Belgian revolution on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Belgian Revolution (, ) was the conflict which led to the

Catholic partisans watched with excitement the unfolding of the

Catholic partisans watched with excitement the unfolding of the  William I sent his two sons, Crown- Prince William and Prince Frederik to quell the riots. William was asked by the Burghers of Brussels to come to the town alone, with no troops, for a meeting; this he did, despite the risks. The affable and moderate Crown Prince William, who represented the monarchy in Brussels, was convinced by the Estates-General on 1 September that the administrative separation of north and south was the only viable solution to the crisis. His father rejected the terms of accommodation that Prince William proposed. King William I attempted to restore the established order by force, but the 8,000 Dutch troops under Prince Frederik were unable to retake Brussels in bloody street fighting (23–26 September). The army was withdrawn to the fortresses of

William I sent his two sons, Crown- Prince William and Prince Frederik to quell the riots. William was asked by the Burghers of Brussels to come to the town alone, with no troops, for a meeting; this he did, despite the risks. The affable and moderate Crown Prince William, who represented the monarchy in Brussels, was convinced by the Estates-General on 1 September that the administrative separation of north and south was the only viable solution to the crisis. His father rejected the terms of accommodation that Prince William proposed. King William I attempted to restore the established order by force, but the 8,000 Dutch troops under Prince Frederik were unable to retake Brussels in bloody street fighting (23–26 September). The army was withdrawn to the fortresses of

In November 1830, the National Congress of Belgium was established to create a constitution for the new state. The Congress decided that Belgium would be a popular,

In November 1830, the National Congress of Belgium was established to create a constitution for the new state. The Congress decided that Belgium would be a popular,

in JSTOR

* * Schroeder, Paul W. ''The Transformation of European Politics 1763-1848'' (1994) pp 671–91 *Stallaerts, Robert. ''The A to Z of Belgium'' (2010) *

{{Authority control B Separatism in Belgium Separatism in the Netherlands Wars involving Belgium Wars involving the Netherlands 1830 in Belgium 1831 in Belgium 1830 in the Netherlands Conflicts in 1830 Conflicts in 1831 19th-century revolutions 19th century in the Southern Netherlands Belgium–Netherlands relations Revolutions of 1830

secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics l ...

of the southern provinces (mainly the former Southern Netherlands

The Southern Netherlands, also called the Catholic Netherlands, were the parts of the Low Countries belonging to the Holy Roman Empire which were at first largely controlled by Habsburg Spain (Spanish Netherlands, 1556–1714) and later by the A ...

) from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands

The United Kingdom of the Netherlands ( nl, Verenigd Koninkrijk der Nederlanden; french: Royaume uni des Pays-Bas) is the unofficial name given to the Kingdom of the Netherlands as it existed between 1815 and 1839. The United Netherlands was cr ...

and the establishment of an independent Kingdom of Belgium.

The people of the south were mainly Flemings

The Flemish or Flemings ( nl, Vlamingen ) are a Germanic ethnic group native to Flanders, Belgium, who speak Dutch. Flemish people make up the majority of Belgians, at about 60%.

"''Flemish''" was historically a geographical term, as all in ...

and Walloons

Walloons (; french: Wallons ; wa, Walons) are a Gallo-Romance ethnic group living native to Wallonia and the immediate adjacent regions of France. Walloons primarily speak '' langues d'oïl'' such as Belgian French, Picard and Walloon. Wallo ...

. Both peoples were traditionally Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

as contrasted with Protestant-dominated ( Dutch Reformed) people of the north. Many outspoken liberals regarded King William I's rule as despotic. There were high levels of unemployment and industrial unrest among the working classes.

On 25 August 1830, riots erupted in Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

and shops were looted. Theatregoers who had just watched the nationalistic opera '' La muette de Portici'' joined the mob. Uprisings followed elsewhere in the country. Factories were occupied and machinery destroyed. Order was restored briefly after William committed troops to the Southern Provinces but rioting continued and leadership was taken up by radicals, who started talking of secession.

