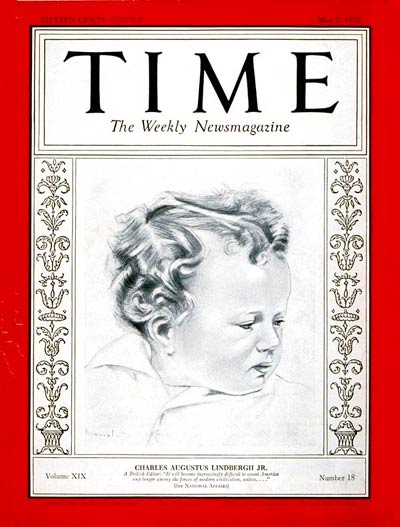

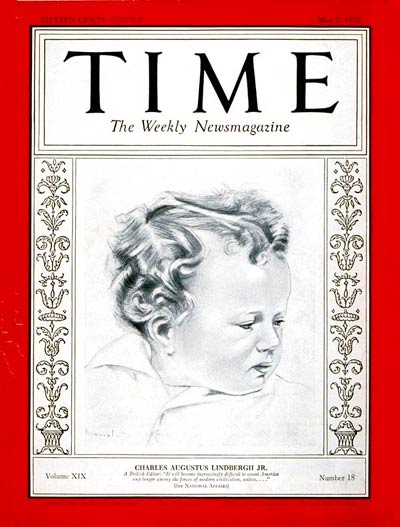

Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

On March 1, 1932, Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. (born June 22, 1930), the 20-month-old son of aviators

Hopewell Borough police and New Jersey State Police officers conducted an extensive search of the home and its surrounding area.

After midnight, a fingerprint expert examined the ransom note and ladder; no usable fingerprints or footprints were found, leading experts to conclude that the kidnapper(s) wore gloves and had some type of cloth on the soles of their shoes. No adult fingerprints were found in the baby's room, including in areas witnesses admitted to touching, such as the window, but the baby's fingerprints were found.

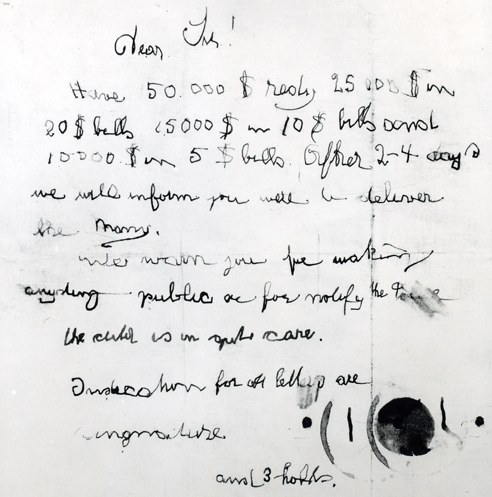

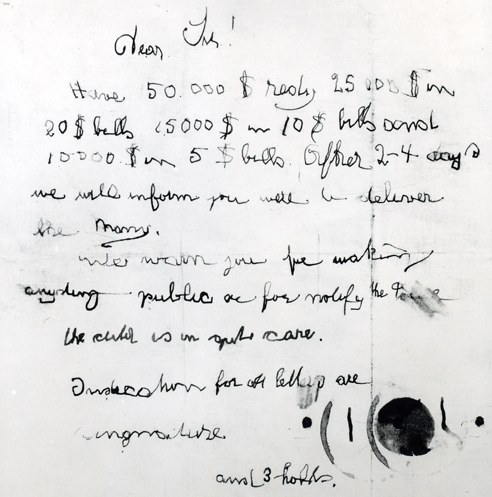

The brief, handwritten ransom note had many spelling and grammar irregularities:

At the bottom of the note were two interconnected blue circles surrounding a red circle, with a hole punched through the red circle and two more holes to the left and right.

On further examination of the ransom note by professionals, they found that it was all written by the same person. They determined that due to the odd English, the writer must have been foreign and had spent some, but little, time in America. The FBI then found a sketch artist to make a portrait of the man that they believed to be the kidnapper.

Another attempt on identifying the kidnapper was looking at the ladder that was used in the crime to abduct the child. Police realized that the ladder was not built correctly but was built by someone who knew how to construct with wood and had prior experience in building. The ladder was examined for fingerprints, but none were found. Even slivers of the ladder had been examined, with the police believing that the examination of this evidence would lead to the kidnapper. They had a professional see how many different types of wood were used, pattern made by the nail holes and if it was made indoors or outdoors. This would later be a key element in the trial of the man who was accused of kidnapping the Lindbergh baby.

On March 2, 1932,

Hopewell Borough police and New Jersey State Police officers conducted an extensive search of the home and its surrounding area.

After midnight, a fingerprint expert examined the ransom note and ladder; no usable fingerprints or footprints were found, leading experts to conclude that the kidnapper(s) wore gloves and had some type of cloth on the soles of their shoes. No adult fingerprints were found in the baby's room, including in areas witnesses admitted to touching, such as the window, but the baby's fingerprints were found.

The brief, handwritten ransom note had many spelling and grammar irregularities:

At the bottom of the note were two interconnected blue circles surrounding a red circle, with a hole punched through the red circle and two more holes to the left and right.

On further examination of the ransom note by professionals, they found that it was all written by the same person. They determined that due to the odd English, the writer must have been foreign and had spent some, but little, time in America. The FBI then found a sketch artist to make a portrait of the man that they believed to be the kidnapper.

