Blackfriars Theatre on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Blackfriars Theatre was the name given to two separate theatres located in the former Blackfriars Dominican

Blackfriars Theatre was the name given to two separate theatres located in the former Blackfriars Dominican

The second Blackfriars was an indoor theatre built elsewhere on the property at the instigation of

The second Blackfriars was an indoor theatre built elsewhere on the property at the instigation of

The

The

During the construction of Shakespeare's Globe, London, in the 1990s, the shell for an indoor theatre was built next door, to house a "

During the construction of Shakespeare's Globe, London, in the 1990s, the shell for an indoor theatre was built next door, to house a "

Blackfriars Theatre

article from The Map of Early Modern London project at The University of Victoria

The Blackfriars Playhouse

in Staunton, Virginia

Shakespeare's Globe and the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse

in London

Digitised Posters and Flyers from the Second BlackFriars Theatre, held by the

Shakespearean Playhouses

', by Joseph Quincy Adams Jr. from

Blackfriars Theatre was the name given to two separate theatres located in the former Blackfriars Dominican

Blackfriars Theatre was the name given to two separate theatres located in the former Blackfriars Dominican priory

A priory is a monastery of men or women under religious vows that is headed by a prior or prioress. Priories may be houses of mendicant friars or nuns (such as the Dominicans, Augustinians, Franciscans, and Carmelites), or monasteries of ...

in the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

. The first theatre began as a venue for the Children of the Chapel Royal, child actors associated with the Queen's chapel choirs

A choir ( ; also known as a chorale or chorus) is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which sp ...

, and who from 1576 to 1584 staged plays in the vast hall of the former monastery. The second theatre dates from the purchase of the upper part of the priory and another building by James Burbage

James Burbage (1530–35 – 2 February 1597) was an English actor, theatre impresario, joiner, and theatre builder in the English Renaissance theatre. He built The Theatre, the first permanent dedicated theatre built in England since Roman t ...

in 1596, which included the Parliament Chamber on the upper floor that was converted into the playhouse. The Children of the Chapel played in the theatre beginning in the autumn of 1600 until the King's Men took over in 1608. They successfully used it as their winter playhouse until all the theatres were closed in 1642 when the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

began. In 1666, the entire area was destroyed in the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past th ...

.

First theatre

Blackfriars Theatre was built on the grounds of the former Dominicanmonastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer whic ...

. The monastery was located between the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

and Ludgate Hill within London proper. The black robes worn by members of this order lent the neighbourhood, and theatres, their name. In the pre-Reformation Tudor years, the site was used not only for religious but also for political functions, such as the annulment trial of Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine, ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was Queen of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 11 June 1509 until their annulment on 23 May 1533. She was previously ...

and Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

which, some eight decades later, would be reenacted in the same room by Shakespeare's company. After Henry's expropriation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to p ...

of monastic property, the monastery became the property of the crown; control of the property was granted to Sir Thomas Cawarden, Master of the Revels. Cawarden used part of the monastery as Revels offices; other parts he sold or leased to the neighbourhood's wealthy residents, including Lord Cobham and John Cheke

Sir John Cheke (or Cheek) (16 June 1514 – 13 September 1557) was an English classical scholar and statesman. One of the foremost teachers of his age, and the first Regius Professor of Greek at the University of Cambridge, he played a great ...

. After Cawarden's death in 1559, the property was sold by Lady Cawarden to Sir William More. In 1576, Richard Farrant

Richard Farrant (c. 1525 – 30 November 1580) was an English composer, musical dramatist, theater founder, and Master of the Children of the Chapel Royal. The first acknowledgment of him is in a list of the Gentlemen of the Chapel Royal in 1 ...

, then Master of Windsor Chapel leased part of the former buttery from More in order to stage plays. As often in the theatrical practice of the time, this commercial enterprise was justified by the convenient fiction of royal necessity; Farrant claimed to need the space for his child choristers to practice plays for the Queen, but he also staged plays for paying audiences. The theatre was small, perhaps long and wide, and admission, compared to public theatres, expensive (apparently four pence); both these factors limited attendance at the theatre to a fairly select group of well-to-do gentry and nobles.

For his playing company, Farrant combined his Windsor children with the Children of the Chapel Royal

The Chapel Royal is an establishment in the Royal Household serving the spiritual needs of the sovereign and the British Royal Family. Historically it was a body of priests and singers that travelled with the monarch. The term is now also appl ...

