CIA Kennedy assassination conspiracy theory on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The CIA Kennedy assassination theory is a prominent John F. Kennedy assassination conspiracy theory. According to

pp. 65–75. The committee's conclusion of a conspiracy was based almost entirely on the results of a forensic analysis of a police dictabelt recording, which was later disputed.

, ''Playboy'' magazine, Eric Norden, October 1967. Garrison also came to believe that businessman

Gaeton Fonzi: Journalist who investigated the assassination of John F Kennedy

/ref>

The Independent, 23 October 2017. Through his research, Fonzi became convinced that Phillips had played a key role in the assassination of President Kennedy. Fonzi also concluded that, as part of the assassination plot, Phillips had actively worked to embellish Oswald's image as a communist sympathizer. He further concluded that the presence of a possible Oswald impersonator in Mexico City, during the period that Oswald himself was in Mexico City, may have been orchestrated by Phillips This evidence first surfaced in testimony given to the HSCA in 1978, and through the investigative work of independent journalist

Mexico City

/ref> Contreras described "Oswald" as "over thirty, light-haired and fairly short" — a description that did not fit the real Oswald To Fonzi, it seemed improbable that the real Oswald would at random start a conversation regarding his difficulties in obtaining a Cuban visa with Contreras, a man who belonged to a pro-Castro student group and had contacts in the Cuban embassy in Mexico City. Fonzi theorized that there was an Oswald impersonator in Mexico City, directed by Phillips, during the period that the Warren Commission concluded that Oswald himself had visited the city. Fonzi's belief was strengthened by statements from other witnesses. On September 27, 1963, and again a week later, a man identifying himself as Oswald visited the Cuban embassy in Mexico City. Consular Eusebio Azcue told Anthony Summers that the real Oswald "in no way resembled" the "Oswald" to whom he had spoken to at length. Embassy employee Sylvia Duran also told Summers that the real Oswald she eventually saw on film "is not like the man I saw here in Mexico City." On October 1, the CIA recorded two tapped telephone calls to the Soviet embassy by a man identified as Oswald. The CIA transcriber noted that "Oswald" spoke in "broken Russian". The real Oswald was quite fluent in Russian. On October 10, 1963, the CIA issued a teletype to the FBI, the State Department and the Navy, regarding Oswald's visits to Mexico City. The teletype was accompanied by a photo of a man identified as Oswald who in fact looked nothing like him. On November 23, 1963, the day after the assassination of President Kennedy, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover's preliminary analysis of the assassination included the following:

The "three tramps" are three men photographed by several Dallas-area newspapers under police escort near the Texas School Book Depository shortly after the assassination of President Kennedy. The men were detained and questioned briefly by the Dallas police. They have been the subject of various conspiracy theories, including some that allege the three men to be known CIA agents. Some of these allegations are listed below.

E. Howard Hunt is alleged by some to be the oldest of the tramps. Hunt was a CIA station chief in

The "three tramps" are three men photographed by several Dallas-area newspapers under police escort near the Texas School Book Depository shortly after the assassination of President Kennedy. The men were detained and questioned briefly by the Dallas police. They have been the subject of various conspiracy theories, including some that allege the three men to be known CIA agents. Some of these allegations are listed below.

E. Howard Hunt is alleged by some to be the oldest of the tramps. Hunt was a CIA station chief in

The House Select Committee on Assassinations had forensic anthropologists study the photographic evidence. The committee claimed that its analysis ruled out E. Howard Hunt, Frank Sturgis, Dan Carswell, Fred Lee Chapman, and other suspects. The Rockefeller Commission concluded that neither Hunt nor Frank Sturgis were in Dallas on the day of the assassination.

Records released by the

The House Select Committee on Assassinations had forensic anthropologists study the photographic evidence. The committee claimed that its analysis ruled out E. Howard Hunt, Frank Sturgis, Dan Carswell, Fred Lee Chapman, and other suspects. The Rockefeller Commission concluded that neither Hunt nor Frank Sturgis were in Dallas on the day of the assassination.

Records released by the

In an article published in the ''

In an article published in the ''

Warren Commission Report, Appendix XII, p. 660. New Orleans District Attorney (and later judge)

PBS ''Frontline'' "Who Was Lee Harvey Oswald"

Interview: G. Robert Blakey, November 19, 2013.

ABC News

ABC News is the news division of the American broadcast network ABC. Its flagship program is the daily evening newscast '' ABC World News Tonight with David Muir''; other programs include morning news-talk show '' Good Morning America'', '' ...

, the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA) is represented in nearly every theory that involves American conspirators. The secretive nature of the CIA, and the conjecture surrounding high-profile political assassinations in the United States during the 1960s, has made the CIA a plausible suspect for some who believe in a conspiracy. Conspiracy theorists have ascribed various motives for CIA involvement in the assassination of President Kennedy, including Kennedy's firing of CIA director Allen Dulles

Allen Welsh Dulles (, ; April 7, 1893 – January 29, 1969) was the first civilian Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), and its longest-serving director to date. As head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the early Cold War, he ov ...

, Kennedy's refusal to provide air support

In military tactics, close air support (CAS) is defined as air action such as air strikes by fixed or rotary-winged aircraft against hostile targets near friendly forces and require detailed integration of each air mission with fire and movemen ...

to the Bay of Pigs invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly fin ...

, Kennedy's plan to cut the agency's budget by 20 percent, and the belief that the president was weak on communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

.

In 1979, the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) concluded that the CIA was not involved in the assassination of Kennedy.

Background

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

, the 35th President of the United States, was assassinated in Dallas

Dallas () is the third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 million people. It is the largest city in and seat of Dallas County ...

, Texas, on November 22, 1963. In the aftermath, several government agencies and panels investigated the circumstances surrounding the assassination, and all concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald

Lee Harvey Oswald (October 18, 1939 – November 24, 1963) was a U.S. Marine veteran who assassinated John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, on November 22, 1963.

Oswald was placed in juvenile detention at the age of 12 fo ...

was the assassin. However, Oswald was murdered by Mafia-associated nightclub

A nightclub (music club, discothèque, disco club, or simply club) is an entertainment venue during nighttime comprising a dance floor, lightshow, and a stage for live music or a disc jockey (DJ) who plays recorded music.

