British anti-invasion preparations of the Second World War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

British anti-invasion preparations of the Second World War entailed a large-scale division of

British anti-invasion preparations of the Second World War entailed a large-scale division of

The evacuation of

The evacuation of  The light tanks were mostly MkVIB and the cruiser tanks were A9 / A10 / A13. The infantry tanks included 27 obsolete Matilda MkIs but the rest were almost all the very capable Matilda II. The first Valentine infantry tanks were delivered in May 1940 for trials and 109 had been built by the end of September. In the immediate aftermath of Dunkirk some tank regiments, such as the

The light tanks were mostly MkVIB and the cruiser tanks were A9 / A10 / A13. The infantry tanks included 27 obsolete Matilda MkIs but the rest were almost all the very capable Matilda II. The first Valentine infantry tanks were delivered in May 1940 for trials and 109 had been built by the end of September. In the immediate aftermath of Dunkirk some tank regiments, such as the

By July 1940 the situation had improved radically as all volunteers received uniforms and a modicum of training. 500,000 modern

By July 1940 the situation had improved radically as all volunteers received uniforms and a modicum of training. 500,000 modern

In mid-1940, the principal concern of the Royal Air Force, together with elements of the

In mid-1940, the principal concern of the Royal Air Force, together with elements of the

Although much larger in size and with many more ships, the Royal Navy, unlike the

Although much larger in size and with many more ships, the Royal Navy, unlike the

The British engaged upon an extensive program of field fortification. On 27 May 1940 a Home Defence Executive was formed under General Sir Edmund Ironside, Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces, to organise the defence of Britain. At first defence arrangements were largely static and focused on the coastline (the coastal crust) and, in a classic example of

The British engaged upon an extensive program of field fortification. On 27 May 1940 a Home Defence Executive was formed under General Sir Edmund Ironside, Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces, to organise the defence of Britain. At first defence arrangements were largely static and focused on the coastline (the coastal crust) and, in a classic example of

The areas most vulnerable to an invasion were the south and east coasts of England. In all, a total of 153 Emergency Coastal Batteries were constructed in 1940 in addition to the existing coastal artillery installations, to protect ports and likely landing places. They were fitted with whatever guns were available, which mainly came from naval vessels scrapped since the end of the First World War. These included 6 inch (152 mm), 5.5 inch (140 mm), 4.7 inch (120 mm) and 4 inch (102 mm) guns. Some had little ammunition, sometimes as few as ten rounds apiece. At Dover, two 14 inch (356 mm) guns known as Winnie and Pooh were employed. There were also a few land-based torpedo batteries.

Beaches were blocked with entanglements of barbed wire, usually in the form of three coils of

The areas most vulnerable to an invasion were the south and east coasts of England. In all, a total of 153 Emergency Coastal Batteries were constructed in 1940 in addition to the existing coastal artillery installations, to protect ports and likely landing places. They were fitted with whatever guns were available, which mainly came from naval vessels scrapped since the end of the First World War. These included 6 inch (152 mm), 5.5 inch (140 mm), 4.7 inch (120 mm) and 4 inch (102 mm) guns. Some had little ammunition, sometimes as few as ten rounds apiece. At Dover, two 14 inch (356 mm) guns known as Winnie and Pooh were employed. There were also a few land-based torpedo batteries.

Beaches were blocked with entanglements of barbed wire, usually in the form of three coils of

There were two types of socket roadblocks. The first comprised vertical lengths of railway line placed in sockets in the road and was known as hedgehogs. The second type comprised railway lines or RSJs bent or welded at around a 60° angle, known as hairpins. In both cases, prepared sockets about square were placed in the road, closed by covers when not in use, allowing traffic to pass normally.

Another removable roadblocking system used mines. The extant remains of such systems superficially resemble those of hedgehog or hairpin, but the pits are shallow: just deep enough to take an anti-tank mine. When not in use the sockets were filled with wooden plugs, allowing traffic to pass normally.

Bridges and other key points were prepared for demolition at short notice by preparing chambers filled with explosives. A Depth Charge Crater was a site in a road (usually at a junction) prepared with buried explosives that could be detonated to instantly form a deep crater as an anti-tank obstacle. The

There were two types of socket roadblocks. The first comprised vertical lengths of railway line placed in sockets in the road and was known as hedgehogs. The second type comprised railway lines or RSJs bent or welded at around a 60° angle, known as hairpins. In both cases, prepared sockets about square were placed in the road, closed by covers when not in use, allowing traffic to pass normally.

Another removable roadblocking system used mines. The extant remains of such systems superficially resemble those of hedgehog or hairpin, but the pits are shallow: just deep enough to take an anti-tank mine. When not in use the sockets were filled with wooden plugs, allowing traffic to pass normally.

Bridges and other key points were prepared for demolition at short notice by preparing chambers filled with explosives. A Depth Charge Crater was a site in a road (usually at a junction) prepared with buried explosives that could be detonated to instantly form a deep crater as an anti-tank obstacle. The  Crossing points in the defence networkbridges, tunnels and other weak spotswere called nodes or points of resistance. These were fortified with removable road blocks, barbed wire entanglements and land mines. These passive defences were overlooked by trench works, gun and mortar emplacements, and pillboxes. In places, entire villages were fortified using barriers of Admiralty scaffolding,

Crossing points in the defence networkbridges, tunnels and other weak spotswere called nodes or points of resistance. These were fortified with removable road blocks, barbed wire entanglements and land mines. These passive defences were overlooked by trench works, gun and mortar emplacements, and pillboxes. In places, entire villages were fortified using barriers of Admiralty scaffolding,

Open areas were considered vulnerable to invasion from the air: a landing by paratroops, glider-borne troops or powered aircraft which could land and take off again. Open areas with a straight length of or more within five miles (8 km) of the coast or an airfield were considered vulnerable. These were blocked by trenches or, more usually, by wooden or concrete obstacles, as well as old cars.

Securing an airstrip would be an important objective for the invader. Airfields, considered extremely vulnerable, were protected by trench works and pillboxes that faced inwards towards the runway, rather than outwards. Many of these fortifications were specified by the

Open areas were considered vulnerable to invasion from the air: a landing by paratroops, glider-borne troops or powered aircraft which could land and take off again. Open areas with a straight length of or more within five miles (8 km) of the coast or an airfield were considered vulnerable. These were blocked by trenches or, more usually, by wooden or concrete obstacles, as well as old cars.

Securing an airstrip would be an important objective for the invader. Airfields, considered extremely vulnerable, were protected by trench works and pillboxes that faced inwards towards the runway, rather than outwards. Many of these fortifications were specified by the

In 1940, weapons were critically short; there was a particular scarcity of anti-tank weapons, many of which had been left in France. Ironside had only 170 2-pounder anti-tank guns but these were supplemented by 100 Hotchkiss 6-pounder guns dating from the First World War, improvised into the anti-tank role by the provision of solid shot. By the end of July 1940, an additional nine hundred 75 mm field guns had been received from the USthe British were desperate for any means of stopping armoured vehicles. The

In 1940, weapons were critically short; there was a particular scarcity of anti-tank weapons, many of which had been left in France. Ironside had only 170 2-pounder anti-tank guns but these were supplemented by 100 Hotchkiss 6-pounder guns dating from the First World War, improvised into the anti-tank role by the provision of solid shot. By the end of July 1940, an additional nine hundred 75 mm field guns had been received from the USthe British were desperate for any means of stopping armoured vehicles. The  Early experiments with floating petroleum on the sea and igniting it were not entirely successful: the fuel was difficult to ignite, large quantities were required to cover even modest areas and the weapon was easily disrupted by waves. However, the potential was clear. By early 1941, a flame barrage technique was developed. Rather than attempting to ignite oil floating on water, nozzles were placed above high-water mark with pumps producing sufficient pressure to spray fuel, which produced a roaring wall of flame over, rather than on, the water. Such installations consumed considerable resources and although this weapon was impressive, its network of pipes was vulnerable to pre-landing bombardment; General Brooke did not consider it effective. Initially ambitious plans were cut back to cover just a few miles of beaches. The tests of some of these installations were observed by German aircraft; the British capitalised on this by dropping propaganda leaflets into occupied Europe referring to the effects of the petroleum weapons.

