Burma National Army on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Burma Independence Army (BIA), was a

The Burma Independence Army (BIA), was a

In 1940, the Japanese military interest in Southeast Asia had increased, the British were overtly providing military assistance to Nationalist China against which Japan was fighting in the

In 1940, the Japanese military interest in Southeast Asia had increased, the British were overtly providing military assistance to Nationalist China against which Japan was fighting in the  Suzuki and Aung San flew to

Suzuki and Aung San flew to

On 7 December 1941, Japan attacked the

On 7 December 1941, Japan attacked the

One action in which the BIA played a major part was at Shwedaung, near

One action in which the BIA played a major part was at Shwedaung, near

As the invasion speedily continued in Japan's favour, more and more territory fell into Japanese hands who disregarded the agreement for Burma's independence. As the BIA's ranks had swelled with thousands of unorganised army and volunteers, with plenty of weapons spread throughout the country which led to widespread chaos, looting and killings were common. The Japanese army command formed an administration on their own terms and the commanders of the Fifteenth Army began undermining the creation of a Burmese government. Thakin Tun Oke had been selected to be the political administrator and government organiser. BIA attempted to form local governments in Burma. Attempts over the administration of Moulmein, the Japanese 55th Division had flatly refused Burmese requests and even forbade them to enter the town. Many in the BIA considered the Japanese suppression of them to be based on notions of racial superiority. However, the BIA's attempts at creating a government were dared by Colonel Suzuki, who said to

As the invasion speedily continued in Japan's favour, more and more territory fell into Japanese hands who disregarded the agreement for Burma's independence. As the BIA's ranks had swelled with thousands of unorganised army and volunteers, with plenty of weapons spread throughout the country which led to widespread chaos, looting and killings were common. The Japanese army command formed an administration on their own terms and the commanders of the Fifteenth Army began undermining the creation of a Burmese government. Thakin Tun Oke had been selected to be the political administrator and government organiser. BIA attempted to form local governments in Burma. Attempts over the administration of Moulmein, the Japanese 55th Division had flatly refused Burmese requests and even forbade them to enter the town. Many in the BIA considered the Japanese suppression of them to be based on notions of racial superiority. However, the BIA's attempts at creating a government were dared by Colonel Suzuki, who said to

After a year of occupation, on 1 August 1943, the newly created

After a year of occupation, on 1 August 1943, the newly created  Although Burma was nominally self-governing, the power of the State of Burma to exercise its sovereignty was largely circumscribed by wartime agreements with Japan. The

Although Burma was nominally self-governing, the power of the State of Burma to exercise its sovereignty was largely circumscribed by wartime agreements with Japan. The

The Japanese were routed from most of Burma by May 1945. Negotiations then began with the British over the disarming of the AFO, which earlier in March the same year had been transformed into a united front comprising the Patriotic Burmese Forces,

The Japanese were routed from most of Burma by May 1945. Negotiations then began with the British over the disarming of the AFO, which earlier in March the same year had been transformed into a united front comprising the Patriotic Burmese Forces,  When the British noticed with alarm that PBF troops were withholding weapons, ready to go underground, tense negotiations in a conference in

When the British noticed with alarm that PBF troops were withholding weapons, ready to go underground, tense negotiations in a conference in

The Burma Independence Army (BIA), was a

The Burma Independence Army (BIA), was a collaborationist

Wartime collaboration is cooperation with the enemy against one's country of citizenship in wartime, and in the words of historian Gerhard Hirschfeld, "is as old as war and the occupation of foreign territory".

The term ''collaborator'' dates to ...

and revolutionary army that fought for the end of British rule in Burma

( Burmese)

, conventional_long_name = Colony of Burma

, common_name = Burma

, era = Colonial era

, event_start = First Anglo-Burmese War

, year_start = 1824

, date_start = ...

by assisting the Japanese in their conquest of the country in 1942 during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. It was the first post-colonial army in Burmese history. The BIA was formed from group known as the Thirty Comrades under the auspices of the Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emper ...

after training the Burmese nationalists in 1941. The BIA's attempts at establishing a government during the invasion led to it being dissolved by the Japanese and the smaller Burma Defence Army (BDA) formed in its place. As Japan guided Burma towards nominal independence, the BDA was expanded into the Burma National Army (BNA) of the State of Burma

The State of Burma (; ja, ビルマ国, ''Biruma-koku'') was a Japanese puppet state created by Japan in 1943 during the Japanese occupation of Burma in World War II.

Background

During the early stages of World War II, the Empire of Japan in ...

, a puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

under Ba Maw

Ba Maw ( my, ဘမော်, ; 8 February 1893 – 29 May 1977) was a Burmese lawyer and political leader, active during the interwar and World War II periods. Dr. Ba Maw is a descendant of the Mon Dynasty. He was the first Burma Premier ...

, in 1943.Donald M. Seekins, ''Historical Dictionary of Burma (Myanmar)'' (Scarecrow Press, 2006), 123–26 and 354.

After secret contact with the British during 1944, on 27 March 1945, the BNA revolted against the Japanese. The army received recognition as an ally from Supreme Allied Commander, Lord Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of German ...

