Cetacean stranding on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cetacean stranding, commonly known as beaching, is a phenomenon in which

Cetacean stranding, commonly known as beaching, is a phenomenon in which

Every year, up to 2,000 animals beach themselves.

Although the majority of strandings result in death, they pose no threat to any species as a whole. Only about ten

Every year, up to 2,000 animals beach themselves.

Although the majority of strandings result in death, they pose no threat to any species as a whole. Only about ten

Some strandings may be caused by larger cetaceans following

Some strandings may be caused by larger cetaceans following

In Argentina, killer whales are known to hunt on the shore by intentionally beaching themselves and then lunging at nearby seals before riding the next wave safely back into deeper waters. This was first observed in the early 1970s, then hundreds times more since within this pod. This behavior seems to be taught from one generation to the next, evidenced by older individuals nudging juveniles towards the shore, and can sometimes also be a play activity.

In Argentina, killer whales are known to hunt on the shore by intentionally beaching themselves and then lunging at nearby seals before riding the next wave safely back into deeper waters. This was first observed in the early 1970s, then hundreds times more since within this pod. This behavior seems to be taught from one generation to the next, evidenced by older individuals nudging juveniles towards the shore, and can sometimes also be a play activity.

There is evidence that

There is evidence that

If a whale is beached near an inhabited locality, the rotting carcass can pose a nuisance as well as a health risk. Such very large carcasses are difficult to move. The whales are often towed back out to sea away from shipping lanes, allowing them to decompose naturally, or they are towed out to sea and blown up with explosives. Government-sanctioned explosions have occurred in South Africa, Iceland, Australia and United States. If the carcass is older, it is buried.

In New Zealand, which is the site of many whale strandings, treaties with the indigenous

If a whale is beached near an inhabited locality, the rotting carcass can pose a nuisance as well as a health risk. Such very large carcasses are difficult to move. The whales are often towed back out to sea away from shipping lanes, allowing them to decompose naturally, or they are towed out to sea and blown up with explosives. Government-sanctioned explosions have occurred in South Africa, Iceland, Australia and United States. If the carcass is older, it is buried.

In New Zealand, which is the site of many whale strandings, treaties with the indigenous

Protect Marine Mammals from Ocean Noise

(

Cetacean stranding, commonly known as beaching, is a phenomenon in which

Cetacean stranding, commonly known as beaching, is a phenomenon in which whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully aquatic placental marine mammals. As an informal and colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea, i.e. all cetaceans apart from dolphins and ...

s and dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal within the infraorder Cetacea. Dolphin species belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontoporiidae (the ...

s strand themselves on land, usually on a beach

A beach is a landform alongside a body of water which consists of loose particles. The particles composing a beach are typically made from rock, such as sand, gravel, shingle, pebbles, etc., or biological sources, such as mollusc shel ...

. Beached whales often die due to dehydration

In physiology, dehydration is a lack of total body water, with an accompanying disruption of metabolic processes. It occurs when free water loss exceeds free water intake, usually due to exercise, disease, or high environmental temperature. Mil ...

, collapsing under their own weight, or drowning when high tide covers the blowhole. Cetacea

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively carnivorous diet. They propel them ...

n stranding has occurred since before recorded history

Recorded history or written history describes the historical events that have been recorded in a written form or other documented communication which are subsequently evaluated by historians using the historical method. For broader world hist ...

.

Several explanations for why cetaceans strand themselves have been proposed, including changes in water temperatures, peculiarities of whales' echolocation in certain surroundings, and geomagnetic disturbances, but none have so far been universally accepted as a definitive reason for the behavior. However, a link between the mass beaching of beaked whale

Beaked whales (systematic name Ziphiidae) are a family of cetaceans noted as being one of the least known groups of mammals because of their deep-sea habitat and apparent low abundance. Only three or four of the 24 species are reasonably well-k ...

s and use of mid-frequency active sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigation, navigate, measure distances (ranging), communicate with or detect o ...

has been found.

Subsequently, whales that die due to stranding can decay and bloat to the point where they can easily explode, causing gas and their internal organs to fly out.

Species

cetacea

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively carnivorous diet. They propel them ...

n species frequently display mass beachings, with ten more rarely doing so.

All frequently involved species are toothed whale

The toothed whales (also called odontocetes, systematic name Odontoceti) are a parvorder of cetaceans that includes dolphins, porpoises, and all other whales possessing teeth, such as the beaked whales and sperm whales. Seventy-three species of t ...

s (Odontoceti), rather than baleen whale

Baleen whales (systematic name Mysticeti), also known as whalebone whales, are a parvorder of carnivorous marine mammals of the infraorder Cetacea (whales, dolphins and porpoises) which use keratinaceous baleen plates (or "whalebone") in their ...

s (Mysticeti). These species share some characteristics which may explain why they beach.

