Benjamin Robbins Curtis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

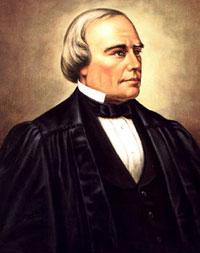

Benjamin Robbins Curtis (November 4, 1809 – September 15, 1874) was an American lawyer and judge. He served as an

Curtis received a

Curtis received a

''Reports of Cases in the Circuit Courts of the United States''

(2 vols., Boston, 1854)

''Judge Curtis's Edition of the Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States''

with notes and a digest (22 vols., Boston: Little Brown & Company, 1855).

''Digest of the Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States from the origin of the court to 1854'' Little Brown & Co., (1864). ''Memoir and Writings''

(2 vols., Boston, 1880), the first volume including a memoir by Curtis's brother, George Ticknor Curtis, and the second "Miscellaneous Writings," edited by the former Justice's son, Benjamin R. Curtis, Jr.

''The Lives and Times of the Chief Justices of the United States Supreme Court''

Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1874 at

Leach, Richard H. ''Benjamin Robins Curtis, Judicial Misfit''. The New England Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Dec., 1952), pp. 507-523 (article consists of 17 pages) Published by: The New England Quarterly, Inc.

* Leach, Richard H. ''Benjamin R. Curtis: Case Study of a Supreme Court Justice'' (Ph.D. diss.,

Fox, John, The First Hundred Years, Biographies of the Robes, Benjamin Robinson Curtis.''

Public Broadcasting Service.

New Publications, ''Judge Benjamin R. Curtis, A Memoir of Benjamin Robbins Curtis, LL.D. With Some of his Professional and Miscellaneous Writings, Edited by his son, Benjamin R. Curtis'', (October 19, 1879).

associate justice of the United States Supreme Court

An associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States is any member of the Supreme Court of the United States other than the chief justice of the United States. The number of associate justices is eight, as set by the Judiciary Act of 1 ...

from 1851 to 1857. Curtis was the first and only Whig justice of the Supreme Court, and was also the first Supreme Court justice to have a formal law degree. He is often remembered as one of the two dissenters in ''Dred Scott v. Sandford

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, enslaved or free; th ...

'' (1857).

Curtis resigned from the Supreme Court in 1857 to return to private legal practice in Boston, Massachusetts. In 1868, Curtis was President Andrew Johnson's defense lawyer during Johnson's impeachment trial.

Early life and education

Curtis was born November 4, 1809, inWatertown, Massachusetts

Watertown is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, and is part of Greater Boston. The population was 35,329 in the 2020 census. Its neighborhoods include Bemis, Coolidge Square, East Watertown, Watertown Square, and the West End.

Waterto ...

, the son of Lois Robbins and Benjamin Curtis, the captain of a merchant vessel. Young Curtis attended common school in Newton and beginning in 1825 Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

, where he won an essay writing contest in his junior year. At Harvard, he became a member of the Porcellian Club

The Porcellian Club is an all-male final club at Harvard University, sometimes called the Porc or the P.C. The year of founding is usually given as 1791, when a group began meeting under the name "the Argonauts",, p. 171: source for 1791 origins ...

. He graduated in 1829, and was a member of Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States, and the most prestigious, due in part to its long history and academic selectivity. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal ...

. He graduated from Harvard Law School in 1832.

First private practice

Admitted to the Massachusetts bar later that year, Curtis began his legal career. In 1834, he moved to Boston and joined the law firm of Charles P. Curtis, where he developed expertise in admiralty law and also became known for his familiarity withpatent law

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A p ...

.

In 1836, Curtis participated in the Massachusetts "freedom suit

Freedom suits were lawsuits in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States filed by slaves against slaveholders to assert claims to freedom, often based on descent from a free maternal ancestor, or time held as a resident in a free state or ter ...

" of '' Commonwealth v. Aves'' as one of the attorneys who unsuccessfully defended a slaveholding father. When New Orleans resident Mary Slater went to Boston to visit her father, Thomas Aves, she brought with her a young slave girl about six years of age, named Med. While Slater fell ill in Boston, she asked her father to take care of Med until she (Slater) recovered. The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society

The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (1833–1840) was an abolitionist, interracial organization in Boston, Massachusetts, in the mid-19th century. "During its brief history ... it orchestrated three national women's conventions, organized a mult ...

and others sought a writ of ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

'' against Aves, contending that Med became free by virtue of her mistress' having brought her voluntarily into Massachusetts. Aves responded to the writ, answering that Med was his daughter's slave, and that he was holding Med as his daughter's agent.

