The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

(USSR) which resulted in the end of the country's and its federal government's existence as a sovereign state, thereby resulting in its constituent republics gaining full

sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

on 26 December 1991. It brought an end to

General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev's (later also

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

) effort to

reform the Soviet political and economic system in an attempt to stop a

period of political stalemate and economic backslide. The Soviet Union had experienced internal stagnation and ethnic separatism. Although highly centralized until its final years, the country was made up of fifteen top-level republics that served as homelands for different ethnicities. By late 1991, amid a catastrophic political crisis, with several republics already departing the Union and the waning of centralized power, the leaders of

three of its founding members declared that the

Soviet Union no longer existed. Eight more republics

joined their declaration shortly thereafter. Gorbachev resigned in December 1991 and what was left of the

Soviet parliament voted to end itself.

The process began with growing unrest in the Union's various constituent national republics developing into an

incessant political and legislative conflict between them and the central government.

Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

was the first Soviet republic to declare state sovereignty inside the Union on 16 November 1988.

Lithuania was the first republic to declare full independence restored from the Soviet Union by the

Act of 11 March 1990 with its

Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

neighbours and the

Southern Caucasus

The South Caucasus, also known as Transcaucasia or the Transcaucasus, is a geographical region on the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, straddling the southern Caucasus Mountains. The South Caucasus roughly corresponds to modern Arme ...

republic of

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

joining it in a course of two months.

In August 1991, communist hardliners and military elites tried to overthrow Gorbachev and stop the failing reforms in

a coup, but failed. The turmoil led to the government in Moscow losing most of its influence, and many republics proclaiming independence in the following days and months. The secession of the Baltic states was recognized in September 1991. The Belovezh Accords were signed on 8 December by

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin ( rus, Борис Николаевич Ельцин, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtsɨn, a=Ru-Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin.ogg; 1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician wh ...

of

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

,

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Kravchuk of

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

, and

Chairman Shushkevich of

Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

, recognising each other's independence and creating the

Commonwealth of Independent States

The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) is a regional intergovernmental organization in Eurasia. It was formed following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. It covers an area of and has an estimated population of 239,796,010. ...

(CIS) to replace the Soviet Union.

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

was the last republic to leave the Union, proclaiming independence on 16 December. All the ex-Soviet republics, with the exception of Georgia and the Baltic states, joined the CIS on 21 December, signing the

Alma-Ata Protocol. On 25 December, Gorbachev resigned and turned over his presidential powers—including control of the

nuclear launch codes—to Yeltsin, who was now the first president of the

Russian Federation

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

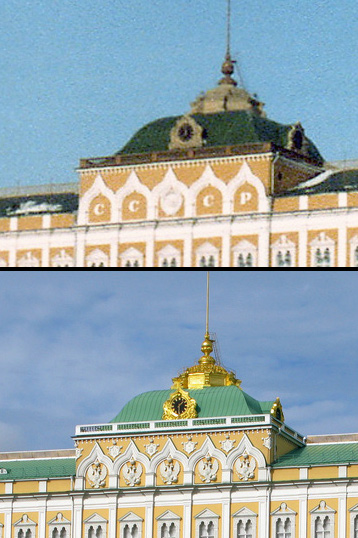

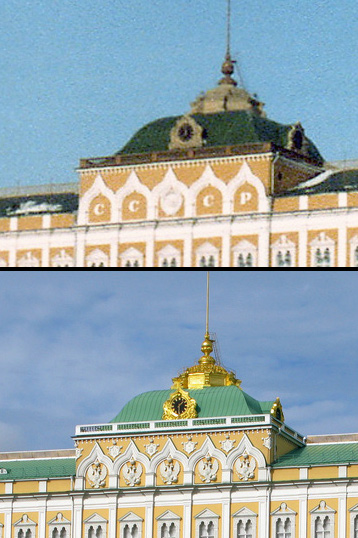

. That evening, the

Soviet flag

The State Flag of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (), commonly known as the Soviet flag (), was the official state flag of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) from 1922 to 1991. The flag's design and symbolism are derived from ...

was lowered from the

Kremlin and replaced with the

Russian tricolour flag. The following day, the

Supreme Soviet of the USSR

The Supreme Soviet of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics ( rus, Верховный Совет Союза Советских Социалистических Республик, r=Verkhovnyy Sovet Soyuza Sovetskikh Sotsialisticheskikh Respubl ...

's upper chamber, the Soviet of the Republics

formally dissolved the Union.

[ Declaration № 142-Н of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, formally establishing the dissolution of the Soviet Union as a state and subject of international law.]

In the

aftermath of the Cold War, several of the

former Soviet republics

The post-Soviet states, also known as the former Soviet Union (FSU), the former Soviet Republics and in Russia as the near abroad (russian: links=no, ближнее зарубежье, blizhneye zarubezhye), are the 15 sovereign states that wer ...

have retained close links with Russia and formed

multilateral organizations such as the CIS, the

Collective Security Treaty Organization

The Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) is an intergovernmental military alliance in Eurasia consisting of six post-Soviet states: Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Tajikistan. The Collective Security Treaty has ...

(CSTO), the

Eurasian Economic Union

The Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU or EEU)EAEU is the acronym used on thorganisation's website However, many media outlets use the acronym EEU. is an economic union of some post-Soviet states located in Eurasia. The Treaty on the Eurasian Econo ...

(EAEU), and the

Union State

The Union State,; be, Саю́зная дзяржа́ва Расі́і і Белару́сі, Sajuznaja dziaržava Rasii i Bielarusi, links=no. or Union State of Russia and Belarus,; be, Саю́зная дзяржа́ва, Sajuznaja dziar� ...

, for economic and military cooperation. On the other hand, the Baltic states and most of the former

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist repub ...

states became part of the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

and joined

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

, while some of the other former Soviet republics like Ukraine, Georgia and

Moldova

Moldova ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Moldova ( ro, Republica Moldova), is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. The unrecognised state of Transnistr ...

have been publicly expressing interest in following the same path since the 1990s.

Background

1985: Gorbachev elected

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Gorbachev was elected

General Secretary by the

Politburo on 11 March 1985, just over four hours after his predecessor

Konstantin Chernenko

Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko uk, Костянтин Устинович Черненко, translit=Kostiantyn Ustynovych Chernenko (24 September 1911 – 10 March 1985) was a Soviet politician and the seventh General Secretary of the Commu ...

died at the age of 73. Gorbachev, aged 54, was the youngest member of the Politburo. His initial goal as general secretary was to revive the stagnating

Soviet economy

The economy of the Soviet Union was based on state ownership of the means of production, collective farming, and industrial manufacturing. An administrative-command system managed a distinctive form of central planning. The Soviet economy was ...

, and he realized that doing so would require reforming underlying political and social structures. The reforms began with personnel changes of senior

Brezhnev-era officials who would impede political and economic change. On 23 April 1985, Gorbachev brought two protégés,

Yegor Ligachev

Yegor Kuzmich Ligachyov (also transliterated as Ligachev; russian: Егор Кузьмич Лигачёв, link=no; 29 November 1920 – 7 May 2021) was a Soviet and Russian politician who was a high-ranking official in the Communist Party ...

and

Nikolai Ryzhkov

Nikolai Ivanovich Ryzhkov ( uk, Микола Іванович Рижков; russian: Николай Иванович Рыжков; born 28 September 1929) is a Soviet, and later Russian, politician. He served as the last Chairman of the Coun ...

