date, Theodosuis I decreed that only the followers of Trinitarian Christianity were entitled to be referred to as Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Christians, while all others were to be considered to be practicers of heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

, which was to be considered illegal. In 385, this new legal authority of the Church resulted in the first case of many to come, of the capital punishment of a heretic, namely Priscillian.

Review of Church policies towards heresy, including capital punishment (see Synod at Saragossa).

In the several centuries of state sponsored Christianity that followed, pagans and heretical Christians were routinely persecuted by the Empire and the many kingdoms and countries that later occupied the place of the Empire, but some Germanic tribes

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and e ...

remained Arian well into the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

.

Theology and heresy

Heresies

The earliest controversies were generallyChristological

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Di ...

in nature; that is, they were related to Jesus' (eternal) divinity or humanity. Docetism

In the history of Christianity, docetism (from the grc-koi, δοκεῖν/δόκησις ''dokeĩn'' "to seem", ''dókēsis'' "apparition, phantom") is the heterodox doctrine that the phenomenon of Jesus, his historical and bodily existence, a ...

held that Jesus' humanity was merely an illusion, thus denying the incarnation. Arianism held that Jesus, while not merely mortal, was not eternally divine and was, therefore, of lesser status than God the Father (). Modalism

Modalistic Monarchianism, also known as Modalism or Oneness Christology, is a Christian theology upholding the oneness of God as well as the divinity of Jesus; as a form of Monarchianism, it stands in contrast with Trinitarianism. Modalistic Monar ...

(also called Sabellianism

In Christianity, Sabellianism is the Western Church equivalent to Patripassianism in the Eastern Church, which are both forms of theological modalism. Condemned as heresy, Modalism is the belief that the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are three diff ...

or Patripassianism

In Christian theology, historically patripassianism (as it is referred to in the Western church) is a version of Sabellianism in the Eastern church (and a version of modalism, modalistic monarchianism, or modal monarchism). Modalism is the belief ...

) is the belief that the Father

A father is the male parent of a child. Besides the paternal bonds of a father to his children, the father may have a parental, legal, and social relationship with the child that carries with it certain rights and obligations. An adoptive fathe ...

, Son

A son is a male offspring; a boy or a man in relation to his parents. The female counterpart is a daughter. From a biological perspective, a son constitutes a first degree relative.

Social issues

In pre-industrial societies and some current c ...

, and Holy Spirit are three different modes or aspects of God, as opposed to the Trinitarian

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the Fa ...

view of three distinct persons or hypostases within the Godhead. Many groups held dualistic beliefs, maintaining that reality was composed into two radically opposing parts: matter, usually seen as evil, and spirit, seen as good. Others held that both the material and spiritual worlds were created by God and were therefore both good, and that this was represented in the unified divine and human natures of Christ.

The development of doctrine, the position of orthodoxy, and the relationship between the various opinions is a matter of continuing academic debate. Since most Christians today subscribe to the doctrines established by the Nicene Creed, modern Christian theologians tend to regard the early debates as a unified orthodox position (see also Proto-orthodox Christianity

The term proto-orthodox Christianity or proto-orthodoxy is often erroneously thought to have been coined by New Testament scholar Bart D. Ehrman, who borrowed it from Bentley Layton (a major scholar of Gnosticism and Coptologist at Yale), and des ...

and Palaeo-orthodoxy) against a minority of heretics. Other scholars, drawing upon, among other things, distinctions between Jewish Christians

Jewish Christians ( he, יהודים נוצרים, yehudim notzrim) were the followers of a Jewish religious sect that emerged in Judea during the late Second Temple period (first century AD). The Nazarene Jews integrated the belief of Jesus a ...

, Pauline Christianity, Pauline Christians, and other groups such as Gnosticism, Gnostics and Marcionites, argue that early Christianity was fragmented, with contemporaneous competing orthodoxies.

Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers

Later Church Fathers wrote volumes of theological texts, including Augustine of Hippo, Augustine, Gregory of Nazianzus, Gregory Nazianzus, Cyril of Jerusalem, Ambrose, Ambrose of Milan, Jerome, and others. What resulted was a golden age of literary and scholarly activity unmatched since the days of Virgil and Horace. Some of these fathers, such as John Chrysostom and Athanasius of Alexandria, Athanasius, suffered exile, persecution, or martyrdom from Arian Byzantine Emperors. Many of their writings are translated into English in the compilations of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers.Ecumenical councils

Council of Nicaea (325)

Emperor Constantine convened this council to settle a controversial issue, the relation between Jesus Christ and God the Father. The Emperor wanted to establish universal agreement on it. Representatives came from across the Empire, subsidized by the Emperor. Previous to this council, the bishops would hold local councils, such as the Council of Jerusalem, but there had been no universal, or ecumenical, council. The council drew up a creed, the Nicene Creed#The original Nicene Creed of 325, original Nicene Creed, which received nearly unanimous support. The council's description of "God's only-begotten Son", Jesus Christ, as of the homoousios, same substance with God the Father became a touchstone of Christian Trinitarianism. The council also addressed the issue of dating Easter (see Quartodecimanism and Easter controversy), recognised the right of the see of Alexandria to jurisdiction outside of its own province (by analogy with the jurisdiction exercised by Rome) and the prerogatives of the churches in Antioch and the other provinces and approved the custom by which Jerusalem in Christianity, Jerusalem was honoured, but without the metropolitan dignity. The Council was opposed by the Arians, and Constantine tried to reconcile Arius, after whom Arianism is named, with the Church. Even when Arius died in 336, one year before the death of Constantine, the controversy continued, with various separate groups espousing Arian sympathies in one way or another."Arianism." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005 In 359, a double council of Eastern and Western bishops affirmed a formula stating that the Father and the Son were similar in accord with the scriptures, the crowning victory for Arianism. The opponents of Arianism rallied, but in the First Council of Constantinople in 381 marked the final victory of Nicene orthodoxy within the Empire, though Arianism had by then spread to the Germanic tribes, among whom it gradually disappeared after the conversion of the Franks to Catholicism in 496.Council of Constantinople (381)

The council approved the current form of the Nicene Creed as used in the Eastern Orthodox Church and Oriental Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodox churches, but, except when Greek language, Greek is used, with two additional Latin phrases ("Deum de Deo" and "Filioque") in the West. The form used by the Armenian Apostolic Church, which is part of Oriental Orthodoxy, has many more additions. This fuller creed may have existed before the Council and probably originated from the baptismal creed of Constantinople.

The council also condemned Apollinarism,"Constantinople, First Council of." Cross, F. L., ed. ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church''. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005 the teaching that there was no human mind or soul in Christ. It also granted Constantinople honorary precedence over all churches save Rome.

The council did not include Western bishops or Roman legates, but it was accepted as ecumenical in the West.

The council approved the current form of the Nicene Creed as used in the Eastern Orthodox Church and Oriental Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodox churches, but, except when Greek language, Greek is used, with two additional Latin phrases ("Deum de Deo" and "Filioque") in the West. The form used by the Armenian Apostolic Church, which is part of Oriental Orthodoxy, has many more additions. This fuller creed may have existed before the Council and probably originated from the baptismal creed of Constantinople.

The council also condemned Apollinarism,"Constantinople, First Council of." Cross, F. L., ed. ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church''. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005 the teaching that there was no human mind or soul in Christ. It also granted Constantinople honorary precedence over all churches save Rome.

The council did not include Western bishops or Roman legates, but it was accepted as ecumenical in the West.

Council of Ephesus (431)

Theodosius II called the council to settle the Nestorian controversy. Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople, opposed use of the term Theotokos (Greek Η Θεοτόκος, "God-bearer")."Nestorius." Cross, F. L., ed. ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church''. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005 This term had long been used by orthodox writers, and it was gaining popularity along with devotion to Mary as Mother of God. He reportedly taught that there were two separate persons in the incarnate Christ, though whether he actually taught this is disputed. The council deposed Nestorius, repudiated Nestorianism as heresy, heretical, and proclaimed the Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus, Mary as the Theotokos. After quoting the Nicene Creed in its original form, as at the First Council of Nicaea, without the alterations and additions made at the First Council of Constantinople, it declared it "unlawful for any man to bring forward, or to write, or to compose a different (ἑτέραν) Faith as a rival to that established by the holy Fathers assembled with the Holy Ghost in Nicæa." The result of the Council led to political upheaval in the church, as the Assyrian Church of the East and the Persian Sasanian Empire supported Nestorius, resulting in the Nestorian Schism, which separated the Church of the East from the Latin Byzantine Church.Council of Chalcedon (451)

Biblical canon

The Biblical canon—is the set of books Christians regard as divinely inspired and thus constituting the Christian Bible-- Development of the New Testament canon, developed over time. While there was a good measure of debate in the Early Church over the New Testament canon, the major writings were accepted by almost all Christians by the middle of the 2nd century.Constantine commissions Bibles

