Charles Darwin's education on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Darwin's education gave him a foundation in the doctrine of Creation prevalent throughout the West at the time, as well as knowledge of medicine and theology. More significantly, it led to his interest in natural history, which culminated in his taking part in the second voyage of the ''Beagle'' and the eventual inception of his theory of

A child of the early 19th century, Charles Robert Darwin grew up in a conservative era when repression of revolutionary Radicalism had displaced the 18th century Enlightenment. The

A child of the early 19th century, Charles Robert Darwin grew up in a conservative era when repression of revolutionary Radicalism had displaced the 18th century Enlightenment. The

Charles Robert Darwin was born in

Charles Robert Darwin was born in

As a young child at The Mount, Darwin avidly collected

In October 1825, Darwin went to

In October 1825, Darwin went to

Charles Darwin. A paper contributed to the Transactions of the Shropshire Arch├”ological Society

London: Trubner. p. 18. Darwin wrote "What an extraordinary old man he is, now being past 80, & continuing to lecture", though Dr. Hawley thought Duncan was now failing. Darwin added that "I am going to learn to stuff birds, from a blackamoor... he only charges one guinea, for an hour every day for two months". These lessons in

- Transcribed and edited by John van Wyhe (Darwin Online) A few days later Darwin noted "Erasmus caught a Cuttle fish", wondering if it was "Sepia Loligo", then from his textbooks identified it as '' Loligo sagittata'' (a squid). A few days later, Darwin returned with a basin and caught a globular orange zoophyte, then after storms at the start of March saw the shore "literally covered with Cuttle fish". He touched them so they emitted ink and swam away, and also found a damaged starfish beginning to regrow its arms. Eras completed his external hospital study, and returned to Shrewsbury, Darwin found other zoophytes and, on the shore "between Leith & Portobello", caught more sea mice which "when thrown into the sea rolled themselves up like hedgehogs." On 27 March, Susan Darwin wrote to pass on their father's disapproval of Darwin's "plan of picking & chusing what lectures you like to attend", as "you cannot have enough information to know what may be of use to you". His son's "present indulgent way" would make studies "utterly useless", and he wanted Darwin to complete the course. Darwin wrote home apologetically on 8 April with the news that "Dr. Hope has been giving some very good Lectures on Electricity &c. and I am very glad I stayed for them", requesting money to fund staying on another 9 to 14 days. During his summer holiday Charles read ''

Charles Darwin as a student in Edinburgh

1825-1827.'' Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 55: 97-113, pls. 1-2. Jameson was a Neptunian geologist who taught Werner's view that all rock

Darwin became friends with Coldstream who was "prim, formal, highly religious and most kind-hearted". Coldstream's interest in the skies and identifying sea creatures on the

Darwin became friends with Coldstream who was "prim, formal, highly religious and most kind-hearted". Coldstream's interest in the skies and identifying sea creatures on the  With Coldstream, Darwin walked along the shore looking for animals in tidal pools, and became friends with oyster fishermen from nearby Newhaven who took them along to pick specimens from the catches. He went long walks with Grant and others, frequently with William Ainsworth, one of the Presidents who became a Wernerian geologist. As well as the shores of the Forth, he and Ainsworth took boat trips to

With Coldstream, Darwin walked along the shore looking for animals in tidal pools, and became friends with oyster fishermen from nearby Newhaven who took them along to pick specimens from the catches. He went long walks with Grant and others, frequently with William Ainsworth, one of the Presidents who became a Wernerian geologist. As well as the shores of the Forth, he and Ainsworth took boat trips to

22ŌĆō23

also Routes to the Firth soon became familiar, and after another student presented a paper to the Plinian in the common literary form of describing the sights from a journey, Darwin and William Kay (another president) drafted a parody, to be read taking turns, describing "a complete failure" of an excursion from the university via

129

says sponge ova "swim about" by "the rapid vibration of cili├”". Coldstream assisted Grant, and that winter Darwin joined the search, learning what to look for, and dissection techniques using a portable microscope. On 16 March 1827 he noted in a new notebook that he had "Procured from the black rocks at Leith" a

Coldstream assisted Grant, and that winter Darwin joined the search, learning what to look for, and dissection techniques using a portable microscope. On 16 March 1827 he noted in a new notebook that he had "Procured from the black rocks at Leith" a  The ''Wernerian'' society minutes for 24 March record that Grant read "a Memoir regarding the Anatomy and Mode of Generation of Flustr├” , illustrated by preparations and drawings", also a notice on "the Mode of Generation" of the skate leech. Three days later, on 27 March, the Plinian Society minutes record that Darwin "communicated to the Society" two discoveries, that "the ova of the flustra possess organs of motion", and the small black "ovum" of the ''Pontobdella muricata''. "At the request of the Society he promised to draw up an account of the facts and to lay them it, together with specimens, before the Society next evening." This was Darwin's first public presentation. In the next item, Browne argued that mind and consciousness were simply aspects of brain activity, not "souls" or spiritual entities separate from the body. Following a furious debate, the minute of this item was crossed out.

After recording more finds in April, Darwin copied into his notebook under the heading "20th" his first scientific papers. Newhaven dredge boats had provided the '' Flustra carbasea'' specimens, when "highly magnified" the "ciliae of the ova" were "seen in rapid motion", and "That such ova had organs of motion does not appear to have been hitherto observed either by Lamarck Cuvier Lamouroux or any other author." He wrote "This & the following communication was read both before the Wernerian & Plinian Societies", and wrote up a detailed account of his ''Pontobdella'' findings.Darwin, C. R. dinburgh notebookCUL-DAR118. (Darwin Online

The ''Wernerian'' society minutes for 24 March record that Grant read "a Memoir regarding the Anatomy and Mode of Generation of Flustr├” , illustrated by preparations and drawings", also a notice on "the Mode of Generation" of the skate leech. Three days later, on 27 March, the Plinian Society minutes record that Darwin "communicated to the Society" two discoveries, that "the ova of the flustra possess organs of motion", and the small black "ovum" of the ''Pontobdella muricata''. "At the request of the Society he promised to draw up an account of the facts and to lay them it, together with specimens, before the Society next evening." This was Darwin's first public presentation. In the next item, Browne argued that mind and consciousness were simply aspects of brain activity, not "souls" or spiritual entities separate from the body. Following a furious debate, the minute of this item was crossed out.

After recording more finds in April, Darwin copied into his notebook under the heading "20th" his first scientific papers. Newhaven dredge boats had provided the '' Flustra carbasea'' specimens, when "highly magnified" the "ciliae of the ova" were "seen in rapid motion", and "That such ova had organs of motion does not appear to have been hitherto observed either by Lamarck Cuvier Lamouroux or any other author." He wrote "This & the following communication was read both before the Wernerian & Plinian Societies", and wrote up a detailed account of his ''Pontobdella'' findings.Darwin, C. R. dinburgh notebookCUL-DAR118. (Darwin Online

16ŌĆō18 March 1827

At the Plinian meeting, on 3 April, Darwin presented the Society with "A specimen of the ''Pontobdella muricata'', with its ova & young ones", but there is no record of the papers being presented or kept. Grant in his publication about the leech eggs in the ''Edinburgh Journal of Science'' for July 1827 acknowledged "The merit of having first ascertained them to belong to that animal is due to my zealous young friend Mr Charles Darwin of Shrewsbury", the first time Darwin's name appeared in print. Grant's lengthy memoir read before the Wernerian on 24 March was split between the April and October issues of the ''Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal'', with more detail than Darwin had given: he had seen ova (larvae) of ''Flustra carbasea'' in February, after they swam about they stuck to the glass and began to form a new colony. He noted the similarity of the cilia in "other ova", with reference to his 1826 publication describing sponge ova. Darwin was not given credit for what he felt was his discovery, and in 1871, when he discussed "the paltry feeling" of

