Charles Sumner on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

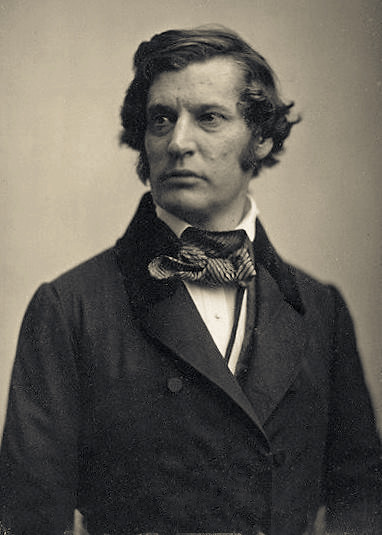

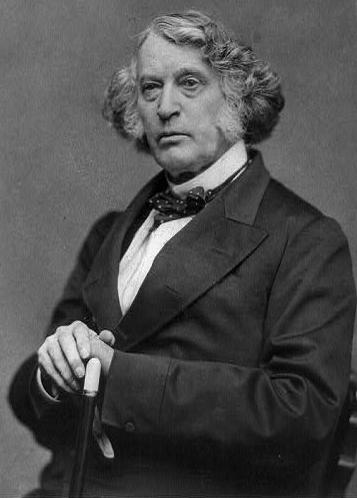

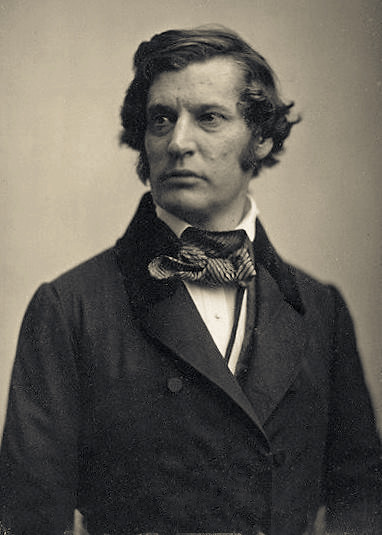

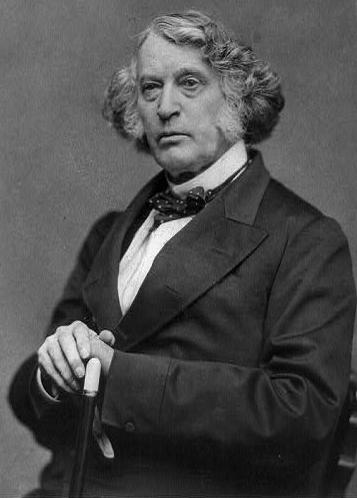

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and

Sumner was born on Irving Street in

Sumner was born on Irving Street in

available online

/ref> and was a second cousin of Edwin Vose Sumner. His father had been born in poverty and his mother, Relief Jacob, shared a similar background and worked as a seamstress prior to her marriage. Sumner's parents were described as exceedingly formal and undemonstrative. His father practiced law and served as Clerk of the

Sumner developed friendships with several prominent Bostonians, particularly

Sumner developed friendships with several prominent Bostonians, particularly  Sumner worked with

Sumner worked with

In 1856, during the "

In 1856, during the "

In addition to the

In addition to the

Although the Radicals desired the immediate emancipation of slaves and persistently lobbied for it as wartime policy, President Lincoln was initially resistant, since the Union slave states

Although the Radicals desired the immediate emancipation of slaves and persistently lobbied for it as wartime policy, President Lincoln was initially resistant, since the Union slave states

Throughout the war, Sumner had been the special champion of blacks, being the most vigorous advocate of emancipation, of enlisting blacks in the Union Army, and of the establishment of the

Throughout the war, Sumner had been the special champion of blacks, being the most vigorous advocate of emancipation, of enlisting blacks in the Union Army, and of the establishment of the

Sumner was well regarded in the United Kingdom, but after the war he sacrificed his reputation in the U.K. by his stand on U.S. claims for British breaches of neutrality. The U.S. had claims against Britain for the damage inflicted by Confederate raiding ships fitted out in British ports. Sumner held that since Britain had accorded the rights of

Sumner was well regarded in the United Kingdom, but after the war he sacrificed his reputation in the U.K. by his stand on U.S. claims for British breaches of neutrality. The U.S. had claims against Britain for the damage inflicted by Confederate raiding ships fitted out in British ports. Sumner held that since Britain had accorded the rights of

Sumner, opposed to American imperialism in the

Sumner, opposed to American imperialism in the

Long ailing, Charles Sumner died of a heart attack at his home in Washington, D.C., on March 11, 1874, aged 63, after serving nearly 23 years in the Senate. He lay in state at the

Long ailing, Charles Sumner died of a heart attack at his home in Washington, D.C., on March 11, 1874, aged 63, after serving nearly 23 years in the Senate. He lay in state at the

Anne-Marie Taylor's biography of Sumner up to 1851 provided a much more sympathetic assessment of a young man, widely respected, conscientious, cultured, courageous, and driven into political prominence by his own sense of duty. Sumner's previously critical biographer David Herbert Donald, in the second volume of his biography, ''Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man'' (1970), was much more favorable to Sumner, and though critical, recognized his large contribution to the positive accomplishments of Reconstruction. It has been noted that events in the Civil Rights Movement between 1960, when Donald's first volume was published, and 1970, when the second volume was published, likely swayed Donald somewhat further towards Sumner.

Lawyer

Anne-Marie Taylor's biography of Sumner up to 1851 provided a much more sympathetic assessment of a young man, widely respected, conscientious, cultured, courageous, and driven into political prominence by his own sense of duty. Sumner's previously critical biographer David Herbert Donald, in the second volume of his biography, ''Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man'' (1970), was much more favorable to Sumner, and though critical, recognized his large contribution to the positive accomplishments of Reconstruction. It has been noted that events in the Civil Rights Movement between 1960, when Donald's first volume was published, and 1970, when the second volume was published, likely swayed Donald somewhat further towards Sumner.

