C. V. Raman on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman (; 7 November 188821 November 1970) was an Indian physicist known for his work in the field of

, Official Nobel prize biography, nobelprize.org His second paper published in the same journal that year was on surface tension of liquids. It was alongside

Krishnan started the experiment in the beginning of January 1928. On 7 January, he discovered that no matter what kind of pure liquid he used, it always produced polarised fluorescence within the

Krishnan started the experiment in the beginning of January 1928. On 7 January, he discovered that no matter what kind of pure liquid he used, it always produced polarised fluorescence within the

Raman was honoured with many honorary doctorates and memberships of scientific societies. Within India, apart from being the founder and President of the Indian Academy of Sciences (FASc), he was a Fellow of the The Asiatic Society, Asiatic Society of Bengal (FASB), and from 1943, a Foundation Fellow of the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (FIAS). In 1935, he was appointed a Foundation Fellow of the National Institute of Sciences of India (FNI, now the Indian National Science Academy. He was a member of the Deutsche Akademie of Munich, the Swiss Physical Society of Zürich, the Royal Philosophical Society of Glasgow, the Royal Irish Academy, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, the Optical Society of America, the Mineralogical Society of America, the Romanian Academy of Sciences, the Catgut Acoustical Society of America and the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences.

In 1924, he was elected a

Raman was honoured with many honorary doctorates and memberships of scientific societies. Within India, apart from being the founder and President of the Indian Academy of Sciences (FASc), he was a Fellow of the The Asiatic Society, Asiatic Society of Bengal (FASB), and from 1943, a Foundation Fellow of the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (FIAS). In 1935, he was appointed a Foundation Fellow of the National Institute of Sciences of India (FNI, now the Indian National Science Academy. He was a member of the Deutsche Akademie of Munich, the Swiss Physical Society of Zürich, the Royal Philosophical Society of Glasgow, the Royal Irish Academy, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, the Optical Society of America, the Mineralogical Society of America, the Romanian Academy of Sciences, the Catgut Acoustical Society of America and the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences.

In 1924, he was elected a

C. V. Raman: 51 Success Facts - Everything You Need to Know About C. V. Raman

'. Lightning Source. *Koningstein, J.A. (2012).

Introduction to the Theory of the Raman Effect

'. Springer Science & Business Media. *Long, Derek A. (2002).

The Raman Effect: A Unified Treatment of the Theory of Raman Scattering by Molecules

'. Wiley. *Malti, Bansal (2012). C.V. Raman:

The Making of the Nobel Laureates

'. Mind Melodies. * *Raman, C. V. (1988).

Scientific Papers of C.V. Raman: Volume I–V

'. Indian Academy of Sciences. *Raman, C. V. (2010).

Why the Sky is Blue: Dr. C.V. Raman Talks about Science

'. Tulika Books. *Salwi, D. M. (2002).

C.V. Raman: The Scientist Extraordinary

'' Rupa & Company. *Singh R (2004).

Nobel Laureate C.V. Raman's Work on Light Scattering – Historical Contribution to a Scientific Biography

'. Logos Publisher, Berlin. *Sri Kantha S. (1988). The discovery of the Raman effect and its impact in biological sciences. ''European Spectroscopy News.'' 80, 20–26. *

The Nobel Prize in Physics 1930

at the Nobel Foundation * and his Nobel Lecture, 11 December 1930

Path creator – C.V. RamanArchive of all scientific papers of C.V. Raman

*

Scientific Papers of C. V. Raman, Volume 1Volume 2Volume 3Volume 4Volume 5Volume 6Raman Effect: fingerprinting the universe

* by Raja Choudhury and produced by PSBT and Indian Public Diplomacy. {{DEFAULTSORT:Raman, C. V. 1888 births 1970 deaths Presidency College, Chennai alumni Recipients of the Bharat Ratna Experimental physicists Indian optical physicists Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Indian National Science Academy Indian Nobel laureates Nobel laureates in Physics Indian agnostics 19th-century Indian physicists Indian institute directors Knights Bachelor Indian Knights Bachelor Tamil scientists University of Madras alumni University of Calcutta faculty Scientists from Tiruchirappalli Banaras Hindu University faculty Indian Institute of Science faculty Spectroscopists Raman scattering Chandrasekhar family 20th-century Indian physicists Indian Tamil politicians Indian quantum physicists Indian crystallographers Recipients of the Matteucci Medal

light scattering

Scattering is a term used in physics to describe a wide range of physical processes where moving particles or radiation of some form, such as light or sound, are forced to deviate from a straight trajectory by localized non-uniformities (including ...

.

Using a spectrograph

An optical spectrometer (spectrophotometer, spectrograph or spectroscope) is an instrument used to measure properties of light over a specific portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, typically used in spectroscopic analysis to identify mate ...

that he developed, he and his student K. S. Krishnan

Sir Kariamanikkam Srinivasa Krishnan, FRS, (4 December 1898 – 14 June 1961) was an Indian physicist. He was a co-discoverer of Raman scattering, for which his mentor C. V. Raman was awarded the 1930 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Early life

K ...

discovered that when light traverses a transparent material, the deflected light changes its wavelength

In physics, the wavelength is the spatial period of a periodic wave—the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.

It is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase on the wave, such as two adjacent crests, tr ...

and frequency

Frequency is the number of occurrences of a repeating event per unit of time. It is also occasionally referred to as ''temporal frequency'' for clarity, and is distinct from ''angular frequency''. Frequency is measured in hertz (Hz) which is eq ...

. This phenomenon, a hitherto unknown type of scattering of light, which they called "modified scattering" was subsequently termed the Raman effect or Raman scattering

Raman scattering or the Raman effect () is the inelastic scattering of photons by matter, meaning that there is both an exchange of energy and a change in the light's direction. Typically this effect involves vibrational energy being gained by ...

. Raman received the 1930 Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

for the discovery and was the first Asian to receive a Nobel Prize in any branch of science.

Born to Tamil Brahmin

Tamil Brahmins are an ethnoreligious community of Tamil-speaking Hindu Brahmins, predominantly living in Tamil Nadu, though they number significantly in Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Karnataka, in addition to other regions of India, as wel ...

parents, Raman was a precocious child, completing his secondary and higher secondary education from St Aloysius' Anglo-Indian High School at the ages of 11 and 13, respectively. He topped the bachelor's degree

A bachelor's degree (from Middle Latin ''baccalaureus'') or baccalaureate (from Modern Latin ''baccalaureatus'') is an undergraduate academic degree awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting three to si ...

examination of the University of Madras

The University of Madras (informally known as Madras University) is a public state university in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. Established in 1857, it is one of the oldest and among the most prestigious universities in India, incorporated by an a ...

with honours in physics from Presidency College at age 16. His first research paper, on diffraction of light, was published in 1906 while he was still a graduate student. The next year he obtained a master's degree

A master's degree (from Latin ) is an academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional practice.

. He joined the Indian Finance Service in Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, commer ...

as Assistant Accountant General at age 19. There he became acquainted with the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science

Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (IACS) is a public, deemed, research university for higher education and research in basic sciences under the Department of Science & Technology, Government of India, situated at the heart of ...

(IACS), the first research institute in India, which allowed him to carry out independent research and where he made his major contributions in acoustics

Acoustics is a branch of physics that deals with the study of mechanical waves in gases, liquids, and solids including topics such as vibration, sound, ultrasound and infrasound. A scientist who works in the field of acoustics is an acousticia ...

and optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultrav ...

