Black Seminole on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Black Seminoles, or Afro-Seminoles are Native American-Africans associated with the

Not all the slaves escaping south found military service in St. Augustine to their liking. More escaped slaves sought refuge in wilderness areas in northern Florida, where their knowledge of tropical agriculture—and resistance to tropical diseases—served them well. Most of the black people who pioneered Florida were

Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

people in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

and Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a state in the South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the north, Missouri on the northeast, Arkansas on the east, New ...

. They are mostly blood descendants of the Seminole people, free Africans, and escaped slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, who allied with Seminole groups in Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida ( es, La Florida) was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, ...

. Many have Seminole lineage, but due to the stigma of having very dark or brown skin and kinky hair, they all have been categorized as slaves or freedmen.

Historically, the Black Seminoles lived mostly in distinct bands near the Native American Seminole. Some were held as slaves, particularly of Seminole leaders, but the Black Seminole had more freedom than did slaves held by whites in the South and by other Native American tribes, including the right to bear arms.

Today, Black Seminole descendants live primarily in rural communities around the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma

The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma is a federally recognized Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. It is the largest of the three federally recognized Seminole governments, which include the Seminole Tribe of Florida and the M ...

. Its two Freedmen's bands, the Caesar Bruner Band and the Dosar Barkus Band, are represented on the General Council of the Nation. Other centers are in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the a ...

, and northern Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

.

Since the 1930s, the Seminole Freedmen have struggled with cycles of exclusion from the Seminole Tribe of Oklahoma. In 1990, the tribe received the majority of a $46 million judgement trust by the United States, for seizure of lands in Florida in 1823, and the Freedmen have worked to gain a share of it. In 2004 the US Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point of ...

ruled the Seminole Freedmen could not bring suit without the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, which refused to join them on the claim issue. In 2000 the Seminole Nation voted to restrict membership to those who could prove descent from a Seminole on the Dawes Rolls

The Dawes Rolls (or Final Rolls of Citizens and Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes, or Dawes Commission of Final Rolls) were created by the United States Dawes Commission. The commission was authorized by United States Congress in 1893 to exe ...

of the early 20th century, which excluded about 1,200 Freedmen who were previously included as members. They argue that the Dawes Rolls were inaccurate and often classified persons with both Seminole and African ancestry as only Freedmen.

Origins

The Spanish strategy for defending their claim of Florida at first was based on forcing the local Indian tribes into amission

Mission (from Latin ''missio'' "the act of sending out") may refer to:

Organised activities Religion

*Christian mission, an organized effort to spread Christianity

*Mission (LDS Church), an administrative area of The Church of Jesus Christ of ...

system. The Native Americans in the missions were to serve as a militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

to protect the colony from incursions from the neighboring colony of South Carolina

Province of South Carolina, originally known as Clarendon Province, was a province of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712 to 1776. It was one of the five Southern colonies and one of the thirteen American colonies. The monar ...

. However, due to a combination of raids by South Carolinan colonists and newly introduced European disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism, and that is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that a ...

s to which the Indians had no immunity, Florida's native population was quickly decimated. After the local Native Americans had all but died out, Spanish authorities encouraged Native Americans and runaway slaves from the Southern colonies to move to their territory. The Spanish hoped that the increased number of inhabitants of Spanish Florida would be effective in case of potential raids by American colonists.

As early as 1689, enslaved Africans fled from the South Carolina Lowcountry

The Lowcountry (sometimes Low Country or just low country) is a geographic and cultural region along South Carolina's coast, including the Sea Islands. The region includes significant salt marshes and other coastal waterways, making it an impor ...

to Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida ( es, La Florida) was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, ...

seeking freedom. These were people who gradually formed what has become known as the Gullah

The Gullah () are an African American ethnic group who predominantly live in the Lowcountry region of the U.S. states of Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, and North Carolina, within the coastal plain and the Sea Islands. Their language and cultu ...

culture of the coastal Southeast.

Under an edict from King Charles II of Spain

Charles II of Spain (''Spanish: Carlos II,'' 6 November 1661 – 1 November 1700), known as the Bewitched (''Spanish: El Hechizado''), was the last Habsburg ruler of the Spanish Empire. Best remembered for his physical disabilities and the War of ...

in 1693, the black fugitives received liberty in exchange for defending the Spanish settlers at St. Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

. The Spanish organized the black volunteers into a militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

; their settlement at Fort Mosé, founded in 1738, was the first legally sanctioned free black town in North America.Landers ''Black Society in Spanish Florida'', p. 25, citing Royal Decree of Charles II.Not all the slaves escaping south found military service in St. Augustine to their liking. More escaped slaves sought refuge in wilderness areas in northern Florida, where their knowledge of tropical agriculture—and resistance to tropical diseases—served them well. Most of the black people who pioneered Florida were

Gullah

The Gullah () are an African American ethnic group who predominantly live in the Lowcountry region of the U.S. states of Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, and North Carolina, within the coastal plain and the Sea Islands. Their language and cultu ...

people who escaped from the rice plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

of South Carolina (and later Georgia). As Gullah, they had developed an Afro-English based Creole, along with cultural practices and African leadership structure. The Gullah pioneers built their own settlements based on rice and corn agriculture. They became allies of Creek and other Native Americans escaping into Florida from the Southeast at the same time. In Florida, they developed the Afro-Seminole Creole

__NOTOC__

Afro-Seminole Creole (ASC) is a dialect of Gullah spoken by Black Seminoles in scattered communities in Oklahoma, Texas, and Northern Mexico.

, which they spoke with the growing Seminole tribe.

Following the Treaty of Paris signed in 1763 at the conclusion of the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

, Spanish Florida was ceded to the Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, wh ...

. The area remained a sanctuary for fugitive slaves from the Southern colonies, as it was lightly settled. Many slaves sought refuge near growing Native American settlements.

In 1773, when the American naturalist William Bartram

William Bartram (April 20, 1739 – July 22, 1823) was an American botanist, ornithologist, natural historian and explorer. Bartram was the author of an acclaimed book, now known by the shortened title '' Bartram's Travels'', which chronicled ...

visited the area, he referred to the Seminole as a distinct people, their name apparently coming from the word "simanó-li", which according to John Reed Swanton, "is applied by the Creeks to people who remove from populous towns and live by themselves.". William C. Sturtevant says the ethnonym

An ethnonym () is a name applied to a given ethnic group. Ethnonyms can be divided into two categories: exonyms (whose name of the ethnic group has been created by another group of people) and autonyms, or endonyms (whose name is created and us ...

was borrowed by Muskogee from the Spanish word ''cimarrón'', supposedly the source as well of the English word ''maroon

Maroon ( US/ UK , Australia ) is a brownish crimson color that takes its name from the French word ''marron'', or chestnut. "Marron" is also one of the French translations for "brown".

According to multiple dictionaries, there are vari ...

'' used to describe the runaway slave communities of Florida and of the Great Dismal Swamp

The Great Dismal Swamp is a large swamp in the Coastal Plain Region of southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina, between Norfolk, Virginia, and Elizabeth City, North Carolina. It is located in parts of the southern Virginia indepe ...

on the border of Virginia and North Carolina, on colonial islands of the Caribbean, and other parts of the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

. Linguist Leo Spitzer, however, writing in the journal ''Language'', says, "If there is a connection between Eng. ''maroon'', Fr. ''marron'', and Sp. ''cimarron'', Spain (or Spanish America) probably gave the word directly to England (or English America)."

