Brereton Hall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Brereton Hall is an Elizabethan

Sir William Brereton (1550–1631) built the house in 1586, with this date appearing over the entrance. Although the

Sir William Brereton (1550–1631) built the house in 1586, with this date appearing over the entrance. Although the

John Howard was the first owner of Brereton to not have direct

John Howard was the first owner of Brereton to not have direct

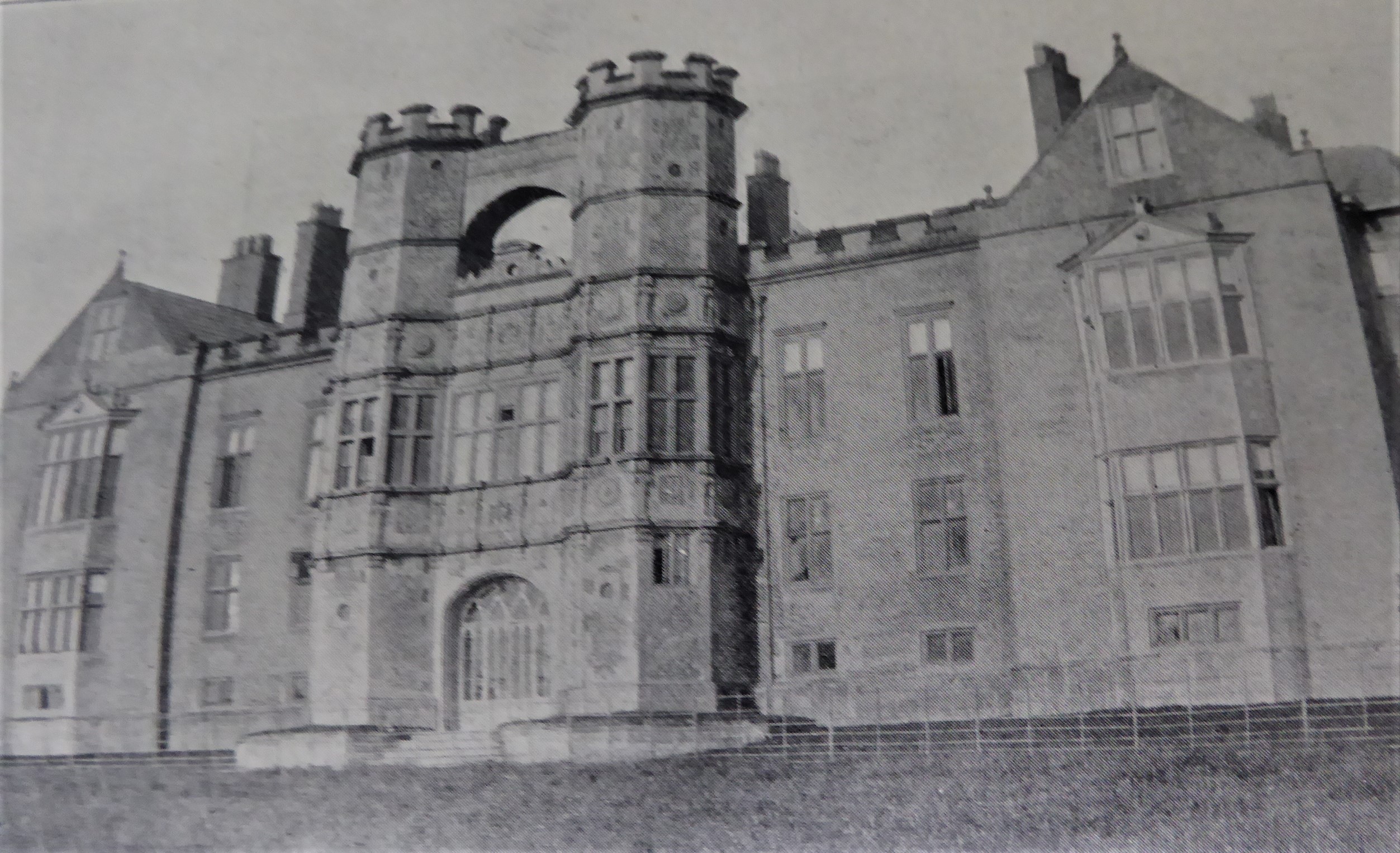

File:Brereton Hall.jpg, alt=, Brereton before 1829, showing the

Brereton appears in Drayton's ''

