Charles X on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles X (born Charles Philippe, Count of Artois; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was

Charles Philippe of France was born in 1757, the youngest son of the Dauphin Louis and his wife, the Dauphine Marie Josèphe, at the

Charles Philippe of France was born in 1757, the youngest son of the Dauphin Louis and his wife, the Dauphine Marie Josèphe, at the

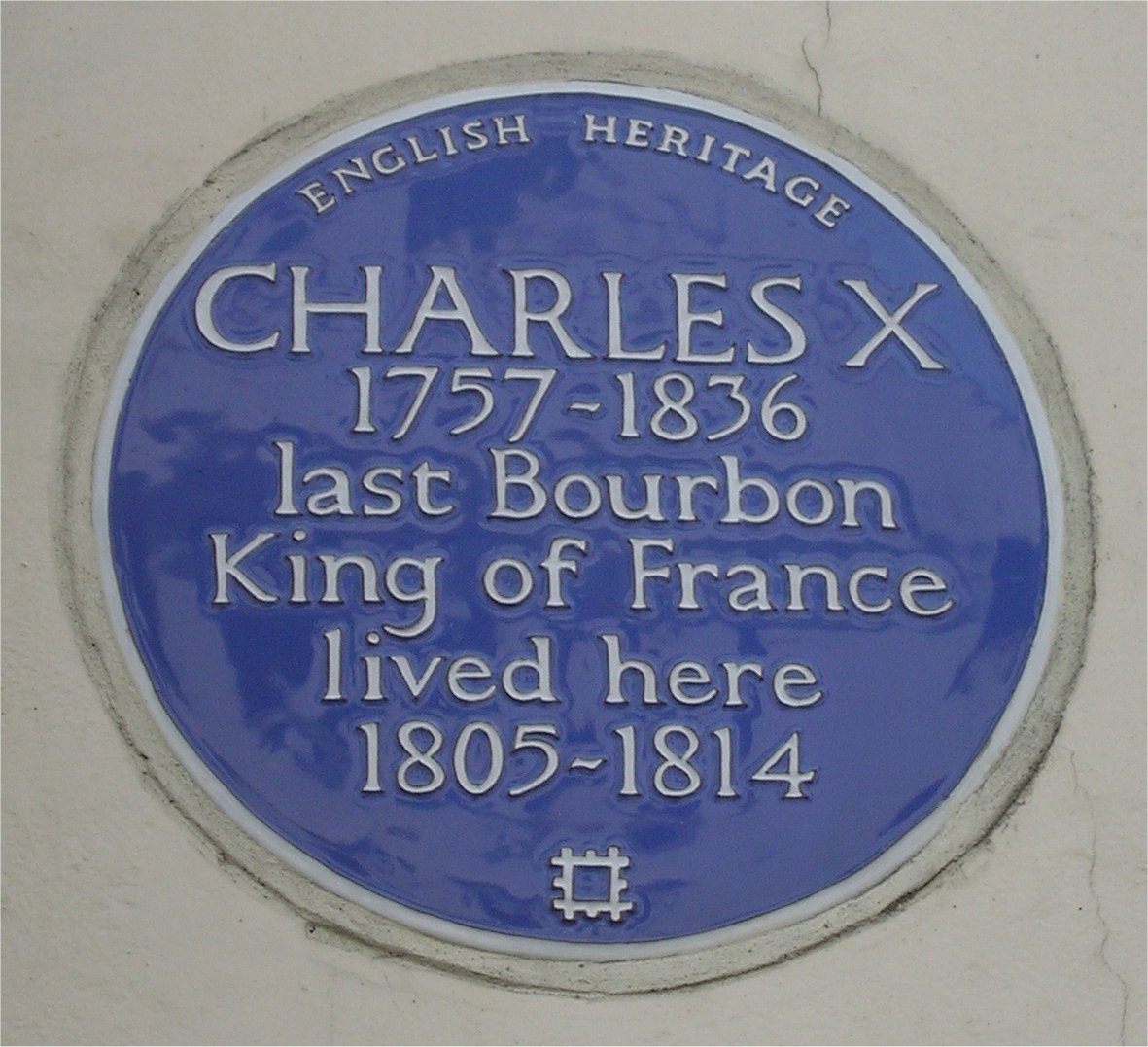

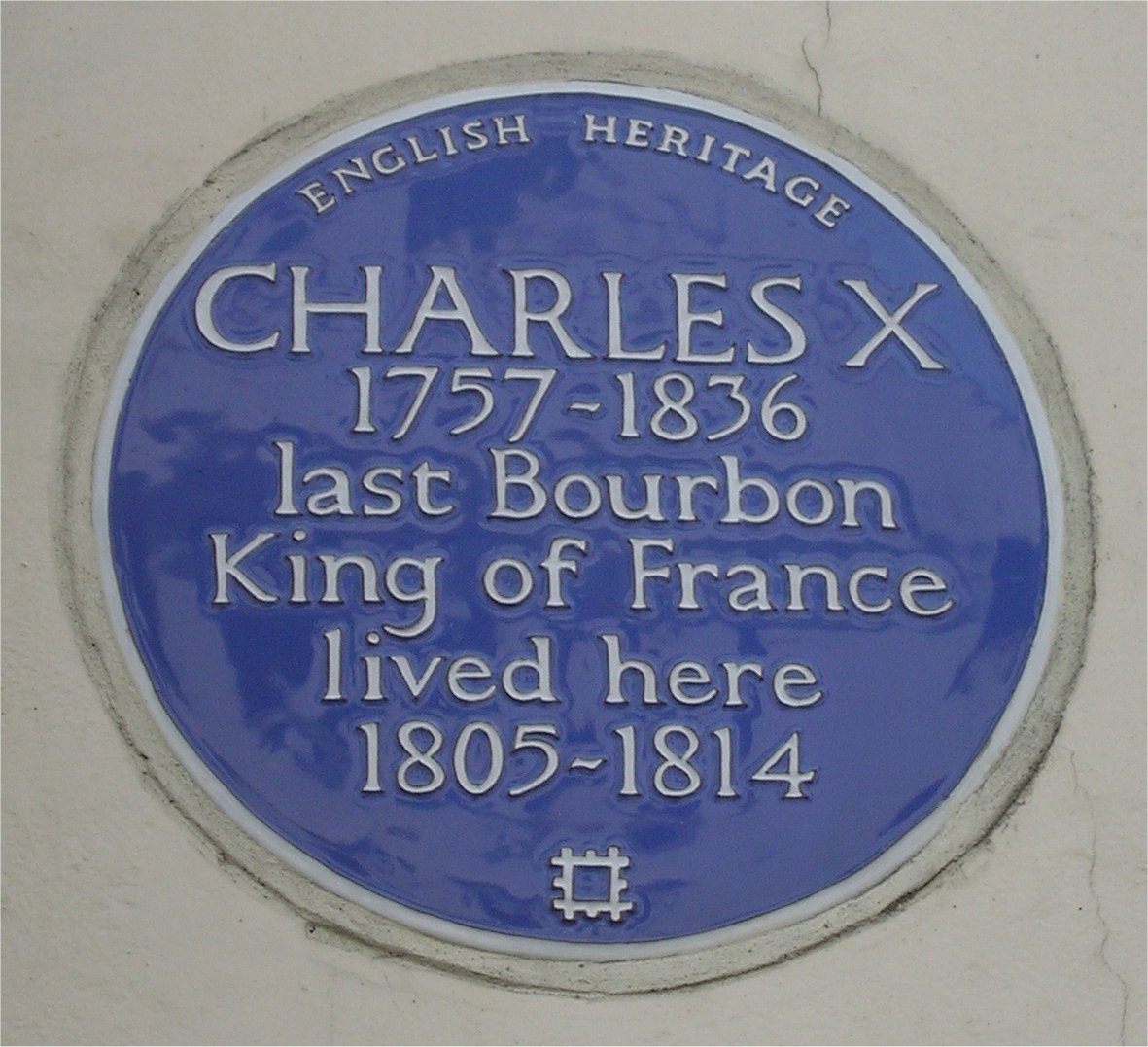

Charles and his family decided to seek refuge in

Charles and his family decided to seek refuge in

In January 1814, Charles covertly left his home in London to join the

In January 1814, Charles covertly left his home in London to join the

The coronation of Charles X therefore appeared to be a compromise between the tradition of the Ancien Régime and the political changes that had taken place since the Revolution. The coronation nevertheless had a limited influence on the population, mentalities no longer being those of yesteryear. From then on, the coronation caused incomprehension in certain sectors of public opinion.

