Black Hole of Calcutta on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Black Hole of Calcutta was a dungeon in Fort William, Calcutta, measuring , in which troops of

The Black Hole of Calcutta was a dungeon in Fort William, Calcutta, measuring , in which troops of

Holwell wrote about the events that occurred after the fall of Fort William. He met with Siraj-ud-Daulah, who assured him: "On the word of a soldier; that no harm should come to us". After seeking a place in the fort to confine the prisoners (including Holwell), at , the jailers stripped the prisoners of their clothes and locked the prisoners in the fort's prison—"the black hole" in soldiers' slang—a small room that measured . The next morning, when the black hole was opened, at , only about 23 of the prisoners remained alive.

Historians offer different numbers of prisoners and casualties of war; Stanley Wolpert reported that 64 people were imprisoned and 21 survived. D. L. Prior reported that 43 men of the Fort-William garrison were either missing or dead, for reasons other than suffocation and

Holwell wrote about the events that occurred after the fall of Fort William. He met with Siraj-ud-Daulah, who assured him: "On the word of a soldier; that no harm should come to us". After seeking a place in the fort to confine the prisoners (including Holwell), at , the jailers stripped the prisoners of their clothes and locked the prisoners in the fort's prison—"the black hole" in soldiers' slang—a small room that measured . The next morning, when the black hole was opened, at , only about 23 of the prisoners remained alive.

Historians offer different numbers of prisoners and casualties of war; Stanley Wolpert reported that 64 people were imprisoned and 21 survived. D. L. Prior reported that 43 men of the Fort-William garrison were either missing or dead, for reasons other than suffocation and

''In memoriam'' of the dead, the British erected a 15-metre (50') high

''In memoriam'' of the dead, the British erected a 15-metre (50') high

The Black Hole of Calcutta was a dungeon in Fort William, Calcutta, measuring , in which troops of

The Black Hole of Calcutta was a dungeon in Fort William, Calcutta, measuring , in which troops of Siraj-ud-Daulah

Mirza Muhammad Siraj-ud-Daulah ( fa, ; 1733 – 2 July 1757), commonly known as Siraj-ud-Daulah or Siraj ud-Daula, was the last independent Nawab of Bengal. The end of his reign marked the start of the rule of the East India Company over Beng ...

, the Nawab of Bengal, held British prisoners of war on the night of 20 June 1756. John Zephaniah Holwell, one of the British prisoners and an employee of the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

, said that, after the fall of Fort William, the surviving British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

soldiers, Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

sepoys, and Indian civilians were imprisoned overnight in conditions so cramped that many people died from suffocation and heat exhaustion Heat exhaustion is a severe form of heat illness. It is a medical emergency. Heat exhaustion is caused by the loss of water and electrolytes through sweating.

The United States Department of Labor makes the following recommendation, "Heat illness ...

, and that 123 of 146 prisoners of war imprisoned there died. Some modern historians believe that 64 prisoners were sent into the Hole, and that 43 died there.

Background

Fort William was established to protect theEast India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

's trade in the city of Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

, the principal city of the Bengal Presidency

The Bengal Presidency, officially the Presidency of Fort William and later Bengal Province, was a subdivision of the British Empire in India. At the height of its territorial jurisdiction, it covered large parts of what is now South Asia and ...

. In 1756 India, there existed the possibility of a battle with the military forces of the French East India Company

The French East India Company (french: Compagnie française pour le commerce des Indes orientales) was a colonial commercial enterprise, founded on 1 September 1664 to compete with the English (later British) and Dutch trading companies in th ...

, so the British reinforced the fort. Siraj-ud-daula ordered the fortification construction to be stopped by the French and British, and the French complied while the British demurred.

In consequence to that British indifference to his authority, Siraj ud-Daulah organised his army and laid siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characteriz ...

to Fort William. In an effort to survive the battle, the British commander ordered the surviving soldiers of the garrison to escape, yet left behind 146 soldiers under the civilian command of John Zephaniah Holwell, a senior bureaucrat

A bureaucrat is a member of a bureaucracy and can compose the administration of any organization of any size, although the term usually connotes someone within an institution of government.

The term ''bureaucrat'' derives from "bureaucracy", w ...

of the East India Company, who had been a military surgeon

''Military Medicine'' is a monthly peer-reviewed medical journal covering all aspects of medicine in military settings. It is published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Association of Military Surgeons of the United States. It was est ...

in earlier life.

