COMARE on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A mistress is a woman who is in a relatively long-term sexual and romantic relationship with a man who is married to a different woman.

A mistress is a woman who is in a relatively long-term sexual and romantic relationship with a man who is married to a different woman.

The historically best known and most-researched mistresses are the

The historically best known and most-researched mistresses are the

In both John Cleland's 1748 novel '' Fanny Hill'' and

In both John Cleland's 1748 novel '' Fanny Hill'' and

A mistress is a woman who is in a relatively long-term sexual and romantic relationship with a man who is married to a different woman.

A mistress is a woman who is in a relatively long-term sexual and romantic relationship with a man who is married to a different woman.

Description

A mistress is in a long-term relationship with her attached mister, and is often referred to as "the other woman". Generally, the relationship is stable and at least semi-permanent, but the couple does not live together openly and the relationship is usually, but not always, secret. There is often also the implication that the mistress is sometimes "kept"i.e. her lover is contributing to her living expenses. A mistress is usually not considered aprostitute

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in Sex work, sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, n ...

: while a mistress, if "kept", may, in some sense, be exchanging sex for money, the principal difference is that a mistress has sex with fewer men and there is not so much of a direct ''quid pro quo

Quid pro quo ('what for what' in Latin) is a Latin phrase used in English to mean an exchange of goods or services, in which one transfer is contingent upon the other; "a favor for a favor". Phrases with similar meanings include: "give and take", ...

'' between the money and the sex act. There is usually an emotional and possibly social relationship between a man and his mistress, whereas the relationship between a prostitute and her client is predominantly monetary. It is also important that the "kept" status follows the establishment of a relationship of indefinite term as opposed to the agreement on price and terms established prior to any activity with a prostitute.

Historically the term has denoted a "kept woman", who was maintained in a comfortable (or even lavish) lifestyle by a wealthy man so that she would be available for his sexual pleasure (like a "sugar baby"). Such a woman could move between the roles of a mistress and a courtesan

Courtesan, in modern usage, is a euphemism for a "kept" mistress or prostitute, particularly one with wealthy, powerful, or influential clients. The term historically referred to a courtier, a person who attended the court of a monarch or othe ...

depending on her situation and environment.

In modern times, the word "mistress" is used primarily to refer to the female lover of a man who is married to another woman; in the case of an unmarried man, it is usual to speak of a " girlfriend" or " partner".

The term "mistress" was originally used as a neutral feminine counterpart to "mister" or "master".

History

The historically best known and most-researched mistresses are the

The historically best known and most-researched mistresses are the royal mistress

A royal mistress is the historical position and sometimes unofficial title of the extramarital lover of a monarch or an heir apparent, who was expected to provide certain services, such as sexual or romantic intimacy, companionship, and advic ...

es of European monarch

A monarch is a head of stateWebster's II New College DictionarMonarch Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest authority ...

s, for example, Agnès Sorel, Diane de Poitiers

Diane de Poitiers (9 January 1500 – 25 April 1566) was a French noblewoman and prominent courtier. She wielded much power and influence as King Henry II's royal mistress and adviser until his death. Her position increased her wealth and famil ...

, Barbara Villiers

Barbara Palmer, 1st Duchess of Cleveland, Countess of Castlemaine (née Barbara Villiers, – 9 October 1709), was an English royal mistress of the Villiers family and perhaps the most notorious of the many mistresses of King Charles II of En ...

, Nell Gwyn

Eleanor Gwyn (2 February 1650 – 14 November 1687; also spelled ''Gwynn'', ''Gwynne'') was a celebrity figure of the Restoration period. Praised by Samuel Pepys for her comic performances as one of the first actresses on the English stag ...