The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, through its Chief Justice, Lemuel Shaw, ruled that Med was free, and made her a ward of the court. The Massachusetts decision was considered revolutionary at the time. Previous decisions elsewhere had ruled that slaves voluntarily brought into a free state, and who resided there many years, became free, ''Commonwealth v. Aves'' was the first decision which held that a slave voluntarily brought into a free state became free the moment they arrived. The decision in this freedom suit proved especially controversial in slaveholding southern states. As with his fellow Massachusettsan and Harvard graduate John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before his presidency, he was a leader of t ...

, Curtis's willingness to serve as defense attorney for the Aves family was not necessarily reflective of his personal or legal views (''cf.'' his dissent in the 1857 Dred Scott decision

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, enslaved or free; th ...

, 21 years later and 6 years into his term as an Associate Supreme Court Justice.

Curtis became a member of the Harvard Corporation

The President and Fellows of Harvard College (also called the Harvard Corporation or just the Corporation) is the smaller and more powerful of Harvard University's two governing boards, and is now the oldest corporation in America. Together with ...

, one of the two governing boards of Harvard University, in February 1846. In 1849, he was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives

The Massachusetts House of Representatives is the lower house of the Massachusetts General Court, the state legislature of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. It is composed of 160 members elected from 14 counties each divided into single-member ...

. Appointed chairman of a committee to reform state judicial procedures, they presented the Massachusetts Practice Act of 1851. "It was considered a model of judicial reform and was approved by the legislature without amendment."

At the time, Curtis was viewed as a rival to Rufus Choate

Rufus Choate (October 1, 1799July 13, 1859) was an American lawyer, orator, and Senator who represented Massachusetts as a member of the Whig Party. He is regarded as one of the greatest American lawyers of the 19th century, arguing over a th ...

, and was thought to be the preeminent leader of the New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

bar. Curtis came from a politically connected family, and had studied under Joseph Story

Joseph Story (September 18, 1779 – September 10, 1845) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, serving from 1812 to 1845. He is most remembered for his opinions in ''Martin v. Hunter's Lessee'' and '' United States ...

and John Hooker Ashmun at Harvard Law School. His legal arguments were thought to be well-reasoned and persuasive. Curtis was a Whig and in tune with their politics, and Whigs were in power. As a potential young appointee, he was thought to be the seed of a long and productive judicial career. He was appointed by the president, approved by the Senate, elevated to the Supreme Court bench, but was gone in six years.

Supreme Court service

Curtis received a

Curtis received a recess appointment

In the United States, a recess appointment is an appointment by the president of a federal official when the U.S. Senate is in recess. Under the U.S. Constitution's Appointments Clause, the President is empowered to nominate, and with the a ...

to the United States Supreme Court on September 22, 1851 by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

, filling the vacancy caused by the death of Levi Woodbury

Levi Woodbury (December 22, 1789September 4, 1851) was an American attorney, jurist, and Democratic politician from New Hampshire. During a four-decade career in public office, Woodbury served as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the U ...

. Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison ...

persuaded Fillmore to nominate Curtis to the Supreme Court, and was his primary sponsor. Formally nominated on December 11, 1851, Curtis was confirmed by the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

on December 20, 1851, and received his commission the same day. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

in 1854.

He was the first Supreme Court Justice to have earned a law degree from a law school. His predecessors had either " read law" (a form of apprenticeship

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

in a practicing firm) or attended a law school without receiving a degree.

His opinion in '' Cooley v. Board of Wardens'' 53 U.S. 299 (1852) held that the Commerce Power as provided in the Commerce Clause

The Commerce Clause describes an enumerated power listed in the United States Constitution ( Article I, Section 8, Clause 3). The clause states that the United States Congress shall have power "to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and amon ...

, U.S. Const., Art. I, § 8, cl. 3, extends to laws related to pilotage

Piloting or pilotage is the process of navigating on water or in the air using fixed points of reference on the sea or on land, usually with reference to a nautical chart or aeronautical chart to obtain a fix of the position of the vessel or air ...

