Bernard Spilsbury on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Bernard Henry Spilsbury (16 May 1877 – 17 December 1947) was a

The case that brought Spilsbury to public attention was that of

The case that brought Spilsbury to public attention was that of

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

pathologist

Pathology is the study of the causal, causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when us ...

. His cases include Hawley Crippen, the Seddon case, the Major Armstrong poisoning, the "Brides in the Bath" murders by George Joseph Smith

George Joseph Smith (11 January 1872 – 13 August 1915) was an English serial killer and bigamist who was convicted and subsequently hanged for the murders of three women in 1915, the case becoming known as the Brides in the Bath Murders. As w ...

, the Crumbles murders

The Crumbles Murders are two separate and unrelated crimes which occurred on a shingle beach located between Eastbourne and Pevensey Bay, England—locally referred to as "the Crumbles"—in the 1920s. The first of these two murders is the 1920 bl ...

, the Podmore case, the Sidney Harry Fox

Sidney Harry Fox (1899 – 8 April 1930) was a British petty swindler and convicted murderer. He was executed for the murder of his mother in an attempt to obtain money from an insurance policy on her life. His case is unusual in that it is a rar ...

matricide, the Vera Page

Vera may refer to:

Names

* Vera (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

*Vera (given name), a given name (including a list of people and fictional characters with the name)

**Vera (), archbishop of the archdiocese of Tarr ...

case, and the murder trials of Louis Voisin, Jean-Pierre Vaquier

Jean-Pierre Vaquier (14 July 1879 – 17 August 1924) was a French inventor and murderer. He was convicted in Britain of murdering the husband of his mistress by poisoning him with strychnine.

Vaquier was born in Niort-de-Sault on Bastille Da ...

, Norman Thorne

Norman Thorne (c. 1902 – 22 April 1925) was an England, English Sunday school teacher and chicken farmer who was convicted and hanged for what became known as the chicken run murder.

, Donald Merrett

John Donald Merrett (1908–1954) was a British murderer and convicted fraudster also known under the name of Ronald John Chesney in later life. He left a wide trail of damage with him escaping with minimal punishment. Despite being immense ...

, Alfred Rouse

Alfred Arthur Rouse (6 April 1894 – 10 March 1931) was a British murderer, known as the Blazing Car Murderer, who was convicted and subsequently hanged at Bedford Gaol for the November 1930 murder of an unknown man in Hardingstone, Northampto ...

, Elvira Barney

Elvira Enid Barney (née Mullens; ) was an English socialite and actress known professionally as Dolores Ashley. She was tried for the murder of her lover, Michael Scott Stephen, in 1932. The trial was widely reported by the British press. She wa ...

, Toni Mancini, and Gordon Cummins

Gordon Frederick Cummins (18 February 1914 – 25 June 1942) was a British serial killer known as the Blackout Killer, the Blackout Ripper and the Wartime Ripper, who murdered four women and attempted to murder two others over a six-day period i ...

. Spilsbury's courtroom appearances became legendary for his demeanour of effortless dominance.

He also played a crucial role in the development of Operation Mincemeat

Operation Mincemeat was a successful British deception operation of the Second World War to disguise the 1943 Allied invasion of Sicily. Two members of British intelligence obtained the body of Glyndwr Michael, a tramp who died from eating ...

, a deception operation during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

which saved thousands of lives of Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

service personnel. Spilsbury died by suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

in 1947.

Personal life

Spilsbury was born on 16 May 1877 at 35 Bath Street,Leamington Spa

Royal Leamington Spa, commonly known as Leamington Spa or simply Leamington (), is a spa town and civil parish in Warwickshire, England. Originally a small village called Leamington Priors, it grew into a spa town in the 18th century following ...

, Warwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a county in the West Midlands region of England. The county town is Warwick, and the largest town is Nuneaton. The county is famous for being the birthplace of William Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avon an ...

. He was the eldest of the four children of James Spilsbury, a manufacturing chemist, and his wife, Marion Elizabeth Joy.