Another attempt on identifying the kidnapper was looking at the ladder that was used in the crime to abduct the child. Police realized that the ladder was not built correctly but was built by someone who knew how to construct with wood and had prior experience in building. The ladder was examined for fingerprints, but none were found. Even slivers of the ladder had been examined, with the police believing that the examination of this evidence would lead to the kidnapper. They had a professional see how many different types of wood were used, pattern made by the nail holes and if it was made indoors or outdoors. This would later be a key element in the trial of the man who was accused of kidnapping the Lindbergh baby.

On March 2, 1932,

The morning after the kidnapping, authorities notified President

The morning after the kidnapping, authorities notified President

On May 12, delivery truck driver Orville Wilson and his assistant William Allen pulled to the side of a road about south of the Lindbergh home near the hamlet of Mount Rose in neighboring Hopewell Township. When Allen went into a grove of trees to urinate, he discovered the body of a toddler. The skull was badly fractured and the body decomposed, with evidence of scavenging by animals; there were indications of an attempt at a hasty burial. Gow identified the baby as the missing infant from the overlapping toes of the right foot and a shirt that she had made. It appeared the child had been killed by a blow to the head. Lindbergh insisted on cremation.

In June 1932, officials began to suspect that the crime had been perpetrated by someone the Lindberghs knew. Suspicion fell upon Violet Sharpe, a British household servant at the Morrow home who had given contradictory information regarding her whereabouts on the night of the kidnapping. It was reported that she appeared nervous and suspicious when questioned. She died by suicide on June 10, 1932, by ingesting a silver polish that contained

On May 12, delivery truck driver Orville Wilson and his assistant William Allen pulled to the side of a road about south of the Lindbergh home near the hamlet of Mount Rose in neighboring Hopewell Township. When Allen went into a grove of trees to urinate, he discovered the body of a toddler. The skull was badly fractured and the body decomposed, with evidence of scavenging by animals; there were indications of an attempt at a hasty burial. Gow identified the baby as the missing infant from the overlapping toes of the right foot and a shirt that she had made. It appeared the child had been killed by a blow to the head. Lindbergh insisted on cremation.

In June 1932, officials began to suspect that the crime had been perpetrated by someone the Lindberghs knew. Suspicion fell upon Violet Sharpe, a British household servant at the Morrow home who had given contradictory information regarding her whereabouts on the night of the kidnapping. It was reported that she appeared nervous and suspicious when questioned. She died by suicide on June 10, 1932, by ingesting a silver polish that contained

The investigators who were working on the case were soon at a standstill. There were no developments and little evidence of any sort, so police turned their attention to tracking the ransom payments. A pamphlet was prepared with the serial numbers on the ransom bills, and 250,000 copies were distributed to businesses, mainly in New York City. A few of the ransom bills appeared in scattered locations, some as far away as Chicago and

The investigators who were working on the case were soon at a standstill. There were no developments and little evidence of any sort, so police turned their attention to tracking the ransom payments. A pamphlet was prepared with the serial numbers on the ransom bills, and 250,000 copies were distributed to businesses, mainly in New York City. A few of the ransom bills appeared in scattered locations, some as far away as Chicago and

Hauptmann was charged with capital murder. The trial was held at the

Hauptmann was charged with capital murder. The trial was held at the

Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

and Anne Morrow Lindbergh

Anne Spencer Morrow Lindbergh (June 22, 1906 – February 7, 2001) was an American writer and aviator. She was the wife of decorated pioneer aviator Charles Lindbergh, with whom she made many exploratory flights.

Raised in Englewood, New Jerse ...

, was abducted from his crib in the upper floor of the Lindberghs' home, Highfields, in East Amwell, New Jersey

East Amwell Township is a township in Hunterdon County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the township's population was 4,013, reflecting a decline of 442 (−9.9%) from the 4,455 counted in the 2000 Census, which ...

, United States. On May 12, the child's corpse was discovered by a truck driver by the side of a nearby road.

In September 1934, a German immigrant carpenter named Bruno Richard Hauptmann

Bruno Richard Hauptmann (November 26, 1899 – April 3, 1936) was a German-born carpenter who was convicted of the abduction and murder of the 20-month-old son of aviator Charles Lindbergh and his wife Anne Morrow Lindbergh. The Lindbergh kidnap ...

was arrested for the crime. After a trial that lasted from January 2 to February 13, 1935, he was found guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced to death. Despite his conviction, he continued to profess his innocence, but all appeals failed and he was executed in the electric chair

An electric chair is a device used to execute an individual by electrocution. When used, the condemned person is strapped to a specially built wooden chair and electrocuted through electrodes fastened on the head and leg. This execution method, ...

at the New Jersey State Prison

The New Jersey State Prison (NJSP), formerly known as Trenton State Prison, is a state men's prison in Trenton, New Jersey operated by the New Jersey Department of Corrections. It is the oldest prison in New Jersey and one of the oldest correct ...

on April 3, 1936. Newspaper writer H. L. Mencken

Henry Louis Mencken (September 12, 1880 – January 29, 1956) was an American journalist, essayist, satirist, cultural critic, and scholar of American English. He commented widely on the social scene, literature, music, prominent politicians, ...

called the kidnapping and trial "the biggest story since the Resurrection

Resurrection or anastasis is the concept of coming back to life after death. In a number of religions, a dying-and-rising god is a deity which dies and is resurrected. Reincarnation is a similar process hypothesized by other religions, whic ...

". Legal scholars have referred to the trial as one of the " trials of the century". The crime spurred Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

to pass the Federal Kidnapping Act

Following the historic Lindbergh kidnapping (the abduction and murder of Charles Lindbergh's toddler son), the United States Congress passed a federal kidnapping statute—known as the Federal Kidnapping Act, (a)(1) (popularly known as the Lindb ...