. States laws related to commerce powers can be valid so long as Congress is silent on the matter. That resolved a historic controversy over federal interstate commerce

The Commerce Clause describes an enumerated power listed in the United States Constitution ( Article I, Section 8, Clause 3). The clause states that the United States Congress shall have power "to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and amo ...

powers. To this day, it is an important precedent in commerce cases. The issue was whether states can regulate aspects of commerce or whether that power is exclusive to Congress. Curtis concluded that the federal government has exclusive power to regulate commerce only when national uniformity is required. Otherwise, states may regulate commerce.

Curtis was one of the two dissenters in the ''Dred Scott

Dred Scott (c. 1799 – September 17, 1858) was an enslaved African American man who, along with his wife, Harriet, unsuccessfully sued for freedom for themselves and their two daughters in the '' Dred Scott v. Sandford'' case of 1857, popula ...

'' case, in which he disagreed with essentially every holding of the court. He argued against the majority's denial of the bid for emancipation

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure economic and social rights, political rights or equality, often for a specifically disenfranch ...

by the slave Dred Scott. Curtis stated that, because there were black citizens in both Southern and Northern states at the time of the drafting of the federal Constitution, black people thus were clearly among the "people of the United States" contemplated thereunder. Curtis also opined that because the majority had found that Scott lacked standing, the Court could not go further and rule on the merits of Scott's case.

Curtis resigned from the court on September 30, 1857, in part because he was exasperated with the fraught atmosphere in the court engendered by the case. As one source puts it, "a bitter disagreement and coercion by Roger Taney

Roger Brooke Taney (; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. Although an opponent of slavery, believing it to be an evil practice, Taney belie ...

prompted Benjamin Curtis's departure from the Court in 1857." However, others view the cause of his resignation as having been both temperamental and financial. He did not like " riding the circuit," as Supreme Court Justices were then required to do. He was temperamentally estranged from the court and was not inclined to work with others. He was not a team player, at least on that team. The acrimony over the Dred Scott decision had blossomed into mutual distrust. He did not want to live on $6,500 per year, much less than his earnings in private practice.

Return to private practice

Upon his resignation, Curtis returned to his Boston law practice, becoming a "leading lawyer" in the nation. During the ensuing decade and a half, he argued several cases before the Supreme Court. Although Curtis initially was supportive ofAbraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

as President, by 1863 he was criticizing Lincoln’s “utter incompetence”, and publicly argued that the Emancipation Proclamation was unconstitutional. This put Curtis out of the running when Lincoln had to choose a successor to Chief Justice Roger Taney

Roger Brooke Taney (; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. Although an opponent of slavery, believing it to be an evil practice, Taney belie ...

who died in October 1864. In the presidential campaign of that year, Curtis supported Democrat George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

against Lincoln.

In 1868, Curtis acted as defense counsel for President Andrew Johnson during Johnson's impeachment trial. He read the answer to the articles of impeachment, which was "largely his work". His opening statement

An opening statement is generally the first occasion that the trier of fact (jury or judge) has to hear from a lawyer in a trial, aside possibly from questioning during voir dire. The opening statement is generally constructed to serve as a "roa ...

lasted two days, and was commended for legal prescience and clarity. He successfully persuaded the Senate that an impeachment was a judicial act, not a political act, so that it required a full hearing of evidence. This precedent "influenced every subsequent impeachment".

After the impeachment trial, Curtis declined President Andrew Johnson's offer of the position of U.S. Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

. A highly recommended candidate for the Chief Justice position upon the death of Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808May 7, 1873) was an American politician and jurist who served as the sixth chief justice of the United States. He also served as the 23rd governor of Ohio, represented Ohio in the United States Senate, a ...

in 1873, Curtis was passed over by President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

. He was the unsuccessful Democratic candidate for U.S. senator from Massachusetts in 1874. From his judicial retirement in 1857 to his death in 1874, his aggregate professional income was about $650,000.