Florida had been a refuge for fugitive slaves for at least 70 years by the time of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

. Communities of black Seminoles were established on the outskirts of major Seminole towns. A new influx of freedom-seeking black people reached Florida during the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

(1775–83), escaping during the disruption of war. During the Revolution, the Seminole allied with the British, and African Americans and Seminole came into increased contact with each other. The Seminole held some slaves, as did the Creek and other Southeast Native American tribes. During the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

, members of both communities sided with the British against the US in the hopes of repelling American settlers; they strengthened their internal ties and earned the enmity of American general Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

.Wright ''Creeks and Seminoles'' 85–91.

Spain had given land to some Muscogee (Creek)

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsNative Americans, such as the

The black Seminole culture that took shape after 1800 was a dynamic mixture of African, Native American, Spanish, and slave traditions. Adopting certain practices of the Native Americans, maroons wore Seminole clothing and ate the same foodstuffs prepared the same way: they gathered the roots of a native plant called ''

The black Seminole culture that took shape after 1800 was a dynamic mixture of African, Native American, Spanish, and slave traditions. Adopting certain practices of the Native Americans, maroons wore Seminole clothing and ate the same foodstuffs prepared the same way: they gathered the roots of a native plant called ''

Historians estimate that during the 1820s, 800 blacks were living with the Seminoles. The Black Seminole settlements were highly militarized, unlike the communities of most of the slaves in the Deep South. The military nature of the African and Seminole relationship led General

Historians estimate that during the 1820s, 800 blacks were living with the Seminoles. The Black Seminole settlements were highly militarized, unlike the communities of most of the slaves in the Deep South. The military nature of the African and Seminole relationship led General

Wanting to disrupt Florida's maroon communities after the War of 1812, General

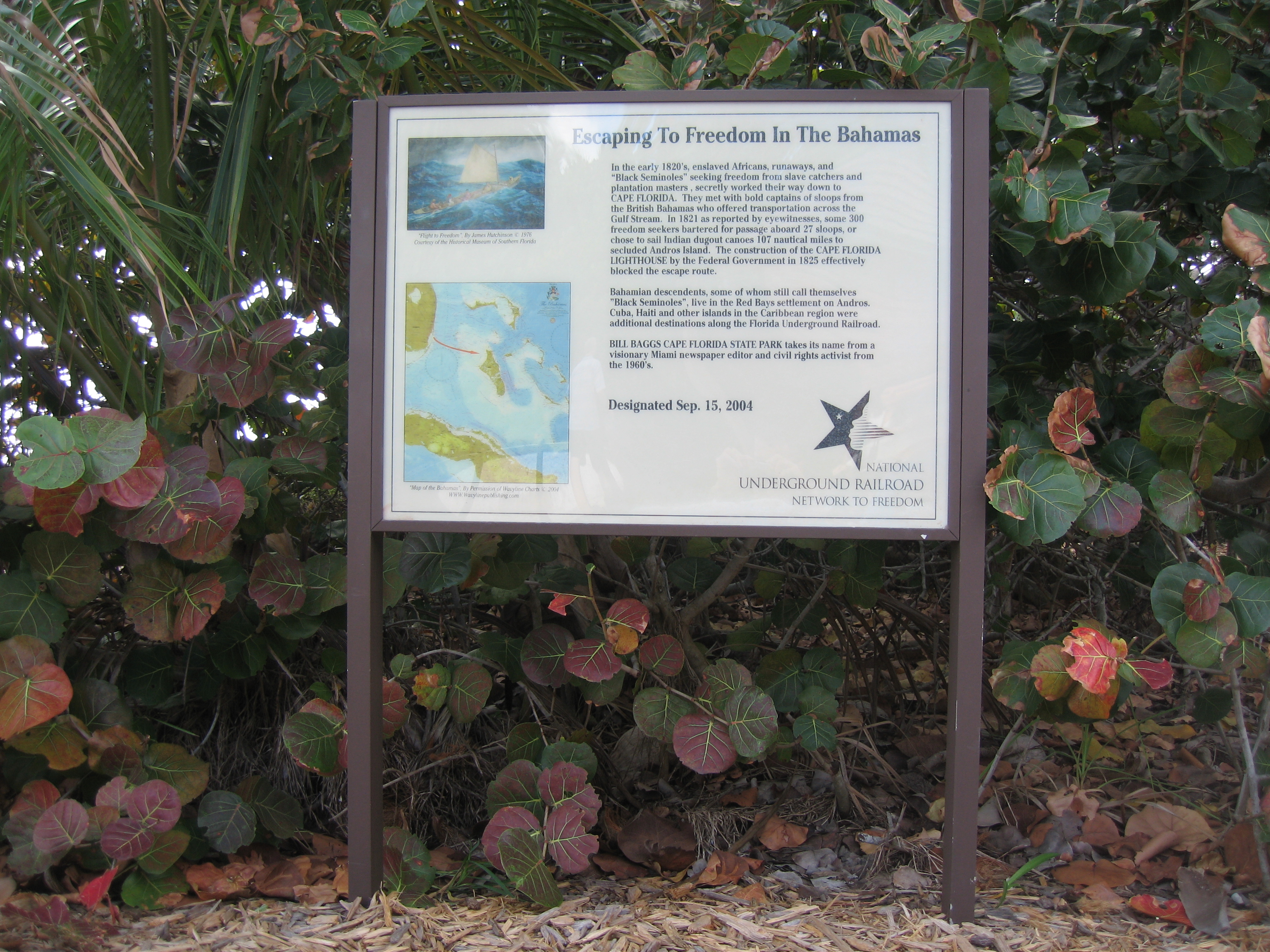

Under pressure, the Native American and black communities moved into south and central Florida. Slaves and black Seminoles frequently migrated down the peninsula to escape from Cape Florida to

''Network to Freedom'', National Park Service, 2010, accessed April 10, 2013. Their concern about living under American rule was not unwarranted. In 1821, Andrew Jackson became the territorial governor of Florida and ordered an attack on The

The

In addition to aiding the natives in their fight, black Seminoles recruited plantation slaves to rebellion at the start of the war. The slaves joined Native Americans and maroons in the destruction of 21 sugar plantations from Christmas Day, December 25, 1835, through the summer of 1836. Historians do not agree on whether these events should be considered a separate

This left hundreds of Seminoles and black Seminoles unable to leave the settlement or to defend themselves against slavers.

After 1861, the black Seminoles in Mexico and Texas had little contact with those in Oklahoma. For the next 20 years, black Seminoles served as militiamen and Native American fighters in Mexico, where they became known as '' mascogos'', derived from the tribal name of the Creek – Muskogee. Slave raiders from Texas continued to threaten the community but arms and reinforcements from the Mexican Army enabled the black warriors to defend their community.Mulroy 56–73, Porter ''Black'' 124–147.