, who needed their assistance against retreating Japanese forces and to ease the strain between the army's leadership and the British. As part of the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League

The Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League (AFPFL), ; abbreviated , ''hpa hsa pa la'' was the dominant political alliance in Burma from 1945 to 1958. It consisted of political parties and mass and class organizations.

The league evolved out of ...

, the BNA was re-labelled the Patriotic Burmese Forces (PBF) during a joint Allied–Burmese victory parade in Rangoon on 23 June 1945. Following the war, after tense negotiations, it was decided that the PBF would be integrated into a new Burma Army under British control, but many veterans would continue under old leadership in the paramilitary People's Volunteer Organisation (PVO) in the unstable situation of post-war Burma.

Background of Burma

British rule in Burma

( Burmese)

, conventional_long_name = Colony of Burma

, common_name = Burma

, era = Colonial era

, event_start = First Anglo-Burmese War

, year_start = 1824

, date_start = ...

began in 1824 after which the British steadily tightened its grip on the country and implemented significant changes to Burmese government and economy compared to Burma under the Konbaung dynasty before. The British removed and exiled King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

Thibaw Min

Thibaw Min, also Thebaw or Theebaw ( my, သီပေါမင်း, ; 1 January 1859 – 19 December 1916) was the last king of the Konbaung dynasty of Burma (Myanmar) and also the last Burmese monarch in the country's history. His r ...

and separated government from the Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

Sangha

Sangha is a Sanskrit word used in many Indian languages, including Pali meaning "association", "assembly", "company" or "community"; Sangha is often used as a surname across these languages. It was historically used in a political context t ...

, with large consequences in the dynamics of Burmese society and was particularly devastating to Buddhist monks who were dependent on the sponsorship of the monarchy. British control increased over time, for example, in 1885 under the Colonial Village Act, all Burmese, except for Buddhist monks, were required to ''Shikko'' (a greeting hitherto used only for important elders, monks and the Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in L ...

) to British officials. These greetings would demonstrate Burmese submission and respect to British rule. In addition, the act stated that villages would provide lodging and food upon the arrival of colonial military or civil officials. Lastly, against mounting rebellions, the British adopted a “strategic hamlet” strategy, whereby villages were burned and uprooted families who had supplied villages with Headmen, sending them to lower Burma

Lower Myanmar ( my, အောက်မြန်မာပြည်, also called Lower Burma) is a geographic region of Myanmar and includes the low-lying Irrawaddy Delta ( Ayeyarwady, Bago and Yangon Regions), as well as coastal regions of the c ...

and replacing them with British approved appointees.

Future changes to Burma included the establishment of land titles, payment of taxes to the British, records of births and deaths and the introduction of census that included personal information, including information pertaining to jobs and religion. The census was especially hard on Burmese identity due to the variation of names and the habit of villagers to move between various families. These traditions

A tradition is a belief or behavior (folk custom) passed down within a group or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common examples include holidays o ...

were very different from Western culture

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

and not compatible with the British imposed census. British insistence upon western medicine and inoculation

Inoculation is the act of implanting a pathogen or other microorganism. It may refer to methods of artificially inducing immunity against various infectious diseases, or it may be used to describe the spreading of disease, as in "self-inoculati ...

was particularly distasteful to native residents of Burma. These changes led to a greater distrust of the British and in turn harsher mandates as they became aware of Burmese resistance.

A major issue in the early 1900s was land alienation by Indian Chettiar

Chettiar (also spelt as Chetti and Chetty)is a title used by many traders, weaving, agricultural and land-owning castes in South India, especially in the states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka.

They are a subgroup of the Tamil community ...

moneylenders who were taking advantage of the economic situation in the villages. At the same time, thousands of Indian labourers migrated to Burma and, because of their willingness to work for less money, quickly displaced Burmese farmers, who instead began to take part in crime. All this, combined with Burma's exclusion from British proposals for limited self-government in Indian provinces (of which Burma was part of at the time), led to one of the earliest political nationalist groups, the General Council of Burmese Associations

The General Council of Burmese Associations (GCBA), also known as the Great Burma Organisation ( my, မြန်မာအသင်းချုပ်ကြီး; ''Myanma Ahthinchokgyi''), was a political party in Burma.

History

The GCBA was for ...

, who had split off from the apolitical Young Men's Buddhist Association. Foreign goods were boycotted and the association set up village courts and rejected the British courts of law claiming that a fair trial had a better chance under the control of Burmese people. Student protests, backed by the Buddhist clergy, also led to "National schools" being created in protest against the colonial education system. As a result the British to imposed restrictions on free speech and an increase of the police force.

Hsaya Rebellion

The first major organised armed rebellion occurred between 1930 and 1932 and was called The Hsaya Rebellion. The former monk Hsaya San sparked a rebellion by mobilising peasants in rural Burma after protests against taxes and British disrespect towards Buddhism. The Burmese colonial army under British rule included only minorities such as theKaren

Karen may refer to:

* Karen (name), a given name and surname

* Karen (slang), a term and meme for a demanding woman displaying certain behaviors

People

* Karen people, an ethnic group in Myanmar and Thailand

** Karen languages or Karenic la ...

, Chin

The chin is the forward pointed part of the anterior mandible ( mental region) below the lower lip. A fully developed human skull has a chin of between 0.7 cm and 1.1 cm.

