The history of Cuba is characterized by dependence on outside powers—

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, the

US, and the

USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. The island of

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

was inhabited by various

Amerindian

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the A ...

cultures prior to the arrival of the

Genoese explorer

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

in 1492. After his arrival on a Spanish expedition, Spain conquered Cuba and appointed

Spanish governors to rule in

Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center. . The administrators in Cuba were subject to the

Viceroy of New Spain

The following is a list of Viceroys of New Spain.

In addition to viceroys, the following lists the highest Spanish governors of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, before the appointment of the first viceroy or when the office of viceroy was vacant. ...

and the local authorities in

Hispaniola. In 1762–63, Havana was briefly occupied by Britain, before being returned to Spain in exchange for

Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

. A series of rebellions between 1868 and 1898, led by General

Máximo Gómez

Máximo Gómez y Báez (November 18, 1836 – June 17, 1905) was a Dominican Generalissimo in Cuba's War of Independence (1895–1898). He was known for his controversial scorched-earth policy, which entailed dynamiting passenger trains a ...

, failed to end Spanish rule and claimed the lives of 49,000 Cuban guerrillas and 126,000 Spanish soldiers. However, the

Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

resulted in a Spanish withdrawal from the island in 1898, and following three-and-a-half years of subsequent

US military rule, Cuba gained formal independence in 1902.

In the years following its independence, the

Cuban republic saw significant economic development, but also political corruption and a succession of despotic leaders, culminating in the overthrow of the dictator

Fulgencio Batista

Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar (; ; born Rubén Zaldívar, January 16, 1901 – August 6, 1973) was a Cuban military officer and politician who served as the elected president of Cuba from 1940 to 1944 and as its U.S.-backed military dictator ...

by the

26th of July Movement, led by

Fidel Castro, during the 1953–1959

Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution ( es, Revolución Cubana) was carried out after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état which placed Fulgencio Batista as head of state and the failed mass strike in opposition that followed. After failing to contest Batista in co ...

. The new government

aligned with the Soviet Union and embraced

communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

. In the early 1960s, Castro's regime

withstood invasion (April 1961), faced nuclear Armageddon (October 1962), and experienced a civil war (October 1960) that included Dominican support for regime opponents. Following the

Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia

The Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia refers to the events of 20–21 August 1968, when the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was jointly invaded by four Warsaw Pact countries: the Soviet Union, the Polish People's Republic, the People's Rep ...

(1968), Castro publicly declared Cuba's support. His speech marked the start of Cuba's complete absorption into the

Eastern Bloc. During the

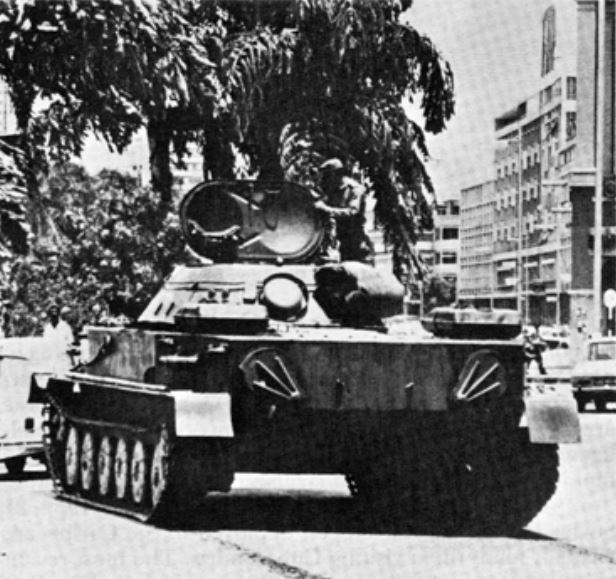

Cold War, Cuba also supported Soviet policy in Afghanistan, Poland, Angola, Ethiopia, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. The

Cuban intervention in Angola

The Cuban intervention in Angola (codenamed Operation Carlota) began on 5 November 1975, when Cuba sent combat troops in support of the communist-aligned People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) against the pro-western National Uni ...

contributed to Namibia gaining independence in 1990 from

apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

ruled South Africa.

The

Cuban economy was mostly supported by Soviet

subsidies

A subsidy or government incentive is a form of financial aid or support extended to an economic sector (business, or individual) generally with the aim of promoting economic and social policy. Although commonly extended from the government, the ter ...

. With the

dissolution of the USSR

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

in 1991 the subsidies disappeared and Cuba was plunged into a severe economic crisis known as the

Special Period

The Special Period ( es, Período especial, link=no), officially the Special Period in the Time of Peace (), was an extended period of economic crisis in Cuba that began in 1991 primarily due to the dissolution of the Soviet Union and, by ext ...

that ended in 2000 when

Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

began providing Cuba with subsidized oil. In 2019,

Miguel Diaz-Canel

-->

Miguel is a given name and surname, the Portuguese and Spanish form of the Hebrew name Michael. It may refer to:

Places

*Pedro Miguel, a parish in the municipality of Horta and the island of Faial in the Azores Islands

* São Miguel (disamb ...

was elected President of Cuba by the national assembly. The country has been

politically and economically isolated by the United States since the Revolution, but has gradually gained access to foreign commerce and travel as

efforts to normalise diplomatic relations have progressed.

Pre-Columbian (to 1500)

Cuba's earliest known human inhabitants colonized the island in the 4th millennium BC. The oldest known Cuban archeological site, Levisa, dates from approximately 3100 BC. A wider distribution of sites date from after 2000 BC, most notably represented by the Cayo Redondo and Guayabo Blanco cultures of western Cuba. These

Cuba's earliest known human inhabitants colonized the island in the 4th millennium BC. The oldest known Cuban archeological site, Levisa, dates from approximately 3100 BC. A wider distribution of sites date from after 2000 BC, most notably represented by the Cayo Redondo and Guayabo Blanco cultures of western Cuba. These neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several p ...

cultures used ground stone

In archaeology, ground stone is a category of stone tool formed by the grinding of a coarse-grained tool stone, either purposely or incidentally. Ground stone tools are usually made of basalt, rhyolite, granite, or other cryptocrystalline a ...

and shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

** Thin-shell structure

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard o ...

tools and ornaments, including the dagger

A dagger is a fighting knife with a very sharp point and usually two sharp edges, typically designed or capable of being used as a thrusting or stabbing weapon.State v. Martin, 633 S.W.2d 80 (Mo. 1982): This is the dictionary or popular-use de ...

-like ''gladiolitos'', which are believed to have had a ceremonial role.[Allaire, p. 688] The Cayo Redondo and Guayabo Blanco cultures lived a subsistence lifestyle based on fishing, hunting and collecting wild plants.Guanajatabey

The Guanahatabey (also spelled Guanajatabey) were an indigenous people of western Cuba at the time of European contact. Archaeological and historical studies suggest the Guanahatabey were archaic hunter-gatherers with a distinct language and cu ...

, who had inhabited Cuba for centuries, were driven to the far west of the island by the arrival of subsequent waves of migrants, including the Taíno

The Taíno were a historic indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the late 15th century, they were the pri ...

and Ciboney

The Ciboney, or Siboney, were a Taíno people of western Cuba, Jamaica, and the Tiburon Peninsula of Haiti. A Western Taíno group living in central Cuba during the 15th and 16th centuries, they had a dialect and culture distinct from the Classi ...

. These people had migrated north along the Caribbean island chain.

The Taíno and Siboney were part of a cultural group commonly called the Arawak

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the Taíno, who historically lived in the Great ...