By the 1940s, descendants of the Mascogos numbered 400–500 in Nacimiento de los Negros,

Throughout the period, several hundred black Seminoles remained in the Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Because most of the Seminole and the other

Throughout the period, several hundred black Seminoles remained in the Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Because most of the Seminole and the other

In 1981, descendants at Brackettville and the Little River community of Oklahoma met for the first time in more than a century, in Texas for a

After banning its participation in the

New York University (NYU) Press, 2012, p. 103. In 1833 Britain abolished slavery throughout its Empire. They have been sometimes referred to as "black Indians", in recognition of their history.

''LA Times''/''Washington Post'' News Service, printed in ''Sarasota Herald-Tribune'', October 20, 1978, accessed April 13, 2013. The settlement was in compensation for land taken from them in northern Florida by the United States at the time of the signing of the

''New York Times'', January 29, 2001, April 11, 2013."Race part of Seminole dispute"

, Indianz.com, January 29, 2001, accessed April 11, 2013. In another aspect of the dispute over citizenship, in the summer of 2000 the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma voted to restrict members, according to

''Sequoyah County Times'', November 4, 2003, accessed April 10, 2013. Journalists theorized the decision could affect the similar case in which the

* Fort Mose Historic State Park in Florida is a

* Fort Mose Historic State Park in Florida is a

"Seminole Freedmen rebuffed by Supreme Court"

June 29, 2004.

Kashif, Annette. "Africanisms Upon the Land: A Study of African Influenced Placenames of the USA"

In ''Places of Cultural Memory: African Reflections on the American Landscape''. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 2001. *Landers, Jane. ''Black Society in Spanish Florida''. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999. *Littlefield, Daniel F., Jr. ''Africans and Seminoles''. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1977. *Mahon, John K. ''History of the Second Seminole War, 1835–1842''. 1967. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1985. *Mulroy, Kevin. ''Freedom on the Border: The Seminole Maroons in Florida, the Indian Territory, Coahuila, and Texas''. Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 1993. *Mulroy, Kevin. ''The Seminole Freedmen: A History (Race and Culture in the American West)'', Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007. *Porter, Kenneth Wiggins. ''The Black Seminoles: History of a Freedom-Seeking People''. Eds Thomas Senter and Alcione Amos. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1996. *Porter, Kenneth Wiggins. ''The Negro on the American Frontier''. New York: Arno Press, 1971. *Rivers, Larry Eugene. ''Slavery in Florida''. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000. *Schneider, Pamela S. ''It's Not Funny: Various Aspects of Black History'' Charlotte PA: Lemieux Press Publishers, 2005.

Simmons, William. ''Notices of East Florida: with an account of the Seminole nation of Indians''

1822. Intro. George E. Buker. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1973, available online. *Sturtevant, William C. "Creek into Seminole." ''North American Indians in Historical Perspective''. Eds Eleanor B. Leacock and Nancy O. Lurie. New York: Random House, 1971. *Twyman, Bruce Edward. ''The Black Seminole Legacy and Northern American Politics, 1693–1845''. Washington: Howard University Press, 1999. *Wallace, Ernest. ''Ranald S. Mackenzie on the Texas Frontier''. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1993. *Wright, J. Leitch, Jr. ''Creeks and Seminoles: The Destruction and Regeneration of the Muscogulge People''. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986.

Littlefield, Daniel C. ''Rice and Slaves: Ethnicity and the Slave Trade in Colonial South Carolina''

Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981/1991, University of Illinois Press.

Littlefield, Daniel F. Jr. ''Africans and Seminoles: From Removal to Emancipation''

University of Mississippi Press, 1977. *Opala, Joseph A. ''A Brief History of the Seminole Freedmen'', Austin: University of Texas African and Afro-American Studies and Research Center, Series 2, No. 3, 1980. *——— "Seminole-African Relations on the Florida Frontier", ''Papers in Anthropology'' (University of Oklahoma), 22 (1) (1981), 11–52.

''Rebellion: John Horse and the black Seminoles'' Website

c. 1958, Seminole Nation of Oklahoma website

Freepages GenWeb

''Wired Magazine'', Vol. 13.09, August 2005, article on DNA, ethnicity, and black Seminoles

"black Indians"

ColorQWorld

Pilaklikaha

a

History of Central Florida Podcast"Tragedy and Survival: Virtual Landscapes of 19th Century Florida Gulf Coast Maroons"

{{African American topics African–Native American relations Gullah Seminole Wars Fugitive American slaves

Miccosukee

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the U.S. state of Florida. They were part of the Seminole nation until the mid-20th century, when they organized as an independent tribe, receiving f ...

, Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

, and the Apalachicola, and formed communities. Their community evolved over the late 18th and early 19th centuries as waves of Creek left present-day Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

and Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

under pressure from white settlement and the Creek Wars

The Creek War (1813–1814), also known as the Red Stick War and the Creek Civil War, was a regional war between opposing Indigenous American Creek factions, European empires and the United States, taking place largely in modern-day Alabama ...

.

By a process of ethnogenesis

Ethnogenesis (; ) is "the formation and development of an ethnic group".

This can originate by group self-identification or by outside identification.

The term ''ethnogenesis'' was originally a mid-19th century neologism that was later introd ...

, the Native Americans formed the Seminole.

Culture

The black Seminole culture that took shape after 1800 was a dynamic mixture of African, Native American, Spanish, and slave traditions. Adopting certain practices of the Native Americans, maroons wore Seminole clothing and ate the same foodstuffs prepared the same way: they gathered the roots of a native plant called ''

The black Seminole culture that took shape after 1800 was a dynamic mixture of African, Native American, Spanish, and slave traditions. Adopting certain practices of the Native Americans, maroons wore Seminole clothing and ate the same foodstuffs prepared the same way: they gathered the roots of a native plant called ''coontie

''Zamia integrifolia'', also known as coontie palm is a small, tough, woody cycad native to the southeastern United States (in Florida and Georgia), the Bahamas, Cuba, and the Cayman Islands.

Description

''Zamia integrifolia'' produces reddish ...

'', grinding, soaking, and straining them to make a starchy flour similar to arrowroot

Arrowroot is a starch obtained from the rhizomes (rootstock) of several tropical plants, traditionally ''Maranta arundinacea'', but also Florida arrowroot from ''Zamia integrifolia'', and tapioca from cassava (''Manihot esculenta''), which is oft ...

, as well as mashing corn with a mortar and pestle to make ''sofkee'', a sort of porridge often used as a beverage, with water added— ashes from the fire wood used to cook the sofkee were occasionally added to it for extra flavor. They also introduced their Gullah staple of rice to the Seminole, and continued to use it as a basic part of their diets. Rice remained part of the diet of the black Seminoles who moved to Oklahoma. In addition, the language of the black Seminoles is a mix of African, Seminole, and Spanish words. The African heritage of the black Seminoles, according to academics, is from the Kongo, Yoruba

The Yoruba people (, , ) are a West African ethnic group that mainly inhabit parts of Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. The areas of these countries primarily inhabited by Yoruba are often collectively referred to as Yorubaland. The Yoruba constitute ...

, and other African ethnic groups. African American linguist and historian, Lorenzo Dow Turner documented about fifteen words spoken by black Seminoles that came from the Kikongo language. Other African words spoken by black Seminoles are from the Twi, Wolof, and other West African languages.