Evolution

The presence of a well-developed chin is considered to be one ...

and Kachin and isolated the majority Bamar

The Bamar (, ; also known as the Burmans) are a Sino-Tibetan ethnic group native to Myanmar (formerly Burma) in Southeast Asia. With approximately 35 million people, the Bamar make up the largest ethnic group in Myanmar, constituting 68% of th ...

population. As more people joined the rebellion it evolved into a nationwide revolt which only ended after Hsaya San was captured after two years of insurrection. He and many other rebel leaders were executed and imprisoned after the rebellion was put down. The Hsaya rebellion sparked a large emergence of organised anti-colonial politics in Burma during the 1930s.

Aung San and Japan

Aung San

Aung San (, ; 13 February 191519 July 1947) was a Burmese politician, independence activist and revolutionary. He was instrumental in Myanmar's struggle for independence from British rule, but he was assassinated just six months before his goa ...

was a nationalist student activist working for the cause of an independent Burma. While at university, he became an influential political leader and created a new platform for educated nationalistic students who were intent upon a Burmese Independent state. In 1938 he joined the radical, anti-colonial Dohbama Asiayone party (known as the ''Thakins

Dobama Asiayone ( my, တို့ဗမာအစည်းအရုံး, ''Dóbăma Ăsì-Ăyòun'', meaning ''We Burmans Association'', DAA), commonly known as the Thakhins ( my, သခင် ''sa.hkang'', lit. Lords), was a Burmese national ...

''). After the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, the Thakins, combined with the Poor Man's Party

The Poor Man's Party ( my, ဆင်းရဲသား ဝံသာနု အဖွဲ့; also known as the Sinyetha, or Proletarian) was a political party in Burma led by Ba Maw.

History

The party was formed in 1935 in order to contest the 19 ...

to create the Freedom Bloc

The Freedom Bloc, later known as Dobama-Sinyetha Asiayone, was a political party in Burma during World War II.

History

The party was established by a merger of Dobama Asiayone (DAA), Ba Maw

Ba Maw ( my, ဘမော်, ; 8 February 1893 & ...

, which opposed cooperation with the British war effort unless Burma was guaranteed independence immediately after the war and threatened to increase its anti-British and anti-war campaign. The British denied the Freedom Bloc's demands and much of its leadership was imprisoned until after the Japanese invasion in 1942. The Thakins looked elsewhere for support and planned on setting up ties with the Chinese communists. Aung San flew to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

in 1940, intent to make contact with them in order to discuss investments into an independent Burmese Army.

In 1940, the Japanese military interest in Southeast Asia had increased, the British were overtly providing military assistance to Nationalist China against which Japan was fighting in the

In 1940, the Japanese military interest in Southeast Asia had increased, the British were overtly providing military assistance to Nationalist China against which Japan was fighting in the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific T ...

. In particular, they were sending war materials via the newly opened Burma Road

The Burma Road () was a road linking Burma (now known as Myanmar) with southwest China. Its terminals were Kunming, Yunnan, and Lashio, Burma. It was built while Burma was a British colony to convey supplies to China during the Second S ...

. Colonel Keiji Suzuki

is a Japanese judoka.

He won the Olympic gold medal in the heavyweight (+100 kg) division in 2004. He is also a two-time world champion.

He is noted for being a remarkably small judoka in the heavyweight division; he also regularly comp ...

, a staff officer at the Imperial General Headquarters

The was part of the Supreme War Council and was established in 1893 to coordinate efforts between the Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy during wartime. In terms of function, it was approximately equivalent to the United States ...

in Japan, was given the task of devising a strategy for dealing with Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

and he produced a plan for clandestine operations in Burma. The Japanese knew little about Burma at the time and had few contacts within the country. The top Japanese agent in the country was Naval Reservist Kokubu Shozo, who had been resident there for several years and had contacts with most of the anti-British political groups. Suzuki visited Burma secretly, posing as a journalist for the ''Yomiuri Shimbun

The (lit. ''Reading-selling Newspaper'' or ''Selling by Reading Newspaper'') is a Japanese newspaper published in Tokyo, Osaka, Fukuoka, and other major Japanese cities. It is one of the five major newspapers in Japan; the other four are ...

'' under the name ''Masuyo Minami'', in September 1940, meeting with political leaders Thakin Kodaw Hmaing and Thakin Mya

Dobama Asiayone ( my, တို့ဗမာအစည်းအရုံး, ''Dóbăma Ăsì-Ăyòun'', meaning ''We Burmans Association'', DAA), commonly known as the Thakhins ( my, သခင် ''sa.hkang'', lit. Lords), was a Burmese national ...

