California Republic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The California Republic ( es, La República de California), or Bear Flag Republic, was an unrecognized

Decrees issued by the central government in Mexico City were often acknowledged and supported with proclamations but ignored in practice. By the end of 1845, when rumors of a military force being sent from Mexico proved to be false, rulings by the other district government were mostly ignored.

Decrees issued by the central government in Mexico City were often acknowledged and supported with proclamations but ignored in practice. By the end of 1845, when rumors of a military force being sent from Mexico proved to be false, rulings by the other district government were mostly ignored.

The relationship between the United States and Mexico had been deteriorating for some time. The

The relationship between the United States and Mexico had been deteriorating for some time. The  During November 1845, California's ''Commandante General'' José Castro met with representatives of the 1845 American immigrants at Sonoma and Sutter's Fort. In his decree dated November 6 he wrote: "Therefore conciliating my duty

During November 1845, California's ''Commandante General'' José Castro met with representatives of the 1845 American immigrants at Sonoma and Sutter's Fort. In his decree dated November 6 he wrote: "Therefore conciliating my duty

A 62-man exploring and mapping expedition entered California in late 1845 under the command of U.S. Army Brevet Captain

A 62-man exploring and mapping expedition entered California in late 1845 under the command of U.S. Army Brevet Captain

U.S. Consul Thomas O. Larkin, concerned about the increasing possibility of war, sent a request to

U.S. Consul Thomas O. Larkin, concerned about the increasing possibility of war, sent a request to

Historian George Tays has cautioned "The description of the men, their actions just prior and subsequent to the taking of Sonoma, are as varied as the number of authors. No two accounts agree, and it is impossible to determine the truth of their statements." Historian H. H. Bancroft has written that Frémont "instigated and planned" the horse raid, and incited the American settlers indirectly and "guardedly" to revolt.Walker p. 121

Before dawn on Sunday, June 14, 1846, over 30 American insurgents arrived at the pueblo of Sonoma. They had traveled overnight from Napa Valley. A majority of their number had started a couple of days earlier from Fremont's camp in the Sacramento valley but others had joined the group along the way. Meeting no resistance, they approached ''Comandante'' Vallejo's home and pounded on his door. After a few minutes Vallejo opened the door dressed in his Mexican Army uniform. Communication was not good until American

Historian George Tays has cautioned "The description of the men, their actions just prior and subsequent to the taking of Sonoma, are as varied as the number of authors. No two accounts agree, and it is impossible to determine the truth of their statements." Historian H. H. Bancroft has written that Frémont "instigated and planned" the horse raid, and incited the American settlers indirectly and "guardedly" to revolt.Walker p. 121

Before dawn on Sunday, June 14, 1846, over 30 American insurgents arrived at the pueblo of Sonoma. They had traveled overnight from Napa Valley. A majority of their number had started a couple of days earlier from Fremont's camp in the Sacramento valley but others had joined the group along the way. Meeting no resistance, they approached ''Comandante'' Vallejo's home and pounded on his door. After a few minutes Vallejo opened the door dressed in his Mexican Army uniform. Communication was not good until American

Frémont's "field-lieutenant" Merritt returned to Sacramento (known as New Helvetia at the time, so named by the Swiss John Sutter) on June 16 with his prisoners and recounted the events in Sonoma. Frémont either was fearful of going against the popular sentiment at Sonoma or saw the advantages of holding the ''Californio'' officers as hostages. He also decided to imprison Governor Vallejo's brother-in-law, the American Jacob Leese, in

Frémont's "field-lieutenant" Merritt returned to Sacramento (known as New Helvetia at the time, so named by the Swiss John Sutter) on June 16 with his prisoners and recounted the events in Sonoma. Frémont either was fearful of going against the popular sentiment at Sonoma or saw the advantages of holding the ''Californio'' officers as hostages. He also decided to imprison Governor Vallejo's brother-in-law, the American Jacob Leese, in

Two days later, July 9, the Bear Flag Revolt and whatever remained of the "California Republic" ended when Navy Lieutenant Joseph Revere was sent to Sonoma from the USS ''Portsmouth'', which had been berthed at

Two days later, July 9, the Bear Flag Revolt and whatever remained of the "California Republic" ended when Navy Lieutenant Joseph Revere was sent to Sonoma from the USS ''Portsmouth'', which had been berthed at

The most notable legacy of the "California Republic" was the adoption of its flag as the basis of the modern state

The most notable legacy of the "California Republic" was the adoption of its flag as the basis of the modern state

newspaper article

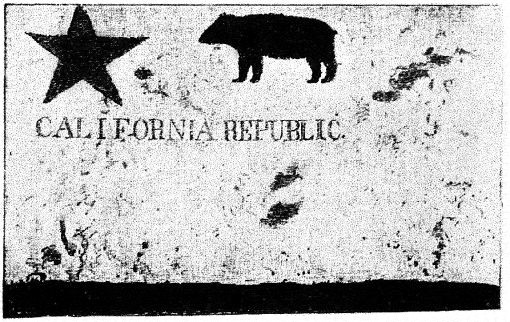

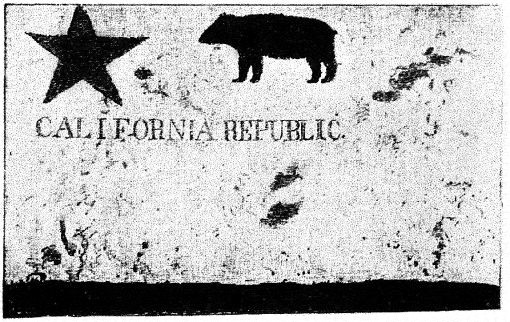

Todd painted the flag on domestic cotton cloth, roughly a yard and a half in length. It featured a red star based on the California Lone Star Flag that was flown during California's 1836 revolt led by Juan Alvarado and

''History of California, VOL. V. 1846–1848''

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

( U.S. National Park Service) *

Frémont in the Conquest of California

, ''The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine'', vol. XLI, no. 4, February 1891

The Bear Flag Museum

Modern representation of the flag as designed by William Todd.