Initially living apart from the Native Americans, the maroons developed their own unique African-American culture, based in the Gullah culture of the Lowcountry. black Seminoles inclined toward a syncretic

Syncretism () is the practice of combining different beliefs and various schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the theology and mythology of religion, thu ...

form of Christianity developed during the plantation years. Certain cultural practices, such as "jumping the broom

''Jumping the Broom'' is a 2011 American romantic comedy-drama film directed by Salim Akil and produced by Tracey E. Edmonds, Elizabeth Hunter, T.D. Jakes, Glendon Palmer, and Curtis Wallace.

The title of the film is derived from the Black ...

" to celebrate marriage, hailed from the plantations; other customs, such as some names used for black towns, reflected African heritage.

As time progressed, the Seminole and blacks had limited intermarriage, but historians and anthropologists have come to believe that generally the black Seminoles had independent communities. They allied with the Seminole at times of war.

The Seminole society was based on a matrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's lineage – and which can involve the inheritance ...

kinship system, in which inheritance and descent went through the maternal line. Children were considered to belong to the mother's clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, mea ...

, so those born to ethnic African mothers would have been considered black by the Seminole. While the children might integrate customs from both parents' cultures, the Seminole believed they belonged to the mother's group more than the father's. African Americans adopted some elements of the European-American patriarchal system. But, under the South's adoption of the principle of ''partus sequitur ventrem

''Partus sequitur ventrem'' (L. "That which is born follows the womb"; also ''partus'') was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies in the Americas which defined the legal status of children born th ...

'' in the 17th century and incorporated into slavery law in slave states, children of slave mothers were considered legally slaves. Under the Fugitive Slave Law

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of enslaved people who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from ...

of 1850, even if the mother escaped to a free state, she and her children were legally considered slaves and fugitives. As a result, the black Seminoles born to slave mothers were always at risk from slave raiders.

African-Seminole relations

By the early 19th century, maroons (free Black people and runaway slaves) and the Seminole were in regular contact in Florida, where they evolved a system of relations unique among North American Native Americans and Black people. Seminole practice in Florida had acknowledged slavery, though not on the chattel slavery model then common in the American south. It was, in fact, more like feudal dependency and taxation since African Americans among the Seminole generally lived in their own communities. In exchange for paying an annual tribute of livestock, crops, hunting, and war party obligations, Black prisoners or fugitives found sanctuary among the Seminole. Seminoles, in turn, acquired an important strategic ally in a sparsely-populated region. They elected their own leaders, and could amass wealth in cattle and crops. Most importantly, they bore arms for self-defense. Florida real estate records show that the Seminole and Black Seminole people owned large quantities of Florida land. In some cases, a portion of that Florida land is still owned by the Seminole and black Seminole descendants in Florida. In the 19th century, the Black Seminoles were called "SeminoleNegro

In the English language, ''negro'' is a term historically used to denote persons considered to be of Black African heritage. The word ''negro'' means the color black in both Spanish and in Portuguese, where English took it from. The term can be ...

es" by their white American enemies and ''Estelusti'' ("black People"), by their Native American allies.

Under the comparatively free conditions, the Black Seminoles flourished. US Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

Lieutenant George McCall recorded his impressions of a Black Seminole community in 1826:

We found these negroes in possession of large fields of the finest land, producing large crops of corn, beans, melons, pumpkins, and other esculent vegetables.... I saw, while riding along the borders of the ponds, fine rice growing; and in the village large corn-cribs were filled, while the houses were larger and more comfortable than those of the Native Americans themselves.

Historians estimate that during the 1820s, 800 blacks were living with the Seminoles. The Black Seminole settlements were highly militarized, unlike the communities of most of the slaves in the Deep South. The military nature of the African and Seminole relationship led General

Historians estimate that during the 1820s, 800 blacks were living with the Seminoles. The Black Seminole settlements were highly militarized, unlike the communities of most of the slaves in the Deep South. The military nature of the African and Seminole relationship led General Edmund Pendleton Gaines

Edmund Pendleton Gaines (March 20, 1777 – June 6, 1849) was a career United States Army officer who served for nearly fifty years, and attained the rank of major general by brevet. He was one of the Army's senior commanders during its format ...

, who visited several flourishing black Seminole settlements in the 1800s, to describe the African Americans as "vassals and allies" of the Seminole.

The traditional relationship between Seminole Blacks and natives changed in the course of the Second Seminole War when the old tribal system broke down and the Seminole resolved themselves into loose war bands living off the land with no distinction between tribal members and Black fugitives. That changed again in the new territory when the Seminole were obliged to settle on fixed lots of land and take up settled agriculture. Conflict arose in the territory because the transplanted Seminole had been placed on land allocated to the Creek, who had a practice of chattel slavery. There was increasing pressure from both Creek and pro-Creek Seminole for the adoption of the Creek model of slavery for the Black Seminoles. Creek slavers and those from other Native groups, and whites, began raiding the Black Seminole settlements to kidnap and enslave people. The Seminole leadership would become headed by a pro-Creek faction who supported the institution of chattel slavery. These threats led to many Black Seminoles escaping to Mexico.

In terms of spirituality, the ethnic groups remained distinct. The Seminole followed the nativistic principles of their Great Spirit

The Great Spirit is the concept of a life force, a Supreme Being or god known more specifically as Wakan Tanka in Lakota,Ostler, Jeffry. ''The Plains Sioux and U.S. Colonialism from Lewis and Clark to Wounded Knee''. Cambridge University Pres ...

. Black enslaved people had a syncretic form of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global popula ...

brought with them from the plantations. In general, the Black former-slaves never wholly adopted Seminole culture and beliefs but were accepted into Seminole society, as seen by the skin tone in the pictures of the early 1900s. They were not considered Native American by the middle of the 20th century.

Most Black former-slaves spoke Gullah

The Gullah () are an African American ethnic group who predominantly live in the Lowcountry region of the U.S. states of Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, and North Carolina, within the coastal plain and the Sea Islands. Their language and cultu ...

, an Afro-English-based creole language

A creole language, or simply creole, is a stable natural language that develops from the simplifying and mixing of different languages into a new one within a fairly brief period of time: often, a pidgin evolved into a full-fledged language. ...

. That enabled them to communicate better with Anglo-Americans than the Creek or Mikasuki-speaking Seminole. The Native Americans used them as translators to advance their trading with the British and other tribes. Together, in Florida, they developed Afro-Seminole Creole

__NOTOC__

Afro-Seminole Creole (ASC) is a dialect of Gullah spoken by Black Seminoles in scattered communities in Oklahoma, Texas, and Northern Mexico.

, identified in 1978 as a distinct language by the linguist Ian Hancock. Black Seminoles and Freedmen continued to speak Afro-Seminole Creole through the 19th century in Oklahoma. Hancock found that in 1978, some Black Seminole and Seminole elders still spoke it in Oklahoma and in Florida.

Seminole Wars

After winning independence in the Revolution, American slaveholders were increasingly worried about the armed black communities in Florida. The territory was ruled again by Spain, as Britain had ceded bothEast

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fac ...

and West Florida

West Florida ( es, Florida Occidental) was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. As its name suggests, it was formed out of the western part of former S ...

