Chief Noc-A-Homa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Chief Noc-A-Homa was a

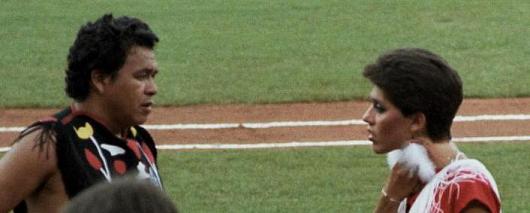

In 1983, Chief Noc-A-Homa was joined by "Princess Win-A-Lotta" who was portrayed by Kim Calos. After she suffered a serious back injury in a car accident that cut her season short, the Braves chose not to bring Princess Win-A-Lotta back in 1984.

In 1983, Chief Noc-A-Homa was joined by "Princess Win-A-Lotta" who was portrayed by Kim Calos. After she suffered a serious back injury in a car accident that cut her season short, the Braves chose not to bring Princess Win-A-Lotta back in 1984.

mascot

A mascot is any human, animal, or object thought to bring luck, or anything used to represent a group with a common public identity, such as a school, professional sports team, society, military unit, or brand name. Mascots are also used as fi ...

for the American professional baseball

Professional baseball is organized baseball in which players are selected for their talents and are paid to play for a specific team or club system. It is played in leagues and associated farm teams throughout the world.

Modern professional ...

team Atlanta Braves

The Atlanta Braves are an American professional baseball team based in the Atlanta metropolitan area. The Braves compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (NL) East division. The Braves were founded in Bos ...

from 1966 to 1985. He was primarily played by Levi Walker, Jr. After being a mascot for the Braves franchise for two decades the Atlanta Braves retired the mascot before the 1986 season.

History

Origin

The mascot's tradition started in 1964 while the franchise was in Milwaukee. The first recorded instance of the concept came when a 16-year-old high school student named Tim Rynders set up atipi

A tipi , often called a lodge in English, is a conical tent, historically made of animal hides or pelts, and in more recent generations of canvas, stretched on a framework of wooden poles. The word is Siouan, and in use in Dakhótiyapi, Lakȟó ...

in the centerfield bleachers. He danced and ignited smoke bombs when the Braves scored. While the concept started in Milwaukee, there was no name associated with the mascot until the team moved to Atlanta.

During the 1966 season, the Atlanta Braves held a contest to name their mascot. Mary Truesdale, a Greenville, SC resident was one of three people who entered "Chief Noc-A-Homa" the winning name chosen and announced by the Braves on July 26, 1966.

The first Chief Noc-A-Homa was portrayed by a Georgia State college student named Larry Hunn. During the 1968 season, after training from Hunn, Tim Minors took over as Noc-A-Homa.

In 1968, Levi Walker approached the Braves about having a real Native American portray the chief. Having grown weary of life as an insurance salesmen, warehouse worker and plumber, Walker was hired for the 1969 season.

On May 26, 1969 Walker set his tipi on fire after lighting a smoke bomb celebrating a home run by Clete Boyer

Cletis Leroy "Clete" Boyer (February 9, 1937 – June 4, 2007) was an American professional baseball third baseman — who occasionally played shortstop and second base — in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Kansas City Athletics (1955–57 ...

. After dancing around the tipi behind the left field fence, Chief Noc-A-Homa went inside but came charging out when flames shot out two feet into the air. The fire was quickly put out and after the game Walker said the smoke bombs were sabotaged. Walker became synonymous with Noc-A-Homa and he kept the job for 17 years, serving as the mascot until it was retired before the 1986 season. Walker, a Michigan native and member of the Odawa tribe, was the most famous version of Noc-A-Homa.

Chief Noc-A-Homa could be found at every home game in a tipi beyond the left field seats. There were the times when the tipi was taken down to add more seats. Superstitious fans sometimes blamed losing streaks on the missing tipi. In 1982, when the Braves opened the season with 13 wins, owner Ted Turner removed the tipi to sell more seats. The Braves lost 19 of their next 21 games and fell to second place. Turner told team management to put the tipi back up and the Braves went on to win the National League West.

Princess Win-A-Lotta

Retirement

In 1986, Walker and the Braves mutually agreed to end their relationship due to disagreements about pay and missed dates. Walker made $60 per game and received $4,860 for 80 appearances.Comments by Russell Means

In 1972,Russell Means

Russell Charles Means (November 10, 1939 – October 22, 2012) was an Oglala Lakota activist for the rights of Native Americans, libertarian political activist, actor, musician, and writer. He became a prominent member of the American In ...

filed a $9 million lawsuit against the Cleveland Indians

The Cleveland Guardians are an American professional baseball team based in Cleveland. The Guardians compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) Central division. Since , they have played at Progressive Fi ...

for their use of "Chief Wahoo." Means also objected to the Braves use of Chief Noc-A-Homa. Means said "What if it was the Atlanta Germans and after every home run a German dressed in military uniform began hitting a Jew on the head with a baseball bat?" Means was unaware that Chief Noc-A-Homa was portrayed by a Native American. For a week, controversy raged. Walker went on radio talk shows to defend Noc-A-Homa. Walker said "I think Indians can be proud that their names are used with professional sports teams.” Ultimately Noc-A-Homa survived the controversy.

See also

* Atlanta Braves tomahawk chop and name controversy *Native American mascot controversy

Since the 1960s, the issue of Native American and First Nations names and images being used by sports teams as mascots has been the subject of increasing public controversy in the United States and Canada. This has been a period of rising ...

*List of sports team names and mascots derived from Indigenous peoples

The practice of deriving sports team names, imagery, and mascots from Indigenous peoples of North America is a significant phenomenon in the United States and Canada. The popularity of the American Indian in global culture has led to a number of ...

References