Body size does not normally affect the frequency, but both the animals' normal habitat and social organization do appear to influence their chances of coming ashore in large numbers. Odontocetes that normally inhabit deep waters and live in large, tightly knit groups are the most susceptible. This includes the sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the sperm whale famil ...

, oceanic dolphins, usually pilot

An aircraft pilot or aviator is a person who controls the flight of an aircraft by operating its directional flight controls. Some other aircrew members, such as navigators or flight engineers, are also considered aviators, because they a ...

and killer whale

The orca or killer whale (''Orcinus orca'') is a toothed whale belonging to the oceanic dolphin family, of which it is the largest member. It is the only extant species in the genus ''Orcinus'' and is recognizable by its black-and-white pa ...

s, and a few beaked whale

Beaked whales (systematic name Ziphiidae) are a family of cetaceans noted as being one of the least known groups of mammals because of their deep-sea habitat and apparent low abundance. Only three or four of the 24 species are reasonably well-k ...

species. The most common species to strand in the United Kingdom is the harbour porpoise

The harbour porpoise (''Phocoena phocoena'') is one of eight extant species of porpoise. It is one of the smallest species of cetacean. As its name implies, it stays close to coastal areas or river estuaries, and as such, is the most familiar ...

; the common dolphin (''Delphinus delphis

The common dolphin (''Delphinus delphis'') is the most abundant cetacean in the world, with a global population of about six million. Despite this fact and its vernacular name, the common dolphin is not thought of as the archetypal dolphin, with ...

'') is second-most common, and after that long-finned pilot whales (''Globicephala melas

The long-finned pilot whale (''Globicephala melas'') is a large species of oceanic dolphin. It shares the genus '' Globicephala'' with the short-finned pilot whale (''Globicephala macrorhynchus''). Long-finned pilot whales are known as such bec ...

'').

Solitary species naturally do not strand en masse. Cetaceans that spend most of their time in shallow, coastal waters almost never mass strand.

Causes

Strandings can be grouped into several types. The most obvious distinction is between single and multiple strandings. Many theories, some of them controversial, have been proposed to explain beaching, but the question remains unresolved. ;Natural deaths at sea: The carcasses of deceased cetaceans are likely to float to the surface at some point; during this time,current

Currents, Current or The Current may refer to:

Science and technology

* Current (fluid), the flow of a liquid or a gas

** Air current, a flow of air

** Ocean current, a current in the ocean

*** Rip current, a kind of water current

** Current (stre ...

s or wind

Wind is the natural movement of air or other gases relative to a planet's surface. Winds occur on a range of scales, from thunderstorm flows lasting tens of minutes, to local breezes generated by heating of land surfaces and lasting a few hou ...

s may carry them to a coast

The coast, also known as the coastline or seashore, is defined as the area where land meets the ocean, or as a line that forms the boundary between the land and the coastline. The Earth has around of coastline. Coasts are important zones in n ...

line. Since thousands of cetaceans die every year, many become stranded posthumously. Most carcasses never reach the coast, and are scavenge

Scavengers are animals that consume Corpse decomposition, dead organisms that have died from causes other than predation or have been killed by other predators. While scavenging generally refers to carnivores feeding on carrion, it is also a h ...

d, or decompose

Decomposition or rot is the process by which dead organic substances are broken down into simpler organic or inorganic matter such as carbon dioxide, water, simple sugars and mineral salts. The process is a part of the nutrient cycle and is ...

enough to sink to the ocean bottom, where the carcass forms the basis of a unique local ecosystem called a ''whale fall

A whale fall occurs when the carcass of a whale has fallen onto the ocean floor at a depth greater than , in the bathyal or abyssal zones. On the sea floor, these carcasses can create complex localized ecosystems that supply sustenance to deep-s ...

''.

;Individual strandings: Single live strandings are often the result of individual illness or injury; in the absence of human intervention these almost always inevitably end in death.

;Multiple strandings: Multiple strandings in one place are rare, and often attract media coverage as well as rescue efforts. The strong social cohesion of toothed whale pods appears to be a key factor in many cases of multiple stranding: If one gets into trouble, its distress calls may prompt the rest of the pod to follow and beach themselves alongside.

Even multiple offshore deaths are unlikely to lead to multiple strandings, since winds and currents are variable, and will scatter a group of corpses.