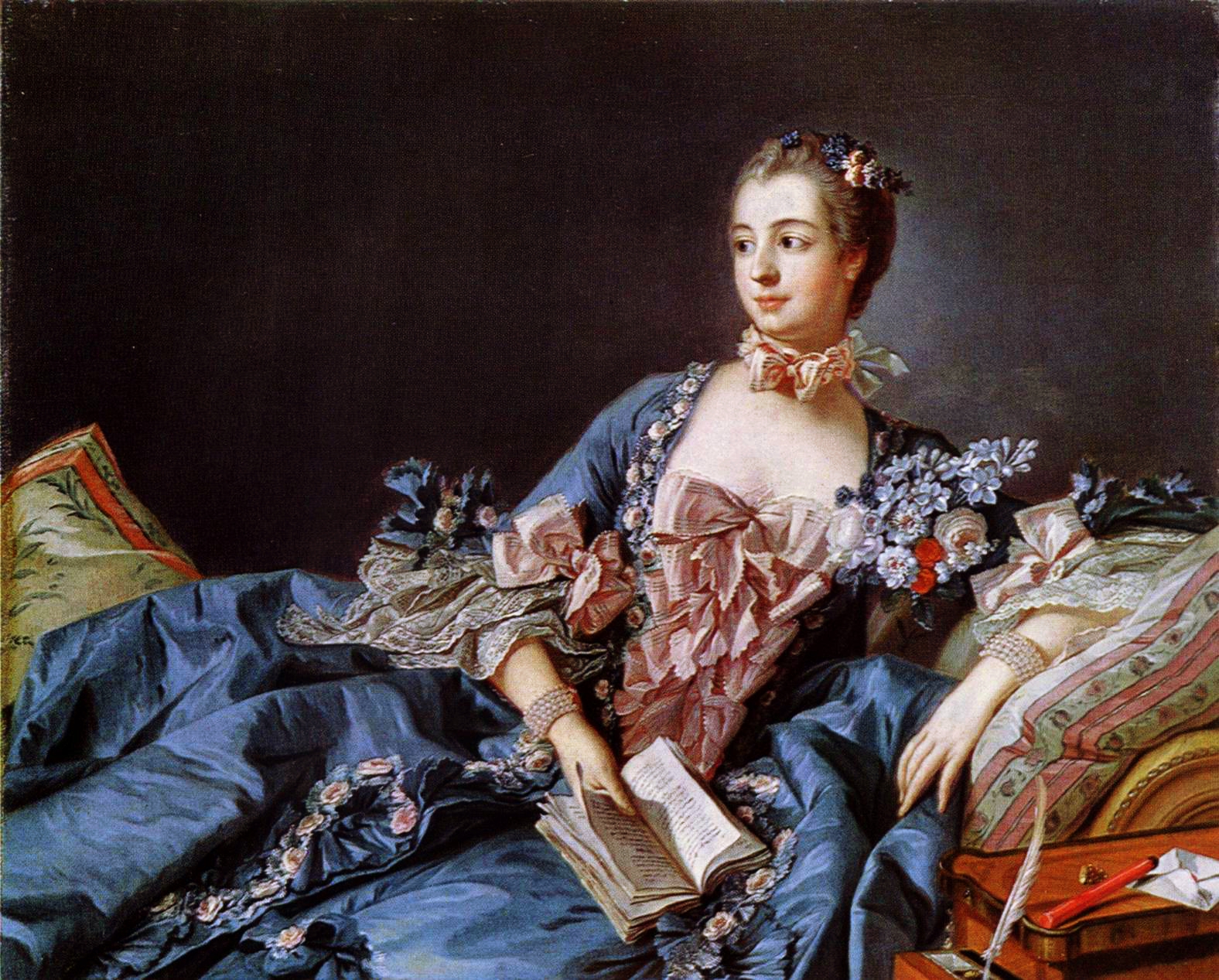

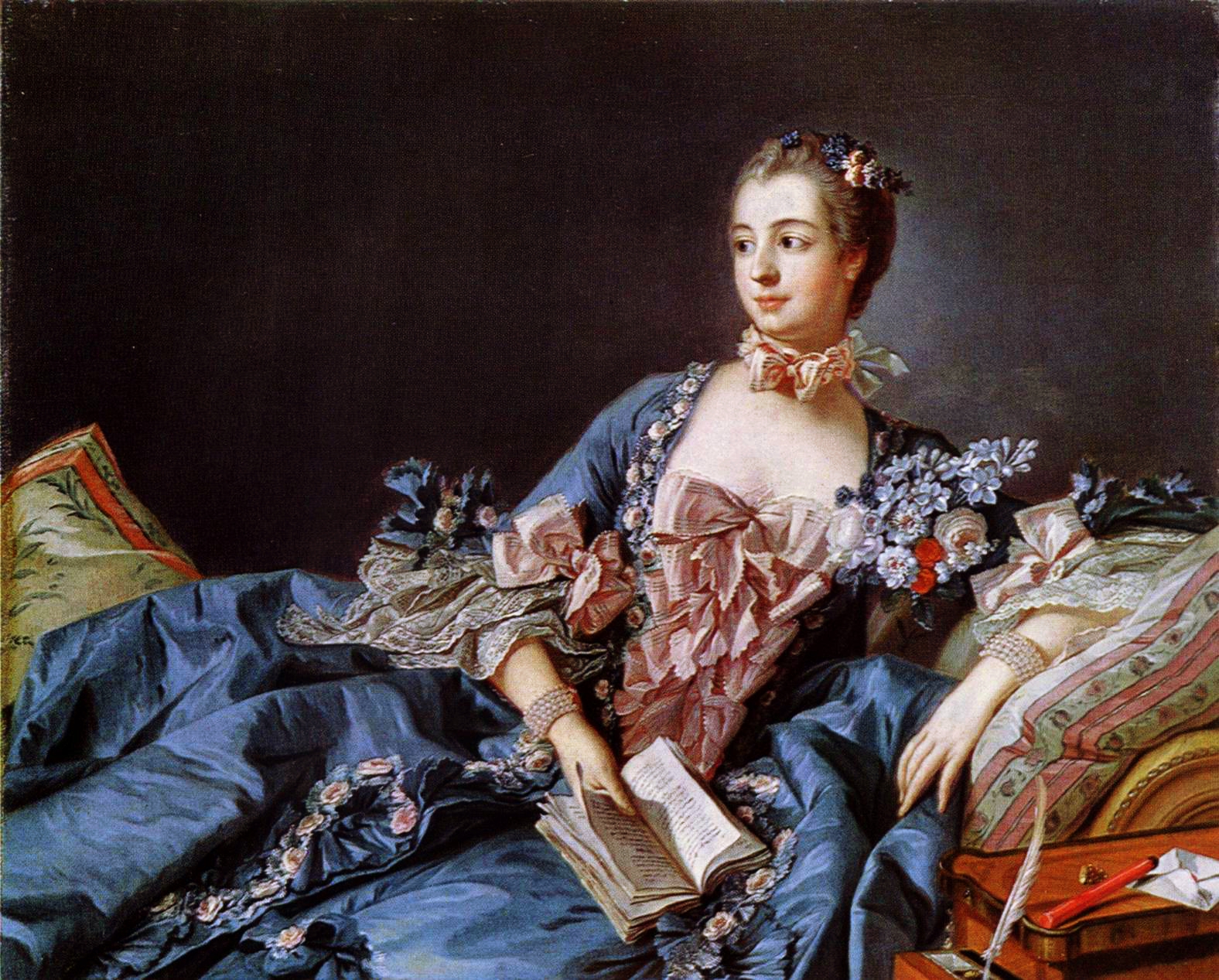

and Madame de Pompadour

Jeanne Antoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour (, ; 29 December 1721 – 15 April 1764), commonly known as Madame de Pompadour, was a member of the French court. She was the official chief mistress of King Louis XV from 1745 to 1751, and rem ...

. The keeping of a mistress in Europe was not confined to royalty and nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The character ...

, but permeated down through the social ranks, essentially to any man who could afford to do so. Any man who could afford a mistress could have one (or more), regardless of social position. A wealthy merchant

A merchant is a person who trades in commodities produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Historically, a merchant is anyone who is involved in business or trade. Merchants have operated for as long as indust ...

or a young noble might have had a kept woman. Being a mistress was typically an occupation for a younger woman who, if she were fortunate, might go on to marry her lover or another man of rank.

The ballad "The Three Ravens

"The Three Ravens" () is an English folk ballad, printed in the song book ''Melismata'' compiled by Thomas Ravenscroft and published in 1611, but it is perhaps older than that. Newer versions (with different music) were recorded right up through ...