Lawyer

in JSTOR

* Donald, David Herbert, ''Charles Sumner and the Coming of the Civil War'' (1960) **Paul Goodman, "David Donald's Charles Sumner Reconsidered" in ''The New England Quarterly'', Vol. 37, No. 3. (September 1964), pp. 373–387

online at JSTOR

**Gilbert Osofsky, "Cardboard Yankee: How Not to Study the Mind of Charles Sumner", ''Reviews in American History'', Vol. 1, No. 4 (December 1973), pp. 595–60

in JSTOR

* Donald, David Herbert, ''Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man'' (1970) * Foner, Eric, ''Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War'' (1970) * * Foreman, Amanda, ''A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War'' (2011). New York: Penguin Random House. * Frasure, Carl M. "Charles Sumner and the Rights of the Negro", ''The Journal of Negro History'', Vol. 13, No. 2 (April 1928), pp. 126–14

in JSTOR

* Gienapp, William E., "The Crime against Sumner: The Caning of Charles Sumner and the Rise of the Republican Party." ''Civil War History'' 25 (September 1979): 218–45. *Haynes, George Henry, ''Charles Sumner'' (1909

online edition

* Hidalgo, Dennis

"Charles Sumner and the Annexation of the Dominican Republic"

Volume XXI, 2/1997: 51-66 * Hoffer, Williamjames Hull, ''The Caning of Charles Sumner: Honor, Idealism, and the Origins of the Civil War'' (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010) * Jager, Ronald B., "Charles Sumner, the Constitution, and the Civil Rights Act of 1875", ''The New England Quarterly'', Vol. 42, No. 3 (September 1969), pp. 350–37

in JSTOR

* McCullough, David, ''The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris'' (2011) * Nason, Elias, ''The Life and Times of Charles Sumner: His Boyhood, Education and Public Career'' (Boston: B. B. Russell, 1874) * * Pfau, Michael William, "Time, Tropes, And Textuality: Reading Republicanism In Charles Sumner's 'Crime Against Kansas.'" ''Rhetoric & Public Affairs'' 2003 6(3): 385–413. * Pierson, Michael D., "'All Southern Society Is Assailed by the Foulest Charges': Charles Sumner's 'The Crime against Kansas' and the Escalation of Republican Anti-Slavery Rhetoric", ''The New England Quarterly'', Vol. 68, No. 4 (December 1995), pp. 531–55

in JSTOR

* Puleo, Stephen, ''The Caning: The Assault That Drove America to Civil War''. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing LLC, 2012. (ebook) * Ruchames, Louis, "Charles Sumner and American Historiography", ''Journal of Negro History'', Vol. 38, No. 2 (April 1953), pp. 139–16

online at JSTOR

* Sinha, Manisha, "The Caning of Charles Sumner: Slavery, Race, and Ideology in the Age of the Civil War", ''Journal of the Early Republic'' 2003 23(2): 233–262

in JSTOR

* Storey, Moorfield, ''Charles Sumner'' (1900) biograph

online edition

* Taylor, Anne-Marie, ''Young Charles Sumner and the Legacy of the American Enlightenment, 1811–1851'' (U. of Massachusetts Press, 2001. 422 pp.). Disagrees with Donald and contends that Sumner internalized republican principles of duty, education, and liberty balanced by order. He was also shaped by Moral Philosophy, the dominant strain of American Enlightenment thinking, which included cosmopolitan ideals and a stress on the dignity of intellect and conscience. He was also keen on the idea of Natural Law. These influences came from readings and his close ties to

online edition

* Sumner, Charles. ''The Works of Charles Sumner'

online edition

*

Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Charles Sumner

* /en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Crime_against_Kansas Sumner's "Crime Against Kansas" speech* * *

The Liberator Files

Items concerning Charles Sumner from Horace Seldon's collection and summary of research of William Lloyd Garrison's ''The Liberator'' original copies at the Boston Public Library, Boston, Massachusetts. * * , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Sumner, Charles 1811 births 1874 deaths 19th-century American politicians Abolitionists from Boston American people of English descent Boston Latin School alumni Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery Chairmen of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Harvard Law School alumni Liberal Republican Party United States senators Massachusetts Democrats Massachusetts Free Soilers Massachusetts Liberal Republicans Massachusetts Republicans Members of the American Antiquarian Society People from Beacon Hill, Boston People of the Reconstruction Era People of Massachusetts in the American Civil War People with traumatic brain injuries Politicians from Boston Radical Republicans Republican Party United States senators from Massachusetts Sumner family Union (American Civil War) political leaders

United States Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

from Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of the Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recons ...

in the U.S. Senate during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. During Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, he fought to minimize the power of the ex-Confederates and guarantee equal rights to the freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom ...

. He fell into a dispute with President Ulysses Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

, a fellow Republican, over the control of Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

, leading to the stripping of his power in the Senate and his subsequent effort to defeat Grant's re-election.

Sumner changed his political party several times as anti-slavery coalitions rose and fell in the 1830s and 1840s before coalescing in the 1850s as the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

, the affiliation with which he became best known. He devoted his enormous energies to the destruction of what Republicans called the Slave Power, that is, to the ending of the influence over the federal government of Southern slave owners who sought to continue slavery and to expand it into the territories. On May 22, 1856, South Carolina Democratic congressman Preston Brooks beat Sumner nearly to death with a cane on the Senate floor after Sumner delivered an anti-slavery speech, "The Crime Against Kansas." In the speech, Sumner characterized the attacker's first cousin once removed, South Carolina Senator Andrew Butler

Andrew Pickens Butler (November 18, 1796May 25, 1857) was a United States senator from South Carolina who authored the Kansas-Nebraska Act with Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois.

Biography

Butler was a son of William Butler and Behethland ...

, as a "Don Quixote" who had chosen "the harlot, slavery" as his mistress. The widely reported episode left Sumner severely injured and both men famous. It was several years before he could return to the Senate; Massachusetts not only refused to replace him, it even re-elected him, leaving his empty desk in the Senate as a reminder of the incident. The episode contributed significantly to the polarization of the country leading up to the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

, with the event symbolizing the increasingly vitriolic and violent socio-political atmosphere of the time.

During the war, he was a leader of the Radical Republican

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recon ...

faction that criticized President Lincoln for being too moderate on the South. Sumner specialized in foreign affairs and worked closely with Lincoln to ensure that the British and the French refrained from intervening on the side of the Confederacy during the Civil War. As the chief Radical leader in the Senate during Reconstruction, Sumner fought hard to provide equal civil and voting rights for the freedmen on the grounds that "consent of the governed

In political philosophy, the phrase consent of the governed refers to the idea that a government's legitimacy and moral right to use state power is justified and lawful only when consented to by the people or society over which that political pow ...

" was a basic principle of American republicanism, and to block ex-Confederates from power so they would not reverse the gains derived from the Union's victory in the Civil War. Sumner, teaming with House leader Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

, battled Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

's reconstruction plans and sought to impose a Radical Republican program on the South. Although Sumner forcefully advocated the annexation of Alaska in the Senate, he was against the annexation of the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with ...

