Black Nova Scotians (also known as African Nova Scotians and Afro-Nova Scotians) are

Black Canadians

Black Canadians (also known as Caribbean-Canadians or Afro-Canadians) are people of full or partial sub-Saharan African descent who are citizens or permanent residents of Canada. The majority of Black Canadians are of Caribbean origin, though ...

whose ancestors primarily date back to the

Colonial United States

The colonial history of the United States covers the history of European colonization of North America from the early 17th century until the incorporation of the Thirteen Colonies into the United States after the Revolutionary War. In the ...

as

slaves or

freemen, later arriving in

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, Canada, during the 18th and early 19th centuries. As of the

2021 Census of Canada, 28,220 Black people live in Nova Scotia,

most in

Halifax. Since the 1950s, numerous Black Nova Scotians have migrated to

Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

for its larger range of opportunities.

Before the immigration reforms of 1967, Black Nova Scotians formed 37% of the total Black Canadian population.

The first Black person in Nova Scotia,

Mathieu da Costa, a

Mikmaq interpreter, was recorded among the founders of

Port Royal in 1604. West Africans were brought as enslaved people both in early British and French Colonies in the 17th and 18th centuries. Many came as enslaved people, primarily from the

French West Indies to Nova Scotia during the founding of

Louisbourg. The second major migration of Blacks to Nova Scotia happened following the

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, when the British evacuated thousands of slaves who had fled to their lines during the war. They were promised freedom by the Crown if they joined British lines, and some 3,000 African Americans were resettled in Nova Scotia after the war, where they were known as

Black Loyalists. There was also the forced migration of the

Jamaican Maroons

Jamaican Maroons descend from Africans who freed themselves from slavery on the Colony of Jamaica and established communities of free black people in the island's mountainous interior, primarily in the eastern parishes. Africans who were ensl ...

in 1796, although the British supported the desire of a third of the Loyalists and nearly all of the Maroons to establish

Freetown

Freetown is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational and po ...

in

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

four years later, where they formed the

Sierra Leone Creole

The Sierra Leone Creole people ( kri, Krio people) are an ethnic group of Sierra Leone. The Sierra Leone Creole people are lineal descendant, descendants of freed African-American, Afro-Caribbean, and Sierra Leone Liberated African, Liberated Af ...

ethnic identity.

[ https://www.persee.fr/doc/cea_0008-0055_1991_num_31_121_2116][ Journal of Sierra Leone Studies, Vol. 3; Edition 1, 2014 https://www.academia.edu/40720522/A_Precis_of_Sources_relating_to_genealogical_research_on_the_Sierra_Leone_Krio_people][, originally published by Longman & Dalhousie University Press (1976).]

In this period, British missionaries began to develop educational opportunities for Black Nova Scotians through the

Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Societi ...

(

Bray Schools).

The decline of slavery in Nova Scotia happened in large part by local judicial decisions in keeping with those by the British courts of the late 18th century.

The next major migration of Blacks happened during the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

, again with African Americans escaping slavery in the United States. Many came after having gained passage and freedom on British ships. The British issued a proclamation in the South promising freedom and land to those who wanted to join them. Creation of institutions such as the

Royal Acadian School

The Royal Acadian School was a school developed for marginalized people in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The school was established by British officer and reformer Walter Bromley on 13 January 1814. He promoted the objectives of the British and Foreign S ...

and the

African Baptist Church in Halifax, founded in 1832, opened opportunities for Black Canadians. During the years before the American Civil War, an estimated ten to thirty thousand African Americans migrated to Canada, mostly as individual or small family groups; many settled in Ontario. A number of Black Nova Scotians also have some

Indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

heritage, due to historical intermarriage between Black and

First Nations

First Nations or first peoples may refer to:

* Indigenous peoples, for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area.

Indigenous groups

*First Nations is commonly used to describe some Indigenous groups including:

**First Natio ...

communities.

In the 20th century, Black Nova Scotians organized for civil rights, establishing such groups as the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People, the

Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission

The Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission (the “Commission”) was established in Nova Scotia, Canada in 1967 to administer the Nova Scotia ''Human Rights Act''. The Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission is the first commission in Canada to engage ...

, the

Black United Front

Black United Front also known as The Black United Front of Nova Scotia or simply BUF was a Black nationalist organization primarily based in Halifax, Nova Scotia during the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. Preceded by the Nova Scotia ...

, and the

Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia. In the 21st century, the government and grassroots groups have initiated actions in Nova Scotia to address past harm done to Black Nova Scotians, such as the

Africville Apology

The Africville Apology was a formal pronouncement delivered on 24 February 2010 by the City of Halifax, Nova Scotia for the eviction and eventual destruction of Africville, a Black Nova Scotian community.

Historical context

During the 1940s a ...

, the

Viola Desmond Pardon, the restorative justice initiative for the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children, and most recently the official apology to the

No. 2 Construction Battalion.

History

Black Nova Scotians by share of overall Black Canadian population:

17th century

Port Royal

The first recorded Black person in Canada was

Mathieu da Costa. He arrived in Nova Scotia sometime between 1605 and 1608 as a translator for the French explorer

Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Monts

Pierre Dugua de Mons (or Du Gua de Monts; c. 1558 – 1628) was a French merchant, explorer and colonizer. A Calvinist, he was born in the Château de Mons, in Royan, Saintonge (southwestern France) and founded the first permanent French set ...

. The first known Black person to live in Canada was an enslaved person from Madagascar named

Olivier Le Jeune (who may have been of partial

Malay ancestry).

18th century

Louisbourg

Of the 10,000 French living at

Louisbourg (1713–1760) and on the rest of

Ile Royale, 216 were African-descended slaves. According to historian Kenneth Donovan, slaves on Ile Royal worked as "servants, gardeners, bakers, tavern keepers, stone masons, musicians, laundry workers, soldiers, sailors, fishermen, hospital workers, ferry men, executioners and nursemaids." More than 90 per cent of the enslaved people were Blacks from the

French West Indies, which included Saint-Domingue, the chief sugar colony, and Guadeloupe.

Halifax

Among the founders recorded for Halifax, were 17 free Black people. By 1767, there were 54 Blacks living in Halifax. When

Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348 ...