The desertions of Indian sepoys made the British defence of Fort William ineffective and it fell to the siege of Bengali forces on 20 June 1756. The surviving defenders who were captured and made prisoners of war numbered between 64 and 69, along with an unknown number of Anglo-Indian

Anglo-Indian people fall into two different groups: those with mixed Indian and British ancestry, and people of British descent born or residing in India. The latter sense is now mainly historical, but confusions can arise. The '' Oxford English ...

soldiers and civilians who earlier had been sheltered in Fort William. The English officers and merchants based in Kolkata

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, comme ...

were rounded up by the forces loyal to Siraj ud-Daulah and forced into a dungeon known as the "Black Hole".

The Holwell account

Holwell wrote about the events that occurred after the fall of Fort William. He met with Siraj-ud-Daulah, who assured him: "On the word of a soldier; that no harm should come to us". After seeking a place in the fort to confine the prisoners (including Holwell), at , the jailers stripped the prisoners of their clothes and locked the prisoners in the fort's prison—"the black hole" in soldiers' slang—a small room that measured . The next morning, when the black hole was opened, at , only about 23 of the prisoners remained alive.

Historians offer different numbers of prisoners and casualties of war; Stanley Wolpert reported that 64 people were imprisoned and 21 survived. D. L. Prior reported that 43 men of the Fort-William garrison were either missing or dead, for reasons other than suffocation and

Holwell wrote about the events that occurred after the fall of Fort William. He met with Siraj-ud-Daulah, who assured him: "On the word of a soldier; that no harm should come to us". After seeking a place in the fort to confine the prisoners (including Holwell), at , the jailers stripped the prisoners of their clothes and locked the prisoners in the fort's prison—"the black hole" in soldiers' slang—a small room that measured . The next morning, when the black hole was opened, at , only about 23 of the prisoners remained alive.

Historians offer different numbers of prisoners and casualties of war; Stanley Wolpert reported that 64 people were imprisoned and 21 survived. D. L. Prior reported that 43 men of the Fort-William garrison were either missing or dead, for reasons other than suffocation and shock

Shock may refer to:

Common uses Collective noun

*Shock, a historic commercial term for a group of 60, see English numerals#Special names

* Stook, or shock of grain, stacked sheaves

Healthcare

* Shock (circulatory), circulatory medical emergen ...

. Busteed reports that the many non-combatants present in the fort when it was captured make infeasible a precise number of people killed. Regarding responsibility for the maltreatment and the deaths in the Black Hole of Calcutta, Holwell said, "it was the result of revenge and resentment, in the breasts of the lower '' Jemmaatdaars'' ergeants to whose custody we were delivered, for the number of their order killed during the siege."

Concurring with Holwell, Wolpert said that Siraj-ud-Daulah did not order the imprisonment and was not informed of it. The physical description of the Black Hole of Calcutta corresponds with Holwell's point of view:

Afterward, when the prison of Fort William was opened, the corpses of the dead men were thrown into a ditch. As prisoners of war, Holwell and three other men were transferred to Murshidabad

Murshidabad fa, مرشد آباد (, or ) is a historical city in the Indian state of West Bengal. It is located on the eastern bank of the Bhagirathi River, a distributary of the Ganges. It forms part of the Murshidabad district.

Durin ...

.

Imperial aftermath

The remaining survivors of the Black Hole of Calcutta were freed the next morning on the orders of the nawab, who learned only that morning of their sufferings. After news of Calcutta's capture was received by the British in Madras in August 1756, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Clive was sent to retaliate against the Nawab. With his troops and local Indian allies, Clive recaptured Calcutta in January 1757, and defeated Siraj ud-Daulah at the Battle of Plassey, which resulted in Siraj being overthrown as Nawab of Bengal and executed. The Black Hole of Calcutta was later used as a warehouse.Monument to the victims