Environmental

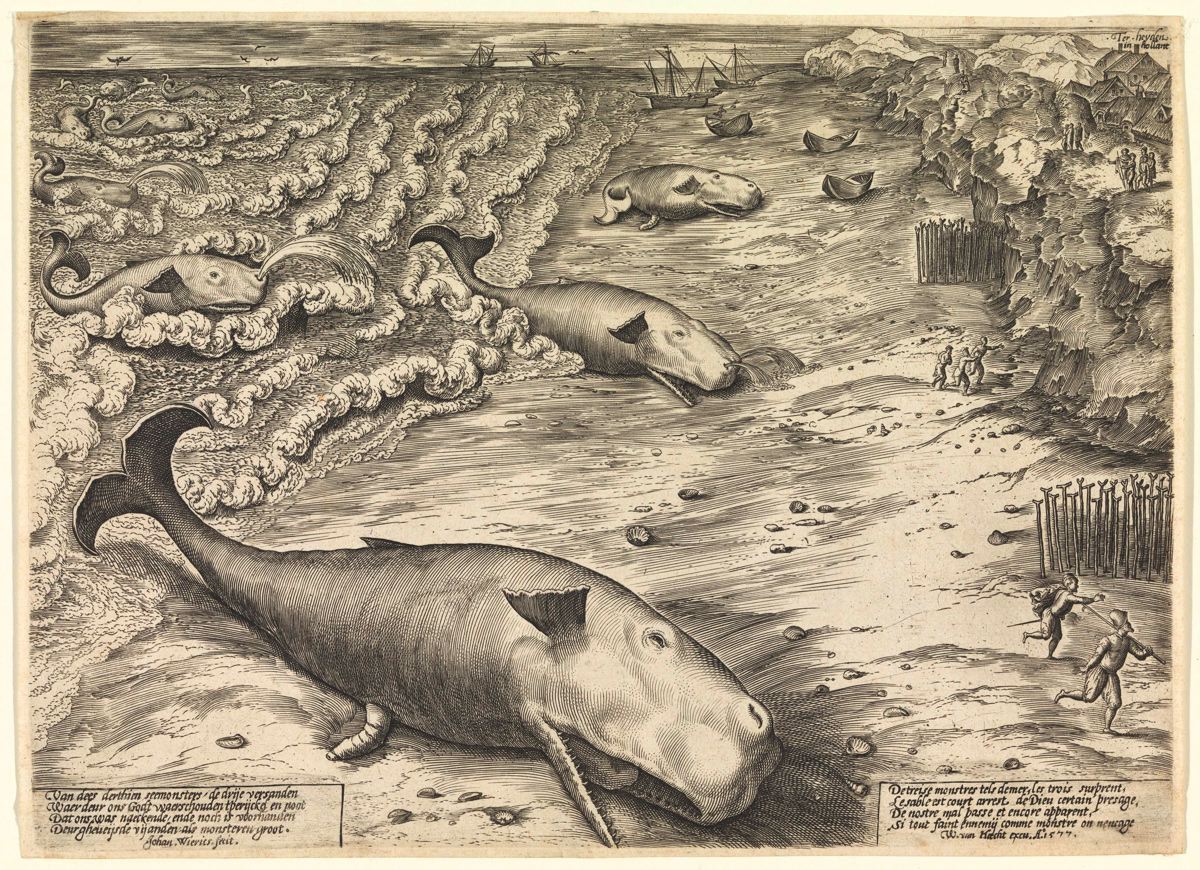

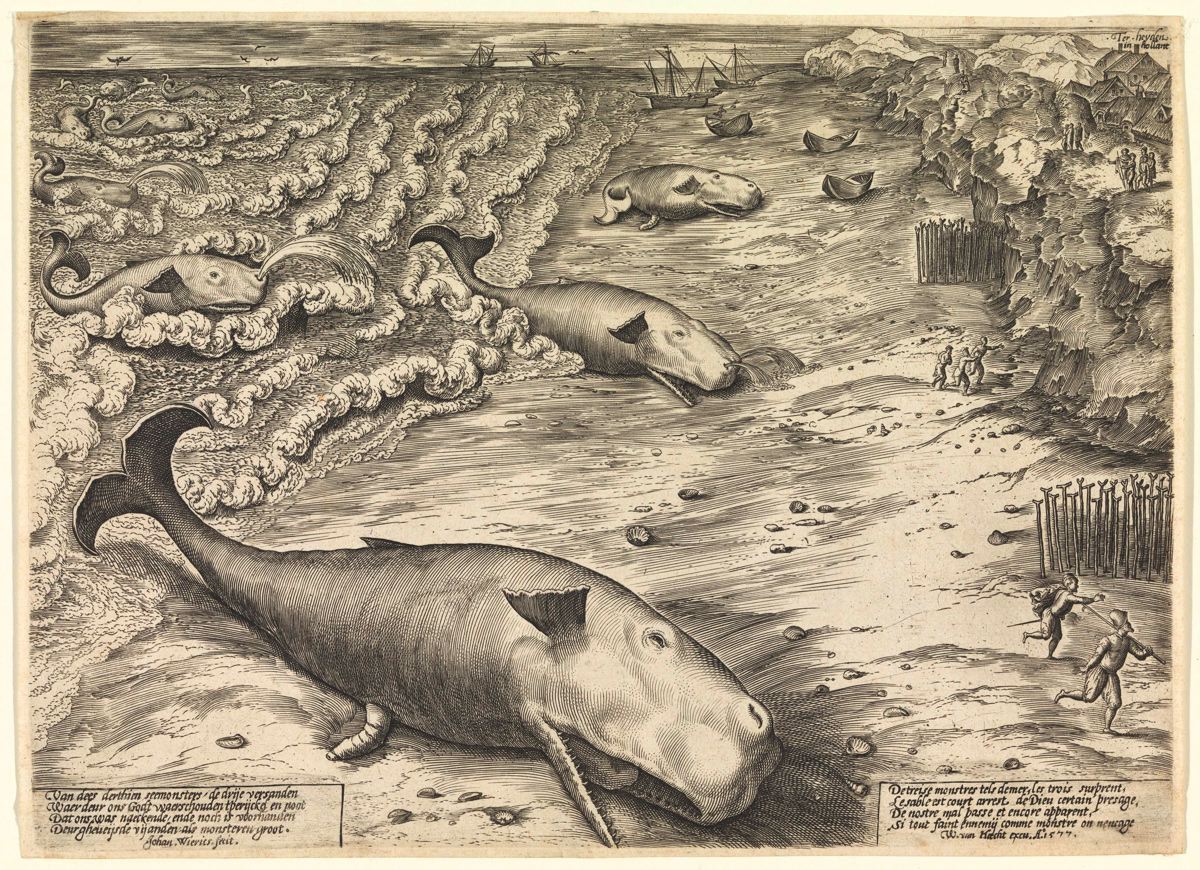

Whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully aquatic placental marine mammals. As an informal and colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea, i.e. all cetaceans apart from dolphins and ...

s have beached throughout human history, with evidence of humans salvaging from stranded sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the sperm whale famil ...

s in southern Spain during the Upper Magdalenian

The Magdalenian cultures (also Madelenian; French: ''Magdalénien'') are later cultures of the Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic in western Europe. They date from around 17,000 to 12,000 years ago. It is named after the type site of La Madele ...

era some 14,000 years before the present. Some strandings can be attributed to natural and environmental factors, such as rough weather, weakness due to old age or infection, difficulty giving birth, hunting too close to shore, or navigation errors.

In 2004, scientists at the University of Tasmania

The University of Tasmania (UTAS) is a public research university, primarily located in Tasmania, Australia. Founded in 1890, it is Australia's fourth oldest university. Christ College, one of the university's residential colleges, first pro ...

linked whale strandings and weather, hypothesizing that when cool Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and other ...

waters rich in squid

True squid are molluscs with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight arms, and two tentacles in the superorder Decapodiformes, though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also called squid despite not strictly fitting t ...

and fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of li ...

flow north, whales follow their prey closer towards land. In some cases predators (such as killer whales) have been known to panic other whales, herding them towards the shoreline.

Their echolocation system can have difficulty picking up very gently-sloping coastlines. This theory accounts for mass beaching hot spots such as Ocean Beach, Tasmania and Geographe Bay