Nightclubs gen ...

owner Jack Ruby

Jack Leon Ruby (born Jacob Leon Rubenstein; April 25, 1911January 3, 1967) was an American nightclub owner and alleged associate of the Chicago Outfit who murdered Lee Harvey Oswald on November 24, 1963, two days after Oswald was accused of ...

before he could be tried in a court of law. The discrepancies between the official investigations and the extraordinary nature of the assassination have led to a variety of theories about how and why Kennedy was assassinated, as well as the possibility of a conspiracy.

In 1979, the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) concluded that Oswald assassinated Kennedy, but that a second gunman besides Oswald probably also fired at Kennedy, and that a conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, is a secret plan or agreement between persons (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder or treason, especially with political motivation, while keeping their agr ...

was probable.House Select Committee on Assassinations Final Reportpp. 65–75. The committee's conclusion of a conspiracy was based almost entirely on the results of a forensic analysis of a police dictabelt recording, which was later disputed.

Origin

In 1966, New OrleansDistrict Attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or state attorney is the chief prosecutor and/or chief law enforcement officer representing a U.S. state in a ...

Jim Garrison

James Carothers Garrison (born Earling Carothers Garrison; November 20, 1921 – October 21, 1992) was the District Attorney of Orleans Parish, Louisiana, from 1962 to 1973. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best known for his investigat ...

began an investigation into the assassination of President Kennedy. Garrison's investigation led him to conclude that a group of right-wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that view certain social orders and Social stratification, hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this pos ...

extremists were involved with elements of the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA) in a conspiracy to kill Kennedy.Jim Garrison Interview, ''Playboy'' magazine, Eric Norden, October 1967. Garrison also came to believe that businessman

Clay Shaw

Clay LaVergne Shaw (March 17, 1913 – August 15, 1974) was an American businessman and military officer from New Orleans, Louisiana. Shaw is best known for being the only person brought to trial for involvement in the assassination of John F. ...

, head of the International Trade Mart

The International Trade Mart was a New Orleans-based organization promoting international trade and the Port of New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. The organization was founded in 1946, and merged with International House in 1968, when it was r ...

in , was part of the conspiracy. On March 1, 1967, Garrison arrested and charged Shaw with conspiring to assassinate President Kennedy.

Three days after Shaw's arrest, the Italian left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

newspaper ''Paese Sera'' published an article alleging that Shaw was linked to the CIA through his involvement in the Centro Mondiale Commerciale, a subsidiary

A subsidiary, subsidiary company or daughter company is a company owned or controlled by another company, which is called the parent company or holding company. Two or more subsidiaries that either belong to the same parent company or having a ...

of the trade organization Permindex in which Shaw was a board member. According to ''Paese Sera'', the CMC had been a front organization

A front organization is any entity set up by and controlled by another organization, such as intelligence agencies, organized crime groups, terrorist organizations, secret societies, banned organizations, religious or political groups, advocacy ...

developed by the CIA for transferring funds to Italy for "illegal political-espionage activities." ''Paese Sera'' also reported that the CMC had attempted to depose French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

President Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

in the early 1960s. The newspaper printed other allegations about individuals it said were connected to Permindex, including Louis Bloomfield whom it described as "an American agent who now plays the role of a businessman from Canada hoestablished secret ties in Rome with Deputies of the Christian Democrats and neo-Fascist parties." The allegations were reprinted in various newspapers associated with the Communist parties

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

in Italy (''l'Unità

''l'Unità'' (, lit. 'the Unity') was an Italian newspaper, founded as the official newspaper of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) in 1924. It was supportive of that party's successor parties, the Democratic Party of the Left, Democrats of th ...

''), France (''L'Humanité

''L'Humanité'' (; ), is a French daily newspaper. It was previously an organ of the French Communist Party, and maintains links to the party. Its slogan is "In an ideal world, ''L'Humanité'' would not exist."

History and profile

Pre-World Wa ...

''), and the Soviet Union (''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, "Truth") is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the ...

''), as well as leftist newspapers in Canada and Greece, prior to reaching the American press eight weeks later. American journalist Max Holland

__notoc__

Max Holland (born 1950, Providence, Rhode Island) is an American journalist, author, and the editor of '' Washington Decoded'', an internet newsletter on US history that began publishing March 11, 2007. He is currently a contributing edi ...

wrote that the KGB planted the original story in ''Paese Sera'', citing archives released by Vasili Mitrokhin

Vasili Nikitich Mitrokhin (russian: link=no, Васи́лий Ники́тич Митро́хин; March 3, 1922 – January 23, 2004) was a major and senior archivist for the Soviet Union's foreign intelligence service, the First Chief Di ...

, thereby influencing both Garrison's subsequent accusations against the CIA and Oliver Stone

William Oliver Stone (born September 15, 1946) is an American film director, producer, and screenwriter. Stone won an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay as writer of '' Midnight Express'' (1978), and wrote the gangster film remake '' Sc ...

's 1991 film '' JFK''.

On January 29, 1969, Clay Shaw was brought to trial on charges of being part of a conspiracy to assassinate Kennedy, and the jury found him not guilty.

Proponents and believers

Jim Garrison alleged that anti-Communist and anti-Castro extremists in the CIA plotted the assassination of Kennedy to maintain tension with the Soviet Union and Cuba, and to prevent a United States withdrawal from Vietnam. James Douglass wrote in '' JFK and the Unspeakable'' that the CIA, acting upon the orders of conspirators with the "military industrial complex

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

", killed Kennedy and in the process set up Lee Harvey Oswald as a patsy. Like Garrison, Douglass stated that Kennedy was killed because he was turning away from the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

and pursuing paths of nuclear disarmament

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

* Nuclea ...

, rapprochement

In international relations, a rapprochement, which comes from the French word ''rapprocher'' ("to bring together"), is a re-establishment of cordial relations between two countries. This may be done due to a mutual enemy, as was the case with Germ ...

with Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 20 ...

, and withdrawal from the war in Vietnam. Mark Lane — author of '' Rush to Judgment'' and ''Plausible Denial

''Plausible Denial: Was the CIA Involved in the Assassination of JFK?'' is a 1991 book by American attorney, Mark Lane that outlines his theory that former Watergate figure E. Howard Hunt was involved with the Central Intelligence Agency in the ...