Dutch units saw the mass desertion of recruits from the southern provinces and pulled out. The States-General in Brussels voted in favour of secession and declared independence. In the aftermath, a National Congress ''National Congress'' is a term used in the names of various political parties and legislatures .

Political parties

*Ethiopia: Oromo National Congress

*Guyana: People's National Congress (Guyana)

*India: Indian National Congress

*Iraq: Iraqi Nati ...

was assembled. King William refrained from future military action and appealed to the Great Powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power in ...

. The resulting 1830 London Conference of major European powers recognized Belgian independence. Following the installation of Leopold I as "King of the Belgians" in 1831, King William made a belated attempt to reconquer Belgium and restore his position through a military campaign. This " Ten Days' Campaign" failed because of French military intervention. The Dutch accepted the decision of the London conference and Belgian independence in 1839 by signing the Treaty of London.

United Kingdom of the Netherlands

After the defeat of Napoleon at theBattle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armies of the Sevent ...

in 1815, the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon ...

created a kingdom for the House of Orange-Nassau

The House of Orange-Nassau ( Dutch: ''Huis van Oranje-Nassau'', ) is the current reigning house of the Netherlands. A branch of the European House of Nassau, the house has played a central role in the politics and government of the Netherland ...

, thus combining the United Provinces of the Netherlands with the former Austrian Netherlands to create a strong buffer state

A buffer state is a country geographically lying between two rival or potentially hostile great powers. Its existence can sometimes be thought to prevent conflict between them. A buffer state is sometimes a mutually agreed upon area lying between t ...

north of France; with the addition of those provinces the Netherlands became a rising power. Symptomatic of the tenor of diplomatic bargaining at Vienna was the early proposal to reward Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

for its fight against Napoleon with the former Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

territory. When the United Kingdom insisted on retaining the former Dutch Ceylon

Dutch Ceylon ( Sinhala: Tamil: ) was a governorate established in present-day Sri Lanka by the Dutch East India Company. Although the Dutch managed to capture most of the coastal areas in Sri Lanka, they were never able to control the Kandyan ...

and the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with ...

, which it had seized while the Netherlands was ruled by Napoleon, the new Kingdom of the Netherlands was compensated with these southern provinces (modern Belgium).

Causes of the Revolution

The revolution was due to a combination of factors, the main one being the difference of religion (Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in today's Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

, Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

in today's Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

) and the general lack of autonomy given to the south.

Other important factors are

* The under-representation of today's Belgians in the General Assembly (62% of the population for 50% of the seats)

* Most of the institutions were based in the North and public burdens were unevenly distributed. Only one minister out of four was Belgian. There were four times as many Dutch people in the administration as Belgians.Jacques Logie, op. cit., p. 12 There was a general domination of the Dutch over the economic, political, and social institutions of the Kingdom;

* The public debt of the north (higher than the one of the south) had to be supported by the south as well. The original debts were initially of 1.25 billion guilders for the United Provinces and only 100 million for the South.

* The action of William I in the field of education (construction of schools, control of the competence of teachers and the creation of new establishments, creation of three State universities) placed it under the total control of the State, which displeased Catholic opinion.

* The contingent imposed on Belgium by the recruitment of militiamen was proportionally high, while the proportion of Belgians among the officers was low, the high staff being mainly composed of former officers of the French army or of the British army. Only one officer out of six would be from the South. Most Belgian soldiers were therefore commanded by officers who were not originally from the Southern Netherlands. Moreover, the Dutch language had become the sole language of the army of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1823/24, which was an additional grievance on the part of the francophone elites and the Walloon people who spoke Romance dialects.

* The unsatisfactory application of freedom of the press and freedom of assembly were considered by Belgian intellectuals as a means of control of the South by the North.

