Brazilian Portuguese on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

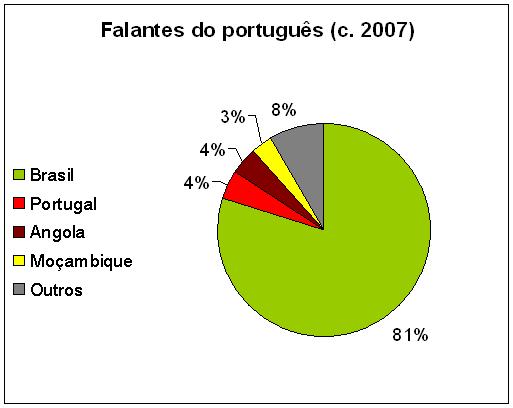

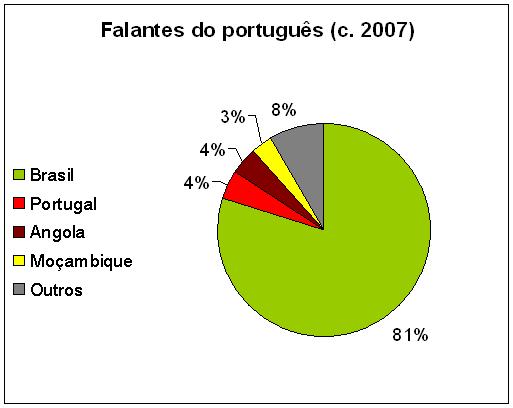

Brazilian Portuguese (' ), also Portuguese of Brazil (', ) or South American Portuguese (') is the set of

varieties

Variety may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Entertainment formats

* Variety (radio)

* Variety show, in theater and television

Films

* ''Variety'' (1925 film), a German silent film directed by Ewald Andre Dupont

* ''Variety'' (1935 film), ...

of the

Portuguese language

Portuguese ( or, in full, ) is a western Romance language of the Indo-European language family, originating in the Iberian Peninsula of Europe. It is an official language of Portugal, Brazil, Cape Verde, Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau and ...

native to

Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

and the most influential form of Portuguese worldwide. It is spoken by almost all of the 214 million inhabitants of Brazil and spoken widely across the

Brazilian diaspora

The Brazilian diaspora is the migration of Brazilians to other countries, a mostly recent phenomenon that has been driven mainly by economic recession and hyperinflation that afflicted Brazil in the 1980s and early 1990s, and since 2014, by the p ...

, today consisting of about two million Brazilians who have emigrated to other countries. With a population of over 214 million, Brazil is by far the world's largest Portuguese-speaking nation and the only one in the

Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

.

Brazilian Portuguese differs, particularly in phonology and

prosody, from varieties spoken in

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

and

Portuguese-speaking African countries. In these latter countries, the language tends to have a closer connection to contemporary European Portuguese, partly because Portuguese colonial rule ended much more recently there than in Brazil, partly due to the heavy indigenous and African influence on Brazilian Portuguese.

Despite this difference between the spoken varieties, Brazilian and European Portuguese differ little in formal writing and remain

mutually intelligible. However, due to the two reasons mentioned above, the gap between the written, formal language and the spoken language is much wider in Brazilian Portuguese than in European Portuguese.

In 1990, the

Community of Portuguese Language Countries

The Community of Portuguese Language Countries ( Portuguese: ''Comunidade dos Países de Língua Portuguesa''; abbreviated as the CPLP), also known as the Lusophone Commonwealth (''Comunidade Lusófona''), is an international organization and pol ...

(CPLP), which included representatives from all countries with Portuguese as the official language, reached an agreement on the reform of the Portuguese orthography to unify the two standards then in use by Brazil on one side and the remaining Portuguese-speaking countries on the other. This spelling reform went into effect in Brazil on 1 January 2009. In Portugal, the reform was signed into law by the President on 21 July 2008 allowing for a 6-year adaptation period, during which both orthographies co-existed. All of the CPLP countries have signed the reform. In Brazil, this reform has been in force since January 2016. Portugal and other Portuguese-speaking countries have since begun using the new orthography.

Regional varieties of Brazilian Portuguese, while remaining

mutually intelligible, may diverge from each other in matters such as vowel pronunciation and speech intonation.

History

Portuguese language in Brazil

The existence of Portuguese in Brazil is a legacy of the

Portuguese colonization of the Americas. The first wave of Portuguese-speaking immigrants settled in Brazil in the 16th century, but the language was not widely used then. For a time Portuguese coexisted with

Língua Geral, a

lingua franca based on

Amerindian languages

Over a thousand indigenous languages are spoken by the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. These languages cannot all be demonstrated to be related to each other and are classified into a hundred or so language families (including a large numbe ...

that was used by the

Jesuit missionaries, as well as with various

African languages

The languages of Africa are divided into several major language families:

* Niger–Congo or perhaps Atlantic–Congo languages (includes Bantu and non-Bantu, and possibly Mande and others) are spoken in West, Central, Southeast and Souther ...

spoken by the millions of

slaves brought into the country between the 16th and 19th centuries. By the end of the 18th century, Portuguese had affirmed itself as the national language. Some of the main contributions to that swift change were the expansion of

colonization to the Brazilian interior, and the growing numbers of Portuguese settlers, who brought their language and became the most important ethnic group in

Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

.

Beginning in the early 18th century,

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

's government made efforts to expand the use of Portuguese throughout the colony, particularly because its consolidation in Brazil would help guarantee to Portugal the lands in dispute with

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

(according to various treaties signed in the 18th century, those lands would be ceded to the people who effectively occupied them). Under the administration of the

Marquis of Pombal

Count of Oeiras () was a Portuguese title of nobility created by a royal decree, dated July 15, 1759, by King Joseph I of Portugal, and granted to Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, head of the Portuguese government.

Later, through another roy ...

(1750–1777), Brazilians started to favour the use of Portuguese, as the Marquis expelled the Jesuit missionaries (who had taught Língua Geral) and prohibited the use of

Nhengatu

The Nheengatu language (Tupi: , nheengatu rionegrino: ''yẽgatu'', nheengatu tradicional: ''nhẽẽgatú'' e nheengatu tapajoawara: ''nheẽgatu''), often written Nhengatu, is an indigenous language of the Tupi–Guarani languages, Tupi-Guaran ...

, or Lingua Franca.

The failed colonization attempts by the

French in

Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a ...

during the 16th century and the

Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

in the Northeast during the 17th century had negligible effects on Portuguese. The substantial waves of non-Portuguese-speaking immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (mostly from

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

,

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

,

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

,

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

,

Japan and

Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

) were linguistically integrated into the Portuguese-speaking majority within a few generations, except for some areas of the three southernmost states (

Paraná,

Santa Catarina, and

Rio Grande do Sul), in the case of Germans, Italians and Slavics, and in rural areas of the state of

São Paulo

São Paulo (, ; Portuguese for ' Saint Paul') is the most populous city in Brazil, and is the capital of the state of São Paulo, the most populous and wealthiest Brazilian state, located in the country's Southeast Region. Listed by the Ga ...

(Italians and Japanese).

Nowadays the overwhelming majority of Brazilians speak Portuguese as their mother tongue, with the exception of small, insular communities of descendants of European (German, Polish, Ukrainian, and Italian) and Japanese immigrants, mostly in the

South and Southeast as well as villages and reservations inhabited by

Amerindians

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the Am ...

. And even these populations make use of Portuguese to communicate with outsiders and to understand television and radio broadcasts, for example. Moreover, there is a community of

Brazilian Sign Language

Brazilian Sign Language ( pt, Língua Brasileira de Sinais ) is the sign language used by deaf communities of urban Brazil. It is also known in short as Libras () and variously abbreviated as LSB, LGB or LSCB (; "Brazilian Cities Sign Language" ...

users whose number is estimated by ''

Ethnologue'' to be as high as 3 million.

