Jack the Ripper on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified

In the mid-19th century, England experienced an influx of

In the mid-19th century, England experienced an influx of

The large number of attacks against women in the East End during this time adds uncertainty to how many victims were murdered by the same individual. Eleven separate murders, stretching from 1888 to 1891, were included in a Metropolitan Police investigation and were known collectively in the police docket as the "Whitechapel murders". Opinions vary as to whether these murders should be linked to the same culprit, but five of the eleven Whitechapel murders, known as the "canonical five", are widely believed to be the work of the Ripper. Most experts point to deep slash wounds to the throat, followed by extensive abdominal and genital-area mutilation, the removal of internal organs, and progressive facial mutilations as the distinctive features of the Ripper's ''

The large number of attacks against women in the East End during this time adds uncertainty to how many victims were murdered by the same individual. Eleven separate murders, stretching from 1888 to 1891, were included in a Metropolitan Police investigation and were known collectively in the police docket as the "Whitechapel murders". Opinions vary as to whether these murders should be linked to the same culprit, but five of the eleven Whitechapel murders, known as the "canonical five", are widely believed to be the work of the Ripper. Most experts point to deep slash wounds to the throat, followed by extensive abdominal and genital-area mutilation, the removal of internal organs, and progressive facial mutilations as the distinctive features of the Ripper's ''

One week later, on Saturday 1888, the body of Annie Chapman was discovered at approximately near the steps to the doorway of the back yard of 29

One week later, on Saturday 1888, the body of Annie Chapman was discovered at approximately near the steps to the doorway of the back yard of 29  Eddowes's body was found in a corner of

Eddowes's body was found in a corner of  Each of the canonical five murders was perpetrated at night, on or close to a weekend, either at the end of a month or a week (or so) after. The mutilations became increasingly severe as the series of murders proceeded, except for that of Stride, whose attacker may have been interrupted. Nichols was not missing any organs; Chapman's uterus and sections of her bladder and vagina were taken; Eddowes had her uterus and left kidney removed and her face mutilated; and Kelly's body was extensively eviscerated, with her face "gashed in all directions" and the tissue of her neck being severed to the bone, although the heart was the sole body organ missing from this crime scene.

Historically, the belief these five canonical murders were committed by the same perpetrator is derived from contemporaneous documents which link them together to the exclusion of others. In 1894, Sir

Each of the canonical five murders was perpetrated at night, on or close to a weekend, either at the end of a month or a week (or so) after. The mutilations became increasingly severe as the series of murders proceeded, except for that of Stride, whose attacker may have been interrupted. Nichols was not missing any organs; Chapman's uterus and sections of her bladder and vagina were taken; Eddowes had her uterus and left kidney removed and her face mutilated; and Kelly's body was extensively eviscerated, with her face "gashed in all directions" and the tissue of her neck being severed to the bone, although the heart was the sole body organ missing from this crime scene.

Historically, the belief these five canonical murders were committed by the same perpetrator is derived from contemporaneous documents which link them together to the exclusion of others. In 1894, Sir

At on 13 February 1891, PC Ernest Thompson discovered a 25-year-old prostitute named Frances Coles lying beneath a railway arch at Swallow Gardens, Whitechapel. Her throat had been deeply cut but her body was not mutilated, leading some to believe Thompson had disturbed her assailant. Coles was still alive, although she died before medical help could arrive. A 53-year-old stoker,

At on 13 February 1891, PC Ernest Thompson discovered a 25-year-old prostitute named Frances Coles lying beneath a railway arch at Swallow Gardens, Whitechapel. Her throat had been deeply cut but her body was not mutilated, leading some to believe Thompson had disturbed her assailant. Coles was still alive, although she died before medical help could arrive. A 53-year-old stoker,

Both the Whitehall Mystery and the Pinchin Street case may have been part of a series of murders known as the " Thames Mysteries", committed by a single serial killer dubbed the "Torso killer". It is debatable whether Jack the Ripper and the "Torso killer" were the same person or separate serial killers active in the same area.Gordon, R. Michael (2002), ''The Thames Torso Murders of Victorian London'', Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, The ''modus operandi'' of the Torso killer differed from that of the Ripper, and police at the time discounted any connection between the two. Only one of the four victims linked to the Torso killer, Elizabeth Jackson, was ever identified. Jackson was a 24-year-old prostitute from

Both the Whitehall Mystery and the Pinchin Street case may have been part of a series of murders known as the " Thames Mysteries", committed by a single serial killer dubbed the "Torso killer". It is debatable whether Jack the Ripper and the "Torso killer" were the same person or separate serial killers active in the same area.Gordon, R. Michael (2002), ''The Thames Torso Murders of Victorian London'', Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, The ''modus operandi'' of the Torso killer differed from that of the Ripper, and police at the time discounted any connection between the two. Only one of the four victims linked to the Torso killer, Elizabeth Jackson, was ever identified. Jackson was a 24-year-old prostitute from

The vast majority of the City of London Police files relating to their investigation into the Whitechapel murders were destroyed in

The vast majority of the City of London Police files relating to their investigation into the Whitechapel murders were destroyed in

The concentration of the killings around weekends and public holidays and within a short distance of each other has indicated to many that the Ripper was in regular employment and lived locally. Others have opined that the killer was an educated upper-class man, possibly a doctor or an aristocrat who ventured into Whitechapel from a more well-to-do area. Such theories draw on cultural perceptions such as fear of the medical profession, a mistrust of modern science, or the exploitation of the poor by the rich. The term "Ripperology" was coined to describe the study and analysis of the Ripper case in an effort to determine his identity, and the murders have inspired numerous works of fiction.

Suspects proposed years after the murders include virtually anyone remotely connected to the case by contemporaneous documents, as well as many famous names who were never considered in the police investigation, including Prince Albert Victor, artist

The concentration of the killings around weekends and public holidays and within a short distance of each other has indicated to many that the Ripper was in regular employment and lived locally. Others have opined that the killer was an educated upper-class man, possibly a doctor or an aristocrat who ventured into Whitechapel from a more well-to-do area. Such theories draw on cultural perceptions such as fear of the medical profession, a mistrust of modern science, or the exploitation of the poor by the rich. The term "Ripperology" was coined to describe the study and analysis of the Ripper case in an effort to determine his identity, and the murders have inspired numerous works of fiction.

Suspects proposed years after the murders include virtually anyone remotely connected to the case by contemporaneous documents, as well as many famous names who were never considered in the police investigation, including Prince Albert Victor, artist

The "Saucy Jacky" postcard was postmarked 1888 and was received the same day by the Central News Agency. The handwriting was similar to the "Dear Boss" letter, and mentioned the canonical murders committed on 30 September, which the author refers to by writing "double event this time". It has been argued that the postcard was posted before the murders were publicised, making it unlikely that a crank would hold such knowledge of the crime. However, it was postmarked more than 24 hours after the killings occurred, long after details of the murders were known and publicised by journalists, and had become general community gossip by the residents of Whitechapel.Cook, pp. 79–80; Fido, pp. 8–9; Marriott, Trevor, pp. 219–222; Rumbelow, p. 123