Geographe Bay is in the south-west of Western Australia around 220 km southwest of Perth.

The bay was named in May 1801 by French explorer Nicolas Baudin, after his ship, ''Géographe''. The bay is a wide curve of coastline extending from ...

, Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

where the slope is about half a degree (approximately deep out to sea). The University of Western Australia

The University of Western Australia (UWA) is a public research university in the Australian state of Western Australia. The university's main campus is in Perth, the state capital, with a secondary campus in Albany, Western Australia, Albany an ...

Bioacoustics

Bioacoustics is a cross-disciplinary science that combines biology and acoustics. Usually it refers to the investigation of sound production, dispersion and reception in animals (including humans). This involves neurophysiological and anatomical b ...

group proposes that repeated reflections between the surface and ocean bottom in gently sloping shallow water may attenuate

In physics, attenuation (in some contexts, extinction) is the gradual loss of flux intensity through a medium. For instance, dark glasses attenuate sunlight, lead attenuates X-rays, and water and air attenuate both light and sound at variable a ...

sound so much that the echo is inaudible to the whales.

Stirred up sand as well as long-lived microbubbles formed by rain may further exacerbate the effect.

A 2017 study by scientists from Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

's University of Kiel

Kiel University, officially the Christian-Albrecht University of Kiel, (german: Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, abbreviated CAU, known informally as Christiana Albertina) is a university in the city of Kiel, Germany. It was founded in ...

suggests that large geomagnetic disruptions of the Earth's magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magnetic f ...

, brought on through solar storms, could be another cause for whale beachings.

