Bourgeosie on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a

The bourgeoisie emerged as a historical and political phenomenon in the 11th century when the ''bourgs'' of Central and Western Europe developed into cities dedicated to commerce and crafts. This urban expansion was possible thanks to economic concentration due to the appearance of protective self-organisation into guilds. Guilds arose when individual businessmen (such as craftsmen, artisans and merchants) conflicted with their rent-seeking feudal

The bourgeoisie emerged as a historical and political phenomenon in the 11th century when the ''bourgs'' of Central and Western Europe developed into cities dedicated to commerce and crafts. This urban expansion was possible thanks to economic concentration due to the appearance of protective self-organisation into guilds. Guilds arose when individual businessmen (such as craftsmen, artisans and merchants) conflicted with their rent-seeking feudal

According to

According to

The critical analyses of the bourgeois mentality by the German intellectual

The critical analyses of the bourgeois mentality by the German intellectual  Bourgeois values are dependent on

Bourgeois values are dependent on

The term bourgeoisie has been used as a pejorative and a term of abuse since the 19th century, particularly by intellectuals and artists.

The term bourgeoisie has been used as a pejorative and a term of abuse since the 19th century, particularly by intellectuals and artists.

'' Buddenbrooks'' (1901), by

'' Buddenbrooks'' (1901), by  Yet, George F. Babbitt sublimates his desire for self-respect, and encourages his son to rebel against the conformity that results from bourgeois prosperity, by recommending that he be true to himself:

Yet, George F. Babbitt sublimates his desire for self-respect, and encourages his son to rebel against the conformity that results from bourgeois prosperity, by recommending that he be true to himself:

''The Middling Sorts: Explorations in the History of the American Middle Class''

Routledge. 2001. * Brooks, David

''Bobos In Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There''

Simon & Schuster. 2001. * Byrne, Frank J

''Becoming Bourgeois: Merchant Culture in the South, 1820–1865''

University Press of Kentucky. 2006. * Cousin, Bruno and Sébastien Chauvin (2021)

"Is there a global super-bourgeoisie?"

''Sociology Compass'', vol. 15, issue 6, pp. 1–15

online

*Hunt, Margaret R

''The Middling Sort: Commerce, Gender, and the Family in England, 1680–1780''

University of California Press. 1996. * Lockwood, David

''Cronies or Capitalists? The Russian Bourgeoisie and the Bourgeois Revolution from 1850 to 1917''

Cambridge Scholars Publishing. 2009. * Siegel, Jerrold

''Bohemian Paris: Culture, Politics, and the Boundaries of Bourgeois Life, 1830–1930''

The Johns Hopkins University Press. 1999. * Stern, Robert W

''Changing India: Bourgeois Revolution on the Subcontinent''

Cambridge University Press. 2nd edition, 2003.

– A Critique of Bourgeois Sovereignty {{Authority control Marxist terminology Sociology of culture Middle class Upper class Estates (social groups)

social class

A social class is a grouping of people into a set of hierarchical social categories, the most common being the upper, middle and lower classes. Membership in a social class can for example be dependent on education, wealth, occupation, inc ...

, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital

Financial capital (also simply known as capital or equity in finance, accounting and economics) is any economic resource measured in terms of money used by entrepreneurs and businesses to buy what they need to make their products or to provi ...

. They are sometimes divided into a petty

Petty may refer to:

People

* Bruce Petty (born 1929), Australian political satirist and cartoonist

* Bryce Petty (born 1991), American football player

* Dini Petty (born 1945), Canadian television and radio host

* Eric D. Petty (born 1954), Ameri ...

(), middle (), large (), upper (), and ancient () bourgeoisie and collectively designated as "the bourgeoisie".

The bourgeoisie in its original sense is intimately linked to the existence of cities, recognized as such by their urban charters (e.g., municipal charter

A city charter or town charter (generically, municipal charter) is a legal document ('' charter'') establishing a municipality such as a city or town. The concept developed in Europe during the Middle Ages.

Traditionally the granting of a charte ...

s, town privileges

Town privileges or borough rights were important features of European towns during most of the second millennium. The city law customary in Central Europe probably dates back to Italian models, which in turn were oriented towards the traditio ...

, German town law

The German town law (german: Deutsches Stadtrecht) or German municipal concerns (''Deutsches Städtewesen'') was a set of early town privileges based on the Magdeburg rights developed by Otto I. The Magdeburg Law became the inspiration for regiona ...

), so there was no bourgeoisie apart from the citizenry

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

of the cities. Rural peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasa ...

s came under a different legal system.

In Marxist philosophy, the bourgeoisie is the social class that came to own the means of production

The means of production is a term which describes land, labor and capital that can be used to produce products (such as goods or services); however, the term can also refer to anything that is used to produce products. It can also be used as a ...

during modern industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

and whose societal concerns are the value of property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

and the preservation of capital to ensure the perpetuation of their economic supremacy in society.

Etymology

The Modern French word ( or , ) derived from theOld French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intel ...

or ('town dweller'), which derived from ('market town

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village or city. In Britain, small rural ...

'), from the Old Frankish

Frankish ( reconstructed endonym: *), also known as Old Franconian or Old Frankish, was the West Germanic language spoken by the Franks from the 5th to 9th century.

After the Salian Franks settled in Roman Gaul, its speakers in Picardy ...

('town'); in other European languages, the etymologic derivations include the Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old Englis ...

, the Middle Dutch , the German , the Modern English '' burgess'', the Spanish , the Portuguese , and the Polish , which occasionally is synonymous with the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

.

