Brandenburg-Prussia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian

The

The

From 1619 to 1640, George William was elector of Brandenburg and duke of Prussia. He strove, but proved unable to break the dominance of the

From 1619 to 1640, George William was elector of Brandenburg and duke of Prussia. He strove, but proved unable to break the dominance of the

During the

During the

Frederick William took over Brandenburg-Prussia in times of a political, economical and demographic crisis caused by the war. Upon his succession, the new elector retired the Brandenburgian army, but had an army raised again in 1643/44.Duchhardt (2006), p. 98 Whether or not Frederick William concluded a truce and neutrality agreement with Sweden is disputed: while a relevant 1641 document exists, it was never ratified and has repeatedly been described as a falsification. However, it is not disputed that he established the growth of Brandenburg-Prussia.Duchhardt (2006), p. 102

At the time, the forces of the Swedish Empire dominated Northern Germany, and along with her ally

Frederick William took over Brandenburg-Prussia in times of a political, economical and demographic crisis caused by the war. Upon his succession, the new elector retired the Brandenburgian army, but had an army raised again in 1643/44.Duchhardt (2006), p. 98 Whether or not Frederick William concluded a truce and neutrality agreement with Sweden is disputed: while a relevant 1641 document exists, it was never ratified and has repeatedly been described as a falsification. However, it is not disputed that he established the growth of Brandenburg-Prussia.Duchhardt (2006), p. 102

At the time, the forces of the Swedish Empire dominated Northern Germany, and along with her ally

In June 1651, Frederick William broke the provisions of the

In June 1651, Frederick William broke the provisions of the

Due to his wartime experiences, Frederick William was convinced that Brandenburg-Prussia would only prevail with a

Due to his wartime experiences, Frederick William was convinced that Brandenburg-Prussia would only prevail with a

The Swedish

The Swedish

In 1672, the

In 1672, the  Polish king

Polish king

On 17 January 1701, Frederick dedicated the royal coat of arms, the Prussian black eagle, and motto, " suum cuique".Beier (2007), p. 162 On 18 January, he crowned himself and his wife Sophie Charlotte in a baroque ceremony in

On 17 January 1701, Frederick dedicated the royal coat of arms, the Prussian black eagle, and motto, " suum cuique".Beier (2007), p. 162 On 18 January, he crowned himself and his wife Sophie Charlotte in a baroque ceremony in