, into the Politburo as full members. He kept the "power" ministries favorable by promoting KGB Chief

Viktor Chebrikov from candidate to full member and appointing Minister of Defence Marshal

Sergei Sokolov as a Politburo candidate.

That

liberalization

Liberalization or liberalisation (British English) is a broad term that refers to the practice of making laws, systems, or opinions less severe, usually in the sense of eliminating certain government regulations or restrictions. The term is used m ...

, however, fostered

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

movements and ethnic disputes within the Soviet Union. It also led indirectly to the

revolutions of 1989

The Revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, was a revolutionary wave that resulted in the end of most communist states in the world. Sometimes this revolutionary wave is also called the Fall of Nations or the Autumn of Nat ...

in which Soviet-imposed socialist regimes of the

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist repub ...

were toppled peacefully (

with the notable exception of Romania), which in turn increased pressure on Gorbachev to introduce greater democracy and autonomy for the Soviet Union's constituent republics. Under Gorbachev's leadership, the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in 1989 introduced limited competitive elections to a new central legislature, the

Congress of People's Deputies (although the ban on other political parties was not lifted until 1990).

On 1 July 1985, Gorbachev sidelined his main rival by removing

Grigory Romanov from the Politburo and brought

Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin ( rus, Борис Николаевич Ельцин, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtsɨn, a=Ru-Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin.ogg; 1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician wh ...

into the

Central Committee Secretariat. On 23 December 1985, Gorbachev appointed Yeltsin

First Secretary of the Moscow Communist Party

The First Secretary of the Moscow City Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, was the position of highest authority in the city of Moscow roughly equating to that of mayor. The position was created on November 10, 1917, following t ...

replacing

Viktor Grishin

Viktor Vasilyevich Grishin (russian: Ви́ктор Васи́льевич Гри́шин; – 25 May 1992) was a Soviet politician. He was a candidate (1961–1971) and full member (1971–1986) of the Politburo of the Central Committee of ...

.

1986: Sakharov returns

Gorbachev continued to press for greater

liberalisation

Liberalization or liberalisation (British English) is a broad term that refers to the practice of making laws, systems, or opinions less severe, usually in the sense of eliminating certain government regulations or restrictions. The term is used m ...

. On 23 December 1986, the most prominent

Soviet dissident

Soviet dissidents were people who disagreed with certain features of Soviet ideology or with its entirety and who were willing to speak out against them. The term ''dissident'' was used in the Soviet Union in the period from the mid-1960s until ...

,

Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov ( rus, Андрей Дмитриевич Сахаров, p=ɐnˈdrʲej ˈdmʲitrʲɪjevʲɪtɕ ˈsaxərəf; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident, nobel laureate and activist for n ...

, returned to Moscow shortly after receiving a personal telephone call from Gorbachev telling him that after almost seven years his internal

exile for defying the authorities was over.

1987: One-party democracy

At the 28–30 January 1987, Central Committee

plenum

Plenum may refer to:

* Plenum chamber, a chamber intended to contain air, gas, or liquid at positive pressure

* Plenism, or ''Horror vacui'' (physics) the concept that "nature abhors a vacuum"

* Plenum (meeting), a meeting of a deliberative asse ...

, Gorbachev suggested a new policy of

''demokratizatsiya'' throughout Soviet society. He proposed that future Communist Party elections should offer a choice between multiple candidates, elected by secret ballot. However, the party delegates at the Plenum watered down Gorbachev's proposal, and democratic choice within the Communist Party was never significantly implemented.

Gorbachev also radically expanded the scope of ''

glasnost'' and stated that no subject was off limits for open discussion in the media.

On 7 February 1987, dozens of political prisoners were freed in the first group release since the

Khrushchev Thaw in the mid-1950s.

On 10 September 1987,

Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin ( rus, Борис Николаевич Ельцин, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtsɨn, a=Ru-Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin.ogg; 1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician wh ...

wrote a letter of resignation to Gorbachev. At the 27 October 1987, plenary meeting of the Central Committee, Yeltsin, frustrated that Gorbachev had not addressed any of the issues outlined in his resignation letter, criticized the slow pace of reform and servility to the general secretary.

[Conor O'Clery, ''Moscow 25 December 1991: The Last Day of the Soviet Union''. Transworld Ireland (2011). , p. 74] In his reply, Gorbachev accused Yeltsin of "political immaturity" and "absolute irresponsibility". Nevertheless, news of Yeltsin's insubordination and "secret speech" spread, and soon ''

samizdat

Samizdat (russian: самиздат, lit=self-publishing, links=no) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the document ...

'' versions began to circulate. That marked the beginning of Yeltsin's rebranding as a rebel and rise in popularity as an anti-establishment figure. The following four years of political struggle between Yeltsin and Gorbachev played a large role in the dissolution of the Soviet Union. On 11 November 1987, Yeltsin was fired from the post of

First Secretary of the Moscow Communist Party

The First Secretary of the Moscow City Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, was the position of highest authority in the city of Moscow roughly equating to that of mayor. The position was created on November 10, 1917, following t ...

.

Protest activity

In the years leading up to the dissolution, various protests and resistance movements occurred or took hold throughout the Soviet Union, which were variously suppressed or tolerated.

The CTAG ( lv, Cilvēktiesību aizstāvības grupa, lit=Human Rights Defense Group, label=)

Helsinki-86 was founded in July 1986 in the

Latvian port town of

Liepāja

Liepāja (; liv, Līepõ; see other names) is a state city in western Latvia, located on the Baltic Sea. It is the largest-city in the Kurzeme Region and the third-largest city in the country after Riga and Daugavpils. It is an important ice-f ...

. Helsinki-86 was the first openly

anti-Communist organization in the U.S.S.R., and the first openly organized opposition to the Soviet regime, setting an example for other ethnic minorities' pro-independence movements.

On 26 December 1986, 300 Latvian youths gathered in Riga's Cathedral Square and marched down Lenin Avenue toward the

Freedom Monument

The Freedom Monument ( lv, Brīvības piemineklis, ) is located in Riga, Latvia, honouring soldiers killed during the Latvian War of Independence (1918–1920). It is considered an important symbol of the freedom, independence, and sovereignty ...

, shouting, "Soviet Russia out! Free Latvia!" Security forces confronted the marchers, and several police vehicles were overturned.

The ''

Jeltoqsan

, partof = Dissolution of the Soviet Union

, image =

, caption =

, date = 16–19 December 1986

, place = Alma-Ata, Kazakh SSR, Soviet Union

, coordinates =

, map_type =

, latitude =

, longitude =

, ...

'' ('December') of 1986 were riots in

Alma-Ata

Almaty (; kk, Алматы; ), formerly known as Alma-Ata ( kk, Алма-Ата), is the largest city in Kazakhstan, with a population of about 2 million. It was the capital of Kazakhstan from 1929 to 1936 as an autonomous republic as part of t ...

,

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

, sparked by Gorbachev's dismissal of

Dinmukhamed Kunaev

Dinmukhamed Akhmetuly "Dimash" Kunaev (also spelled Kunayev; kk, Дінмұхаммед (Димаш) Ахметұлы Қонаев, Dınmūhammed (Dimaş) Ahmetūly Qonaev, russian: Динмухаме́д Ахме́дович (Минлиахме ...

, the First Secretary of the

Communist Party of Kazakhstan

The Communist Party of Kazakhstan ( kk, Қазақстан Коммунистік партиясы, ''Qazaqstan Kommunistık Partiasy'', QKP; russian: Коммунистическая партия Казахстана) is a banned political pa ...

and an

ethnic Kazakh, who was replaced with

Gennady Kolbin

Gennady Vasilyevich Kolbin (; 7 May 1927 – 15 January 1998) was the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Kazakh SSR from 16 December 1986 to 22 June 1989.