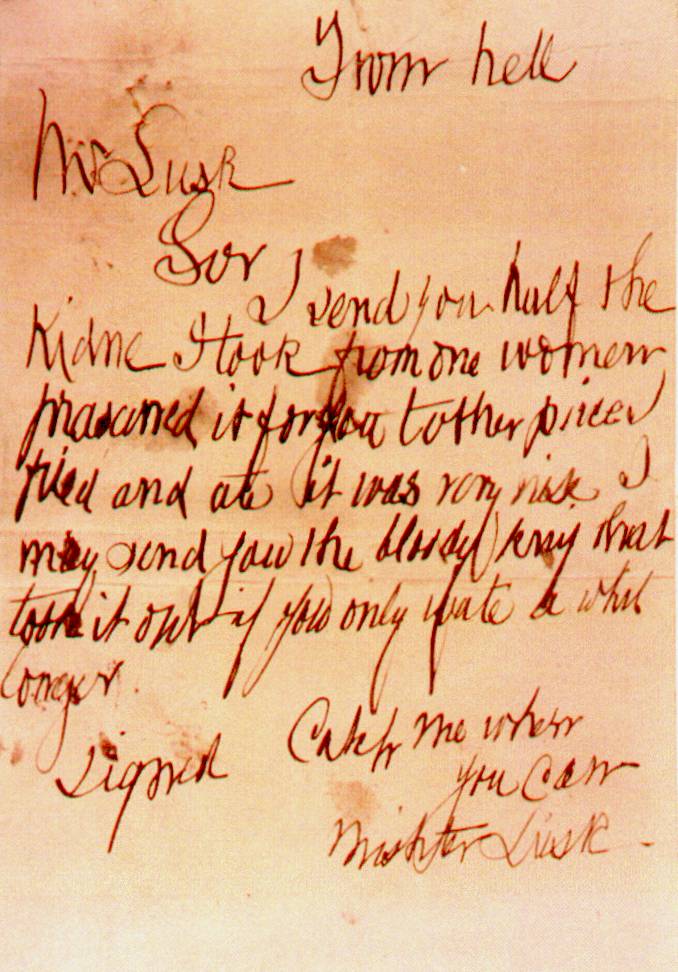

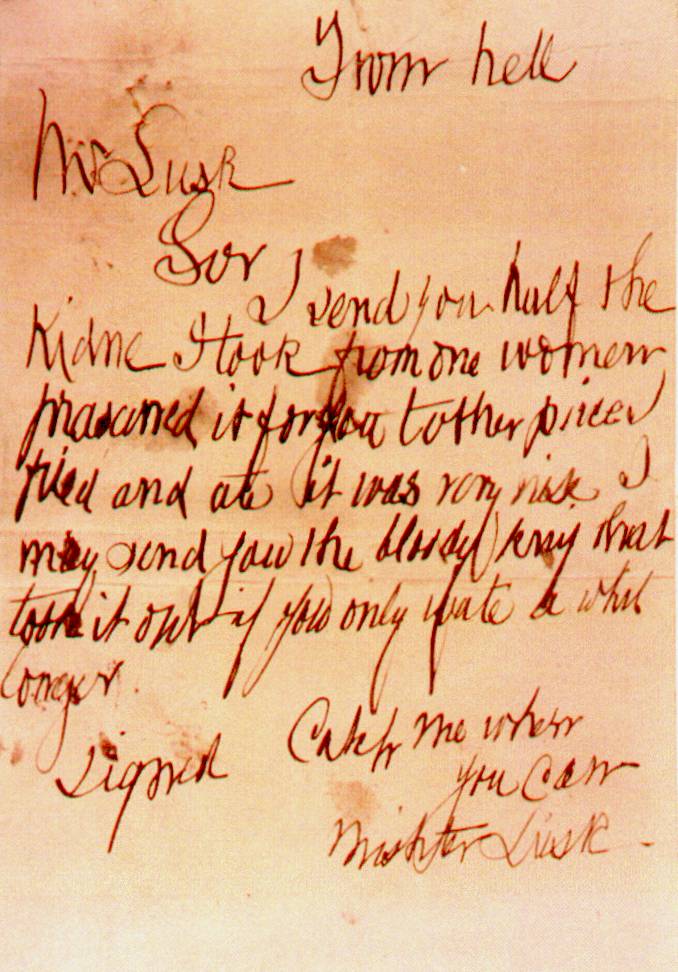

The "From Hell" letter was received by

The "Saucy Jacky" postcard was postmarked 1888 and was received the same day by the Central News Agency. The handwriting was similar to the "Dear Boss" letter, and mentioned the canonical murders committed on 30 September, which the author refers to by writing "double event this time". It has been argued that the postcard was posted before the murders were publicised, making it unlikely that a crank would hold such knowledge of the crime. However, it was postmarked more than 24 hours after the killings occurred, long after details of the murders were known and publicised by journalists, and had become general community gossip by the residents of Whitechapel.Cook, pp. 79–80; Fido, pp. 8–9; Marriott, Trevor, pp. 219–222; Rumbelow, p. 123

The "From Hell" letter was received by

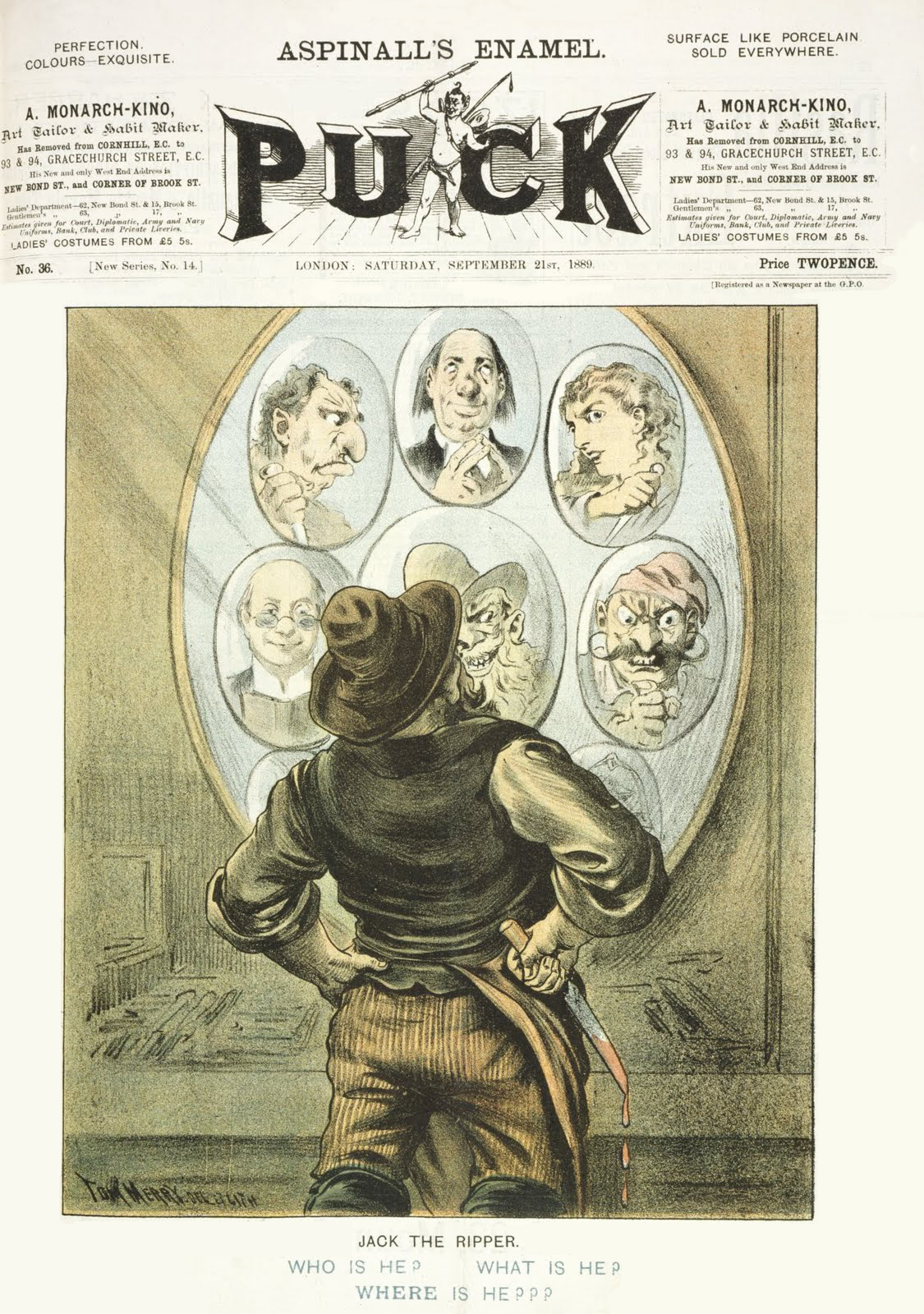

The Ripper murders mark an important watershed in the treatment of crime by journalists. Jack the Ripper was not the first serial killer, but his case was the first to create a worldwide media frenzy. Davenport-Hines, Richard (2004)

The Ripper murders mark an important watershed in the treatment of crime by journalists. Jack the Ripper was not the first serial killer, but his case was the first to create a worldwide media frenzy. Davenport-Hines, Richard (2004)

"Jack the Ripper (fl. 1888)"

, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography''. Oxford University Press. Subscription required for online version.Woods and Baddeley, pp. 20, 52 The

The nature of the Ripper murders and the impoverished lifestyle of the victims drew attention to the poor living conditions in the East End and galvanised public opinion against the overcrowded, insanitary slums. In the two decades after the murders, the worst of the slums were cleared and demolished, but the streets and some buildings survive, and the legend of the Ripper is still promoted by various guided tours of the murder sites and other locations pertaining to the case. For many years, the Ten Bells public house in Commercial Street (which had been frequented by at least one of the canonical Ripper victims) was the focus of such tours.