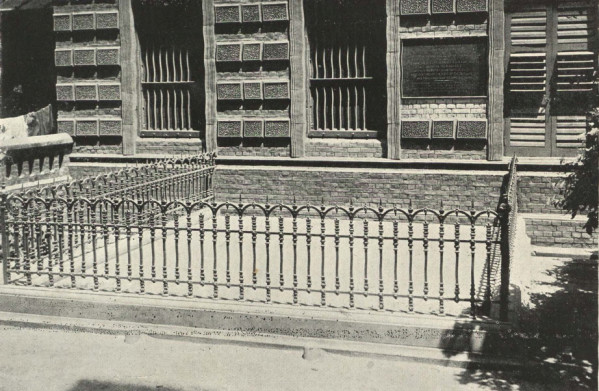

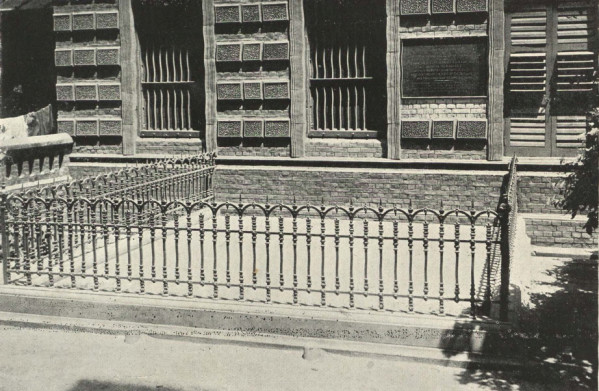

''In memoriam'' of the dead, the British erected a 15-metre (50') high

''In memoriam'' of the dead, the British erected a 15-metre (50') high obelisk

An obelisk (; from grc, ὀβελίσκος ; diminutive of ''obelos'', " spit, nail, pointed pillar") is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. Originally constructed by An ...

; it now is in the graveyard of (Anglican) St. John's Church, Calcutta. Holwell had erected a tablet on the site of the 'Black Hole' to commemorate the victims but, at some point (the precise date is uncertain), it disappeared. Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), styled Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911 and then Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, was a British Conservative statesman ...

, on becoming Viceroy in 1899, noticed that there was nothing to mark the spot and commissioned a new monument, mentioning the prior existence of Holwell's; it was erected in 1901 at the corner of Dalhousie Square (now B. B. D. Bagh

B. B. D. Bagh, formerly called Tank Square and then Dalhousie Square (1847 to 1856), is the shortened version for Benoy-Badal-Dinesh Bagh. It is the seat of power of the state government, as well as the central business district of Kolkata in ...

), which is said to be the site of the 'Black Hole'. At the apex of the Indian independence movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British rule in India. It lasted from 1857 to 1947.

The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged ...

, the presence of this monument in Calcutta was turned into a nationalist ''cause célèbre

A cause célèbre (,''Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged'', 12th Edition, 2014. S.v. "cause célèbre". Retrieved November 30, 2018 from https://www.thefreedictionary.com/cause+c%c3%a9l%c3%a8bre ,''Random House Kernerman Webs ...

''. Nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

leaders, including Subhas Chandra Bose, lobbied energetically for its removal. The Congress and the Muslim League Muslim League may refer to:

Political parties Subcontinent

; British India

*All-India Muslim League, Mohammed Ali Jinah, led the demand for the partition of India resulting in the creation of Pakistan.

**Punjab Muslim League, a branch of the organ ...

joined forces in the anti-monument movement. As a result, Abdul Wasek Mia of Nawabganj thana, a student leader of that time, led the removal of the monument from Dalhousie Square in July 1940. The monument was re-erected in the graveyard of St John's Church, Calcutta, where it remains.

The 'Black Hole' itself, being merely the guardroom in the old Fort William, disappeared shortly after the incident when the fort itself was taken down to be replaced by the new Fort William which still stands today in the Maidan to the south of B.B.D. Bagh. The precise location of that guardroom is in an alleyway between the General Post Office and the adjacent building to the north, in the north west corner of B.B.D. Bagh. The memorial tablet which was once on the wall of that building beside the GPO can now be found in the nearby postal museum.

"List of the smothered in the Black Hole prison exclusive of sixty-nine, consisting of Dutch and British sergeants, corporal

Corporal is a military rank in use in some form by many militaries and by some police forces or other uniformed organizations. The word is derived from the medieval Italian phrase ("head of a body"). The rank is usually the lowest ranking non- ...

s, soldiers, topazes, militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

, whites, and Portuguese, (whose names I am unacquainted with), making on the whole one hundred and twenty-three persons."

Holwell's list of the victims of the Black Hole of Calcutta:

In popular culture

Literature

Muriel Rukeyser

Muriel Rukeyser (December 15, 1913 – February 12, 1980) was an American poet and political activist, best known for her poems about equality, feminism, social justice, and Judaism. Kenneth Rexroth said that she was the greatest poet of her "e ...