Brereton appears in Drayton's ''

It is thought that Brereton also inspired

It is thought that Brereton also inspired

Brereton Hall, CheshireInformation about the stained glass from the Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi (CVMA) of Great Britain"A History of Brereton Hall" by Faye Goodwin-Brereton

Houses completed in 1586 Grade I listed buildings in Cheshire Grade I listed houses Country houses in Cheshire

prodigy house

Prodigy houses are large and showy English country houses built by courtiers and other wealthy families, either "noble palaces of an awesome scale" or "proud, ambitious heaps" according to taste. The prodigy houses stretch over the period ...

north of Brereton Green, next to St Oswald's Church in the civil parish

In England, a civil parish is a type of administrative parish used for local government. It is a territorial designation which is the lowest tier of local government below districts and counties, or their combined form, the unitary authorit ...

of Brereton, Cheshire, England. It is recorded in the National Heritage List for England

The National Heritage List for England (NHLE) is England's official database of protected heritage assets. It includes details of all English listed buildings, scheduled monuments, register of historic parks and gardens, protected shipwrecks, a ...

as a designated Grade I listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

. Brereton is not open to the public.

History

Early history

The manor of "Bretune" is listed inDomesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manus ...

, held by the Baron of Kinderton, Gilbert Venables. The name "Brereton''"'' itself comes from the Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th c ...

for an "enclosure

Enclosure or Inclosure is a term, used in English landownership, that refers to the appropriation of "waste" or " common land" enclosing it and by doing so depriving commoners of their rights of access and privilege. Agreements to enclose land ...

among the briars".

The Breretons

Sir William Brereton (1550–1631) built the house in 1586, with this date appearing over the entrance. Although the

Sir William Brereton (1550–1631) built the house in 1586, with this date appearing over the entrance. Although the architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

is unknown, Sir William modelled the house entirely on Rocksavage

Rocksavage or Rock Savage was an Elizabethan mansion, which served as the primary seat of the Savage family. The house now lies in ruins, at in Clifton (now a district of Runcorn), Cheshire, England. Built for Sir John Savage, MP in 1565–156 ...

– the country home of his guardian Sir John Savage, and Savage's daughter, Margaret – whom Brereton would later marry. A portrait of Sir William, dated 1579, with a cameo of Queen Elizabeth in his cap, is at the Detroit Institute of Arts

The Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), located in Midtown Detroit, Michigan, has one of the largest and most significant art collections in the United States. With over 100 galleries, it covers with a major renovation and expansion project comple ...

. Sir Wiliam was created Baron Brereton of Leighlin, Co. Carlow, in 1624.

Sir William's grandson, William, 3rd Baron Brereton (1631–1679) became an original Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemat ...

on 22 April 1663 and was described by Samuel Pepys. His younger son, Francis, 5th Baron Brereton, died a bachelor in 1722, ending the Brereton family male line.

The Holtes and the Bracebridges

Brereton was passed to the Holte family ofAston Hall

Aston Hall is a Grade I listed Jacobean house in Aston, Birmingham, England, designed by John Thorpe and built between 1618 and 1635. It is a leading example of the Jacobean prodigy house.

In 1864, the house was bought by Birmingham Corpor ...

when Jane Brereton married Sir Robert Holte. This placed their surviving child Sir Charles Holte as heir to the estates of both Brereton and Aston. After his death, Brereton was given to Heneage Legge, who let it to the husband of Sir Charles' daughter, Abraham Bracebridge. Bracebridge would later own Brereton when it was bequeathed to him by Legge, upon the latter's death.

1817 sale

Brereton was put up for sale in 1817, with an advertisement placed in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

''. An Act of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the Legislature, legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of ...

stated that Bracebridge's estates of both Brereton and Aston were to be sold. It is thought that Brereton was scheduled to be auctioned, although this fell through. The lawyer himself lived at the house for a period of time. Records of this that survive are scarce and uncertain.