It seems likely the British would have used poison gas against troops on beaches. General Brooke, in an annotation to his published war diaries, stated that he "''... had every intention of using sprayed

Early experiments with floating petroleum on the sea and igniting it were not entirely successful: the fuel was difficult to ignite, large quantities were required to cover even modest areas and the weapon was easily disrupted by waves. However, the potential was clear. By early 1941, a flame barrage technique was developed. Rather than attempting to ignite oil floating on water, nozzles were placed above high-water mark with pumps producing sufficient pressure to spray fuel, which produced a roaring wall of flame over, rather than on, the water. Such installations consumed considerable resources and although this weapon was impressive, its network of pipes was vulnerable to pre-landing bombardment; General Brooke did not consider it effective. Initially ambitious plans were cut back to cover just a few miles of beaches. The tests of some of these installations were observed by German aircraft; the British capitalised on this by dropping propaganda leaflets into occupied Europe referring to the effects of the petroleum weapons.

It seems likely the British would have used poison gas against troops on beaches. General Brooke, in an annotation to his published war diaries, stated that he "''... had every intention of using sprayed

The

The

''Churchill's Channel War: 1939–45''

, Osprey Publishing, * 10 September: Three destroyers found a convoy of invasion transports off Ostend and sank an escort vessel, two trawlers that were towing barges and one large barge. * 13 September: Three destroyers sent to bombard Ostend but the operation was cancelled due to bad weather. A further twelve destroyers swept parts of the French coast between Roches Douvres, Cherbourg, Boulogne and Cape Griz Nez. while an RAF bombing raid destroyed 80 barges at Ostend. * 15 September: Sergeant John Hannah gained the

The German Threat to Britain in World War Two.

By

''The Real Dad's Army''

nbsp;– TV documentary

Churchill's mysterious map

Pillboxesuk.co.uk

Defence of Britain database

* Landmarks centre of Great Britain {{DEFAULTSORT:British Anti-Invasion Preparations Of World War Ii 1940 in military history 1941 in military history 1940 in the United Kingdom 1941 in the United Kingdom Battle of Britain British World War II defensive lines Invasions of the United Kingdom Military history of the United Kingdom during World War II United Kingdom home front during World War II

military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

and civilian mobilisation in response to the threat of invasion (Operation Sea Lion

Operation Sea Lion, also written as Operation Sealion (german: Unternehmen Seelöwe), was Nazi Germany's code name for the plan for an invasion of the United Kingdom during the Battle of Britain in the Second World War. Following the Battle o ...

) by German armed forces in 1940 and 1941. The British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

needed to recover from the defeat of the British Expeditionary Force in France, and 1.5 million men were enrolled as part-time soldiers in the Home Guard

Home guard is a title given to various military organizations at various times, with the implication of an emergency or reserve force raised for local defense.

The term "home guard" was first officially used in the American Civil War, starting w ...

. The rapid construction of field fortification

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

s transformed much of the United Kingdom, especially southern England

Southern England, or the South of England, also known as the South, is an area of England consisting of its southernmost part, with cultural, economic and political differences from the Midlands and the North. Officially, the area includes ...

, into a prepared battlefield. Sea Lion was never taken beyond the preliminary assembly of forces. Today, little remains of Britain's anti-invasion preparations, although reinforced concrete structures such as pillboxes and anti-tank cubes can still be commonly found, particularly in the coastal counties.

Political and military background

On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland; two days later, Britain and Francedeclared war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national government, ...

on Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

, launching the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. Within three weeks, the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

of the Soviet Union invaded

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

the eastern regions of Poland in fulfilment of the secret Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

with Germany. A British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was sent to the Franco-Belgian border, but Britain and France did not take any direct action in support of the Poles. By 1 October, Poland had been completely overrun. There was little fighting over the months that followed. In a period known as the Phoney War

The Phoney War (french: Drôle de guerre; german: Sitzkrieg) was an eight-month period at the start of World War II, during which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front, when French troops invaded Germa ...

, soldiers on both sides trained for war and the French and British constructed and manned defences on the eastern borders of France.

However, the British War Cabinet

A war cabinet is a committee formed by a government in a time of war to efficiently and effectively conduct that war. It is usually a subset of the full executive cabinet of ministers, although it is quite common for a war cabinet to have senio ...

became concerned about exaggerated intelligence reports, aided by German disinformation

Disinformation is false information deliberately spread to deceive people. It is sometimes confused with misinformation, which is false information but is not deliberate.

The English word ''disinformation'' comes from the application of the ...

, of large airborne forces

Airborne forces, airborne troops, or airborne infantry are ground combat units carried by aircraft and airdropped into battle zones, typically by parachute drop or air assault. Parachute-qualified infantry and support personnel serving in a ...

which could be launched against Britain. At the insistence of Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, then the First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

, a request was made that the Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces

Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces was a senior officer in the British Army during the First and Second World Wars. The role of the appointment was firstly to oversee the training and equipment of formations in preparation for their deployment ove ...

, General Sir Walter Kirke, should prepare a plan to repel a large-scale invasion. Kirke presented his plan on 15 November 1939, known as "Plan Julius Caesar" or "Plan J-C" because of the code word

In communication, a code word is an element of a standardized code or protocol. Each code word is assembled in accordance with the specific rules of the code and assigned a unique meaning. Code words are typically used for reasons of reliability, ...

"Julius" which would be used for a likely invasion and "Caesar" for an imminent invasion. Kirke, whose main responsibility was to reinforce the BEF in France, had very limited resources available, with six poorly trained and equipped Territorial Army divisions in England, two in Scotland and three more in reserve

Reserve or reserves may refer to:

Places

* Reserve, Kansas, a US city

* Reserve, Louisiana, a census-designated place in St. John the Baptist Parish

* Reserve, Montana, a census-designated place in Sheridan County

* Reserve, New Mexico, a US ...

. With France still a powerful ally, Kirke believed that the eastern coasts of England and Scotland were the most vulnerable, with ports and airfields given priority.

On 9 April 1940, Germany invaded Denmark and Norway. This operation preempted Britain's own plans to invade Norway. Denmark surrendered immediately, and, after a short-lived attempt by the British to make a stand in the northern part of the country, Norway also fell. The invasion of Norway was a combined forces operation in which the German war machine projected its power across the sea; this German success would come to be seen by the British as a dire portent. On 7 and 8 May 1940, the Norway Debate

The Norway Debate, sometimes called the Narvik Debate, was a momentous debate in the British House of Commons from 7 to 9 May 1940, during the Second World War. The official title of the debate, as held in the '' Hansard'' parliamentary archiv ...

in the British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England.

