Bolesław Prus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aleksander Głowacki (20 August 1847 – 19 May 1912), better known by his pen name Bolesław Prus (), was a Polish novelist, a leading figure in the history of

Aleksander Głowacki was born 20 August 1847 in

Aleksander Głowacki was born 20 August 1847 in  Five months later, in early February 1864, Prus was arrested and imprisoned at

Five months later, in early February 1864, Prus was arrested and imprisoned at

As a newspaper columnist, Prus commented on the achievements of scholars and scientists such as John Stuart Mill,

As a newspaper columnist, Prus commented on the achievements of scholars and scientists such as John Stuart Mill,  Though Prus was a gifted writer, initially best known as a humorist, he early on thought little of his journalistic and literary work. Hence at the inception of his career in 1872, at the age of 25, he adopted for his newspaper columns and fiction the pen name "Prus" ("'' Prus I''" was his family

Though Prus was a gifted writer, initially best known as a humorist, he early on thought little of his journalistic and literary work. Hence at the inception of his career in 1872, at the age of 25, he adopted for his newspaper columns and fiction the pen name "Prus" ("'' Prus I''" was his family

In time, Prus adopted the French Positivist critic

In time, Prus adopted the French Positivist critic

Over the years, Prus lent his support to many charitable and social causes, but there was one event he came to rue for the broad criticism it brought him: his participation in welcoming Russia's

Over the years, Prus lent his support to many charitable and social causes, but there was one event he came to rue for the broad criticism it brought him: his participation in welcoming Russia's  In 1908, Prus serialized, in the Warsaw ''Tygodnik Ilustrowany'' (Illustrated Weekly), his novel ''Dzieci'' (Children), depicting the young revolutionaries, terrorists and anarchists of the day — an uncharacteristically humorless work. Three years later a final novel, ''Przemiany'' (Changes), was to have been, like '' The Doll'', a panorama of society and its vital concerns. However, in 1911 and 1912, the novel had barely begun serialization in the ''Illustrated Weekly'' when its composition was cut short by Prus's death.

Neither of the two late novels, ''Children'' or ''Changes'', is generally regarded as part of the essential Prus canon, and

In 1908, Prus serialized, in the Warsaw ''Tygodnik Ilustrowany'' (Illustrated Weekly), his novel ''Dzieci'' (Children), depicting the young revolutionaries, terrorists and anarchists of the day — an uncharacteristically humorless work. Three years later a final novel, ''Przemiany'' (Changes), was to have been, like '' The Doll'', a panorama of society and its vital concerns. However, in 1911 and 1912, the novel had barely begun serialization in the ''Illustrated Weekly'' when its composition was cut short by Prus's death.

Neither of the two late novels, ''Children'' or ''Changes'', is generally regarded as part of the essential Prus canon, and

On 3 December 1961, nearly half a century after Prus's death, a museum devoted to him was opened in the 18th-century Małachowski Palace at

On 3 December 1961, nearly half a century after Prus's death, a museum devoted to him was opened in the 18th-century Małachowski Palace at

In Prus's lifetime and since, his contributions to Polish literature and culture have been memorialized without regard to the nature of the political system prevailing at the time. His 50th birthday, in 1897, was marked by special newspaper issues celebrating his 25 years as a journalist and fiction writer, and a portrait of him was commissioned from artist Antoni Kamieński.

The town where Prus was born,

In Prus's lifetime and since, his contributions to Polish literature and culture have been memorialized without regard to the nature of the political system prevailing at the time. His 50th birthday, in 1897, was marked by special newspaper issues celebrating his 25 years as a journalist and fiction writer, and a portrait of him was commissioned from artist Antoni Kamieński.

The town where Prus was born,

* "Travel Notes (Wieliczka)" [''"Kartki z podróży (Wieliczka),"'' 1878—Prus's impressions of the

* 1968: ''Lalka ( The Doll (1968 film), The Doll''), adapted from the novel '' The Doll'', directed by

* 1977: '' :pl:Lalka (serial telewizyjny), Lalka'' (

Works by Bolesław Prus

at

Bolesław Prus

in the Virtual Library of Polish Literature

Bolesław Prus

collected works (Polish) * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Prus, Boleslaw 1847 births 1912 deaths People from Hrubieszów People from Lublin Governorate January Uprising participants University of Warsaw alumni 19th-century Polish male writers 20th-century Polish male writers Polish journalists Polish essayists Male essayists 19th-century essayists 20th-century essayists Polish literary critics Polish male short story writers Polish short story writers 19th-century short story writers 20th-century short story writers Polish male novelists 19th-century Polish novelists 20th-century Polish novelists Polish historical novelists Writers of historical fiction set in antiquity Burials at Powązki Cemetery 19th-century Polish philosophers 20th-century Polish philosophers Polish positivism

Polish literature

Polish literature is the literary tradition of Poland. Most Polish literature has been written in the Polish language, though other languages used in Poland over the centuries have also contributed to Polish literary traditions, including Latin, ...

and philosophy, as well as a distinctive voice in world literature

World literature is used to refer to the total of the world's national literature and the circulation of works into the wider world beyond their country of origin. In the past, it primarily referred to the masterpieces of Western European lit ...

.

As a 15-year-old, Aleksander Głowacki joined the Polish 1863 Uprising against Imperial Russia. Shortly after his 16th birthday, he suffered severe battle injuries. Five months later, he was imprisoned for his part in the Uprising. These early experiences may have precipitated the panic disorder

Panic disorder is a mental and behavioral disorder, specifically an anxiety disorder characterized by reoccurring unexpected panic attacks. Panic attacks are sudden periods of intense fear that may include palpitations, sweating, shaking, short ...

and agoraphobia that dogged him through life, and shaped his opposition to attempting to regain Poland's independence by force of arms.

In 1872, at the age of 25, in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

, he settled into a 40-year journalistic career that highlighted science, technology, education, and economic and cultural development. These societal enterprises were essential to the endurance of a people who had in the 18th century been partitioned out of political existence by Russia, Prussia and Austria. Głowacki took his pen name "''Prus''" from the appellation of his family's coat-of-arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in its w ...

.

As a sideline, he wrote short stories. Succeeding with these, he went on to employ a larger canvas; over the decade between 1884 and 1895, he completed four major novels: '' The Outpost'', '' The Doll'', '' The New Woman'' and ''Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

''. ''The Doll'' depicts the romantic infatuation of a man of action who is frustrated by his country's backwardness. ''Pharaoh'', Prus's only historical novel, is a study of political power and of the fates of nations, set in ancient Egypt at the fall of the 20th Dynasty

The Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XX, alternatively 20th Dynasty or Dynasty 20) is the third and last dynasty of the Ancient Egyptian New Kingdom period, lasting from 1189 BC to 1077 BC. The 19th and 20th Dynasties furthermore toget ...

and New Kingdom.

Life

Early years

Aleksander Głowacki was born 20 August 1847 in

Aleksander Głowacki was born 20 August 1847 in Hrubieszów

Hrubieszów (; uk, Грубешів, Hrubeshiv; yi, הרוביעשאָוו, Hrubyeshov) is a town in southeastern Poland, with a population of around 18,212 (2016). It is the capital of Hrubieszów County within the Lublin Voivodeship.

Through ...

, now in southeastern Poland, very near the present-day border with Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

. The town was then in the Russian-controlled sector of partitioned Poland, known as the "Congress Kingdom

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

". Aleksander was the younger son of Antoni Głowacki, an estate steward at the village of Żabcze, in Hrubieszów County

__NOTOC__

Hrubieszów County ( pl, powiat hrubieszowski) is a unit of territorial administration and local government (powiat) in Lublin Voivodeship, eastern Poland, on the border with Ukraine. It was established on January 1, 1999, as a result of ...