{{Authority control * Rebellions in North America

breakaway state

Breakaway or Break Away may refer to:

Film, television and radio

* ''Breakaway'' (1955 film), a British film

* ''Breakaway'' (1990 film), an Australian film featuring Deborah Kara Unger

* ''Breakaway'' (1996 film), an American film featuring T ...

from Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

, that for 25 days in 1846 militarily controlled an area north of San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

, in and around what is now Sonoma County

Sonoma County () is a county located in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 United States Census, its population was 488,863. Its county seat and largest city is Santa Rosa. It is to the north of Marin County and the south of Mendocino ...

in California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

.

In June 1846, thirty-three American immigrants in Alta California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

who had entered without official permissionBancroft; IV: 598–608 rebelled against the Mexican department's"Department" was a territorial and administrative designation used by Mexico's centralized government under the Seven Laws of 1836. government. Among their grievances were that they had not been allowed to buy or rent land and had been threatened with expulsion.Richman p 308 Mexican officials had been concerned about a coming war with the United States and the growing influx of Americans into California. The rebellion was covertly encouraged by U.S. Army Brevet Captain John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

, and added to the troubles of the recent outbreak of the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

.

The name "California Republic" appeared only on the flag the insurgents

An insurgency is a violent, armed rebellion against authority waged by small, lightly armed bands who practice guerrilla warfare from primarily rural base areas. The key descriptive feature of insurgency is its asymmetric nature: small irr ...

raised in Sonoma. It indicated their aspiration of forming a republican government under their control. The rebels elected military officers but no civil structure was ever established.Harlow p. 103 Their flag, featuring a silhouette of a California grizzly bear

The California grizzly bear (''Ursus arctos californicus'') is an extinct population or subspecies of the brown bear, generally known (together with other North American brown bear populations) as the grizzly bear. "Grizzly" could have meant " ...

, became known as the Bear Flag and was later the basis for the official state flag of California.

Three weeks later, on July 5, 1846, the Republic's military of 100 to 200 men was subsumed into the California Battalion

The California Battalion (also called the first California Volunteer Militia and U.S. Mounted Rifles) was formed during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) in present-day California, United States. It was led by U.S. Army Brevet Lieutenant C ...

commanded by Brevet Captain John C. Frémont. The Bear Flag Revolt

The California Republic ( es, La República de California), or Bear Flag Republic, was an unrecognized breakaway state from Mexico, that for 25 days in 1846 militarily controlled an area north of San Francisco, in and around what is now S ...

and whatever remained of the "California Republic" ceased to exist on July 9 when U.S. Navy Lieutenant Joseph Revere raised the United States flag in front of the Sonoma Barracks

The Sonoma Barracks (Spanish: ''Cuartel de Sonoma'') is a two-story, wide-balconied, adobe building facing the central plaza of the City of Sonoma, California. It was built by order of Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo to house the Mexican soldiers that ...

and sent a second flag to be raised at Sutter's Fort

Sutter's Fort was a 19th-century agricultural and trade colony in the Mexican '' Alta California'' province.National Park Service"California National Historic Trail."/ref> The site of the fort was established in 1839 and originally called New Hel ...

.

Background of the Bear Flag Revolt

Alta California's Governance

By 1845–46, Alta California had been largely neglected by Mexico for the twenty-five years since Mexican independence. It had evolved into a semi-autonomous region with open discussions amongCalifornio

Californio (plural Californios) is a term used to designate a Hispanic Californian, especially those descended from Spanish and Mexican settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries. California's Spanish-speaking community has resided there sin ...

s about whether California should remain with Mexico; seek independence; or become annexed to the United Kingdom, France, or the United States. In 1845, the widely hated Manuel Micheltorena

Joseph Manuel María Joaquin Micheltorena y Llano (8 June 1804 – 7 September 1853) was a brigadier general of the Mexican Army, adjutant-general of the same, governor, commandant-general and inspector of the department of Las Californias, t ...

, the latest governor to be sent by Mexico, was forcefully ejected by the Californians. His forces were defeated at the Battle of Providencia

Battle of Providencia (also called the "Second Battle of Cahuenga Pass") took place in Cahuenga Pass in 1845 on Rancho Providencia in the San Fernando Valley, north of Los Angeles, California. Native ''Californios'' successfully challenged Me ...

(also known as the Second Battle of Cahuenga Pass

The Cahuenga Pass (, ; Tongva: ''Kawé’nga'') is a low mountain pass through the eastern end of the Santa Monica Mountains in the Hollywood Hills district of the City of Los Angeles, California. It has an elevation of . The Cahuenga Pass connec ...

) as a result of the actions of California pioneer John Marsh John Marsh may refer to:

Politicians

* John Marsh (MP fl. 1394–1397), MP for Bath

* John Marsh (MP fl. 1414–1421), MP for Bath

*John Allmond Marsh (1894–1952), Canadian Member of Parliament

* John Otho Marsh Jr. (1926–2019), American c ...

. This resulted in the return of Californian Pio Pico

Pio may refer to:

Places

* Pio Lake, Italy

* Pio Island, Solomon Islands

* Pio Point, Bird Island, south Atlantic Ocean

People

* Pio (given name)

* Pio (surname)

* Pio (footballer, born 1986), Brazilian footballer

* Pio (footballer, born 1 ...

to the governorship. Pico ruled the region south of San Luis Obispo

San Luis Obispo (; Spanish for " St. Louis the Bishop", ; Chumash: ''tiłhini'') is a city and county seat of San Luis Obispo County, in the U.S. state of California. Located on the Central Coast of California, San Luis Obispo is roughly hal ...

with his capital in ''The Town of Our Lady the Queen of Angels of the Porciúncula River'', now known as Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

. The area to the north of the pueblo of San Luis Obispo

San Luis Obispo (; Spanish for " St. Louis the Bishop", ; Chumash: ''tiłhini'') is a city and county seat of San Luis Obispo County, in the U.S. state of California. Located on the Central Coast of California, San Luis Obispo is roughly hal ...

was under the control of Alta California's ''Commandante'' José Castro

José Antonio Castro (1808 – February 1860) was a Californio politician, statesman, and general who served as interim Governor of Alta California and later Governor of Baja California. During the Bear Flag Revolt and the American Conquest of ...

with headquarters near Monterey

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under bot ...

