Burning of Parliament on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Palace of Westminster, the medieval royal palace used as the home of the British parliament, was largely destroyed by fire on 16 October 1834. The blaze was caused by the burning of small wooden

The Palace of Westminster, the medieval royal palace used as the home of the British parliament, was largely destroyed by fire on 16 October 1834. The blaze was caused by the burning of small wooden

The Palace of Westminster originally dates from the early eleventh century when

The Palace of Westminster originally dates from the early eleventh century when  Since medieval times the Exchequer had used

Since medieval times the Exchequer had used

This view was doubted by Sir John Hobhouse, the

This view was doubted by Sir John Hobhouse, the

The fire became the "single most depicted event in nineteenth-century London ... attracting to the scene a host of engravers, watercolourists and painters". Among them were J.M.W. Turner, the landscape painter, who later produced two pictures of the fire, and the Romantic painter John Constable, who sketched the fire from a hansom cab on Westminster Bridge.

The destruction of the standard measurements led to an overhaul of the British weights and measures system. An inquiry that ran from 1838 to 1841 considered the two competing systems used in the country, the

The fire became the "single most depicted event in nineteenth-century London ... attracting to the scene a host of engravers, watercolourists and painters". Among them were J.M.W. Turner, the landscape painter, who later produced two pictures of the fire, and the Romantic painter John Constable, who sketched the fire from a hansom cab on Westminster Bridge.

The destruction of the standard measurements led to an overhaul of the British weights and measures system. An inquiry that ran from 1838 to 1841 considered the two competing systems used in the country, the

The Palace of Westminster, the medieval royal palace used as the home of the British parliament, was largely destroyed by fire on 16 October 1834. The blaze was caused by the burning of small wooden

The Palace of Westminster, the medieval royal palace used as the home of the British parliament, was largely destroyed by fire on 16 October 1834. The blaze was caused by the burning of small wooden tally stick

A tally stick (or simply tally) was an ancient memory aid device used to record and document numbers, quantities and messages. Tally sticks first appear as animal bones carved with notches during the Upper Palaeolithic; a notable example is the ...

s which had been used as part of the accounting procedures of the Exchequer until 1826. The sticks were disposed of carelessly in the two furnaces under the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

, which caused a chimney fire in the two flues that ran under the floor of the Lords' chamber and up through the walls.

The resulting fire spread rapidly throughout the complex and developed into the largest conflagration in London between the Great Fire of 1666 and the Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

; the event attracted large crowds which included several artists who provided pictorial records of the event. The fire lasted for most of the night and destroyed a large part of the palace, including the converted St Stephen's Chapel—the meeting place of the House of Commons—the Lords Chamber, the Painted Chamber and the official residences of the Speaker

Speaker may refer to:

Society and politics

* Speaker (politics), the presiding officer in a legislative assembly

* Public speaker, one who gives a speech or lecture

* A person producing speech: the producer of a given utterance, especially:

** In ...

and the Clerk of the House of Commons

The Clerk of the House of Commons is the chief executive of the House of Commons in the Parliament of the United Kingdom, and before 1707 of the House of Commons of England.

The formal name for the position held by the Clerk of the House of C ...

.

The actions of Superintendent James Braidwood

James Braidwood (1800–1861) was a Scottish firefighter who was the first "Master of Engines", in the world's first municipal fire service in Edinburgh in 1824. He was the first director of the London Fire Engine Establishment (the brigade ...

of the London Fire Engine Establishment ensured that Westminster Hall

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

and a few other parts of the old Houses of Parliament survived the blaze. In 1836 a competition for designs for a new palace was won by Charles Barry

Sir Charles Barry (23 May 1795 – 12 May 1860) was a British architect, best known for his role in the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster (also known as the Houses of Parliament) in London during the mid-19th century, but also respon ...

. Barry's plans, developed in collaboration with Augustus Pugin

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin ( ; 1 March 181214 September 1852) was an English architect, designer, artist and critic with French and, ultimately, Swiss origins. He is principally remembered for his pioneering role in the Gothic Revival st ...

, incorporated the surviving buildings into the new complex. The competition established Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

as the predominant national architectural style and the palace has since been categorised as a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international coope ...

World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for ...

, of outstanding universal value.