, then known by the name of its capital, Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

. After leading senators to defeat President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

's Santo Domingo Treaty in 1870, Sumner broke with Grant and denounced him in such terms that reconciliation was impossible. In 1871, President Grant and his Secretary of State Hamilton Fish

Hamilton Fish (August 3, 1808September 7, 1893) was an American politician who served as the 16th Governor of New York from 1849 to 1850, a United States Senator from New York from 1851 to 1857 and the 26th United States Secretary of State fro ...

retaliated; through Grant's supporters in the Senate, Sumner was deposed as head of the Foreign Relations Committee. Sumner had become convinced that Grant was a corrupt despot and that the success of Reconstruction policies called for new national leadership. Sumner bitterly opposed Grant's re-election by supporting the Liberal Republican candidate Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and editor of the '' New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressman from New York ...

in 1872 and lost his power inside the Republican Party. Less than two years later, he died in office. Sumner was controversial in his time; even the 1960 Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Sumner by David Herbert Donald described him as an arrogant egoist. Sumner was known for being an ineffective political leader in contrast to his more pragmatic colleague Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson (born Jeremiah Jones Colbath; February 16, 1812 – November 22, 1875) was an American politician who was the 18th vice president of the United States from 1873 until his death in 1875 and a senator from Massachusetts from 1855 ...

. Ultimately, Sumner has been remembered positively, with biographer Donald noting his extensive contributions to anti-racism during the Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

. Many places are named for him.

Early life, education, and law career

Sumner was born on Irving Street in

Sumner was born on Irving Street in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

on January 6, 1811. He was the son of Charles Pinckney Sumner

Charles Pinckney Sumner (January 20, 1776—April 24, 1839) was an American attorney, Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, and politician who served as Suffolk County Sheriff's Department, Sheriff of Suffolk County, Massachusetts from ...

, a liberal Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

-educated lawyer abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

and early proponent of racially integrated schools, who shocked 19th-century Boston by opposing anti-miscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is the interbreeding of people who are considered to be members of different races. The word, now usually considered pejorative, is derived from a combination of the Latin terms ''miscere'' ("to mix") and ''genus'' ("race") ...

laws,"Charles Sumner." Dictionary of American Biography Base Set. American Council of Learned Societies, 1928–1936. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2009available online

/ref> and was a second cousin of Edwin Vose Sumner. His father had been born in poverty and his mother, Relief Jacob, shared a similar background and worked as a seamstress prior to her marriage. Sumner's parents were described as exceedingly formal and undemonstrative. His father practiced law and served as Clerk of the

Massachusetts House of Representatives

The Massachusetts House of Representatives is the lower house of the Massachusetts General Court, the state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. It is composed of 160 members elected from 14 counties each divided into single-member ...

from 1806 to 1807 and again 1810 to 1811, but his legal practice was only moderately successful, and throughout Sumner's childhood, his family teetered on the edge of the middle class. In 1825 Charles P. Sumner became Sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

of Suffolk County, a position he held until his death in 1838. The family attended Trinity Church, but after 1825, they occupied a pew in King's Chapel

King's Chapel is an American independent Christian unitarian congregation affiliated with the Unitarian Universalist Association that is "unitarian Christian in theology, Anglican in worship, and congregational in governance." It is housed i ...

.

Sumner's father hated slavery and told Sumner that freeing the slaves would "do us no good" unless they were treated equally by society. Sumner was a close associate of William Ellery Channing

William Ellery Channing (April 7, 1780 – October 2, 1842) was the foremost Unitarian preacher in the United States in the early nineteenth century and, along with Andrews Norton (1786–1853), one of Unitarianism's leading theologians. Channi ...

, an influential Unitarian minister in Boston. Channing believed that human beings had an infinite potential to improve themselves. Expanding on this argument, Sumner concluded that environment had "an important, if not controlling influence" in shaping individuals. By creating a society where "knowledge, virtue and religion" took precedence, "the most forlorn shall grow into forms of unimagined strength and beauty." Moral law, he believed, was as important for governments as it was for individuals, and legal institutions that inhibited one's ability to grow—like slavery or segregation—were evil.

The increased income Charles P. Sumner enjoyed after becoming Sheriff enabled him to afford higher education for his children. Charles Sumner attended the Boston Latin School

The Boston Latin School is a public exam school in Boston, Massachusetts. It was established on April 23, 1635, making it both the oldest public school in the British America and the oldest existing school in the United States. Its curriculum f ...

, where he counted Robert Charles Winthrop

Robert Charles Winthrop (May 12, 1809 – November 16, 1894) was an American lawyer and philanthropist, who served as the speaker of the United States House of Representatives. He was a descendant of John Winthrop.

Early life

Robert Charles ...

, James Freeman Clarke

James Freeman Clarke (April 4, 1810 – June 8, 1888) was an American minister, theologian and author.

Biography

Born in Hanover, New Hampshire, on April 4, 1810, James Freeman Clarke was the son of Samuel Clarke and Rebecca Parker Hull, though ...

, Samuel Francis Smith, and Wendell Phillips among his closest friends. He attended Harvard College, where he lived in Hollis Hall

This is a list of dormitories at Harvard College. Only freshmen live in these dormitories, which are located in and around Harvard Yard. Sophomores, juniors and seniors live in the House system.

Apley Court

South of Harvard Yard on Holyoke Stree ...

and was a member of the Porcellian Club. After his 1830 graduation, he attended Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each c ...

where he became a protégé of Joseph Story

Joseph Story (September 18, 1779 – September 10, 1845) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, serving from 1812 to 1845. He is most remembered for his opinions in ''Martin v. Hunter's Lessee'' and '' United States ...

and became an enthusiast in the study of jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning ...

.

After graduating from law school in 1834, Sumner was admitted to the bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar ( ...

and entered private practice in Boston in partnership with George Stillman Hillard

George Stillman Hillard (September 22, 1808 – January 21, 1879) was an American lawyer and author. Besides developing his Boston legal practice (with Charles Sumner as a partner), he served in the Massachusetts legislature, edited several B ...

. A visit to Washington decided him against a political career, and he returned to Boston resolved to practice law. He contributed to the quarterly ''American Jurist'' and edited Story's court decisions as well as some law texts. From 1836 to 1837, Sumner lectured at Harvard Law School.

Travels in Europe

Sumner traveled to Europe in 1837. He landed atLe Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

and found the cathedral

A cathedral is a church that contains the ''cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denominations ...

at Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the region of Normandy and the department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe, the population ...

striking: "the great lion of the north of France … transcending all that my imagination had pictured." He reached Paris in December, began to study French, and visited the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the '' Venus de Milo''. A central ...