The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 65 ...

revealed intense dissatisfaction with, and some outright hostility toward, the government of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeaseme ...

. Two days later Chamberlain resigned and was succeeded by Churchill.

On 10 May 1940, Germany invaded France. By that time, the BEF consisted of 10 infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

divisions in three corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was first named as such in 1805. The size of a corps varies great ...

, a tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful ...

brigade and a Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

detachment of around 500 aircraft. The BEF and the best French forces were pinned by the German attack into Belgium and the Netherlands, but were then outflanked by the main attack that came behind them through the Ardennes

The Ardennes (french: Ardenne ; nl, Ardennen ; german: Ardennen; wa, Årdene ; lb, Ardennen ), also known as the Ardennes Forest or Forest of Ardennes, is a region of extensive forests, rough terrain, rolling hills and ridges primarily in Be ...

Forest by highly mobile ''Panzer

This article deals with the tanks (german: panzer) serving in the German Army (''Deutsches Heer'') throughout history, such as the World War I tanks of the Imperial German Army, the interwar and World War II tanks of the Nazi German Wehrma ...

'' divisions of the ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

'', overrunning any defences that could be improvised in their path. In fierce fighting, most of the BEF were able to avoid being surrounded by withdrawing to a small area around the French port of Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.

. With the Germans now on the coast of France, it became evident that an urgent reassessment needed to be given to the possibility of having to resist an attempted invasion of Britain by German forces.

British armed forces

British Army

The evacuation of

The evacuation of British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

forces ( Operation Dynamo) began on 26 May with air cover provided by the Royal Air Force at heavy cost. Over the following ten days, 338,226 French and British soldiers were evacuated to Britain. Most of the personnel were brought back to Britain, but many of the army's vehicles, tanks, guns, ammunition and heavy equipment and the RAF's ground equipment and stores were left behind in France. Some soldiers even returned without their rifles. A further 215,000 were evacuated from ports south of the Channel in the more organised Operation Aerial

Operation Aerial was the evacuation of Allied forces and civilians from ports in western France from 15 to 25 June 1940 during the Second World War. The evacuation followed the Allied military collapse in the Battle of France against Nazi Germ ...

during June.

In June 1940 the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

had 22 infantry divisions and one armoured division. The infantry divisions were, on average, at half strength, and had only one-sixth of their normal artillery. Over 600 medium guns, both 18/25 and 25 pounder

The Ordnance QF 25-pounder, or more simply 25-pounder or 25-pdr, was the major British field gun and howitzer during the Second World War. Its calibre is 3.45-inch (87.6 mm). It was introduced into service just before the war started, com ...

s, and 280 howitzers were available, with a further one hundred 25 pounders manufactured in June. In addition, over 300 4.5-inch howitzers900 were modified in 1940 aloneand some 60 pounder howitzers and their modified 4.5-inch version as well as antiquated examples of the 6-inch howitzer were recovered from reserve after the loss of current models in France. These were augmented with several hundred additional 75-mm M1917 guns and their ammunition from the US. Some sources also state the British army was lacking in transport (just over 2,000 carriers were available, rising to over 3,000 by the end of July). There was a critical shortage of ammunition such that little could be spared for training.

In contrast, records show that the British possessed over 290 million rounds of .303 ammunition of various types on 7 June, rising to over 400 million in August. VII Corps 7th Corps, Seventh Corps, or VII Corps may refer to:

* VII Corps (Grande Armée), a corps of the Imperial French army during the Napoleonic Wars

* VII Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army prior to and during World War I

* VII R ...

was formed to control the Home Forces' general reserve, and included the 1st Armoured Division. In a reorganisation in July, the divisions with some degree of mobility were placed behind the "coastal crust" of defended beach areas from The Wash

The Wash is a rectangular bay and multiple estuary at the north-west corner of East Anglia on the East coast of England, where Norfolk meets Lincolnshire and both border the North Sea. One of Britain's broadest estuaries, it is fed by the riv ...

to Newhaven in Sussex. The General Headquarters Reserve was expanded to two corps of the most capable units. VII Corps was based at Headley Court in Surrey to the south of London and comprised 1st Armoured and 1st Canadian Division

The 1st Canadian Division (French: ''1re Division du Canada'' ) is a joint operational command and control formation based at CFB Kingston, and falls under Canadian Joint Operations Command. It is a high-readiness unit, able to move on very short ...

s with the 1st Army Tank Brigade. IV Corps was based at Latimer House

Latimer House is a large country house at Latimer, Buckinghamshire. It is now branded as De Vere Latimer Estate and functions as a countryside hotel used for country house weddings and conferences. Latimer Place has a small church, St Mary Magdale ...

to the north of London and comprised 2nd Armoured, 42nd and 43rd Infantry divisions. VII Corps also included a brigade, which had been diverted to England when on its way to Egypt, from the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force

The New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) was the title of the military forces sent from New Zealand to fight alongside other British Empire and Dominion troops during World War I (1914–1918) and World War II (1939–1945). Ultimately, the NZE ...

. Two infantry brigades and corps troops including artillery, engineers and medical personnel from the Australian 6th Division were also deployed to the country between June 1940 and January 1941 as part of the Second Australian Imperial Force in the United Kingdom

Elements of the Second Australian Imperial Force (AIF) were located in the United Kingdom (UK) throughout World War II. For most of the war, these comprised only a small number of liaison officers. However, between June and December 1940 arou ...

.

The number of tanks in Britain increased rapidly between June and September 1940 (mid-September being the theoretical planned date for the launch of Operation Sea Lion) as follows:

These figures do not include training tanks or tanks under repair.

The light tanks were mostly MkVIB and the cruiser tanks were A9 / A10 / A13. The infantry tanks included 27 obsolete Matilda MkIs but the rest were almost all the very capable Matilda II. The first Valentine infantry tanks were delivered in May 1940 for trials and 109 had been built by the end of September. In the immediate aftermath of Dunkirk some tank regiments, such as the

The light tanks were mostly MkVIB and the cruiser tanks were A9 / A10 / A13. The infantry tanks included 27 obsolete Matilda MkIs but the rest were almost all the very capable Matilda II. The first Valentine infantry tanks were delivered in May 1940 for trials and 109 had been built by the end of September. In the immediate aftermath of Dunkirk some tank regiments, such as the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards

The 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards was a cavalry regiment of the British Army formed in 1922. It served in the Second World War. However following the reduction of forces at the end of the Cold War and proposals contained in the Options for Change ...

, were expected to go into action as infantry armed with little more than rifles and light machine guns. In June 1940 the regiment received the Beaverette, an improvised armoured car developed by order of the Minister of Aircraft Production

The Minister of Aircraft Production was, from 1940 to 1945, the British government minister at the Ministry of Aircraft Production, one of the specialised supply ministries set up by the British Government during World War II. It was responsible ...

Lord Beaverbrook

William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook (25 May 1879 – 9 June 1964), generally known as Lord Beaverbrook, was a Canadian-British newspaper publisher and backstage politician who was an influential figure in British media and politics o ...

, and former holiday coaches for use as personnel carriers. It did not receive tanks until April 1941 and then the obsolete Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from '' Covena ...

.

Churchill stated "in the last half of September we were able to bring into action on the south coast front sixteen divisions of high quality of which three were armoured divisions or their equivalent in brigades". It is significant that the British Government felt sufficiently confident in Britain's ability to repel an invasion (and in its tank production factories) that it sent 154 tanks (52 light, 52 cruiser and 50 infantry) to Egypt in mid-August. At this time, Britain's factories were almost matching Germany's output in tanks and, by 1941, they would surpass them.