, who inhabited parts of northeastern South America prior to the arrival of Europeans. Initially, they settled at the eastern end of Cuba, before expanding westward across the island. The Spanish Dominican clergyman and writer Bartolomé de las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas, OP ( ; ; 11 November 1484 – 18 July 1566) was a 16th-century Spanish landowner, friar, priest, and bishop, famed as a historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman then became a Dominican friar ...

estimated that the Taíno population of Cuba had reached 350,000 by the end of the 15th century. The Taíno cultivated the yuca

''Manihot esculenta'', commonly called cassava (), manioc, or yuca (among numerous regional names), is a woody shrub of the spurge family, Euphorbiaceae, native to South America. Although a perennial plant, cassava is extensively cultivated ...

root, harvested it and baked it to produce cassava bread

Tapioca (; ) is a starch extracted from the storage roots of the cassava plant (''Manihot esculenta,'' also known as manioc), a species native to the North and Northeast regions of Brazil, but whose use is now spread throughout South America ...

. They also grew cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

and tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

, and ate maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. The ...

and sweet potatoes. According to ''History of the Indians'', they had "everything they needed for living; they had many crops, well arranged".

Spanish conquest and early colonization (1492 - 1800)

Christopher Columbus, on his first Spanish-sponsored voyage to the Americas in 1492, sailed south from what is now the

Christopher Columbus, on his first Spanish-sponsored voyage to the Americas in 1492, sailed south from what is now the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the ar ...

to explore the northeast coast of Cuba and the northern coast of Hispaniola. Columbus, who was searching for a route to India, believed the island to be a peninsula of the Asian mainland. Columbus arrived at Cuba on Sunday, October 28, 1492 at Puerto de Nipe.[ Gott, Richard (2004). ''Cuba: A new history''. Yale University Press. Chapter 5.]

During a second voyage in 1494, Columbus passed along the south coast of the island, landing at various inlets including what was to become Guantánamo Bay. With the Papal Bull of 1493, Pope Alexander VI commanded Spain to conquer, colonize and convert the pagans of the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

to Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. On arrival, Columbus observed the Taíno dwellings, describing them as "looking like tents in a camp. All were of palm branches, beautifully constructed".

The Spanish began to create permanent settlements on the island of Hispaniola, east of Cuba, soon after Columbus' arrival in the Caribbean, but the coast of Cuba was not fully mapped by Europeans until 1508, when Sebastián de Ocampo completed this task.Hatuey

Hatuey (), also Hatüey (; died 2 February 1512) was a Taíno ''Cacique'' (chief) of the Hispaniola province of Guahaba (present-day La Gonave, Haiti). He lived from the late 15th until the early 16th century. One day Chief Hatuey and many of ...

, who had himself relocated from Hispaniola to escape the brutalities of Spanish rule on that island. After a prolonged guerrilla campaign, Hatuey and successive chieftains were captured and burnt alive, and within three years the Spanish had gained control of the island. In 1514, a settlement was founded in what was to become Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center. .

Clergyman Bartolomé de las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas, OP ( ; ; 11 November 1484 – 18 July 1566) was a 16th-century Spanish landowner, friar, priest, and bishop, famed as a historian and social reformer. He arrived in Hispaniola as a layman then became a Dominican friar ...

observed a number of massacres initiated by the invaders as the Spanish swept over the island, notably the massacre near Camagüey of the inhabitants of Caonao. According to his account, some three thousand villagers had traveled to Manzanillo to greet the Spanish with loaves, fishes and other foodstuffs, and were "without provocation, butchered". The surviving indigenous groups fled to the mountains or the small surrounding islands before being captured and forced into reservations. One such reservation was Guanabacoa

Guanabacoa is a colonial township in eastern Havana, Cuba, and one of the 15 municipalities (or boroughs) of the city. It is famous for its historical Santería and is home to the first African Cabildo in Havana. Guanabacoa was briefly the capital ...

, which is today a suburb of Havana.[Thomas, Hugh. ''Cuba: The Pursuit of Freedom'' (2nd edition). p. 14.]

In 1513, Ferdinand II of Aragon issued a decree establishing the '' encomienda'' land settlement system that was to be incorporated throughout the Spanish Americas. Velázquez, who had become Governor of Cuba relocating from Baracoa to

In 1513, Ferdinand II of Aragon issued a decree establishing the '' encomienda'' land settlement system that was to be incorporated throughout the Spanish Americas. Velázquez, who had become Governor of Cuba relocating from Baracoa to Santiago de Cuba

Santiago de Cuba is the second-largest city in Cuba and the capital city of Santiago de Cuba Province. It lies in the southeastern area of the island, some southeast of the Cuban capital of Havana.

The municipality extends over , and contains ...

, was given the task of apportioning both the land and the indigenous peoples to groups throughout the new colony. The scheme was not a success, however, as the natives either succumbed to diseases brought from Spain such as measles and smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

, or simply refused to work, preferring to slip away into the mountains.Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, also known as the Conquest of Mexico or the Spanish-Aztec War (1519–21), was one of the primary events in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. There are multiple 16th-century narratives of the eve ...

in Cuba, sailing from Santiago to the Yucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula (, also , ; es, Península de Yucatán ) is a large peninsula in southeastern Mexico and adjacent portions of Belize and Guatemala. The peninsula extends towards the northeast, separating the Gulf of Mexico to the north ...

. However, these new arrivals followed the indigenous peoples by also dispersing into the wilderness or dying of disease.tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

and consume it in the form of cigars. There were also many unions between the largely male Spanish colonists and indigenous women. Modern-day studies have revealed traces of DNA that renders physical traits similar to Amazonian tribes in individuals throughout Cuba, although the native population was largely destroyed as a culture and civilization after 1550. Under the Spanish New Laws of 1552, indigenous Cuban were freed from ''encomienda'', and seven towns for indigenous peoples were set up. There are indigenous descendant Cuban (Taíno

The Taíno were a historic indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the late 15th century, they were the pri ...

) families in several places, mostly in eastern Cuba. The indigenous community at Caridad de los Indios, Guantánamo, is one such nucleus. An association of indigenous families in Jiguani, near Santiago, is also active. The local indigenous population also left their mark on the language, with some 400 Taíno terms and place-names surviving to the present day. The name of ''Cuba'' itself, ''Havana'', ''Camagüey'', and many others were derived from Classic Taíno, and indigenous words such as ''tobacco'', ''hurricane'' and ''canoe'' were transferred to English and are used today.

Arrival of African slaves (1500 - 1820)

The Spanish established sugar and

The Spanish established sugar and tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

as Cuba's primary products, and the island soon supplanted Hispaniola as the prime Spanish base in the Caribbean. Further field labor was required. African slaves were then imported to work the plantations as field labor. However, restrictive Spanish trade laws made it difficult for Cubans to keep up with the 17th and 18th century advances in processing sugar cane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, perennial grass (in the genus '' Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fibrous stalk ...

pioneered in Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate) ...

, Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

and Saint-Domingue. Spain also restricted Cuba's access to the slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, instead issuing foreign merchants ''asiento

The () was a monopoly contract between the Spanish Crown and various merchants for the right to provide African slaves to colonies in the Spanish Americas. The Spanish Empire rarely engaged in the trans-Atlantic slave trade directly from Afri ...

s'' to conduct it on Spain's behalf. The advances in the system of sugar cane refinement did not reach Cuba until the Haitian Revolution in the nearby French colony of Saint-Domingue led to thousands of refugee French planters to flee to Cuba and other islands in the West Indies, bringing their slaves and expertise in sugar refining and coffee

Coffee is a drink prepared from roasted coffee beans. Darkly colored, bitter, and slightly acidic, coffee has a stimulating effect on humans, primarily due to its caffeine content. It is the most popular hot drink in the world.

