Causes of the Polish–Soviet War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

During the  In the winter of 1918–19 the recently established Russian Soviet Republic had already undertaken a " Westward Offensive", leading to the establishment of

In the winter of 1918–19 the recently established Russian Soviet Republic had already undertaken a " Westward Offensive", leading to the establishment of  As 1919 progressed, Soviet forces conquered Kiev. In early 1920, Poland formed an alliance with the

As 1919 progressed, Soviet forces conquered Kiev. In early 1920, Poland formed an alliance with the

Google Print, p.2

/ref> The

Google Print, p.75

/ref> All of those engagements – with the sole exception of the Polish-Soviet war – would be short-lived border conflicts. The Polish–Soviet war likely happened more by accident than design, as it is unlikely that anyone in Soviet Russia or in the new Second Republic of Poland would have deliberately planned a major foreign war. Davies, Norman, ''White Eagle, Red Star: the Polish-Soviet War, 1919–20'', Pimlico, 2003, . (First edition: New York, St. Martin's Press, inc., 1972.) Page 22 Norman Davies, ''

Google Print, p.292

/ref> Poland, its territory a major frontline of the First World War, was unstable politically; it had just won the difficult conflict with the West Ukrainian National Republic and was already engaged in new conflicts with Germany (the

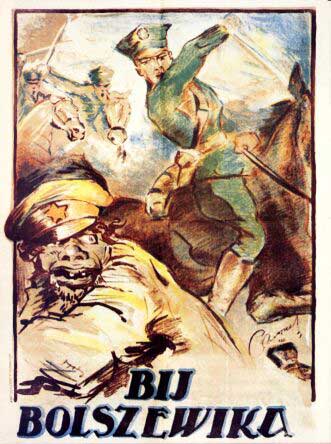

Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (Polish–Bolshevik War, Polish–Soviet War, Polish–Russian War 1919–1921)

* russian: Советско-польская война (''Sovetsko-polskaya voyna'', Soviet-Polish War), Польский фронт (' ...

of 1919–1921, Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

and its client state, Soviet Ukraine

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

, were in combat with the re-established Second Polish Republic and the newly established Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

. Both sides aimed to secure territory in the often disputed areas of the Kresy

Eastern Borderlands ( pl, Kresy Wschodnie) or simply Borderlands ( pl, Kresy, ) was a term coined for the eastern part of the Second Polish Republic during the History of Poland (1918–1939), interwar period (1918–1939). Largely agricultural ...

(present-day western Ukraine

Western Ukraine or West Ukraine ( uk, Західна Україна, Zakhidna Ukraina or , ) is the territory of Ukraine linked to the former Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, which was part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Austria ...

and western Belarus

Western Belorussia or Western Belarus ( be, Заходняя Беларусь, translit=Zachodniaja Bielaruś; pl, Zachodnia Białoruś; russian: Западная Белоруссия, translit=Zapadnaya Belorussiya) is a historical region of mod ...

), in the context of the fluidity of borders in Central and Eastern Europe in the aftermath of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and the breakdown of the Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen, see Austrian nationality law

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example: ...

, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, and Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

Empires. The first clashes between the two sides occurred in February 1919, but full-scale war did not break out until the following year. Especially at first, neither Soviet Russia, embroiled in the Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

, nor Poland, still in the early stages of state re-building, were in a position to formulate and pursue clear and consistent war aims.

In the winter of 1918–19 the recently established Russian Soviet Republic had already undertaken a " Westward Offensive", leading to the establishment of

In the winter of 1918–19 the recently established Russian Soviet Republic had already undertaken a " Westward Offensive", leading to the establishment of Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

client republics in Latvia, Lithuania and Byelorussia. The overarching aim of Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

and Lev Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian M ...

was to spread the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

revolution into Germany and other parts of Europe, while realising their limited capacity to engage in large-scale conflict in Europe. The Soviets built up forces positioned for an attack on Poland, although officially denying that an invasion was planned.

For their part, the Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in C ...

aimed to secure their independence, contain any resurgence of the Russian or German Empires, and reclaim areas in the east that had ethnic Polish populations as per the historical Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ru ...

borders that existed prior to the Partitions of Poland. An ambitious plan formulated by Polish head of state Józef Piłsudski

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Naczelnik państwa, Chief of State (1918–1922) and Marshal of Poland, First Marshal of Second Polish Republic, Poland (from 1920). He was ...

aimed to create a wide "Intermarium

Intermarium ( pl, Międzymorze, ) was a post-World War I geopolitical plan conceived by Józef Piłsudski to unite former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth lands within a single polity. The plan went through several iterations, some of which antic ...

