A revival of the art and craft of

stained-glass window

A window is an opening in a wall, door, roof, or vehicle that allows the exchange of light and may also allow the passage of sound and sometimes air. Modern windows are usually glazed or covered in some other transparent or translucent mat ...

manufacture took place in

early 19th-century Britain, beginning with an armorial window created by

Thomas Willement

Thomas Willement (18 July 1786 – 10 March 1871) was an English stained glass artist, called "the father of Victorian stained glass", active from 1811 to 1865.

Biography

Willement was born at St Marylebone, London. Like many early 19th centu ...

in 1811–12. The revival led to stained-glass windows becoming such a common and popular form of coloured pictorial representation that many thousands of people, most of whom would never

commission or purchase a painting, contributed to the commission and purchase of stained-glass windows for their parish church.

Within 50 years of the beginnings of commercial manufacture in the 1830s, British stained glass grew into an enormous and specialised industry, with important centres in

Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

,

Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

,

Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a district in East London and the future administrative centre of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is a part of the East End of London, east of Charing Cross. Part of the historic county of Middlesex, the area formed ...

in

London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

,

Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

,

Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

,

Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

,

Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the Episcopal see, See of ...

and

Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

. The industry also flourished in the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. By 1900 British windows had been installed in

Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan a ...

,

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

,

Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

,

Bangalore

Bangalore (), officially Bengaluru (), is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Karnataka. It has a population of more than and a metropolitan population of around , making it the third most populous city and fifth most ...

,

Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

,

Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populated ...

and

Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by ...

. After the

Great War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

from 1914 to 1918, stained glass design was to change radically.

Background

Following the

Norman conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conq ...

of England in 1066, many churches, abbeys and cathedrals were built, initially in the

Norman or

Romanesque style, then in the increasingly elaborate and decorative

Gothic style

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

. In these churches the windows were generally either large or in multiples so that the light within the building was maximised. The windows were glazed, frequently with

coloured glass held in place by strips of lead. Because flat glass could only be manufactured in small pieces, the method of glazing lent itself to patterning. The pictorial representation of biblical characters and narratives was a feature of Christian churches, often taking the form of murals. By the 12th century stained glass was well adapted to serve this purpose. For 500 years the art flourished and adapted to changing architectural styles.

The vast majority of English glass was smashed by

Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

under

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

. Churches which retain a substantial amount of early glass are rare. Very few of England's large windows are intact. Those that contain a large amount of Medieval glass are usually reconstructed from salvaged fragments. The east, west and south transept windows of

York Minster

The Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Saint Peter in York, commonly known as York Minster, is the cathedral of York, North Yorkshire, England, and is one of the largest of its kind in Northern Europe. The minster is the seat of the Arch ...

and the west and

north Transept windows of

Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour.

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primate of t ...

give an idea of the splendours that have been mostly lost.

In Scotland, which never manufactured its own stained glass but bought from the south, they lost much of their glass not because it was smashed but because the monasteries were disbanded. These monasteries had monks with skills in repairing. When they went, windows gradually fell apart.

Influences on the revival of stained glass

Historic

Medieval windows and drawings of them provided the source and inspiration for nearly all the earlier 19th-century designers.

Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, Kent, is one of the oldest and most famous Christian structures in England. It forms part of a World Heritage Site. It is the cathedral of the Archbishop of Canterbury, currently Justin Welby, leader of the ...

retains more ancient glass than any other English cathedral except York. Much of it appears to be imported from France and some is very early, dating from the 11th century. Much of the glass is in the style of

Chartres Cathedral

Chartres Cathedral, also known as the Cathedral of Our Lady of Chartres (french: Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Chartres), is a Roman Catholic church in Chartres, France, about southwest of Paris, and is the seat of the Bishop of Chartres. Mostly con ...

with deep blue featuring as the background colour in most windows. There are wide borders of stylised floral motifs and small pictorial panels of round, square or diaper shape. Other windows contain rows of apostles, saints and prophets. These windows, including the large west window have a predominance of red, pink, brown and green in the colours, with smaller areas of blue. Most of the glass in this remarkable window is older than the 15th-century stone tracery that contains it, the figure of

Adam

Adam; el, Ἀδάμ, Adám; la, Adam is the name given in Genesis 1-5 to the first human. Beyond its use as the name of the first man, ''adam'' is also used in the Bible as a pronoun, individually as "a human" and in a collective sense as " ...

being part of a series of

Ancestors of Christ

The New Testament provides two accounts of the genealogy of Jesus, one in the Gospel of Matthew and another in the Gospel of Luke. Matthew starts with Abraham, while Luke begins with Adam. The lists are identical between Abraham and David, but ...

that are among the oldest surviving panels in England.

York Minster

The Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Saint Peter in York, commonly known as York Minster, is the cathedral of York, North Yorkshire, England, and is one of the largest of its kind in Northern Europe. The minster is the seat of the Arch ...

also contains much of its original glass including important narrative windows of the Norman period, the famous "Five Sister" windows, the 14th-century west window and 15th-century east window. The "Five Sisters", although repaired countless times so that they now contain a spider's web of lead, still reveal their delicate pattern of simple geometric shapes enhanced by

grisaille

Grisaille ( or ; french: grisaille, lit=greyed , from ''gris'' 'grey') is a painting executed entirely in shades of grey or of another neutral greyish colour. It is particularly used in large decorative schemes in imitation of sculpture. Many g ...

painting. They were the style of window which was most easily imitated by early 19th-century plumber-glaziers. The east and west windows of York are outstanding examples because in each case they are huge, intact, at their original location and by a known craftsman. The west window, designed in about 1340 by Master Robert, contains tiers of saints and stories of Christ and the Virgin Mary, each surmounted by a delicate Gothic canopy in white and yellow-stain, against a red background. The highly ornate tracery lights are filled with floral motifs. White glass ''stone borders'' surround each panel, making it appear to float in its frame. The east window of 1405 was glazed by

John Thornton and is the largest intact medieval window in the world. It presents a narrative in sequential panels of the ''

Creation

Creation may refer to:

Religion

*''Creatio ex nihilo'', the concept that matter was created by God out of nothing

*Creation myth, a religious story of the origin of the world and how people first came to inhabit it

*Creationism, the belief that ...

'', the ''

Fall of Man

The fall of man, the fall of Adam, or simply the Fall, is a term used in Christianity to describe the transition of the first man and woman from a state of innocent obedience to God to a state of guilty disobedience.

*

*

*

* The doctrine of the ...

'', ''the

Redemption'', ''the

Apocalypse

Apocalypse () is a literary genre in which a supernatural being reveals cosmic mysteries or the future to a human intermediary. The means of mediation include dreams, visions and heavenly journeys, and they typically feature symbolic imager ...

'', ''the

Last Judgment

The Last Judgment, Final Judgment, Day of Reckoning, Day of Judgment, Judgment Day, Doomsday, Day of Resurrection or The Day of the Lord (; ar, یوم القيامة, translit=Yawm al-Qiyāmah or ar, یوم الدین, translit=Yawm ad-Dīn, ...

'' and ''the Glory of God''.

York also has windows with small diaper-shaped ''quarries'' painted with little birds and other motifs which were much reproduced in the 19th century.

Between them, the windows of York and Canterbury cathedrals provided the examples for different styles of windows—geometric patterns, floral motifs and borders, narratives set in small panels, rows of figures, major thematic schemes.