"with a throb," describing how his ignorance of art made him feel "cabined cribbed, confined" until repeat visits allowed works by Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, better known as Raphael (; or ; March 28 or April 6, 1483April 6, 1520), was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its clarity of form, ease of composition, and visual ...

and Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested on ...

to change his understanding: "They touched my mind, untutored as it is, like a rich strain of music." He mastered French in six months and attended lectures at the Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

on subjects ranging from geology to Greek history to criminal law. In his journal for January 20, 1838, he noted that one lecturer "had quite a large audience among whom I noticed two or three blacks, or rather mulattos—two-thirds black perhaps—dressed quite ''à la mode'' and having the easy, jaunty air of young men of fashion…." who were "well received" by the other students after the lecture. He continued:

It was there that he decided that the predisposition of Americans to see blacks as inferior was a learned viewpoint. The French had no problem with blacks learning and interacting with others. Therefore, he determined to become an abolitionist upon his return to America.

He joined other Americans who were studying medicine on morning rounds at the city's great hospitals. In the course of three more years, he became fluent in Spanish, German, and Italian, and he met with many of the leading statesmen in Europe. In 1838, Sumner visited Britain, where Lord Brougham

Henry Peter Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux, (; 19 September 1778 – 7 May 1868) was a British statesman who became Lord High Chancellor and played a prominent role in passing the 1832 Reform Act and 1833 Slavery Abolition Act ...

declared that he "had never met with any man of Sumner's age of such extensive legal knowledge and natural legal intellect". He returned to the U.S. in 1840.

In 1840, at the age of 29, Sumner returned to Boston to practice law but devoted more time to lecturing at Harvard Law, editing court reports, and contributing to law journals, especially on historical and biographical themes.

Early political career

Sumner developed friendships with several prominent Bostonians, particularly

Sumner developed friendships with several prominent Bostonians, particularly Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include "Paul Revere's Ride", ''The Song of Hiawatha'', and '' Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely trans ...

, whose house he visited regularly in the 1840s. Longfellow's daughters found his stateliness amusing; he would ceremoniously open doors for the children while saying "''In presequas''" ("after you") in a sonorous tone.

He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society

The American Antiquarian Society (AAS), located in Worcester, Massachusetts, is both a learned society and a national research library of pre-twentieth-century American history and culture. Founded in 1812, it is the oldest historical society i ...

in 1843. He served on the society's board of councilors from 1852 to 1853, and later in life served as the society's secretary of foreign correspondence from 1867 to 1874.

In 1845, he delivered an Independence Day oration on "The True Grandeur of Nations" in Boston. He spoke against the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

and made an impassioned appeal for freedom and peace.

He became a sought-after orator for formal occasions. His lofty themes and stately eloquence made a profound impression. His platform presence was imposing. He stood tall, with a massive frame. His voice was clear and powerful. His gestures were unconventional and individual, but vigorous and impressive. His literary style was florid, with much detail, allusion, and quotation, often from the Bible as well as the Greeks and Romans. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (February 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882) was an American poet and educator. His original works include "Paul Revere's Ride", ''The Song of Hiawatha'', and '' Evangeline''. He was the first American to completely trans ...

wrote that he delivered speeches "like a cannoneer ramming down cartridges", while Sumner himself said that "you might as well look for a joke in the Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation is the final book of the New Testament (and consequently the final book of the Christian Bible). Its title is derived from the first word of the Koine Greek text: , meaning "unveiling" or "revelation". The Book of ...

."

Following the annexation of Texas as a new slave-holding state in 1845, Sumner took an active role in the anti-slavery movement. That same year, Sumner represented the plaintiffs in ''Roberts v. Boston

''Roberts v. Boston'', Case citation, 59 Mass. (5 Cush.) 198 (1850), was a court case seeking to end racial discrimination in Boston public schools. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in favor of Boston, finding no constitutional basi ...

'', a case which challenged the legality of segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

. Arguing before the Massachusetts Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

, Sumner noted that schools for blacks were physically inferior and that segregation bred harmful psychological and sociological effects—arguments that would be made in '' Brown v. Board of Education'' over a century later. Sumner lost the case, but the Massachusetts legislature abolished school segregation in 1855.

Sumner worked with

Sumner worked with Horace Mann

Horace Mann (May 4, 1796August 2, 1859) was an American educational reformer, slavery abolitionist and Whig politician known for his commitment to promoting public education. In 1848, after public service as Secretary of the Massachusetts Sta ...

to improve the system of public education in Massachusetts. He advocated prison reform

Prison reform is the attempt to improve conditions inside prisons, improve the effectiveness of a penal system, or implement alternatives to incarceration. It also focuses on ensuring the reinstatement of those whose lives are impacted by crimes ...

. In opposing the Mexican–American War, he considered it a war of aggression but was primarily concerned that captured territories would expand slavery westward. In 1847, Sumner denounced a Boston Representative's vote for the declaration of war against Mexico with such vigor that he became a leader of the Conscience Whigs

The Whig Party was a political party in the United States during the middle of the 19th century. Alongside the slightly larger Democratic Party, it was one of the two major parties in the United States between the late 1830s and the early 1850 ...

faction of the Massachusetts Whig Party. He declined to accept their nomination for U.S Representative in 1848. Instead, Sumner helped organize the Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery int ...

, which opposed both the Democrats and the Whigs, who had nominated Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

, a slave-owning Southerner, for president. Sumner became chairman of the Massachusetts Free Soil Party's executive committee, a position he used to continue advocating for abolition by attracting anti-slavery Whigs and Democrats into a coalition with the Free Soil movement.

In 1851, Democrats gained control of the Massachusetts state legislature in coalition with the Free Soilers. The Free Soilers named Sumner their choice for U.S. Senator. The Democrats initially opposed him and called for a less radical candidate. The impasse was broken after three months and Sumner was elected by a one-vote majority on April 24, 1851, a victory he credited to Free Soil organizer and colleague Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson (born Jeremiah Jones Colbath; February 16, 1812 – November 22, 1875) was an American politician who was the 18th vice president of the United States from 1873 until his death in 1875 and a senator from Massachusetts from 1855 ...

. His election marked a sharp break in Massachusetts politics, as his abolitionist politics contrasted sharply those of his most well-known predecessor in the seat, Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison ...

, who had been one of the foremost supporters of the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Am ...

and its Fugitive Slave Act

A fugitive (or runaway) is a person who is fleeing from custody, whether it be from jail, a government arrest, government or non-government questioning, vigilante violence, or outraged private individuals. A fugitive from justice, also know ...

