A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to the Islamic prophet

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

and a leader of the entire

Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

(

ummah

' (; ar, أمة ) is an Arabic word meaning "community". It is distinguished from ' ( ), which means a nation with common ancestry or geography. Thus, it can be said to be a supra-national community with a common history.

It is a synonym for ' ...

).

Historically, the caliphates were

polities based on Islam which developed into multi-ethnic trans-national empires. During the medieval period, three major caliphates succeeded each other: the

Rashidun Caliphate

The Rashidun Caliphate ( ar, اَلْخِلَافَةُ ٱلرَّاشِدَةُ, al-Khilāfah ar-Rāšidah) was the first caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was ruled by the first four successive caliphs of Muhammad after his ...

(632–661), the

Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

(661–750), and the

Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttal ...

(750–1258). In the fourth major caliphate, the

Ottoman Caliphate

The Caliphate of the Ottoman Empire ( ota, خلافت مقامى, hilâfet makamı, office of the caliphate) was the claim of the heads of the Turkish Ottoman dynasty to be the caliphs of Islam in the late medieval and the early modern era. ...

, the rulers of the Ottoman Empire claimed caliphal authority from 1517. Throughout the history of Islam, a few other Muslim states, almost all

hereditary monarchies such as the

Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo)

The Mamluk Sultanate ( ar, سلطنة المماليك, translit=Salṭanat al-Mamālīk), also known as Mamluk Egypt or the Mamluk Empire, was a state that ruled Egypt, the Levant and the Hejaz (western Arabia) from the mid-13th to early 1 ...

and

Ayyubid Caliphate, have claimed to be caliphates.

The first caliphate, the Rashidun Caliphate, was established in 632 immediately after Muhammad's death. It was followed by the Umayyad Caliphate and the Abbasid Caliphate. The last caliphate, the Ottoman Caliphate, existed until it was abolished in 1924 by the

Turkish Republic

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

. Not all Muslim states have had caliphates, and only a minority of Muslims recognize any particular caliph as legitimate in the first place. The

Sunni

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a dis ...

branch of Islam stipulates that, as a head of state, a caliph should be elected by Muslims or their representatives. Followers of

Shia Islam

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, mos ...

, however, believe a caliph should be an Imam chosen by God from the

Ahl al-Bayt

Ahl al-Bayt ( ar, أَهْل ٱلْبَيْت, ) refers to the family of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, but the term has also been extended in Sunni Islam to apply to all descendants of the Banu Hashim (Muhammad's clan) and even to all Muslims. I ...

(the "Household of the Prophet").

In the early 21st century, following the failure of the

Arab Spring

The Arab Spring ( ar, الربيع العربي) was a series of anti-government protests, uprisings and armed rebellions that spread across much of the Arab world in the early 2010s. It began in Tunisia in response to corruption and econo ...

and related protests, some have argued for a return to the concept of a caliphate to better unify Muslims. The caliphate system was abolished in Turkey in 1924 during the secularization of Turkey as part of

Atatürk's Reforms.

Etymology

Before the advent of Islam, Arabian

monarch

A monarch is a head of stateWebster's II New College DictionarMonarch Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest authority ...

s traditionally used the title ''

malik

Malik, Mallik, Melik, Malka, Malek, Maleek, Malick, Mallick, or Melekh ( phn, 𐤌𐤋𐤊; ar, ملك; he, מֶלֶךְ) is the Semitic term translating to "king", recorded in East Semitic and Arabic, and as mlk in Northwest Semitic d ...

''(King, ruler), or another from the same

root

In vascular plants, the roots are the organs of a plant that are modified to provide anchorage for the plant and take in water and nutrients into the plant body, which allows plants to grow taller and faster. They are most often below the su ...

.

The term ''caliph'' (), derives from the

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

word ' (, ), which means "successor", "steward", or "deputy" and has traditionally been considered a shortening of ''Khalīfat Rasūl Allāh'' ("successor of the messenger of God"). However, studies of pre-Islamic texts suggest that the original meaning of the phrase was "successor ''selected by'' God".

History

Rashidun Caliphate (632–661)

Succession to Muhammad

In the immediate aftermath of the death of Muhammad, a gathering of the

Ansar (natives of

Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

) took place in the ''Saqifah'' (courtyard) of the

Banu Sa'ida

The Banu Sa'ida ( ar-at, بنو ساعدة, Banu Sā'idah) was a clan of the Banu Khazraj tribe of Medina in the era of Muhammad. The tribe's full name was the Banu Sa'ida ibn Ka'b ibn al-Khazraj.

Prior to their conversion, most members of the cla ...

clan. The general belief at the time was that the purpose of the meeting was for the Ansar to decide on a new leader of the

Muslim community among themselves, with the intentional exclusion of the

Muhajirun

The ''Muhajirun'' ( ar, المهاجرون, al-muhājirūn, singular , ) were the first converts to Islam and the Islamic prophet Muhammad's advisors and relatives, who emigrated with him from Mecca to Medina, the event known in Islam as the '' Hij ...

(migrants from

Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow v ...

), though this has later become the subject of debate.

Nevertheless,

Abu Bakr

Abu Bakr Abdallah ibn Uthman Abi Quhafa (; – 23 August 634) was the senior companion and was, through his daughter Aisha, a father-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, as well as the first caliph of Islam. He is known with the honor ...

and

Umar

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb ( ar, عمر بن الخطاب, also spelled Omar, ) was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () as the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate ...

, both prominent companions of Muhammad, upon learning of the meeting became concerned of a potential coup and hastened to the gathering. Upon arriving, Abu Bakr addressed the assembled men with a warning that an attempt to elect a leader outside of Muhammad's own tribe, the

Quraysh

The Quraysh ( ar, قُرَيْشٌ) were a grouping of Arab clans that historically inhabited and controlled the city of Mecca and its Kaaba. The Islamic prophet Muhammad was born into the Hashim clan of the tribe. Despite this, many of the Qu ...

, would likely result in dissension as only they can command the necessary respect among the community. He then took Umar and another companion,

Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah

ʿĀmir ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Jarrāḥ ( ar, عامر بن عبدالله بن الجراح; 583–639 CE), better known as Abū ʿUbayda ( ar, أبو عبيدة ) was a Muslim commander and one of the Companions of the Islamic prophet ...

, by the hand and offered them to the Ansar as potential choices. He was countered with the suggestion that the Quraysh and the Ansar choose a leader each from among themselves, who would then rule jointly. The group grew heated upon hearing this proposal and began to argue amongst themselves. Umar hastily took Abu Bakr's hand and swore his own allegiance to the latter, an example followed by the gathered men.

Abu Bakr was near-universally accepted as head of the Muslim community (under the title of Caliph) as a result of Saqifah, though he did face contention as a result of the rushed nature of the event. Several companions, most prominent among them being

Ali ibn Abi Talib

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam. ...

, initially refused to acknowledge his authority. Ali may have been reasonably expected to assume leadership, being both cousin and son-in-law to Muhammad. The theologian

Ibrahim al-Nakha'i

( ar, أبو عمران إبراهيم بن يزيد النخعي), also known as , c. 670 CE/50 AH - 714 CE/96 AH), was an Islamic theologian and jurist (). Though belonging to the generation following the companions of Muhammad (the ), he ...

stated that Ali also had support among the Ansar for his succession, explained by the genealogical links he shared with them. Whether his candidacy for the succession was raised during Saqifah is unknown, though it is not unlikely. Abu Bakr later sent Umar to confront Ali to gain his allegiance, resulting in

an altercation which may have involved violence. However, after six months the group made peace with Abu Bakr and Ali offered him his fealty.