Background

The Palace of Westminster originally dates from the early eleventh century when

The Palace of Westminster originally dates from the early eleventh century when Canute the Great

Cnut (; ang, Cnut cyning; non, Knútr inn ríki ; or , no, Knut den mektige, sv, Knut den Store. died 12 November 1035), also known as Cnut the Great and Canute, was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norwa ...

built his royal residence on the north side of the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

. Successive kings added to the complex: Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æt ...

built Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

; William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

began building a new palace; his son, William Rufus, continued the process, which included Westminster Hall

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

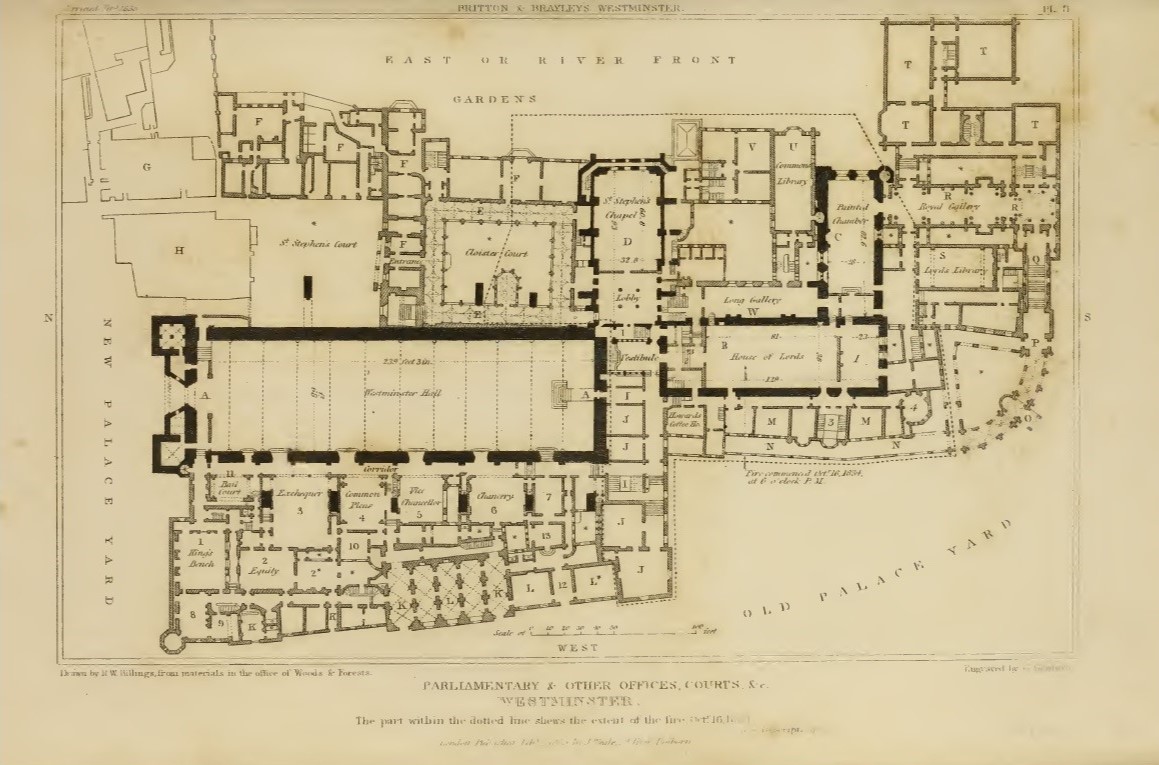

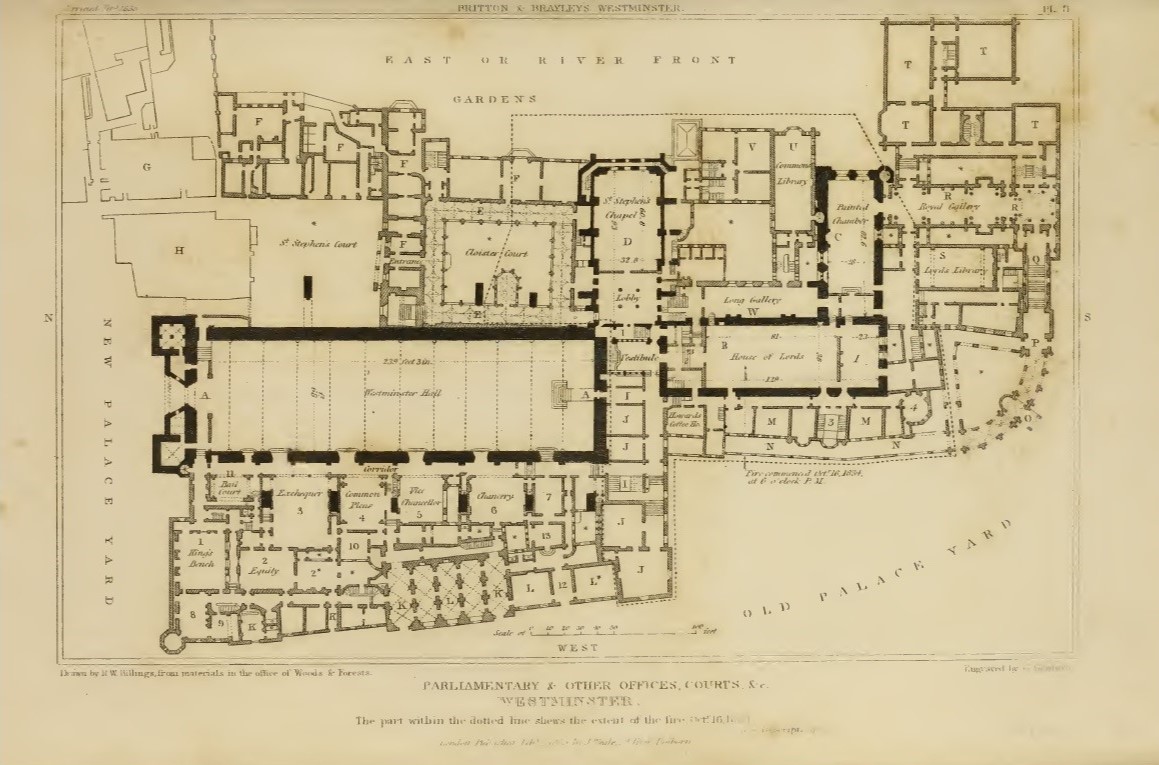

, started in 1097; Henry III built new buildings for the Exchequer—the taxation and revenue gathering department of the country—in 1270 and the Court of Common Pleas, along with the Court of King's Bench and Court of Chancery. By 1245 the King's throne was present in the palace, which signified that the building was at the centre of English royal administration.

In 1295 Westminster was the venue for the Model Parliament, the first English representative assembly, summoned by Edward I; during his reign he called sixteen parliaments, which sat either in the Painted Chamber or the White Chamber. By 1332 the barons (representing the titled classes) and burgesses and citizens (representing the commons) began to meet separately, and by 1377 the two bodies were entirely detached. In 1512 a fire destroyed part of the royal palace complex and Henry VIII moved the royal residence to the nearby Palace of Whitehall, although Westminster still retained its status as a royal palace. In 1547 Henry's son, Edward VI, provided St Stephen's Chapel for the Commons to use as their debating chamber. The House of Lords met in the medieval hall of the Queen's Chamber, before moving to the Lesser Hall in 1801. Over the three centuries from 1547 the palace was enlarged and altered, becoming a warren of wooden passages and stairways.