, the traditional capital and, significantly, the location of the Customhouse. Pico and Castro disliked each other personally and soon began escalating disputes over control of the Customhouse income.

Decrees issued by the central government in Mexico City were often acknowledged and supported with proclamations but ignored in practice. By the end of 1845, when rumors of a military force being sent from Mexico proved to be false, rulings by the other district government were mostly ignored.

Decrees issued by the central government in Mexico City were often acknowledged and supported with proclamations but ignored in practice. By the end of 1845, when rumors of a military force being sent from Mexico proved to be false, rulings by the other district government were mostly ignored.

Texas, immigration and land

The relationship between the United States and Mexico had been deteriorating for some time. The

The relationship between the United States and Mexico had been deteriorating for some time. The Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas ( es, República de Tejas) was a sovereign state in North America that existed from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846, that bordered Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande in 1840 (another breakaway republic from Me ...

, which Mexico still considered to be its territory, had been admitted to statehood in 1845. Mexico had earlier threatened war if this happened.Walker p. 60 James K. Polk was elected President of the United States in 1844, and considered his election a mandate for his expansionist policies.

Mexican law had long allowed grants of land to naturalized

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-citizen of a country may acquire citizenship or nationality of that country. It may be done automatically by a statute, i.e., without any effort on the part of the in ...

Mexican citizens. Obtaining Mexican citizenship was not difficult and many earlier American immigrants had gone through the process and obtained free grants of land. That same year (1845) anticipation of war with the United States and the increasing number of immigrants reportedly coming from the United States resulted in orders from Mexico City denying immigrants from the United States entry into California. The orders also required California's officials not to allow land grants, sales or even rental of land to non-citizen emigrants already in California. All non-citizen immigrants, who had arrived without permission, were threatened with being forced out of California.

Alta California's Sub-Prefect Francisco Guerrero Francisco Guerrero is the name of:

*Francisco Guerrero (composer) (1528–1599), Spanish composer of the Renaissance

*Francisco Guerrero (politician) (1811–1851), Alcalde of San Francisco

*Francisco Guerrero Marín (1951–1997), Spanish composer ...

had written to U.S. Consul Thomas O. Larkin that:

During November 1845, California's ''Commandante General'' José Castro met with representatives of the 1845 American immigrants at Sonoma and Sutter's Fort. In his decree dated November 6 he wrote: "Therefore conciliating my duty

During November 1845, California's ''Commandante General'' José Castro met with representatives of the 1845 American immigrants at Sonoma and Sutter's Fort. In his decree dated November 6 he wrote: "Therefore conciliating my duty o enforce the orders from Mexico

O, or o, is the fifteenth letter and the fourth vowel letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''o'' (pronounced ), plu ...

with of the sentiment of hospitality which distinguishes the Mexicans, and considering that most of said expedition is composed of families and industrious people, I have deemed it best to permit them, provisionally, to remain in the department" with the conditions that they obey all laws, apply within three months for a license to settle, and promise to depart if that license was not granted.

Captain Frémont in California

John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

. Frémont was well known in the United States as an author and explorer. He was also the son-in-law of expansionist U.S. Senator Thomas Hart Benton. Early in 1846 Frémont acted provocatively with California's ''Commandante General'' José Castro near the pueblo of Monterey

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under bot ...

and then moved his group out of California into Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been created by the Treaty of 1818, co ...

. He was followed into Oregon by U.S. Marine Lt Archibald H. Gillespie

Major Archibald H. Gillespie (October 10, 1812 – August 16, 1873) was an officer in the United States Marine Corps during the Mexican–American War.

Biography

Born in New York City, Gillespie was commissioned in the Marine Corps in 1832. He co ...

who had been sent from Washington with a secret message to U.S. Consul Thomas O. Larkin and instructions to share the message with Frémont. Gillespie also brought a packet of letters from Frémont's wife and father-in-law.

Frémont's thoughts (as related in his book, written forty years later) after reading the message and letters were: "I saw the way opening clear before me. War with Mexico was inevitable; and a grand opportunity presented itself to realize in their fullest extent the far-sighted views of Senator Benton. I resolved to move forward on the opportunity and return forthwith to the Sacramento valley

, photo =Sacramento Riverfront.jpg

, photo_caption= Sacramento

, map_image=Map california central valley.jpg

, map_caption= The Central Valley of California

, location = California, United States

, coordinates =

, boundaries = Sierra Nevada (ea ...

in order to bring to bear all the influence I could command." Nevertheless, Frémont needed to be circumspect. As a military officer he could face court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

for violating the Neutrality Act of 1794

The Neutrality Act of 1794 was a United States law which made it illegal for a United States citizen to wage war against any country at peace with the United States.

The Act declares in part:

If any person shall within the territory or jurisdic ...

that made it illegal for an American to wage war against another country at peace with the United States. The next morning Gillespie and Frémont's group departed for California. Frémont returned to the Sacramento Valley and set up camp near Sutter Buttes

The Sutter Buttes (Maidu: ''Histum Yani'' or ''Esto Yamani'', Wintun: ''Olonai-Tol'', Nisenan: ''Estom Yanim'') are a small circular complex of eroded volcanic lava domes which rise as buttes above the flat plains of the Sacramento Valley in Su ...

.

USS ''Portsmouth'' in the San Francisco Bay

U.S. Consul Thomas O. Larkin, concerned about the increasing possibility of war, sent a request to

U.S. Consul Thomas O. Larkin, concerned about the increasing possibility of war, sent a request to Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore ...

John D. Sloat of U.S. Navy's Pacific Squadron

The Pacific Squadron was part of the United States Navy squadron stationed in the Pacific Ocean in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Initially with no United States ports in the Pacific, they operated out of storeships which provided naval s ...

, for a warship to protect U.S. citizens and interests in Alta California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

. In response, the arrived at Monterey

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under bot ...

on April 22, 1846. After receiving information about Frémont's returning to California, Consul Larkin and ''Portsmouth's'' captain John Berrien Montgomery decided the ship should move into the San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water f ...