Rāshidun Caliphs

Abu Bakr nominated Umar as his successor on his deathbed. Umar, the second caliph, was killed by a Persian slave called

Abu Lu'lu'a Firuz

Abū Luʾluʾa Fīrūz ( ar, أبو لؤلؤة فيروز; from ), also known as Bābā Shujāʿ al-Dīn ( ar, بابا شجاع الدين, label=none), was a Sassanid Persian slave known for having assassinated Umar ibn al-Khattab (), the s ...

. His successor, Uthman, was elected by a council of electors (

majlis

( ar, المجلس, pl. ') is an Arabic term meaning "sitting room", used to describe various types of special gatherings among common interest groups of administrative, social or religious nature in countries with linguistic or cultural conne ...

). Uthman was killed by members of a disaffected group.

Ali then took control but was not universally accepted as caliph by the governors of Egypt and later by some of his own guard. He faced two major rebellions and was assassinated by

Abd-al-Rahman ibn Muljam, a

Khawarij

The Kharijites (, singular ), also called al-Shurat (), were an Islamic sect which emerged during the First Fitna (656–661). The first Kharijites were supporters of Ali who rebelled against his acceptance of arbitration talks to settle the ...

. Ali's tumultuous rule lasted only five years. This period is known as the

Fitna, or the first Islamic civil war. The followers of Ali later became the Shi'a ("shiaat Ali", partisans of Ali.

) minority sect of Islam and reject the legitimacy of the first 3 caliphs. The followers of all four Rāshidun Caliphs (Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Ali) became the majority Sunni sect.

Under the Rāshidun each region (

Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it c ...

ate,

Wilayah

A wilayah ( ar, وَلاية, wālāya or ''wilāya'', plural ; Urdu and fa, ولایت, ''velâyat''; tr, vilayet) is an administrative division, usually translated as "state", "province" or occasionally as " governorate". The word comes f ...

, or

Emirate) of the Caliphate had its own governor (Sultan,

Wāli

''Wāli'', ''Wā'lī'' or ''vali'' (from ar, والي ''Wālī'') is an administrative title that was used in the Muslim World (including the Caliphate and Ottoman Empire) to designate governors of administrative divisions. It is still in us ...

or

Emir

Emir (; ar, أمير ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cer ...

).

Muāwiyah, a relative of Uthman and governor (''Wali'') of

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, succeeded Ali as Caliph. Muāwiyah transformed the caliphate into a

hereditary

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic informa ...

office, thus founding the Umayyad

dynasty

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family,''Oxford English Dictionary'', "dynasty, ''n''." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1897. usually in the context of a monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A ...

.

In areas which were previously under

Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

or

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

rule, the Caliphs lowered taxes, provided greater local autonomy (to their delegated governors), greater religious freedom for

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, and some indigenous

Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ� ...

, and brought peace to peoples demoralised and disaffected by the casualties and heavy taxation that resulted from the decades of

Byzantine-Persian warfare.

Ali's caliphate, Hasan and the rise of the Umayyad dynasty

Ali's reign was plagued by turmoil and internal strife. The Persians, taking advantage of this, infiltrated the two armies and attacked the other army causing chaos and internal hatred between the

companions at the

Battle of Siffin. The battle lasted several months, resulting in a stalemate. In order to avoid further bloodshed, Ali agreed to negotiate with Mu'awiyah. This caused a faction of approximately 4,000 people, who would come to be known as the

Kharijites

The Kharijites (, singular ), also called al-Shurat (), were an Islamic sect which emerged during the First Fitna (656–661). The first Kharijites were supporters of Ali who rebelled against his acceptance of arbitration talks to settle the ...

, to abandon the fight. After defeating the Kharijites at the

Battle of Nahrawan, Ali was later assassinated by the Kharijite Ibn Muljam. Ali's son

Hasan was elected as the next caliph, but abdicated in favor of Mu'awiyah a few months later to avoid any conflict within the Muslims. Mu'awiyah became the sixth caliph, establishing the Umayyad Dynasty, named after the great-grandfather of Uthman and Mu'awiyah,

Umayya ibn Abd Shams.

Umayyad Caliphate (661–750)

Beginning with the Umayyads, the title of the caliph became hereditary. Under the Umayyads, the Caliphate grew rapidly in territory, incorporating the

Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

,

Transoxiana

Transoxiana or Transoxania (Land beyond the Oxus) is the Latin name for a region and civilization located in lower Central Asia roughly corresponding to modern-day eastern Uzbekistan, western Tajikistan, parts of southern Kazakhstan, parts of Tu ...

,

Sindh

Sindh (; ; ur, , ; historically romanized as Sind) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest province ...

, the

Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

and most of the

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

(

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

) into the Muslim world. At its greatest extent, the Umayyad Caliphate covered 5.17 million square miles (13,400,000 km

2), making it the

largest empire the world had yet seen and the

sixth-largest ever to exist in history.

Geographically, the empire was divided into several provinces, the borders of which changed numerous times during the Umayyad reign. Each province had a governor appointed by the caliph. However, for a variety of reasons, including that they were not elected by

Shura

Shura ( ar, شُورَىٰ, translit=shūrā, lit=consultation) can for example take the form of a council or a referendum. The Quran encourages Muslims to decide their affairs in consultation with each other.

Shura is mentioned as a praisewor ...

and suggestions of impious behaviour, the Umayyad dynasty was not universally supported within the Muslim community. Some supported prominent early Muslims like

Zubayr ibn al-Awwam

Az Zubayr ( ar, الزبير) is a city in and the capital of Al-Zubair District, part of the Basra Governorate of Iraq. The city is just south of Basra. The name can also refer to the old Emirate of Zubair.

The name is also sometimes written ...

; others felt that only members of Muhammad's clan, the

Banu Hashim

)

, type = Qurayshi Arab clan

, image =

, alt =

, caption =

, nisba = al-Hashimi

, location = Mecca, Hejaz Middle East, North Africa, Horn of Africa

, descended = Hashim ibn Abd Manaf

, parent_tribe = ...

, or his own lineage, the descendants of Ali, should rule.

There were numerous rebellions against the Umayyads, as well as splits within the Umayyad ranks (notably, the rivalry between

Yaman and Qays). At the command of Yazid son of Muawiya, an army led by Umar ibn Saad, a commander by the name of Shimr Ibn Thil-Jawshan killed Ali's son

Hussein and his family at the

Battle of Karbala

The Battle of Karbala ( ar, مَعْرَكَة كَرْبَلَاء) was fought on 10 October 680 (10 Muharram in the year 61 AH of the Islamic calendar) between the army of the second Umayyad Caliph Yazid I and a small army led by Husayn ...

in 680, solidifying the

Shia-Sunni split.