In the 18th century, before the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

(1789–1799), in the French Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for " ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

, the masculine and feminine terms ''bourgeois'' and ''bourgeoise'' identified the relatively rich men and women who were members of the urban and rural Third Estate – the common people of the French realm, who violently deposed the absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constituti ...

of the Bourbon King Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

(r. 1774–1791), his clergy, and his aristocrats in the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

of 1789–1799. Hence, since the 19th century, the term "bourgeoisie" usually is politically and sociologically synonymous with the ruling upper class of a capitalist society. In English, the word "bourgeoisie", as a term referring to French history, refers to a social class oriented to economic materialism and hedonism

Hedonism refers to a family of theories, all of which have in common that pleasure plays a central role in them. ''Psychological'' or ''motivational hedonism'' claims that human behavior is determined by desires to increase pleasure and to decr ...

, and to upholding the political and economic interests of the capitalist ruling-class.

Historically, the medieval French word ''bourgeois'' denoted the inhabitants of the ''bourgs'' (walled market-towns), the craft

A craft or trade is a pastime or an occupation that requires particular skills and knowledge of skilled work. In a historical sense, particularly the Middle Ages and earlier, the term is usually applied to people occupied in small scale pr ...

smen, artisan

An artisan (from french: artisan, it, artigiano) is a skilled craft worker who makes or creates material objects partly or entirely by hand. These objects may be functional or strictly decorative, for example furniture, decorative art ...

s, merchant

A merchant is a person who trades in commodities produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Historically, a merchant is anyone who is involved in business or trade. Merchants have operated for as long as indust ...

s, and others, who constituted "the bourgeoisie". They were the socio-economic class between the peasants and the landlords, between the workers and the owners of the means of production

The means of production is a term which describes land, labor and capital that can be used to produce products (such as goods or services); however, the term can also refer to anything that is used to produce products. It can also be used as a ...

. As the economic manager

Management (or managing) is the administration of an organization, whether it is a business, a nonprofit organization, or a government body. It is the art and science of managing resources of the business.

Management includes the activitie ...

s of the (raw) materials, the goods, and the services, and thus the capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used fo ...

(money) produced by the feudal economy, the term "bourgeoisie" evolved to also denote the middle class – the businessmen and businesswomen who accumulated, administered, and controlled the capital that made possible the development of the bourgs into cities."Bourgeoisie", ''The Columbia Encyclopedia'', Fifth Edition. (1994) p. 0000.

Contemporarily, the terms "bourgeoisie" and "bourgeois" (noun) identify the ruling class in capitalist societies, as a social stratum; while "bourgeois" (adjective / noun modifier) describes the ''Weltanschauung'' ( worldview) of men and women whose way of thinking is socially and culturally determined by their economic materialism and philistinism, a social identity famously mocked in Molière

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (, ; 15 January 1622 (baptised) – 17 February 1673), known by his stage name Molière (, , ), was a French playwright, actor, and poet, widely regarded as one of the greatest writers in the French language and world ...

's comedy '' Le Bourgeois gentilhomme'' (1670), which satirizes buying the trappings of a noble-birth identity as the means of climbing the social ladder. The 18th century saw a partial rehabilitation of bourgeois values in genres such as the ''drame bourgeois'' (bourgeois drama) and " bourgeois tragedy".

In the late 20th century, the shortened term "bougie" or "boujee" (an intentional misspelling) became slang

Slang is vocabulary (words, phrases, and linguistic usages) of an informal register, common in spoken conversation but avoided in formal writing. It also sometimes refers to the language generally exclusive to the members of particular in-gr ...

, particularly among African-Americans. The term refers to a person of lower or middle class doing pretentious activities or virtue signalling as an affectation of the upper-class.

History

Origins and rise

The bourgeoisie emerged as a historical and political phenomenon in the 11th century when the ''bourgs'' of Central and Western Europe developed into cities dedicated to commerce and crafts. This urban expansion was possible thanks to economic concentration due to the appearance of protective self-organisation into guilds. Guilds arose when individual businessmen (such as craftsmen, artisans and merchants) conflicted with their rent-seeking feudal

The bourgeoisie emerged as a historical and political phenomenon in the 11th century when the ''bourgs'' of Central and Western Europe developed into cities dedicated to commerce and crafts. This urban expansion was possible thanks to economic concentration due to the appearance of protective self-organisation into guilds. Guilds arose when individual businessmen (such as craftsmen, artisans and merchants) conflicted with their rent-seeking feudal landlord

A landlord is the owner of a house, apartment, condominium, land, or real estate which is rented or leased to an individual or business, who is called a tenant (also a ''lessee'' or ''renter''). When a juristic person is in this position, t ...

s who demanded greater rent

Rent may refer to:

Economics

*Renting, an agreement where a payment is made for the temporary use of a good, service or property

*Economic rent, any payment in excess of the cost of production

*Rent-seeking, attempting to increase one's share of e ...

s than previously agreed.

In the event, by the end of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

(c. AD 1500), under régimes of the early national monarchies of Western Europe, the bourgeoisie acted in self-interest, and politically supported the king or queen against legal and financial disorder caused by the greed of the feudal lords. In the late-16th and early 17th centuries, the bourgeoisies of England and the Netherlands had become the financial – thus political – forces that deposed the feudal order; economic power

Economic power refers to the ability of countries, businesses or individuals to improve living standards. It increases their ability to make decisions on their own that benefit them. Scholars of international relations also refer to the economic p ...

had vanquished military power in the realm of politics.

From progress to reaction (Marxist view)

According to the Marxist view of history, during the 17th and 18th centuries, the bourgeoisie were the politically progressive social class who supported the principles ofconstitutional government

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princi ...

and of natural right, against the Law of Privilege

A privilege is a certain entitlement to immunity granted by the state or another authority to a restricted group, either by birth or on a conditional basis. Land-titles and taxi medallions are examples of transferable privilege – they can be ...

and the claims of rule by divine right that the nobles

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The character ...

and prelate

A prelate () is a high-ranking member of the Christian clergy who is an ordinary or who ranks in precedence with ordinaries. The word derives from the Latin , the past participle of , which means 'carry before', 'be set above or over' or 'pre ...

s had autonomously exercised during the feudal order.