Early life

Kolbin was born in 1927 in Nizhny Tagil. Fr ...

, an outsider from the

Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

. Demonstrations started in the morning of 17 December 1986, with 200 to 300 students in front of the Central Committee building on

Brezhnev Square

Republic Square ( kz, Республика Алаңы, ''Respublika Alañy'', russian: Площадь Республики), also known as Independence Square or New Square is the main square in Almaty, Kazakhstan. It is used for public events. T ...

. On the next day, 18 December, protests turned into civil unrest as clashes between troops, volunteers, militia units, and Kazakh students turned into a wide-scale confrontation. The clashes could only be controlled on the third day.

On 6 May 1987,

Pamyat

The Pamyat Society (russian: Общество «Память», russian: Obshchestvo «Pamyat», ; English language, English translation: "''Memory''" Society), officially National Patriotic Front "Memory" (NPF "Memory"; russian: Национал� ...

, a Russian nationalist group, held an unsanctioned demonstration in Moscow. The authorities did not break up the demonstration and even kept traffic out of the demonstrators' way while they marched to an impromptu meeting with Boris Yeltsin.

On 25 July 1987, 300

Crimean Tatars

, flag = Flag of the Crimean Tatar people.svg

, flag_caption = Flag of Crimean Tatars

, image = Love, Peace, Traditions.jpg

, caption = Crimean Tatars in traditional clothing in front of the Khan's Palace ...

staged a noisy demonstration near the

Kremlin Wall

The Moscow Kremlin Wall is a defensive wall that surrounds the Moscow Kremlin, recognisable by the characteristic notches and its Kremlin towers. The original walls were likely a simple wooden fence with guard towers built in 1156.

The Kremlin w ...

for several hours, calling for the right to return to their homeland, from which they were

deported

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. The term ''expulsion'' is often used as a synonym for deportation, though expulsion is more often used in the context of international law, while deportation ...

in 1944; police and soldiers looked on.

On 23 August 1987, the 48th anniversary of the secret protocols of the 1939

Molotov Pact

Molotov may refer to:

* Vyacheslav Molotov (1890–1986), Soviet politician and diplomat, and foreign minister under Joseph Stalin

* Molotov cocktail, hand-held incendiary weapon

Arts and entertainment

*Molotov (band), a Mexican rock/rap band

...

, thousands of demonstrators marked the occasion in the three Baltic capitals to sing independence songs and attend speeches commemorating Stalin's victims. The gatherings were sharply denounced in the official press and closely watched by the police but were not interrupted.

On 14 June 1987, about 5,000 people gathered again at Freedom Monument in

Riga, and laid flowers to commemorate the anniversary of

Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

's

mass deportation

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. The term ''expulsion'' is often used as a synonym for deportation, though expulsion is more often used in the context of international law, while deportation ...

of Latvians in 1941. The authorities did not crack down on demonstrators, which encouraged more and larger demonstrations throughout the Baltic States. On 18 November 1987, hundreds of police and civilian militiamen cordoned off the central square to prevent any demonstration at Freedom Monument, but thousands lined the streets of Riga in silent protest regardless.

On 17 October 1987, about 3,000 Armenians demonstrated in

Yerevan

Yerevan ( , , hy, Երևան , sometimes spelled Erevan) is the capital and largest city of Armenia and one of the world's oldest continuously inhabited cities. Situated along the Hrazdan River, Yerevan is the administrative, cultural, and i ...

complaining about the condition of

Lake Sevan

Lake Sevan ( hy, Սևանա լիճ, Sevana lich) is the largest body of water in both Armenia and the Caucasus region. It is one of the largest freshwater high-altitude (alpine) lakes in Eurasia. The lake is situated in Gegharkunik Province, ...

, the Nairit chemicals plant, and the

Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant

The Armenian Nuclear Power Plant (ANPP) (), also known as the Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant, (Armenian: Մեծամորի ատոմային էլեկտրակայան) is the only nuclear power plant in the South Caucasus, located 36 kilometers west o ...

, and air pollution in Yerevan. Police tried to prevent the protest but took no action to stop it once the march was underway.

The following day 1,000 Armenians participated in another demonstration calling for Armenian national rights in

Karabakh

Karabakh ( az, Qarabağ ; hy, Ղարաբաղ, Ġarabaġ ) is a geographic region in present-day southwestern Azerbaijan and eastern Armenia, extending from the highlands of the Lesser Caucasus down to the lowlands between the rivers Kura and ...

and the annexation of

Nakhchivan and

Nagorno-Karabakh

Nagorno-Karabakh ( ) is a landlocked region in the South Caucasus, within the mountainous range of Karabakh, lying between Lower Karabakh and Syunik, and covering the southeastern range of the Lesser Caucasus mountains. The region is m ...

to Armenia. The police tried to physically prevent the march and after a few incidents, dispersed the demonstrators.

Timeline

1988

Moscow loses control

In 1988, Gorbachev started to lose control of two regions of the Soviet Union, as the Baltic republics were now leaning towards independence, and the Caucasus descended into violence and civil war.

On 1 July 1988, the fourth and last day of a bruising 19th Party Conference, Gorbachev won the backing of the tired delegates for his last-minute proposal to create a new supreme legislative body called the

Congress of People's Deputies. Frustrated by the old guard's resistance, Gorbachev embarked on a set of constitutional changes to attempt separation of party and state, thereby isolating his conservative Party opponents. Detailed proposals for the new Congress of People's Deputies were published on 2 October 1988, and to enable the creation of the new legislature. The Supreme Soviet, during its 29 November – 1 December 1988, session, implemented amendments to the

1977 Soviet Constitution, enacted a law on electoral reform, and set the date of the election for 26 March 1989.

On 29 November 1988, the Soviet Union ceased to

jam

Jam is a type of fruit preserve.

Jam or Jammed may also refer to:

Other common meanings

* A firearm malfunction

* Block signals

** Radio jamming

** Radar jamming and deception

** Mobile phone jammer

** Echolocation jamming

Arts and ente ...

all foreign radio stations, allowing Soviet citizens – for the first time since a brief period in the 1960s – to have unrestricted access to news sources beyond Communist Party control.

Baltic republics

In 1986 and 1987, Latvia had been in the vanguard of the Baltic states in pressing for reform. In 1988 Estonia took over the lead role with the foundation of the Soviet Union's first popular front and starting to influence state policy.

The

Estonian Popular Front was founded in April 1988. On 16 June 1988, Gorbachev replaced

Karl Vaino

Karl Genrikhovich Vaino ( et, Karl Vaino; russian: Карл Генрихович Вайно; ''alias'' Kirill Voinov; 28 May 1923 – 12 February 2022) was an Estonian SSR politician. From 1978 to 1988 he served as the First Secretary of the ...

, the "old guard" leader of the

Communist Party of Estonia

The Communist Party of Estonia ( et, Eestimaa Kommunistlik Partei, abbreviated EKP) was a subdivision of the Soviet communist party which in 1920-1940 operated illegally in Estonia and, after the 1940 occupation and annexation of Estonia by the ...

, with the comparatively liberal

Vaino Väljas

Vaino Väljas (; born 28 March 1931 in Külaküla, Hiiumaa) is a former Soviet and Estonian politician. He was the Chairman of the 6th Supreme Soviet of the Estonian SSR from 18 April 1963 to 19 March 1967, first secretary of communist party o ...

