Belgian Resistance on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Belgian Resistance (french: Résistance belge, nl, Belgisch verzet) collectively refers to the

The Belgian Resistance (french: Résistance belge, nl, Belgisch verzet) collectively refers to the

Among the first members of the Belgian resistance were former soldiers, and in particular officers, who, on their return from prisoner of war camps, wished to continue the fight against the Germans out of patriotism. Nevertheless, resistance was slow to develop in the first few months of the occupation because it seemed that German victory was imminent. The German failure to invade Great Britain, coupled with aggravating German policies within occupied Belgium, especially the persecution of Belgian Jews and conscription of Belgian civilians into forced labour programmes increasingly turned patriotic Belgian civilians from liberal or Catholic backgrounds against the German regime and towards the resistance. With the

Among the first members of the Belgian resistance were former soldiers, and in particular officers, who, on their return from prisoner of war camps, wished to continue the fight against the Germans out of patriotism. Nevertheless, resistance was slow to develop in the first few months of the occupation because it seemed that German victory was imminent. The German failure to invade Great Britain, coupled with aggravating German policies within occupied Belgium, especially the persecution of Belgian Jews and conscription of Belgian civilians into forced labour programmes increasingly turned patriotic Belgian civilians from liberal or Catholic backgrounds against the German regime and towards the resistance. With the