Seeds of ...

growing into eastern Cuba in the 1790s and early 19th century.[Thomas, Hugh. ''Cuba: A History''. Penguin, 2013 p. 89]

In the 19th century, Cuban sugar plantations became the most important world producer of sugar, thanks to the expansion of slavery and a relentless focus on improving the island's sugar technology. Use of modern refining techniques was especially important because the British Slave Trade Act 1807

The Slave Trade Act 1807, officially An Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom prohibiting the slave trade in the British Empire. Although it did not abolish the practice of slavery, it ...

abolished the slave trade in the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

(with slavery itself being abolished in the Slavery Abolition Act 1833

The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which provided for the gradual abolition of slavery in most parts of the British Empire. It was passed by Earl Grey's reforming administrat ...

). The British government set about trying to eliminate the transatlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

. Under British diplomatic pressure, in 1817 Spain agreed to abolish the slave trade from 1820 in exchange for a payment from London. Cubans rapidly rushed to import further slaves in the time legally left to them. Over 100,000 new slaves were imported from Africa between 1816 and 1820.

Sugar plantations

Cuba failed to prosper before the 1760s, due to Spanish trade regulations. Spain had set up a trade monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a speci ...

in the Caribbean, and their primary objective was to protect this, which they did by barring the islands from trading with any foreign ships. The resultant stagnation of economic growth was particularly pronounced in Cuba because of its great strategic importance in the Caribbean, and the stranglehold that Spain kept on it as a result.

As soon as Spain opened Cuba's ports up to foreign ships, a great sugar boom began that lasted until the 1880s. The island was perfect for growing sugar, being dominated by rolling plains, with rich soil and adequate rainfall. By 1860, Cuba was devoted to growing sugar, having to import all other necessary goods. Cuba was particularly dependent on the

As soon as Spain opened Cuba's ports up to foreign ships, a great sugar boom began that lasted until the 1880s. The island was perfect for growing sugar, being dominated by rolling plains, with rich soil and adequate rainfall. By 1860, Cuba was devoted to growing sugar, having to import all other necessary goods. Cuba was particularly dependent on the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, which bought 82 percent of its sugar. In 1820, Spain abolished the slave trade, hurting the Cuban economy even more and forcing planters to buy more expensive, illegal, and "troublesome" slaves (as demonstrated by the slave rebellion on the Spanish ship '' Amistad'' in 1839).

Cuba under attack (1500 - 1800)

Colonial Cuba was a frequent target of

Colonial Cuba was a frequent target of buccaneer

Buccaneers were a kind of privateers or free sailors particular to the Caribbean Sea during the 17th and 18th centuries. First established on northern Hispaniola as early as 1625, their heyday was from the Restoration in 1660 until about 168 ...

s, pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

s and French corsairs

Corsairs (french: corsaire) were privateers, authorized to conduct raids on shipping of a nation at war with France, on behalf of the French crown. Seized vessels and cargo were sold at auction, with the corsair captain entitled to a portion of ...

seeking Spain's New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

riches. In response to repeated raids, defenses were bolstered throughout the island during the 16th century. In Havana, the fortress of Castillo de los Tres Reyes Magos del Morro was built to deter potential invaders, which included the English privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

Francis Drake, who sailed within sight of Havana harbor but did not disembark on the island.[Gott, Richard (2004). ''Cuba: A new history''. Yale University Press. p. 32.] Havana's inability to resist invaders was dramatically exposed in 1628, when a Dutch fleet led by Piet Heyn

Piet Pieterszoon Hein (25 November 1577 – 18 June 1629) was a Dutch admiral and privateer for the Dutch Republic during the Eighty Years' War. Hein was the first and the last to capture a large part of a Spanish treasure fleet which tra ...

plundered the Spanish ships in the city's harbor.[Gott, Richard (2004). ''Cuba: A new history''. Yale University Press. pp. 34–35.] In 1662, English pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

Christopher Myngs

Vice Admiral Sir Christopher Myngs (sometimes spelled ''Mings'', 1625–1666) was an English naval officer and privateer. He came of a Norfolk family and was a relative of Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell. Samuel Pepys' story of Myngs' humble bir ...

captured and briefly occupied Santiago de Cuba

Santiago de Cuba is the second-largest city in Cuba and the capital city of Santiago de Cuba Province. It lies in the southeastern area of the island, some southeast of the Cuban capital of Havana.

The municipality extends over , and contains ...

on the eastern part of the island, in an effort to open up Cuba's protected trade with neighboring Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

.British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fra ...

launched another invasion, capturing Guantánamo Bay in 1741 during the War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear, or , was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Britain and the Spanish Empire. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It is con ...

with Spain. Edward Vernon, the British admiral who devised the scheme, saw his 4,000 occupying troops capitulate to raids by Spanish troops, and more critically, an epidemic, forcing him to withdraw his fleet to British Jamaica.[Gott, Richard (2004). ''Cuba: A new history''. Yale University Press. pp. 39–41.] In the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George's ...

, the British carried out unsuccessful attacks against Santiago de Cuba in 1741 and again in 1748. Additionally, a skirmish between British and Spanish naval squadrons occurred near Havana in 1748.Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

, which erupted in 1754 across three continents, eventually arrived in the Spanish Caribbean

The Spanish West Indies or the Spanish Antilles (also known as "Las Antillas Occidentales" or simply "Las Antillas Españolas" in Spanish) were Spanish colonies in the Caribbean. In terms of governance of the Spanish Empire, The Indies was the de ...

. Spain's alliance with the French pitched them into direct conflict with the British, and in 1762 a British expedition of five warships and 4,000 troops set out from Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

to capture Cuba. The British arrived on 6 June, and by August had Havana under siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characteriz ...

.[Thomas, Hugh. ''Cuba: The Pursuit of Freedom (2nd edition)''. Chapter One.] When Havana surrendered, the admiral of the British fleet, George Keppel, the 3rd Earl of Albemarle

Earl of Albemarle is a title created several times from Norman times onwards. The word ''Albemarle'' is derived from the Latinised form of the French county of ''Aumale'' in Normandy (Latin: ''Alba Marla'' meaning "White Marl", marl being a typ ...

, entered the city as a new colonial governor and took control of the whole western part of the island. The arrival of the British immediately opened up trade with their North American

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Ca ...

and Caribbean colonies, causing a rapid transformation of Cuban society.Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

in exchange for Cuba on France's recommendation to Spain, The French advised that declining the offer could result in Spain losing Mexico and much of the South American mainland to the British.Bernardo de Gálvez

Bernardo Vicente de Gálvez y Madrid, 1st Count of Gálvez (23 July 1746 – 30 November 1786) was a Spanish military leader and government official who served as colonial governor of Spanish Louisiana and Cuba, and later as Viceroy of New Sp ...

, the Spanish governor of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, reconquered Florida for Spain with Mexican, Puerto Rican, Dominican, and Cuban troops.

Reformism, annexation, and independence (1800 - 1898)

In the early 19th century, three major political currents took shape in Cuba: reformism, annexation and independence. In addition, spontaneous and isolated actions carried out from time to time added a current of abolitionism. The 1776 Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

by the thirteen of the British colonies of North America and the successes of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

of 1789 influenced early Cuban liberation movements, as did the successful revolt of black slaves in Haiti in 1791. One of the first of such movements in Cuba, headed by the free black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ...

Nicolás Morales, aimed at gaining equality between "mulatto and whites" and at the abolition of sales taxes and other fiscal burdens. Morales' plot was discovered in 1795 in Bayamo, and the conspirators were jailed.