The Howards

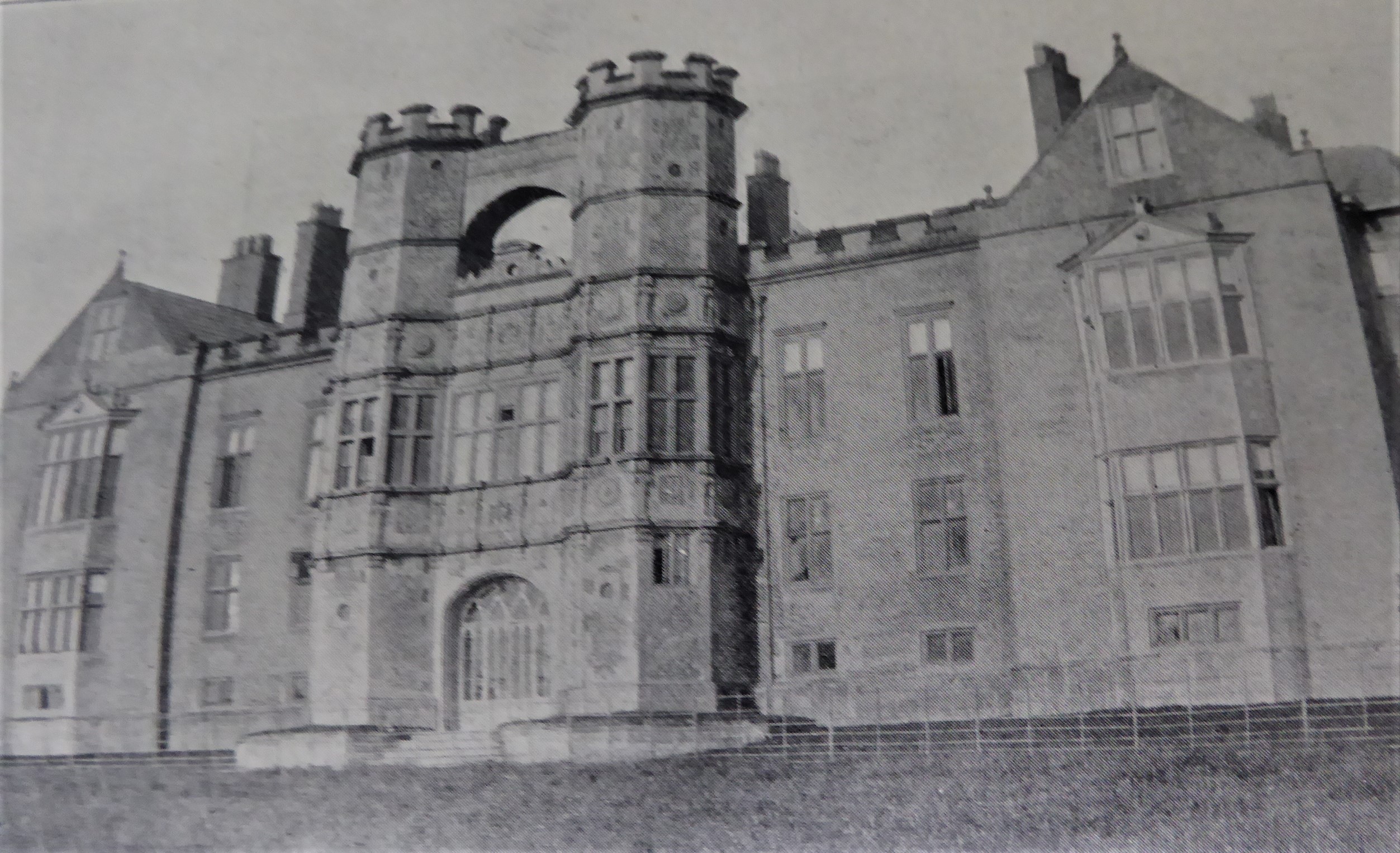

John Howard purchased Brereton. The actual date of Howard's purchase is debated, although Goodwin-Brereton writes in 2020 that this occurred in 1830 (or perhaps 1829), and not 1817 as initially thought. As Brereton had been neglected and unused since 1817, it was now in "a state of disrepair". Howard restored the house and carried out a variety of alterations; namely replacing the twincupola

In architecture, a cupola () is a relatively small, most often dome-like, tall structure on top of a building. Often used to provide a lookout or to admit light and air, it usually crowns a larger roof or dome.