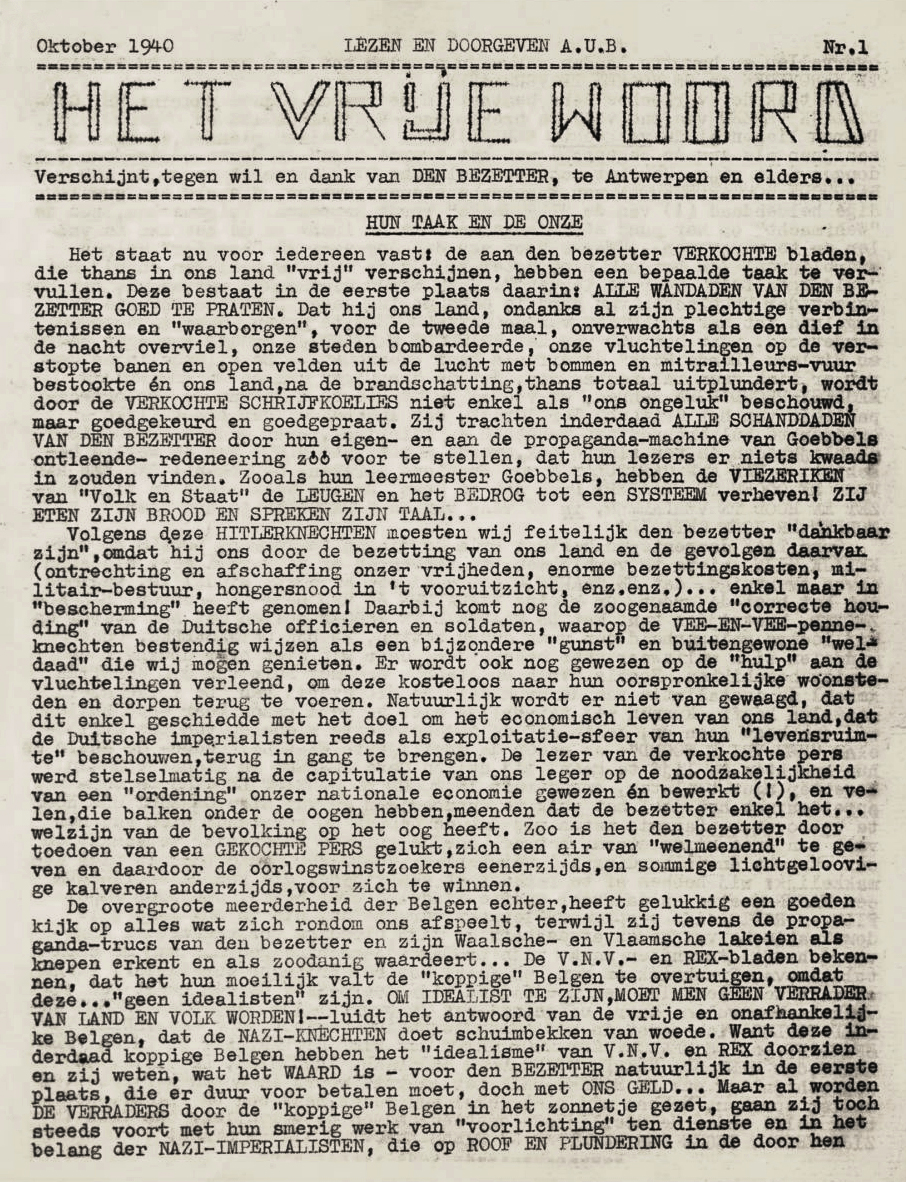

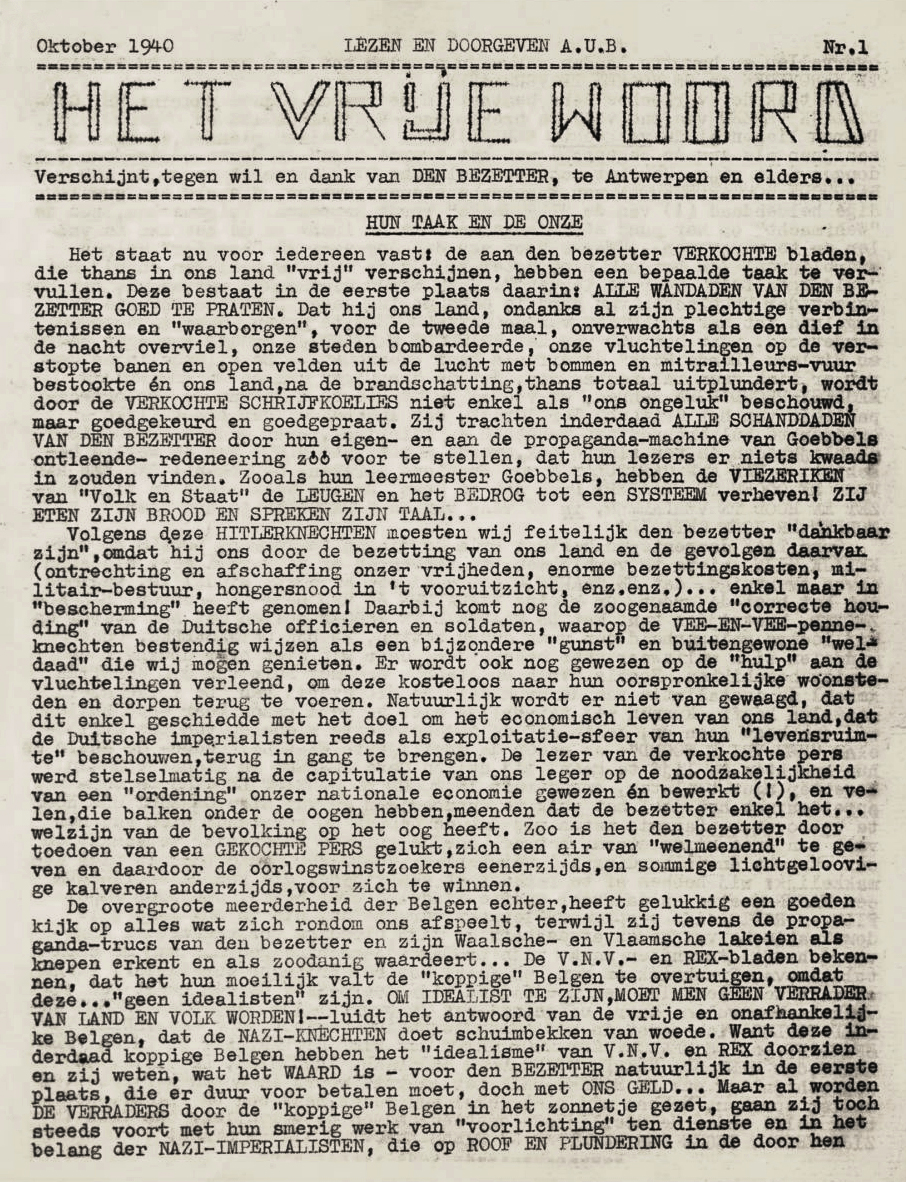

During the occupation an underground press flourished in Belgium from soon after the Belgian defeat, with eight newspapers appearing by October 1940 alone. Much of the resistance's press focused around producing newspapers in both

During the occupation an underground press flourished in Belgium from soon after the Belgian defeat, with eight newspapers appearing by October 1940 alone. Much of the resistance's press focused around producing newspapers in both

The German ''Geheime Staatspolizei'' ("Secret state police"), known as the

The German ''Geheime Staatspolizei'' ("Secret state police"), known as the

Nevertheless, the apparent isolation of the government in exile from the day-to-day situation in Belgium meant that it was viewed with suspicion by many resistance groups, particularly those whose politics differed from that of the established government. The government, for its part, was afraid that resistance groups would turn into ungovernable political militias after liberation, challenging the government's position and threatening political stability. Nevertheless, the resistance was frequently reliant on finance and drops of equipment and supplies which both the government-in-exile and the British

Nevertheless, the apparent isolation of the government in exile from the day-to-day situation in Belgium meant that it was viewed with suspicion by many resistance groups, particularly those whose politics differed from that of the established government. The government, for its part, was afraid that resistance groups would turn into ungovernable political militias after liberation, challenging the government's position and threatening political stability. Nevertheless, the resistance was frequently reliant on finance and drops of equipment and supplies which both the government-in-exile and the British