The English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

(1642–1651), the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

(1775–1783), and French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

(1789–1799) were partly motivated by the desire of the bourgeoisie to rid themselves of the feudal and royal encroachments on their personal liberty, commercial prospects, and the ownership of property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

. In the 19th century, the bourgeoisie propounded liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostilit ...

, and gained political rights, religious rights, and civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties ma ...

for themselves and the lower social classes; thus the bourgeoisie was a progressive philosophic and political force in Western societies.

After the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

(1750–1850), by the mid-19th century the great expansion of the bourgeoisie social class caused its stratification – by business activity and by economic function – into the ''haute bourgeoisie'' (bankers and industrialists) and the '' petite bourgeoisie'' (tradesmen

A tradesman, tradeswoman, or tradesperson is a skilled worker that specializes in a particular trade (occupation or field of work). Tradesmen usually have work experience, on-the-job training, and often formal vocational education in contrast ...

and white-collar worker

A white-collar worker is a person who performs professional, desk, managerial, or administrative work. White-collar work may be performed in an office or other administrative setting. White-collar workers include job paths related to government, ...

s). Moreover, by the end of the 19th century, the capitalists (the original bourgeoisie) had ascended to the upper class, while the developments of technology and technical occupations allowed the rise of working-class men and women to the lower strata of the bourgeoisie; yet the social progress was incidental.

