Charles Husband on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Henry Charles Husband (30 October 1908 – 7 October 1983), often known as H. C. Husband, was a leading British

Husband was born in

Husband was born in

Husband worked with Bernard Lovell – the founder of the

Husband worked with Bernard Lovell – the founder of the

Other innovative projects Husband & Co. undertook under Husband's leadership included designing a facility for testing jet engines at altitude in 1946. In the 1950s, Husband assisted the

Other innovative projects Husband & Co. undertook under Husband's leadership included designing a facility for testing jet engines at altitude in 1946. In the 1950s, Husband assisted the

civil

Civil may refer to:

*Civic virtue, or civility

*Civil action, or lawsuit

* Civil affairs

*Civil and political rights

*Civil disobedience

*Civil engineering

*Civil (journalism), a platform for independent journalism

*Civilian, someone not a membe ...

and consulting engineer from Sheffield

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, whose name derives from the River Sheaf which runs through it. The city serves as the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire a ...

, England, who designed bridges and other major civil engineering works. He is particularly known for his work on the Jodrell Bank

Jodrell Bank Observatory () in Cheshire, England, hosts a number of radio telescopes as part of the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics at the University of Manchester. The observatory was established in 1945 by Bernard Lovell, a radio astro ...

radio telescopes; the first of these was the largest fully steerable radio telescope in the world on its completion in 1957. Other projects he was involved in designing include the Goonhilly Satellite Earth Station

Goonhilly Satellite Earth Station is a large radiocommunication site located on Goonhilly Downs near Helston on the Lizard peninsula in Cornwall, England. Owned by Goonhilly Earth Station Ltd under a 999-year lease from BT Group plc, it was a ...

's aerials, one of the earliest telecobalt radiotherapy units, Sri Lanka's tallest building, and the rebuilding of Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson FRS HFRSE FRSA DCL (16 October 1803 – 12 October 1859) was an English civil engineer and designer of locomotives. The only son of George Stephenson, the "Father of Railways", he built on the achievements of his father ...

's Britannia Bridge

Britannia Bridge ( cy, Pont Britannia) is a bridge across the Menai Strait between the island of Anglesey and the mainland of Wales. It was originally designed and built by the noted railway engineer Robert Stephenson as a tubular bridge of w ...

after a fire. He won the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

's Royal Medal and the Wilhelm Exner Medal The Wilhelm Exner Medal has been awarded by the Austrian Industry Association, (ÖGV), for excellence in research and science since 1921.

The medal is dedicated to Wilhelm Exner (1840–1931), former president of the Association, who initialize ...

.

Early life and education

Husband was born in

Husband was born in Sheffield

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, whose name derives from the River Sheaf which runs through it. The city serves as the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire a ...

in 1908 to Ellen Walton Husband, née Harby, and her husband, Joseph (1871–1961), a civil engineer who had founded Sheffield Technical School's civil engineering department and subsequently served as the University of Sheffield

, mottoeng = To discover the causes of things

, established = – University of SheffieldPredecessor institutions:

– Sheffield Medical School – Firth College – Sheffield Technical School – University College of Sheffield

, type = Pu ...

's initial professor in the discipline. Charles Husband attended the city's King Edward VII School and gained an engineering degree at Sheffield University in 1929.

Career

His first job was with Barnsley Water Board. He then worked under the civil engineer Sir Owen Williams in 1931–33, before spending three years on various major English and Scottish residential projects with the First National Housing Trust. In 1936, with Joseph Husband and Antony Clark, he founded the consulting engineering firm of Husband and Clark (later Husband & Co.) in Sheffield. During the Second World War, he first worked in theMinistry of Labour and National Service

Ministry may refer to:

Government

* Ministry (collective executive), the complete body of government ministers under the leadership of a prime minister

* Ministry (government department), a department of a government

Religion

* Christian mi ...

and later on aircraft manufacture for the Ministry of Works. After the war, Husband headed the engineering consultancy, successfully expanding their business, with clients in the immediate post-war years including the British Iron and Steel Research Association

The British Iron and Steel Research Association or BISRA, formed in 1944, was the research arm of the British steel industry. It had headquarters in London, originally at 11 Park Lane, later moved to 24 Buckingham Gate, with Laboratories in Shef ...