, in ''The Book of the Dead'', originally published as a group of poems in ''U.S. 1: Poems'' (1938)'','' quotes from Vito Marcantonio

Vito is an Italian name that is derived from the Latin word "''vita''", meaning "life".

It is a modern form of the Latin name Vitus, meaning "life-giver," as in San Vito or Saint Vitus, the patron saint of dogs and a heroic figure in southern I ...

's speech "Dusty Death" (1936). Rukeyser was writing about the Hawk's Nest Tunnel tragedy and referenced to Marcantonio's speech to compare the silicate tunnels to the Black Holes of Calcutta, writing "This is the place. Away from this my life I am indeed Adam unparadiz'd. Some fools call this the Black Hole of Calcutta. I don't know how they ever get to Congress."

Thomas Pynchon

Thomas Ruggles Pynchon Jr. ( , ; born May 8, 1937) is an American novelist noted for his dense and complex novels. His fiction and non-fiction writings encompass a vast array of subject matter, genres and themes, including history, music, scie ...

refers to the Black Hole of Calcutta in the historical novel '' Mason & Dixon'' (1997). The character Charles Mason

Charles Mason (April 1728Saint Helena with the astronomer

The Black Hole of Calcutta & The End of Islamic Power in India (1756—1757)

''The Black Hole of Empire''

– Stanford Presidential Lecture by Partha Chatterjee

Photo of Calcutta Black Hole Memorial at St. John's Church Complex, Calcutta

* Partha Chatterjee and Ayça Çubukçu, "Empire as a Practice of Power: Introduction," ''The Asia-Pacific Journal'', Vol 10, Issue 41, No. 1, 9 October 2012

Interview with Chatterjee. * *The Black Hole of Calcutta—-the Fort William's airtight deat

prison

* {{Authority control 1756 in British India 18th century in Kolkata Buildings and structures in Kolkata Prisoner of war massacres Massacres in India Massacres in 1756 Mass murder in 1756 1756 murders in Asia 18th-century murders in India

Nevil Maskelyne

Nevil Maskelyne (; 6 October 1732 – 9 February 1811) was the fifth British Astronomer Royal. He held the office from 1765 to 1811. He was the first person to scientifically measure the mass of the planet Earth. He created the ''British Nau ...

, the brother-in-law of Lord Robert Clive of India. Later in the story, Jeremiah Dixon

Jeremiah Dixon FRS (27 July 1733 – 22 January 1779) was an English surveyor and astronomer who is best known for his work with Charles Mason, from 1763 to 1767, in determining what was later called the Mason–Dixon line.

Early life and ...

visits New York City, and attends a secret "Broad-Way" production of the "musical drama", ''The Black Hole of Calcutta, or, the Peevish Wazir'', "executed with such a fine respect for detail ...". Kenneth Tynan

Kenneth Peacock Tynan (2 April 1927 – 26 July 1980) was an English theatre critic and writer. Making his initial impact as a critic at ''The Observer'', he praised Osborne's ''Look Back in Anger'' (1956), and encouraged the emerging wave of ...

satirically refers to it in the long-running musical revue ''Oh! Calcutta!

''Oh! Calcutta!'' is an avant-garde, risque theatrical revue created by British drama critic Kenneth Tynan. The show, consisting of sketches on sex-related topics, debuted Off-Broadway in 1969 and then in the West End in 1970. It ran in Lond ...

'', which was played on Broadway for more than 7,000 performances. Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wid ...

makes reference to the "stifling" of the prisoners in the introduction to " The Premature Burial" (1844). The Black Hole is mentioned in ''Looking Backward

''Looking Backward: 2000–1887'' is a utopian science fiction novel by Edward Bellamy, a journalist and writer from Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts; it was first published in 1888.

The book was translated into several languages, and in short o ...

'' (1888) by Edward Bellamy

Edward Bellamy (March 26, 1850 – May 22, 1898) was an American author, journalist, and political activist most famous for his utopian novel ''Looking Backward''. Bellamy's vision of a harmonious future world inspired the formation of numerou ...

as an example of the depravity of the past.