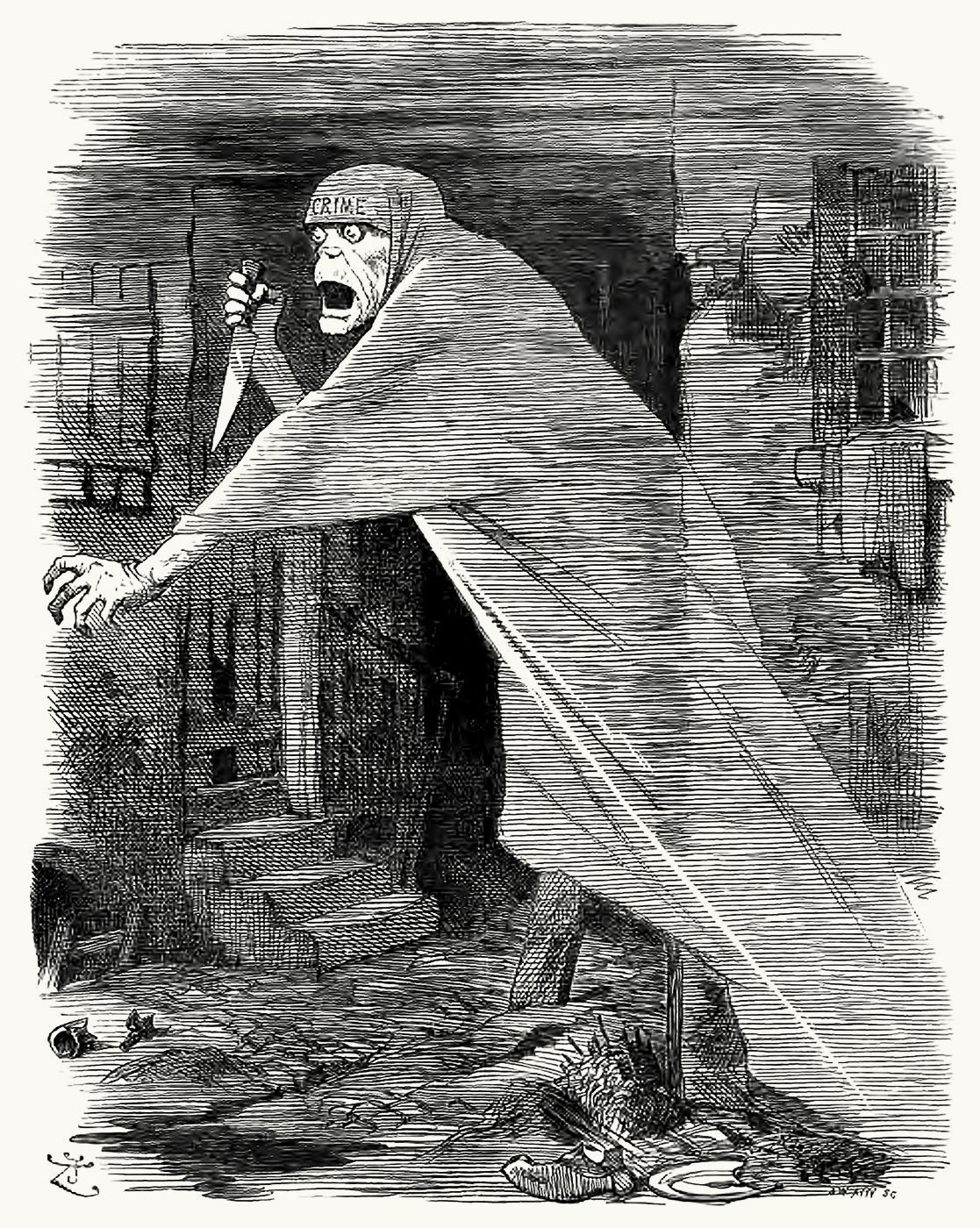

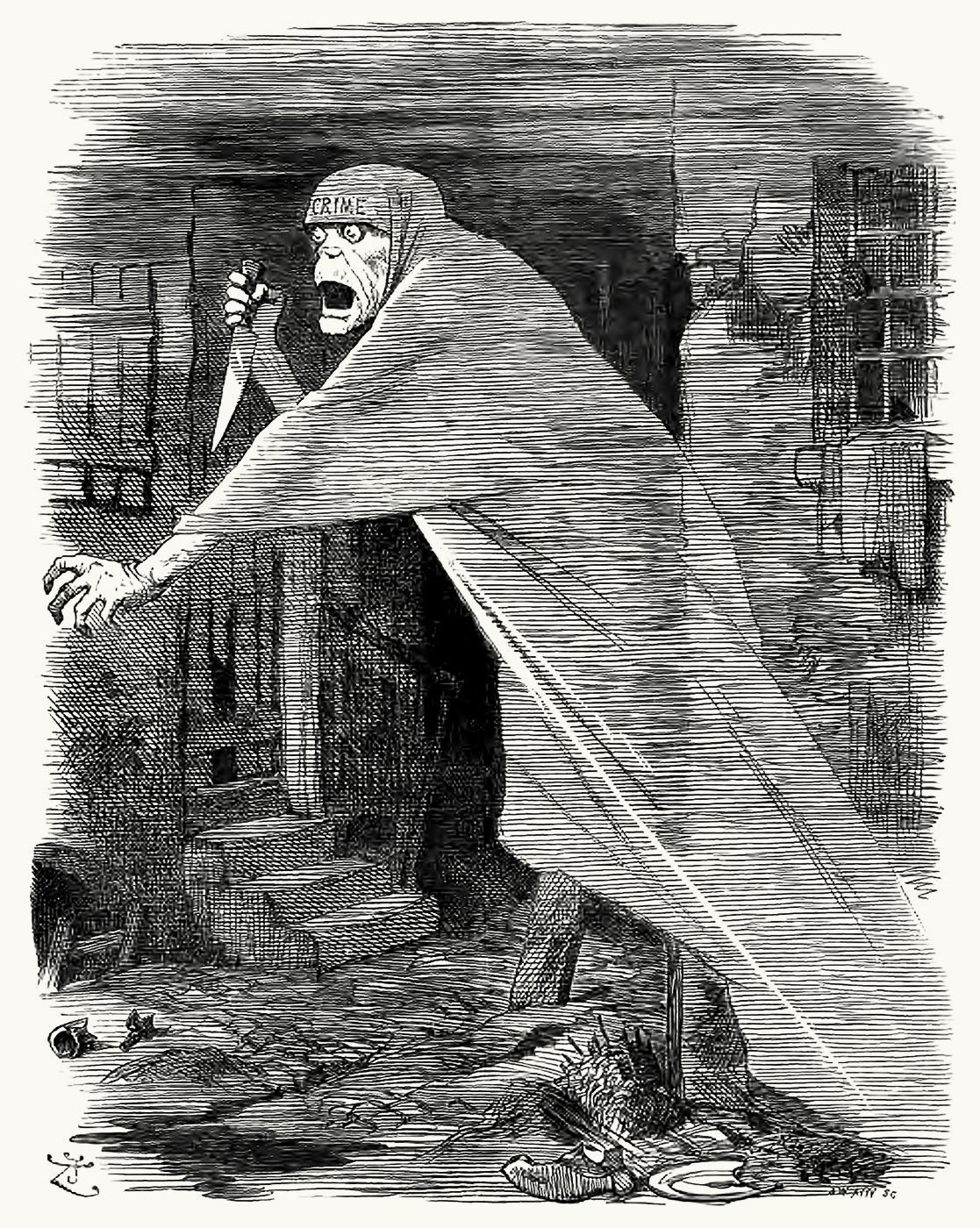

In the immediate aftermath of the murders and later, "Jack the Ripper became the children's bogey man." Depictions were often phantasmic or monstrous. In the 1920s and 1930s, he was depicted in film dressed in everyday clothes as a man with a hidden secret, preying on his unsuspecting victims; atmosphere and evil were suggested through lighting effects and shadowplay. By the 1960s, the Ripper had become "the symbol of a predatory aristocracy",Bloom, Clive, "Jack the Ripper – A Legacy in Pictures", in Werner, p. 251 and was more often portrayed in a top hat dressed as a gentleman.

The nature of the Ripper murders and the impoverished lifestyle of the victims drew attention to the poor living conditions in the East End and galvanised public opinion against the overcrowded, insanitary slums. In the two decades after the murders, the worst of the slums were cleared and demolished, but the streets and some buildings survive, and the legend of the Ripper is still promoted by various guided tours of the murder sites and other locations pertaining to the case. For many years, the Ten Bells public house in Commercial Street (which had been frequented by at least one of the canonical Ripper victims) was the focus of such tours.

In the immediate aftermath of the murders and later, "Jack the Ripper became the children's bogey man." Depictions were often phantasmic or monstrous. In the 1920s and 1930s, he was depicted in film dressed in everyday clothes as a man with a hidden secret, preying on his unsuspecting victims; atmosphere and evil were suggested through lighting effects and shadowplay. By the 1960s, the Ripper had become "the symbol of a predatory aristocracy",Bloom, Clive, "Jack the Ripper – A Legacy in Pictures", in Werner, p. 251 and was more often portrayed in a top hat dressed as a gentleman.

Jack the Ripper

at casebook.org

Home page

of jack-the-ripper.org

Jack the Ripper: The 1888 Autumn of Terror

at whitechapeljack.com

Contemporaneous news article

pertaining to the murders committed by Jack the Ripper * 198

centennial investigation

into the murders committed by Jack the Ripper compiled by the

news article

focusing upon modern

Letters claiming to be from Jack the Ripper

at nationalarchives.gov.uk

Jack the Ripper

at the ''

focusing upon the murders committed by Jack the Ripper

published by the

serial killer

A serial killer is typically a person who murders three or more persons,A

*

*

*

* with the murders taking place over more than a month and including a significant period of time between them. While most authorities set a threshold of three ...

active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a district in East London and the future administrative centre of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is a part of the East End of London, east of Charing Cross. Part of the historic county of Middlesex, the area formed ...

district of London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, England, in the autumn of 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer was called the Whitechapel Murderer and Leather Apron.

Attacks ascribed to Jack the Ripper typically involved female prostitutes who lived and worked in the slums of the East End of London

The East End of London, often referred to within the London area simply as the East End, is the historic core of wider East London, east of the Roman and medieval walls of the City of London and north of the River Thames. It does not have univ ...

. Their throats were cut prior to abdominal mutilations. The removal of internal organs from at least three of the victims led to speculation that their killer had some anatomical or surgical knowledge. Rumours that the murders were connected intensified in September and October 1888, and numerous letters were received by media outlets and Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

from individuals purporting to be the murderer.

The name "Jack the Ripper" originated in the "Dear Boss letter

The "Dear Boss" letter was a message allegedly written by the notorious unidentified Victorian serial killer known as Jack the Ripper. Addressed to the Central News Agency of London and dated 25 September 1888, the letter was postmarked and ...

" written by an individual claiming to be the murderer, which was disseminated in the press. The letter is widely believed to have been a hoax and may have been written by journalists to heighten interest in the story and increase their newspapers' circulation. The "From Hell letter

The "From Hell" letter (also known as the "Lusk letter") was a letter sent alongside half of a preserved human kidney to George Lusk, the chairman of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, in October 1888. The author of this letter claimed to be t ...

" received by George Lusk

George Akin Lusk (1839–1919) was a British builder and decorator who specialised in music hall restoration, and was the chairman of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee during the Whitechapel murders, including the killings ascribed to Jack t ...

of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee

The Whitechapel Vigilance Committee was a group of local civilian volunteers who patrolled the streets of London's Whitechapel district during the period of the Whitechapel murders of 1888. The volunteers were active mainly at night, assisting th ...

came with half of a preserved human kidney, purportedly taken from one of the victims. The public came increasingly to believe in the existence of a single serial killer known as Jack the Ripper, mainly because of both the extraordinarily brutal nature of the murders and media coverage of the crimes.

Extensive newspaper coverage bestowed widespread and enduring international notoriety on the Ripper, and the legend solidified. A police investigation into a series of eleven brutal murders committed in Whitechapel and Spitalfields

Spitalfields is a district in the East End of London and within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. The area is formed around Commercial Street (on the A1202 London Inner Ring Road) and includes the locale around Brick Lane, Christ Church, ...

between 1888 and 1891 was unable to connect all the killings conclusively to the murders of 1888. Five victims— Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman

Annie Chapman (born Eliza Ann Smith; 25 September 1840 – 8 September 1888) was the second canonical victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilated a minimum of five women in the Whitechapel and S ...

, Elizabeth Stride

Elizabeth "Long Liz" Stride ( Gustafsdotter; 27 November 1843 – 30 September 1888) is believed to have been the third victim of the unidentified serial killer known as Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilated at least five women in the Whitech ...

, Catherine Eddowes

Catherine Eddowes (14 April 1842 – 30 September 1888) was the fourth of the canonical five victims of the notorious unidentified serial killer known as Jack the Ripper, who is believed to have killed and mutilated a minimum of five women in ...