On 3 September 1908, Spilsbury married Edith Caroline Horton. They had four children together: one daughter, Evelyn and three sons, Alan, Peter and Richard. Peter, a junior doctor at St Thomas's Hospital

St Thomas' Hospital is a large NHS teaching hospital in Central London, England. It is one of the institutions that compose the King's Health Partners, an academic health science centre. Administratively part of the Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foun ...

in Lambeth, was killed in the Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

in 1940, while Alan died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

in 1945, shortly after the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

The deaths (of Peter, in particular) were a blow from which Spilsbury never truly recovered. Depression over his finances and his declining health are believed to have been a key factor in his decision to commit suicide by gas in his laboratory at University College, London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = � ...

, in 1947. (requires login or UK library card)

Career

Educated atMagdalen College, Oxford

Magdalen College (, ) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. It was founded in 1458 by William of Waynflete. Today, it is the fourth wealthiest college, with a financial endowment of £332.1 million as of 2019 and one of the s ...

, he took a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four years ...

degree in natural science in 1899, an MB BCh in 1905 and a Master of Arts in 1908. He also studied at St Mary's Hospital in Paddington

Paddington is an area within the City of Westminster, in Central London. First a medieval parish then a metropolitan borough, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Three important landmarks of the district are Paddi ...

, London, from 1899. He specialised in the then-new science of forensic pathology

Forensic pathology is pathology that focuses on determining the cause of death by examining a corpse. A post mortem examination is performed by a medical examiner or forensic pathologist, usually during the investigation of criminal law cases an ...

.

In October 1905, he was appointed resident assistant pathologist at St Mary's Hospital when the London County Council

London County Council (LCC) was the principal local government body for the County of London throughout its existence from 1889 to 1965, and the first London-wide general municipal authority to be directly elected. It covered the area today kno ...

requested all general hospitals in its area appoint two qualified pathologists to perform autopsies following sudden deaths. In this capacity, he worked closely with coroners such as Bentley Purchase

Sir William Bentley Purchase (31 December 1890 – 27 September 1961) was a British physician and barrister. He pursued a career in medical examination and served, from 1930 to 1958, as the coroner with jurisdiction over much of London. He is b ...

.

Important cases

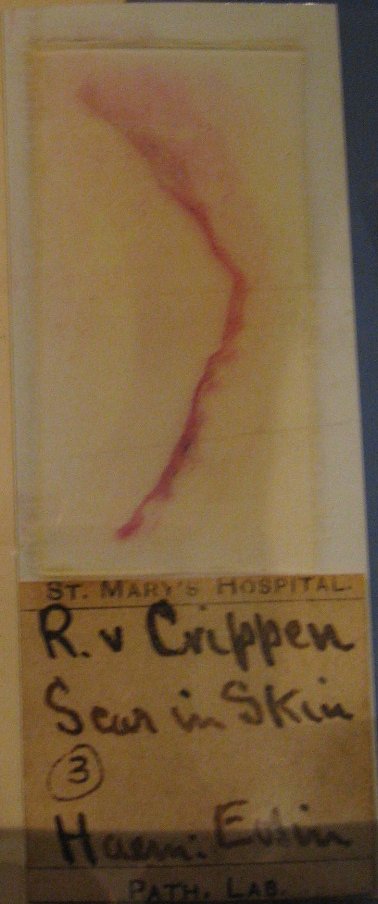

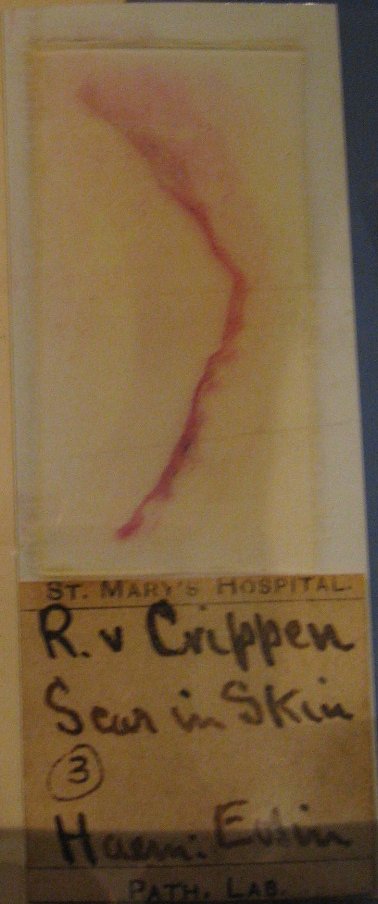

The case that brought Spilsbury to public attention was that of

The case that brought Spilsbury to public attention was that of Hawley Harvey Crippen