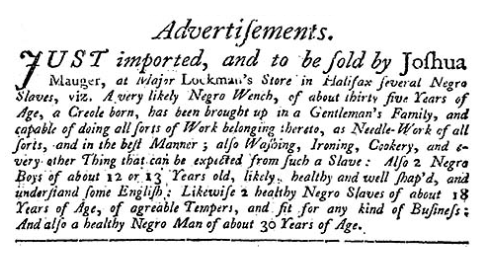

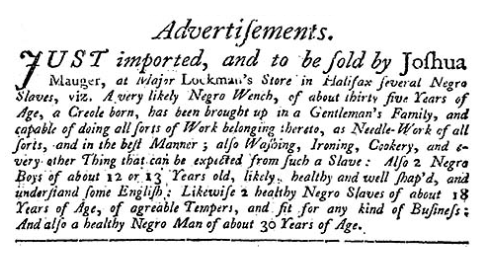

was established (1749), some British people brought slaves to the city. For example, shipowner and trader

Joshua Mauger

Joshua Mauger (1725– 18 October 1788) was a prominent merchant and slave trader in Halifax, Nova Scotia (1749–60) and then went to England and became Nova Scotia's colonial agent (1762). He has been referred to as "the first great merchant an ...

sold enslaved people at auction there. A few newspaper advertisements were published for run-away slaves.

The first Black community in Halifax was on Albemarle Street, which later became the site of the first school for Black students in Nova Scotia (1786).

[pp. 71-72](_blank)

/ref> The school for Black students was the only charitable school in Halifax for the next 26 years. Whites were not allowed to attend.[''The Black Loyalists: The Search for a Promised Land in Nova Scotia and ...'' By ]James W. St. G. Walker

James W. St.G. Walker (born August 5, 1940) is a Canadian professor of history at the University of Waterloo, and a historian of human rights and racism.

Walker received his PhD from Dalhousie University in 1973.

Prior to 1799, 29 recorded Blacks were buried in the Old Burying Ground (Halifax, Nova Scotia)

The Old Burying Ground (also known as St. Paul's Church Cemetery) is a historic cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. It is located at the intersection of Barrington Street and Spring Garden Road in Downtown Halifax.

History

The Old Bur ...

, of which 12 of them were listed with both first and last names; seven of the graves are from the New England Planter

The New England Planters were settlers from the New England colonies who responded to invitations by the lieutenant governor (and subsequently governor) of Nova Scotia, Charles Lawrence, to settle lands left vacant by the Bay of Fundy Campaign ( ...

migration (1763-1775); and 22 graves are from immediately following the arrival of the Black Loyalists in 1776. Rev. John Breynton

John Breynton (1719 – 15 July 1799) was a minister in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

He was born in Trefeglwys, Montgomeryshire, Wales to John Breynton (born 1670 Llanidloes) and his second wife, and baptised on 13 April 1719. He spent his fi ...

reported that in 1783, he baptized 40 Blacks and buried many because of disease.Freetown

Freetown is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational and po ...

(now Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

). A return in December 1816 indicates there were 155 Blacks who migrated to Halifax during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

.

American Revolution

The British had promised enslaved people of rebels freedom if they joined their forces (See Dunmore's Proclamation

Dunmore's Proclamation is a historical document signed on November 7, 1775, by John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, royal governor of the British Colony of Virginia. The proclamation declared martial law and promised freedom for slaves of American ...

and Philipsburg Proclamation). Approximately three thousand Black Loyalists were evacuated by ship to Nova Scotia between April and November 1783, traveling on Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

vessels or British chartered private transports. This group was made up largely of tradespeople and labourers. Many of these African Americans had roots in the American states of Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia and Maryland. Some came from Massachusetts, New Jersey and New York as well. Many of these African-American settlers were recorded in the ''Book of Negroes

The ''Book of Negroes'' is a document created by Brigadier General Samuel Birch, under the direction of Sir Guy Carleton, that records names and descriptions of 3,000 Black Loyalists, enslaved Africans who escaped to the British lines during ...

''.

In 1785 in Halifax, educational opportunities began to develop with the establishment of Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Societi ...

( Bray Schools).Old Burying Ground (Halifax, Nova Scotia)

The Old Burying Ground (also known as St. Paul's Church Cemetery) is a historic cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. It is located at the intersection of Barrington Street and Spring Garden Road in Downtown Halifax.

History

The Old Bur ...

.[Jack C. Whytock. ''Historical Papers 2003: Canadian Society of Church History''. Edited by Bruce L. Guenther, p.154.] After a year he was followed by Isaac Limerick.Royal Acadian School

The Royal Acadian School was a school developed for marginalized people in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The school was established by British officer and reformer Walter Bromley on 13 January 1814. He promoted the objectives of the British and Foreign S ...

was established for Blacks and whites).Rose Fortune

Rose Fortune (March 13, 1774 – February 20, 1864) was a child born in or around Philadelphia of runaway slaves. Her parents became Black Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War when they pledged to be loyal to the British Army in exc ...

, Black Loyalist

Black Loyalists were people of African descent who sided with the Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War. In particular, the term refers to men who escaped enslavement by Patriot masters and served on the Loyalist side because of the C ...

– Annapolis Royal

Annapolis Royal, formerly known as Port-Royal (Acadia), Port Royal, is a town located in the western part of Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Today's Annapolis Royal is the second French settlement known by the same name and should not be ...

1830

File:Lawrence Hartshorne, Old Burying Ground, Halifax, Nova Scotia.jpg, Lawrence Hartshorne, d. 1822, a Quaker who was the chief assistant of John Clarkson (abolitionist)

Lieutenant John Clarkson (4 April 1764 – 2 April 1828) was a Royal Navy officer and abolitionist, the younger brother of Thomas Clarkson, one of the central figures in the abolition of slavery in England and the British Empire at the close of ...

in helping the Black Nova Scotian Settlers

The Nova Scotian Settlers, or Sierra Leone Settlers (also known as the Nova Scotians or more commonly as the Settlers) were African-Americans who founded the settlement of Freetown, Sierra Leone and the Colony of Sierra Leone, on March 11, 1792 ...

emigrate to Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

(1792) – Old Burying Ground (Halifax, Nova Scotia)

The Old Burying Ground (also known as St. Paul's Church Cemetery) is a historic cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. It is located at the intersection of Barrington Street and Spring Garden Road in Downtown Halifax.

History

The Old Bur ...

File:William Furmage, Halifax, Nova Scotia.jpg, Reverend William Furmage, Huntingdonian Missionary to the Black Loyalists, established black school in Halifax

=Black Pioneers

=

Many of the black Loyalists performed military service in the British Army, particularly as part of the only black regiment of the war, the Black Pioneers

The Black Company of Pioneers, also known as the Black Pioneers and Clinton's Black Pioneers, were a British Provincial military unit raised for Loyalist service during the American Revolutionary War. The Black Loyalist company was raised by Gener ...