. The US slaveholders sought the capture and return of Florida's black fugitives under the Treaty of New York (1790), the first treaty ratified under the Confederation.Miller ''Treaties and Other International Acts of the United States'' 2: 344, Twyman, ''The Black Seminole Legacy and Northern American Politics'', pp. 78–79.Wanting to disrupt Florida's maroon communities after the War of 1812, General

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

attacked the Negro Fort

Negro Fort (African Fort) was a short-lived fortification built by the British in 1814, during the War of 1812, in a remote part of what was at the time Spanish Florida. It was intended to support a never-realized British attack on the U.S. via ...

, which had become a black Seminole stronghold after the British had allowed them to occupy it when they evacuated Florida. Breaking up the maroon communities was one of Jackson's major objectives in the First Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostiliti ...

(1817–18).United States ''American State Papers: Foreign Affairs'' 4: 559–61, ''Army-Navy Chronicle'' 2: 114–6, Mahon 65–66.Under pressure, the Native American and black communities moved into south and central Florida. Slaves and black Seminoles frequently migrated down the peninsula to escape from Cape Florida to

the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the a ...

. Hundreds left in the early 1820s after the United States acquired the territory from Spain, effective 1821. Contemporary accounts noted a group of 120 migrating in 1821, and a much larger group of 300 African-American slaves escaping in 1823, picked up by Bahamians in 27 sloops and also by canoes."Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park"''Network to Freedom'', National Park Service, 2010, accessed April 10, 2013. Their concern about living under American rule was not unwarranted. In 1821, Andrew Jackson became the territorial governor of Florida and ordered an attack on

Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

, a village built by black Seminoles and other free blacks on the south of Tampa Bay

Tampa Bay is a large natural harbor and shallow estuary connected to the Gulf of Mexico on the west-central coast of Florida, comprising Hillsborough Bay, McKay Bay, Old Tampa Bay, Middle Tampa Bay, and Lower Tampa Bay. The largest freshwater ...

on the Manatee River. Raiders captured over 250 people, most of whom were sold into slavery. Some of the survivors fled to the Florida interior and others to Florida's east coast and escaped to the Bahamas. In the Bahamas, the black Seminoles developed a village known as Red Bays on Andros

Andros ( el, Άνδρος, ) is the northernmost island of the Greek Cyclades archipelago, about southeast of Euboea, and about north of Tinos. It is nearly long, and its greatest breadth is . It is for the most part mountainous, with many ...

, where basket making and certain grave rituals associated with Seminole traditions are still practiced. Federal construction and staffing of the Cape Florida Lighthouse

The Cape Florida Light is a lighthouse on Cape Florida at the south end of Key Biscayne in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Constructed in 1825, it guided mariners off the Florida Reef, which starts near Key Biscayne and extends southward a few miles ...

in 1825 reduced the number of slave escapes from this site.

The

The Second Seminole War

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between the United States and groups collectively known as Seminoles, consisting of Native Americans and Black Indians. It was part of a ser ...

(1835–42) marked the height of tension between the U.S. and the Seminoles, and also the historical peak of the African-Seminole alliance. Under the policy of Indian removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a ...

, the US wanted to relocate Florida's 4,000 Seminole people and most of their 800 black Seminole allies to the western Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

. During the year before the war, prominent white citizens captured and claimed as fugitive slaves at least 100 black Seminoles.

Anticipating attempts to re-enslave more members of their community, black Seminoles opposed removal to the West. In councils before the war, they threw their support behind the most militant Seminole faction, led by Osceola

Osceola (1804 – January 30, 1838, Asi-yahola in Muscogee language, Creek), named Billy Powell at birth in Alabama, became an influential leader of the Seminole people in Florida. His mother was Muscogee, and his great-grandfather was a S ...

. After war broke out, individual black leaders, such as John Caesar, Abraham, and John Horse

John Horse (c. 1812–1882), also known as Juan Caballo, Juan Cavallo, John Cowaya (with spelling variations) and Gopher John, was of mixed ancestry (African and Seminole Indian) who fought alongside the Seminoles in the Second Seminole War in F ...

, played key roles.Mahon 69–134; Porter ''Black'' 25–52.In addition to aiding the natives in their fight, black Seminoles recruited plantation slaves to rebellion at the start of the war. The slaves joined Native Americans and maroons in the destruction of 21 sugar plantations from Christmas Day, December 25, 1835, through the summer of 1836. Historians do not agree on whether these events should be considered a separate

slave rebellion

A slave rebellion is an armed uprising by enslaved people, as a way of fighting for their freedom. Rebellions of enslaved people have occurred in nearly all societies that practice slavery or have practiced slavery in the past. A desire for freed ...

; generally they view the attacks on the sugar plantations as part of the Seminole War.

By 1838, U.S. General Thomas Sydney Jesup tried to divide the black and Seminole warriors by offering freedom to the blacks if they surrendered and agreed to removal to Indian Territory. John Horse

John Horse (c. 1812–1882), also known as Juan Caballo, Juan Cavallo, John Cowaya (with spelling variations) and Gopher John, was of mixed ancestry (African and Seminole Indian) who fought alongside the Seminoles in the Second Seminole War in F ...

was among the black warriors who surrendered under this condition. Due to Seminole opposition, however, the Army did not fully follow through on its offer. After 1838, more than 500 black Seminoles traveled with the Seminoles thousands of miles to the Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

in present-day Oklahoma; some traveled by ship across the Gulf of Mexico and up the Mississippi River. Because of harsh conditions, many of both peoples died along this trail from Florida to Oklahoma, also known as '' The Trail of Tears''.

The status of black Seminoles and fugitive slaves was largely unsettled after they reached Indian Territory. The issue was compounded by the government's initially putting the Seminole and blacks under the administration of the Creek Nation

The Muscogee Nation, or Muscogee (Creek) Nation, is a federally recognized Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The nation descends from the historic Muscogee Confederacy, a large group of indigenous peoples of the South ...

, many of whom were slaveholders. The Creek tried to re-enslave some of the fugitive black slaves. John Horse and others set up towns, generally near Seminole settlements, repeating their pattern from Florida.

In the West and Mexico

In the west, the black Seminoles were still threatened by slave raiders. These included pro-slavery members of the Creek tribe and some Seminole, whose allegiance to the blacks diminished after defeat by the US in the war. Officers of the federal army may have tried to protect the black Seminoles, but in 1848 the U.S. Attorney General bowed to pro-slavery lobbyists and ordered the army to disarm the community.Porter ''Black'' 97, 111–123, United States Attorney General ''Official Opinions'' 4: 720–29, Giddings ''Exiles of Florida'' 327–28, Foreman ''The Five Civilized Tribes'' 257, Littlefield ''Africans and Seminoles'' 122–25.This left hundreds of Seminoles and black Seminoles unable to leave the settlement or to defend themselves against slavers.