After the Normandy Landings in June 1944, the Belgian resistance increased in size dramatically. In April 1944, the began to adopt an official rank hierarchy and uniform (of white overalls and armband) to be worn on missions in order to give their organization the status of an "official army".

Though they usually lacked the equipment and training to fight the ''

After the Normandy Landings in June 1944, the Belgian resistance increased in size dramatically. In April 1944, the began to adopt an official rank hierarchy and uniform (of white overalls and armband) to be worn on missions in order to give their organization the status of an "official army".

Though they usually lacked the equipment and training to fight the ''

The Belgian Resistance (french: Résistance belge, nl, Belgisch verzet) collectively refers to the

The Belgian Resistance (french: Résistance belge, nl, Belgisch verzet) collectively refers to the resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized effort by some portion of the civil population of a country to withstand the legally established government or an occupying power and to disrupt civil order and stability. It may seek to achieve its objectives ...

s opposed to the German occupation of Belgium during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. Within Belgium, resistance was fragmented between many separate organizations, divided by region and political stances. The resistance included both men and women from both Walloon and Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

parts of the country. Aside from sabotage of military infrastructure in the country and assassinations of collaborators, these groups also published large numbers of underground newspapers

The terms underground press or clandestine press refer to periodicals and publications that are produced without official approval, illegally or against the wishes of a dominant (governmental, religious, or institutional) group.

In specific rec ...

, gathered intelligence and maintained various escape networks that helped Allied airmen trapped behind enemy lines escape from German-occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

.