Loanwords

The development of Portuguese in Brazil (and consequently in the rest of the areas where Portuguese is spoken) has been influenced by other languages with which it has come into contact, mainly in the lexicon: first the

Amerindian languages

Over a thousand indigenous languages are spoken by the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. These languages cannot all be demonstrated to be related to each other and are classified into a hundred or so language families (including a large numbe ...

of the original inhabitants, then the various

African languages

The languages of Africa are divided into several major language families:

* Niger–Congo or perhaps Atlantic–Congo languages (includes Bantu and non-Bantu, and possibly Mande and others) are spoken in West, Central, Southeast and Souther ...

spoken by the slaves, and finally those of later European and Asian immigrants. Although the vocabulary is still predominantly Portuguese, the influence of other languages is evident in the Brazilian lexicon, which today includes, for example, hundreds of words of

Tupi–Guarani origin referring to local flora and fauna; numerous

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, M ...

n

Yoruba words related to foods, religious concepts, and musical expressions; and English terms from the fields of modern technology and commerce. Although some of these words are more predominant in Brazil, they are also used in Portugal and other countries where Portuguese is spoken.

Words derived from the

Tupi language are particularly prevalent in place names (''

Itaquaquecetuba

Itaquaquecetuba, also simply called Itaquá, is a municipality in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. It is part of the Metropolitan Region of São Paulo. The population is 375,011 (2020 est.) in an area of . It sits at an elevation of .

The municip ...

,'' ''

Pindamonhangaba

Pindamonhangaba is a municipality in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, located in the Paraíba Valley, between the two most active production and consumption regions in the country, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. It is accessible by the Via Dutra ( ...

,'' ''

Caruaru'', ''

Ipanema

Ipanema () is a neighbourhood located in the South Zone of the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, between Leblon and Arpoador. The beach at Ipanema became known internationally with the popularity of the bossa nova jazz song, "The Girl from Ipa ...

'', ''

Paraíba''). The native languages also contributed the names of most of the plants and animals found in Brazil (and most of these are the official names of the animals in other Portuguese-speaking countries as well), including ''arara'' ("

macaw"), ''jacaré'' ("South American

caiman

A caiman (also cayman as a variant spelling) is an alligatorid belonging to the subfamily Caimaninae, one of two primary lineages within the Alligatoridae family, the other being alligators. Caimans inhabit Mexico, Central and South America f ...

"), ''tucano'' ("

toucan

Toucans (, ) are members of the Neotropical near passerine bird family Ramphastidae. The Ramphastidae are most closely related to the American barbets. They are brightly marked and have large, often colorful bills. The family includes five g ...

"), ''mandioca'' ("

cassava

''Manihot esculenta'', commonly called cassava (), manioc, or yuca (among numerous regional names), is a woody shrub of the spurge family, Euphorbiaceae, native to South America. Although a perennial plant, cassava is extensively cultivated ...

"), ''abacaxi'' ("

pineapple

The pineapple (''Ananas comosus'') is a tropical plant with an edible fruit; it is the most economically significant plant in the family Bromeliaceae. The pineapple is indigenous to South America, where it has been cultivated for many centuri ...

"), and many more. However, many Tupi–Guarani

toponyms did not derive directly from Amerindian expressions, but were in fact coined by European settlers and

Jesuit missionaries

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

, who used the ''Língua Geral'' extensively in the first centuries of colonization. Many of the Amerindian words entered the Portuguese lexicon as early as in the 16th century, and some of them were eventually borrowed into other European languages.

African languages

The languages of Africa are divided into several major language families:

* Niger–Congo or perhaps Atlantic–Congo languages (includes Bantu and non-Bantu, and possibly Mande and others) are spoken in West, Central, Southeast and Souther ...

provided hundreds of words as well, especially in certain semantic domains, as in the following examples, which are also present in Portuguese:

* Food: ''quitute'', ''

quindim

Quindim ( — or ) is a popular Brazilian baked dessert with Portuguese heritage, made chiefly from sugar, egg yolks and ground coconut. It is a custard and usually presented as an upturned cup with a glistening surface and intensely yellow ...

'', ''

acarajé

Àkàrà (Yoruba)(English: Bean cake Hausa: kosai, Portuguese: Acarajé () is a type of fritter made from cowpeas or beans (black eye peas). It is found throughout West African, Caribbean, and Brazilian cuisines. The dish is traditionally encoun ...

'', ''

moqueca

Moqueca ( or depending on the dialect, also spelled muqueca) is a Brazilian seafood stew. Moqueca is typically made with shrimp or fish as a base with tomatoes, onions, garlic, lime and coriander. The name moqueca comes from the term ''mu'keka ...

'';

* Religious concepts: ''mandinga'', ''

macumba

''Makumba'' () is a term that has been used to describe various religions of the African diaspora found in Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay. It is sometimes considered by non-practitioners to be a form of witchcraft or black magic.

The ...

'', ''orixá'' ("

orisha"), ''axé'';

* Afro-Brazilian music: ''

samba'',

''lundu'',

''maxixe'', ''

berimbau

The berimbau () is a single-string percussion instrument, a musical bow, originally from Africa, that is now commonly used in Brazil.

The berimbau would eventually be incorporated into the practice of the Afro-Brazilian martial art ''capoeir ...

'';

* Body-related parts and conditions: ''banguela'' ("toothless"), ''bunda'' ("buttocks"), ''capenga'' ("lame"), ''caxumba'' ("mumps");

* Geographical features: ''cacimba'' ("well"), ''quilombo'' or ''mocambo'' ("runaway slave settlement"), ''senzala'' ("slave quarters");

* Articles of clothing: ''miçanga'' ("beads"), ''abadá'' ("

capoeira

Capoeira () is an Afro-Brazilian martial art that combines elements of dance, acrobatics, music and spirituality. Born of the melting pot of enslaved Africans, Indigenous Brazilians and Portuguese influences at the beginning of the 16th cent ...

or dance uniform"), ''tanga'' ("loincloth, thong");

* Miscellaneous household concepts: ''cafuné'' ("caress on the head"), ''curinga'' ("

joker card"), ''caçula'' ("youngest child," also ''cadete'' and ''filho mais novo''), and ''moleque'' ("brat, spoiled child," or simply "child," depending on the region).

Although the African slaves had various ethnic origins, by far most of the borrowings were contributed (1) by

Bantu languages (above all,

Kimbundu, from

Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

, and

Kikongo

Kongo or Kikongo is one of the Bantu languages spoken by the Kongo people living in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, Gabon and Angola. It is a tonal language. It was spoken by many of those who were taken from th ...

from Angola and the area that is now the

Republic of the Congo and the

Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

), and (2) by

Niger-Congo languages, notably

Yoruba/Nagô, from what is now

Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

, and Jeje/

Ewe, from what is now

Benin

Benin ( , ; french: Bénin , ff, Benen), officially the Republic of Benin (french: République du Bénin), and formerly Dahomey, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burkina Faso to the nort ...

.

There are also many loanwords from other European languages, including

English,

French,

German, and

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

. In addition, there is a limited set of vocabulary from

Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

.

Portuguese has borrowed a large number of words from English. In Brazil, these are especially related to the following fields (note that some of these words are used in other Portuguese-speaking countries):

* Technology and science:

''app'', ''mod'', ''layout'', ''briefing'', ''designer'', ''slideshow'', ''

mouse'', ''forward'', ''revolver'', ''relay'', ''home office'', ''home theater'', ''bonde'' ("streetcar, tram," from 1860s company bonds), ''chulipa'' (also ''dormente'', "sleeper"), ''bita'' ("beater," railway settlement tool), ''breque'' ("brake"), ''picape/pick-up'', ''hatch'', ''roadster'', ''SUV'', ''air-bag'', ''guincho'' ("winch"), ''tilburí'' (19th century), ''macadame'', ''workshop'';

* Commerce and finance: ''commodities'', ''debênture'', ''holding'', ''fundo hedge'', ''angel'', ''truste'', ''dumping'', ''CEO'', ''CFO'', ''MBA'', ''kingsize'', ''fast food'' (), ''delivery service'', ''self service'', ''drive-thru'', ''telemarketing'', ''franchise'' (also ''franquia''), ''

merchandising'', ''combo'', ''check-in'', ''pet shop'', ''sex shop'', ''flat'', ''loft'', ''motel'', ''suíte'', ''shopping center/mall'', ''food truck'', ''outlet'', ''tagline'', ''slogan'', ''jingle'', ''outdoor'', "outboard" (), ''case'' (advertising), ''showroom'';

* Sports:

''surf'', ''skating'', ''futebol'' (

"soccer", or the calque ''ludopédio''),

''voleibol'',

''wakeboard'',

''gol'' ("goal"), ''goleiro'', ''quíper'', ''chutar'', ''chuteira'', ''time'' ("team," ), ''turfe'', ''jockey club'', ''cockpit'', ''box'' (Formula 1), ''pódium'', ''pólo'', ''boxeador'', ''MMA'', ''UFC'', ''rugby'', ''match point'', ''nocaute'' ("knockout"), ''poker'', ''iate club'', ''handicap'';

* Miscellaneous cultural concepts: ''okay'', ''

gay

''Gay'' is a term that primarily refers to a homosexual person or the trait of being homosexual. The term originally meant 'carefree', 'cheerful', or 'bright and showy'.