, and Mary Jane Kelly

Mary Jane Kelly ( – 9 November 1888), also known as Marie Jeanette Kelly, Fair Emma, Ginger, Dark Mary and Black Mary, is widely believed to have been the final victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who murdered ...

—are known as the "canonical five" and their murders between 31 August and 9 November 1888 are often considered the most likely to be linked. The murders were never solved, and the legends surrounding these crimes became a combination of historical research, folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, rangin ...

, and pseudohistory

Pseudohistory is a form of pseudoscholarship that attempts to distort or misrepresent the historical record, often by employing methods resembling those used in scholarly historical research. The related term cryptohistory is applied to pseudohi ...

, capturing public imagination to the present day.

Background

In the mid-19th century, England experienced an influx of

In the mid-19th century, England experienced an influx of Irish immigrants

The Irish diaspora ( ga, Diaspóra na nGael) refers to ethnic Irish people and their descendants who live outside the island of Ireland.

The phenomenon of migration from Ireland is recorded since the Early Middle Ages,Flechner and Meeder, The ...

who swelled the populations of the major cities, including the East End of London

The East End of London, often referred to within the London area simply as the East End, is the historic core of wider East London, east of the Roman and medieval walls of the City of London and north of the River Thames. It does not have univ ...

. From 1882, Jewish refugees fleeing pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

s in Tsarist Russia and other areas of Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

emigrated into the same area. The parish of Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a district in East London and the future administrative centre of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is a part of the East End of London, east of Charing Cross. Part of the historic county of Middlesex, the area formed ...

in the East End became increasingly overcrowded, with the population increasing to approximately 80,000 inhabitants by 1888.Honeycombe, ''The Murders of the Black Museum: 1870-1970'', p. 54 Work and housing conditions worsened, and a significant economic underclass developed. Fifty-five percent of children born in the East End died before they were five years old. Robbery, violence, and alcohol dependency

Alcohol dependence is a previous (DSM-IV and ICD-10) psychiatric diagnosis in which an individual is physically or psychologically dependent upon alcohol (also chemically known as ethanol).

In 2013, it was reclassified as alcohol use disorder ...

were commonplace, and the endemic poverty drove many women to prostitution

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in Sex work, sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, n ...

to survive on a daily basis.

In October 1888, London's Metropolitan Police Service

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), formerly and still commonly known as the Metropolitan Police (and informally as the Met Police, the Met, Scotland Yard, or the Yard), is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement and ...

estimated that there were 62 brothel

A brothel, bordello, ranch, or whorehouse is a place where people engage in sexual activity with prostitutes. However, for legal or cultural reasons, establishments often describe themselves as massage parlors, bars, strip clubs, body rub p ...

s and 1,200 women working as prostitutes in Whitechapel,Evans and Skinner, ''Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell'', p. 1; Police report dated 25 October 1888, MEPO 3/141 ff. 158–163, quoted in Evans and Skinner, ''The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook'', p. 283; Fido, p. 82; Rumbelow, p. 12 with approximately 8,500 people residing in the 233 common lodging-house

"Common lodging-house" is a Victorian era term for a form of cheap accommodation in which inhabitants are lodged together in one or more rooms in common with the rest of the lodgers, who are not members of one family, whether for eating or sleepin ...

s within Whitechapel every night, with the nightly price for a single bed being fourpence

The groat is the traditional name of a defunct English and Irish silver coin worth four pence, and also a Scottish coin which was originally worth fourpence, with later issues being valued at eightpence and one shilling.

Name

The name has also ...

and the cost of sleeping upon a "lean-to" (" hang-over") rope stretched across the dormitory being two pence per person.

The economic problems in Whitechapel were accompanied by a steady rise in social tension

Civil disorder, also known as civil disturbance, civil unrest, or social unrest is a situation arising from a mass act of civil disobedience (such as a demonstration, riot, strike, or unlawful assembly) in which law enforcement has difficulty ...

s. Between 1886 and 1889, frequent demonstrations led to police intervention and public unrest, such as Bloody Sunday (1887)

Bloody Sunday took place in London on 13 November 1887, when marchers protesting about unemployment and coercion in Ireland, as well as demanding the release of MP William O'Brien, clashed with the Metropolitan Police and the British Army. ...

. Anti-semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

, crime, nativism, racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagoni ...

, social disturbance, and severe deprivation influenced public perceptions that Whitechapel was a notorious den of immorality

Immorality is the violation of moral laws, norms or standards. It refers to an agent doing or thinking something they know or believe to be wrong. Immorality is normally applied to people or actions, or in a broader sense, it can be applied to ...

. Such perceptions were strengthened in the autumn of 1888 when the series of vicious and grotesque murders attributed to "Jack the Ripper" received unprecedented coverage in the media.

Murders

modus operandi

A ''modus operandi'' (often shortened to M.O.) is someone's habits of working, particularly in the context of business or criminal investigations, but also more generally. It is a Latin phrase, approximately translated as "mode (or manner) of o ...

''. The first two cases in the Whitechapel murders file, those of Emma Elizabeth Smith

Emma Elizabeth Smith ( 1843 – 4 April 1888) was a prostitute and murder victim of mysterious origins in late-19th century London. Her killing was the first of the Whitechapel murders, and it is possible she was a victim of the serial killer kno ...

and Martha Tabram

Martha Tabram (née White; 10 May 1849 – 7 August 1888) was an English woman killed in a spate of violent murders in and around the Whitechapel district of East London between 1888 and 1891. She may have been the first victim of the still-unid ...

, are not included in the canonical five.

Smith was robbed and sexually assaulted

Sexual assault is an act in which one intentionally sexually touches another person without that person's consent, or coerces or physically forces a person to engage in a sexual act against their will. It is a form of sexual violence, whic ...

in Osborn Street Osborn may refer to:

* Osborn (surname)

* Osborn Engineering, American architectural and engineering firm

* Osborn Engineering Company, British motorcycle manufacturer

* Osborn wave, an abnormal electrocardiogram finding

Places in the United State ...

, Whitechapel, at approximately on 1888. She had been bludgeoned about the face and received a cut to her ear. A blunt object was also inserted into her vagina

In mammals, the vagina is the elastic, muscular part of the female genital tract. In humans, it extends from the vestibule to the cervix. The outer vaginal opening is normally partly covered by a thin layer of mucosal tissue called the hymen ...

, rupturing her peritoneum

The peritoneum is the serous membrane forming the lining of the abdominal cavity or coelom in amniotes and some invertebrates, such as annelids. It covers most of the intra-abdominal (or coelomic) organs, and is composed of a layer of mes ...

. She developed peritonitis

Peritonitis is inflammation of the localized or generalized peritoneum, the lining of the inner wall of the abdomen and cover of the abdominal organs. Symptoms may include severe pain, swelling of the abdomen, fever, or weight loss. One part o ...

and died the following day at London Hospital

The Royal London Hospital is a large teaching hospital in Whitechapel in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is part of Barts Health NHS Trust. It provides district general hospital services for the City of London and Tower Hamlets and sp ...

. Smith stated that she had been attacked by two or three men, one of whom she described as a teenager. This attack was linked to the later murders by the press, but most authors attribute Smith's murder to general East End gang violence

A gang is a group or society of associates, friends or members of a family with a defined leadership and internal organization that identifies with or claims control over territory in a community and engages, either individually or collective ...

unrelated to the Ripper case.

Tabram was murdered on a staircase landing in George Yard, Whitechapel, on 7 August 1888;Begg, ''Jack the Ripper: The Facts'', p. 35 she had suffered 39 stab wounds to her throat, lungs, heart, liver, spleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes .

, stomach, and abdomen, with additional knife wounds inflicted to her breasts and vagina. All but one of Tabram's wounds had been inflicted with a bladed instrument such as a penknife

Penknife, or pen knife, is a British English term for a small folding knife. Today the word ''penknife'' is the common British English term for both a pocketknife, which can have single or multiple blades, and for multi-tools, with additional too ...

, and with one possible exception, all the wounds had been inflicted by a right-handed individual. Tabram had not been rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ...

d.

The savagery of the Tabram murder, the lack of an obvious motive

Motive(s) or The Motive(s) may refer to:

* Motive (law)

Film and television

* ''Motives'' (film), a 2004 thriller

* ''The Motive'' (film), 2017

* ''Motive'' (TV series), a 2013 Canadian TV series

* ''The Motive'' (TV series), a 2020 Israeli T ...

, and the closeness of the location and date to the later canonical Ripper murders led police to link this murder to those later committed by Jack the Ripper. However, this murder differs from the later canonical murders because although Tabram had been repeatedly stabbed, she had not suffered any slash wounds to her throat or abdomen. Many experts do not connect Tabram's murder with the later murders because of this difference in the wound pattern.

Canonical five

Thecanonical

The adjective canonical is applied in many contexts to mean "according to the canon" the standard, rule or primary source that is accepted as authoritative for the body of knowledge or literature in that context. In mathematics, "canonical examp ...

five Ripper victims are Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman

Annie Chapman (born Eliza Ann Smith; 25 September 1840 – 8 September 1888) was the second canonical victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilated a minimum of five women in the Whitechapel and S ...

, Elizabeth Stride

Elizabeth "Long Liz" Stride ( Gustafsdotter; 27 November 1843 – 30 September 1888) is believed to have been the third victim of the unidentified serial killer known as Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilated at least five women in the Whitech ...

, Catherine Eddowes

Catherine Eddowes (14 April 1842 – 30 September 1888) was the fourth of the canonical five victims of the notorious unidentified serial killer known as Jack the Ripper, who is believed to have killed and mutilated a minimum of five women in ...

, and Mary Jane Kelly

Mary Jane Kelly ( – 9 November 1888), also known as Marie Jeanette Kelly, Fair Emma, Ginger, Dark Mary and Black Mary, is widely believed to have been the final victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who murdered ...

.