.

In 1917, he was appointed the first Palit Professor of Physics

The Palit Chair of Physics is a physics professorship in the University of Calcutta, India. The post is named after Sir Taraknath Palit who donated Rs. 1.5 million to the university. The Nobel laureate physicist C. V. Raman was the first to be ap ...

by Ashutosh Mukherjee

Sir Ashutosh Mukherjee (anglicised, originally Asutosh Mukhopadhyay, also anglicised to Asutosh Mookerjee) (29 June 1864 – 25 May 1924) was a prolific Bengali educator, jurist, barrister and mathematician. He was the first student to be awa ...

at the Rajabazar Science College

The University College of Science, Technology and Agriculture (commonly or formerly known as Rashbehari Siksha Prangan & Taraknath Palit Siksha Prangan or Rajabazar Science College & Ballygunge Science College) are two of five main campuses of ...

under the University of Calcutta

The University of Calcutta (informally known as Calcutta University; CU) is a public collegiate state university in India, located in Kolkata, West Bengal, India. Considered one of best state research university all over India every yea ...

. On his first trip to Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, seeing the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

motivated him to identify the prevailing explanation for the blue colour of the sea at the time, namely the reflected Rayleigh-scattered light from the sky, as being incorrect. He founded the ''Indian Journal of Physics

The ''Indian Journal of Physics'' is a monthly peer-reviewed scientific journal published by Springer Science+Business Media on behalf of the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science. It was established in 1926 by C. V. Raman and covers ...

'' in 1926. He moved to Bangalore

Bangalore (), officially Bengaluru (), is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Karnataka. It has a population of more than and a metropolitan population of around , making it the third most populous city and fifth most ...

in 1933 to become the first Indian director of the Indian Institute of Science

The Indian Institute of Science (IISc) is a public, deemed, research university for higher education and research in science, engineering, design, and management. It is located in Bengaluru, in the Indian state of Karnataka. The institute was ...

. He founded the Indian Academy of Sciences

The Indian Academy of Sciences, Bangalore was founded by Indian Physicist and Nobel Laureate C. V. Raman, and was registered as a society on 24 April 1934. Inaugurated on 31 July 1934, it began with 65 founding fellows. The first general meet ...

the same year. He established the Raman Research Institute

The Raman Research Institute (RRI) is an institute for scientific research located in Bangalore, India. It was founded by Nobel laureate C. V. Raman in 1948. Although it began as an institute privately owned by Sir C. V. Raman, it is now fu ...

in 1948 where he worked to his last days.

The Raman effect was discovered on 28 February 1928. The day is celebrated annually by the Government of India

The Government of India ( ISO: ; often abbreviated as GoI), known as the Union Government or Central Government but often simply as the Centre, is the national government of the Republic of India, a federal democracy located in South Asia, ...

as the National Science Day

National Science Day is celebrated in India on February 28 each year to mark the discovery of the Raman effect by Indian physicist Sir C. V. Raman on 28 February 1928.

For his discovery, Sir C.V. Raman was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics i ...

. In 1954, the Government of India honoured him with the first Bharat Ratna

The Bharat Ratna (; ''Jewel of India'') is the highest Indian honours system, civilian award of the Republic of India. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is conferred in recognition of "exceptional service/performance of the highest orde ...

, its highest civilian award. He later smashed the medallion in protest against Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India du ...

's policies on scientific research.

Early life and education

C. V. Raman was born in Tiruchirapalli, Madras Presidency,British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was him ...

(now Tiruchirapalli

Tiruchirappalli () ( formerly Trichinopoly in English), also called Tiruchi or Trichy, is a major tier II city in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu and the administrative headquarters of Tiruchirappalli district. The city is credited with bein ...

, Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is a state in southern India. It is the tenth largest Indian state by area and the sixth largest by population. Its capital and largest city is Chennai. Tamil Nadu is the home of the Tamil people, whose Tamil language ...

), to Tamil Brahmin

Tamil Brahmins are an ethnoreligious community of Tamil-speaking Hindu Brahmins, predominantly living in Tamil Nadu, though they number significantly in Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Karnataka, in addition to other regions of India, as wel ...

parents, Chandrasekhara Ramanathan Iyer and Parvathi Ammal. He was the second of eight siblings. His father was a teacher at a local high school, and earned a modest income. He recalled: "I was born with a copper spoon in my mouth. At my birth my father was earning the magnificent salary of ten rupees per month!" In 1892, his family moved to Visakhapatnam

, image_alt =

, image_caption = From top, left to right: Visakhapatnam aerial view, Vizag seaport, Simhachalam Temple, Aerial view of Rushikonda Beach, Beach road, Novotel Visakhapatnam, INS Kursura submarine museu ...

(then Vishakapatnam, Vizagapatam or Vizag) in Andhra Pradesh

Andhra Pradesh (, abbr. AP) is a state in the south-eastern coastal region of India. It is the seventh-largest state by area covering an area of and tenth-most populous state with 49,386,799 inhabitants. It is bordered by Telangana to the ...

as his father was appointed to the faculty of physics at Mrs A.V. Narasimha Rao College.

Raman was educated at the St Aloysius' Anglo-Indian High School, Visakhapatnam

, image_alt =

, image_caption = From top, left to right: Visakhapatnam aerial view, Vizag seaport, Simhachalam Temple, Aerial view of Rushikonda Beach, Beach road, Novotel Visakhapatnam, INS Kursura submarine museu ...

. He passed matriculation at age 11 and the First Examination in Arts examination (equivalent to today's intermediate examination, pre-university course

The Pre-University Course or Pre-Degree Course (PUC or PDC) is an 2-year Senior Secondary Course under the 10+2 education system after Class 10th (SSLC, SSC) and the PUC commonly refers to Class 11th and Class 12th and called as 1st PUC (1st Year ...

) with a scholarship at age 13, securing first position in both under the Andhra Pradesh school board (now Andhra Pradesh Board of Secondary Education) examination.

In 1902, Raman joined Presidency College in Madras (now Chennai

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

) where his father had been transferred to teach mathematics and physics. In 1904, he obtained a B.A.

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four yea ...

degree from the University of Madras

The University of Madras (informally known as Madras University) is a public state university in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. Established in 1857, it is one of the oldest and among the most prestigious universities in India, incorporated by an a ...

, where he stood first and won the gold medals in physics and English. At age 18, while still a graduate student, he published his first scientific paper on "Unsymmetrical diffraction bands due to a rectangular aperture" in the British journal ''Philosophical Magazine

The ''Philosophical Magazine'' is one of the oldest scientific journals published in English. It was established by Alexander Tilloch in 1798;John Burnett"Tilloch, Alexander (1759–1825)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford Univer ...

'' in 1906. He earned an M.A.

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

degree from the same university with highest distinction in 1907.The Nobel Prize in Physics 1930 Sir Venkata Raman, Official Nobel prize biography, nobelprize.org His second paper published in the same journal that year was on surface tension of liquids. It was alongside

Lord Rayleigh

John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh, (; 12 November 1842 – 30 June 1919) was an English mathematician and physicist who made extensive contributions to science. He spent all of his academic career at the University of Cambridge. A ...

's paper on the sensitivity of ear to sound, and from which Lord Rayleigh started to communicate with Raman, courteously addressing him as "Professor."