His father was unhappy that his younger son would not become a physician and "was very properly vehement against my turning into an idle sporting man, which then seemed my probable destination." He therefore enrolled Charles at

His father was unhappy that his younger son would not become a physician and "was very properly vehement against my turning into an idle sporting man, which then seemed my probable destination." He therefore enrolled Charles at

On 31 October Charles returned to Cambridge for the

On 31 October Charles returned to Cambridge for the

Residence requirements kept Darwin in Cambridge till June. He resumed his beetle collecting, took career advice from Henslow, and read

Residence requirements kept Darwin in Cambridge till June. He resumed his beetle collecting, took career advice from Henslow, and read

He had parted from Sedgwick by 20 August, and travelled via

Darwin Online

Darwin's publications, private papers and bibliography, supplementary works including biographies, obituaries and reviews. Free to use, includes items not in public domain. *; public domain

Darwin Correspondence Project

Text and notes for most of his letters {{Darwin

natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

. Although Darwin changed his field of interest several times in these formative years, many of his later discoveries and beliefs were foreshadowed by the influences he had as a youth.

Background and influences

A child of the early 19th century, Charles Robert Darwin grew up in a conservative era when repression of revolutionary Radicalism had displaced the 18th century Enlightenment. The

A child of the early 19th century, Charles Robert Darwin grew up in a conservative era when repression of revolutionary Radicalism had displaced the 18th century Enlightenment. The Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

dominated the English scientific establishment. The Church saw natural history as revealing God's underlying plan and as supporting the existing social hierarchy. It rejected Enlightenment philosophers such as David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) ŌĆō 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" '' Encyclop├”dia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment ph ...

who had argued for naturalism and against belief in God.

The discovery of fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s of extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

species was explained by theories such as catastrophism

In geology, catastrophism theorises that the Earth has largely been shaped by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope.

This contrasts with uniformitarianism (sometimes called gradualism), according to which slow incremen ...

. Catastrophism claimed that animals and plants were periodically annihilated as a result of natural catastrophes and then replaced by new species created ''ex nihilo'' (out of nothing). The extinct organisms could then be observed in the fossil record, and their replacements were considered to be immutable.

Darwin's extended family of Darwins and Wedgwoods was strongly Unitarian. One of DarwinŌĆÖs grandfathers, Erasmus Darwin

Erasmus Robert Darwin (12 December 173118 April 1802) was an English physician. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor, and poet.

His poems ...

, was a successful physician, and was followed in this by his sons Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 ŌĆō 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

, who died in 1778 while still a promising medical student at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dh├╣n ├łideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 1 ...

, and Doctor Robert Waring Darwin

Robert Waring Darwin (30 May 1766 ŌĆō 13 November 1848) was an English medical doctor, who today is best known as the father of the naturalist Charles Darwin. He was a member of the influential DarwinŌĆōWedgwood family.

Biography

Darwin was bor ...

, Darwin's father, who named his son Charles Robert Darwin, honouring his deceased brother.

Erasmus was a freethinker who hypothesized that all warm-blooded animals sprang from a single living "filament" long, long ago. He further proposed evolution by acquired characteristics, anticipating the theory later developed by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 ŌĆō 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biolo ...

. Although Charles was born after his grandfather Erasmus died, his father Robert found the texts an invaluable medical guide and Charles read them as a student. Doctor Robert also followed Erasmus in being a freethinker, but as a wealthy society physician was more discreet and attended the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

patronised by his clients.

Childhood

Charles Robert Darwin was born in

Charles Robert Darwin was born in Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

, Shropshire, England on 12 February 1809 at his family home, the Mount, He was the fifth of six children of wealthy society doctor and financier Robert Waring Darwin

Robert Waring Darwin (30 May 1766 ŌĆō 13 November 1848) was an English medical doctor, who today is best known as the father of the naturalist Charles Darwin. He was a member of the influential DarwinŌĆōWedgwood family.

Biography

Darwin was bor ...

, and Susannah Darwin (''n├®e'' Wedgwood). Both families were largely Unitarian, though the Wedgwoods were adopting Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

. Robert Waring Darwin, himself quietly a freethinker, had baby Charles baptised

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, ╬▓╬¼ŽĆŽä╬╣Žā╬╝╬▒, v├Īptisma) is a form of ritual purificationŌĆöa characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

on 15 November 1809 in the Anglican St Chad's Church, Shrewsbury, but Charles and his siblings attended the Unitarian chapel with their mother.As a young child at The Mount, Darwin avidly collected

animal shell

An exoskeleton (from Greek ''├®x┼Ź'' "outer" and ''skelet├│s'' "skeleton") is an external skeleton that supports and protects an animal's body, in contrast to an internal skeleton ( endoskeleton) in for example, a human. In usage, some of the ...

s, postal franks, bird's eggs, pebbles and minerals. He was very fond of gardening, an interest his father shared and encouraged, and would follow the family gardener around. Early in 1817, soon after becoming eight years old, he started at the small local school run by a Unitarian minister, the Reverend George Case. At home, Charles learned to ride ponies, shoot and fish. Influenced by his father's fashionable interest in natural history, he tried to make out the names of plants, and was given by his father two elementary natural history books. Childhood games included inventing and writing out complex secret codes. Charles would tell elaborate stories to his family and friends "for the pure pleasure of attracting attention & surprise", including hoaxes such as pretending to find apples he'd hidden earlier, and what he later called the "monstrous fable" which persuaded his schoolfriend that the colour of primula

''Primula'' () is a genus of herbaceous flowering plants in the family Primulaceae. They include the primrose ('' P. vulgaris''), a familiar wildflower of banks and verges. Other common species are '' P. auricula'' (auricula), '' P. veris'' (cow ...

flowers could be changed by dosing them with special water. However, his father benignly ignored these passing games, and Charles later recounted that he stopped them because no-one paid any attention.

In July 1817 his mother died after the sudden onset of violent stomach pains and amidst the grief his older sisters had to take charge, with their father continuing to dominate the household whenever he returned from his doctor's rounds. To the -year-old Charles this situation was not a great change, as his mother had frequently been ill and her available time taken up by social duties, so his upbringing had largely been in the hands of his three older sisters who were nearly adults by then. In later years he had difficulty in remembering his mother, and his only memory of her death and funeral was of the children being sent for and going into her room, and his "Father meeting us crying afterwards".

As had been planned previously, in September 1818 Charles joined his older brother Erasmus Alvey Darwin

Erasmus Alvey Darwin (29 December 1804 ŌĆō 26 August 1881), nicknamed ''Eras'' or ''Ras'', was the older brother of Charles Darwin, born five years earlier. They were brought up at the family home, The Mount House, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, Eng ...

(nicknamed "Eras") in staying as a boarder at the Shrewsbury School

Shrewsbury School is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13 ŌĆō18) in Shrewsbury.

Founded in 1552 by Edward VI by Royal Charter, it was originally a boarding school for boys; girls have been admitted into ...

, where he loathed the required rote learning

Rote learning is a memorization technique based on repetition. The method rests on the premise that the recall of repeated material becomes faster the more one repeats it. Some of the alternatives to rote learning include meaningful learning, ...