" (''Międzymorze'') federation of independent states to the west of Russia, of which Poland would be the leading member. Limiting Russian control of Ukraine was essential to this plan, and Poland was already at war with Ukrainian forces over Eastern Galicia

Eastern Galicia ( uk, Східна Галичина, Skhidna Galychyna, pl, Galicja Wschodnia, german: Ostgalizien) is a geographical region in Western Ukraine (present day oblasts of Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil), having also essential h ...

.

As 1919 progressed, Soviet forces conquered Kiev. In early 1920, Poland formed an alliance with the

As 1919 progressed, Soviet forces conquered Kiev. In early 1920, Poland formed an alliance with the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

, which had lost much of its territory to the Russian Bolsheviks. Both Polish and Soviet forces in the theatre were rapidly increased, and full-scale war began with Poland's Kiev offensive into Soviet-controlled Ukraine.

The prehistory

The territory, where this conflict broke out, was a part of the medievalKievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas of ...

, and after the disintegration of this united Ruthenian state (in the middle of the 12th century) belonged to the Ruthenian princedoms of Halych-Volhynia, Polotsk

Polotsk (russian: По́лоцк; be, По́лацк, translit=Polatsk (BGN/PCGN), Polack (official transliteration); lt, Polockas; pl, Połock) is a historical city in Belarus, situated on the Dvina River. It is the center of the Polotsk Dist ...

, Lutsk

Lutsk ( uk, Луцьк, translit=Lutsk}, ; pl, Łuck ; yi, לוצק, Lutzk) is a city on the Styr River in northwestern Ukraine. It is the administrative center of the Volyn Oblast (province) and the administrative center of the surrounding Lu ...

, Terebovlia

Terebovlia ( uk, Теребовля, pl, Trembowla, yi, טרעבעוולע, Trembovla) is a small city in Ternopil Raion, Ternopil Oblast (province) of western Ukraine. It is an ancient settlement that traces its roots to the settlement of Tere ...

, Turov-Pinsk etc. The majority of these principalities have been ruined during the Tatar–Mongol invasion in the middle of the 13th century. Some territories in the Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and ...

region and Black Sea Coast for long years lost Ruthenian settled population and became the so-called ''Wild Steppe'' (i.e., territory of the Pereyaslavl). After the Tatar–Mongol invasion these territories become an object of expansion of the Polish kingdom and the Lithuanian princedom. For example, in the first half of 14th century Kiev, the Dniepr region, also the region between the rivers Pripyat

Pripyat ( ; russian: При́пять), also known as Prypiat ( uk, При́пʼять, , ), is an abandoned city in northern Ukraine, located near the border with Belarus. Named after the nearby river, Pripyat, it was founded on 4 February 1 ...

and West Dvina were captured by Lithuania, and in 1352 the Halych-Volhynia princedom was divided by Poland and Lithuania. In 1569, according to the Lublin Union, the majority of the Ruthenian territories possessed by Lithuania, passed to the Polish crown

The Crown of the Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Korona Królestwa Polskiego; Latin: ''Corona Regni Poloniae''), known also as the Polish Crown, is the common name for the historic Late Middle Ages territorial possessions of the King of Poland, incl ...

. The serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which deve ...

and Catholicism extended in these territories. The local aristocracy was incorporated into the Polish aristocracy. Cultural, language and religious break between the supreme and lowest layers of a society arose.

The combination of social, language, religious and cultural oppressions had led to destructive popular uprisings of the middle of 17th century, which the Polish–Lithuanian state could not recover from. In many territories incorporated into the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

in 1772–1795 after the partitions, the domination of the Polish aristocracy was kept, in the territories incorporated into the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the domination of the Polish aristocracy has been added with active planting of German language and culture. During the First World War Austro-Hungarian authorities undertook reprisals against Russia-oriented people of the Eastern Galicia

Eastern Galicia ( uk, Східна Галичина, Skhidna Galychyna, pl, Galicja Wschodnia, german: Ostgalizien) is a geographical region in Western Ukraine (present day oblasts of Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil), having also essential h ...

and the Polish left-nationalist movement led by Piłsudski got the support of the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

for struggle against Russia. In the consequence of the revolution in Russia and the fall of Hohenzollern and Habsburg empires in the end of World War I Poland regained independence. The Polish leaders decided to retrieve as many of the territories that were parts of the Polish–Lithuanian state in 1772 as possible.