Reform, autonomy and separatist movements

As a result of the political upheavals caused by the Iberian Peninsular War of 1807-1814 and of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's removal of Ferdinand VII

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Charles IV of Spain

, mother = Maria Luisa of Parma

, birth_date = 14 October 1784

, birth_place = El Escorial, Spain

, death_date =

, death_place = Madrid, Spain

, burial_plac ...

from the Spanish throne in 1808, a western separatist rebellion emerged among the Cuban Creole aristocracy in 1809 and 1810. One of its leaders, Joaquín Infante, drafted Cuba's first constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

, declaring the island a sovereign state, presuming the rule of the country's wealthy, maintaining slavery as long as it was necessary for agriculture, establishing a social classification based on skin color and declaring Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

the official religion. This conspiracy also failed, and the main leaders were sentenced to prison and deported to Spain.[Cantón Navarro, José and Juan Jacobin (1998). ''History of Cuba: The Challenge of the Yoke and the Star: Biography of a People''. Havana: Editoral SI-MAR. . p. 35.]

In 1812 a mixed-race abolitionist conspiracy arose, organized by José Antonio Aponte, a free-black carpenter in Havana. He and others were executed.

The Spanish Constitution of 1812

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy ( es, link=no, Constitución Política de la Monarquía Española), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz ( es, link=no, Constitución de Cádiz) and as ''La Pepa'', was the first Constitut ...

, and the legislation passed by the Cortes of Cádiz

The Cortes of Cádiz was a revival of the traditional ''cortes'' (Spanish parliament), which as an institution had not functioned for many years, but it met as a single body, rather than divided into estates as with previous ones.

The General ...

after it was set up in 1808, instituted a number of liberal political and commercial policies, which were welcomed in Cuba but also curtailed a number of older liberties. Between 1810 and 1814 the island elected six representatives to the Cortes, in addition to forming a locally elected Provincial Deputation. Nevertheless, the liberal regime and the Constitution proved ephemeral: Ferdinand VII suppressed them when he returned to the throne in 1814. Therefore, by the end of the 1810s, some Cubans were inspired by the successes of Simón Bolívar in South America, despite the fact that the Spanish Constitution was restored in 1820. Numerous secret-societies emerged, most notably the so-called " Soles y Rayos de Bolívar", founded in 1821 and led by José Francisco Lemus. It aimed to establish the free Republic of Cubanacán (a Taíno

The Taíno were a historic indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the late 15th century, they were the pri ...

name for the center of the island), and it had branches in five districts of the island.

In 1823 the society's leaders were arrested and condemned to exile. In the same year, King Ferdinand VII, with French help and with the approval of the Quintuple Alliance, managed to abolish constitutional rule in Spain yet again and to re-establish absolutism. As a result, the national militia of Cuba, established by the Constitution and a potential instrument for liberal agitation, was dissolved, a permanent executive military commission under the orders of the governor was created, newspapers were closed, elected provincial representatives were removed and other liberties suppressed.

This suppression, and the success of independence movements in the former Spanish colonies on the North American mainland, led to a notable rise of Cuban nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

. A number of independence conspiracies developed during the 1820s and 1830s, but all failed. Among these were the "Expedición de los Trece" (Expedition of the 13) in 1826, the "Gran Legión del Aguila Negra" (Great Legion of the Black Eagle) in 1829, the "Cadena Triangular" (Triangular Chain) and the "Soles de la Libertad" (Suns of Liberty) in 1837. Leading national figures in these years included Félix Varela

Félix Varela y Morales (November 20, 1788 – February 18, 1853) was a Cuban Catholic priest and independence leader who is regarded as a notable figure in the Catholic Church in both his native Cuba and the United States, where he also served.

...

(1788-1853) and Cuba's first revolutionary poet, José María Heredia (1803-1839).

Between 1810 and 1826, 20,000 royalist refugees from the Latin American Revolutions arrived in Cuba. They were joined by others who left Florida when Spain ceded it to the United States in 1819. These influxes strengthened loyalist pro-Spanish sentiments on the island.

Antislavery and independence movements

In 1826 the first armed uprising for independence took place in Puerto Príncipe (Camagüey Province

Camagüey () is the largest of the provinces of Cuba. Its capital is Camagüey. Other towns include Florida and Nuevitas.

Geography

Camagüey is mostly low lying, with no major hills or mountain ranges passing through the province. Numerous la ...

), led by Francisco de Agüero and Andrés Manuel Sánchez. Agüero, a white man, and Sánchez, a mulatto, were both executed, becoming the first popular martyrs of the Cuban independence movement.

The 1830s saw a surge of activity from the reformist movement, whose main leader

Leadership, both as a research area and as a practical skill, encompasses the ability of an individual, group or organization to "lead", influence or guide other individuals, teams, or entire organizations. The word "leadership" often gets vi ...

, José Antonio Saco

José Antonio Saco (May 7, 1797 – September 26, 1879) was a statesman, deputy to the Spanish Cortes, writer, social critic, publicist, essayist, anthropologist, historian, and one of the most notable Cuban figures from the nineteenth century.

...

, stood out for his criticism of Spanish despotism and of the slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. Nevertheless, this surge bore no fruit; Cubans remained deprived of the right to send representatives to the Spanish parliament, and Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the Largest cities of the Europ ...

stepped up repression.

Nonetheless, Spain had long been under pressure to end the slave trade. In 1817 Ferdinand VII signed a decree,

to which the Spanish Empire did not adhere. Under British diplomatic pressure, the Spanish government signed a treaty in 1835 which pledged to eventually abolish slavery and the slave trade. In this context, Black revolts in Cuba increased, and were put down with mass executions. One of the most significant was the Conspiración de la Escalera (Ladder Conspiracy), which started in March 1843 and continued until 1844. The conspiracy took its name from a torture method, in which Black persons were tied to a ladder and whipped until they confessed or died. The Ladder Conspiracy involved free Black persons and enslaved, as well as white intellectuals and professionals. It is estimated that 300 Black and mixed-race persons died from torture, 78 were executed, over 600 were imprisoned and over 400 expelled from the island.[Cantón Navarro, José (1998). ''History of Cuba''. La Habana. p. 40. .] (See comments in new translation of Villaverde's "Cecilia Valdés".) The executed included the leading poet (1809-1844), now commonly known as "Plácido". José Antonio Saco

José Antonio Saco (May 7, 1797 – September 26, 1879) was a statesman, deputy to the Spanish Cortes, writer, social critic, publicist, essayist, anthropologist, historian, and one of the most notable Cuban figures from the nineteenth century.

...

, one of Cuba's most prominent thinkers, was expelled from Cuba.

Following the 1868–1878 rebellion of the Ten Years' War

The Ten Years' War ( es, Guerra de los Diez Años; 1868–1878), also known as the Great War () and the War of '68, was part of Cuba's fight for independence from Spain. The uprising was led by Cuban-born planters and other wealthy natives. O ...

, all slavery was abolished by 1886, making Cuba the second-to-last country in the Western Hemisphere to abolish slavery, with Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

being the last. Instead of Black people, slave traders looked for others sources of cheap labour, such as Chinese colonists and Indians from Yucatán

Yucatán (, also , , ; yua, Yúukatan ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Yucatán,; yua, link=no, Xóot' Noj Lu'umil Yúukatan. is one of the 31 states which comprise the federal entities of Mexico. It comprises 106 separate mun ...

. Another feature of the population was the number of Spanish-born colonists, known as ''peninsulares

In the context of the Spanish Empire, a ''peninsular'' (, pl. ''peninsulares'') was a Spaniard born in Spain residing in the New World, Spanish East Indies, or Spanish Guinea. Nowadays, the word ''peninsulares'' makes reference to Peninsular ...

'', who were mostly adult males; they constituted between ten and twenty per cent of the population between the middle of the 19th century and the great depression of the 1930s.