Home Guard

On 14 May 1940, Secretary of State for WarAnthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid promo ...

announced the creation of the Local Defence Volunteers (LDV)later to become known as the Home Guard. Far more men volunteered than the government expected and by the end of June, there were nearly 1.5 million volunteers. There were plenty of personnel for the defence of the country, but there were no uniforms (a simple armband had to suffice) and equipment was in critically short supply. At first, the Home Guard was armed with guns in private ownership, knives or bayonets fastened to poles, Molotov cocktail

A Molotov cocktail (among several other names – ''see other names'') is a hand thrown incendiary weapon constructed from a frangible container filled with flammable substances equipped with a fuse (typically a glass bottle filled with fla ...

s and improvised flamethrower

A flamethrower is a ranged incendiary device designed to project a controllable jet of fire. First deployed by the Byzantine Empire in the 7th century AD, flamethrowers saw use in modern times during World War I, and more widely in World ...

s.

M1917 Enfield Rifle

The M1917 Enfield, the "American Enfield", formally named "United States Rifle, cal .30, Model of 1917" is an American modification and production of the .303-inch (7.7 mm) Pattern 1914 Enfield (P14) rifle (listed in British Service as Rifle No ...

s, 25,000 M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle

The Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) is a family of American automatic rifles and machine guns used by the United States and numerous other countries during the 20th century. The primary variant of the BAR series was the M1918, chambered for the ...

s and millions of rounds of ammunition were bought from the reserve stock of the U.S. armed forces, and rushed by special trains directly to Home Guard units. New weapons were developed that could be produced cheaply without consuming materials that were needed to produce armaments for the regular units. An early example was the No. 76 Special Incendiary Grenade, a glass bottle filled with highly flammable material of which more than six million were made.

The sticky bomb

The "Grenade, Hand, Anti-Tank No. 74", commonly known as the S.T. grenade or simply sticky bomb, was a British hand grenade designed and produced during the Second World War. The grenade was one of a number of anti-tank weapons developed for u ...

was a glass flask filled with nitroglycerin

Nitroglycerin (NG), (alternative spelling of nitroglycerine) also known as trinitroglycerin (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by nitrating g ...

and given an adhesive coating allowing it to be glued to a passing vehicle. In theory, it could be thrown, but in practice it would most likely need to be placedthumped against the target with sufficient force to stickrequiring courage and good fortune to be used effectively. An order for one million sticky bombs was placed in June 1940, but various problems delayed their distribution in large numbers until early 1941, and it is likely that fewer than 250,000 were produced.

A measure of mobility was provided by bicycles, motorcycles, private vehicles and horses. A few units were equipped with armoured cars, some of which were of standard design, but many were improvised locally from commercially available vehicles by the attachment of steel plates. By 1941 the Home Guard had been issued with a series of "sub-artillery", a term used to describe hastily produced and unconventional anti-tank or infantry support weapons, including the Blacker Bombard

The Blacker Bombard, also known as the 29-mm Spigot Mortar, was an infantry anti-tank weapon devised by Lieutenant-Colonel Stewart Blacker in the early years of the Second World War.

Intended as a means to equip Home Guard units with an anti-tan ...

(an anti-tank spigot mortar

A mortar is usually a simple, lightweight, man-portable, muzzle-loaded weapon, consisting of a smooth-bore (although some models use a rifled barrel) metal tube fixed to a base plate (to spread out the recoil) with a lightweight bipod mount and ...

), the Northover Projector (a black-powder mortar), and the Smith Gun

The Smith Gun was an ''ad hoc'' anti-tank artillery piece used by the British Army and Home Guard during the Second World War.

With a German invasion of Great Britain seeming likely after the defeat in the Battle of France, most available weap ...

(a small artillery gun that could be towed by a private motorcar).

Royal Air Force

In mid-1940, the principal concern of the Royal Air Force, together with elements of the

In mid-1940, the principal concern of the Royal Air Force, together with elements of the Fleet Air Arm

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) is one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy and is responsible for the delivery of naval air power both from land and at sea. The Fleet Air Arm operates the F-35 Lightning II for maritime strike, the AW159 Wi ...

, was to contest the control of British airspace with the German Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

. For the Germans, achieving at least local air superiority

Aerial supremacy (also air superiority) is the degree to which a side in a conflict holds control of air power over opposing forces. There are levels of control of the air in aerial warfare. Control of the air is the aerial equivalent of com ...

was an essential prerequisite to any invasion and might even break British morale, forcing them to sue for peace.

If the German air force had prevailed and attempted a landing, a much-reduced Royal Air Force would have been obliged to operate from airfields well away from the southeast of England. Any airfield that was in danger of being captured would have been made inoperable and there were plans to remove all portable equipment from vulnerable radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

bases and completely destroy anything that could not be moved. Whatever was left of the RAF would have been committed to intercepting the invasion fleet in concert with the Royal Navyto fly in the presence of an enemy that enjoys air superiority is very dangerous. However, the RAF would have kept several advantages, such as being able to operate largely over friendly territory, as well as having the ability to fly for longer as, until the Germans were able to operate from airfields in England, ''Luftwaffe'' pilots would still have to fly significant distances to reach their operational area.

A contingency plan called Operation Banquet

Operation Banquet was a British Second World War plan to use every available aircraft against a German invasion in 1940 or 1941. After the Fall of France in June 1940, the British Government made urgent anti-invasion preparations as the Royal ...

required all available aircraft to be committed to the defence. In the event of invasion almost anything that was not a fighter would be converted to a bomberstudent pilots, some in the very earliest stages of training, would use around 350 Tiger Moth and Magister trainers to drop bombs from rudimentary bomb racks.