The situation

In the aftermath of World War I, the map of Central and Eastern Europe had drastically changed. Thomas Grant Fraser, Seamus Dunn,Otto von Habsburg

Otto von Habsburg (german: Franz Joseph Otto Robert Maria Anton Karl Max Heinrich Sixtus Xaver Felix Renatus Ludwig Gaetan Pius Ignatius, hu, Ferenc József Ottó Róbert Mária Antal Károly Max Heinrich Sixtus Xaver Felix Renatus Lajos Gaetan ...

, ''Europe and Ethnicity: the First World War and contemporary ethnic conflict'', Routledge, 1996, Google Print, p.2

/ref> The

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russia's ...

(March 3, 1918), by which Russia had lost to Imperial Germany

The German Empire (), Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditar ...

all the European lands that Russia had seized in the previous two centuries, was rejected by the Bolshevik government in November 1918, following armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

, the surrender of Germany and her allies, and the end of World War I.

Germany, however, had not been keen to see Russia grow strong again and—exploiting her control of those territories, had quickly granted limited independence as buffer state

A buffer state is a country geographically lying between two rival or potentially hostile great powers. Its existence can sometimes be thought to prevent conflict between them. A buffer state is sometimes a mutually agreed upon area lying between ...

s to Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

, Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

and Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

. As Germany's defeat rendered her plans for the creation of those Mitteleuropa

(), meaning Middle Europe, is one of the German terms for Central Europe. The term has acquired diverse cultural, political and historical connotations. University of Warsaw, Johnson, Lonnie (1996) ''Central Europe: Enemies, Neighbors, Friends'p ...

puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

s obsolete, and as Russia sank into the depths of the Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

, the newly emergent countries saw a chance for real independence and were not prepared to easily relinquish this rare gift of fate. At the same time, Russia saw these territories as rebellious Russian provinces but was unable to react swiftly, as it was weakened and in the process of transforming herself into the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

through the Russian Revolution and Russian Civil War that had begun in 1917.

With the success of the Greater Poland uprising in 1918, Poland had re-established its statehood for the first time since the 1795 partition and seen the end of a 123 years of rule by three imperial neighbors: Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, and Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

. The country, reborn as a Second Polish Republic, proceeded to carve out its borders from the territories of its former partitioners. The Western Powers

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

, in delineating the new European borders after the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, had done so in a way unfavorable to Poland. Her western borders cut her off from the coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

-basin and industrial regions of Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

, leading to the Silesian Uprisings

The Silesian Uprisings (german: Aufstände in Oberschlesien, Polenaufstände, links=no; pl, Powstania śląskie, links=no) were a series of three uprisings from August 1919 to July 1921 in Upper Silesia, which was part of the Weimar Republic ...

of 1919–1921. The eastern Curzon line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by The 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston, the British Foreign Secretary, to ...

left millions of Poles, living east of the Bug River

uk, Західний Буг be, Захо́дні Буг

, name_etymology =

, image = Wyszkow_Bug.jpg

, image_size = 250

, image_caption = Bug River in the vicinity of Wyszków, Poland

, map = Vi ...

, stranded inside Russia's borders.

Poland was not alone in its newfound opportunities and troubles. Most if not all of the newly independent neighbours began fighting over borders: Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

fought with Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

over Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

, Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

with Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

over Rijeka, Poland with Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

over Cieszyn Silesia

Cieszyn Silesia, Těšín Silesia or Teschen Silesia ( pl, Śląsk Cieszyński ; cs, Těšínské Slezsko or ; german: Teschener Schlesien or ) is a historical region in south-eastern Silesia, centered on the towns of Cieszyn and Český T� ...

, with Germany over Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

and with Ukrainians over Eastern Galicia

Eastern Galicia ( uk, Східна Галичина, Skhidna Galychyna, pl, Galicja Wschodnia, german: Ostgalizien) is a geographical region in Western Ukraine (present day oblasts of Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil), having also essential h ...

(Galician War). Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, Українці, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian. The majority of Ukrainians are Eastern Ort ...

, Belarusians, Lithuanians, Estonians

Estonians or Estonian people ( et, eestlased) are a Finnic ethnic group native to Estonia who speak the Estonian language.