Scattered all over England, sometimes in remote churches, is similar evidence of the designs, motifs and techniques used in the past. Two churches,

St Neot's in Cornwall and

Fairford in Gloucestershire, are of particular interest. Fairford escaped the depredations of the Puritan era and, uniquely in England, retained its complete medieval cycle of glass. The theme is that of the east window of York, ''

the Salvation of Mankind'', but in this case the theme is spread across all the windows of the church, large and small. The west window, of seven lights, shows a single narrative incident, the ''

Last Judgment

The Last Judgment, Final Judgment, Day of Reckoning, Day of Judgment, Judgment Day, Doomsday, Day of Resurrection or The Day of the Lord (; ar, یوم القيامة, translit=Yawm al-Qiyāmah or ar, یوم الدین, translit=Yawm ad-Dīn, ...

''. This scheme and these particular windows provided a rare source for the designers of narrative windows for parish churches.

Philosophic

Romanticism

In the 18th century there was a growing trend for philosophers, writers and painters to

commune with nature. Nature was seen as all the more attractive if it contained signs of the grand aspirations, ideals and follies of humankind. Few things were considered more romantic than a medieval ruin which conjured up images of the traditional "romances" or idealistic sagas of the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

.

England contained a great number of large Medieval ruins. These were chiefly castles destroyed by the

Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

in the 17th century and, even more significantly, vast abbey churches ruined at the

Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 16th century. These ruined abbey churches suffered three long-term fates. Some were used as quarries for their building materials. The more remote abbeys were simply left to slowly decay. Those that were conveniently placed were awarded, with their associated lands, to favourites of

King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

and his heirs. Thus it was that many of England's nobility grew up in homes that included within their structure part the Gothic remains of an ancient church or its associated monastic buildings. Some of these houses, such as the poet

Byron's home,

Newstead Abbey

Newstead Abbey, in Nottinghamshire, England, was formerly an Augustinian priory. Converted to a domestic home following the Dissolution of the Monasteries, it is now best known as the ancestral home of Lord Byron.

Monastic foundation

The prio ...

, contain reference to their origin within their name.

In the 18th century the owning of such a pile became fashionable. Those of noble lineage who did not have a ruin or a battlemented tower or an interior with pointed arcades promptly built one. Among the earliest of these creations was the novelist

Horace Walpole's refurbishing of his London villa, which gave its name to the pretty and somewhat superficial style of architectural decoration known as

Strawberry Hill Gothick. The movement gained impetus- Sir

Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy ...

built himself a Scottish Baronial mansion,

Abbotsford; the castles of

Warwick

Warwick ( ) is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire in the Warwick District in England, adjacent to the River Avon, Warwickshire, River Avon. It is south of Coventry, and south-east of Birmingham. It is adjoined wit ...

,

Arundel

Arundel ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the Arun District of the South Downs, West Sussex, England.

The much-conserved town has a medieval castle and Roman Catholic cathedral. Arundel has a museum and comes second behind much larg ...

and

Windsor

Windsor may refer to:

Places Australia

* Windsor, New South Wales

** Municipality of Windsor, a former local government area

* Windsor, Queensland, a suburb of Brisbane, Queensland

**Shire of Windsor, a former local government authority around Wi ...

were refurbished by their owners. The movement was just as strong in Germany where "Mad" King

Ludwig II of Bavaria

Ludwig II (Ludwig Otto Friedrich Wilhelm; 25 August 1845 – 13 June 1886) was King of Bavaria from 1864 until his death in 1886. He is sometimes called the Swan King or ('the Fairy Tale King'). He also held the titles of Count Palatine of the ...

indulged his medievalism by building the

Disneyland

Disneyland is a theme park in Anaheim, California. Opened in 1955, it was the first theme park opened by The Walt Disney Company and the only one designed and constructed under the direct supervision of Walt Disney. Disney initially envisio ...

icon of

Neuschwanstein

Neuschwanstein Castle (german: Schloss Neuschwanstein, , Southern Bavarian: ''Schloss Neischwanstoa'') is a 19th-century historicist palace on a rugged hill above the village of Hohenschwangau near Füssen in southwest Bavaria, Germany. The ...

. All over Europe, those who could afford to do so began the restoration and refurbishment of Medieval buildings. The last great Romantic flourish was the building of

Castle Drogo

Castle Drogo is a country house and mixed-revivalist castle near Drewsteignton, Devon, England. Constructed between 1911 and 1930, it was the last castle to be built in England. The client was Julius Drewe, the hugely successful founder of the ...

by

Sir Edwin Lutyens

Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens ( ; 29 March 1869 – 1 January 1944) was an English architect known for imaginatively adapting traditional architectural styles to the requirements of his era. He designed many English country houses, war memoria ...

between 1910 and 1930.

The Oxford Movement

Begun in

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

in 1833 by the theologian

John Keble

John Keble (25 April 1792 – 29 March 1866) was an English Anglican priest and poet who was one of the leaders of the Oxford Movement. Keble College, Oxford, was named after him.

Early life

Keble was born on 25 April 1792 in Fairford, Glouces ...

and supported by John Henry Newman, the

Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a movement of high church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the University of ...

stressed the universality or "catholic" nature of the Christian Church and urged priests of the

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

to reconsider their

pre-Reformation traditions in both

Doctrine

Doctrine (from la, doctrina, meaning "teaching, instruction") is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the essence of teachings in a given branch of knowledge or in a belief syste ...

and

Liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

. While reinforcing the concept of direct descent from the Apostles through the Church of Rome, the movement did not advocate a return to Roman Catholicism. In practice, however, several hundred Anglican priests, including Newman, became Roman Catholic. The long-term effects of the Oxford Movement were the rapid expansion of the

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in Britain and the establishment of Anglo-Catholic liturgical styles in many Anglican churches. The emphasis on liturgical rites brought about an artistic revolution in church building and decoration.

The Cambridge Camden Society

Formed in 1839 as a society of

Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

undergraduates with an interest in Medieval architecture,

this group developed into a powerful movement for the recording, study preservation of England's ancient churches, the analysis and definition of architectural style and the dissemination of such information through its publications, chiefly a monthly journal ''The Ecclesiologist'' (1841–1869).

The

Cambridge Camden Society

The Cambridge Camden Society, known from 1845 (when it moved to London) as the Ecclesiological Society,[Histor ...](_blank)

did much to bring about a revival of medieval styles in the design and appointments of 19th-century churches, as well as in the

restoration of older ones. Their notions were often highly prescriptive, inflexible and intolerant of diversity within the church. They were insistent upon revival rather than originality.

John Ruskin

John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English writer, philosopher, art critic and polymath of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and pol ...

(1819–1900), an art critic, wrote two books that were highly influential in Art Philosophy. In ''The Seven Lamps of Architecture'' (1849) and ''The Stones of Venice'' (1851–1853), he discussed the moral, social and religious implications of buildings, emphasising the desirability of an ethical approach to the practice of the arts. His thinking influenced the

Pre-Raphaelites

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (later known as the Pre-Raphaelites) was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, Jame ...

, whose artistic style Ruskin defended against criticism.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, 1849–1853

This group of artists, of whom

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882), generally known as Dante Gabriel Rossetti (), was an English poet, illustrator, painter, translator and member of the Rossetti family. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhoo ...

,

Edward Burne-Jones

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, 1st Baronet, (; 28 August, 183317 June, 1898) was a British painter and designer associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood which included Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Millais, Ford Madox Brown and Holman ...