The possibility of annexation by the United States

Black unrest and attempts by the Spanish metropolis to abolish slavery motivated many Creoles to advocate Cuba's annexation by the United States, where slavery was still legal. Other Cubans supported the idea due to their desire for American-style economic development and democratic freedom. The annexation of Cuba was repeatedly proposed by government officials in the United States. In 1805, President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

considered annexing Cuba for strategic reasons, sending secret agents to the island to negotiate with Captain General Someruelos.

In April 1823, U.S. Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

discussed the rules of political gravitation, in a theory often referred to as the "ripe fruit theory". Adams wrote, "There are laws of political as well as physical gravitation; and if an apple severed by its native tree cannot choose but fall to the ground, Cuba, forcibly disjoined from its own unnatural connection with Spain, and incapable of self-support, can gravitate only towards the North American Union which by the same law of nature, cannot cast her off its bosom". He furthermore warned that "the transfer of Cuba to Great Britain would be an event unpropitious to the interest of this Union". Adams voiced concern that a country outside of North America would attempt to occupy Cuba upon its separation from Spain. He wrote, "The question both of our right and our power to prevent it, if necessary, by force, already obtrudes itself upon our councils, and the administration is called upon, in the performance of its duties to the nation, at least to use all the means with the competency to guard against and forfend it".

On 2 December 1823, U.S. President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

specifically addressed Cuba and other European colonies in his proclamation of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

. Cuba, located just from Key West, Florida, was of interest to the doctrine's founders, as they warned European forces to leave "America for the Americans".

The most outstanding attempts in support of annexation were made by the Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

n filibuster General Narciso López

Narciso López (November 2, 1797, Caracas – September 1, 1851, Havana) was a Venezuelan-born adventurer and Spanish Army general who is best known for his expeditions aimed at liberating Cuba from Spanish rule in the 1850s. His troops carrie ...

, who prepared four expeditions to Cuba in the US. The first two, in 1848 and 1849, failed before departure due to U.S. opposition. The third, made up of some 600 men, managed to land in Cuba and take the central city of Cárdenas, but failed eventually due to a lack of popular support. López's fourth expedition landed in Pinar del Río

Pinar del Río is the capital city of Pinar del Río Province, Cuba. With a population of 139,336 (2004) in a municipality of 190,332, it is the 10th-largest city in Cuba. Inhabitants of the area are called ''Pinareños''.

History

Pinar del R� ...

province with around 400 men in August 1851; the invaders were defeated by Spanish troops and López was executed.