. In late June 1988, Väljas bowed to pressure from the Estonian Popular Front and legalized the flying of the old blue-black-white flag of Estonia, and agreed to a new state language law that made Estonian the official language of the Republic.

On 2 October, the Popular Front formally launched its political platform at a two-day congress. Väljas attended, gambling that the front could help Estonia become a model of economic and political revival, while moderating separatist and other radical tendencies. On 16 November 1988, the Supreme Soviet of the Estonian SSR adopted a declaration of national sovereignty under which Estonian laws would take precedence over those of the Soviet Union. Estonia's parliament also laid claim to the republic's natural resources including land, inland waters, forests, mineral deposits, and to the means of industrial production, agriculture, construction, state banks, transportation, and municipal services within the territory of Estonia's borders. At the same time the

Estonian Citizens' Committees started registration of citizens of the

Republic of Estonia to carry out the elections of the

Congress of Estonia

The Congress of Estonia ( Estonian: ''Eesti Kongress'') was an innovative grassroots parliament established in Estonia in 1990–1992 as a part of the process of regaining of independence from the Soviet Union. It also challenged the power and au ...

.

The

Latvian Popular Front

The Popular Front of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Tautas fronte) was a political organisation in Latvia in the late 1980s and early 1990s which led Latvia to its independence from the Soviet Union. It was similar to the Popular Front of Estonia and the ...

was founded in June 1988. On 4 October, Gorbachev replaced

Boris Pugo

Boris Karlovich Pugo, OAN ( lv, Boriss Pugo, russian: Борис Карлович Пуго; 19 February 1937 – 22 August 1991) was a Soviet Communist politician of Latvian origin.

Biography Early life and education

Pugo was born in Kalinin, ...

, the "old guard" leader of the

Communist Party of Latvia

The Communist Party of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Komunistiskā partija, LKP) was a political party in Latvia.

History Latvian Social-Democracy prior to 1919

The party was founded at a congress in June 1904. Initially the party was known as the Latvia ...

, with the more liberal Jānis Vagris. In October 1988 Vagris bowed to pressure from the Latvian Popular Front and legalized flying the former carmine red-and-white flag of independent Latvia, and on 6 October he passed a law making

Latvian the country's official language.

The Popular Front of Lithuania, called

Sąjūdis

Sąjūdis (, "Movement"), initially known as the Reform Movement of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Persitvarkymo Sąjūdis), is the political organisation which led the struggle for Lithuanian independence in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It was es ...

("Movement"), was founded in May 1988. On 19 October 1988, Gorbachev replaced

Ringaudas Songaila

Ringaudas Bronislovas Songaila (20 April 1929 – 25 June 2019) was an official of the Lithuanian SSR nomenclatura. In 1987–1988, he was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Lithuania or the ''de facto'' head of state.

Biography

Song ...

, the "old guard" leader of the

Communist Party of Lithuania

The Communist Party of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos komunistų partija; russian: Коммунистическая партия Литвы) is a banned communist party in Lithuania. The party was established in early October 1918 and operated clan ...

, with the relatively liberal

Algirdas Mykolas Brazauskas

Algirdas Mykolas Brazauskas (, 1932 – 2010) was the first President (fourth overall) of a newly re-independent post-Soviet Lithuania from 1993 to 1998 and Prime Minister from 2001 to 2006.

He also served as head of the Communist Party of Li ...

. In October 1988, Brazauskas bowed to pressure from Sąjūdis and legalized the flying of the historic yellow-green-red flag of independent Lithuania and in November 1988, he passed a law making

Lithuanian the country's official language; also, the former national anthem,

Tautiška giesmė

"" (; literally "The National Hymn") is the national anthem of Lithuania, also known by its opening words, "" (official translation of the lyrics: "Lithuania, Our Homeland", literally: "Lithuania, Our Fatherland"), and as "" ("The National Anthem ...

, was later reinstated.

Rebellion in the Caucasus

On 20 February 1988, after a week of growing demonstrations in

Stepanakert, capital of the

Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast

The Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO), DQMV, hy, Լեռնային Ղարաբաղի Ինքնավար Մարզ, ԼՂԻՄ was an autonomous oblast within the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic that was created on July 7, 1923. Its cap ...

(the Armenian majority area within the

Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic), the Regional Soviet voted to secede and join with the

Soviet Socialist Republic of Armenia. This local vote in a small, remote part of the Soviet Union made headlines around the world; it was an unprecedented defiance of republican and national authorities. On 22 February 1988, in what became known as the "

Askeran clash", thousands of Azerbaijanis marched towards Nagorno-Karabakh, demanding information about rumors of an Azerbaijani having been killed in Stepanakert. They were informed that no such incident had occurred, but refused to believe it. Dissatisfied with what they were told, thousands began marching toward Nagorno-Karabakh, killing 50. Karabakh authorities mobilised over a thousand police to stop the march, with the resulting clashes leaving two Azerbaijanis dead. These deaths, announced on state radio, led to the

Sumgait Pogrom. Between 26 February and 1 March, the city of

Sumgait

Sumgait (; az, Sumqayıt, ) is a city in Azerbaijan, located near the Caspian Sea, on the Absheron Peninsula, about away from the capital Baku. The city has a population of around 345,300, making it the second largest city in Azerbaijan after Ba ...

(Azerbaijan) saw violent anti-Armenian rioting during which at least 32 people were killed. The authorities totally lost control and occupied the city with paratroopers and tanks; nearly all of the 14,000 Armenian residents of Sumgait fled.

Gorbachev refused to make any changes to the status of Nagorno-Karabakh, which remained part of Azerbaijan. He instead sacked the Communist Party Leaders in both Republics – on 21 May 1988,

Kamran Baghirov

Kamran Baghirov Mammad oglu ( az, Камран Бағиров Мәммәд оғлу, italic=no, Kamran Bağirov Məmməd oğlu; January 24, 1933 – October 25, 2000), was the 12th First Secretary of Azerbaijan Communist Party.

Biography

Fro ...

was replaced by

Abdulrahman Vezirov

Abdurrahman Vazirov Khalil oglu ( az, Әбдүррәһман Вәзиров Хәлил оғлу, italic=no, Əbdürrəhman Vəzirov Xəlil oğlu; 26 May 1930 – 10 January 2022) was the 13th First Secretary of the Azerbaijan Communist Party an ...

as First Secretary of the

Azerbaijan Communist Party

The Azerbaijan Communist Party ( az, Azərbaycan Kommunist Partiyası; russian: Коммунистическая партия Азербайджана) was the ruling political party in the Azerbaijan SSR, making it effectively a branch of th ...

. From 23 July to September 1988, a group of Azerbaijani intellectuals began working for a new organization called the

Popular Front of Azerbaijan

The Azerbaijani Popular Front Party (APFP; az, Azərbaycan Xalq Cəbhəsi Partiyası, ) is a political party in Azerbaijan, founded in 1992 by Abulfaz Elchibey. After Elchibey's death in 2000, the party split into two wings, the ''reform'' win ...

, loosely based on the

Estonian Popular Front. On 17 September, when gun battles broke out between the Armenians and Azerbaijanis near

Stepanakert, two soldiers were killed and more than two dozen injured. This led to almost tit-for-tat ethnic polarization in Nagorno-Karabakh's two main towns: the Azerbaijani minority was expelled from

Stepanakert, and the Armenian minority was expelled from

Shusha

/ hy, Շուշի

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline = ShushaCollection2021.jpg

, image_caption = Landmarks of Shusha, from top left:Ghazanchetsots Cathedral • Yukhari Govha ...