. She sailed from Monterey on June 1.

Lt. Gillespie, having returned from the Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been created by the Treaty of 1818, co ...

and his meeting with Frémont on June 7, found ''Portsmouth'' moored at Sausalito

Sausalito (Spanish for "small willow grove") is a city in Marin County, California, United States, located southeast of Marin City, south-southeast of San Rafael, and about north of San Francisco from the Golden Gate Bridge.

Sausalito's ...

. He carried a request for money, materiel and supplies for Frémont's group. The requested resupplies were taken by the ship's launch up the Sacramento River

The Sacramento River ( es, Río Sacramento) is the principal river of Northern California in the United States and is the largest river in California. Rising in the Klamath Mountains, the river flows south for before reaching the Sacramento� ...

to a location near Frémont's camp.

Bear Flag Revolt

Settlers meet with Frémont

William B. Ide, a future leader of the Revolt, writes of receiving an unsigned written message on June 8, 1846: "Notice is hereby given, that a large body of armed Spaniards on horseback, amounting to 250 men, have been seen on their way to the Sacramento Valley, destroying crops and burning houses, and driving off the cattle. Capt. Fremont invites every freeman in the valley to come to his camp at the Butts ic immediately; and he hopes to stay the enemy and put a stop to his" – (Here the sheet was folded and worn in-two, and no more is found). Ide and other settlers quickly traveled to Frémont's camp but were generally dissatisfied by the lack of a specific plan and their inability to obtain from Frémont any definite promise of aid.Taking of government horses

Some of the group who had been meeting with Frémont departed from his camp and, on June 10, 1846, captured a herd of 170 Mexican government-owned horses being moved by ''Californio

Californio (plural Californios) is a term used to designate a Hispanic Californian, especially those descended from Spanish and Mexican settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries. California's Spanish-speaking community has resided there sin ...

'' soldiers from San Rafael and Sonoma to the Californian ''Commandante General'', José Castro

José Antonio Castro (1808 – February 1860) was a Californio politician, statesman, and general who served as interim Governor of Alta California and later Governor of Baja California. During the Bear Flag Revolt and the American Conquest of ...

, in Santa Clara. It had been reported amongst the emigrants that the officer in charge of the herd had made statements threatening that the horses would be used by Castro to drive the foreigners out of California. The captured horses were taken to Frémont's new camp at the junction of the Feather and Bear rivers.

These men next determined to seize the ''pueblo'' of Sonoma to deny the ''Californios'' a rallying point north of San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water f ...

.Bancroft V:109 Capturing both the arms and military materiel stored in the unmanned Presidio of Sonoma

The Sonoma Barracks ( Spanish: ''Cuartel de Sonoma'') is a two-story, wide-balconied, adobe building facing the central plaza of the City of Sonoma, California. It was built by order of Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo to house the Mexican soldiers tha ...

and Mexican Lieutenant Colonel Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo

Don (honorific), Don Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo (4 July 1807 – 18 January 1890) was a Californios, Californio general, statesman, and public figure. He was born a subject of Spain, performed his military duties as an officer of the Republic of ...

would delay any military response from the ''Californios''. The insurgent group was nominally led by Ezekiel "Stuttering Zeke" Merritt, whom Frémont described as his "field-lieutenant" and lauded for not questioning him.

Capture of Sonoma

Jacob P. Leese

Jacob Primer Leese (August 19, 1809 – February 1, 1892), known in Spanish as Don Jacobo Leese, was an Ohio-born Californian ranchero, entrepreneur, and public servant. He was an early resident of San Francisco and married into the family of pr ...

(Vallejo's brother-in-law) was summoned to translate.

Vallejo then invited the filibusters' leaders into his home to negotiate terms. Two other Californio officers and Leese joined the negotiations. The insurgents waiting outside sent elected "captains" John Grigsby and William Ide inside to speed the proceedings. The effect of Vallejo's hospitality in the form of wine and brandy for the negotiators and someone else's barrel of ''aguardiente

( Spanish), or ( Portuguese) ( eu, pattar; ca, aiguardent; gl, augardente), is a generic term for alcoholic beverages that contain between 29% and 60% alcohol by volume (ABV). It originates in the Iberian Peninsula (Portugal and Spain) and in ...

'' for those outside is debatable. However, when the agreement was presented to those outside they refused to endorse it. Rather than releasing the Mexican officers under parole they insisted they be held as hostages. John Grigsby refused to remain as leader of the group, stating he had been deceived by Frémont. William Ide gave an impassioned speech urging the rebels to stay in Sonoma and start a new republic. Referring to the stolen horses Ide ended his oration with "Choose ye this day what you will be! We are robbers, or we ''must'' be conquerors!"

At that time, Vallejo and his three associates were placed on horseback and taken to Frémont accompanied by eight or nine of the insurgents who did not favor forming a new republic under the circumstances. That night they camped at the Vaca Rancho. Some young Californio ''vigilantes'' under Juan Padilla evaded the guards, aroused Vallejo and offered to help him escape. Vallejo declined, wanting to avoid any bloodshed and anticipating that Frémont would release him on parole.

The Sonoma Barracks

The Sonoma Barracks (Spanish: ''Cuartel de Sonoma'') is a two-story, wide-balconied, adobe building facing the central plaza of the City of Sonoma, California. It was built by order of Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo to house the Mexican soldiers that ...

became the headquarters for the remaining twenty-four rebels, who within a few days created their Bear Flag (see the "Bear Flag" section below). After the flag was raised Californio

Californio (plural Californios) is a term used to designate a Hispanic Californian, especially those descended from Spanish and Mexican settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries. California's Spanish-speaking community has resided there sin ...

s called the insurgents ''Los Osos'' (The Bears) and "Bear Flaggers" because of their flag and in derision of their often scruffy appearance. The rebels embraced the expression, and their uprising, which they originally called the ''Popular Movement'', became known as the ''Bear Flag Revolt''. Henry L. Ford was elected First Lieutenant of the company and obtained promises of obedience to orders. Samuel Kelsey was elected Second Lieutenant, Grandville P. Swift and Samuel Gibson Sergeants.