'' and the attorney who defended Liberty Lobby

Liberty Lobby was a far-right think tank and lobby group founded in 1958 by Willis Carto. Carto was known for his promotion of antisemitic conspiracy theories, white nationalism, and Holocaust denial.

The organization produced a daily five-mi ...

against a defamation suit brought by former CIA agent E. Howard Hunt — has been described as a leading proponent of the theory that the CIA was responsible for the assassination of Kennedy. Others who believe the CIA was involved include authors Anthony Summers

Anthony Bruce Summers (born 21 December 1942) is an Irish author. He is a Pulitzer Prize Finalist and has written ten non-fiction books.

Career

Summers is an Irish citizen who has been working with Robbyn Swan for more than thirty years befo ...

and John M. Newman.

In 1977, the FBI released 40,000 files pertaining to the assassination of Kennedy, including an April 3, 1967 memorandum from Deputy Director Cartha DeLoach

Cartha Dekle DeLoach (July 20, 1920 – March 13, 2013), known as Deke DeLoach, was deputy associate director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) of the United States. During his post, DeLoach was the third most senior official in t ...

to Associate Director Clyde Tolson

Clyde Anderson Tolson (May 22, 1900 – April 14, 1975) was the second-ranking official of the FBI from 1930 until 1972, from 1947 titled Associate Director, primarily responsible for personnel and discipline. He was the ''protégé'', long-ti ...

that was written less than a month after President Johnson learned from J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation ...

about CIA plots to kill Fidel Castro. According to DeLoach, LBJ aide Marvin Watson "stated that the President had told him, in an off moment, that he was now convinced there was a plot in connection with the assassination f President Kennedy Watson stated the President felt that heCIA had had something to do with this plot." When questioned in 1975, during the Church Committee

The Church Committee (formally the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities) was a US Senate select committee in 1975 that investigated abuses by the Central Intelligence ...

hearings, DeLoach told Senator Richard Schweiker

Richard Schultz Schweiker (June 1, 1926 – July 31, 2015) was an American businessman and politician. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 14th U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services under President Ronald Reagan from 198 ...

that he "felt hat Watson's statement wassheer speculation."

Conspirators and evidence

Oswald impersonator in Mexico City conspiracy theory

Gaeton Fonzi was hired as a researcher in 1975 by the Church Committee and by the House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) in 1977. At the HSCA, Fonzi focused on the anti-Castro Cuban exile groups, and the links that these groups had with the CIA and the Mafia. Fonzi obtained testimony from Cuban exileAntonio Veciana

Antonio Veciana Blanch (October 18, 1928 – June 18, 2020) was a Cuban exile who became the founder and a leader of the anti-Castro group Alpha 66.

In the mid-1970s, Veciana told the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) ...

that Veciana had once witnessed his CIA contact, who Fonzi would later come to believe was David Atlee Phillips, conferring with Lee Harvey Oswald.Michael Carlson, ''The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publish ...

'', September 17, 2012Gaeton Fonzi: Journalist who investigated the assassination of John F Kennedy

/ref>

The Independent, 23 October 2017. Through his research, Fonzi became convinced that Phillips had played a key role in the assassination of President Kennedy. Fonzi also concluded that, as part of the assassination plot, Phillips had actively worked to embellish Oswald's image as a communist sympathizer. He further concluded that the presence of a possible Oswald impersonator in Mexico City, during the period that Oswald himself was in Mexico City, may have been orchestrated by Phillips This evidence first surfaced in testimony given to the HSCA in 1978, and through the investigative work of independent journalist

Anthony Summers

Anthony Bruce Summers (born 21 December 1942) is an Irish author. He is a Pulitzer Prize Finalist and has written ten non-fiction books.

Career

Summers is an Irish citizen who has been working with Robbyn Swan for more than thirty years befo ...

in 1979. Summers spoke with a man named Oscar Contreras, a law student at National University

A national university is mainly a university created or managed by a government, but which may also at the same time operate autonomously without direct control by the state.

Some national universities are associated with national cultural or po ...

in Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

, who said that someone calling himself Lee Harvey Oswald struck up a conversation with him inside a university cafeteria, in the fall of 1963. (The Warren Commission concluded that Oswald had taken a bus trip from Houston

Houston (; ) is the most populous city in Texas, the most populous city in the Southern United States, the fourth-most populous city in the United States, and the sixth-most populous city in North America, with a population of 2,304,580 ...

to Mexico City and back during September–October 1963.)Warren Commission Report, Appendix 13, pp. 732-735Mexico City

/ref> Contreras described "Oswald" as "over thirty, light-haired and fairly short" — a description that did not fit the real Oswald To Fonzi, it seemed improbable that the real Oswald would at random start a conversation regarding his difficulties in obtaining a Cuban visa with Contreras, a man who belonged to a pro-Castro student group and had contacts in the Cuban embassy in Mexico City. Fonzi theorized that there was an Oswald impersonator in Mexico City, directed by Phillips, during the period that the Warren Commission concluded that Oswald himself had visited the city. Fonzi's belief was strengthened by statements from other witnesses. On September 27, 1963, and again a week later, a man identifying himself as Oswald visited the Cuban embassy in Mexico City. Consular Eusebio Azcue told Anthony Summers that the real Oswald "in no way resembled" the "Oswald" to whom he had spoken to at length. Embassy employee Sylvia Duran also told Summers that the real Oswald she eventually saw on film "is not like the man I saw here in Mexico City." On October 1, the CIA recorded two tapped telephone calls to the Soviet embassy by a man identified as Oswald. The CIA transcriber noted that "Oswald" spoke in "broken Russian". The real Oswald was quite fluent in Russian. On October 10, 1963, the CIA issued a teletype to the FBI, the State Department and the Navy, regarding Oswald's visits to Mexico City. The teletype was accompanied by a photo of a man identified as Oswald who in fact looked nothing like him. On November 23, 1963, the day after the assassination of President Kennedy, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover's preliminary analysis of the assassination included the following:

The Central Intelligence Agency advised that on October 1st, 1963, an extremely sensitive source had reported that an individual identifying himself as Lee Oswald contacted the Soviet Embassy in Mexico City inquiring as to any messages. Special agents of this Bureau, who have conversed with Oswald in Dallas, Texas, have observed photographs of the individual referred to above and have listened to a recording of his voice. These special agents are of the opinion that the referred-to individual was not Lee Harvey Oswald.That same day, Hoover had this conversation with the new president, Lyndon Johnson: Fonzi concluded it was unlikely that the CIA would legitimately not be able to produce a single photograph of the real Oswald as part of the documentation of his trip to Mexico City, given that Oswald had made five separate visits to the Soviet and Cuban embassies (according to the Warren Commission) where the CIA maintained surveillance cameras.