The body of Mary Ann Nichols was discovered at about on Friday 1888 in Buck's Row (now Durward Street), Whitechapel. Nichols had last been seen alive approximately one hour before the discovery of her body by a Mrs Emily Holland, with whom she had previously shared a bed at a common lodging-house in Thrawl Street, Spitalfields, walking in the direction of Whitechapel Road

Whitechapel Road is a major arterial road in Whitechapel, Tower Hamlets, in the East End of London. It is named after a small chapel of ease dedicated to St Mary and connects Whitechapel High Street to the west with Mile End Road to the east. ...

. Her throat was severed by two deep cuts, one of which completely severed all the tissue down to the vertebra

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristi ...

e. Her vagina had been stabbed twice, and the lower part of her abdomen was partly ripped open by a deep, jagged wound, causing her bowels to protrude. Several other incisions inflicted to both sides of her abdomen had also been caused by the same knife; each of these wounds had been inflicted in a downward thrusting manner.

One week later, on Saturday 1888, the body of Annie Chapman was discovered at approximately near the steps to the doorway of the back yard of 29

One week later, on Saturday 1888, the body of Annie Chapman was discovered at approximately near the steps to the doorway of the back yard of 29 Hanbury Street

Hanbury Street is a street running from Spitalfields to Whitechapel, London Borough of Tower Hamlets, in the East End of London. It runs east from Commercial Street to the junction of Old Montague Street and Vallance Road at the east end. The e ...

, Spitalfields. As in the case of Nichols, the throat was severed by two deep cuts. Her abdomen had been cut entirely open, with a section of the flesh from her stomach being placed upon her left shoulder and another section of skin and flesh—plus her small intestine

The small intestine or small bowel is an organ (anatomy), organ in the human gastrointestinal tract, gastrointestinal tract where most of the #Absorption, absorption of nutrients from food takes place. It lies between the stomach and large intes ...

s—being removed and placed above her right shoulder. Chapman's autopsy also revealed that her uterus

The uterus (from Latin ''uterus'', plural ''uteri'') or womb () is the organ in the reproductive system of most female mammals, including humans that accommodates the embryonic and fetal development of one or more embryos until birth. The ...

and sections of her bladder

The urinary bladder, or simply bladder, is a hollow organ in humans and other vertebrates that stores urine from the kidneys before disposal by urination. In humans the bladder is a distensible organ that sits on the pelvic floor. Urine en ...

and vagina had been removed.

At the inquest

An inquest is a judicial inquiry in common law jurisdictions, particularly one held to determine the cause of a person's death. Conducted by a judge, jury, or government official, an inquest may or may not require an autopsy carried out by a c ...

into Chapman's murder, Elizabeth Long described having seen Chapman standing outside 29 Hanbury Street at about in the company of a dark-haired man wearing a brown deer-stalker hat and dark overcoat, and of a "shabby-genteel

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest co ...

" appearance. According to this eyewitness, the man had asked Chapman the question, "Will you?" to which Chapman had replied, "Yes."

Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes were both killed in the early morning hours of Sunday 1888. Stride's body was discovered at approximately in Dutfield's Yard, off Berner Street (now Henriques Street

The Whitechapel murders were committed in or near the largely impoverished Whitechapel district in the East End of London between 3 April 1888 and 13 February 1891. At various points some or all of these eleven unsolved murders of women have ...

) in Whitechapel. The cause of death was a single clear-cut incision, measuring six inches across her neck which had severed her left carotid artery Carotid artery may refer to:

* Common carotid artery, often "carotids" or "carotid", an artery on each side of the neck which divides into the external carotid artery and internal carotid artery

* External carotid artery, an artery on each side of ...

and her trachea

The trachea, also known as the windpipe, is a cartilaginous tube that connects the larynx to the bronchi of the lungs, allowing the passage of air, and so is present in almost all air- breathing animals with lungs. The trachea extends from t ...

before terminating beneath her right jaw. The absence of any further mutilations to her body has led to uncertainty as to whether Stride's murder was committed by the Ripper, or whether he was interrupted during the attack. Several witnesses later informed police they had seen Stride in the company of a man in or close to Berner Street on the evening of 29 September and in the early hours of 30 September, but each gave differing descriptions: some said that her companion was fair, others dark; some said that he was shabbily dressed, others well-dressed.

Eddowes's body was found in a corner of

Eddowes's body was found in a corner of Mitre Square

Mitre Square is a small square in the City of London. It measures about by and is connected via three passages with Mitre Street to the south west, to Creechurch Place to the north west and, via St James's Passage (formerly Church Passage), t ...

in the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

, three-quarters of an hour after the discovery of the body of Elizabeth Stride. Her throat was severed from ear to ear and her abdomen ripped open by a long, deep and jagged wound before her intestines had been placed over her right shoulder, with a section of intestine being completely detached and placed between her body and left arm.

The left kidney and the major part of Eddowes's uterus had been removed, and her face had been disfigured, with her nose severed, her cheek slashed, and cuts measuring a quarter of an inch and a half an inch respectively vertically incised through each of her eyelids. A triangular incision—the apex

The apex is the highest point of something. The word may also refer to:

Arts and media Fictional entities

* Apex (comics), a teenaged super villainess in the Marvel Universe

* Ape-X, a super-intelligent ape in the Squadron Supreme universe

*Apex, ...

of which pointed towards Eddowes's eye—had also been carved upon each of her cheeks, and a section of the auricle and lobe

Lobe may refer to:

People with the name

* Lobe (surname)

Science and healthcare

* Lobe (anatomy)

* Lobe, a large-scale structure of a radio galaxy

* Glacial lobe, a lobe-shaped glacier

* Lobation, a characteristic of the nucleus of certain biolo ...

of her right ear was later recovered from her clothing. The police surgeon who conducted the post mortem

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough Physical examination, examination of a Cadaver, corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner o ...

upon Eddowes's body stated his opinion these mutilations would have taken "at least five minutes" to complete.

A local cigarette salesman named Joseph Lawende had passed through the square with two friends shortly before the murder, and he described seeing a fair-haired man of shabby appearance with a woman who may have been Eddowes. Lawende's companions were unable to confirm his description.Begg, ''Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History'', pp. 193–194; Chief Inspector Swanson's report, 1888, HO 144/221/A49301C, quoted in Evans and Skinner, pp. 185–188 The murders of Stride and Eddowes ultimately became known as the "double event".

A section of Eddowes's bloodied apron was found at the entrance to a tenement in Goulston Street, Whitechapel, at A chalk inscription upon the wall directly above this piece of apron read: "The Juwes are The men That Will not be Blamed for nothing." This graffito became known as the Goulston Street graffito

The Goulston Street graffito was a sentence written on a wall beside a clue in the 1888 Whitechapel murders investigation. It has been transcribed as variations on the sentence "The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing". The mean ...

. The message appeared to imply that a Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

or Jews in general were responsible for the series of murders, but it is unclear whether the graffito was written by the murderer on dropping the section of apron, or was merely incidental and nothing to do with the case. Such graffiti were commonplace in Whitechapel. Police Commissioner Charles Warren

General Sir Charles Warren, (7 February 1840 – 21 January 1927) was an officer in the British Royal Engineers. He was one of the earliest European archaeologists of the Biblical Holy Land, and particularly of the Temple Mount. Much of his mi ...

feared that the graffito might spark anti-semitic riots and ordered the writing washed away before dawn.

The extensively mutilated and disembowelled

Disembowelment or evisceration is the removal of some or all of the organs of the gastrointestinal tract (the bowels, or viscera), usually through a horizontal incision made across the abdominal area. Disembowelment may result from an accident ...

body of Mary Jane Kelly was discovered lying on the bed in the single room where she lived at 13 Miller's Court, off Dorset Street, Spitalfields, at on Friday 1888. Her face had been "hacked beyond all recognition", with her throat severed down to the spine, and the abdomen almost emptied of its organs. Her uterus, kidneys and one breast had been placed beneath her head, and other viscera

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a f ...

from her body placed beside her foot, about the bed and sections of her abdomen and thighs upon a bedside table. The heart was missing from the crime scene.

Multiple ashes found within the fireplace at 13 Miller's Court suggested Kelly's murderer had burned several combustible items to illuminate the single room as he mutilated her body. A recent fire had been severe enough to melt the solder

Solder (; NA: ) is a fusible metal alloy used to create a permanent bond between metal workpieces. Solder is melted in order to wet the parts of the joint, where it adheres to and connects the pieces after cooling. Metals or alloys suitable ...

between a kettle and its spout, which had fallen into the grate of the fireplace.

Each of the canonical five murders was perpetrated at night, on or close to a weekend, either at the end of a month or a week (or so) after. The mutilations became increasingly severe as the series of murders proceeded, except for that of Stride, whose attacker may have been interrupted. Nichols was not missing any organs; Chapman's uterus and sections of her bladder and vagina were taken; Eddowes had her uterus and left kidney removed and her face mutilated; and Kelly's body was extensively eviscerated, with her face "gashed in all directions" and the tissue of her neck being severed to the bone, although the heart was the sole body organ missing from this crime scene.

Historically, the belief these five canonical murders were committed by the same perpetrator is derived from contemporaneous documents which link them together to the exclusion of others. In 1894, Sir

Each of the canonical five murders was perpetrated at night, on or close to a weekend, either at the end of a month or a week (or so) after. The mutilations became increasingly severe as the series of murders proceeded, except for that of Stride, whose attacker may have been interrupted. Nichols was not missing any organs; Chapman's uterus and sections of her bladder and vagina were taken; Eddowes had her uterus and left kidney removed and her face mutilated; and Kelly's body was extensively eviscerated, with her face "gashed in all directions" and the tissue of her neck being severed to the bone, although the heart was the sole body organ missing from this crime scene.

Historically, the belief these five canonical murders were committed by the same perpetrator is derived from contemporaneous documents which link them together to the exclusion of others. In 1894, Sir Melville Macnaghten

Sir Melville Leslie Macnaghten (16 June 1853, Woodford, London −12 May 1921) was Assistant Commissioner (Crime) of the London Metropolitan Police from 1903 to 1913. A highly regarded and famously affable figure of the late Victorian and Edw ...