.

United States Senate (1851–1874)

Antebellum career

Sumner took his Senate seat in late 1851 as a Free Soil Democrat. For the first few sessions, Sumner did not promote any of his controversial causes. On August 26, 1852, Sumner delivered his first major speech, despite strenuous efforts to dissuade him. This oratorical effort incorporated a popular abolitionist motto: "Freedom National; Slavery Sectional" as its title. In it, Sumner attacked the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. After his speech, a senator fromAlabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

urged that there be no reply: "The ravings of a maniac may sometimes be dangerous, but the barking of a puppy never did any harm." Sumner's outspoken opposition to slavery made him few friends in the Senate.

Though the conventions of both major parties had just affirmed the finality of every provision of the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Am ...

, including the Fugitive Slave Act, Sumner called for the Act's repeal. For more than three hours he denounced it as a violation of the Constitution, an affront to the public conscience, and an offense against divine law.

The "Crime against Kansas" speech and subsequent beating by Brooks

In 1856, during the "

In 1856, during the "Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

" crisis, Sumner denounced the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law ...

, and he continued this attack in his "Crime against Kansas" speech on May 19 and 20. The long speech argued for the immediate admission of Kansas as a free state, and went on to denounce the " Slave Power"—the political arm of the slave owners. Their goal, he alleged, was to spread slavery through the free states that had made it illegal. The motivation of the Slave Power, he said, was to rape a virgin territory:

Not in any common lust for power did this uncommon tragedy have its origin. It is the rape of a virgin Territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of slavery; and it may be clearly traced to a depraved desire for a new Slave State, hideous offspring of such a crime, in the hope of adding to the power of slavery in the National Government.Afterwards, Sumner verbally attacked authors of the Act, Democratic senators Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois and

Andrew Butler

Andrew Pickens Butler (November 18, 1796May 25, 1857) was a United States senator from South Carolina who authored the Kansas-Nebraska Act with Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois.

Biography

Butler was a son of William Butler and Behethland ...

of South Carolina. He said:

The senator from South Carolina has read many books of chivalry, and believes himself a chivalrous knight with sentiments of honor and courage. Of course he has chosen a mistress to whom he has made his vows, and who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight—I mean the harlot, slavery. For her his tongue is always profuse in words. Let her be impeached in character, or any proposition made to shut her out from the extension of her wantonness, and no extravagance of manner or hardihood of assertion is then too great for this senator.According to Hoffer (2010), "It is also important to note the sexual imagery that recurred throughout the oration, which was neither accidental nor without precedent. Abolitionists routinely accused slaveholders of maintaining slavery so that they could engage in forcible sexual relations with their slaves." Sumner also attacked the honor of South Carolina, having alluded in his speech that the history of the state be "blotted out of existence…" Douglas said to a colleague during the speech that "this damn fool Sumner is going to get himself shot by some other damn fool." Representative Preston Brooks, Butler's first cousin once removed,The relationship between Brooks and Butler is often reported inaccurately. "In reality, Brooks's father Whitfield Brooks, and Andrew Butler were first cousins." was infuriated. He later said that he intended to challenge Sumner to a duel, and consulted on dueling etiquette with fellow South Carolina Representative Laurence M. Keitt, also a pro-slavery Democrat. Keitt told him that dueling was for gentlemen of equal social standing, and that Sumner was no better than a drunkard, due to the supposedly coarse language he had used during his speech. Brooks said that he concluded that since Sumner was no gentleman, it would be more appropriate to beat him with his cane. Two days later, on the afternoon of May 22, Brooks confronted Sumner as he sat writing at his desk in the almost empty Senate chamber: "Mr. Sumner, I have read your speech twice over carefully. It is a libel on South Carolina, and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine." As Sumner began to stand up, Brooks beat Sumner severely on the head before he could reach his feet, using a thick

gutta-percha

Gutta-percha is a tree of the genus '' Palaquium'' in the family Sapotaceae. The name also refers to the rigid, naturally biologically inert, resilient, electrically nonconductive, thermoplastic latex derived from the tree, particularly fr ...

cane with a gold head. Sumner was knocked down and trapped under the heavy desk, which was bolted to the floor, but Brooks continued to strike Sumner until Sumner ripped the desk from the floor. By this time, Sumner was blinded by his own blood, and he staggered up the aisle and collapsed, lapsing into unconsciousness. Brooks beat the motionless Sumner until his cane broke, at which point he continued to strike Sumner with the remaining piece. Several other senators attempted to help Sumner, but were blocked by Keitt, who brandished a pistol and shouted, "Let them be!"

The episode revealed the polarization in America, as Sumner became a martyr in the North and Brooks a hero in the South. Northerners were outraged. The ''Cincinnati Gazette'' said, "The South cannot tolerate free speech anywhere, and would stifle it in Washington with the bludgeon and the bowie-knife, as they are now trying to stifle it in Kansas by massacre, rapine, and murder." William Cullen Bryant

William Cullen Bryant (November 3, 1794 – June 12, 1878) was an American romantic poet, journalist, and long-time editor of the ''New York Evening Post''. Born in Massachusetts, he started his career as a lawyer but showed an interest in poetry ...

of the ''New York Evening Post'', asked, "Has it come to this, that we must speak with bated breath in the presence of our Southern masters?… Are we to be chastised as they chastise their slaves? Are we too, slaves, slaves for life, a target for their brutal blows, when we do not comport ourselves to please them?"

The outrage in the North was loud and strong. Thousands attended rallies in support of Sumner in Boston, Albany, Cleveland, Detroit, New Haven, New York, and Providence. More than a million copies of Sumner's speech were distributed. Two weeks after the caning, Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a cham ...

described the divide the incident represented: "I do not see how a barbarous community and a civilized community can constitute one state. I think we must get rid of slavery, or we must get rid of freedom." Conversely, Brooks was praised by Southern newspapers. The ''Richmond Enquirer'' editorialized that Sumner should be caned "every morning," praising the attack as "good in conception, better in execution, and best of all in consequences" and denounced "these vulgar abolitionists in the Senate" who "have been suffered to run too long without collars. They must be lashed into submission." Southerners sent Brooks hundreds of new canes in endorsement of his assault. One was inscribed "Hit him again." Southern lawmakers made rings out of the cane's remains, which they wore on neck chains to show their solidarity with Brooks. Brooks was remembered in Brooksville, Florida

Brooksville is a city in western Florida and the county seat of Hernando County, Florida, United States. As of the 2010 census it had a population of 7,719, up from 7,264 at the 2000 census. Brooksville is home to historic buildings and residence ...