Hawley Harvey Crippen (September 11, 1862 – November 23, 1910), usually known as Dr. Crippen, was an American homeopath, ear and eye specialist and medicine dispenser. He was hanged in Pentonville Prison in London for the murder of his wife Co ...

in 1910, where he gave forensic evidence as to the likely identity of the human remains found in Crippen's house. Spilsbury concluded that a scar on a small piece of skin from the remains pointed to Mrs Crippen as the victim.

Spilsbury later gave evidence at the trial of Herbert Rowse Armstrong

Herbert Rowse Armstrong TD MA (13 May 1869 – 31 May 1922) was an English solicitor and convicted murderer, the only solicitor in the history of the United Kingdom to have been hanged for murder. He was living in Cusop Dingle, Herefordshi ...

, the solicitor convicted of poisoning his wife with arsenic.

The case that consolidated Spilsbury's reputation as Britain's foremost forensic pathologist was the "Brides in the Bath" murder trial in 1915. Three women had died mysteriously in their baths; in each case, the death appeared to be an accident. George Joseph Smith

George Joseph Smith (11 January 1872 – 13 August 1915) was an English serial killer and bigamist who was convicted and subsequently hanged for the murders of three women in 1915, the case becoming known as the Brides in the Bath Murders. As w ...

was brought to trial for the murder of one of these women, Bessie Munday. Spilsbury testified that since Munday's thigh showed evidence of goose bumps and, since she was, in death, clutching a bar of soap, it was certain that she had died a violent deathin other words, had been murdered.

Spilsbury was also involved in the Brighton trunk murder cases. Although the man accused of the second murder, Tony Mancini (real name Cecil Louis England), was acquitted, he confessed to the killing in 1976 just before his own death, vindicating Spilsbury's evidence.

Spilsbury was able to work with minimal remains, such as those involved in the Alfred Rouse

Alfred Arthur Rouse (6 April 1894 – 10 March 1931) was a British murderer, known as the Blazing Car Murderer, who was convicted and subsequently hanged at Bedford Gaol for the November 1930 murder of an unknown man in Hardingstone, Northampto ...

case (the "Blazing Car Murder"). Here, a near-destroyed body was found in the wreck of a burnt-out car near Northampton in 1930. Although the victim was never identified, Spilsbury was able to give evidence of how he had died and facilitate Rouse's conviction.

During his career, Spilsbury performed thousands of autopsies, not only of murder victims but also of executed criminals. He was able to appear for the defence in Scotland, where his status as a Home Office pathologist in England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. The substantive law of the jurisdiction is Eng ...

was irrelevant: he testified for the defence in the case of Donald Merrett

John Donald Merrett (1908–1954) was a British murderer and convicted fraudster also known under the name of Ronald John Chesney in later life. He left a wide trail of damage with him escaping with minimal punishment. Despite being immense ...

, tried in February 1927 for the murder of his mother and acquitted as not proven

Not proven (, ) is a verdict available to a Courts of Scotland, court of law in Scotland. Under Scots law, a Criminal procedure, criminal trial may end in one of three verdicts, one of conviction ("guilty") and two of acquittal ("not proven" and ...

.

Spilsbury was knighted early in 1923. He was a Home Office-approved pathologist and lecturer in forensic medicine at the University College Hospital

University College Hospital (UCH) is a teaching hospital in the Fitzrovia area of the London Borough of Camden, England. The hospital, which was founded as the North London Hospital in 1834, is closely associated with University College London ...

, the London School of Medicine for Women

The London School of Medicine for Women (LSMW) established in 1874 was the first medical school in Britain to train women as doctors. The patrons, vice-presidents, and members of the committee that supported and helped found the London School of Me ...

and at St Thomas's Hospital. He also was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine

The Royal Society of Medicine (RSM) is a medical society in the United Kingdom, headquartered in London.