, while others served non-military roles. The soldiers of the Black Pioneers settled in Digby and were given small compensation in comparison to the white Loyalist soldiers. Many of the blacks settled under the leadership of Stephen Blucke

Stephen Blucke or Stephen Bluck (born –after 1796) was a Black Loyalist, in the American Revolutionary War, and one the commanding officers, of the British Loyalist provincial unit, the Black Company of Pioneers. He was one of 3,000 people who ...

, a prominent black leader of the Black Pioneers. Historian Barry Moody has referred to Blucke as "the true founder of the Afro-Nova Scotian community."

=Birchtown

=

Blucke led the founding of Birchtown, Nova Scotia

Birchtown is a community and National Historic Site in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, located near Shelburne in the Municipal District of Shelburne County. Founded in 1783, the village was the largest settlement of Black Loyalists and t ...

in 1783. The community was the largest settlement of Black Loyalists and was the largest free settlement of Africans in North America in the 18th century. The community was named after British Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Samuel Birch

Samuel Birch (3 November 1813 – 27 December 1885) was a British Egyptologist and antiquary.

Biography

Birch was the son of a rector at St Mary Woolnoth, London. He was educated at Merchant Taylors' School. From an early age, his manifest ...

, an official who assisted in the evacuation of Black Loyalists from New York. (Also named after the general was a much smaller settlement of Black Loyalists in Guysborough County, Nova Scotia

Guysborough County is a county in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia.

History

Taking its name from the Township of Guysborough, which was named in honour of Sir Guy Carleton, Guysborough County was created when Sydney County (Antigonish Coun ...

called Birchtown.) The two other significant Black Loyalist communities established in Nova Scotia were Brindley town (present-day Jordantown) and Tracadie. Birchtown was located near the larger town of Shelburne, with a majority white population. Racial tensions in Shelburne erupted into the 1784 Shelburne riots, when white Loyalist residents drove Black residents out of Shelburne and into Birchtown. In the years after the riot, Shelbourne county lost population due to economic factors, and at least half of the families in Birchtown abandoned the settlement and emigrated to Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

in 1792. To accommodate these British subjects, the British government approved 16,000 pounds for the emigration, three times the total annual budget for Nova Scotia. They were led to Sierra Leone by John Clarkson (abolitionist)

Lieutenant John Clarkson (4 April 1764 – 2 April 1828) was a Royal Navy officer and abolitionist, the younger brother of Thomas Clarkson, one of the central figures in the abolition of slavery in England and the British Empire at the close of ...

and became known as the Nova Scotian Settlers

The Nova Scotian Settlers, or Sierra Leone Settlers (also known as the Nova Scotians or more commonly as the Settlers) were African-Americans who founded the settlement of Freetown, Sierra Leone and the Colony of Sierra Leone, on March 11, 1792 ...

.

=Tracadie

=

The other significant Black Loyalist settlement is Tracadie. Led by Thomas Brownspriggs, Black Nova Scotians who had settled at Chedabucto Bay behind the present-day village of

The other significant Black Loyalist settlement is Tracadie. Led by Thomas Brownspriggs, Black Nova Scotians who had settled at Chedabucto Bay behind the present-day village of Guysborough

Guysborough (population: 397) is an unincorporated Canadian community in Guysborough County, Nova Scotia.

Located on the western shore of Chedabucto Bay, fronting Guysborough Harbour, it is the administrative seat of the Guysborough municip ...

migrated to Tracadie (1787). None of the blacks in eastern Nova Scotia migrated to Sierra Leone.

One of the Black Loyalists was Andrew Izard (c. 1755 – ?). He was formerly enslaved by Ralph Izard in St. George, South Carolina. He worked on a rice plantation and grew up on Combahee. When he was young he was valued at 100 pounds. In 1778 Izard made his escape. During the American Revolution he worked for the British army in the wagonmaster-general's department. He was on one of the final ships to leave New York in 1783. He traveled on the Nisbett in November, which sailed to Port Mouton. The village burned to the ground in the spring of 1784 and he was transported to Guysborough. There he raised a family and still has descendants that live in the community.

Education in the Black community was initially advocated by Charles Inglis who sponsored the Protestant Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. Some of the schoolmasters were: Thomas Brownspriggs (c.1788–1790) and Dempsey Jordan (1818–?). There were 23 Black families at Tracadie in 1808; by 1827 this number had increased to 30 or more.

Abolition of slavery, 1787–1812

While most Blacks who arrived in Nova Scotia during the American Revolution were free, others were not. Enslaved Black peoples also arrived in Nova Scotia as the property of White American

White Americans are Americans who identify as and are perceived to be white people. This group constitutes the majority of the people in the United States. As of the 2020 Census, 61.6%, or 204,277,273 people, were white alone. This represented ...

Loyalists. In 1772, prior to the American Revolution, Britain outlawed the slave trade in the British Isles followed by the Knight v. Wedderburn decision in Scotland in 1778. This decision, in turn, influenced the colony of Nova Scotia. In 1788, abolitionist James Drummond MacGregor from Pictou published the first anti-slavery literature in Canada and began purchasing slaves' freedom and chastising his colleagues in the Presbyterian church who enslaved people. Historian Alan Wilson describes the document as "a landmark on the road to personal freedom in province and country." Historian Robin Winks

Robin W. Winks (December 5, 1930 in Indiana – April 7, 2003 in New Haven, Connecticut) was an American academic, historian, diplomat, writer on the subject of fiction, especially detective novels, and advocate for the National Parks. After jo ...

writes "t is

T, or t, is the twentieth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''tee'' (pronounced ), plural ''tees''. It is der ...

the sharpest attack to come from a Canadian pen even into the 1840s; he had also brought about a public debate which soon reached the courts." In 1790 John Burbidge

John Burbidge (c.1718 – March 11, 1812) was a soldier, land owner, judge and political figure in Nova Scotia. He was a member of the 1st General Assembly of Nova Scotia in 1758 and represented Halifax Township from 1759 to 1765 and Cornwal ...

freed the people he had enslaved.

Led by Richard John Uniacke

Richard John Uniacke (November 22, 1753 – October 11, 1830) was an abolitionist, lawyer, politician, member of the Nova Scotia House of Assembly and Attorney General of Nova Scotia. According to historian Brian Cutherburton, Uniacke was " ...