. The Japanese later made contact with Aung San in China who had reached Amoy

Xiamen ( , ; ), also known as Amoy (, from Hokkien pronunciation ), is a sub-provincial city in southeastern Fujian, People's Republic of China, beside the Taiwan Strait. It is divided into six districts: Huli, Siming, Jimei, Tong' ...

when he was detained by Suzuki.

Suzuki and Aung San flew to

Suzuki and Aung San flew to Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.46 ...

. After discussions at the Imperial General Headquarters, it was decided in February 1941 to form an organisation named ''Minami Kikan'', which was to support Burmese resistance groups and to close the Burma Road to China. In pursuing those goals, it would recruit potential independence fighters in Burma and train them in Japans ally Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

or Japanese occupied China. Aung San and 29 others, the future officers and core of the Burma Independence Army, known as the Thirty Comrades, left Burma in April 1941 and were trained on Hainan Island

Hainan (, ; ) is the smallest and southernmost province of the People's Republic of China (PRC), consisting of various islands in the South China Sea. , the largest and most populous island in China,The island of Taiwan, which is slight ...

in leadership, espionage, guerrilla warfare and political tactics. Colonel Suzuki assumed the Burmese name "Bo Mo Gyo" (''Commander Thunderbolt''), for his work with Minami Kikan.

Formation and action of the Burma Independence Army

On 7 December 1941, Japan attacked the

On 7 December 1941, Japan attacked the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

and Britain. On 28 December, at a ceremony in Bangkok

Bangkok, officially known in Thai as Krung Thep Maha Nakhon and colloquially as Krung Thep, is the capital and most populous city of Thailand. The city occupies in the Chao Phraya River delta in central Thailand and has an estimated populati ...

, the Burma Independence Army (BIA) was officially formed. The Thirty Comrades, as well as Colonel Suzuki, had their blood drawn from their arms in syringes, then poured into a silver bowl and mixed with liquor from which each of them drank – ''thway thauk'' in time-honoured Burmese military tradition – pledging "eternal loyalty" among themselves and to the cause of Burmese independence. The BIA initially numbered 227 Burmese and 74 Japanese. Some of the Burmese soldiers were second-generation residents in Thailand, who could not speak Burmese.Bayly and Harper, p.170

The BIA formed was broken into six units which were assigned to participate in the invasion of Burma in January 1942, initially as intelligence-gatherers, saboteurs and foragers. The leader of the Burma Independence Army were declared with Keiji Suzuki as Commander-in-Chief, with Aung San as ''Senior Staff Officer''. When the army entered into Burma it was made up of 2,300 men and organised in the following way.

As the Japanese and the BIA entered Burma, the BIA gained a lot of support from the civilian population and were bolstered by many Bamar

The Bamar (, ; also known as the Burmans) are a Sino-Tibetan ethnic group native to Myanmar (formerly Burma) in Southeast Asia. With approximately 35 million people, the Bamar make up the largest ethnic group in Myanmar, constituting 68% of th ...

volunteers. This caused their numbers to grow to such a level that by the time the Japanese forces reached Rangoon

Yangon ( my, ရန်ကုန်; ; ), formerly spelled as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar (also known as Burma). Yangon served as the capital of Myanmar until 2006, when the military government ...

on 8 March, the BIA numbered 10,000-12,000, and eventually expanded to between 18,000 and 23,000. Many of the volunteers who joined the BIA were however not officially recruited, but rather officials or even criminal gangs who took to calling themselves BIA to further their own activities. The Japanese provided few weapons to the BIA, but they armed themselves from abandoned or captured British weapons. With the help of a propaganda campaign from the BIA, Suzuki was welcomed by the Burmese people since word was spread that "''Bo Mo Gyo''" (Suzuki) was a decedent of the Prince of Myingun, a Burmese prince in the direct line of succession to the Burmese throne who had been exiled after a failed rebellion to Saigon

, population_density_km2 = 4,292

, population_density_metro_km2 = 697.2

, population_demonym = Saigonese

, blank_name = GRP (Nominal)

, blank_info = 2019

, blank1_name = – Total

, blank1_ ...

, where he died in 1923. Propaganda claiming that Bo Mo Gyo was to lead the resistance into restoring the throne soon spread throughout Burma, which helped to provide a format for the Burmese villagers to accept the involvement of Japanese help in overthrowing the British.

Throughout the invasion, the swelling numbers of the BIA were involved in attacks on minority populations (particularly the Karens) and preyed on Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

refugees fleeing from the Japanese. The worst atrocities against the Karens in the Irrawaddy Delta

The Irrawaddy Delta or Ayeyarwady Delta lies in the Irrawaddy Division, the lowest expanse of land in Myanmar that fans out from the limit of tidal influence at Myan Aung to the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea, to the south at the mouth of the ...

south of Rangoon cannot however be attributed to dacoits

Dacoity is a term used for "banditry" in the Indian subcontinent. The spelling is the anglicised version of the Hindi word ''daaku''; "dacoit" is a colloquial Indian English word with this meaning and it appears in the ''Glossary of Colloquial ...

or unorganised recruits, but rather the actions of a subset of regular BIA and their Japanese officers. Elements of the BIA in Irrawaddy destroyed 400 Karen villages with a death toll reaching 1,800. In one instance, which was also described in Kyaw Zaw's, one of the Thirty Comrades, memoirs, Colonel Suzuki personally ordered the BIA to destroy two large Karen villages and killing all within as an act of retribution after one of his officers was killed in an attack by anti-Japanese resistance.