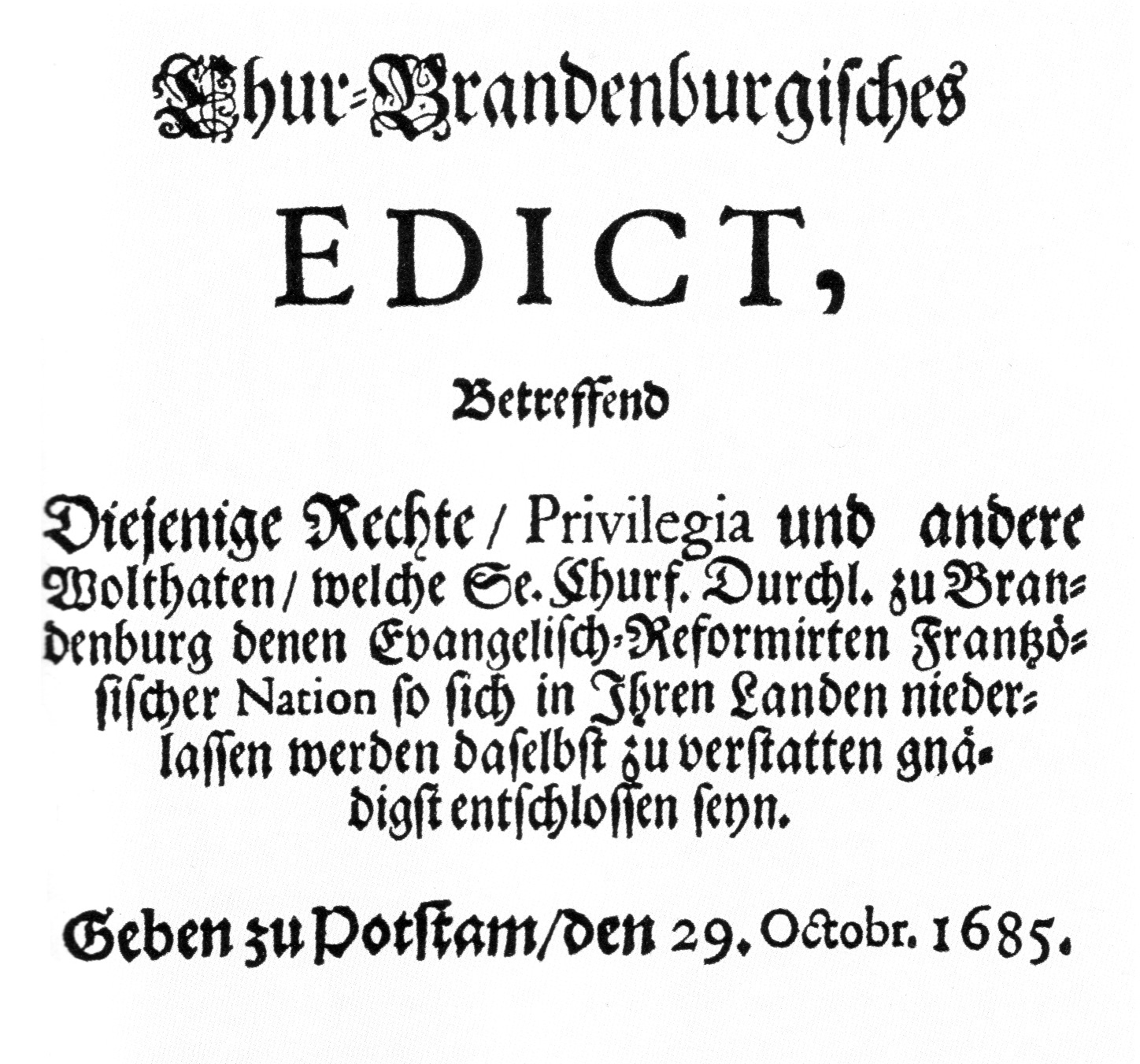

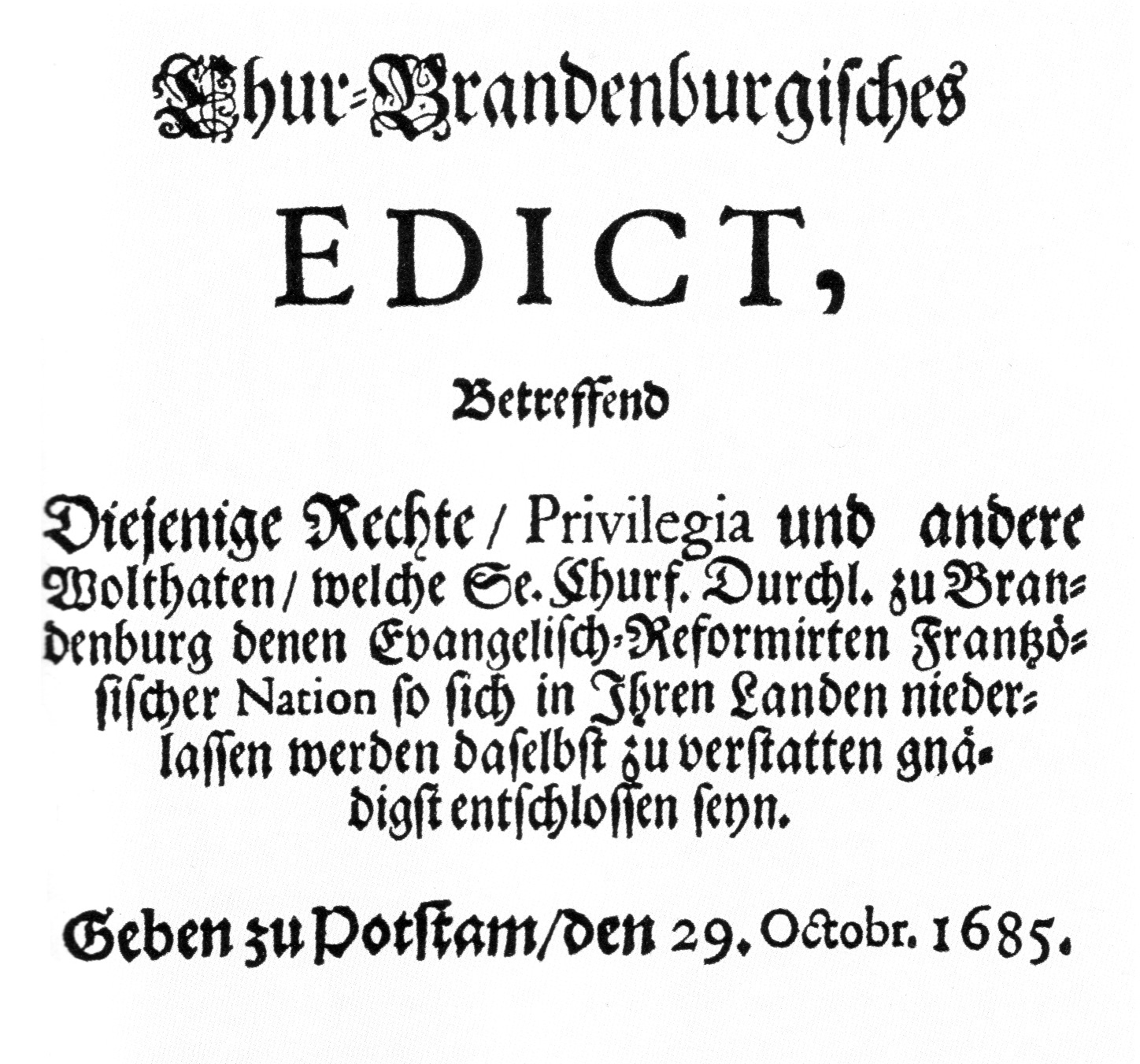

In 1613, John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, John Sigismund converted from Lutheranism to Calvinism, but failed to achieve the conversion of the estates by the rule of cuius regio, eius religio. Thus, on 5 February 1615, he granted the Lutherans religious freedom, while the electors court remained largely Calvinist. When Frederick William I rebuilt Brandenburg-Prussia's war-torn economy, he attracted settlers from all Europe, especially by offering religious asylum, most prominently by the Edict of Potsdam which attracted more than 15,000 Huguenots.Kotulla (2008), p. 264

In 1613, John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, John Sigismund converted from Lutheranism to Calvinism, but failed to achieve the conversion of the estates by the rule of cuius regio, eius religio. Thus, on 5 February 1615, he granted the Lutherans religious freedom, while the electors court remained largely Calvinist. When Frederick William I rebuilt Brandenburg-Prussia's war-torn economy, he attracted settlers from all Europe, especially by offering religious asylum, most prominently by the Edict of Potsdam which attracted more than 15,000 Huguenots.Kotulla (2008), p. 264

In 1679, Raule presented Frederick William a plan to establish colonies in African Guinea, and the elector approved. In July 1680, Frederick William issued respective orders, and two ships were selected to establish trade contacts with African tribes and explore places where colonies could be established.van der Heyden (2001), p. 14 On 17 September, frigate ''Wappen von Brandenburg'' ("Seal of Brandenburg") and ''Morian'' (poetic for "Mohr", "Negro") left for Guinea. The ships reached Guinea in January 1681. Since the crew of the ''Wappen von Brandenburg'' sold a barrel of brandy to Africans in a territory claimed by the Dutch West Indies Company, the latter confiscated the ship in March. The crew of the remaining ship ''Morian'' managed to have three Guinean chieftains sign a contract on 16 May, before the Dutch expelled the vessel from the coastal waters. This treaty, officially declared as trade agreement, included a clause of subjection of the chiefs to Frederick William's overlordship and an agreement allowing Brandenburg-Prussia to establish a fort,van der Heyden (2001), p. 15 and is thus regarded the beginning of the Brandenburg-Prussian colonial era.

To facilitate the colonial expeditions, the Brandenburg African Company was founded on 7 March 1682,van der Heyden (2001), p. 21 initially with its headquarters in

In 1679, Raule presented Frederick William a plan to establish colonies in African Guinea, and the elector approved. In July 1680, Frederick William issued respective orders, and two ships were selected to establish trade contacts with African tribes and explore places where colonies could be established.van der Heyden (2001), p. 14 On 17 September, frigate ''Wappen von Brandenburg'' ("Seal of Brandenburg") and ''Morian'' (poetic for "Mohr", "Negro") left for Guinea. The ships reached Guinea in January 1681. Since the crew of the ''Wappen von Brandenburg'' sold a barrel of brandy to Africans in a territory claimed by the Dutch West Indies Company, the latter confiscated the ship in March. The crew of the remaining ship ''Morian'' managed to have three Guinean chieftains sign a contract on 16 May, before the Dutch expelled the vessel from the coastal waters. This treaty, officially declared as trade agreement, included a clause of subjection of the chiefs to Frederick William's overlordship and an agreement allowing Brandenburg-Prussia to establish a fort,van der Heyden (2001), p. 15 and is thus regarded the beginning of the Brandenburg-Prussian colonial era.

To facilitate the colonial expeditions, the Brandenburg African Company was founded on 7 March 1682,van der Heyden (2001), p. 21 initially with its headquarters in

A second colony was established at the Arguin archipelago off the West African coast (now part of Mauritania). In contrast to the Guinean colony, Arguin had been a colony before: In 1520, Portugal had built a fort on the main island, which with all of Portugal came under Spain, Spanish control in 1580.van der Heyden (2001), p. 39 In 1638 it was conquered by the

A second colony was established at the Arguin archipelago off the West African coast (now part of Mauritania). In contrast to the Guinean colony, Arguin had been a colony before: In 1520, Portugal had built a fort on the main island, which with all of Portugal came under Spain, Spanish control in 1580.van der Heyden (2001), p. 39 In 1638 it was conquered by the

online edition

* Holborn, Hajo. ''A History of Modern Germany.'' Vol 2: ''1648–1840'' (1962) * Hughes, Michael. ''Early Modern Germany, 1477–1806'' (1992) * Sheilagh Ogilvie, Ogilvie, Sheilagh. ''Germany: A New Social and Economic History, Vol. 1: 1450–1630'' (1995) 416pp; ''Germany: A New Social and Economic History, Vol. 2: 1630–1800'' (1996), 448pp * *

Hohenzollerns

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern, Brand ...

between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohenzollern intermarried with the branch ruling the Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the region of Prussia establish ...

, and secured succession upon the latter's extinction in the male line in 1618. Another consequence of the intermarriage was the incorporation of the lower Rhenish

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

principalities of Cleves

Kleve (; traditional en, Cleves ; nl, Kleef; french: Clèves; es, Cléveris; la, Clivia; Low Rhenish: ''Kleff'') is a town in the Lower Rhine region of northwestern Germany near the Dutch border and the River Rhine. From the 11th century ...

, Mark

Mark may refer to:

Currency

* Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, the currency of Bosnia and Herzegovina

* East German mark, the currency of the German Democratic Republic

* Estonian mark, the currency of Estonia between 1918 and 1927

* Finn ...

and Ravensberg after the Treaty of Xanten

The Treaty of Xanten (german: Vertrag von Xanten, links=no) was signed in the Lower Rhine town of Xanten on 12 November 1614 between Wolfgang Wilhelm, Count Palatine of Neuburg and John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, with representatives from ...

in 1614.

The Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

(1618–1648) was especially devastating. The Elector changed sides three times, and as a result Protestant and Catholic armies swept the land back and forth, killing, burning, seizing men and taking the food supplies. Upwards of half the population was killed or dislocated. Berlin and the other major cities were in ruins, and recovery took decades. By the Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought pe ...

, which ended the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

in 1648, Brandenburg gained Minden and Halberstadt

Halberstadt ( Eastphalian: ''Halverstidde'') is a town in the German state of Saxony-Anhalt, the capital of Harz district. Located north of the Harz mountain range, it is known for its old town center that was greatly destroyed by Allied bomb ...

, also the succession in Farther Pomerania ( incorporated in 1653) and the Duchy of Magdeburg (incorporated in 1680). With the Treaty of Bromberg (1657), concluded during the Second Northern War

The Second Northern War (1655–60), (also First or Little Northern War) was fought between Sweden and its adversaries the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1655–60), the Tsardom of Russia ( 1656–58), Brandenburg-Prussia (1657–60), the ...

, the electors were freed of Polish vassalage for the Duchy of Prussia and gained Lauenburg–Bütow and Draheim. The Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1679) expanded Brandenburgian Pomerania to the lower Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows ...

.