The struggle for independence

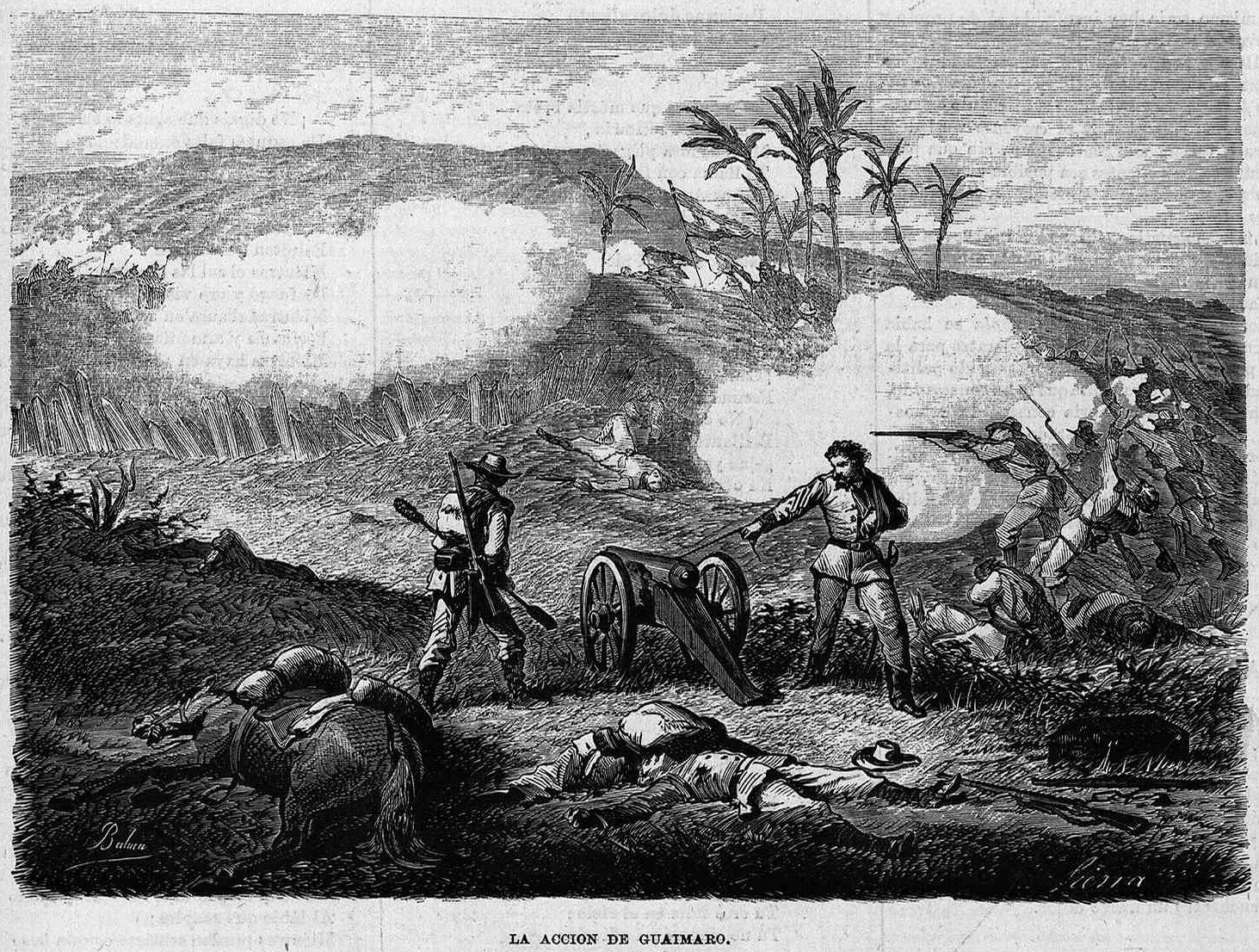

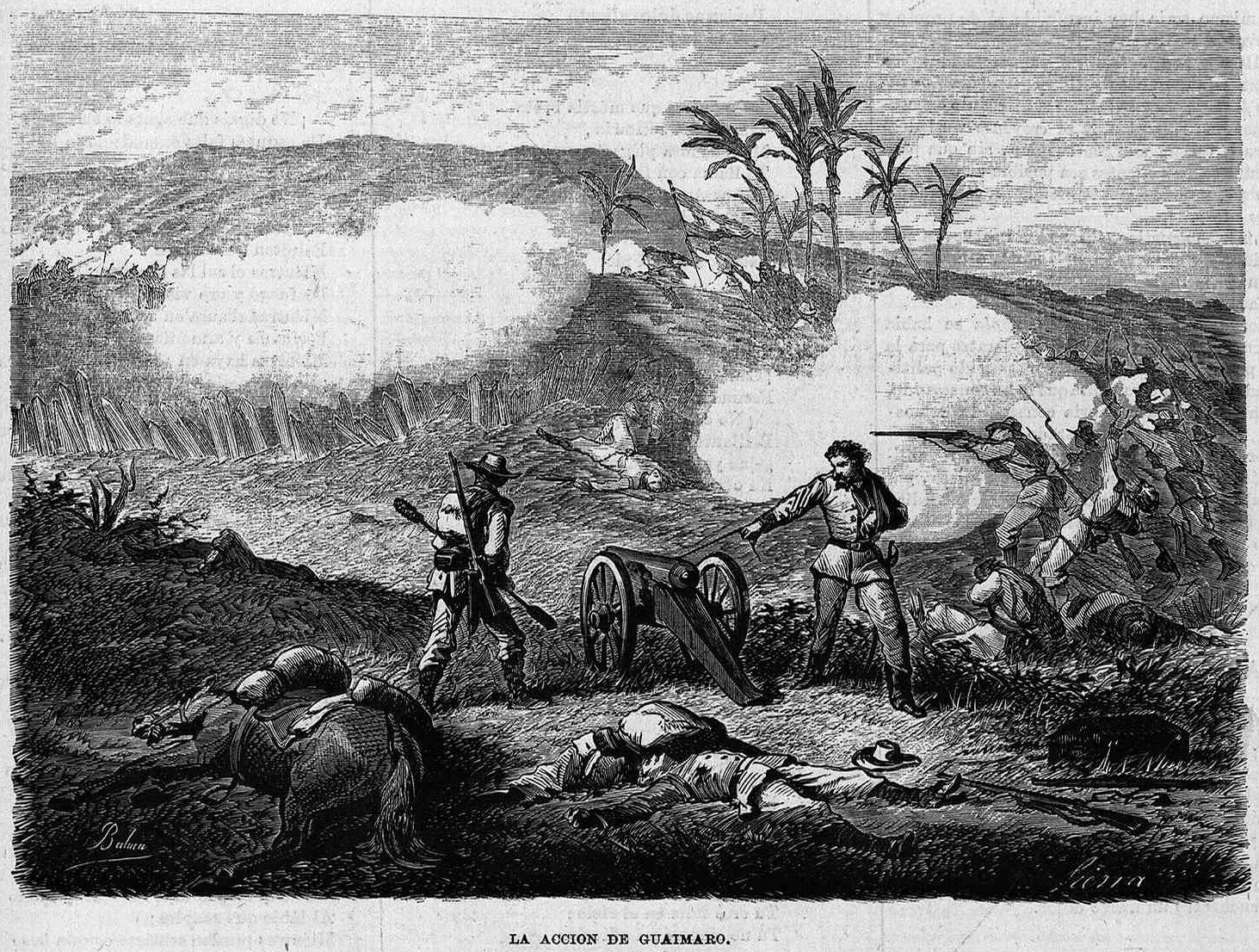

In the 1860s, Cuba had two more liberal-minded governors, Serrano and Dulce, who encouraged the creation of a Reformist Party, despite the fact that political parties were forbidden. But they were followed by a reactionary governor, Francisco Lersundi, who suppressed all liberties granted by the previous governors and maintained a pro-slavery regime. On 10 October 1868, the landowner Carlos Manuel de Céspedes declared Cuban independence and freedom for his slaves. This began the

In the 1860s, Cuba had two more liberal-minded governors, Serrano and Dulce, who encouraged the creation of a Reformist Party, despite the fact that political parties were forbidden. But they were followed by a reactionary governor, Francisco Lersundi, who suppressed all liberties granted by the previous governors and maintained a pro-slavery regime. On 10 October 1868, the landowner Carlos Manuel de Céspedes declared Cuban independence and freedom for his slaves. This began the Ten Years' War

The Ten Years' War ( es, Guerra de los Diez Años; 1868–1878), also known as the Great War () and the War of '68, was part of Cuba's fight for independence from Spain. The uprising was led by Cuban-born planters and other wealthy natives. O ...

, which lasted from 1868 to 1878. The Dominican Restoration War (1863–65) brought to Cuba an unemployed mass of former Dominican white and light-skinned mulattos who had served with the Spanish Army in the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with ...

before being evacuated to Cuba and discharged from the army.[ Some of these former soldiers joined the new Revolutionary Army and provided its initial training and leadership.][

With reinforcements and guidance from the Dominicans, the Cuban rebels defeated Spanish detachments, cut railway lines, and gained dominance over vast sections of the eastern portion of the island. The Spanish government used the Voluntary Corps to commit harsh and bloody acts against the Cuban rebels, and the Spanish atrocities fuelled the growth of insurgent forces in eastern Cuba; however, they failed to export the revolution to the west. On 11 May 1873, ]Ignacio Agramonte

Ignacio Agramonte y Loynaz (1841–1873) was a Cubans, Cuban revolutionary, who played an important part in the Ten Years' War (1868–1878).

Biography

Born in the province of Puerto Príncipe (what is now the province of Camagüey Province, Cam ...

was killed by a stray bullet; Céspedes was surprised and killed on 27 February 1874. In 1875, Máximo Gómez

Máximo Gómez y Báez (November 18, 1836 – June 17, 1905) was a Dominican Generalissimo in Cuba's War of Independence (1895–1898). He was known for his controversial scorched-earth policy, which entailed dynamiting passenger trains a ...

began an invasion of Las Villas west of a fortified military line, or ''trocha'', bisecting the island. The ''trocha'' was built between 1869 and 1872; the Spanish erected it to prevent Gómez to move westward from Oriente province. It was the largest fortification built by the Spanish in the Americas.

Gómez was controversial in his calls to burn sugar plantations to harass the Spanish occupiers. After the American admiral Henry Reeve was killed in 1876, Gómez ended his campaign. By that year, the Spanish government had deployed more than 250,000 troops to Cuba, as the end of the Third Carlist War

The Third Carlist War ( es, Tercera Guerra Carlista) (1872–1876) was the last Carlist War in Spain. It is sometimes referred to as the "Second Carlist War", as the earlier "Second" War (1847–1849) was smaller in scale and relatively trivial ...

had freed up Spanish soldiers for the suppression of the revolt. On 10 February 1878, General Arsenio Martínez Campos

Arsenio Martínez-Campos y Antón, born Martínez y Campos (14 December 1831, in Segovia, Spain – 23 September 1900, in Zarauz, Spain), was a Spanish officer who rose against the First Spanish Republic in a military revolution in 1874 and res ...

negotiated the Pact of Zanjón

The Pact of Zanjón ended the armed struggle of Cubans for independence from the Spanish Empire that lasted from 1868 to 1878, the Ten Years' War. On February 10, 1878, a group of negotiators representing the rebels gathered in Zanjón, a village ...

with the Cuban rebels, and the rebel general Antonio Maceo's surrender on 28 May ended the war. Spain sustained 200,000 casualties, mostly from disease; the rebels sustained 100,000–150,000 dead and the island sustained over $300 million in property damage.

Conflicts in the late 19th century (1886 - 1900)

Background

Social, political, and economic change

During the time of the so-called "Rewarding Truce", which encompassed the 17 years from the end of the Ten Years' War in 1878, fundamental changes took place in Cuban society. With the abolition of slavery in October 1886, former slaves joined the ranks of farmers and urban working class. Most wealthy Cubans lost their rural properties, and many of them joined the urban middle class. The number of sugar mills dropped and efficiency increased, with only companies and the most powerful plantation owners owning them. The numbers of campesinos and tenant farmers rose considerably. Furthermore, American capital began flowing into Cuba, mostly into the sugar and tobacco businesses and mining. By 1895, these investments totalled $50 million. Although Cuba remained Spanish politically, economically it became increasingly dependent on the United States.

These changes also entailed the rise of labour movements. The first Cuban labour organization, the Cigar Makers Guild, was created in 1878, followed by the Central Board of Artisans in 1879, and many more across the island. Abroad, a new trend of aggressive American influence emerged, evident in Secretary of State James G. Blaine's expressed belief that all of Central and South America would some day fall to the US. Blaine placed particular importance on the control of Cuba. "That rich island", he wrote on 1 December 1881, "the key to the Gulf of Mexico, is, though in the hands of Spain, a part of the American commercial system…If ever ceasing to be Spanish, Cuba must necessarily become American and not fall under any other European domination".