Battle of Shwedaung

One action in which the BIA played a major part was at Shwedaung, near

One action in which the BIA played a major part was at Shwedaung, near Prome

Pyay (, ; mnw, ပြန် , ; also known as Prome and Pyè) is principal town of Pyay Township in the Bago Region in Myanmar. Pyay is located on the bank of the Irrawaddy River, north-west of Yangon. It is an important trade center for the Aye ...

, in Southern Burma. On 29 March 1942, a detachment from the British 7th Armoured Brigade commanded by Brigadier John Henry Anstice was retreating from nearby Paungde. Another detachment of two Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

battalions was sent to clear Shwedaung, which lay on Anstice's line of retreat and was held by the II Battalion of the Japanese 215th Regiment, commanded by Major Misao Sato, and 1,300 men belonging to the BIA under Bo Yan Naing, one of the Thirty Comrades. Two Japanese liaison officers named Hirayama and Ikeda accompanied the BIA. With Anstice's force and the Indian troops attacking Shwedaung from two sides, the roadblocks were soon cleared, but a lucky shot from a Japanese anti-tank gun knocked out a tank on a vital bridge and forced the British to retreat across open fields where Bo Yan Naing ambushed them with 400 men. Eventually the British and Indian force broke free and continued their retreat, having lost ten tanks, two field guns and 350 men killed or wounded. The BIA's casualties were heavy; 60 killed, 300 wounded, 60 captured and 350 missing, who had deserted. Hirayama and Ikeda were both killed. Most of the BIA's casualties resulted from inexperience and lack of equipment. Though Burmese political leader Ba Maw

Ba Maw ( my, ဘမော်, ; 8 February 1893 – 29 May 1977) was a Burmese lawyer and political leader, active during the interwar and World War II periods. Dr. Ba Maw is a descendant of the Mon Dynasty. He was the first Burma Premier ...

and others later eulogised the BIA's participation in the battle, the official Japanese history never mentioned them.

Tension between the Japanese and BIA

As the invasion speedily continued in Japan's favour, more and more territory fell into Japanese hands who disregarded the agreement for Burma's independence. As the BIA's ranks had swelled with thousands of unorganised army and volunteers, with plenty of weapons spread throughout the country which led to widespread chaos, looting and killings were common. The Japanese army command formed an administration on their own terms and the commanders of the Fifteenth Army began undermining the creation of a Burmese government. Thakin Tun Oke had been selected to be the political administrator and government organiser. BIA attempted to form local governments in Burma. Attempts over the administration of Moulmein, the Japanese 55th Division had flatly refused Burmese requests and even forbade them to enter the town. Many in the BIA considered the Japanese suppression of them to be based on notions of racial superiority. However, the BIA's attempts at creating a government were dared by Colonel Suzuki, who said to

As the invasion speedily continued in Japan's favour, more and more territory fell into Japanese hands who disregarded the agreement for Burma's independence. As the BIA's ranks had swelled with thousands of unorganised army and volunteers, with plenty of weapons spread throughout the country which led to widespread chaos, looting and killings were common. The Japanese army command formed an administration on their own terms and the commanders of the Fifteenth Army began undermining the creation of a Burmese government. Thakin Tun Oke had been selected to be the political administrator and government organiser. BIA attempted to form local governments in Burma. Attempts over the administration of Moulmein, the Japanese 55th Division had flatly refused Burmese requests and even forbade them to enter the town. Many in the BIA considered the Japanese suppression of them to be based on notions of racial superiority. However, the BIA's attempts at creating a government were dared by Colonel Suzuki, who said to U Nu

Nu ( my, ဦးနု; ; 25 May 1907 – 14 February 1995), commonly known as U Nu also known by the honorific name Thakin Nu, was a leading Burmese statesman and nationalist politician. He was the first Prime Minister of Burma under the pr ...

that:"Independence is not the kind of thing you can get by begging for it from other people. You should proclaim it yourselves. The Japanese refuse to give it? Very well then, tell them that you will cross over to someplace like Twante and proclaim it and set up your government. What's the difficulty about that? If they start shooting, you shoot back."Aung San tried to establish a training school in

Bhamo

Bhamo ( my, ဗန်းမော်မြို့ ''ban: mau mrui.'', also spelt Banmaw; shn, မၢၼ်ႈမူဝ်ႇ; tdd, ᥛᥫᥒᥰ ᥛᥨᥝᥱ; zh, 新街, Hsinkai) is a city in Kachin State in northern Myanmar, south of the ...