St Stephen's Chapel remained largely unchanged until 1692 when Sir Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 church ...

, at the time the Master of the King's Works, was instructed to make structural alterations. He lowered the roof, removed the stained glass windows, put in a new floor and covered the original gothic architecture

Gothic architecture (or pointed architecture) is an architectural style that was prevalent in Europe from the late 12th to the 16th century, during the High and Late Middle Ages, surviving into the 17th and 18th centuries in some areas. It ...

with wood panelling. He also added galleries from which the public could watch proceedings. The result was described by one visitor to the chamber as "dark, gloomy, and badly ventilated, and so small ... when an important debate occurred ... the members were really to be pitied". When the future Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-con ...

remembered his arrival as a new MP in 1832, he recounted "What I may term corporeal conveniences were ... marvellously small. I do not think that in any part of the building it afforded the means of so much as washing the hands." The facilities were so poor that, in debates in 1831 and 1834, Joseph Hume, a Radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

* Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe an ...

MP, called for new accommodation for the House, while his fellow MP William Cobbett asked "Why are we squeezed into so small a space that it is absolutely impossible that there should be calm and regular discussion, even from circumstance alone ... Why are 658 of us crammed into a space that allows each of us no more than a foot and a half square?"

By 1834 the palace complex had been further developed, firstly by John Vardy in the middle of the eighteenth century, and in the early nineteenth century by James Wyatt and Sir John Soane. Vardy added the Stone Building, in a Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

style to the West side of Westminster Hall; Wyatt enlarged the Commons, moved the Lords into the Court of Requests and rebuilt the Speaker's House. Soane, taking on responsibility for the palace complex on Wyatt's death in 1813, undertook rebuilding of Westminster Hall and constructed the Law Courts in a Neoclassical style. Soane also provided a new royal entrance, staircase and gallery, as well as committee rooms and libraries.