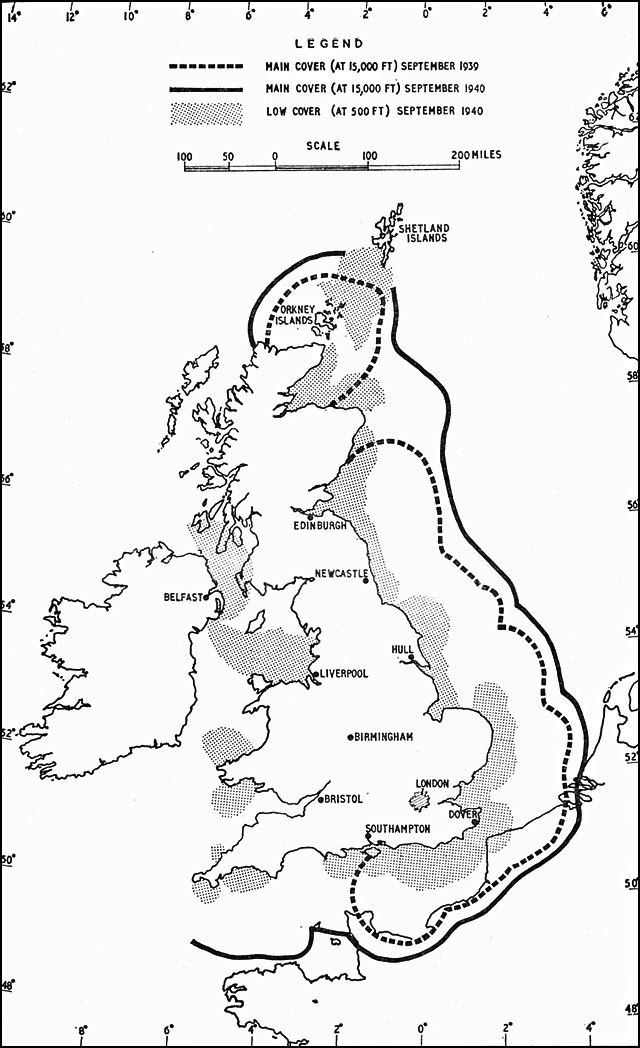

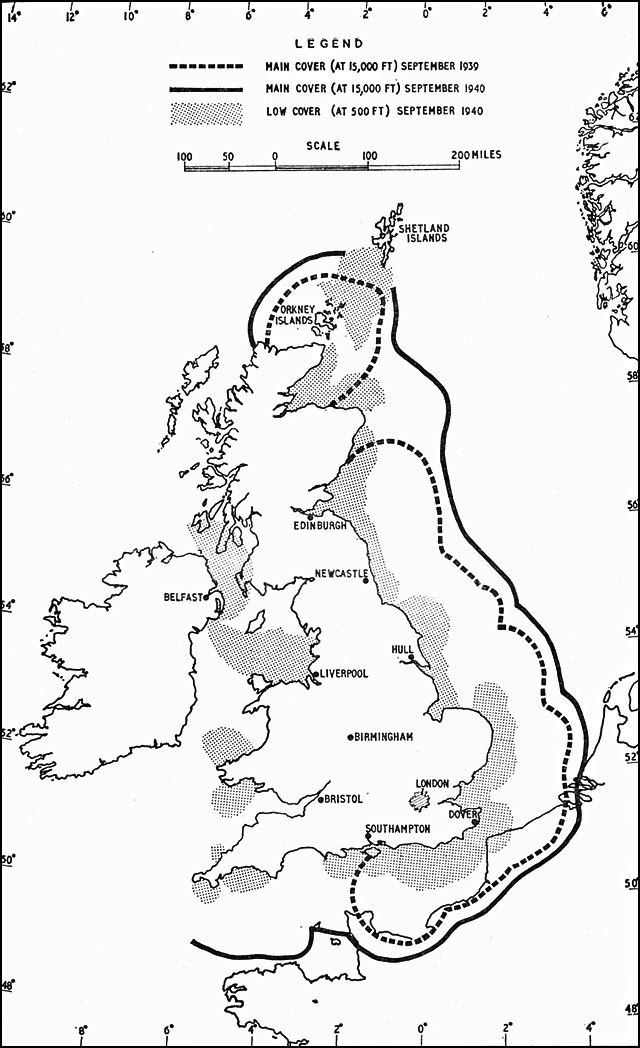

Shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War the Chain Home

Chain Home, or CH for short, was the codename for the ring of coastal Early Warning radar stations built by the Royal Air Force (RAF) before and during the Second World War to detect and track aircraft. Initially known as RDF, and given the of ...

radar system began to be installed in the south of England, with three radar stations being operational by 1937. Although the German High Command suspected that the British may have been developing these systems, Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

detection and evaluation flights had proved inconclusive. As a result, the Germans underestimated the effectiveness of the expanding Chain Home radar system, which became a vital piece of Britain's defensive capabilities during the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

. By the start of the war, around 20 Chain Home stations had been built in the UK; to supplement these and detect aircraft at lower altitudes, the Chain Home Low

Chain Home Low (CHL) was the name of a British early warning radar system operated by the RAF during World War II. The name refers to CHL's ability to detect aircraft flying at altitudes below the capabilities of the original Chain Home (CH) ra ...

was also being constructed.

Royal Navy

Although much larger in size and with many more ships, the Royal Navy, unlike the

Although much larger in size and with many more ships, the Royal Navy, unlike the Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the a ...

, had many commitments, including against Japan and guarding Scotland and Northern England. The Royal Navy could overwhelm any force that the German Navy could muster but would require time to get its forces in position since they were dispersed, partly because of these commitments and partly to reduce the risk of air attack. On 1 July 1940, one cruiser and 23 destroyers were committed to escort duties in the Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

, plus 12 destroyers and one cruiser on the Tyne Tyne may refer to:

__NOTOC__ Geography

*River Tyne, England

*Port of Tyne, the commercial docks in and around the River Tyne in Tyne and Wear, England

*River Tyne, Scotland

*River Tyne, a tributary of the South Esk River, Tasmania, Australia

People ...

and the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

. More immediately available were ten destroyers at the south coast ports of Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maids ...

and Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

, a cruiser and three destroyers at Sheerness

Sheerness () is a town and civil parish beside the mouth of the River Medway on the north-west corner of the Isle of Sheppey in north Kent, England. With a population of 11,938, it is the second largest town on the island after the nearby tow ...

on the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

, three cruisers and seven destroyers at the Humber

The Humber is a large tidal estuary on the east coast of Northern England. It is formed at Trent Falls, Faxfleet, by the confluence of the tidal rivers Ouse and Trent. From there to the North Sea, it forms part of the boundary between ...

, nine destroyers at Harwich

Harwich is a town in Essex, England, and one of the Haven ports on the North Sea coast. It is in the Tendring District, Tendring district. Nearby places include Felixstowe to the north-east, Ipswich to the north-west, Colchester to the south-w ...

, and two cruisers at Rosyth

Rosyth ( gd, Ros Fhìobh, "headland of Fife") is a town on the Firth of Forth, south of the centre of Dunfermline. According to the census of 2011, the town has a population of 13,440.

The new town was founded as a Garden city-style suburb ...

. The rest of the Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the Firs ...

five battleships, three cruisers and nine destroyerswas based far to the north at Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay a ...

. There were, in addition, many corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the slo ...

s, minesweepers

A minesweeper is a small warship designed to remove or detonate naval mines. Using various mechanisms intended to counter the threat posed by naval mines, minesweepers keep waterways clear for safe shipping.

History

The earliest known usage of ...

, and other small vessels. By the end of July, a dozen additional destroyers were transferred from escort duties to the defence of the homeland, and more would join the Home Fleet shortly after.

At the end of August, the battleship was sent south to Rosyth for anti-invasion duties. She was joined on 13 September by her sister ship , the battlecruiser , three anti-aircraft cruisers and a destroyer flotilla. On 14 September, the old battleship was moved to Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to ...

, also specifically in case of invasion. In addition to these major units, by the beginning of September the Royal Navy had stationed along the south coast of England between Plymouth and Harwich, 4 light cruisers and 57 destroyers tasked with repelling any invasion attempt, a force many times larger than the ships that the Germans had available as naval escorts.

Field fortifications

The British engaged upon an extensive program of field fortification. On 27 May 1940 a Home Defence Executive was formed under General Sir Edmund Ironside, Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces, to organise the defence of Britain. At first defence arrangements were largely static and focused on the coastline (the coastal crust) and, in a classic example of

The British engaged upon an extensive program of field fortification. On 27 May 1940 a Home Defence Executive was formed under General Sir Edmund Ironside, Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces, to organise the defence of Britain. At first defence arrangements were largely static and focused on the coastline (the coastal crust) and, in a classic example of defence in depth

Defence in depth (also known as deep defence or elastic defence) is a military strategy that seeks to delay rather than prevent the advance of an attacker, buying time and causing additional casualties by yielding space. Rather than defeating ...