. His efforts were too late and interrupted by the Kempeitai. After the Japanese invasion of Burma the Japanese Commander of the 15th Army, Lieutenant-General Shōjirō Iida, recalled Suzuki to Japan. In its place the Japanese created civil organisations designed to guide Burma toward puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

. the BIA was disarmed and disbanded on 24 July. Now the Burma Defence Army (BDA), placed under the command of Colonel Aung San with Bo Let Ya as Chief of Staff, lead by several Japanese commanders. An officers' training school was established in Mingaladon and the new force of 3,000 men were recruited and trained by Japanese instructors as regular army battalions instead of a guerrilla force during the second half of 1942. After the change in leadership, Aung Sun tried to push for what he considered the true mission of the army, which was not just a military group composed of the Thakins, but an army of "true patriots irrespective of political creed or race and dedicated to national independence".

Transition into the Burma National Army

State of Burma

The State of Burma (; ja, ビルマ国, ''Biruma-koku'') was a Japanese puppet state created by Japan in 1943 during the Japanese occupation of Burma in World War II.

Background

During the early stages of World War II, the Empire of Japan in ...

was granted nominal independence by Japan and became a member of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a concept that was developed in the Empire of Japan and propagated to Asian populations which were occupied by it from 1931 to 1945, and which officially aimed at creating a self-sufficient bloc of Asian peo ...

. Its Head of State became Dr. Ba Maw

Ba Maw ( my, ဘမော်, ; 8 February 1893 – 29 May 1977) was a Burmese lawyer and political leader, active during the interwar and World War II periods. Dr. Ba Maw is a descendant of the Mon Dynasty. He was the first Burma Premier ...

, an outspoken anti-colonial politician imprisoned by the British before the war. Aung San became Minister of Defence in the new regime, with the new rank of Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

and Bo Let Ya as his Deputy. Bo Ne Win (who would much later become the dictator of Burma after World War II) became Commander-in-Chief of the expanded Burma National Army (BNA). The BNA eventually consisted of seven battalions of infantry and a variety of supporting units with a strength which grew to around 11,000-15,000 men. Most were from the majority Bamar

The Bamar (, ; also known as the Burmans) are a Sino-Tibetan ethnic group native to Myanmar (formerly Burma) in Southeast Asia. With approximately 35 million people, the Bamar make up the largest ethnic group in Myanmar, constituting 68% of th ...

population, but there was one battalion raised from the Karen

Karen may refer to:

* Karen (name), a given name and surname

* Karen (slang), a term and meme for a demanding woman displaying certain behaviors

People

* Karen people, an ethnic group in Myanmar and Thailand

** Karen languages or Karenic la ...

minority.

Although Burma was nominally self-governing, the power of the State of Burma to exercise its sovereignty was largely circumscribed by wartime agreements with Japan. The

Although Burma was nominally self-governing, the power of the State of Burma to exercise its sovereignty was largely circumscribed by wartime agreements with Japan. The Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emper ...

maintained a large presence and continued to act arbitrarily, despite Japan no longer having official control over Burma. The resulting hardships and Japanese militaristic attitudes turned the majority Burman population against the Japanese. The insensitive attitude of the Japanese Army extended to the BNA. Even the officers of the BNA were obliged to salute low-ranking privates of the Imperial Japanese Army as their superiors. Aung San soon became disillusioned about Japanese promises of true independence and of Japan's ability to win the war. As the British General in the Burma Campaign William Slim put it: "It was not long before Aung San found that what he meant by independence had little relation to what the Japanese were prepared to give—that he had exchanged an old master for an infinitely more tyrannical new one. As one of his leading followers once said to me, "If the British sucked our blood, the Japanese ground our bones!"Field Marshal Sir William Slim, ''Defeat into Victory ''Defeat into Victory'' is an account of the retaking of Burma by Allied forces during the Second World War by the British Field Marshal William Slim, 1st Viscount Slim, and published in the UK by Cassell in 1956. It was published in the Unite ...'', Cassell & Company, 2nd edition, 1956

Change of sides

During 1944, the BNA made contacts with other political groups inside Burma, such as the communists who had taken to the hills in the initial invasion. In August 1944, a popular front organisation called the Anti-Fascist Organisation (AFO) was formed withThakin Soe

Thakin Soe ( my, သခင်စိုး, ; 1906 – 6 May 1989) was a founding member of the Communist Party of Burma, formed in 1939 and a leader of Anti-Fascist Organisation. He is regarded as one of Burma's most prominent communist leaders. ...

, a founding member of the Communist Party of Burma

The Communist Party of Burma (CPB), also known as the Burma Communist Party (BCP), is a clandestine communist party in Myanmar (Burma). It is the oldest existing political party in the country.

Founded in 1939, the CPB initially fought a ...