While scant usage referring to male homosexuality dates to the late 1 ...

'', ''hobby'', ''vintage'', ''jam session'', ''junk food'', ''hot dog'', ''bife'' or ''bisteca'' ("steak"), ''rosbife'' ("roast beef"), ''sundae'', ''banana split'', ''milkshake'', (protein) ''shake'', ''araruta'' ("arrowroot"), ''panqueca'', ''cupcake'', ''brownie'', ''sanduíche'', ''X-burguer'', ''boicote'' ("boycott"), ''pet'', ''Yankee'', ''happy hour'', ''

lol'', ''nerd'' , ''geek'' (sometimes , but also ), ''noob'', ''punk'', ''skinhead'' (), ''

emo'' (),

''indie'' (), ''hooligan'', ''cool'', ''vibe'', ''hype'', ''rocker'', ''glam'', ''rave'', ''clubber'', ''cyber'', ''hippie'', ''yuppie'', ''hipster'', ''overdose'', ''junkie'', ''cowboy'',

''mullet'',

''country'', ''rockabilly'', ''pin-up'', ''socialite'', ''playboy'', ''

sex appeal

Sex is the trait that determines whether a sexually reproducing animal or plant produces male or female gametes. Male plants and animals produce smaller mobile gametes (spermatozoa, sperm, pollen), while females produce larger ones (ova, oft ...

'', ''

striptease'', ''after hours'', ''drag queen'', ''go-go boy'', ''

queer'' (as in "queer lit"), ''bear'' (also the calque ''urso''), ''twink'' (also ''efebo''/

ephebe), ''leather (dad)'', ''footing'' (19th century), ''piquenique'' (also ''convescote''), ''bro'', ''rapper'', ''mc'', ''beatbox'', ''break dance'', ''street dance'', ''free style'', ''hang loose'', ''soul'',

''gospel'', ''praise'' (commercial context, music industry), ''bullying'' , ''stalking'' , ''closet'', ''flashback'', ''check-up'', ''ranking'', ''bondage'', ''dark'', ''goth'' (''gótica''), ''vamp'', ''cueca boxer'' or ''cueca slip'' (male underwear), ''black tie'' (or ''traje de gala/cerimônia noturna''), ''smoking'' ("tuxedo"), ''quepe'', ''blazer'', ''jeans'', ''cardigã'', ''blush'', ''make-up artist'', ''hair stylist'', ''gloss labial'' (hybrid, also ''brilho labial''), ''pancake'' ("facial powder," also ''pó de arroz''), ''playground'', ''blecaute'' ("blackout"), ''script'', ''sex symbol'', ''bombshell'', ''blockbuster'', ''multiplex'', ''best-seller'', ''it-girl'', ''fail'' (web context),

''trolling'' (''trollar''), ''blogueiro'', ''photobombing'', ''selfie'', ''sitcom'', ''stand-up comedy'', ''non-sense'', ''non-stop'', ''

gamer'', ''

camper'', ''crooner'', ''backing vocal'', ''roadie'', ''playback'', ''overdrive'', ''food truck'', ''monster truck'', ''picape/pick-up'' (DJ), ''coquetel'' ("cocktail"), ''drinque'', ''pub'', ''bartender'', ''barman'', ''lanche'' ("portable lunch"), ''underground'' (cultural), ''flop'' (movie/TV context and slang), ''DJ'', ''VJ'', ''

haole

''Haole'' (; Hawaiian ) is a Hawaiian term for individuals who are not Native Hawaiian, and is applied to people primarily of European ancestry. Background

The origins of the word predate the 1778 arrival of Captain James Cook, as recorded in s ...

'' (slang, brought from Hawaii by surfers).

Many of these words are used throughout the

Lusosphere

Lusophones ( pt, Lusófonos) are ethnic group, peoples that speak Portuguese language, Portuguese as a native language, native or as common second language and nations where Portuguese features prominently in society. Comprising an estimated 270 m ...

.

French has contributed to Portuguese words for foods, furniture, and luxurious fabrics, as well as for various abstract concepts. Examples include ''hors-concours'', ''chic'', ''metrô'', ''batom'', ''soutien'', ''buquê'', ''abajur'', ''guichê'', ''içar'', ''chalé'', ''cavanhaque'' (from

Louis-Eugène Cavaignac

Louis-Eugène Cavaignac (; 15 October 1802 – 28 October 1857) was a French people, French general and politician who served as Cabinet of General Cavaignac, head of the executive power of France between June and December 1848, during the French ...

), ''calibre'', ''habitué'', ''clichê'', ''jargão'', ''manchete'', ''jaqueta'', ''boîte de nuit'' or ''boate'', ''cofre'', ''rouge'', ''frufru'', ''chuchu'', ''purê'', ''petit gâteau'', ''pot-pourri'', ''ménage'', ''enfant gâté'', ''enfant terrible'', ''garçonnière'', ''patati-patata'', ''parvenu'', ''détraqué'', ''enquête'', ''equipe'', ''malha'', ''fila'', ''burocracia'', ''birô'', ''affair'', ''grife'', ''gafe'', ''croquette'', ''crocante'', ''croquis'', ''femme fatale'', ''noir'', ''marchand'', ''paletó'', ''gabinete'', ''grã-fino'', ''blasé'', ''de bom tom'', ''bon-vivant'', ''guindaste'', ''guiar'', ''flanar'', ''bonbonnière'', ''calembour'', ''jeu de mots'', ''vis-à-vis'', ''tête-à-tête'', ''mecha'', ''blusa'', ''conhaque'', ''mélange'', ''bric-brac'', ''broche'', ''pâtisserie'', ''peignoir'', ''négliglé'', ''robe de chambre'', ''déshabillé'', ''lingerie'', ''corset'', ''corselet'', ''corpete'', ''pantufas'', ''salopette'', ''cachecol'', ''cachenez'', ''cachepot'', ''colete'', ''colher'', ''prato'', ''costume'', ''serviette'', ''garde-nappe'', ''avant-première'', ''avant-garde'', ''debut'', ''crepe'', ''frappé'' (including slang), ''canapé'', ''paetê'', ''tutu'', ''mignon'', ''pince-nez'', ''grand prix'', ''parlamento'', ''patim'', ''camuflagem'', ''blindar'' (from German), ''guilhotina'', ''à gogo'', ''pastel'', ''filé'', ''silhueta'', ''menu'', ''maître d'hôtel'', ''bistrô'', ''chef'', ''coq au vin'', ''rôtisserie'', ''maiô'', ''bustiê'', ''collant'', ''fuseau'', ''cigarette'', ''crochê'', ''tricô'', ''tricot'' ("pullover, sweater"), ''calção'', ''culotte'', ''botina'', ''bota'', ''galocha'', ''scarpin'' (ultimately Italian), ''sorvete'', ''glacê'', ''boutique'', ''vitrine'', ''manequim'' (ultimately Dutch), ''machê'', ''tailleur'', ''echarpe'', ''fraque'', ''laquê'', ''gravata'', ''chapéu'', ''boné'', ''edredom'', ''gabardine'', ''fondue'', ''buffet'', ''toalete'', ''pantalon'', ''calça Saint-Tropez'', ''manicure'', ''pedicure'', ''balayage'', ''limusine'', ''caminhão'', ''guidão'', ''cabriolê'', ''capilé'', ''garfo'', ''nicho'', ''garçonete'', ''chenille'', ''chiffon'', ''chemise'', ''chamois'', ''plissê'', ''balonê'', ''frisê'', ''chaminé'', ''guilhochê'', ''château'', ''bidê'', ''redingote'', ''chéri(e)'', ''flambado'', ''bufante'', ''pierrot'', ''torniquete'', ''molinete'', ''canivete'', ''guerra'' (Occitan), ''escamotear'', ''escroque'', ''flamboyant'', ''maquilagem'', ''visagismo'', ''topete'', ''coiffeur'', ''tênis'', ''cabine'', ''concièrge'', ''chauffeur'', ''hangar'', ''garagem'', ''haras'', ''calandragem'', ''cabaré'', ''coqueluche'', ''coquine'', ''coquette'' (''cocotinha''), ''galã'', ''bas-fond'' (used as slang), ''mascote'', ''estampa'', ''sabotagem'', ''RSVP'', ''rendez-vous'', ''chez...'', ''à la carte'', ''à la ...'', ''forró, forrobodó'' (from 19th-century ''faux-bourdon'').