Martí's Insurrection and the start of the war

After his second deportation to Spain in 1878, the pro-independence Cuban activist José Martí

José Julián Martí Pérez (; January 28, 1853 – May 19, 1895) was a Cuban nationalist, poet, philosopher, essayist, journalist, translator, professor, and publisher, who is considered a Cuban national hero because of his role in the libera ...

moved to the United States in 1881, where he began mobilizing the support of the Cuban exile community in Florida, especially in Ybor City in Tampa and Key West. He sought a revolution and Cuban independence from Spain, but also lobbied to oppose U.S. annexation of Cuba, which some American and Cuban politicians desired. Propaganda efforts continued for years and intensified starting in 1895.

After deliberations with patriotic clubs across the United States, the Antilles and Latin America, the ''Partido Revolucionario Cubano'' (Cuban Revolutionary Party) was officially proclaimed on 10 April 1892, with the purpose of gaining independence for both Cuba and Puerto Rico. Martí was elected delegate, the highest party position. By the end of 1894, the basic conditions for launching the revolution were set. In Foner's words, "Martí's impatience to start the revolution for independence was affected by his growing fear that the United States would succeed in annexing Cuba before the revolution could liberate the island from Spain".[Foner, Philip: ''The Spanish-Cuban-American War and the Birth of American Imperialism''. Quoted in]

"The War for Cuban Independence"

. HistoryofCuba.com. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

On 25 December 1894, three ships, the ''Lagonda'', the ''Almadis'' and the ''Baracoa'', set sail for Cuba from Fernandina Beach, Florida

Fernandina Beach is a city in northeastern Florida and the county seat of Nassau County, Florida, United States. It is the northernmost city on Florida's Atlantic coast, situated on Amelia Island, and is one of the principal municipalities comp ...

, loaded with armed men and supplies. Two of the ships were seized by U.S. authorities in early January, who also alerted the Spanish government, but the proceedings went ahead. The insurrection began on 24 February 1895, with uprisings all across the island. In Oriente the most important ones took place in Santiago, Guantánamo, Jiguaní, San Luis, El Cobre, El Caney, Alto Songo, Bayate and Baire. The uprisings in the central part of the island, such as Ibarra, Jagüey Grande and Aguada, suffered from poor co-ordination and failed; the leaders were captured, some of them deported and some executed. In the province of Havana the insurrection was discovered before it got off and the leaders detained. Thus, the insurgents further west in Pinar del Río were ordered to wait.

Martí, on his way to Cuba, gave the Proclamation of Montecristi in Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

, outlining the policy for Cuba's war of independence: the war was to be waged by blacks and whites alike; participation of all blacks was crucial for victory; Spaniards who did not object to the war effort should be spared, private rural properties should not be damaged; and the revolution should bring new economic life to Cuba.Baracoa

Baracoa, whose full original name is: ''Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de Baracoa'' (“Our Lady of the Assumption of Baracoa”), is a municipality and city in Guantánamo Province near the eastern tip of Cuba. It was visited by Admiral Christop ...

and Martí, Máximo Gómez

Máximo Gómez y Báez (November 18, 1836 – June 17, 1905) was a Dominican Generalissimo in Cuba's War of Independence (1895–1898). He was known for his controversial scorched-earth policy, which entailed dynamiting passenger trains a ...

and four other members in Playitas. Around that time, Spanish forces in Cuba numbered about 80,000, of which 20,000 were regular troops, and 60,000 were Spanish and Cuban volunteers. The latter were a locally enlisted force that took care of most of the ''guard and police'' duties on the island. Wealthy landowners would ''volunteer'' a number of their slaves to serve in this force, which was under local control and not under official military command. By December, 98,412 regular troops had been sent to the island and the number of volunteers had increased to 63,000 men. By the end of 1897, there were 240,000 regulars and 60,000 irregulars on the island. The revolutionaries were far outnumbered.

Escalation of the war

Martí was killed on 19 May 1895, during a reckless charge against entrenched Spanish forces, but

Martí was killed on 19 May 1895, during a reckless charge against entrenched Spanish forces, but Máximo Gómez

Máximo Gómez y Báez (November 18, 1836 – June 17, 1905) was a Dominican Generalissimo in Cuba's War of Independence (1895–1898). He was known for his controversial scorched-earth policy, which entailed dynamiting passenger trains a ...

(a Dominican) and Antonio Maceo (a mulatto) fought on, taking the war to all parts of Oriente. Gómez used scorched-earth tactics, which entailed dynamiting passenger trains and burning the Spanish loyalists' property and sugar plantations—including many owned by Americans. By the end of June all of Camagüey was at war. Continuing west, Gómez and Maceo joined up with veterans of the 1868 war, Polish internationalists, General Carlos Roloff

Karol Rolow-Miałowski or Carlos Roloff Mialofsky, better known simply as Carlos Roloff, (4 November 1842 – 17 May 1907) was a Polish-born Cuban general and liberation activist, who fought against Spain in the Ten Years' War and the Cuban War o ...

and Serafín Sánchez in Las Villas, swelling their ranks and boosting their arsenal. In mid-September, representatives of the five Liberation Army Corps assembled in Jimaguayú

Jimaguayú () is a municipality and town in the Camagüey Province of Cuba.

Demographics

In 2004, the municipality of Jimaguayú had a population of 21,169. With a total area of , it has a population density of .

See also

* Jimaguayú Municipal ...

, Camagüey, to approve the Jimaguayú Constitution. This constitution established a central government, which grouped the executive and legislative powers into one entity, the Government Council, which was headed by Salvador Cisneros and Bartolomé Masó

Bartolomé de Jesús Masó Márquez (21 December 1830 in Yara – 14 June 1907 in Manzanillo) was a Cuban politician and military, patriot for Cuban independence from the colonial power of Spain, and later President of the ''República en Ar ...

.

After a period of consolidation in the three eastern provinces, the liberation armies headed for Camagüey and then for Matanzas, outmanoeuvring and deceiving the Spanish Army several times. The revolutionaries defeated the Spanish general Arsenio Martínez Campos

Arsenio Martínez-Campos y Antón, born Martínez y Campos (14 December 1831, in Segovia, Spain – 23 September 1900, in Zarauz, Spain), was a Spanish officer who rose against the First Spanish Republic in a military revolution in 1874 and res ...

, himself the victor of the Ten Years' War, and killed his most trusted general at Peralejo. Campos tried the same strategy he had employed in the Ten Years' War, constructing a broad defensive belt across the island, about long and wide. This line, called the ''trocha'', was intended to limit rebel activities to the eastern provinces, and consisted of a railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

, from Jucaro in the south to Moron in the north, on which armored railcars could travel. At various points along this railroad there were fortifications, at intervals of there were posts and at intervals of there was barbed wire. In addition, booby traps were placed at the locations most likely to be attacked.

For the rebels, it was essential to bring the war to the western provinces of Matanzas, Havana and Pinar del Río, where the island's government and wealth was located. The Ten Years' War failed because it had not managed to proceed beyond the eastern provinces. Unable to defeat the rebels with conventional military tactics, the Spanish government sent Gen.