, as leader. Through the communists, Aung San were eventually able to make contact with the British Force 136

Force 136 was a far eastern branch of the British World War II intelligence organisation, the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Originally set up in 1941 as the India Mission with the cover name of GSI(k), it absorbed what was left of SOE's Or ...

in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

. The initial contacts were always indirect. Force 136 was also able to make contacts with members of the BNA's Karen unit in Rangoon through agents dropped by parachute into the Karenni State, the Karen-populated area in the east of Burma. In December 1944, the AFO contacted the Allies indicating their readiness to launch a national uprising which would include the BNA. The situation was not immediately considered favourable by the British for a revolt by the BNA and there were internal disputes about supporting the BNA among them; the British had reservations over dealing with Aung San. In contrast to Force 136, Civil Affair officers of Lord Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of German ...

in the South East Asia Command (SEAC) wanted him tried for war crimes, including a 1942 murder case in which he had personally executed a civilian, the Headman of Thebyugone village, in front of a large crowd. General William Slim later wrote: "I would accept ung San'shelp and that of his army only on the clear understanding that it implied no recognition of any provisional government. ... The British Government had announced its intention to grant self-government to Burma within the British Commonwealth, and we had better limit our discussion to the best method of throwing the Japanese out of the country as the next step toward self-government."In late March 1945, the BNA paraded in Rangoon and marched out ostensibly to take part in the battles then raging in Central Burma. Instead, on 27 March, they openly declared war on the Japanese and rose up in a country-wide rebellion. BNA units were deployed all over the country under ten different regional commands (see table below). Those near the British front-lines around the

Irrawaddy River

The Irrawaddy River ( Ayeyarwady River; , , from Indic ''revatī'', meaning "abounding in riches") is a river that flows from north to south through Myanmar (Burma). It is the country's largest river and most important commercial waterway. Orig ...

requested arms and supplies from Allied units operating in this area. They also seized control of the civil institutions in most of the main towns. Aung San and others subsequently began negotiations with Mountbatten and officially joined the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

as the Patriotic Burmese Forces (PBF) in 23 June 1945. At the first meeting, the AFO represented itself to the British as the provisional government of Burma with Thakin Soe as Chairman and Aung San as a member of its ruling committee.

Aftermath

The Japanese were routed from most of Burma by May 1945. Negotiations then began with the British over the disarming of the AFO, which earlier in March the same year had been transformed into a united front comprising the Patriotic Burmese Forces,

The Japanese were routed from most of Burma by May 1945. Negotiations then began with the British over the disarming of the AFO, which earlier in March the same year had been transformed into a united front comprising the Patriotic Burmese Forces, the Communists

The Communist Alliance was registered on 16 March 2009 with the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) as an Australian political party. It was an alliance of a number of Communist groups, individuals and ethnic-based communist parties. The Allian ...

and the Socialists, and renamed the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League

The Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League (AFPFL), ; abbreviated , ''hpa hsa pa la'' was the dominant political alliance in Burma from 1945 to 1958. It consisted of political parties and mass and class organizations.

The league evolved out of ...

(AFPFL). Had the British Governor of Burma, Reginald Dorman-Smith, still in exile in Simla, and General William Slim gotten their way, the BNA would have been declared illegal and dissolved. Aung San would have been arrested as a traitor for his cooperation with the Japanese and charged with war crimes. However, Supreme Allied Commander Louis Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of German ...

was anxious to avoid a civil war and to secure the cooperation of Aung San, who had authority over thousands of highly politicised troops.