, Assistant Chief Constable of the Metropolitan Police Service

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), formerly and still commonly known as the Metropolitan Police (and informally as the Met Police, the Met, Scotland Yard, or the Yard), is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement and ...

and Head of the Criminal Investigation Department

The Criminal Investigation Department (CID) is the branch of a police force to which most plainclothes detectives belong in the United Kingdom and many Commonwealth nations. A force's CID is distinct from its Special Branch (though officers of b ...

(CID), wrote a report that stated: "the Whitechapel murderer had 5 victims—& 5 victims only". Similarly, the canonical five victims were linked together in a letter written by police surgeon Thomas Bond to Robert Anderson, head of the London CID, on 1888.

Some researchers have posited that some of the murders were undoubtedly the work of a single killer, but an unknown larger number of killers acting independently were responsible for the other crimes. Authors Stewart P. Evans and Donald Rumbelow

Donald Rumbelow (born 1940) is a British former City of London Police officer, crime historian, and ex-curator of the City of London Police's Crime Museum. He has twice been chairman of England's Crime Writers' Association.

Career

A recognised aut ...

argue that the canonical five is a "Ripper myth" and that three cases (Nichols, Chapman, and Eddowes) can be definitely linked to the same perpetrator, but that less certainty exists as to whether Stride and Kelly were also murdered by the same individual. Conversely, others suppose that the six murders between Tabram and Kelly were the work of a single killer. Dr Percy Clark, assistant to the examining pathologist

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in t ...

George Bagster Phillips

George Bagster Phillips (February 1835 in Camberwell, Surrey – 27 October 1897 in London) was, from 1865, the Police Surgeon for the Metropolitan Police's 'H' Division, which covered London's Whitechapel district. He came to prominence d ...

, linked only three of the murders and thought that the others were perpetrated by "weak-minded individual nbsp;... induced to emulate the crime". Macnaghten did not join the police force until the year after the murders, and his memorandum contains serious factual errors about possible suspects.

Later Whitechapel murders

Mary Jane Kelly is generally considered to be the Ripper's final victim, and it is assumed that the crimes ended because of the culprit's death, imprisonment,institutionalisation

In sociology, institutionalisation (or institutionalization) is the process of embedding some conception (for example a belief, norm, social role, particular value or mode of behavior) within an organization, social system, or society as a who ...

, or emigration. The Whitechapel murders file details another four murders that occurred after the canonical five: those of Rose Mylett, Alice McKenzie, the Pinchin Street torso, and Frances Coles.

The strangled body of 26-year-old Rose Mylett was found in Clarke's Yard, High Street, Poplar on 1888. There was no sign of a struggle, and the police believed that she had either accidentally hanged herself with her collar while in a drunken stupor or committed suicide. However, faint markings left by a cord on one side of her neck suggested Mylett had been strangled. At the inquest into Mylett's death, the jury returned a verdict of murder.Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 245–246; Evans and Skinner, ''The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook'', pp. 422–439

Alice McKenzie was murdered shortly after midnight on 17 July 1889 in Castle Alley, Whitechapel. She had suffered two stab wounds to her neck, and her left carotid artery had been severed. Several minor bruises and cuts were found on her body, which also bore a seven-inch long superficial wound extending from her left breast to her navel

The navel (clinically known as the umbilicus, commonly known as the belly button or tummy button) is a protruding, flat, or hollowed area on the abdomen at the attachment site of the umbilical cord. All placental mammals have a navel, although ...

. One of the examining pathologists, Thomas Bond, believed this to be a Ripper murder, though his colleague George Bagster Phillips, who had examined the bodies of three previous victims, disagreed. Opinions among writers are also divided between those who suspect McKenzie's murderer copied the ''modus operandi'' of Jack the Ripper to deflect suspicion from himself, and those who ascribe this murder to Jack the Ripper.

"The Pinchin Street torso" was a decomposing headless and legless torso of an unidentified woman aged between 30 and 40 discovered beneath a railway arch in Pinchin Street, Whitechapel, on 1889. Bruising about the victim's back, hip, and arm indicated the decedent had been extensively beaten shortly before her death. The victim's abdomen was also extensively mutilated, although her genitals had not been wounded. She appeared to have been killed approximately one day prior to the discovery of her torso. The dismembered sections of the body are believed to have been transported to the railway arch, hidden under an old chemise.

At on 13 February 1891, PC Ernest Thompson discovered a 25-year-old prostitute named Frances Coles lying beneath a railway arch at Swallow Gardens, Whitechapel. Her throat had been deeply cut but her body was not mutilated, leading some to believe Thompson had disturbed her assailant. Coles was still alive, although she died before medical help could arrive. A 53-year-old stoker,

At on 13 February 1891, PC Ernest Thompson discovered a 25-year-old prostitute named Frances Coles lying beneath a railway arch at Swallow Gardens, Whitechapel. Her throat had been deeply cut but her body was not mutilated, leading some to believe Thompson had disturbed her assailant. Coles was still alive, although she died before medical help could arrive. A 53-year-old stoker, James Thomas Sadler

James Thomas Sadler (c. 1837 — 1906 or 1910), also named Saddler in some sources, was an English merchant sailor who officiated interchangeably as a machinist and stoker. In 1891, the then-53-year-old was accused of killing prostitute Frances ...

, had earlier been seen drinking with Coles, and the two are known to have argued approximately three hours before her death. Sadler was arrested by the police and charged with her murder. He was briefly thought to be the Ripper, but was later discharged from court for lack of evidence on 1891.Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 218–222; Evans and Skinner, ''The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook'', pp. 551–568

Other alleged victims

In addition to the eleven Whitechapel murders, commentators have linked other attacks to the Ripper. In the case of "Fairy Fay", it is unclear whether this attack was real or fabricated as a part of Ripper lore.Evans, Stewart P.; Connell, Nicholas (2000). ''The Man Who Hunted Jack the Ripper''. "Fairy Fay" was a nickname given to an unidentified woman whose body was allegedly found in a doorway close to Commercial Road on 1887 "after a stake had been thrust through her abdomen", but there were no recorded murders in Whitechapel at or around Christmas 1887. "Fairy Fay" seems to have been created through a confused press report of the murder of Emma Elizabeth Smith, who had a stick or other blunt object shoved into her vagina. Most authors agree that the victim "Fairy Fay" never existed.Begg, ''Jack the Ripper: The Facts'', pp. 21–25 A 38-year-old widow named Annie Millwood was admitted to the Whitechapel Workhouse Infirmary with numerous stab wounds to her legs and lower torso on 1888, informing staff she had been attacked with a clasp knife by an unknown man. She was later discharged, but died from apparently natural causes on . Millwood was later postulated to be the Ripper's first victim, although this attack cannot be definitively linked to the perpetrator. Another suspected precanonical victim was a young dressmaker named Ada Wilson, who reportedly survived being stabbed twice in the neck with a clasp knife upon the doorstep of her home in Bow on 1888. A further possible victim, 40-year-old Annie Farmer, resided at the same lodging house as Martha Tabram and reported an attack on 1888. She had received a superficial cut to her throat. Although an unknown man with blood on his mouth and hands had run out of this lodging house, shouting, "Look at what she has done!" before two eyewitnesses heard Farmer scream, her wound was light, and possiblyself-inflicted

Self-Inflicted is the 8th album by Leæther Strip

Leæther Strip is a Danish musical project founded on 13 January 1988 by Claus Larsen. Its influence has been most felt in the electronic body music and electro-industrial genres. Leæther St ...

.

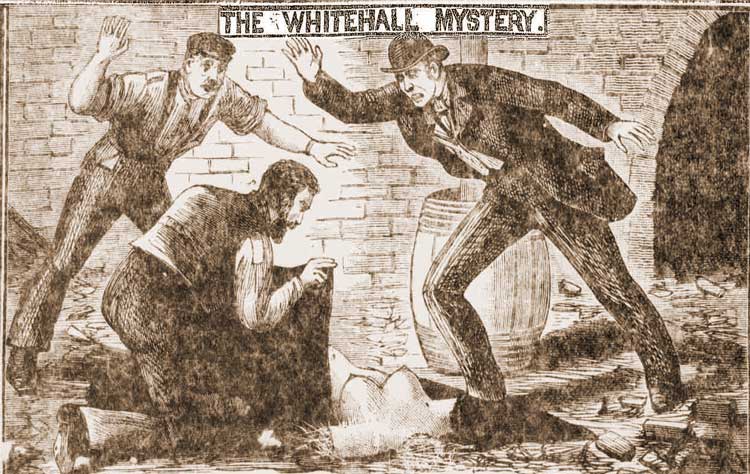

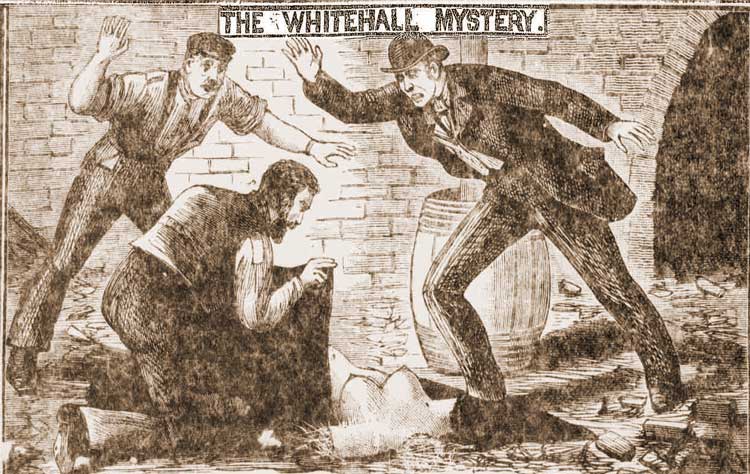

"The Whitehall Mystery

The Whitehall Mystery is an unsolved murder that took place in London in 1888. The dismembered remains of a woman were discovered at three sites in the centre of the city, including the construction site of Scotland Yard, the police headquarters ...