, and would try to visit home when he could, but also made many friends and developed interests. Years later, he recalled being "very fond of playing at Hocky on the ice in skates" in the winter time. He continued collecting minerals and insects, and family holidays in Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

brought Charles new opportunities, but an older sister ruled that "it was not right to kill insects" for his collections, and he had to find dead ones. He read Gilbert White

Gilbert White FRS (18 July 1720 ŌĆō 26 June 1793) was a " parson-naturalist", a pioneering English naturalist, ecologist, and ornithologist. He is best known for his ''Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne''.

Life

White was born on ...

's ''The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne'' and took up birdwatching

Birdwatching, or birding, is the observing of birds, either as a recreational activity or as a form of citizen science. A birdwatcher may observe by using their naked eye, by using a visual enhancement device like binoculars or a telescope, by ...

. Eras took an interest in chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the elements that make up matter to the compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions: their composition, structure, proper ...

and Charles became his assistant, with the two using a garden shed at their home fitted out as a laboratory and extending their interests to crystallography

Crystallography is the experimental science of determining the arrangement of atoms in crystalline solids. Crystallography is a fundamental subject in the fields of materials science and solid-state physics ( condensed matter physics). The wor ...

. When Eras went on to a medical course at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, Charles continued to rush home to the shed on weekends, and for this received the nickname "Gas". The headmaster was not amused at this diversion from studying the classics, calling him a '' poco curante'' (trifler) in front of the boys. At fifteen, his interest shifted to hunting and bird-shooting at local estates, particularly at Maer in Staffordshire, the home of his relatives, the Wedgwood

Wedgwood is an English fine china, porcelain and luxury accessories manufacturer that was founded on 1 May 1759 by the potter and entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood and was first incorporated in 1895 as Josiah Wedgwood and Sons Ltd. It was rapid ...

s. His exasperated father once told him off, saying "You care for nothing but shooting, dogs, and rat-catching, and you will be a disgrace to yourself and all your family."

His father decided that he should leave school earlier than usual, and in 1825 at the age of sixteen Charles was to go along with his brother who was to attend the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dh├╣n ├łideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 1 ...

for a year to obtain medical qualifications. Charles spent the summer as an apprentice doctor, helping his father with treating the poor of Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

. He had half a dozen patients of his own, and would note their symptoms for his father to make up the prescriptions.

University of Edinburgh

In October 1825, Darwin went to

In October 1825, Darwin went to Edinburgh University

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dh├╣n ├łideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted ...

to study medicine, accompanied by Eras doing his external hospital study. For a few days, while looking for rooms to rent, the brothers stayed at the Star Hotel in Princes Street. They took up an introduction to a friend of their father, Dr. Hawley, who led them on a walk around the town. They admired it immensely; Darwin thought Bridge Street "most extraordinary" as, on looking over the sides, "instead of a fine river we saw a stream of people". They found comfortable lodgings near the University at 11 Lothian Street, on 22 October Charles signed the matriculation

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term "matriculation" is seldom used now ...

book, and enrolled in courses. That evening, they moved in.

Darwin attended classes from their start on 26 October. By early January he had formed opinions on the lecturers, and complained that most were boring.

Andrew Duncan, the younger

Andrew Duncan, the younger (10 August 1773 ŌĆō 13 May 1832) was a British physician and professor at the University of Edinburgh.

Life

Duncan was the son of Elizabeth Knox and Andrew Duncan, the elder, born at Adam Square in Edinburgh on 10 A ...

, taught dietetics

A dietitian, medical dietitian, or dietician is an expert in identifying and treating disease-related malnutrition and in conducting medical nutrition therapy, for example designing an enteral tube feeding regimen or mitigating the effects of ...

, pharmacy

Pharmacy is the science and practice of discovering, producing, preparing, dispensing, reviewing and monitoring medications, aiming to ensure the safe, effective, and affordable use of medication, medicines. It is a miscellaneous science as it ...

, and materia medica. Darwin thought the latter stupid, and said Duncan was "so very learned that his wisdom has left no room for his sense". His lectures began at 8a.m. ŌĆō years later Darwin recalled "a whole, cold, breakfastless hour on the properties of rhubarb!", but they usefully introduced him to the ''natural system'' of classification of Augustin de Candolle

Augustin Pyramus (or Pyrame) de Candolle (, , ; 4 February 17789 September 1841) was a Swiss botanist. Ren├® Louiche Desfontaines launched de Candolle's botanical career by recommending him at a herbarium. Within a couple of years de Candolle ...

, who emphasised the "war" between competing species.

From 10a.m., the brothers greatly enjoyed the spectacular chemistry lectures of Thomas Charles Hope

Thomas Charles Hope (21 July 1766 ŌĆō 13 June 1844) was a British physician, chemist and lecturer. He proved the existence of the element strontium, and gave his name to Hope's Experiment, which shows that water reaches its maximum density at ...

, but they did not join a student society giving hands-on experience. Anatomy and surgery classes began at noon, Darwin was disgusted by the dull and outdated anatomy lectures of professor Alexander Monro ''tertius'', many students went instead to private independent schools, with new ideas of teaching by dissecting corpses (giving clandestine trade to bodysnatchers) ŌĆō his brother went to a "charming Lecturer", the surgeon John Lizars

Prof John Lizars FRSE (15 May 1792ŌĆō21 May 1860) was a Scottish surgeon, anatomist and medical author.

He was Professor of surgery at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh and senior surgeon at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. He perfor ...

. Darwin later regretted his own failure to persevere and learn dissection.The city was in an uproar over political and religious controversies, and the competitive system where professors were dependent on attracting student fees for income meant that the university was riven with argumentative feuds and conflicts. Monro's lectures included vehement opposition to George Combe

George Combe (21 October 1788 ŌĆō 14 August 1858) was a trained Scottish lawyer and a spokesman of the phrenological movement for over 20 years. He founded the Edinburgh Phrenological Society in 1820 and wrote a noted study, ''The Constitution o ...

's daringly materialist

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materiali ...

ideas of phrenology

Phrenology () is a pseudoscience which involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits.Wihe, J. V. (2002). "Science and Pseudoscience: A Primer in Critical Thinking." In ''Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience'', pp. 195ŌĆō203. C ...

, but Darwin found "his lectures on human anatomy as dull, as he was himself, and the subject disgusted me." Eventually, to Darwin's mind there were "no advantages and many disadvantages in lectures compared with reading."

Darwin regularly attended clinical wards in the hospital despite his great distress about some of the cases, but could only bear to attend surgical operations twice, rushing away before they were completed due to his distress at the brutality of surgery before anaesthetic

An anesthetic (American English) or anaesthetic (British English; see spelling differences) is a drug used to induce anesthesiaŌĆēŌüĀŌĆöŌĆēŌüĀin other words, to result in a temporary loss of sensation or awareness. They may be divided into two ...

s. He was long haunted by the memory, particularly of an operation on a child.

At the end of January, Darwin wrote home that they had "been very dissipated", having dined with Dr. Hawley then gone to the theatre with a relative of the botanist Robert Kaye Greville

Dr. Robert Kaye Greville FRSE FLS LLD (13 December 1794 – 4 June 1866) was an English mycologist, bryologist, and botanist. He was an accomplished artist and illustrator of natural history. In addition to art and science he was interest ...