In a story written by Indian author Masti Venkatesha Iyengar

Masti Venkatesha Iyengar (6 June 1891 – 6 June 1986) was a well-known writer in Kannada language. He was the fourth among Kannada writers to be honored with the Jnanpith Award, the highest literary honor conferred in India. He was popularly re ...

, "Rangana Maduve" ("Ranga's Marriage"), the narrator Shyama describes Ranga's house as 'the Black Hole of Calcutta' because of the large crowd that had gathered to see Ranga when he came home after completing his studies. If all the people had gone inside, the house would have become as crowded as the Black Hole of Calcutta.

In the science-fiction novel '' Omega: The Last Days of the World'' (1894), by Camille Flammarion

Nicolas Camille Flammarion FRAS (; 26 February 1842 – 3 June 1925) was a French astronomer and author. He was a prolific author of more than fifty titles, including popular science works about astronomy, several notable early science fic ...

, the Black Hole of Calcutta is mentioned for the suffocating properties of Carbonic-Oxide (Carbon Monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simple ...

) upon the British soldiers imprisoned in that dungeon. Eugene O'Neill

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright and Nobel laureate in Nobel Prize in Literature, literature. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama tech ...

, in '' Long Day's Journey into Night'', Act 4, Jamie says, "Can't expect us to live in the Black Hole of Calcutta." Patrick O'Brian

Patrick O'Brian, CBE (12 December 1914 – 2 January 2000), born Richard Patrick Russ, was an English novelist and translator, best known for his Aubrey–Maturin series of sea novels set in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars, and cent ...

in '' The Mauritius Command'' (1977) compared Jack Aubrey's house to the black hole of Calcutta "except that whereas the Hole was hot, dry, and airless", Aubrey's cottage "let in draughts from all sides".

In Chapter VII of Pearl S. Buck

Pearl Sydenstricker Buck (June 26, 1892 – March 6, 1973) was an American writer and novelist. She is best known for ''The Good Earth'' a bestselling novel in the United States in 1931 and 1932 and won the Pulitzer Prize for the Novel, Pulitze ...

’s biography of her father, ''Fighting Angel

''Fighting Angel: Portrait of a Soul'' (1936) is a memoir, sometimes called a "creative non-fiction novel," written by Pearl S. Buck about her father, Absalom Sydenstricker (1852–1931) as a companion to her memoir of her mother, ''The Exile''. ...

'' (1936), she compares the brutality of China’s 1899-1901 Boxer Rebellion (which she and her family survived while living in China) to that of the Black Hole of Calcutta: "The story of the Boxer Rebellion ... remains, like the tale of the Black Hole of Calcutta, one of the festering spots of history. If the number of people actually dead was small, as such numbers go in these days of wholesale death by accidents and wars, it was the manner of death ....that makes the heart shudder and condemn even while the mind can reason and weigh."

Diana Gabaldon

Diana J. Gabaldon (; born January 11, 1952) is an American author, known for the ''Outlander'' series of novels. Her books merge multiple genres, featuring elements of historical fiction, romance, mystery, adventure and science fiction/fantas ...

mentions briefly the incident in her novel '' Lord John and the Private Matter'' (2003). The Black Hole is also compared with the evil miasma of Calcutta as a whole in Dan Simmons's novel ''The Song of Kali''. Stephen King makes a reference to the Black Hole of Calcutta in his 1983 novel ''Christine

Christine may refer to:

People

* Christine (name), a female given name

Film

* ''Christine'' (1958 film), based on Schnitzler's play ''Liebelei''

* ''Christine'' (1983 film), based on King's novel of the same name

* ''Christine'' (1987 fil ...

'', and his 2004 novel '' Song of Susannah''.

In Chapter V of ''King Solomon's Mines

''King Solomon's Mines'' (1885) is a popular novel by the English Victorian adventure writer and fabulist Sir H. Rider Haggard. It tells of a search of an unexplored region of Africa by a group of adventurers led by Allan Quatermain for the ...

'' by H. Rider Haggard (1885) the Black Hole of Calcutta is mentioned: "This gave us some slight shelter from the burning rays of the sun, but the atmosphere in that amateur grave can be better imagined than described. The Black Hole of Calcutta must have been a fool to it". In John Fante

John Fante (April 8, 1909 – May 8, 1983) was an American novelist, short story writer, and screenwriter. He is best known for his semi-autobiographical novel ''Ask the Dust'' (1939) about the life of Arturo Bandini, a struggling writer in Depre ...