,

John Everett Millais

Sir John Everett Millais, 1st Baronet, ( , ; 8 June 1829 – 13 August 1896) was an English painter and illustrator who was one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. He was a child prodigy who, aged eleven, became the youngest ...

and

William Holman Hunt

William Holman Hunt (2 April 1827 – 7 September 1910) was an English painter and one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His paintings were notable for their great attention to detail, vivid colour, and elaborate symbolism ...

were the central figures, rejected the indulgent

classicism

Classicism, in the arts, refers generally to a high regard for a classical period, classical antiquity in the Western tradition, as setting standards for taste which the classicists seek to emulate. In its purest form, classicism is an aesthet ...

, the

materialism

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materialis ...

and the lack of

social responsibility

Social responsibility is an ethical framework in which an individual is obligated to work and cooperate with other individuals and organizations for the benefit of the community that will inherit the world that individual leaves behind.

Social ...

that they perceived in the artistic trends of mid-19th-century painting. They sought to recreate in their works the simple forms, bright colours, religious devotion and artistic anonymity of the period of art that preceded the rise of the great and famous individuals of the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

period. They initially exhibited their works signed only with the initials PRB,

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (later known as the Pre-Raphaelites) was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, Jame ...

.

The Arts and Crafts Movement

William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He w ...

(1834–1896) was for a time a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and was influenced by their ideals and those of John Ruskin. As a precociously diverse designer, he saw the creation of arts in terms of social responsibility. He rejected, as Ruskin did, the mass-production of ornate and decorative wares of all sorts, such as those products of industry that were displayed in the 1851

Crystal Palace Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition which took pl ...

. Morris advocated a return to cottage crafts and the revival and promulgation of old skills. To this end he formed a business partnership with Marshall and Faulkner, employing

Ford Madox Brown

Ford Madox Brown (16 April 1821 – 6 October 1893) was a British painter of moral and historical subjects, notable for his distinctively graphic and often Hogarthian version of the Pre-Raphaelite style. Arguably, his most notable painti ...

, another highly creative and dynamic artist and thus began what is termed "

the Arts and Crafts Movement".

Stained glass was just one of many products of their studio. Morris and Brown saw themselves as original artists working in the spirit of their antecedents. They did not reproduce earlier forms exactly, and because of disagreements with the philosophy of the

Cambridge Camden Society

The Cambridge Camden Society, known from 1845 (when it moved to London) as the Ecclesiological Society,[Histor ...](_blank)

, rarely created stained glass windows for ancient churches.

William Morris's success as an entrepreneur was such that he was able to keep Rossetti, Burne-Jones and others in regular employment as designers. Through their teaching at the

Working Men's College in London the group had enormous influence on many designers of all sorts.

The Aesthetic Movement

The

Aesthetic Movement

Aestheticism (also the Aesthetic movement) was an art movement in the late 19th century which privileged the aesthetic value of literature, music and the arts over their socio-political functions. According to Aestheticism, art should be pro ...

was a reaction against both the works of industry and the influential Socialist and Christian idealism of Morris and Ruskin who both saw art as directly linked to morality. Followers of the Aesthetic Movement, who included Burne-Jones and other stained glass designers such as Henry Holiday, propounded a philosophy of "Art for Art's sake". The style that evolved was sensuous and luxurious, linked with the rise of

Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau (; ) is an international style of art, architecture, and applied art, especially the decorative arts. The style is known by different names in different languages: in German, in Italian, in Catalan, and also known as the Modern ...

.

Architectural

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin

A. W. N. Pugin (1812–1852) was the son of the Neo-Gothic architect

Augustus Charles Pugin

Augustus Charles Pugin (born Auguste-Charles Pugin; 1762 – 19 December 1832) was an Anglo-French artist, architectural draughtsman, and writer on medieval architecture. He was born in Paris, then the Kingdom of France, but his father was Sw ...

and was a convert to

Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in 1835. He built his first church in 1837. He was an enormously productive and meticulous church architect and designer of interiors. With the growth of Roman Catholicism in England, and the development of large industrial centres there was much scope for his talents. He worked with and employed other designers and was instrumental in encouraging the firm of

John Hardman and Co. of Birmingham to turn their attention to the production of glass.

Pugin's most renowned designs are the interiors, particularly the

House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

, that he designed for the architect

Sir Charles Barry

Sir Charles Barry (23 May 1795 – 12 May 1860) was a British architect, best known for his role in the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster (also known as the Houses of Parliament) in London during the mid-19th century, but also respon ...

, (1795–1860) at the

Houses of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north ban ...

in London. After the destruction by fire of the Houses of Parliament in 1834, Barry had won the commission for their rebuilding, the stipulation being that they should be in the

Gothic style

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

, as the most significant part of the Medieval complex, the Great Hall of

Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

, remained standing. The rebuilding, which took up the rest of Barry's life, included a vast array of arts and crafts of all kinds, not the least of which was stained glass windows, both pictorial and armorial. The knowledge, elegance and sophistication of Pugin's designs imbue and unite the interiors. As an ecclesiastical designer, his influence upon every medium is hard to overstate.

Sir George Gilbert Scott

As an architect

George Gilbert Scott

Sir George Gilbert Scott (13 July 1811 – 27 March 1878), known as Sir Gilbert Scott, was a prolific English Gothic Revival architect, chiefly associated with the design, building and renovation of churches and cathedrals, although he started ...

, (1811–1878), was persuaded by Pugin to turn his creativity towards Gothic Revival. Scott was an Anglican, his first significant commission being the design of the

Martyrs' Memorial

The Martyrs' Memorial is a stone monument positioned at the intersection of St Giles', Magdalen Street and Beaumont Street, to the west of Balliol College, Oxford, England. It commemorates the 16th-century Oxford Martyrs.

History

The monume ...

in

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, a powerful and highly visible architectural statement against the

Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a movement of high church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the University of ...

. To Sir Gilbert fell the task of

restoration of many of England's finest Medieval structures including

Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of ...

,

Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

,

Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

,

Ely and

Durham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

*County Durham, an English county

* Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in N ...

Cathedrals. In the restorations, he was to employ and influence a great number of designers, including major stained glass firms.

John Loughborough Pearson

Pearson Pearson may refer to:

Organizations Education

*Lester B. Pearson College, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

*Pearson College (UK), London, owned by Pearson PLC

*Lester B. Pearson High School (disambiguation)

Companies

*Pearson PLC, a UK-based int ...

(1817–1897) was, like Scott, chiefly a restorer of churches. His major work was the creation of the new cathedral at

Truro

Truro (; kw, Truru) is a cathedral city and civil parish in Cornwall, England. It is Cornwall's county town, sole city and centre for administration, leisure and retail trading. Its population was 18,766 in the 2011 census. People of Truro ...

in

Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a Historic counties of England, historic county and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people ...

.

Greek Thomson

Alexander Thomson

Alexander "Greek" Thomson (9 April 1817 – 22 March 1875) was an eminent Scottish architect and architectural theorist who was a pioneer in sustainable building. Although his work was published in the architectural press of his day, it was l ...

, nicknamed "Greek", (1817–1875), was one of the best known Scottish architects of his day and had a profound effect on later architects, particularly

Charles Rennie MacIntosh

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (7 June 1868 – 10 December 1928) was a Scottish architect, designer, water colourist and artist. His artistic approach had much in common with European Symbolism. His work, alongside that of his wife Margaret Macd ...

. His building designs are curious and eclectic combinations of elements from the

Classical, the

Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( it, Rinascimento ) was a period in Italian history covering the 15th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Europe and marked the trans ...