Aware of Raman's capacity, his physics teacher Rhishard Llewellyn Jones insisted he continue research in England. Jones arranged for Raman's physical inspection with Colonel (Sir Gerald) Giffard. Raman often had poor health and was considered as a "weakling." The inspection revealed that he would not withstand the harsh weathers of England, the incident of which he later recalled, and said, " iffardexamined me and certified that I was going to die of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

… if I were to go to England."

Career

Raman's elder brother Chandrasekhara Subrahmanya Ayyar had joined the Indian Finance Service (nowIndian Audit and Accounts Service

Indian Audit and Accounts Service is a Central Group 'A' central civil service under the Comptroller and Auditor General of India, Government of India. The central civil servants under the Indian Audit and Accounts Service serve in an audit man ...

), the most prestigious government service in India. In no condition to study abroad, Raman followed suit and qualified for the Indian Finance Service achieving first position in the entrance examination in February 1907. He was posted in Calcutta (now Kolkata

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, comme ...

) as Assistant Accountant General in June 1907. It was there that he became highly impressed with the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science

Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (IACS) is a public, deemed, research university for higher education and research in basic sciences under the Department of Science & Technology, Government of India, situated at the heart of ...

(IACS), the first research institute founded in India in 1876. He immediately befriended Asutosh Dey, who would eventually become his lifelong collaborator, Amrita Lal Sircar, founder and secretary of IACS, and Ashutosh Mukherjee

Sir Ashutosh Mukherjee (anglicised, originally Asutosh Mukhopadhyay, also anglicised to Asutosh Mookerjee) (29 June 1864 – 25 May 1924) was a prolific Bengali educator, jurist, barrister and mathematician. He was the first student to be awa ...

, executive member of the institute and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Calcutta

The University of Calcutta (informally known as Calcutta University; CU) is a public collegiate state university in India, located in Kolkata, West Bengal, India. Considered one of best state research university all over India every yea ...

. With their support, he obtained permission to conduct research at IACS in his own time even "at very unusual hours," as Raman later reminisced. Up to that time the institute had not yet recruited regular researchers, or produced any research paper. Raman's article "Newton's rings in polarised light" published in ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

'' in 1907 became the first from the institute. The work inspired IACS to publish a journal, ''Bulletin of Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science,'' in 1909 in which Raman was the major contributor.

In 1909, Raman was transferred to Rangoon

Yangon ( my, ရန်ကုန်; ; ), formerly spelled as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar (also known as Burma). Yangon served as the capital of Myanmar until 2006, when the military government ...

, British Burma

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

(now Myanmar

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

), to take up the position of currency officer. After only a few months, he had to return to Madras as his father died from an illness. The subsequent death of his father and funeral rituals compelled him to remain there for the rest of the year. Soon after he resumed office at Rangoon, he was transferred back to India at Nagpur

Nagpur (pronunciation: aːɡpuːɾ is the third largest city and the winter capital of the Indian state of Maharashtra. It is the 13th largest city in India by population and according to an Oxford's Economics report, Nagpur is projected to ...

, Maharashtra, in 1910. Even before he served a year in Nagpur, he was promoted to Accountant General in 1911 and again posted to Calcutta.

From 1915, the University of Calcutta started assigning research scholars under Raman at IACS. Sudhangsu Kumar Banerji (who later become Director General of Observatories of India Meteorological Department

The India Meteorological Department (IMD) is an agency of the Ministry of Earth Sciences of the Government of India. It is the principal agency responsible for meteorological observations, weather forecasting and seismology. IMD is headquarter ...

), a PhD scholar under Ganesh Prasad

Ganesh Prasad (15 November 1876 – 9 March 1935) was an Indian mathematician who specialised in the theory of potentials, theory of functions of a real variable, Fourier series and the theory of surfaces. He was trained at the Universities o ...

, was his first student. From the next year, other universities followed suit including University of Allahabad

, mottoeng = "As Many Branches So Many Trees"

, established =

, type = Public

, chancellor = Ashish Chauhan

, vice_chancellor = Sangita Srivastava

, head_label ...

, Rangoon University

'')

, mottoeng = There's no friend like wisdom.

, established =

, type = Public

, rector = Dr. Tin Mg Tun

, undergrad = 4194

, postgrad = 5748

, city = Kamayut 11041, Yangon

, state = Yangon Regio ...

, Queen's College Indore, Institute of Science, Nagpur, Krisnath College, and University of Madras. By 1919, Raman had guided more than a dozen students. Following Sircar's death in 1919, Raman received two honorary positions at IACS, Honorary Professor and Honorary Secretary. He referred to this period as the "golden era" of his life.

Raman was chosen by the University of Calcutta

The University of Calcutta (informally known as Calcutta University; CU) is a public collegiate state university in India, located in Kolkata, West Bengal, India. Considered one of best state research university all over India every yea ...

to become the Palit Professor of Physics

The Palit Chair of Physics is a physics professorship in the University of Calcutta, India. The post is named after Sir Taraknath Palit who donated Rs. 1.5 million to the university. The Nobel laureate physicist C. V. Raman was the first to be ap ...

, a position established after the benefactor Sir Taraknath Palit, in 1913. The university senate made the appointment on 30 January 1914, as recorded in the meeting minutes:Prior to 1914, Ashutosh Mukherjee had invited Jagadish Chandra Bose

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose

(;, ; 30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a biologist, physicist, botanist and an early writer of science fiction. He was a pioneer in the investigation of radio microwave optics, made significant contribution ...

to take up the position, but Bose declined. As a second choice, Raman became the first Palit Professor of Physics but was delayed for taking up the position as World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

broke out. It was only in 1917 when he joined Rajabazar Science College

The University College of Science, Technology and Agriculture (commonly or formerly known as Rashbehari Siksha Prangan & Taraknath Palit Siksha Prangan or Rajabazar Science College & Ballygunge Science College) are two of five main campuses of ...

, a campus created by the University of Calcutta in 1914, that he became a full-fledged professor. He reluctantly resigned as a civil servant after a decade of service, which was described as "supreme sacrifice" since his salary as a professor would be roughly half of his salary at the time. But to his advantage, the terms and conditions as a professor were explicitly indicated in the report of his joining the university, which stated:Raman's appointment as the Palit Professor was strongly objected to by some members of the Senate of the University of Calcutta, especially foreign members, as he had no PhD PHD or PhD may refer to:

* Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), an academic qualification

Entertainment

* '' PhD: Phantasy Degree'', a Korean comic series

* '' Piled Higher and Deeper'', a web comic

* Ph.D. (band), a 1980s British group

** Ph.D. (Ph.D. al ...

and had never studied abroad. As a kind of rebuttal, Mukherjee arranged for an honorary DSc which the University of Calcutta conferred Raman in 1921. The same year he visited Oxford to deliver a lecture at the Congress of Universities of the British Empire. He had earned quite a reputation by then, and his hosts were Nobel laureates J. J. Thomson and Lord Rutherford. Upon his election as Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemati ...

in 1924, Mukherjee asked him of his future plans, which he replied, saying, "The Nobel Prize of course." In 1926, he established the ''Indian Journal of Physics

The ''Indian Journal of Physics'' is a monthly peer-reviewed scientific journal published by Springer Science+Business Media on behalf of the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science. It was established in 1926 by C. V. Raman and covers ...