[ Eventually, supporters of the Banu Hashim and the supporters of the lineage of Ali united to bring down the Umayyads in 750. However, the ''Shi‘at ‘Alī'', "the Party of Ali", were again disappointed when the ]Abbasid dynasty

The Abbasid dynasty or Abbasids ( ar, بنو العباس, Banu al-ʿAbbās) were an Arab dynasty that ruled the Abbasid Caliphate between 750 and 1258. They were from the Qurayshi Hashimid clan of Banu Abbas, descended from Abbas ibn Abd al- ...

took power, as the Abbasids were descended from Muhammad's uncle, ‘Abbas ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib

Al-Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib ( ar, ٱلْعَبَّاسُبْنُ عَبْدِ ٱلْمُطَّلِبِ, al-ʿAbbās ibn ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib; CE) was a paternal uncle and Sahabi (companion) of Muhammad, just three years older than his ...

and not from Ali.

Abbasid Caliphate (750–1517)

Abbasid Caliphs at Baghdad

In 750, the Umayyad dynasty was overthrown by another family of

In 750, the Umayyad dynasty was overthrown by another family of Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow v ...

n origin, the Abbasids. Their time represented a scientific, cultural and religious flowering. Islamic art and music also flourished significantly during their reign. Their major city and capital Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

began to flourish as a center of knowledge, culture and trade. This period of cultural fruition ended in 1258 with the sack of Baghdad by the Mongols under Hulagu Khan

Hulagu Khan, also known as Hülegü or Hulegu ( mn, Хүлэгү/ , lit=Surplus, translit=Hu’legu’/Qülegü; chg, ; Arabic: fa, هولاکو خان, ''Holâku Khân;'' ; 8 February 1265), was a Mongol ruler who conquered much of We ...

. The Abbasid Caliphate had however lost its effective power outside Iraq already by c. 920. By 945, the loss of power became official when the Buyids

The Buyid dynasty ( fa, آل بویه, Āl-e Būya), also spelled Buwayhid ( ar, البويهية, Al-Buwayhiyyah), was a Shia Iranian dynasty of Daylamite origin, which mainly ruled over Iraq and central and southern Iran from 934 to 1062. Coup ...

conquered Baghdad and all of Iraq. The empire fell apart and its parts were ruled for the next century by local dynasties.

In the 9th century, the Abbasids

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

created an army loyal only to their caliphate, composed predominantly of Turkic Cuman, Circassian and Georgian slave origin known as Mamluks. By 1250 the Mamluks came to power in Egypt. The Mamluk army, though often viewed negatively, both helped and hurt the caliphate. Early on, it provided the government with a stable force to address domestic and foreign problems. However, creation of this foreign army and al-Mu'tasim's transfer of the capital from Baghdad to Samarra created a division between the caliphate and the peoples they claimed to rule. In addition, the power of the Mamluks steadily grew until Ar-Radi (934–41) was constrained to hand over most of the royal functions to Muhammad ibn Ra'iq

Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Ra'iq (died 13 February 942), usually simply known as Ibn Ra'iq, was a senior official of the Abbasid Caliphate, who exploited the caliphal government's weakness to become the first '' amir al-umara'' ("commander of commander ...

.

Under the Mamluk Sultanate of Cairo (1261–1517)

In 1261, following the Mongol conquest of Baghdad

The siege of Baghdad was a siege that took place in Baghdad in 1258, lasting for 13 days from January 29, 1258 until February 10, 1258. The siege, laid by Ilkhanate Mongol forces and allied troops, involved the investment, capture, and sack ...

, the Mamluk rulers of Egypt tried to gain legitimacy for their rule by declaring the re-establishment of the Abbasid caliphate in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

. The Abbasid caliphs in Egypt had little political power; they continued to maintain the symbols of authority, but their sway was confined to religious matters. The first Abbasid caliph of Cairo was Al-Mustansir (r. June–November 1261). The Abbasid caliphate of Cairo lasted until the time of Al-Mutawakkil III, who ruled as caliph from 1508 to 1516, then he was deposed briefly in 1516 by his predecessor Al-Mustamsik, but was restored again to the caliphate in 1517.

The Ottoman Great Sultan Selim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite las ...

defeated the Mamluk Sultanate and made Egypt part of the Ottoman Empire in 1517. Al-Mutawakkil III was captured together with his family and transported to Constantinople as a prisoner where he had a ceremonial role. He died in 1543, following his return to Cairo.

Parallel regional caliphates in the later Abbasid Era

The Abbasid dynasty lost effective power over much of the Muslim realm by the first half of the tenth century.

The Umayyad dynasty, which had survived and come to rule over Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

, reclaimed the title of Caliph in 929, lasting until it was overthrown in 1031.

= Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba (929–1031)

=

During the Umayyad dynasty, the

During the Umayyad dynasty, the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

was an integral province of the Umayyad Caliphate ruling from Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

. The Umayyads lost the position of Caliph in Damascus in 750, and Abd al-Rahman I became Emir of Córdoba in 756 after six years in exile. Intent on regaining power, he defeated the existing Islamic rulers of the area who defied Umayyad rule and united various local fiefdoms into an emirate.

Rulers of the emirate used the title "emir" or "sultan" until the 10th century, when Abd al-Rahman III was faced with the threat of invasion by the Fatimid Caliphate. To aid his fight against the invading Fatimids, who claimed the caliphate in opposition to the generally recognised Abbasid Caliph of Baghdad, Al-Mu'tadid

Abū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad ibn Ṭalḥa al-Muwaffaq ( ar, أبو العباس أحمد بن طلحة الموفق), 853/4 or 860/1 – 5 April 902, better known by his regnal name al-Muʿtaḍid bi-llāh ( ar, المعتضد بالله, link=no, ...

, Abd al-Rahman III claimed the title of caliph himself. This helped Abd al-Rahman III gain prestige with his subjects, and the title was retained after the Fatimids were repulsed. The rule of the Caliphate is considered as the heyday of Muslim presence in the Iberian peninsula, before it fragmented into various taifa

The ''taifas'' (singular ''taifa'', from ar, طائفة ''ṭā'ifa'', plural طوائف ''ṭawā'if'', a party, band or faction) were the independent Muslim principalities and kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula (modern Portugal and Spain), re ...

s in the 11th century. This period was characterised by a flourishing in technology, trade and culture; many of the buildings of al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

were constructed in this period.

= Almohad Caliphate (1147–1269)

=

The Almohad Caliphate ( ber, Imweḥḥden, from

The Almohad Caliphate ( ber, Imweḥḥden, from Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

', " the Monotheists" or "the Unifiers") was a Moroccan Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–19 ...

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

movement founded in the 12th century.Ibn Tumart

Abu Abd Allah Amghar Ibn Tumart ( Berber: ''Amghar ibn Tumert'', ar, أبو عبد الله امغار ابن تومرت, ca. 1080–1130 or 1128) was a Muslim Berber religious scholar, teacher and political leader, from the Sous in southern M ...

among the Masmuda

The Masmuda ( ar, المصمودة, Berber: ⵉⵎⵙⵎⵓⴷⵏ) is a Berber tribal confederation of Morocco and one of the largest in the Maghreb, along with the Zanata and the Sanhaja. They were composed of several sub-tribes: Berghoua ...

tribes of southern Morocco. The Almohads first established a Berber state in Tinmel

Tinmel ( Berber: Tin Mel or Tin Mal, ar, تينمل) is a small mountain village in the High Atlas 100 km from Marrakesh, Morocco. Tinmel was the cradle of the Berber Almohad empire, from where the Almohads started their military campaigns ...

in the Atlas Mountains

The Atlas Mountains are a mountain range in the Maghreb in North Africa. It separates the Sahara Desert from the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean; the name "Atlantic" is derived from the mountain range. It stretches around through ...

in roughly 1120.Almoravid dynasty

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century tha ...

in governing Morocco by 1147, when Abd al-Mu'min

Abd al Mu'min (c. 1094–1163) ( ar, عبد المؤمن بن علي or عبد المومن الــكـومي; full name: ʿAbd al-Muʾmin ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAlwī ibn Yaʿlā al-Kūmī Abū Muḥammad) was a prominent member of the Almohad mov ...