The second half of the 17th century laid the basis for Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

to become one of the great players in European politics. The emerging Brandenburg-Prussian military potential, based on the introduction of a standing army

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars or ...

in 1653, was symbolized by the widely noted victories in Warsaw (1656) and Fehrbellin (1675) and by the Great Sleigh Drive

"The Great Sleigh Drive" (german: Die große Schlittenfahrt) from December 1678 to February 1679 was a daring and bold maneuver using sleighs by Frederick William, the Great Elector of Brandenburg-Prussia, to drive Swedish forces out of the Du ...

(1678). Brandenburg-Prussia also established a navy and German colonies in the Brandenburger Gold Coast

The Brandenburger Gold Coast, later Prussian Gold Coast, was a part of the Gold Coast. The Brandenburg colony existed from 1682 to 1721, when King Frederick William I of Prussia sold it for 7200 ducats to the Dutch Republic.

Brandenburger Go ...

and Arguin. Frederick William, known as "The Great Elector", opened Brandenburg-Prussia to large-scale immigration ("''Peuplierung''") of mostly Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

refugees from all across Europe ("''Exulanten''"), most notably Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

immigration following the Edict of Potsdam. Frederick William also started to centralize Brandenburg-Prussia's administration and reduce the influence of the estates.

In 1701, Frederick III, Elector of Brandenburg, succeeded in elevating his status to '' King in Prussia''. This was made possible by the Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the region of Prussia establish ...

's sovereign status outside the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, and approval by the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother ( ...

and other European royals in the course of forming alliances for the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

and the Great Northern War

The Great Northern War (1700–1721) was a conflict in which a coalition led by the Tsardom of Russia successfully contested the supremacy of the Swedish Empire in Northern, Central and Eastern Europe. The initial leaders of the anti-Swe ...

. From 1701 onward, the Hohenzollern domains were referred to as the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

, or simply Prussia. Legally, the personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interli ...

between Brandenburg and Prussia continued until the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. However, by this time the emperor's overlordship over the empire had become a legal fiction

A legal fiction is a fact assumed or created by courts, which is then used in order to help reach a decision or to apply a legal rule. The concept is used almost exclusively in common law jurisdictions, particularly in England and Wales.

Deve ...

. Hence, after 1701, Brandenburg was ''de facto'' treated as part of the Prussian kingdom. Frederick and his successors continued to centralize and expand the state, transforming the personal union of politically diverse principalities typical for the Brandenburg-Prussian era into a system of provinces subordinate to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

.

Establishment under John Sigismund (1618)

The

The Margraviate of Brandenburg

The Margraviate of Brandenburg (german: link=no, Markgrafschaft Brandenburg) was a major principality of the Holy Roman Empire from 1157 to 1806 that played a pivotal role in the history of Germany and Central Europe.

Brandenburg developed out ...

had been the seat of the main branch of the Hohenzollerns, who were prince-elector

The prince-electors (german: Kurfürst pl. , cz, Kurfiřt, la, Princeps Elector), or electors for short, were the members of the electoral college that elected the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

From the 13th century onwards, the princ ...

s in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

, since 1415.Hammer (2001), p. 33 In 1525, by the Treaty of Krakow, the Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the region of Prussia establish ...

was created through partial secularization of the State of the Teutonic Order. It was a vassal of the Kingdom of Poland and was governed by Duke Albert of Prussia, a member of a cadet branch

In history and heraldry, a cadet branch consists of the male-line descendants of a monarch's or patriarch's younger sons ( cadets). In the ruling dynasties and noble families of much of Europe and Asia, the family's major assets— realm, t ...

of the House of Hohenzollern. On behalf of her mother Elisabeth of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollern, Anna Marie of Brunswick-Lüneburg

Anna may refer to:

People Surname and given name

* Anna (name)

Mononym

* Anna the Prophetess, in the Gospel of Luke

* Anna (wife of Artabasdos) (fl. 715–773)

* Anna (daughter of Boris I) (9th–10th century)

* Anna (Anisia) (fl. 1218 to 1221) ...

became Albert's second wife in 1550, and bore him his successor Albert Frederick.Jähnig (2006), p. 65 In 1563, the Brandenburgian branch of the Hohenzollern was granted the right of succession by the Polish crown. Albert Frederick became duke of Prussia after Albert's death in 1568. His mother died in the same year, and thereafter he showed signs of mental disorder. Because of the duke's illness,Jähnig (2006), p. 66 Prussia was governed by Albert's nephew George Frederick of Hohenzollern-Ansbach-Jägersdorf (1577–1603). In 1573, Albert Frederick married Marie Eleonore of Jülich-Cleves-Berg, with whom he had several daughters.

In 1594, Albert Frederick's then 14-year-old daughter Anna

Anna may refer to:

People Surname and given name

* Anna (name)

Mononym

* Anna the Prophetess, in the Gospel of Luke

* Anna (wife of Artabasdos) (fl. 715–773)

* Anna (daughter of Boris I) (9th–10th century)

* Anna (Anisia) (fl. 1218 to 1221) ...

married the son of Joachim Frederick of Hohenzollern-Brandenburg, John Sigismund.Hammer (2001), p. 24 The marriage ensured the right of succession in the Prussian duchy as well as in Cleves

Kleve (; traditional en, Cleves ; nl, Kleef; french: Clèves; es, Cléveris; la, Clivia; Low Rhenish: ''Kleff'') is a town in the Lower Rhine region of northwestern Germany near the Dutch border and the River Rhine. From the 11th century ...

. Upon George Frederick's death in 1603, the regency of the Prussian duchy passed to Joachim Frederick. Also in 1603, the Treaty of Gera was concluded by the members of the House of Hohenzollern, ruling that their territories were not to be internally divided in the future.

The Electors of Brandenburg inherited the Duchy of Prussia upon Albert Frederick's death in 1618,Gotthard (2006), p. 86 but the duchy continued to be held as a fief under the Polish Crown until 1656/7.Hammer (2001), p. 136 Since John Sigismund had suffered a stroke in 1616 and as a consequence was severely handicapped physically as well as mentally, his wife Anna ruled the Duchy of Prussia in his name until John Sigismund died of a second stroke in 1619, aged 47.

George William, 1619–1640

Electorate of Saxony

The Electorate of Saxony, also known as Electoral Saxony (German: or ), was a territory of the Holy Roman Empire from 1356–1806. It was centered around the cities of Dresden, Leipzig and Chemnitz.

In the Golden Bull of 1356, Emperor Charle ...

in the Upper Saxon Circle.Nicklas (2002), pp. 214ff The Brandenburg-Saxon antagonism rendered the defense of the circle ineffective, and it was subsequently overrun by Albrecht von Wallenstein during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

. While George William had claimed neutrality before, the presence of Wallenstein's army forced him to join the Catholic-Imperial camp in the Treaty of Königsberg (1627) and accept garrisons.Gotthard (2006), p. 88 When the Swedish Empire entered the war and advanced into Brandenburg, George William again claimed neutrality, yet Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden

Gustavus Adolphus (9 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">N.S_19_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Old Style and New Style dates">N.S 19 December">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/now ...

compelled George William to join Sweden as an ally by occupying substantial territory in Brandenburg-Prussia and concentrating an army before the town walls of Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

.Gotthard (2006), p. 90 George William did not conclude an alliance, but granted Sweden transit rights, two fortresses and subsidies. Consequently, Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

armies repeatedly ravaged Brandenburg and other Hohenzollern lands.

"The Great Elector", Frederick William, 1640–1688

During the

During the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

, George William was succeeded by Frederick William, born 1620, who became known as "The Great Elector" (''Der Große Kurfürst'').Duchhardt (2006), p. 97 The character of the young elector had been stamped by his Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

nurturer Calcum, a long stay in the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiograph ...

during his grand tour

The Grand Tour was the principally 17th- to early 19th-century custom of a traditional trip through Europe, with Italy as a key destination, undertaken by upper-class young European men of sufficient means and rank (typically accompanied by a tut ...

, and the events of the war, of which a meeting with his uncle Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden

Gustavus Adolphus (9 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">N.S_19_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Old Style and New Style dates">N.S 19 December">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/now ...

in Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

was among the most impressive.