Ide's proclamation

During the night of June 14–15, 1846 (below), William B. Ide wrote a proclamation announcing and explaining the reasons for the revolt. There were additional copies and some more moderate versions (produced in both English and Spanish) distributed around northern California through June 18.Rogers, ''Ide'' p. 82, Appendix ANeed for gunpowder

A major problem for the Bears in Sonoma was the lack of sufficientgunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

to defend against the expected Mexican attack. William Todd was dispatched on Monday the fifteenth, with a letter to be delivered to the USS ''Portsmouth'' telling of the events in Sonoma and describing themselves as "fellow country men". Todd, having been instructed not to repeat any of the requests in the letter (refers to their need for gunpowder), disregarded that and voiced the request for gunpowder. Captain Montgomery, while sympathetic, declined because of his country's neutrality. Todd, José de Rosa (the messenger Vallejo sent to Montgomery), and U.S. Navy Lieutenant John S. Misroon returned to Sonoma in the Portsmouth's launch the morning of the 16th. Misroon's mission was, without interfering with the revolt, to prevent violence to noncombatants.

Todd was given a second assignment. He was sent to Bodega Bay with an unnamed companion (sometimes called 'the Englishman') to obtain powder from American settlers in that area.Walker p. 132 On June 18, Bears Thomas Cowie and George Fowler were sent to ''Rancho Sotoyome'' (near current-day Healdsburg, California) to pick up a cache of gunpowder from Moses Carson, brother of Frémont's scout Kit Carson

Christopher Houston Carson (December 24, 1809 – May 23, 1868) was an American frontiersman. He was a fur trapper, wilderness guide, Indian agent, and U.S. Army officer. He became a frontier legend in his own lifetime by biographies and ...

.

Sutter's Fort

Frémont's "field-lieutenant" Merritt returned to Sacramento (known as New Helvetia at the time, so named by the Swiss John Sutter) on June 16 with his prisoners and recounted the events in Sonoma. Frémont either was fearful of going against the popular sentiment at Sonoma or saw the advantages of holding the ''Californio'' officers as hostages. He also decided to imprison Governor Vallejo's brother-in-law, the American Jacob Leese, in

Frémont's "field-lieutenant" Merritt returned to Sacramento (known as New Helvetia at the time, so named by the Swiss John Sutter) on June 16 with his prisoners and recounted the events in Sonoma. Frémont either was fearful of going against the popular sentiment at Sonoma or saw the advantages of holding the ''Californio'' officers as hostages. He also decided to imprison Governor Vallejo's brother-in-law, the American Jacob Leese, in Sutter's Fort

Sutter's Fort was a 19th-century agricultural and trade colony in the Mexican '' Alta California'' province.National Park Service"California National Historic Trail."/ref> The site of the fort was established in 1839 and originally called New Hel ...

. Frémont recounts in his memoirs, "Affairs had now assumed a critical aspect and I presently saw that the time had come when it was unsafe to leave events to mature under unfriendly, or mistaken, direction … I knew the facts of the situation. These I could not make known, but felt warranted in assuming the responsibility and acting on my own knowledge."

Frémont's artist and cartographer on his third expedition, Edward Kern

Edward Meyer Kern (October 26, 1822 or 1823 – November 25, 1863) was an American artist, topographer, and explorer of California, the Southwestern United States, and East Asia. He is the namesake of the Kern River and Kern County, California.

...

, was placed in command of Sutter's Fort and its company of dragoons by Frémont. That left John Sutter

John Augustus Sutter (February 23, 1803 – June 18, 1880), born Johann August Sutter and known in Spanish as Don Juan Sutter, was a Swiss immigrant of Mexican and American citizenship, known for establishing Sutter's Fort in the area th ...

the assignment as lieutenant of the dragoons at $50 a month, and second in command of his own fort.

While in command there news of the stranded Donner Party

The Donner Party, sometimes called the Donner–Reed Party, was a group of American pioneers who migrated to California in a wagon train from the Midwest. Delayed by a multitude of mishaps, they spent the winter of 1846–1847 snowbound in th ...

reached Kern; Sutter's Fort had been their unreached destination. Kern vaguely promised the federal government would do something for a rescue party across the Sierra, but had no authority to pay anyone. He was later criticized for his mismanagement delaying the search.

Castro's response

Word of the taking of the government horses, the capture of Sonoma, and the imprisonment of the Mexican officers atSutter's Fort

Sutter's Fort was a 19th-century agricultural and trade colony in the Mexican '' Alta California'' province.National Park Service"California National Historic Trail."/ref> The site of the fort was established in 1839 and originally called New Hel ...

soon reached ''Commandante General'' José Castro

José Antonio Castro (1808 – February 1860) was a Californio politician, statesman, and general who served as interim Governor of Alta California and later Governor of Baja California. During the Bear Flag Revolt and the American Conquest of ...

at his headquarters in Santa Clara. He issued two proclamations on June 17. The first asked the citizens of California to come to the aid of their country. The second promised protection for all foreigners not involved in the revolt. A group of 50–60 militia under command of Captain Joaquin de la Torre traveled up to San Pablo and, by boat, westward across the San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water f ...

to Point San Quentin on the 23rd. Two additional divisions with a total of about 100 men arrived at San Pablo on June 27.Bancroft V:132–136

Battle of Olúmpali

On June 20 when the procurement parties failed to return as expected, Lieutenant Ford sent Sergeant Gibson with four men to ''Rancho Sotoyome''. Gibson obtained the powder and on the way back fought with several Californians and captured one of them. From the prisoner they learned that Cowie and Fowler had died. There areCalifornio

Californio (plural Californios) is a term used to designate a Hispanic Californian, especially those descended from Spanish and Mexican settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries. California's Spanish-speaking community has resided there sin ...

and ''Oso'' versions of what had happened. Ford also learned that William Todd and his companion had been captured by the Californio

Californio (plural Californios) is a term used to designate a Hispanic Californian, especially those descended from Spanish and Mexican settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries. California's Spanish-speaking community has resided there sin ...

irregulars led by Juan Padilla and José Ramón Carrillo.