It was

The coronation of Charles X therefore appeared to be a compromise between the tradition of the Ancien Régime and the political changes that had taken place since the Revolution. The coronation nevertheless had a limited influence on the population, mentalities no longer being those of yesteryear. From then on, the coronation caused incomprehension in certain sectors of public opinion.

It was

Like Napoleon and then Louis XVIII before him, Charles X resided mainly at the

Like Napoleon and then Louis XVIII before him, Charles X resided mainly at the

The Chambers convened on 2 March 1830, but Charles's opening speech was greeted by negative reactions from many deputies. Some introduced a bill requiring the King's minister to obtain the support of the Chambers, and on 18 March, 221 deputies, a majority of 30, voted in favor. However, the King had already decided to hold

The Chambers convened on 2 March 1830, but Charles's opening speech was greeted by negative reactions from many deputies. Some introduced a bill requiring the King's minister to obtain the support of the Chambers, and on 18 March, 221 deputies, a majority of 30, voted in favor. However, the King had already decided to hold

When it became apparent that a mob 14,000 strong was preparing to attack, the royal family left Rambouillet and, on 16 August embarked for the United Kingdom on

When it became apparent that a mob 14,000 strong was preparing to attack, the royal family left Rambouillet and, on 16 August embarked for the United Kingdom on

p. 53

/ref>

online free

* Artz, Frederick B. ''Reaction and Revolution 1814–1832'' (1938), covers Europe

online

* Brown, Bradford C. "France, 1830 Revolution." in by Immanuel Ness, ed., ''The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest (2009): 1–8. * Frederking, Bettina. "'Il ne faut pas être le roi de deux peuples': strategies of national reconciliation in Restoration France." ''French History'' 22.4 (2008): 446–468. in English * Rader, Daniel L. ''The Journalists and the July Revolution in France: The Role of the Political Press in the Overthrow of the Bourbon Restoration, 1827–1830'' (Springer, 2013). * Weiner, Margery. ''The French Exiles, 1789–1815'' (Morrow, 1961). * Wolf, John B. ''France 1814–1919: the Rise of a Liberal Democratic Society'' (1940) pp 1–58.

King of France

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the Kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I () as the fir ...

from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother to reigning kings Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

and Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. He spent twenty-three years in ...

, he supported the latter in exile. After the Bourbon Restoration Bourbon Restoration may refer to:

France under the House of Bourbon:

* Bourbon Restoration in France (1814, after the French revolution and Napoleonic era, until 1830; interrupted by the Hundred Days in 1815)

Spain under the Spanish Bourbons:

* Ab ...

in 1814, Charles (as heir-presumptive) became the leader of the ultra-royalist

The Ultra-royalists (french: ultraroyalistes, collectively Ultras) were a French political faction from 1815 to 1830 under the Bourbon Restoration. An Ultra was usually a member of the nobility of high society who strongly supported Roman Cathol ...

s, a radical monarchist faction within the French court that affirmed rule by divine right and opposed the concessions towards liberals and guarantees of civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties ma ...

granted by the Charter of 1814. Charles gained influence within the French court after the assassination of his son Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry, in 1820 and succeeded his brother Louis XVIII in 1824.Munro Price

Munro Price is a British historian noted for his award-winning work on French history.

Early life

Price was born (February 1963) in London to playwright and author Stanley Price and his wife Judy ( Fenton) and raised in Highgate.

Education ...

, ''The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions'', Macmillan, pp. 185–187.

His reign of almost six years proved to be deeply unpopular amongst the liberals in France from the moment of his coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of o ...

in 1825, in which he tried to revive the practice of the royal touch. The governments appointed under his reign reimbursed former landowners for the abolition of feudalism at the expense of bondholders

In finance, a bond is a type of security under which the issuer ( debtor) owes the holder ( creditor) a debt, and is obliged – depending on the terms – to repay the principal (i.e. amount borrowed) of the bond at the maturity date as well a ...

, increased the power of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

, and reimposed capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

for sacrilege

Sacrilege is the violation or injurious treatment of a sacred object, site or person. This can take the form of irreverence to sacred persons, places, and things. When the sacrilegious offence is verbal, it is called blasphemy, and when physical ...

, leading to conflict with the liberal-majority Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourbon R ...

. Charles also approved the French conquest of Algeria

The French invasion of Algeria (; ) took place between 1830 and 1903. In 1827, an argument between Hussein Dey, the ruler of the Deylik of Algiers, and the French consul escalated into a blockade, following which the July Monarchy of France inva ...

as a way to distract his citizens from domestic problems, and forced Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and s ...

to pay a hefty indemnity in return for lifting a blockade and recognizing Haiti's independence. He eventually appointed a conservative government under the premiership of Prince Jules de Polignac

Jules Auguste Armand Marie de Polignac, Count of Polignac (; 14 May 178030 March 1847), then Prince of Polignac, and briefly 3rd Duke of Polignac in 1847, was a French statesman and ultra-royalist politician after the Revolution. He served as pr ...

, who was defeated in the 1830 French legislative election. He responded with the July Ordinances disbanding the Chamber of Deputies, limiting franchise, and reimposing press censorship. Within a week France faced urban riots which led to the July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after French Revolution, the first in 1789. It led to ...

of 1830, which resulted in his abdication and the election of Louis Philippe I as King of the French. Exiled once again, Charles died in 1836 in Gorizia

Gorizia (; sl, Gorica , colloquially 'old Gorizia' to distinguish it from Nova Gorica; fur, label= Standard Friulian, Gurize, fur, label= Southeastern Friulian, Guriza; vec, label= Bisiacco, Gorisia; german: Görz ; obsolete English ''Gori ...

, then part of the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central- Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

. He was the last of the French rulers from the senior branch of the House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spani ...

.

Childhood and adolescence

Charles Philippe of France was born in 1757, the youngest son of the Dauphin Louis and his wife, the Dauphine Marie Josèphe, at the

Charles Philippe of France was born in 1757, the youngest son of the Dauphin Louis and his wife, the Dauphine Marie Josèphe, at the Palace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, u ...

. Charles was created Count of Artois at birth by his grandfather, the reigning King Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reache ...

. As the youngest male in the family, Charles seemed unlikely ever to become king. His eldest brother, Louis, Duke of Burgundy

Louis, Dauphin of France, Duke of Burgundy (16 August 1682 – 18 February 1712), was the eldest son of Louis, Grand Dauphin, and Maria Anna Victoria of Bavaria and grandson of the reigning French king, Louis XIV. He was known as the "Pet ...