, the

Egyptian and the

Exotic

Exotic may refer to:

Mathematics and physics

* Exotic R4, a differentiable 4-manifold, homeomorphic but not diffeomorphic to the Euclidean space R4

*Exotic sphere, a differentiable ''n''-manifold, homeomorphic but not diffeomorphic to the ordinar ...

. He designed a number of churches with richly decorated interiors and employed several stained glass firms to furnish them with glass in the appropriate style.

Manufacturing

Industrial Revolution

With the

growth of industry in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and in particular the growth of those industries associated with commercial glass production, metal trades,

metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sc ...

and the associated technical advancements, the scene was set for the revival of stained glass manufacture and the development of that industry on an unprecedented scale.

Thomas Willement

Thomas Willement (18 July 1786 – 10 March 1871) was an English stained glass artist, called "the father of Victorian stained glass", active from 1811 to 1865.

Biography

Willement was born at St Marylebone, London. Like many early 19th centu ...

, a plumber and glazier, produced his first armorial window in 1811, and is known as the father of the 19th-century stained glass industry. Because of the prevalence of

leadlight

Leadlights, leaded lights or leaded windows are decorative windows made of small sections of glass supported in lead cames. The technique of creating windows using glass and lead came to be known as came glasswork. The term 'leadlight' could ...

windows, many glaziers had the required skills for making windows in geometric patterns using coloured glass for chapels and churches. Between 1820 and 1840 some 40 different glass painters appear in the London trades directories.

At the time of the showcase of

Victorian enterprise, the

Crystal Palace Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition which took pl ...

of 1851, stained glass manufacture had reached a point where 25 firms were able to display their works, including

John Hardman of

Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

,

William Wailes of

Newcastle Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area in Australia, named after Newcastle ...

,

Ballantine and Allen of

Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

,

Betton and Evans of

Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

and

William Holland of

Warwick

Warwick ( ) is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire in the Warwick District in England, adjacent to the River Avon, Warwickshire, River Avon. It is south of Coventry, and south-east of Birmingham. It is adjoined wit ...

.

Charles Winston

Charles Winston was a 19th-century lawyer whose hobby was the study of Medieval glass. In 1847 he published an influential book on its styles and production, including a translation from Theophilus' ''On Diverse Arts'', the foremost Medieval treatise on painting, stained glass and metalwork, written in the early 12th century.

Winston's interest in the technicalities of coloured glass production led him to take shards of medieval glass to

James Powell and Sons of Whitefriars for analyses and reproduction. Winston observed that windows of medieval glass appeared more luminous than those of early 19th-century production, and set his mind to discovering why this was the case. Winston observed that light streaming through a 19th-century window generally made a coloured pattern on the floor. This was rarely the case with medieval glass. He concluded that the reason that 19th-century glass lacked brilliance was because it was too flat and regular, allowing the light to pass through directly. He recommended a return to the manufacture of hand-made

crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

and

cylinder glass Cylinder blown sheet is a type of hand- blown window glass. It is created with a similar process to broad sheet, but with the use of larger cylinders. In this manufacturing process glass is blown into a cylindrical iron mold. The ends are cut off a ...

with all their inherent refractive irregularities for the specific purpose of creating stained glass windows.

Stylistic developments in 19th-century stained-glass windows

The stylistic trends below did not necessarily follow each other consecutively. Rather, they overlapped and co-existed. Some stained glass studios were essentially a one-man show in which a single craftsmen designed and made windows of a particular style. Other firms were managed with considerable entrepreneurial skills, employing a number of designers. Some designers freelanced- their work can be seen in windows by a number of firms. Some firms changed with changing tastes and survived well into the 20th century. John Hardman & Co. is still in business.

(For ''Glossary of Terms'', see below.)

Armorial windows

These contain precisely painted shields and

heraldic

Heraldry is a discipline relating to the design, display and study of armorial bearings (known as armory), as well as related disciplines, such as vexillology, together with the study of ceremony, rank and pedigree. Armory, the best-known branc ...

decoration utilising painterly skills that had remained in use during the 17th and 18th centuries.

Thomas Willement

Thomas Willement (18 July 1786 – 10 March 1871) was an English stained glass artist, called "the father of Victorian stained glass", active from 1811 to 1865.

Biography

Willement was born at St Marylebone, London. Like many early 19th centu ...

was an armorial painter of windows.

Geometric patterns

These windows are simple and decorative, frequently utilising the skills of the provincial

plumber

A plumber is a tradesperson who specializes in installing and maintaining systems used for potable (drinking) water, and for sewage and drainage in plumbing systems. /

glazier

A glazier is a tradesman responsible for cutting, installing, and removing glass (and materials used as substitutes for glass, such as some plastics).Elizabeth H. Oakes, ''Ferguson Career Resource Guide to Apprenticeship Programs'' ( Infobase: ...

. Many of these windows are among the earliest use of coloured glass but comparatively few have survived because later

Victorians

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardian ...

have replaced them with more elaborate pictorial windows. Some of these windows date from the 1820s.

Quarries

These windows are usually patterned with

fleur de lys

The fleur-de-lis, also spelled fleur-de-lys (plural ''fleurs-de-lis'' or ''fleurs-de-lys''), is a lily (in French, and mean 'flower' and 'lily' respectively) that is used as a decorative design or symbol.

The fleur-de-lis has been used in the ...

and other floral motifs that were suited to the shape of the ''diamond panes''. They added a pleasant glowing ambience to an interior and in many churches in the early 19th century made up the entire glazing. They could be painted or stencilled with designs and are sometimes mould-cast or have impressed motifs. They were systematically replaced one by one when more elaborate windows were donated. These windows generally date from 1830 to 1860.

Powell was a major supplier of impressed and stencilled quarries.