(r. 1130–1163) conquered Marrakech and declared himself Caliph. They then extended their power over all of the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

by 1159. Al-Andalus followed the fate of Africa and all Islamic Iberia was under Almohad rule by 1172.

The Almohad dominance of Iberia continued until 1212, when Muhammad al-Nasir (1199–1214) was defeated at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in the Sierra Morena

The Sierra Morena is one of the main systems of mountain ranges in Spain. It stretches for 450 kilometres from east to west across the south of the Iberian Peninsula, forming the southern border of the '' Meseta Central'' plateau and pro ...

by an alliance of the Christian princes of Castile, Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to s ...

, Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

. Nearly all of the Moorish

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or s ...

dominions in Iberia were lost soon after, with the great Moorish cities of Córdoba and Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Penins ...

falling to the Christians in 1236 and 1248, respectively.

The Almohads continued to rule in northern Africa until the piecemeal loss of territory through the revolt of tribes and districts enabled the rise of their most effective enemies, the Marinid dynasty

The Marinid Sultanate was a Berber Muslim empire from the mid-13th to the 15th century which controlled present-day Morocco and, intermittently, other parts of North Africa (Algeria and Tunisia) and of the southern Iberian Peninsula (Spain) a ...

, in 1215. The last representative of the line, Idris al-Wathiq, was reduced to the possession of Marrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech ( or ; ar, مراكش, murrākuš, ; ber, ⵎⵕⵕⴰⴽⵛ, translit=mṛṛakc}) is the fourth largest city in the Kingdom of Morocco. It is one of the four Imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakes ...

, where he was murdered by a slave in 1269; the Marinids seized Marrakesh, ending the Almohad domination of the Western Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

.