History

The Society was established in 1805 as Medical and Chirurgical Society of London, meeting in two rooms in barristers’ chambers ...

.

In later years, Spilsbury's dogmatic manner and his unbending belief in his own infallibility gave rise to criticism. Judges began to express concern about his invincibility in court and recent researches have indicated that his inflexible dogmatism led to miscarriages of justice.

On 17 July 2008, files containing notes on deaths investigated by Spilsbury were auctioned at Sotheby's and were acquired by the Wellcome Library

The Wellcome Library is founded on the collection formed by Sir Henry Wellcome (1853–1936), whose personal wealth allowed him to create one of the most ambitious collections of the 20th century. Henry Wellcome's interest was the history of med ...

in London. The files' index card

An index card (or record card in British English and system cards in Australian English) consists of card stock (heavy paper) cut to a standard size, used for recording and storing small amounts of discrete data. A collection of such cards e ...

s documented deaths in the County of London

The County of London was a county of England from 1889 to 1965, corresponding to the area known today as Inner London. It was created as part of the general introduction of elected county government in England, by way of the Local Government A ...

and the Home Counties

The home counties are the counties of England that surround London. The counties are not precisely defined but Buckinghamshire and Surrey are usually included in definitions and Berkshire, Essex, Hertfordshire and Kent are also often inc ...

from 1905 to 1932. The hand-written cards, discovered in a lost cabinet, were the notes that Spilsbury apparently accumulated for a textbook on forensic medicine which he was planning, but there is no evidence that he ever started the book.

Legacy

It was Spilsbury who, together with personnel fromScotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

, was responsible for devising the so-called murder bag, the kit containing plastic gloves, tweezers, evidence bags, etc., that detectives attending the scene of a suspicious death are now equipped with.

Spilsbury is commemorated by an English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses.

The charity states that i ...

blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term i ...

attached to his former home at Marlborough Hill in north London. Also at his birthplace, 35 Bath Street, Leamington Spa, which was his father's chemist and still a chemist shop today.

Media

Spilsbury is mentioned in theSevered Heads

Severed Heads were an Australian electronic music group founded in 1979 as Mr and Mrs No Smoking Sign. The original members were Richard Fielding and Andrew Wright, who were soon joined by Tom Ellard. Fielding and Wright had both left the band b ...

song 'Dead Eyes Opened' by the narrator, Edgar Lustgarten as 'a great pathologist with unique experience'. The song uses Edgar Wallace

Richard Horatio Edgar Wallace (1 April 1875 – 10 February 1932) was a British writer.

Born into poverty as an illegitimate London child, Wallace left school at the age of 12. He joined the army at age 21 and was a war correspondent during th ...

's transcription of Patrick Herbert Mahon's trial for the murder of his lover Emily Beilby Kaye.

In the 1956 film ''The Man Who Never Was

''The Man Who Never Was'' is a 1956 British espionage thriller film produced by André Hakim and directed by Ronald Neame. It stars Clifton Webb and Gloria Grahame and features Robert Flemyng, Josephine Griffin and Stephen Boyd. It is based ...

'', about Operation Mincemeat

Operation Mincemeat was a successful British deception operation of the Second World War to disguise the 1943 Allied invasion of Sicily. Two members of British intelligence obtained the body of Glyndwr Michael, a tramp who died from eating ...

, André Morell

Cecil André Mesritz (20 August 1909 – 28 November 1978), known professionally as André Morell, was an English actor. He appeared frequently in theatre, film and on television from the 1930s to the 1970s. His best known screen roles were as ...

played Spilsbury.

The BBC science documentary series ''Horizon

The horizon is the apparent line that separates the surface of a celestial body from its sky when viewed from the perspective of an observer on or near the surface of the relevant body. This line divides all viewing directions based on whether i ...

'' cast a critical eye on Spilsbury's work in the 1970 episode ''The Expert Witness''.