Denotations

Marxist theory

According to

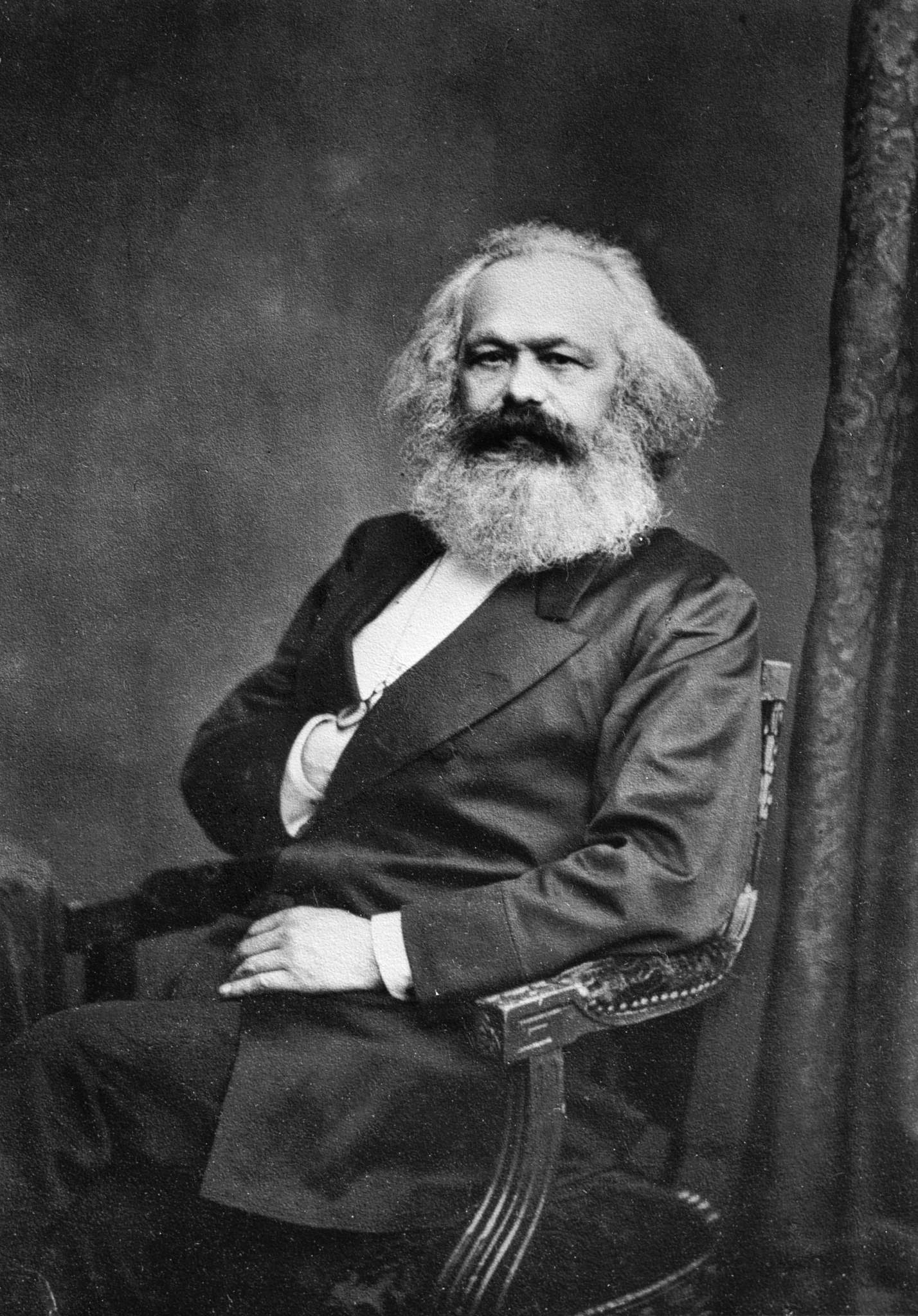

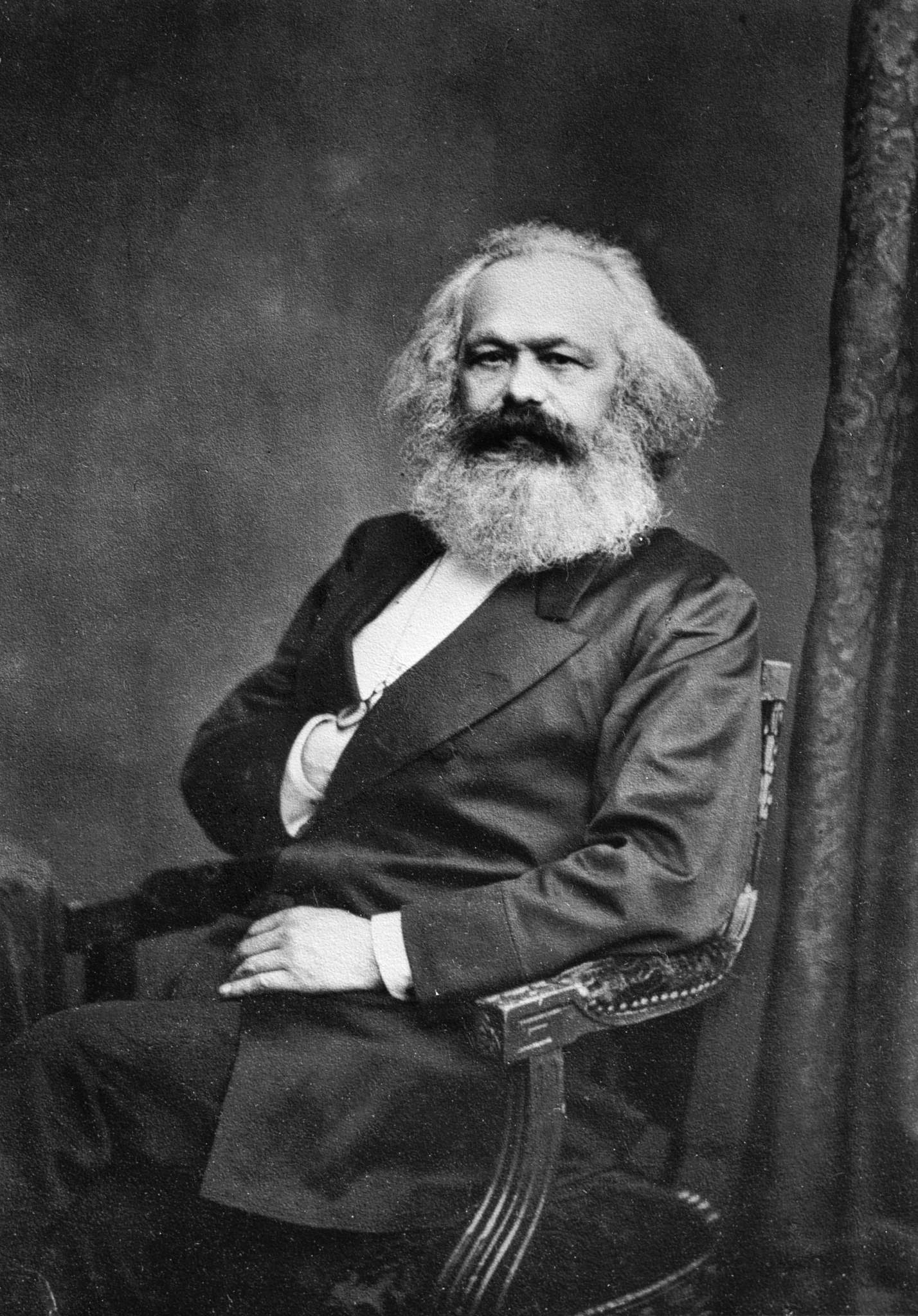

According to Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

, the bourgeois during the Middle Ages usually was a self-employed businessman – such as a merchant, banker, or entrepreneur – whose economic role in society was being the financial intermediary to the feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

landlord

A landlord is the owner of a house, apartment, condominium, land, or real estate which is rented or leased to an individual or business, who is called a tenant (also a ''lessee'' or ''renter''). When a juristic person is in this position, t ...

and the peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasa ...

who worked the fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form ...

, the land of the lord. Yet, by the 18th century, the time of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

(1750–1850) and of industrial capitalism, the bourgeoisie had become the economic ruling class who owned the means of production (capital and land), and who controlled the means of coercion (armed forces and legal system, police forces and prison system).

In such a society, the bourgeoisie's ownership of the means of production allowed them to employ and exploit the wage-earning working class (urban and rural), people whose only economic means is labour; and the bourgeois control of the means of coercion suppressed the sociopolitical challenges by the lower classes, and so preserved the economic status quo; workers remained workers, and employers remained employers.

In the 19th century, Marx distinguished two types of bourgeois capitalist: (i) the functional capitalists, who are business administrators of the means of production; and (ii) rentier capitalist

Rentier capitalism describes the economic practice of gaining large profits without contributing to society. And a rentier is someone who earns income from capital without working. This is generally done through ownership of assets that generate ...

s whose livelihoods derive either from the rent

Rent may refer to:

Economics

*Renting, an agreement where a payment is made for the temporary use of a good, service or property

*Economic rent, any payment in excess of the cost of production

*Rent-seeking, attempting to increase one's share of e ...

of property or from the interest

In finance and economics, interest is payment from a borrower or deposit-taking financial institution to a lender or depositor of an amount above repayment of the principal sum (that is, the amount borrowed), at a particular rate. It is distin ...

-income produced by finance capital, or both. In the course of economic relations, the working class and the bourgeoisie continually engage in class struggle

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The form ...

, where the capitalists exploit the workers, while the workers resist their economic exploitation, which occurs because the worker owns no means of production, and, to earn a living, seeks employment from the bourgeois capitalist; the worker produces goods and services that are property of the employer, who sells them for a price.

Besides describing the social class

A social class is a grouping of people into a set of hierarchical social categories, the most common being the upper, middle and lower classes. Membership in a social class can for example be dependent on education, wealth, occupation, inc ...

who owns the means of production

The means of production is a term which describes land, labor and capital that can be used to produce products (such as goods or services); however, the term can also refer to anything that is used to produce products. It can also be used as a ...