In 331, Constantine I and Christianity, Constantine I commissioned Eusebius to deliver Fifty Bibles of Constantine, "Fifty Bibles" for the Church of Constantinople. Athanasius (''Apol. Const. 4'') recorded Alexandrian scribes around 340 preparing Bibles for Constans. Little else is known, though there is plenty of speculation. For example, it is speculated that this may have provided motivation for Development of the Christian Biblical canon, canon lists, and that Codex Vaticanus Graecus 1209, Codex Vaticanus, Codex Sinaiticus, Sinaiticus and Codex Alexandrinus, Alexandrinus are examples of these Bibles. Together with the Peshitta, these are the earliest extant Christian Bibles.Current canon

In his Easter letter of 367, Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, gave a list of exactly the same books as what would become the New Testament canon, and he used the word "canonised" (''kanonizomena'') in regards to them. The African Synod of Hippo, in 393, approved the New Testament, as it stands today, together with the Septuagint books, a decision that was repeated by the Council of Carthage (397) and the Council of Carthage (419). These councils were under the authority of Augustine of Hippo, St. Augustine, who regarded the canon as already closed. Pope Damasus I's Council of Rome in 382, if the ''Decretum Gelasianum'' is correctly associated with it, issued a biblical canon identical to that mentioned above, or if not the list is at least a Christianity in the 6th century, sixth-century compilation. Likewise, Damasus's commissioning of the Latin Vulgate edition of the Bible, ''c''. 383, was instrumental in the fixation of the canon in the West. In 405, Pope Innocent I sent a list of the sacred books to a Gallic bishop, Exuperius, Exsuperius of Toulouse. When these bishops and councils spoke on the matter, however, they were not defining something new, but instead "were ratifying what had already become the mind of the Church." Thus, from the 4th century, there existed unanimity in the West concerning the New Testament canon (as it is today), and by the Christianity in the 5th century, fifth century the East, with a few exceptions, had come to accept the Book of Revelation and thus had come into harmony on the matter of the canon. Nonetheless, a full dogmatic articulation of the canon was not made until the Christianity in the 16th century, 16th century and Christianity in the 17th century, 17th century.Church structure within the Empire

Dioceses

After legalisation, the Church adopted the same organisational boundaries as the Empire: geographical provinces, called dioceses, corresponding to imperial governmental territorial division. The bishops, who were located in major urban centers by pre-legalisation tradition, thus oversaw each diocese. The bishop's location was his "seat", or "see"; among the sees, Pentarchy, five held special eminence: Rome, Constantinople, Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria. The prestige of these sees depended in part on their apostolic founders, from whom the bishops were therefore the spiritual successors, e.g., St. Mark as founder of the See of Alexandria, St. Peter of the See of Rome, etc. There were other significant elements: Jerusalem was the location of Christ's death and resurrection, the site of a 1st-century council, etc., see also Jerusalem in Christianity. Antioch was where Jesus' followers were first labelled as Christians, it was used in a derogatory way to berate the followers of Jesus the Christ. Rome was where SS. Peter and Paul had been martyred (killed), Constantinople was the "New Rome" where Constantine had moved his capital c. 330, and, lastly, all these cities had important relics.The Pentarchy

By the 5th century, the ecclesiastical had evolved a hierarchical "pentarchy" or system of five sees (patriarchates), with a settled order of precedence, had been established. Rome, as the ancient capital and once largest city of the empire, was understandably given certain primacy within the pentarchy into which Christendom was now divided; though it was and still held that the patriarch of Rome was the first among equals. Constantinople was considered second in precedence as the new capital of the empire. Among these dioceses, the Pentarchy, five with special eminence were Pope, Rome, Patriarch of Constantinople, Constantinople, Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Patriarch of Antioch, Antioch, and Patriarch of Alexandria, Alexandria. The prestige of most of these sees depended in part on their apostolic founders, from whom the bishops were therefore the spiritual successors. Though the patriarch of Rome was still held to be the first among equals, Constantinople was second in precedence as the new capital of the empire.Papacy and Primacy