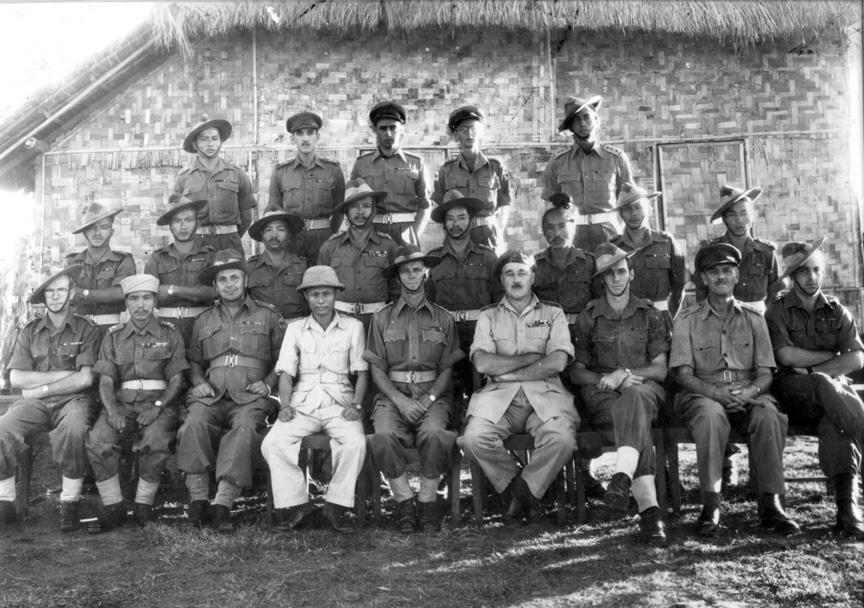

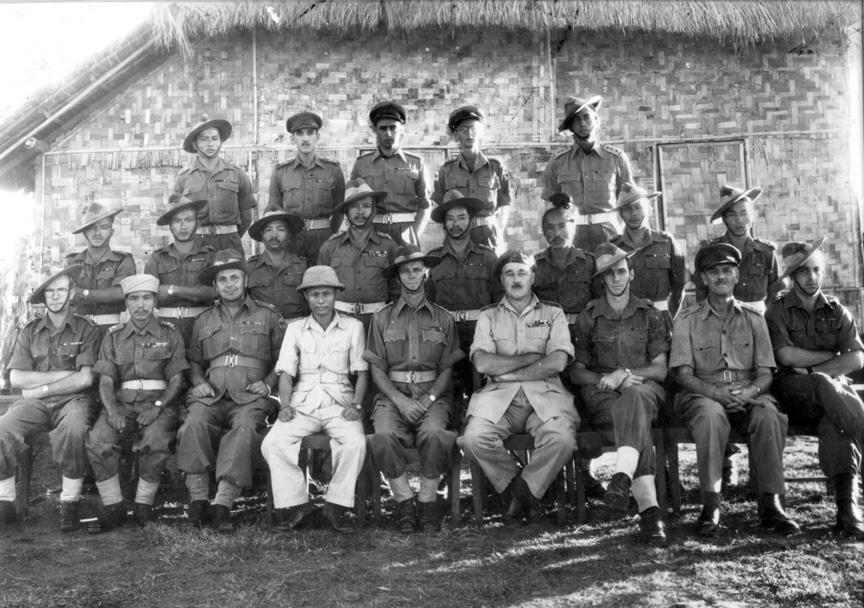

When the British noticed with alarm that PBF troops were withholding weapons, ready to go underground, tense negotiations in a conference in

When the British noticed with alarm that PBF troops were withholding weapons, ready to go underground, tense negotiations in a conference in Kandy

Kandy ( si, මහනුවර ''Mahanuwara'', ; ta, கண்டி Kandy, ) is a major city in Sri Lanka located in the Central Province. It was the last capital of the ancient kings' era of Sri Lanka. The city lies in the midst of hills ...

, Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, were held in September 1945. Aung San, six PBF commanders and four political representatives of the AFPFL met with the Supreme Allied Command were Lord Mountbatten acknowledged the BNA's contribution the victory in Burma to ease tensions. The British offered for around 5,000 veterans and 200 officers of the PBF to form the core of a post-war Burma Army under British command into which colonial Karen

Karen may refer to:

* Karen (name), a given name and surname

* Karen (slang), a term and meme for a demanding woman displaying certain behaviors

People

* Karen people, an ethnic group in Myanmar and Thailand

** Karen languages or Karenic la ...

, Kachin, and Chin

The chin is the forward pointed part of the anterior mandible ( mental region) below the lower lip. A fully developed human skull has a chin of between 0.7 cm and 1.1 cm.

Evolution

The presence of a well-developed chin is considered to be one ...

battalions would be integrated. In the end, only a small number of PBF troops were selected for the army, with most being sent home with two months pay.

Aung San was offered the rank of Deputy Inspector General of the Burma Army, but which he declined upon the return of Governor Dorman-Smith's government. Bo Let Ya instead got the position while Aung San became a civilian political leader in the AFPFL and the leader of the People's Volunteer Organisation (PVO), ostensibly a veterans organisation for ex-BNA, but in reality a paramilitary force who were openly drilling in uniform with numbers eventually reaching 50,000. It was to replace the BNA as a major deterrence against both the British and his communist rivals in the AFPFL. Aung San became head of the AFPFL in 1946 and continued the more peaceful struggle for Burmese independence until his assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

after the overwhelming victory of the AFPFL in the April 1947 constituent assembly elections. Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

finally became independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independe ...

on 4 January 1948.

Significance of the Burma Independence Army today

The BIA was the first major step of the towards Burmese independence without colonial powers involved, even though this result never genuinely occurred under the BIA or its successors. The army’s formation helped to create strong ties between the military and the government which are still present within Burmese society today. In addition, the BIA did achieve results in its need to unite the Burmese as a single nation instead of many different smaller states. Many scholars attribute the failure of the BIA due to the lack of resources, lack of strong administrative control and the failure to include both the highland and lowland regions of Burma. However, the BIA became the first truly national Burmese army and remains honoured in Burma today, with Aung San and many of the Thirty Comrades being seen as national heroes.See also

*State of Burma

The State of Burma (; ja, ビルマ国, ''Biruma-koku'') was a Japanese puppet state created by Japan in 1943 during the Japanese occupation of Burma in World War II.

Background

During the early stages of World War II, the Empire of Japan in ...

* Burma Campaign

*Indian National Army

The Indian National Army (INA; ''Azad Hind Fauj'' ; 'Free Indian Army') was a collaborationist armed force formed by Indian collaborators and Imperial Japan on 1 September 1942 in Southeast Asia during World War II. Its aim was to secure In ...

*Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League

The Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League (AFPFL), ; abbreviated , ''hpa hsa pa la'' was the dominant political alliance in Burma from 1945 to 1958. It consisted of political parties and mass and class organizations.

The league evolved out of ...

* Thirty Comrades

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * *{{cite book, last=Tucker, first=Shelby, title=Among Insurgents, year=2000, publisher=Penguin Books 1941 establishments in Burma Military history of Burma during World War II Military units and formations of Burma in World War II Military units and formations established in 1941 Wars involving Myanmar Collaboration with the Axis Powers