'' and acted as the first editor. The second volume of the journal published his famous article "A new radiation", reporting the discovery of the Raman effect

Raman scattering or the Raman effect () is the inelastic scattering of photons by matter, meaning that there is both an exchange of energy and a change in the light's direction. Typically this effect involves vibrational energy being gained by ...

.

Raman was succeeded by Debendra Mohan Bose

Debendra Mohan Bose (26 November 1885 – 2 June 1975) was an Indian physicist who made contributions in the field of cosmic rays, artificial radioactivity and neutron physics. He was the longest serving Director (1938–1967) of Bose Institut ...

as the Palit Professor in 1932. Following his appointment as Director of the Indian Institute of Science

The Indian Institute of Science (IISc) is a public, deemed, research university for higher education and research in science, engineering, design, and management. It is located in Bengaluru, in the Indian state of Karnataka. The institute was ...

(IISc) in Bangalore

Bangalore (), officially Bengaluru (), is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Karnataka. It has a population of more than and a metropolitan population of around , making it the third most populous city and fifth most ...

, he left Calcutta in 1933. Maharaja Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV

Maharaja Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV (Nalwadi Krishnaraja Wadiyar; 4 June 1884 – 3 August 1940) was the twenty-fourth maharaja of the Kingdom of Mysore, from 1902 until his death in 1940. He is popularly called '' Rajarshi'' ( sa, rājarṣi, li ...

, the King of Mysore, Jamsetji Tata

Jamsetji (Jamshedji) Nusserwanji Tata (3 March 1839 – 19 May 1904) was an Indian pioneer industrialist who founded the Tata Group, India's biggest conglomerate company. Named the greatest philanthropist of the last century by several pol ...

and Nawab

Nawab ( Balochi: نواب; ar, نواب;

bn, নবাব/নওয়াব;

hi, नवाब;

Punjabi : ਨਵਾਬ;

Persian,

Punjabi ,

Sindhi,

Urdu: ), also spelled Nawaab, Navaab, Navab, Nowab, Nabob, Nawaabshah, Nawabshah or Nobab, ...

Sir Mir Osman Ali Khan

Mir Osman Ali Khan, Asaf Jah VII (5 or 6 April 1886 — 24 February 1967), was the last Nizam (ruler) of the Princely State of Hyderabad, the largest princely state in British India. He ascended the throne on 29 August 1911, at the age o ...

, the Nizam of Hyderabad

The Nizams were the rulers of Hyderabad from the 18th through the 20th century. Nizam of Hyderabad (Niẓām ul-Mulk, also known as Asaf Jah) was the title of the monarch of the Hyderabad State ( divided between the state of Telangana, Mar ...

, had contributed the lands and funds for the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore. The Viceroy of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

, Lord Minto

Earl of Minto, in the County of Roxburgh, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1813 for Gilbert Elliot-Murray-Kynynmound, 1st Baron Minto. The current earl is Gilbert Timothy George Lariston Elliot-Murray-Kynynm ...

approved the establishment in 1909, and the British government appointed its first director, Morris Travers

Morris William Travers, FRS (24 January 1872 – 25 August 1961) was an English chemist who worked with Sir William Ramsay in the discovery of xenon, neon and krypton. His work on several of the rare gases earned him the name ''Rare gas T ...

. Raman became the fourth director and the first Indian director. During his tenure at IISc, he recruited G. N. Ramachandran

Gopalasamudram Narayanan Ramachandran, or G.N. Ramachandran, FRS (8 October 1922 – 7 April 2001) was an Indian physicist who was known for his work that led to his creation of the Ramachandran plot for understanding peptide structure. He wa ...

, who later went on to become a distinguished X-ray crystallographer

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angle ...

. He founded the Indian Academy of Sciences in 1934 and started publishing the academy's journal ''Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences'' (later split up into '' Proceedings - Mathematical Sciences, Journal of Chemical Sciences,'' and '' Journal of Earth System Science''). Around that time the Calcutta Physical Society was established, the concept of which he had initiated early in 1917.

With his former student Panchapakesa Krishnamurti, Raman started a company called Travancore Chemical and Manufacturing Co. Ltd. in 1943. The company, renamed as TCM Limited in 1996, was one of the first organic and inorganic chemical manufacturers in India. In 1947, Raman was appointed the first National Professor by the new government of independent India.

Raman retired from IISC in 1948 and established the Raman Research Institute

The Raman Research Institute (RRI) is an institute for scientific research located in Bangalore, India. It was founded by Nobel laureate C. V. Raman in 1948. Although it began as an institute privately owned by Sir C. V. Raman, it is now fu ...

in Bangalore a year later. He served as its director and remained active there until his death in 1970.

Scientific contributions

Musical sound

One of Raman's interests was on the scientific basis of musical sounds. He was inspired byHermann von Helmholtz

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (31 August 1821 – 8 September 1894) was a German physicist and physician who made significant contributions in several scientific fields, particularly hydrodynamic stability. The Helmholtz Associat ...

's ''The Sensations of Tone'', the book he came across when he joined IACS. He published his findings prolifically between 1916 and 1921. He worked out the theory of transverse

Transverse may refer to:

*Transverse engine, an engine in which the crankshaft is oriented side-to-side relative to the wheels of the vehicle

* Transverse flute, a flute that is held horizontally

* Transverse force (or ''Euler force''), the tange ...

vibration of bowed string instrument

Bowed string instruments are a subcategory of string instruments that are played by a bow rubbing the strings. The bow rubbing the string causes vibration which the instrument emits as sound.

Despite the numerous specialist studies devoted to ...

s based on superposition of velocities. One of his earliest studies was on the wolf tone

A wolf tone, or simply a "wolf", is an undesirable phenomenon that occurs in some bowed-string instruments, most famously in the cello. It happens when the pitch of the played note is close to a particularly strong natural resonant frequency of th ...

in violins and cellos. He studied the acoustics

Acoustics is a branch of physics that deals with the study of mechanical waves in gases, liquids, and solids including topics such as vibration, sound, ultrasound and infrasound. A scientist who works in the field of acoustics is an acousticia ...

of various violin and related instruments, including Indian stringed instruments, and water splashes. He even performed what he called "Experiments with mechanically-played violins."

Raman also studied the uniqueness of Indian drums. His analyses of the harmonic

A harmonic is a wave with a frequency that is a positive integer multiple of the ''fundamental frequency'', the frequency of the original periodic signal, such as a sinusoidal wave. The original signal is also called the ''1st harmonic'', t ...

nature of the sounds of tabla

A tabla, bn, তবলা, prs, طبلا, gu, તબલા, hi, तबला, kn, ತಬಲಾ, ml, തബല, mr, तबला, ne, तबला, or, ତବଲା, ps, طبله, pa, ਤਬਲਾ, ta, தபலா, te, తబల� ...

and mridangam

The mridangam is a percussion instrument of ancient origin. It is the primary rhythmic accompaniment in a Carnatic music ensemble. In Dhrupad, a modified version, the pakhawaj, is the primary percussion instrument. A related instrument is th ...

were the first scientific studies on Indian percussions. He wrote a critical research on vibrations of the pianoforte string that was known as Kaufmann's theory. During his brief visit of England in 1921, he managed to study how sound travels in the Whispering Gallery

The Whispering Gallery of St Paul's Cathedral, London

A whispering gallery is usually a circular, hemispherical, elliptical or ellipsoidal enclosure, often beneath a dome or a vault, in which whispers can be heard clearly in other parts of t ...

of the dome of St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglicanism, Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London ...

in London that produces unusual sound effects. His work on acoustics was an important prelude, both experimentally and conceptually, to his later works on optics and quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistry, ...