The word derives, via Italian, fro ...

s at the facade with twin battlement

A battlement in defensive architecture, such as that of city walls or castles, comprises a parapet (i.e., a defensive low wall between chest-height and head-height), in which gaps or indentations, which are often rectangular, occur at interv ...

s, influenced by the Regency

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

style, popularized by Strawberry Hill in Twickenham

Twickenham is a suburban district in London, England. It is situated on the River Thames southwest of Charing Cross. Historically part of Middlesex, it has formed part of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames since 1965, and the boroug ...

. The interiors of Brereton were also redecorated in this manner.

John Howard was the first owner of Brereton to not have direct

John Howard was the first owner of Brereton to not have direct aristocratic

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

or gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

family heritage, making their fortune entirely through industrial

Industrial may refer to:

Industry

* Industrial archaeology, the study of the history of the industry

* Industrial engineering, engineering dealing with the optimization of complex industrial processes or systems

* Industrial city, a city dominate ...

means in nearby Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

. After John Howard's death in 1861, his widow lived at the house until 1889. In 1891, Mrs Howard let Brereton to the Moirs for nearly three decades, before it was returned to John Brereton-Howard, the young grandson of the late John Howard, in 1911.

The house had once again declined into a state of disrepair. Brereton-Howard would later be killed in the First World War. The house was passed to a relative named Norman McLean, and in turn to a cousin, Garnet Botfield-Winder.

Brereton School

Mrs M. Massey evacuated a group of children to Brereton during theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

to escape the bombings in Manchester. A school was begun, and would remain at Brereton for nearly half of a century. Mrs M. Fletcher would later purchase the house from Mrs Botfield-Winder, and in doing so, formally create the Brereton Hall Private School for Girls. Mrs Fletcher later wrote about Brereton's "graceful surroundings". The school closed in 1994 as it was impossible to renovate and update the Grade I listed building without large restoration costs.

Present day

Brereton later became the retreat of a pop star who built a recording studio at the back. Brereton Hall was for sale at the time, at £6.5 million. Andy Wood purchased Brereton in 2000, and had since been a family home, changing hands several times over the last two decades. Planning permission for a hotel was rejected in 2017, and Brereton Hall has since come up for sale a number of times. Brereton is no longer open to the public.Architecture

The entry for theGrade I

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

listing by Historic England

Historic England (officially the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England) is an executive non-departmental public body of the British Government sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. It is tasked w ...

reads:1585 altered 1829 and late C19. Stone-dressed brick; leaded roof to front range, slate roofs to cross-wings. The present building suggests a reversed E plan, probably with a great hall behind the gateway forming the central bar, demolished and replaced by an 1829 conservatory.Brereton was modelled on

Rocksavage

Rocksavage or Rock Savage was an Elizabethan mansion, which served as the primary seat of the Savage family. The house now lies in ruins, at in Clifton (now a district of Runcorn), Cheshire, England. Built for Sir John Savage, MP in 1565–156 ...

– the country seat of the Savage family – and is one of a genre of splendid Elizabethan and Jacobean houses built for dynastic

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family,''Oxford English Dictionary'', "dynasty, ''n''." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1897. usually in the context of a monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A d ...

display called " prodigy houses". It is built in brick with stone dressings, formerly in a E-plan, of which the central wing has been demolished and replaced with a 19th-century conservatory. The front range has a lead roof; the cross-wings are roofed in slate. The front range has a basement and two storeys with a turreted central gateway. The octagonal turrets are linked by a bridge and are embattled. Before 1829, they were surmounted by cupola

In architecture, a cupola () is a relatively small, most often dome-like, tall structure on top of a building. Often used to provide a lookout or to admit light and air, it usually crowns a larger roof or dome.

The word derives, via Italian, fro ...

s.