The potential dangers of the building were apparent to some, as no fire stops or party wall

A party wall (occasionally parti-wall or parting wall, also known as common wall or as a demising wall) is a dividing partition between two adjoining buildings that is shared by the occupants of each residence or business. Typically, the builder ...

s were present in the building to slow the progress of a fire. In the late eighteenth century a committee of MPs predicted that there would be a disaster if the palace caught fire. This was followed by a 1789 report from fourteen architects warning against the possibility of fire in the palace; signatories included Soane and Robert Adam. Soane again warned of the dangers in 1828, when he wrote that "the want of security from fire, the narrow, gloomy and unhealthy passages, and the insufficiency of the accommodations in this building are important objections which call loudly for revision and speedy amendment." His report was again ignored.

Since medieval times the Exchequer had used

Since medieval times the Exchequer had used tally stick

A tally stick (or simply tally) was an ancient memory aid device used to record and document numbers, quantities and messages. Tally sticks first appear as animal bones carved with notches during the Upper Palaeolithic; a notable example is the ...

s, pieces of carved, notched wood, normally willow, as part of their accounting procedures. The parliamentary historian Caroline Shenton has described the tally sticks as "roughly as long as the span of an index finger and thumb". These sticks were split in two so that the two sides to an agreement had a record of the situation. Once the purpose of each tally had come to an end, they were routinely destroyed. By the end of the eighteenth century the usefulness of the tally system had likewise come to an end, and a 1782 Act of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of parliame ...

stated that all records should be on paper, not tallies. The Act also abolished sinecure

A sinecure ( or ; from the Latin , 'without', and , 'care') is an office, carrying a salary or otherwise generating income, that requires or involves little or no responsibility, labour, or active service. The term originated in the medieval ch ...

positions in the Exchequer, but a clause in the act ensured it could only take effect once the remaining sinecure-holders had died or retired. The final sinecure-holder died in 1826 and the act came into force, although it took until 1834 for the antiquated procedures to be replaced. The novelist Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

, in a speech to the Administrative Reform Association, described the retention of the tallies for so long as an "obstinate adherence to an obsolete custom"; he also mocked the bureaucratic steps needed to implement change from wood to paper. He said that "all the red tape in the country grew redder at the bare mention of this bold and original conception." By the time the replacement process had finished, there were two cart-loads of old tally sticks awaiting disposal.

In October 1834 Richard Weobley, the Clerk of Works, received instructions from Treasury officials to clear the old tally sticks while parliament was adjourned. He decided against giving the sticks away to parliamentary staff to use as firewood, and instead opted to burn them in the two heating furnaces of the House of Lords, directly below the peers' chambers. The furnaces had been designed to burn coal—which gives off a high heat with little flame—and not wood, which burns with a high flame. The flues of the furnaces ran up the walls of the basement in which they were housed, under the floors of the Lords' chamber, then up through the walls and out through the chimneys.

16 October 1834

The process of destroying the tally sticks began at dawn on 16 October and continued throughout the day; two Irish labourers, Joshua Cross and Patrick Furlong, were assigned the task. Weobley checked in on the men throughout the day, claiming subsequently that, on his visits, both furnace doors were open, which allowed the two labourers to watch the flames, while the piles of sticks in both furnaces were only ever high. Another witness to the events, Richard Reynolds, the firelighter in the Lords, later reported that he had seen Cross and Furlong throwing handfuls of tallies onto the fire—an accusation they both denied. Those tending the furnaces were unaware that the heat from the fires had melted the copper lining of the flues and started a chimney fire. With the doors of the furnaces open, more oxygen was drawn into the furnaces, which ensured the fire burned more fiercely, and the flames driven farther up the flues than they should have been. The flues had been weakened over time by having footholds cut in them by the child chimney sweeps. Although these footholds would have been repaired as the child exited on finishing the cleaning, the fabric of the chimney was still weakened by the action. In October 1834 the chimneys had not yet had their annual sweep, and a considerable amount ofclinker

Clinker may refer to:

*Clinker (boat building), construction method for wooden boats

*Clinker (waste), waste from industrial processes

*Clinker (cement), a kilned then quenched cement product

* ''Clinkers'' (album), a 1978 album by saxophonist St ...

had built up inside the flues.