, then directed by William Hunnis. On Farrant's death in 1580, Hunnis took on John Newman as a partner and they subleased the property from Farrant's widow, putting up a £100 bond on the promise to promptly pay the rent and to make needed repairs. But the venture did not go well financially, which put Farrant's widow in jeopardy of defaulting on the rent to More. In November 1583, Farrant brought suit against Hunnis and Newman for default on the bond. To escape a suit by her or More, Hunnis and Newman transferred their sublease to Henry Evans, a Welsh scrivener

A scrivener (or scribe) was a person who could read and write or who wrote letters to court and legal documents. Scriveners were people who made their living by writing or copying written material. This usually indicated secretarial and ad ...

and theatrical affectionado. This unauthorised assignment of the sublease gave More an excuse to bring suit to retake possession of the property, but Evans used legal delays and finally escaped legal action by selling the sublease to Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (; 12 April 155024 June 1604) was an English peer and courtier of the Elizabethan era. Oxford was heir to the second oldest earldom in the kingdom, a court favourite for a time, a sought-after patron o ...

, sometime after Michaelmas Term (November) of 1583, who then gave it to his secretary, the writer John Lyly.

As proprietor of the playhouse, Lyly installed Evans as the manager of the new company of Oxford's Boys The Earl of Oxford’s Men, alternatively Oxford’s Players, were acting companies in late England in the Middle Ages, Medieval and English Renaissance, Renaissance England patronised by the Earls of Oxford. The name was also sometimes used to refe ...

, composed of the Children of the Chapel and the Children of Paul's, and turned his talents to play writing. Lyly's ''Campaspe'' was performed at BlackfriarsBond, III, p. 310. and subsequently at Court on New Year's Day 1584; likewise, his ''Sapho and Phao

''Sapho and Phao'' is an Elizabethan era stage play, a comedy written by John Lyly. One of Lyly's earliest dramas, it was likely the first that the playwright devoted to the allegorical idealisation of Queen Elizabeth I that became the predomina ...

'' was produced first at Blackfriars on Shrove Tuesday and then at court on 3 March, with Lyly listed as the payee for both Court appearances. In November 1583, Hunnis, still Master of the Chapel Children, successfully petitioned the Queen to increase the stipend to house, feed, and clothe the company. More finally obtained a legal judgement voiding the original lease at the end of Easter Term (June) of 1584, thereby ending the First Blackfriars Playhouse after eight years and postponing the performance of Lyly's third play, '' Gallathea''.