, and Apolonia Głowacka ( née Trembińska).

In 1850, when the future ''Bolesław Prus'' was three years old, his mother died; the child was placed in the care of his maternal grandmother, Marcjanna Trembińska of Puławy

Puławy (, also written Pulawy) is a city in eastern Poland, in Lesser Poland's Lublin Voivodeship, at the confluence of the Vistula and Kurówka Rivers. Puławy is the capital of Puławy County. The city's 2019 population was estimated at 47,4 ...

, and, four years later, in the care of his aunt, Domicela Olszewska of Lublin. In 1856 Prus was orphan

An orphan (from the el, ορφανός, orphanós) is a child whose parents have died.

In common usage, only a child who has lost both parents due to death is called an orphan. When referring to animals, only the mother's condition is usuall ...

ed by his father's death and, aged 9, began attending a Lublin primary school whose principal, Józef Skłodowski, grandfather of the future double Nobel laureate Maria Skłodowska-Curie, administered canings (a customary mode of disciplining) to wayward pupils, including the spirited Aleksander.

In 1862, Prus's brother, Leon, a teacher thirteen years his senior, took him to Siedlce

Siedlce [] ( yi, שעדליץ ) is a city in eastern Poland with 77,354 inhabitants (). Situated in the Masovian Voivodeship (since 1999), previously the city was the capital of a separate Siedlce Voivodeship (1975–1998). The city is situated b ...

, then to Kielce.

Soon after the outbreak of the Polish January 1863 Uprising against Imperial Russia, 15-year-old Prus ran away from school to join the insurgents.Pieścikowski, Edward, ''Bolesław Prus'', p. 147. He may have been influenced by his brother Leon, one of the Uprising's leaders. Leon, during a June 1863 mission to Wilno (now Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urb ...

) in Lithuania for the Polish insurgent government, developed a debilitating mental illness that would end only with his death in 1907.

On 1 September 1863, twelve days after his sixteenth birthday, Prus took part in a battle against Russian forces at a village called Białka, four kilometers south of Siedlce

Siedlce [] ( yi, שעדליץ ) is a city in eastern Poland with 77,354 inhabitants (). Situated in the Masovian Voivodeship (since 1999), previously the city was the capital of a separate Siedlce Voivodeship (1975–1998). The city is situated b ...

. He suffered contusion

A bruise, also known as a contusion, is a type of hematoma of tissue, the most common cause being capillaries damaged by trauma, causing localized bleeding that extravasates into the surrounding interstitial tissues. Most bruises occur clos ...

s to the neck and gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). Th ...

injuries to his eyes, and was captured unconscious on the battlefield and taken to hospital in Siedlce. This experience may have caused his subsequent lifelong agoraphobia.

Five months later, in early February 1864, Prus was arrested and imprisoned at

Five months later, in early February 1864, Prus was arrested and imprisoned at Lublin Castle

The Lublin Castle ( pl, Zamek Lubelski) is a medieval castle in Lublin, Poland, adjacent to the Old Town district and close to the city center. It is one of the oldest preserved royal residencies in Poland, initially established by High Duke Casimi ...

for his role in the Uprising. In early April a military court sentenced him to forfeiture of his nobleman's status and resettlement on imperial lands. On 30 April, however, the Lublin District military head credited Prus's time spent under arrest and, on account of the 16-year-old's youth, decided to place him in the custody of his uncle Klemens Olszewski. On 7 May, Prus was released and entered the household of Katarzyna Trembińska, a relative and the mother of his future wife, Oktawia Trembińska.

Prus enrolled at a Lublin '' gymnasium'' ( secondary school), the still functioning prestigious Stanisław Staszic School, founded in 1586. Graduating on 30 June 1866, at nineteen he matriculated in the Warsaw University

The University of Warsaw ( pl, Uniwersytet Warszawski, la, Universitas Varsoviensis) is a public university in Warsaw, Poland. Established in 1816, it is the largest institution of higher learning in the country offering 37 different fields of ...

Department of Mathematics and Physics. In 1868, poverty forced him to break off his university studies.

In 1869, he enrolled in the Forestry Department at the newly opened Agriculture and Forestry Institute in Puławy

Puławy (, also written Pulawy) is a city in eastern Poland, in Lesser Poland's Lublin Voivodeship, at the confluence of the Vistula and Kurówka Rivers. Puławy is the capital of Puławy County. The city's 2019 population was estimated at 47,4 ...

, a historic town where he had spent some of his childhood and which, 15 years later, was the setting for his striking 1884 micro-story, " Mold of the Earth", comparing human history

Human history, also called world history, is the narrative of humanity's past. It is understood and studied through anthropology, archaeology, genetics, and linguistics. Since the invention of writing, human history has been studied throug ...

with the mutual aggressions of blind, mindless colonies of molds that cover a boulder adjacent to the Temple of the Sibyl. In January 1870, after only three months at the Institute, Prus was expelled for his insufficient deference toward the martinet Russian-language instructor.

Henceforth he studied on his own while supporting himself mainly as a tutor. As part of his program of self-education, he translated and summarized John Stuart Mill's ''A System of Logic

''A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive'' is an 1843 book by English philosopher John Stuart Mill.

Overview

In this work, he formulated the five principles of inductive reasoning that are known as Mill's Methods. This work is important ...

''.

In 1872, he embarked on a career as a newspaper columnist, while working several months at the Evans, Lilpop and Rau Machine and Agricultural Implement Works in Warsaw. In 1873, Prus delivered two public lectures which illustrate the breadth of his scientific interests: "On the Structure of the Universe", and " On Discoveries and Inventions."

Columnist

As a newspaper columnist, Prus commented on the achievements of scholars and scientists such as John Stuart Mill,

As a newspaper columnist, Prus commented on the achievements of scholars and scientists such as John Stuart Mill, Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

, Alexander Bain, Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression " survival of the fi ...

and Henry Thomas Buckle; urged Poles to study science and technology and to develop industry and commerce;Krystyna Tokarzówna and Stanisław Fita, ''Bolesław Prus, 1847–1912: Kalendarz życia i twórczości'' (Bolesław Prus, 1847–1912: A Calendar of His Life and Work), ''passim.'' encouraged the establishment of charitable institutions to benefit the underprivileged; described the fiction and nonfiction works of fellow writers such as H.G. Wells; and extolled man-made and natural wonders such as the Wieliczka Salt Mine

The Wieliczka Salt Mine ( pl, Kopalnia soli Wieliczka) is a salt mine in the town of Wieliczka, near Kraków in southern Poland.

From Neolithic times, sodium chloride (table salt) was produced there from the upwelling brine. The Wieliczka sa ...

, an 1887 solar eclipse that he witnessed at Mława

Mława (; yi, מלאווע ''Mlave'') is a town in north-east Poland with 30,403 inhabitants in 2020. It is the capital of Mława County. It is situated in the Masovian Voivodeship.

During the invasion of Poland in 1939, the battle of Mława was ...

, planned building of the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; french: links=yes, tour Eiffel ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower.

Locally nicknamed "' ...

for the 1889 Paris Exposition

The Exposition Universelle of 1889 () was a world's fair held in Paris, French Third Republic, France, from 5 May to 31 October 1889. It was the fourth of eight expositions held in the city between 1855 and 1937. It attracted more than thirty-two ...

, and Nałęczów

Nałęczów is a spa town (population 4,800) situated on the Nałęczów Plateau in Puławy County, Lublin Voivodeship, eastern Poland. Nałęczów belongs to Lesser Poland.

History

In the 18th century, the discovery there of healing waters i ...