* Belgian merchants and industrialists complained about the free trade policy pursued from 1827 onwards. The separation of France had caused the industry of the South to lose a large part of its turnover. On the other hand, the colony of the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

was experiencing a long period of revolt and British products were competing with Belgian production. With the end of the continental blockade, the continent was invaded by cheap British products, appreciated by the North, still mainly agricultural, but which excluded the productions of the South.

* A linguistic reform in 1823 was intended to make Dutch the official language in the Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

provinces. This reform was met with strong opposition from the upper classes who at the time were mostly French-speaking, whether they came from Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

or Wallonia

Wallonia (; french: Wallonie ), or ; nl, Wallonië ; wa, Waloneye or officially the Walloon Region (french: link=no, Région wallonne),; nl, link=no, Waals gewest; wa, link=no, Redjon walone is one of the three regions of Belgium—al ...

, but also from the Flemish speakers themselves, who at the time did not speak standard Dutch but their own dialects. On 4 June 1830, this reform was abolished.

* The conservatives in the northern Netherlands were pushing for only followers of the former (Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

) State Church to be appointed to the government, while the Belgian conservatives wanted to re-establish Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

as the state religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular, is not necessarily a t ...

in Belgium. The coexistence of two state religions throughout the kingdom was unacceptable to both sides. Until 1821 the government used the opposition of the Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

to the Basic Law to maintain the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

character of the state apparatus through the appointment of civil servants. William I himself was a supporter of the German Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

tradition, according to which the sovereign is the head of the church. He wanted to counter the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

's authority over the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

. He wanted to be able to influence the appointment of bishops

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

.

"Night at the opera"

Catholic partisans watched with excitement the unfolding of the

Catholic partisans watched with excitement the unfolding of the July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after French Revolution, the first in 1789. It led to ...

in France, details of which were swiftly reported in the newspapers. On 25 August 1830, at the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie

The Royal Theatre of La Monnaie (french: Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie, italic=no, ; nl, Koninklijke Muntschouwburg, italic=no; both translating as the "Royal Theatre of the Mint") is an opera house in central Brussels, Belgium. The National O ...

in Brussels, an uprising followed a special performance, in honor of William I's birthday, of Daniel Auber's '' La Muette de Portici'' ''(The Mute Girl of Portici)'', a sentimental and patriotic opera set against Masaniello's uprising against the Spanish masters of Naples in the 17th century. After the duet, "Amour sacré de la patrie", (Sacred love of Fatherland) with Adolphe Nourrit in the tenor role, many audience members left the theater and joined the riots which had already begun. The crowd poured into the streets shouting patriotic slogans. The rioters swiftly took possession of government buildings. The following days saw an explosion of the desperate and exasperated proletariat of Brussels, who rallied around the newly created flag of the Brussels independence movement which was fastened to a standard with shoelaces during a street fight and used to lead a counter-charge against the forces of Prince William.

William I sent his two sons, Crown- Prince William and Prince Frederik to quell the riots. William was asked by the Burghers of Brussels to come to the town alone, with no troops, for a meeting; this he did, despite the risks. The affable and moderate Crown Prince William, who represented the monarchy in Brussels, was convinced by the Estates-General on 1 September that the administrative separation of north and south was the only viable solution to the crisis. His father rejected the terms of accommodation that Prince William proposed. King William I attempted to restore the established order by force, but the 8,000 Dutch troops under Prince Frederik were unable to retake Brussels in bloody street fighting (23–26 September). The army was withdrawn to the fortresses of

William I sent his two sons, Crown- Prince William and Prince Frederik to quell the riots. William was asked by the Burghers of Brussels to come to the town alone, with no troops, for a meeting; this he did, despite the risks. The affable and moderate Crown Prince William, who represented the monarchy in Brussels, was convinced by the Estates-General on 1 September that the administrative separation of north and south was the only viable solution to the crisis. His father rejected the terms of accommodation that Prince William proposed. King William I attempted to restore the established order by force, but the 8,000 Dutch troops under Prince Frederik were unable to retake Brussels in bloody street fighting (23–26 September). The army was withdrawn to the fortresses of Maastricht

Maastricht ( , , ; li, Mestreech ; french: Maestricht ; es, Mastrique ) is a city and a municipality in the southeastern Netherlands. It is the capital and largest city of the province of Limburg. Maastricht is located on both sides of the ...