Ford writes, in his biography, that before leaving Sonoma to search for the other two captives and Padilla's men, he sent a note to Ezekiel Merritt in Sacramento asking him to gather volunteers to help defend Sonoma. Ide's version is that Ford wrote to Frémont saying that the Bears had lost confidence in Ide's leadership. In either case, Ford then rode toward Santa Rosa with seventeen to nineteen Bears. Not finding Padilla, the Bears headed toward one of his homes near Two Rock

Two Rock (; archaic: Black Mountain; ' ()) is a mountain in Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown, Ireland. It is high and is the 382nd highest mountain in Ireland. It is the highest point of the group of hills in the Dublin Mountains which comprises T ...

. The following morning the Bears captured three or four men near the Rancho Laguna de San Antonio and unexpectedly discovered what they assumed was Juan Padilla's group near the Indian rancho of Olúmpali.Harlow pp. 108–9 Ford approached the adobe but more men appeared and others came "pouring out of the adobe". Militiamen from south of the Bay, led by Mexican Captain Joaquin de la Torre, had joined with Padilla's irregulars and now numbered about seventy. Ford's men positioned themselves in a grove of trees and opened fire when the enemy charged on horseback, killing one Californio and wounding another. During the ensuing long-range battle, William Todd and his companion escaped from the house where they were being held and ran to the Bears. The Californios disengaged from the long-range fighting after suffering a few wounded and returned to San Rafael. A Californian militiaman reported that their muskets could not shoot as far as the rifles used by some Bears. This was the only battle fought during the Bear Flag Revolt.

The deaths of Cowie and Fowler, as well as the lethal battle, raised the anxiety of both the Californios, who left the area for safety, and the immigrants, who moved into Sonoma to be under the protection of the muskets and cannon that had been taken from the Sonoma Barracks

The Sonoma Barracks (Spanish: ''Cuartel de Sonoma'') is a two-story, wide-balconied, adobe building facing the central plaza of the City of Sonoma, California. It was built by order of Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo to house the Mexican soldiers that ...

. This increased the number in Sonoma to about two hundred. Some immigrant families were housed in the Barracks, others in the homes of the Californios.

Frémont arrives to defend Sonoma

Having learned of Ford's request for volunteers to defend Sonoma and hearing reports that General Castro was preparing an attack, Frémont left his camp near Sutter's Fort for Sonoma on June 23. With him were ninety men – his own party plus trappers and settlers under Samuel J. Hensley. Frémont would say in his memoirs that he wrote a letter of resignation from the Army and sent it to his father-in-law Thomas Hart Benton in case the government should wish to disavow his action. They arrived at Sonoma in the early morning of the 25th and by noon were on their way to San Rafael accompanied by a contingent of Bears under Ford's command. They arrived at the former San Rafael mission but the Californios had vanished. The rebels set up camp in the old mission and sent out scouting parties. On Sunday the 28th a small boat was spotted coming across the bay. Kit Carson and some companions went to intercept it. It held twin brothers Francisco and Ramón de Haro, their uncle José de la Reyes Berreyesa, and an oarsman (probably one of the Castro brothers from San Pablo) – all unarmed. The Haro brothers and Berreyesa were dropped off at the shoreline and started on foot for the mission. All three were shot and killed. Beyond that almost every fact is disputed. Some say Frémont ordered the killings. Others, that they were carrying secret messages from Castro to Torre. Others that Carson committed the homicides as revenge for the deaths of Cowie and Fowler or they were shot by Frémont's Delaware Indians. This incident became an issue in Frémont's later campaign for President. Partisan eyewitnesses and newspapers related totally conflicting stories.Captain de la Torre's ruse

Late the same afternoon as the killings, a scouting party intercepted a letter indicating that Torre intended to attack Sonoma the following morning. Frémont felt there was no choice but to return to defend Sonoma as quickly as possible. The garrison there had found a similar letter and had all weapons loaded and at the ready before dawn the next day when Frémont and Ford's forces approached Sonoma – almost provoking firing by the garrison. Frémont, understanding that he had been tricked, left again for San Rafael after a hasty breakfast. He arrived back at the old mission within twenty-four hours of leaving but during that period Torre and his men had time to escape to San Pablo via boat. Torre had successfully used the ruse not only to escape but almost succeeded in provoking a 'friendly fire' incident among the insurgents. After reaching San Pablo, Torre reported that the combined rebel force was too strong to be attacked as planned. All three of Castro's divisions then returned to the old headquarters near Santa Clara where a council of war was held on June 30. It was decided that the current plan must be abandoned and any new approach would require the cooperation of Pio Pico and his southern forces. A messenger was sent to the Governor. Meanwhile, the army moved southwards toSan Juan San Juan, Spanish for Saint John, may refer to:

Places Argentina

* San Juan Province, Argentina

* San Juan, Argentina, the capital of that province

* San Juan, Salta, a village in Iruya, Salta Province

* San Juan (Buenos Aires Underground), ...

where General Castro was, on July 6, when he learned of the events in Monterey.

Actions in and around Yerba Buena

On July 1, Frémont and twelve men convinced Captain William Phelps to ferry them in the ''Moscows launch to the old Spanish fort at the entrance to theGolden Gate

The Golden Gate is a strait on the west coast of North America that connects San Francisco Bay to the Pacific Ocean. It is defined by the headlands of the San Francisco Peninsula and the Marin Peninsula, and, since 1937, has been spanned by t ...

. They landed without resistance and spiked the ten old, abandoned cannon. The next day Robert B. Semple Doctor Robert Baylor Semple (1806–1854) was a 19th-century California newspaperman and politician.

Biography

A newspaperman in Kentucky, he came west over the California Trail with Lansford Hastings in 1845, before the gold rush. During the 1846 ...

led ten Bears in the launch to the pueblo of Yerba Buena (the future San Francisco) to arrest the naturalized Englishman Robert Ridley who was captain of the port. Ridley was sent to Sutter's Fort to be locked up with other prisoners.