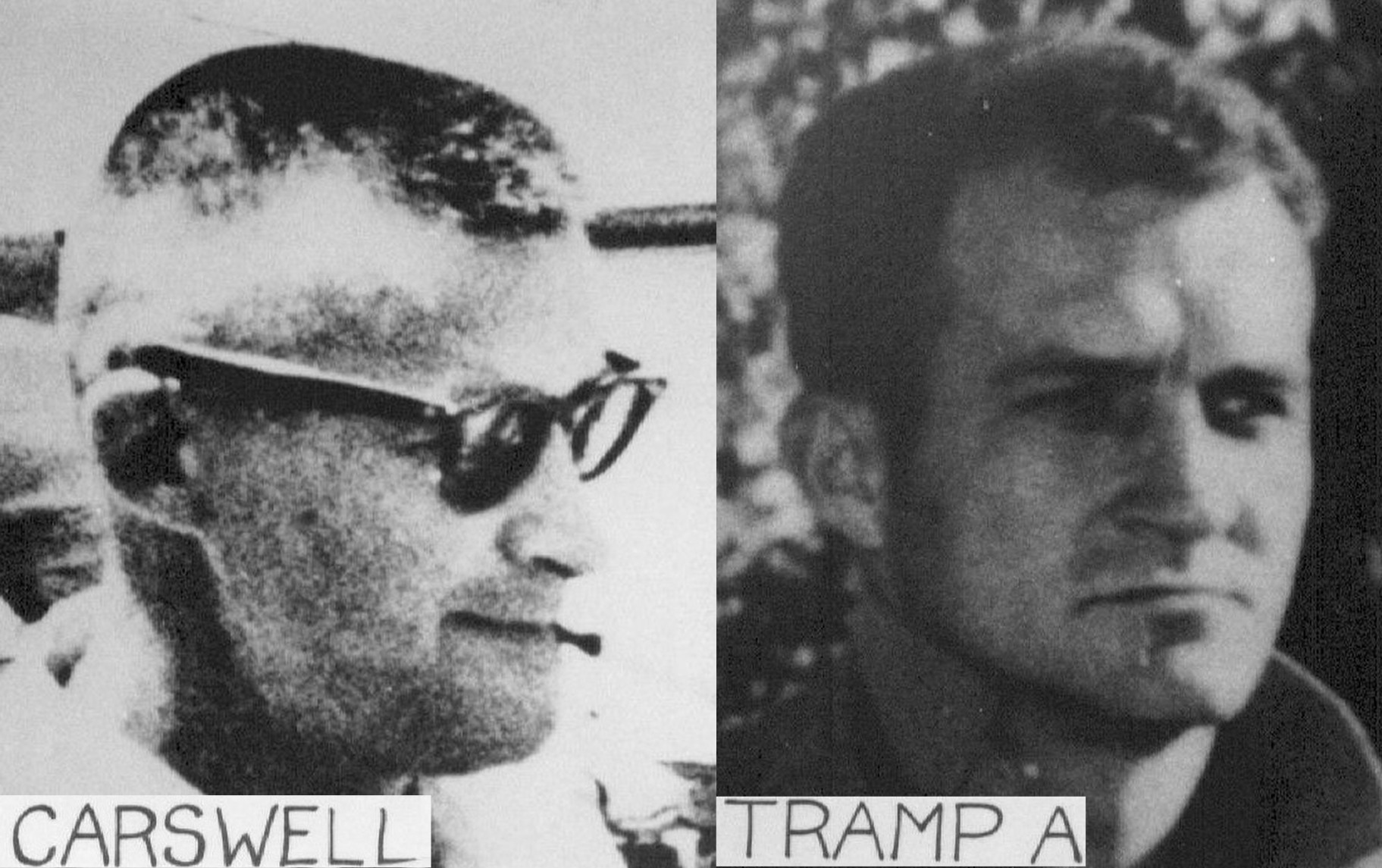

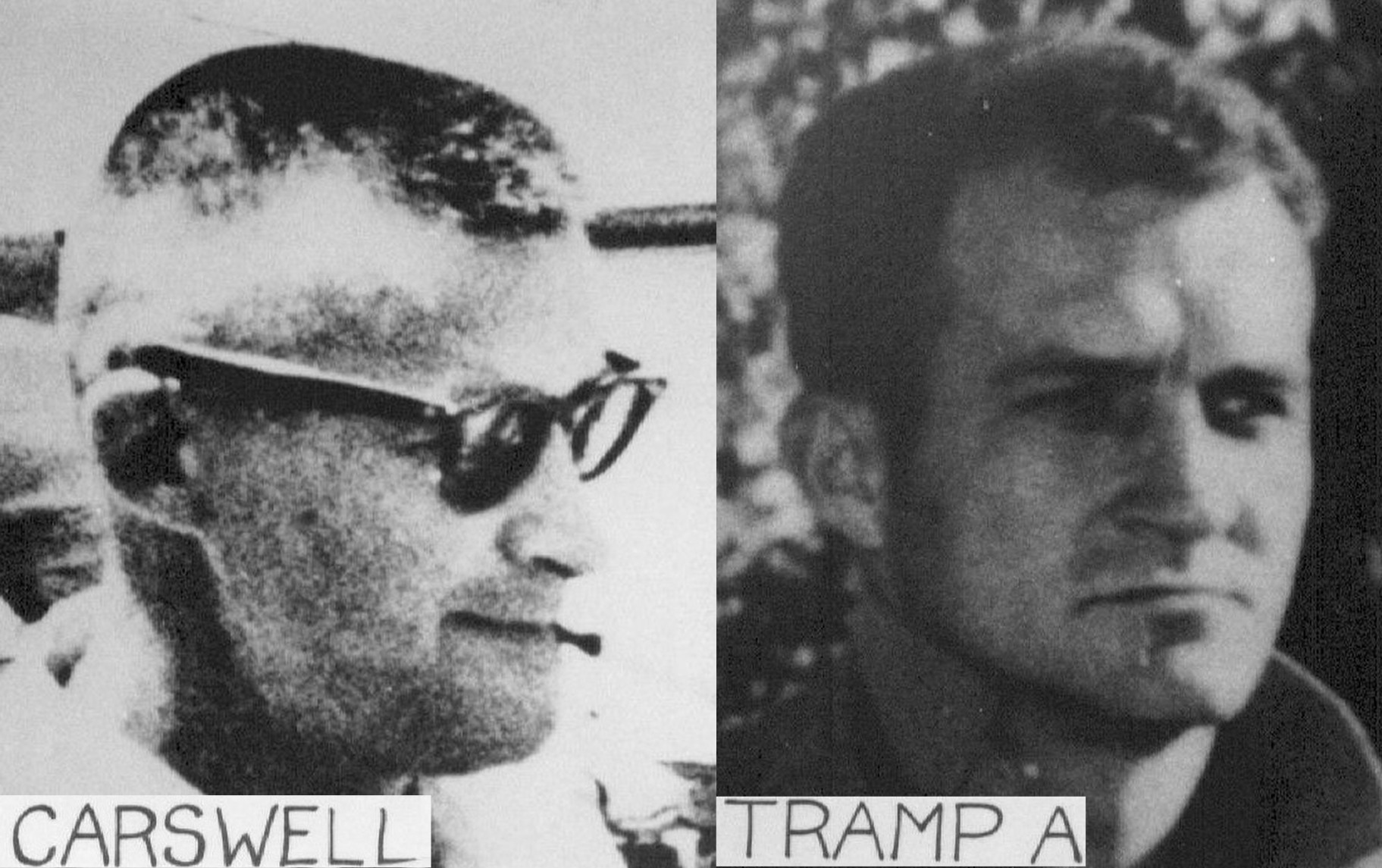

Three tramps

The "three tramps" are three men photographed by several Dallas-area newspapers under police escort near the Texas School Book Depository shortly after the assassination of President Kennedy. The men were detained and questioned briefly by the Dallas police. They have been the subject of various conspiracy theories, including some that allege the three men to be known CIA agents. Some of these allegations are listed below.

E. Howard Hunt is alleged by some to be the oldest of the tramps. Hunt was a CIA station chief in

The "three tramps" are three men photographed by several Dallas-area newspapers under police escort near the Texas School Book Depository shortly after the assassination of President Kennedy. The men were detained and questioned briefly by the Dallas police. They have been the subject of various conspiracy theories, including some that allege the three men to be known CIA agents. Some of these allegations are listed below.

E. Howard Hunt is alleged by some to be the oldest of the tramps. Hunt was a CIA station chief in Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

and was involved in the Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly fin ...

. Hunt later worked as one of President Richard Nixon's White House Plumbers

The White House Plumbers, sometimes simply called the Plumbers, the Room 16 Project, or more officially, the White House Special Investigations Unit, was a covert White House Special Investigations Unit, established within a week after the public ...

. Others believe that the oldest tramp is Chauncey Holt Chauncey Marvin Holt (October 23, 1921 – June 28, 1997) was an American known for claiming to be one of the "three tramps" photographed in Dealey Plaza shortly after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Background

Holt was born in Ken ...

. Holt claimed to have been a double agent for the CIA and the Mafia

"Mafia" is an informal term that is used to describe criminal organizations that bear a strong similarity to the original “Mafia”, the Sicilian Mafia and Italian Mafia. The central activity of such an organization would be the arbitration of d ...

, and claimed that his assignment in Dallas was to provide fake Secret Service credentials to people in the vicinity. Witness reports state that there were one or more unidentified men in the area claiming to be Secret Service agents. Both Dallas police officer Joe Smith and Army veteran Gordon Arnold have claimed to have met a man on or near the grassy knoll who showed them credentials identifying him as a Secret Service agent.

Frank Sturgis