During the war, it is estimated that approximately five percent of the national population were involved in some form of resistance activity, while some estimates put the number of resistance members killed at over 19,000; roughly 25 percent of its "active" members.Henri Bernard's estimate puts resistance casualties at 19,048 of around 70,000 active members. Quoted in

Background

German invasion and occupation

German forces invaded Belgium, which had been following a policy of neutrality, on 10 May 1940. After 18 days of fighting, the Belgian Army surrendered on 28 May and the country was placed under German military occupation. During the fighting, between 600,000 and 650,000 Belgian men (nearly 20 percent of the country's male population) served in the military. Many were madeprisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

and detained in camps Camps may refer to:

People

*Ramón Camps (1927–1994), Argentine general

*Gabriel Camps (1927–2002), French historian

*Luís Espinal Camps (1932–1980), Spanish missionary to Bolivia

* Victoria Camps (b. 1941), Spanish philosopher and professo ...

in Germany, although some were released before the end of the war. Leopold III, king and commander-in-chief of the army, also surrendered to the Germans on 28 May along with his army and was also held prisoner by the Germans. On 18 June the Belgian Government

The Federal Government of Belgium ( nl, Federale regering, french: Gouvernement fédéral, german: Föderalregierung) exercises executive power in the Kingdom of Belgium. It consists of ministers and secretary of state ("junior", or deputy-mini ...

fled and arrived first in Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectu ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

after the French government had fled to the region three days earlier. On that same day the Belgian government sent a telegram to the imprisoned Belgian king, stating their resignation to the king. Marcel-Henri Jaspar, the Belgian Minister of Health, went to London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

on 21 June without the permission of the government. He later gave a speech on BBC Radio on 23 June stating he would continue to fight against the Germans. Three days later the Belgian government stripped his ministerial title in reaction to the speech.

Growth of resistance

German invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

in June 1941, members of the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engel ...

, which had previously been ambivalent towards both Allied and Axis sides, also joined the resistance ''en masse'', forming their own separate groups calling for a "national uprising" against Nazi rule. During the First World War, Belgium had been occupied by Germany for four years and had developed an effective network of resistance, which provided key inspiration for the formation of similar groups in 1940.

Most of the resistance was focused in the French-speaking areas of Belgium (Wallonia

Wallonia (; french: Wallonie ), or ; nl, Wallonië ; wa, Waloneye or officially the Walloon Region (french: link=no, Région wallonne),; nl, link=no, Waals gewest; wa, link=no, Redjon walone is one of the three regions of Belgium—al ...

and the city of Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

), although Flemish involvement in the resistance was also significant. Around 70 percent of underground newspapers were in French, while 60 percent of political prisoners were Walloon.

Resistance during the German occupation

Passive resistance

The most widespread form of resistance in occupied Belgium wasnon-violent

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

. Listening to broadcasts from London, which was officially prohibited by the German occupiers, was a common form of passive resistance, but civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called "civil". H ...

in particular was employed. This was often carried out by Belgian government institutions that were forced to carry out the administration of the territory on behalf of the German military government. In June 1941, the City Council of Brussels refused to distribute Star of David badges on behalf of the German government to Belgian Jews.

Striking was the most common form of passive resistance and often took place on symbolic dates, such as the 10 May (anniversary of the German invasion), 21 July ( National Day) and 11 November (anniversary of the German surrender in World War I). The largest was the so-called "Strike of the 100,000

The Strike of the 100,000 (french: Grève des 100 000) was an 8-day strike in German-occupied Belgium which took place from 10–18 May 1941. It was led by Julien Lahaut, head of the Belgian Communist Party (''Parti Communiste de Belgique'' or ...

", which broke out on 10 May 1941 in the Cockerill steel works in Seraing. News of the strike spread rapidly and soon at least 70,000 workers came out on strike across the province of Liège. The Germans increased workers' salaries by eight percent and the strike finished rapidly. Future large-scale strikes were repressed by the Germans, although further important strikes occurred in November 1942 and February 1943.

King Leopold III

Leopold III (3 November 1901 – 25 September 1983) was King of the Belgians from 23 February 1934 until his abdication on 16 July 1951. At the outbreak of World War II, Leopold tried to maintain Belgian neutrality, but after the German invasi ...