, where he vacationed for 30 years.

His "Weekly Chronicles" spanned forty years (they have since been reprinted in twenty volumes) and helped prepare the ground for the 20th-century blossoming of Polish science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

and especially mathematics. "Our national life," wrote Prus, "will take a normal course only when we have become a useful, indispensable element of civilization, when we have become able to give nothing for free and to demand nothing for free." The social importance of science and technology recurred as a theme in his novels '' The Doll'' (1889) and ''Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

'' (1895).

Of contemporary thinkers, the one who most influenced Prus and other writers of the Polish " Positivist" period (roughly 1864–1900) was Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression " survival of the fi ...

, the English sociologist who coined the phrase, " survival of the fittest." Prus called Spencer "the Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

of the 19th century" and wrote: "I grew up under the influence of Spencerian evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

ary philosophy and heeded its counsels, not those of Idealist

In philosophy, the term idealism identifies and describes metaphysical perspectives which assert that reality is indistinguishable and inseparable from perception and understanding; that reality is a mental construct closely connected to id ...

or Comtean philosophy." Prus interpreted "survival of the fittest," in the societal sphere, as involving not only competition but also cooperation; and he adopted Spencer's metaphor of society as organism. He used this metaphor to striking effect in his 1884 micro-story " Mold of the Earth," and in the introduction to his 1895 historical novel, ''Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

''.

After Prus began writing regular weekly newspaper columns, his finances stabilized, permitting him on 14 January 1875 to marry a distant cousin on his mother's side, Oktawia Trembińska. She was the daughter of Katarzyna Trembińska, in whose home he had lived, after release from prison, for two years from 1864 to 1866 while completing secondary school. The couple adopted a boy, Emil Trembiński (born 11 September 1886, the son of Prus's brother-in-law Michał Trembiński, who had died on 10 November 1888). Emil was the model for Rascal in chapter 48 of Prus's 1895 novel, ''Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

''. On 18 February 1904, aged seventeen, Emil fatally shot himself in the chest on the doorstep of an unrequited love.

It has been alleged that in 1906, aged 59, Prus had a son, Jan Bogusz Sacewicz. The boy's mother was Alina Sacewicz, widow of Dr. Kazimierz Sacewicz, a socially conscious physician whom Prus had known at Nałęczów. Dr. Sacewicz may have been the model for Stefan Żeromski

Stefan Żeromski ( ; 14 October 1864 – 20 November 1925) was a Polish novelist and dramatist belonging to the Young Poland movement at the turn of the 20th century. He was called the "conscience of Polish literature".

He also wrote under ...

's Dr. Judym in the novel, ''Ludzie bezdomni'' (Homeless People)—a character resembling Dr. Stockman in Henrik Ibsen's play, '' An Enemy of the People''. Prus, known for his affection for children, took a lively interest in little Jan, as attested by a prolific correspondence with Jan's mother (whom Prus attempted to interest in writing). Jan Sacewicz became one of Prus's major legatee

A legatee, in the law of wills, is any individual or organization bequeathed any portion of a testator's estate.

Usage

Depending upon local custom, legatees may be called "devisees". Traditionally, "legatees" took personal property under will a ...

s and an engineer, and died in a German camp after the suppression of the Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising ( pl, powstanie warszawskie; german: Warschauer Aufstand) was a major World War II operation by the Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from German occupation. It occurred in the summer of 1944, and it was led ...

of August–October 1944.

coat-of-arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in its w ...

), reserving his actual name, Aleksander Głowacki, for "serious" writing.

An 1878 incident illustrates the strong feelings that can be aroused in susceptible readers of newspaper columns. Prus had criticized the rowdy behavior of some Warsaw university students at a lecture about the poet Wincenty Pol

Wincenty Pol (20 April 1807 – 2 December 1872) was a Polish poet and geographer.

Life

Pol was born in Lublin (then in Galicia), to Franz Pohl (or Poll), a German in the Austrian service, and his wife Eleonora Longchamps de Berier, from a Fre ...

. The students demanded that Prus retract what he had written. He refused, and, on 26 March 1878, several of them surrounded him outside his home, where he had returned shortly before in the company (for his safety) of two fellow writers; one of the students, Jan Sawicki, slapped Prus's face. Police were summoned, but Prus declined to press charges. Seventeen years later, during his 1895 visit to Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

, Prus's memory of the incident was still so painful that he may have refused (accounts vary) to meet with one of his assailants, Kazimierz Dłuski

Kazimierz Dłuski (; 1855–1930) was a Polish physician, and social and political activist. He was a member of the Polish Socialist Party. In later life, he was a founder and activist of many non-governmental organizations; he was the founder and ...

, and his wife Bronisława Dłuska

Bronisława Dłuska (; ; 28 March 186515 April 1939) was a Polish physician, and co-founder and first director of Warsaw's Maria Skłodowska-Curie Institute of Oncology. She was married to political activist Kazimierz Dłuski, and was an older ...

( Marie Skłodowska Curie's sister who 19 years later, in 1914, scolded Joseph Conrad for writing his novels and stories in English, rather than in Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

for the benefit of Polish culture). These curiously interlinked incidents involving the Dłuskis and the two authors perhaps illustrate the contemporary intensity of aggrieved Polish national pride.

In 1882, on the recommendation of an earlier editor-in-chief, the prophet of Polish Positivism

Polish Positivism was a social, literary and History of philosophy in Poland#Positivism, philosophical movement that became dominant in late-19th-century Partitions of Poland, partitioned Poland following the suppression of the January Uprising, J ...

, Aleksander Świętochowski

Aleksander Świętochowski (18 January 1849 – 25 April 1938) was a Polish writer, educator, and philosopher of the Positivism in Poland, Positivist period that followed the January Uprising, January 1863 Uprising.

He was widely regarded as the ...

, Prus succeeded to the editorship of the Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

daily ''Nowiny'' (News). The newspaper had been bought in June 1882 by financier Stanisław Kronenberg. Prus resolved, in the best Positivist fashion, to make it "an observatory of societal facts"—an instrument for advancing the development of his country. After less than a year, however, ''Nowiny''—which had had a history of financial instability since changing in July 1878 from a Sunday paper to a daily—folded, and Prus resumed writing columns

A column or pillar in architecture and structural engineering is a structural element that transmits, through compression, the weight of the structure above to other structural elements below. In other words, a column is a compression membe ...

.Pieścikowski, Edward, ''Bolesław Prus'', 152. He continued working as a journalist to the end of his life, well after he had achieved success as an author of short stories and novels.

In an 1884 newspaper column, published two decades before the Wright brothers flew, Prus anticipated that powered flight would not bring humanity closer to universal comity: "Are there among flying creatures only doves, and no hawks? Will tomorrow’s flying machine obey only the honest and the wise, and not fools and knaves?... The expected societal changes may come down to a new form of chase and combat in which the man who is vanquished on high will fall and smash the skull of the peaceable man down below."

In a January 1909 column, Prus discussed H.G. Wells's 1901 book, ''Anticipations

''Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress upon Human Life and Thought'', generally known as ''Anticipations'', was written by H.G. Wells at the age of 34. He later called the book, which became a bestseller, "the keys ...

'', including Wells's prediction that by the year 2000, following the defeat of German imperialism "on land and at sea," there would be a European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

that would reach eastward to include the western Slavs

The West Slavs are Slavic peoples who speak the West Slavic languages. They separated from the common Slavic group around the 7th century, and established independent polities in Central Europe by the 8th to 9th centuries. The West Slavic langu ...

—the Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in C ...