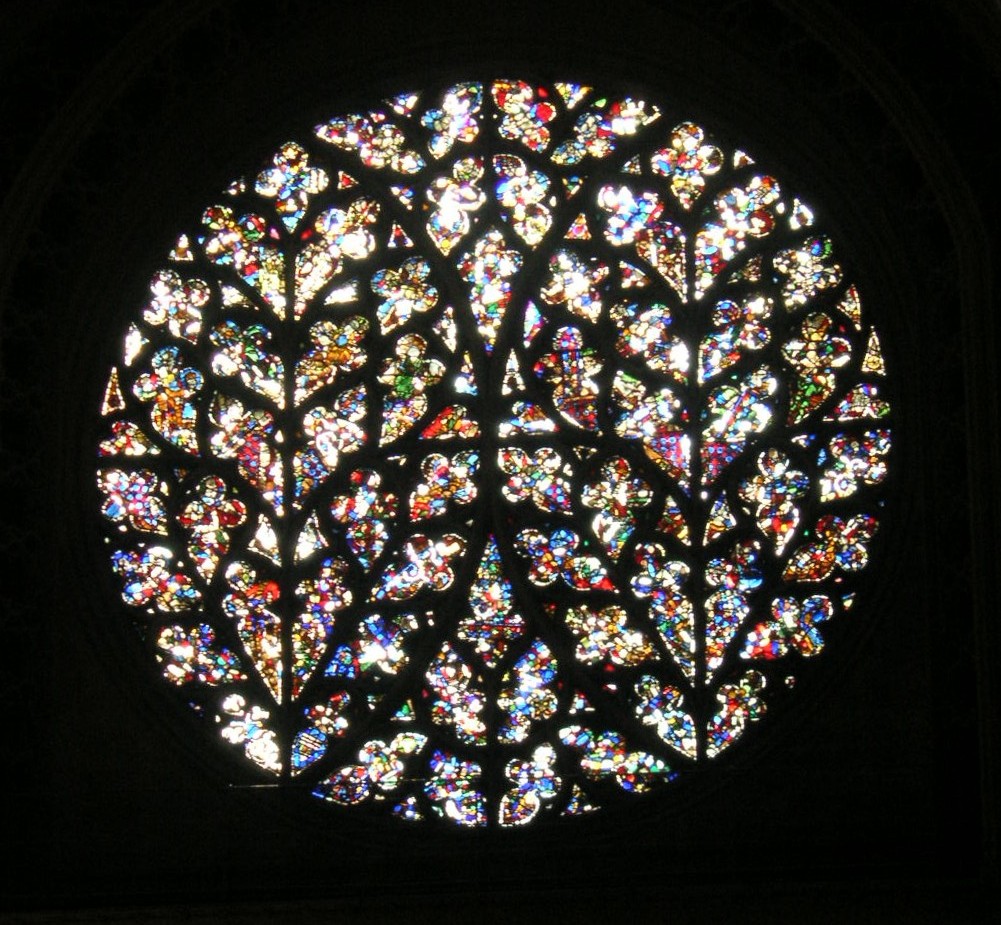

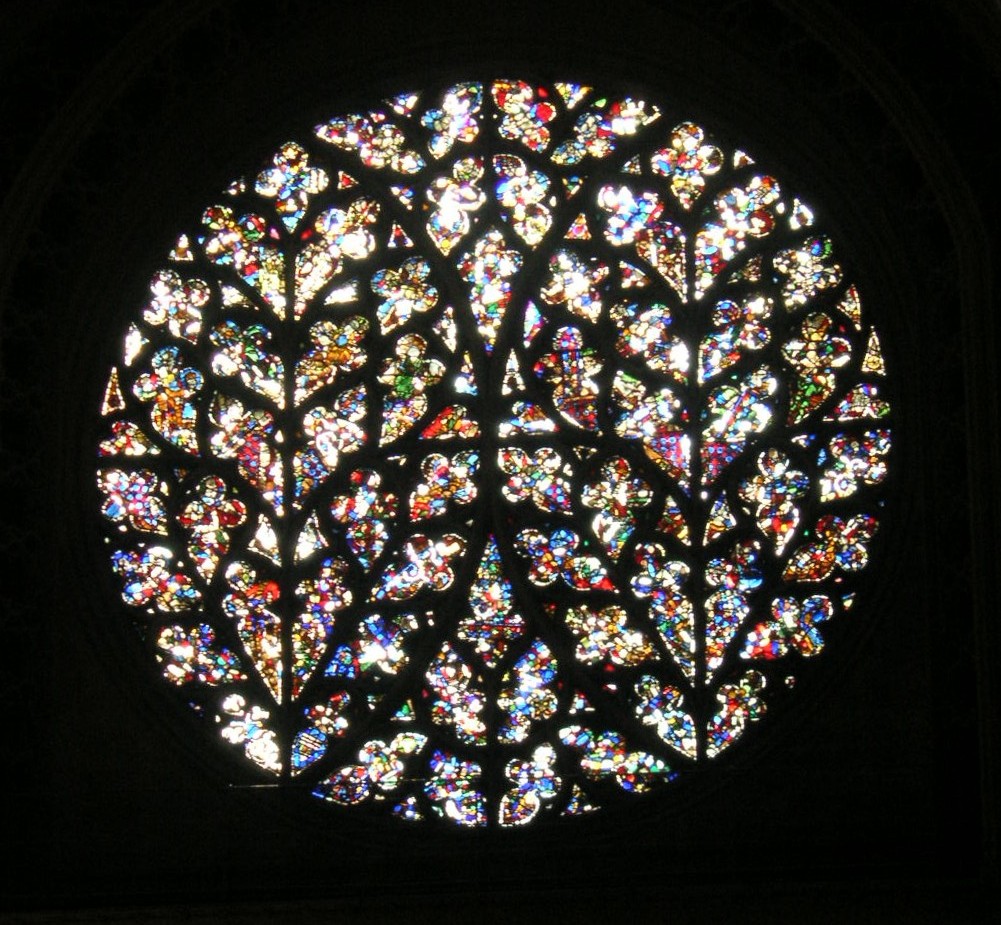

Medieval foliate windows

From studying

Medieval windows, particularly those at

Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, Kent, is one of the oldest and most famous Christian structures in England. It forms part of a World Heritage Site. It is the cathedral of the Archbishop of Canterbury, currently Justin Welby, leader of the ...

, many stained glass artists became adept at designing foliage and decorative borders that reproduce

archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

originals. There are windows of this type in which the foliate design is overlaid with banners bearing

scriptural

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual prac ...

texts.

In those windows that are set with figurative ''rondels'', the style within them is often

Classical (see below) but sometimes

Medievalising and sometimes seeks to reproduce the original style so accurately that to they casual eye they have the appearance of ancient windows. Ancient windows in

Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, Kent, is one of the oldest and most famous Christian structures in England. It forms part of a World Heritage Site. It is the cathedral of the Archbishop of Canterbury, currently Justin Welby, leader of the ...

were removed in the 19th century and replaced with copies. There is a very fine

Jesse Tree

The Tree of Jesse is a depiction in art of the ancestors of Jesus Christ, shown in a branching tree which rises from Jesse of Bethlehem, the father of King David. It is the original use of the family tree as a schematic representation of a ge ...

(the Ancestors of Christ) window of this nature at the eastern end. Two panels of the original have since been returned.

Classical figures

Although often striving for an

exotic

Exotic may refer to:

Mathematics and physics

* Exotic R4, a differentiable 4-manifold, homeomorphic but not diffeomorphic to the Euclidean space R4

*Exotic sphere, a differentiable ''n''-manifold, homeomorphic but not diffeomorphic to the ordinar ...

appearance, the figures in many early 19th-century windows are

classicising in style. Set against a background of ''geometry'', ''quarries'' or ''foliage'', the small painted incidents within ''rondels'' and ''quatrefoils'' are nearly always conservatively

academic

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, ...

in their appearance, with figures based on those in

engravings

Engraving is the practice of incising a design onto a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or glass are engraved, or may provide an in ...

of works by admired painters,

Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, better known as Raphael (; or ; March 28 or April 6, 1483April 6, 1520), was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its clarity of form, ease of composition, and visual ...

,

Titian

Tiziano Vecelli or Vecellio (; 27 August 1576), known in English as Titian ( ), was an Italians, Italian (Republic of Venice, Venetian) painter of the Renaissance, considered the most important member of the 16th-century Venetian school (art), ...

,

Andrea del Sarto

Andrea del Sarto (, , ; 16 July 1486 – 29 September 1530) was an Italian painter from Florence, whose career flourished during the High Renaissance and early Mannerism. He was known as an outstanding fresco decorator, painter of altar-pieces ...

and

Perugino

Pietro Perugino (, ; – 1523), born Pietro Vannucci, was an Italian Renaissance painter of the Umbrian school, who developed some of the qualities that found classic expression in the High Renaissance. Raphael was his most famous pupil.

...

. Often in the case of windows with ornate foliage, the archaeologically correct surrounds are at variance with the style of the rondels which make no attempt to reproduce the medieval.