Migration to Mexico

Facing the threat of enslavement, the black Seminole leaderJohn Horse

John Horse (c. 1812–1882), also known as Juan Caballo, Juan Cavallo, John Cowaya (with spelling variations) and Gopher John, was of mixed ancestry (African and Seminole Indian) who fought alongside the Seminoles in the Second Seminole War in F ...

and about 180 black Seminoles staged a mass escape in 1849 to northern Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

, where slavery had been abolished twenty years earlier. The black fugitives crossed to freedom in July 1850. They rode with a faction of traditionalist Seminole under the chief ''Coacochee'', who led the expedition. The Mexican government welcomed the Seminole allies as border guards on the frontier, and they settled at Nacimiento, Coahuila

Coahuila (), formally Coahuila de Zaragoza (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Coahuila de Zaragoza ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Coahuila de Zaragoza), is one of the 32 states of Mexico.

Coahuila borders the Mexican states of N ...

.Foster 42–43; Mulroy 58; Porter, ''Black'', 130–31.After 1861, the black Seminoles in Mexico and Texas had little contact with those in Oklahoma. For the next 20 years, black Seminoles served as militiamen and Native American fighters in Mexico, where they became known as '' mascogos'', derived from the tribal name of the Creek – Muskogee. Slave raiders from Texas continued to threaten the community but arms and reinforcements from the Mexican Army enabled the black warriors to defend their community.Mulroy 56–73, Porter ''Black'' 124–147.

By the 1940s, descendants of the Mascogos numbered 400–500 in Nacimiento de los Negros,

Coahuila

Coahuila (), formally Coahuila de Zaragoza (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Coahuila de Zaragoza ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Coahuila de Zaragoza), is one of the 32 states of Mexico.

Coahuila borders the Mexican states of N ...

, inhabiting lands adjacent to the Kickapoo tribe. They had a thriving agricultural community. By the 1990s, most of the descendants had moved into Texas.

Indian Territory/Oklahoma

Throughout the period, several hundred black Seminoles remained in the Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Because most of the Seminole and the other

Throughout the period, several hundred black Seminoles remained in the Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Because most of the Seminole and the other Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

supported the Confederacy during the American Civil War, in 1866 the US required new peace treaties with them. The US required the tribes emancipate any slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and extend to the freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom ...

full citizenship rights in the tribes if they chose to stay in Indian Territory. In the late nineteenth century, Seminole Freedmen thrived in towns near the Seminole communities on the reservation. Most had not been living as slaves to the Native Americans before the war. They lived —as their descendants still do— in and around Wewoka, Oklahoma

Wewoka is a city in Seminole County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 3,271 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Seminole County.

Founded by a freedman, John Coheia, and Black Seminoles in January, 1849, Wewoka is the capit ...

, the community founded in 1849 by John Horse as a black settlement. Today it is the capital of the federally recognized Seminole Nation of Oklahoma

The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma is a federally recognized Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. It is the largest of the three federally recognized Seminole governments, which include the Seminole Tribe of Florida and the M ...

.

Following the Civil War, some Freedmen's leaders in Indian Territory practiced polygyny

Polygyny (; from Neoclassical Greek πολυγυνία (); ) is the most common and accepted form of polygamy around the world, entailing the marriage of a man with several women.

Incidence

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than in any ...

, as did ethnic African leaders in other diaspora communities. In 1900 there were 1,000 Freedmen listed in the population of the Seminole Nation in Indian Territory, about one-third of the total. By the time of the Dawes Rolls

The Dawes Rolls (or Final Rolls of Citizens and Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes, or Dawes Commission of Final Rolls) were created by the United States Dawes Commission. The commission was authorized by United States Congress in 1893 to exe ...

, there were numerous female-headed households registered. The Freedmen's towns were made up of large, closely connected families.

After allotment, " eedmen, unlike their ativepeers on the blood roll, were permitted to sell their land without clearing the transaction through the Indian Bureau. That made the poorly educated Freedmen easy marks for white settlers migrating from the Deep South." Numerous Seminole Freedmen lost their land in the early decades after allotment, and some moved to urban areas. Others left the state because of its conditions of racial segregation. As US citizens, they were exposed to the harsher racial laws of Oklahoma.

Since 1954, the Freedmen have been included in the constitution of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma. They have two bands, each representing more than one town and named for 19th-century band leaders: the Cesar Bruner band covers towns south of Little River; the Dosar Barkus covers the several towns located north of the river. Each of the bands elects two representatives to the General Council of the Seminole Nation.

Texas community

In 1870, the U.S. Army invited black Seminoles to return from Mexico to serve as army scouts for the United States. Theblack Seminole Scouts

Black Seminole Scouts, also known as the Seminole Negro - Indian Scouts, or Seminole Scouts, were employed by the United States Army between 1870 and 1914. The unit included both Black Seminoles and some native Seminoles. However, because most ...

(originally an African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

unit despite the name) played a lead role in the Texas-Indian Wars of the 1870s, when they were based at Fort Clark, Texas

Fort Clark was a frontier fort located just off U.S. Route 90 near Brackettville, in Kinney County, Texas, United States. It later became the headquarters for the 2nd Cavalry Division. The Fort Clark Historic District was added to the National ...

, the home of the Buffalo Soldiers

Buffalo Soldiers originally were members of the 10th Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army, formed on September 21, 1866, at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. This nickname was given to the Black Cavalry by Native American tribes who fought in ...

. The scouts became famous for their tracking abilities and feats of endurance. Four men were awarded the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of val ...

, three for an 1875 action against the Comanche

The Comanche or Nʉmʉnʉʉ ( com, Nʉmʉnʉʉ, "the people") are a Native American tribe from the Southern Plains of the present-day United States. Comanche people today belong to the federally recognized Comanche Nation, headquartered in ...

.

After the close of the Texas Indian Wars, the scouts remained stationed at Fort Clark in Brackettville, Texas. The Army disbanded the unit in 1914. The veterans and their families settled in and around Brackettville, where scouts and family members were buried in its cemetery. The town remains the spiritual center of the Texas-based black Seminoles.Porter ''Black'' 175–216, Wallace ''Ranald S. Mackenzie'' 92–111.In 1981, descendants at Brackettville and the Little River community of Oklahoma met for the first time in more than a century, in Texas for a

Juneteenth

Juneteenth is a federal holiday in the United States commemorating the emancipation of enslaved African Americans. Deriving its name from combining "June" and "nineteenth", it is celebrated on the anniversary of General Order No. 3, i ...

reunion and celebration.Mulroy (2004), pp. 472-473.

Florida and Bahamas

Black Seminole descendants continue to live in Florida today. They can enroll in theSeminole Tribe of Florida

The Seminole Tribe of Florida is a federally recognized Seminole tribe based in the U.S. state of Florida. Together with the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, it is one of three federally recognized ...

if they meet its membership criteria for blood quantum

Blood quantum laws or Indian blood laws are laws in the United States that define Native American status by fractions of Native American ancestry. These laws were enacted by the federal government and state governments as a way to estab ...

: one-quarter Seminole ancestry. About 50 black Seminoles, all of whom have at least one-quarter Seminole ancestry, live on the Fort Pierce Reservation, a 50-acre parcel taken in trust in 1995 by the Department of Interior for the Tribe as its sixth reservation.

Descendants of Black Seminoles, who identify as Bahamian, reside on Andros Island

Andros Island is an archipelago within the Bahamas, the largest of the Bahamian Islands. Politically considered a single island, Andros in total has an area greater than all the other 700 Bahamian islands combined. The land area of Andros consis ...

in the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the a ...