.

Blue colour of the sea

Raman, in his broadening venture on optics, started to investigate scattering of light starting in 1919. His first phenomenal discovery of the physics of light was the blue colour of seawater. During a voyage home from England on board the ''S.S. Narkunda'' in September 1921, he contemplated the blue colour of theMediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

. Using simple optical equipment, a pocket-sized spectroscope

An optical spectrometer (spectrophotometer, spectrograph or spectroscope) is an instrument used to measure properties of light over a specific portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, typically used in spectroscopic analysis to identify mate ...

and a Nicol prism

A Nicol prism is a type of polarizer, an optical device made from calcite crystal used to produce and analyse plane polarized light. It is made in such a way that it eliminates one of the rays by total internal reflection, i.e. the ordinary ray ...

in hand, he studied the seawater. Of several hypotheses on the colour of the sea propounded at the time, the best explanation had been that of Lord Rayleigh

John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh, (; 12 November 1842 – 30 June 1919) was an English mathematician and physicist who made extensive contributions to science. He spent all of his academic career at the University of Cambridge. A ...

's in 1910, according to which, "The much admired dark blue of the deep sea has nothing to do with the colour of water, but is simply the blue of the sky seen by reflection". Rayleigh had correctly described the nature of the blue sky by a phenomenon now known as Rayleigh scattering

Rayleigh scattering ( ), named after the 19th-century British physicist Lord Rayleigh (John William Strutt), is the predominantly elastic scattering of light or other electromagnetic radiation by particles much smaller than the wavelength of th ...

, the scattering of light and refraction by particles in the atmosphere. His explanation of the blue colour of water was instinctively accepted as correct. Raman could view the water using Nicol prism to avoid the influence of sunlight reflected by the surface. He described how the sea appears even more blue than usual, contradicting Rayleigh.

As soon as the ''S.S. Narkunda'' docked in Bombay Harbour (now Mumbai Harbour

Mumbai Harbour (also English; Bombay Harbour or Front Bay, Marathi''Mumba'ī bandar''), is a natural deep-water harbour in the southern portion of the Ulhas River estuary. The narrower, northern part of the estuary is called Thana Creek. The ...

), Raman finished an article "The colour of the sea" that was published in the November 1921 issue of ''Nature''. He noted that Rayleigh's explanation is "questionable by a simple mode of observation" (using Nicol prism). As he thought:

When he reached Calcutta, he asked his student K. R. Ramanathan, who was from the University of Rangoon, to conduct further research at IACS. By early 1922, Raman came to a conclusion, as he reported in the '' Proceedings of the Royal Society of London'':True to his words, Ramanathan published an elaborate experimental finding in 1923. His subsequent study of the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean, bounded on the west and northwest by India, on the north by Bangladesh, and on the east by Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India. Its southern limit is a line bet ...

in 1924 provided the full evidence. It is now known that the intrinsic colour of water is mainly attributed to the selective absorption of longer wavelengths of light in the red and orange regions of the spectrum

A spectrum (plural ''spectra'' or ''spectrums'') is a condition that is not limited to a specific set of values but can vary, without gaps, across a continuum. The word was first used scientifically in optics to describe the rainbow of colors ...

, owing to overtones of the infrared

Infrared (IR), sometimes called infrared light, is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with wavelengths longer than those of Light, visible light. It is therefore invisible to the human eye. IR is generally understood to encompass wavelengths from ...

absorbing O-H (oxygen and hydrogen combined) stretching modes of water molecules.

Raman effect

Background

Raman's second important discovery on the scattering of light was a new type of radiation, an eponymous phenomenon called the Raman effect. After discovering the nature of light scattering that caused blue colour of water, he focused on the principle behind the phenomenon. His experiments in 1923 showed the possibility of other light rays formed in addition toincident ray

In optics a ray is an idealized geometrical model of light, obtained by choosing a curve that is perpendicular to the ''wavefronts'' of the actual light, and that points in the direction of energy flow. Rays are used to model the propagation o ...

when sunlight was filtered through a violet glass in certain liquids and solids. Ramanathan believed that this was a case of a "trace of fluorescence

Fluorescence is the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. It is a form of luminescence. In most cases, the emitted light has a longer wavelength, and therefore a lower photon energy, tha ...

." In 1925, K. S. Krishnan

Sir Kariamanikkam Srinivasa Krishnan, FRS, (4 December 1898 – 14 June 1961) was an Indian physicist. He was a co-discoverer of Raman scattering, for which his mentor C. V. Raman was awarded the 1930 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Early life

K ...

, a new Research Associate, noted the theoretical background for the existence of an additional scattering line beside the usual polarised elastic scattering when light scatters through liquid. He referred to the phenomenon as "feeble fluorescence." But the theoretical attempts to justify the phenomenon were quite futile for the next two years.

The major impetus was the discovery of Compton effect

Compton scattering, discovered by Arthur Holly Compton, is the scattering of a high frequency photon after an interaction with a charged particle, usually an electron. If it results in a decrease in energy (increase in wavelength) of the photon ...

. Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for his 1923 discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radia ...

at Washington University in St. Louis had found evidence in 1923 that electromagnetic waves

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EMR) consists of waves of the electromagnetic (EM) field, which propagate through space and carry momentum and electromagnetic radiant energy. It includes radio waves, microwaves, infrared, (visible) ...

can also be described as particles. By 1927, the phenomenon was widely accepted by scientists, including Raman. As the news of Compton's Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

was announced in December 1927, Raman ecstatically told Krishnan, saying:But the origin of the inspiration went further. As Compton later recollected "that it was probably the Toronto debate that led him to discover the Raman effect two years later." The Toronto debate was about the discussion on the existence of light quantum at the British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chi ...

meeting held at Toronto in 1924. There Compton presented his experimental findings, which William Duane of Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

argued with his own with evidence that light was a wave. Raman took Duane's side and said, "Compton, you're a very good debater, but the truth isn't in you."

The scattering experiments

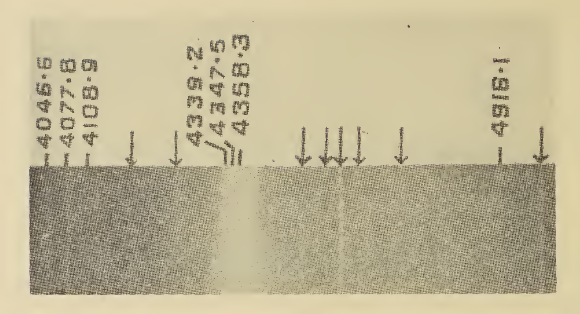

Krishnan started the experiment in the beginning of January 1928. On 7 January, he discovered that no matter what kind of pure liquid he used, it always produced polarised fluorescence within the

Krishnan started the experiment in the beginning of January 1928. On 7 January, he discovered that no matter what kind of pure liquid he used, it always produced polarised fluorescence within the visible spectrum

The visible spectrum is the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum that is visible to the human eye. Electromagnetic radiation in this range of wavelengths is called '' visible light'' or simply light. A typical human eye will respond to ...

of light. As Raman saw the result, he was astonished why he never observed such phenomenon all those years. That night he and Krishnan named the new phenomenon as "modified scattering" with reference to the Compton effect as an unmodified scattering. On 16 February, they sent a manuscript to ''Nature'' titled "A new type of secondary radiation", which was published on 31 March.