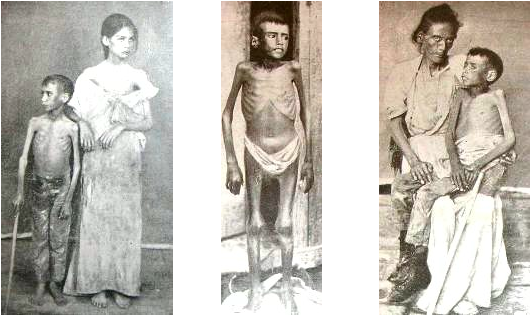

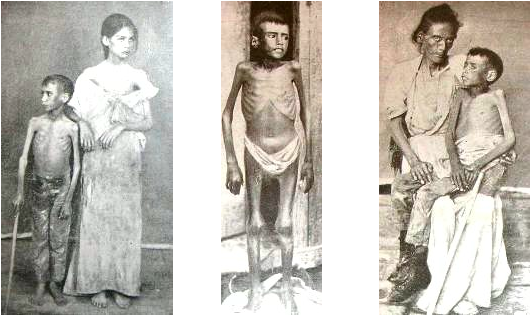

Unable to defeat the rebels with conventional military tactics, the Spanish government sent Gen. Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau

Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau, 1st Duke of Rubí, 1st Marquess of Tenerife (17 September 1838 – 20 October 1930) was a Spanish general and colonial administrator who served as the Governor-General of the Philippines and Cuba, and later as S ...

(nicknamed ''The Butcher''), who reacted to these rebel successes by introducing terror methods: periodic executions, mass exiles, and the destruction of farms and crops. These methods reached their height on 21 October 1896, when he ordered all countryside residents and their livestock to gather in various fortified areas and towns occupied by his troops within eight days. Hundreds of thousands of people had to leave their homes, creating appalling conditions of overcrowding in the towns and cities. This was the first recorded and recognized use of concentration camps where non-combatants were removed from their land to deprive the enemy of succor and then the internees were subjected to appalling conditions. The Spanish also employed the use of concentration camps in the Philippines shortly after, again resulting in massive non-combatant fatalities. It is estimated that this measure caused the death of at least one-third of Cuba's rural population. The forced relocation policy was maintained until March 1898.Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, which was intensifying; Spain was thus now fighting two wars, which placed a heavy burden on its economy. In secret negotiations in 1896, Spain turned down the United States' offers to buy Cuba.

Maceo was killed on 7 December 1896, in Havana province, while returning from the west. As the war continued, the major obstacle to Cuban success was weapons supply. Although weapons and funding came from within the United States, the supply operation violated American laws, which were enforced by the U.S. Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is the maritime security, search and rescue, and law enforcement service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the country's eight uniformed services. The service is a maritime, military, mul ...

; of 71 resupply missions, only 27 got through, with 5 being stopped by the Spanish and 33 by the U.S. Coast Guard.

In 1897, the liberation army maintained a privileged position in Camagüey and Oriente, where the Spanish only controlled a few cities. Spanish liberal leader Praxedes Sagasta admitted in May 1897: "After having sent 200,000 men and shed so much blood, we don't own more land on the island than what our soldiers are stepping on". The rebel force of 3,000 defeated the Spanish in various encounters, such as the battle of La Reforma and the surrender of Las Tunas on 30 August, and the Spaniards were kept on the defensive. Las Tunas had been guarded by over 1,000 well-armed and well-supplied men.

As stipulated at the Jimaguayú Assembly two years earlier, a second Constituent Assembly met in La Yaya, Camagüey, on 10 October 1897. The newly adopted constitution decreed that a military command be subordinated to civilian rule. The government was confirmed, naming Bartolomé Masó as president and Domingo Méndez Capote as vice president. Thereafter, Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the Largest cities of the Europ ...

decided to change its policy toward Cuba, replacing Weyler, drawing up a colonial constitution for Cuba and Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and unincorporated ...

, and installing a new government in Havana. But with half the country out of its control, and the other half in arms, the new government was powerless and rejected by the rebels.

The ''USS Maine'' incident

The Cuban struggle for independence had captured the North American imagination for years and newspapers had been agitating for intervention with sensational stories of Spanish atrocities against the native Cuban population. Americans came to believe that Cuba's battle with Spain resembled United States's Revolutionary War. This continued even after Spain replaced Weyler and said it changed its policies, and the North American public opinion was very much in favor of intervening in favor of the Cubans.

In January 1898, a riot by Cuban-Spanish loyalists against the new autonomous government broke out in Havana, leading to the destruction of the printing presses of four local newspapers which published articles critical of the Spanish Army. The U.S. Consul-General cabled Washington, fearing for the lives of Americans living in Havana. In response, the battleship was sent to

The Cuban struggle for independence had captured the North American imagination for years and newspapers had been agitating for intervention with sensational stories of Spanish atrocities against the native Cuban population. Americans came to believe that Cuba's battle with Spain resembled United States's Revolutionary War. This continued even after Spain replaced Weyler and said it changed its policies, and the North American public opinion was very much in favor of intervening in favor of the Cubans.

In January 1898, a riot by Cuban-Spanish loyalists against the new autonomous government broke out in Havana, leading to the destruction of the printing presses of four local newspapers which published articles critical of the Spanish Army. The U.S. Consul-General cabled Washington, fearing for the lives of Americans living in Havana. In response, the battleship was sent to Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center. in the last week of January. On 15 February 1898, the ''Maine'' was destroyed by an explosion, killing 268 crewmembers. The cause of the explosion has not been clearly established to this day, but the incident focused American attention on Cuba, and President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

and his supporters could not stop Congress from declaring war to "liberate" Cuba.

In an attempt to appease the United States, the colonial government took two steps that had been demanded by President McKinley: it ended the forced relocation policy and offered negotiations with the independence fighters. However, the truce was rejected by the rebels and the concessions proved too late and too ineffective. Madrid asked other European powers for help; they refused and said Spain should back down.

On 11 April 1898, McKinley asked Congress for authority to send U.S. Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is the ...

troops to Cuba for the purpose of ending the civil war there. On 19 April, Congress passed joint resolutions (by a vote of 311 to 6 in the House and 42 to 35 in the Senate) supporting Cuban independence and disclaiming any intention to annex Cuba, demanding Spanish withdrawal, and authorizing the president to use as much military force as he thought necessary to help Cuban patriots gain independence from Spain. This was adopted by resolution of Congress and included from Senator Henry Teller the Teller Amendment

The Teller Amendment was an amendment to a joint resolution of the United States Congress, enacted on April 20, 1898, in reply to President William McKinley's War Message. It placed a condition on the United States military's presence in Cuba. Ac ...

, which passed unanimously, stipulating that "the island of Cuba is, and by right should be, free and independent".[Cantón Navarro, José. ''History of Cuba'', p. 71.] The amendment disclaimed any intention on the part of the United States to exercise jurisdiction or control over Cuba for other than pacification reasons, and confirmed that the armed forces would be removed once the war is over. Senate and Congress passed the amendment on 19 April, McKinley signed the joint resolution on 20 April and the ultimatum was forwarded to Spain. War was declared on 20/21 April 1898.

"It's been suggested that a major reason for the U.S. war against Spain was the fierce competition emerging between Joseph Pulitzer

Joseph Pulitzer ( ; born Pulitzer József, ; April 10, 1847 – October 29, 1911) was a Hungarian-American politician and newspaper publisher of the '' St. Louis Post-Dispatch'' and the ''New York World''. He became a leading national figure in ...

's New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under pub ...

and William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal

:''Includes coverage of New York Journal-American and its predecessors New York Journal, The Journal, New York American and New York Evening Journal''

The ''New York Journal-American'' was a daily newspaper published in New York City from 1937 t ...

", Joseph E. Wisan wrote in an essay titled "The Cuban Crisis As Reflected in the New York Press"

(1934). He stated that "In the opinion of the writer, the Spanish–American War would not have occurred had not the appearance of Hearst in New York journalism precipitated a bitter battle for newspaper circulation." It has also been argued that the main reason the United States entered the war was the failed secret attempt, in 1896, to purchase Cuba from a weaker, war-depleted Spain.