, imprisoned in Laeken Palace, became a focal point for passive resistance, despite having been condemned by the government-in-exile for his decision to surrender.

Active resistance

Active resistance within Belgium developed from early 1941 and took several directions. Armed resistance, in the forms of sabotage or assassinations, took place, but was only part of the "active" resistance's scope of activity. Some groups had very specific forms of resistance and became extremely specialized. The group, for example, had many members in the national postal service and used them to intercept letters of denunciation, warning the denounced person to flee. In this way, they succeeded in intercepting over 20,000 letters. Membership of the active resistance, which had been quite low in the early years of the resistance, swelled exponentially during 1944 as it was joined by so-called "resisters of the eleventh hour" (''résistants de la onzième heure'') who could see that Allied victory was close, particularly in the months after D-Day. It is estimated that approximately five percent of the national population were involved in some form of "active" resistance during the war.Structure and organisation

The Belgian resistance effort was extremely fragmented between various groups and never became a unified organization during the German occupation. The danger of infiltration posed by German informants meant that some cells were extremely small and localized, and although nationwide groups did exist, they were split along political and ideological lines. They ranged from the very left-wing, like the Communist or Socialist , to the far-right, like the monarchist and the which had been created by members of the pre-war Fascist movement. However, there were also other groups like which, though without an obvious political affiliation, recruited only from very specific demographics.Forms of active resistance

Sabotage and assassination

Belgium's strategic location meant that it constituted an important supply hub for the whole German army in Northern Europe and particularly northern France. Sabotage was therefore an important duty of the resistance. Following theNormandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

in June 1944 on orders from the Allies, the Belgian resistance began to step up its sabotage against German supply lines across the country. Between June and September alone, 95 railroad bridges, 285 locomotives, 1,365 wagons and 17 tunnels were all blown up by the Belgian resistance. Telegraph lines were also cut and road bridges and canals used to transport material sabotaged. In one notable action, 600 German soldiers were killed when a railway bridge between La Gleize and Stoumont

Stoumont () is a municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Liège, Belgium.

On January 1, 2006, Stoumont had a total population of 3,006. The total area is 108.45 km2 which gives a population density of 28 inhabitants per km2 ...

in the Ardennes

The Ardennes (french: Ardenne ; nl, Ardennen ; german: Ardennen; wa, Årdene ; lb, Ardennen ), also known as the Ardennes Forest or Forest of Ardennes, is a region of extensive forests, rough terrain, rolling hills and ridges primarily in Be ...

was blown up by 40 members of the resistance, including the writer Herman Bodson. Indeed, more German troops were reportedly killed in Belgium in 1941 than in all of Occupied France

The Military Administration in France (german: Militärverwaltung in Frankreich; french: Occupation de la France par l'Allemagne) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied z ...

. Through its sabotage activities alone, one resistance group, , required the Germans to expend between 20 and 25 million man-hours of labour on repairing damage done, including ten million in the night of 15–16 January 1944 alone.

Assassination of key figures in the hierarchy of German and collaborationist hierarchy became increasingly common through 1944. In July 1944, the assassinated the brother of Léon Degrelle

Léon Joseph Marie Ignace Degrelle (; 15 June 1906 – 31 March 1994) was a Belgian Walloon politician and Nazi collaborator. He rose to prominence in Belgium in the 1930s as the leader of the Rexist Party (Rex). During the German occupatio ...

, head of the collaborationist Rexist Party

The Rexist Party (french: Parti Rexiste), or simply Rex, was a far-right Catholic, nationalist, authoritarian and corporatist political party active in Belgium from 1935 until 1945. The party was founded by a journalist, Léon Degrelle,

and leading Belgian fascist. Informants and suspected double agents were also targeted; the Communist claimed to have killed over 1,000 traitors between June and September 1944.