Conclusion of the Thirty Years' War

Frederick William took over Brandenburg-Prussia in times of a political, economical and demographic crisis caused by the war. Upon his succession, the new elector retired the Brandenburgian army, but had an army raised again in 1643/44.Duchhardt (2006), p. 98 Whether or not Frederick William concluded a truce and neutrality agreement with Sweden is disputed: while a relevant 1641 document exists, it was never ratified and has repeatedly been described as a falsification. However, it is not disputed that he established the growth of Brandenburg-Prussia.Duchhardt (2006), p. 102

At the time, the forces of the Swedish Empire dominated Northern Germany, and along with her ally

Frederick William took over Brandenburg-Prussia in times of a political, economical and demographic crisis caused by the war. Upon his succession, the new elector retired the Brandenburgian army, but had an army raised again in 1643/44.Duchhardt (2006), p. 98 Whether or not Frederick William concluded a truce and neutrality agreement with Sweden is disputed: while a relevant 1641 document exists, it was never ratified and has repeatedly been described as a falsification. However, it is not disputed that he established the growth of Brandenburg-Prussia.Duchhardt (2006), p. 102

At the time, the forces of the Swedish Empire dominated Northern Germany, and along with her ally France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Sweden became guarantee power of the Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought pe ...

in 1648. The Swedish aim of controlling the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

by establishing dominions on the coastline ("''dominium maris baltici''") thwarted Frederick William's ambitions to gain control over the Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows ...

estuary with Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

(Szczecin) in Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

.Hammer (2001), p. 19

The Brandenburgian margraves had long sought to expand northwards, connecting land-locked Brandenburg to the Baltic Sea. The Treaty of Grimnitz (1529) guaranteed Brandenburgian succession in the Duchy of Pomerania upon the extinction of the local House of Pomerania

The House of Griffin or Griffin dynasty (german: Greifen; pl, Gryfici, da, Grif) was a dynasty ruling the Duchy of Pomerania from the 12th century until 1637. The name "Griffins" was used by the dynasty after the 15th century and had been tak ...

, and would have come into effect by the death of Pomeranian duke Bogislaw XIV in 1637. By the Treaty of Stettin (1630) however, Bogislaw XIV had also effectively handed over control of the duchy to Sweden, who refused to give in to the Brandenburgian claim. The Peace of Westphalia settled for a partition of the duchy between Brandenburg and Sweden, who determined the exact border in the Treaty of Stettin (1653).Hammer (2001), p. 25 Sweden retained the western part including the lower Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows ...

( Swedish Pomerania), while Brandenburg gained the eastern part ( Farther Pomerania). Frederick William was dissatisfied by this outcome, and the acquisition of the whole Duchy of Pomerania was to become one of the main goals of his foreign policy.

In the Peace of Westphalia, Frederick William was compensated for Western Pomerania

Historical Western Pomerania, also called Cispomerania, Fore Pomerania, Front Pomerania or Hither Pomerania (german: Vorpommern), is the western extremity of the historic region of Pomerania forming the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, West ...

with the secularized bishoprics of Halberstadt

Halberstadt ( Eastphalian: ''Halverstidde'') is a town in the German state of Saxony-Anhalt, the capital of Harz district. Located north of the Harz mountain range, it is known for its old town center that was greatly destroyed by Allied bomb ...

and Minden and the right of succession to the likewise secularized Archbishopric of Magdeburg

The Archbishopric of Magdeburg was a Roman Catholic archdiocese (969–1552) and Prince-Archbishopric (1180–1680) of the Holy Roman Empire centered on the city of Magdeburg on the Elbe River.

Planned since 955 and established in 968, the R ...

. With Halberstadt, Brandenburg-Prussia also gained several smaller territories: the Lordship of Derenburg, the County of Regenstein, the Lordship of Klettenberg and the Lordship of Lohra. This was primarily due to French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

efforts to counterbalance the power of the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

emperor by strengthening the Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern, Brandenb ...

, and while Frederick William valued these territories lower than Western Pomerania, they became step-stones for the creation of a closed, dominant realm in Germany in the long run.

Devastation

Of all Brandenburg-Prussian territories, the Electorate of Brandenburg was among the most devastated at the end of the Thirty Years' War. Already before the war, the population density and wealth in the electorate had been low compared to other territories of the empire, and the war had destroyed 60 towns, 48 castles and about 5,000 villages. An average of 50% of the population was dead, in some regions only 10% survived.Hammer (2001), p. 20 The rural population, due to deaths and flight to the towns, had dropped from 300,000 before the war to 75,000 thereafter. In the important towns of Berlin-Cölln and Frankfurt an der Oder, the population drop was one third and two-thirds, respectively. Some of the territories gained after the war were likewise devastated: inPomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

, only one third of the population survived, and Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; nds, label=Low Saxon, Meideborg ) is the capital and second-largest city of the German state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is situated at the Elbe river.

Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archdiocese of Magdebu ...

, once among the wealthiest cities of the empire, was burned down with most of the population slain. Least hit were the Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the region of Prussia establish ...

, which was only peripherally involved in the war, and Minden.

Despite efforts to resettle the devastated territories, it took some of them until the mid-18th century to reach the pre-war population density.

Cow War

In June 1651, Frederick William broke the provisions of the

In June 1651, Frederick William broke the provisions of the Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought pe ...

by invading Jülich-Berg, bordering his possessions in Cleves-Mark at the lower Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

river.Gabel (1998), p. 468 The Treaty of Xanten

The Treaty of Xanten (german: Vertrag von Xanten, links=no) was signed in the Lower Rhine town of Xanten on 12 November 1614 between Wolfgang Wilhelm, Count Palatine of Neuburg and John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, with representatives from ...

, which had ended the War of the Jülich succession between Brandenburg and the count palatine

A count palatine (Latin ''comes palatinus''), also count of the palace or palsgrave (from German ''Pfalzgraf''), was originally an official attached to a royal or imperial palace or household and later a nobleman of a rank above that of an ord ...

s in 1614, had partitioned the once united Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg

The so-called United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg was a territory in the Holy Roman Empire between 1521 and 1666, formed from the personal union of the duchies of Jülich, Cleves and Berg.

The name was resurrected after the Congress of Vie ...

among the belligerents, and Jülich-Berg was since ruled by the Catholic counts of Palatinate-Neuburg

Palatinate-Neuburg (german: Herzogtum Pfalz-Neuburg) was a territory of the Holy Roman Empire, founded in 1505 by a branch of the House of Wittelsbach. Its capital was Neuburg an der Donau. Its area was about 2,750 km², with a population of ...

. After the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

, Wolfgang William, Count Palatine of Neuburg, disregarded a 1647 agreement with Frederick William which had favored the Protestants in the duchies, while Frederick William insisted that the agreement be upheld. Besides these religious motives, Frederick William's invasion also aimed at territorial expansion.

The conflict had the potential to spark another international warGabel (1998), p. 469 since Wolfgang William wanted to have the still not demobilized army of Lorraine, which continued to operate in the region despite the Peace of Westphalia, to intervene on his side, and Frederick William sought support of the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiograph ...

. The latter however followed a policy of neutrality and refused to aid Frederick William's campaign, which was furthermore opposed by the Imperial estates as well as the local ones. Politically isolated, Frederick William aborted the campaign after the Treaty of Cleves negotiated by Imperial mediators in October 1651. The underlying religious dispute was only solved in 1672. While military confrontations were avoided and the Brandenburg-Prussian army was primarily occupied with stealing cattle (hence the name), it considerably lowered Frederick William's reputation.Duchhardt (2006), p. 103