Independence Day, 1846, in Sonoma

A great celebration was held on theFourth of July

Independence Day (colloquially the Fourth of July) is a federal holiday in the United States commemorating the Declaration of Independence, which was ratified by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, establishing the United States ...

beginning with readings of the United States Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronouncement and founding document adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at Pennsylvania State House ( ...

in Sonoma's plaza. There were also cannon salutes, the roasting of whole beeves, and the consumption of many foods and all manner of beverages. Frémont and the contingent from San Rafael arrived in time for the fandango

Fandango is a lively partner dance originating from Portugal and Spain, usually in triple meter, traditionally accompanied by guitars, castanets, or hand-clapping. Fandango can both be sung and danced. Sung fandango is usually bipartite: it has ...

held in Salvador Vallejo's big adobe on the corner of the town square.

Formation of the California Battalion

On July 5, Frémont called a public meeting and proposed to the Bears that they unite with his party and form a single military unit. He said that he would accept command if they would pledge obedience, proceed honorably, and not violate the chastity of women. A compact was drawn up which all volunteers of theCalifornia Battalion

The California Battalion (also called the first California Volunteer Militia and U.S. Mounted Rifles) was formed during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) in present-day California, United States. It was led by U.S. Army Brevet Lieutenant C ...

signed or made their marks. A majority of those present also agreed to officially date the era of independence not from the taking of Sonoma but from July 5 to allow Frémont to "begin at the beginning".

The next day Frémont, leaving the fifty men of Company B at the Barracks to defend Sonoma, left with the rest of the Battalion for Sutter's Fort. They took with them two of the captured Mexican field pieces, as well as muskets, a supply of ammunition, blankets, horses, and cattle. The seven-ton ''Mermaid'' was used for transporting the cannon, arms, ammunition and saddles from Napa to Sutter's Fort.

U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps capture Monterey

The war against Mexico had already been declared by the United States Congress on May 13, 1846. Because of the slow cross-continent communication of the time, no one in California knew that conclusively. (Official notice of the war finally reached California on August 12, 1846.)Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore ...

John D. Sloat, commanding the U.S. Navy's Pacific Squadron

The Pacific Squadron was part of the United States Navy squadron stationed in the Pacific Ocean in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Initially with no United States ports in the Pacific, they operated out of storeships which provided naval s ...

, had been waiting in Monterey Bay

Monterey Bay is a bay of the Pacific Ocean located on the coast of the U.S. state of California, south of the San Francisco Bay Area and its major city at the south of the bay, San Jose. San Francisco itself is further north along the coast, by ...

since July 1 or 2 to obtain convincing proof of war. Sloat was 65 years old and had requested to be relieved from his command the previous May. He was also acutely aware of the 1842 Capture of Monterey

The Capture of Monterey by the United States Navy and Marine Corps occurred in 1842. After hearing false news that war had broken out between the United States and Mexico, the commander of the Pacific Squadron Thomas ap Catesby Jones sailed ...

, when his predecessor, Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore ...

Thomas ap Catesby Jones

Thomas ''ap'' Catesby Jones (24 April 1790 – 30 May 1858) was a U.S. Navy commissioned officer during the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War.

Early life and education

Thomas ap Catesby Jones was born on 24 April 1790 in Westm ...

, thought war had been declared and captured the capital of Alta California, only to discover his error and abandon it the next day. This resulted in diplomatic problems, and Jones was removed as commander of the Pacific Squadron.

Sloat had learned of Frémont's confrontation with the Californios on Gavilan Peak and of his support for the Bears in Sonoma. He was also aware of Lt. Gillespie's tracking down of Frémont with letters and orders. Sloat finally concluded on July 6 that he needed to act, saying to U.S. Consul Larkin, "I shall be blamed for doing too little or too much – I prefer the latter." Early July 7, the frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed an ...

USS ''Savannah'' and the two sloops

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular ...

, USS ''Cyane'' and USS ''Levant'' of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

, captured Monterey, California

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under b ...

, and raised the flag of the United States. Sloat had his proclamation read in and posted in English and Spanish: "...henceforth California will be a portion of the United States".

Conclusion and aftermath

Sausalito

Sausalito (Spanish for "small willow grove") is a city in Marin County, California, United States, located southeast of Marin City, south-southeast of San Rafael, and about north of San Francisco from the Golden Gate Bridge.

Sausalito's ...

, carrying two 27-star United States flags, one for Sonoma and the other for Sutter's Fort (the squadron had run out of new 28-star flags that reflected Texas' admittance to the Union

In electrical engineering, admittance is a measure of how easily a circuit or device will allow a current to flow. It is defined as the reciprocal of impedance, analogous to how conductance & resistance are defined. The SI unit of admittance ...

). The Bear Flag that was taken down that day was given to the Clerk of the ''Portsmouth'', John Elliott Montgomery, the son of Commander John B. Montgomery

John Berrien Montgomery (1794 – March 25, 1872) was an officer in the United States Navy who rose up through the ranks, serving in the War of 1812, Mexican–American War and the American Civil War, performing in various capacities including the ...

. John E. wrote to his mother later in July that "Cuffy came down growling". The following November, John and his older brother disappeared while traveling to Sacramento and were presumed deceased. Commander Montgomery kept the Bear Flag, had a copy made, and eventually both were delivered to the Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

. In 1855 the Secretary sent both flags to the Senators from California who donated them to the Society of Pioneers in San Francisco. The original Bear Flag was destroyed in the fires following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake

At 05:12 Pacific Standard Time on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, the coast of Northern California was struck by a major earthquake with an estimated moment magnitude of 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of XI (''Extreme''). High-intensity ...

. A replica, created in 1896 for the 50th Anniversary celebrations, is on display at the Sonoma Barracks

The Sonoma Barracks (Spanish: ''Cuartel de Sonoma'') is a two-story, wide-balconied, adobe building facing the central plaza of the City of Sonoma, California. It was built by order of Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo to house the Mexican soldiers that ...

.

Bear Flag

Flag of California

The Bear Flag is the official flag of the U.S. state of California. The precursor of the flag was first flown during the 1846 Bear Flag Revolt and was also known as the Bear Flag. A predecessor, called the Lone Star Flag, was used in an 1836 ...