, in 1787, 1789 and again on January 11, 1808, the Nova Scotian legislature refused to legalize slavery. Two chief justices, Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange (1790–1796) and Sampson Salter Blowers (1797–1832) waged "judicial war" in their efforts to free enslaved people from their owners in Nova Scotia. They were held in high regard in the colony. Justice Alexander Croke (1801–1815) also impounded American slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast ...

s during this time period (the most famous being the ''Liverpool Packet

''Liverpool Packet'' was a privateer schooner from Liverpool, Nova Scotia, that captured 50 American vessels in the War of 1812. American privateers captured ''Liverpool Packet'' in 1813, but she failed to take any prizes during the four months bef ...

''). The last slave sale in Nova Scotia occurred in 1804. During the war, Nova Scotian Sir William Winniett served as a crew on board in the effort to free enslaved people from America. (As the Governor of the Gold Coast

Gold Coast may refer to:

Places Africa

* Gold Coast (region), in West Africa, which was made up of the following colonies, before being established as the independent nation of Ghana:

** Portuguese Gold Coast (Portuguese, 1482–1642)

** Dutch G ...

, Winniett would later also work to end the slave trade in Western Africa.) By the end of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

and the arrival of the Black Refugees, there were few people left enslaved in Nova Scotia.Slave Trade Act

Slave Trade Act is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom and the United States that relates to the slave trade.

The "See also" section lists other Slave Acts, laws, and international conventions which developed the conce ...

outlawed the slave trade in the British Empire in 1807 and the Slavery Abolition Act

The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which provided for the gradual abolition of slavery in most parts of the British Empire. It was passed by Earl Grey's reforming administrati ...

of 1833 outlawed slavery all together.)

File:RichardJohnUniackeByRobertField.jpg, Abolitionist Richard John Uniacke

Richard John Uniacke (November 22, 1753 – October 11, 1830) was an abolitionist, lawyer, politician, member of the Nova Scotia House of Assembly and Attorney General of Nova Scotia. According to historian Brian Cutherburton, Uniacke was " ...

, helped free Black Nova Scotian slaves

File:Sampson Salter Blowers 2.jpg, Chief Justice Sampson Salter Blowers, freed Black Nova Scotian slaves

File:Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange by Benjamin West.png, Chief Justice Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange, freed Black Nova Scotian slaves

File:Sir Alexander Croke.png, Sir Alexander Croke

File:RevJamesMacgregorMonumentPictouNovaScotia.jpg, James Drummond MacGregor Monument, Pictou, Nova Scotia

Pictou ( ; Canadian Gaelic: ''Baile Phiogto'') is a town in Pictou County, in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia. Located on the north shore of Pictou Harbour, the town is approximately 10 km (6 miles) north of the larger town of New Glas ...

Jamaican Maroons

According to one historian, on June 26, 1796, 543 men, women and children, Jamaican Maroons

Jamaican Maroons descend from Africans who freed themselves from slavery on the Colony of Jamaica and established communities of free black people in the island's mountainous interior, primarily in the eastern parishes. Africans who were ensl ...

, were deported on board the ships Dover, Mary and Anne, from Jamaica after being defeated in an uprising against the British colonial government. However, many historians disagree on the number who were transported from Jamaica to Nova Scotia, with one saying that 568 Maroons of Cudjoe's Town (Trelawny Town)

Cudjoe's Town was located in the mountains in the southern extremities of the parish of St James, close to the border of Westmoreland, Jamaica.

In 1690, a large number of Akan freedom fighters from Sutton's Estate in south-western Jamaica, and th ...

made the trip in 1796. It seems that just under 600 left Jamaica, with 17 dying on the ship, and 19 in their first winter in Nova Scotia. A Canadian surgeon counted 571 Maroons in Nova Scotia in 1797. Their initial destination was Lower Canada but on July 21 and 23, the ships arrived in Nova Scotia. At this time Halifax was experiencing a major construction boom initiated by Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn's efforts to modernize the city's defenses. The many building projects had created a labour shortage. Edward was impressed by the Maroons and immediately put them to work at the Citadel in Halifax, Government House, and other defense works throughout the city.

The British Lieutenant Governor Sir John Wentworth, from the monies provided by the Jamaican Government, procured an annual stipend of £240 for the support of a school and religious education.[John N. Grant. "Black Immigrants into Nova Scotia, 1776–1815". ''The Journal of Negro History''. Vol. 58, No. 3 (July 1973), pp. 253–270.] The Maroons complained about the bitterly cold winters, their segregated conditions, unfamiliar farming methods, and less than adequate accommodation. The Maroon leader, Montague James

Montague James (d. c. 1812) was a Maroon leader of Cudjoe's Town (Trelawny Town) in the last decade of eighteenth-century Jamaica. It is possible that Maroon colonel Montague James took his name from the white superintendent of Trelawny Town, J ...

, petitioned the British government for the right to passage to Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

, and they were eventually granted that opportunity in the face of opposition from Wentworth. On August 6, 1800, the Maroons departed Halifax, arriving on October 1 at Freetown

Freetown is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational and po ...

, Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

.Maroon Town, Sierra Leone Maroon Town, Sierra Leone, is a district in the settlement of Freetown, a colony founded in West Africa by Great Britain.

History

Following their defeat in the American Revolutionary War, the British had resettled African Americans in the British c ...

.

19th century

In 1808, George Prévost

Sir George Prévost, 1st Baronet (19 May 1767 – 5 January 1816) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator who is most well known as the "Defender of Canada" during the War of 1812. Born in New Jersey, the eldest son of Genevan Augu ...

authorized a Black regiment to be formed in the colony under captain Silas Hardy and Col. Christopher Benson.

War of 1812

The next major migration of Blacks into Nova Scotia occurred between 1813 and 1815. Black Refugees from the

The next major migration of Blacks into Nova Scotia occurred between 1813 and 1815. Black Refugees from the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

settled in many parts of Nova Scotia including Hammonds Plains, Beechville, Lucasville and Africville.

Canada was not suited to the large-scale plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people t ...

practiced in the southern United States, and slavery became increasingly rare. In 1793, in one of the first acts of the new Upper Canadian colonial parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

, slavery was abolished. It was all but abolished throughout the other British North American colonies by 1800, and was illegal throughout the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

after 1834. This made Canada an attractive destination for those fleeing slavery in the United States, such as American minister Boston King Boston King ( 1760–1802) was a former American slave and Black Loyalist, who gained freedom from the British and settled in Nova Scotia after the American Revolutionary War. He later immigrated to Sierra Leone, where he helped found Freetown and b ...

.