Brazilian Portuguese tends to adopt French suffixes as in ''aterrissagem'' (Fr. ''atterrissage'' "landing

viation), differently from European Portuguese (cf. Eur.Port. ''aterragem''). Brazilian Portuguese (BP) also tends to adopt culture-bound concepts from French. That is the difference between BP ''estação'' ("station") and EP ''gare'' ("train station," Portugal also uses ''estação''). BP ''trem'' is from English ''train'' (ultimately from French), while EP ''comboio'' is from Fr. ''convoi''. An evident example of the dichotomy between English and French influences can be noted in the use of the expressions ''know-how'', used in a technical context, and ''savoir-faire'' in a social context. Portugal uses the expression ''hora de ponta'', from French ''l'heure de pointe'', to refer to the "rush hour," while Brazil has ''horário de pico, horário de pique'' and ''hora do rush''. Both ''bilhar'', from French ''billiard'', and the phonetic adaptation ''sinuca'' are used interchangeably for "snooker."

Contributions from

German and

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

include terms for foods, music, the arts, and architecture.

From German, besides

strudel

A strudel (, ) is a type of layered pastry with a filling that is usually sweet, but savoury fillings are also common. It became popular in the 18th century throughout the Habsburg Empire. Strudel is part of Austrian cuisine but is also comm ...

,

pretzel,

bratwurst

Bratwurst () is a type of German sausage made from pork or, less commonly, beef or veal. The name is derived from the Old High German ''Brätwurst'', from ''brät-'', finely chopped meat, and ''Wurst'', sausage, although in modern German it is o ...

,

kuchen (also ''bolo cuca''),

sauerkraut (also spelled ''chucrute'' from French ''choucroute'' and pronounced ),

wurstsalat

Wurstsalat (German, literally ''sausage salad'') is a tart sausage salad prepared with distilled white vinegar, oil and onions. A variation of the recipe adds strips of pickled gherkin. It is generally made from boiled sausage like Lyoner, st ...

,

sauerbraten,

Oktoberfest

The Oktoberfest (; bar, Wiesn, Oktobafest) is the world's largest Volksfest, featuring a beer festival and a travelling carnival. It is held annually in Munich, Bavaria, Germany. It is a 16- to 18-day folk festival running from mid- or ...

,

biergarten

A beer garden (German: ''Biergarten'') is an outdoor area in which beer and food are served, typically at shared tables shaded by trees.

Beer gardens originated in Bavaria, of which Munich is the capital city, in the 19th century, and remain co ...

, ''zelt'', Osterbaum,

Bauernfest,

Schützenfest, ''hinterland'', ''Kindergarten'', ''bock'', ''fassbier'' and ''chope'' (from ''Schoppen''), there are also abstract terms from German such as ''Prost'', ''zum wohl'', ''doppelgänger'' (also ''sósia''), ''über'', ''brinde'', ''kitsch'', ''ersatz'', ''blitz'' ("police action"), and possibly ''encrenca'' ("difficult situation," perhaps from Ger. ''ein Kranker'', "a sick person"). ''Xumbergar'', ''brega'' (from marshal

Friedrich Hermann Von Schönberg), and ''xote'' (musical style and dance) from ''schottisch''. A significant number of beer brands in Brazil are named after German culture-bound concepts and place names because the brewing process was brought by German immigrants.

Italian loan words and expressions, in addition to those that are related to food or music, include ''tchau'' (''"

ciao"''), ''nonna'', ''nonnino'', ''imbróglio'', ''bisonho'', ''entrevero'', ''

panetone'', ''colomba'', ''è vero'', ''cicerone'', ''male male'', ''capisce'', ''mezzo'', ''va bene'', ''ecco'', ''ecco fatto'', ''ecco qui'', ''caspita'', ''schifoso'', ''gelateria'', ''cavolo'', ''incavolarsi'', ''pivete'', ''engambelar'', ''andiamo via'', ''

tiramisu

Tiramisu ( it, tiramisù , from , "pick me up" or "cheer me up") is a coffee-flavoured Italian dessert. It is made of ladyfingers (savoiardi) dipped in coffee, layered with a whipped mixture of eggs, sugar, and mascarpone cheese, flavoured w ...

'', ''

tarantella

() is a group of various southern Italian folk dances originating in the regions of Calabria, Campania and Puglia. It is characterized by a fast upbeat tempo, usually in time (sometimes or ), accompanied by tambourines. It is among the mo ...

'', ''

grappa'', ''stratoria''. Terms of endearment of Italian origin include ''amore'', ''bambino/a'', ''ragazzo/a'', ''caro/a mio/a'', ''tesoro'', and ''bello/a''; also ''babo'', ''mamma'', ''baderna'' (from ''Marietta Baderna''), ''carcamano'', ''torcicolo'', ''casanova'', ''noccia'', ''noja'', ''che me ne frega'', ''io ti voglio tanto bene'', and ''ti voglio bene assai''.

Fewer words have been borrowed from

Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

. The latter borrowings are also mostly related to food and drink or culture-bound concepts, such as ''quimono'', from Japanese

kimono,

''karaokê'', ''yakisoba'', ''temakeria'', ''sushi bar'', ''mangá'', ''biombo'' (from Portugal) (from ''byó bu sukurín'', "folding screen"), ''jó ken pô'' or ''jankenpon'' ("

rock-paper-scissors

Rock paper scissors (also known by other orderings of the three items, with "rock" sometimes being called "stone," or as Rochambeau, roshambo, or ro-sham-bo) is a hand game originating in China, usually played between two people, in which each p ...

," played with the Japanese words being said before the start), ''saquê'', ''sashimi'', ''tempurá'' (a lexical "loan repayment" from a Portuguese loanword in Japanese), ''hashi'', ''wasabi'', ''johrei'' (religious philosophy),

''nikkei'', ''gaijin'' ("non-Japanese"), ''

issei

is a Japanese-language term used by ethnic Japanese in countries in North America and South America to specify the Japanese people who were the first generation to immigrate there. are born in Japan; their children born in the new country are ...

'' ("Japanese immigrant"), as well as the different descending generations ''

nisei

is a Japanese-language term used in countries in North America and South America to specify the ethnically Japanese children born in the new country to Japanese-born immigrants (who are called ). The are considered the second generation, ...

'', ''

sansei

is a Japanese and North American English term used in parts of the world such as South America and North America to specify the children of children born to ethnic Japanese in a new country of residence. The '' nisei'' are considered the second ...

'', ''

yonsei'', ''gossei'', ''rokussei'' and ''shichissei''. Other Japanese loanwords include racial terms, such as ''ainoko'' ("Eurasian") and ''

hafu'' (from English ''half''); work-related, socioeconomic, historical, and ethnic terms limited to some spheres of society, including ''koseki'' ("genealogical research"), ''dekassegui'' ("

dekasegi

Dekasegi ( pt, decassegui, decasségui, , ) is a term that is used in Brazil to refer to people, primarily Japanese Brazilians, who have migrated to Japan, having taken advantage of Japanese citizenship or '' nisei visa'' and immigration laws to w ...

"), ''arubaito'', ''kaizen'', ''seiketsu'', ''karoshi'' ("death by work excess"), ''

burakumin

is a name for a low-status social group in Japan. It is a term for ethnic Japanese people with occupations considered as being associated with , such as executioners, undertakers, slaughterhouse workers, butchers, or tanners.

During Japan's ...

'', ''kamikaze'', ''seppuku'', ''harakiri'', ''jisatsu'', ''jigai'', and ''ainu''; martial arts terms such as ''karatê'', ''aikidô'', ''bushidô'', ''katana'', ''judô'', ''jiu-jítsu'', ''kyudô'', ''

nunchaku

is a traditional Okinawan martial arts weapon consisting of two sticks (traditionally made of wood), connected to each other at their ends by a short metal chain or a rope. It is approximately 30 cm (sticks) and 1 inch (rope). A person w ...