Over the entrance are the royal arms of Elizabeth I in a panel, which are flanked by the Tudor rose

The Tudor rose (sometimes called the Union rose) is the traditional floral heraldic emblem of England and takes its name and origins from the House of Tudor, which united the House of Lancaster and the House of York. The Tudor rose consists o ...

and the Beaufort portcullis. Beyond the entrance is a lower hall and a grand staircase leading to a long gallery

In architecture, a long gallery is a long, narrow room, often with a high ceiling. In Britain, long galleries were popular in Elizabethan and Jacobean houses. They were normally placed on the highest reception floor of English country hou ...

which runs along the front of the house. This leads to the drawing room

A drawing room is a room in a house where visitors may be entertained, and an alternative name for a living room. The name is derived from the 16th-century terms withdrawing room and withdrawing chamber, which remained in use through the 17th cent ...

which contains a frieze

In architecture, the frieze is the wide central section part of an entablature and may be plain in the Ionic or Doric order, or decorated with bas-reliefs. Paterae are also usually used to decorate friezes. Even when neither columns nor ...

with nearly 50 coats of arms and a chimney piece carved with the Brereton emblem, a muzzled bear. Two fireplaces elsewhere are carved in a Serlian manner. The former study of the 2nd Lord Brereton contains a richly carved alabaster

Alabaster is a mineral or rock that is soft, often used for carving, and is processed for plaster powder. Archaeologists and the stone processing industry use the word differently from geologists. The former use it in a wider sense that include ...

fireplace.

Marcus Binney wrote that the house "appears to be just the entrance range of an intended courtyard house with four grand fronts." Nikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British art historian and architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county guides, ''The Buildings of England'' (1 ...

wrote that Brereton is "not easily forgotten".cupola

In architecture, a cupola () is a relatively small, most often dome-like, tall structure on top of a building. Often used to provide a lookout or to admit light and air, it usually crowns a larger roof or dome.

The word derives, via Italian, fro ...

s, which were later replaced by battlement

A battlement in defensive architecture, such as that of city walls or castles, comprises a parapet (i.e., a defensive low wall between chest-height and head-height), in which gaps or indentations, which are often rectangular, occur at interv ...

s

File:Brereton Hall 1899.jpg, alt=, Brereton after 1829, showing the battlements which replaced the prior cupolas

Grounds

The River Croco

TheRiver Croco

The River Croco () is a small river in Cheshire in England. It starts as lowland field drainage west of Congleton, flows along the south edge of Holmes Chapel, and joins the River Dane at Middlewich. It is about long.

According to an histor ...

runs through the grounds at Brereton. "Croco" is most probably a Celtic term, although its meaning remains unknown. The Croco was first recorded in the same year that the house was built. The Croco later flows into the River Weaver

The River Weaver is a river, navigable in its lower reaches, running in a curving route anti-clockwise across west Cheshire, northern England. Improvements to the river to make it navigable were authorised in 1720 and the work, which included ...

, which by coincidence, runs past the ruins

Ruins () are the remains of a civilization's architecture. The term refers to formerly intact structures that have fallen into a state of partial or total disrepair over time due to a variety of factors, such as lack of maintenance, deliberate ...

of Rocksavage

Rocksavage or Rock Savage was an Elizabethan mansion, which served as the primary seat of the Savage family. The house now lies in ruins, at in Clifton (now a district of Runcorn), Cheshire, England. Built for Sir John Savage, MP in 1565–156 ...

. Goodwin-Brereton writes that the Croco was "artificially broadened n front of the housefor effect".

Elizabethan and Victorian landscaping

There is little surviving evidence of an original Elizabethangarden

A garden is a planned space, usually outdoors, set aside for the cultivation, display, and enjoyment of plants and other forms of nature. The single feature identifying even the wildest wild garden is ''control''. The garden can incorporate bot ...

landscape. Although, given the history of the house and the family, it is likely that a formal garden

A formal garden is a garden with a clear structure, geometric shapes and in most cases a symmetrical layout. Its origin goes back to the gardens which are located in the desert areas of Western Asia and are protected by walls. The style of a forma ...

of the sort once existed. Later Victorian forms of planting landscape remain, although the majority was changed during the period in which the house and grounds were a school.

Traditions

Queen Elizabeth I

George Ormerod

George Ormerod (20 October 1785 – 9 October 1873) was an English antiquary and historian. Among his writings was a major county history of Cheshire, in North West England.