Second theatre

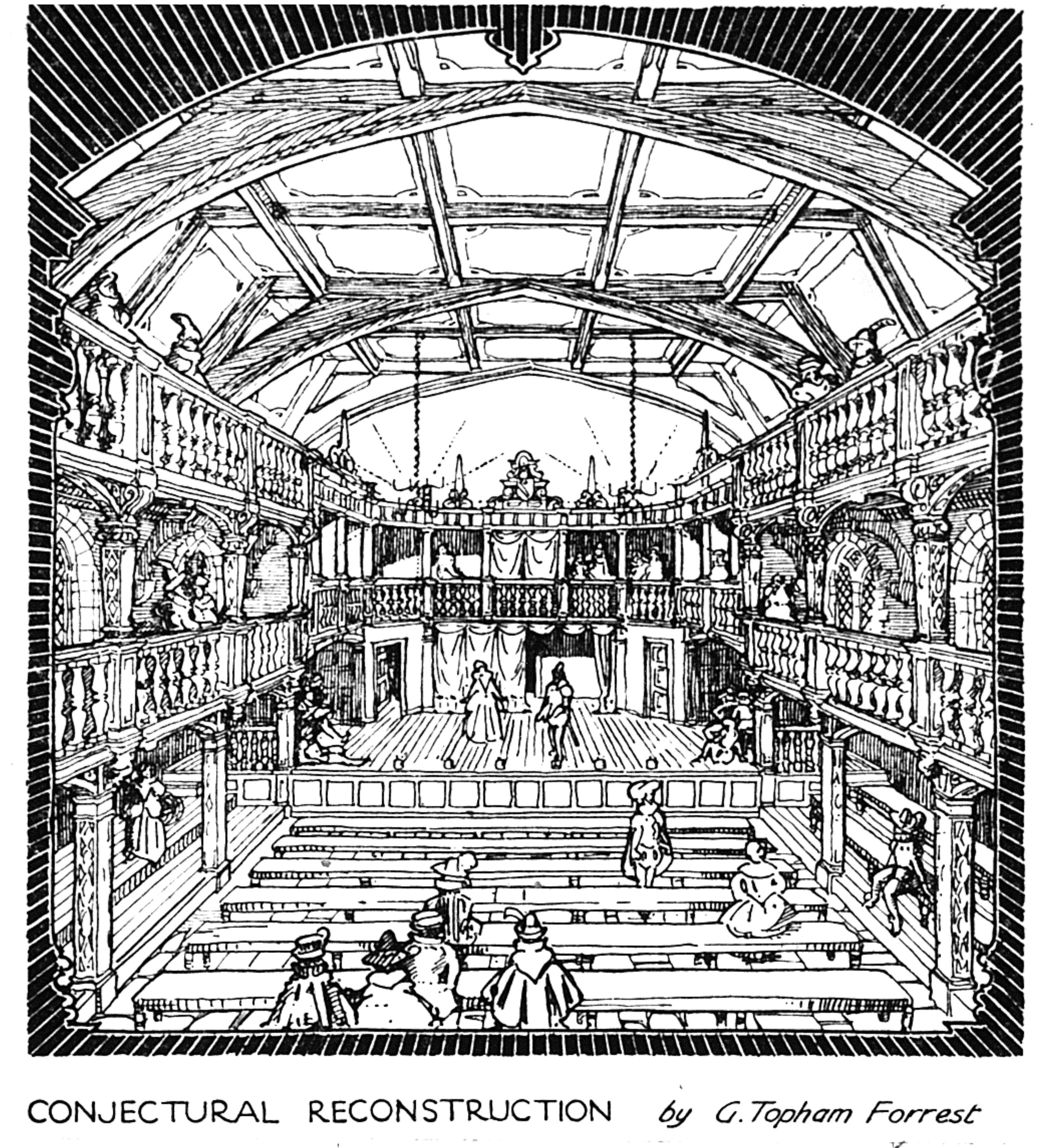

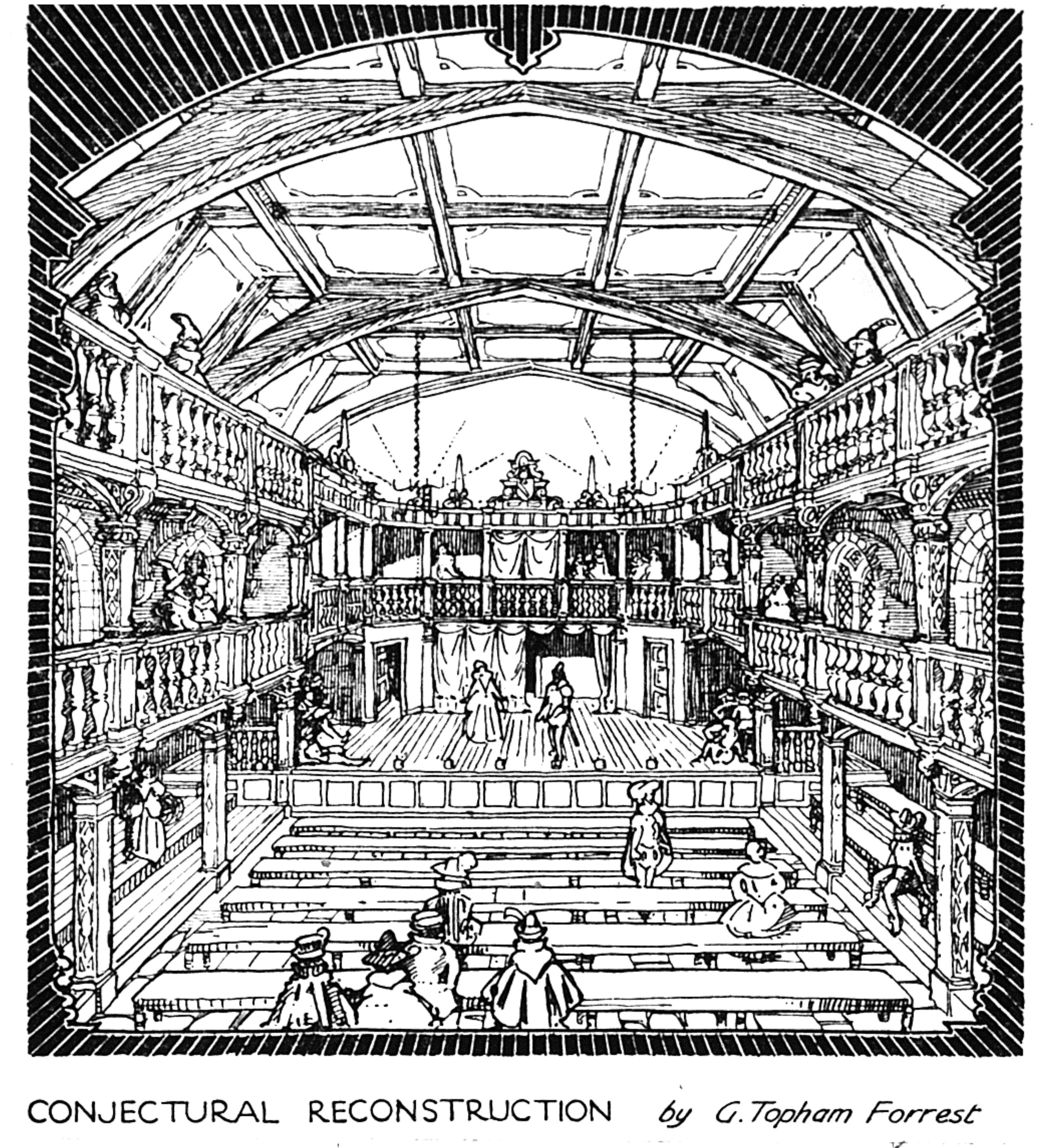

The second Blackfriars was an indoor theatre built elsewhere on the property at the instigation of

The second Blackfriars was an indoor theatre built elsewhere on the property at the instigation of James Burbage

James Burbage (1530–35 – 2 February 1597) was an English actor, theatre impresario, joiner, and theatre builder in the English Renaissance theatre. He built The Theatre, the first permanent dedicated theatre built in England since Roman t ...

, father of Richard Burbage, and impresario of the Lord Chamberlain's Men. In 1596, Burbage purchased, for £600, the frater

Frater is the Latin word for brother.

*In Roman Catholicism, a monk who is not a priest

Frater may also refer to:

People Surname

* Alexander Frater (1937–2020), New Hebrides travel writer and journalist

* Anne Frater, Scottish poet from Bayb ...

of the former priory and rooms below. This large space, perhaps long and 50 wide (15 metres), with high ceilings allowed Burbage to construct two galleries, substantially increasing potential attendance. The nature of Burbage's modifications to his purchase is not clear, and the many contemporary references to the theatre do not offer a precise picture of its design. Once fitted for playing, the space may have been about long and wide (20 by 14 metres), including tiring areas. There were at least two and possibly three galleries, and perhaps a number of stage boxes adjacent to the stage. Estimates of its capacity have varied from below 600 to almost 1000, depending on the number of galleries and boxes. Perhaps as many as ten spectators would have encumbered the stage.

As Burbage built, however, a petition from the residents of the wealthy neighbourhood persuaded the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

to forbid playing there; the letter was signed even by Lord Hunsdon, patron of Burbage's company, and by Richard Field, the Blackfriars printer and hometown neighbour of William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