, died unexpectedly in 1761, which moved Charles up one place in the line of succession. He was raised in early childhood by Madame de Marsan Madame may refer to:

* Madam, civility title or form of address for women, derived from the French

* Madam (prostitution), a term for a woman who is engaged in the business of procuring prostitutes, usually the manager of a brothel

* ''Madame'' ...

, the Governess of the Children of France. At the death of his father in 1765, Charles's oldest surviving brother, Louis Auguste, became the new Dauphin (the heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

to the French throne). Their mother Marie Josèphe, who never recovered from the loss of her husband, died in March 1767 from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

. This left Charles an orphan at the age of nine, along with his siblings Louis Auguste, Louis Stanislas, Count of Provence, Clotilde ("Madame Clotilde"), and Élisabeth ("Madame Élisabeth").

Louis XV fell ill on 27 April 1774 and died on 10 May of smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

at the age of 64.Antonia Fraser, ''Marie Antoinette: the Journey'', pp. 113–116. His grandson Louis-Auguste succeeded him as King Louis XVI.

Marriage and private life

In November 1773, Charles married Marie Thérèse of Savoy. In 1775, Marie Thérèse gave birth to a boy, Louis Antoine, who was createdDuke of Angoulême

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are r ...

by Louis XVI. Louis-Antoine was the first of the next generation of Bourbons, as the king and the Count of Provence had not fathered any children yet, causing the Parisian ''libellistes'' (pamphleteers who published scandalous leaflets about important figures in court and politics) to lampoon Louis XVI's alleged impotence. Three years later, in 1778, Charles' second son, Charles Ferdinand, was born and given the title of Duke of Berry

Duke of Berry (french: Duc de Berry) or Duchess of Berry (french: Duchesse de Berry) was a title in the Peerage of France. The Duchy of Berry, centred on Bourges, was originally created as an appanage for junior members of the French royal fa ...

. In the same year Queen Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne (; ; née Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last queen of France before the French Revolution. She was born an archduchess of Austria, and was the penultimate child a ...

gave birth to her first child, Marie Thérèse, quelling all rumours that she could not bear children.

Charles was thought of as the most attractive member of his family, bearing a strong resemblance to his grandfather Louis XV.Fraser, pp. 80–81. His wife was considered quite ugly by most contemporaries, and he looked for company in numerous extramarital affairs. According to the Count of Hézecques, "few beauties were cruel to him." Among his lovers was notably Anne Victoire Dervieux. Later, he embarked upon a lifelong love affair with the beautiful Louise de Polastron

Marie Louise d’Esparbès de Lussan, by marriage vicomtesse then comtesse de Polastron ( Bardigues, 19 October 1764 – London, 27 March 1804) was a French lady-in-waiting, known as the mistress of the comte d’Artois, who later reigned as Char ...

, the sister-in-law of Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne (; ; née Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last queen of France before the French Revolution. She was born an archduchess of Austria, and was the penultimate child a ...

's closest companion, the Duchess of Polignac

Yolande Martine Gabrielle de Polastron, Duchess of Polignac (8 September 17499 December 1793) was the favourite of Marie Antoinette, whom she first met when she was presented at the Palace of Versailles in 1775, the year after Marie Antoinette b ...

.

Charles also struck up a firm friendship with Marie Antoinette herself, whom he had first met upon her arrival in France in April 1770 when he was twelve. The closeness of the relationship was such that he was falsely accused by Parisian rumour mongers of having seduced her. As part of Marie Antoinette's social set, Charles often appeared opposite her in the private theatre of her favourite royal retreat, the Petit Trianon

The Petit Trianon (; French for "small Trianon") is a Neoclassical style château located on the grounds of the Palace of Versailles in Versailles, France. It was built between 1762 and 1768 during the reign of King Louis XV of France. ...

. They were both said to be very talented amateur actors. Marie Antoinette played milkmaids, shepherd

A shepherd or sheepherder is a person who tends, herds, feeds, or guards flocks of sheep. ''Shepherd'' derives from Old English ''sceaphierde (''sceap'' 'sheep' + ''hierde'' ' herder'). ''Shepherding is one of the world's oldest occupations, ...

esses, and country ladies, whereas Charles played lovers, valets, and farmers.

A famous story concerning the two involves the construction of the Château de Bagatelle. In 1775, Charles purchased a small hunting lodge in the Bois de Boulogne. He soon had the existing house torn down with plans to rebuild. Marie Antoinette wagered her brother-in-law that the new château could not be completed within three months. Charles engaged the neoclassical architect François-Joseph Bélanger

François-Joseph Bélanger (; 12 April 1744 – 1 May 1818) was a French architect and decorator working in the Neoclassic style.

Life

Born in Paris, Bélanger attended the Académie Royale d'Architecture (1764–1766) where he studied ...

to design the building.Fraser, p. 178.

He won his bet, with Bélanger completing the house in sixty-three days. It is estimated that the project, which came to include manicured gardens, cost over two million livres

The (; ; abbreviation: ₶.) was one of numerous currencies used in medieval France, and a unit of account (i.e., a monetary unit used in accounting) used in Early Modern France.

The 1262 monetary reform established the as 20 , or 80.88 g ...

. Throughout the 1770s, Charles spent lavishly. He accumulated enormous debts, totalling 21 million livres

The (; ; abbreviation: ₶.) was one of numerous currencies used in medieval France, and a unit of account (i.e., a monetary unit used in accounting) used in Early Modern France.

The 1262 monetary reform established the as 20 , or 80.88 g ...

. In the 1780s, King Louis XVI paid off the debts of both his brothers, the Counts of Provence and Artois.

In 1781, Charles acted as a proxy for Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

Joseph II at the christening of his godson, the Dauphin Louis Joseph.

Crisis and French Revolution

Charles's political awakening started with the first great crisis of the monarchy in 1786, when it became apparent that the kingdom was bankrupt from previous military endeavours (in particular theSeven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

and the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

) and needed fiscal reform to survive. Charles supported the removal of the aristocracy's financial privileges, but was opposed to any reduction in the social privileges enjoyed by either the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

or the nobility. He believed that France's finances should be reformed without the monarchy being overthrown. In his own words, it was "time for repair, not demolition."

King Louis XVI eventually convened the Estates General, which had not been assembled for over 150 years, to meet in May 1789 to ratify financial reforms. Along with his sister Élisabeth, Charles was the most conservative member of the family and opposed the demands of the Third Estate (representing the commoner

A commoner, also known as the ''common man'', ''commoners'', the ''common people'' or the ''masses'', was in earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not have any significant social status, especially a member of neither ...

s) to increase their voting power. This prompted criticism from his brother, who accused him of being "plus royaliste que le roi" ("more royalist than the king"). In June 1789, the representatives of the Third Estate declared themselves a National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the r ...

intent on providing France with a new constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

.

In conjunction with the Baron de Breteuil Le Tonnelier de Breteuil was a French surname, held by:

* Louis Nicolas Le Tonnelier de Breteuil (1648–1728), officer of the household of Louis XIV

* François Victor Le Tonnelier de Breteuil

François Victor Le Tonnelier de Breteuil (17 April ...

, Charles had political alliances arranged to depose the liberal minister of finance, Jacques Necker. These plans backfired when Charles attempted to secure Necker's dismissal on 11 July without Breteuil's knowledge, much earlier than they had originally intended. It was the beginning of a decline in his political alliance

A political group is a group consisting of political parties or legislators of aligned ideologies. A technical group is similar to a political group, but with members of differing ideologies.

International terms

Equivalent terms are used differ ...

with Breteuil, which ended in mutual loathing.