, commonly called the "Little Lindbergh Law", which made transporting a kidnapping victim across state lines a federal crime.

Kidnapping

At approximately 10 p.m. on March 1, 1932, the Lindberghs' nurse, Betty Gow, found that 20-month-old Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. was not with his mother,Anne Morrow Lindbergh

Anne Spencer Morrow Lindbergh (June 22, 1906 – February 7, 2001) was an American writer and aviator. She was the wife of decorated pioneer aviator Charles Lindbergh, with whom she made many exploratory flights.

Raised in Englewood, New Jerse ...

, who had just come out of the bathtub. Gow then alerted Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

, who immediately went to the child's room, where he found a ransom note, containing bad handwriting and grammar, in an envelope on the windowsill. Taking a gun, Lindbergh went around the house and grounds with family butler, Olly Whateley; they found impressions in the ground under the window of the baby's room, pieces of a wooden ladder, and a baby's blanket. Whateley telephoned the Hopewell police department while Lindbergh contacted his attorney and friend, Henry Breckinridge, and the New Jersey state police.

Investigation

Hopewell Borough police and New Jersey State Police officers conducted an extensive search of the home and its surrounding area.

After midnight, a fingerprint expert examined the ransom note and ladder; no usable fingerprints or footprints were found, leading experts to conclude that the kidnapper(s) wore gloves and had some type of cloth on the soles of their shoes. No adult fingerprints were found in the baby's room, including in areas witnesses admitted to touching, such as the window, but the baby's fingerprints were found.

The brief, handwritten ransom note had many spelling and grammar irregularities:

At the bottom of the note were two interconnected blue circles surrounding a red circle, with a hole punched through the red circle and two more holes to the left and right.

On further examination of the ransom note by professionals, they found that it was all written by the same person. They determined that due to the odd English, the writer must have been foreign and had spent some, but little, time in America. The FBI then found a sketch artist to make a portrait of the man that they believed to be the kidnapper.

Another attempt on identifying the kidnapper was looking at the ladder that was used in the crime to abduct the child. Police realized that the ladder was not built correctly but was built by someone who knew how to construct with wood and had prior experience in building. The ladder was examined for fingerprints, but none were found. Even slivers of the ladder had been examined, with the police believing that the examination of this evidence would lead to the kidnapper. They had a professional see how many different types of wood were used, pattern made by the nail holes and if it was made indoors or outdoors. This would later be a key element in the trial of the man who was accused of kidnapping the Lindbergh baby.

On March 2, 1932,

Hopewell Borough police and New Jersey State Police officers conducted an extensive search of the home and its surrounding area.

After midnight, a fingerprint expert examined the ransom note and ladder; no usable fingerprints or footprints were found, leading experts to conclude that the kidnapper(s) wore gloves and had some type of cloth on the soles of their shoes. No adult fingerprints were found in the baby's room, including in areas witnesses admitted to touching, such as the window, but the baby's fingerprints were found.

The brief, handwritten ransom note had many spelling and grammar irregularities:

At the bottom of the note were two interconnected blue circles surrounding a red circle, with a hole punched through the red circle and two more holes to the left and right.

On further examination of the ransom note by professionals, they found that it was all written by the same person. They determined that due to the odd English, the writer must have been foreign and had spent some, but little, time in America. The FBI then found a sketch artist to make a portrait of the man that they believed to be the kidnapper.

Another attempt on identifying the kidnapper was looking at the ladder that was used in the crime to abduct the child. Police realized that the ladder was not built correctly but was built by someone who knew how to construct with wood and had prior experience in building. The ladder was examined for fingerprints, but none were found. Even slivers of the ladder had been examined, with the police believing that the examination of this evidence would lead to the kidnapper. They had a professional see how many different types of wood were used, pattern made by the nail holes and if it was made indoors or outdoors. This would later be a key element in the trial of the man who was accused of kidnapping the Lindbergh baby.

On March 2, 1932, FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

Director J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation � ...

got in contact with the Trenton New Jersey Police Department. He told the New Jersey police that they could contact the FBI for any resources and would provide any assistance if needed. The FBI did not have federal jurisdiction, until on May 13, 1932 the President declared that the FBI was at the disposal of the New Jersey Police Department and that the FBI should coordinate and conduct the investigation.

The New Jersey State police offered a $25,000 reward for anyone who could provide information pertaining to the case.

On March 4, 1932 a man by the name of Gaston B. Means

Gaston Bullock Means (July 11, 1879 – December 12, 1938) was an American private detective, salesman, bootlegger, forger, swindler, murder suspect, blackmailer, and con artist.

While not involved in the Teapot Dome scandal, Means was associ ...

had a discussion with Evalyn Walsh McLean

Evalyn McLean ( Walsh; August 1, 1886 – April 26, 1947) was an American mining heiress and socialite, famous for reputedly being the last private owner of the Hope Diamond (which was bought in 1911 for US$180,000 from Pierre Cartier), as we ...

and told her that he would be of great importance in retrieving the Lindbergh baby. Means told McLean that he could find these kidnappers because he was approached weeks before the abduction about participating in a "big kidnapping" and he claimed that his friend was the kidnapper of the Lindbergh child. The following day, Means told McLean that he had made contact with the person who had the Lindbergh child. He then convinced Mrs. McLean to hand him $100,000 to obtain the child because the ransom money had doubled. McLean obliged because she believed that Means really knew where the child was. She waited for the child's return every day, until she finally asked Means for her money back. He refused, Mrs. McLean reported him to the police, and he was sentenced to fifteen years in prison on embezzlement charges.