's novel '' The Road to Los Angeles'' (1985), the main character Arturo Bandini recalls when seeing his place of work: "I thought about the Black Hole of Calcutta." In '' Vanity Fair'', William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray (; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was a British novelist, author and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1848 novel ''Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and t ...

makes a reference to the Black Hole of Calcutta when describing the Anglo-Indian district in London (Chapter LX). Swami Vivekananda makes a mention of the Black Hole of Calcutta in connection with describing Holwell's journey to Murshidabad

Murshidabad fa, مرشد آباد (, or ) is a historical city in the Indian state of West Bengal. It is located on the eastern bank of the Bhagirathi River, a distributary of the Ganges. It forms part of the Murshidabad district.

Durin ...

.

When discussing deep unconsciousness in her book '' How to be Human'', Ruby Wax

Ruby Wax (; born 19 April 1953) is an American-British actress, comedian, writer, television personality, and mental health campaigner. A classically-trained actress, Wax was with the Royal Shakespeare Company for five years and co-starred on t ...

describes this as: "It's like the black hole of Calcutta of our souls."

In ''Hellblazer

''John Constantine, Hellblazer'' is an American contemporary horror comic-book series published by DC Comics since January 1988, and subsequently by its Vertigo imprint since March 1993, when the imprint was introduced. Its central character is ...

: Event Horizon'', John Constantine

John Constantine () is a fictional character who appears in American comic books published by DC Comics. Constantine first appeared in ''Swamp Thing'' #37 (June 1985), and was created by Alan Moore, Stephen R. Bissette, Rick Veitch, and John Tot ...

says that a mad Brahmin in the Black Hole made a stone because he wanted revenge. The stone causes one to have insane thoughts and hallucinations.

In '' The Other Side of Morning'' by Stephen Goss (2022), the events of the Black Hole of Calcutta are described from the perspective of John Holwell. The book is the story of Holwell's life leading up to the incident.

Television

In the period drama '' Turn: Washington's Spies'', the character ofJohn Graves Simcoe

John Graves Simcoe (25 February 1752 – 26 October 1806) was a British Army general and the first lieutenant governor of Upper Canada from 1791 until 1796 in southern Ontario and the watersheds of Georgian Bay and Lake Superior. He founded Yor ...

claims in Season 4 that he was born in India and that his father died in the Black Hole of Calcutta after being torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. definitions of tortur ...

d. (In historical reality, Simcoe was born in England and his father died of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

.)

In an episode of the British sitcom ''Open All Hours

''Open All Hours'' is a British television sitcom created and written by Roy Clarke for the BBC. It ran for 26 episodes in four series, which aired in 1976, 1981, 1982 and 1985. The programme developed from a television pilot broadcast in Ronn ...

'' Arkwright orders his assistant and nephew Granville to clean the outside window ledge. He attempts to say "There's enough dirt there to fill the Black Hole of Calcutta", but his extensive stuttering when trying to say 'Calcutta' causes him to change it to "There's enough dirt there to fill the Hanging Gardens of Babylon".

In an episode of British sitcom ''Only Fools and Horses

''Only Fools and Horses....'' is a British television sitcom created and written by John Sullivan (writer), John Sullivan. Seven series were originally broadcast on BBC One in the United Kingdom from 1981 to 1991, with sixteen sporadic Christmas ...

'', while discussing Uncle Albert's history of falling down numerous holes, Del Boy infers that the only hole Albert has not fallen down is "the black one in Calcutta".

In an episode of ''The Andy Griffith Show

''The Andy Griffith Show '' is an American situation comedy television series that aired on CBS from October 3, 1960, to April 1, 1968, with a total of 249 half-hour episodes spanning eight seasons—159 in black and white and 90 in color.

The ...

'', S. 6 Ep. 11 " The Cannon", Deputy Warren is placed in charge of security at the Mayberry Founders Day ceremony and he becomes obsessed with the town decorative cannon. He peers into the fuse breach and claims "It is darker than the Hole of Calcutta in there".

In an episode of ''The L Word

''The L Word'' is a television drama that aired on Showtime from January 18, 2004 to March 8, 2009. The series follows the lives of a group of lesbian and bisexual women who live in West Hollywood, California. The premise originated with Ilene ...

'', Alice refers to the bad vibes in the coffee shop as "The Black Hole of Calcutta".