Necker's dismissal provoked the storming of the Bastille on 14 July. With the concurrence of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette Charles and his family left France three days later, on 17 July, along with several other courtiers. These included the Duchess of Polignac

Yolande Martine Gabrielle de Polastron, Duchess of Polignac (8 September 17499 December 1793) was the favourite of Marie Antoinette, whom she first met when she was presented at the Palace of Versailles in 1775, the year after Marie Antoinette b ...

, the queen's favourite. His flight was historically attributed to personal fears for his own safety. However recent research indicates that the King had approved his brother's departure in advance, seeing it as a means of ensuring that one close relative would be free to act as a spokesman for the monarchy, after Louis himself had been moved from Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, ...

to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

.

Life in exile

Charles and his family decided to seek refuge in

Charles and his family decided to seek refuge in Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Sa ...

, his wife's native country, where they were joined by some members of the Condé family. Meanwhile, in Paris, Louis XVI was struggling with the National Assembly, which was committed to radical reforms and had enacted the Constitution of 1791. In March 1791, the Assembly also enacted a regency bill that provided for the case of the king's premature death. While his heir Louis-Charles was still a minor, the Count of Provence, the Duke of Orléans or, if either was unavailable, someone chosen by election should become regent, completely passing over the rights of Charles who, in the royal lineage, stood between the Count of Provence and the Duke of Orléans.

Charles meanwhile left Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

(in Italy) and moved to Trier

Trier ( , ; lb, Tréier ), formerly known in English as Trèves ( ;) and Triers (see also names in other languages), is a city on the banks of the Moselle in Germany. It lies in a valley between low vine-covered hills of red sandstone in the ...

in Germany, where his uncle, Clemens Wenceslaus of Saxony, was the incumbent Archbishop-Elector. Charles prepared for a counter-revolutionary

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revolu ...

invasion of France, but a letter by Marie Antoinette postponed it until after the royal family

A royal family is the immediate family of kings/queens, emirs/emiras, sultans/ sultanas, or raja/ rani and sometimes their extended family. The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term pa ...

had escaped from Paris and joined a concentration of regular troops under François Claude Amour, marquis de Bouillé at Montmédy

Montmédy (, german: Mittelberg) is a commune in the Meuse department in Grand Est in north-eastern France.

Citadel of Montmédy

In 1221 the first castle of Montmédy was built on top of a hill by the Count of Chiny. Montmédy soon became th ...

.

After the attempted flight was stopped at Varennes

Varennes-en-Argonne (, literally ''Varennes in Argonne'') or simply Varennes (German: Wöringen) is a commune in the Meuse department in the Grand Est region in Northeastern France. In 2019, it had a population of 639.

Geography

Varennes-en-Ar ...

, Charles moved on to Koblenz

Koblenz (; Moselle Franconian: ''Kowelenz''), spelled Coblenz before 1926, is a German city on the banks of the Rhine and the Moselle, a multi-nation tributary.

Koblenz was established as a Roman military post by Drusus around 8 B.C. Its nam ...

, where he, the recently escaped Count of Provence and the Princes of Condé jointly declared their intention to invade France. The Count of Provence was sending dispatches to various European sovereigns for assistance, while Charles set up a court-in-exile in the Electorate of Trier

The Electorate of Trier (german: Kurfürstentum Trier or ' or Trèves) was an ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire that existed from the end of the 9th to the early 19th century. It was the temporal possession of the prince- ...

. On 25 August, the rulers of the Holy Roman Empire and Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

issued the Declaration of Pillnitz, which called on other European powers to intervene in France.

On New Year's Day 1792, the National Assembly declared all emigrants

Emigration is the act of leaving a resident country or place of residence with the intent to settle elsewhere (to permanently leave a country). Conversely, immigration describes the movement of people into one country from another (to permanentl ...

traitors, repudiated their titles and confiscated their lands. This measure was followed by the suspension and eventually the abolition of the monarchy in September 1792. The royal family was imprisoned, and the former king and former queen were eventually executed in 1793. The young former dauphin died of illnesses and neglect in 1795.

When the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Pruss ...

broke out in 1792, Charles escaped to Great Britain, where King George III of Great Britain

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

gave him a generous allowance. Charles lived in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

and London with his mistress Louise de Polastron

Marie Louise d’Esparbès de Lussan, by marriage vicomtesse then comtesse de Polastron ( Bardigues, 19 October 1764 – London, 27 March 1804) was a French lady-in-waiting, known as the mistress of the comte d’Artois, who later reigned as Char ...

. His older brother, dubbed Louis XVIII after the death of his nephew in June 1795, relocated to Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

and then to Jelgava Palace

Jelgava Palace ( lv, Jelgavas pils) or historically Mitau Palace ( lv, Mītavas pils, german: Schloss Mitau) is the largest Baroque-style palace in the Baltic states. It was built in the 18th century based on the design of Bartolomeo Rastrelli as ...

, Mitau

Jelgava (; german: Mitau, ; see also other names) is a state city in central Latvia about southwest of Riga with 55,972 inhabitants (2019). It is the largest town in the region of Zemgale (Semigalia). Jelgava was the capital of the united D ...

, where Charles' son Louis Antoine married Louis XVI's only surviving child, Marie Thérèse, on 10 June 1799. In 1802, Charles supported his brother with several thousand pounds. In 1807, Louis XVIII moved to the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

.

Bourbon Restoration

In January 1814, Charles covertly left his home in London to join the

In January 1814, Charles covertly left his home in London to join the Coalition forces

' ps, کمک او همکاري '

, allies = Afghanistan

, opponents = Taliban Al-Qaeda

, commander1 =

, commander1_label = Commander

, commander2 =

, commander2_label =

, commander3 =

, command ...

in southern France. Louis XVIII, by then reliant on a wheelchair, supplied Charles with letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, tit ...

creating him Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

General of the Kingdom of France. On 31 March, the Allies captured Paris. A week later, Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

abdicated. The Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

declared the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, with Louis XVIII as King of France. Charles (now heir-presumptive) arrived in the capital on 12 April and acted as Lieutenant General of the realm until Louis XVIII arrived from the United Kingdom. During his brief tenure as regent, Charles created an ultra-royalist

The Ultra-royalists (french: ultraroyalistes, collectively Ultras) were a French political faction from 1815 to 1830 under the Bourbon Restoration. An Ultra was usually a member of the nobility of high society who strongly supported Roman Cathol ...

secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic ...

that reported directly back to him without Louis XVIII's knowledge. It operated for over five years.

Louis XVIII was greeted with great rejoicing from the Parisians and proceeded to occupy the Tuileries Palace

The Tuileries Palace (french: Palais des Tuileries, ) was a royal and imperial palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the River Seine, directly in front of the Louvre. It was the usual Parisian residence of most French monarchs, f ...

.Nagel, pp. 253–254. The Count of Artois lived in the ''Pavillon de Mars'', and the Duke of Angoulême in the ''Pavillon de Flore

The Pavillon de Flore, part of the Palais du Louvre in Paris, France, stands at the southwest end of the Louvre, near the Pont Royal. It was originally constructed in 1607–1610, during the reign of Henry IV, as the corner pavilion betw ...

'', which overlooked the River Seine

)

, mouth_location = Le Havre/ Honfleur

, mouth_coordinates =

, mouth_elevation =

, progression =

, river_system = Seine basin

, basin_size =

, tributaries_left = Yonne, Loing, Eure, Risle

, tributa ...

. The Duchess of Angoulême fainted upon arriving at the palace, as it brought back terrible memories of her family's incarceration there, and of the storming of the palace and the massacre of the Swiss Guards on 10 August 1792.