Frank Anthony Sturgis (December 9, 1924 – December 4, 1993), born Frank Angelo Fiorini, was one of the five Watergate scandal, Watergate burglars whose capture led to the end of the presidency of Richard Nixon. He served in several branche ...

is thought by some to be the tall tramp. Like E. Howard Hunt, Sturgis was involved both in the Bay of Pigs invasion and in the Watergate burglary. In 1959, Sturgis became involved with Marita Lorenz

Ilona Marita Lorenz (18 August 1939 – 31 August 2019) was a German woman who had an affair with Fidel Castro in 1959 and in January 1960 was involved in an assassination attempt by the CIA on Castro's life.

In the 1970s and 1980s, she testifi ...

. Lorenz would later claim that Sturgis told her that he had participated in a JFK assassination plot. In response to her allegations, Sturgis denied being involved in a conspiracy to kill Kennedy. In an interview with Steve Dunleavy

Stephen Francis Patrick Aloysius Dunleavy (21 January 1938 – 24 June 2019) was an Australian journalist based in the United States, best known as a columnist for the ''New York Post'' from 1976 to 2008. He was a lead reporter on the US tabloid ...

of the ''New York Post

The ''New York Post'' (''NY Post'') is a conservative daily tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The ''Post'' also operates NYPost.com, the celebrity gossip site PageSix.com, and the entertainment site Decider.com.

It was established ...

'', Sturgis said that he believed communist agents had pressured Lorenz into making the accusations against him.

The House Select Committee on Assassinations had forensic anthropologists study the photographic evidence. The committee claimed that its analysis ruled out E. Howard Hunt, Frank Sturgis, Dan Carswell, Fred Lee Chapman, and other suspects. The Rockefeller Commission concluded that neither Hunt nor Frank Sturgis were in Dallas on the day of the assassination.

Records released by the

The House Select Committee on Assassinations had forensic anthropologists study the photographic evidence. The committee claimed that its analysis ruled out E. Howard Hunt, Frank Sturgis, Dan Carswell, Fred Lee Chapman, and other suspects. The Rockefeller Commission concluded that neither Hunt nor Frank Sturgis were in Dallas on the day of the assassination.

Records released by the Dallas Police Department

The Dallas Police Department, established in 1881, is the principal law enforcement agency serving the city of Dallas, Texas.

Organization

The department is headed by a chief of police who is appointed by the city manager who, in turn, is hir ...

in 1989 identified the three men as Gus Abrams, Harold Doyle, and John Gedney.