Violet Sharpe,In some sources, spelled as Violet Sharp who was suspected as a conspirator, died by suicide on June 10, before she was scheduled to be questioned for the fourth time. Her involvement was later ruled out due to her having an alibi for the night of March 1, 1932.

In 1933 Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

announced that the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

would take full jurisdiction over the case in October 1933.

Prominence

Word of the kidnapping spread quickly. Hundreds of people converged on the estate, destroying any footprint evidence. Along with police, well-connected and well-intentioned people arrived at the Lindbergh estate. Military colonels offered their aid, although only one had law enforcement expertise Herbert Norman Schwarzkopf, superintendent of the New Jersey State Police. The other colonels were Henry Skillman Breckinridge, a Wall Street lawyer; andWilliam J. Donovan

William Joseph "Wild Bill" Donovan (January 1, 1883 – February 8, 1959) was an American soldier, lawyer, intelligence officer and diplomat, best known for serving as the head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the Bur ...

, a hero of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

who would later head the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

. Lindbergh and these men speculated that the kidnapping was perpetrated by organized crime figures. They thought that the letter was written by someone who spoke German as his native language. At this time, Charles Lindbergh used his influence to control the direction of the investigation.

They contacted Mickey Rosner, a Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

hanger-on rumored to know mobsters. Rosner turned to two speakeasy

A speakeasy, also called a blind pig or blind tiger, is an illicit establishment that sells alcoholic beverages, or a retro style bar that replicates aspects of historical speakeasies.

Speakeasy bars came into prominence in the United States ...

owners, Salvatore "Salvy" Spitale and Irving Bitz, for aid. Lindbergh quickly endorsed the duo and appointed them his intermediaries to deal with the mob. Several organized crime figures – notably Al Capone, Willie Moretti

Guarino "Willie" Moretti (February 24, 1894 – October 4, 1951), also known as Willie Moore, was a notorious underboss of the Genovese crime family and a cousin of the family boss Frank Costello.

Criminal career

Born Guarino Moretti in Bari ...

, Joe Adonis

Joseph Anthony Doto (born Giuseppe Antonio Doto, ; November 22, 1902 – November 26, 1971), known as Joe Adonis, was an Italian-American mobster who was an important participant in the formation of the modern Cosa Nostra crime families in New Y ...

, and Abner Zwillman

Abner "Longie" Zwillman (July 27, 1904 – February 26, 1959) was a Jewish-American mobster who was based primarily in North Jersey. He was a long time friend and associate of mobsters Lucky Luciano and Meyer Lansky. Zwillman's criminal org ...

– spoke from prison, offering to help return the baby in exchange for money or for legal favors. Specifically, Capone offered assistance in return for being released from prison under the pretense that his assistance would be more effective. This was quickly denied by the authorities.

The morning after the kidnapping, authorities notified President

The morning after the kidnapping, authorities notified President Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

of the crime. At that time, kidnapping was classified as a state crime and the case did not seem to have any grounds for federal involvement. Attorney General William D. Mitchell met with Hoover and announced that the whole machinery of the Department of Justice would be set in motion to cooperate with the New Jersey authorities.

The Bureau of Investigation (later the FBI) was authorized to investigate the case, while the United States Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is the maritime security, search and rescue, and law enforcement service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the country's eight uniformed services. The service is a maritime, military, mu ...

, the U.S. Customs Service, the U.S. Immigration Service and the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia

The Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia (MPDC), more commonly known as the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD), the DC Police, and, colloquially, the DCPD, is the primary law enforcement agency for the District of Columbi ...

were told their services might be required. New Jersey officials announced a $25,000 reward for the safe return of "Little Lindy". The Lindbergh family offered an additional $50,000 reward of their own. At this time, the total reward of $75,000 (approximately ) was a tremendous sum of money, because the nation was in the midst of the Great Depression.

On March 6, a new ransom letter arrived by mail at the Lindbergh home. The letter was postmarked March 4 in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, and it carried the perforated red and blue marks. The ransom had been raised to $70,000. A third ransom note postmarked from Brooklyn, and also including the secret marks, arrived in Breckinridge's mail. The note told the Lindberghs that John Condon should be the intermediary between the Lindberghs and the kidnapper(s), and requested notification in a newspaper that the third note had been received. Instructions specified the size of the box the money should come in, and warned the family not to contact the police.

John Condon

During this time, John F. Condona well-known Bronx personality and retired school teacheroffered $1,000 if the kidnapper would turn the child over to a Catholic priest. Condon received a letter reportedly written by the kidnappers; it authorized Condon to be their intermediary with Lindbergh. Lindbergh accepted the letter as genuine. Following the kidnapper's latest instructions, Condon placed a classified ad in the ''New York American

:''Includes coverage of New York Journal-American and its predecessors New York Journal, The Journal, New York American and New York Evening Journal''

The ''New York Journal-American'' was a daily newspaper published in New York City from 1937 t ...

'' reading: "Money is Ready. Jafsie." Condon then waited for further instructions from the culprits.

A meeting between "Jafsie" and a representative of the group that claimed to be the kidnappers was eventually scheduled for late one evening at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. According to Condon, the man sounded foreign but stayed in the shadows during the conversation, and Condon was thus unable to get a close look at his face. The man said his name was John, and he related his story: He was a "Scandinavian" sailor, part of a gang of three men and two women. The baby was being held on a boat, unharmed, but would be returned only for ransom. When Condon expressed doubt that "John" actually had the baby, he promised some proof: the kidnapper would soon return the baby's sleeping suit. The stranger asked Condon, "... would I burn if the package were dead?" When questioned further, he assured Condon that the baby was alive.