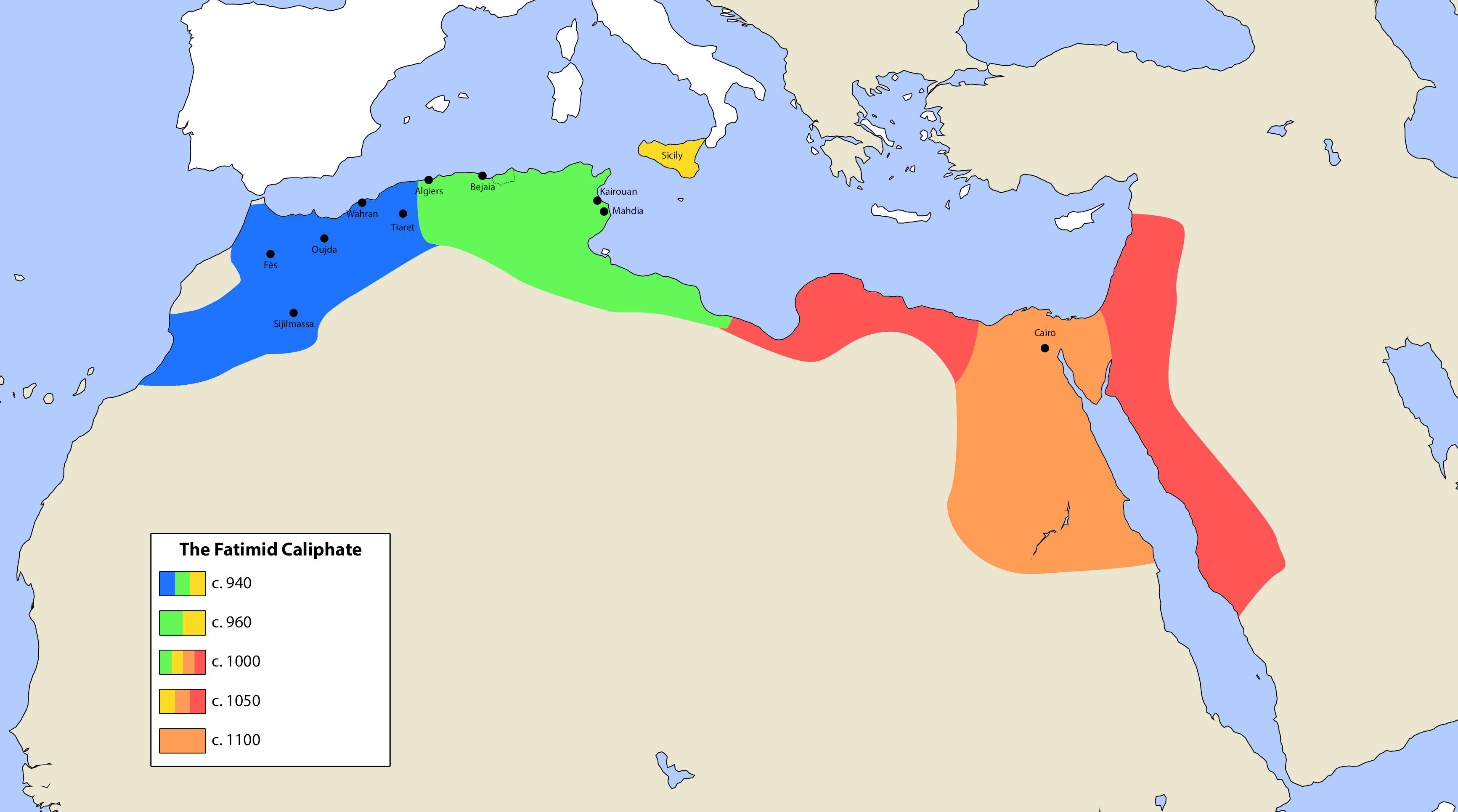

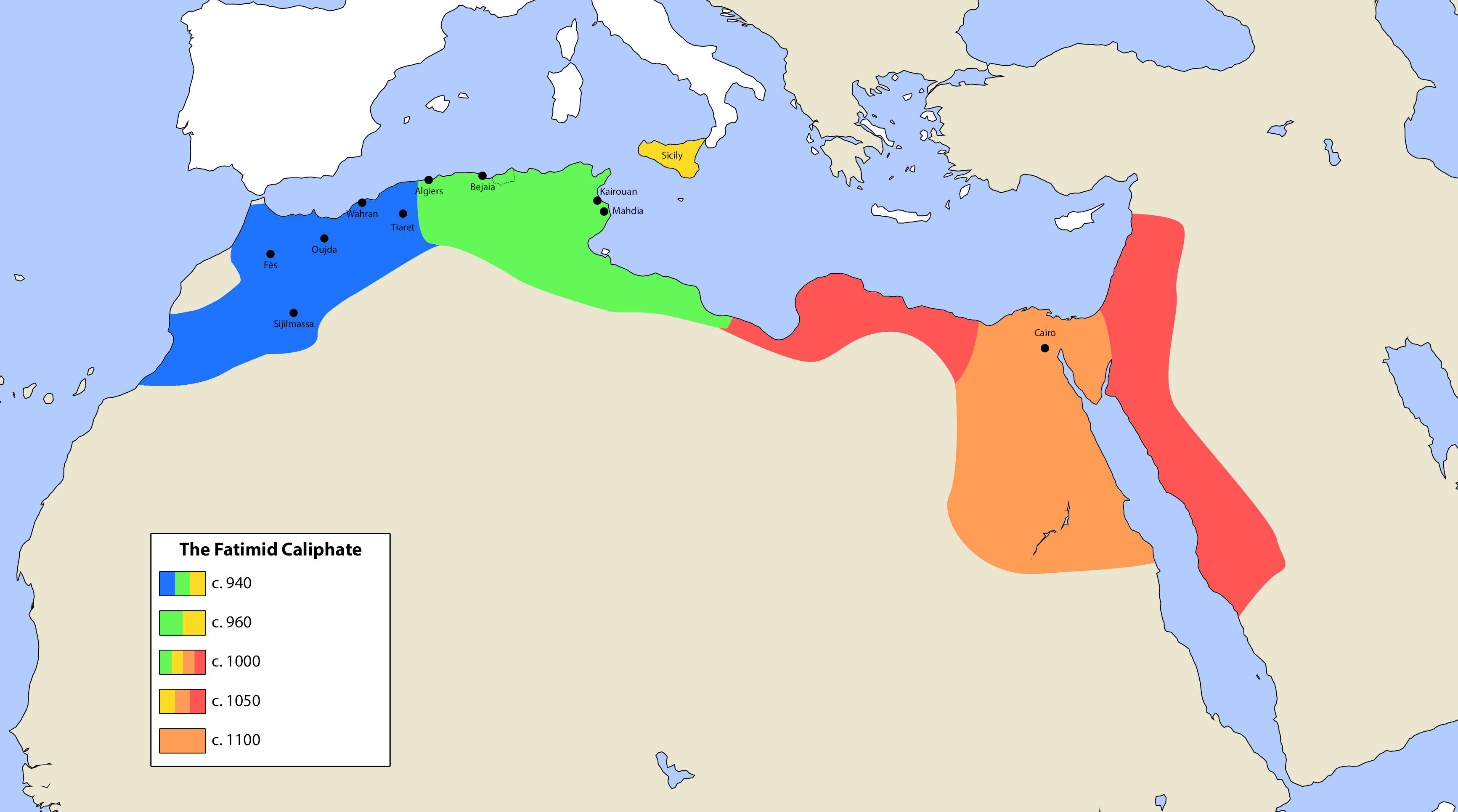

Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171)

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Isma'ili Shi'i caliphate, originally based in

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Isma'ili Shi'i caliphate, originally based in Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

, that extended its rule across the Mediterranean coast of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

and ultimately made Egypt the centre of its caliphate. At its height, in addition to Egypt, the caliphate included varying areas of the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

and the Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Prov ...

.

The Fatimids established the Tunisian city of Mahdia and made it their capital city, before conquering Egypt and building the city of Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

there in 969. Thereafter, Cairo became the capital of the caliphate, with Egypt becoming the political, cultural and religious centre of the state. Islam scholar Louis Massignon dubbed the 4th century AH /10th century CE as the "Ismaili

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor ( imām) to Ja'far al ...

century in the history of Islam".

The term ''Fatimite'' is sometimes used to refer to the citizens of this caliphate. The ruling elite of the state belonged to the Ismaili branch of Shi'ism. The leaders of the dynasty were Ismaili imams and had a religious significance to Ismaili Muslims. They are also part of the chain of holders of the office of the Caliphate, as recognised by some Muslims. Therefore, this constitutes a rare period in history in which the descendants of Ali (hence the name Fatimid, referring to Ali's wife Fatima

Fāṭima bint Muḥammad ( ar, فَاطِمَة ٱبْنَت مُحَمَّد}, 605/15–632 CE), commonly known as Fāṭima al-Zahrāʾ (), was the daughter of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and his wife Khadija. Fatima's husband was Ali, ...

) and the Caliphate were united to any degree, excepting the final period of the Rashidun Caliphate

The Rashidun Caliphate ( ar, اَلْخِلَافَةُ ٱلرَّاشِدَةُ, al-Khilāfah ar-Rāšidah) was the first caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was ruled by the first four successive caliphs of Muhammad after his ...

under Ali himself.

The caliphate was reputed to exercise a degree of religious tolerance towards non-Ismaili sects of Islam as well as towards Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, Maltese Christians and Copts

Copts ( cop, ⲛⲓⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ ; ar, الْقِبْط ) are a Christian ethnoreligious group indigenous to North Africa who have primarily inhabited the area of modern Egypt and Sudan since antiquity. Most ethnic Copts are ...

.

The Shiʻa Ubayd Allah al-Mahdi Billah

Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh/ʿUbayd Allāh ibn al-Ḥusayn (), 873 – 4 March 934, better known by his regnal name al-Mahdi Billah, was the founder of the Isma'ili Fatimid Caliphate, the only major Shi'a caliphate in Islamic history, and the ...

of the Fatimid dynasty

The Fatimid dynasty () was an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty of Arab descent that ruled an extensive empire, the Fatimid Caliphate, between 909 and 1171 CE. Claiming descent from Fatima and Ali, they also held the Isma'ili imamate, claiming to be the ...

, who claimed descent from Muhammad through his daughter, claimed the title of Caliph in 909, creating a separate line of caliphs in North Africa. Initially controlling Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

and Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

, the Fatimid caliphs extended their rule for the next 150 years, taking Egypt and Palestine, before the Abbasid dynasty was able to turn the tide, limiting Fatimid rule to Egypt. The Fatimid dynasty finally ended in 1171 and was overtaken by Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt an ...

of the Ayyubid dynasty

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish origin, Saladin ...

.

Ayyubid Caliphate (1171–1260)

The Ayyubid Empire overtook the

The Ayyubid Empire overtook the Fatimids

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Isma'ilism, Ismaili Shia Islam, Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the ea ...

by incorporating the empire into the .Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt an ...

himself has been a widely celebrated caliph in Islamic history

The history of Islam concerns the political, social, economic, military, and cultural developments of the Islamic civilization. Most historians believe that Islam originated in Mecca and Medina at the start of the 7th century CE. Muslims ...

.[Natho, Kadir I. ''Circassian History''. Pages 150]

Ottoman Caliphate (1517–1924)

The caliphate was claimed by the sultans of the Ottoman Empire beginning with

The caliphate was claimed by the sultans of the Ottoman Empire beginning with Murad I

Murad I ( ota, مراد اول; tr, I. Murad, Murad-ı Hüdavendigâr (nicknamed ''Hüdavendigâr'', from fa, خداوندگار, translit=Khodāvandgār, lit=the devotee of God – meaning "sovereign" in this context); 29 June 1326 – 15 Jun ...

(reigned 1362 to 1389),Edirne

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis ( Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders ...