E. Howard Hunt

Several conspiracy theorists have named former CIA agent and Watergate figure E. Howard Hunt as a possible participant in the Kennedy assassination and some, as noted before, have alleged that Hunt is one of the three tramps. Hunt has taken various magazines to court over accusations with regard to the assassination. In 1975, Hunt testified before theUnited States President's Commission on CIA Activities within the United States #REDIRECT United States President's Commission on CIA Activities within the United States

{{R from move ...

that he was in Washington, D.C., on the day of the assassination. This testimony was confirmed by Hunt's family and a home employee of the Hunts.

In 1976, a magazine called ''The Spotlight'' ran an article accusing Hunt of being in Dallas on November 22, 1963, and of having a role in the assassination. Hunt won a libel judgment against the magazine in 1981, but this verdict was overturned on appeal. The magazine was found not liable when the case was retried in 1985. In 1985, Hunt was in court again in a libel suit against ''Liberty Lobby''. During the trial, defense attorney Mark Lane was successful in creating doubt among the jury as to Hunt's location on the day of the Kennedy assassination through depositions from David Atlee Phillips, Richard Helms

Richard McGarrah Helms (March 30, 1913 – October 23, 2002) was an American government official and diplomat who served as Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) from 1966 to 1973. Helms began intelligence work with the Office of Strategic Ser ...

, G. Gordon Liddy, Stansfield Turner

Stansfield Turner (December 1, 1923 January 18, 2018) was an admiral in the United States Navy who served as President of the Naval War College (1972–1974), commander of the United States Second Fleet (1974–1975), Supreme Allied Commander N ...

, and Marita Lorenz

Ilona Marita Lorenz (18 August 1939 – 31 August 2019) was a German woman who had an affair with Fidel Castro in 1959 and in January 1960 was involved in an assassination attempt by the CIA on Castro's life.

In the 1970s and 1980s, she testifi ...

, as well as through his cross examination of Hunt.

In August 2003, while in failing health, Hunt allegedly confessed to his son of his knowledge of a conspiracy in the JFK assassination. However, Hunt's health improved and he went on to live four more years. Shortly before Hunt's death in 2007, he authored an autobiography which implicated Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

in the assassination, suggesting that Johnson had orchestrated the killing with the help of CIA agents who had been angered by Kennedy's actions as president. After Hunt's death, his sons, Saint John Hunt and David Hunt, stated that their father had recorded several claims about himself and others being involved in a conspiracy to assassinate President Kennedy. In the April 5, 2007 issue of ''Rolling Stone

''Rolling Stone'' is an American monthly magazine that focuses on music, politics, and popular culture. It was founded in San Francisco, California, in 1967 by Jann Wenner, and the music critic Ralph J. Gleason. It was first known for its ...

'', Saint John Hunt detailed a number of individuals purported to be implicated by his father, including Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

, Cord Meyer

Cord Meyer Jr. (; November 10, 1920 – March 13, 2001) was a US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) official. After serving in World War II as a Marine officer in the Pacific War, where he was both injured and decorated, he led the United World Fe ...

, David Phillips, Frank Sturgis, David Morales

David Morales (; born August 21, 1962) is an American disc jockey (DJ) and record producer. In addition to his production and DJ work, Morales is also a remixer.

David Morales has remixed and produced over 500 releases for artists including ...

, Antonio Veciana

Antonio Veciana Blanch (October 18, 1928 – June 18, 2020) was a Cuban exile who became the founder and a leader of the anti-Castro group Alpha 66.

In the mid-1970s, Veciana told the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) ...

, William Harvey

William Harvey (1 April 1578 – 3 June 1657) was an English physician who made influential contributions in anatomy and physiology. He was the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, the systemic circulation and propert ...

, and an assassin he termed "French gunman grassy knoll" who some presume was Lucien Sarti. The two sons alleged that their father cut the information from his memoirs to avoid possible perjury charges. According to Hunt's widow and other children, the two sons took advantage of Hunt's loss of lucidity by coaching and exploiting him for financial gain. The ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the ...

'' said they examined the materials offered by the sons to support the story and found them to be "inconclusive".

David Sánchez Morales

Some researchers—among them Gaeton Fonzi, Larry Hancock, Noel Twyman, and John Simkin—believe that CIA operativeDavid Morales

David Morales (; born August 21, 1962) is an American disc jockey (DJ) and record producer. In addition to his production and DJ work, Morales is also a remixer.

David Morales has remixed and produced over 500 releases for artists including ...

was involved in the Kennedy assassination. Morales' friend, Ruben Carbajal, claimed that in 1973 Morales opened up about his involvement with the Bay of Pigs Invasion operation, and stated that "Kennedy had been responsible for him having to watch all the men he recruited and trained get wiped out." Carbajal claimed that Morales said, "Well, we took care of that SOB, didn't we?" Morales is alleged to have once told friends, "I was in Dallas when we got the son of a bitch, and I was in Los Angeles when we got the little bastard", presumably referring to the assassination of President Kennedy in Dallas, Texas

Dallas () is the third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 million people. It is the largest city in and seat of Dallas County ...

, and to the later assassination of Senator Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, ...

in Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

, on June 5, 1968. Morales is alleged to have expressed deep anger toward the Kennedys for what he saw as their betrayal during the Bay of Pigs Invasion.

Frank Sturgis

In an article published in the ''

In an article published in the ''South Florida Sun Sentinel

The ''Sun Sentinel'' (also known as the ''South Florida Sun Sentinel'', known until 2008 as the ''Sun-Sentinel'', and stylized on its masthead as ''SunSentinel'') is the main daily newspaper of Fort Lauderdale, Florida, as well as surrounding B ...

'' on December 4, 1963, James Buchanan, a former reporter for the Sun-Sentinel, claimed that Frank Sturgis had met Lee Harvey Oswald in Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a coastal metropolis and the county seat of Miami-Dade County in South Florida, United States. With a population of 442,241 at ...

, Florida, shortly before Kennedy's assassination. Buchanan claimed that Oswald had tried to infiltrate the International Anti-Communist Brigade. When he was questioned by the FBI about this story, Sturgis claimed that Buchanan had misquoted him regarding his comments about Oswald.