On March 16, Condon received a toddler's sleeping suit by mail, and a seventh ransom note. After Lindbergh identified the sleeping suit, Condon placed a new ad in the ''Home News'': "Money is ready. No cops. No secret service. I come alone, like last time." On April 1 Condon received a letter saying it was time for the ransom to be delivered.

Ransom payment

The ransom was packaged in a wooden box that was custom-made in the hope that it could later be identified. The ransom money included a number ofgold certificate

Gold certificates were issued by the United States Treasury as a form of representative money from 1865 to 1933. While the United States observed a gold standard, the certificates offered a more convenient way to pay in gold than the use of coi ...

s; since gold certificates were about to be withdrawn from circulation, it was hoped greater attention would be drawn to anyone spending them. The bills were not marked but their serial numbers were recorded. Some sources credit this idea to Frank J. Wilson, others to Elmer Lincoln Irey.

On April 2, Condon was given a note by an intermediary, an unknown cab driver. Condon met "John" and told him that they had been able to raise only $50,000. The man accepted the money and gave Condon a note saying that the child was in the care of two innocent women.

Discovery of the body

On May 12, delivery truck driver Orville Wilson and his assistant William Allen pulled to the side of a road about south of the Lindbergh home near the hamlet of Mount Rose in neighboring Hopewell Township. When Allen went into a grove of trees to urinate, he discovered the body of a toddler. The skull was badly fractured and the body decomposed, with evidence of scavenging by animals; there were indications of an attempt at a hasty burial. Gow identified the baby as the missing infant from the overlapping toes of the right foot and a shirt that she had made. It appeared the child had been killed by a blow to the head. Lindbergh insisted on cremation.

In June 1932, officials began to suspect that the crime had been perpetrated by someone the Lindberghs knew. Suspicion fell upon Violet Sharpe, a British household servant at the Morrow home who had given contradictory information regarding her whereabouts on the night of the kidnapping. It was reported that she appeared nervous and suspicious when questioned. She died by suicide on June 10, 1932, by ingesting a silver polish that contained

On May 12, delivery truck driver Orville Wilson and his assistant William Allen pulled to the side of a road about south of the Lindbergh home near the hamlet of Mount Rose in neighboring Hopewell Township. When Allen went into a grove of trees to urinate, he discovered the body of a toddler. The skull was badly fractured and the body decomposed, with evidence of scavenging by animals; there were indications of an attempt at a hasty burial. Gow identified the baby as the missing infant from the overlapping toes of the right foot and a shirt that she had made. It appeared the child had been killed by a blow to the head. Lindbergh insisted on cremation.

In June 1932, officials began to suspect that the crime had been perpetrated by someone the Lindberghs knew. Suspicion fell upon Violet Sharpe, a British household servant at the Morrow home who had given contradictory information regarding her whereabouts on the night of the kidnapping. It was reported that she appeared nervous and suspicious when questioned. She died by suicide on June 10, 1932, by ingesting a silver polish that contained cyanide

Cyanide is a naturally occurring, rapidly acting, toxic chemical that can exist in many different forms.

In chemistry, a cyanide () is a chemical compound that contains a functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of ...

just before being questioned for the fourth time. Her alibi was later confirmed, and police were criticized for heavy-handedness.

Condon was also questioned by police and his home searched, but nothing suggestive was found. Charles Lindbergh stood by Condon during this time.

John Condon's unofficial investigation

After the discovery of the body, Condon remained unofficially involved in the case. To the public, he had become a suspect and in some circles was vilified. For the next two years, he visited police departments and pledged to find "Cemetery John". Condon's actions regarding the case were increasingly flamboyant. On one occasion, while riding a city bus, Condon claimed that he saw a suspect on the street and, announcing his secret identity, ordered the bus to stop. The startled driver complied and Condon darted from the bus, although his target eluded him. Condon's actions were also criticized as exploitive when he agreed to appear in avaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic composition ...

act regarding the kidnapping. ''Liberty'' magazine published a serialized account of Condon's involvement in the Lindbergh kidnapping under the title "Jafsie Tells All".

Tracking the ransom money

The investigators who were working on the case were soon at a standstill. There were no developments and little evidence of any sort, so police turned their attention to tracking the ransom payments. A pamphlet was prepared with the serial numbers on the ransom bills, and 250,000 copies were distributed to businesses, mainly in New York City. A few of the ransom bills appeared in scattered locations, some as far away as Chicago and

The investigators who were working on the case were soon at a standstill. There were no developments and little evidence of any sort, so police turned their attention to tracking the ransom payments. A pamphlet was prepared with the serial numbers on the ransom bills, and 250,000 copies were distributed to businesses, mainly in New York City. A few of the ransom bills appeared in scattered locations, some as far away as Chicago and Minneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origins ...

, but those spending the bills were never found.

By a presidential order, all gold certificates were to be exchanged for other bills by May 1, 1933. A few days before the deadline, a man brought $2,980 to a Manhattan bank for exchange; it was later realized the bills were from the ransom. He had given his name as J.J. Faulkner of 537 West 149th Street. No one named Faulkner lived at that address, and a Jane Faulkner who had lived there 20 years earlier denied involvement.