. The company was absolutely forbidden to perform there. Three years later, Richard Burbage was able to lease the property to Henry Evans, who had been among those ejected more than fifteen years earlier. Evans entered a partnership with Nathaniel Giles, Hunnis's successor at the Chapel Royal. They used the theatre for a commercial enterprise with a group called the Children of the Chapel

The Children of the Chapel are the boys with unbroken voices, choristers, who form part of the Chapel Royal, the body of singers and priests serving the spiritual needs of their sovereign wherever they were called upon to do so. They were overseen ...

, which combined the choristers of the chapel with other boys, many taken up from local grammar schools under colour of Giles's warrant to provide entertainment for the Queen. The dubious legality of these dramatic impressment

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is the taking of men into a military or naval force by compulsion, with or without notice. European navies of several nations used forced recruitment by various means. The large size of ...

s led to a challenge from a father in 1600; however, this method brought the company some of its most famous actors, including Nathaniel Field and Salmon Pavy. The residents did not protest at this use, probably because of perceived social differences between the adult and child companies.

While it housed this company, Blackfriars was the site of an explosion of innovative drama and staging. Together with its competitor, Paul's Children, the Blackfriars company produced plays by a number of the most talented young dramatists of Jacobean literature, among them Thomas Middleton

Thomas Middleton (baptised 18 April 1580 – July 1627; also spelt ''Midleton'') was an English Jacobean playwright and poet. He, with John Fletcher and Ben Jonson, was among the most successful and prolific of playwrights at work in the Jac ...

, Ben Jonson

Benjamin "Ben" Jonson (c. 11 June 1572 – c. 16 August 1637) was an English playwright and poet. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for t ...