Following the advice of the occupying allied army, Louis XVIII promulgated a liberal constitution, the Charter of 1814, which provided for a bicameral

Bicameralism is a type of legislature, one divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single gr ...

legislature, an electorate of 90,000 men and freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the freedo ...

.

After the Hundred Days

The Hundred Days (french: les Cent-Jours ), also known as the War of the Seventh Coalition, marked the period between Napoleon's return from eleven months of exile on the island of Elba to Paris on20 March 1815 and the second restoratio ...

, Napoleon's brief return to power in 1815, the White Terror focused mainly on the purging of a civilian administration which had almost completely turned against the Bourbon monarchy. About 70,000 officials were dismissed from their positions. The remnants of the Napoleonic army were disbanded after the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armies of the Sevent ...

and its senior officers cashiered. Marshal Ney was executed for treason, and Marshal Brune was murdered by a crowd. Approximately 6,000 individuals who had rallied to Napoleon were brought to trial. There were about 300 mob lynchings in the south of France, notably in Marseilles where a number of Napoleon's Mamluks

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

preparing to return to Egypt, were massacred in their barracks.

King's brother and heir presumptive

While the king retained the liberal charter, Charles patronised members of the ultra-royalists in parliament, such asJules de Polignac

Jules Auguste Armand Marie de Polignac, Count of Polignac (; 14 May 178030 March 1847), then Prince of Polignac, and briefly 3rd Duke of Polignac in 1847, was a French statesman and ultra-royalist politician after the Revolution. He served as pr ...

, the writer François-René de Chateaubriand and Jean-Baptiste de Villèle

Jean-Baptiste is a male French name, originating with Saint John the Baptist, and sometimes shortened to Baptiste. The name may refer to any of the following:

Persons

* Charles XIV John of Sweden, born Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte, was King ...

. On several occasions, Charles voiced his disapproval of his brother's liberal ministers and threatened to leave the country unless Louis XVIII dismissed them. Louis, in turn, feared that his brother's and heir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of an heir apparent or a new heir presumptive with a better claim to the position in question. ...

's ultra-royalist

The Ultra-royalists (french: ultraroyalistes, collectively Ultras) were a French political faction from 1815 to 1830 under the Bourbon Restoration. An Ultra was usually a member of the nobility of high society who strongly supported Roman Cathol ...

tendencies would send the family into exile once more (which they eventually did).

On 14 February 1820, Charles's younger son, the Duke of Berry

Duke of Berry (french: Duc de Berry) or Duchess of Berry (french: Duchesse de Berry) was a title in the Peerage of France. The Duchy of Berry, centred on Bourges, was originally created as an appanage for junior members of the French royal fa ...

, was assassinated at the Paris Opera

The Paris Opera (, ) is the primary opera and ballet company of France. It was founded in 1669 by Louis XIV as the , and shortly thereafter was placed under the leadership of Jean-Baptiste Lully and officially renamed the , but continued to be ...

. This loss not only plunged the family into grief but also put the succession in jeopardy, as Charles's elder son, the Duke of Angoulême

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are r ...

, was childless. The lack of male heirs in the Bourbon main line raised the prospect of the throne passing to the Duke of Orléans

Duke of Orléans (french: Duc d'Orléans) was a French royal title usually granted by the King of France to one of his close relatives (usually a younger brother or son), or otherwise inherited through the male line. First created in 1344 by King ...

and his heirs, which horrified the more conservative ultras. Parliament debated the abolition of the Salic law

The Salic law ( or ; la, Lex salica), also called the was the ancient Frankish civil law code compiled around AD 500 by the first Frankish King, Clovis. The written text is in Latin and contains some of the earliest known instances of Old D ...

, which excluded females from the succession and was long held inviolable. However, the Duke of Berry's widow, Caroline of Naples and Sicily, was found to be pregnant and on 29 September 1820 gave birth to a son, Henry, Duke of Bordeaux. His birth was hailed as "God-given", and the people of France purchased for him the Château de Chambord in celebration of his birth. As a result, his granduncle, Louis XVIII, added the title Count of Chambord, hence Henri, Count of Chambord, the name by which he is usually known.

Reign

Ascension and Coronation

Charles' brother King Louis XVIII's health had been worsening since the beginning of 1824. Having both dry and wet gangrene in his legs and spine, he died on 16 September of that year, aged almost 69. Charles, by now aged 66, succeeded him to the throne as King Charles X. On 29 May 1825, King Charles was anointed at the cathedral ofReims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded b ...

, the traditional site of consecration of French kings; it had been unused since 1775, as Louis XVIII had forgone the ceremony to avoid controversy and because his health was too precarious.Price, pp. 119–121. It was in the venerable cathedral of Notre-Dame at Paris that Napoleon had consecrated his revolutionary empire; but in ascending the throne of his ancestors, Charles reverted to the old place of coronation used by the kings of France from the early ages of the monarchy.

Like the regime of the Restoration itself, the coronation was conceived as a compromise between the monarchical tradition and the charter of 1814: it took up the main phases of traditional ceremonial such as the seven anointings or the oaths on the Gospels, all by associating with it the oath of fidelity taken by the King to the Charter of 1814 or the participation of the great princes in the ceremonial as assistants of the Archbishop of Reims .

A commission was charged with simplifying and modernizing the ceremony and making it compatible with the principles of the monarchy according to the Charter (deletion of the promises of struggle against heretics and infidels, of the twelve peers, of references to Hebrew royalty, etc.) - it lasted three and a half hours.

In fact, the choice of the coronation was applauded by the royalists in favor of a constitutional and parliamentary monarchy and not only by those nostalgic for the Ancien Régime; the fact that the ceremony was modernized and adapted to new times encouraged Chateaubriand, a non-absolutist royalist and enthusiastic supporter of the Charter of 1814, to invite the king to be crowned. In the brochure ''The King is Dead! Long live the king!'' Chateaubriand explains that a coronation would have being the "link in the chain which united the oath of the new monarchy to the oath of the old monarchy"; it is continuity with the Ancien Régime more than its return that the royalists extol, Charles X having inherited the qualities of his ancestors: "pious like Saint Louis, affable, compassionate and vigilant like Louis XII, courteous like Francis I Francis I or Francis the First may refer to:

* Francesco I Gonzaga (1366–1407)

* Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414–1450), reigned 1442–1450

* Francis I of France (1494–1547), King of France, reigned 1515–1547

* Francis I, Duke of Saxe-Lau ...

, frank as Henry IV".

The coronation showed that dynastic continuity went hand in hand with political continuity; for Chateaubriand: "The current constitution is only the rejuvenated text of the code of our old franchises" .

This coronation took several days: the May 28, vespers ceremony; May 29, ceremony of the coronation itself, chaired by the Archbishop of Reims, Mgr. Jean-Baptiste de Latil, in the presence in particular of Chateaubriand, Lamartine

Alphonse Marie Louis de Prat de Lamartine (; 21 October 179028 February 1869), was a French author, poet, and statesman who was instrumental in the foundation of the Second Republic and the continuation of the Tricolore as the flag of France. ...

, Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

, and a large audience; May 30, award ceremony for the Knights of the Order of the Holy Spirit

, status = Abolished in 1830 after the July RevolutionRecognised as a dynastic order of chivalry by the ICOC

, founder = Henry III of France

, head_title = Grand Master

, head = Disputed:Louis Alphonse, Duke of Anjou Jean, Count of Pari ...

and finally, May 31, the Royal touch of scrofula. The coronation of Charles X therefore appeared to be a compromise between the tradition of the Ancien Régime and the political changes that had taken place since the Revolution. The coronation nevertheless had a limited influence on the population, mentalities no longer being those of yesteryear. From then on, the coronation caused incomprehension in certain sectors of public opinion.