, Brooksville, Virginia

Big Bend (shown as Bigbend on federal maps) is an unincorporated community in Calhoun County, West Virginia, United States. It lies along West Virginia Route 5 northwest of the town of Grantsville, the county seat of Calhoun County, along ...

, and Brooks County, Georgia

Brooks County is a county located in the U.S. state of Georgia, on its southern border with Florida. As of the 2020 census, the population was 16,301. The county seat is Quitman. The county was created in 1858 from portions of Lowndes and ...

.

Historian William Gienapp has concluded that Brooks' "assault was of critical importance in transforming the struggling Republican party into a major political force."

Theological and legal scholar William R. Long characterized the speech as "a most rebarbative and vituperative speech on the Senate floor," which "flows with Latin quotations and references to English and Roman history." In his eyes, the speech was "a gauntlet thrown down, a challenge to the 'Slave Power' to admit once and for all that it were encircling the free states with their tentacular grip and gradually siphoning off the breath of democracy-loving citizens."

Absence from the Senate

In addition to the

In addition to the head trauma

A head injury is any injury that results in trauma to the skull or brain. The terms ''traumatic brain injury'' and ''head injury'' are often used interchangeably in the medical literature. Because head injuries cover such a broad scope of inju ...

, Sumner suffered from nightmares, severe headaches, and what is now understood to be post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental and behavioral disorder that can develop because of exposure to a traumatic event, such as sexual assault, warfare, traffic collisions, child abuse, domestic violence, or other threats o ...

or "psychic wounds." When he spent months convalescing, his political enemies ridiculed him and accused him of cowardice for not resuming his duties. The Massachusetts General Court re-elected him in November 1856, believing that his vacant chair in the Senate chamber served as a powerful symbol of free speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recog ...

and resistance to slavery.

When Sumner returned to the Senate in 1857, he was unable to last a day. His doctors advised a sea voyage and "a complete separation from the cares and responsibilities that must beset him at home." He sailed for Europe and immediately found relief. During two months in Paris in the spring of 1857, he renewed friendships, especially with Thomas Gold Appleton, dined out frequently, and attended the opera several nights in a row. His contacts there included Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis Charles Henri Clérel, comte de Tocqueville (; 29 July 180516 April 1859), colloquially known as Tocqueville (), was a French aristocrat, diplomat, political scientist, political philosopher and historian. He is best known for his wo ...

, poet Alphonse de Lamartine

Alphonse Marie Louis de Prat de Lamartine (; 21 October 179028 February 1869), was a French author, poet, and statesman who was instrumental in the foundation of the Second Republic and the continuation of the Tricolore as the flag of France. ...

, former French Prime Minister François Guizot

François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (; 4 October 1787 – 12 September 1874) was a French historian, orator, and statesman. Guizot was a dominant figure in French politics prior to the Revolution of 1848.

A conservative liberal who opposed the ...

, Ivan Turgenev

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev (; rus, links=no, Ива́н Серге́евич Турге́невIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; 9 November 1818 – 3 September 1883 (Old Style dat ...

, and Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and became best known for her novel '' Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (1852), which depicts the har ...

. Sumner then toured several countries, including Prussia and Scotland, before returning to Washington where he spent only a few days in the Senate in December. Both then and during several later attempts to return to work, he found himself exhausted just listening to Senate business. He sailed once more for Europe on May 22, 1858, the second anniversary of Brooks' attack.

In Paris, prominent physician Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard

Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard FRS (8 April 1817 – 2 April 1894) was a Mauritian physiologist and neurologist who, in 1850, became the first to describe what is now called Brown-Séquard syndrome.

Early life

Brown-Séquard was born at Port ...

diagnosed Sumner's condition as spinal cord damage that he could treat by burning the skin along the spinal cord. Sumner chose to refuse anesthesia, which was thought to reduce the effectiveness of the procedure. Observers both at the time and since doubt Brown-Séquard's efforts were of value. After spending weeks recovering from these treatments, Sumner resumed his touring, this time traveling as far east as Dresden and Prague and south to Italy twice. In France he visited Brittany and Normandy, as well as Montpellier. He wrote his brother: "If anyone cares to know how I am doing, you can say better and better."

Return to Senate

Sumner returned to the Senate in 1859. When fellow Republicans advised taking a less strident tone than he had years earlier, he answered: "When crime and criminals are thrust before us, they are to be met by all the energies that God has given us by argument, scorn, sarcasm and denunciation." He delivered his first speech following his return on June 4, 1860, during the 1860 presidential election. In "The Barbarism of Slavery", he attacked attempts to depict slavery as a benevolent institution, said it had stifled economic development in the South and that it left slaveholders reliant on "the bludgeon, the revolver, and the bowie-knife". He addressed an anticipated objection on the part of one of his colleagues: "Say, sir, in your madness, that you own the sun, the stars, the moon; but do not say that you own a man, endowed with a soul that shall live immortal, when sun and moon and stars have passed away." Even allies found his language too strong, one calling it "harsh, vindictive, and slightly brutal". He spent the summer rallying the anti-slavery forces and opposing talk of compromise.Civil War

Following the outbreak of war, Sumner was a member of a faction of theRadical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recons ...

faction. Oates (December 1980), ''The Slaves Freed'', American Heritage Magazine The Radicals primarily advocated the immediate abolition of slavery and the destruction of the Southern planter class. Senate Radicals included Sumner, Zachariah Chandler

Zachariah Chandler (December 10, 1813 – November 1, 1879) was an American businessman, politician, one of the founders of the Republican Party, whose radical wing he dominated as a lifelong abolitionist. He was mayor of Detroit, a four-term sen ...

, and Benjamin Wade

Benjamin Franklin "Bluff" Wade (October 27, 1800March 2, 1878) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States Senator for Ohio from 1851 to 1869. He is known for his leading role among the Radical Republicans.

. Although like-minded on slavery, the Radicals were loosely organized and disagreed on other issues such as the tariff and currency. After the fall of Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battle ...

in April 1861, Sumner, Chandler and Wade repeatedly visited President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

, speaking on slavery and the rebellion.

After the withdrawal of Southern senators, Sumner became chair of the Committee on Foreign Relations in March 1861. As chair, Sumner renewed his efforts for diplomatic recognition

Diplomatic recognition in international law is a unilateral declarative political act of a state that acknowledges an act or status of another state or government in control of a state (may be also a recognized state). Recognition can be accor ...

of Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and s ...