Standing Army

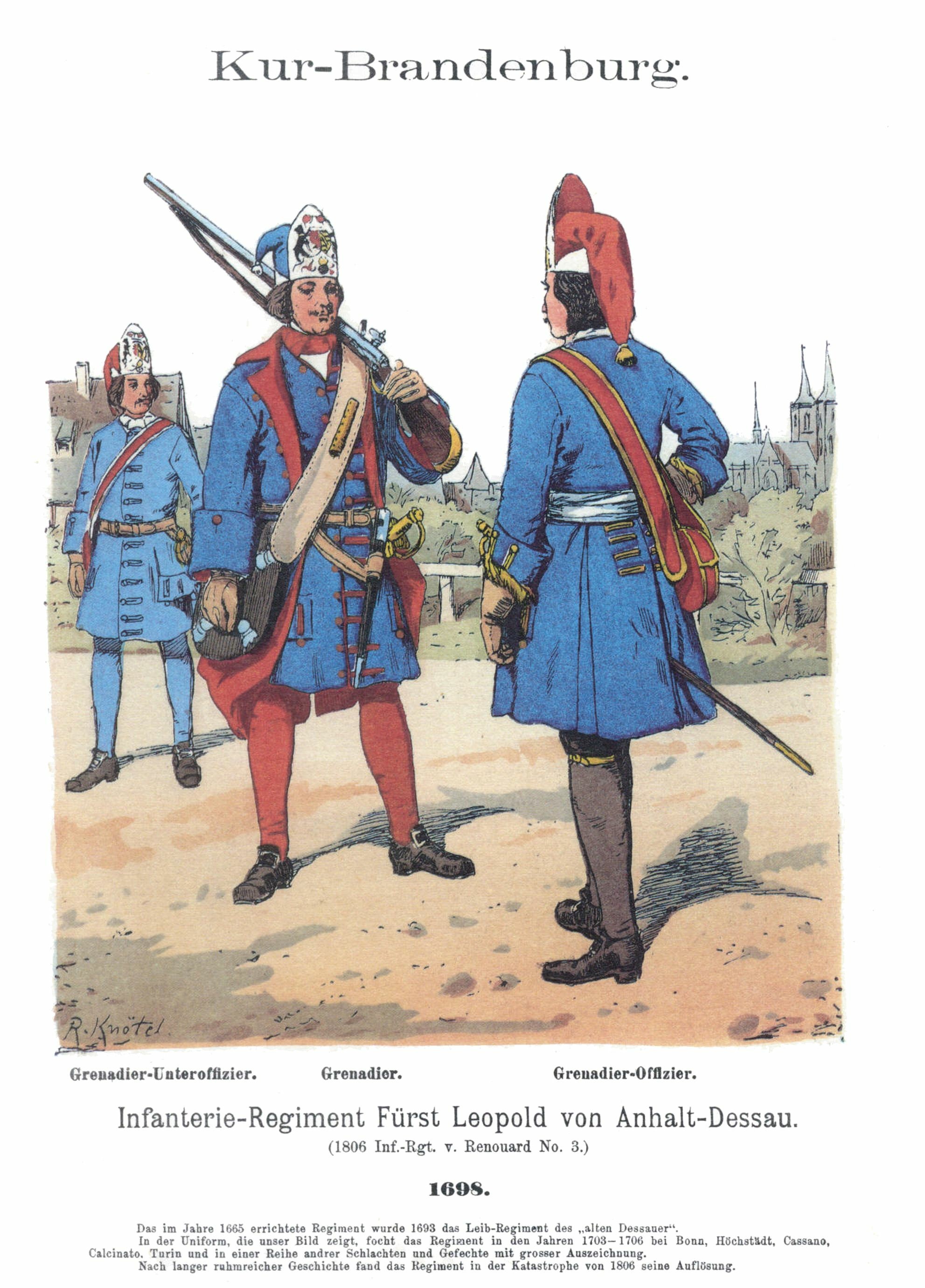

Due to his wartime experiences, Frederick William was convinced that Brandenburg-Prussia would only prevail with a

Due to his wartime experiences, Frederick William was convinced that Brandenburg-Prussia would only prevail with a standing army

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars or ...

.Kotulla (2008), p. 265 Traditionally, raising and financing army reserves

A military reserve force is a military organization whose members have military and civilian occupations. They are not normally kept under arms, and their main role is to be available when their military requires additional manpower. Reserve f ...

was a privilege of the estates, yet Frederick William envisioned a standing army financed independently of the estates. He succeeded in getting the consent and necessary financial contributions of the estates in a ''landtag'' decree of 26 July 1653. In turn, he confirmed several privileges of the knights, including tax exemption, assertion of jurisdiction and police powers on their estates (''Patrimonialgerichtsbarkeit'') and the upholding of serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

(''Leibeigenschaft'', ''Bauernlegen'').Kotulla (2008), p. 266

Initially, the estates' contributions were limited to six years, yet the Frederick William obliged the estates to continue the payments thereafter and created a dedicated office to collect the contributions. The contributions were confirmed by the estates in 1662, but transformed in 1666 by decree from a real estate tax to an excise tax. Since 1657, the towns had to contribute not soldiers, but monetary payments to the army, and since 1665, the estates were able to free themselves from contributing soldiers by additional payments. The initial army size of 8,000 menKotulla (2008), p. 267 had risen to 25,000 to 30,000 men by 1688. By then, Frederick William had also accomplished his second goal, to finance the army independently of the estates. By 1688, these military costs amounted to considerable 1,500,000 talers or half of the state budget. Ensuring a solid financial basis for the army, undisturbed by the estates, was the foremost objective of Frederick William's administrative reforms.Duchhardt (2006), p. 101 He regarded military success as the only way to gain international reputation.

Second Northern War

The Swedish

The Swedish invasion

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing ...

of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

in the following year started the Second Northern War

The Second Northern War (1655–60), (also First or Little Northern War) was fought between Sweden and its adversaries the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1655–60), the Tsardom of Russia ( 1656–58), Brandenburg-Prussia (1657–60), the ...

. Frederick William offered protection to the Royal Prussian towns in the Treaty of Rinsk

The treaty of Rinsk, concluded on 2 November ( O.S.) / 12 November ( N.S.) 1655, was a Ducal-Royal Prussian alliance during the Second Northern War.Frost (2000), p. 171 Frederick William I, Elector of Brandenburg and duke of Prussia, and the nob ...

, but had to yield Swedish military supremacy and withdraw to his Prussian duchy. Pursued by Swedish forces to the Prussian capital, Frederick William made peace and allied with Sweden, taking the Duchy of Prussia and Ermland (Ermeland, Warmia) as fiefs from Charles X Gustav of Sweden

Charles X Gustav, also Carl Gustav ( sv, Karl X Gustav; 8 November 1622 – 13 February 1660), was King of Sweden from 1654 until his death. He was the son of John Casimir, Count Palatine of Zweibrücken-Kleeburg and Catherine of Sweden. Afte ...

in the Treaty of Königsberg in January 1656.Hammer (2001), p. 135 The alliance proved victorious in the Battle of Warsaw in June, enhancing the elector's international reputation. Continued pressure on Charles X Gustav resulted in him conceding full sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

in Ducal Prussia and Ermland to Frederick William by the Treaty of Labiau

The Treaty of Labiau was a treaty signed between Frederick William I, Elector of Brandenburg and Charles X Gustav of Sweden on 10 November ( O.S.) / 20 November ( N.S.) 1656 in Labiau (now Polessk). With several concessions, the most important be ...

in November to ensure the maintenance of the alliance.Frost (2000), p.178 The Treaty of Radnot, concluded in December by Sweden and her allies, further awarded Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Großpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed by Kalisz, the oldest cit ...

to Brandenburg-Prussia in case of a victory.

When the anti-Swedish coalition however gained the upper hand, Frederick William changed sides when Polish king John II Casimir Vasa confirmed his sovereignty in Prussia, but not in Ermland, in the Treaty of Wehlau-Bromberg in 1657. The duchy would legally revert to Poland if the Hohenzollern dynastic line became extinct. Hohenzollern sovereignty in the Prussian duchy was confirmed in the Peace of Oliva, which ended the war in 1660. Brandenburg-Prussian campaigns in Swedish Pomerania did not result in permanent gains.

Dutch and Scanian Wars

Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, also known as the Dutch War (french: Guerre de Hollande; nl, Hollandse Oorlog), was fought between France and the Dutch Republic, supported by its allies the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark-Nor ...

broke out, with Brandenburg-Prussia involved as an ally of the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiograph ...

. This alliance was based on a treaty of 1669, and resulted in French occupation of Brandenburg-Prussian Cleves

Kleve (; traditional en, Cleves ; nl, Kleef; french: Clèves; es, Cléveris; la, Clivia; Low Rhenish: ''Kleff'') is a town in the Lower Rhine region of northwestern Germany near the Dutch border and the River Rhine. From the 11th century ...

.Duchhardt (2006), p. 105 In June 1673, Frederick William abandoned the Dutch alliance and concluded a subsidy treaty with France, who in return withdrew from Cleves. When the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

declared war on France, a so-called '' Reichskrieg'', Brandenburg-Prussia again changed sides and joined the imperial forces. France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

pressured her ally Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic countries, Nordic c ...

to relieve her by attacking Brandenburg-Prussia from the north.Frost (2000), p. 210 Charles XI of Sweden, dependent on French subsidies, reluctantly occupied the Brandenburgian Uckermark in 1674, starting the German theater of the Scanian War

The Scanian War ( da, Skånske Krig, , sv, Skånska kriget, german: Schonischer Krieg) was a part of the Northern Wars involving the union of Denmark–Norway, Brandenburg and Sweden. It was fought from 1675 to 1679 mainly on Scanian soil, ...

(Brandenburg-Swedish War). Frederick William reacted promptly by marching his armies from the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

to northern Brandenburg, and encountered the rear of the Swedish army, which was in the process of crossing a swamp, in the Battle of Fehrbellin

The Battle of Fehrbellin was fought on June 18, 1675 (Julian calendar date, June 28th, Gregorian), between Swedish and Brandenburg-Prussian troops. The Swedes, under Count Waldemar von Wrangel (stepbrother of '' Riksamiral'' Carl Gustaf Wrang ...