, Czechs

The Czechs ( cs, Češi, ; singular Czech, masculine: ''Čech'' , singular feminine: ''Češka'' ), or the Czech people (), are a West Slavic ethnic group and a nation native to the Czech Republic in Central Europe, who share a common ancestry, ...

and Slovaks. The latter peoples, along with the Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the Urali ...

and six other countries, did in fact join the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

in 2004.

Fiction

In time, Prus adopted the French Positivist critic

In time, Prus adopted the French Positivist critic Hippolyte Taine

Hippolyte Adolphe Taine (, 21 April 1828 – 5 March 1893) was a French historian, critic and philosopher. He was the chief theoretical influence on French naturalism, a major proponent of sociological positivism and one of the first practition ...

's concept of the arts, including literature, as a second means, alongside the sciences, of studying reality, and he devoted more attention to his sideline of short-story writer. Prus's stories, which met with great acclaim, owed much to the literary influence of Polish novelist Józef Ignacy Kraszewski

Józef Ignacy Kraszewski (28 July 1812 – 19 March 1887) was a Polish writer, publisher, historian, journalist, scholar, painter, and author who produced more than 200 novels and 150 novellas, short stories, and art reviews, which makes him the ...

and, among English-language writers, to Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

and Mark Twain. His fiction was also influenced by French writers Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

, Gustave Flaubert

Gustave Flaubert ( , , ; 12 December 1821 – 8 May 1880) was a French novelist. Highly influential, he has been considered the leading exponent of literary realism in his country. According to the literary theorist Kornelije Kvas, "in Flauber ...

, Alphonse Daudet

Alphonse Daudet (; 13 May 184016 December 1897) was a French novelist. He was the husband of Julia Daudet and father of Edmée, Léon and Lucien Daudet.

Early life

Daudet was born in Nîmes, France. His family, on both sides, belonged to the ...

and Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, also , ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism, and an important contributor to the development of ...

.

Prus wrote several dozen stories, originally published in newspapers and ranging in length from micro-story to novella. Characteristic of them are Prus's keen observation of everyday life and sense of humor, which he had early honed as a contributor to humor magazines. The prevalence of themes from everyday life is consistent with the Polish Positivist artistic program, which sought to portray the circumstances of the populace rather than those of the Romantic hero

The Romantic hero is a literary archetype referring to a character that rejects established norms and conventions, has been rejected by society, and has themselves at the center of their own existence. The Romantic hero is often the protagonist in ...

es of an earlier generation. The literary period in which Prus wrote was ostensibly a prosaic one, by contrast with the poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek ''poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings i ...

of the Romantics; but Prus's prose is often a poetic prose. His stories also often contain elements of fantasy

Fantasy is a genre of speculative fiction involving magical elements, typically set in a fictional universe and sometimes inspired by mythology and folklore. Its roots are in oral traditions, which then became fantasy literature and d ...

or whimsy. A fair number originally appeared in New Year

New Year is the time or day currently at which a new calendar year begins and the calendar's year count increments by one. Many cultures celebrate the event in some manner. In the Gregorian calendar, the most widely used calendar system to ...

's issues of newspapers.

Prus long eschewed writing historical fiction, arguing that it must inevitably distort history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

. He criticized contemporary historical novelists for their lapses in historical accuracy, including Henryk Sienkiewicz's failure, in the military scenes in his ''Trilogy

A trilogy is a set of three works of art that are connected and can be seen either as a single work or as three individual works. They are commonly found in literature, film, and video games, and are less common in other art forms. Three-part wor ...

'' portraying 17th-century Polish history, to describe the logistics

Logistics is generally the detailed organization and implementation of a complex operation. In a general business sense, logistics manages the flow of goods between the point of origin and the point of consumption to meet the requirements of ...

of warfare. It was only in 1888, when Prus was forty, that he wrote his first historical fiction, the stunning short story, " A Legend of Old Egypt." This story, a few years later, served as a preliminary sketch for his only historical novel, ''Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

'' (1895).

Eventually Prus composed four novels on what he had referred to in an 1884 letter as "great questions of our age": '' The Outpost'' (''Placówka'', 1886) on the Polish peasant; '' The Doll'' (''Lalka'', 1889) on the aristocracy and townspeople

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. T ...

and on idealists

In philosophy, the term idealism identifies and describes metaphysics, metaphysical perspectives which assert that reality is indistinguishable and inseparable from perception and understanding; that reality is a mental construct closely con ...

struggling to bring about social reform

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary move ...

s; '' The New Woman'' (''Emancypantki'', 1893) on feminist concerns; and his only historical novel, ''Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

'' (''Faraon'', 1895), on mechanisms of political power

In social science and politics, power is the social production of an effect that determines the capacities, actions, beliefs, or conduct of actors. Power does not exclusively refer to the threat or use of force ( coercion) by one actor agains ...

. The work of greatest sweep and most universal appeal is ''Pharaoh''. Prus's novels, like his stories, were originally published in newspaper serialization.

After having sold ''Pharaoh'' to the publishing firm of Gebethner and Wolff, Prus embarked, on 16 May 1895, on a four-month journey abroad. He visited Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

, Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

, Karlsbad, Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

, Stuttgart and Rapperswil

Rapperswil (Swiss German: or ;Andres Kristol, ''Rapperswil SG (See)'' in: ''Dictionnaire toponymique des communes suisses – Lexikon der schweizerischen Gemeindenamen – Dizionario toponomastico dei comuni svizzeri (DTS, LSG)'', Centre de dial ...

. At the latter Swiss town he stayed two months (July–August), nursing his agoraphobia and spending much time with his friends, the promising young writer Stefan Żeromski

Stefan Żeromski ( ; 14 October 1864 – 20 November 1925) was a Polish novelist and dramatist belonging to the Young Poland movement at the turn of the 20th century. He was called the "conscience of Polish literature".

He also wrote under ...

and his wife Oktawia. The couple sought Prus's help for the Polish National Museum, housed in the Rapperswil Castle, where Żeromski was librarian.

The final stage of Prus's journey took him to Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

, where he was prevented by his agoraphobia from crossing the Seine River

)

, mouth_location = Le Havre/Honfleur

, mouth_coordinates =

, mouth_elevation =

, progression =

, river_system = Seine basin

, basin_size =

, tributaries_left = Yonne, Loing, Eure, Risle

, tributaries ...

to visit the city's southern Left Bank

In geography, a bank is the land alongside a body of water. Different structures are referred to as ''banks'' in different fields of geography, as follows.

In limnology (the study of inland waters), a stream bank or river bank is the terra ...

. He was nevertheless pleased to find that his descriptions of Paris in ''The Doll'' had been on the mark (he had based them mainly on French-language publications). From Paris, he hurried home to recuperate at Nałęczów

Nałęczów is a spa town (population 4,800) situated on the Nałęczów Plateau in Puławy County, Lublin Voivodeship, eastern Poland. Nałęczów belongs to Lesser Poland.

History

In the 18th century, the discovery there of healing waters i ...

from his journey, the last that he made abroad.

Later years

Over the years, Prus lent his support to many charitable and social causes, but there was one event he came to rue for the broad criticism it brought him: his participation in welcoming Russia's

Over the years, Prus lent his support to many charitable and social causes, but there was one event he came to rue for the broad criticism it brought him: his participation in welcoming Russia's tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

during Nicholas II's 1897 visit to Warsaw. As a rule, Prus did not affiliate himself with political parties, as this might compromise his journalistic objectivity. His associations, by design and temperament, were with individuals and select worthy causes rather than with large groups.