, on a series of inland anti-tank 'stop' lines. The stop lines were designated command, corps and divisional according to their status and the unit assigned to man them. The longest and most heavily fortified was the General Headquarters anti-tank line, GHQ Line. This was a line of pill boxes and anti-tank trenches that ran from Bristol to the south of London before passing to the east of the capital and running northwards to York. The GHQ line was intended to protect the capital and the industrial heartland of England. Another major line was the Taunton Stop Line, which defended against an advance from England's south-west peninsula. London and other major cities were ringed with inner and outer stop lines.

Military thinking shifted rapidly. Given the lack of equipment and properly trained men, Ironside had little choice but to adopt a strategy of static warfare, but it was soon perceived that this would not be sufficient. Ironside has been criticised for having a siege mentality, but some consider this unfair, as he is believed to have understood the limits of the stop lines and never expected them to hold out indefinitely.

Churchill was not satisfied with Ironside's progress, especially with the creation of a mobile reserve. Anthony Eden, the Secretary of State for War, suggested that Ironside should be replaced by General Alan Brooke

Field Marshal Alan Francis Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke, (23 July 1883 – 17 June 1963), was a senior officer of the British Army. He was Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), the professional head of the British Army, during the Sec ...

(later Viscount Alanbrooke). On 17 July 1940 Churchill spent an afternoon with Brooke during which the general raised concerns about the defence of the country. Two days later Brooke was appointed to replace Ironside.

Brooke's appointment saw a change in focus away from Ironside's stop lines, with cement supplies limited Brooke ordered that its use be prioritised for beach defences and "nodal points". The nodal points, also called anti-tank islands or fortress towns, were focal points of the hedgehog defence and expected to hold out for up to seven days or until relieved.

Coastal crust

The areas most vulnerable to an invasion were the south and east coasts of England. In all, a total of 153 Emergency Coastal Batteries were constructed in 1940 in addition to the existing coastal artillery installations, to protect ports and likely landing places. They were fitted with whatever guns were available, which mainly came from naval vessels scrapped since the end of the First World War. These included 6 inch (152 mm), 5.5 inch (140 mm), 4.7 inch (120 mm) and 4 inch (102 mm) guns. Some had little ammunition, sometimes as few as ten rounds apiece. At Dover, two 14 inch (356 mm) guns known as Winnie and Pooh were employed. There were also a few land-based torpedo batteries.

Beaches were blocked with entanglements of barbed wire, usually in the form of three coils of

The areas most vulnerable to an invasion were the south and east coasts of England. In all, a total of 153 Emergency Coastal Batteries were constructed in 1940 in addition to the existing coastal artillery installations, to protect ports and likely landing places. They were fitted with whatever guns were available, which mainly came from naval vessels scrapped since the end of the First World War. These included 6 inch (152 mm), 5.5 inch (140 mm), 4.7 inch (120 mm) and 4 inch (102 mm) guns. Some had little ammunition, sometimes as few as ten rounds apiece. At Dover, two 14 inch (356 mm) guns known as Winnie and Pooh were employed. There were also a few land-based torpedo batteries.

Beaches were blocked with entanglements of barbed wire, usually in the form of three coils of concertina wire

Concertina wire or Dannert wire is a type of barbed wire or razor wire that is formed in large coils which can be expanded like a concertina. In conjunction with plain barbed wire (and/or razor wire/tape) and steel pickets, it is most ofte ...

fixed by metal posts, or a simple fence of straight wires supported on waist-high posts. The wire would also demarcate extensive minefield

A land mine is an explosive device concealed under or on the ground and designed to destroy or disable enemy targets, ranging from combatants to vehicles and tanks, as they pass over or near it. Such a device is typically detonated automati ...

s, with both anti-tank and anti-personnel mines on and behind the beaches. On many of the more remote beaches this combination of wire and mines represented the full extent of the passive defences.

Portions of Romney Marsh

Romney Marsh is a sparsely populated wetland area in the counties of Kent and East Sussex in the south-east of England. It covers about . The Marsh has been in use for centuries, though its inhabitants commonly suffered from malaria until ...

, which was the planned invasion site of Operation Sea Lion, were flooded and there were plans to flood more of the Marsh if the invasion were to materialise.

Piers, ideal for landing troops, and situated in large numbers along the south coast of England, were disassembled, blocked or otherwise destroyed. Many piers were not repaired until the late 1940s or early 1950s.

Where a barrier to tanks was required, Admiralty scaffolding (also known as beach scaffolding or obstacle Z.1) was constructed. Essentially, this was a fence of scaffolding tubes high and was placed at low water so that tanks could not get a good run at it. Admiralty scaffolding was deployed along hundreds of miles of vulnerable beaches.

The beaches themselves were overlooked by pillboxes of various types. These were sometimes placed low down to get maximum advantage from enfilading fire, whereas others were placed high up making them much harder to capture. Searchlights were installed at the coast to illuminate the sea surface and the beaches for artillery fire.

Many small islands and peninsulas were fortified to protect inlets and other strategic targets. In the Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is the estuary, or firth, of several Scottish rivers including the River Forth. It meets the North Sea with Fife on the north coast and Lothian on the south.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate of ''fjord'', a Norse word meani ...

in east central Scotland, Inchgarvie

Inchgarvie or Inch Garvie is a small, uninhabited island in the Firth of Forth. On the rocks around the island sit four caissons that make up the foundations of the Forth Bridge.

Inchgarvie's fortifications pre-date the modern period. In the day ...

was heavily fortified with several gun emplacements, which can still be seen. This provided invaluable defence from seaborne attacks on the Forth Bridge and Rosyth Dockyard

Rosyth Dockyard is a large naval dockyard on the Firth of Forth at Rosyth, Fife, Scotland, owned by Babcock Marine, which formerly undertook refitting of Royal Navy surface vessels and submarines. Before its privatisation in the 1990s it was ...

, approximately a mile upstream from the bridge. Further out to sea, Inchmickery, north of Edinburgh, was similarly fortified. The remnants of gun emplacements on the coast to the north, in North Queensferry

North Queensferry is a village in Fife, Scotland, situated on the Firth of Forth where the Forth Bridge, the Forth Road Bridge, and the Queensferry Crossing all meet the Fife coast, some from the centre of Edinburgh. It is the southernmost ...

, and south, in Dalmeny

Dalmeny ( gd, Dùn Mheinidh, IPA: �t̪uːnˈvenɪʝ is a village and civil parish in Scotland. It is located on the south side of the Firth of Forth, southeast of South Queensferry and west of Edinburgh city centre. It lies within the tradit ...

, of Inchmickery also remain.