(1675).Frost (2000), pp. 210, 213 Though a minor skirmish from a military perspective, Frederick William's victory turned out to be of huge symbolic significance. The "Great Elector" started a counter-offensive, pursuing the retreating Swedish forces through Swedish Pomerania.Frost (2000), p. 212

Polish king

Polish king John III Sobieski

John III Sobieski ( pl, Jan III Sobieski; lt, Jonas III Sobieskis; la, Ioannes III Sobiscius; 17 August 1629 – 17 June 1696) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1674 until his death in 1696.

Born into Polish nobility, Sobi ...

planned to restore Polish suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is ca ...

over the Duchy of Prussia, and for this purpose concluded an alliance with France on 11 June 1675.Leathes et al. (1964), p. 354 France promised assistance and subsidies, while Sobieski in turn allowed French recruitment in Poland-Lithuania and promised to aid Hungarian rebel forces who were to distract the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

from their war against France. For this plan to work out, Poland-Lithuania had to first conclude her war against the Ottoman Empire, which French diplomacy despite great efforts failed to achieve.Leathes et al. (1964), p. 355 Furthermore, Sobieski was opposed by the Papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

, by Polish gentry who saw the Ottomans as the greater threat, and by Polish magnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

s bribed by Berlin and Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

.Gieysztor et al. (1979), pp. 220ff Inner-Polish Catholic opposition to an intervention on the Protestant Hungarian rebels' side added to the resentments.Leathes et al. (1964), p. 356 Thus, while Treaty of Żurawno

The Treaty of Żurawno ( tr, İzvança Antlaşması; pl, rozejm w Żurawnie) was signed on 17 October 1676 in the town of Żurawno (or ''İzvança'', as it was called during the Ottoman occupation of Podolia), in the aftermath of the Battle of � ...

ended the Polish-Ottoman war in 1676, Sobieski sided with the emperor instead, and the plan for a Prussian campaign was dropped.

By 1678, Frederick William had cleared Swedish Pomerania and occupied most of it, with the exception of Rügen

Rügen (; la, Rugia, ) is Germany's largest island. It is located off the Pomeranian coast in the Baltic Sea and belongs to the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

The "gateway" to Rügen island is the Hanseatic city of Stralsund, where ...

which was held by Denmark–Norway

Denmark–Norway ( Danish and Norwegian: ) was an early modern multi-national and multi-lingual real unionFeldbæk 1998:11 consisting of the Kingdom of Denmark, the Kingdom of Norway (including the then Norwegian overseas possessions: the Faroe ...

. This was followed by another success against Sweden, when Frederick William cleared Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

of Swedish forces in what became known as the Great Sleigh Drive

"The Great Sleigh Drive" (german: Die große Schlittenfahrt) from December 1678 to February 1679 was a daring and bold maneuver using sleighs by Frederick William, the Great Elector of Brandenburg-Prussia, to drive Swedish forces out of the Du ...

. However, when Louis XIV of France

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of ...

concluded the Dutch War by the Nijmegen treaties, he marched his armies east to relieve his Swedish ally, and forced Frederick William to basically return to the ''status quo ante bellum

The term ''status quo ante bellum'' is a Latin phrase meaning "the situation as it existed before the war".

The term was originally used in treaties to refer to the withdrawal of enemy troops and the restoration of prewar leadership. When use ...

'' by the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1679). Though the Scanian War resulted only in minor territorial gains, attaching a small strip of the Swedish Pomeranian right bank of the lower Oder to Brandenburg-Prussian Pomerania, the war resulted in a huge gain of prestige for the elector.

Frederick III (I), 1688–1713

Frederick III of Brandenburg

Frederick I (german: Friedrich I.; 11 July 1657 – 25 February 1713), of the Hohenzollern dynasty, was (as Frederick III) Elector of Brandenburg (1688–1713) and Duke of Prussia in personal union (Brandenburg-Prussia). The latter function ...

, since 1701 also Frederick I of Prussia, was born in Königsberg

Königsberg (, ) was the historic Prussian city that is now Kaliningrad, Russia. Königsberg was founded in 1255 on the site of the ancient Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teutonic Knights during the Northern Crusades, and was ...

in 1657.Hammer (2001), p. 104 Already in the last years of the reign of his father, the friendly relations with France established after Saint Germain (1679) had cooled, not least because of the Huguenot question.Neugebauer (2006), p. 126 In 1686, Frederick William turned toward the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother ( ...

, with whom he concluded an alliance on 22 December 1686. For this alliance, Frederick William relinquished rights on Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

in favor of the Habsburgs, and in turn received the Silesian County of Schwiebus which bordered the Neumark

The Neumark (), also known as the New March ( pl, Nowa Marchia) or as East Brandenburg (), was a region of the Margraviate of Brandenburg and its successors located east of the Oder River in territory which became part of Poland in 1945.

Call ...

. Frederick III, present at the negotiations as crown prince, assured the Habsburgs of the continuation of the alliance once he was in power, and secretly concluded an amendment to return Schwiebus to the Habsburgs, which he eventually did in 1694. Throughout his reign, Brandenburg-Prussia remained a Habsburg ally and repeatedly deployed troops to fight against France. In 1693, Frederick III began to sound out the possibility of an elevation of his status at the Habsburg court in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, and while the first attempt was unsuccessful, elevation to a king remained the central goal on his agenda.

The envisioned status elevation did not merely serve a decorative purpose, but was regarded a necessity to prevail in political competition. Though Frederick III held the elevated status of a prince elector, this status was also gained by Maximilian I of Bavaria in 1623, during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

, also by the Elector of the Palatinate

The counts palatine of Lotharingia /counts palatine of the Rhine /electors of the Palatinate (german: Kurfürst von der Pfalz) ruled some part of Rhine area in the Kingdom of Germany and the Holy Roman Empire from 915 to 1803. The title was a kind ...

in the Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought pe ...

(1648), and by Ernest Augustus of the House of Hanover

The House of Hanover (german: Haus Hannover), whose members are known as Hanoverians, is a European royal house of German origin that ruled Hanover, Great Britain, and Ireland at various times during the 17th to 20th centuries. The house or ...

in 1692.Neuhaus (2003), p. 22 Thus, the formerly exclusive club of the prince-electors now had nine members, six of whom were secular princes, and further changes seemed possible.Neugebauer (2006), p. 127 Within the circle of prince-electors, August the Strong

Augustus II; german: August der Starke; lt, Augustas II; in Saxony also known as Frederick Augustus I – Friedrich August I (12 May 16701 February 1733), most commonly known as Augustus the Strong, was Elector of Saxony from 1694 as well as Ki ...

, Elector of Saxony, had secured the Polish crown in 1697, and the House of Hanover had secured succession of the British throne. From Frederick III's perspective, stagnation in status meant loss of power, and this perspective seemed to be confirmed when the European royals ignored Brandenburg-Prussia's claims in the Treaty of Rijswijk (1697).

Frederick decided to raise the Duchy of Prussia to a kingdom. Within the Holy Roman Empire, no one could call himself king except the emperor and the king of Bohemia. However, Prussia was outside the empire, and the Hohenzollerns were fully sovereign over it. The practicability of this plan was doubted by some of his advisors, and in any case the crown was only valuable if recognized by the European nobility, most important the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

. In 1699, negotiations were renewed with emperor Leopold I, who in turn was in need of allies since the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

was about to break out. On 16 November 1700, the emperor approved Frederick's coronation in the Crown Treaty. With respect to Poland-Lithuania, who held the provinces of Royal Prussia and Ermland, it was agreed that Frederick would call himself King in Prussia, instead of King ''of'' Prussia.Weber (2003), p. 13 Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

and the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiograph ...

, for similar reasons as the emperor, accepted Frederick's elevation prior to the coronation.Weber (2003), p. 12

On 17 January 1701, Frederick dedicated the royal coat of arms, the Prussian black eagle, and motto, " suum cuique".Beier (2007), p. 162 On 18 January, he crowned himself and his wife Sophie Charlotte in a baroque ceremony in

On 17 January 1701, Frederick dedicated the royal coat of arms, the Prussian black eagle, and motto, " suum cuique".Beier (2007), p. 162 On 18 January, he crowned himself and his wife Sophie Charlotte in a baroque ceremony in Königsberg Castle

The Königsberg Castle (german: Königsberger Schloss, russian: Кёнигсбергский замок, Konigsbergskiy zamok) was a castle in Königsberg, Germany (since 1946 Kaliningrad, Russia), and was one of the landmarks of the East Pruss ...

.