On 28 February 1928, they obtained spectra of the modified scattering separate from the incident light. Due to difficulty in measuring the wavelengths of light, they had been relying on visual observation of the colour produced from sunlight through prism. Raman had invented a type of spectrograph

An optical spectrometer (spectrophotometer, spectrograph or spectroscope) is an instrument used to measure properties of light over a specific portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, typically used in spectroscopic analysis to identify mate ...

for detecting and measuring electromagnetic waves. Referring to the invention, Raman later remarked, "When I got my Nobel Prize, I had spent hardly 200 rupees on my equipment," although it was obvious that his total expenditure for the entire experiment was much more than that. From that moment they could employ the instrument using monochromatic light {{Short description, Electromagnetic radiation with a single constant frequency

In physics, monochromatic radiation is electromagnetic radiation with a single constant frequency. When that frequency is part of the visible spectrum (or near it) the ...

from a mercury arc lamp which penetrated transparent material and was allowed to fall on a spectrograph to record its spectrum. The lines of scattering could now be measured and photographed.Venkataraman, G. (1988) ''Journey into Light: Life and Science of C. V. Raman''. Oxford University Press. .

Announcement

The same day, Raman made the announcement before the press. The '' Associated Press of India'' reported it the next day, on 29 February, as "New theory of radiation: Prof. Raman's Discovery." It ran the story as:The news was reproduced by '' The Statesman'' on 1 March under the headline "Scattering of Light by Atoms – New Phenomenon – Calcutta Professor's Discovery." Raman submitted a three-paragraph report of the discovery on 8 March to ''Nature'' and was published on 21 April. The actual data was sent to the same journal on 22 March and was published on 5 May. Raman presented the formal and detail description as "A new radiation" at the meeting of South Indian Science Association in Bangalore on 16 March. His lecture was published in the ''Indian Journal of Physics

The ''Indian Journal of Physics'' is a monthly peer-reviewed scientific journal published by Springer Science+Business Media on behalf of the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science. It was established in 1926 by C. V. Raman and covers ...

'' on 31 March. 1,000 copies of the paper reprint were sent to scientists in different countries on that day.

Reception and outcome

Some physicists, particularly French and German physicists were initially sceptical of the authenticity of the discovery.Georg Joos

Georg Jakob Christof Joos (25 May 1894 in Bad Urach, German Empire – 20 May 1959 in Munich, West Germany) was a German experimental physicist. He wrote ''Lehrbuch der theoretischen Physik'', first published in 1932 and one of the most influ ...

at the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena

The University of Jena, officially the Friedrich Schiller University Jena (german: Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, abbreviated FSU, shortened form ''Uni Jena''), is a public research university located in Jena, Thuringia, Germany.

The un ...

asked Arnold Sommerfeld at the University of Munich, "Do you think that Raman's work on the optical Compton effect in liquids is reliable?... The sharpness of the scattered lines in liquids seems doubtful to me". Sommerfeld then tried to reproduce the experiment, but failed. On 20 June 1928, Peter Pringsheim at the University of Berlin was able to reproduce Raman's results successfully. He was the first to coin the terms ''Ramaneffekt'' and ''Linien des Ramaneffekts'' in his articles published the following months. Use of the English versions, "Raman effect" and "Raman lines" immediately followed.

In addition to being a new phenomenon itself, the Raman effect was one of the earliest proofs of the Light#Quantum theory, quantum nature of light. Robert W. Wood at the Johns Hopkins University was the first American to confirm the Raman effect in the early 1929. He made a series of experimental verification, after which he commented, saying, "It appears to me that this very beautiful discovery which resulted from Raman's long and patient study of the phenomenon of light scattering is one of the most convincing proofs of the quantum theory". The field of Raman spectroscopy came to be based on this phenomenon, and Ernest Rutherford, President of the Royal Society, referred to it in his presentation of the Hughes Medal to Raman in 1930 as "among the best three or four discoveries in experimental physics in the last decade".

Raman was confident that he would win the Nobel Prize in Physics as well but was disappointed when the Nobel Prize went to Owen Richardson in 1928 and to Louis de Broglie in 1929. He was so confident of winning the prize in 1930 that he booked tickets in July, even though the awards were to be announced in November. He would scan each day's newspaper for announcement of the prize, tossing it away if it did not carry the news. He did eventually win that year.

Later work

Raman had association with the Banaras Hindu University in Varanasi. He attended the foundation ceremony of BHU and delivered lectures on mathematics and "Some new paths in physics" during the lecture series organised at the university from 5 to 8 February 1916. He also held the position of permanent visiting professor. With Suri Bhagavantam, he determined the Spin (physics), spin of photons in 1932, which further confirmed the quantum nature of light. With another student, Nagendra Nath, he provided the correct theoretical explanation for the Acousto-optics, acousto-optic effect (light scattering by sound waves) in a series of articles resulting in the celebrated Raman–Nath theory. Modulators, and switching systems based on this effect have enabled optical communication components based on laser systems. Other investigations he carried out included experimental and theoretical studies on the diffraction of light by acoustic waves of Ultrasound, ultrasonic and hypersonic frequencies, and those on the effects produced by X-rays on infrared vibrations in crystals exposed to ordinary light which were published between 1935 and 1942. In 1948, through studying the Spectroscopy, spectroscopic behaviour of crystals, he approached the fundamental problems of crystal dynamics in a new manner. He dealt with the structure and properties of diamond from 1944 to 1968, the structure and optical behaviour of numerous Iridescence, iridescent substances including labradorite, pearly feldspar, agate, quartz, opal, and pearl in the early 1950s. Among his other interests were the optics of colloids, and electrical and magnetic anisotropy. His last interests in the 1960s were on biological properties such as the colours of flowers and the Visual system, physiology of human vision.Personal life

Raman married Lokasundari Ammal (1892–1980) on 6 May 1907. It was a self-arranged marriage and his wife was 13 years old. His wife later jokingly recounted that their marriage was not so much about her musical prowess (she was playing ''veena'' when they first met) as "the extra allowance which the Finance Department gave to its married officers." The extra allowance refers to an additional INR 150 for married officers at the time. Soon after they moved to Calcutta in 1907, the couple were accused of converting to Christianity. It was because they frequently visited St. John's Church, Kolkata as Lokasundari was fascinated with the church music and Raman with the acoustics. They had two sons, Chandrasekhar Raman and Venkatraman Radhakrishnan, a radio astronomer. Raman was the paternal uncle of Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, recipient of the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physics. Throughout his life, Raman developed an extensive personal collection of stones, minerals, and materials with interesting light-scattering properties, which he obtained from his world travels and as gifts. He often carried a small, handheld Optical spectrometer, spectroscope to study specimens. These, along with his spectrograph, are on display at IISc. Lord Rutherford was instrumental in some of Raman's most pivotal moments in life. He nominated Raman for the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1930, presented him the Hughes Medal as President of the Royal Society in 1930, and recommended him for the position of Director at IISc in 1932. Raman had a sense of obsession with the Nobel Prize. In a speech at the University of Calcutta, he said, "I'm not flattered by the honour [Fellowship to the Royal Society in 1924] done to me. This is a small achievement. If there is anything that I aspire for, it is the Nobel Prize. You will find that I get that in five years." He knew that if he were to receive the Nobel Prize, he could not wait for the announcement of the Nobel Committee normally made towards the end of the year considering the time required to reach Sweden by sea route. With confidence, he booked two tickets, one for his wife, for a steamship to Stockholm in July 1930. Soon after he received the Nobel Prize, he was asked in an interview the possible consequences if he had discovered the Raman effect earlier, which he replied, "Then I should have shared the Nobel Prize with Compton and I should not have liked that; I would rather receive the whole of it."Religious views