William Wailes and

Charles Edmund Clutterbuck

Charles Clutterbuck (1806–1861) was a stained glass artist of Maryland Point, Stratford, London, Stratford, London.

Personal Life

He was born in London on 3 September 1806, the son of Edmund and Susannah Clutterbuck, and baptised at Chris ...

were among the important firms.

Gothic Revival

Inspired by

Ruskin,

Pugin

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin ( ; 1 March 181214 September 1852) was an English architect, designer, artist and critic with French and, ultimately, Swiss origins. He is principally remembered for his pioneering role in the Gothic Revival st ...

and the

Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

, some artists sought to reproduce the style of figures that they saw in ancient glass,

illuminated manuscripts

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared document where the text is often supplemented with flourishes such as borders and miniature illustrations. Often used in the Roman Catholic Church for prayers, liturgical services and psalms, the ...

and the few remaining English wall paintings of the

Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

period. A major source was provided by the

Biblia Pauperum

The (Latin for "Paupers' Bible") was a tradition of picture Bibles beginning probably with Ansgar, and a common printed block-book in the later Middle Ages to visualize the typological correspondences between the Old and New Testaments. Unlike ...

or so-called "Poor Man's Bible". The resulting figures are elongated, curvilinear and stylised rather than naturalistic. The drapery folds and scrolls are exaggerated and the gestures are expansive. The painted details are highly linear, crisply defined and elegant. The style lent itself to narrative, to pure colour and to highly decorative effects. While the figures may seem quaint or even naïve, the quality of design of many of these windows is often highly sophisticated and the detailing exquisite. The masters of Gothic revival were

John Hardman and Co. of Birmingham and

Clayton and Bell

Clayton and Bell was one of the most prolific and proficient British workshops of stained-glass windows during the latter half of the 19th century and early 20th century. The partners were John Richard Clayton (1827–1913) and Alfred Bell (1832 ...

.

Arts and Crafts Movement

The group that surrounded and were influenced by

William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He w ...

passed through a series of trends, initially

Pre-Raphaelite

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (later known as the Pre-Raphaelites) was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, Jam ...

, which, although espousing the Medieval, was not

Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

in the archaeological sense, being an esoteric mix of

Medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

,

Early Renaissance

Renaissance art (1350 – 1620 AD) is the painting, sculpture, and decorative arts of the period of European history known as the Renaissance, which emerged as a distinct style in Italy in about AD 1400, in parallel with developments which occ ...

and deeply personal influences. The

Arts and Crafts

A handicraft, sometimes more precisely expressed as artisanal handicraft or handmade, is any of a wide variety of types of work where useful and decorative objects are made completely by one’s hand or by using only simple, non-automated re ...

style lent itself to the depiction of solidly working-class

apostles

An apostle (), in its literal sense, is an emissary, from Ancient Greek ἀπόστολος (''apóstolos''), literally "one who is sent off", from the verb ἀποστέλλειν (''apostéllein''), "to send off". The purpose of such sending ...

and

virtues

Virtue ( la, virtus) is moral excellence. A virtue is a trait or quality that is deemed to be morally good and thus is valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being. In other words, it is a behavior that shows high moral standard ...

set against backgrounds of quarries that resemble glazed earthenware tiles. The botanically accurate and semi-realistic grapevines, sunflowers and other growing things were more prominent than Gothic canopies. Narratives that emphasised hard labour, human decency and charitable love were the themes that lent themselves to enthusiastic treatment by Morris and

Ford Madox Brown

Ford Madox Brown (16 April 1821 – 6 October 1893) was a British painter of moral and historical subjects, notable for his distinctively graphic and often Hogarthian version of the Pre-Raphaelite style. Arguably, his most notable painti ...

.

Burne-Jones and

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882), generally known as Dante Gabriel Rossetti (), was an English poet, illustrator, painter, translator and member of the Rossetti family. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhoo ...

were to become philosophic traitors to the Arts and Crafts Movement by their association with the

Aesthetic Movement

Aestheticism (also the Aesthetic movement) was an art movement in the late 19th century which privileged the aesthetic value of literature, music and the arts over their socio-political functions. According to Aestheticism, art should be pro ...

.

Naturalism

The 1870s was a time of rich ornamentation and

eclecticism

Eclecticism is a conceptual approach that does not hold rigidly to a single paradigm or set of assumptions, but instead draws upon multiple theories, styles, or ideas to gain complementary insights into a subject, or applies different theories i ...

in the arts. The treatment of Gothic canopies which were a feature of so many windows began to change from the brightly coloured, two-dimensional, playful appearance of the 1850s and 60s to an appearance of having been carved from fine white

limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms w ...

.

Tudor and

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

architectural details made an appearance and were often used without reference to the nature of the real

architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings ...

that enclosed the window. The art of painting canopies in this manner was diligently maintained until after

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

.

The

Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

style of figure painting began to give way to a more naturalistic style in which the figures seem more three-dimensional and portrait-like. An important source at this time was German wood engravings and etchings. These were available in a number of forms. Bibles and Bible picture books were available with several different series of such

engravings

Engraving is the practice of incising a design onto a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or glass are engraved, or may provide an in ...

. The works of

Albrecht Dürer

Albrecht Dürer (; ; hu, Ajtósi Adalbert; 21 May 1471 – 6 April 1528),Müller, Peter O. (1993) ''Substantiv-Derivation in Den Schriften Albrecht Dürers'', Walter de Gruyter. . sometimes spelled in English as Durer (without an umlaut) or Due ...

were much admired. One of the advantages of using engravings as a source was that the essentially linear techniques that were employed by the engraver to define forms could be easily interpreted in lead and the fine linear treatment of shadows was likewise easy for the stained glass artist to achieve using the monochrome paint technique. There were also windows imported into England at this time from the studios of

Mayer of Munich which influenced English designers towards this style.

In the late 19th century there is often a great richness in the colouration of the windows, marked by a use of tertiary colours including rich purple, salmon pink, olive green, claret red, saffron and brown. ''Flashed glass'' was skillfully employed to enhance deep folds in robes. With this interest in colour, many windows depict atmospheric effects. Sunsets, glowering storm clouds and blazing glories appear behind the figures.

In line with the naturalistic drafting of the figures, there is a pictorial emphasis on depicting human interaction and response, often with detailed facial expressions and rather flamboyant gestures. Large scenes with large figures were popular. Among the major exponents were

Lavers, Barraud and Westlake

Lavers, Barraud and Westlake were an English firm that produced stained glass windows from 1855 until 1921. They were part of the 19th-century Gothic Revival movement that had a significant influence on English civic, ecclesiastical and domestic ar ...

; and

Heaton, Butler and Bayne

Heaton, Butler and Bayne were an English firm who produced stained-glass windows from 1862 to 1953.

History

Clement Heaton (1824–82) Fleming, John & Hugh Honour. (1977) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Decorative Arts. '' London: Allen Lane, p. 371. ...

. These trends continued, taking two basic directions until

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

.

The notable exceptions to the general trend were a large number of the windows made by Clayton and Bell who produced a diverse range of styles and continued to supply cheerfully coloured Gothic-style windows with a proliferation of bright red and yellow to catch the morning sun in church chancels.