" was a term coined for the discovery of a headless torso of a woman on 1888 in the basement of the new Metropolitan Police headquarters being built in Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea. It is the main thoroughfare running south from Trafalgar Square towards Parliament Sq ...

. An arm and shoulder belonging to the body were previously discovered floating in the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

near Pimlico on 11 September, and the left leg was subsequently discovered buried near where the torso was found on 17 October. The other limbs and head were never recovered and the body was never identified. The mutilations were similar to those in the Pinchin Street torso case, where the legs and head were severed but not the arms.

Both the Whitehall Mystery and the Pinchin Street case may have been part of a series of murders known as the " Thames Mysteries", committed by a single serial killer dubbed the "Torso killer". It is debatable whether Jack the Ripper and the "Torso killer" were the same person or separate serial killers active in the same area.Gordon, R. Michael (2002), ''The Thames Torso Murders of Victorian London'', Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, The ''modus operandi'' of the Torso killer differed from that of the Ripper, and police at the time discounted any connection between the two. Only one of the four victims linked to the Torso killer, Elizabeth Jackson, was ever identified. Jackson was a 24-year-old prostitute from

Both the Whitehall Mystery and the Pinchin Street case may have been part of a series of murders known as the " Thames Mysteries", committed by a single serial killer dubbed the "Torso killer". It is debatable whether Jack the Ripper and the "Torso killer" were the same person or separate serial killers active in the same area.Gordon, R. Michael (2002), ''The Thames Torso Murders of Victorian London'', Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, The ''modus operandi'' of the Torso killer differed from that of the Ripper, and police at the time discounted any connection between the two. Only one of the four victims linked to the Torso killer, Elizabeth Jackson, was ever identified. Jackson was a 24-year-old prostitute from Chelsea

Chelsea or Chelsey may refer to:

Places Australia

* Chelsea, Victoria

Canada

* Chelsea, Nova Scotia

* Chelsea, Quebec

United Kingdom

* Chelsea, London, an area of London, bounded to the south by the River Thames

** Chelsea (UK Parliament consti ...

whose various body parts were collected from the River Thames over a three-week period between 31 May and 25 June 1889.

On 1888, the body of a seven-year-old boy named John Gill was found in a stable block in Manningham, Bradford. Gill had been missing since 27 December. His legs had been severed, his abdomen opened, his intestines partly drawn out, and his heart and one ear removed. Similarities with the Ripper murders led to press speculation that the Ripper had killed him. The boy's employer, 23-year-old milkman William Barrett, was twice arrested for the murder but was released due to insufficient evidence. No-one was ever prosecuted.Evans and Skinner, ''Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell'', p. 136

Carrie Brown (nicknamed "Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

", reportedly for her habit of quoting Shakespeare's sonnets

A sonnet is a poetic form that originated in the poetry composed at the Court of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in the Sicilian city of Palermo. The 13th-century poet and notary Giacomo da Lentini is credited with the sonnet's inventio ...

) was strangled with clothing and then mutilated with a knife on 1891 in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

. Her body was found with a large tear through her groin area and superficial cuts on her legs and back. No organs were removed from the scene, though an ovary was found upon the bed, either purposely removed or unintentionally dislodged. At the time, the murder was compared to those in Whitechapel, though the Metropolitan Police eventually ruled out any connection.Vanderlinden, Wolf (2003–04). "The New York Affair", in ''Ripper Notes'' part one No. 16 (July 2003); part two No. 17 (January 2004), part three No. 19 (July 2004 )

Investigation

The vast majority of the City of London Police files relating to their investigation into the Whitechapel murders were destroyed in

The vast majority of the City of London Police files relating to their investigation into the Whitechapel murders were destroyed in the Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

. The surviving Metropolitan Police files allow a detailed view of investigative procedures in the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

. A large team of policemen conducted house-to-house inquiries throughout Whitechapel. Forensic material was collected and examined. Suspects were identified, traced, and either examined more closely or eliminated from the inquiry. Modern police work follows the same pattern. More than 2,000 people were interviewed, "upwards of 300" people were investigated, and 80 people were detained. Following the murders of Stride and Eddowes, the Commissioner of the City Police, Sir James Fraser, offered a reward of £500 for the arrest of the Ripper.

The investigation was initially conducted by the Metropolitan Police Whitechapel (H) Division Criminal Investigation Department

The Criminal Investigation Department (CID) is the branch of a police force to which most plainclothes detectives belong in the United Kingdom and many Commonwealth nations. A force's CID is distinct from its Special Branch (though officers of b ...

(CID) headed by Detective Inspector Edmund Reid. After the murder of Nichols, Detective Inspectors Frederick Abberline

Frederick George Abberline (8 January 1843 – 10 December 1929) was a British chief inspector for the London Metropolitan Police. He is best known for being a prominent police figure in the investigation into the Jack the Ripper serial killer ...

, Henry Moore, and Walter Andrews were sent from Central Office at Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

to assist. The City of London Police were involved under Detective Inspector James McWilliam after the Eddowes murder, which occurred within the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

. The overall direction of the murder enquiries was hampered by the fact that the newly appointed head of the CID Robert Anderson was on leave in Switzerland between and , during the time when Chapman, Stride, and Eddowes were killed. This prompted Metropolitan Police Commissioner

The Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis is the head of London's Metropolitan Police Service. Sir Mark Rowley was appointed to the post on 8 July 2022 after Dame Cressida Dick announced her resignation in February.

The rank of Commission ...

Sir Charles Warren

General Sir Charles Warren, (7 February 1840 – 21 January 1927) was an officer in the British Royal Engineers. He was one of the earliest European archaeologists of the Biblical Holy Land, and particularly of the Temple Mount. Much of his mi ...

to appoint Chief Inspector Donald Swanson to coordinate the enquiry from Scotland Yard.

Butchers, slaughterers, surgeons, and physicians were suspected because of the manner of the mutilations. A surviving note from Major Henry Smith, Acting Commissioner of the City Police, indicates that the alibis of local butchers and slaughterers were investigated, with the result that they were eliminated from the inquiry. A report from Inspector Swanson to the Home Office confirms that 76 butchers and slaughterers were visited, and that the inquiry encompassed all their employees for the previous six months. Some contemporaneous figures, including Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

, thought the pattern of the murders indicated that the culprit was a butcher or cattle drover on one of the cattle boats that plied between London and mainland Europe. Whitechapel was close to the London Docks

London Docklands is the riverfront and former docks in London. It is located in inner east and southeast London, in the boroughs of Southwark, Tower Hamlets, Lewisham, Newham, and Greenwich. The docks were formerly part of the Port ...

, and usually such boats docked on Thursday or Friday and departed on Saturday or Sunday. The cattle boats were examined but the dates of the murders did not coincide with a single boat's movements and the transfer of a crewman between boats was also ruled out.

Whitechapel Vigilance Committee

In September 1888, a group of volunteer citizens in London's East End formed theWhitechapel Vigilance Committee

The Whitechapel Vigilance Committee was a group of local civilian volunteers who patrolled the streets of London's Whitechapel district during the period of the Whitechapel murders of 1888. The volunteers were active mainly at night, assisting th ...

. They patrolled the streets looking for suspicious characters, partly because of dissatisfaction with the failure of police to apprehend the perpetrator, and also because some members were concerned that the murders were affecting businesses in the area. The Committee petitioned the government to raise a reward for information leading to the arrest of the killer, offered their own reward of £50 (then a substantial sum) for information leading to his capture, and hired private detectives to question witnesses independently.

Criminal profiling

At the end of October, Robert Anderson asked police surgeon Thomas Bond to give his opinion on the extent of the murderer's surgical skill and knowledge. The opinion offered by Bond on the character of the "Whitechapel murderer" is the earliest surviving offender profile.Canter, pp. 5–6 Bond's assessment was based on his own examination of the most extensively mutilated victim and the post mortem notes from the four previous canonical murders.Letter from Thomas Bond to Robert Anderson, 1888, HO 144/221/A49301C, quoted in Evans and Skinner, ''The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook'', pp. 360–362 and Rumbelow, pp. 145–147 He wrote: Bond was strongly opposed to the idea that the murderer possessed any kind of scientific or anatomical knowledge, or even "the technical knowledge of a butcher or horse slaughterer". In his opinion, the killer must have been a man of solitary habits, subject to "periodical attacks of homicidal and erotic mania", with the character of the mutilations possibly indicating "satyriasis

Hypersexuality is extremely frequent or suddenly increased libido. It is controversial whether it should be included as a clinical diagnosis used by mental healthcare professionals. Nymphomania and satyriasis were terms previously used for the c ...

". Bond also stated that "the homicidal impulse may have developed from a revengeful or brooding condition of the mind, or that religious mania may have been the original disease but I do not think either hypothesis is likely".

There is no evidence the perpetrator engaged in sexual activity with any of the victims, yet psychologists suppose that the penetration of the victims with a knife and "leaving them on display in sexually degrading positions with the wounds exposed" indicates that the perpetrator derived sexual pleasure from the attacks. This view is challenged by others, who dismiss such hypotheses as insupportable supposition.

In addition to the contradictions and unreliability of contemporaneous accounts, attempts to identify the murderer are hampered by the lack of any surviving forensic evidence

Forensic identification is the application of forensic science, or "forensics", and technology to identify specific objects from the trace evidence they leave, often at a crime scene or the scene of an accident. Forensic means "for the courts".

H ...

. DNA analysis on extant letters is inconclusive; the available material has been handled many times and is too contaminated to provide meaningful results. There have been mutually incompatible claims that DNA evidence points conclusively to two

2 (two) is a number, numeral and digit. It is the natural number following 1 and preceding 3. It is the smallest and only even prime number. Because it forms the basis of a duality, it has religious and spiritual significance in many cultur ...

different suspects, and the methodology

In its most common sense, methodology is the study of research methods. However, the term can also refer to the methods themselves or to the philosophical discussion of associated background assumptions. A method is a structured procedure for br ...

of both has also been criticised.