The disastrous January 1863 Uprising had persuaded Prus that society must advance through learning, work and commerce rather than through risky social upheavals. He departed from this stance, however, in 1905, when Imperial Russia experienced defeat in the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

and Poles demanded autonomy and reforms. On 20 December 1905, in the first issue of a short-lived periodical, ''Młodość'' (Youth), he published an article, "''Oda do młodości''" ("Ode to Youth"), whose title harked back to an 1820 poem by Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (; 24 December 179826 November 1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist, essayist, publicist, translator and political activist. He is regarded as national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. A principal figure in Polish Ro ...

. Prus wrote, in reference to his earlier position on revolution and strikes: "with the greatest pleasure, I admit it—I was wrong!"

Czesław Miłosz

Czesław Miłosz (, also , ; 30 June 1911 – 14 August 2004) was a Polish-American poet, prose writer, translator, and diplomat. Regarded as one of the great poets of the 20th century, he won the 1980 Nobel Prize in Literature. In its citation, ...

has called ''Children'' one of Prus's weakest works.

Prus's last novel to meet with popular acclaim was ''Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

'', completed in 1895. Depicting the demise of ancient Egypt's Twentieth Dynasty

The Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XX, alternatively 20th Dynasty or Dynasty 20) is the third and last dynasty of the Ancient Egyptian New Kingdom period, lasting from 1189 BC to 1077 BC. The 19th and 20th Dynasties furthermore togeth ...

and New Kingdom three thousand years earlier, ''Pharaoh'' had also reflected Poland's loss of independence a century before in 1795—an independence whose post-World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

restoration Prus did not live to see.

On 19 May 1912, in his Warsaw apartment at 12 Wolf Street (''ulica Wilcza 12''), near Triple Cross Square

Three Crosses Square ( pl, Plac Trzech Krzyży, , also "Square of Three Crosses", "Three Cross Square", and "Triple Cross Square") is an important square in the central district of Warsaw, Poland. It lies on that city's Royal Route and links ...

, his forty-year journalistic and literary career came to an end when the 64-year-old author died.

The beloved agoraphobic

Agoraphobia is a mental and behavioral disorder, specifically an anxiety disorder characterized by symptoms of anxiety in situations where the person perceives their environment to be unsafe with no easy way to escape. These situations can ...

writer was mourned by the nation that he had striven, as soldier, thinker, and writer, to rescue from oblivion. Thousands attended his 22 May 1912 funeral service at St. Alexander's Church on nearby Triple Cross Square

Three Crosses Square ( pl, Plac Trzech Krzyży, , also "Square of Three Crosses", "Three Cross Square", and "Triple Cross Square") is an important square in the central district of Warsaw, Poland. It lies on that city's Royal Route and links ...

(''Plac Trzech Krzyży'') and his interment at Powązki Cemetery

Powązki Cemetery (; pl, Cmentarz Powązkowski), also known as Stare Powązki ( en, Old Powązki), is a historic necropolis located in Wola district, in the western part of Warsaw, Poland. It is the most famous cemetery in the city and one of t ...

.

Prus's tomb was designed by his nephew, the noted sculptor Stanisław Jackowski. On three sides it bears, respectively, the novelist's name, ''Aleksander Głowacki'', his years of birth and death, and his pen name, ''Bolesław Prus''. The epitaph

An epitaph (; ) is a short text honoring a deceased person. Strictly speaking, it refers to text that is inscribed on a tombstone or plaque, but it may also be used in a figurative sense. Some epitaphs are specified by the person themselves be ...

on the fourth side, “''Serce Serc''” (“Heart of Hearts”), was deliberately borrowed from the Latin “''Cor Cordium''” on the grave of the English Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

's Protestant Cemetery. Below the epitaph stands the figure of a little girl embracing the tomb — a figure emblematic of Prus's well-known empathy and affection for children.

Prus's widow, Oktawia Głowacka, survived him by twenty-four years, dying on 25 October 1936.

In 1902 the editor of the Warsaw ''Kurier Codzienny'' (Daily Courier) had opined that, if Prus’s writings had been well known abroad, he should have received one of the recently created Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

s.

Legacy

Nałęczów

Nałęczów is a spa town (population 4,800) situated on the Nałęczów Plateau in Puławy County, Lublin Voivodeship, eastern Poland. Nałęczów belongs to Lesser Poland.

History

In the 18th century, the discovery there of healing waters i ...

, near Lublin in eastern Poland. Outside the palace is a sculpture of Prus seated on a bench. Another statuary monument to Prus at Nałęczów, sculpted by Alina Ślesińska, was unveiled on 8 May 1966. It was at Nałęczów that Prus vacationed for thirty years from 1882 until his death, and that he met the young Stefan Żeromski

Stefan Żeromski ( ; 14 October 1864 – 20 November 1925) was a Polish novelist and dramatist belonging to the Young Poland movement at the turn of the 20th century. He was called the "conscience of Polish literature".

He also wrote under ...

. Prus stood witness at Żeromski's 1892 wedding and generously helped foster the younger man's literary career.

While Prus espoused a positivist and realist outlook, much in his fiction shows qualities compatible with pre- 1863-Uprising Polish Romantic literature. Indeed, he held the Polish Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (; 24 December 179826 November 1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist, essayist, publicist, translator and political activist. He is regarded as national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. A principal figure in Polish Ro ...

in high regard. Prus's novels in turn, especially '' The Doll'' and ''Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

'', with their innovative composition techniques, blazed the way for the 20th-century Polish novel.

Prus's novel '' The Doll'', with its rich realistic detail and simple, functional language, was considered by Czesław Miłosz

Czesław Miłosz (, also , ; 30 June 1911 – 14 August 2004) was a Polish-American poet, prose writer, translator, and diplomat. Regarded as one of the great poets of the 20th century, he won the 1980 Nobel Prize in Literature. In its citation, ...

to be the great Polish novel.

Joseph Conrad, during his 1914 visit to Poland just as World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

was breaking out, "delighted in his beloved Prus" and read everything by the ten-years-older, recently deceased author that he could get his hands on. He pronounced '' The New Woman'' (the first novel by Prus that he read) "better than Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

"—Dickens being a favorite author of Conrad's. Miłosz, however, thought '' The New Woman'' "as a whole... an artistic failure..." Zygmunt Szweykowski similarly faulted ''The New Womans loose, tangential construction; but this, in his view, was partly redeemed by Prus's humor and by some superb episodes, while "The tragedy of Mrs. Latter and the picture of he town of

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

Iksinów are among the peak achievements of olishnovel-writing."

''Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

'', a study of political power

In social science and politics, power is the social production of an effect that determines the capacities, actions, beliefs, or conduct of actors. Power does not exclusively refer to the threat or use of force ( coercion) by one actor agains ...

, became the favorite novel of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

, prefigured the fate of U.S. President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

, and continues to point analogies to more recent times. ''Pharaoh'' is often described as Prus's "best-composed novel"—indeed, "one of the best-composed f allPolish novels." This was due in part to ''Pharaoh'' having been composed complete prior to newspaper serialization, rather than being written in installments just before printing, as was the case with Prus's earlier major novels.

''The Doll'' and ''Pharaoh'' are available in English versions. ''The Doll'' has been translated into twenty-eight languages, and ''Pharaoh'' into twenty. In addition, ''The Doll'' has been filmed several times, and been produced as a 1977 television miniseries

A miniseries or mini-series is a television series that tells a story in a predetermined, limited number of episodes. " Limited series" is another more recent US term which is sometimes used interchangeably. , the popularity of miniseries format ...

, ''Pharaoh'' was adapted into a 1966 feature film.