, National Coal Board

The National Coal Board (NCB) was the statutory corporation created to run the nationalised coal mining industry in the United Kingdom. Set up under the Coal Industry Nationalisation Act 1946, it took over the United Kingdom's collieries on "ve ...

and the Production Engineering Research Association.

Radio telescopes

Husband worked with Bernard Lovell – the founder of the

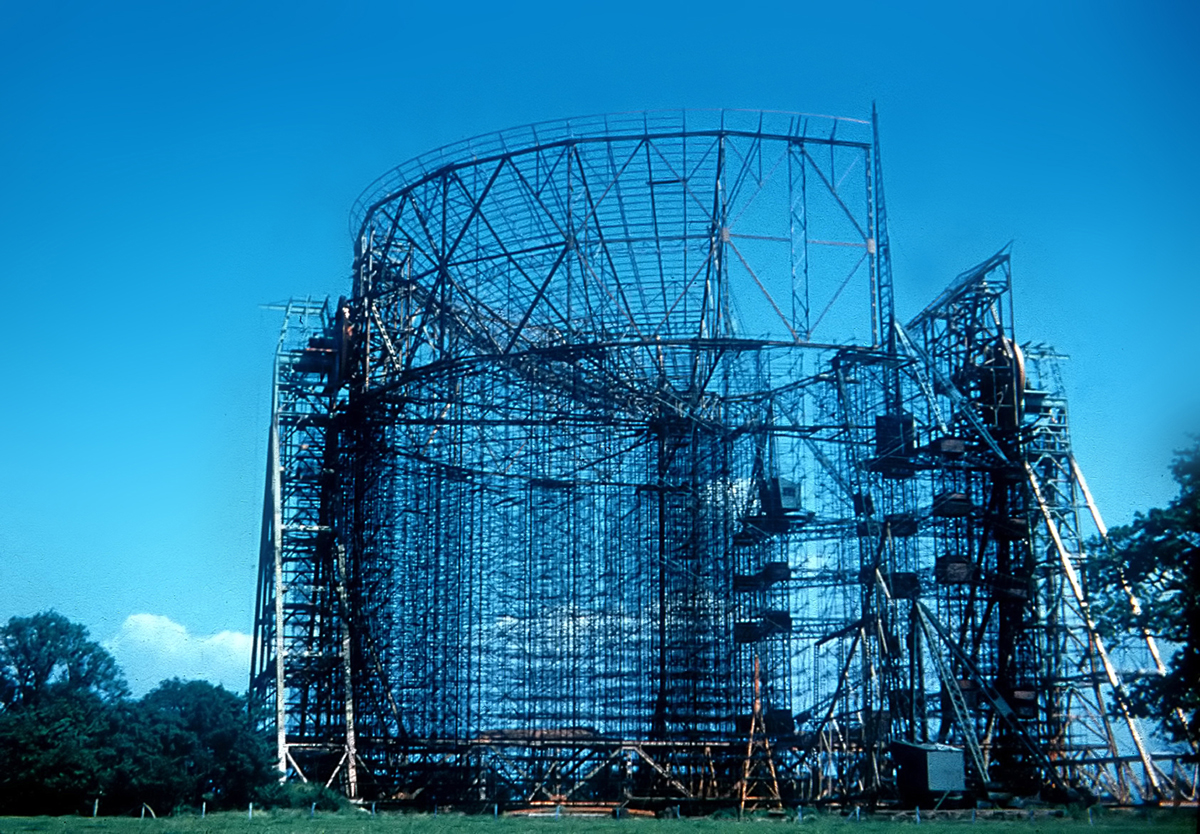

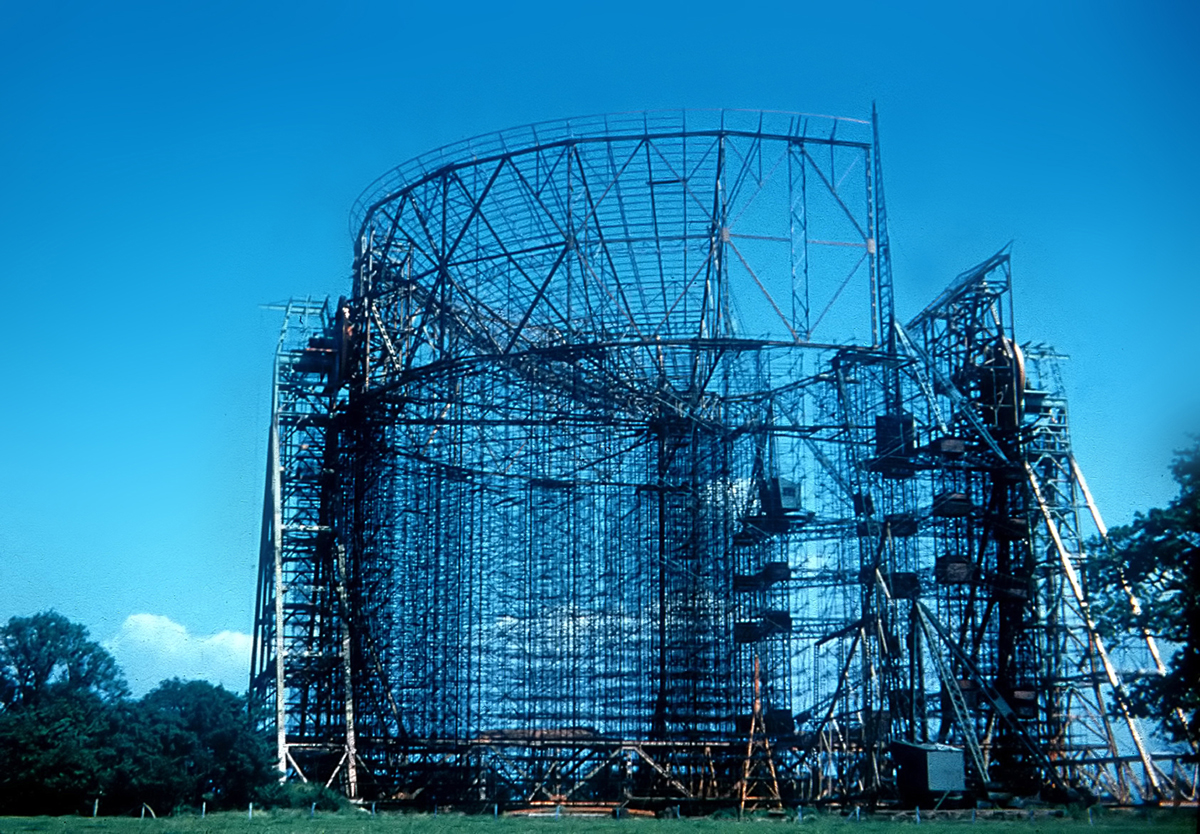

Husband worked with Bernard Lovell – the founder of the Jodrell Bank Observatory

Jodrell Bank Observatory () in Cheshire, England, hosts a number of radio telescopes as part of the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics at the University of Manchester. The observatory was established in 1945 by Bernard Lovell, a radio astro ...

near Holmes Chapel

Holmes Chapel is a large village and civil parish in the unitary authority area of Cheshire East and the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England. Until 1974 the parish was known as Church Hulme. Holmes Chapel is about north of Crewe and south of ...

in Cheshire – on the design and construction of the observatory's first large steerable radio telescope, the "250-ft telescope" (now known as the Lovell Telescope

The Lovell Telescope is a radio telescope at Jodrell Bank Observatory, near Goostrey, Cheshire in the north-west of England. When construction was finished in 1957, the telescope was the largest steerable dish radio telescope in the world at ...