It was

The coronation of Charles X therefore appeared to be a compromise between the tradition of the Ancien Régime and the political changes that had taken place since the Revolution. The coronation nevertheless had a limited influence on the population, mentalities no longer being those of yesteryear. From then on, the coronation caused incomprehension in certain sectors of public opinion.

It was Luigi Cherubini

Luigi Cherubini ( ; ; 8 or 14 SeptemberWillis, in Sadie (Ed.), p. 833 1760 – 15 March 1842) was an Italian Classical and Romantic composer. His most significant compositions are operas and sacred music. Beethoven regarded Cherubini as the gre ...

who composed the music for the Coronation Mass

A Coronation Mass is a Eucharistic celebration, in which a special liturgical act, the coronation of an image of Mary, is performed.

The coronation of an image of Mary is an act of devotion to her. It expresses the belief that Mary as mother ...

. For the occasion, the composer Gioachino Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer who gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano pieces, and some sacred music. He set new standards ...

composed the Opera '' Il Viaggio a Reims.''

Domestic policies

Like Napoleon and then Louis XVIII before him, Charles X resided mainly at the

Like Napoleon and then Louis XVIII before him, Charles X resided mainly at the Tuileries Palace

The Tuileries Palace (french: Palais des Tuileries, ) was a royal and imperial palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the River Seine, directly in front of the Louvre. It was the usual Parisian residence of most French monarchs, f ...

and, in summer, at the Château de Saint-Cloud, two monuments that no longer exist today. Occasionally he stayed at the Château de Compiègne and the Château de Fontainebleau

Palace of Fontainebleau (; ) or Château de Fontainebleau, located southeast of the center of Paris, in the commune of Fontainebleau, is one of the largest French royal châteaux. The medieval castle and subsequent palace served as a residence ...

, while the Palace of Versailles, where he was born, remained uninhabited.

The reign of Charles X began with some liberal measures such as the abolition of press censorship, but the king renewed the term of Joseph de Villèlle, president of the council since 1822, and gave the reins of government to the ultraroyalists.

He got closer to the population by the trip he made to the north of France in September 1827, then to the east of France in September 1828. He was accompanied by his eldest son and heir-apparent, the Duke of Angoulême, now Dauphin of France

Dauphin of France (, also ; french: Dauphin de France ), originally Dauphin of Viennois (''Dauphin de Viennois''), was the title given to the heir apparent to the throne of France from 1350 to 1791, and from 1824 to 1830. The word ''dauphin' ...

.

In his first act as king, Charles attempted to bring comity to the House of Bourbon by granting the style of Royal Highness to his cousins of the House of Orléans, a title denied by Louis XVIII because of the former Duke of Orléans' vote for the death of Louis XVI.

Charles gave his prime minister, Villèlle lists of laws to be ratified in each parliament. In April 1825, the government approved legislation originally proposed by Louis XVIII to pay an indemnity

In contract law, an indemnity is a contractual obligation of one Party (law), party (the ''indemnitor'') to Financial compensation, compensate the loss incurred by another party (the ''indemnitee'') due to the relevant acts of the indemnitor or ...

(the ''biens nationaux

The biens nationaux were properties confiscated during the French Revolution from the Catholic Church, the monarchy, émigrés, and suspected counter-revolutionaries for "the good of the nation".

''Biens'' means "goods", both in the sense of ...

'') to nobles whose estates had been confiscated during the Revolution. The law gave approximately 988 million francs worth of government bonds to those who had lost their lands, in exchange for their renunciation of their ownership. In the same month, the Anti-Sacrilege Act The Anti-Sacrilege Act (1825–1830) was a French law against blasphemy and sacrilege passed in April 1825 under King Charles X. The death penalty provision of the law was never applied, but a man named François Bourquin was sentenced to perpet ...

was passed. Charles's government attempted to re-establish male-only primogeniture

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relativ ...

for families paying over 300 francs in tax, but this was voted down in the Chamber of Deputies.Price, pp. 116–118.

That Charles was not a popular ruler in the mostly-liberal minded urban Paris became apparent in April 1827, when chaos ensued during the king's review of the National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

in Paris. In retaliation, the National Guard was disbanded but, as its members were not disarmed, it remained a potential threat. After losing his parliamentary majority in a general election in November 1827, Charles dismissed Prime Minister Villèle on 5 January 1828 and appointed Jean-Baptise de Martignac, a man the king disliked and thought of only as provisional. On 5 August 1829, Charles dismissed Martignac and appointed Jules de Polignac

Jules Auguste Armand Marie de Polignac, Count of Polignac (; 14 May 178030 March 1847), then Prince of Polignac, and briefly 3rd Duke of Polignac in 1847, was a French statesman and ultra-royalist politician after the Revolution. He served as pr ...

, who, however, lost his majority in parliament at the end of August, when the Chateaubriand faction defected. Regardless, Polignac retained power and refused to recall the Chambers until March 1830.Price, pp. 122–128.

Conquest of Algeria

On 31 January 1830, the Polignac government decided to send a military expedition toAlgeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

to end the threat of Algerian pirates to Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

trade, hoping also to increase his government's popularity through a military victory. The pretext for the war was an outrage by the Viceroy of Algeria, who had struck the French consul with the handle of his fly swat in a rage over French failure to pay debts from Napoleon's invasion of Egypt. French troops occupied Algiers on 5 July.Price, pp. 136–138.

July Revolution

The Chambers convened on 2 March 1830, but Charles's opening speech was greeted by negative reactions from many deputies. Some introduced a bill requiring the King's minister to obtain the support of the Chambers, and on 18 March, 221 deputies, a majority of 30, voted in favor. However, the King had already decided to hold

The Chambers convened on 2 March 1830, but Charles's opening speech was greeted by negative reactions from many deputies. Some introduced a bill requiring the King's minister to obtain the support of the Chambers, and on 18 March, 221 deputies, a majority of 30, voted in favor. However, the King had already decided to hold general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

s, and the chamber was suspended on 19 March.

The elections of 23 June did not produce a majority favorable to the government. On 6 July, the king and his ministers decided to suspend the constitution, as provided for in Article 14 of the Charter in case of emergency. On 25 July, at the royal residence in Saint-Cloud, Charles issued four ordinances that censored the press, dissolved the newly elected chamber, altered the electoral system

An electoral system or voting system is a set of rules that determine how elections and referendums are conducted and how their results are determined. Electoral systems are used in politics to elect governments, while non-political elections m ...

, and called for elections under the new system in September.

The Ordinances were intended to quell the popular discontent but had the opposite effect. Journalists gathered in protest at the headquarters of the '' National'' daily, founded in January 1830 by Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers ( , ; 15 April 17973 September 1877) was a French statesman and historian. He was the second elected President of France and first President of the French Third Republic.

Thiers was a key figure in the July Rev ...

, Armand Carrel

Armand Carrel (8 May 1800 – 25 July 1836) was a French journalist and political writer.

Early life

Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Armand Carrel was born at Rouen. His father was a wealthy merchant, and he received a liberal education at the '' Lyc� ...

, and others. On Monday, 26 July, the government newspaper '' Le Moniteur Universel'' published the ordinances, and Thiers published a call to revolt signed by forty-three journalists:

"The legal regime has been interrupted: that of force has begun... Obedience ceases to be a duty!" In the evening, crowds assembled in the gardens of the Palais-Royal

The Palais-Royal () is a former royal palace located in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France. The screened entrance court faces the Place du Palais-Royal, opposite the Louvre. Originally called the Palais-Cardinal, it was built for Cardinal R ...