. The flag has a star, a grizzly bear

The grizzly bear (''Ursus arctos horribilis''), also known as the North American brown bear or simply grizzly, is a population or subspecies of the brown bear inhabiting North America.

In addition to the mainland grizzly (''Ursus arctos horri ...

, and a red stripe with the words "California Republic". The ''Bear Flag Monument

''Bear Flag Monument'' (also known as ''Raising of the Bear Flag'') is a public artwork located at the Sonoma Plaza in Sonoma, California in the United States. A monument to the Bear Flag Revolt, the piece is listed as a California Historical Land ...

'' on the Sonoma Plaza

Sonoma Plaza (Spanish: ''Plaza de Sonoma'') is the central plaza of Sonoma, California. The plaza, the largest in California, was laid out in 1835 by Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, founder of Sonoma.

Description

This plaza is surrounded by many h ...

, site of the raising of the original Bear Flag, is marked by a California Historical Landmark

A California Historical Landmark (CHL) is a building, structure, site, or place in California that has been determined to have statewide historical landmark significance.

Criteria

Historical significance is determined by meeting at least one of ...

#7.

The design and creation of the original Bear Flag used in the Bear Flag Revolt is often credited to Peter Storm. The flags were made about one week before the storming of Sonoma, when William Todd and his companions claim to have made theirs, apparently based on Mr. Storm's first flags.

In 1878, at the request of the Los Angeles ''Evening Express'', William L. Todd (1818–1879) wrote an account of the Bear Flag used at the storming of Sonoma, perhaps the first to be raised. Soon after, his implementation became the basis for the first official State flag. Todd acknowledged the contributions of other ''Osos'' to the flag, including Granville P. Swift, Peter Storm, and Henry L. Ford in an 187newspaper article

Todd painted the flag on domestic cotton cloth, roughly a yard and a half in length. It featured a red star based on the California Lone Star Flag that was flown during California's 1836 revolt led by Juan Alvarado and

Isaac Graham

Isaac Graham (April 15, 1800 – November 8, 1863) was a fur trader, mountain man, and land grant owner in 19th century California.

In 1830, he joined a hunting and trapping party at Fort Smith, Arkansas that included George Nidever. Graham ...

. The flag also featured an image of a grizzly bear statant (standing), as opposed to the original flag, which showed it salient (leaping) or rampant

In heraldry, the term attitude describes the ''position'' in which a figure (animal or human) is emblazoned as a charge, a supporter, or as a crest. The attitude of an heraldic figure always precedes any reference to the tincture of the figure ...

(rearing up). The modern flag shows the bear passant (walking).

Timeline of events

See also

*Vermont Republic

The Vermont Republic (French: ''République du Vermont''), officially known at the time as the State of Vermont (French: ''État du Vermont''), was an independent state in New England that existed from January 15, 1777, to March 4, 1791. The s ...

* Republic of Lower California/Republic of Sonora, Mexico

* Rough and Ready, California

* Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas ( es, República de Tejas) was a sovereign state in North America that existed from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846, that bordered Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande in 1840 (another breakaway republic from Me ...

* State of Deseret

The State of Deseret (modern pronunciation , contemporaneously ) was a proposed state of the United States, proposed in 1849 by settlers from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) in Salt Lake City. The provisional stat ...

* Kingdom of Hawaii

The Hawaiian Kingdom, or Kingdom of Hawaiʻi ( Hawaiian: ''Ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina''), was a sovereign state located in the Hawaiian Islands. The country was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great, of the independent islan ...

/ Republic of Hawaii

The Republic of Hawaii ( Hawaiian: ''Lepupalika o Hawaii'') was a short-lived one-party state in Hawaii between July 4, 1894, when the Provisional Government of Hawaii had ended, and August 12, 1898, when it became annexed by the United State ...

* Green Mountain Boys

* Army of the Republic of Texas

The Texas Army, officially the Army of the Republic of Texas, was the land warfare branch of the Texas Military Forces during the Republic of Texas. It descended from the Texian Army, which was established in October 1835 to fight for independenc ...

* Texian Army

The Texian Army, also known as the Revolutionary Army and Army of the People, was the land warfare branch of the Texian armed forces during the Texas Revolution. It spontaneously formed from the Texian Militia in October 1835 following the Bat ...

* Texas Navy

The Texas Navy, officially the Navy of the Republic of Texas, also known as the Second Texas Navy, was the naval warfare branch of the Texas Military Forces during the Republic of Texas. It descended from the Texian Navy, which was established ...

* Nauvoo Legion

The Nauvoo Legion was a state-authorized militia of the city of Nauvoo, Illinois, United States. With growing antagonism from surrounding settlements it came to have as its main function the defense of Nauvoo, and surrounding Latter Day Saint ...

* California National Guard

The California National Guard is part of the National Guard of the United States, a dual federal-state military reserve force. The CA National Guard has three components: the CA Army National Guard, CA Air National Guard, and CA State Guard. ...

* New California Republic

''Fallout: New Vegas'' is a 2010 action role-playing game developed by Obsidian Entertainment and published by Bethesda Softworks. It was announced in April 2009 and released for Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 3, and Xbox 360 on October 19, 201 ...

* Benjamin Dewell, member of the Bear Flag Rebellion

Notes

References

Citations

* Also a''History of California, VOL. V. 1846–1848''

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

External links

( U.S. National Park Service) *

John Bidwell

John Bidwell (August 5, 1819 – April 4, 1900), known in Spanish as Don Juan Bidwell, was a Californian pioneer, politician, and soldier. Bidwell is known as the founder the city of Chico, California.

Born in New York, he emigrated at the age of ...

,Frémont in the Conquest of California

, ''The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine'', vol. XLI, no. 4, February 1891

The Bear Flag Museum

Modern representation of the flag as designed by William Todd.

{{Authority control * Rebellions in North America

California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

Former territorial entities in North America

Former regions and territories of the United States

Former republics

Former unrecognized countries

History of Sonoma County, California

People of the Bear Flag Revolt

Pre-statehood history of California

1846 establishments in Alta California

States and territories established in 1846

1846 disestablishments in Alta California

States and territories disestablished in 1846

Symbols of California

Separatism in Mexico

United States history timelines

History of the United States