Refinement

A somewhat more reserved style emerged in which the vibrant colouration is toned down in favour of backgrounds that are basically white, discreetly enhanced with ''yellow-stain''. The clothing of the figures is often of the darker shades, royal blue, wine red and dark green and is lined or bordered with intricately decorated yellow-stained glass. The painting of canopies and draperies was taken to a new height. The

monochrome

A monochrome or monochromatic image, object or palette is composed of one color (or values of one color). Images using only shades of grey are called grayscale (typically digital) or black-and-white (typically analog). In physics, monochr ...

painting of faces is intensely detailed. The style lent itself to the depiction of

saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Catholic, Eastern Or ...

s and

prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the ...

s,

bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

s and

admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet ...

s, and

Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and relig ...

(or

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

) enthroned. The most influential firm in this style was

Burlison and Grylls

Burlison and Grylls is an English company who produced stained glass windows from 1868 onwards.

The company of Burlison and Grylls was founded in 1868 at the instigation of the architects George Frederick Bodley and Thomas Garner. Both John Bu ...

. There are many windows by

Charles Eamer Kempe

Charles Eamer Kempe (29 June 1837 – 29 April 1907) was a British Victorian era designer and manufacturer of stained glass. His studios produced over 4,000 windows and also designs for altars and altar frontals, furniture and furnishings, lichg ...

of this type.

Aestheticism

The

Aesthetic Movement

Aestheticism (also the Aesthetic movement) was an art movement in the late 19th century which privileged the aesthetic value of literature, music and the arts over their socio-political functions. According to Aestheticism, art should be pro ...

included

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882), generally known as Dante Gabriel Rossetti (), was an English poet, illustrator, painter, translator and member of the Rossetti family. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhoo ...

,

Burne-Jones, the illustrator

Aubrey Beardsley

Aubrey Vincent Beardsley (21 August 187216 March 1898) was an English illustrator and author. His black ink drawings were influenced by Japanese woodcuts, and depicted the grotesque, the decadent, and the erotic. He was a leading figure in the ...

and writer

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

. They propounded "Art for Art's sake", claiming that Beauty was an end in itself and that the creation of art should not be bound to any social or moral ideals. The Aesthetic artists were primarily concerned with the creation of that which was beautiful. Because of this, windows created by these artists are often stylistically diverse from each other and from other styles, yet are highly recognisable as the work of a particular designer, rather than of a particular workshop.

These windows rarely pay homage to

Medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

origins. They are closely associated with

Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau (; ) is an international style of art, architecture, and applied art, especially the decorative arts. The style is known by different names in different languages: in German, in Italian, in Catalan, and also known as the Modern ...

. The designs are often sinuous, luscious and richly textured, making highly creative use of ''flashed glass'' and repetitive forms. Drifting clouds, sweeping draperies and angel's wings lent themselves to the art of the Aesthetes. The idiosyncrasies of Burne-Jones’ style make his windows particularly easy to recognise. While

Charles Eamer Kempe

Charles Eamer Kempe (29 June 1837 – 29 April 1907) was a British Victorian era designer and manufacturer of stained glass. His studios produced over 4,000 windows and also designs for altars and altar frontals, furniture and furnishings, lichg ...

made many windows that were traditional and "safe", he designed others that are clearly aesthetic.

Christopher Whall

Christopher Whitworth Whall (1849 – 23 December 1924) was a British stained-glass artist who worked from the 1880s and on into the 20th century. He is widely recognised as a leader in the Arts and Crafts Movement and a key figure in t ...

and, in America,

Tiffany were Aesthetic designers.

Opulence

In the last days of the

Empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

, the technical proficiency and artistic excesses of the traditional stained glass artists reached their height. The great windows of this period demonstrate a mastery over figure drawing and stained glass painting. The artists had developed ways of achieving every possible textural effect through the expert application of ground-glass paint and yellow-stain:- babies’ ringlets, old men's beards, silk brocade, dove's feather, ripe grapes, gold braid, glowing pearls and greasy sheep's wool could all be painted to realistic perfection by any number of studios. Many windows of the

Edwardian period

The Edwardian era or Edwardian period of British history spanned the reign of King Edward VII, 1901 to 1910 and is sometimes extended to the start of the First World War. The death of Queen Victoria in January 1901 marked the end of the Victori ...

are the most opulent creations of the stained glass industry. The youthful

Virgin

Virginity is the state of a person who has never engaged in sexual intercourse. The term ''virgin'' originally only referred to sexually inexperienced women, but has evolved to encompass a range of definitions, as found in traditional, modern ...

of the

Annunciation

The Annunciation (from Latin '), also referred to as the Annunciation to the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Annunciation of Our Lady, or the Annunciation of the Lord, is the Christian celebration of the biblical tale of the announcement by the ang ...

,

Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a sur ...

the fisherman,

John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

the itinerant preacher and

Joseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the m ...

the carpenter are all depicted in robes of the most sumptuous nature, lined with cloth of gold and lavishly decorated at the edges with rubies and pearls.