The authors hypothesize that whales navigate

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation, ...

using the Earth's magnetic field by detecting differences in the field's strength to find their way. The solar storms cause anomalies in the field, which may disturb the whales' ability to navigate, sending them into shallow waters where they get trapped. The study is based on the mass beachings of 29 sperm whales along the coasts of Germany, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, the UK and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

in 2016.

"Follow-me" strandings

Some strandings may be caused by larger cetaceans following

Some strandings may be caused by larger cetaceans following dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal within the infraorder Cetacea. Dolphin species belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontoporiidae (the ...

s and porpoise

Porpoises are a group of fully aquatic marine mammals, all of which are classified under the family Phocoenidae, parvorder Odontoceti (toothed whales). Although similar in appearance to dolphins, they are more closely related to narwhals an ...

s into shallow coastal waters. The larger animals may habituate to following faster-moving dolphins. If they encounter an adverse combination of tidal flow

Tidal is the adjectival form of tide.

Tidal may also refer to:

* ''Tidal'' (album), a 1996 album by Fiona Apple

* Tidal (king), a king involved in the Battle of the Vale of Siddim

* TidalCycles, a live coding environment for music

* Tidal (servic ...

and seabed topography

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as 'seabeds'.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

, the larger species may become trapped.

Sometimes following a dolphin can help lead a whale out of danger: In 2008, a local dolphin was followed out to open water by two pygmy sperm whale

The pygmy sperm whale (''Kogia breviceps'') is one of two extant species in the family Kogiidae in the sperm whale superfamily. They are not often sighted at sea, and most of what is known about them comes from the examination of stranded speci ...

s that had become lost behind a sandbar at Mahia Beach, New Zealand. It may be possible to train dolphins to lead trapped whales out to sea.

Orcas' intentional, temporary strandings

Pods ofkiller whale

The orca or killer whale (''Orcinus orca'') is a toothed whale belonging to the oceanic dolphin family, of which it is the largest member. It is the only extant species in the genus ''Orcinus'' and is recognizable by its black-and-white pa ...

s – predators of dolphins and porpoises – very rarely strand. It might be that killer whales have learned to stay away from shallow waters, and that heading to the shallows offers the smaller animals some protection from predators. However, killer whales in Península Valdés

The Valdes Peninsula (Spanish: ''Península Valdés'') is a peninsula into the Atlantic Ocean in the Biedma Department of north-east Chubut Province, Argentina. Around in size (not taking into account the isthmus of Carlos Ameghino which connects ...

, Argentina, and the Crozet Islands

The Crozet Islands (french: Îles Crozet; or, officially, ''Archipel Crozet'') are a sub-Antarctic archipelago of small islands in the southern Indian Ocean. They form one of the five administrative districts of the French Southern and Antarcti ...

in the Indian Ocean ''have'' learned how to operate in shallow waters, particularly in their pursuit of seals. The killer whales regularly demonstrate their competence by chasing seals up shelving gravel beaches, up to the edge of the water. The pursuing whales are occasionally partially thrust out of the sea by a combination of their own impetus and retreating water, and have to wait for the next wave to re-float them and carry them back to sea.

In Argentina, killer whales are known to hunt on the shore by intentionally beaching themselves and then lunging at nearby seals before riding the next wave safely back into deeper waters. This was first observed in the early 1970s, then hundreds times more since within this pod. This behavior seems to be taught from one generation to the next, evidenced by older individuals nudging juveniles towards the shore, and can sometimes also be a play activity.

In Argentina, killer whales are known to hunt on the shore by intentionally beaching themselves and then lunging at nearby seals before riding the next wave safely back into deeper waters. This was first observed in the early 1970s, then hundreds times more since within this pod. This behavior seems to be taught from one generation to the next, evidenced by older individuals nudging juveniles towards the shore, and can sometimes also be a play activity.

Sonar

active sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances (ranging), communicate with or detect objects on or ...

leads to beaching. On some occasions cetaceans have stranded shortly after military sonar was active in the area, suggesting a link.

Theories describing how sonar may cause whale deaths have also been advanced after necropsies

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any di ...

found internal injuries in stranded cetaceans. In contrast, some who strand themselves due to seemingly natural causes are usually healthy prior to beaching:

Direct injury

The large and rapid pressure changes made by loud sonar can causehemorrhaging

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vag ...

. Evidence emerged after 17 cetaceans were hauled out in the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

in March 2000 following a United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

sonar exercise. The Navy accepted blame agreeing that the dead whales experienced acoustically induced hemorrhages around the ears. The resulting disorientation probably led to the stranding. Ken Balcomb, a cetologist

Cetology (from Greek , ''kētos'', "whale"; and , ''-logia'') or whalelore (also known as whaleology) is the branch of marine mammal science that studies the approximately eighty species of whales, dolphins, and porpoises in the scientific order ...