. They also visited "the old Dr. Duncan", who spoke with the warmest affection about his student and friend Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 ŌĆō 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

(Darwin's uncle) who had died in 1778.Woodall, Edward (1884)Charles Darwin. A paper contributed to the Transactions of the Shropshire Arch├”ological Society

London: Trubner. p. 18. Darwin wrote "What an extraordinary old man he is, now being past 80, & continuing to lecture", though Dr. Hawley thought Duncan was now failing. Darwin added that "I am going to learn to stuff birds, from a blackamoor... he only charges one guinea, for an hour every day for two months". These lessons in

taxidermy

Taxidermy is the art of preserving an animal's body via mounting (over an armature) or stuffing, for the purpose of display or study. Animals are often, but not always, portrayed in a lifelike state. The word ''taxidermy'' describes the proc ...

were with the freed black slave John Edmonstone, who also lived in Lothian Street. Darwin often sat with him to hear tales of the South American rain-forest of Guyana

Guyana ( or ), officially the Cooperative Republic of Guyana, is a country on the northern mainland of South America. Guyana is an indigenous word which means "Land of Many Waters". The capital city is Georgetown. Guyana is bordered by the ...

, and later remembered him as "a very pleasant and intelligent man."

The brothers kept each other company, and made extensive use of the library. Darwin's reading included novels and Boswell's ''Life of Johnson

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energy tran ...

''. He had brought natural history books with him, including a copy of ''A Naturalist's Companion'' by George Graves, bought in August in anticipation of seeing the seaside. He borrowed similar books from the library, and also read Fleming's ''Philosophy of Zoology''.

The brothers went for regular Sunday walks to the seaport of Leith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by ''Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

and the shores of the Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is the estuary, or firth, of several Scottish rivers including the River Forth. It meets the North Sea with Fife on the north coast and Lothian on the south.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate of ''fjord'', a Norse word meani ...

. Darwin kept a diary recording bird observations, and their seashore finds which began with a sea mouse (''Aphrodita aculeata

''Aphrodita aculeata'', the sea mouse, is a marine polychaete worm found in the North Atlantic, the North Sea, the Baltic Sea and the Mediterranean. The sea mouse normally lies buried head-first in the sand. It has been found at depths of over ...

)'' he caught on 2 February and identified from his copy of William Turton

William Turton (21 May 1762 ŌĆō 28 December 1835) was an English physician and naturalist. He is known for his pioneering work in conchology, and for translating Linnaeus' ''Systema Naturae'' into English.

Biography

He was born at Olveston, ...

's ''British fauna''.Darwin, C. R. dinburgh diary for 1826br>CUL-DAR129- Transcribed and edited by John van Wyhe (Darwin Online) A few days later Darwin noted "Erasmus caught a Cuttle fish", wondering if it was "Sepia Loligo", then from his textbooks identified it as '' Loligo sagittata'' (a squid). A few days later, Darwin returned with a basin and caught a globular orange zoophyte, then after storms at the start of March saw the shore "literally covered with Cuttle fish". He touched them so they emitted ink and swam away, and also found a damaged starfish beginning to regrow its arms. Eras completed his external hospital study, and returned to Shrewsbury, Darwin found other zoophytes and, on the shore "between Leith & Portobello", caught more sea mice which "when thrown into the sea rolled themselves up like hedgehogs." On 27 March, Susan Darwin wrote to pass on their father's disapproval of Darwin's "plan of picking & chusing what lectures you like to attend", as "you cannot have enough information to know what may be of use to you". His son's "present indulgent way" would make studies "utterly useless", and he wanted Darwin to complete the course. Darwin wrote home apologetically on 8 April with the news that "Dr. Hope has been giving some very good Lectures on Electricity &c. and I am very glad I stayed for them", requesting money to fund staying on another 9 to 14 days. During his summer holiday Charles read ''

Zo├Čnomia

''Zoonomia; or the Laws of Organic Life'' (1794-96) is a two-volume medical work by Erasmus Darwin dealing with pathology, anatomy, psychology, and the functioning of the body. Its primary framework is one of associationist psychophysiology. The ...

'' by his grandfather Erasmus Darwin

Erasmus Robert Darwin (12 December 173118 April 1802) was an English physician. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor, and poet.

His poems ...

, which his father valued for medical guidance but which also proposed evolution by acquired characteristics. In June he went on a walking tour in North Wales.

Natural history in second year

In October Charles returned on his own for his second year, and took smaller lodgings in a top flat at 21 Lothian Street. He joined the required classes of Practice of Physic and Midwifery, but by then realised he would inherit property and need not make "any strenuous effort to learn medicine". For his own interests, and to meet other students, he joinedRobert Jameson

Robert Jameson

Robert Jameson FRS FRSE (11 July 1774 ŌĆō 19 April 1854) was a Scottish naturalist and mineralogist.

As Regius Professor of Natural History at the University of Edinburgh for fifty years, developing his predecessor John ...

's natural history course which started on 8 November. It was unique in Britain, covering a wide range of topics including geology, zoology, mineralogy, meteorology and botany.Ashworth, J.H. (1935) Charles Darwin as a student in Edinburgh

1825-1827.'' Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 55: 97-113, pls. 1-2. Jameson was a Neptunian geologist who taught Werner's view that all rock

strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as e ...

had precipitated from a universal ocean, and founded the Wernerian Natural History Society to discuss and publish science. He encouraged debate, and in lectures pointedly disagreed with chemistry professor Hope

Hope is an optimistic state of mind that is based on an expectation of positive outcomes with respect to events and circumstances in one's life or the world at large.

As a verb, its definitions include: "expect with confidence" and "to cherish ...

who held that granites had crystallised from molten crust, influenced by the Plutonism

Plutonism is the geologic theory that the igneous rocks forming the Earth originated from intrusive magmatic activity, with a continuing gradual process of weathering and erosion wearing away rocks, which were then deposited on the sea bed, re-f ...

of James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June O.S.172614 June 1726 New Style. ŌĆō 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, agriculturalist, chemical manufacturer, naturalist and physician. Often referred to as the father of modern geology, he played a key role ...

who had been Hope's friend. In 1827, Jameson told a commission of inquiry into the curriculum that "It would be a misfortune if we all had the same way of thinking... Dr Hope is decidedly opposed to me, and I am opposed to Dr Hope, and between us we make the subject interesting."

Jameson edited the quarterly '' Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal'', with an international reputation for publishing science. It could touch on controversial subjects; in the AprilŌĆōOctober 1826 edition an anonymous paper proposed that geological study of fossils could "lift the veil that hangs over the origin and progress of the organic world". It praised Lamarck's transmutation of species

Transmutation of species and transformism are unproven 18th and 19th-century evolutionary ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection. The French ''Transformisme'' was a term used ...

concept that from "the simplest worms" arising by spontaneous generation and affected by external circumstances, all other animals "are evolved from these in a double series, and in a gradual manner." This was the first use of the word "evolved" in a modern sense, and the first significant statement to relate Lamarck's concepts to the geological fossil record. It seems likely that Jameson wrote it, but it could have been a former student of his, possibly Ami Bou├®

Ami Bou├® (16 March 179421 November 1881) was a geologist of French Huguenot origin. Born at Hamburg he trained in Edinburgh and across Europe. He travelled across Europe, studying geology, as well as ethnology, and is considered to be among th ...

.

Through family connections, Darwin was introduced to the reforming educationalist Leonard Horner

Leonard Horner FRSE FRS FGS (17 January 1785 – 5 March 1864) was a Scottish merchant, geologist and educational reformer. He was the younger brother of Francis Horner.

Horner was a founder of the School of Arts of Edinburgh, now Heriot-Wa ...

who took him to the opening of the 1826ŌĆō1827 session of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was established i ...

, presided over by Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 ŌĆō 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy ...

. Darwin "looked at him and at the whole scene with some awe and reverence".