, Venlo, and Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

, and when the Northern commander of Antwerp bombarded the town, claiming a breach of a ceasefire, the whole of the Southern provinces was incensed. Any opportunity to quell the breach was lost on 26 September when a National Congress was summoned to draw up a Constitution and the Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or ...

was established under Charles Latour Rogier

Charles Latour Rogier (; 17 August 1800 – 27 May 1885) was a Belgian liberal statesman and a leader in the Belgian Revolution of 1830. He served as the prime minister of Belgium on two occasions: from 1847 to 1852, and again from 1857 to ...

. A Declaration of Independence followed on 4 October 1830.

The European powers and an independent Belgium

On 20 December 1830 theLondon Conference of 1830

The London Conference of 1830 brought together representatives of the five major European powers Austria, Britain, France, Prussia and Russia. At the conference, which began on 20 December, they recognized the success of the Belgian secession fr ...

brought together five major European powers: Austria, the United Kingdom, France, Prussia and Russia. At first, the European powers were divided over the Belgian cry for independence. The Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

were still fresh in the memories of the major European powers, so once the French, under the recently installed July Monarchy

The July Monarchy (french: Monarchie de Juillet), officially the Kingdom of France (french: Royaume de France), was a liberal constitutional monarchy in France under , starting on 26 July 1830, with the July Revolution of 1830, and ending 23 ...

, supported Belgian independence, the other European powers unsurprisingly supported the continued union of the Provinces of the Netherlands. Russia, Prussia, Austria, and the United Kingdom all supported the Netherlands, since they feared that the French would eventually annex an independent Belgium (particularly the British: see Flahaut partition plan for Belgium

The Flahaut partition plan for Belgium was a proposal developed in 1830 at the London Conference of 1830 by the French diplomat Charles de Flahaut, to partition Belgium. The proposal was immediately rejected by the French Foreign Ministry upon ...

). However, in the end, none of the European powers sent troops to aid the Dutch government, partly because of rebellions within some of their own borders (the Russians were occupied with the November Uprising in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

and Prussia was saddled with war debt). Britain would come to see the benefits of isolating France geographically with the new creation of a new Belgian buffer state

A buffer state is a country geographically lying between two rival or potentially hostile great powers. Its existence can sometimes be thought to prevent conflict between them. A buffer state is sometimes a mutually agreed upon area lying between t ...

between France, the Netherlands and Prussia. It was for that reason that Britain would eventually sponsor the creation of Belgium.

Accession of King Leopold

constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

. On 7 February 1831, the Belgian Constitution

The Constitution of Belgium ( nl, Belgische Grondwet, french: Constitution belge, german: Verfassung Belgiens) dates back to 1831. Since then Belgium has been a parliamentary monarchy that applies the principles of ministerial responsibility ...

was proclaimed. However, no actual monarch yet sat on the throne.

The Congress refused to consider any candidate from the Dutch ruling house of Orange-Nassau

The House of Orange-Nassau ( Dutch: ''Huis van Oranje-Nassau'', ) is the current reigning house of the Netherlands. A branch of the European House of Nassau, the house has played a central role in the politics and government of the Netherland ...

. Eventually the Congress drew up a shortlist of three candidates, all of whom were French. This itself led to political opposition, and Leopold of Saxe-Coburg

* nl, Leopold Joris Christiaan Frederik

* en, Leopold George Christian Frederick

, image = NICAISE Leopold ANV.jpg

, caption = Portrait by Nicaise de Keyser, 1856

, reign = 21 July 1831 –

, predecessor = Erasme Loui ...