A strong smell of burning was present in the Lords' chambers during the afternoon of 16 October, and at 4:00 pm two gentlemen tourists visiting to see the Armada tapestries The Armada Tapestries were a series of ten tapestries that commemorated the defeat of the Spanish Armada. They were commissioned in 1591 by the Lord High Admiral, Howard of Effingham, who had commanded the Royal Navy against the Armada.Phillis Rog ...

that hung there were unable to view them properly because of the thick smoke. As they approached Black Rod's box in the corner of the room, they felt heat from the floor coming through their boots. Shortly after 4:00 pm Cross and Furlong finished work, put the last few sticks into the furnaces—closing the doors as they did so—and left to go to the nearby Star and Garter public house.

Shortly after 5:00 pm, heat and sparks from a flue ignited the woodwork above. The first flames were spotted at 6:00 pm, under the door of the House of Lords, by the wife of one of the doorkeepers; she entered the chamber to see Black Rod's box alight, and flames burning the curtains and wood panels, and raised the alarm. For 25 minutes the staff inside the palace initially panicked and then tried to deal with the blaze, but they did not call for assistance, or alert staff at the House of Commons, at the other end of the palace complex.

At 6:30 pm there was a flashover, a giant ball of flame that ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the G ...

'' reported "burst forth in the centre of the House of Lords, ... and burnt with such fury that in less than half an hour, the whole interior ... presented ... one entire mass of fire." The explosion, and the resultant burning roof, lit up the skyline, and could be seen by the royal family in Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

, away. Alerted by the flames, help arrived from nearby parish fire engines; as there were only two hand-pump engines on the scene, they were of limited use. They were joined at 6:45 pm by 100 soldiers from the Grenadier Guards

"Shamed be whoever thinks ill of it."

, colors =

, colors_label =

, march = Slow: " Scipio"

, mascot =

, equipment =

, equipment ...

, some of whom helped the police in forming a large square in front of the palace to keep the growing crowd back from the firefighters; some of the soldiers assisted the firemen in pumping the water supply from the engines.

The London Fire Engine Establishment (LFEE)—an organisation run by several insurance companies in the absence of a publicly run brigade—was alerted at about 7:00 pm, by which time the fire had spread from the House of Lords. The head of the LFEE, James Braidwood

James Braidwood (1800–1861) was a Scottish firefighter who was the first "Master of Engines", in the world's first municipal fire service in Edinburgh in 1824. He was the first director of the London Fire Engine Establishment (the brigade ...

, brought with him 12 engines and 64 firemen, even though the Palace of Westminster was a collection of uninsured government buildings, and therefore fell outside the protection of the LFEE. Some of the firefighters ran their hoses down to the Thames. The river was at low tide and it meant a poor supply of water for the engines on the river side of the building.

By the time Braidwood and his men had arrived on the scene, the House of Lords had been destroyed. A strong south-westerly breeze had fanned the flames along the wood-panelled and narrow corridors into St Stephen's Chapel. Shortly after his arrival the roof of the chapel collapsed; the resultant noise was so loud that the watching crowds thought there had been a Gunpowder Plot-style explosion. According to ''The Manchester Guardian'', "By half-past seven o'clock the engines were brought to play upon the building both from the river and the land side, but the flames had by this time acquired such a predominance that the quantity of water thrown upon them produced no visible effect." Braidwood saw it was too late to save most of the palace, so elected to focus his efforts on saving Westminster Hall, and he had his firemen cut away the part of the roof that connected the hall to the already burning Speaker's House, and then soak the hall's roof to prevent it catching fire. In doing so he saved the medieval structure at the expense of those parts of the complex already ablaze.

The glow from the burning, and the news spreading quickly round London, ensured that crowds continued to turn up in increasing numbers to watch the spectacle. Among them was a reporter for ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'', who noticed that there were "vast gangs of the light-fingered gentry in attendance, who doubtless reaped a rich harvest, and hodid not fail to commit several desperate outrages". The crowds were so thick that they blocked Westminster Bridge in their attempts to get a good view, and many took to the river in whatever craft they could find or hire in order to watch better. A crowd of thousands congregated in Parliament Square to witness the spectacle, including the Prime Minister—Lord Melbourne

William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, (15 March 177924 November 1848), in some sources called Henry William Lamb, was a British Whig politician who served as Home Secretary (1830–1834) and Prime Minister (1834 and 1835–1841). His first pr ...