, the Marxist use of the term "bourgeois" also describes the consumerist

''Consumerist'' (also known as ''The Consumerist'') was a non-profit consumer affairs website owned by Consumer Media LLC, a subsidiary of ''Consumer Reports'', with content created by a team of full-time reporters and editors. The site's foc ...

style of life derived from the ownership of capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used fo ...

and real property

In English common law, real property, real estate, immovable property or, solely in the US and Canada, realty, is land which is the property of some person and all structures (also called improvements or fixtures) integrated with or aff ...

. Marx acknowledged the bourgeois industriousness that created wealth, but criticised the moral hypocrisy of the bourgeoisie when they ignored the alleged origins of their wealth: the exploitation of the proletariat, the urban and rural workers. Further sense denotations of "bourgeois" describe ideological concepts such as "bourgeois freedom", which is thought to be opposed to substantive forms of freedom; "bourgeois independence"; "bourgeois personal individuality"; the "bourgeois family"; et cetera, all derived from owning capital and property (see '' The Communist Manifesto'', 1848).

France and French-speaking countries

In English, the term ''bourgeoisie'' is often used to denote the middle classes. In fact, the French term encompasses both the upper and middle economic classes, a misunderstanding which has occurred in other languages as well. The bourgeoisie in France and many French-speaking countries consists of five evolving social layers: ''petite bourgeoisie'', ''moyenne bourgeoisie'', ''grande bourgeoisie'', ''haute bourgeoisie'' and ''ancienne bourgeoisie''.''Petite bourgeoisie''

The ''petite bourgeoisie'' is the equivalent of the modern-day middle class, or refers to "a social class between the middle class and the lower class: the lower middle class".''Moyenne bourgeoisie''

The ''moyenne bourgeoisie'' or middle bourgeoisie contains people who have solid incomes and assets, but not the aura of those who have become established at a higher level. They tend to belong to a family that has been bourgeois for three or more generations. Some members of this class may have relatives from similar backgrounds, or may even have aristocratic connections. The ''moyenne bourgeoisie'' is the equivalent of the British and American upper-middle classes.''Grande bourgeoisie''

The ''grande bourgeoisie'' are families that have been bourgeois since the 19th century, or for at least four or five generations. Members of these families tend to marry with the aristocracy or make other advantageous marriages. This bourgeois family has acquired an established historical and cultural heritage over the decades. The names of these families are generally known in the city where they reside, and their ancestors have often contributed to the region's history. These families are respected and revered. They belong to the upper class, roughly equivalent to the British gentry. In the French-speaking countries, they are sometimes .''Haute bourgeoisie''

The ''haute bourgeoisie'' is a social rank in the bourgeoisie that can only be acquired through time. In France, it is composed of bourgeois families that have existed since the French Revolution. They hold only honourable professions and have experienced many illustrious marriages in their family's history. They have rich cultural and historical heritages, and their financial means are more than secure. These families attempt to be perceived as nobles, taking on such affectations, for example, as avoiding certain marriages or occupations. They differ from nobility only in that because of circumstances, the lack of opportunity, and/or political regime, they have not been ennobled. These people nevertheless live lavishly, enjoying the company of the great artists of the time. In France, the families of the ''haute bourgeoisie'' are also referred to as ''les 200 familles'', a term coined in the first half of the 20th century. Michel Pinçon and Monique Pinçon-Charlot studied the lifestyle of the French bourgeoisie, and how they boldly guard their world from the ''nouveau riche'', or newly rich. In the French language, the term ''bourgeoisie'' almost designates a caste by itself, even though social mobility into this socio-economic group is possible. Nevertheless, the ''bourgeoisie'' is differentiated from ''la classe moyenne'', or the middle class, which consists mostly of white-collar employees, by holding a profession referred to as a ''profession libérale'', which ''la classe moyenne'', in its definition does not hold. Yet, in English the definition of a white-collar job encompasses the ''profession libérale''.''Ancienne bourgeoisie''

The ''ancienne bourgeoisie'' is a relatively recent sociological term coined by René Rémond and an additional subcategory in the French language to the "bourgeoisie" caste. In Rémond's preface of "L’ancienne bourgeoisie en France : émergence et permanence d'un groupe social du xvie siècle au xxe siècle“ published by Xavier de Montclos in 2013, he defines ''l’ancienne bourgeoisie'' as follows: "An intermediary social group between the aristocracy and what we would call the middle classes ("les classes moyennes" in French, which does not have the same sociological implications as in English) and which was established between 15th and 16th centuries...These families are for the most part provincial dynasties whose social ascension was accomplished in their region of origin and to which they generally remain attached to, and in which their descendants are still present...These families are deeply rooted in the "Ancien Régime"...They have insured the transmission of their material legacy, as well their convictions and set of values for over 400 and 500 years". Xavier de Montclos goes further by saying that these families acquired their status during the "Ancien Régime", and that they belonged to the town's elite and the upper-crust of the "bourgeoisie" caste. They usually acquired high and important administrative and judicial functions, and distinguished themselves through their success, particularly in business and industry. It was through this distinction that some of these families were able to acquire titles typically associated with the nobility, a caste from which they remained nonetheless excluded.Nazism

Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

rejected the Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

concept of internationalist class struggle

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The form ...

, but supported the "class struggle between nations", and sought to resolve internal class struggle in the nation while it identified Germany as a proletariat nation fighting against plutocratic

A plutocracy () or plutarchy is a society that is ruled or controlled by people of great wealth or income. The first known use of the term in English dates from 1631. Unlike most political systems, plutocracy is not rooted in any establish ...

nations.

The Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

had many working-class supporters and members, and a strong appeal to the middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. C ...