Royal Acadian School

In 1814, Walter Bromley

Walter Henry Bromley (c. 1774 – c. 5 May 1838) was a British military officer and reformer who founded a school in Halifax, Nova Scotia and did much good work among children of poorer families including, especially, indigenous Canadians. He lat ...

opened the Royal Acadian School

The Royal Acadian School was a school developed for marginalized people in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The school was established by British officer and reformer Walter Bromley on 13 January 1814. He promoted the objectives of the British and Foreign S ...

which included many Black students – children and adults – whom he taught on the weekends because they were employed during the week. Some of the Black students entered into business in Halifax while others were hired as servants.

In 1836, the African School was established in Halifax from the Protestant Gospel School (Bray School) and was soon followed by similar schools at Preston, Hammond's Plains and Beech Hill.

New Horizons Baptist Church

Following Black Loyalist preacher David George, Baptist minister John Burton was one of the first ministers to integrate Black and white Nova Scotians into the same congregation.

Following Black Loyalist preacher David George, Baptist minister John Burton was one of the first ministers to integrate Black and white Nova Scotians into the same congregation.[Burton, John]

Dictionary of Canadian Biography

The ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography'' (''DCB''; french: Dictionnaire biographique du Canada) is a dictionary of biographical entries for individuals who have contributed to the history of Canada. The ''DCB'', which was initiated in 1959, is a ...

. In 1811 Burton's church had 33 members, the majority of whom were free Blacks from Halifax and the neighbouring settlements of Preston and Hammonds Plains. According to historian Stephen Davidson, the Blacks were "shunned, or merely tolerated, by the rest of Christian Halifax, the Blacks were first warmly received in the Baptist Church."[ Burton became known as "an apostle to the coloured people" and would often be sent out by the Baptist association on missionary visits to the black communities surrounding Halifax. He was the mentor of ]Richard Preston

Richard Preston (born August 5, 1954) is a writer for ''The New Yorker'' and bestselling author who has written books about infectious disease, bioterrorism, redwoods and other subjects, as well as fiction.

Biography

Preston was born in Cambri ...

.

New Horizons Baptist Church (formerly known as Cornwallis Street Baptist Church, the African Chapel, and the African Baptist Church) is a

New Horizons Baptist Church (formerly known as Cornwallis Street Baptist Church, the African Chapel, and the African Baptist Church) is a baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

church in Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348 ...

that was established by Black Refugees in 1832. When the chapel was completed, Black citizens of Halifax were reported to be proud of this accomplishment because it was evidence that former enslaved people could establish their own institutions in Nova Scotia.African United Baptist Association

African or Africans may refer to:

* Anything from or pertaining to the continent of Africa:

** People who are native to Africa, descendants of natives of Africa, or individuals who trace their ancestry to indigenous inhabitants of Africa

*** Ethn ...

.

The church remained the centre of social activism throughout the 20th Century. Reverends at the church included William A. White (1919–1936) and William Pearly Oliver

William Pearly Oliver (February 11, 1912 in Wolfville, Nova Scotia – May 26, 1989 in Lucasville) worked at the Cornwallis Street Baptist Church for twenty-five years (1937–1962) and was instrumental in developing the four leading organizati ...

(1937–1962).

American Civil War

Numerous Black Nova Scotians fought in the

Numerous Black Nova Scotians fought in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

in the effort to end slavery. Perhaps the most well known Nova Scotians to fight in the war effort are Joseph B. Noil and Benjamin Jackson. Three Black Nova Scotians served in the famous 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry

The 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that saw extensive service in the Union Army during the American Civil War. The unit was the second African-American regiment, following the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry ...

: Hammel Gilyer, Samuel Hazzard, and Thomas Page.[Tom Brook]

"All Men are Brothers"

1995. LWF Publications. historical quarterly, Lest We Forget.

20th century

Coloured Hockey League

In 1894, an all-Black

In 1894, an all-Black ice hockey

Ice hockey (or simply hockey) is a team sport played on ice skates, usually on an ice skating rink with lines and markings specific to the sport. It belongs to a family of sports called hockey. In ice hockey, two opposing teams use ice h ...

league, known as the Coloured Hockey League

The Coloured Hockey League of the Maritimes (CHL) was an all-black ice hockey league founded in Nova Scotia in 1895, which featured teams from across Canada's Maritime Provinces. The league operated for several decades lasting until 1930.

Hist ...

, was founded in Nova Scotia. Black players from Canada's Maritime provinces

The Maritimes, also called the Maritime provinces, is a region of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Maritimes had a population of 1,899,324 in 2021, which makes up 5.1% of Ca ...

(Nova Scotia, New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

, Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island (PEI; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is the smallest province in terms of land area and population, but the most densely populated. The island has several nicknames: "Garden of the Gulf", ...

) participated in competition. The league began to play 23 years before the National Hockey League

The National Hockey League (NHL; french: Ligue nationale de hockey—LNH, ) is a professional ice hockey league in North America comprising 32 teams—25 in the United States and 7 in Canada. It is considered to be the top ranked professional ...

was founded, and as such, it has been credited with some innovations which exist in the NHL today. Most notably, it is claimed that the first player to use the slapshot

A slapshot (also spelled as slap shot) in ice hockey is a powerful shot. Its advantage is as a high-speed shot that can be taken from long distance; the disadvantage is the time to set it up as well as its low accuracy.

It has four stages wh ...

was Eddie Martin of the Halifax Eurekas, more than 100 years ago.[Martins, Daniel]

Hockey historian credits black player with first slapshot

, CanWest News Service, January 31, 2007. Accessed on August 19, 2012. The league remained in operation until 1930.

World War One

The No. 2 Construction Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), was the only predominantly Black

The No. 2 Construction Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), was the only predominantly Black battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions a ...

in Canadian military history

The military history of Canada comprises hundreds of years of armed actions in the territory encompassing modern Canada, and interventions by the Canadian military in conflicts and peacekeeping worldwide. For thousands of years, the area that woul ...

and also the only Canadian Battalion composed of Black soldiers to serve in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. The battalion was raised in Nova Scotia and 56% of battalion members (500 soldiers) came from the province. Reverend William A. White of the Battalion became the first Black officer in the British Empire.

An earlier black military unit in Nova Scotia was the Victoria Rifles.

Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People

Led by minister William Pearly Oliver

William Pearly Oliver (February 11, 1912 in Wolfville, Nova Scotia – May 26, 1989 in Lucasville) worked at the Cornwallis Street Baptist Church for twenty-five years (1937–1962) and was instrumental in developing the four leading organizati ...