Biography

George Ormerod was born in Manchester and educated first ...

wrote of a tradition that Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

made a royal visit to Brereton. The house originally had an E-plan before the Howards' restoration, and the royal arms of Elizabeth I can be seen in the central panel, which hint towards the story being genuine. Goodwin-Brereton writes of a further tradition that Elizabeth I "presented her fan to the Breretons as a memento of the visit." Sir William then supposedly built it into the wall of the room in which the queen had slept. The symbol of a fan can be seen throughout the house.

There is, however, documented evidence to prove that Elizabeth I was in London at the time of her supposed visit.

The Brereton Lake

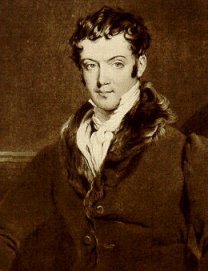

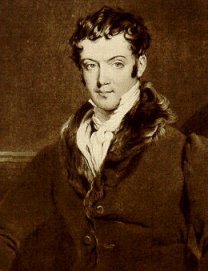

Michael Drayton

Michael Drayton (1563 – 23 December 1631) was an English poet who came to prominence in the Elizabethan era. He died on 23 December 1631 in London.

Early life

Drayton was born at Hartshill, near Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England. Almost nothin ...

and Sir Phillip Sidney wrote of a tradition involving the Brereton Lake, also known as "Bagmere". It was written that before an heir (or "lord") of the Brereton family were to die, a paranormal

Paranormal events are purported phenomena described in popular culture, folk, and other non-scientific bodies of knowledge, whose existence within these contexts is described as being beyond the scope of normal scientific understanding. Not ...

event would occur, in which the lake would turn to blood and strange reflections would appear. Sidney wrote that the "dead loges f treesupsends, from hideous depth", forming a "sore signe" that the "lord f Brereton'slast thread is spun". The event would cease after the death of the Brereton heir. The story became famous, appearing and being popularized in the works of Michael Drayton

Michael Drayton (1563 – 23 December 1631) was an English poet who came to prominence in the Elizabethan era. He died on 23 December 1631 in London.

Early life

Drayton was born at Hartshill, near Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England. Almost nothin ...

and Sir Phillip Sidney.

The Brereton Bear

Brereton is reputedly "haunted" by a number of ghosts, most famously the "muzzled bear" that supposedly roams the grounds at Brereton. This involves the local story in which William Brereton killed his valet in a temper, his punishment being to fight a bear. Brereton was given three days to weave a muzzle to contain the animal, which proved to be successful and saved his life. The symbol of the muzzled bear can be seen throughout the house, as well as in a window in the nearby St. Oswald's Church, and forms part of the Brereton family's coat of arms. The ghost story may have been created and circulated by the pupils at Brereton School.In literature

The ''Poly-Olbion''

Brereton appears in Drayton's ''

Brereton appears in Drayton's ''Poly-Olbion

The ''Poly-Olbion'' is a topographical poem describing England and Wales. Written by Michael Drayton (1563–1631) and published in 1612, it was reprinted with a second part in 1622. Drayton had been working on the project since at least 1598. ...

'', inspired by the traditions around the Brereton Lake. The ''Poly-Olbion'' is a 1612 topographical poem

Topographical poetry or loco-descriptive poetry is a genre of poetry that describes, and often praises, a landscape or place. John Denham's 1642 poem "Cooper's Hill" established the genre, which peaked in popularity in 18th-century England. Exam ...

that totals 15,000 lines of verse, written entirely in alexandrine couplets. In the work, Drayton described the lake as a "black, omnious mere", that "sends up stocks of trees, that on the top do float, by which the world her first did for a wonder note."

''The Seven Wonders of England''

Brereton appears in Sir Phillip Sidney's ''Seven Wonders of England'' – anothertopographical poem

Topographical poetry or loco-descriptive poetry is a genre of poetry that describes, and often praises, a landscape or place. John Denham's 1642 poem "Cooper's Hill" established the genre, which peaked in popularity in 18th-century England. Exam ...