The Estonian language is spoken as the first language by the vast majority of Estonians; it is closely related to oth ...

and Latvians

Latvians ( lv, latvieši) are a Baltic ethnic group and nation native to Latvia and the immediate geographical region, the Baltics. They are occasionally also referred to as Letts, especially in older bibliography. Latvians share a common La ...

fought against themselves and against the Russians, who were just as divided. Davies, Norman, ''White Eagle, Red Star: the Polish-Soviet War, 1919–20'', Pimlico, 2003, . (First edition: New York, St. Martin's Press, inc., 1972.) Page 21.

Spreading communist influences resulted in communist revolutions in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

, Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

, Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

and Prešov. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

commented: "The war of giants has ended, the wars of the pygmies begin." Adrian Hyde-Price, ''Germany and European Order'', Manchester University Press, 2001,Google Print, p.75

/ref> All of those engagements – with the sole exception of the Polish-Soviet war – would be short-lived border conflicts. The Polish–Soviet war likely happened more by accident than design, as it is unlikely that anyone in Soviet Russia or in the new Second Republic of Poland would have deliberately planned a major foreign war. Davies, Norman, ''White Eagle, Red Star: the Polish-Soviet War, 1919–20'', Pimlico, 2003, . (First edition: New York, St. Martin's Press, inc., 1972.) Page 22 Norman Davies, ''

God's Playground

''God's Playground: A History of Poland'' is a history book in two volumes written by Norman Davies, covering a 1000-year history of Poland. Volume 1: ''The origins to 1795'', and Volume 2: ''1795 to the present'' first appeared as the Oxford Cl ...

. Vol. 2: 1795 to the Present''. Columbia University Press, 2005 982

Year 982 ( CMLXXXII) was a common year starting on Sunday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place Europe

* Summer – Emperor Otto II (the Red) assembles an imperial expeditionary force at Tar ...

Google Print, p.292

/ref> Poland, its territory a major frontline of the First World War, was unstable politically; it had just won the difficult conflict with the West Ukrainian National Republic and was already engaged in new conflicts with Germany (the

Silesian Uprisings

The Silesian Uprisings (german: Aufstände in Oberschlesien, Polenaufstände, links=no; pl, Powstania śląskie, links=no) were a series of three uprisings from August 1919 to July 1921 in Upper Silesia, which was part of the Weimar Republic ...

) and with Czechoslovakia. Polish government was just beginning to organise and had little if any control over various border areas. Six currencies

A currency, "in circulation", from la, currens, -entis, literally meaning "running" or "traversing" is a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins.

A more general def ...

affected by various (and rising rapidly) inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

rates were in circulation. Economy

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the ...

was in shambles, some areas were experiencing food shortages, crime

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in Ca ...

was high and a threat of an armed coup d'etat by some factions was serious.

The situation in Russia was similar. The attention of revolutionary Russia, meanwhile, was predominantly directed at thwarting counter-revolution and intervention by the western powers. Bolshevik Russia had barely survived its second winter of blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are leg ...

and resulting mass starvation and was in the middle of a bloody civil war. Lenin controlled only a part of central Russia

Central Russia is, broadly, the various areas in European Russia.

Historically, the area of Central Russia varied based on the purpose for which it is being used. It may, for example, refer to European Russia (except the North Caucasus and ...

, and the Bolsheviks were surrounded by powerful enemies who needed to be defeated before any thought could be given to advance beyond the unclear Soviet borders. No matter their intent, Lenin and other communist leaders were simply incapable of moving beyond those borders. While the first clashes between Polish and Soviet forces occurred in February 1919, it would be almost a year before both sides realised that they were engaged in a full war.

Piłsudski's motives

Polish politics were under the strong influence of statesman and MarshalJózef Piłsudski

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Naczelnik państwa, Chief of State (1918–1922) and Marshal of Poland, First Marshal of Second Polish Republic, Poland (from 1920). He was ...

, who envisioned a Polish-led federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government ( federalism). In a federation, the self-govern ...

(the "Federation of Międzymorze", aka ''Intermarium'') comprising Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

, and other Central and East European countries now re-emerging out of the crumbling empires after the First World War. The new union would have had borders similar to those of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ru ...

in the 15th–18th centuries, and it was to be a counterweight to, and restraint upon, any imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

intentions of Russia and/or Germany. To this end, Polish forces set out to secure vast territories in the east. However Piłsudski's federation plan was opposed by another influential Polish politician, Roman Dmowski

Roman Stanisław Dmowski (Polish: , 9 August 1864 – 2 January 1939) was a Polish politician, statesman, and co-founder and chief ideologue of the National Democracy (abbreviated "ND": in Polish, "''Endecja''") political movement. He saw th ...