'', and ''sumô''; terms related to writing, such as ''kanji'', ''kana'', ''katakana'', ''hiragana'', and ''romaji''; and terms for art concepts such as ''kabuki'' and ''ikebana''. Other culture-bound terms from Japanese include

''ofurô'' ("Japanese bathtub"), ''Nihong'' ("target news niche and websites"), ''

kabocha

Kabocha (; from Japanese カボチャ, 南瓜) is a type of winter squash, a Japanese variety of the species ''Cucurbita maxima.'' It is also called kabocha squash or Japanese pumpkin in North America. In Japan, "''kabocha''" may refer to eithe ...

'' (type of pumpkin introduced in Japan by the Portuguese), ''

reiki

is a Japanese form of energy healing, a type of alternative medicine. Reiki practitioners use a technique called ''palm healing'' or ''hands-on healing'' through which a " universal energy" is said to be transferred through the palms of the ...

'', and ''

shiatsu

''Shiatsu'' ( ; ) is a form of Japanese bodywork based on concepts in traditional Chinese medicine such as qi meridians. Having been popularized in the twentieth century by Tokujiro Namikoshi (1905–2000), ''shiatsu'' derives from the older ...

''. Some words have popular usage while others are known for a specific context in specific circles. Terms used among

Nikkei descendants include ''oba-chan'' ("grandma"); ''onee-san'', ''onee-chan'', ''onii-san'', and ''onii-chan''; toasts and salutations such as ''kampai'' and ''banzai''; and some

honorific

An honorific is a title that conveys esteem, courtesy, or respect for position or rank when used in addressing or referring to a person. Sometimes, the term "honorific" is used in a more specific sense to refer to an honorary academic title. It ...

suffixes of address such as ''chan'', ''kun'', ''sama'', ''san'', and ''senpai''.

Chinese contributed a few terms such as ''

tai chi chuan

Tai chi (), short for Tai chi ch'üan ( zh, s=太极拳, t=太極拳, first=t, p=Tàijíquán, labels=no), sometimes called " shadowboxing", is an internal Chinese martial art practiced for defense training, health benefits and meditation. T ...

'' and ''chá'' ("tea"), also in European Portuguese.

The loan vocabulary includes several

calques

In linguistics, a calque () or loan translation is a word or phrase borrowed from another language by literal word-for-word or root-for-root translation. When used as a verb, "to calque" means to borrow a word or phrase from another language whi ...

, such as ''arranha-céu'' ("skyscraper," from French ''gratte-ciel'') and ''cachorro-quente'' (from English ''hot dog'') in Portuguese worldwide.

Other influences

Use of the reflexive ''me'', especially in São Paulo and

the South, is thought to be an Italianism, attributed to the large Italian immigrant population, as are certain prosodic features, including patterns of intonation and stress, also in the South and

Southeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

.

Other scholars, however, notably Naro & Scherre,

have noted that the same or similar processes can be observed in the European variant, as well as in many varieties of Spanish, and that the main features of Brazilian Portuguese can be traced directly from 16th-century European Portuguese.

In fact, they find many of the same phenomena in other Romance languages, including

Aranese Occitan,

French,

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

and

Romanian; they explain these phenomena as due to natural Romance

drift.

Naro and Scherre affirm that Brazilian Portuguese is not a "decreolized" form, but rather the "

nativization

Nativization is the process through which in the virtual absence of native speakers, a language undergoes new phonological, morphological, syntactical, semantic and stylistic changes, and gains new native speakers. This happens necessarily when a ...

" of a "radical Romanic" form.

They assert that the phenomena found in Brazilian Portuguese are inherited from Classical Latin and Old Portuguese.

According to another linguist, vernacular Brazilian Portuguese is continuous with European Portuguese, while its phonetics are more conservative in several aspects, characterizing the nativization of a

koiné formed by several regional European Portuguese varieties brought to Brazil, modified by natural drift.

Written and spoken languages

The written language taught in Brazilian

school

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes comp ...

s has historically been based by law on the standard of

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

and until the 19th century, Portuguese writers often were regarded as models by some Brazilian authors and university professors. However, this aspiration to unity was severely weakened in the 20th century by

nationalist movements in literature and the arts, which awakened in many Brazilians a desire for a national style uninfluenced by the standards of Portugal. Later, agreements were reached to preserve at least an orthographic unity throughout the Portuguese-speaking world, including the African and Asian variants of the language (which are typically more similar to EP, due to a Portuguese presence lasting into the second half of the 20th century).

On the other hand, the spoken language was not subject to any of the constraints that applied to the written language, and consequently Brazilian Portuguese sounds different from any of the other varieties of the language. Brazilians, when concerned with pronunciation, look to what is considered the national standard variety, and never to the European one. This linguistic independence was fostered by the tension between Portugal and the settlers (immigrants) in Brazil from the time of the country's de facto settlement, as immigrants were forbidden to speak freely in their native languages in Brazil for fear of severe punishment by the Portuguese authorities. Lately, Brazilians in general have had some exposure to European speech, through TV and music. Often one will see Brazilian actors working in Portugal and Portuguese actors working in Brazil.

Modern Brazilian Portuguese has been highly influenced by other languages introduced by immigrants through the past century, specifically by German, Italian and Japanese immigrants. This high intake of immigrants not only caused the incorporation and/or adaptation of many words and expressions from their native language into local language, but also created specific dialects, such as the German ''Hunsrückisch'' dialect in the South of Brazil.

Formal writing

The written Brazilian standard differs from the European one to about the same extent that written

American English differs from written British English. The differences extend to spelling, lexicon, and grammar. However, with the entry into force of the Orthographic Agreement of 1990 in Portugal and in Brazil since 2009, these differences were drastically reduced.

Several Brazilian writers have been awarded with the highest prize of the Portuguese language. The

Camões Prize

The Camões Prize (Portuguese, ''Prémio Camões'', ), named after Luís de Camões, is the most important prize for literature in the Portuguese language. It is awarded annually by the Portuguese ''Direção-Geral do Livro, dos Arquivos e das Bi ...

awarded annually by Portuguese and Brazilians is often regarded as the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in Literature for works in Portuguese.

Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis,

João Guimarães Rosa

João Guimarães Rosa (; 27 June 1908 – 19 November 1967) was a Brazilian novelist, short story writer and diplomat.

Rosa only wrote one novel, '' Grande Sertão: Veredas'' (known in English as ''The Devil to Pay in the Backlands''), a revoluti ...

,

Carlos Drummond de Andrade,

Graciliano Ramos

Graciliano Ramos de Oliveira () (October 27, 1892 – March 20, 1953) was a Brazilian modernist writer, politician and journalist. He is known worldwide for his portrayal of the precarious situation of the poor inhabitants of the Brazilian ''sert� ...

,

João Cabral de Melo Neto,

Cecília Meireles,

Clarice Lispector,

José de Alencar,

Rachel de Queiroz,

Jorge Amado,

Castro Alves,

Antonio Candido

Antonio Candido de Mello e Souza (July 24, 1918 – May 12, 2017) was a Brazilian writer, professor, sociologist, and literary critic. As a critic of Brazilian literature, he is regarded as having been one of the foremost scholars on the subject ...

,

Autran Dourado,

Rubem Fonseca,

Lygia Fagundes Telles and

Euclides da Cunha

Euclides da Cunha (, January 20, 1866 – August 15, 1909) was a Brazilian journalist, sociologist and engineer. His most important work is '' Os Sertões'' (''Rebellion in the Backlands''), a non-fictional account of the military expeditions ...

are Brazilian writers recognized for writing the most outstanding work in the Portuguese language.

Spelling differences

The Brazilian spellings of certain words differ from those used in Portugal and the other Portuguese-speaking countries. Some of these differences are merely orthographic, but others reflect true differences in pronunciation.