, who had been considered at an early stage but dropped due to French opposition, was proposed again. On 22 April 1831, Leopold was approached by a Belgian delegation at Marlborough House to officially offer him the throne. At first reluctant to accept, he eventually took up the offer, and after an enthusiastic popular welcome on his way to Brussels, Leopold I of Belgium took his oath as king on 21 July 1831.

21 July is generally used to mark the end of the revolution and the start of the Kingdom of Belgium. It is celebrated each year as Belgian National Day

Belgian National Day ( nl, Nationale feestdag van België; french: Fête nationale belge; german: Belgischer Nationalfeiertag) is the national holiday of Belgium commemorated annually on 21 July. It is one of the country's ten public holidays ...

.

Post-independence

Ten Days' Campaign

King William was not satisfied with the settlement drawn up in London and did not accept Belgium's claim of independence: it divided his kingdom and drastically affected his Treasury. From 2–12 August 1831 the Dutch army, headed by the Dutch princes, invaded Belgium, in the so-called " Ten Days' Campaign", and defeated a makeshift Belgian force nearHasselt

Hasselt (, , ; la, Hasseletum, Hasselatum) is a Belgian city and municipality, and capital and largest city of the province of Limburg in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is known for its former branding as "the city of taste", as well as i ...

and Leuven

Leuven (, ) or Louvain (, , ; german: link=no, Löwen ) is the capital and largest city of the province of Flemish Brabant in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is located about east of Brussels. The municipality itself comprises the historic c ...

. Only the appearance of a French army under Marshal Gérard

Gérard (French: ) is a French masculine given name and surname of Germanic origin, variations of which exist in many Germanic and Romance languages. Like many other early Germanic names, it is dithematic, consisting of two meaningful constitue ...

caused the Dutch to stop their advance. While the victorious initial campaign gave the Dutch an advantageous position in subsequent negotiations, the Dutch were compelled to agree to an indefinite armistice, although they continued to hold the Antwerp Citadel

Antwerp Citadel ( es, Castillo de Amberes, nl, Kasteel van Antwerpen) was a pentagonal bastion fort built to defend and dominate the city of Antwerp in the early stages of the Dutch Revolt. It has been described as "doubtlesse the most matchlesse ...

and occasionally bombarded the city until French forces forced them out in December 1832. William I would refuse to recognize a Belgian state until April 1839, when he had to yield under pressure by the Treaty of London and reluctantly recognized a border which, with the exception of Limburg and Luxembourg, was basically the border of 1790.