. The financial collapse of the white collar middle-class of the 1920s figures much in their strong support of Nazism.Burleigh, Michael. ''The Third Reich: A New History'', New York, USA: Hill and Wang, 2000. p. 77. In the poor country that was the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

of the early 1930s, the Nazi Party realised their social policies with food and shelter for the unemployed and the homeless—who were later recruited into the Brownshirt ''Sturmabteilung

The (; SA; literally "Storm Detachment") was the original paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party. It played a significant role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s. Its primary purposes were providing protection for Nazi ralli ...

'' (SA – Storm Detachments).

Hitler was impressed by the populist antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

and the anti-liberal bourgeois agitation of Karl Lueger, who as the mayor of Vienna during Hitler's time in the city, used a rabble-rousing style of oratory that appealed to the wider masses. When asked whether he supported the "bourgeois right-wing", Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

claimed that Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

was not exclusively for any class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differently ...

, and he also indicated that it favoured neither the left nor the right

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical ...

, but preserved "pure" elements from both "camps", stating: "From the camp of bourgeois tradition, it takes national resolve, and from the materialism of the Marxist dogma, living, creative Socialism".Adolf Hitler, Max Domarus. ''The Essential Hitler: Speeches and Commentary''. pp. 171, 172–173.

Hitler distrusted capitalism for being unreliable due to its egotism

Egotism is defined as the drive to maintain and enhance favorable views of oneself and generally features an inflated opinion of one's personal features and importance distinguished by a person's amplified vision of one's self and self-importan ...

, and he preferred a state-directed economy that is subordinated to the interests of the ''Volk

The German noun ''Volk'' () translates to people,

both uncountable in the sense of ''people'' as in a crowd, and countable (plural ''Völker'') in the sense of '' a people'' as in an ethnic group or nation (compare the English term '' folk ...

''.

Hitler told a party leader in 1934, "The economic system of our day is the creation of the Jews". Hitler said to Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

that capitalism had "run its course". Hitler also said that the business bourgeoisie "know nothing except their profit. 'Fatherland' is only a word for them." Hitler was personally disgusted with the ruling bourgeois elites of Germany during the period of the Weimar Republic, whom he referred to as "cowardly shits".

Modern history in Italy

Because of their ascribed cultural excellence as a social class, the Italian fascist régime (1922–45) of Prime MinisterBenito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

regarded the bourgeoisie as an obstacle to Modernism

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

.Bellassai, Sandro (2005) "The Masculine Mystique: Anti-Modernism and Virility in Fascist Italy", ''Journal of Modern Italian Studies'', 3, pp. 314–335. Nonetheless, the Fascist State ideologically exploited the Italian bourgeoisie and their materialistic, middle-class spirit, for the more efficient cultural manipulation of the upper (aristocratic) and the lower (working) classes of Italy.

In 1938, Prime Minister Mussolini gave a speech wherein he established a clear ideological distinction between capitalism (the social function of the bourgeoisie) and the bourgeoisie (as a social class), whom he dehumanised by reducing them into high-level abstractions: a moral category and a state of mind. Culturally and philosophically, Mussolini isolated the bourgeoisie from Italian society by portraying them as social parasites upon the fascist Italian state and "The People"; as a social class who drained the human potential of Italian society, in general, and of the working class, in particular; as exploiters who victimised the Italian nation with an approach to life characterised by hedonism

Hedonism refers to a family of theories, all of which have in common that pleasure plays a central role in them. ''Psychological'' or ''motivational hedonism'' claims that human behavior is determined by desires to increase pleasure and to decr ...

and materialism. Nevertheless, despite the slogan ''The Fascist Man Disdains the ″Comfortable″ Life'', which epitomised the anti-bourgeois principle, in its final years of power, for mutual benefit and profit, the Mussolini fascist régime transcended ideology to merge the political and financial interests of Prime Minister Benito Mussolini with the political and financial interests of the bourgeoisie, the Catholic social circles who constituted the ruling class

In sociology, the ruling class of a society is the social class who set and decide the political and economic agenda of society. In Marxist philosophy, the ruling class are the capitalist social class who own the means of production and by ex ...

of Italy.

Philosophically, as a materialist

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materiali ...

creature, the bourgeois man was stereotyped as irreligious; thus, to establish an existential distinction between the supernatural faith of the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and the materialist faith of temporal religion; in ''The Autarchy of Culture: Intellectuals and Fascism in the 1930s'', the priest Giuseppe Marino said that:

Culturally, the bourgeois man may be considered effeminate, infantile, or acting in a pretentious manner; describing his philistinism in ''Bonifica antiborghese'' (1939), Roberto Paravese comments on the:

The economic security, financial freedom, and social mobility of the bourgeoisie threatened the philosophic integrity of Italian Fascism, the ideological monolith that was the régime of Prime Minister Benito Mussolini. Any assumption of legitimate political power (government and rule) by the bourgeoisie represented a fascist loss of totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

state power for social control through political unity—one people, one nation, and one leader. Sociologically, to the fascist man, to become a bourgeois was a character flaw inherent to the masculine mystique; therefore, the ideology of Italian fascism scornfully defined the bourgeois man as "spiritually castrated".

Bourgeois culture

Cultural hegemony

Karl Marx said that the culture of a society is dominated by the mores of the ruling-class, wherein their superimposed value system is abided by each social class (the upper, the middle, the lower) regardless of the socio-economic results it yields to them. In that sense, contemporary societies are bourgeois to the degree that they practice the mores of the small-business "shop culture" of early modern France; which the writer Émile Zola (1840–1902) naturalistically presented, analysed, and ridiculed in the twenty-two-novel series (1871–1893) about ''Les Rougon-Macquart

''Les Rougon-Macquart'' is the collective title given to a cycle of twenty novels by French writer Émile Zola. Subtitled ''Histoire naturelle et sociale d'une famille sous le Second Empire'' (''Natural and social history of a family under the S ...

'' family; the thematic thrust is the necessity for social progress, by subordinating the economic sphere to the social sphere of life.