Clandestine press

During the occupation an underground press flourished in Belgium from soon after the Belgian defeat, with eight newspapers appearing by October 1940 alone. Much of the resistance's press focused around producing newspapers in both

During the occupation an underground press flourished in Belgium from soon after the Belgian defeat, with eight newspapers appearing by October 1940 alone. Much of the resistance's press focused around producing newspapers in both French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

and Dutch language

Dutch ( ) is a West Germanic language spoken by about 25 million people as a first language and 5 million as a second language. It is the third most widely spoken Germanic language, after its close relatives German and English. '' Afrikaans'' ...

as alternatives to collaborationist newspapers like ''Le Soir

''Le Soir'' (, "The Evening") is a French-language Belgian daily newspaper. Founded in 1887 by Emile Rossel, it was intended as a politically independent source of news. It is one of the most popular Francophone newspapers in Belgium, competing ...

''. At its peak, the clandestine newspaper ''La Libre Belgique

''La Libre Belgique'' (; literally ''The Free Belgium''), currently sold under the name ''La Libre'', is a major daily newspaper in Belgium. Together with '' Le Soir'', it is one of the country's major French language newspapers and is popular ...

'' was relaying news within five to six days; faster than the BBC's French-language radio broadcasts, whose coverage lagged several months behind events. Copies of the underground newspapers were distributed anonymously, with some pushed into letterboxes or sent by post. Since they were usually free, the costs of printing were financed by donations from sympathisers. The papers achieved considerable circulation, with reaching a regular circulation of 40,000 by January 1942 and peaking at 70,000, while the Communist paper, , reached 30,000. Dozens of different newspapers existed, often affiliated with different resistance groups or differentiated by political stance, ranging from nationalist, Communist, Liberal or even Feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

. The number of Belgians involved in the underground press is estimated at anywhere up to 40,000 people. In total, 567 separate titles are known from the period of occupation.

The resistance also printed humorous publications and material as propaganda. In November 1943, on the anniversary of the German surrender in the First World War, the group published a spoof edition of the collaborationist newspaper , satirizing the Axis propaganda and biased information permitted by the censors, which was then distributed to newsstands across Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

and deliberately mixed with official copies of the newspaper. 50,000 copies of the spoof publication, dubbed the "''Faux Soir

The "''Faux Soir''" was a spoof issue of the newspaper ''Le Soir'' published in German-occupied Belgium on 9 November 1943. It was produced by the Front de l'Indépendance, a faction in the Belgian Resistance, in a satirical style that ridiculed ...

''" (or "Fake Soir"), were distributed.

Intelligence gathering

Intelligence gathering was one of the first forms of resistance to grow after the Belgian defeat and eventually developed into complex and carefully structured organizations. The Allies were also deeply reliant on the resistance to provide intelligence from the occupied country. This information focused both on German troop movements and other military information, but was also essential for keeping the allies abreast of the attitudes and popular opinion of the Belgian public. Each network was closely organized and carried a codename. The most significant was "Clarence", led by ,which had over 1,000 members feeding it information which was then communicated to London by radio. Other notable networks were "Luc" (renamed "Marc" in 1942) and "Zéro". In total 43 separate intelligence networks existed in Belgium, involving some 14,000 people. The Belgian resistance provided around 80 percent of all information received by the Allies from all resistance groups in Europe.Resistance to the Holocaust

The Belgian resistance was instrumental in saving Jews and Roma from deportation to death camps. In April 1943, members of the resistance group, the successfully attacked the "Twentieth convoy

On 19 April 1943, members of the Belgian Resistance stopped a Holocaust train and freed a number of Jews who were being transported to Auschwitz concentration camp from Mechelen transit camp in Belgium, on the twentieth convoy from the camp. In t ...

" carrying 1,500 Belgian Jews by rail to Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

in Poland. Many Belgians also hid Jews and political dissidents during the occupation: one estimate put the number at some 20,000 people hidden during the war. There was also significant low-level resistance: for instance, in June 1941, the City Council of Brussels refused to distribute Stars of David badges. Certain high-profile members of the Belgian establishment, including Queen Elizabeth

Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022; ), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms

* Queen ...

and Cardinal van Roey, Archbishop of Malines, spoke out against the German treatment of Jews.