—and many of his cabinet. Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, ...

, the Scottish philosopher, was one of those present that night, and he later recalled that:

This view was doubted by Sir John Hobhouse, the

This view was doubted by Sir John Hobhouse, the First Commissioner of Woods and Forests

The Commissioners of Woods, Forests and Land Revenues were established in the United Kingdom in 1810 by merging the former offices of Surveyor General of Woods, Forests, Parks, and Chases and Surveyor General of the Land Revenues of the Crown i ...

, who oversaw the upkeep of royal buildings, including the Palace of Westminster. He wrote that "the crowd behaved very well; only one man was taken up for huzzaing when the flames increased. ... on the whole, it was impossible for any large assemblage of people to behave better." Many of the MPs and peers present, including Lord Palmerston, the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, helped break down doors to rescue books and other treasures, aided by passers-by; the Deputy Serjeant-at-Arms had to break into a burning room to save the parliamentary mace.

At 9:00 pm three Guards

Guard or guards may refer to:

Professional occupations

* Bodyguard, who protects an individual from personal assault

* Crossing guard, who stops traffic so pedestrians can cross the street

* Lifeguard, who rescues people from drowning

* Prison gu ...

regiments arrived on the scene. Although the troops assisted in crowd control, their arrival was also a reaction of the authorities to fears of a possible insurrection, for which the destruction of parliament could have signalled the first step. The three European revolutions of 1830—the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, Belgian and Polish actions—were still of concern, as were the unrest from the Captain Swing riots, and the recent passing of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, which altered the relief provided by the workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

system.

At around 1:30 am the tide had risen enough to allow the LFEE's floating fire engine to arrive on the scene. Braidwood had called for the engine five hours previously, but the low tide had hampered its progress from its downriver mooring at Rotherhithe. Once it arrived it was effective in bringing under control the fire that had taken hold in the Speaker's House.

Braidwood regarded Westminster Hall as safe from destruction by 1:45 am, partly because of the actions of the floating fire engine, but also because a change in the direction of the wind kept the flames away from the Hall. Once the crowd realised that the hall was safe they began to disperse, and had left by around 3:00 am, by which time the fire near the Hall was nearly out, although it continued to burn towards the south of the complex. The firemen remained in place until about 5:00 am, when they had extinguished the last remaining flames and the police and soldiers had been replaced by new shifts.

The House of Lords, as well as its robing and committee rooms, were all destroyed, as was the Painted Chamber, and the connecting end of the Royal Gallery. The House of Commons, along with its library and committee rooms, the official residence of the Clerk of the House and the Speaker's House, were devastated. Other buildings, such as the Law Courts, were badly damaged. The buildings within the complex which emerged relatively unscathed included Westminster Hall, the cloisters and undercroft of St Stephen's, the Jewel Tower

The Jewel Tower is a 14th-century surviving element of the Palace of Westminster, in London, England. It was built between 1365 and 1366, under the direction of William of Sleaford and Henry de Yevele, to house the personal treasure of King ...

and Soane's new buildings to the south. The British standard measurements, the yard and pound, were both lost in the blaze; the measurements had been created in 1496. Also lost were most of the procedural records for the House of Commons, which dated back as far as the late 15th century. The original Acts of Parliament from 1497 survived, as did the Lords' Journals, all of which were stored in the Jewel Tower at the time of the fire. In the words of Shenton, the fire was "the most momentous blaze in London between the Great Fire of 1666 and the Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

" of the Second World War. Despite the size and ferocity of the fire, there were no deaths, although there were nine casualties during the night's events that were serious enough to require hospitalisation.

Aftermath

The day after the fire the Office of Woods and Forests issued a report outlining the damage, stating that "the strictest enquiry is in progress as to the cause of this calamity, but there is not the slightest reason to suppose that it has arisen from any other than accidental causes." ''The Times'' reported on some of the possible causes of the fire, but indicated that it was likely that the burning of the Exchequer tallies was to blame. The same day the cabinet ministers who were in London met for an emergencycabinet meeting

A cabinet is a body of high-ranking state officials, typically consisting of the executive branch's top leaders. Members of a cabinet are usually called cabinet ministers or secretaries. The function of a cabinet varies: in some countries ...

; they ordered a list of witnesses to be drawn up, and on 22 October a committee of the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

sat to investigate the fire.