. On 17 November 1988, in response to the exodus of tens of thousands of Azerbaijanis from Armenia, a series of mass demonstrations began in

Baku's Lenin Square, lasting 18 days and attracting half a million demonstrators in support of their compatriots in that region. On 5 December 1988, the Soviet police and civilian militiamen moved in, cleared the square by force, and imposed a curfew that lasted ten months.

The rebellion of fellow Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh had an immediate effect in Armenia itself. Daily demonstrations, which began in the Armenian capital

Yerevan

Yerevan ( , , hy, Երևան , sometimes spelled Erevan) is the capital and largest city of Armenia and one of the world's oldest continuously inhabited cities. Situated along the Hrazdan River, Yerevan is the administrative, cultural, and i ...

on 18 February, initially attracted few people, but each day the Nagorno-Karabakh issue became increasingly prominent and the numbers swelled. On 20 February, a 30,000-strong crowd demonstrated in the

Theater Square, by 22 February, there were 100,000, the next day 300,000, and a transport strike was declared, by 25 February, there were close to a million demonstrators—more than a quarter of Armenia's population. This was the first of the large, peaceful public demonstrations that would become a feature of communism's overthrow in Prague, Berlin, and, ultimately, Moscow. Leading Armenian intellectuals and nationalists, including the future first president of independent Armenia

Levon Ter-Petrossian

Levon Hakobi Ter-Petrosyan ( hy, Լևոն Հակոբի Տեր-Պետրոսյան; born 9 January 1945), also known by his initials LTP, is an Armenian politician who served as the first president of Armenia from 1991 until his resignation in 1998 ...

, formed the eleven-member

Karabakh Committee

Karabakh Committee ( hy, Ղարաբաղ կոմիտե) was a group of Armenian intellectuals recognized by many Armenians as the ''de facto'' leaders in the late 1980s. The Committee was formed in 1988, with the stated objective of reunification of ...

to lead and organize the new movement.

On the same day, when Gorbachev replaced Baghirov by Vezirov as First Secretary of the Azerbaijan Communist Party, he also replaced

Karen Demirchian by Suren Harutyunyan as First Secretary of the

Communist Party of Armenia. However, Harutyunyan quickly decided to run before the nationalist wind and on 28 May, allowed Armenians to unfurl the red-blue-orange

First Armenian Republic flag for the first time in almost 70 years to mark the 1918 declaration of the First Republic. On 15 June 1988, the Armenian Supreme Soviet adopted a resolution formally approving the idea of Nagorno-Karabakh's unification as part of the republic. Armenia, formerly one of the most loyal Republics, had suddenly turned into the leading rebel republic. On 5 July 1988, when a contingent of troops was sent in to remove demonstrators by force from Yerevan's

Zvartnots International Airport

Zvartnots International Airport ( hy, Զվարթնոց միջազգային օդանավակայան, translit=Zvart'nots' mijazgayin ōdanavakayan) is located near Zvartnots, west of Yerevan, the capital city of Armenia. It acts as the main ...

, shots were fired and one student protester was killed. In September, further large demonstrations in Yerevan led to the deployment of armored vehicles. In the autumn of 1988 almost all of the 200,000 Azerbaijani minority in Armenia was expelled by Armenian nationalists, with over 100 killed in the process. That, after the

Sumgait pogrom earlier that year, which had been carried out by Azerbaijanis to ethnic Armenians and led to the expulsion of Armenians from Azerbaijan, was for many Armenians considered an act of revenge for the killings at Sumgait. On 25 November 1988, a military commandant took control of Yerevan as the Soviet government moved to prevent further ethnic violence.

On 7 December 1988, the

Spitak earthquake struck, killing an estimated 25,000 to 50,000 people. When Gorbachev rushed back from a visit to the United States, he was so angered with being confronted by protesters calling for Nagorno-Karabakh to be made part of the Armenian Republic during a natural disaster that on 11 December 1988, he ordered for the entire

Karabakh Committee

Karabakh Committee ( hy, Ղարաբաղ կոմիտե) was a group of Armenian intellectuals recognized by many Armenians as the ''de facto'' leaders in the late 1980s. The Committee was formed in 1988, with the stated objective of reunification of ...

to be arrested.

In

Tbilisi

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Kura River with a population of approximately 1.5 million p ...

, the capital of

Soviet Georgia

The Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (Georgian SSR; ka, საქართველოს საბჭოთა სოციალისტური რესპუბლიკა, tr; russian: Грузинская Советская Соц� ...

, many demonstrators camped out in front of the republic's legislature in November 1988 calling for Georgia's independence and in support of Estonia's declaration of sovereignty.

Western republics

Beginning in February 1988, the Democratic Movement of

Moldova

Moldova ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Moldova ( ro, Republica Moldova), is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. The unrecognised state of Transnistr ...

(formerly Moldavia) organized public meetings, demonstrations, and song festivals, which gradually grew in size and intensity. In the streets, the center of public manifestations was the

Stephen the Great Monument in Chişinău, and the adjacent park harboring ''Aleea Clasicilor'' (The "

Alley of Classics f Literature). On 15 January 1988, in a tribute to

Mihai Eminescu

Mihai Eminescu (; born Mihail Eminovici; 15 January 1850 – 15 June 1889) was a Romanian Romantic poet from Moldavia, novelist, and journalist, generally regarded as the most famous and influential Romanian poet. Eminescu was an active memb ...

at his bust on the Aleea Clasicilor,

Anatol Şalaru

Anatol is a masculine given name, derived from the Greek name Ἀνατόλιος ''Anatolius'', meaning "sunrise".

The Russian version of the name is Anatoly (also transliterated as Anatoliy and Anatoli). The French version is Anatole. A rare ...

submitted a proposal to continue the meetings. In the public discourse, the movement called for national awakening, freedom of speech, the revival of Moldovan traditions, and for the attainment of official status for the

Romanian language

Romanian (obsolete spellings: Rumanian or Roumanian; autonym: ''limba română'' , or ''românește'', ) is the official and main language of Romania and the Republic of Moldova. As a minority language it is spoken by stable communities in ...

and return to the Latin alphabet. The transition from "movement" (an informal association) to "front" (a formal association) was seen as a natural "upgrade" once a movement gained momentum with the public, and the Soviet authorities no longer dared to crack down on it.

On 26 April 1988, about 500 people participated in a march organized by the Ukrainian Cultural Club on Kyiv's

Khreschatyk

Khreshchatyk ( uk, Хрещатик, ) is the main street of Kyiv, Ukraine. The street has a length of . It stretches from the European Square (northeast) through the Maidan and to Bessarabska Square (southwest) where the Besarabsky Market ...

Street to mark the second anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, carrying placards with slogans like "Openness and Democracy to the End". Between May and June 1988,

Ukrainian Catholics in western Ukraine celebrated the Millennium of Christianity in

Kyivan Rus

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas of ...

in secret by holding services in the forests of Buniv,

Kalush, Hoshi, and Zarvanytsia. On 5 June 1988, as the official celebrations of the Millennium were held in Moscow, the Ukrainian Cultural Club hosted its own observances in Kyiv at the monument to

St. Volodymyr the Great

Vladimir I Sviatoslavich or Volodymyr I Sviatoslavych ( orv, Володимѣръ Свѧтославичь, ''Volodiměrъ Svętoslavičь'';, ''Uladzimir'', russian: Владимир, ''Vladimir'', uk, Володимир, ''Volodymyr''. Se ...