Until the implementation of the 1990 orthographic reform, a major subset of the differences related to the consonant clusters ''cc'', ''cç'', ''ct'', ''pc'', ''pç'', and ''pt''. In many cases, the letters ''c'' or ''p'' in syllable-final position have become silent in all varieties of Portuguese, a common phonetic change in Romance languages (cf. Spanish ''objeto'', French ''objet''). Accordingly, they stopped being written in BP (compare

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

spelling standards), but continued to be written in other Portuguese-speaking countries. For example, the word ''acção'' ("action") in European Portuguese became ''ação'' in Brazil, European ''óptimo'' ("optimum") became ''ótimo'' in Brazil, and so on, where the consonant was silent both in BP and EP, but the words were spelled differently. Only in a small number of words is the consonant silent in Brazil and pronounced elsewhere or vice versa, as in the case of BP ''fato'', but EP ''facto''. However, the new Portuguese language orthographic reform led to the elimination of the writing of the silent consonants also in the EP, making now the writing system virtually identical in all of the Portuguese-speaking countries.

However, BP has retained those

silent consonants in a few cases, such as ''detectar'' ("to detect"). In particular, BP generally distinguishes in sound and writing between ''secção'' ("section" as in ''anatomy'' or ''drafting'') and ''seção'' ("section" of an organization); whereas EP uses ''secção'' for both senses.

Another major set of differences is the BP usage of ''ô'' or ''ê'' in many words where EP has ''ó'' or ''é'', such as BP ''neurônio'' / EP ''neurónio'' ("neuron") and BP ''arsênico'' / EP ''arsénico'' ("arsenic"). These spelling differences are due to genuinely different pronunciations. In EP, the vowels ''e'' and ''o'' may be open (''é'' or ''ó'') or closed (''ê'' or ''ô'') when they are stressed before one of the nasal consonants ''m'', ''n'' followed by a vowel, but in BP they are always closed in this environment. The variant spellings are necessary in those cases because the general Portuguese spelling rules mandate a stress diacritic in those words, and the Portuguese

diacritics also encode vowel quality.

Another source of variation is the spelling of the sound before ''e'' and ''i''. By Portuguese spelling rules, that sound can be written either as ''j'' (favored in BP for certain words) or ''g'' (favored in EP). Thus, for example, we have BP ''berinjela ''/ EP ''beringela'' ("eggplant").

Language register – formal vs. informal

The linguistic situation of the BP informal speech in relation to the standard language is controversial. There are authors (Bortoni, Kato, Mattos e Silva, Bagno, Perini) who describe it as a case of

diglossia

In linguistics, diglossia () is a situation in which two dialects or languages are used (in fairly strict compartmentalization) by a single language community. In addition to the community's everyday or vernacular language variety (labeled ...

, considering that informal BP has developed, both in

phonetics

Phonetics is a branch of linguistics that studies how humans produce and perceive sounds, or in the case of sign languages, the equivalent aspects of sign. Linguists who specialize in studying the physical properties of speech are phoneticians. ...

and

grammar

In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structural constraints on speakers' or writers' composition of clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraints, a field that includes domain ...

, in its own particular way.

Accordingly, the formal register of Brazilian Portuguese has a written and spoken form. The written formal register (FW) is used in almost all printed media and written communication, is uniform throughout the country and is the "Portuguese" officially taught at school. The spoken formal register (FS) is essentially a phonetic rendering of the written form. (FS) is used in very formal situations, such as speeches or ceremonies or when reading directly out of a text. While (FS) is necessarily uniform in lexicon and grammar, it shows noticeable regional variations in pronunciation.

Characteristics of informal Brazilian Portuguese

The main and most general (i.e. not considering various regional variations) characteristics of the informal variant of BP are the following. While these characteristics are typical of Brazilian speech, some may also be present to varying degrees in other Lusophone areas, particular in Angola, Mozambique and Cabo Verde, which frequently incorporate certain features common to both the South American and European varieties. Although these characteristics would be readily understood in Portugal due to exposure to Brazilian media, other forms are preferred there (except the points concerning "estar" and "dar").

* dropping the first syllable of the verb ''estar'' ("

tatal/incidentalto be") throughout the conjugation (''ele tá'' ("he's") instead of ''ele está'' ("he is"), ''nós táva(mos/mo)'' ("we were") instead of ''nós estávamos'' ("we were"));

* dropping prepositions before subordinate and relative clauses beginning with conjunctions (''Ele precisa que vocês ajudem'' instead of ''Ele precisa de que vocês ajudem'');

* replacing ''haver'' when it means "to exist" with ''ter'' ("to have"): ''Tem muito problema na cidade'' ("There are many problems in the city") is much more frequent in speech than ''Há muitos problemas na cidade.''

* lack of third-person object pronouns, which may be replaced by their respective subject pronouns or omitted completely (''eu vi ele'' or even just ''eu vi'' instead of ''eu o vi'' for "I saw him/it")

* lack of second-person verb forms (except for some parts of Brazil) and, in various regions, plural third-person forms as well. For example ''tu cantas'' becomes ''tu canta'' or ''você canta'' (Brazilian uses the pronoun "você" a lot but "tu" is more localized. Some states never use it but in some locales such as Rio Grande do Sul, "você" is almost never used in informal speech, with "tu" being used instead, using both second and third-person forms depending on the speaker)

* lack of the relative pronoun ''cujo/cuja'' ("whose"), which is replaced by ''que'' ("that/which"), either alone (the possession being implied) or along with a possessive pronoun or expression, such as ''dele/dela'' (''A mulher cujo filho morreu'' ("the woman whose son died") becomes ''A mulher que o filho

elamorreu'' ("the woman that

erson died"))

* frequent use of the pronoun ''a gente'' ("people") with 3rd p. sg verb forms instead of the 1st p. pl verb forms and pronoun ''nós'' ("we/us"), though both are formally correct and ''nós'' is still much used.

* obligatory

proclisis in all cases (always ''me disseram'', rarely ''disseram-me''), as well as use of the pronoun between two verbs in a verbal expression (always ''vem me treinando'', never ''me vem treinando'' or ''vem treinando-me'')

* contracting certain high-frequency phrases, which is not necessarily unacceptable in standard BP (''para'' > ''pra''; ''dependo de ele ajudar'' > ''dependo 'dele' ajudar''; ''com as'' > ''cas''; ''deixa eu ver'' > ''xo vê/xeu vê''; ''você está'' > ''cê tá'' etc.)

* preference for ''para'' over ''a'' in the directional meaning (''Para onde você vai?'' instead of ''Aonde você vai?'' ("Where are you going?"))

* use of certain idiomatic expressions, such as ''Cadê o carro?'' instead of ''Onde está o carro?'' ("Where is the car?")

* lack of indirect object pronouns, especially ''lhe'', which are replaced by ''para'' plus their respective personal pronoun (''Dê um copo de água para ele'' instead of ''Dê-lhe um copo de água'' ("Give him a glass of water"); ''Quero mandar uma carta para você'' instead of ''Quero lhe mandar uma carta'' ("I want to send you a letter"))

* use of ''aí'' as a pronoun for indefinite direct objects (similar to

French 'en'). Examples: ''fala aí'' ("say it"), ''esconde aí'' ("hide it"), ''pera aí'' (''espera aí'' = "wait a moment");

*

impersonal use of the verb ''dar'' ("to give") to express that something is feasible or permissible. Example: ''dá pra eu comer?'' ("can/may I eat it?"); ''deu pra eu entender'' ("I could understand"); ''dá pra ver um homem na foto'' instead of ''pode ver-se um homem na foto'' ("it's possible to see a man in the picture")

*though often regarded as "uneducated" by language purists, some regions and social groups tend to avoid "redundant" plural agreement in article-noun-verb sequences in the spoken language, since the plural article alone is sufficient to express plurality. Examples: ''os menino vai pra escola'' ("the

luralboy goes to school") rather than ''os meninos vão para a escola'' ("the boys go to school"). Gender agreement, however, is always made even when plural agreement is omitted: ''os menino esperto'' (the smart boys) vs. ''as menina esperta'' (the smart girls).

* Use of a contraction of the imperative form of the verb "to look" ("olhar" = olha = ó) suffixed to adverbs of the place "aqui" and "ali" ("here" and "there") when directing someone's attention to something: "Olha, o carro dele 'ta ali-ó" (Look, his car's there/that's where his car is). When this is spoken reproduced in subtitles for audiovisual media, it is usually written in the non-contracted form ("aqui olha"), modern pronunciation notwithstanding.