The committee, which met in private, heard numerous theories as to the causes of the fire, including the lax attitude of plumbers working in the Lords, carelessness of the servants at Howard's Coffee House—situated inside the palace—and a gas explosion. Other rumours began to circulate; the Prime Minister received an anonymous letter claiming that the fire was an arson attack. The committee issued its report on 8 November, which identified the burning of the tallies as the cause of the fire. The committee thought it unlikely that Cross and Furlong had been as careful in filling the furnaces as they had claimed, and the report stated that "it is unfortunate that Mr Weobley did not more effectively superintend the burning of the tallies".

King William IV offered Buckingham Palace as a replacement to parliament; the proposal was declined by MPs who considered the building "dingy". Parliament still needed somewhere to meet, and the Lesser Hall and Painted Chamber were re-roofed and furnished for the Commons and Lords respectively for the State Opening of Parliament

The State Opening of Parliament is a ceremonial event which formally marks the beginning of a session of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It includes a speech from the throne known as the King's (or Queen's) Speech. The event takes plac ...

on 23 February 1835.

Although the architect Robert Smirke was appointed in December 1834 to design a replacement palace, pressure from the former MP Lieutenant Colonel Sir Edward Cust

Sir Edward Cust, 1st Baronet, KCH (17 March 1794 – 14 January 1878) was a British soldier, politician and courtier.

Early life

He was born in Hill Street, Berkeley Square, London, Middlesex, in 1794, the sixth son of the Brownlow Cust, 1st B ...

to open the process up to a competition gained popularity in the press and led to the formation in 1835 of a Royal Commission, which decided that although competitors would not be required to follow the outline of the original palace, the surviving buildings of Westminster Hall, the Undercroft Chapel and the Cloisters of St Stephen's would all be incorporated into the new complex.

There were 97 entries to the competition, which closed in November 1835; each entry was to be identifiable only by a pseudonym or symbol. The commission presented their recommendation in February 1836; the winning entry, which brought a prize of £1,500, was number 64, identified by a portcullis—the symbol chosen by the architect Charles Barry

Sir Charles Barry (23 May 1795 – 12 May 1860) was a British architect, best known for his role in the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster (also known as the Houses of Parliament) in London during the mid-19th century, but also respon ...

. Uninspired by any English secular Elizabethan

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personific ...

or Gothic buildings, Barry had visited Belgium to view examples of Flemish civic architecture before he drafted his design; to complete the necessary pen and ink drawings, which are now lost, he employed Augustus Pugin

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin ( ; 1 March 181214 September 1852) was an English architect, designer, artist and critic with French and, ultimately, Swiss origins. He is principally remembered for his pioneering role in the Gothic Revival st ...

, a 23-year-old architect who was, in the words of the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British art historian and architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county guides, '' The Buildings of England'' ...

, "the most fertile and passionate of the Gothicists". Thirty-four of the competitors petitioned parliament against the selection of Barry, who was a friend of Cust, but their plea was rejected, and the former prime minister Sir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850) was a British Conservative statesman who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835 and 1841–1846) simultaneously serving as Chancellor of the Excheque ...

defended Barry and the selection process.

New Palace of Westminster

Barry planned an enfilade, or what Christopher Jones, the former BBC political editor, has called "one long spine of Lords' and Commons' Chambers" which enabled the Speaker of the House of Commons to look through the line of the building to see the Queen's throne in the House of Lords. Laid out around 11 courtyards, the building included several residences with accommodation for about 200 people, and comprised a total of 1,180 rooms, 126 staircases and of corridors. Between 1836 and 1837 Pugin made more detailed drawings on which estimates were made for the palace's completion; reports of the cost estimates vary from £707,000 to £725,000, with six years until completion of the project. In June 1838 Barry and colleagues undertook a tour of Britain to locate a supply of stone for the building, eventually choosing Magnesian Limestone from theAnston

Anston is a civil parish in South Yorkshire, England, formally known as North and South Anston. The parish of Anston consists of the settlements of North Anston and South Anston, divided by the Anston Brook.

History

Anston, first recorded as ...

quarry of the Duke of Leeds

Duke of Leeds was a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1694 for the prominent statesman Thomas Osborne, 1st Marquess of Carmarthen, who had been one of the Immortal Seven in the Revolution of 1688. He had already succeeded as ...

. Work started on building the river frontage on 1 January 1839, and Barry's wife laid the foundation stone on 27 April 1840. The stone was badly quarried and handled, and with the polluted atmosphere in London it proved to be problematic, with the first signs of deterioration showing in 1849, and extensive renovations required periodically.