Personal life

Curtis had 12 children and was three times married.Death and legacy

Curtis died inNewport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

, on September 15, 1874. He is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery, 580 Mount Auburn Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts. On October 23, 1874, Attorney General George Henry Williams

George Henry Williams (March 26, 1823April 4, 1910) was an American judge and politician. He served as chief justice of the Oregon Supreme Court, was the 32nd Attorney General of the United States, and was elected Oregon's U.S. senator, and serv ...

presented in the Supreme Court the resolutions submitted by the bar on Curtis's death and shared observations on Judge Curtis's defense of President Andrew Johnson in the articles of impeachment against him.

Curtis's daughter, Annie Wroe Scollay Curtis, married (on December 9, 1880) future Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

President and New York Mayor Seth Low

Seth Low (January 18, 1850 – September 17, 1916) was an American educator and political figure who served as the mayor of Brooklyn from 1881 to 1885, the president of Columbia University from 1890 to 1901, a diplomatic representative of t ...

."Seth Low" by Gerald Kurland, New York, Twayne Publishers, 1971 They had no children.

Published works

''Reports of Cases in the Circuit Courts of the United States''

(2 vols., Boston, 1854)

''Judge Curtis's Edition of the Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States''

with notes and a digest (22 vols., Boston: Little Brown & Company, 1855).

''Digest of the Decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States from the origin of the court to 1854'' Little Brown & Co., (1864).

(2 vols., Boston, 1880), the first volume including a memoir by Curtis's brother, George Ticknor Curtis, and the second "Miscellaneous Writings," edited by the former Justice's son, Benjamin R. Curtis, Jr.

See also

* Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States *Dual federalism

Dual federalism, also known as layer-cake federalism or divided sovereignty, is a political arrangement in which power is divided between the federal and state governments in clearly defined terms, with state governments exercising those powers ...

*List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest-ranking judicial body in the United States. Its membership, as set by the Judiciary Act of 1869, consists of the chief justice of the United States and eight associate justices, any six of ...

*List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

A total of 116 people have served on the Supreme Court of the United States, the highest judicial body in the United States, since it was established in 1789. Supreme Court justices have life tenure, and so they serve until they die, resign, reti ...

*Origins of the American Civil War

Historians who debate the origins of the American Civil War focus on the reasons that seven Southern states (followed by four other states after the onset of the war) declared their secession from the United States (the Union) and united to ...

* United States Supreme Court cases during the Taney Court

References

*Further reading

* * * Flanders, Henry''The Lives and Times of the Chief Justices of the United States Supreme Court''

Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1874 at

Google Books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google Inc. that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical ...

.

*

*

* Huebner, Timothy S.; Renstrom, Peter; coeditor. (2003) ''The Taney Court, Justice Rulings and Legacy''. City: ABC-Clio Inc. .

Leach, Richard H. ''Benjamin Robins Curtis, Judicial Misfit''. The New England Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Dec., 1952), pp. 507-523 (article consists of 17 pages) Published by: The New England Quarterly, Inc.

* Leach, Richard H. ''Benjamin R. Curtis: Case Study of a Supreme Court Justice'' (Ph.D. diss.,

Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

, 1951).

*

*

*Simon, James F. (2006) ''Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney: Slavery, Secession, and the President's War Powers'' (Paperback) New York: Simon & Schuster

Simon & Schuster () is an American publishing company and a subsidiary of Paramount Global. It was founded in New York City on January 2, 1924 by Richard L. Simon and M. Lincoln Schuster. As of 2016, Simon & Schuster was the third largest pu ...

, 336 pages. .

*

External links

*Fox, John, The First Hundred Years, Biographies of the Robes, Benjamin Robinson Curtis.''

Public Broadcasting Service.

New Publications, ''Judge Benjamin R. Curtis, A Memoir of Benjamin Robbins Curtis, LL.D. With Some of his Professional and Miscellaneous Writings, Edited by his son, Benjamin R. Curtis'', (October 19, 1879).

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Curtis, Benjamin Robbins

1809 births

1874 deaths

19th-century American Episcopalians

19th-century American judges

19th-century American politicians

American Unitarians

Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery

Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

Harvard Law School alumni

Members of the defense counsel for the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson

Freedom suits in the United States

Massachusetts lawyers

Members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives

Massachusetts Whigs

People from Watertown, Massachusetts

United States federal judges appointed by Millard Fillmore

Recess appointments

Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

United States federal judges admitted to the practice of law by reading law

19th-century American memoirists