). After attempting to adapt military radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, we ...

equipment to detect cosmic ray

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the Solar System in our own ...

s shortly after the Second World War, Lovell had realised that a much larger aerial would be required, and constructed a 66-metre diameter dish, limited by being static, before proposing the development of an even larger steerable telescope. The idea posed such formidable engineering challenges that the project had been declared "impossible" by other engineers, but Husband is reported to have concluded at their first meeting in September 1949, "It should be easy—about the same problem as throwing a swing bridge over the Thames at Westminster."Lovell 1968, p. 28

He began work on the project early the following year, creating the initial drawings in January 1950 and detailed plans just over a year later. He and Lovell selected a dish diameter of 250 feet (76 metres). Construction began in 1952; despite Husband's optimism the project was beset with delays and escalating costs, caused by multiple changes to Lovell's specifications and the rising price of steel, among other factors.Robertson 1992, p. 139 Wind-tunnel studies with a scale model played an important role in the final design. The telescope was eventually completed in 1957, when it was the largest fully steerable radio telescope in the world. It remains in service as of 2016. According to Lovell, the project was completed using "a desk calculator and slide rule", which led to a "sturdy" construction with "quite a lot of redundancy in the steelwork" which Lovell later credited for the telescope's longevity. The structure is a rare example of a post-war grade-I-listed structure, denoting its "exceptional interest", and was voted Britain's top "unsung landmark" in a 2006 BBC poll.

Husband also helped to design the steerable radio aerials at the GPO's Goonhilly Satellite Earth Station

Goonhilly Satellite Earth Station is a large radiocommunication site located on Goonhilly Downs near Helston on the Lizard peninsula in Cornwall, England. Owned by Goonhilly Earth Station Ltd under a 999-year lease from BT Group plc, it was a ...

in Cornwall, as well as radio telescopes in the UK and elsewhere.

Other projects

Other innovative projects Husband & Co. undertook under Husband's leadership included designing a facility for testing jet engines at altitude in 1946. In the 1950s, Husband assisted the

Other innovative projects Husband & Co. undertook under Husband's leadership included designing a facility for testing jet engines at altitude in 1946. In the 1950s, Husband assisted the radiologist

Radiology ( ) is the medical discipline that uses medical imaging to diagnose diseases and guide their treatment, within the bodies of humans and other animals. It began with radiography (which is why its name has a root referring to radiat ...

Frank Ellis in designing one of the earliest telecobalt radiotherapy units, for radiation treatment

Radiation therapy or radiotherapy, often abbreviated RT, RTx, or XRT, is a therapy using ionizing radiation, generally provided as part of cancer treatment to control or kill malignant cells and normally delivered by a linear accelerator. Radia ...

of cancer, which was installed at the Churchill Hospital in Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

. Like the radio telescopes, the engineering problem involved moving a heavy weight, in this case the lead-shielded source, in three dimensions.

He designed many road and rail bridges. Husband was awarded the contract to rebuild the Britannia Bridge

Britannia Bridge ( cy, Pont Britannia) is a bridge across the Menai Strait between the island of Anglesey and the mainland of Wales. It was originally designed and built by the noted railway engineer Robert Stephenson as a tubular bridge of w ...

over the Menai Strait in Wales, after a 1970 fire. The original was an 1850 rail bridge by Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson FRS HFRSE FRSA DCL (16 October 1803 – 12 October 1859) was an English civil engineer and designer of locomotives. The only son of George Stephenson, the "Father of Railways", he built on the achievements of his father ...

, and Husband faced criticism for designing a double-tier bridge including an additional road deck, which he stated formed part of Stephenson's original concept. The firm also designed the bridge used in the 1957 film, ''The Bridge on the River Kwai

''The Bridge on the River Kwai'' is a 1957 epic war film directed by David Lean and based on the 1952 novel written by Pierre Boulle. Although the film uses the historical setting of the construction of the Burma Railway in 1942–1943, th ...

''.

Outside the UK, Husband & Co. had an office in Colombo

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo m ...

and undertook multiple projects in Sri Lanka. Husband was the architect of the Ceylon Insurance Building in Colombo

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo m ...

, Sri Lanka (later Ceylinco House), a 16-storey building equipped with a helicopter landing pad

A helipad is a landing area or platform for helicopters and powered lift aircraft.