According to a memo sent by L. Patrick Gray

Louis Patrick Gray III (July 18, 1916 – July 6, 2005) was Acting Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from May 3, 1972 to April 27, 1973. During this time, the FBI was in charge of the initial investigation into the burglarie ...

, acting FBI Director

The Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation is the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, a United States' federal law enforcement agency, and is responsible for its day-to-day operations. The FBI Director is appointed for a single ...

, to H. R. Haldeman

Harry Robbins Haldeman (October 27, 1926 – November 12, 1993) was an American political aide and businessman, best known for his service as White House Chief of Staff to President Richard Nixon and his consequent involvement in the Watergate s ...

on June 19, 1972, " urces in Miami say he turgisis now associated with organized crime activities". In his book, ''Assassination of JFK'', published in 1977, Bernard Fensterwald

Bernard "Bud" Fensterwald Jr. (August 2, 1921 – April 2, 1991) was an American lawyer who defended James Earl Ray and James W. McCord Jr. Other notable clients included Mitch WerBell,Hougan, Jim. ''Secret Agenda''. p. 246. 1984. New York: Bal ...

claims that Sturgis was heavily involved with the Mafia, particularly with Santo Trafficante's and Meyer Lansky

Meyer Lansky (born Maier Suchowljansky; July 4, 1902 – January 15, 1983), known as the "Mob's Accountant", was an American organized crime figure who, along with his associate Charles "Lucky" Luciano, was instrumental in the development of the ...

's activities in Florida.

George de Mohrenschildt

After returning from the Soviet Union, Lee Harvey Oswald became friends with Dallas resident andpetroleum geologist

A petroleum geologist is an earth scientist who works in the field of petroleum geology, which involves all aspects of oil discovery and production. Petroleum geologists are usually linked to the actual discovery of oil and the identification of ...

George de Mohrenschildt

George Sergius de Mohrenschildt ( ru , Георгий Сергеевич де Мореншильд; April 17, 1911 – March 29, 1977) was an American petroleum geologist, professor, and known CIA informant. De Mohrenschildt is best known for havi ...

. Mohrenschildt would later write an extensive memoir in which he discussed his friendship with Oswald. Mohrenschildt's wife would later give the House Select Committee on Assassinations a photograph that showed Oswald in his Dallas backyard, holding two Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

newspapers and a Carcano

Carcano is the frequently used name for a series of Italian bolt-action, magazine-fed, repeating military rifles and carbines. Introduced in 1891, this rifle was chambered for the rimless 6.5×52mm Carcano round (''Cartuccia Modello 1895''). It ...

rifle, with a pistol on his hip. Thirteen years after the JFK assassination, in September 1976, the CIA requested that the FBI locate Mohrenschildt, in response to a letter Mohrenschildt had written to his friend, CIA Director George H. W. Bush, appealing to Bush to stop the agency from taking action against him.

Several Warren Commission critics, including Jesse Ventura

Jesse Ventura (born James George Janos; July 15, 1951) is an American politician, actor, and retired professional wrestler. After achieving fame in the World Wrestling Federation (WWF), he served as the 38th governor of Minnesota from 1999 to 2 ...

, have alleged that Mohrenschildt was one of Oswald's CIA handlers but have offered little evidence. Jim Garrison referred to Mohrenschildt as one of Oswald's unwitting "baby-sitters ... assigned to protect or otherwise see to the general welfare of Oswald". On March 29, 1977, Mohrenschildt stated during an interview with author Edward Jay Epstein

Edward Jay Epstein (born 1935) is an American investigative journalist and a former political science professor at Harvard University, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Early life and educa ...

that he had been asked by CIA operative J. Walton Moore to meet with Oswald, something Mohrenschildt had also told the Warren Commission thirteen years earlier. (When interviewed in 1978 by the House Select Committee on Assassinations, J. Walton Moore said that while he "had 'periodic' contact with Mohrenschildt", he had no recollection of any conversation with him concerning Oswald.) Mohrenschildt told Epstein that he would not have contacted Oswald had he not been asked to do so. Epstein, Edward Jay. ''The Assassination Chronicles: Inquest, Counterplot, and Legend'' (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1992), p. 559. (Mohrenschildt met with Oswald several times, from the summer of 1962 to April 1963.) The same day that Mohrenschildt was interviewed by Epstein, Mohrenschildt was informed by his daughter that a representative of the House Select Committee on Assassinations had stopped by and left his calling card, intending to return that evening. Mohrenschildt then committed suicide by shooting himself in the head shortly thereafter. Mohrenschildt's wife later told sheriff's office investigators that her husband had been hospitalized for depression and paranoia in late 1976 and had tried to kill himself four times that year.

Role of Oswald

In 1964, theWarren Commission

The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, known unofficially as the Warren Commission, was established by President Lyndon B. Johnson through on November 29, 1963, to investigate the assassination of United States P ...

concluded that Oswald assassinated President Kennedy and that Oswald acted alone, and that "there is no evidence that swaldwas involved in any conspiracy directed to the assassination of the President." The Commission came to this conclusion after examining Oswald's Marxist and pro-Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

background, including his defection to Russia, the New Orleans branch of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee he had organized, and the various public and private statements made by him espousing Marxism.

Some conspiracy theorists have argued that Oswald's pro-Communist behavior may have been a carefully planned ruse — a part of an effort by U.S. intelligence agencies to infiltrate left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

organizations in the United States and to conduct counterintelligence

Counterintelligence is an activity aimed at protecting an agency's intelligence program from an opposition's intelligence service. It includes gathering information and conducting activities to prevent espionage, sabotage, assassinations or ...

operations. Others have speculated that Oswald was an agent or informant of the U.S. government, and was manipulated by his U.S. intelligence handlers to incriminate himself while being set up as a scapegoat

In the Bible, a scapegoat is one of a pair of kid goats that is released into the wilderness, taking with it all sins and impurities, while the other is sacrificed. The concept first appears in the Book of Leviticus, in which a goat is designate ...

.

Oswald himself claimed to be innocent, denying all charges and even declaring to reporters that he was "just a patsy". He also insisted that the photos of him with a rifle had been faked, an assertion contradicted by statements made by his wife, Marina (who claimed to have taken the photos), and the analysis of photographic experts such as Lyndal L. Shaneyfelt of the FBI.