Arrest of Hauptmann

During a thirty-month period, a number of the ransom bills were spent throughout New York City. Detectives realized that many of the bills were being spent along the route of the Lexington Avenue subway, which connected the Bronx with the east side of Manhattan, including the German-Austrian neighborhood of Yorkville. On September 18, 1934, a Manhattan bank teller noticed a gold certificate from the ransom; a New York license plate number (4U-13-41-N.Y) penciled in the bill's margin allowed it to be traced to a nearby gas station. The station manager had written down the license number because his customer was acting "suspicious" and was "possibly a counterfeiter". The license plate belonged to a sedan owned by Richard Hauptmann of 1279 East 222nd Street in the Bronx, an immigrant with a criminal record in Germany. When Hauptmann was arrested, he was carrying a single 20-dollar gold certificate and over $14,000 of the ransom money was found in his garage. Hauptmann was arrested, interrogated, and beaten at least once throughout the following day and night. Hauptmann stated that the money and other items had been left with him by his friend and former business partnerIsidor Fisch

Bruno Richard Hauptmann (November 26, 1899 – April 3, 1936) was a German-born carpenter who was convicted of the abduction and murder of the 20-month-old son of aviator Charles Lindbergh and his wife Anne Morrow Lindbergh. The Lindbergh kidna ...

. Fisch had died on March 29, 1934, shortly after returning to Germany. Hauptmann stated he learned only after Fisch's death that the shoebox that was left with him contained a considerable sum of money. He kept the money because he claimed that it was owed to him from a business deal that he and Fisch had made. Hauptmann consistently denied any connection to the crime or knowledge that the money in his house was from the ransom.

When the police searched Hauptmann's home, they found a considerable amount of additional evidence that linked him to the crime. One item was a notebook that contained a sketch of the construction of a ladder similar to that which was found at the Lindbergh home in March 1932. John Condon's telephone number, along with his address, were discovered written on a closet wall in the house. A key piece of evidence, a section of wood, was discovered in the attic of the home. After being examined by an expert, it was determined to be an exact match to the wood used in the construction of the ladder found at the scene of the crime.

Hauptmann was indicted in the Bronx on September 24, 1934, for extorting the $50,000 ransom from Charles Lindbergh. Two weeks later, on October 8, Hauptmann was indicted in New Jersey for the murder of Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. Two days later, he was surrendered to New Jersey authorities by New York Governor Herbert H. Lehman to face charges directly related to the kidnapping and murder of the child. Hauptmann was moved to the Hunterdon County Jail in Flemington, New Jersey, on October 19.

Trial and execution

Trial

Hauptmann was charged with capital murder. The trial was held at the

Hauptmann was charged with capital murder. The trial was held at the Hunterdon County Courthouse

The Hunterdon County Courthouse is an historic site located in Flemington, New Jersey, Flemington, the county seat of Hunterdon County, New Jersey, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, United States, that is best known as the site of the 1935 "Trial of t ...

in Flemington, New Jersey

Flemington is a borough in and the county seat of Hunterdon County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.Thomas Whitaker Trenchard

Thomas Whitaker Trenchard (December 13, 1863 – July 23, 1942) was an American lawyer and a justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court between 1906 and 1941.

Trenchard was born on December 13, 1863 in Centreton, Pittsgrove Township, Salem County, ...

presided over the trial.

In exchange for rights to publish Hauptmann's story in their newspaper, Edward J. Reilly was hired by the ''New York Daily Mirror

The ''New York Daily Mirror'' was an American morning tabloid newspaper first published on June 24, 1924, in New York City by the William Randolph Hearst organization as a contrast to their mainstream broadsheets, the ''Evening Journal'' and ''N ...

'' to serve as Hauptmann's attorney. David T. Wilentz, Attorney General of New Jersey

The attorney general of New Jersey is a member of the executive cabinet of the state and oversees the Department of Law and Public Safety. The office is appointed by the governor of New Jersey, confirmed by the New Jersey Senate, and term limited ...

, led the prosecution.

Evidence against Hauptmann included $20,000 of the ransom money found in his garage and testimony alleging that his handwriting and spelling were similar to those of the ransom notes. Eight handwriting experts, including Albert S. Osborn

Albert Sherman Osborn is considered the father of the science of questioned document examination in North America.

His seminal book ''Questioned Documents'' was first published in 1910 and later heavily revised as a second edition in 1929. Othe ...

, pointed out similarities between the ransom notes and Hauptmann's writing specimens. The defense called an expert to rebut this evidence, while two others declined to testify; the latter two demanded $500 before looking at the notes and were dismissed when Lloyd Fisher, a member of Hauptmann's legal team, declined. Other experts retained by the defense were never called to testify.

On the basis of the work of Arthur Koehler

Arthur Koehler (1885–1967) was a chief wood technologist at the Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin, and was important in the development of wood forensics in the 1930s through his role in the investigation of the Lindbergh kidnap ...

at the Forest Products Laboratory

The Forest Products Laboratory (FPL) is the national research laboratory of the United States Forest Service, which is part of USDA. Since its opening in 1910, the FPL has provided scientific research on wood, wood products and their commercial us ...

, the State introduced photographs demonstrating that part of the wood from the ladder matched a plank from the floor of Hauptmann's attic: the type of wood, the direction of tree growth, the milling pattern, the inside and outside surface of the wood, and the grain on both sides were identical, and four oddly placed nail holes lined up with nail holes in joists in Hauptmann's attic. Condon's address and telephone number were written in pencil on a closet door in Hauptmann's home, and Hauptmann told police that he had written Condon's address:

A sketch that Wilentz suggested represented a ladder was found in one of Hauptmann's notebooks. Hauptmann said this picture and other sketches therein were the work of a child.

Despite not having an obvious source of earned income, Hauptmann had bought a $400 radio (approximately ) and sent his wife on a trip to Germany.

Hauptmann was identified as the man to whom the ransom money was delivered. Other witnesses testified that it was Hauptmann who had spent some of the Lindbergh gold certificates; that he had been seen in the area of the estate, in East Amwell, New Jersey

East Amwell Township is a township in Hunterdon County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the township's population was 4,013, reflecting a decline of 442 (−9.9%) from the 4,455 counted in the 2000 Census, which ...