The Bishop of Rome and has the title of Pope and the office is the "papacy." As a bishopric, its origin is consistent with the development of an episcopal structure in the 1st century. The papacy, however, also carries the notion of primacy: that the See of Rome is pre-eminent among all other sees. The origins of this concept are historically obscure; theologically, it is based on three ancient Christian traditions: (1) that the apostle Peter was pre-eminent among the apostles, see Primacy of Simon Peter, (2) that Peter ordained his successors for the Roman See, and (3) that the bishops are the successors of the apostles (apostolic succession). As long as the Papal See also happened to be the capital of the Western Empire, the prestige of the Bishop of Rome could be taken for granted without the need of sophisticated theological argumentation beyond these points; after its shift to Milan and then Ravenna, however, more detailed arguments were developed based on etc. Nonetheless, in antiquity the Petrine and Apostolic quality, as well as a "primacy of respect", concerning the Roman See went unchallenged by emperors, eastern patriarchs, and the Eastern Church alike. The Ecumenical Council of Constantinople in 381 affirmed the primacy of Rome. Though the appellate jurisdiction of the Pope, and the position of Constantinople, would require further doctrinal clarification, by the close of Antiquity the primacy of Rome and the sophisticated theological arguments supporting it were fully developed. Just what exactly was entailed in this primacy, and its being exercised, would become a matter of controversy at certain later times.Outside the Roman Empire

Christianity was by no means confined to the Roman Empire during late antiquity.Church of the East

Historically, the most widespread Christian church in Asia was the Church of the East, the Christian church of Sasanian Empire, Sasanian Persia. This church is often known as the Nestorian Church, due to its adoption of the doctrine of Nestorianism, which emphasized the disunity of the divine and human natures of Christ. It has also been known as the Persia Church, the East Syrian Church, the Assyrian Church, and, in China, as the "Luminous Religion". The Church of the East developed almost wholly apart from the Early centers of Christianity, Greek and Roman churches. In the 5th century it endorsed the doctrine of Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople from 428 to 431, especially following the Nestorian Schism after the condemnation of Nestorius forheresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

at the First Council of Ephesus. For at least twelve hundred years the Church of the East was noted for its missionary zeal, its high degree of Laity, lay participation, its superior educational standards and cultural contributions in less developed countries, and its fortitude in the face of persecution.

Persian Empires

The Church of the East had its inception at a very early date in the buffer zone between the Roman Empire and the Parthian Empire, Parthian in Upper Mesopotamia. Edessa, Mesopotamia, Edessa (now Şanlıurfa) in northwestern Mesopotamia was from apostolic times the principal center of Syriac language, Syriac-speaking Christianity. The missionary movement in the East began which gradually spread throughout Mesopotamia and Persia and by AD 280. When Constantine converted to Christianity the Persian Empire, suspecting a new "enemy within", became violently anti-Christian. The great persecution fell upon the Christians in Persia about the year 340. Though the religious motives were never unrelated, the primary cause of the persecution was political. Sometime before the death of Shapur II in 379, the intensity of the persecution slackened. Tradition calls it a forty-year persecution, lasting from 339-379 and ending only with Shapur's death.Caucasus

Christianity became the official religion of Armenia in 301 or 314, when Christianity was still illegal in the Roman Empire. Some claim the Armenian Apostolic Church was founded by Gregory the Illuminator of the late third – early fourth centuries while they trace their origins to the missions of Bartholomew the Apostle and Thaddeus (Jude the Apostle) in the 1st century. Christianity in Georgia (country), Georgia (ancient Caucasian Iberia, Iberia) extends back to the Christianity in the 4th century, 4th century, if not earlier."Georgia, Church of." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005 The Iberian king, Mirian III of Iberia, Mirian III, converted to Christianity, probably in 326.Ethiopia

According to the fourth-century Western historian Tyrannius Rufinus, Rufinius, it was Saint Frumentius, Frumentius who brought Christianity to Ethiopia (the city of Axum) and served as its first bishop, probably shortly after 325.Germanic peoples

The Germanic people underwent gradual Christianization from Late Antiquity. In the 4th century, the early process of Christianization of the various Germanic peoples, Germanic people was partly facilitated by the prestige of the Christian

The Germanic people underwent gradual Christianization from Late Antiquity. In the 4th century, the early process of Christianization of the various Germanic peoples, Germanic people was partly facilitated by the prestige of the Christian Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

amongst European pagans. Until the decline of the Roman Empire, the Germanic tribes who had migrated there (with the exceptions of the Saxons, Franks, and Lombards, see below) had converted to Christianity.Padberg 1998, 26 Many of them, notably the Goths and Vandals, adopted Arianism instead of the Trinity, Trinitarian (a.k.a. First Council of Nicea, Nicene or ''orthodox'') beliefs that were dogmatically defined by the Church Fathers in the Nicene Creed and Council of Chalcedon. The gradual rise of Germanic Christianity was, at times, voluntary, particularly amongst groups associated with the Roman Empire.