Lines and islands

The primary purpose of the stop lines and the anti-tank islands that followed was to hold up the enemy, slowing progress and restricting the route of an attack. The need to prevent tanks from breaking through was of key importance. Consequently, the defences generally ran along pre-existing barriers to tanks, such as rivers and canals; railway embankments and cuttings; thick woods; and other natural obstacles. Where possible, usually well-drained land was allowed to flood, making the ground too soft to support even tracked vehicles. Thousands of miles of anti-tank ditches were dug, usually by mechanical excavators, but occasionally by hand. They were typically wide and deep and could be either trapezoidal or triangular in section with the defended side being especially steep and revetted with whatever material was available. Elsewhere, anti-tank barriers were made of massive reinforced concrete obstacles, either cubic, pyramidal or cylindrical. The cubes generally came in two sizes: high. In a few places, anti-tank walls were constructedessentially continuously abutted cubes. Large cylinders were made from a section of sewer pipe in diameter filled with concrete typically to a height of , frequently with a dome at the top. Smaller cylinders cast from concrete are also frequently found. Pimples, popularly known as Dragon's teeth, were pyramid-shaped concrete blocks designed specifically to counter tanks which, attempting to pass them, would climb up exposing vulnerable parts of the vehicle and possibly slip down with the tracks between the points. They ranged in size somewhat, but were typically high and about square at the base. There was also a conical form. Cubes, cylinders and pimples were deployed in long rows, often several rows deep, to form anti-tank barriers at beaches and inland. They were also used in smaller numbers to block roads. They frequently sported loops at the top for the attachment of barbed wire. There was also atetrahedral

In geometry, a tetrahedron (plural: tetrahedra or tetrahedrons), also known as a triangular pyramid, is a polyhedron composed of four triangular faces, six straight edges, and four vertex corners. The tetrahedron is the simplest of all the ...

or caltrop

A caltrop (also known as caltrap, galtrop, cheval trap, galthrap, galtrap, calthrop, jackrock or crow's foot''Battle of Alesia'' (Caesar's conquest of Gaul in 52 BC), Battlefield Detectives program, (2006), rebroadcast: 2008-09-08 on History Cha ...

-shaped obstacle, although it seems these were rare.

Where natural anti-tank barriers needed only to be augmented, concrete or wooden posts sufficed.

Roads offered the enemy fast routes to their objectives and consequently they were blocked at strategic points. Many of the road-blocks formed by Ironside were semi-permanent. In many cases, Brooke had these removed altogether, as experience had shown they could be as much of an impediment to friends as to foes. Brooke favoured removable blocks.

The simplest of the removable roadblocks consisted of concrete anti-tank cylinders of various sizes but typically about high and in diameter; these could be manhandled into position as required. Anti-tank cylinders were to be used on roads, and other hard surfaces; deployed irregularly in five rows with bricks or kerbstones scattered nearby to stop the cylinders moving more than 2 ft (0.60m). Cylinders were often placed in front of socket roadblocks as an additional obstacle. One common type of removable anti-tank roadblock comprised a pair of massive concrete buttresses permanently installed at the roadside; these buttresses had holes and/or slots to accept horizontal railway lines or rolled steel joists (RSJs). Similar blocks were placed across railway tracks because tanks can move along railway lines almost as easily as they can along roads. A rare extant example. These blocks would be placed strategically where it was difficult for a vehicle to go aroundanti-tank obstacles and mines being positioned as requiredand they could be opened or closed within a matter of minutes.

Canadian pipe mine

The Canadian pipe mine, also known as the McNaughton tube, was a type of landmine deployed in Britain during the invasion crisis of 1940–1941. It comprised a horizontally bored pipe packed with explosives, and once in place this could be use ...

(later known as the McNaughton Tube after General Andrew McNaughton) was a horizontally bored pipe packed with explosivesonce in place this could be used to instantly ruin a road or runway. Prepared demolitions had the advantage of being undetectable from the airthe enemy could not take any precautions against them, or plot a route of attack around them.

sandbag

A sandbag or dirtbag is a bag or sack made of hessian (burlap), polypropylene or other sturdy materials that is filled with sand or soil and used for such purposes as flood control, military fortification in trenches and bunkers, shielding gl ...

ged positions and loopholes

A loophole is an ambiguity or inadequacy in a system, such as a law or security, which can be used to circumvent or otherwise avoid the purpose, implied or explicitly stated, of the system.

Originally, the word meant an arrowslit, a narrow verti ...

in existing buildings.

Nodes were designated 'A', 'B' or 'C' depending upon how long they were expected to hold out. Home Guard troops were largely responsible for the defence of nodal points and other centres of resistance, such as towns and defended villages. Category 'A' nodal points and anti-tank islands were usually garrisoned by regular troops.

The rate of construction was frenetic: by the end of September 1940, 18,000 pillboxes and numerous other preparations had been completed. Some existing defences such as mediaeval castles and Napoleonic forts were augmented with modern additions such as dragon's teeth and pillboxes; some iron age forts housed anti-aircraft and observer positions. About 28,000 pillboxes and other hardened field fortifications were constructed in the United Kingdom of which about 6,500 still survive. Some defences were disguised and examples are known of pillboxes constructed to resemble haystacks, logpiles and innocuous buildings such as churches and railway stations.

Airfields and open areas

Open areas were considered vulnerable to invasion from the air: a landing by paratroops, glider-borne troops or powered aircraft which could land and take off again. Open areas with a straight length of or more within five miles (8 km) of the coast or an airfield were considered vulnerable. These were blocked by trenches or, more usually, by wooden or concrete obstacles, as well as old cars.

Securing an airstrip would be an important objective for the invader. Airfields, considered extremely vulnerable, were protected by trench works and pillboxes that faced inwards towards the runway, rather than outwards. Many of these fortifications were specified by the

Open areas were considered vulnerable to invasion from the air: a landing by paratroops, glider-borne troops or powered aircraft which could land and take off again. Open areas with a straight length of or more within five miles (8 km) of the coast or an airfield were considered vulnerable. These were blocked by trenches or, more usually, by wooden or concrete obstacles, as well as old cars.

Securing an airstrip would be an important objective for the invader. Airfields, considered extremely vulnerable, were protected by trench works and pillboxes that faced inwards towards the runway, rather than outwards. Many of these fortifications were specified by the Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of Stat ...

and defensive designs were unique to airfieldsthese would not be expected to face heavy weapons so the degree of protection was less and there was more emphasis on all-round visibility and sweeping fields of fire. It was difficult to defend large open areas without creating impediments to the movement of friendly aircraft. Solutions to this problem included the pop-up Picket Hamilton forta light pillbox that could be lowered to ground level when the airfield was in use.

Another innovation was a mobile pillbox that could be driven out onto the airfield. This was known as the Bison

Bison are large bovines in the genus ''Bison'' (Greek: "wild ox" (bison)) within the tribe Bovini. Two extant and numerous extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American bison, ''B. bison'', found only in North A ...

and consisted of a lorry with a concrete armoured cabin and a small concrete pillbox on the flat bed.

Constructed in Canada, a 'runway plough', assembled in Scotland, survives at Eglinton Country Park

Eglinton Country Park is located on the grounds of the old Eglinton Castle estate in Kilwinning, North Ayrshire, Scotland (map reference NS 3227 4220). Eglinton Park is situated in the parish of Kilwinning, part of the former district of Cunni ...

. It was purchased by the army in World War II to rip up aerodrome runways and railway lines, making them useless to the occupying forces, if an invasion took place. It was used at the old Eglinton Estate, which had been commandeered by the army, to provide its army operators with the necessary experience. It was hauled by a powerful Foden Trucks tractor, possibly via a pulley and cable system.Eglinton Country Park archive.

Other defensive measures

Other basic defensive measures included the removal of signposts, milestones (some had the carved details obscured with cement) and railway station signs, making it more likely that an enemy would become confused. Petrol pumps were removed from service stations near the coast and there were careful preparations for the destruction of those that were left. Detailed plans were made for destroying anything that might prove useful to the invader such as port facilities, key roads androlling stock

The term rolling stock in the rail transport industry refers to railway vehicles, including both powered and unpowered vehicles: for example, locomotives, freight and passenger cars (or coaches), and non-revenue cars. Passenger vehicles ca ...