, George Chapman, and John Marston. Chapman and Jonson wrote almost exclusively for Blackfriars in this period, while Marston began with Paul's but switched to Blackfriars, in which he appears to have been a sharer, by around 1605. In the latter half of the decade, the company at Blackfriars premiered plays by Francis Beaumont

Francis Beaumont ( ; 1584 – 6 March 1616) was a dramatist in the English Renaissance theatre, most famous for his collaborations with John Fletcher.

Beaumont's life

Beaumont was the son of Sir Francis Beaumont of Grace Dieu, near Thr ...

('' The Knight of the Burning Pestle'') and John Fletcher (''The Faithful Shepherdess

''The Faithful Shepherdess'' is a Jacobean era stage play, the work that inaugurated the playwriting career of John Fletcher. Though the initial production was a failure with its audience, the printed text that followed proved significant, in t ...

'') that, although failures in their first production, marked the first significant appearance of these two dramatists, whose work would profoundly affect early Stuart drama. The new plays of all these playwrights deliberately pushed the accepted boundaries of personal and social satire, of violence on stage, and of sexual frankness. These plays appear to have attracted members of a higher social class than was the norm at the Bankside

Bankside is an area of London, England, within the London Borough of Southwark. Bankside is located on the southern bank of the River Thames, east of Charing Cross, running from a little west of Blackfriars Bridge to just a short distance be ...

and Shoreditch

Shoreditch is a district in the East End of London in England, and forms the southern part of the London Borough of Hackney. Neighbouring parts of Tower Hamlets are also perceived as part of the area.

In the 16th century, Shoreditch was an imp ...

theatres, and the admission price ( sixpence for a cheap seat) probably excluded the poorer patrons of the amphitheatres. Prefaces and internal references speak of gallants and Inns of Court men, who came not only to see a play but also, of course, to be seen; the private theatres sold seats on the stage itself.

The Blackfriars playhouse was also the source of other innovations which would profoundly change the nature of English commercial staging: it was among the first commercial theatrical enterprises to rely on artificial lighting, and it featured music between acts, a practice which the induction to Marston's '' The Malcontent'' (1604) indicates was not common in the public theatres at that time.

In the years around the turn of the century, the children's companies were something of a phenomenon; a reference in ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

'' to "little eyasses" suggests that even the adult companies felt threatened by them. By the later half of that decade, the fashion had changed somewhat. In 1608, Burbage's company (by this time, the King's Men) took possession of the theatre, which they still owned, this time without objections from the neighbourhood. There were originally seven sharers in the reorganised theatre: Richard Burbage, William Shakespeare, Henry Condell

Henry Condell ( bapt. 5 September 1576 – December 1627) was a British actor in the King's Men, the playing company for which William Shakespeare wrote. With John Heminges, he was instrumental in preparing and editing the First Folio, the c ...

, John Heminges, and William Sly, all members of the King's Men, plus Cuthbert Burbage and Thomas Evans, agent for the theatre manager Henry Evans. This arrangement of shareholders (or "housekeepers) was similar to how the Globe Theatre

The Globe Theatre was a theatre in London associated with William Shakespeare. It was built in 1599 by Shakespeare's playing company, the Lord Chamberlain's Men, on land owned by Thomas Brend and inherited by his son, Nicholas Brend, and ...

was operated. Sly, however, died soon after the arrangement was made, and his share was divided among the other six.

After renovations, the King's Men began using the theatre for performances in 1609. Thereafter the King's Men played in Blackfriars for the seven months in winter, and at the Globe during the summer. Blackfriars appears to have brought in a little over twice the revenue of the Globe; the shareholders could earn as much as £13 from a single performance, apart from what went to the actors.

In the reign of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, even Queen Henrietta Maria

Henrietta Maria (french: link=no, Henriette Marie; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland from her marriage to King Charles I on 13 June 1625 until Charles was executed on 30 January 1649. She wa ...

was in the Blackfriars audience. On 13 May 1634 she and her attendants saw a play by Philip Massinger; in late 1635 or early 1636 they saw Lodowick Carlell

Lodowick Carlell (1602–1675), also Carliell or Carlile, was a seventeenth-century English playwright, was active mainly during the Caroline era and the Commonwealth period.

Courtier

Carlell's ancestry was Scottish. He was the son of Herbert ...

's ''Arviragus and Philicia, part 2;'' and they attended a third performance in May 1636.

The theatre closed at the onset of the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

, and was demolished on 6 August 1655.