, the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People was formed in 1945 out of the Cornwallis Street Baptist Church. The organization was intent of improving the standard of living for Black Nova Scotians. The organization also attempted to improve Black-white relations in co-operation with private and governmental agencies. The organization was joined by 500 Black Nova Scotians. By 1956, the NSAACP had branches in Halifax, Cobequid Road, Digby, Wegymouth Falls, Beechville, Inglewooe, Hammonds Plains and Yarmouth. Preston and Africville branches were added in 1962, the same year New Road, Cherrybrook, and Preston East requested branches.[Thomson, p. 81] In 1947, the Association successfully took the case of Viola Desmond

Viola Irene Desmond (July 6, 1914 – February 7, 1965) was a Canadian civil and women's rights activist and businesswoman of Black Nova Scotian descent. In 1946, she challenged racial segregation at a cinema in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia by refu ...

to the Supreme Court of Canada. It also pressured the Children's Hospital in Halifax to allow for Black women to become nurses; it advocated for inclusion and challenged racist curriculum in the Department of Education. The Association also developed an Adult Education program with the government department.

By 1970, over one-third of the 270 members were white.

Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission

Along with Oliver and the direct involvement of the premier of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

Robert Stanfield, many Black activists were responsible for the establishment of the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission

The Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission (the “Commission”) was established in Nova Scotia, Canada in 1967 to administer the Nova Scotia ''Human Rights Act''. The Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission is the first commission in Canada to engage ...

(1967). Originally the mandate of the commission was primarily to address the plight of Black Nova Scotians. The first employee and administrative officer of the commission was Gordon Earle

Gordon S. Earle (born February 27, 1943) is a Canadian politician. Earle is a member of the New Democratic Party and a former member of the House of Commons of Canada, representing the riding of Halifax West from 1997 to 2000. Earle is the f ...

.

Black United Front

In keeping with the times, Reverend William Oliver began the

In keeping with the times, Reverend William Oliver began the Black United Front

Black United Front also known as The Black United Front of Nova Scotia or simply BUF was a Black nationalist organization primarily based in Halifax, Nova Scotia during the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. Preceded by the Nova Scotia ...

in 1969, which explicitly adopted a Black separatist agenda. The Black separatist movement of the United States had a significant influence on the mobilization of the Black community in 20th Century Nova Scotia. This Black separatist approach to address racism and black empowerment was introduced to Nova Scotia by Marcus Garvey

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Sr. (17 August 188710 June 1940) was a Jamaican political activist, publisher, journalist, entrepreneur, and orator. He was the founder and first President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African ...

in the 1920s.[Jon Tattrie]

''Sunday Chronicle-Herald'', November 29, 2009

Garvey argued that Black people would never get a fair deal in white society, so they ought to form separate republics or return to Africa. White people are considered a homogenous group who are essentially racist and, in that sense, are considered unredeemable in efforts to address racism.

Garvey visited Nova Scotia twice, first in the 1920s, which led to a (UNIA) office in Cape Breton, and then the famous 1937 visit. He was initially drawn by the founding of an African Orthodox Church in Sydney in 1921 and maintained contact with the ex-pat West Indian community. The UNIA invited him to visit in 1937.Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, this separatist politics was reinforced again in the 1960s by the Black Power Movement and especially its militant subgroup the Black Panther Party.Black United Front

Black United Front also known as The Black United Front of Nova Scotia or simply BUF was a Black nationalist organization primarily based in Halifax, Nova Scotia during the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. Preceded by the Nova Scotia ...

(BUF). Black United Front was a Black nationalist

Black nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that black people are a race, and which seeks to develop and maintain a black racial and national identity. Black nationalist activism revolves aro ...

organization that included Burnley "Rocky" Jones and was loosely based on the 10 point program of the Black Panther Party. In 1968, Stokely Carmichael

Kwame Ture (; born Stokely Standiford Churchill Carmichael; June 29, 1941November 15, 1998) was a prominent organizer in the civil rights movement in the United States and the global pan-African movement. Born in Trinidad, he grew up in the Unite ...

, who coined the phrase ''Black Power!'', visited Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

helping organize the BUF.

Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia

Reverend William Oliver eventually left the BUF and became instrumental in establishing the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia, which opened in 1983. The organization houses a museum, library and archival area. Oliver designed the Black Cultural Centre to help all Nova Scotians become aware of how Black culture is woven into the heritage of the province. The centre also helps Nova Scotians trace their history of championing human rights and overcoming racism in the province. For his efforts in establishing the four leading organizations in the 20th century to support Black Nova Scotians and, ultimately, all Nova Scotians, William Oliver was awarded the Order of Canada

The Order of Canada (french: Ordre du Canada; abbreviated as OC) is a Canadian state order and the second-highest honour for merit in the system of orders, decorations, and medals of Canada, after the Order of Merit.

To coincide with the cen ...

in 1984.

Migration out of Nova Scotia

Beginning in the 1920s and 1930s, African Nova Scotians began leaving their settlements in order to find work in larger cities and towns such as Halifax, Sydney, Truro and New Glasgow. Many left Nova Scotia for cities such as Toronto and Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple ...

, while others left Canada altogether for the United States.

Bangor, Maine's lumber industry attracted Black people from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick for decades. They formed a sizeable community on the town's west end throughout the early-1900s. A small African Nova Scotian community had also developed in Sudbury in the late 1940s due to aggressive recruitment efforts in Black Nova Scotian settlements by Vale Inco

Vale Canada Limited (formerly Vale Inco, CVRD Inco and Inco Limited; for corporate branding purposes simply known as "Vale" and pronounced in English) is a wholly owned subsidiary of the Brazilian mining company Vale. Vale's nickel mining and ...

.

By the 1960s, a Black Nova Scotian neighbourhood had developed in Toronto, around the Kensington Market

Kensington Market is a distinctive multicultural neighbourhood in Downtown Toronto, Ontario, Canada. The Market is an older neighbourhood and one of the city's most well-known. In November 2006, it was designated a National Historic Site of Canad ...

- Alexandra Park area. First Baptist Church, the oldest Black institution in Toronto, became the spiritual centre of this community. In 1972, Alexandra Park is said to have had a Black Nova Scotian population of over 2,000 - making it more populous than any of the Black settlements in Nova Scotia at the time. Escaping rural communities with little education or skills, young Black Nova Scotians in Toronto faced high poverty and unemployment rates.