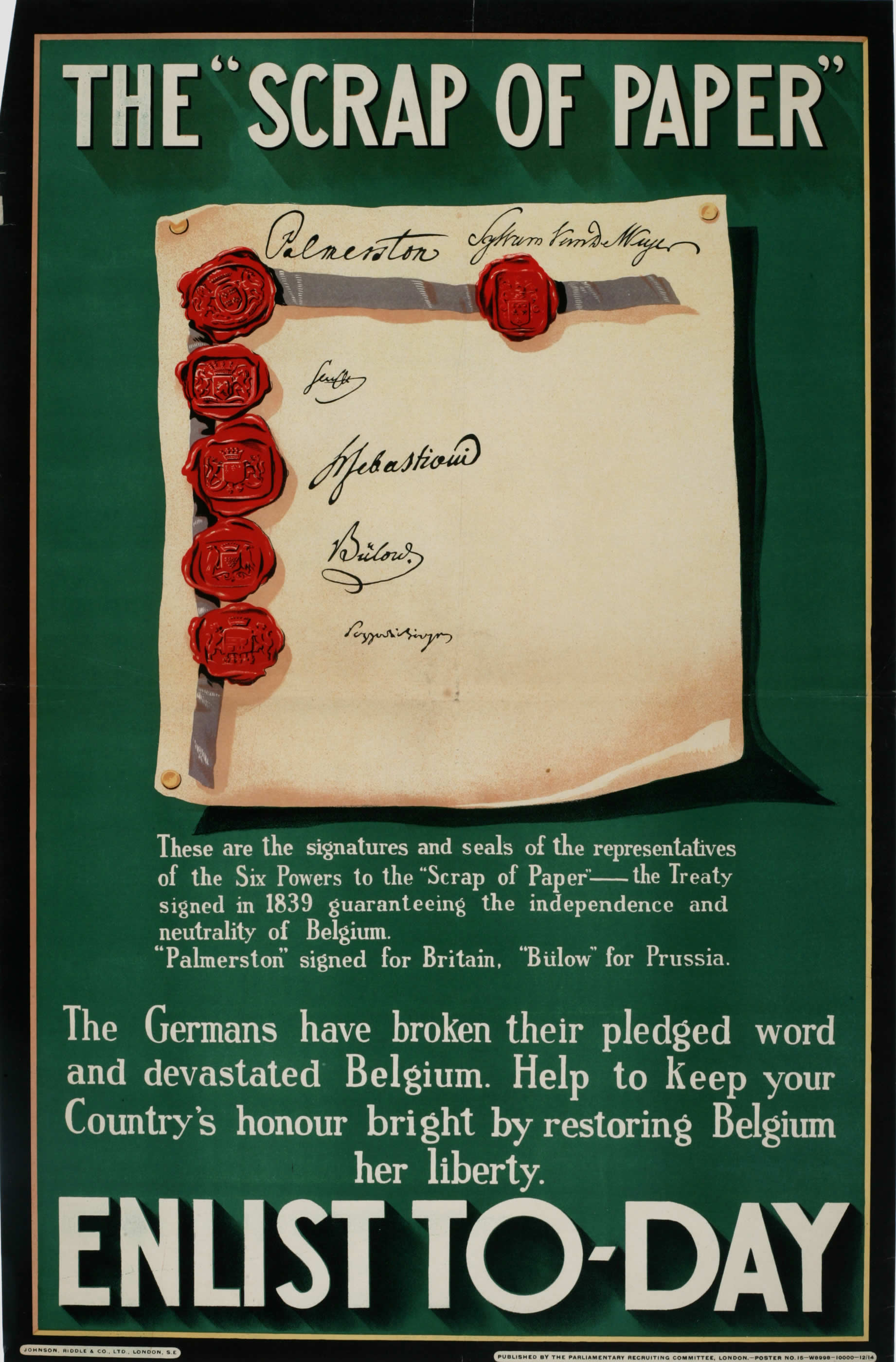

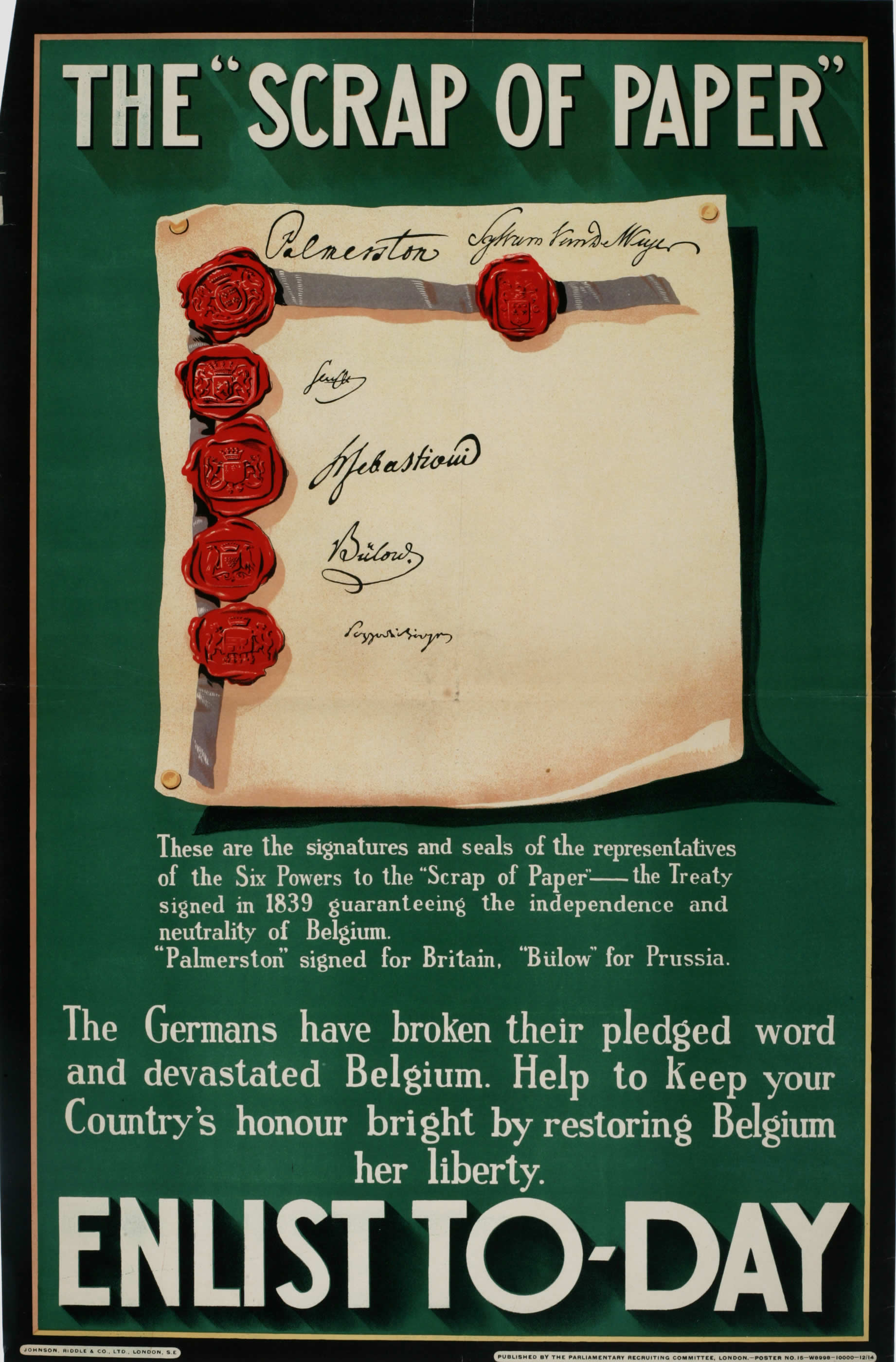

1839 Treaty of London

On 19 April 1839 the Treaty of London signed by the European powers (including the Netherlands) recognized Belgium as an independent and neutral country comprisingWest Flanders

West Flanders ( nl, West-Vlaanderen ; vls, West Vloandern; french: (Province de) Flandre-Occidentale ; german: Westflandern ) is the westernmost province of the Flemish Region, in Belgium. It is the only coastal Belgian province, facing the No ...

, East Flanders

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Province of Belgium

, image_flag = Flag of Oost-Vlaanderen.svg

, flag_size =

, image_shield = Wapen van O ...

, Brabant Brabant is a traditional geographical region (or regions) in the Low Countries of Europe. It may refer to:

Place names in Europe

* London-Brabant Massif, a geological structure stretching from England to northern Germany

Belgium

* Province of Bra ...

, Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

, Hainaut, Namur

Namur (; ; nl, Namen ; wa, Nameur) is a city and municipality in Wallonia, Belgium. It is both the capital of the province of Namur and of Wallonia, hosting the Parliament of Wallonia, the Government of Wallonia and its administration.

Na ...

, and Liège

Liège ( , , ; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is a major city and municipality of Wallonia and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far fro ...