Between 1897 and 1899 Prus serialized in the Warsaw ''Daily Courier'' (''Kurier Codzienny'') a monograph on '' The Most General Life Ideals'' (''Najogólniejsze ideały życiowe''), which systematized ethical ideas that he had developed over his career regarding ''happiness'', ''utility'' and ''perfection'' in the lives of individuals and societies. In it he returned to the society-organizing (i.e., political) interests that had been frustrated during his ''Nowiny'' editorship fifteen years earlier. A book edition appeared in 1901 (2nd, revised edition, 1905). This work, rooted in Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

's Utilitarian philosophy and Herbert Spencer's view of society-as-organism, retains interest especially for philosophers

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

and social scientists

Social science is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the field of sociology, the original "science of soc ...

.

Another of Prus's learned projects remained incomplete at his death. He had sought, over his writing career, to develop a coherent theory of literary composition. Notes of his from 1886 to 1912 were never put together into a finished book as he had intended. His precepts included the maxim, "Noun

A noun () is a word that generally functions as the name of a specific object or set of objects, such as living creatures, places, actions, qualities, states of existence, or ideas.Example nouns for:

* Living creatures (including people, alive, ...

s, nouns and more nouns." Some particularly intriguing fragments describe Prus's combinatorial

Combinatorics is an area of mathematics primarily concerned with counting, both as a means and an end in obtaining results, and certain properties of finite structures. It is closely related to many other areas of mathematics and has many ap ...

calculations of the millions of potential "individual types" of human characters

Character or Characters may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''Character'' (novel), a 1936 Dutch novel by Ferdinand Bordewijk

* ''Characters'' (Theophrastus), a classical Greek set of character sketches attributed to The ...

, given a stated number of "individual traits."

A curious comparative-literature aspect has been noted to Prus's career, which paralleled that of his American contemporary, Ambrose Bierce

Ambrose Gwinnett Bierce (June 24, 1842 – ) was an American short story writer, journalist, poet, and American Civil War veteran. His book '' The Devil's Dictionary'' was named as one of "The 100 Greatest Masterpieces of American Literature" by ...

(1842–1914). Each was born and reared in a rural area and had a "Polish" connection (Bierce, born five years before Prus, was reared in Kosciusko County, Indiana

Kosciusko County ( ) is a county in the U.S. state of Indiana. At the 2020 United States Census, its population was 80,240. The county seat (and only incorporated city) is Warsaw.

The county was organized in 1836. It was named for the Polish g ...

, and attended high school

A secondary school describes an institution that provides secondary education and also usually includes the building where this takes place. Some secondary schools provide both '' lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) and ''upper seconda ...

at the county seat

A county seat is an administrative center, seat of government, or capital city of a county or civil parish. The term is in use in Canada, China, Hungary, Romania, Taiwan, and the United States. The equivalent term shire town is used in the US st ...

, Warsaw, Indiana

Warsaw is a city in and the county seat of Kosciusko County, Indiana, United States. Warsaw has a population of 13,559 as of the 2010 U.S. Census. Warsaw also borders a smaller town, Winona Lake.

Etymology

Warsaw, named after the capital of ...

). Each became a war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

casualty

Casualty may refer to:

*Casualty (person), a person who is killed or rendered unfit for service in a war or natural disaster

**Civilian casualty, a non-combatant killed or injured in warfare

* The emergency department of a hospital, also known as ...

with combat head trauma

A head injury is any injury that results in trauma to the skull or brain. The terms ''traumatic brain injury'' and ''head injury'' are often used interchangeably in the medical literature. Because head injuries cover such a broad scope of inju ...

—Prus in 1863 in the Polish 1863–65 Uprising; Bierce in 1864 in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

. Each experienced false starts in other occupations, and at twenty-five became a journalist for the next forty years; failed to sustain a career as editor-in-chief; achieved celebrity as a short-story writer; lost a son in tragic circumstances (Prus, an adopted son; Bierce, both his sons); attained superb humorous effects by portraying human egoism (Prus especially in ''Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

'', Bierce in ''The Devil's Dictionary

''The Devil's Dictionary'' is a satirical dictionary written by American journalist Ambrose Bierce, consisting of common words followed by humorous and satirical definitions. The lexicon was written over three decades as a series of installments ...

''); was dogged from early adulthood by a health problem (Prus, agoraphobia; Bierce, asthma

Asthma is a long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wheezing, co ...

); and died within two years of the other (Prus in 1912; Bierce presumably in 1914). Prus, however, unlike Bierce, went on from short stories to write novels.

In Prus's lifetime and since, his contributions to Polish literature and culture have been memorialized without regard to the nature of the political system prevailing at the time. His 50th birthday, in 1897, was marked by special newspaper issues celebrating his 25 years as a journalist and fiction writer, and a portrait of him was commissioned from artist Antoni Kamieński.

The town where Prus was born,

In Prus's lifetime and since, his contributions to Polish literature and culture have been memorialized without regard to the nature of the political system prevailing at the time. His 50th birthday, in 1897, was marked by special newspaper issues celebrating his 25 years as a journalist and fiction writer, and a portrait of him was commissioned from artist Antoni Kamieński.

The town where Prus was born, Hrubieszów

Hrubieszów (; uk, Грубешів, Hrubeshiv; yi, הרוביעשאָוו, Hrubyeshov) is a town in southeastern Poland, with a population of around 18,212 (2016). It is the capital of Hrubieszów County within the Lublin Voivodeship.

Through ...

, near the present Polish– Ukrainian border, is graced by an outdoor sculpture of him.