– on the same topic of the lake. Stanza II reads:

The Bruertons have a lake, which, when the sunne Approching warmes, not else, dead loges up sends From hideous depth; which tribute, when it ends, Sore signe it is the lord's last thred is spun. My lake is Sense, where still streames never runne But when my sunne her shining twinnes there bends; Then from his depth with force in her begunne, Long-drowned hopes to watrie eyes it lends; But when that failes my dead hopes up to take, Their master is faire warn'd his will to make.

''Bracebridge Hall''

It is thought that Brereton also inspired

It is thought that Brereton also inspired Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and " The Legen ...

's 1821 '' Bracebridge Hall''. Although it is widely accepted that Aston Hall

Aston Hall is a Grade I listed Jacobean house in Aston, Birmingham, England, designed by John Thorpe and built between 1618 and 1635. It is a leading example of the Jacobean prodigy house.

In 1864, the house was bought by Birmingham Corpor ...

in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1. ...

was the inspiration for the novel, Aston and Brereton were, at one time, both owned by Abraham Bracebridge – who inspired the novel's title. It is thought that Irving was additionally inspired by Brereton, although he never visited.

''Wolf Hall''

"William Brereton" appears as a character inHilary Mantel

Dame Hilary Mary Mantel ( ; born Thompson; 6 July 1952 – 22 September 2022) was a British writer whose work includes historical fiction, personal memoirs and short stories. Her first published novel, '' Every Day Is Mother's Day'', was relea ...

's 2009 novel ''Wolf Hall

''Wolf Hall'' is a 2009 historical novel by English author Hilary Mantel, published by Fourth Estate, named after the Seymour family's seat of Wolfhall, or Wulfhall, in Wiltshire. Set in the period from 1500 to 1535, ''Wolf Hall'' is a symp ...

''. This refers not to the Sir William Brereton (1550–1631) who built the house, but an earlier relative of the same name, William Brereton (1487–1536), who first established the link with the Savage family, and later Rocksavage.

The earlier William Brereton served as Groom of the Privy Chamber

Groom of the Chamber was a position in the Household of the monarch in early modern England. Other ''Ancien Régime'' royal establishments in Europe had comparable officers, often with similar titles. In France, the Duchy of Burgundy, and in Eng ...

to King Henry VIII, and along with George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford

George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford (c. 1504 – 17 May 1536) was an English courtier and nobleman who played a prominent role in the politics of the early 1530s. He was the brother of Anne Boleyn, from 1533 the second wife of King Hen ...

, Sir Henry Norris, Sir Francis Weston

Sir Francis Weston KB (1511 – 17 May 1536) was a gentleman of the Privy Chamber at the court of King Henry VIII of England. He became a friend of the king but was later accused of high treason and adultery with Anne Boleyn, the king's second ...

and a musician, Mark Smeaton

Mark Smeaton ( – 17 May 1536) was a musician at the court of Henry VIII of England, in the household of Queen Anne Boleyn. Smeaton, together with the Queen's brother George Boleyn, 2nd Viscount Rochford, Henry Norris, Francis Weston and Wil ...

, was tried for treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

and adultery with Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and of her execution by beheading for treason and other charges made her a key ...

, the king's second wife. Brereton was beheaded at Tower Hill on 17 May 1536, although many historians are now of the opinion that Anne Boleyn, Brereton and their co-accused were innocent. Brereton was played by Alastair Mackenzie

Alastair Mackenzie (born 8 February 1970) is a Scottish actor from Perth.

Early life

He was born in Trinafour, near Perth, and educated at Westbourne House School and Glenalmond College in Perthshire.

Mackenzie left home at the age of 1 ...

in the 2015 TV adaptation of the novel.

See also

* Grade I listed buildings in Cheshire East *Listed buildings in Brereton, Cheshire

Brereton, Cheshire, Brereton is a Civil parishes in England, civil parish in Cheshire East, England. It contains 21 buildings that are recorded in the National Heritage List for England as designated listed buildings. Of these, one is list ...

References

Further reading

*Goodwin-Brereton, Faye (May 2020). ''A History of Brereton Hall'' *External links

{{commons categoryBrereton Hall, Cheshire

Houses completed in 1586 Grade I listed buildings in Cheshire Grade I listed houses Country houses in Cheshire