, specializes in the killer whale

The orca or killer whale (''Orcinus orca'') is a toothed whale belonging to the oceanic dolphin family, of which it is the largest member. It is the only extant species in the genus ''Orcinus'' and is recognizable by its black-and-white pa ...

populations that inhabit the Strait of Juan de Fuca

The Strait of Juan de Fuca (officially named Juan de Fuca Strait in Canada) is a body of water about long that is the Salish Sea's outlet to the Pacific Ocean. The international boundary between Canada and the United States runs down the centre ...

between Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

and Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian Provinces and territories of Canada, province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are o ...

. He investigated these beachings and argues that the powerful sonar pulses resonated with airspaces in the dolphins, tearing tissue around the ears and brain. Apparently not all species are affected by sonar.

Injury at a vulnerable moment

Another means by which sonar could be hurting cetaceans is a form ofdecompression sickness

Decompression sickness (abbreviated DCS; also called divers' disease, the bends, aerobullosis, and caisson disease) is a medical condition caused by dissolved gases emerging from solution as bubbles inside the body tissues during decompressio ...

. This was first raised by necrological examinations of 14 beaked whale

Beaked whales (systematic name Ziphiidae) are a family of cetaceans noted as being one of the least known groups of mammals because of their deep-sea habitat and apparent low abundance. Only three or four of the 24 species are reasonably well-k ...

s stranded in the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Morocc ...

. The stranding happened on 24 September 2002, close to the operating area of Neo Tapon (an international naval exercise) about four hours after the activation of mid-frequency sonar.

The team of scientists found acute tissue damage from gas-bubble lesions, which are indicative of decompression sickness. The precise mechanism of how sonar causes bubble formation is not known. It could be due to cetaceans panicking and surfacing too rapidly in an attempt to escape the sonar pulses. There is also a theoretical basis by which sonar vibrations can cause supersaturated gas to nucleate

In thermodynamics, nucleation is the first step in the formation of either a new thermodynamic phase or structure via self-assembly or self-organization within a substance or mixture. Nucleation is typically defined to be the process that dete ...

, forming bubbles, which are responsible for decompression sickness.

Diving patterns of Cuvier's beaked whales

The overwhelming majority of the cetaceans involved in sonar-associated beachings areCuvier's beaked whale

The Cuvier's beaked whale, goose-beaked whale, or ziphius (''Ziphius cavirostris'') is the most widely distributed of all beaked whales in the family Ziphiidae. It is smaller than most baleen whales yet large among beaked whales. Cuvier's beaked ...

s (''Ziphius cavirostrus''). Individuals of this species strand frequently, but mass strandings are rare.

Cuvier's beaked whale

The Cuvier's beaked whale, goose-beaked whale, or ziphius (''Ziphius cavirostris'') is the most widely distributed of all beaked whales in the family Ziphiidae. It is smaller than most baleen whales yet large among beaked whales. Cuvier's beaked ...

s (''Ziphius cavirostrus'') are an open-ocean species that rarely approach the shore, making them difficult to study in the wild. Prior to the interest raised by the sonar controversy, most of the information about them came from stranded animals. The first to publish research linking beachings with naval activity were Simmonds and Lopez-Jurado in 1991. They noted that over the past decade there had been a number of mass strandings of beaked whales in the Canary Islands, and each time the Spanish Navy

The Spanish Navy or officially, the Armada, is the maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces and one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. The Spanish Navy was responsible for a number of major historic achievements in navigation, ...

was conducting exercises. Conversely, there were no mass strandings at other times. They did not propose a theory for the strandings. Fernández ''et al.'' in a 2013 letter to ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

'', reported that there had been no further mass strandings in that area, following a 2004 ban by the Spanish government on military exercises in that region.

In May 1996, there was another mass stranding in West Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

. At the time, it was noted as "atypical" both because mass strandings of beaked whales are rare, and also because the stranded whales were spread over such a long stretch of coast, with each individual whale spatially separated from the next stranding. At the time of the incident, there was no connection made with active sonar; A. Frantzis, the marine biologist investigating the incident, made the connection to sonar because he discovered a notice to mariners concerning the test. His report was published in March 1998.

Peter Tyack, of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI, acronym pronounced ) is a private, nonprofit research and higher education facility dedicated to the study of marine science and engineering.

Established in 1930 in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, it ...

, has been researching noise's effects on marine mammals since the 1970s. He has led much of the recent research on beaked whales (Cuvier's beaked whale

The Cuvier's beaked whale, goose-beaked whale, or ziphius (''Ziphius cavirostris'') is the most widely distributed of all beaked whales in the family Ziphiidae. It is smaller than most baleen whales yet large among beaked whales. Cuvier's beaked ...

s in particular). Data tags have shown that Cuvier's dive considerably deeper than previously thought, and are in fact the deepest-diving species of marine mammal yet known.