. A few hundred refugees had left in the early nineteenth century from Cape Florida to go to the British colony for sanctuary from American enslavement.Goggin, ''The Seminole Negroes of Andros Island'', pp. 201–6, Mulroy, 26.After banning its participation in the

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and ...

in 1807

Events

January–March

* January 7 – The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland issues an Order in Council prohibiting British ships from trading with France or its allies.

* January 20 – The Sierra Leone Company, faced with ...

, in 1818 Britain declared that slaves who arrived in the Bahamas from outside the British West Indies would be manumitted

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

.Gerald Horne, ''Negro Comrades of the Crown: African Americans and the British Empire Fight the U.S. Before Emancipation''New York University (NYU) Press, 2012, p. 103. In 1833 Britain abolished slavery throughout its Empire. They have been sometimes referred to as "black Indians", in recognition of their history.

Seminole Freedmen exclusion controversy

In 1900, Seminole Freedmen numbered about 1,000 on the Oklahoma reservation, about one-third of the total population at the time. Members were registered on the Dawes Rolls for allocation of communal land to individual households. Since then, numerous Freedmen left after losing their land, as their land sales were not overseen by the Indian Bureau. Others left because of having to deal with the harshly segregated society of Oklahoma. The land allotments and participation in Oklahoma society altered relations between the Seminole and Freedmen, particularly after the 1930s. Both peoples faced racial discrimination from whites in Oklahoma, who essentially divided society into two: white and "other". Public schools and facilities were racially segregated. When the tribe reorganized under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, some Seminole wanted to exclude the Freedmen and keep the tribe as Native American only. It was not until the 1950s that the black Seminole were officially recognized in the constitution. Another was adopted in 1969, that restructured the government according to more traditional Seminole lines. It established 14 town bands, of which two represented Freedmen. The two Freedmen's bands were given two seats each, like other bands, on the Seminole General Council. There have been "battles over tribal membership across the country, as gambling revenues and federal land payments have given Native Americans something to fight over." In 2000, Seminole Freedmen were in the national news because of a legal dispute with theSeminole Nation of Oklahoma

The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma is a federally recognized Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. It is the largest of the three federally recognized Seminole governments, which include the Seminole Tribe of Florida and the M ...

, of which they had been legal members since 1866, over membership and rights within the tribe.

The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma

The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma is a federally recognized Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. It is the largest of the three federally recognized Seminole governments, which include the Seminole Tribe of Florida and the M ...

held the black Seminoles could not share in services to be provided by a $56 million federal settlement, a judgement trust, originally awarded in 1976 to the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and the Seminole Tribe of Florida

The Seminole Tribe of Florida is a federally recognized Seminole tribe based in the U.S. state of Florida. Together with the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, it is one of three federally recognized ...

(and other Florida Seminoles) by the federal government.Bill Drummond, "Indian Land Claims Unsettled 150 Years After Jackson Wars"''LA Times''/''Washington Post'' News Service, printed in ''Sarasota Herald-Tribune'', October 20, 1978, accessed April 13, 2013. The settlement was in compensation for land taken from them in northern Florida by the United States at the time of the signing of the

Treaty of Moultrie Creek

The Treaty of Moultrie Creek was an agreement signed in 1823 between the government of the United States and the chiefs of several groups and bands of Indians living in the present-day state of Florida. The treaty established a reservation in th ...

in 1823, when most of the Seminole and maroons were moved to a reservation in the center of the territory. This was before removal west of the Mississippi.

The judgement trust was based on the Seminole tribe as it existed in 1823. black Seminoles were not recognized legally as part of the tribe, nor was their ownership or occupancy of land separately recognized. The US government at the time would have assumed most were fugitive slaves, without legal standing. The Oklahoma and Florida groups were awarded portions of the judgement related to their respective populations in the early 20th century, when records were made of the mostly full-blood descendants of the time. The settlement apportionment was disputed in court cases between the Oklahoma and Florida tribes, but finally awarded in 1990, with three-quarters going to the Oklahoma people and one-quarter to those in Florida.

However, the black Seminole descendants asserted their ancestors had also held and farmed land in Florida, and suffered property losses as a result of US actions. They filed suit in 1996 against the Department of Interior to share in the benefits of the judgement trust of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, of which they were members.William Glaberson, "Who Is a Seminole, and Who Gets to Decide?"''New York Times'', January 29, 2001, April 11, 2013."Race part of Seminole dispute"

, Indianz.com, January 29, 2001, accessed April 11, 2013. In another aspect of the dispute over citizenship, in the summer of 2000 the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma voted to restrict members, according to

blood quantum

Blood quantum laws or Indian blood laws are laws in the United States that define Native American status by fractions of Native American ancestry. These laws were enacted by the federal government and state governments as a way to estab ...

, to those who had one-eighth Seminole ancestry, basically those who could document descent from a Seminole ancestor listed on the Dawes Rolls

The Dawes Rolls (or Final Rolls of Citizens and Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes, or Dawes Commission of Final Rolls) were created by the United States Dawes Commission. The commission was authorized by United States Congress in 1893 to exe ...

, the federal registry established in the early 20th century. At the time, during rushed conditions, registrars had separate lists for Seminole-Indian and Freedmen. They classified those with visible African ancestry as Freedmen, regardless of their proportion of Native American ancestry or whether they were considered Native members of the tribe at the time. This excluded some black Seminole from being listed on the Seminole-Indian list who qualified by ancestry.

The Dawes Rolls included in the Seminole-Indian list many Intermarried Whites who lived on Native American lands, but did not include blacks of the same status. The Seminole Freedmen believed the tribe's 21st-century decision to exclude them was racially based and has opposed it on those grounds. The Department of Interior said that it would not recognize a Seminole government that did not have Seminole Freedmen participating as voters and on the council, as they had officially been members of the nation since 1866. In October 2000, the Seminole Nation filed its own suit against the Interior Department, contending it had the sovereign right to determine tribal membership.

In April 2002, the Seminole Freedmen's suit against the government was dismissed in federal district court; the court ruled the Freedmen could not bring suit independently of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, which refused to join. They appealed to the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

, which in June 2004 affirmed that the Seminole Freedmen could not sue the federal government for inclusion in the settlement without the Seminole Nation joining. As a sovereign nation, they could not be ordered to join the suit.

Later that year, the Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal agency within the Department of the Interior. It is responsible for implementing federal laws and policies related to American Indians and A ...

held that the exclusion of black Seminoles constituted a violation of the Seminole Nation's 1866 treaty with the United States following the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. They noted that the treaty was made with a tribe that included black as well as white and brown members. The treaty had required the Seminole to emancipate

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure economic and social rights, political rights or equality, often for a specifically disenfranchis ...

their slaves, and to give the Seminole Freedmen full citizenship and voting rights. The BIA stopped federal funding for a time for services and programs to the Seminole.

The individual Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood

A Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood or Certificate of Degree of Alaska Native Blood (both abbreviated CDIB) is an official U.S. document that certifies an individual possesses a specific fraction of Native American ancestry of a federally rec ...