While helicopters and powered lift aircraft are able to operate on a variety of relatively flat surfaces, a fabricated helipad provides a clearly marked hard s ...

on its roof. On completion in 1960, it was the tallest structure in Sri Lanka, at nearly 55 metres.

Awards, honours and societies

Husband was recognised with theCBE

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

in 1964. He won the Royal Medal of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1965 for "his distinguished work in many aspects of engineering, particularly for his design studies of large structures such as those exemplified in the radio telescope at Jodrell Bank and Goonhilly Downs"; he was the medal's first recipient in the applied sciences. He was also awarded the Wilhelm Exner Medal The Wilhelm Exner Medal has been awarded by the Austrian Industry Association, (ÖGV), for excellence in research and science since 1921.

The medal is dedicated to Wilhelm Exner (1840–1931), former president of the Association, who initialize ...

of the Österreichischer Gewerbeverein (1966), the Gold Medal of the Institution of Structural Engineers

The Gold Medal of the Institution of Structural Engineers is awarded by the Institution of Structural Engineers for exceptional and outstanding contributions to the advancement of structural engineering. It was established in 1922.

Recipients

S ...

(1973), and the Benjamin Baker Gold Medal (1959) and James Watt medal (1976) of the Institution of Civil Engineers

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) is an independent professional association for civil engineers and a charitable body in the United Kingdom. Based in London, ICE has over 92,000 members, of whom three-quarters are located in the UK, whi ...

. He received honorary degrees from the universities of Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

(1964) and Sheffield (1967). He was knighted in 1975.

He served as president of the Institution of Structural Engineers

The Institution of Structural Engineers is a professional body for structural engineering based in the United Kingdom.

The Institution has over 30,000 members operating in over 100 countries. The Institution provides professional accreditation ...

(1964–65), chaired the Association of Consulting Engineers (1967) and served on the board of the Council of Engineering Institutions from 1979 until his death. He also chaired Sheffield University's engineering and metallurgy advisory committee (1962–65) and served on Bradford Institute of Technology's civil engineering advisory board (1962–68). In addition to the Institution of Structural Engineers, he was an elected fellow of the American Society of Civil Engineers

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

, Institution of Civil Engineers

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) is an independent professional association for civil engineers and a charitable body in the United Kingdom. Based in London, ICE has over 92,000 members, of whom three-quarters are located in the UK, whi ...

and the Institution of Mechanical Engineers

The Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE) is an independent professional association and learned society headquartered in London, United Kingdom, that represents mechanical engineers and the engineering profession. With over 120,000 member ...

, and was among the founding members of the Fellowship of Engineering.

Personal life

In 1932, Husband married Eileen Margaret Nowill (1906-2000), an architect's daughter who was also from Sheffield. The couple had four children, with the elder of their two sons, Richard Husband, also becoming a civil engineer. He retired in 1982. Husband died in 1983 at Nether Padley, just outside Sheffield inDerbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the nor ...

.

Selected publications

*H. C. Husband, R. W. Husband (1975). Reconstruction of the Britannia Bridge. ''Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers'' 58: 25–49 *Henry Charles Husband (1958). The Jodrell Bank Radio Telescope. ''Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers'' 9: 65–86See also

*Mott MacDonald

The Mott MacDonald Group is a consultancy headquartered in the United Kingdom. It employs 16,000 staff in 150 countries. Mott MacDonald is one of the largest employee-owned companies in the world.

It was established in 1989 by the merger of M ...

, into which Husband & Co. merged in 1990

References

Sources *Daniel Eagan. ''America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry'' (Bloomsbury; 2009) () * Bernard Lovell. ''The Story of Jodrell Bank'' (Oxford University Press; 1968) () *Peter Robertson. ''Beyond Southern Skies: Radio Astronomy and the Parkes Telescope'' (Cambridge University Press; 1992) () {{DEFAULTSORT:Husband, Charles 1908 births 1983 deaths People educated at King Edward VII School, Sheffield English civil engineers Jodrell Bank Observatory Royal Medal winners Presidents of the Institution of Structural Engineers IStructE Gold Medal winners Engineers from Yorkshire