Suspects

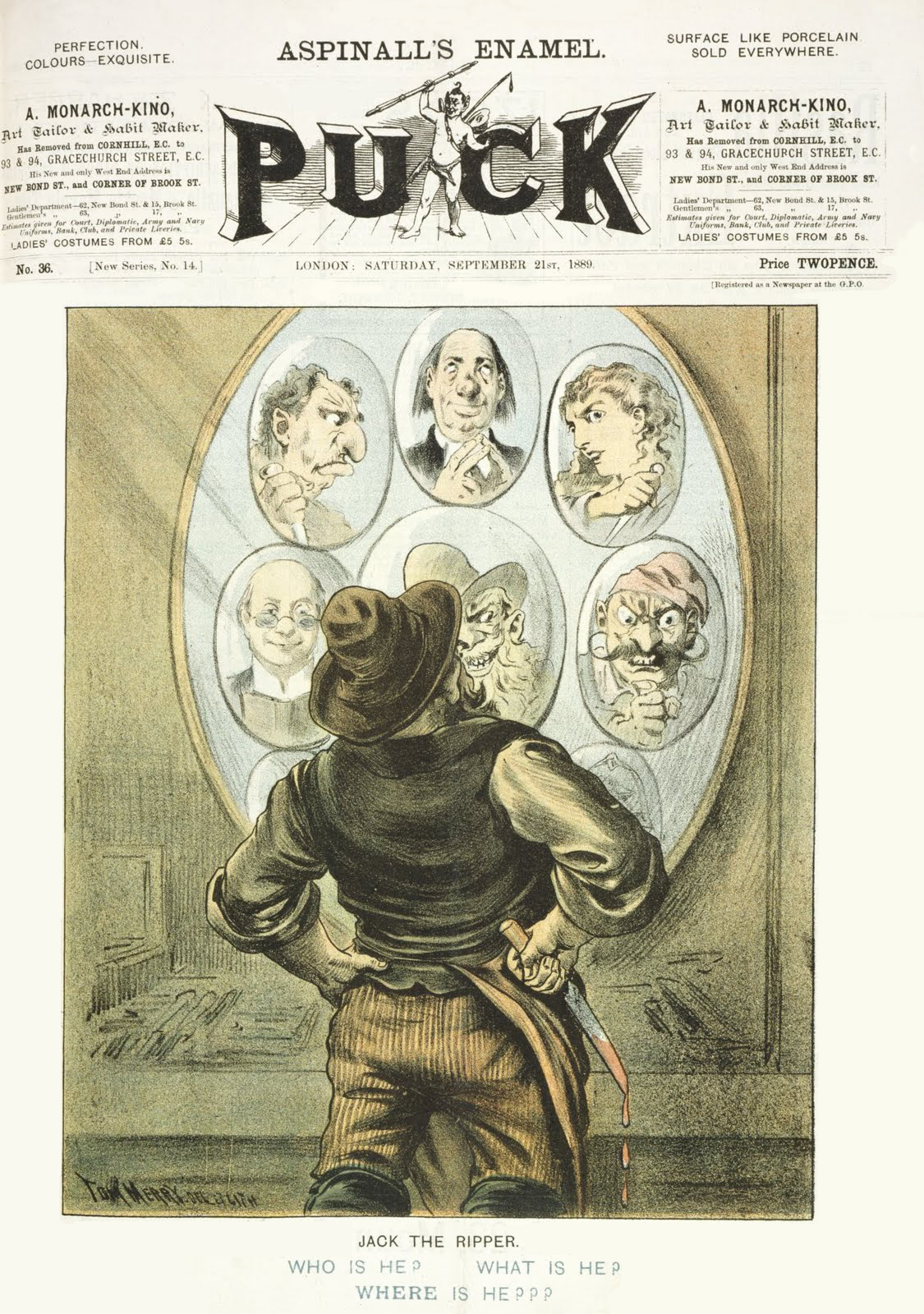

The concentration of the killings around weekends and public holidays and within a short distance of each other has indicated to many that the Ripper was in regular employment and lived locally. Others have opined that the killer was an educated upper-class man, possibly a doctor or an aristocrat who ventured into Whitechapel from a more well-to-do area. Such theories draw on cultural perceptions such as fear of the medical profession, a mistrust of modern science, or the exploitation of the poor by the rich. The term "Ripperology" was coined to describe the study and analysis of the Ripper case in an effort to determine his identity, and the murders have inspired numerous works of fiction.

Suspects proposed years after the murders include virtually anyone remotely connected to the case by contemporaneous documents, as well as many famous names who were never considered in the police investigation, including Prince Albert Victor, artist

The concentration of the killings around weekends and public holidays and within a short distance of each other has indicated to many that the Ripper was in regular employment and lived locally. Others have opined that the killer was an educated upper-class man, possibly a doctor or an aristocrat who ventured into Whitechapel from a more well-to-do area. Such theories draw on cultural perceptions such as fear of the medical profession, a mistrust of modern science, or the exploitation of the poor by the rich. The term "Ripperology" was coined to describe the study and analysis of the Ripper case in an effort to determine his identity, and the murders have inspired numerous works of fiction.

Suspects proposed years after the murders include virtually anyone remotely connected to the case by contemporaneous documents, as well as many famous names who were never considered in the police investigation, including Prince Albert Victor, artist Walter Sickert

Walter Richard Sickert (31 May 1860 – 22 January 1942) was a German-born British painter and printmaker who was a member of the Camden Town Group of Post-Impressionist artists in early 20th-century London. He was an important influence on d ...

, and author Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet and mathematician. His most notable works are '' Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (1865) and its sequ ...

. Everyone alive at the time is now long dead, and modern authors are free to accuse anyone "without any need for any supporting historical evidence". Suspects named in contemporaneous police documents include three in Sir Melville Macnaghten

Sir Melville Leslie Macnaghten (16 June 1853, Woodford, London −12 May 1921) was Assistant Commissioner (Crime) of the London Metropolitan Police from 1903 to 1913. A highly regarded and famously affable figure of the late Victorian and Edw ...

's 1894 memorandum, but the evidence against each of these individuals is, at best, circumstantial.

There are many, varied theories about the actual identity and profession of Jack the Ripper, but authorities are not agreed upon any of them, and the number of named suspects reaches over one hundred.Whiteway, Ken (2004). "A Guide to the Literature of Jack the Ripper", ''Canadian Law Library Review'', vol. 29 pp. 219–229 Despite continued interest in the case, the Ripper's identity remains unknown.

Letters

Over the course of the Whitechapel murders, the police, newspapers, and other individuals received hundreds of letters regarding the case. Some letters were well-intentioned offers of advice as to how to catch the killer, but the vast majority were either hoaxes or generally useless. Hundreds of letters claimed to have been written by the killer himself, and three of these in particular are prominent: the "Dear Boss" letter, the"Saucy Jacky" postcard

The "Saucy Jacky" postcard is the name given to a postcard received by the Central News Agency of London and postmarked 1 October 1888. The author of the postcard claims to have been the unidentified serial killer known as Jack the Ripper.

Beca ...

and the "From Hell" letter.

The "Dear Boss" letter, dated and postmark

A postmark is a postal marking made on an envelope, parcel, postcard or the like, indicating the place, date and time that the item was delivered into the care of a postal service, or sometimes indicating where and when received or in transit ...

ed 1888, was received that day by the Central News Agency, and was forwarded to Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

on . Initially, it was considered a hoax, but when Eddowes was found three days after the letter's postmark with a section of one ear obliquely cut from her body, the promise of the author to "clip the ladys (sic

The Latin adverb ''sic'' (; "thus", "just as"; in full: , "thus was it written") inserted after a quoted word or passage indicates that the quoted matter has been transcribed or translated exactly as found in the source text, complete with any e ...

) ears off" gained attention. Eddowes's ear appears to have been nicked by the killer incidentally during his attack, and the letter writer's threat to send the ears to the police was never carried out. The name "Jack the Ripper" was first used in this letter by the signatory and gained worldwide notoriety after its publication. Most of the letters that followed copied this letter's tone, with some authors adopting pseudonyms such as "George of the High Rip Gang" and "Jack Sheridan, the Ripper." Some sources claim that another letter dated 1888 was the first to use the name "Jack the Ripper", but most experts believe that this was a fake inserted into police records in the 20th century.

The "Saucy Jacky" postcard was postmarked 1888 and was received the same day by the Central News Agency. The handwriting was similar to the "Dear Boss" letter, and mentioned the canonical murders committed on 30 September, which the author refers to by writing "double event this time". It has been argued that the postcard was posted before the murders were publicised, making it unlikely that a crank would hold such knowledge of the crime. However, it was postmarked more than 24 hours after the killings occurred, long after details of the murders were known and publicised by journalists, and had become general community gossip by the residents of Whitechapel.Cook, pp. 79–80; Fido, pp. 8–9; Marriott, Trevor, pp. 219–222; Rumbelow, p. 123

The "From Hell" letter was received by

The "Saucy Jacky" postcard was postmarked 1888 and was received the same day by the Central News Agency. The handwriting was similar to the "Dear Boss" letter, and mentioned the canonical murders committed on 30 September, which the author refers to by writing "double event this time". It has been argued that the postcard was posted before the murders were publicised, making it unlikely that a crank would hold such knowledge of the crime. However, it was postmarked more than 24 hours after the killings occurred, long after details of the murders were known and publicised by journalists, and had become general community gossip by the residents of Whitechapel.Cook, pp. 79–80; Fido, pp. 8–9; Marriott, Trevor, pp. 219–222; Rumbelow, p. 123

The "From Hell" letter was received by George Lusk

George Akin Lusk (1839–1919) was a British builder and decorator who specialised in music hall restoration, and was the chairman of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee during the Whitechapel murders, including the killings ascribed to Jack t ...

, leader of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, on 1888. The handwriting and style is unlike that of the "Dear Boss" letter and "Saucy Jacky" postcard. The letter came with a small box in which Lusk discovered half of a human kidney, preserved in "spirits of wine" (ethanol