Although there was a setback in progress with a stonemasons' strike between September 1841 and May 1843, the House of Lords had its first sitting in the new chamber in 1847. In 1852 the Commons was finished, and both Houses sat in their new chambers for the first time; Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

first used the newly completed royal entrance. In the same year, while Barry was appointed a Knight Bachelor

The title of Knight Bachelor is the basic rank granted to a man who has been knighted by the monarch but not inducted as a member of one of the organised orders of chivalry; it is a part of the British honours system. Knights Bachelor are ...

, Pugin suffered a mental breakdown and, following incarceration at Bethlehem Pauper Hospital for the Insane, died at the age of 40.

The clock tower

Clock towers are a specific type of structure which house a turret clock and have one or more clock faces on the upper exterior walls. Many clock towers are freestanding structures but they can also adjoin or be located on top of another buildi ...

was completed in 1858, and the Victoria Tower

The Victoria Tower is a square tower at the south-west end of the Palace of Westminster in London, adjacent to Black Rod's Garden on the west and Old Palace Yard on the east. At , it is slightly taller than the Elizabeth Tower (formerly known ...

in 1860; Barry died in May that year, before the building work was completed. The final stages of the work were overseen by his son, Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

, who continued working on the building until 1870. The total cost of the building came to around £2.5 million.

Legacy

In 1836 the Royal Commission on Public Records was formed to look into the loss of the parliamentary records, and make recommendations on the preservation of future archives. Their published recommendations in 1837 led to the Public Record Act (1838), which set up the Public Record Office, initially based in Chancery Lane. The fire became the "single most depicted event in nineteenth-century London ... attracting to the scene a host of engravers, watercolourists and painters". Among them were J.M.W. Turner, the landscape painter, who later produced two pictures of the fire, and the Romantic painter John Constable, who sketched the fire from a hansom cab on Westminster Bridge.

The destruction of the standard measurements led to an overhaul of the British weights and measures system. An inquiry that ran from 1838 to 1841 considered the two competing systems used in the country, the

The fire became the "single most depicted event in nineteenth-century London ... attracting to the scene a host of engravers, watercolourists and painters". Among them were J.M.W. Turner, the landscape painter, who later produced two pictures of the fire, and the Romantic painter John Constable, who sketched the fire from a hansom cab on Westminster Bridge.

The destruction of the standard measurements led to an overhaul of the British weights and measures system. An inquiry that ran from 1838 to 1841 considered the two competing systems used in the country, the avoirdupois

The avoirdupois system (; abbreviated avdp.) is a measurement system of weights that uses pounds and ounces as units. It was first commonly used in the 13th century AD and was updated in 1959.

In 1959, by international agreement, the defini ...

and troy

Troy ( el, Τροία and Latin: Troia, Hittite: 𒋫𒊒𒄿𒊭 ''Truwiša'') or Ilion ( el, Ίλιον and Latin: Ilium, Hittite: 𒃾𒇻𒊭 ''Wiluša'') was an ancient city located at Hisarlik in present-day Turkey, south-west of Ç ...

measures, and decided that avoirdupois would be used forthwith; troy weights were retained solely for gold, silver and precious stones. The destroyed weights and measures were recast by William Simms, the scientific instrument maker, who produced the replacements after "countless hours of tests and experiments to determine the best metal, the best shape of bar, and the corrections for temperature".

The Palace of Westminster has been a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international coope ...

World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for ...

since 1987, and is classified as being of outstanding universal value. UNESCO describe the site as being "of great historic and symbolic significance", in part because it is "one of the most significant monuments of neo-Gothic architecture, as an outstanding, coherent and complete example of neo-Gothic style". The decision to use the Gothic design for the palace set the national style, even for secular buildings.

In 2015 the chairman of the House of Commons Commission, John Thurso

John Archibald Sinclair, 3rd Viscount Thurso (born 10 September 1953), known also as John Thurso, is a Scottish businessman, Liberal Democrat politician and hereditary peer who is notable for having served in the House of Lords both before and ...

, stated that the palace was in a "dire condition". The Speaker of the House of Commons, John Bercow, agreed and said that the building was in need of extensive repairs. He reported that parliament "suffers from flooding, contains a great deal of asbestos and has fire safety issues", which would cost £3 billion to fix.

Notes and references

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Parliament, Burning of 1834 fires in Europe 1834 in London Fires at legislative buildings Palace of Westminster Political history of London Building and structure fires in London October 1834 events 1834 disasters in the United Kingdom