Although Raman hardly talked about religion, he was openly an agnostic, but objected to being labelled atheist. His agnosticism was largely influenced by that of his father who adhered to the philosophies of Herbert Spencer, Charles Bradlaugh, and Robert G. Ingersoll. He resented Sanskara (rite of passage), Hindu traditional rituals but did not give them up in family circles. He was also influenced by the philosophy of ''Advaita Vedanta''. Traditional ''Pagri (turban), pagri'' (Indian turban) with a tuft underneath and a ''upanayana'' (Hindu sacred thread) were his signature attire. Though it was not customary to wear turbans in South Indian culture, he explained his habit as, "Oh, if I did not wear one, my head will swell. You all praise me so much and I need a turban to contain my ego." He even attributed his turban for the recognition he received on his first visit to England, particular from J. J. Thomson and Lord Rutherford. In a public speech, he once said,In a friendly meeting with Mahatma Gandhi and Gilbert Rahm, a German zoologist, the conversation turned to religion. Raman spoke,On his deathbed, he said to his wife, "I believe only in the Spirit of Man," and asked for his funeral, "Just a clean and simple cremation for me, no mumbo-jumbo please."Death

At the end of October 1970, Raman had a cardiac arrest and collapsed in his laboratory. He was moved to the hospital where doctors diagnosed his condition and declared that he would not survive another four hours. He however survived a few days and requested to stay in the gardens of his institute surrounded by his followers. Two days before Raman died, he told one of his former students, "Do not allow the journals of the Academy to die, for they are the sensitive indicators of the quality of science being done in the country and whether science is taking root in it or not." That evening, Raman met with the Board of Management of his institute in his bedroom and discussed with them the fate of the institute's management. He also willed his wife to perform a simple cremation without any rituals upon his death. He died from natural causes early the next morning on 21 November 1970 at the age of 82. On the news of Raman's death, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi publicly announced, saying,Controversies

The Nobel Prize

Independent discovery

In 1928, Grigory Landsberg and Leonid Mandelstam at the Moscow State University independently discovered the Raman effect. They published their findings in July issue of ''Naturwissenschaften,'' and presented their findings at the Sixth Congress of the Russian Association of Physicists held at Saratov between 5 and 16 August. In 1930, they were nominated for the Nobel Prize alongside Raman. According to the Nobel Committee, however: (1) the Russians did not come to an independent interpretation of their discovery as they cited Raman's article; (2) they observed the effect only in crystals, whereas Raman and Krishnan observed it in solids, liquids and gases, and therefore proved the universal nature of the effect; (3) the problems concerning the intensity of Raman and infrared lines in the spectra had been explained during the previous year; (4) the Raman method had been applied with great success in different fields of molecular physics; and (5) the Raman effect had effectively helped to check the symmetry properties of molecules, and thus the problems concerning nuclear spin in atomic physics. The Nobel Committee proposed only Raman's name to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for the Nobel Prize. Evidence later appeared that the Russians had discovered the phenomenon earlier, a week before Raman and Krishnan's discovery. According to Mandelstam's letter (to Orest Khvolson), the Russian had observed the spectral line on 21 February 1928.Role of Krishnan

Krishnan was not nominated for the Nobel Prize even though he was the main researcher in the discovery of Raman effect. It was he alone who first noted the new scattering. Krishnan co-authored all the scientific papers on the discovery in 1928 except two. He alone wrote all the follow-up studies. Krishnan himself never claimed himself worthy of the prize. But Raman admitted later that Krishnan was the co-discoverer. He however remained openly antagonistic towards Krishnan, which the latter described as "the greatest tragedy of my life." After Krishnan's death, Raman said to a correspondent from ''The Times of India'', "Krishnan was the greatest charlatan I have known, and all his life he masqueraded in the cloak of another man's discovery."The Raman–Born controversy

During October 1933 to March 1934, Max Born was employed by IISc as Reader in Theoretical Physics following the invitation by Raman early in 1933. Born at the time was a refugee from Nazi Germany and temporarily employed at St John's College, Cambridge. Since the beginning of the 20th century Born had developed a theory on Coupled map lattice, lattice dynamics based on thermal properties. He presented his theory in one of his lectures at IISc. By then Raman had developed a different theory and claimed that Born's theory contradicted the experimental data. Their debate lasted for decades. In this dispute, Born received support from most physicists, as his view was proven to be a better explanation. Raman's theory was generally regarded as having a partial relevance. Beyond the intellectual debate, their rivalry extended to personal and social levels. Born later said that Raman probably thought of him as an "enemy." In spite of the mounting evidence for Born's theory, Raman refused to concede. As the editor of ''Current Science'' he rejected articles which supported Born's theory. Born was nominated several times for the Nobel Prize specifically for his contributions to lattice theory, and eventually won it for his statistical works on quantum mechanics in 1954. The account was written as a "belated Nobel Prize."Indian authorities

Raman had an aversion to the then Prime Minister of IndiaJawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India du ...

and Nehru's policies on science. In one instance he smashed the bust of Nehru on the floor. In another he shattered his Bharat Ratna

The Bharat Ratna (; ''Jewel of India'') is the highest Indian honours system, civilian award of the Republic of India. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is conferred in recognition of "exceptional service/performance of the highest orde ...

medallion to pieces with a hammer, as it was given to him by the Nehru government. He publicly ridiculed Nehru when the latter visited the Raman Research Institute in 1948. There they displayed a piece of gold and copper against an ultraviolet light. Nehru was tricked into believing that copper which glowed more brilliantly than any other metal was gold. Raman was quick to remark, "Mr Prime Minister, everything that glitters is not gold."

On the same occasion Nehru, offered Raman financial assistance to his institute which Raman flatly refused by replying, "I certainly don't want this to become another government laboratory." Raman was particularly against the control of research programmes by the government such as in the establishment of the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC), Defense Research and Development Organization (DRDO), and the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR). He remained hostile to people associated with these establishments including Homi J. Bhabha, S.S. Bhatnagar, and his once favourite student, Krishnan. He even called such programmes as the "Nehru–Bhatnagar effect." In 1959, Raman proposed to establish another research institute in Madras. The Government of Madras advised him to apply for funds from the central government. But Raman clearly foresaw, as he replied to C. Subramaniam, then the Minister for Finance Education in Madras, that his proposal to Nehru's government "would be met with a refusal." So ended the plan.

Raman described AICC authorities as "a big ''tamasha''" (drama or spectacle) that just kept on discussing issues without action. As to problems of food resources in India, his advice to the government was, "We must stop breeding like pigs and the matter will solve itself."