. In 1453, after Mehmed the Conqueror

Mehmed II ( ota, محمد ثانى, translit=Meḥmed-i s̱ānī; tr, II. Mehmed, ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror ( ota, ابو الفتح, Ebū'l-fetḥ, lit=the Father of Conquest, links=no; tr, Fâtih Su ...

's conquest of Constantinople, the seat of the Ottomans moved to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, present-day Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

. In 1517, the Ottoman sultan Selim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite las ...

defeated and annexed the Mamluk Sultanate of Cairo into his empire.Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow v ...

and Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

, which further strengthened the Ottoman claim to the caliphate in the Muslim world. Ottomans gradually came to be viewed as the ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with '' de jure'' ("by l ...

'' leaders and representatives of the Islamic world. However, the earlier Ottoman caliphs did not officially bear the title of caliph in their documents of state, inscriptions, or coinage.[Dominique Sourdel]

"The history of the institution of the caliphate"

(1978) It was only in the late eighteenth century that the claim to the caliphate was discovered by the sultans to have a practical use, since it allowed them to counter Russian claims to protect Ottoman Christians with their own claim to protect Muslims under Russian rule.Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a p ...

, were lost to the Russian Empire.Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

in 1774, when the Empire retained moral authority Moral authority is authority premised on principles, or fundamental truths, which are independent of written, or positive, laws. As such, moral authority necessitates the existence of and adherence to truth. Because truth does not change, the princi ...

on territory whose sovereignty was ceded to the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

.British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

. By the eve of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

, the Ottoman state, despite its weakness relative to Europe, represented the largest and most powerful independent Islamic political entity. The sultan also enjoyed some authority beyond the borders of his shrinking empire as caliph of Muslims in Egypt, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

and Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the fo ...

.

In 1899 John Hay

John Milton Hay (October 8, 1838July 1, 1905) was an American statesman and official whose career in government stretched over almost half a century. Beginning as a private secretary and assistant to Abraham Lincoln, Hay's highest office was U ...

, U.S. Secretary of State, asked the American ambassador to Ottoman Turkey, Oscar Straus, to approach Sultan Abdul Hamid II to use his position as caliph to order the Tausūg people

The Tausūg or Suluk ( tsg, Tau Sūg), are an ethnic group of the Philippines and Malaysia. A small population can also be found in the northern part of North Kalimantan, Indonesia. The Tausūg are part of the wider political identity of Musli ...

of the Sultanate of Sulu in the Philippines to submit to American suzerainty and American military rule; the Sultan obliged them and wrote the letter which was sent to Sulu via Mecca. As a result, the "Sulu Mohammedans ... refused to join the insurrectionists and had placed themselves under the control of our army, thereby recognizing American sovereignty."

Abolition of the Caliphate (1924)

After the Armistice of Mudros of October 1918 with the military

After the Armistice of Mudros of October 1918 with the military occupation of Constantinople

The occupation of Istanbul ( tr, İstanbul'un İşgali; 12 November 1918 – 4 October 1923), the capital of the Ottoman Empire, by British, French, Italian, and Greek forces, took place in accordance with the Armistice of Mudros, which ended O ...

and Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

(1919), the position of the Ottomans was uncertain. The movement to protect or restore the Ottomans gained force after the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres (french: Traité de Sèvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

(August 1920) which imposed the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire

The partition of the Ottoman Empire (30 October 19181 November 1922) was a geopolitical event that occurred after World War I and the occupation of Constantinople by British, French and Italian troops in November 1918. The partitioning was ...

and gave Greece a powerful position in Anatolia, to the distress of the Turks. They called for help and the movement was the result. The movement had collapsed by late 1922.

On 3 March 1924, the first President of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 Surname Law (Turkey), until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish Mareşal (Turkey), field marshal, Turkish National Movement, re ...

, as part of his reforms, constitutionally abolished the institution of the caliphate.Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi

Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi ( ar, أحمد الشريف السنوسي) (1873 – 10 March 1933) was the supreme leader of the Senussi order (1902–1933), although his leadership in the years 1917–1933 could be considered nominal. His daughter, ...

, on the condition that he reside outside Turkey; Senussi declined the offer and confirmed his support for Abdulmejid. The title was then claimed

"Claimed" is the eleventh episode of the fourth season of the post-apocalyptic horror television series '' The Walking Dead'', which aired on AMC on February 23, 2014. The episode was written by Nichole Beattie and Seth Hoffman, and directed ...

by Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca and Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Prov ...

, leader of the Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On ...

, but his kingdom was defeated and annexed by ibn Saud

Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud ( ar, عبد العزيز بن عبد الرحمن آل سعود, ʿAbd al ʿAzīz bin ʿAbd ar Raḥman Āl Suʿūd; 15 January 1875Ibn Saud's birth year has been a source of debate. It is generally accepted ...

in 1925.

Egyptian scholar Ali Abdel Raziq

Ali Abdel Raziq ( ar, ﻋﻠﻲ ﻋﺒﺪ ﺍﻟﺮﺍﺯﻕ) (1888–1966) was an Egyptian scholar of Islam, judge and government minister.Marshall Cavendish Reference. Illustrated Dictionary of the Muslim World Muslim World. Marshall Cavendish, ...

published his 1925 book ''Islam and the Foundations of Governance''. The argument of this book has been summarized as "Islam does not advocate a specific form of government". He focussed his criticism both at those who use religious law as contemporary political proscription and at the history of rulers claiming legitimacy by the caliphate.[Bertrand Badie, Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Leonardo Morlino (eds). International Encyclopedia of Political Science, Volume 1. Sage, 2011. p. 1350.] Raziq wrote that past rulers spread the notion of religious justification for the caliphate "so that they could use religion as a shield protecting their thrones against the attacks of rebels".

A summit was convened at Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

in 1926 to discuss the revival of the caliphate, but most Muslim countries did not participate and no action was taken to implement the summit's resolutions. Though the title ''Ameer al-Mumineen'' was adopted by the King of Morocco and by Mohammed Omar, former head of the Taliban

The Taliban (; ps, طالبان, ṭālibān, lit=students or 'seekers'), which also refers to itself by its state (polity), state name, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a Deobandi Islamic fundamentalism, Islamic fundamentalist, m ...

of Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

, neither claimed any legal standing or authority over Muslims outside the borders of their respective countries.

Since the end of the Ottoman Empire, occasional demonstrations have been held calling for the re-establishment of the caliphate. Organisations which call for the re-establishment of the caliphate include Hizb ut-Tahrir

Hizb ut-Tahrir (Arabicحزب التحرير (Translation: Party of Liberation) is an international, political organization which describes its ideology as Islam, and its aim the re-establishment of the Islamic Khilafah (Caliphate) to resume Isl ...

and the Muslim Brotherhood

The Society of the Muslim Brothers ( ar, جماعة الإخوان المسلمين'' ''), better known as the Muslim Brotherhood ( '), is a transnational Sunni Islamist organization founded in Egypt by Islamic studies, Islamic scholar and scho ...

.[Jay Tolson, "Caliph Wanted: Why An Old Islamic Institution Resonates With Many Muslims Today", ''U.S News & World Report'' 144.1 (14 January 2008): 38–40.]

Parallel regional caliphates to the Ottomans

=Indian subcontinent

=

After the

After the Umayyad campaigns in India

In the first half of the 8th century CE, a series of battles took place between the Umayyad Caliphate and kingdoms to the east of the Indus river, in the Indian subcontinent.