, near Hopewell, on the day of the kidnapping; and that he had been absent from work on the day of the ransom payment and had quit his job two days later. Hauptmann never sought another job afterward, yet continued to live comfortably.

When the prosecution rested its case, the defense opened with a lengthy examination of Hauptmann. In his testimony, Hauptmann denied being guilty, insisting that the box of gold certificates had been left in his garage by a friend, Isidor Fisch

Bruno Richard Hauptmann (November 26, 1899 – April 3, 1936) was a German-born carpenter who was convicted of the abduction and murder of the 20-month-old son of aviator Charles Lindbergh and his wife Anne Morrow Lindbergh. The Lindbergh kidna ...

, who had returned to Germany in December 1933 and died there in March 1934. Hauptmann said that he had one day found a shoe box left behind by Fisch, which Hauptmann had stored on the top shelf of his kitchen broom closet, later discovering the money, which he later found to be almost $40,000 (approximately ). Hauptmann said that, because Fisch had owed him about $7,500 in business funds, Hauptmann had kept the money for himself and had lived on it since January 1934.

The defense called Hauptmann's wife, Anna, to corroborate the Fisch story. On cross-examination, she admitted that while she hung her apron every day on a hook higher than the top shelf, she could not remember seeing any shoe box there. Later, rebuttal witnesses testified that Fisch could not have been at the scene of the crime, and that he had no money for medical treatments when he died of tuberculosis. Fisch's landlady testified that he could barely afford the $3.50 weekly rent of his room.

In his closing summation, Reilly argued that the evidence against Hauptmann was entirely circumstantial, because no reliable witness had placed Hauptmann at the scene of the crime, nor were his fingerprints found on the ladder, on the ransom notes, or anywhere in the nursery.

Appeals

Hauptmann was convicted and immediately sentenced to death. His attorneys appealed to theNew Jersey Court of Errors and Appeals Prior to 1947, the structure of the judiciary in New Jersey was extremely complex, including Court of Errors and Appeals in the last resort in all causes.

The Court of Errors and Appeals was the highest court in the U.S. state of New Jersey from ...

, which at the time was the state's highest court; the appeal was argued on June 29, 1935.

New Jersey Governor Harold G. Hoffman secretly visited Hauptmann in his cell on the evening of October 16, accompanied by a stenographer who spoke German fluently. Hoffman urged members of the Court of Errors and Appeals to visit Hauptmann.

In late January 1936, while declaring that he held no position on the guilt or innocence of Hauptmann, Hoffman cited evidence that the crime was not a "one person" job and directed Schwarzkopf to continue a thorough and impartial investigation in an effort to bring all parties involved to justice.

It became known among the press that on March 27, Hoffman was considering a second reprieve of Hauptmann's death sentence and was seeking opinions about whether the governor had the right to issue a second reprieve.

On March 30, 1936, Hauptmann's second and final appeal asking for clemency from the New Jersey Board of Pardons was denied. Hoffman later announced that this decision would be the final legal action in the case, and that he would not grant another reprieve. Nonetheless, there was a postponement, when the Mercer County grand jury, investigating the confession and arrest of Trenton attorney, Paul Wendel, requested a delay from Warden Mark Kimberling. This, the final stay, ended when the Mercer County prosecutor informed Kimberling that the grand jury had adjourned after voting to end its investigation without charging Wendel.

Execution

Hauptmann turned down a large offer from a Hearst newspaper for a confession and refused a last-minute offer to commute his sentence from the death penalty to life without parole in exchange for a confession. He waselectrocuted

Electrocution is death or severe injury caused by electric shock from electric current passing through the body. The word is derived from "electro" and "execution", but it is also used for accidental death.

The term "electrocution" was coined ...

on April 3, 1936.

After his death, some reporters and independent investigators came up with numerous questions about the way in which the investigation had been run and the fairness of the trial, including witness tampering and planted evidence. Twice in the 1980s, Anna Hauptmann sued the state of New Jersey for the unjust execution

Wrongful execution is a miscarriage of justice occurring when an innocent person is put to death by capital punishment. Cases of wrongful execution are cited as an argument by opponents of capital punishment, while proponents say that the argum ...

of her husband. The suits were dismissed due to prosecutorial immunity In United States law, absolute immunity is a type of sovereign immunity for government officials that confers complete immunity from criminal prosecution and suits for damages, so long as officials are acting within the scope of their duties. The S ...

and because the statute of limitations

A statute of limitations, known in civil law systems as a prescriptive period, is a law passed by a legislative body to set the maximum time after an event within which legal proceedings may be initiated. ("Time for commencing proceedings") In ...

had run out. She continued fighting to clear his name until her death, at age 95, in 1994.

Alternative theories

A number of books have asserted Hauptmann's innocence, generally highlighting inadequate police work at the crime scene, Lindbergh's interference in the investigation, the ineffectiveness of Hauptmann's counsel, and weaknesses in the witnesses and physical evidence.Ludovic Kennedy

Sir Ludovic Henry Coverley Kennedy (3 November 191918 October 2009) was a Scottish journalist, broadcaster, humanist and author best known for re-examining cases such as the Lindbergh kidnapping and the murder convictions of Timothy Evans an ...

, in particular, questioned much of the evidence, such as the origin of the ladder and the testimony of many of the witnesses.