Grammar

Syntactic and morphological features

Topic-prominent language

Modern

linguistic

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

studies have shown that Brazilian Portuguese is a

topic-prominent or topic- and subject-prominent language. Sentences with topic are extensively used in Portuguese, perhaps more in Brazilian Portuguese most often by means of turning an element (object or verb) in the sentence into an introductory phrase, on which the body of the sentence constitutes a comment (topicalization), thus emphasizing it, as in ''Esses assuntos eu não conheço bem,'' literally, "These subjects I don't know

hem

A hem in sewing is a garment finishing method, where the edge of a piece of cloth is folded and sewn to prevent unravelling of the fabric and to adjust the length of the piece in garments, such as at the end of the sleeve or the bottom of the g ...

well" (although this sentence would be perfectly acceptable in Portugal as well). In fact, in the Portuguese language, the anticipation of the verb or object at the beginning of the sentence, repeating it or using the respective pronoun referring to it, is also quite common, e.g. in ''Essa menina, eu não sei o que fazer com ela'' ("This girl, I don't know what to do with her") or ''Com essa menina eu não sei o que fazer'' ("With this girl I don't know what to do"). The use of redundant pronouns for means of topicalization is considered grammatically incorrect, because the topicalized noun phrase, according to traditional European analysis, has no syntactic function. This kind of construction, however, is often used in European Portuguese. Brazilian grammars traditionally treat this structure similarly, rarely mentioning such a thing as ''topic''. Nevertheless, the so-called

anacoluthon has taken on a new dimension in Brazilian Portuguese. The poet

Carlos Drummond de Andrade once wrote a short ''metapoema'' (a ''metapoem'', i. e., a poem about poetry, a specialty for which he was renowned) treating the concept of ''anacoluto'':

In colloquial language, this kind of ''anacoluto'' may even be used when the subject itself is the topic, only to add more emphasis to this fact, e.g. the sentence ''Essa menina, ela costuma tomar conta de cachorros abandonados'' ("This girl, she usually takes care of abandoned dogs"). This structure highlights the topic, and could be more accurately translated as "As for this girl, she usually takes care of abandoned dogs."

The use of this construction is particularly common with

compound subject A compound subject consists of two or more individual noun phrases coordinated to form a single, longer noun phrase. Compound subjects cause many difficulties in compliance with grammatical agreement between the subject and other entities (verbs, p ...

s, as in, e.g., ''Eu e ela, nós fomos passear'' ("She and I, we went for a walk"). This happens because the traditional syntax (''Eu e ela fomos passear'') places a plural-conjugated verb immediately following an argument in the singular, which may sound unnatural to Brazilian ears. The redundant pronoun thus clarifies the verbal inflection in such cases.

Progressive

Portuguese makes extensive use of verbs in the progressive aspect, almost as in English.

Brazilian Portuguese seldom has the present continuous construct ''estar a'' + infinitive, which, in contrast, has become quite common in European over the last few centuries. BP maintains the Classical Portuguese form of continuous expression, which is made by ''estar'' +

gerund

In linguistics, a gerund ( abbreviated ) is any of various nonfinite verb forms in various languages; most often, but not exclusively, one that functions as a noun. In English, it has the properties of both verb and noun, such as being modifiab ...

.

Thus, Brazilians will always write ''ela está dançando'' ("she is dancing"), not ''ela está a dançar''. The same restriction applies to several other uses of the gerund: BP uses ''ficamos conversando'' ("we kept on talking") and ''ele trabalha cantando'' ("he sings while he works"), but rarely ''ficamos a conversar'' and ''ele trabalha a cantar'' as is the case in most varieties of EP.

BP retains the combination ''a'' + infinitive for uses that are not related to continued action, such as ''voltamos a correr'' ("we went back to running"). Some varieties of EP

amely_from_Alentejo,_Algarve,_Açores_(Azores),_and_Madeira.html" ;"title="Alentejo.html" ;"title="amely from

amely_from_Alentejo,_Algarve,_Açores_(Azores),_and_Madeira">Alentejo.html"_;"title="amely_from_Alentejo">amely_from_Alentejo,_Algarve,_Açores_(Azores),_and_Madeiraalso_tend_to_feature_''estar''_+_

gerund_

In_linguistics,_a_gerund_(_abbreviated_)_is_any_of_various__nonfinite_verb_forms_in_various_languages;_most_often,_but_not_exclusively,_one_that_functions_as_a_noun._In__English,_it_has_the_properties_of_both_verb_and_noun,_such_as_being_modifiab_...

,_as_in_Brazil.

_Personal_pronouns

_=Syntax

=

In_general,_the_dialects_that_gave_birth_to_Portuguese_had_a_quite_flexible_use_of_the_object_pronouns_in_the_proclitic_or_enclitic_positions._In_Classical_Portuguese,_the_use_of_proclisis_was_very_extensive,_while,_on_the_contrary,_in_modern_European_Portuguese_the_use_of_enclisis_has_become_indisputably_majoritary.

Brazilians_normally_place_the_pronoun.html" ;"title="Alentejo">amely from Alentejo, Algarve, Açores (Azores), and Madeira">Alentejo.html" ;"title="amely from Alentejo">amely from Alentejo, Algarve, Açores (Azores), and Madeiraalso tend to feature ''estar'' +

gerund

In linguistics, a gerund ( abbreviated ) is any of various nonfinite verb forms in various languages; most often, but not exclusively, one that functions as a noun. In English, it has the properties of both verb and noun, such as being modifiab ...

, as in Brazil.

Personal pronouns

=Syntax

=

In general, the dialects that gave birth to Portuguese had a quite flexible use of the object pronouns in the proclitic or enclitic positions. In Classical Portuguese, the use of proclisis was very extensive, while, on the contrary, in modern European Portuguese the use of enclisis has become indisputably majoritary.

Brazilians normally place the pronoun">object pronoun before the verb (proclitic position), as in ''ele me viu'' ("he saw me"). In many such cases, the proclisis would be considered awkward or even grammatically incorrect in EP, in which the pronoun is generally placed after the verb (

enclitic position), namely ''ele viu-me''. However, formal BP still follows EP in avoiding starting a sentence with a proclitic pronoun; so both will write ''Deram-lhe o livro'' ("They gave him/her the book") instead of ''Lhe deram o livro'', though it will seldom be spoken in BP (but would be clearly understood).

However, in verb expressions accompanied by an object pronoun, Brazilians normally place it amid the auxiliary verb and the main one (''ela vem me pagando'' but not ''ela me vem pagando'' or ''ela vem pagando-me''). In some cases, in order to adapt this use to the standard grammar, some Brazilian scholars recommend that ''ela vem me pagando'' should be written like ''ela vem-me pagando'' (as in EP), in which case the enclisis could be totally acceptable if there would not be a factor of proclisis. Therefore, this phenomenon may or not be considered improper according to the prescribed grammar, since, according to the case, there could be a factor of proclisis that would not permit the placement of the pronoun between the verbs (e.g. when there is a negative adverb near the pronoun, in which case the standard grammar prescribes proclisis, ''ela não me vem pagando'' and not ''ela não vem-me pagando''). Nevertheless, nowadays, it is becoming perfectly acceptable to use a clitic between two verbs, without linking it with a hyphen (as in ''poderia se dizer'', or ''não vamos lhes dizer'') and this usage (known as: ''pronome solto entre dois verbos'') can be found in modern(ist) literature, textbooks, magazines and newspapers like

Folha de S.Paulo

''Folha de S.Paulo'' (sometimes spelled ''Folha de São Paulo''), also known as simply ''Folha'' (, ''Sheet''), is a Brazilian daily newspaper founded in 1921 under the name ''Folha da Noite'' and published in São Paulo by the Folha da Manhã c ...

and

O Estadão (see in-house style manuals of these newspapers, available on-line, for more details).

=Contracted forms

=

BP rarely uses the contracted combinations of direct and indirect object pronouns which are sometimes used in EP, such as ''me'' + ''o'' = ''mo'', ''lhe'' + ''as'' = ''lhas''. Instead, the indirect clitic is replaced by preposition + strong pronoun: thus BP writes ''ela o deu para mim'' ("she gave it to me") instead of EP ''ela deu-mo''; the latter most probably will not be understood by Brazilians, being obsolete in BP.