Student societies

To make friends, Darwin hadvisiting card

A visiting card, also known as a calling card, is a small card used for social purposes. Before the 18th century, visitors making social calls left handwritten notes at the home of friends who were not at home. By the 1760s, the upper classes in ...

s printed, and joined student societies. He attended the Royal Medical Society

The Royal Medical Society (RMS) is a society run by students at the University of Edinburgh Medical School, Scotland. It claims to be the oldest medical society in the United Kingdom although this claim is also made by the earlier London-based ...

regularly though uninterested in its medical topics, and remembered James Kay-Shuttleworth

Sir James Phillips Kay-Shuttleworth, 1st Baronet (20 July 1804 ŌĆō 26 May 1877, born James Kay) of Gawthorpe Hall, Lancashire, was a British politician and educationist. He founded a further-education college that would eventually become Ply ...

as a good speaker.

On 21 November 1826 Darwin (17 years old) petitioned to join the Plinian Society

The Plinian Society was a club at the University of Edinburgh for students interested in natural history. It was founded in 1823. Several of its members went on to have prominent careers, most notably Charles Darwin who announced his first scient ...

, student-run, with professors excluded. At its Tuesday evening meetings, members read short papers, sometimes controversial, mostly on natural history topics or about their research excursions. The secretary minuted the titles, any publication was in other journals. Three of its five presidents proposed him for membership: William A. F. Browne (21), John Coldstream

John Coldstream (1806ŌĆō1863) was a Scottish physician.

Life

Coldstream, only son of Robert Coldstream, merchant in Timber Bush, by his wife Elizabeth, daughter of John Phillips of Stobcross, Glasgow, was born at Leith on 19 March 1806, and aft ...

(19) and medical student George Fife (19). A week later, Darwin was elected, as was William R. Greg (17) who offered a controversial talk to prove "the lower animals possess every faculty & propensity of the human mind", in a materialist

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materiali ...

view of nature as just physical forces. Darwin was elected to its Council on 5 December, at the same meeting Browne, a radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

* Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe an ...

demagogue opposed to church doctrines, attacked Charles Bell

Sir Charles Bell (12 November 177428 April 1842) was a Scottish surgeon, anatomist, physiologist, neurologist, artist, and philosophical theologian. He is noted for discovering the difference between sensory nerves and motor nerves in the spin ...

's ''Anatomy and Physiology of Expression'' (which in 1872 Darwin addressed in ''The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

''The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals'' is Charles Darwin's third major work of evolutionary theory, following ''On the Origin of Species'' (1859) and '' The Descent of Man'' (1871). Initially intended as a chapter in ''The Desce ...

''), flatly rejecting Bell's belief that the Creator had endowed humans with unique anatomical features. Greg and Browne were both avid proponents of phrenology

Phrenology () is a pseudoscience which involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits.Wihe, J. V. (2002). "Science and Pseudoscience: A Primer in Critical Thinking." In ''Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience'', pp. 195ŌĆō203. C ...

to undermine aristocratic rule. Darwin found the meetings stimulating and attended 17, missing only one.

Darwin became friends with Coldstream who was "prim, formal, highly religious and most kind-hearted". Coldstream's interest in the skies and identifying sea creatures on the

Darwin became friends with Coldstream who was "prim, formal, highly religious and most kind-hearted". Coldstream's interest in the skies and identifying sea creatures on the Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is the estuary, or firth, of several Scottish rivers including the River Forth. It meets the North Sea with Fife on the north coast and Lothian on the south.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate of ''fjord'', a Norse word meani ...

shore went back to his childhood in Leith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by ''Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

. He had joined the Plinian in 1823, his diary around then noted self-blame and torment, but he persisted and in 1824 became one of its presidents. He regularly published in the ''Edinburgh Philosophical Journal

The ''Edinburgh Philosophical Journal'' was founded by its editors Robert Jameson and David Brewster in 1819 as a scientific journal to publish articles on the latest science of the day. In 1826 the two editors fell out, and Jameson continued publ ...

'', and also assisted the research of Robert Edmond Grant

Robert Edmond Grant MD FRCPEd FRS FRSE FZS FGS (11 November 1793 ŌĆō 23 August 1874) was a British anatomist and zoologist.

Life

Grant was born at Argyll Square in Edinburgh (demolished to create Chambers Street), the son of Alexander Gra ...

, who had studied under Jameson before graduating in 1814, and was researching simple marine life

Marine life, sea life, or ocean life is the plants, animals and other organisms that live in the salt water of seas or oceans, or the brackish water of coastal estuaries. At a fundamental level, marine life affects the nature of the planet. ...

forms for evidence of the transmutation conjectured in Erasmus Darwin's ''Zoonomia

''Zoonomia; or the Laws of Organic Life'' (1794-96) is a two-volume medical work by Erasmus Darwin dealing with pathology, anatomy, psychology, and the functioning of the body. Its primary framework is one of associationist psychophysiology. Th ...

'' and Lamarck's writings. Grant was active in the Plinian and on the council of the Wernerian Society, where he took Darwin as a guest to meetings. The Wernerian was visited by John James Audubon

John James Audubon (born Jean-Jacques Rabin; April 26, 1785 ŌĆō January 27, 1851) was an American self-trained artist, naturalist, and ornithologist. His combined interests in art and ornithology turned into a plan to make a complete pictori ...

three times that winter, and Darwin saw his lectures on the habits of North American birds.

Fife

Fife (, ; gd, Fìobha, ; sco, Fife) is a council area, historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. It is situated between the Firth of Tay and the Firth of Forth, with inland boundaries with Perth and Kinross ...

and the islands. On the Isle of May

The Isle of May is located in the north of the outer Firth of Forth, approximately off the coast of mainland Scotland. It is about long and wide. The island is owned and managed by NatureScot as a national nature reserve. There are now no ...

with the botanist Robert Kaye Greville

Dr. Robert Kaye Greville FRSE FLS LLD (13 December 1794 – 4 June 1866) was an English mycologist, bryologist, and botanist. He was an accomplished artist and illustrator of natural history. In addition to art and science he was interest ...

, this "eminent cryptogam

A cryptogam (scientific name Cryptogamae) is a plant (in the wide sense of the word) or a plant-like organism that reproduces by spores, without flowers or seeds. The name ''Cryptogamae'' () means "hidden reproduction", referring to the fact ...

ist" laughed so much at screeching seabirds that he had to "lie down on the greensward to enjoy his prolonged cachinnation." On another trip, Darwin and Ainsworth got stuck overnight on Inchkeith

Inchkeith (from the gd, Innis Cheith) is an island in the Firth of Forth, Scotland, administratively part of the Fife council area.

Inchkeith has had a colourful history as a result of its proximity to Edinburgh and strategic location for u ...

and had to stay in the lighthouse.Bettany, G. T. (1887) ''Life of Charles Darwin''. London: Walter Scott, pp22ŌĆō23

also Routes to the Firth soon became familiar, and after another student presented a paper to the Plinian in the common literary form of describing the sights from a journey, Darwin and William Kay (another president) drafted a parody, to be read taking turns, describing "a complete failure" of an excursion from the university via

Holyrood House

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly referred to as Holyrood Palace or Holyroodhouse, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edi ...

, where Salisbury Craigs, ruined by quarrying, were completely hidden by " dense & impenetrable mist", along a dirty track to Portobello shore, where "Inch Keith, the Bas-rock, the distant hills in Fifeshire" were similarly hidden ŌĆō the sole sight of interest, as Dr Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 ŌĆō 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford D ...

had said, was the "high-road to England". High tide prevented any seashore finds so, rejecting "Haggis

Haggis ( gd, taigeis) is a savoury pudding containing sheep's pluck (heart, liver, and lungs), minced with onion, oatmeal, suet, spices, and salt, mixed with stock, and cooked while traditionally encased in the animal's stomach though n ...

or Scotch Collops", they dined on (English) "Beef-steak".