, shouting "Down with the Bourbons!" and "Long live the Charter!". As the police closed off the gardens, the crowd regrouped in a nearby street where they shattered streetlamps.

The next morning of 27 July, police raided and shut down newspapers including '' Le National''. When the protesters, who had re-entered the Palais-Royal gardens, heard of this, they threw stones at the soldiers, prompting them to shoot. By evening, the city was in chaos and shops were looted. On 28 July, the rioters began to erect barricades in the streets. Marshal Marmont

Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont (20 July 1774 – 22 March 1852) was a French general and nobleman who rose to the rank of Marshal of the Empire and was awarded the title (french: duc de Raguse). In the Peninsular War Marmont succeede ...

, who had been called in the day before to remedy the situation, took the offensive, but some of his men defected to the rioters, and by afternoon he had to retreat to the Tuileries Palace

The Tuileries Palace (french: Palais des Tuileries, ) was a royal and imperial palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the River Seine, directly in front of the Louvre. It was the usual Parisian residence of most French monarchs, f ...

.

The members of the Chamber of Deputies sent a five-man delegation to Marmont, urging him to advise the king to assuage the protesters by revoking the four Ordinances. On Marmont's request, the prime minister applied to the king, but Charles refused all compromise and dismissed his ministers that afternoon, realizing the precariousness of the situation. That evening, the members of the Chamber assembled at Jacques Laffitte's house and elected Louis Philippe d'Orléans to take the throne from King Charles, proclaiming their decision on posters throughout the city. By the end of the day, the authority of Charles' government had evaporated.

A few minutes after midnight on 31 July, warned by General Gresseau that Parisians were planning to attack the Saint-Cloud residence, Charles X decided to seek refuge in Versailles with his family and the court, with the exception of the Duke of Angoulême, who stayed behind with the troops, and the Duchess of Angoulême, who was taking the waters at Vichy

Vichy (, ; ; oc, Vichèi, link=no, ) is a city in the Allier department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of central France, in the historic province of Bourbonnais.

It is a spa and resort town and in World War II was the capital of ...

. Meanwhile, in Paris, Louis Philippe assumed the post of Lieutenant General of the Kingdom. Charles' road to Versailles was filled with disorganized troops and deserters. The Marquis de Vérac, governor of the Palace of Versailles, came to meet the king before the royal cortège entered the town, to tell him that the palace was not safe, as the Versailles national guards wearing the revolutionary tricolor were occupying the ''Place d'Armes''. Charles then set out for the Trianon at five in the morning. Later that day, after the arrival of the Duke of Angoulême from Saint-Cloud with his troops, Charles ordered a departure for Rambouillet

Rambouillet (, , ) is a subprefecture of the Yvelines department in the Île-de-France region of France. It is located beyond the outskirts of Paris, southwest of its centre. In 2018, the commune had a population of 26,933.

Rambouillet lie ...

, where they arrived shortly before midnight. On the morning of 1 August, the Duchess of Angoulême, who had rushed from Vichy after learning of events, arrived at Rambouillet

Rambouillet (, , ) is a subprefecture of the Yvelines department in the Île-de-France region of France. It is located beyond the outskirts of Paris, southwest of its centre. In 2018, the commune had a population of 26,933.

Rambouillet lie ...

.

The following day, 2 August, King Charles X abdicated, bypassing his son the Dauphin in favor of his grandson Henry, Duke of Bordeaux, who was not yet ten years old. At first, the Duke of Angoulême (the Dauphin) refused to countersign the document renouncing his rights to the throne of France. According to the Duchess of Maillé, "there was a strong altercation between the father and the son. We could hear their voices in the next room." Finally, after twenty minutes, the Duke of Angoulême reluctantly countersigned his father's declaration:

Louis Philippe ignored the document and on 9 August had himself proclaimed King of the French by the members of the Chamber.

Second exile and death

When it became apparent that a mob 14,000 strong was preparing to attack, the royal family left Rambouillet and, on 16 August embarked for the United Kingdom on

When it became apparent that a mob 14,000 strong was preparing to attack, the royal family left Rambouillet and, on 16 August embarked for the United Kingdom on packet steamer

Packet boats were medium-sized boats designed for domestic mail, passenger, and freight transportation in European countries and in North American rivers and canals, some of them steam driven. They were used extensively during the 18th and 19th ...

s provided by Louis Philippe. Informed by the British prime minister, the Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an Anglo-Irish soldier and Tory statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures of 19th-century Britain, serving twice as prime minister ...

, that they needed to arrive in Britain as private citizens, all family members adopted pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name ( orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individu ...

s; Charles X styled himself "Count of Ponthieu". The Bourbons were greeted coldly by the British, who upon their arrival mockingly waved the newly adopted tri-colour flags at them.Nagel, pp. 318–325.

Charles X was quickly followed to Britain by his creditors, who had lent him vast sums during his first exile and were yet to be repaid in full. However, the family was able to use money Charles's wife had deposited in London.

The Bourbons were allowed to reside in Lulworth Castle

Lulworth Castle, in East Lulworth, Dorset, England, situated south of the village of Wool, is an early 17th-century hunting lodge erected in the style of a revival fortified castle, one of only five extant Elizabethan or Jacobean buildings of ...

in Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of , ...

, but quickly moved to Holyrood Palace

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly referred to as Holyrood Palace or Holyroodhouse, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinburgh ...

in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, near the Duchess of Berry

Duke of Berry (french: Duc de Berry) or Duchess of Berry (french: Duchesse de Berry) was a title in the Peerage of France. The Duchy of Berry, centred on Bourges, was originally created as an appanage for junior members of the French royal famil ...

at Regent Terrace.A. J. Mackenzie-Stuart, ''A French King at Holyrood'', Edinburgh (1995). .

Charles' relationship with his daughter-in-law proved uneasy, as the Duchess declared herself regent for her son Henry, Duke of Bordeaux, who was now the legitimist pretender to the French throne. Charles at first denied her this role, but in December agreed to support her claimNagel, pp. 327–328. once she had landed in France. In 1831 the Duchess made her way from Britain by way of the Netherlands, Prussia and Austria to her family in Naples.

Having gained little support, she arrived in Marseilles

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

in April 1832, and made her way to the Vendée

Vendée (; br, Vande) is a department in the Pays de la Loire region in Western France, on the Atlantic coast. In 2019, it had a population of 685,442.

, where she tried to instigate an uprising against the new regime. There she was imprisoned, much to the embarrassment of her father-in-law Charles. He was further dismayed when after her release the Duchess married the Count of Lucchesi Palli, a minor Neapolitan noble. In response to this morganatic match, Charles banned her from seeing her children.

At the invitation of Emperor Francis I of Austria, the Bourbons moved to Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

in winter 1832/33 and were given lodging at the Hradschin Palace. In September 1833, Bourbon legitimists gathered in Prague to celebrate the Duke of Bordeaux's thirteenth birthday. They expected grand celebrations, but Charles X merely proclaimed his grandson's majority.Nagel, pp. 340–342.

On the same day, after much cajoling by Chateaubriand, Charles agreed to a meeting with his daughter-in-law, which took place in Leoben on 13 October 1833. The children of the Duchess refused to meet her after they learned of her second marriage. Charles refused the Duchess' demands, but after protests from his other daughter-in-law, the Duchess of Angoulême, he acquiesced. In the summer of 1834, he again allowed the Duchess of Berry to see her children.