In an episode of British television series ''Yes, Minister

''Yes Minister'' is a British political satire sitcom written by Antony Jay and Jonathan Lynn. Comprising three seven-episode series, it was first transmitted on BBC2 from 1980 to 1984. A sequel, ''Yes, Prime Minister'', ran for 16 episodes fr ...

'', the permanent secretary refers to a packed train compartment as the Black Hole of Calcutta.

In an episode of '' Have Gun, Will Travel'', S. 2 Ep. 10 "The Lady", Paladin warns a British woman of the danger of an imminent Comanche attack by reminding her of indigenous reprisals in India, including "the Khyber Pass, the Sepoy Mutiny, and the Black Hole of Calcutta".

In an episode of the British comedy ''Peep Show'', the character Mark says "The more, the merrier, they said as another poor soul was crammed into the Black Hole of Calcutta."

Film

The Black Hole of Calcutta is referenced early in the film '' Albert R.N.'', a 1953 British film dealing with a German prisoner-of-war camp for allied naval officers. In the 1963 episode of ''Steptoe and Son'' entitled ‘The Bath’, when Harold Steptoe displaces his father from his bedroom in order to install a bathroom, Albert Steptoe angrily describes his new ‘bedroom’ - the cupboard under the stairs - as being ''“…like the Black 'Ole of Calcutta!”'' There's also a reference in the 1987 film Hiding Out, where the protagonist's aunt criticizes her teenage son's messy room by comparing it to the Black Hole. It is also referenced in the 1991 film ''The Addams Family'' as one of the locations visited by Gomez and Morticia Addams during their second honeymoon.Astronomy

According to Hong-Yee Chiu, an astrophysicist atNASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil List of government space agencies, space program ...

, the Black Hole of Calcutta was the inspiration for the term '' black hole'' referring to objects resulting from the gravitational collapse of very heavy stars. He recalled hearing physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

Robert Dicke

Robert Henry Dicke (; May 6, 1916 – March 4, 1997) was an American astronomer and physicist who made important contributions to the fields of astrophysics, atomic physics, cosmology and gravity. He was the Albert Einstein Professor in Scienc ...

in the early 1960s compare such gravitationally collapsed objects to the prison.

Prison reform

A minority opinion in the August 1910 report of the Penitentiary Investigating Committee of the State of Texas (USA) referred to the prison conditions in this way:See also

*Human rights violation

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hum ...

*Hỏa Lò Prison

Hỏa Lò Prison (, Nhà tù Hỏa Lò; french: Prison Hỏa Lò) was a prison in Hanoi originally used by the French colonists in Indochina for political prisoners, and later by North Vietnam for U.S. prisoners of war during the Vietnam War. ...

Notes

References

* Noel Barber. ‘’The Black Hole of Calcutta: A Reconstruction,’’ London, Suttonn Publishing Ltd.,U.K. Edition, 2003. 272 p. . * Partha Chatterjee. ''The Black Hole of Empire: History of a Global Practice of Power''. Princeton, N.J.:Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is an independent publisher with close connections to Princeton University. Its mission is to disseminate scholarship within academia and society at large.

The press was founded by Whitney Darrow, with the financia ...

, 2012. 425p. . Explores the incident itself and the history of using it to expand or critique British rule in India.

* Urs App (2010). ''The Birth of Orientalism''. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

The University of Pennsylvania Press (or Penn Press) is a university press affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The press was originally incorporated with the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania on 26 M ...

(); contains a 66-page chapter (pp. 297–362) on Holwell.

*

*

External links

The Black Hole of Calcutta & The End of Islamic Power in India (1756—1757)

''The Black Hole of Empire''

– Stanford Presidential Lecture by Partha Chatterjee

Photo of Calcutta Black Hole Memorial at St. John's Church Complex, Calcutta

* Partha Chatterjee and Ayça Çubukçu, "Empire as a Practice of Power: Introduction," ''The Asia-Pacific Journal'', Vol 10, Issue 41, No. 1, 9 October 2012

Interview with Chatterjee. * *The Black Hole of Calcutta—-the Fort William's airtight deat

prison

* {{Authority control 1756 in British India 18th century in Kolkata Buildings and structures in Kolkata Prisoner of war massacres Massacres in India Massacres in 1756 Mass murder in 1756 1756 murders in Asia 18th-century murders in India