In 1977, between 1,200 and 2,400 Black Nova Scotians lived in Montreal. Though dispersed throughout the city, many settled among African-Americans and English-speaking West Indians in Little Burgundy

Little Burgundy (french: La Petite-Bourgogne) is a neighbourhood in the South West borough of the city of Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Geography

Its approximate boundaries are Atwater Avenue to the west, Saint-Antoine to the north, Guy Street ...

.

Dwayne Johnson

Dwayne Douglas Johnson (born May 2, 1972), also known by his ring name The Rock, is an American actor and former professional wrestler. Widely regarded as one of the greatest professional wrestlers of all time, he was integral to the develop ...

, Arlene Duncan, Beverly Mascoll

Beverly Mascoll (born Beverly Ashe, 1941-2001) was a Canadian businesswoman, fundraiser, community leader, and Member of the Order of Canada.

Early life and career

Beverly Ashe was born on October 29, 1942, in Fall River, Nova Scotia, to pare ...

, Tommy Kane, and Wayne Simmonds

Wayne Simmonds (born August 26, 1988) is a Canadian professional ice hockey player for the Toronto Maple Leafs of the National Hockey League (NHL). Simmonds has previously played for the Los Angeles Kings, Philadelphia Flyers, Nashville Predato ...

are examples of prominent individuals who have at least one Black Nova Scotian parent that settled outside the province.

21st century

Organizations

Several organizations have been created by Black Nova Scotians to serve the community. Some of these include the Black Educators Association of Nova Scotia, African Nova Scotian Music Association

African or Africans may refer to:

* Anything from or pertaining to the continent of Africa:

** People who are native to Africa, descendants of natives of Africa, or individuals who trace their ancestry to indigenous inhabitants of Africa

*** Ethn ...

, Health Association of African Canadians and the Black Business Initiative. Individuals involved in these and other organizations worked together with various officials to orchestrate the government apologies and pardons for past incidents of racial discrimination.

Africville Apology

The

The Africville Apology

The Africville Apology was a formal pronouncement delivered on 24 February 2010 by the City of Halifax, Nova Scotia for the eviction and eventual destruction of Africville, a Black Nova Scotian community.

Historical context

During the 1940s a ...

was delivered on February 24, 2010, by Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348 ...

, for the eviction and eventual destruction of Africville, a Black Nova Scotian community.

Viola Desmond pardon

On April 14, 2010, the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia, Mayann Francis

Mayann Elizabeth Francis, (born February 18, 1946) was the 31st Lieutenant Governor of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia.

Early life and education

Born in Sydney, Nova Scotia and raised in Whitney Pier, she is the daughter of Archpriest ...

, on the advice of her premier, invoked the Royal Prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, privilege and immunity, recognized in common law and, sometimes, in civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy, as belonging to the sovereign and which have become widely vested in th ...

and granted Viola Desmond

Viola Irene Desmond (July 6, 1914 – February 7, 1965) was a Canadian civil and women's rights activist and businesswoman of Black Nova Scotian descent. In 1946, she challenged racial segregation at a cinema in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia by refu ...

a posthumous

Posthumous may refer to:

* Posthumous award - an award, prize or medal granted after the recipient's death

* Posthumous publication – material published after the author's death

* ''Posthumous'' (album), by Warne Marsh, 1987

* ''Posthumous'' ...

free pardon, the first such to be granted in Canada. The free pardon, an extraordinary remedy granted under the Royal Prerogative of Mercy

In the English and British tradition, the royal prerogative of mercy is one of the historic royal prerogatives of the British monarch, by which they can grant pardons (informally known as a royal pardon) to convicted persons. The royal prer ...

only in the rarest of circumstances and the first one granted posthumously, differs from a simple pardon in that it is based on innocence and recognizes that a conviction was in error. The government of Nova Scotia also apologised. This initiative happened through Desmond's younger sister Wanda Robson, and a professor of Cape Breton University, Graham Reynolds, working with the Government of Nova Scotia to ensure that Desmond's name was cleared and the government admitted its error.

In honour of Desmond, the provincial government has named the first Nova Scotia Heritage Day

In most provinces of Canada, the third Monday in February is observed as a regional statutory holiday, typically known in general as Family Day (french: Jour de la famille)—though some provinces use their own names, as they celebrate the day fo ...

after her.

Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children apology

Children in an orphanage that opened in 1921, the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children

The Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children is an orphanage in Halifax, Nova Scotia that opened on June 6, 1921. It was built, because at the time, white home care institutions would not accept black children in need. In the 1960s segregation was c ...

, suffered physical, psychological and sexual abuse by staff over a 50-year period. Ray Wagner is the lead counsel for the former residents who successfully made a case against the orphanage. In 2014, the Premier of Nova Scotia Stephen McNeil wrote a letter of apology and about 300 claimants are to receive monetary compensation for their damages.

Immigration

Since the immigration reforms of the 1970s, a growing number of people of African descent have moved to Nova Scotia. Members of these groups are not considered a part of the distinct Black Nova Scotian community, although they are Black Canadian. The last group to be accepted as members of the Black Nova Scotian ethnic group are Bajans

Barbadians or Bajans

(pronounced ) are people who are identified with the country of Barbados, by being citizens or their descendants in the Barbadian diaspora. The connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Barba ...

who came to Cape Breton in the early 1900s, referred to as the "later arrivals".[Census Profile, 2016 Census]

Statistics Canada. Accessed on May 1, 2018.

Settlements

Black Nova Scotians were initially established in rural settings, which usually functioned independently until the 1960s. Black Nova Scotians in urban areas today still trace their roots to these rural settlements. Some of the settlements include: Gibson Woods, Greenville, Weymouth Falls,

Black Nova Scotians were initially established in rural settings, which usually functioned independently until the 1960s. Black Nova Scotians in urban areas today still trace their roots to these rural settlements. Some of the settlements include: Gibson Woods, Greenville, Weymouth Falls, Birchtown

Birchtown is a community and National Historic Site in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, located near Shelburne in the Municipal District of Shelburne County. Founded in 1783, the village was the largest settlement of Black Loyalists and ...

, East Preston, Cherrybrook, Lincolnville, Upper Big Tracadie, Five Mile Plains, North Preston, Tracadie, Shelburne, Lucasville, Beechville, and Hammonds Plains among others. Some have roots in other Black settlements located in New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island including Elm Hill, New Brunswick, Willow Grove (Saint John, NB) and The Bog (Charlottetown, PEI).

Prominent Black neighbourhoods exist in most towns and cities in Nova Scotia including Halifax, Truro

Truro (; kw, Truru) is a cathedral city and civil parish in Cornwall, England. It is Cornwall's county town, sole city and centre for administration, leisure and retail trading. Its population was 18,766 in the 2011 census. People of Truro ...