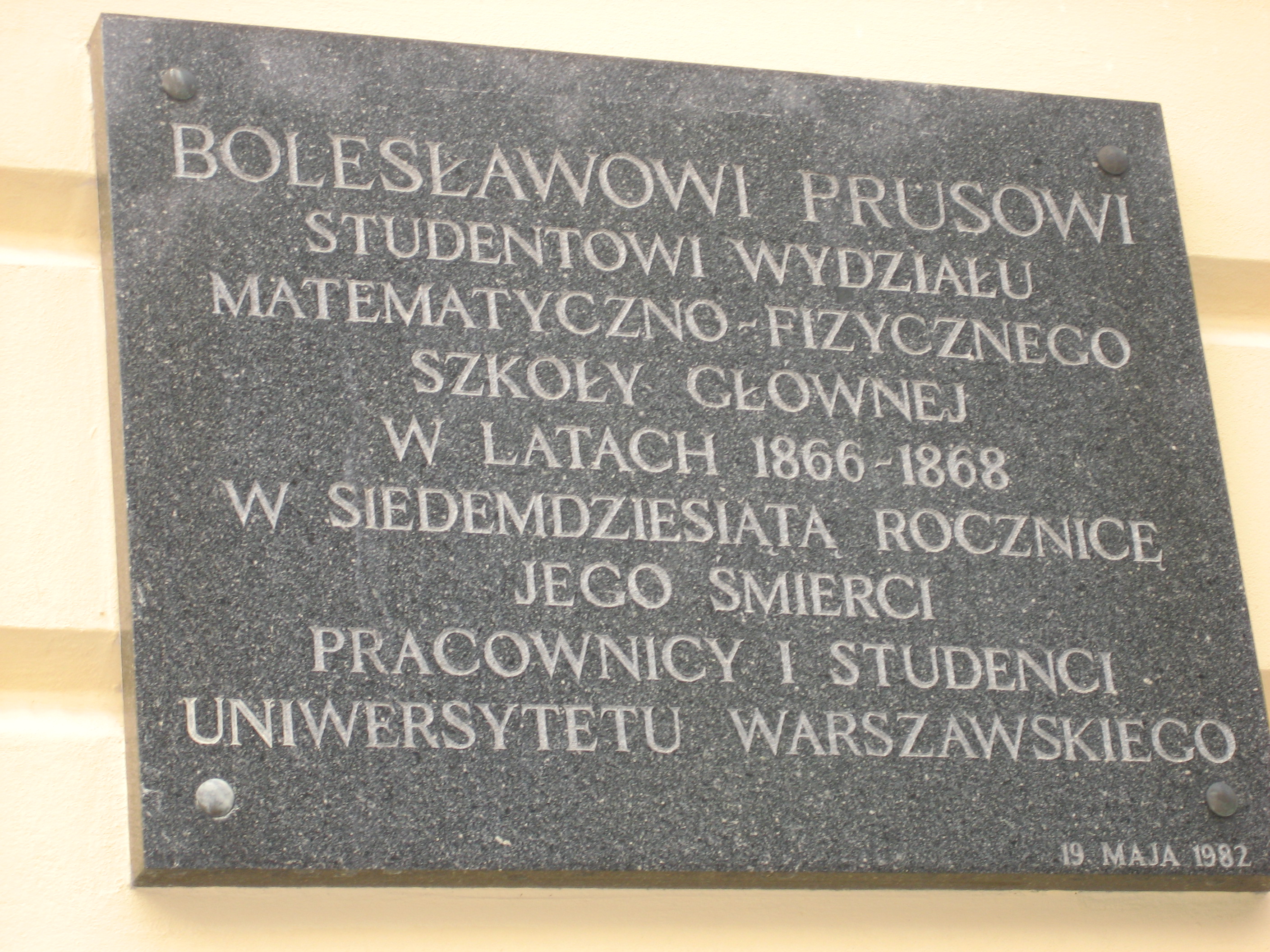

A 1982 plaque on Warsaw University

The University of Warsaw ( pl, Uniwersytet Warszawski, la, Universitas Varsoviensis) is a public university in Warsaw, Poland. Established in 1816, it is the largest institution of higher learning in the country offering 37 different fields of ...

's administration building, the historic Kazimierz Palace

The Kazimierz Palace ( pl, Pałac Kazimierzowski) is a rebuilt palace in Warsaw, Poland. It is adjacent to the Royal Route, at '' Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28''.

Originally built in 1637-41, it was first rebuilt in 1660 for King John II Casim ...

, commemorates Prus's years at the University in 1866–68. Across the street (''Krakowskie Przedmieście

Krakowskie Przedmieście (, literally: ''Cracow Fore-town''; french: link=no, Faubourg de Cracovie), often abbreviated to Krakowskie, is one of the best known and most prestigious streets of Poland's capital Warsaw, surrounded by historic palaces ...

'') from the University, in Holy Cross Church, a 1936 plaque by Prus's nephew Stanisław Jackowski, featuring Prus's profile, is dedicated to the memory of the "great writer and teacher of the nation."

On the front of Warsaw's present-day ''ulica Wilcza 12'', the site of Prus's last home, is a plaque commemorating the earlier, now-nonexistent building's most famous resident. A few hundred meters from there, ''ulica Bolesława Prusa'' (Bolesław Prus Street) debouches into the southeast corner of Warsaw's Triple Cross Square

Three Crosses Square ( pl, Plac Trzech Krzyży, , also "Square of Three Crosses", "Three Cross Square", and "Triple Cross Square") is an important square in the central district of Warsaw, Poland. It lies on that city's Royal Route and links ...

. In this square stands St. Alexander's Church, where Prus's funeral was held.

In 1937, plaques were installed at Warsaw's ''Krakowskie Przedmieście

Krakowskie Przedmieście (, literally: ''Cracow Fore-town''; french: link=no, Faubourg de Cracovie), often abbreviated to Krakowskie, is one of the best known and most prestigious streets of Poland's capital Warsaw, surrounded by historic palaces ...

'' ''4'' and ''7'', where the two chief characters of Prus's novel '' The Doll'', Stanisław Wokulski and Ignacy Rzecki, respectively, were deduced to have resided. On the same street, in a park adjacent to the Hotel Bristol

The Hotel Bristol is the name of more than 200 hotels around the world. They range from grand European hotels, such as Hôtel Le Bristol Paris and the Hotel Bristol in Warsaw or Vienna to budget hotels, such as the SRO (single room occupancy) ...

, near the site of a newspaper for which Prus wrote, stands a twice-life-size statue of Prus, sculpted in 1977 by Anna Kamieńska-Łapińska; it is some 12 feet tall, on a minimal pedestal as befits an author who walked the same ground with his fellow men.

Consonant with Prus's interest in commerce and technology, a Polish Ocean Lines freighter has been named for him.

For 10 years, from 1975 to 1984, Poles honored Prus's memory with a 10- zloty coin featuring his profile. In 2012, to mark the 100th anniversary of his death, the Polish mint produced three coins with individual designs: in gold, silver, and an aluminum-zinc alloy.

Prus's fiction and nonfiction writings continue relevant in our time.Witness articles such as Aleksander Kaczorowski, ''"My z Wokulskiego"'' ("We escendantsof Wokulski) The_Doll''.html" ;"title="rotagonist of Prus's novel '' The Doll''">rotagonist of Prus's novel '' The Doll'' in ''Plus Minus'', the ''Rzeczpospolita

() is the official name of Poland and a traditional name for some of its predecessor states. It is a compound of "thing, matter" and "common", a calque of Latin ''rés pública'' ( "thing" + "public, common"), i.e. ''republic'', in Engli ...

'' (Republic) Weekly agazine no. 33 (1016), Saturday-Sunday, 18–19 August 2012, pp. P8-P9.

Works

Following is a chronological list of notable works by Bolesław Prus. Translated titles are given, followed by original titles and dates of publication.

Novels

* ''Souls in Bondage'' (''Dusze w niewoli'', written 1876, serialized 1877) * ''Fame'' (''Sława'', begun 1885, never finished) * '' The Outpost'' (''Placówka'', 1885–86) * '' The Doll'' (''Lalka'', 1887–89) * '' The New Woman'' (''Emancypantki'', 1890–93) * ''Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

'' (''Faraon'', written 1894–95; serialized 1895–96; published in book form 1897)

* ''Children'' (''Dzieci'', 1908; approximately the first nine chapters had originally appeared, in a somewhat different form, in 1907 as ''Dawn'' 'Świt''

* ''Changes'' (''Przemiany'', begun 1911–12; unfinished)

Stories

* "Granny's Troubles" (''"Kłopoty babuni,"'' 1874) * "The Palace and the Hovel" (''"Pałac i rudera,"'' 1875) * "The Ball Gown" (''"Sukienka balowa,"'' 1876) * "An Orphan's Lot" (''"Sieroca dola,"'' 1876) * "Eddy's Adventures" (''"Przygody Edzia,"'' 1876) * "Damnable Happiness" (''"Przeklęte szczęście,"'' 1876) * "The Honeymoon" (''"Miesiąc nektarowy"'', 1876) * "In the Struggle with Life" (''"W walce z życiem"'', 1877) * "Christmas Eve" (''"Na gwiazdkę"'', 1877) * "Grandmother's Box" (''"Szkatułka babki,"'' 1878) * "Little Stan's Adventure" (''"Przygoda Stasia,"'' 1879) * "New Year" (''"Nowy rok,"'' 1880) * "The Returning Wave" (''"Powracająca fala,"'' 1880) * "Michałko" (1880) * "Antek" (1880) * "The Convert" (''"Nawrócony,"'' 1880) * " The Barrel Organ" (''"Katarynka,"'' 1880) * "One of Many" (''"Jeden z wielu,"'' 1882) * " The Waistcoat" (''"Kamizelka,"'' 1882) * "Him" (''"On,"'' 1882) * " Fading Voices" (''"Milknące głosy,"'' 1883) * "Sins of Childhood" (''"Grzechy dzieciństwa,"'' 1883) * " Mold of the Earth" (''"Pleśń świata,"'' 1884: a brilliant micro-story portrayinghuman history

Human history, also called world history, is the narrative of humanity's past. It is understood and studied through anthropology, archaeology, genetics, and linguistics. Since the invention of writing, human history has been studied throug ...

as an endless series of conflicts among mold

A mold () or mould () is one of the structures certain fungi can form. The dust-like, colored appearance of molds is due to the formation of spores containing fungal secondary metabolites. The spores are the dispersal units of the fungi. Not ...

colonies inhabiting a common boulder)

* " The Living Telegraph" (''"Żywy telegraf,"'' 1884)

* "Orestes

In Greek mythology, Orestes or Orestis (; grc-gre, Ὀρέστης ) was the son of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon, and the brother of Electra. He is the subject of several Ancient Greek plays and of various myths connected with his madness an ...

and Pylades

In Greek mythology, Pylades (; Ancient Greek: Πυλάδης) was a Phocian prince as the son of King Strophius and Anaxibia who is the daughter of Atreus and sister of Agamemnon and Menelaus. He is mostly known for his relationship with his cou ...