Geology and ''Origin of the Species''

Jameson's own main topic wasmineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proce ...

, his natural history course covered zoology and geology, with instruction on meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did no ...

and hydrography

Hydrography is the branch of applied sciences which deals with the measurement and description of the physical features of oceans, seas, coastal areas, lakes and rivers, as well as with the prediction of their change over time, for the prima ...

, and some discussion on botany as it related to "the animal and mineral kingdoms." Lectures began on 9 November and were on five days a week for five months (ending a week into April). Zoology began with the natural history of man, followed by chief classes of vertebrates and invertebrates, then concluded with philosophy of zoology starting with "Origin of the Species of Animals". As well as field lectures, the course made full use of the Royal Museum of the University which Jameson had developed into one of the largest in Europe. Darwin's flat was near the entrance to the museum in the western part of the university, he assisted and made full use of the collections, spending hours studying, taking notes and stuffing specimens. He "had much interesting natural-history talk" with the curator, William MacGillivray

William MacGillivray FRSE (25 January 1796 ŌĆō 4 September 1852) was a Scottish naturalist and ornithologist.

Life and work

MacGillivray was born in Old Aberdeen and brought up on Harris. He returned to Aberdeen where he studied Medicine a ...

, who later published a book on the birds of Scotland.

The geology course gave Darwin a grounding in mineralogy and stratigraphy

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers ( strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithost ...

geology. He bought Jameson's 1821 ''Manual of Mineralogy'', its first part classifies minerals comprehensively on the system of Friedrich Mohs

Carl Friedrich Christian Mohs (; 29 January 1773 ŌĆō 29 September 1839) was a German chemist and mineralogist. He was the creator of the Mohs scale of mineral hardness. Mohs also introduced a classification of the crystal forms in crystal syst ...

, the second part includes concepts of field geology such as defining strike and dip

Strike and dip is a measurement convention used to describe the orientation, or attitude, of a planar geologic feature. A feature's strike is the azimuth of an imagined horizontal line across the plane, and its dip is the angle of inclination ...

of strata. Darwin heavily annotated his copy of the book, sometimes when in lectures (though not always paying attention), and noted where it related to museum exhibits. He also read Jameson's translation of Cuvier

Jean L├®opold Nicolas Fr├®d├®ric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 ŌĆō 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in nat ...

's ''Essay on the Theory of the Earth '', covering fossils and extinctions in revolutions such as the Flood. In the preface, Jameson said geology discloses "the history of the first origin of organic beings, and traces their gradual from the monade to man himself".

The lectures were heavy going for a young student, and Darwin remembered Jameson as an "old brown, dry stick", He recalled Jameson's lectures as "incredibly dull. The sole effect they produced on me was the determination never as long as I lived to read a book on Geology or in any way to study the science. Yet I feel sure that I was prepared for a philosophical treatment of the subject", and he had been delighted when he read an explanation for erratic boulder

A glacial erratic is glacially deposited rock differing from the type of rock native to the area in which it rests. Erratics, which take their name from the Latin word ' ("to wander"), are carried by glacial ice, often over distances of hundred ...

s.

Jameson still held to Werner's Neptunist concept that phenomena such as trap

A trap is a mechanical device used to capture or restrain an animal for purposes such as hunting, pest control, or ecological research.

Trap or TRAP may also refer to:

Art and entertainment Films and television

* ''Trap'' (2015 film), Fil ...

dykes had precipitated from a universal ocean. By then, geologists increasingly accepted that trap rock had igneous

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or ...

origins, a Plutonist view promoted by Hope

Hope is an optimistic state of mind that is based on an expectation of positive outcomes with respect to events and circumstances in one's life or the world at large.

As a verb, its definitions include: "expect with confidence" and "to cherish ...

, who had been James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June O.S.172614 June 1726 New Style. ŌĆō 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, agriculturalist, chemical manufacturer, naturalist and physician. Often referred to as the father of modern geology, he played a key role ...

's friend. From hearing exponents of both sides, Darwin learned the range of current opinion. His grandfather Erasmus had favoured Plutonism, and Darwin later supported Huttonian ideas. Almost fifty years after the course, Darwin recalled Jameson giving a field lecture at Salisbury Crags, "discoursing on a trap-dyke" with "volcanic rocks all around us", saying it was "a fissure filled with sediment from above, adding with a sneer that there were men who maintained that it had been injected from beneath in a molten condition. When I think of this lecture, I do not wonder that I determined never to attend to Geology."

Sealife homologies and monads

In hisautobiography

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life.

It is a form of biography.

Definition

The word "autobiography" was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English peri ...

, begun in 1876, Darwin remembered Robert Edmond Grant

Robert Edmond Grant MD FRCPEd FRS FRSE FZS FGS (11 November 1793 ŌĆō 23 August 1874) was a British anatomist and zoologist.

Life

Grant was born at Argyll Square in Edinburgh (demolished to create Chambers Street), the son of Alexander Gra ...

as "dry and formal in manner, but with much enthusiasm beneath this outer crust. He one day, when we were walking together burst forth in high admiration of Lamarck and his views on evolution. I listened in silent astonishment, and as far as I can judge, without any effect on my mind. I had previously read the Zo├Čnomia of my grandfather, in which similar views are maintained, but without producing any effect on me."

Grant's doctoral dissertation

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: ...

, prepared in 1813, cited Erasmus Darwin's ''Zo├Čnomia

''Zoonomia; or the Laws of Organic Life'' (1794-96) is a two-volume medical work by Erasmus Darwin dealing with pathology, anatomy, psychology, and the functioning of the body. Its primary framework is one of associationist psychophysiology. The ...

'' which suggested that over geological time all organic life could have gradually arisen from a kind of "living filament" capable of heritable self-improvement. He found in Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 ŌĆō 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biolo ...

's similar uniformitarian theoretical framework

A theory is a rational type of abstract thinking about a phenomenon, or the results of such thinking. The process of contemplative and rational thinking is often associated with such processes as observational study or research. Theories may be s ...

a similar idea that spontaneously generated simple animal ''monad

Monad may refer to:

Philosophy

* Monad (philosophy), a term meaning "unit"

**Monism, the concept of "one essence" in the metaphysical and theological theory

** Monad (Gnosticism), the most primal aspect of God in Gnosticism

* ''Great Monad'', a ...

s'' continually improved in complexity and perfection, while use or disuse of features to adapt to environmental changes diversified species and genera.

Funded by a small inheritance, Grant went to Paris University in 1815, to study with Cuvier

Jean L├®opold Nicolas Fr├®d├®ric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 ŌĆō 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in nat ...

, the leading comparative anatomist, and his rival Geoffroy. Cuvier held that species were fixed, grouped into four entirely separate '' embranchements'', and any similarity of structures between species was merely due to functional needs. Grant favoured Geoffroy's view that similarities showed "unity of form", similar to Lamarck's ideas.

Like Lamarck, Grant investigated marine invertebrate

Marine invertebrates are the invertebrates that live in marine habitats. Invertebrate is a blanket term that includes all animals apart from the vertebrate members of the chordate phylum. Invertebrates lack a vertebral column, and some hav ...

s, particularly sponge

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate throu ...

s as naturalists disputed whether they were plants or animals. After specimen collecting and research in European universities, he returned to Edinburgh in 1820. Many species lived in the Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is the estuary, or firth, of several Scottish rivers including the River Forth. It meets the North Sea with Fife on the north coast and Lothian on the south.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate of ''fjord'', a Norse word meani ...

, and Grant got winter use of Walford House, Prestonpans

Prestonpans ( gd, Baile an t-Sagairt, Scots language, Scots: ''The Pans'') is a small mining town, situated approximately eight miles east of Edinburgh, Scotland, in the Council area of East Lothian. The population as of is. It is near the si ...