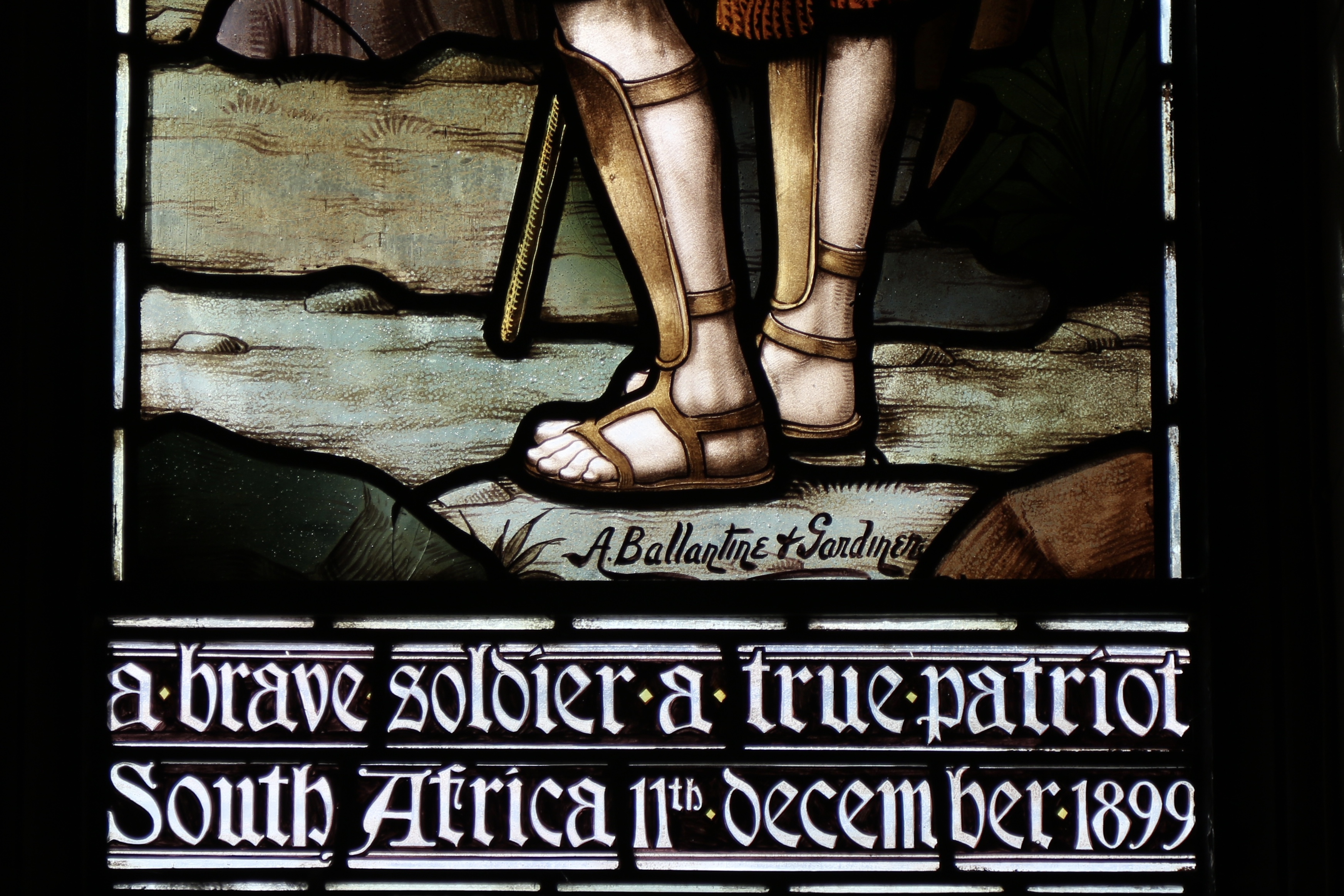

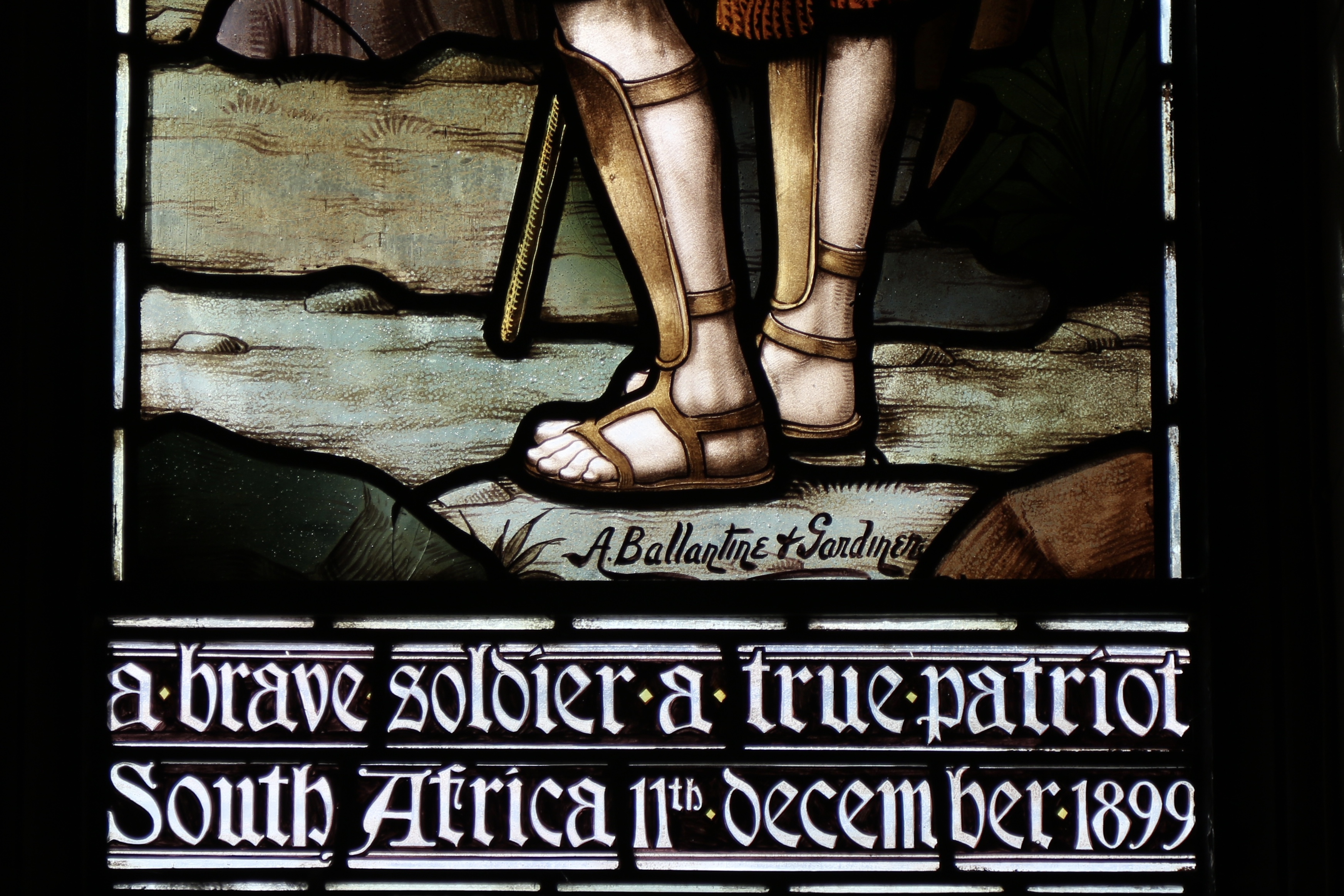

In the years immediately following

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, many of these windows were created by the more conservative studios as memorials to fallen soldiers. Hence there are countless two-light windows of

St George

Saint George ( Greek: Γεώργιος (Geórgios), Latin: Georgius, Arabic: القديس جرجس; died 23 April 303), also George of Lydda, was a Christian who is venerated as a saint in Christianity. According to tradition he was a soldier ...

and

St Michael

Michael (; he, מִיכָאֵל, lit=Who is like El od, translit=Mīḵāʾēl; el, Μιχαήλ, translit=Mikhaḗl; la, Michahel; ar, ميخائيل ، مِيكَالَ ، ميكائيل, translit=Mīkāʾīl, Mīkāl, Mīkhāʾīl), also ...

and even more lancets of the

Good Shepherd

The Good Shepherd ( el, ποιμὴν ὁ καλός, ''poimḗn ho kalós'') is an image used in the pericope of , in which Jesus Christ is depicted as the Good Shepherd who lays down his life for his sheep. Similar imagery is used in Psalm 23 ...

gathering his lost sheep to the fold. These are the last product of the second

Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the '' Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages, Gold being the first and the one during which the G ...

of stained glass window production.

[The example illustrated commemorates a 21-year-old soldier who died in the Great War. His brothers, who also died aged 17 and 19, are commemorated in the adjacent window of Christ with the Children.]

Gallery

File:Chapel glass ca1900 b.jpg, Stencilled quarries of cathedral glass

Cathedral glass is the name given commercially to monochromatic sheet glass. It is thin by comparison with ''slab glass'', may be coloured, and is textured on one side.

The name draws from the fact that windows of stained glass were a feature of ...

, c. 1900

File:St Mildred, Tenterden, Kent - Window - geograph.org.uk - 324270.jpg, Lavers and Barraud, 1864, St Mildred, Tenterden

File:Winchester cathedral 026 brighter.JPG, Burne-Jones window Winchester Cathedral

File:Window, Chester Cathedral detail of east window Heaton Butler & Bayne.JPG, Heaton Butler and Bayne at Chester Cathedral

Common types of 19th-century windows based on content

(For ''Glossary of terms, see below. The terms in italics are explained.)

* Small rectangular or ''diaper quarries'' of clear glass set with an ''armorial'' shield, the colours being painted and fired onto the glass.

* Simple geometric decorative patterns in repeating shapes based on large, often overlapping, circles, squares and ''diapers'' set against a background of clear or decorated quarries, often within a plain brightly coloured border, surrounded by an additional clear border.