, the grand prince of

Kyivan Rus

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas of ...

.

On 16 June 1988, 6,000 to 8,000 people gathered in Lviv to hear speakers declare no confidence in the local list of delegates to the 19th Communist Party conference, to begin on 29 June. On 21 June, a rally in Lviv attracted 50,000 people who had heard about a revised delegate list. Authorities attempted to disperse the rally in front of Druzhba Stadium. On 7 July, 10,000 to 20,000 people witnessed the launch of the Democratic Front to Promote Perestroika. On 17 July, a group of 10,000 gathered in the village

Zarvanytsia for Millennium services celebrated by Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Bishop Pavlo Vasylyk. The militia tried to disperse attendees, but it turned out to be the largest gathering of Ukrainian Catholics since Stalin outlawed the Church in 1946. On 4 August, which came to be known as "Bloody Thursday", local authorities violently suppressed a demonstration organized by the Democratic Front to Promote Perestroika. Forty-one people were detained, fined, or sentenced to 15 days of administrative arrest. On 1 September, local authorities violently displaced 5,000 students at a public meeting lacking official permission at

Ivan Franko State University.

On 13 November 1988, approximately 10,000 people attended an officially sanctioned meeting organized by the cultural heritage organization ''Spadschyna'', the

Kyiv University

Kyiv University or Shevchenko University or officially the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv ( uk, Київський національний університет імені Тараса Шевченка), colloquially known as KNU ...

student club ''

Hromada'', and the environmental groups ''Zelenyi Svit'' ("Green World") and ''Noosfera'', to focus on ecological issues. From 14–18 November, 15 Ukrainian activists were among the 100 human-, national- and religious-rights advocates invited to discuss human rights with Soviet officials and a visiting delegation of the U.S. Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (also known as the Helsinki Commission). On 10 December, hundreds gathered in Kyiv to observe

International Human Rights Day

Human Rights Day is celebrated annually around the world on 10 December every year.

The date was chosen to honor the United Nations General Assembly's adoption and proclamation, on 10 December 1948, of the Universal Declaration of Human Right ...

at a rally organized by the Democratic Union. The unauthorized gathering resulted in the detention of local activists.

The

Belarusian Popular Front

The Belarusian Popular Front "Revival" (BPF, be, Беларускі Народны Фронт "Адраджэньне", БНФ; ''Biełaruski Narodny Front "Adradžeńnie"'', ''BNF'') was a social and political movement in Belarus in the late 1 ...

was established in 1988 as a political party and cultural movement for democracy and independence, similar to the Baltic republics' popular fronts. The discovery of mass graves in

Kurapaty

Kurapaty ( be, Курапаты, ) is a wooded area on the outskirts of Minsk, Belarus, in which a vast number of people were executed between 1937 and 1941 during the Great Purge by the Soviet secret police, the NKVD.

The exact count of victi ...

outside

Minsk

Minsk ( be, Мінск ; russian: Минск) is the capital and the largest city of Belarus, located on the Svislach and the now subterranean Niamiha rivers. As the capital, Minsk has a special administrative status in Belarus and is the admi ...

by historian

Zianon Pazniak

Zianon Stanislavavič Pazniak ( be, Зянон Станіслававіч Пазняк, born 24 April 1944) is a Belarusian nationalist politician, one of the founders of the Belarusian Popular Front and leader of the Conservative Christian ...

, the Belarusian Popular Front's first leader, gave additional momentum to the pro-democracy and pro-independence movement in Belarus. It claimed that the

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

performed secret killings in Kurapaty. Initially the Front had significant visibility because its numerous public actions almost always ended in clashes with the police and the

KGB

The KGB (russian: links=no, lit=Committee for State Security, Комитет государственной безопасности (КГБ), a=ru-KGB.ogg, p=kəmʲɪˈtʲet ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əj bʲɪzɐˈpasnəsʲtʲɪ, Komitet gosud ...

.

1989

Moscow: limited democratization

Spring 1989 saw the people of the Soviet Union exercising a democratic choice, albeit limited, for the first time since 1917, when they elected the new Congress of People's Deputies. Just as important was the uncensored live TV coverage of the legislature's deliberations, where people witnessed the previously feared Communist leadership being questioned and held accountable. This example fueled a limited experiment with democracy in

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, which quickly led to the toppling of the Communist government in Warsaw that summer – which in turn sparked uprisings that overthrew governments in the other five Warsaw Pact countries before the end of 1989, the year the Berlin Wall fell.

This was also the year that

CNN

CNN (Cable News Network) is a multinational cable news channel headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. Founded in 1980 by American media proprietor Ted Turner and Reese Schonfeld as a 24-hour cable news channel, and presently owned by ...

became the first non-Soviet broadcaster allowed to beam its TV news programs to Moscow. Officially, CNN was available only to foreign guests in the

Savoy Hotel

The Savoy Hotel is a luxury hotel located in the Strand in the City of Westminster in central London, England. Built by the impresario Richard D'Oyly Carte with profits from his Gilbert and Sullivan opera productions, it opened on 6 August ...

, but Muscovites quickly learned how to pick up signals on their home televisions. That had a major impact on how Soviets saw events in their country and made censorship almost impossible.

The month-long nomination period for candidates for the

Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union

The Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union (russian: Съезд народных депутатов СССР, ''Sʺezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR'') was the highest body of state authority of the Soviet Union from 1989 to 1991.

Backg ...

lasted until 24 January 1989. For the next month, selection among the 7,531 district nominees took place at meetings organized by constituency-level electoral commissions. On 7 March, a final list of 5,074 candidates was published; about 85% were Party members.

In the two weeks prior to the 1,500 district polls, elections to fill 750 reserved seats of public organizations, contested by 880 candidates, were held. Of these seats, 100 were allocated to the CPSU, 100 to the

All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions The All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions (ACCTU; russian: Всесоюзный центральный совет профессиональных союзов, VTsSPS) was the national trade union federation of the Soviet Union.

The federati ...

, 75 to the Communist Youth Union (

Komsomol), 75 to the Committee of Soviet Women, 75 to the War and Labour Veterans' Organization, and 325 to other organizations such as the

Academy of Sciences

An academy of sciences is a type of learned society or academy (as special scientific institution) dedicated to sciences that may or may not be state funded. Some state funded academies are tuned into national or royal (in case of the Unit ...

. The selection process was done in April.

In the 26 March general elections, voter participation was an impressive 89.8%, and 1,958 (including 1,225 district seats) of the 2,250 CPD seats were filled. In district races, run-off elections were held in 76 constituencies on 2 and 9 April and fresh elections were organized on 14 and 20 April to 23 May, in the 199 remaining constituencies where the required absolute majority was not attained.

While most CPSU-endorsed candidates were elected, more than 300 lost to independent candidates such as Yeltsin, the physicist

Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov ( rus, Андрей Дмитриевич Сахаров, p=ɐnˈdrʲej ˈdmʲitrʲɪjevʲɪtɕ ˈsaxərəf; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident, nobel laureate and activist for n ...

and the lawyer

Anatoly Sobchak

Anatoly Aleksandrovich Sobchak ( rus, Анатолий Александрович Собчак, p=ɐnɐˈtolʲɪj ɐlʲɪˈksandrəvʲɪtɕ sɐpˈtɕak; 10 August 1937 – 19 February 2000) was a Soviet and Russian politician, a co-author of the ...

.