. Haiti had sought recognition since winning independence in 1804 but faced opposition from Southern senators. In their absence, the United States recognized Haiti in 1862.

Slave emancipation

Although the Radicals desired the immediate emancipation of slaves and persistently lobbied for it as wartime policy, President Lincoln was initially resistant, since the Union slave states

Although the Radicals desired the immediate emancipation of slaves and persistently lobbied for it as wartime policy, President Lincoln was initially resistant, since the Union slave states Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent ...

, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

, Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

, and Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

would be encouraged to join the Confederacy. Lincoln instead adopted a plan for gradual emancipation and compensation to slavers,Haynes (1909), Charles Sumner, pp. 247–51 but consulted with Sumner frequently. Despite their disagreements, Lincoln described Sumner as "my idea of a bishop" and consulted him as an embodiment of the conscience of the American people.

In May 1861, Sumner counseled Lincoln to make emancipation the primary objective of the war. He believed that military necessity would eventually force Lincoln's hand and that emancipation would give the Union higher moral standing, which would keep Britain from entering the Civil War on the side of the Confederacy. As an intermediate measure, the Radicals passed two Confiscation Acts in 1861 and 1862 which allowed the Union military to emancipate confiscated slaves who had been impressed into service by the Confederate military. On January 1, 1863, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War, Civil War. The Proclamation c ...

.

In October 1861, at the Massachusetts Republican Convention in Worcester, Sumner openly expressed his belief that the war's sole cause was slavery and the primary objective of the Union government was the end of slavery. Sumner argued that Lincoln could command the Union Army to emancipate slaves under color of martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Martia ...

. In the conservative press, Sumner's speech was denounced as incendiary. Conservative Massachusetts newspapers editorialized that he was mentally ill and a "candidate for the insane asylum," but the Free Soil faction of the Republican Party fully endorsed Sumner's speech. Sumner continued to advance his argument publicly.

Gilbert Osofsky argues that Sumner saw the war as a "death struggle" between "two mutually contradictory civilizations," and his solution was "to 'civilize' and 'Americanize' the South" by conquest, then forcibly mold it into a society defined in Northern terms, as an idealized version of New England.

Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War

In October 1861, the Union suffered a major defeat at theBattle of Ball's Bluff

The Battle of Ball's Bluff was an early battle of the American Civil War fought in Loudoun County, Virginia, on October 21, 1861, in which Union Army forces under Major General George B. McClellan suffered a humiliating defeat.

The operatio ...

. Senator Edward D. Baker

Edward Dickinson Baker (February 24, 1811October 21, 1861) was an American politician, lawyer, and US army officer. In his political career, Baker served in the U.S. House of Representatives from Illinois and later as a U.S. Senator from Orego ...

, a close friend of President Lincoln who served as Colonel, was killed. After the defeat, Radical Senator Zachariah Chandler

Zachariah Chandler (December 10, 1813 – November 1, 1879) was an American businessman, politician, one of the founders of the Republican Party, whose radical wing he dominated as a lifelong abolitionist. He was mayor of Detroit, a four-term sen ...

pressed for formation of the United States Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War

The Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War was a United States congressional committee started on December 9, 1861, and was dismissed in May 1865. The committee investigated the progress of the war against the Confederacy. Meetings were held ...

to investigate the loyalty and conduct of Union officers, particularly Brigadier General Charles P. Stone, who was blamed for the defeat. Williams (December 1958), ''Investigation: 1862'' Upon learning that Stone had ordered two runaway slaves to be denied asylum

Asylum may refer to:

Types of asylum

* Asylum (antiquity), places of refuge in ancient Greece and Rome

* Benevolent Asylum, a 19th-century Australian institution for housing the destitute

* Cities of Refuge, places of refuge in ancient Judea

...

in the Union Army, Sumner castigated him in a Senate speech. Stone wrote Sumner a terse letter and demanded satisfaction. On January 31, 1862, Stone defended himself in front of the committee. On February 8, Stone was imprisoned for 189 days on suspicion of treason before being released without explanation or apology.

''Trent'' Affair

On November 8, 1861, the Union naval ship intercepted the British steamer two Confederate diplomats aboard, James M. Mason andJohn Slidell

John Slidell (1793July 9, 1871) was an American politician, lawyer, and businessman. A native of New York, Slidell moved to Louisiana as a young man and became a Representative and Senator. He was one of two Confederate diplomats captured by the ...

, placed into port custody.Haynes (1909), ''Charles Sumner'', pp. 251–58 The Northern people and press favored the capture, but there was concern that the British would use this as grounds to go to war with the United States. In response to the capture, the British government dispatched 8,000 British troops to the Canadian border and sought to strengthen the British fleet.

Secretary of State William Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

believed Mason and Slidell were contraband of war, but Sumner believed that the men did not qualify as war contraband because they were unarmed. He argued that their release with an apology by the United States government was appropriate. In the Senate, Sumner suppressed open debate in order to save Lincoln's administration from embarrassment. On December 25, 1861, at Lincoln's invitation, Sumner addressed the cabinet. He read letters from prominent British political figures including Richard Cobden, John Bright

John Bright (16 November 1811 – 27 March 1889) was a British Radical and Liberal statesman, one of the greatest orators of his generation and a promoter of free trade policies.

A Quaker, Bright is most famous for battling the Corn La ...

, William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-con ...

, and the Duke of Argyll as evidence of political sentiment in Britain. supported the envoys' return to the British. Lincoln quietly but reluctantly ordered the release of the Confederate captives to British custody and apologized for their capture. After the ''Trent'' affair, Sumner's reputation improved among conservative Northerners.

Objection to Taney memorial

In February 1865, there was considerable debate over the creation of a memorial to the late Chief JusticeRoger Taney

Roger Brooke Taney (; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. Although an opponent of slavery, believing it to be an evil practice, Taney belie ...

. Sumner, a longtime enemy of Taney, opposed the memorial. In a debate with Senator Lyman Trumbull

Lyman Trumbull (October 12, 1813 – June 25, 1896) was a lawyer, judge, and United States Senator from Illinois and the co-author of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Born in Colchester, Connecticut, Trumbull es ...

, Sumner stated:

The work was ultimately commissioned over Sumner's objection. Horatio Stone created a marble bust of Taney, which is displayed in the Old Supreme Court Chamber

The Old Supreme Court Chamber is the room on the ground floor of the North Wing of the United States Capitol. From 1800 to 1806, the room was the lower half of the first United States Senate chamber, and from 1810 to 1860, the courtroom for the ...

.