Subsequent to the Arab conquest of Sindh in present-day Pakistan in ...

and the conquest on small territories of the western part of the Indian peninsula, early Indian Muslim dynasties were founded by the Ghurid dynasty

The Ghurid dynasty (also spelled Ghorids; fa, دودمان غوریان, translit=Dudmân-e Ğurīyân; self-designation: , ''Šansabānī'') was a Persianate dynasty and a clan of presumably eastern Iranian Tajik origin, which ruled from th ...

and the Ghaznavids

The Ghaznavid dynasty ( fa, غزنویان ''Ġaznaviyān'') was a culturally Persianate, Sunni Muslim dynasty of Turkic ''mamluk'' origin, ruling, at its greatest extent, large parts of Persia, Khorasan, much of Transoxiana and the northwes ...

, most notably the Delhi Sultanate

The Delhi Sultanate was an Islamic empire based in Delhi that stretched over large parts of the Indian subcontinent for 320 years (1206–1526). . The Indian sultanates did not extensively strive for a caliphate since the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

was already observing the caliphate. Although the Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the d ...

is not recognised as a caliphate, its sixth emperor Muhammad Alamgir Aurangzeb has often been regarded as one of the few Islamic caliphs to have ruled the Indian peninsula. He received support from Ottoman Sultans such as Suleiman II and Mehmed IV

Mehmed IV ( ota, محمد رابع, Meḥmed-i rābi; tr, IV. Mehmed; 2 January 1642 – 6 January 1693) also known as Mehmed the Hunter ( tr, Avcı Mehmed) was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1648 to 1687. He came to the throne at the a ...

. As a memorizer of Quran, Aurangzeb fully established sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

in South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;; ...

via his Fatawa 'Alamgiri. He re-introduced jizya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Islamic law. The jizya tax has been understood in ...

and banned Islamically unlawful activities. However, Aurangzeb's personal expenses were covered by his own incomes, which included the sewing of caps and trade of his written copies of the Quran. Thus he has been compared to the 2nd Caliph Umar bin Khattab and Kurdish conqueror Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt an ...

. Other notable rulers such as Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji

Ikhtiyār al-Dīn Muḥammad Bakhtiyār Khaljī, (Pashto :اختيار الدين محمد بختيار غلزۍ, fa, اختیارالدین محمد بختیار خلجی, bn, ইখতিয়ারউদ্দীন মুহম্মদ � ...

, Alauddin Khilji

Alaud-Dīn Khaljī, also called Alauddin Khilji or Alauddin Ghilji (), born Ali Gurshasp, was an emperor of the Khalji dynasty that ruled the Delhi Sultanate in the Indian subcontinent. Alauddin instituted a number of significant administrative ...

, Firuz Shah Tughlaq

Sultan Firuz Shah Tughlaq (1309 – 20 September 1388) was a Muslim ruler from the Tughlaq dynasty, who reigned over the Sultanate of Delhi from 1351 to 1388. , Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah

Haji Ilyas, better known as Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah ( bn, শামসুদ্দীন ইলিয়াস শাহ, fa, ), was the founder of the Sultanate of Bengal and its inaugural Ilyas Shahi dynasty which ruled the region for 150 ye ...

, Babur

Babur ( fa, , lit= tiger, translit= Bābur; ; 14 February 148326 December 1530), born Mīrzā Zahīr ud-Dīn Muhammad, was the founder of the Mughal Empire in the Indian subcontinent. He was a descendant of Timur and Genghis Khan through hi ...

, Sher Shah Suri

Sher Shah Suri ( ps, شیرشاه سوری)

(1472, or 1486 – 22 May 1545), born Farīd Khān ( ps, فرید خان)

, was the founder of the Sur Empire in India, with its capital in Sasaram in modern-day Bihar. He standardized the silver coin ...

, Nasir I of Kalat, Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan (born Sultan Fateh Ali Sahab Tipu, 1 December 1751 – 4 May 1799), also known as the Tiger of Mysore, was the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore based in South India. He was a pioneer of rocket artillery.Dalrymple, p. 243 He i ...

, and the Nawabs of Bengal

The Nawab of Bengal ( bn, বাংলার নবাব) was the hereditary ruler of Bengal Subah in Mughal India. In the early 18th-century, the Nawab of Bengal was the ''de facto'' independent ruler of the three regions of Bengal, Bihar, ...

were popularly given the term Khalifa.

=Bornu Caliphate (1472–1893)

=

The Bornu Caliphate, which was headed by the Bornu Emperors, began in 1472. A rump state of the larger Kanem-Bornu Empire, its rulers held the title of Caliph until 1893, when it was absorbed into the British Colony of Nigeria and Northern Cameroons Protectorate. The British recognized them as the 'Sultans of Bornu', one step down in Muslim royal titles. After Nigeria became independent, its rulers became the 'Emirs of Bornu', another step down.

=Yogyakarta Caliphate (1755–2015)

=

The Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

n Sultan of Yogyakarta historically used ''Khalifatullah'' (Caliph of God) as one of his many titles. In 2015 sultan Hamengkubuwono X renounced any claim to the Caliphate in order to facilitate his daughter's inheritance of the throne, as the theological opinion of the time was that a woman may hold the secular office of sultan but not the spiritual office of caliph.

=Sokoto Caliphate (1804–1903)

=

The Sokoto Caliphate

The Sokoto Caliphate (), also known as the Fulani Empire or the Sultanate of Sokoto, was a Sunni Muslim caliphate in West Africa. It was founded by Usman dan Fodio in 1804 during the Fulani jihads after defeating the Hausa Kingdoms in the F ...

was an Islamic state in what is now Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

led by Usman dan Fodio. Founded during the Fulani War in the early 19th century, it controlled one of the most powerful empires in sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

prior to European conquest and colonisation. The caliphate remained extant through the colonial period and afterwards, though with reduced power. The current head of the Sokoto Caliphate is Sa'adu Abubakar.

=Toucouleur Empire (1848–1893)

=

The Toucouleur Empire, also known as the Tukular Empire, was one of the Fulani jihad states in sub-saharan Africa. It was eventually pacified and annexed by the French Republic

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, being incorporated into French West Africa

French West Africa (french: Afrique-Occidentale française, ) was a federation of eight French colonial territories in West Africa: Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guinea (now Guinea), Ivory Coast, Upper Volta (now B ...

.

=Khilafat Movement (1919–1924)

=

The Khilafat Movement

The Khilafat Movement (1919–24), also known as the Caliphate movement or the Indian Muslim movement, was a pan-Islamist political protest campaign launched by Muslims of British India led by Shaukat Ali, Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar, Hakim ...

was launched by Muslims in British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

in 1920 to defend the Ottoman Caliphate at the end of the First World War and it spread throughout the British colonial territories. It was strong in British India where it formed a rallying point for some Indian Muslims as one of many anti-British Indian political movements. Its leaders included Mohammad Ali Jouhar

Muhammad Ali Jauhar (10 December 1878 – 4 January 1931), was an Indian Muslim activist, prominent member of the All-India Muslim League, journalist and a poet, a leading figure of the Khilafat Movement and one of the founders of Jamia Millia ...