Indian Academy of Sciences

The Indian Academy of Sciences was born out of conflicts during the procedures of proposal for a national scientific organisation in line with the Royal Society. In 1933, the Indian Science Congress Association (ISCA), at the time the largest scientific organisation, planned to establish a national science body, which would be authorised to advise the government on scientific matters. Sir Richard Gregory, 1st Baronet, Sir Richard Gregory, then editor of ''Nature,'' on his visit to India had suggested Raman, as editor of ''Current Science'', to establish an Indian Academy of Sciences. Raman was of the opinion that it should be an exclusively Indian membership as opposed to the general consensus that British members should be included. He resolved that "How can India Science prosper under the tutelage of an academy which has its own council of 30, 15 of who are Britishers of whom only two or three are fit enough to be its Fellows." On 1 April 1933, he convened a separate meeting of the south Indian scientists. He and Subba Rao officially resigned from ISCA. Raman registered the new organisation as Indian Academy of Sciences on 24 April to the Registrar of Societies. It was a provisional name to be changed to the Royal Society of India after approval from the Royal Charter. The Government of India did not recognise it as an official national scientific body, as such the ICSA created a separate organisation named the National Institute of Sciences of India on 7 January 1935 (but again changed to the Indian National Science Academy in 1970). INSA had been led by the foremost rivals of Raman including Meghnad Saha, Bhabha, Bhatnagar, and Krishnan.Indian Institute of Science

Raman had a great fallout with the authorities at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc). He was accused of biased development in physics, while ignoring other fields. He lacked diplomatic personality on other colleagues, which S. Ramaseshan, his nephew and later Director of IISc, reminisced, saying, "Raman went in there like a bull in a china shop." He wanted research in physics at the level of those of western institutes, but at the expense of other fields of science. Max Born observed, "Raman found a sleepy place where very little work was being done by a number of extremely well paid people." At the Council meeting, Kenneth Aston, professor in the Electrical Technology Department, harshly criticised Raman and Raman's recruitment of Born. Raman had every intention of giving full position of professor to Born. Aston even made personal attack on Born by referring to him as someone "who was rejected by his own country, a renegade and therefore a second-rate scientist unfit to be part of the faculty, much less to be the head of the department of physics." The Council of IISc constituted a review committee to oversee Raman's conduct in January 1936. The committee, chaired by James Irvine (chemist), James Irvine, Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of St Andrews, reported in March that Raman had misused the funds and entirely shifted the "centre of gravity" towards research in physics, and also that the proposal of Born as Professor of Mathematical Physics (which was already approved by the Council in November 1935) was not financially feasible. The Council offered Raman two choices, either to resign from the institute with effect from 1 April or resign as the Director and continue as Professor of physics; if he did not make the choice, he was to be fired. Raman was inclined to take up the second choice.The Royal Society

Raman never seemed to have thought highly of the Fellowship of the Royal Society. He tendered his resignation as a Fellow on 9 March 1968, which the Council of the Royal Society accepted on 4 April. However, the exact reason was not documented. One reason could be Raman's objection to the designation "British subjects" as one of the categories of the Fellows. Particularly after the Independence of India, the Royal Society had its own disputes on this matter. According to Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, ''The London Times'' had once made a list of the Fellows, in which Raman was omitted. Raman wrote to and demanded explanation from Patrick Blackett, the then President of the society. He was dejected by Blackett's response that the society had no role in the newspaper. According to Krishnan, another cause was a disapproving review Raman received on a manuscript he had submitted to the ''Proceedings of the Royal Society''. It could have been these cumulative factors as Raman wrote in his resignation letter, and said, "I have taken this decision after careful consideration of all the circumstances of the case. I would request that my resignation be accepted and my name removed from the list of the Fellows of the Society."Honours and awards

Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemati ...

. However, he resigned from the fellowship in 1968 for unrecorded reasons, the only Indian FRS ever to do so.

He was the President of the 16th session of the Indian Science Congress Association#Indian Science Congress, Indian Science Congress in 1929. He was the founder President of the Indian Academy of Sciences from 1933 until his death. He was member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 1961.

Awards

* In 1912, Raman received the Curzon Research Award, while still working in the Indian Finance Service. *In 1913, he received the Woodburn Research Medal, while still working in the Indian Finance Service. *In 1928, he received the Matteucci Medal from the Accademia Nazionale delle Scienze in Rome. *In 1930, he was Knight Bachelor, knighted. An approval for his inclusion in the 1929 Birthday Honours was delayed, and Edward Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax, Lord Irwin, theViceroy of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

, conferred him a Knight Bachelor in a special ceremony at the Viceroy's House (now Rashtrapati Bhavan) in New Delhi.

*In 1930, he won the Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

"for his work on the scattering of light and for the discovery of the effect named after him." He was the first Asian and first non-white to receive any Nobel Prize in the sciences. Before him, Rabindranath Tagore (also Indian) had received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913.

*In 1930, he received the Hughes Medal of the Royal Society.

* In 1941, he was awarded the Franklin Medal by the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia.

* In 1954, he was awarded the Bharat Ratna

The Bharat Ratna (; ''Jewel of India'') is the highest Indian honours system, civilian award of the Republic of India. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is conferred in recognition of "exceptional service/performance of the highest orde ...

(along with politician and former Governor-General of India C. Rajagopalachari and philosopher Sir Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan).

* In 1957, he was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize.

Posthumous recognition and contemporary references

* India celebratesNational Science Day

National Science Day is celebrated in India on February 28 each year to mark the discovery of the Raman effect by Indian physicist Sir C. V. Raman on 28 February 1928.

For his discovery, Sir C.V. Raman was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics i ...

on 28 February of every year to commemorate the discovery of the Raman effect in 1928.

*Postal stamps featuring Raman were issued in 1971 and 2009.

*A road in India's capital, New Delhi, is named C. V. Raman Marg.

* An area in eastern Bangalore

Bangalore (), officially Bengaluru (), is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Karnataka. It has a population of more than and a metropolitan population of around , making it the third most populous city and fifth most ...

is called CV Raman Nagar.

*The road running north of the national seminar complex in Bangalore is named C. V. Raman Road.

* A building at the Indian Institute of Science

The Indian Institute of Science (IISc) is a public, deemed, research university for higher education and research in science, engineering, design, and management. It is located in Bengaluru, in the Indian state of Karnataka. The institute was ...

in Bangalore is named the Raman Building.

* A hospital in eastern Bangalore on 80 Ft. Rd. is named the Sir C. V. Raman Hospital.

* There is also CV Raman Nagar in Trichy, his birthplace.

*Raman (crater), Raman, a lunar crater is named after C. V. Raman.

*C. V. Raman Global University was established in 1997.

* In 1998, the American Chemical Society and Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science

Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (IACS) is a public, deemed, research university for higher education and research in basic sciences under the Department of Science & Technology, Government of India, situated at the heart of ...

recognised Raman's discovery as an National Historic Chemical Landmarks, International Historic Chemical Landmark at the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science in Jadavpur, Calcutta, India. The inscription on the commemoration plaque reads:

* Dr. C.V. Raman University was established in Chhattisgarh in 2006.

* On 7 November 2013, a Google Doodle honoured Raman on the 125th anniversary of his birthday.

*Raman Science Centre in Nagpur is named after Sir C. V. Raman.

*Dr. C.V. Raman University, Bihar was established in 2018.

*Dr. C.V. Raman University, Khandwa was established in 2018.

In popular culture