, New Glasgow

New Glasgow is a town in Pictou County, in the province of Nova Scotia, Canada. It is situated on the banks of the East River of Pictou, which flows into Pictou Harbour, a sub-basin of the Northumberland Strait.

The town's population was 9,075 ...

, Sydney, Digby, Shelburne and Yarmouth. Black neighbourhoods in Halifax include Uniacke Square and Mulgrave Park

Mulgrave Park is a residential neighbourhood in North End Halifax, Nova Scotia. It consists of local public housing along Barrington Street. It is also referred to as MGP by most residents.

The 351 unit development was completed in October 196 ...

. The ethnically diverse Whitney Pier

Whitney Pier (2016 population: 4,612) is an urban neighbourhood in Sydney, Nova Scotia, Canada. Prior to the 20th century, this area was known as “Eastmount” or “South Sydney Harbour,” and had long been a fishing and farming district. It i ...

neighborhood of Sydney has a significant Black population, first drawn there by the opening of the Dominion Iron and Steel Company

The Dominion Steel and Coal Corporation (also DOSCO) was a Canadian coal mining and steel manufacturing company.

Incorporated in 1928 and operational by 1930, DOSCO was predated by the British Empire Steel Corporation (BESCO), which was a merger o ...

steel mill in the early 20th century.

List of areas with Black populations higher than provincial average

Notable Black Nova Scotians

See also

*Indigenous Black Canadians

Indigenous Black Canadians is a term for people in Canada of African descent who have roots in Canada going back several generations. The term has been proposed to distinguish them from Black people with more recent immigrant roots. Popularized by ...

* Black Canadians in New Brunswick

* Thomas Peters, Black Loyalist who settled Nova Scotia

*'' The Book of Negroes'' (2007), novel based on the historic document of the same name

*''Poor Boy's Game

''Poor Boy's Game'' is a 2007 Canadian drama film directed by Clement Virgo. Co-written with Nova Scotian writer/director Chaz Thorne (''Just Buried''), it is the story of class struggle, racial tensions, and boxing, set in the Canadian east coas ...

''

*'' Speak It! From the Heart of Black Nova Scotia''

*'' Black Cop''

Sources

External links

Nova Scotia Archives & Records Management – African Nova Scotians

Further reading

*

*

*

*

History of the Maroons. 1803

* William Renwick Riddell. Slavery in the Maritime Provinces. ''The Journal of Negro History'', Vol. 5, No. 3 (July 1920), pp. 359–375

* Catherine Cottreau-Robins

"Timothy Ruggles – A Loyalist Plantation in Nova Scotia, 1784–1800"

Doctorate Thesis. Dalhousie University, 2012

*

* Allen Robertson, "Bondage and Freedom: Apprentices, Servants and Slaves in Colonial Nova Scotia"; Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society. Vol. #44 (1996); pp. 13.

* Wilson Head. "Discrimination Against Blacks in Nova Scotia: The Criminal Justice System" (1989).

*John Grant

"Black Immigration into Nova Scotia"

''Journal of Negro History'', 1973

The African in Canada; The Maroons of Jamaica and Nova Scotia (1890)Papers relative to the settling of the Maroons in His Majesty's province of Nova Scotia (1798)A brief history of the coloured Baptists of Nova Scotia and their first organization as churches, A.D. 1832 (1895)

{{People of Canada

*

Culture of Nova Scotia

African-American diaspora

Peoples of the African-American diaspora

History of Nova Scotia

Of the 10,000 French living at Louisbourg (1713–1760) and on the rest of Ile Royale, 216 were African-descended slaves. According to historian Kenneth Donovan, slaves on Ile Royal worked as "servants, gardeners, bakers, tavern keepers, stone masons, musicians, laundry workers, soldiers, sailors, fishermen, hospital workers, ferry men, executioners and nursemaids." More than 90 per cent of the enslaved people were Blacks from the French West Indies, which included Saint-Domingue, the chief sugar colony, and Guadeloupe.

Of the 10,000 French living at Louisbourg (1713–1760) and on the rest of Ile Royale, 216 were African-descended slaves. According to historian Kenneth Donovan, slaves on Ile Royal worked as "servants, gardeners, bakers, tavern keepers, stone masons, musicians, laundry workers, soldiers, sailors, fishermen, hospital workers, ferry men, executioners and nursemaids." More than 90 per cent of the enslaved people were Blacks from the French West Indies, which included Saint-Domingue, the chief sugar colony, and Guadeloupe.

The other significant Black Loyalist settlement is Tracadie. Led by Thomas Brownspriggs, Black Nova Scotians who had settled at Chedabucto Bay behind the present-day village of

The other significant Black Loyalist settlement is Tracadie. Led by Thomas Brownspriggs, Black Nova Scotians who had settled at Chedabucto Bay behind the present-day village of  The next major migration of Blacks into Nova Scotia occurred between 1813 and 1815. Black Refugees from the

The next major migration of Blacks into Nova Scotia occurred between 1813 and 1815. Black Refugees from the  Following Black Loyalist preacher David George, Baptist minister John Burton was one of the first ministers to integrate Black and white Nova Scotians into the same congregation.Burton, John

Following Black Loyalist preacher David George, Baptist minister John Burton was one of the first ministers to integrate Black and white Nova Scotians into the same congregation.Burton, John New Horizons Baptist Church (formerly known as Cornwallis Street Baptist Church, the African Chapel, and the African Baptist Church) is a

New Horizons Baptist Church (formerly known as Cornwallis Street Baptist Church, the African Chapel, and the African Baptist Church) is a  Numerous Black Nova Scotians fought in the

Numerous Black Nova Scotians fought in the  In 1894, an all-Black

In 1894, an all-Black  The No. 2 Construction Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), was the only predominantly Black

The No. 2 Construction Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), was the only predominantly Black  In keeping with the times, Reverend William Oliver began the

In keeping with the times, Reverend William Oliver began the  The

The  Black Nova Scotians were initially established in rural settings, which usually functioned independently until the 1960s. Black Nova Scotians in urban areas today still trace their roots to these rural settlements. Some of the settlements include: Gibson Woods, Greenville, Weymouth Falls,

Black Nova Scotians were initially established in rural settings, which usually functioned independently until the 1960s. Black Nova Scotians in urban areas today still trace their roots to these rural settlements. Some of the settlements include: Gibson Woods, Greenville, Weymouth Falls,