, his brother Shawkat Ali and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad

Abul Kalam Ghulam Muhiyuddin Ahmed bin Khairuddin Al-Hussaini Azad (; 11 November 1888 – 22 February 1958) was an Indian independence activist, Islamic theologian, writer and a senior leader of the Indian National Congress. Following In ...

, Dr. Mukhtar Ahmed Ansari, Hakim Ajmal Khan and Barrister Muhammad Jan Abbasi. For a time it was supported by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, who was a member of the Central Khilafat Committee. However, the movement lost its momentum after the abolition of the Caliphate in 1924. After further arrests and flight of its leaders, and a series of offshoots splintered off from the main organisation, the Movement eventually died down and disbanded.

Sharifian Caliphate (1924–25)

The Sharifian Caliphate ( ar, خلافة شريفية) was an Arab caliphate proclaimed by the Sharifian rulers of Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Prov ...

in 1924 previously known as Vilayet Hejaz, declaring independence from the Ottoman Caliphate

The Caliphate of the Ottoman Empire ( ota, خلافت مقامى, hilâfet makamı, office of the caliphate) was the claim of the heads of the Turkish Ottoman dynasty to be the caliphs of Islam in the late medieval and the early modern era. ...

. The idea of the Sharifian Caliphate had been floating around since at least the 15th century. Toward the end of the 19th century, it started to gain importance due to the decline of the Ottoman Empire, which was heavily defeated in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78. There is little evidence, however, that the idea of a Sharifian Caliphate ever gained wide grassroots support in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

or anywhere else in the Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

.

Non-political caliphates

Though non-political, some Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

orders

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of ...

and the Ahmadiyya movement define themselves as caliphates. Their leaders are thus commonly referred to as ''khalifas'' (caliphs).

Sufi caliphates

In Sufism

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality ...

, tariqa

A tariqa (or ''tariqah''; ar, طريقة ') is a school or order of Sufism, or specifically a concept for the mystical teaching and spiritual practices of such an order with the aim of seeking '' haqiqa'', which translates as "ultimate truth". ...

s (orders) are led by spiritual leaders (khilafah ruhaniyyah), the main khalifas, who nominate local khalifas to organize zaouias.

Sufi caliphates are not necessarily hereditary. Khalifas are aimed to serve the ''silsilah'' in relation to spiritual responsibilities and to propagate the teachings of the tariqa.

Ahmadiyya Caliphate (1908–present)

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community is a self-proclaimed Islamic revivalist movement founded in 1889 by

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community is a self-proclaimed Islamic revivalist movement founded in 1889 by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad

Mirzā Ghulām Ahmad (13 February 1835 – 26 May 1908) was an Indian religious leader and the founder of the Ahmadiyya movement in Islam. He claimed to have been divinely appointed as the promised Messiah and Mahdi—which is the metapho ...

of Qadian, India, who claimed to be the promised Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

and Mahdi

The Mahdi ( ar, ٱلْمَهْدِيّ, al-Mahdī, lit=the Guided) is a messianic figure in Islamic eschatology who is believed to appear at the end of times to rid the world of evil and injustice. He is said to be a descendant of Muhammad w ...

, awaited by Muslims. He also claimed to be a follower-prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the ...

subordinate to Muhammad, the prophet of Islam. The group are traditionally shunned by the majority of Muslims.

After Ahmad's death in 1908, his first successor, Hakeem Noor-ud-Din, became the caliph of the community and assumed the title of ''Khalifatul Masih'' (Successor or Caliph of the Messiah). After Hakeem Noor-ud-Din, the first caliph, the title of the Ahmadiyya caliph continued under Mirza Mahmud Ahmad, who led the community for over 50 years. Following him were Mirza Nasir Ahmad and then Mirza Tahir Ahmad who were the third and fourth caliphs respectively. The current caliph is Mirza Masroor Ahmad, who lives in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

.

Period of dormancy

Once the subject of intense conflict and rivalry amongst Muslim rulers, the caliphate lay dormant and largely unclaimed since the 1920s. For the vast majority of Muslims the caliph, as leader of the ummah

' (; ar, أمة ) is an Arabic word meaning "community". It is distinguished from ' ( ), which means a nation with common ancestry or geography. Thus, it can be said to be a supra-national community with a common history.

It is a synonym for ' ...

, "is cherished both as memory and ideal"[''Washington Post'',]

Reunified Islam: Unlikely but Not Entirely Radical, Restoration of Caliphate resonates With Mainstream Muslims

. as a time when Muslims "enjoyed scientific and military superiority globally". The Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

is reported to have prophesied:

"Kalifatstaat": Federated Islamic State of Anatolia (1994–2001)

The '' Kalifatstaat'' ("Caliphate State") was the name of an Islamist organization in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

that was proclaimed at an event in Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

in 1994 and banned in December 2001 after an amendment to the Association Act, which abolished the religious privilege. However, this caliphate was never institutionalized under international law, but only an intention for an Islamic "state within the state".

The caliphate emerged in 1994 from the "Federated Islamic State of Anatolia" ( tr, Anadolu Federe İslam Devleti, AFİD), which existed in Germany from 1992 to 1994 as the renaming of the Association of Islamic Associations and Municipalities (İCCB). In 1984 the latter split off from the Islamist organization Millî Görüş

Millî Görüş (, "National Outlook" or "National Vision") is a religious-political movement and a series of Islamist parties inspired by Necmettin Erbakan. It argues that Turkey can develop with its own human and economic power by protectin ...

. The leader of the association proclaimed himself the caliph, the worldwide spiritual and worldly head of all Muslims. Since then, the organization has seen itself as a "Caliphate State" ( tr, Hilafet Devleti). From an association law perspective, the old name remained.

The leader was initially Cemalettin Kaplan, who was nicknamed " Khomeini of Cologne" by the German public. In Turkish media he was referred to as the "Dark Voice" ( tr, Kara Ses). At an event in honor of Kaplan in 1993, the German convert to Islam Andreas Abu Bakr Rieger publicly "regretted" in front of hundreds of listeners that the Germans had not completely destroyed the Jews: "Like the Turks, we Germans have often had a good cause in history fought, although I have to admit that my grandfathers weren't thorough with our main enemy."

Abu Issa caliphate (1993 – circa 2014)

A contemporary effort to re-establish the caliphate by supporters of armed jihad that predates Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi ( ar, أبو بكر البغدادي, ʾAbū Bakr al-Baḡdādī; born Ibrahim Awad Ibrahim Ali Muhammad al-Badri al-Samarrai ( ar, إبراهيم عواد إبراهيم علي محمد البدري السامرائي, ʾIb ...

and the Islamic State

An Islamic state is a state that has a form of government based on Islamic law (sharia). As a term, it has been used to describe various historical polities and theories of governance in the Islamic world. As a translation of the Arabic ter ...

and was much less successful, was "the forgotten caliphate" of Muhammad bin ʿIssa bin Musa al Rifaʿi ("known to his followers as Abu ʿIssa"). This "microcaliphate" was founded on 3 April 1993 on the Pakistan-Afghanistan border, when Abu Issa's small number of " Afghan Arabs" followers swore loyalty ( bay'ah) to him.[Wood, ''The Way of the Strangers'', 2017, p.153] Abu Issa, was born in the city of Zarqa, Jordan and like his followers had come to Afghanistan to wage jihad against the Soviets. Unlike them he had ancestors in the tribe of Quraysh