(CDIB) is based on registration of ancestors in the Indian lists of the Dawes Rolls. Although the BIA could not issue CDIBs to the Seminole Freedmen, in 2003 the agency recognized them as members of the tribe and advised them of continuing benefits for which they were eligible.Monica Keen, "Seminole Outcome May Affect Cherokee Freedmen"''Sequoyah County Times'', November 4, 2003, accessed April 10, 2013. Journalists theorized the decision could affect the similar case in which the

Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma

The Cherokee Nation ( Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ ''Tsalagihi Ayeli'' or ᏣᎳᎩᏰᎵ ''Tsalagiyehli''), also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. ...

excluded Cherokee Freedmen as members unless they could document a direct Native American ancestor on the Dawes Rolls.

Legacy and honors

* Fort Mose Historic State Park in Florida is a

* Fort Mose Historic State Park in Florida is a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places liste ...

at the site of the first free black community in the United States

*A large sign at Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park

Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Recreation Area occupies approximately the southern third of the island of Key Biscayne, at coordinates . This park includes the Cape Florida Light, the oldest standing structure in Greater Miami. In 2005, it was r ...

commemorates the site where hundreds of African Americans escaped to freedom in the Bahamas in the early 1820s, as part of the National Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

Network to Freedom Trail.

*A sign at the Manatee Mineral Spring marks the location where traces of Angola were uncovered

*Red Bays, Andros, the historic settlement of black Seminoles in the Bahamas, and Nacimiento, Mexico are being recognized as related international sites on the Network to Freedom Trail.

Notable black Seminoles

* Dosar Barkus, band leader from 1892 through allotment, namesake for contemporary band * Cesar Bruner, band leader from Reconstruction through statehood, namesake for contemporary bandMulroney (2007), "Seminole Freedmen", p. 271. * Eugene Bullard, one of the first black American military pilots *John Horse

John Horse (c. 1812–1882), also known as Juan Caballo, Juan Cavallo, John Cowaya (with spelling variations) and Gopher John, was of mixed ancestry (African and Seminole Indian) who fought alongside the Seminoles in the Second Seminole War in F ...

, leader at the time of removal, founder of Wewoka, and co-leader of 1849 escape to northern Mexico

* Sergeant John Ward

* Pompey Factor and Isaac Payne

Isaac Payne, or Isaac Paine, (1854–1904) was a Black Seminole who served as a United States Army Indian Scout and received America's highest military decoration—the Medal of Honor—for his actions in the Indian Wars of the western Unite ...

- Medal of Honor recipients for their service in the 24th Infantry.

See also

*Afro-Seminole Creole

__NOTOC__

Afro-Seminole Creole (ASC) is a dialect of Gullah spoken by Black Seminoles in scattered communities in Oklahoma, Texas, and Northern Mexico.

* black Indians in the United States

Black Indians are Native American people – defined as Native American due to being affiliated with Native American communities and being culturally Native American – who also have significant African American heritage.

Historically, certai ...

* black Seminole Scouts

Black Seminole Scouts, also known as the Seminole Negro - Indian Scouts, or Seminole Scouts, were employed by the United States Army between 1870 and 1914. The unit included both Black Seminoles and some native Seminoles. However, because most ...

* Ian Hancock

* List of topics related to black and African people

This is a list of topics related to the African diaspora.

Overview

* Black people

* African diaspora

Black diasporans by region

Americas

North America

* Afro-Guatemalan

* Afro-Honduran

* Belizean Kriol people

* Cimarron people (Panama), Cima ...

* One-Drop Rule

The one-drop rule is a legal principle of racial classification that was prominent in the 20th-century United States. It asserted that any person with even one ancestor of black ancestry ("one drop" of "black blood")Davis, F. James. Frontlin" ...

* Zambo

Zambo ( or ) or Sambu is a racial term historically used in the Spanish Empire to refer to people of mixed Indigenous and African ancestry. Occasionally in the 21st century, the term is used in the Americas to refer to persons who are of mixe ...

Notes

References

Primary sources

*Mahon, John K. (1967). ''History of the Second Seminole War 1835-1842 (Revised Edition). University of Florida Press. *McCall, George A. ''Letters From the Frontiers''. Philadelphia: Lippincott & Co., 1868. *Miller, David Hunter, ed. ''Treaties and Other International Acts of the United States of America''. 2 vols. Washington: GPO, 1931. *Mills, Charles K. (2011). ''Harvest of Barren Regrets: The Army Career of Frederick William Benteen 1834–1898.'' University of Nebraska Press. *United States. Attorney-General. ''Official Opinions of the Attorneys General of the United States''. Washington: United States, 1852–1870. *United States. Congress. ''American State Papers: Foreign Relations''. Vol 4. Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1832–1860. *United States. Congress. ''American State Papers: Military Affairs''. 7 vols. Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1832–1860.Secondary sources

*Akil II, Bakari. "Seminoles With African Ancestry: The Right To Heritage", ''The Black World Today'', December 27, 2003. *''Army and Navy Chronicle''. 13 vols. Washington: B. Homans, 1835–1842. *Baram, Uzi. "Cosmopolitan Meanings of Old Spanish Fields: Historical Archaeology of a Maroon Community in Southwest Florida" Historical Archaeology 46(1):108-122. 2012 *Baram, Uzi. "Many Histories by the Manatee Mineral Spring". Time Sifters Archaeological Society Newsletter March 2014. *Brown, Canter. "Race Relations in Territorial Florida, 1821–1845." ''Florida Historical Quarterly'' 73.3 (January 1995): 287–307. *Foreman, Grant. ''The Five Civilized Tribes''. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1934. *Foster, Laurence. ''Negro-Indian Relations in the Southeast''. PhD. Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 1935. *Giddings, Joshua R. ''The Exiles of Florida, or, crimes committed by our government against maroons, who fled from South Carolina and other slave states, seeking protection under Spanish laws''. Columbus, Ohio: Follet, 1858. *Goggin, John M. "The Seminole Negroes of Andros Island, Bahamas." ''Florida Historical Quarterly'' 24 (July 1946): 201–6. *Hancock, Ian F. ''The Texas Seminoles and Their Language''. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1980. *Indianz.com (2004)"Seminole Freedmen rebuffed by Supreme Court"

June 29, 2004.

Kashif, Annette. "Africanisms Upon the Land: A Study of African Influenced Placenames of the USA"

In ''Places of Cultural Memory: African Reflections on the American Landscape''. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 2001. *Landers, Jane. ''Black Society in Spanish Florida''. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999. *Littlefield, Daniel F., Jr. ''Africans and Seminoles''. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1977. *Mahon, John K. ''History of the Second Seminole War, 1835–1842''. 1967. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1985. *Mulroy, Kevin. ''Freedom on the Border: The Seminole Maroons in Florida, the Indian Territory, Coahuila, and Texas''. Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 1993. *Mulroy, Kevin. ''The Seminole Freedmen: A History (Race and Culture in the American West)'', Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007. *Porter, Kenneth Wiggins. ''The Black Seminoles: History of a Freedom-Seeking People''. Eds Thomas Senter and Alcione Amos. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1996. *Porter, Kenneth Wiggins. ''The Negro on the American Frontier''. New York: Arno Press, 1971. *Rivers, Larry Eugene. ''Slavery in Florida''. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000. *Schneider, Pamela S. ''It's Not Funny: Various Aspects of Black History'' Charlotte PA: Lemieux Press Publishers, 2005.