At shallow depths Cuvier's stop vocalizing, either because of fear of predators, or because they don't need vocalization to track each other at shallow depths, where they have light adequate to see each other.

Their surfacing behavior is highly unusual, because they exert considerable physical effort to surface by a controlled ascent, rather than passively floating to the surface as sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the sperm whale famil ...

s do. Every deep dive is followed by three or four shallow dives. The elaborate dive patterns are assumed to be necessary to control the diffusion of gases in the bloodstream. No data show a beaked whale making an uncontrolled ascent, or failing to do successive shallow dives. This behavior suggests that the Cuvier's are in a vulnerable state after a deep dive – presumably on the verge of decompression sickness

Decompression sickness (abbreviated DCS; also called divers' disease, the bends, aerobullosis, and caisson disease) is a medical condition caused by dissolved gases emerging from solution as bubbles inside the body tissues during decompressio ...

– and require time and perhaps the shallower dives to recover.

Summary review

De Quirós ''et al.'' (2019) published a review of evidence on the mass strandings of beaked whale linked to naval exercises where sonar was used. It concluded that the effects of mid-frequency active sonar are strongest on Cuvier's beaked whales but vary among individuals or populations. The review suggested the strength of response of individual animals may depend on whether they had prior exposure to sonar, and that symptoms of decompression sickness have been found in stranded whales that may be a result of such response to sonar. It noted that no more mass strandings had occurred in the Canary Islands once naval exercises where sonar was used were banned, and recommended that the ban be extended to other areas where mass strandings continue to occur.Disposal

If a whale is beached near an inhabited locality, the rotting carcass can pose a nuisance as well as a health risk. Such very large carcasses are difficult to move. The whales are often towed back out to sea away from shipping lanes, allowing them to decompose naturally, or they are towed out to sea and blown up with explosives. Government-sanctioned explosions have occurred in South Africa, Iceland, Australia and United States. If the carcass is older, it is buried.

In New Zealand, which is the site of many whale strandings, treaties with the indigenous

If a whale is beached near an inhabited locality, the rotting carcass can pose a nuisance as well as a health risk. Such very large carcasses are difficult to move. The whales are often towed back out to sea away from shipping lanes, allowing them to decompose naturally, or they are towed out to sea and blown up with explosives. Government-sanctioned explosions have occurred in South Africa, Iceland, Australia and United States. If the carcass is older, it is buried.

In New Zealand, which is the site of many whale strandings, treaties with the indigenous Māori people

The Māori (, ) are the indigenous Polynesian people of mainland New Zealand (). Māori originated with settlers from East Polynesia, who arrived in New Zealand in several waves of canoe voyages between roughly 1320 and 1350. Over several ce ...

allow the tribal gathering and customary (that is, traditional) use of whalebone from any animal which has died as a result of stranding. Whales are regarded as ''taonga

''Taonga'' or ''taoka'' (in South Island Māori) is a Maori-language word that refers to a treasured possession in Māori culture. It lacks a direct translation into English, making its use in the Treaty of Waitangi significant. The current d ...

'' (spiritual treasure), descendants of the ocean god, Tangaroa

Tangaroa (Takaroa in the South Island) is the great of the sea, lakes, rivers, and creatures that live within them, especially fish, in Māori mythology. As Tangaroa-whakamau-tai he exercises control over the tides. He is sometimes depicted a ...

, and are as such held in very high respect. Sites of whale strandings and any whale carcasses from strandings are treated as '' tapu'' sites, that is, they are regarded as sacred ground.

Health risks

A beached whale carcass should not be consumed. In 2002, fourteen Alaskans ate ''muktuk

Muktuk (transliterated in various ways, see below) is a traditional food of the peoples of the Arctic, consisting of whale skin and blubber. It is most often made from the bowhead whale, although the beluga and the narwhal are also used. It is ...

'' (whale blubber) from a beached whale, resulting in eight of them developing botulism

Botulism is a rare and potentially fatal illness caused by a toxin produced by the bacterium ''Clostridium botulinum''. The disease begins with weakness, blurred vision, feeling tired, and trouble speaking. This may then be followed by weaknes ...

, with two of the affected requiring mechanical ventilation

Mechanical ventilation, assisted ventilation or intermittent mandatory ventilation (IMV), is the medical term for using a machine called a ventilator to fully or partially provide artificial ventilation. Mechanical ventilation helps move air ...

. This is a possibility for any meat taken from an unpreserved carcass.

Large strandings

This is a list of large cetacean strandings (200 or more).Others

On June 23, 2015, 337 dead whales were discovered in a remotefjord

In physical geography, a fjord or fiord () is a long, narrow inlet with steep sides or cliffs, created by a glacier. Fjords exist on the coasts of Alaska, Antarctica, British Columbia, Chile, Denmark, Germany, Greenland, the Faroe Islands, Ice ...

in Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and gl ...