From the 6th century AD, Germanic tribes were converted (and re-converted) by Missionary, missionaries of the Catholic Church.

Many Goths converted to Christianity as individuals outside the Roman Empire. Most members of other tribes converted to Christianity when their respective tribes settled within the Empire, and most Franks and Anglo-Saxons converted a few generations later. During the later centuries following the Fall of Rome, as East–West Schism, schism between the dioceses loyal to the Pope, Pope of Rome in the Catholic Church, West and those loyal to the other Patriarchs in the Eastern Orthodox Church, East, most of the Germanic peoples (excepting the Crimean Goths and a few other eastern groups) would gradually become strongly allied with the Catholic Church in the West, particularly as a result of the reign of Charlemagne.

Goths

In the 3rd century, East-Germanic peoples migrated into Scythia. Gothic culture and identity emerged from various East-Germanic, local, and Roman influences. In the same period, Gothic raiders took captives among the Romans, including many Christians, (and Roman-supported raiders took captives among the Goths). Wulfila or Ulfilas was the son or grandson of Christian captives from Sadagolthina in Cappadocia. In 337 or 341, Wulfila became the first bishop of the (Christian) Goths. By 348, one of the (Pagan) Gothic kings () began persecuting the Christian Goths, and Wulfila and many other Christian Goths fled to Moesia Secunda (in modern Bulgaria) in the Roman Empire.Philostorgius via Photius, ''Epitome of the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius'', book 2, chapter 5. Other Christians, including Wereka and Batwin, Wereka, Batwin, and Sabbas the Goth, Saba, died in later persecutions. Between 348 and 383, Wulfila translated the Bible into the Gothic language. Thus some Arian Christians in the west used the vernacular languages, in this case including Gothic and Latin, for services, as did Christians in the eastern Roman provinces, while most Christians in the western provinces used Latin.Franks and Alemanni

The Franks and their ruling Merovingian dynasty, that had migrated to Gaul from the 3rd century had remained pagan at first. On Christmas 496,497 or 499 are also possible; Padberg 1998: 53 however, Clovis I following his victory at the Battle of Tolbiac converted to the ''orthodox'' faith of the Catholic Church and let himself be baptised at Rheims. The details of this event have been passed down by Gregory of Tours.Monasticism

Christian monasticism, Monasticism is a form of asceticism whereby one renounces worldly pursuits () and concentrates solely on heavenly and spiritual pursuits, especially by the virtues humility, poverty, and chastity. It began early in the Church as a family of similar traditions, modeled upon Scriptural examples and ideals, and with roots in certain strands of Judaism. St. John the Baptist is seen as the archetypical monk, and monasticism was also inspired by the organisation of the Apostolic community as recorded in ''Acts of the Apostles''. There are two forms of monasticism: hermit, eremitic and cenobitic. Eremitic monks, or hermits, live in solitude, whereas cenobitic monks live in communities, generally in a monastery, under a rule (or code of practice) and are governed by an abbot. Originally, all Christian monks were hermits, following the example of Anthony the Great. However, the need for some form of organised spiritual guidance lead Saint Pachomius in 318 to organise his many followers in what was to become the first monastery. Soon, similar institutions were established throughout the Egyptian desert as well as the rest of the eastern half of the Roman Empire. Central figures in the development of monasticism were, in the East, St. Basil of Caesarea, Basil the Great, and St. Benedict in the West, who created the famous Rule of Saint Benedict, Benedictine Rule, which would become the most common rule throughout the Middle Ages.See also

* Ante-Nicene Period * Church Fathers * Christian monasticism * Christianization * Development of the New Testament canon * History of Calvinist-Arminian debate * History of Christianity * History of Christian theology * History of Oriental Orthodoxy * History of the Eastern Orthodox Church * History of the Roman Catholic Church * List of Church Fathers * Patristics * State church of the Roman Empire * Timeline of Christian missions * Timeline of ChristianityNotes

Print resources

* * * * *External links

History of Christianity Reading Room:

Extensive online resources for the study of global church history (Tyndale Seminary).

Sketches of Church History

From AD 33 to the Reformation by Rev. J. C Robertson, M.A, Canon of Canterbury *

Theandros

a journal of Orthodox theology and philosophy, containing articles on early Christianity and patristic studies.

Fourth-Century Christianity

{{History of Europe Christianity in late antiquity,