, with a garden gate in its high seawall leading to rock pools. He kept sponges alive in glass jars for long term observation, and at night used his microscope by candle light to dissect specimens in a watch glass

A watch glass is a circular concave piece of glass used in chemistry as a surface to evaporate a liquid, to hold solids while being weighed, for heating a small amount of substance and as a cover for a beaker. A larger watchglass may be referre ...

.

In spring 1825 at the ''Wernerian'', Grant dramatically dissected molluscs

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is estim ...

(squid

True squid are molluscs with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight arms, and two tentacles in the superorder Decapodiformes, though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also called squid despite not strictly fittin ...

and sea-slugs) showing they had a simple pancreas analogous to the complex pancreas in fish, controversially suggesting shared ancestry

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. All living beings are in fact descendants of a unique ancestor commonly referred to as the last universal co ...

between molluscs and Cuvier's "higher" ''embranchement'' of vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, with ...

s. In the ''Edinburgh Philosophical Journal

The ''Edinburgh Philosophical Journal'' was founded by its editors Robert Jameson and David Brewster in 1819 as a scientific journal to publish articles on the latest science of the day. In 1826 the two editors fell out, and Jameson continued publ ...

'' Grant revealed that sponges had cilia

The cilium, plural cilia (), is a membrane-bound organelle found on most types of eukaryotic cell, and certain microorganisms known as ciliates. Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea. The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike proje ...

to draw in water and expel waste, and their "ova" (larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

...

e) were self-propelled by cilia in "spontaneous motion" like that seen by Cavolini in "ova" of the soft coral Gorgonia. In October he said simple freshwater ''Spongilla

Overview

''Spongilla'' is a genus of freshwater sponges with over 200 different species. Spongilla was first publicly recognized in 1696 by Leonard Plukenet and can be found in lakes, ponds and slow streams.''Spongilla'' have a leuconoid body f ...

'' were ancient, ancestral to complex sponges that had adapted to sea changes, as the earth cooled and changing conditions drove life towards higher, hotter blooded forms. In May 1826 he said that "future observations" would determine if self-propelling "ova" were "general with zoophytes", his conclusions published in December included a detailed description of how sponge ova contain "monads-like bodies", and "swim about" by "the rapid vibration of cili├”". ŌĆō p129

says sponge ova "swim about" by "the rapid vibration of cili├”".

Coldstream assisted Grant, and that winter Darwin joined the search, learning what to look for, and dissection techniques using a portable microscope. On 16 March 1827 he noted in a new notebook that he had "Procured from the black rocks at Leith" a

Coldstream assisted Grant, and that winter Darwin joined the search, learning what to look for, and dissection techniques using a portable microscope. On 16 March 1827 he noted in a new notebook that he had "Procured from the black rocks at Leith" a lumpfish

The Cyclopteridae are a family of marine fishes, commonly known as lumpsuckers or lumpfish, in the order Scorpaeniformes. They are found in the cold waters of the Arctic, North Atlantic, and North Pacific oceans. The greatest number of species ...

, "Dissected it with Dr Grant". Two days later he recorded "ova from the Newhaven rocks" said to be of the Doris ea slug"in rapid motion, & continued so for 7 days", then on 19 March saw ova of the ''Flustra foliacea

''Flustra foliacea'' is a species of bryozoans found in the northern Atlantic Ocean. It is a colonial animal that is frequently mistaken for a seaweed. Colonies begin as encrusting mats, and only produce loose fronds after their first year of gr ...

'' in motion. As recalled in his autobiography, he made "one interesting little discovery" that "the so-called ova of Flustra had the power of independent movement by means of cilia, and were in fact larv├”", and also that little black globular bodies found sticking to empty oyster shells, once thought to be the young of '' Fucus loreus'', were egg-cases (cocoons) of the ''Pontobdella muricata

''Pontobdella muricata'' is a species of marine leech in the family Piscicolidae. It is a parasite of fishes and is native to the northeastern Atlantic Ocean, the Baltic Sea, the North Sea, and the Mediterranean Sea.

Description

''Pontobdella mu ...

'' (skate leech). He believed "Dr. Grant noticed my small discovery in his excellent memoir on Flustra."

16ŌĆō18 March 1827

At the Plinian meeting, on 3 April, Darwin presented the Society with "A specimen of the ''Pontobdella muricata'', with its ova & young ones", but there is no record of the papers being presented or kept. Grant in his publication about the leech eggs in the ''Edinburgh Journal of Science'' for July 1827 acknowledged "The merit of having first ascertained them to belong to that animal is due to my zealous young friend Mr Charles Darwin of Shrewsbury", the first time Darwin's name appeared in print. Grant's lengthy memoir read before the Wernerian on 24 March was split between the April and October issues of the ''Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal'', with more detail than Darwin had given: he had seen ova (larvae) of ''Flustra carbasea'' in February, after they swam about they stuck to the glass and began to form a new colony. He noted the similarity of the cilia in "other ova", with reference to his 1826 publication describing sponge ova. Darwin was not given credit for what he felt was his discovery, and in 1871, when he discussed "the paltry feeling" of

scientific priority In science, priority is the credit given to the individual or group of individuals who first made the discovery or propose the theory. Fame and honours usually go to the first person or group to publish a new finding, even if several researchers arr ...

with his daughter Henrietta Henrietta may refer to:

* Henrietta (given name), a feminine given name, derived from the male name Henry

Places

* Henrietta Island in the Arctic Ocean

* Henrietta, Mauritius

* Henrietta, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

United States

* Henrie ...

, she got him to repeat the story of "his first introduction to the jealousy of scientific men"; when he had seen the ova of ''Flustra'' move he "rushed instantly to Grant" who, rather than being "delighted with so curious a fact", told Darwin "it was very unfair of him to work at Prof G's subject & in fact that he shd take it ill if my Father published it." In European university practice, team leaders reported research without naming assistants, and clearly the find was derivative from Grant's research programme: it seems likely he had already seen the ova, like the sponge ova, moving by cilia. Grant phased announcement of discoveries rather than publishing quickly, and was now looking for a professorship before he ran out of funds, but young Darwin was disappointed. As Jameson noted in October, back in 1823 Dalyell had observed the ''Pontobdella'' young leaving their cocoons.

In notes dated 15 and 23 April, Darwin described specimens of the deep-water sea pen

Sea pens are colonial marine cnidarians belonging to the order Pennatulacea. There are 14 families within the order; 35 extant genera, and it is estimated that of 450 described species, around 200 are valid. Sea pens have a cosm ...

s (from fishing boats), and on 23 April, "with Mr Coldstream at the black rocks at Leith", he saw a starfish

Starfish or sea stars are star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to as brittle stars or basket stars. Starfish a ...

doubled up, releasing its ova.

Summer 1827

Darwin left Edinburgh in late April, just 18 years old. In 1826 he had told his sister he would be "forced to go abroad for one year" of hospital studies, as he had to be 21 before taking his degree, but he was too upset by seeing blood or suffering, and had lost any ambition to be a doctor. He went a short tour, visitingDundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, D├╣n D├© or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

, St Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fourt ...

, Stirling

Stirling (; sco, Stirlin; gd, Sruighlea ) is a city in central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the royal citadel, the medieval old town with its me ...

, Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

, Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, B├®al Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdom ...

and Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

, then in May made his first trip to London to visit his sister Caroline. They joined his uncle Josiah Wedgwood II

Josiah Wedgwood II (3 April 1769 ŌĆō 12 July 1843), the son of the English potter Josiah Wedgwood, continued his father's firm and was a Member of Parliament (MP) for Stoke-upon-Trent from 1832 to 1835. He was an abolitionist, and detested slav ...

on a trip to France, and on 26 May arrived in Paris, where Charles fended for himself for a few weeks: recently graduated Plinian society members, including Browne and Coldstream, were there for hospital studies. By July, Charles had returned to his home at The Mount, Shrewsbury. While indulging his hobby of shooting

Shooting is the act or process of discharging a projectile from a ranged weapon (such as a gun, bow, crossbow, slingshot, or blowpipe). Even the acts of launching flame, artillery, darts, harpoons, grenades, rockets, and guided missiles ...

with his family's friends at the nearby Woodhouse estate of William Mostyn Owen, Darwin flirted with his second daughter, Frances Mostyn Owen.

Coldstream studied in Paris for a year, and visited places of interest. His diary notes religious thoughts, and occasional anguished comments such as "the foul mass of corruption within my own bosom", "corroding desires" and "lustful imaginations". A doctor who befriended him later said that though Coldstream had led "a blameless life", he was "more or less in the dark on the vital question of religion, and was troubled with doubts arising from certain Materialist views, which are, alas! too common among medical students." He left in June 1828 for a short tour on his way home, but fell ill in Westphalia

Westphalia (; german: Westfalen ; nds, Westfalen ) is a region of northwestern Germany and one of the three historic parts of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It has an area of and 7.9 million inhabitants.

The territory of the regio ...

, suffered a mental breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitt ...

, and got back to Leith late in July. In early December Coldstream began medical practice and gave it priority over natural history.

University of Cambridge

His father was unhappy that his younger son would not become a physician and "was very properly vehement against my turning into an idle sporting man, which then seemed my probable destination." He therefore enrolled Charles at

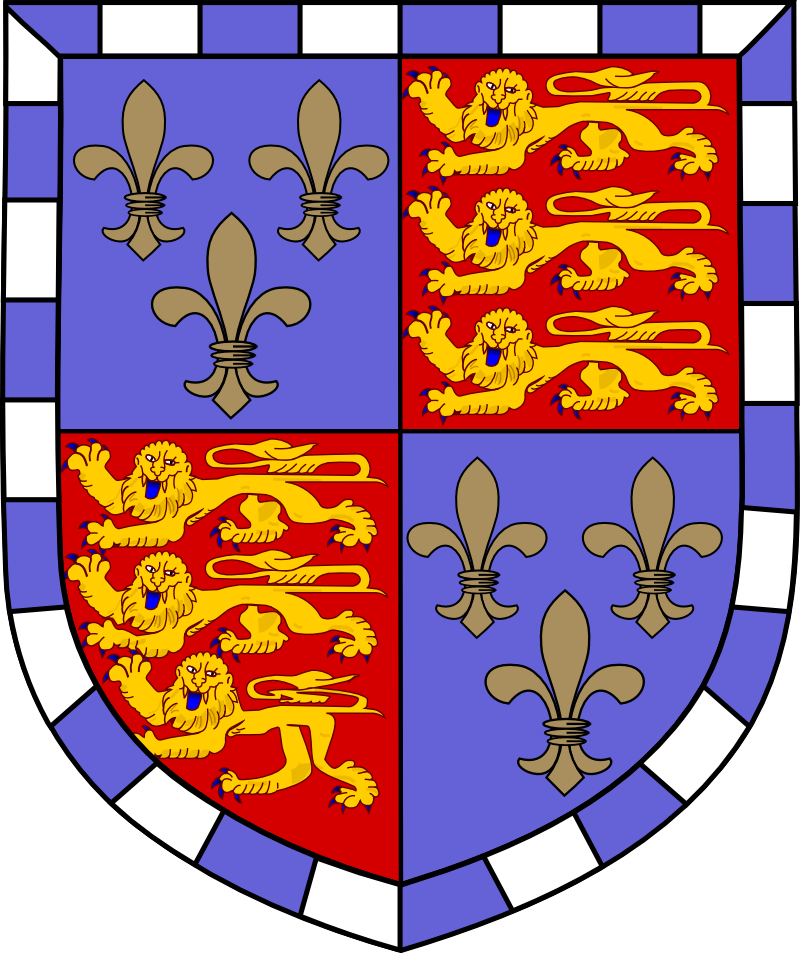

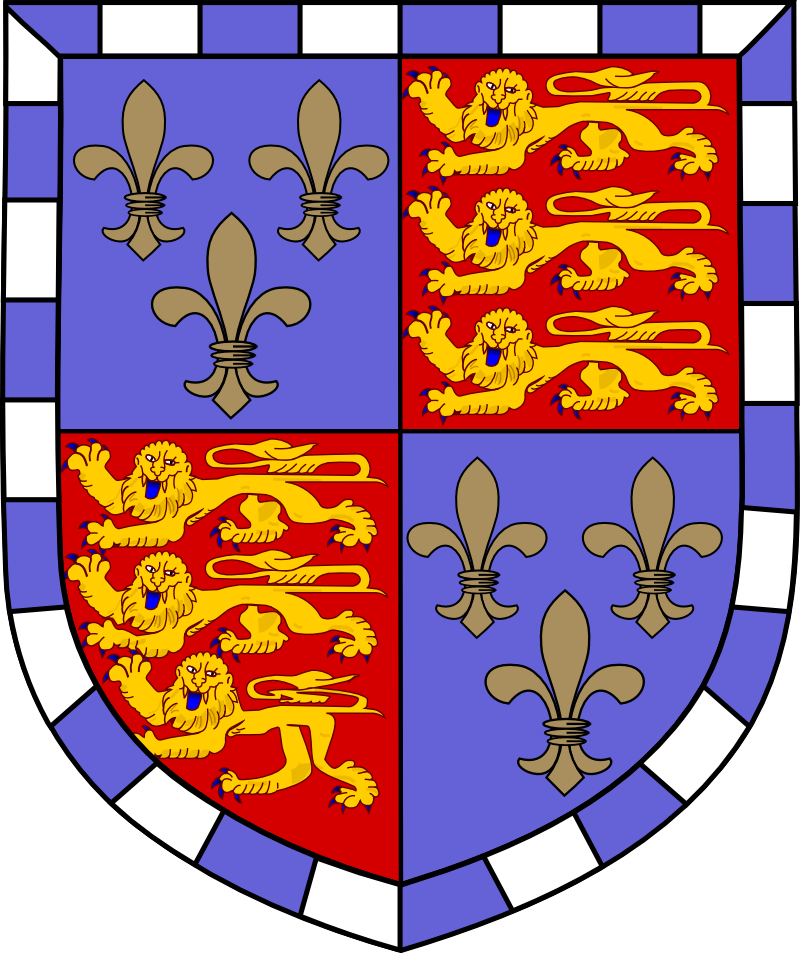

His father was unhappy that his younger son would not become a physician and "was very properly vehement against my turning into an idle sporting man, which then seemed my probable destination." He therefore enrolled Charles at Christ's College, Cambridge

Christ's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college includes the Master, the Fellows of the College, and about 450 undergraduate and 170 graduate students. The college was founded by William Byngham in 1437 as ...

in 1827 for a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four yea ...

degree as the qualification required before taking a specialised divinity course and becoming an Anglican parson. He enrolled for an '' ordinary'' degree, as at that time only capable mathematicians would take the Tripos

At the University of Cambridge, a Tripos (, plural 'Triposes') is any of the examinations that qualify an undergraduate for a bachelor's degree or the courses taken by a student to prepare for these. For example, an undergraduate studying mat ...