Reconstruction and Civil rights

Throughout the war, Sumner had been the special champion of blacks, being the most vigorous advocate of emancipation, of enlisting blacks in the Union Army, and of the establishment of the

Throughout the war, Sumner had been the special champion of blacks, being the most vigorous advocate of emancipation, of enlisting blacks in the Union Army, and of the establishment of the Freedmen's Bureau

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, usually referred to as simply the Freedmen's Bureau, was an agency of early Reconstruction, assisting freedmen in the South. It was established on March 3, 1865, and operated briefly as a ...

. As one of the Radical Republican leaders in the post-war Senate, Sumner fought to provide equal civil and voting rights for the freedmen on the grounds that "consent of the governed" was a basic principle of American republicanism and in order to keep ex-Confederates from gaining political offices and undoing the North's victory in the Civil War.

The Reconstruction Era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

of the United States after the American Civil War was in the nineteenth and early twentieth century usually viewed as an era of Southern exploitation and corruption by Northern politicians and harsh federal policies, led by the Radical Republicans. Foner (1983), ''The New View Of Reconstruction'', American Heritage Magazine The plight of the freedmen during Reconstruction was largely ignored by conservative historians who followed the Dunning School. According to historian Eric Foner, during the 1960s, revisionist historians have reinterpreted Reconstruction "in the light of changed attitudes toward the place of blacks within American society." Charles Sumner, a Radical Republican, has emerged as an idealist and a champion for African American civil rights through this turbulent and controversial period of United States History. Sumner joined his fellow Republicans in overriding President Johnson's vetoes and imposed some of their views, though Sumner's most radical ideas were not implemented. Senator Sumner, however, in late 1866 favored impartial suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

for African Americans, desiring to put in a literacy

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in Writing, written form in some specific context of use. In other wo ...

requirement on all southerners in order to vote.Goldstone, p. 18 Had Sumner's literacy clause been enacted, only a small portion of blacks would have been able to vote, which would have been far more than Congress or the white southern governments were prepared to enact at that time. When Congress did open the vote to all loyal adult males in the South the following year, Sumner was strongly supportive.

Sumner's radical theory of Reconstruction proposed that nothing beyond the confines of the Constitution restricted the Congress in determining how to treat the eleven defeated states, but that even that document had to be read in light of the Declaration of Independence, which he saw as an essential part of fundamental law. Not going as far as Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

in seeing the seceded states as "conquered provinces," he nonetheless argued that by declaring secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics l ...

, they had committed '' felo de se'' (''state suicide'') and could now be turned into territories that should be prepared for statehood, under conditions set by the national government. He objected to Lincoln's and later Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

's more lenient Reconstruction policies as ungenerous to the former slaves, inadequate in their guarantees of equal rights, and an encroachment upon the powers of Congress. When Andrew Johnson was impeached, Sumner voted for conviction at his impeachment trial. He was only sorry that he had to vote on each article of impeachment, for as he said, he would have rather voted, "Guilty of all, and infinitely more."

Sumner was a friend of Samuel Gridley Howe

Samuel Gridley Howe (November 10, 1801 – January 9, 1876) was an American physician, abolitionist, and advocate of education for the blind. He organized and was the first director of the Perkins Institution. In 1824 he had gone to Greece to ...

and a guiding force for the American Freedmen's Inquiry Commission The American Freedmen's Inquiry Commission was charged by U.S. Secretary of War Edwin McMasters Stanton in March 1863 with investigating the status of the slaves and former slaves who were freed by the Emancipation Proclamation. Stanton appointed ...

, started in 1863. He was one of the most prominent advocates for suffrage for blacks, along with free homesteads and free public schools. His uncompromising attitude did not endear him to moderates and his arrogance and inflexibility often inhibited his effectiveness as a legislator. He was largely excluded from work on the Thirteenth Amendment, in part because he did not get along with Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull

Lyman Trumbull (October 12, 1813 – June 25, 1896) was a lawyer, judge, and United States Senator from Illinois and the co-author of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Born in Colchester, Connecticut, Trumbull es ...

, who chaired the Senate Judiciary Committee and did much of the work on it. Sumner introduced an alternative amendment that combined the Thirteenth Amendment with elements of the Fourteenth Amendment. It would have abolished slavery and declared that "all people are equal before the law." During Reconstruction, he often attacked civil rights legislation as inadequate and fought for legislation to give land to freed slaves and to mandate education for all, regardless of race, in the South. He viewed segregation and slavery as two sides of the same coin. He introduced a civil rights bill in 1872 to mandate equal accommodation in all public places and required suits brought under the bill to be argued in the federal courts. The bill failed, but Sumner revived it in the next Congress, and on his deathbed begged visitors to see that it did not fail.

Sumner repeatedly tried to remove the word "white" from naturalization laws. He introduced bills to that effect in 1868 and 1869, but neither came to a vote. On July 2, 1870, Sumner moved to amend a pending bill in a way that would strike the word "white" wherever in all Congressional acts pertaining to naturalization

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-citizen of a country may acquire citizenship or nationality of that country. It may be done automatically by a statute, i.e., without any effort on the part of the in ...

of immigrants. On July 4, 1870, he said: "Senators undertake to disturb us … by reminding us of the possibility of large numbers swarming from China; but the answer to all this is very obvious and very simple. If the Chinese come here, they will come for citizenship or merely for labor. If they come for citizenship, then in this desire do they give a pledge of loyalty to our institutions; and where is the peril in such vows? They are peaceful and industrious; how can their citizenship be the occasion of solicitude?" He accused legislators promoting anti-Chinese legislation of betraying the principles of the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

: "Worse than any heathen or pagan abroad are those in our midst who are false to our institutions." Sumner's bill failed, and from 1870 to 1943, and in some cases as late as 1952, Chinese and other Asians were ineligible for naturalized U.S. citizenship.

Sumner remained a champion of civil rights for blacks. He co-authored the Civil Rights Act of 1875

The Civil Rights Act of 1875, sometimes called the Enforcement Act or the Force Act, was a United States federal law enacted during the Reconstruction era in response to civil rights violations against African Americans. The bill was passed by the ...

with John Mercer Langston and introduced the bill in the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

on May 13, 1870. The bill was passed a year after his death by Congress in February 1875 and signed into law by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

on March 1, 1875. It was the last civil rights legislation for 82 years until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957

The Civil Rights Act of 1957 was the first federal civil rights legislation passed by the United States Congress since the Civil Rights Act of 1875. The bill was passed by the 85th United States Congress and signed into law by President Dwi ...

. The Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

ruled it unconstitutional in 1883 when it decided a group of cases known as the Civil Rights Cases.

Alaska annexation