, as well as half of Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

and Limburg. The Dutch army, however, held onto Maastricht

Maastricht ( , , ; li, Mestreech ; french: Maestricht ; es, Mastrique ) is a city and a municipality in the southeastern Netherlands. It is the capital and largest city of the province of Limburg. Maastricht is located on both sides of the ...

, and as a result, the Netherlands kept the eastern half of Limburg and its large coalfields.

Germany broke the treaty in 1914 when it invaded Belgium and dismissed British protests over a "scrap of paper".

Orangism

As early as 1830 a movement started for the reunification of Belgium and the Netherlands, called Orangism (after the Dutch royal color of orange), which was active in Flanders and Brussels. But industrial cities, like Liège, also had a strong Orangist faction. The movement met with strong disapproval from the authorities. Between 1831 and 1834, 32 incidents of violence against Orangists were mentioned in the press and in 1834 Minister of Justice Lebeau banned expressions of Orangism in the public sphere, enforced with heavy penalties.Anniversary remembrances

Cinquantenaire (50th anniversary)

Thegolden jubilee

A golden jubilee marks a 50th anniversary. It variously is applied to people, events, and nations.

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, golden jubilee refers the 50th anniversary year of the separation from Pakistan and is called in Bengali ''"সু� ...

of independence set up the Cinquantenaire

The Parc du Cinquantenaire (French for "Park of the Fiftieth Anniversary", pronounced ) or Jubelpark ( Dutch for "Jubilee Park", pronounced ) is a large public, urban park of in the easternmost part of the European Quarter in Brussels, Belg ...

park complex in Brussels.

175th anniversary commemoration

In 2005, the Belgian revolution of 1830 was depicted in one of the highest value Belgian coins ever minted, the 100 euro "175 Years of Belgium" coin. The obverse depicts a detail from Wappers' painting ''Scene of the September Days in 1830''.See also

*History of Belgium

The history of Belgium extends before the founding of the modern state of that name in 1830, and is intertwined with those of its neighbors: the Netherlands, Germany, France and Luxembourg. For most of its history, what is now Belgium was either ...

*Jan van Speyk

Jan Carel Josephus van Speyk (31 January 1802 – 5 February 1831) was a Dutch naval lieutenant commander with the United Netherlands Navy who became a hero in the Netherlands for his opposition to the Belgian Revolution.

Life

Early ...

*Unionism in Belgium

In the politics of Belgium, Unionism or Union of Opposites (''union des oppositions'') is a Belgian political movement that existed from the 1820s to 1846. (In the present day, the term 'unionists' is sometimes used in a Belgian context to descri ...

References

Bibliography

* Fishman, J. S. "The London Conference of 1830," ''Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis'' (1971) 84#3 pp 418–428. * Fishman, J. S. ''Diplomacy and Revolution: The London Conference of 1830 and the Belgian Revolt'' (Amsterdam, 1988) *Kossmann, E. H. ''The Low Countries 1780–1940'' (1978), pp 151–60 *Kossmann-Putto, J. A. and E. H. Kossmann. ''The Low Countries: History of the Northern and Southern Netherlands'' (1987) * Omond. G. W. T. "The Question of the Netherlands in 1829-1830," ''Transactions of the Royal Historical Society'' (1919) vol 2 pp. 150–17in JSTOR

* * Schroeder, Paul W. ''The Transformation of European Politics 1763-1848'' (1994) pp 671–91 *Stallaerts, Robert. ''The A to Z of Belgium'' (2010) *

External links

{{Authority control B Separatism in Belgium Separatism in the Netherlands Wars involving Belgium Wars involving the Netherlands 1830 in Belgium 1831 in Belgium 1830 in the Netherlands Conflicts in 1830 Conflicts in 1831 19th-century revolutions 19th century in the Southern Netherlands Belgium–Netherlands relations Revolutions of 1830