, southern Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, the largest stranding of baleen whale

Baleen whales (systematic name Mysticeti), also known as whalebone whales, are a parvorder of carnivorous marine mammals of the infraorder Cetacea (whales, dolphins and porpoises) which use keratinaceous baleen plates (or "whalebone") in their ...

s to date. Three hundred and five bodies and 32 skeletons were identified by aerial and satellite photography between the Gulf of Penas The Gulf of Penas (''Golfo de Penas'' in Spanish, meaning "gulf of distress") is a body of water located south of the Taitao Peninsula, Chile.

Geography

It is open to the westerly storms of the Pacific Ocean, but it affords entrance to several nat ...

and Puerto Natales

Puerto Natales is a city in Chilean Patagonia. It is the capital of both the commune of Natales and the province of Última Esperanza, one of the four provinces that make up the Magallanes and Antartica Chilena Region in the southernmost part ...

, near the southern tip of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

. They may have been sei whale

The sei whale ( , ; ''Balaenoptera borealis'') is a baleen whale, the third-largest rorqual after the blue whale and the fin whale. It inhabits most oceans and adjoining seas, and prefers deep offshore waters. It avoids polar and tropical ...

s. This is one of only two or three such baleen mass stranding events in the last hundred years. It is highly unusual for baleens to strand other than singly, and the Patagonia baleen strandings are tentatively attributed to an unusual cause such as ingestion of poisonous algae.

In November 2018, over 140 whales were witnessed stranded on a remote beach in New Zealand and had to be euthanised because of their declining health condition. In July 2019, nearly 50 long-finned pilot whales were found stranded on Snaefellsnes Peninsula in Iceland. However, they were already dead when spotted.

On the evening of November 2, 2020, over 100 short-finned pilot whales were stranded on the Panadura

Panadura ( si, පානදුර, translit=Pānadura; ta, பாணந்துறை, translit=Pāṇantuṟai) is a city in Kalutara District, Western Province in Sri Lanka. It is located approximately south of Colombo and is surrounded on ...

Beach in western coast of Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

. Although four deaths were reported, all other whales were rescued.

See also

* Cetacean strandings in Ghana * Cetacean strandings in Tasmania *Dolphin drive hunting

Dolphin drive hunting, also called dolphin drive fishing, is a method of hunting dolphins and occasionally other small cetaceans by driving them together with boats and then usually into a bay or onto a beach. Their escape is prevented by closing ...

, a technique which herds small cetaceans towards the shore for slaughter

*Drift whale

A drift whale is a cetacean mammal that has died at sea and floated into shore. This is in contrast to a beached or stranded whale, which reaches land alive and may die there or regain safety in the ocean. Most cetaceans that die, from natural ...

* Marine Mammal Stranding Center – New Jersey, United States

*Saint-Clément-des-Baleines

Saint-Clément-des-Baleines () is a commune on Île de Ré, a coastal island in the French department of Charente-Maritime, located in the region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine (formerly Poitou-Charentes).

Population

Geography

This commune has no harb ...

– A coastal area on French island Île de Ré

Île de Ré (; variously spelled Rhé or Rhéa; Poitevin: ''ile de Rét''; en, Isle of Ré, ) is an island off the Atlantic coast of France near La Rochelle, Charente-Maritime, on the northern side of the Pertuis d'Antioche strait.

Its highe ...

named after mass strandings of whales

*Golden Bay Golden Bay may refer to:

* Golden Bay / Mohua, a bay at the northern end of New Zealand's South Island

* Golden Bay (Malta), a bay and beach on the coastline of Malta

* Golden Bay High School

Golden Bay High School is a secondary school

A s ...

, New Zealand – A renowned area for pilot whale mass strandings on Farewell Spit

Farewell Spit ( mi, Onetahua) is a narrow sand spit at the northern end of the Golden Bay, South Island of New Zealand. It runs eastwards from Cape Farewell, the island's northernmost point. Farewell Spit is a legally protected Nature Reserve ...

in Cook Strait

Cook Strait ( mi, Te Moana-o-Raukawa) separates the North and South Islands of New Zealand. The strait connects the Tasman Sea on the northwest with the South Pacific Ocean on the southeast. It is wide at its narrowest point,McLintock, A H, ...

*Whaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industry ...

References

*External links

Protect Marine Mammals from Ocean Noise

(

Natural Resources Defense Council

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) is a United States-based 501(c)(3) non-profit international environmental advocacy group, with its headquarters in New York City and offices in Washington D.C., San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Bo ...

)

{{hydroacoustics

Whales

Animal death

Cetaceans