Upon the death of the Austrian emperor Francis in March 1835, the Bourbons left Prague Castle, as the new emperor Ferdinand wished to use it for coronation ceremonies. The Bourbons moved initially to Teplitz

Teplice () (until 1948 Teplice-Šanov; german: Teplitz-Schönau or ''Teplitz'') is a city in the Ústí nad Labem Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 49,000 inhabitants. It is the second largest Czech spa town, after Karlovy Vary. The hist ...

. Then, as Ferdinand continued his use of Prague Castle, Kirchberg Castle was purchased for them. Moving there was postponed due to an outbreak of cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium '' Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting an ...

in the locality.Nagel, pp. 349–350.

In the meantime, Charles left for the warmer climate on Austria's Mediterranean coast in October 1835. Upon his arrival at Görz

Gorizia (; sl, Gorica , colloquially 'old Gorizia' to distinguish it from Nova Gorica; fur, label=Standard Friulian, Gurize, fur, label= Southeastern Friulian, Guriza; vec, label= Bisiacco, Gorisia; german: Görz ; obsolete English ''Goritz ...

(Gorizia) in the Kingdom of Illyria

The Kingdom of Illyria was a crown land of the Austrian Empire from 1816 to 1849, the successor state of the Napoleonic Illyrian Provinces, which were reconquered by Austria in the War of the Sixth Coalition. It was established according to th ...

, he caught cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium '' Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting an ...

and died on 6 November 1836. The townspeople draped their windows in black mourning. Charles was interred in the Church of the Annunciation of Our Lady, in the Franciscan

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

Kostanjevica Monastery

Kostanjevica Monastery ( it, Castagnevizza) is a Franciscan monastery in Pristava near Nova Gorica, Slovenia. The locals frequently refer to it simply as Kapela (meaning ''The Chapel'' in Slovene).

The monastery with the Church of the Annuncia ...

(now in Nova Gorica, Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, and ...

), where his remains lie in a crypt with those of his family. He is the only King of France to be buried outside the country.

A movement reportedly began in 2016 advocating for Charles X's remains to be buried along with other French monarchs in the Basilica of St Denis

The Basilica of Saint-Denis (french: Basilique royale de Saint-Denis, links=no, now formally known as the ) is a large former medieval abbey church and present cathedral in the commune of Saint-Denis, a northern suburb of Paris. The building ...

, although Louis Alphonse, current head of the House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spani ...

, stated in 2017 that he wished the remains of his ancestors to lie undisturbed.

Honours

*Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France ( fro, Reaume de France; frm, Royaulme de France; french: link=yes, Royaume de France) is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. ...

:

** Knight of the Order of the Holy Spirit

, status = Abolished in 1830 after the July RevolutionRecognised as a dynastic order of chivalry by the ICOC

, founder = Henry III of France

, head_title = Grand Master

, head = Disputed:Louis Alphonse, Duke of Anjou Jean, Count of Pari ...

, ''1 January 1771''

** Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleo ...

, ''3 July 1816''

** Grand Cross of the Military Order of St. Louis, ''10 July 1816''

** Grand Master and Knight of the Order of St. Michael

, status = Abolished by decree of Louis XVI on 20 June 1790Reestablished by Louis XVIII on 16 November 1816Abolished in 1830 after the July RevolutionRecognised as a dynastic order of chivalry by the ICOC

, founder = Louis XI of France

, hig ...

** Grand Master and Grand Cross of the Order of St. Lazarus

** Décoration de la Fidélité

** Decoration of The Lily

* : Grand Cross of the Order of St. Stephen, ''1825''

* : Knight of the Order of the Elephant

The Order of the Elephant ( da, Elefantordenen) is a Danish order of chivalry and is Denmark's highest-ranked honour. It has origins in the 15th century, but has officially existed since 1693, and since the establishment of constitutional ...

, ''2 October 1824''

* : Grand Cross of the Military William Order, ''13 May 1825''

* Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

: Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle

The Order of the Black Eagle (german: Hoher Orden vom Schwarzen Adler) was the highest order of chivalry in the Kingdom of Prussia. The order was founded on 17 January 1701 by Elector Friedrich III of Brandenburg (who became Friedrich I, King i ...

, ''4 October 1824''

* :

** Knight of the Order of St. Andrew, ''June 1815''

** Knight of the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky, ''June 1815''

* : Knight of the Order of the Rue Crown, ''1827''

* Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

: Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece

The Distinguished Order of the Golden Fleece ( es, Insigne Orden del Toisón de Oro, german: Orden vom Goldenen Vlies) is a Catholic order of chivalry founded in Bruges by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, in 1430, to celebrate his marriag ...

, ''6 October 1761''

* :

** Knight of the Order of St. Januarius

** Grand Cross of the Order of St. Ferdinand and Merit

* : Stranger Knight of the Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. It is the most senior order of knighthood in the British honours system, outranked in precedence only by the Victoria Cross and the Georg ...

, ''9 March 1825''Shaw, Wm. A. (1906) ''The Knights of England'', I, Londonp. 53

/ref>

Ancestry

Marriage and issue

Charles X married Princess Maria Teresa of Savoy, the daughter of Victor Amadeus III, King of Sardinia, and Maria Antonietta of Spain, on 16 November 1773. The couple had four children – two sons and two daughters – but the daughters did not survive childhood. Only the oldest son survived his father. The children were: #Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême

Louis Antoine of France, Duke of Angoulême (6 August 1775 – 3 June 1844) was the elder son of Charles X of France and the last Dauphin of France from 1824 to 1830. He was disputedly King of France and Navarre for less than 20 minutes before ...

(6 August 1775 – 3 June 1844), sometimes called Louis XIX. Married first cousin Marie Thérèse of France

Marie may refer to:

People Name

* Marie (given name)

* Marie (Japanese given name)

* Marie (murder victim), girl who was killed in Florida after being pushed in front of a moving vehicle in 1973

* Marie (died 1759), an enslaved Cree person in Tr ...

, no issue.

# Sophie, Mademoiselle d'Artois (5 August 1776 – 5 December 1783), died in childhood.

# Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry (24 January 1778 – 13 February 1820), married Marie-Caroline de Bourbon-Sicile, had issue.

# Marie Thérèse, Mademoiselle d'Angoulême (6 January 1783 – 22 June 1783), died in childhood.

In fiction and film

The Count of Artois is portrayed by Al Weaver in Sofia Coppola'smotion picture

A film also called a movie, motion picture, moving picture, picture, photoplay or (slang) flick is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, feelings, beauty, or atmosphere ...

''Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne (; ; née Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last queen of France before the French Revolution. She was born an archduchess of Austria, and was the penultimate child a ...

''.

References

Further reading

* Artz, Frederick Binkerd. ''France Under the Bourbon Restoration, 1814–1830'' (1931)online free

* Artz, Frederick B. ''Reaction and Revolution 1814–1832'' (1938), covers Europe

online

* Brown, Bradford C. "France, 1830 Revolution." in by Immanuel Ness, ed., ''The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest (2009): 1–8. * Frederking, Bettina. "'Il ne faut pas être le roi de deux peuples': strategies of national reconciliation in Restoration France." ''French History'' 22.4 (2008): 446–468. in English * Rader, Daniel L. ''The Journalists and the July Revolution in France: The Role of the Political Press in the Overthrow of the Bourbon Restoration, 1827–1830'' (Springer, 2013). * Weiner, Margery. ''The French Exiles, 1789–1815'' (Morrow, 1961). * Wolf, John B. ''France 1814–1919: the Rise of a Liberal Democratic Society'' (1940) pp 1–58.

Historiography

*External links