According to author Lloyd Gardner, a fingerprint expert, Erastus Mead Hudson, applied the then-rare silver nitrate fingerprint process to the ladder and did not find Hauptmann's fingerprints, even in places that the maker of the ladder must have touched. According to Gardner, officials refused to consider this expert's findings, and the ladder was then washed of all fingerprints.

Jim Fisher, a former FBI agent and professor at Edinboro University of Pennsylvania, has written two books, ''The Lindbergh Case'' (1987) and ''The Ghosts of Hopewell'' (1999), addressing what he calls a "revision movement" regarding the case. He summarizes:

Another book, ''Hauptmann's Ladder: A step-by-step analysis of the Lindbergh kidnapping'' by Richard T. Cahill Jr., concludes that Hauptmann was guilty but questions whether he should have been executed.

According to John Reisinger in ''Master Detective'', New Jersey detective Ellis Parker conducted an independent investigation in 1936 and obtained a signed confession from former Trenton attorney Paul Wendel, creating a sensation and resulting in a temporary stay of execution for Hauptmann. The case against Wendel collapsed, however, when he insisted his confession had been coerced.

Another theory is Lindbergh accidentally killed his son in a prank gone wrong. In ''Crime of the Century: The Lindbergh Kidnapping Hoax'', criminal defense attorney Gregory Ahlgren posits Lindbergh climbed a ladder and brought his son out of a window, but dropped the child, killing him, so hid the body in the woods, then covered up the crime by blaming Hauptmann.

Robert Zorn's 2012 book '' Cemetery John'' proposes that Hauptmann was part of a conspiracy with two other German-born men, John and Walter Knoll. Zorn's father, economist Eugene Zorn, believed that as a teenager he had witnessed the conspiracy being discussed.

In popular culture

In novels

* 1934: Agatha Christie was inspired by circumstances of the case when she described the kidnapping of baby girl Daisy Armstrong in herHercule Poirot

Hercule Poirot (, ) is a fictional Belgian detective created by British writer Agatha Christie. Poirot is one of Christie's most famous and long-running characters, appearing in 33 novels, two plays ('' Black Coffee'' and ''Alibi''), and more ...

novel ''Murder on the Orient Express

''Murder on the Orient Express'' is a work of detective fiction by English writer Agatha Christie featuring the Belgian detective Hercule Poirot. It was first published in the United Kingdom by the Collins Crime Club on 1 January 1934. In the U ...

''.

* 1981: The kidnapping and its aftermath served as the inspiration for Maurice Sendak's book ''Outside Over There

''Outside Over There'' is a picture book for children written and illustrated by Maurice Sendak. It concerns a young girl named Ida, who must rescue her baby sister after the child has been stolen by goblins. ''Outside Over There'' has been des ...

''.

* 1993: In the novel '' Along Came a Spider'' by James Patterson

James Brendan Patterson (born March 22, 1947) is an American author. Among his works are the '' Alex Cross'', '' Michael Bennett'', '' Women's Murder Club'', '' Maximum Ride'', '' Daniel X'', '' NYPD Red'', '' Witch & Wizard'', and ''Private'' ...

and the film

The Film is a 2005 Indian thriller film directed by Junaid Memon also produced along with Amitabh Bhattacharya. The film stars Mahima Chaudhry, Khalid Siddiqui, Ananya Khare, Chahat Khanna, Ravi Gossain, Vaibhav Jhalani and Vivek Madan in lea ...

based on the novel, a character takes inspiration from the Lindbergh kidnapping for his crime.

* 2013: ''The Aviator's Wife'' by Melanie Benjamin is a work of historical fiction told from the perspective of Anne Morrow Lindbergh.

In music

* May 1932: Just one day after the Lindbergh baby was discovered murdered, the prolific country recording artist Bob Miller (under the pseudonym Bob Ferguson) recorded two songs for Columbia on May 13, 1932, commemorating the event. The songs were released on Columbia 15759-D with the titles "Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr." and "There's a New Star Up in Heaven (Baby Lindy Is Up There)".In film

* 1996: '' Crime of the Century'' * 2011: The kidnapping, investigation and trial are featured in ''J. Edgar

''J. Edgar'' is a 2011 American biographical drama film based on the career of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, directed, produced and scored by Clint Eastwood. Written by Dustin Lance Black, the film focuses on Hoover's life from the 1919 Palme ...

'', the biopic of J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law-enforcement administrator who served as the final Director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) and the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Pre ...

, Director of the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

(directed by Clint Eastwood and starring Leonardo DiCaprio).

In television

* 1976: ''The Lindbergh Kidnapping Case

''The Lindbergh Kidnapping Case'' is a 1976 American television film dramatization of the Lindbergh kidnapping, directed by Buzz Kulik and starting Cliff DeYoung, Anthony Hopkins, Martin Balsam, Joseph Cotten, and Walter Pidgeon. It first aired ...

''

* American Horror Story

''American Horror Story'' is an American anthology horror television series created by Ryan Murphy and Brad Falchuk for the cable network FX. The first installment in the '' American Story'' media franchise, each season is conceived as a ...

season 1

See also

* List of kidnappings *List of solved missing person cases

Lists of solved missing person cases include:

* List of solved missing person cases: pre-2000

* List of solved missing person cases: post-2000

See also

* List of kidnappings

* List of murder convictions without a body

* List of people who di ...

Explanatory notes

General and cited references

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Citations

External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Lindbergh 1930s missing person cases 1932 crimes in the United States 1932 in New Jersey 1932 murders in the United States 20th-century American trials Charles Lindbergh Child abduction in the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation Formerly missing people Incidents of violence against boys Infanticide Kidnappings in the United States Male murder victims March 1932 events Missing person cases in New Jersey Murder in New Jersey Violence against children