=Mesoclisis

=

The

mesoclitic placement of pronouns (between the verb stem and its inflection suffix) is viewed as archaic in BP, and therefore is restricted to very formal situations or stylistic texts. Hence the phrase ''Eu dar-lhe-ia'', still current in EP, would be normally written ''Eu lhe daria'' in BP. Incidentally, a marked fondness for enclitic and mesoclitic pronouns was one of the many memorable eccentricities of former Brazilian President

Jânio Quadros

Jânio da Silva Quadros (; January 25, 1917 – February 16, 1992) was a Brazilian lawyer and Politics of Brazil, politician who served as the 22nd president of Brazil from January 31 to August 25, 1961, when he resigned from office. He als ...

, as in his famous quote ''Bebo-o porque é líquido, se fosse sólido comê-lo-ia'' ("I drink it

iquorbecause it is liquid, if it were solid I would eat it")

Preferences

There are many differences between formal written BP and EP that are simply a matter of different preferences between two alternative words or constructions that are both officially valid and acceptable.

Simple versus compound tenses

A few synthetic tenses are usually replaced by compound tenses, such as in:

:future indicative: ''eu cantarei'' (simple), ''eu vou cantar'' (compound, ''ir'' + infinitive)

:conditional: ''eu cantaria'' (simple), ''eu iria/ia cantar'' (compound, ''ir'' + infinitive)

:past perfect: ''eu cantara'' (simple), ''eu tinha cantado'' (compound, ''ter'' + past participle)

Also, spoken BP usually uses the verb ''ter'' ("own", "have", sense of possession) and rarely ''haver'' ("have", sense of existence, or "there to be"), especially as an auxiliary (as it can be seen above) and as a verb of existence.

:written: ''ele havia/tinha cantado'' (he had sung)

:spoken: ''ele tinha cantado''

:written: ''ele podia haver/ter dito'' (he might have said)

:spoken: ''ele podia ter dito''

This phenomenon is also observed in Portugal.

Differences in formal spoken language

Phonology

In many ways, Brazilian Portuguese (BP) is

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

in its phonology. That also is true of

Angolan and

São Tomean Portuguese, as well as other

African dialects. Brazilian Portuguese has eight oral vowels, five nasal vowels, and several

diphthongs

A diphthong ( ; , ), also known as a gliding vowel, is a combination of two adjacent vowel sounds within the same syllable. Technically, a diphthong is a vowel with two different targets: that is, the tongue (and/or other parts of the speech ...

and

triphthongs, some oral and some nasal.

Vowels

* In vernacular varieties, the diphthong is typically monophthongized to , e.g. ''sou'' > .

* In vernacular varieties, the diphthong is usually monophthongized to , depending on the speaker, e.g. ''ferreiro'' > .

The reduction of

vowel

A vowel is a syllabic speech sound pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract. Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness and also in quantity (leng ...

s is one of the main phonetic characteristics of Portuguese generally, but in Brazilian Portuguese the intensity and frequency of that phenomenon varies significantly.

Vowels in Brazilian Portuguese generally are pronounced more openly than in European Portuguese, even when reduced. In syllables that follow the stressed syllable, ⟨o⟩ is generally pronounced as , ⟨a⟩ as , and ⟨e⟩ as . Some varieties of BP follow this pattern for vowels ''before'' the stressed syllable as well.

In contrast, speakers of European Portuguese pronounce unstressed ⟨a⟩ primarily as , and they elision, elide some unstressed vowels or reduce them to a short, near-close near-back unrounded vowel , a sound that does not exist in BP. Thus, for example, the word ''setembro'' is in BP, but in European Portuguese.

The main difference among the dialects of Brazilian Portuguese is the frequent presence or absence of open vowels in unstressed syllables. In dialects of the South Region, Brazil, South and

Southeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

, unstressed ⟨e⟩ and ⟨o⟩ (when they are not reduced to and ) are pronounced as the close-mid vowels and . Thus, ''operação'' (operation) and ''rebolar'' (to shake one's body) may be pronounced and . Open-mid vowels can occur only in the stressed syllable. An exception is in the formation of diminutives or augmentatives. For example, ''cafézinho'' (demitasse coffee) and ''bolinha'' (little ball) are pronounced with open-mid vowels although these vowels are not in stressed position.

Meanwhile, in accents of the Northeast Region, Brazil, Northeast and North Region, Brazil, North, in patterns that have not yet been much studied, the open-mid vowels and can occur in unstressed syllables in a large number of words. Thus, the above examples would be pronounced and .

Another difference between Northern/Northeastern dialects and Southern/Southeastern ones is the pattern of nasalization of vowels before ⟨m⟩ and ⟨n⟩. In all dialects and all syllables, orthographic ⟨m⟩ or ⟨n⟩ followed by another consonant represents nasalization of the preceding vowel. But when the ⟨m⟩ or ⟨n⟩ is syllable-initial (i.e. followed by a vowel), it represents nasalization only of a preceding ''stressed'' vowel in the South and Southeast, as compared to nasalization of ''any'' vowel, regardless of stress, in the Northeast and North. A famous example of this distinction is the word ''banana'', which a Northeasterner would pronounce , while a Southerner would pronounce .

Vowel nasalization in some dialects of Brazilian Portuguese is very different from that of French, for example. In French, the nasalization extends uniformly through the entire vowel, whereas in the Southern-Southeastern dialects of Brazilian Portuguese, the nasalization begins almost imperceptibly and then becomes stronger toward the end of the vowel. In this respect it is more similar to the nasalization of Hindi-Urdu phonology, Hindi-Urdu (see Anusvara). In some cases, the nasal archiphoneme even entails the insertion of a nasal consonant such as (compare ), as in the following examples:

* ''banco''

* ''tempo''

* ''pinta''

* ''sombra''

* ''mundo''

* ''fã''

* ''bem''

* ''vim''

* ''bom''

* ''um''

* ''mãe''

* ''pão''

* ''põe''

* ''muito''

Consonants

= Palatalization of /di/ and /ti/

=

One of the most noticeable tendencies of modern BP is the palatalization (sound change), palatalization of and by most regions, which are pronounced and (or and ), respectively, before . The word ''presidente'' "president," for example, is pronounced in these regions of Brazil but in Portugal.

The pronunciation probably began in

Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a ...

and is often still associated with this city but is now standard in many other states and major cities, such as Belo Horizonte and Salvador, Bahia, Salvador, and it has spread more recently to some regions of São Paulo (because of migrants from other regions), where it is common in most speakers under 40 or so.

It has always been standard in Brazil's Japanese people, Japanese community since it is also a feature of

Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

. The regions that still preserve the unpalatalized and are mostly in the Northeast and South of

Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

by the stronger influence from European Portuguese (Northeast), and from Italian and Argentine Spanish (South).

= Palatalization of /li/ and /ni/

=

Another common change that differentiates Brazilian Portuguese from other dialects is the palatalization (phonetics), palatalization of and followed by the vowel , yielding and . ''menina'', "girl" ; ''Babilônia'', "Babylon" ; ''limão'', "lemon" ; ''sandália'', "sandal" .

= Epenthetic glide before final /s/

=

A change that is in the process of spreading in BP and perhaps started in the Northeast is the insertion of after stressed vowels before at the end of a syllable. It began in the context of (''mas'' "but" is now pronounced in most of Brazil, making it homophonous with ''mais'' "more").

Also, the change is spreading to other final vowels, and at least in the Northeast and the Southeast, the normal pronunciation of ''voz'' "voice" is . Similarly, ''três'' "three" becomes , making it rhyme with ''seis'' "six" ; this may explain the common Brazilian replacement of ''seis'' with ''meia'' ("half", as in "half a dozen") when pronouncing phone numbers.

=Epenthesis in consonant clusters

=

BP tends to break up consonant clusters, if the second consonant is not , , or , by inserting an epenthesis, epenthetic vowel, , which can also be characterized, in some situations, as a schwa. The phenomenon happens mostly in the pretonic position and with the consonant clusters ''ks'', ''ps'', ''bj'', ''dj'', ''dv'', ''kt'', ''bt'', ''ft'', ''mn'', ''tm'' and ''dm'': clusters that are not very common in the language ("afta": ; "opção" : > ).

However, in some regions of Brazil (such as some Northeastern dialects), there has been an opposite tendency to reduce the unstressed vowel into a very weak vowel so ''partes'' or ''destratar'' are often realized similarly to and . Sometimes, the phenomenon occurs even more intensely in unstressed posttonic vowels (except the final ones) and causes the reduction of the word and the creation of new consonant clusters ("prática" ; "máquina" ; "abóbora" ; "cócega" ).

=L-vocalization and suppression of final r