Reconstructions

Blackfriars Playhouse

The

The American Shakespeare Center

The American Shakespeare Center (ASC) is a regional theatre company located in Staunton, Virginia, that focuses on the plays of William Shakespeare; his contemporaries Ben Jonson, Beaumont and Fletcher, Christopher Marlowe; and works relate ...

's Blackfriars Playhouse

The American Shakespeare Center (ASC) is a regional theatre company located in Staunton, Virginia, that focuses on the plays of William Shakespeare; his contemporaries Ben Jonson, Beaumont and Fletcher, Christopher Marlowe; and works related t ...

in Staunton, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

, is a re-creation of a Jacobean theatre based on what is known of the original Blackfriars. Completed at a cost of $3.7 million, the 300-seat theatre opened in September 2001. Architect Tom McLaughlin based the design on plans for other 17th-century theatres, his own trips to England to view surviving halls of the period, Shakespeare's stage directions and other research and consultation. The lighting imitates that of the original Blackfriars.

Sam Wanamaker Playhouse

During the construction of Shakespeare's Globe, London, in the 1990s, the shell for an indoor theatre was built next door, to house a "

During the construction of Shakespeare's Globe, London, in the 1990s, the shell for an indoor theatre was built next door, to house a "simulacrum

A simulacrum ( plural: simulacra or simulacrums, from Latin '' simulacrum'', which means "likeness, semblance") is a representation or imitation of a person or thing. The word was first recorded in the English language in the late 16th century, ...

" of the Blackfriars Theatre. As no reliable plans of the Blackfriars are known, the plan for the new theatre was based on drawings found in the 1960s at Worcester College, Oxford, at first thought to date from the early 17th century, and to be the work of Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (; 15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was the first significant architect in England and Wales in the early modern period, and the first to employ Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmetry in his buildings.

As the most notable archit ...

. The shell was built to accommodate a theatre as specified by the drawings, and the planned name was the Inigo Jones Theatre. In 2005, the drawings were dated to 1660 and attributed to John Webb. They nevertheless represent the earliest known plan for an English theatre, and are thought to approximate the layout of the Blackfriars Theatre. Some features believed to be typical of earlier in the 17th century were added to the new theatre's design.

Completed at a cost of £7.5 million, the theatre opened as the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse in January 2014. Designed by Jon Greenfield, in collaboration with Allies and Morrison, it is an oak structure built inside the building's brick shell. The thrust stage is surmounted by a musicians' gallery, and the theatre has an ornately painted ceiling. The seating capacity is 340, with benches in a pit and two horse-shoe galleries, placing the audience close to the actors. Shutters around the first gallery admit artificial daylight. When the shutters are closed, lighting is provided by beeswax

Beeswax (''cera alba'') is a natural wax produced by honey bees of the genus ''Apis''. The wax is formed into scales by eight wax-producing glands in the abdominal segments of worker bees, which discard it in or at the hive. The hive work ...

candles mounted in sconces, as well as on six height-adjustable chandelier

A chandelier (; also known as girandole, candelabra lamp, or least commonly suspended lights) is a branched ornamental light fixture designed to be mounted on ceilings or walls. Chandeliers are often ornate, and normally use incandescent ...

s and even held by the actors.

See also

*Mermaid Theatre

The Mermaid Theatre was a theatre encompassing the site of Puddle Dock and Curriers' Alley at Blackfriars in the City of London, and the first built in the City since the time of Shakespeare. It was, importantly, also one of the first new th ...

(1959), a modern theatre built on, or near the original site

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Blackfriars Theatre

article from The Map of Early Modern London project at The University of Victoria

The Blackfriars Playhouse

in Staunton, Virginia

Shakespeare's Globe and the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse

in London

Digitised Posters and Flyers from the Second BlackFriars Theatre, held by the

University of East London

, mottoeng = Knowledge and the fulfilment of vows

, established = 1898 – West Ham Technical Institute1952 – West Ham College of Technology1970 – North East London Polytechnic1989 – Polytechnic of East London ...

*Shakespearean Playhouses

', by Joseph Quincy Adams Jr. from

Project Gutenberg

Project Gutenberg (PG) is a volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, as well as to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks."

It was founded in 1971 by American writer Michael S. Hart and is the oldest digital libr ...

{{Authority control

Former buildings and structures in the City of London

Former theatres in London

1596 establishments in England

1655 disestablishments

1650s disestablishments in England

17th century in London

Theatres completed in 1576

Theatres completed in 1596

Theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perfor ...