. In certain areas, non-essential citizens were evacuated. In the county of Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, 40% of the population was relocated; in East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

, the figure was 50%.

Perhaps most importantly, the population was told what was expected from them. In June 1940, the Ministry of Information published ''If the Invader Comes, what to doand how to do it''. It began:

The first instruction given quite emphatically is that, unless ordered to evacuate, "the order ... as.. to 'stay put'". The roads were not to be blocked by refugees. Further warnings were given not to believe rumours and not to spread them, to be distrustful of orders that might be faked and even to check that an officer giving orders really was British. Further: Britons were advised to keep calm and report anything suspicious quickly and accurately; deny useful things to the enemy such as food, fuel, maps or transport; be ready to block roadswhen ordered to do so"by felling trees, wiring them together or blocking the roads with cars"; to organise resistance at shops and factories; and, finally: "Think before you act. But think always of your country before you think of yourself".

On 13 June 1940, the ringing of church bells was banned; henceforth, they would only be rung by the military or the police to warn that an invasiongenerally meaning by parachutistswas in progress.

More than passive resistance was expectedor at least hoped forfrom the population. Churchill considered the formation of a Home Guard Reserve, given only an armband and basic training on the use of simple weapons, such as Molotov cocktails. The reserve would only have been expected to report for duty in an invasion. Later, Churchill wrote how he envisaged the use of the sticky bomb, "We had the picture in mind that devoted soldiers ''or civilians'' would run close up to the tank and even thrust the bomb upon it, though its explosion cost them their lives talics added for emphasis" The prime minister practised shooting, and told wife Clementine and daughter in law Pamela that he expected them each to kill one or two Germans. When Pamela protested that she did not know how to use a gun, Churchill told her to use a kitchen butcher knife as "You can always take a Hun with you". He later recorded how he intended to use the slogan " You can always take one with you."

In 1941, in towns and villages, invasion committees were formed to cooperate with the military and plan for the worst should their communities be isolated or occupied. The members of committees typically included representatives of the local council, the Air Raid Precautions

Air Raid Precautions (ARP) refers to a number of organisations and guidelines in the United Kingdom dedicated to the protection of civilians from the danger of air raids. Government consideration for air raid precautions increased in the 1920s an ...

service, the fire service, the police, the Women's Voluntary Service

The Royal Voluntary Service (known as the Women's Voluntary Services (WVS) from 1938 to 1966; Women's Royal Voluntary Service (WRVS) from 1966 to 2004 and WRVS from 2004 to 2013) is a voluntary organisation concerned with helping people in need ...

and the Home Guard, as well as officers for medicine, sanitation and food. The plans of these committees were kept in secret ''War Books'', although few remain. Detailed inventories of anything useful were kept: vehicles, animals and basic tools, and lists were made of contact details for key personnel. Plans were made for a wide range of emergencies, including improvised mortuaries and places to bury the dead. Instructions to the invasion committees stated: "... every citizen will regard it as his duty to hinder and frustrate the enemy and help our own forces by every means that ingenuity can devise and common sense suggest."

At the outbreak of the war there were around 60,000 police officers in the United Kingdom, including some 20,000 in London's Metropolitan Police

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), formerly and still commonly known as the Metropolitan Police (and informally as the Met Police, the Met, Scotland Yard, or the Yard), is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement and ...

. Many younger officers joined the armed forces and numbers were maintained by recruiting "war reserve" officers, special constables and by recalling retired officers. As well as their usual duties the police, who are a generally unarmed force in Britain, took on roles checking for enemy agents and arresting deserters.

On the same day as the Battle of Dunkirk

The Battle of Dunkirk (french: Bataille de Dunkerque, link=no) was fought around the French port of Dunkirk (Dunkerque) during the Second World War, between the Allies and Nazi Germany. As the Allies were losing the Battle of France on t ...

, Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

issued a memorandum detailing the police use of firearms in wartime. This detailed the planned training for all officers in the use of pistols and revolvers, as it was decided that even though the police were non-combatant, they would provide armed guards at sites deemed a risk from enemy sabotage, and defend their own police stations from enemy attack. A supplementary secret memorandum of 29 May also required the police to carry out armed motorised patrols of 2–4 men, if invasion happened, though it noted the police were a non-combatant force and should primarily be carrying out law enforcement duties. These arrangements led to high level political discussions; on 1 August 1940 Lord Mottisone, a former cabinet minister, telephoned Churchill to advise that current police regulations would require officers to prevent British civilians resisting the German forces in occupied areas. Churchill considered this unacceptable and he wrote to the home secretary, John Anderson, and Lord Privy Seal, Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

, asking for the regulations to be amended. Churchill wanted the police, ARP wardens and firemen to remain until the last troops withdrew from an area and suggested that such organisations might automatically become part of the military in case of invasion. The War Cabinet discussed the matter and on 12 August Churchill wrote again to the home secretary stating that the police and ARP wardens should be divided into two arms, combatant and non-combatant. The combatant portion would be armed and expected to fight alongside the Home Guard and regular forces and would withdraw with them as necessary. The non-combatant portion would remain in place under enemy occupation, but under orders not to assist the enemy in any way even to maintain order. These instructions were issued to the police by a memorandum from Anderson on 7 September, which stipulated that the non-combatant portion should be a minority and, where possible, made up of older men and those with families.

Because of the additional armed duties the number of firearms allocated to the police was increased. On 1 June 1940 the Metropolitan Police received 3,500 Canadian Ross Rifles of First World War vintage. A further 50 were issued to the London Fire Brigade

The London Fire Brigade (LFB) is the fire and rescue service for London, the capital of the United Kingdom. It was formed by the Metropolitan Fire Brigade Act 1865, under the leadership of superintendent Eyre Massey Shaw. It has 5,992staff, inc ...

and 100 to the Port of London Authority Police. Some 73,000 rounds of .303 rifle ammunition were issued, together with tens of thousands of .22 rounds for small bore rifle and pistol training. By 1941 an additional 2,000 automatic pistols and 21,000 American lend-lease revolvers had been issued to the Metropolitan Police; from March 1942 all officers above the rank of inspector were routinely armed with .45 revolvers and twelve rounds of ammunition.

Guns, petroleum and poison

In 1940, weapons were critically short; there was a particular scarcity of anti-tank weapons, many of which had been left in France. Ironside had only 170 2-pounder anti-tank guns but these were supplemented by 100 Hotchkiss 6-pounder guns dating from the First World War, improvised into the anti-tank role by the provision of solid shot. By the end of July 1940, an additional nine hundred 75 mm field guns had been received from the USthe British were desperate for any means of stopping armoured vehicles. The

In 1940, weapons were critically short; there was a particular scarcity of anti-tank weapons, many of which had been left in France. Ironside had only 170 2-pounder anti-tank guns but these were supplemented by 100 Hotchkiss 6-pounder guns dating from the First World War, improvised into the anti-tank role by the provision of solid shot. By the end of July 1940, an additional nine hundred 75 mm field guns had been received from the USthe British were desperate for any means of stopping armoured vehicles. The Sten

The STEN (or Sten gun) is a family of British submachine guns chambered in 9×19mm which were used extensively by British and Commonwealth forces throughout World War II and the Korean War. They had a simple design and very low production cos ...

submachine gun was developed following the fall of France, to supplement the limited number of Thompson submachine gun