Some researchers have suggested that Oswald was an active agent of the Central Intelligence Agency, pointing to the fact that Oswald attempted to defect to Russia but was nonetheless able to return without difficulty (even receiving a repatriation loan from the State Department) as evidence of such. Oswald's mother, Marguerite, often insisted that her son was recruited by an agency of the U.S. Government and sent to Russia.Speculations and Rumors: Oswald and U.S. Government AgenciesWarren Commission Report, Appendix XII, p. 660. New Orleans District Attorney (and later judge)

Jim Garrison

James Carothers Garrison (born Earling Carothers Garrison; November 20, 1921 – October 21, 1992) was the District Attorney of Orleans Parish, Louisiana, from 1962 to 1973. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best known for his investigat ...

, who in 1967 brought Clay Shaw

Clay LaVergne Shaw (March 17, 1913 – August 15, 1974) was an American businessman and military officer from New Orleans, Louisiana. Shaw is best known for being the only person brought to trial for involvement in the assassination of John F. ...

to trial for the assassination of President Kennedy also held the opinion that Oswald was most likely a CIA agent who had been drawn into the plot to be used as a scapegoat, even going as far as to say that Oswald "genuinely was probably a hero".Turner, Nigel. ''The Men Who Killed Kennedy, Part 4, "The Patsy"'', 1991. Senator Richard Schweiker, a member of the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence

The United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (sometimes referred to as the Intelligence Committee or SSCI) is dedicated to overseeing the United States Intelligence Community—the agencies and bureaus of the federal government of ...

remarked that "everywhere you look with swald there're fingerprints of intelligence". Schweiker also told author David Talbot

David Talbot (born September 22, 1951) is an American journalist, author, activist and independent historian. Talbot is known for his books about the "hidden history" of U.S. power and the liberal movements to change America, as well as his p ...

that Oswald "was the product of a fake defector program run by the CIA." Richard Sprague

Richard E. Sprague (August 27, 1921 – January 27, 1996) was an American computer technician, researcher and author. According to American journalist Richard Russell, who dedicated seventeen years to the investigation of John Kennedy assassina ...

, interim staff director and chief counsel to the U.S. House Select Committee on Assassinations

The United States House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) was established in 1976 to investigate the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1963 and 1968, respectively. The HSCA completed its ...

, stated that if he "had to do it over again", he would have investigated the Kennedy assassination by probing Oswald's ties to the Central Intelligence Agency.

In 1978, James Wilcott, a former CIA finance officer, testified before the HSCA

The United States House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) was established in 1976 to investigate the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1963 and 1968, respectively. The HSCA completed its ...

that shortly after the assassination of President Kennedy he was advised by fellow employees at a CIA post abroad that Oswald was a CIA agent who had received financial disbursements under an assigned cryptonym. Wilcott was unable to identify the specific case officer who had initially informed him of Oswald's agency relationship, nor was he able to recall the name of the cryptonym, but he named several employees of the post abroad with whom he believed he had subsequently discussed the allegations. Later that year Wilcott and his wife, Elsie (also a former employee of the CIA), repeated those claims in an article in the ''San Francisco Chronicle

The ''San Francisco Chronicle'' is a newspaper serving primarily the San Francisco Bay Area of Northern California. It was founded in 1865 as ''The Daily Dramatic Chronicle'' by teenage brothers Charles de Young and Michael H. de Young. The pa ...

''. The HSCA investigated Wilcott's claims- including interviews with the chief and deputy chief of station, as well as officers in finance, registry, the Soviet Branch and counterintelligence - and concluded in their 1979 report they were "not worthy of belief".

Despite its official policy of neither confirming nor denying the status of agents, both the CIA itself and many officers working in the region at the time (including David Atlee Phillips) have "unofficially" dismissed the plausibility of any CIA ties to Oswald. Robert Blakey, staff director and chief counsel for the U.S. House Select Committee on Assassinations supported that assessment in his conclusions as well.

The House Select Committee on Assassinations found no evidence of any relationship between Oswald and the CIA.

Organized crime and a CIA conspiracy

Some conspiracy theorists have alleged a plot involving elements of the Mafia, the CIA and the anti-Castro Cubans, including authorAnthony Summers

Anthony Bruce Summers (born 21 December 1942) is an Irish author. He is a Pulitzer Prize Finalist and has written ten non-fiction books.

Career

Summers is an Irish citizen who has been working with Robbyn Swan for more than thirty years befo ...

and journalist Ruben Castaneda. They cite U.S. government documents which show that, beginning in 1960, these groups had worked together in assassination attempts against Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

n leader Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 20 ...

. Ruben Castaneda wrote: "Based on the evidence, it is likely that JFK was killed by a coalition of anti-Castro Cubans, the Mob, and elements of the CIA." In his book, ''They Killed Our President'', former Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

governor Jesse Ventura

Jesse Ventura (born James George Janos; July 15, 1951) is an American politician, actor, and retired professional wrestler. After achieving fame in the World Wrestling Federation (WWF), he served as the 38th governor of Minnesota from 1999 to 2 ...

also concluded: "John F. Kennedy was murdered by a conspiracy involving disgruntled CIA agents, anti-Castro Cubans, and members of the Mafia, all of whom were extremely angry at what they viewed as Kennedy's appeasement

Appeasement in an international context is a diplomatic policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the UK governme ...

policies toward Communist Cuba and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

."

Jack Van Lanningham, a prison cellmate of Mafia boss Carlos Marcello

Carlos Joseph Marcello (; born Calogero Minacore ; February 6, 1910 – March 3, 1993) was an Italian-American crime boss of the New Orleans crime family from 1947 until the late 1980s.

Aside from his role in the American Mafia, he is also n ...

, claimed that Marcello confessed to him in 1985 to having organized Kennedy's assassination. Lanningham also claimed that the FBI covered up the taped confession which he said the FBI had in its possession. Robert Blakey, who was chief counsel for the House Select Committee on Assassinations, concluded in his book, ''The Plot to Kill the President'', that Marcello was likely part of a Mafia conspiracy behind the assassination, and that the Mafia had the means, motive, and opportunity required to carry it out.Interview: G. Robert Blakey, November 19, 2013.

Notes

References

{{Disinformation Central Intelligence Agency John F. Kennedy assassination conspiracy theories Targeted killing Disinformation operations fr:Théories sur l'assassinat de John F. Kennedy#anchorCIA