" (''"Orestes i Pylades,"'' 1884)

* "She Loves Me?... She Loves Me Not?..." (''"Kocha—nie kocha?..."'', a micro-story, 1884)

* "The Mirror" (''"Zwierciadło,"'' 1884)

* "On Vacation" (''"Na wakacjach,"'' 1884)

* "An Old Tale" (''"Stara bajka,"'' 1884)

* "In the Light of the Moon" (''"Przy księżycu,"'' 1884)

* "A Mistake" (''"Omyłka,"'' 1884)

* "Mr. Dutkowski and His Farm" (''"Pan Dutkowski i jego folwark,"'' 1884)

* "Musical Echoes" (''"Echa muzyczne,"'' 1884)

* "In the Mountains" (''"W górach,"'' 1885)

* " Shades" (''"Ciene,"'' 1885: an evocative micro-story on existential

Existentialism ( ) is a form of philosophical inquiry that explores the problem of human existence and centers on human thinking, feeling, and acting. Existentialist thinkers frequently explore issues related to the meaning, purpose, and valu ...

themes)

* "Anielka" (1885)

* "A Strange Story" (''"Dziwna historia,"'' 1887)

* " A Legend of Old Egypt" (''"Z legend dawnego Egiptu,"'' 1888: Prus's stunning first piece of historical fiction; a preliminary sketch for his only historical novel, ''Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

'', which he wrote in 1894–95)

* "The Dream" (''"Sen,"'' 1890)

* "Lives of Saints" (''"Z żywotów świętych,"'' 1891–92)

* "Reconciled" (''"Pojednani,"'' 1892)

* "A Composition by Little Frank: About Mercy" (''"Z wypracowań małego Frania. O miłosierdziu,"'' 1898)

* "The Doctor's Story" (''"Opowiadanie lekarza,"'' 1902)

* "Memoirs of a Cyclist" (''"Ze wspomnień cyklisty,"'' 1903)

* "Revenge" (''"Zemsta,"'' 1908)

* "Phantoms" (''"Widziadła,"'' 1911, first published 1936)

Nonfiction

* "Letters from the Old Camp" (''"Listy ze starego obozu"''), 1872: Prus's first composition signed with the pseudonym ''Bolesław Prus''. * "On the Structure of the Universe" (''"O budowie wszechświata"''), public lecture, 23 February 1873. * " On Discoveries and Inventions" (''"O odkryciach i wynalazkach"''): A Public Lecture Delivered on 23 March 1873 by Aleksander Głowacki olesław Prus Passed by the ussianCensor (Warsaw, 21 April 1873), Warsaw, Printed by F. Krokoszyńska, 1873* "Travel Notes (Wieliczka)" [''"Kartki z podróży (Wieliczka),"'' 1878—Prus's impressions of the

Wieliczka Salt Mine

The Wieliczka Salt Mine ( pl, Kopalnia soli Wieliczka) is a salt mine in the town of Wieliczka, near Kraków in southern Poland.

From Neolithic times, sodium chloride (table salt) was produced there from the upwelling brine. The Wieliczka sa ...

; these helped inform the conception of the Labyrinth#The Egyptian labyrinth, Egyptian Labyrinth in Prus's 1895 novel, ''Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

'']

* "A Word to the Public" (''"Słówko do publiczności,"'' 11 June 1882 — Prus's inaugural address to readers as the new editor-in-chief of the daily, ''Nowiny'' ews famously proposing to make it "an observatory of societal facts, just as there are observatories that study the movements of heavenly bodies, or—climatic changes.")

* "Sketch for a Program under the Conditions of the Present Development of Society" (''"Szkic programu w warunkach obecnego rozwoju społeczeństwa,"'' 23–30 March 1883— swan song of Prus's editorship of ''Nowiny'')

* "''With Sword and Fire''—Henryk Sienkiewicz's Novel of Olden Times" (''"''Ogniem i mieczem''—powieść z dawnych lat Henryka Sienkiewicza,"'' 1884—Prus's review of Sienkiewicz's historical novel, and essay on historical novels)

* "The Paris Tower" (''"Wieża paryska,"'' 1887—whimsical divagations involving the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; french: links=yes, tour Eiffel ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower.

Locally nicknamed "' ...

, the world's tallest structure, then yet to be constructed for the 1889 Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

'' Exposition Universelle'')

* "Travels on Earth and in Heaven" (''"Wędrówka po ziemi i niebie,"'' 1887—Prus's impressions of a solar eclipse that he observed at Mława

Mława (; yi, מלאווע ''Mlave'') is a town in north-east Poland with 30,403 inhabitants in 2020. It is the capital of Mława County. It is situated in the Masovian Voivodeship.

During the invasion of Poland in 1939, the battle of Mława was ...

; these helped inspire the solar-eclipse scenes in his 1895 novel, ''Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

'')

* "A Word about Positive Criticism" (''"Słówko o krytyce pozytywnej,"'' 1890—Prus's part of a polemic

Polemic () is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called ''polemics'', which are seen in arguments on controversial topic ...

with Positivist guru

Guru ( sa, गुरु, IAST: ''guru;'' Pali'': garu'') is a Sanskrit term for a "mentor, guide, expert, or master" of certain knowledge or field. In pan-Indian traditions, a guru is more than a teacher: traditionally, the guru is a reverential ...

Aleksander Świętochowski

Aleksander Świętochowski (18 January 1849 – 25 April 1938) was a Polish writer, educator, and philosopher of the Positivism in Poland, Positivist period that followed the January Uprising, January 1863 Uprising.

He was widely regarded as the ...

)

* "Eusapia Palladino" (1893—a newspaper column

A column is a recurring piece or article in a newspaper, magazine or other publication, where a writer expresses their own opinion in few columns allotted to them by the newspaper organisation. Columns are written by columnists.

What differe ...

about mediumistic

Mediumship is the practice of purportedly mediating communication between familiar spirits or spirits of the dead and living human beings. Practitioners are known as "mediums" or "spirit mediums". There are different types of mediumship or spir ...

séance

A séance or seance (; ) is an attempt to communicate with spirits. The word ''séance'' comes from the French word for "session", from the Old French ''seoir'', "to sit". In French, the word's meaning is quite general: one may, for example, spea ...

s held in Warsaw by the Italian Spiritualist, Eusapia Palladino

Eusapia Palladino (alternative spelling: ''Paladino''; 21 January 1854 – 16 May 1918) was an Italian Spiritualist physical medium. She claimed extraordinary powers such as the ability to levitate tables, communicate with the dead through ...