In the 1976 Thames Television

Thames Television, commonly simplified to just Thames, was a Broadcast license, franchise holder for a region of the British ITV (TV network), ITV television network serving Greater London, London and surrounding areas from 30 July 1968 until th ...

series ''Killers'', Spilsbury was played in three episodes by Derek Waring

Derek Waring (born Derek Barton-Chapple; 26 April 1927 – 20 February 2007) was an English actor who is best remembered for playing Detective Inspector Goss in ''Z-Cars'' from 1969 to 1973. He was married to fellow actor, Dame Dorothy T ...

.

Spilsbury was played by Andrew Johns in the 1980-81 Granada TV series ''Lady Killers''.

In P.D. James’ 1986 mystery novel, “A Taste for Death,” a character who is a forensic pathologist is said to be “getting dangerously infallible with juries. We don’t want another Spilsbury.”

Nicholas Selby

Nicholas Selby (born James Ivor Selby, 13 September 1925 – 14 September 2010) was a British film, television and theatre actor. He appeared in more than one hundred television dramas on the BBC and ITV during the course of his career, includi ...

played Spilsbury in the 1994 mini-series ''Dandelion Dead

''Dandelion Dead'' is a British TV mini-series produced by LWT for ITV that aired in two parts on 6 and 13 February 1994. It tells the true story of Herbert Rowse Armstrong, a solicitor in the provincial town of Hay-on-Wye, Wales, who was con ...

'', a dramatisation of the Armstrong Armstrong may refer to:

Places

* Armstrong Creek (disambiguation), various places

Antarctica

* Armstrong Reef, Biscoe Islands

Argentina

* Armstrong, Santa Fe

Australia

* Armstrong, Victoria

Canada

* Armstrong, British Columbia

* Armstrong ...

poisoning case.

On 12 June 2008, BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC that replaced the BBC Home Service in 1967. It broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes, including news, drama, comedy, science and history from the BBC' ...

's ''Afternoon Drama

''Drama'' (formerly ''Afternoon Theatre'', ''Afternoon Drama,'' ''Afternoon Play'') is a BBC Radio 4 radio drama, broadcast every weekday at 2.15pm. Generally each play is 45 minutes in duration and approximately 190 new plays are broadcast each ...

'' play, ''The Incomparable Witness'' by Nichola McAuliffe

Nichola McAuliffe (born 1955) is an English television and stage actress and writer, best known for her role as Sheila Sabatini in the ITV hospital sitcom '' Surgical Spirit'' (1989–1995). She has also starred in several stage musicals and won ...

, was a drama about the involvement of "Sir Bernard Spilsbury, the father of modern forensics" in the Crippen case as seen from the point of view of Spilsbury's wife Edith. The radio play was directed by Sasha Yevtushenko with Timothy Watson as Spilsbury, Joanna David

Joanna David (born Joanna Elizabeth Hacking; 17 January 1947) is an English actress, best known for her television work.

Life

David was born in Lancaster, England, to Davida Elizabeth (''née'' Nesbitt) and John Almond Hacking.

In 1971, she ...

as Edith, Honeysuckle Weeks

Honeysuckle Susan Weeks (born 1 August 1979) is a British actress best known for her role as Samantha Stewart (later Wainwright) in the ITV (TV channel), ITV wartime drama series ''Foyle's War''.

Early life

Weeks was born in Cardiff, Wales, to ...

as the young Edith and John Rowe (who played Spilsbury in an episode of the short-lived 1984 BBC Scotland

BBC Scotland (Scottish Gaelic: ''BBC Alba'') is a division of the BBC and the main public broadcaster in Scotland.

It is one of the four BBC national regions, together with the BBC English Regions, BBC Cymru Wales and BBC Northern Ireland. I ...

TV series ''Murder Not Proven?'') as the Lord Chief Justice.

In the 2019 musical Operation Mincemeat

Operation Mincemeat was a successful British deception operation of the Second World War to disguise the 1943 Allied invasion of Sicily. Two members of British intelligence obtained the body of Glyndwr Michael, a tramp who died from eating ...

Jak Malone originated the role of Spilsbury.