On 28 January, Augustus the Strong congratulated Frederick, yet not as Polish king, but as Saxon elector. In February, Denmark–Norway

Denmark–Norway ( Danish and Norwegian: ) was an early modern multi-national and multi-lingual real unionFeldbæk 1998:11 consisting of the Kingdom of Denmark, the Kingdom of Norway (including the then Norwegian overseas possessions: the Faroe ...

accepted Frederick's elevation in hope of an ally in the Great Northern War

The Great Northern War (1700–1721) was a conflict in which a coalition led by the Tsardom of Russia successfully contested the supremacy of the Swedish Empire in Northern, Central and Eastern Europe. The initial leaders of the anti-Swe ...

, and the Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia or Tsardom of Rus' also externally referenced as the Tsardom of Muscovy, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of Tsar by Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter I ...

likewise approved in 1701. Most princes of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

followed.Neugebauer (2006), p. 128 Charles XII of Sweden accepted Frederick as Prussian king in 1703. In 1713, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Spain also accepted Frederick's royal status.

The coronation was not accepted by the Teutonic Order, who despite the secularization of the Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the region of Prussia establish ...

Treaty of Cracow, in 1525 upheld claims to the region. The Grand Masters of the Teutonic Knights, Grand Master protested at the emperor's court, and the pope sent a circular to all Roman Catholic Church, Catholic regents to not accept Frederick's royal status. Until 1787, papal documents continued to speak of the Prussian kings as "Margraves of Brandenburg". Neither did the Polish–Lithuanian nobility accept Frederick's royal status, seeing the Polish province of Royal Prussia endangered, and only in 1764Weber (2003), p. 14 was the Prussian kingship accepted.Weber (2003), p. 15

Since Brandenburg was still legally part of the Holy Roman Empire, the personal union between Brandenburg and Prussia technically continued until the empire's dissolution in 1806. However, the emperor's power was only nominal by this time, and Brandenburg soon came to be treated as a ''de facto'' province of the Prussian kingdom. Although Frederick was still only an elector within the portions of his domain that were part of the empire, he only acknowledged the emperor's overlordship over them in a formal way.

Administration

In the mid-16th century, the margraves of Brandenburg had become highly dependent on the estates (counts, lords, knights and towns, no prelates due to the Protestant Reformation in 1538).Kotulla (2008), p. 262 The margraviate's liabilities and tax income as well as the margrave's finances were controlled by the ''Kreditwerk'', an institution not controlled by the elector, and the ''Großer Ausschuß'' ("Great Committee") of the estates.Kotulla (2008), p. 263 This was due to concessions made by Joachim II, Elector of Brandenburg, Joachim II in 1541 in turn for financial aid by the estates, however, the ''Kreditwerk'' went bankrupt between 1618 and 1625. The margraves further had to yield the veto of the estates in all issues concerning the "better or worse of the country", in all legal commitments, and in all issues concerning pawn or sale of the elector's real property. To reduce the influence of the estates, Joachim Frederick, Elector of Brandenburg, Joachim Frederick in 1604 created a council called ''Geheimer Rat für die Kurmark'' ("Privy Council for the Electorate"), which instead of the estates was to function as the supreme advisory council for the elector. While the council was permanently established in 1613, it failed to gain any influence until 1651 due to theThirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

.

Until after the Thirty Years' War, the territories of Brandenburg-Prussia were politically independent from each other, connected only by the common feudal superior. Frederick William I, Elector of Brandenburg, Frederick William, who envisioned the transformation of the personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interli ...

into a real union, started to centralize the Brandenburg-Prussian government with an attempt to establish the ''Geheimer Rat'' as a central authority for all territories in 1651, but this project proved to be unfeasible. Instead, the elector continued to appoint a governor (''Kurfürstlicher Rat'') for each territory, who in most cases was a member of the ''Geheimer Rat''. The most powerful institution in the territories remained the governments of the estates (''Landständische Regierung'', named ''Oberratsstube'' in Prussia and ''Geheime Landesregierung'' in Mark and Cleves), which were the highest government agencies regarding jurisdiction, finances and administration. The elector attempted to balance the estates' governments by creating ''Amtskammer'' chambers to administer and coordinate the elector's domains, tax income and privileges. Such chambers were introduced in Brandenburg in 1652, in Cleves and Mark in 1653, in Pomerania in 1654, in Prussia in 1661 and in Magdeburg in 1680. Also in 1680, the ''Kreditwerk'' came under the aegis of the elector.

Frederick William's excise tax (''Akzise''), which since 1667 replaced the property tax raised in Brandenburg for Brandenburg-Prussia's standing army with the estates' consent, was raised by the elector without consultation of the estates. The conclusion of the Second Northern War

The Second Northern War (1655–60), (also First or Little Northern War) was fought between Sweden and its adversaries the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1655–60), the Tsardom of Russia ( 1656–58), Brandenburg-Prussia (1657–60), the ...

had strengthened the elector politically, enabling him to reform the constitution of Cleves and Mark in 1660 and 1661 to introduce officials loyal to him and independent of the local estates. In the Duchy of Prussia, he confirmed the traditional privileges of the estates in 1663, but the latter accepted the caveat that these privileges were not to be used to interfere with the exertion of the elector's sovereignty. As in Brandenburg, Frederick William ignored the privilege of the Prussian estates to confirm or veto taxes raised by the elector: while in 1656, an ''Akzise'' was raised with the estates' consent, the elector by force collected taxes not approved by the Prussian estates for the first time in 1674. Since 1704, the Prussian estates had de facto relinquished their right to approve the elector's taxes while formally still entitled to do so. In 1682, the elector introduced an ''Akzise'' to Pomerania and in 1688 to Magdeburg, while in Cleves and Mark an ''Akzise'' was introduced only between 1716 and 1720. Due to Frederick William's reforms, the state income increased threefold during his reign, and the tax burden per subject reached a level twice as high as in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

.Duchhardt (2006), p. 108

Under the rule of Frederick I of Prussia, Frederick III (I), the Brandenburg Prussian territories were de facto reduced to provinces of the Kingdom of Prussia, monarchy. Frederick William's testament would have divided Brandenburg-Prussia among his sons, yet firstborn Frederick III with the emperor's backing succeeded in becoming the sole ruler based on the Treaty of Gera, which forbade a division of Hohenzollern territories.Kotulla (2008), p. 269 In 1689, a new central chamber for all Brandenburg-Prussian territories was created, called ''Geheime Hofkammer'' (since 1713: ''Generalfinanzdirektorium'').Kotulla (2008), p. 270 This chamber functioned as a superior agency of the territories' ''Amtskammer'' chambers. The General War Commissariat (''Generalkriegskommissariat'') emerged as a second central agency, superior to the local ''Kriegskommissariat'' agencies initially concerned with the administration of the army, but until 1712 transformed into an agency also concerned with general tax and police tasks.

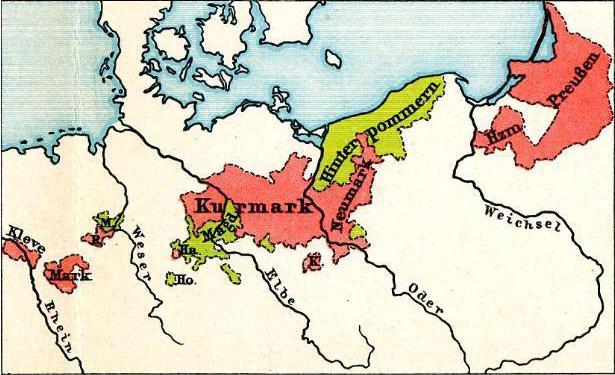

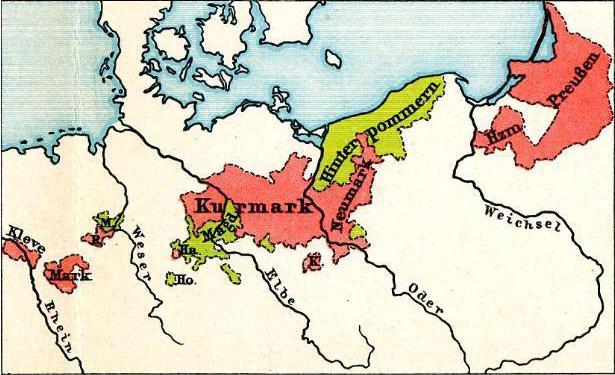

Map

List of territories

''(Kotulla (2008), p. 261)''Religion and immigration

In 1613, John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, John Sigismund converted from Lutheranism to Calvinism, but failed to achieve the conversion of the estates by the rule of cuius regio, eius religio. Thus, on 5 February 1615, he granted the Lutherans religious freedom, while the electors court remained largely Calvinist. When Frederick William I rebuilt Brandenburg-Prussia's war-torn economy, he attracted settlers from all Europe, especially by offering religious asylum, most prominently by the Edict of Potsdam which attracted more than 15,000 Huguenots.Kotulla (2008), p. 264