In the first session of the new Congress of People's Deputies (from 25 May to 9 June), hardliners retained control but reformers used the legislature as a platform for debate and criticism, which was broadcast live and uncensored. This transfixed the population since nothing like such a freewheeling debate had ever been witnessed in the Soviet Union. On 29 May, Yeltsin managed to secure a seat on the Supreme Soviet, and in the summer he formed the first opposition, the

Inter-Regional Deputies Group, composed of

Russian nationalists

Russian nationalism is a form of nationalism that promotes Russian cultural identity and unity. Russian nationalism first rose to prominence in the early 19th century, and from its origin in the Russian Empire, to its repression during early B ...

and

liberals. Composing the final legislative group in the Soviet Union, those elected in 1989 played a vital part in reforms and the eventual breakup of the Soviet Union during the next two years.

On 30 May 1989, Gorbachev proposed that local elections across the Union, scheduled for November 1989, be postponed until early 1990 because there were still no laws governing the conduct of such elections. This was seen by some as a concession to local Party officials, who feared they would be swept from power in a wave of anti-establishment sentiment.

On 25 October 1989, the Supreme Soviet voted to eliminate special seats for the Communist Party and other official organizations in union-level and republic-level elections, responding to sharp popular criticism that such reserved slots were undemocratic. After vigorous debate, the 542-member Supreme Soviet passed the measure 254–85 (with 36 abstentions). The decision required a constitutional amendment, ratified by the full congress, which met 12–25 December. It also passed measures that would allow direct elections for presidents of each of the 15 constituent republics. Gorbachev strongly opposed such a move during debate but was defeated.

The vote expanded the power of republics in local elections, enabling them to decide for themselves how to organize voting. Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia had already proposed laws for direct presidential elections. Local elections in all the republics had already been scheduled to take place between December and March 1990.

The six

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist repub ...

countries of Eastern Europe, while nominally independent, were widely recognized as the

Soviet satellite states

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent in the world, but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbiting ...

. All had been occupied by the Soviet

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

in 1945, had Soviet-style socialist states imposed upon them, and had very restricted freedom of action in either domestic or international affairs. Any moves towards real independence were suppressed by military force – in the

Hungarian Revolution of 1956

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 10 November 1956; hu, 1956-os forradalom), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was a countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the Hunga ...

and the

Prague Spring in 1968. Gorbachev abandoned the oppressive and expensive

Brezhnev Doctrine

The Brezhnev Doctrine was a Soviet foreign policy that proclaimed any threat to socialist rule in any state of the Soviet Bloc in Central and Eastern Europe was a threat to them all, and therefore justified the intervention of fellow socialist st ...

, which mandated intervention in the Warsaw Pact states, in favor of non-intervention in the internal affairs of allies – jokingly termed the

Sinatra Doctrine

The Sinatra Doctrine was a Soviet foreign policy under Mikhail Gorbachev for allowing member states of the Warsaw Pact to determine their own internal affairs. The name jokingly alluded to the song My Way popularized by Frank Sinatra—the So ...

in a reference to the

Frank Sinatra song "

My Way

"My Way" is a song popularized in 1969 by Frank Sinatra set to the music of the French song "Comme d'habitude" composed by Jacques Revaux with lyrics by Gilles Thibaut and Claude François and first performed in 1967 by Claude François. Its E ...

".

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

was the first republic to democratize following the enactment of the

April Novelization

The April Novelization ( pl, Nowela kwietniowa) was a set of changes (constitutional amendments) to the 1952 Constitution of the People's Republic of Poland, agreed in April 1989, in the aftermath of the Polish Round Table Agreement.

Among key ...

, as agreed upon following the

Polish Round Table Agreement talks from February to April between the government and the

Solidarity trade union, and soon the Pact began to dissolve itself. The last of the countries to overthrow Communist leadership,

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

, only did so following the violent

Romanian Revolution

The Romanian Revolution ( ro, Revoluția Română), also known as the Christmas Revolution ( ro, Revoluția de Crăciun), was a period of violent civil unrest in Romania during December 1989 as a part of the Revolutions of 1989 that occurred ...

.

Baltic Chain of Freedom

The

Baltic Way or Baltic Chain (also Chain of Freedom et, Balti kett, lv, Baltijas ceļš, lt, Baltijos kelias, russian: link=no, 'Балтийский путь') was a peaceful political demonstration on 23 August 1989. An estimated 2 million people joined hands to form a

human chain extending across

Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

,

Latvia and

Lithuania, which had been forcibly reincorporated into the Soviet Union in 1944. The colossal demonstration marked the 50th anniversary of the

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

that divided Eastern Europe into

spheres of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal al ...

and led to the

occupation of the Baltic states in 1940.

Just months after the Baltic Way protests, in December 1989, the

Congress of People's Deputies accepted—and Gorbachev signed—the report by the

Yakovlev

The Joint-stock company, JSC A.S. Yakovlev Design Bureau (russian: ОАО Опытно-конструкторское бюро им. А.С. Яковлева) is a Russian aircraft designer and manufacturer (design office prefix Yak). Its head offi ...

Commission condemning the secret protocols of the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact which led to the annexations of the three Baltic republics.

In the March 1989 elections to the Congress of Peoples Deputies, 36 of the 42 deputies from Lithuania were candidates from the independent national movement

Sąjūdis

Sąjūdis (, "Movement"), initially known as the Reform Movement of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Persitvarkymo Sąjūdis), is the political organisation which led the struggle for Lithuanian independence in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It was es ...

. That was the greatest victory for any national organization within the Soviet Union and was a devastating revelation to the Lithuanian Communist Party of its growing unpopularity.

On 7 December 1989, the

Communist Party of Lithuania

The Communist Party of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos komunistų partija; russian: Коммунистическая партия Литвы) is a banned communist party in Lithuania. The party was established in early October 1918 and operated clan ...

under the leadership of

Algirdas Brazauskas, split from the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union and abandoned its claim to have a constitutional "leading role" in politics. A smaller loyalist faction of the Communist Party, headed by hardliner

Mykolas Burokevičius

Mykolas Burokevičius (7 October 1927 – 20 January 2016) was a communist political leader in Lithuania. After the Communist Party of Lithuania separated from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), he established alternative pro-CPSU Co ...

, was established and remained affiliated with the party. However, Lithuania's governing Communist Party was formally independent from Moscow's control, a first for a Soviet republics and a political earthquake that prompted Gorbachev to arrange a visit to Lithuania the following month in a futile attempt to bring the local party back under control. The following year, the Communist Party lost power altogether in multiparty parliamentary elections, which had caused

Vytautas Landsbergis

Vytautas Landsbergis (born 18 October 1932) is a Lithuanian politician and former Member of the European Parliament. He was the first Speaker of Reconstituent Seimas of Lithuania after its independence declaration from the Soviet Union. He has ...

to become the first noncommunist leader (Chairman of the Supreme Council of Lithuania) of Lithuania since its forced incorporation into the Soviet Union.

Caucasus

On 16 July 1989, the

Popular Front of Azerbaijan

The Azerbaijani Popular Front Party (APFP; az, Azərbaycan Xalq Cəbhəsi Partiyası, ) is a political party in Azerbaijan, founded in 1992 by Abulfaz Elchibey. After Elchibey's death in 2000, the party split into two wings, the ''reform'' win ...

held its first congress and elected

Abulfaz Elchibey, who would become president, as its chairman. On 19 August, 600,000 protesters jammed Baku's Lenin Square (now Azadliq Square) to demand the release of political prisoners. In the second half of 1989, weapons were handed out in Nagorno-Karabakh. When Karabakhis got hold of small arms to replace hunting rifles and crossbows, casualties began to mount; bridges were blown up, roads were blockaded, and hostages were taken.