, who favoured creating a larger, national Polish state.

Poland had never any intention of joining the Western intervention in the Russian Civil War or conquering Russia, as it has done once in the 17th century during the Dimitriads. On the contrary, after the White Russians refused to recognise Polish independence, Polish forces acting on orders from Piłsudski delayed or stopped their offensives several times, relieving pressure from Bolshevik forces and thus substantially contributing to White Russian defeat.

Lenin's motives

In April 1920, when the Red Army's major push towards Polish hinterlands took place, the soldiers and commanders were told that defeat of Poland was not only necessary but simply sufficient for the "oppressed masses of the proletariat" to rise worldwide and create a "workers' paradise." In the words of General Tukhachevski: "To the West! Over the corpse of White Poland lies the road to world-wide conflagration. March on Vilno, Minsk, Warsaw!". In late 1919 the leader of Russia's new communist government,Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

, was inspired by the Red Army's civil-war victories over White Russian anti-communist forces and their western allies, and began to see the future of the revolution with greater optimism. The Bolsheviks doctrine said that historical processes would lead to proletariat victory worldwide, and that the nation state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may i ...

s would be replaced by a worldwide communist community. War with Poland was needed if the communist revolution in Russia was to be linked with the expected revolutions in the West, such as the one in Germany. Early Bolshevik ideology made it clear that Poland, which was located in between Russia and Germany, had to become the bridge that the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

would have to cross to fulfill the Marxist doctrine. It was not, however, until the Soviet successes in mid-1920 that this idea became for a short time dominant in Bolshevik policies.

Germany in 1918-1920 was a nation torn by social discontent and embroiled in political chaos. Since the Kaiser's abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

at the end of the First World War, it had seen a series of major internal disturbances, including government takeovers, several general strikes, some leading to communist revolutions (e.g. the Bavarian Soviet Republic

The Bavarian Soviet Republic, or Munich Soviet Republic (german: Räterepublik Baiern, Münchner Räterepublik),Hollander, Neil (2013) ''Elusive Dove: The Search for Peace During World War I''. McFarland. p.283, note 269. was a short-lived unre ...

), By July 1920, which is when the Soviets were on the verge of taking Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

, the Weimar Constitution was still brand new and the humiliating Peace of Versailles, even more so. Germany unstable government had to deal with separatist tendencies, an ongoing conflict, not far from a civil war between the Spartacist League's and Communist Party of Germany and the right-wing Freikorps

(, "Free Corps" or "Volunteer Corps") were irregular German and other European military volunteer units, or paramilitary, that existed from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. They effectively fought as mercenary or private armies, rega ...

, all under the watchful and humiliating eyes of the Allied powers. Red Army's remaking of the Versailles system was seen as a major force that could shake the existing system imposed by the victorious western Entente. As Lenin himself remarked, "That was the time when everyone in Germany, including the blackest reactionaries and monarchists, declared that the Bolsheviks would be their salvation."

In April 1920 Lenin would complete writing ''The Infantile Disease of "Leftism" in Communism'', a guide to the final stages of the Revolution. He became overconfident, entertaining the thoughts of a serious war with Poland. According to him and his adherents, the Revolution in Russia was doomed unless it was to become worldwide. The debate in Russia was "not as to whether the Polish bridge should be crossed, but how and when." According to Lenin's doctrine of "revolution from outside" Red Army's advance into Poland would be an opportunity "to probe Europe with the bayonets of the Red Army", the first attempt to export the Bolshevik Revolution by any means necessary. In a telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

, Lenin wrote: "We must direct all our attention to preparing and strengthening the Western Front

Front may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''The Front'' (1943 film), a 1943 Soviet drama film

* ''The Front'', 1976 film

Music

* The Front (band), an American rock band signed to Columbia Records and active in the 1980s and e ...

. A new slogan must be announced: Prepare for war against Poland."Lincoln, ''Red Victory: a History of the Russian Civil War''.

References

See Polish-Soviet War#Notes {{DEFAULTSORT:Causes Of The Polish-Soviet War Polish-Soviet War, Causes of Polish–Soviet War