Conspicuous consumption

The critical analyses of the bourgeois mentality by the German intellectual

The critical analyses of the bourgeois mentality by the German intellectual Walter Benjamin

Walter Bendix Schönflies Benjamin (; ; 15 July 1892 – 26 September 1940) was a German Jewish philosopher, cultural critic and essayist.

An eclectic thinker, combining elements of German idealism, Romanticism, Western Marxism, and Jewish ...

(1892–1940) indicated that the shop culture of the petite bourgeoisie established the sitting room as the centre of personal and family life; as such, the English bourgeois culture is, he alleges, a sitting-room culture of prestige through conspicuous consumption. The material culture

Material culture is the aspect of social reality grounded in the objects and architecture that surround people. It includes the usage, consumption, creation, and trade of objects as well as the behaviors, norms, and rituals that the objects crea ...

of the bourgeoisie concentrated on mass-produced luxury goods of high quality; between generations, the only variance was the materials with which the goods were manufactured.

In the early part of the 19th century, the bourgeois house contained a home that first was stocked and decorated with hand-painted porcelain

Porcelain () is a ceramic material made by heating substances, generally including materials such as kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between . The strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to other types of pottery, arises main ...

, machine-printed cotton fabrics, machine-printed wallpaper

Wallpaper is a material used in interior decoration to decorate the interior walls of domestic and public buildings. It is usually sold in rolls and is applied onto a wall using wallpaper paste. Wallpapers can come plain as "lining paper" (so ...

, and Sheffield steel ( crucible and stainless). The utility

As a topic of economics, utility is used to model worth or value. Its usage has evolved significantly over time. The term was introduced initially as a measure of pleasure or happiness as part of the theory of utilitarianism by moral philosophe ...

of these things was inherent in their practical functions. By the latter part of the 19th century, the bourgeois house contained a home that had been remodelled by conspicuous consumption. Here, Benjamin argues, the goods were bought to display wealth ( discretionary income), rather than for their practical utility. The bourgeoisie had transposed the wares of the shop window to the sitting room, where the clutter of display signalled bourgeois success.Walter Benjamin

Walter Bendix Schönflies Benjamin (; ; 15 July 1892 – 26 September 1940) was a German Jewish philosopher, cultural critic and essayist.

An eclectic thinker, combining elements of German idealism, Romanticism, Western Marxism, and Jewish ...

, ''The Halles Project''. (See: '' Culture and Anarchy'', 1869.)

Two spatial constructs manifest the bourgeois mentality: (i) the shop-window display, and (ii) the sitting room. In English, the term "sitting-room culture" is synonymous for "bourgeois mentality", a "philistine

The Philistines ( he, פְּלִשְׁתִּים, Pəlīštīm; Koine Greek ( LXX): Φυλιστιείμ, romanized: ''Phulistieím'') were an ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan from the 12th century BC until 604 BC, when ...

" cultural perspective from the Victorian Era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwa ...

(1837–1901), especially characterised by the repression of emotion and of sexual desire; and by the construction of a regulated social-space where "propriety

Etiquette () is the set of norms of personal behaviour in polite society, usually occurring in the form of an ethical code of the expected and accepted social behaviours that accord with the conventions and norms observed and practised by a ...

" is the key personality trait desired in men and women.

Nonetheless, from such a psychologically constricted worldview, regarding the rearing of children, contemporary sociologists claim to have identified "progressive" middle-class values, such as respect for non-conformity, self-direction, autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy, from , ''autonomos'', from αὐτο- ''auto-'' "self" and νόμος ''nomos'', "law", hence when combined understood to mean "one who gives oneself one' ...

, gender equality

Gender equality, also known as sexual equality or equality of the sexes, is the state of equal ease of access to resources and opportunities regardless of gender, including economic participation and decision-making; and the state of valuing d ...

and the encouragement of innovation; as in the Victorian Era, the transposition to the US of the bourgeois system of social values has been identified as a requisite for employment success in the professions.  Bourgeois values are dependent on

Bourgeois values are dependent on rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy' ...

, which began with the economic sphere and moves into every sphere of life which is formulated by Max Weber. The beginning of rationalism is commonly called the Age of Reason

The Age of reason, or the Enlightenment, was an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th to 19th centuries.

Age of reason or Age of Reason may also refer to:

* Age of reason (canon law), ...

. Much like the Marxist critics of that period, Weber was concerned with the growing ability of large corporations and nations to increase their power and reach throughout the world.

Satire and criticism in art

Beyond theintellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator o ...

realms of political economy

Political economy is the study of how economic systems (e.g. markets and national economies) and political systems (e.g. law, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied phenomena within the discipline are systems such as labour ...

, history, and political science

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thought, political behavior, and associated constitutions and ...

that discuss, describe, and analyse the ''bourgeoisie'' as a social class, the colloquial usage of the sociological terms ''bourgeois'' and ''bourgeoise'' describe the social stereotype

In social psychology, a stereotype is a generalized belief about a particular category of people. It is an expectation that people might have about every person of a particular group. The type of expectation can vary; it can be, for exampl ...

s of the old money and of the '' nouveau riche'', who is a politically timid conformist satisfied with a wealthy, consumerist

''Consumerist'' (also known as ''The Consumerist'') was a non-profit consumer affairs website owned by Consumer Media LLC, a subsidiary of ''Consumer Reports'', with content created by a team of full-time reporters and editors. The site's foc ...

style of life characterised by conspicuous consumption and the continual striving for prestige. This being the case, the cultures of the world describe the philistinism of the middle-class personality, produced by the excessively rich life of the bourgeoisie, is examined and analysed in comedic and dramatic plays, novels, and films. (See: Authenticity.) The term bourgeoisie has been used as a pejorative and a term of abuse since the 19th century, particularly by intellectuals and artists.

The term bourgeoisie has been used as a pejorative and a term of abuse since the 19th century, particularly by intellectuals and artists.