In total, 1,612 Belgians have been awarded the distinction of "Righteous Among the Nations

Righteous Among the Nations ( he, חֲסִידֵי אֻמּוֹת הָעוֹלָם, ; "righteous (plural) of the world's nations") is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to sa ...

" by the State of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

for risking their lives to save Jews from persecution during the occupation.

Escape routes for Allied airmen

As the Allies intensified their strategic bombing campaign from 1941, the resistance began to experience a significant increase in the number of Allied airmen from theRAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

and USAAF

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

who had been shot down but evaded capture. The resistance's aim, assisted by the British MI9 organization, was to escort them out of occupied Europe and over the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

to neutral Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

where they might return to England. The best-known of these networks, the Comet Line, organized by Andrée de Jongh

Countess Andrée Eugénie Adrienne de Jongh (30 November 1916 – 13 October 2007), called Dédée and Postman, was a member of the Belgian Resistance during the Second World War. She organised and led the Comet Line (''Le Réseau Comète'' ...

, involved some 2,000 resistance members and was able to escort 700 Allied airmen to Spain. The Line not only fed, housed, and provided civilian clothing for the pilots, but also forged Belgian and French identity cards and rail fares. As the airmen also needed to be hidden in civilian houses for prolonged periods of time, escape lines were particularly vulnerable. During the course of the war, 800 members of the "Comet" line alone were arrested by the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

of whom 140 were executed.

German response

The German ''Geheime Staatspolizei'' ("Secret state police"), known as the

The German ''Geheime Staatspolizei'' ("Secret state police"), known as the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

, was responsible for targeting resistance groups in Belgium. Resistance fighters who were captured could expect to be interrogated, tortured and either summarily executed or sent to a concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

. The Gestapo was effective at using informants within groups to betray whole local resistance networks and in examining resistance publications for clues about its place of production. 2,000 resistance members involved in underground press alone were arrested during the war. In total, 30,000 members of the resistance were captured during the war, of whom 16,000 were executed or died in captivity.

The Germans requisitioned the former Belgian army Fort Breendonk

Fort Breendonk ( nl, Fort van Breendonk, french: Fort de Breendonk) is a former military installation at Breendonk, near Mechelen, in Belgium which served as a Nazi prison camp (''Auffanglager'') during the German occupation of Belgium during Wo ...

, near Mechelen

Mechelen (; french: Malines ; traditional English name: MechlinMechelen has been known in English as ''Mechlin'', from where the adjective ''Mechlinian'' is derived. This name may still be used, especially in a traditional or historical contex ...

, which was used for torture and interrogation of political prisoners and members of the resistance. Around 3,500 inmates passed through the camp at Breendonk where they were kept in extremely degrading conditions. Around 300 people were killed in the camp itself, with at least 98 of them dying from deprivation or torture.

Towards the end of the war, the militias of collaborationist political parties also began to participate actively in reprisals for attacks or assassinations by the resistance. These included both reprisal assassinations of leading figures suspected of resistance involvement or sympathy (including Alexandre Galopin

Alexandre Galopin (26 September 1879 – 28 February 1944) was a Belgian businessman notable for his role in German-occupied Belgium during World War II. Galopin was director of the Société Générale de Belgique, a major Belgian company, and ...

, head of the ''Société Générale

Société Générale S.A. (), colloquially known in English as SocGen (), is a French-based multinational financial services company founded in 1864, registered in downtown Paris and headquartered nearby in La Défense.

Société Générale ...

'', who was assassinated in February 1944) or retaliatory massacres against civilians. Foremost among these was the Courcelles Massacre, a reprisal by Rexist paramilitaries for the assassination of a Burgomaster

Burgomaster (alternatively spelled burgermeister, literally "master of the town, master of the borough, master of the fortress, master of the citizens") is the English form of various terms in or derived from Germanic languages for the chie ...