" (published in 1611, but possibly older) extolls the loyal mistress of a slain knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

, who buries her dead lover and then dies of the exertion, as she was in an advanced stage of pregnancy. The ballad-maker assigned this role to the knight's mistress ("leman" was the term common at the time) rather than to his wife.

In the courts

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accorda ...

of Europe, particularly Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, ...

and Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea. It is the main thoroughfare running south from Trafalgar Square towards Parliament Sq ...

in the 17th and 18th centuries, a mistress often wielded great power and influence. A king might have numerous mistresses, but have a single "favourite mistress" or "official mistress" (in French, ''maîtresse en titre

''Maîtresse'' (French for "mistress" or "teacher") is a 1975 French sex comedy film co-written and directed by Barbet Schroeder, starring Bulle Ogier and, in one of his earliest leading roles, Gérard Depardieu. The film provoked controversy i ...

''), as with Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reache ...

and Madame de Pompadour

Jeanne Antoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour (, ; 29 December 1721 – 15 April 1764), commonly known as Madame de Pompadour, was a member of the French court. She was the official chief mistress of King Louis XV from 1745 to 1751, and rem ...

. The mistresses of both Louis XV (especially Madame de Pompadour) and Charles II were often considered to exert great influence over their lovers, the relationships being open secrets. Other than wealthy merchants and kings, Alexander VI

Pope Alexander VI ( it, Alessandro VI, va, Alexandre VI, es, Alejandro VI; born Rodrigo de Borja; ca-valencia, Roderic Llançol i de Borja ; es, Rodrigo Lanzol y de Borja, lang ; 1431 – 18 August 1503) was head of the Catholic Chur ...

is but one example of a Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

who kept mistresses. While the extremely wealthy might keep a mistress for life (as George II of Great Britain

George II (George Augustus; german: link=no, Georg August; 30 October / 9 November 1683 – 25 October 1760) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (Electorate of Hanover, Hanover) and a prince-ele ...

did with " Mrs Howard", even after they were no longer romantically linked), such was not the case for most kept women.

In 1736, when George II was newly ascendant, Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English novelist, irony writer, and dramatist known for earthy humour and satire. His comic novel ''Tom Jones'' is still widely appreciated. He and Samuel Richardson are seen as founders ...

(in ''Pasquin

Pasquino or Pasquin (Latin: ''Pasquillus'') is the name used by Romans since the early modern period to describe a battered Hellenistic-style statue perhaps dating to the third century BC, which was unearthed in the Parione district of Rome i ...

'') has his Lord Place say, " ..but, miss, every one now keeps and is kept; there are no such things as marriages now-a-days, unless merely Smithfield contracts, and that for the support of families; but then the husband and wife both take into keeping within a fortnight".

Occasionally the mistress is in a superior position both financially and socially to her lover. As a widow, Catherine the Great

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anha ...

was known to have been involved with several successive men during her reign; but, like many powerful women of her era, in spite of being a widow free to marry, she chose not to share her power with a husband, preferring to maintain absolute power alone.

In literature, D. H. Lawrence

David Herbert Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English writer, novelist, poet and essayist. His works reflect on modernity, industrialization, sexuality, emotional health, vitality, spontaneity and instinct. His best-k ...

's 1928 novel ''Lady Chatterley's Lover

''Lady Chatterley's Lover'' is the last novel by English author D. H. Lawrence, which was first published privately in 1928, in Italy, and in 1929, in France. An unexpurgated edition was not published openly in the United Kingdom until 1960, wh ...

'' portrays a situation where a woman becomes the mistress of her husband's gamekeeper. Until recently, a woman's taking a socially inferior lover was considered much more shocking than the reverse situation.

20th century

Asdivorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganizing of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving th ...

became more socially acceptable, it was easier for men to divorce their wives and marry the women who, in earlier years, might have been their mistresses. The practice of having a mistress continued among some married men, especially the wealthy. Occasionally, men married their mistresses. The late Sir James Goldsmith

Sir James Michael Goldsmith (26 February 1933 – 18 July 1997) was a French-British financier, tycoon''Billionaire: The Life and Times of Sir James Goldsmith'' by Ivan Fallon and politician who was a member of the Goldsmith family.