In 2019 the BBC1 series ''Murder, Mystery and My Family

''Murder, Mystery and My Family'' is a BBC One series featuring Sasha Wass KC and Jeremy Dein KC., which examines historic criminal convictions sentenced to the death penalty in order to determine if any of them resulted in a miscarriage of ...

'' concluded that the conviction of the then 15-year-old Jack Hewitt (1907-1972) for the murder at Gallowstree Common

Gallowstree Common is a hamlet in South Oxfordshire, England, about north of Reading, Berkshire. The village had a public house, the Reformation, which was controlled by the Brakspear brewery. The brewery sold the pub garden for housing and t ...

of Sarah Blake (1877-1922) was unsafe, partly due to Spilsbury's misleading evidence to the jury about the putative murder weapon.

Posthumous reputation

During Spilsbury's lifetime, and as early as 1925 after the murder conviction ofNorman Thorne

Norman Thorne (c. 1902 – 22 April 1925) was an England, English Sunday school teacher and chicken farmer who was convicted and hanged for what became known as the chicken run murder.

, concern began to be expressed by informed opinion about his domination of the courtroom and about the quality of his methodology. The influential ''Law Journal

A law review or law journal is a scholarly journal or publication that focuses on legal issues. A law review is a type of legal periodical. Law reviews are a source of research, imbedded with analyzed and referenced legal topics; they also pr ...

'' expressed 'profound disquiet' at the verdict, noting 'the more than Papal infallibility with which Sir Bernard Spilsbury is rapidly being invested by juries.'.

In more recent years, there has been some reassessment of Spilsbury's reputation, which has raised questions over his degree of objectivity. Sydney Smith

Sydney Smith (3 June 1771 – 22 February 1845) was an English wit, writer, and Anglican cleric.

Early life and education

Born in Woodford, Essex, England, Smith was the son of merchant Robert Smith (1739–1827) and Maria Olier (1750–1801), ...

judged Spilsbury 'very brilliant and very famous, but fallible...and very, very obstinate.' Keith Simpson wrote of Spilsbury 'whose positive evidence had doubtless led to conviction at trials that might have ended with sufficient doubt for acquittal.' Burney and Pemberton (2010) noted how the "virtuosity" of Spilsbury's performances in the mortuary

A morgue or mortuary (in a hospital or elsewhere) is a place used for the storage of human corpses awaiting identification (ID), removal for autopsy, respectful burial, cremation or other methods of disposal. In modern times, corpses have cus ...

and the courtroom "threatened to undermine the foundations of forensic pathology as a modern and objective specialism."

He has in particular been criticised for his insistence on working alone, his refusal to train students, and an unwillingness to engage in academic research or peer review

Peer review is the evaluation of work by one or more people with similar competencies as the producers of the work (peers). It functions as a form of self-regulation by qualified members of a profession within the relevant field. Peer review ...

. This, according to the article, "lent him an aura of infallibility that for many raised concerns that it was his celebrity rather than his science that persuaded juries to credit his evidence over all others."

See also

*Francis Camps

Francis Edward Camps, FRCP, FRCPath (28 June 1905 – 8 July 1972) was an English pathologist notable for his work on the cases of serial killer John Christie and suspected serial killer John Bodkin Adams.

Early life and training

Camps was bo ...

References

Sources

* * Jane Robins, ''The Magnificent Spilsbury and the Case of the Brides in the Bath'', John Murray, London, 2010. * Douglas Browne and E. V. Tullett, ''Bernard Spilsbury: His Life and Cases'', 1951. * Colin Evans, ''The Father of Forensics'', Berkley (Penguin USA), 2006, . * J. H. H. Gaute and Robin Odell, ''The New Murderer's Who's Who'', Harrap Books, London, 1996. * Andrew Rose, ''Lethal Witness'', Sutton Publishing (2007) and Kent State University Press. {{DEFAULTSORT:Spilsbury, Bernard 1877 births 1947 suicides British pathologists People from Leamington Spa British forensic scientists Alumni of Magdalen College, Oxford People with mental disorders Suicides by gas Suicides in London Golders Green Crematorium Knights Bachelor Freemasons of the United Grand Lodge of England Physicians of St Mary's Hospital, London 1947 deaths