Theatre

'' Le Bourgeois gentilhomme'' (The Would-be Gentleman, 1670) byMolière

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (, ; 15 January 1622 (baptised) – 17 February 1673), known by his stage name Molière (, , ), was a French playwright, actor, and poet, widely regarded as one of the greatest writers in the French language and world ...

(Jean-Baptiste Poquelin), is a comedy-ballet that satirises Monsieur Jourdain, the prototypical nouveau riche man who buys his way up the social-class scale, to realise his aspirations of becoming a gentleman, to which end he studies dancing, fencing, and philosophy, the trappings and accomplishments of a gentleman, to be able to pose as a man of noble birth, someone who, in 17th-century France, was a man to the manor born; Jourdain's self-transformation also requires managing the private life of his daughter, so that her marriage can also assist his social ascent.

Literature

'' Buddenbrooks'' (1901), by

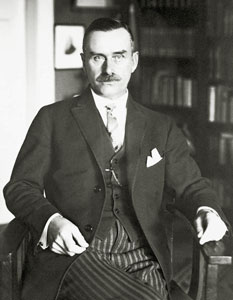

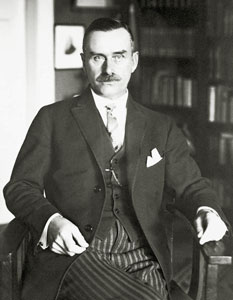

'' Buddenbrooks'' (1901), by Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novell ...

(1875–1955), chronicles the moral

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. ...

, intellectual, and physical

Physical may refer to:

* Physical examination, a regular overall check-up with a doctor

* ''Physical'' (Olivia Newton-John album), 1981

** "Physical" (Olivia Newton-John song)

* ''Physical'' (Gabe Gurnsey album)

* "Physical" (Alcazar song) (2004)

* ...

decay of a rich family through its declines, material and spiritual, in the course of four generations, beginning with the patriarch

The highest-ranking bishops in Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Catholic Church (above major archbishop and primate), the Hussite Church, Church of the East, and some Independent Catholic Churches are termed patriarchs (and in c ...

Johann Buddenbrook Sr. and his son, Johann Buddenbrook Jr., who are typically successful German businessmen; each is a reasonable man of solid character.

Yet, in the children of Buddenbrook Jr., the materially comfortable style of life provided by the dedication to solid, middle-class values elicits decadence: The fickle daughter, Toni, lacks and does not seek a purpose in life; son Christian is honestly decadent, and lives the life of a ne'er-do-well; and the businessman son, Thomas, who assumes command of the Buddenbrook family fortune, occasionally falters from middle-class solidity by being interested in art and philosophy, the impractical life of the mind, which, to the bourgeoisie, is the epitome of social, moral, and material decadence.

'' Babbitt'' (1922), by Sinclair Lewis (1885–1951), satirizes the American bourgeois George Follansbee Babbitt, a middle-aged realtor

A real estate agent or real estate broker is a person who represents sellers or buyers of real estate or real property. While a broker may work independently, an agent usually works under a licensed broker to represent clients. Brokers and agen ...

, booster, and joiner in the Midwestern city of Zenith, who – despite being unimaginative, self-important, and hopelessly conformist and middle-class – is aware that there must be more to life than money and the consumption of the best things that money can buy. Nevertheless, he fears being excluded from the mainstream of society more than he does living for himself, by being true to himself – his heart-felt flirtations with independence (dabbling in liberal politics and a love affair with a pretty widow) come to naught because he is existentially afraid.Films

Many of the satirical films by the Spanish film director Luis Buñuel (1900–1983) examine the mental and moral effects of the bourgeois mentality, its culture, and the stylish way of life it provides for its practitioners. * '' L'Âge d'or'' (''The Golden Age'', 1930) illustrates the madness and self-destructive hypocrisy of bourgeois society. * '' Belle de Jour'' (''Beauty of the day'', 1967) tells the story of a bourgeois wife who is bored with her marriage and decides to prostitute herself. * ''Le charme discret de la bourgeoisie

''The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie'' (french: Le Charme discret de la bourgeoisie) is a 1972 surrealist film directed by Luis Buñuel from a screenplay co-written with Jean-Claude Carrière. The narrative concerns a group of bourgeois people ...

'' (''The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie'', 1972) explores the timidity instilled by middle-class values.

* '' Cet obscur objet du désir'' (''That Obscure Object of Desire'', 1977) illuminates the practical self-deceptions required for buying love as marriage.

See also

References

Works cited

* * * * * *Further reading

* Bledstein, Burton J. and Johnston, Robert D. (eds.''The Middling Sorts: Explorations in the History of the American Middle Class''

Routledge. 2001. * Brooks, David

''Bobos In Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There''

Simon & Schuster. 2001. * Byrne, Frank J

''Becoming Bourgeois: Merchant Culture in the South, 1820–1865''

University Press of Kentucky. 2006. * Cousin, Bruno and Sébastien Chauvin (2021)

"Is there a global super-bourgeoisie?"

''Sociology Compass'', vol. 15, issue 6, pp. 1–15

online

*Hunt, Margaret R

''The Middling Sort: Commerce, Gender, and the Family in England, 1680–1780''

University of California Press. 1996. * Lockwood, David

''Cronies or Capitalists? The Russian Bourgeoisie and the Bourgeois Revolution from 1850 to 1917''

Cambridge Scholars Publishing. 2009. * Siegel, Jerrold

''Bohemian Paris: Culture, Politics, and the Boundaries of Bourgeois Life, 1830–1930''

The Johns Hopkins University Press. 1999. * Stern, Robert W

''Changing India: Bourgeois Revolution on the Subcontinent''

Cambridge University Press. 2nd edition, 2003.

External links

– A Critique of Bourgeois Sovereignty {{Authority control Marxist terminology Sociology of culture Middle class Upper class Estates (social groups)