His cont ...

, on marrying his mistress, Lady Annabel Birley, declared, "When you marry your mistress, you create a job vacancy".

Male equivalent

" Paramour" is sometimes used, but this term can apply to either partner in an illicit relationship, so it is not exclusively male. If the man is being financially supported, especially by a wealthy older woman, he is a "sugar baby", "kept man" or "toyboy". In 18th and 19th-centuryItaly

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, the terms '' cicisbeo'' and ''cavalier servente'' were used to describe a man who was the professed gallant and lover of a married woman. Another word that has been used for a male mistress is ''gigolo

A gigolo () is a male escort or social companion who is supported by a person in a continuing relationship, often living in her residence or having to be present at her beck and call.

The term ''gigolo'' usually implies a man who adopts a lifes ...

'', though this carries connotations of brief duration and expectation of payment, i.e. prostitution

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in Sex work, sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, n ...

.

In literature

In both John Cleland's 1748 novel '' Fanny Hill'' and

In both John Cleland's 1748 novel '' Fanny Hill'' and Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, trader, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel '' Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its ...

's 1722 ''Moll Flanders

''Moll Flanders'' is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published in 1722. It purports to be the true account of the life of the eponymous Moll, detailing her exploits from birth until old age.

By 1721, Defoe had become a recognised novelist, wi ...

'', as well as in countless novels of feminine peril, the distinction between a "kept woman" and a prostitute is all-important.

Apologists for the practice of mistresses referred to the practice in the ancient Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

of keeping a concubine

Concubinage is an interpersonal and sexual relationship between a man and a woman in which the couple does not want, or cannot enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarded as similar but mutually exclusive.

Concubi ...

; they frequently quoted verses from the Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

to show that mistress-keeping was an ancient practice that was, if not acceptable, at least understandable. John Dryden

''

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the p ...

, in ''Annus Mirabilis

''Annus mirabilis'' (pl. ''anni mirabiles'') is a Latin phrase that means "marvelous year", "wonderful year", "miraculous year", or "amazing year". This term has been used to refer to several years during which events of major importance are re ...

'', suggested that the king's keeping of mistresses and production of bastards was a result of his abundance of generosity and spirit. In its more sinister form, the theme of being "kept" is never far from the surface in novels about women as victims in the 18th century in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, whether in the novels of Eliza Haywood

Eliza Haywood (c. 1693 – 25 February 1756), born Elizabeth Fowler, was an English writer, actress and publisher. An increase in interest and recognition of Haywood's literary works began in the 1980s. Described as "prolific even by the standar ...

or Samuel Richardson (whose heroines in '' Pamela'' and ''Clarissa

''Clarissa; or, The History of a Young Lady: Comprehending the Most Important Concerns of Private Life. And Particularly Shewing, the Distresses that May Attend the Misconduct Both of Parents and Children, In Relation to Marriage'' is an epist ...

'' are both put in a position of being threatened with sexual degradation and being reduced to the status of a kept object).

With the Romantics of the early 19th century, the subject of "keeping" becomes more problematic, in that a non-marital sexual union can occasionally be celebrated as a woman's free choice and a noble alternative. Mary Ann Evans (better known as George Eliot

Mary Ann Evans (22 November 1819 – 22 December 1880; alternatively Mary Anne or Marian), known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English novelist, poet, journalist, translator, and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. She wrot ...

) defiantly lived "in sin" with a married man, partially as a sign of her independence of middle-class morality. Her independence required that she not be "kept".

See also

*Alienation of affections

Alienation of affections is a common law tort, abolished in many jurisdictions. Where it still exists, an action is brought by a spouse against a third party alleged to be responsible for damaging the marriage, most often resulting in divorce. The ...

* '' Cicisbeo''

* Concubinage

Concubinage is an interpersonal and sexual relationship between a man and a woman in which the couple does not want, or cannot enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarded as similar but mutually exclusive.

Concubin ...

* English royal mistress

* French royal mistresses

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

* Polygyny threshold model

References

Citations

Sources

; Books * *Further reading

* * {{Authority control Heterosexuality Polygyny Female beauty