In a new and effective tactic, the Popular Front launched a rail blockade of Armenia, which caused petrol and food shortages because 85 percent of Armenia's freight came from Azerbaijan.

[''Black Garden'' de Waal, Thomas. 2003. NYU. , p. 87] Under pressure from the Popular Front the Communist authorities in Azerbaijan started making concessions. On 25 September, they passed a sovereignty law that gave precedence to Azerbaijani law, and on 4 October, the Popular Front was permitted to register as a legal organization as long as it lifted the blockade. Transport communications between Azerbaijan and Armenia never fully recovered.

Tensions continued to escalate and on 29 December, Popular Front activists seized local party offices in

Jalilabad, wounding dozens.

On 31 May 1989, the 11 members of the Karabakh Committee, who had been imprisoned without trial in Moscow's

Matrosskaya Tishina prison, were released and returned home to a hero's welcome. Soon after his release,

Levon Ter-Petrossian

Levon Hakobi Ter-Petrosyan ( hy, Լևոն Հակոբի Տեր-Պետրոսյան; born 9 January 1945), also known by his initials LTP, is an Armenian politician who served as the first president of Armenia from 1991 until his resignation in 1998 ...

, an academic, was elected chairman of the anti-communist opposition

Pan-Armenian National Movement

The Pan-Armenian National Movement or Armenian All-national Movement ( hy, Հայոց Համազգային Շարժում, translit=Hayots Hamazgain Sharzhum; HHS) was a political party in Armenia.

History

The party emerged from the resolution of ...

, and later stated that it was in 1989 that he first began considering full independence as his goal.

On 7 April 1989, Soviet troops and armored personnel carriers were sent to

Tbilisi

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Kura River with a population of approximately 1.5 million p ...

after more than 100,000 people protested in front of Communist Party headquarters with banners calling for

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

to secede from the Soviet Union and for

Abkhazia to be fully integrated into Georgia. On

9 April 1989, troops attacked the demonstrators; some 20 people were killed and more than 200 wounded. This event radicalized Georgian politics, prompting many to conclude that independence was preferable to continued Soviet rule. Given the abuses by members of the armed forces and police, Moscow acted fast. On 14 April, Gorbachev removed

Jumber Patiashvili

Jumber Patiashvili ( ka, ჯუმბერ პატიაშვილი) (born January 5, 1940) is a Georgian politician. He was the Communist leader of the Georgian SSR from 1985 to 1989.

Born in Lagodekhi, Kakheti (eastern Georgia), he gra ...

as

First Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party The First Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party (; ) was the leading position in the Georgian Communist Party during the Soviet era. Its leaders were responsible for many of the affairs in Georgia and were considered the leader of the Georgian S ...

as a result of the killings and replaced him with former Georgian

KGB

The KGB (russian: links=no, lit=Committee for State Security, Комитет государственной безопасности (КГБ), a=ru-KGB.ogg, p=kəmʲɪˈtʲet ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əj bʲɪzɐˈpasnəsʲtʲɪ, Komitet gosud ...

chief

Givi Gumbaridze

Givi Gumbaridze ( ka, გივი გუმბარიძე; born 22 March 1945) is a former Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1 ...

.

On 16 July 1989, in

Abkhazia's capital

Sukhumi

Sukhumi (russian: Суху́м(и), ) or Sokhumi ( ka, სოხუმი, ), also known by its Abkhaz name Aqwa ( ab, Аҟәа, ''Aqwa''), is a city in a wide bay on the Black Sea's eastern coast. It is both the capital and largest city of ...

, a protest against the opening of a Georgian university branch in the town led to violence that quickly degenerated into a large-scale inter-ethnic confrontation in which 18 died and hundreds were injured before Soviet troops restored order. This riot marked the start of the

Georgian-Abkhaz conflict.

On 17 November 1989, the Supreme Council of Georgia held its fall plenary session, which lasted two days. One of the resolutions that came out of it was as a declaration against what it called an "illegal" accession into the Soviet Union of the country 68 years ago, forced against its will by the Red Army, the CPSU and the All-Russian Council of People's Commissars.

Western republics

In the 26 March 1989, elections to the Congress of People's Deputies, 15 of the 46 Moldovan deputies elected for congressional seats in Moscow were supporters of the Nationalist/Democratic movement. The

Popular Front of Moldova

The Popular Front of Moldova ( ro, Frontul Popular din Moldova) was a political movement in the Moldavian SSR, one of the 15 union republics of the former Soviet Union, and in the newly independent Republic of Moldova. Formally, the Front existe ...

founding congress took place two months later, on 20 May. During its second congress (30 June – 1 July 1989),

Ion Hadârcă was elected its president.

A series of demonstrations that became known as the

Grand National Assembly Great National Assembly or Grand National Assembly may refer to:

* Great National Assembly of Alba Iulia, an assembly of Romanian delegates that declared the unification of Transylvania and Romania

* Great National Assembly (Socialist Republic of R ...

( ro, Marea Adunare Naţională) was the Front's first major achievement. Such mass demonstrations, including one attended by 300,000 people on 27 August, convinced the Moldovan Supreme Soviet on 31 August to adopt the language law making

Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

*** Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

** Romanian cuisine, tradition ...

the official language, and replacing the

Cyrillic alphabet with

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

characters.

[King, p.140]

In Ukraine,

Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukrain ...

and

Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Kyi ...

celebrated Ukrainian Independence Day on 22 January 1989. Thousands gathered in Lviv for an unauthorized ''

moleben

A Paraklesis ( el, Παράκλησις, Slavonic: молебенъ) or Supplicatory Canon in the Byzantine Rite, is a service of supplication for the welfare of the living. It is addressed to a specific Saint or to the Most Holy Theotokos whose ...

'' (religious service) in front of

St. George's Cathedral. In Kyiv, 60 activists met in a Kyiv apartment to commemorate the proclamation of the

Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

in 1918. On 11–12 February 1989, the Ukrainian Language Society held its founding congress. On 15 February 1989, the formation of the Initiative Committee for the Renewal of the

Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

The Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC; uk, Українська автокефальна православна церква (УАПЦ), Ukrayinska avtokefalna pravoslavna tserkva (UAPC)) was one of the three major Eastern Orthod ...

was announced. The program and statutes of the movement were proposed by the

Writers' Union of Ukraine and were published in the journal ''Literaturna Ukraina'' on 16 February 1989. The organization heralded Ukrainian dissidents such as

Vyacheslav Chornovil

Viacheslav Maksymovych Chornovil ( uk, В'ячесла́в Макси́мович Чорнові́л; 24 December 1937 – 25 March 1999) was a Ukrainian politician and Soviet dissident. As a prominent Ukrainian dissident in the Soviet Union, ...

.

In late February, large public rallies took place in Kyiv to protest the election laws, on the eve of the 26 March elections to the USSR Congress of People's Deputies, and to call for the resignation of the first secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine,

Volodymyr Shcherbytsky

Volodymyr Vasylyovych Shcherbytsky, russian: Влади́мир Васи́льевич Щерби́цкий; ''Vladimir Vasilyevich Shcherbitsky'', (17 February 1918 — 16 February 1990) was a Ukrainian Soviet politician. He was First Secr ...

, lampooned as "the mastodon of stagnation". The demonstrations coincided with a visit to Ukraine by

Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev. On 26 February 1989, between 20,000 and 30,000 people participated in an unsanctioned ecumenical memorial service in Lviv, marking the anniversary of the death of 19th-century Ukrainian artist and nationalist