In 1613, John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, John Sigismund converted from Lutheranism to Calvinism, but failed to achieve the conversion of the estates by the rule of cuius regio, eius religio. Thus, on 5 February 1615, he granted the Lutherans religious freedom, while the electors court remained largely Calvinist. When Frederick William I rebuilt Brandenburg-Prussia's war-torn economy, he attracted settlers from all Europe, especially by offering religious asylum, most prominently by the Edict of Potsdam which attracted more than 15,000 Huguenots.Kotulla (2008), p. 264

Navy and colonies

Brandenburg-Prussia established a navy and colonies during the reign of Frederick William. The "Great Elector" had spent part of his childhood at the Duchy of Pomerania, Pomeranian court and port cities of Wolgast (1631–1633) andStettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

(1633–1635), and afterwards studied at the Dutch Republic, Dutch universities of University of Leyden, Leyden and University of The Hague, The Hague (1635–1638).van der Heyden (2001), p. 8 When Frederick William became elector in 1640, he invited Dutch engineers to Brandenburg, sent Brandenburgian engineers to study in the Netherlands, and in 1646 married educated Countess Luise Henriette of Nassau, Luise Henriette of the Dutch House of Orange-Nassau. After the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

, Frederick William tried to acquire finances to rebuild the country by participating in oversea trade, and attempted to found a Brandenburg-Prussian East Indies Company.van der Heyden (2001), p. 9 He engaged former Dutch admiral Aernoult Gijsels van Lier as advisor and tried to persuade the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

and princes of the empire to participate.van der Heyden (2001), p. 10 The emperor, however, declined the request as he considered it dangerous to disturb the interest of the other European powers.van der Heyden (2001), p. 11 In 1651, Frederick William bought Denmark–Norway, Danish Fort Dansborg and Tranquebar for 120,000 reichstalers. As Frederick William was unable to raise this sum, he asked several people and Hanseatic League, Hanseatic towns to invest in the project, but since none of these were able or willing to give sufficient money, the treaty with Denmark was nullified in 1653.

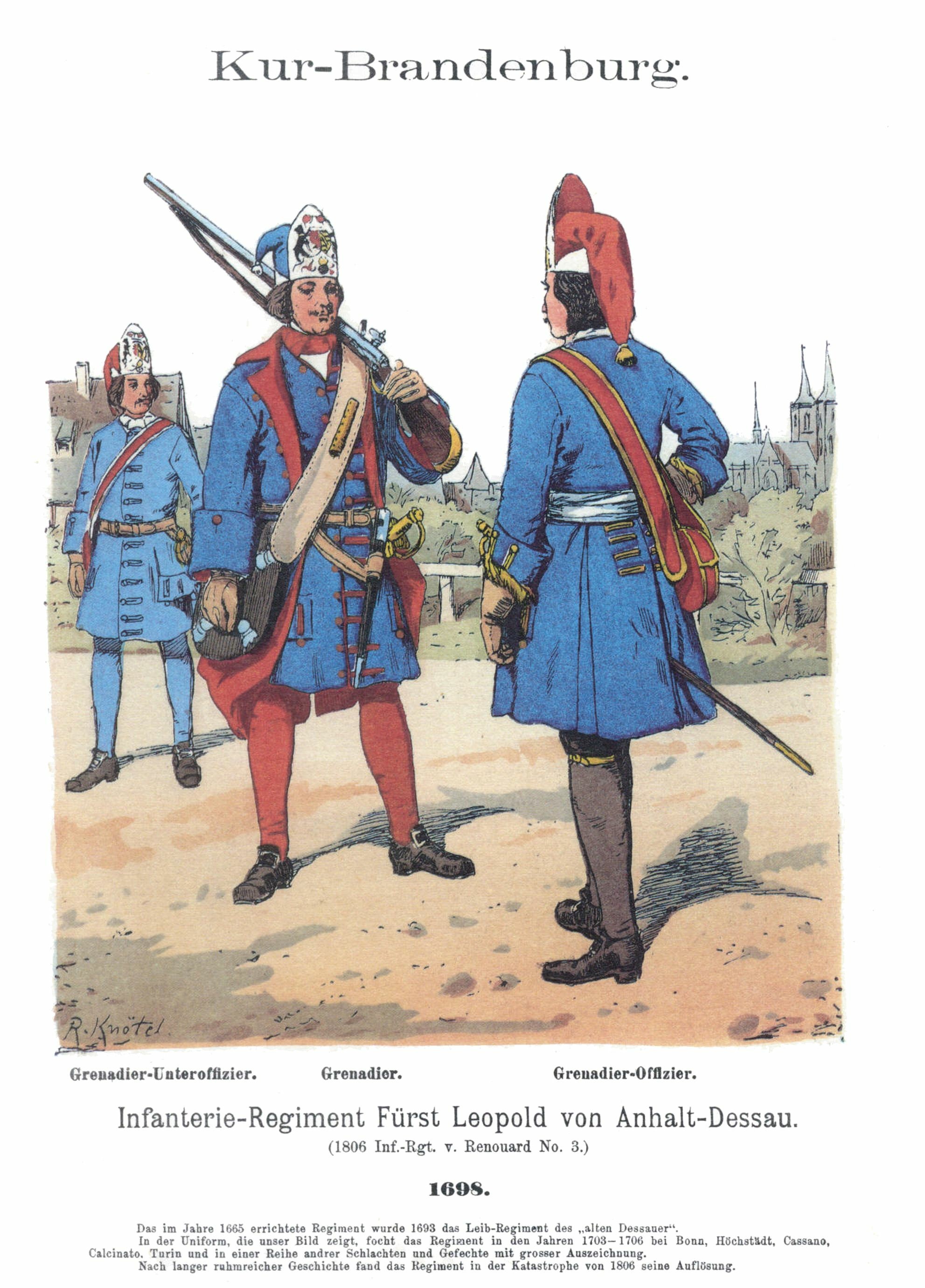

Army

In 1675, after the Battle of Fehrbellin, victory at Fehrbellin and the Brandenburg-Prussian advance in Swedish Pomerania during theScanian War

The Scanian War ( da, Skånske Krig, , sv, Skånska kriget, german: Schonischer Krieg) was a part of the Northern Wars involving the union of Denmark–Norway, Brandenburg and Sweden. It was fought from 1675 to 1679 mainly on Scanian soil, ...

, Frederick William decided to establish a navy. He engaged Dutch merchant and shipowner Benjamin Raule as his advisor, who after a first personal meeting with Frederick William in 1675 settled in Brandenburg in 1676 and became the major figure of Brandenburg-Prussia's emerging naval and colonial enterprise. The Brandenburg-Prussian navy was established from ten ships which Frederick William leased from Raule, and achieved first successes in the war against Sweden supporting the Siege of Stralsund (1678), siege of Stralsund and Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

and the invasion of Rügen

Rügen (; la, Rugia, ) is Germany's largest island. It is located off the Pomeranian coast in the Baltic Sea and belongs to the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

The "gateway" to Rügen island is the Hanseatic city of Stralsund, where ...

.van der Heyden (2001), p. 12 In Pillau (now Baltiysk) on the East Prussian coast, Raule established shipyards and enlarged the port facilities.

After the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1679), the navy was used to hijack Swedish ships in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

, and in 1680, six Brandenburg-Prussian vessels captured the Spain, Spanish vessel ''Carolus Secundus'' near Ostend to pressure Spain to pay promised subsidies. The Spanish ship was renamed ''Markgraf von Brandenburg'' ("Margrave of Brandenburg") and became the flagship of an Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic fleet that was ordered to capture Spanish vessels carrying silver; it was not successful in this mission. In the following years, the navy was expanded, and the policy of leasing ships was replaced by the policy of building or purchasing them.van der Heyden (2001), p. 17 On 1 October 1684 Frederick William bought all ships that had been leased for 110,000 talers. Also in 1684, the East Frisian port of Emden replaced Pillau as the main Brandenburg-Prussian naval base.van der Heyden (2001), p. 35 From Pillau, part of the shipyard, the admiral's house and the wooden church of the employees was transferred to Emden. While Emden was not part of Brandenburg-Prussia, the elector owned a nearby castle, Greetsiel, and negotiated an agreement with the town to maintain a garrison and a port.

West African Gold Coast (Großfriedrichsburg)