, in which 20 civilians were killed. A similar massacre also took place at Meensel-Kiezegem, where 67 were killed.

Relations with the Allies and Belgian government in exile

TheBelgian government in exile

The Belgian Government in London (french: Gouvernement belge à Londres, nl, Belgische regering in Londen), also known as the Pierlot IV Government, was the government in exile of Belgium between October 1940 and September 1944 during World W ...

made its first call for the creation of organized resistance in the country from its first place of exile in Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectu ...

, before its flight to London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

after the French surrender:

Nevertheless, the apparent isolation of the government in exile from the day-to-day situation in Belgium meant that it was viewed with suspicion by many resistance groups, particularly those whose politics differed from that of the established government. The government, for its part, was afraid that resistance groups would turn into ungovernable political militias after liberation, challenging the government's position and threatening political stability. Nevertheless, the resistance was frequently reliant on finance and drops of equipment and supplies which both the government-in-exile and the British

Nevertheless, the apparent isolation of the government in exile from the day-to-day situation in Belgium meant that it was viewed with suspicion by many resistance groups, particularly those whose politics differed from that of the established government. The government, for its part, was afraid that resistance groups would turn into ungovernable political militias after liberation, challenging the government's position and threatening political stability. Nevertheless, the resistance was frequently reliant on finance and drops of equipment and supplies which both the government-in-exile and the British Special Operations Executive

The Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a secret British World War II organisation. It was officially formed on 22 July 1940 under Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton, from the amalgamation of three existing secret organisations. Its p ...

(SOE) were able to provide. During the course of the war, the government-in-exile delivered between 124-245 million francs

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th centu ...

, dropped by parachute or transferred via bank accounts in neutral Portugal, to the group alone, with smaller sums also distributed to other organisations.

In the early years of the war, contact with the government in exile was difficult to establish. The dispatched a member to try to establish contact in May 1941, it took a full year to reach London. Radio contact was briefly established in late 1941, however, the contact was extremely intermittent between 1942 and 1943, with a permanent radio connection to the (codenamed "Stanley") only established in 1944.

In May 1944, the government-in-exile attempted to rebuild its relationship with the resistance by establishing a "Coordination Committee" of representatives of the major groups, including the '' Légion Belge'', '' Mouvement National Belge'', ''Groupe G

The General Sabotage Group of Belgium (french: Groupe Général de Sabotage de Belgique), more commonly known as Groupe G, was a Belgian resistance group during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbr ...

'' and the ''Front de l'Indépendance

The Independent Front (french: Front de l'Indépendance or FI; nl, Onafhankelijkheidsfront, OF) was a left-wing faction of the Belgian Resistance in German-occupied Belgium in World War II. It was founded in March 1941 by Dr Albert Marteaux ...

''. However, the committee was rendered redundant by the liberation in September.

The Resistance during the Liberation

After the Normandy Landings in June 1944, the Belgian resistance increased in size dramatically. In April 1944, the began to adopt an official rank hierarchy and uniform (of white overalls and armband) to be worn on missions in order to give their organization the status of an "official army".

Though they usually lacked the equipment and training to fight the ''

After the Normandy Landings in June 1944, the Belgian resistance increased in size dramatically. In April 1944, the began to adopt an official rank hierarchy and uniform (of white overalls and armband) to be worn on missions in order to give their organization the status of an "official army".

Though they usually lacked the equipment and training to fight the ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

'' openly, the resistance played a key role in assisting the Allies during the liberation of Belgium in September 1944, providing information on German troop movements, disrupting German evacuation plans and participating in fighting. The resistance was particularly important during the liberation of the city of Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

, where the local resistance from the and , in an unprecedented display of inter-group cooperation, assisted British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

forces in capturing the highly strategic port of Antwerp

The Port of Antwerp-Bruges is the port of the City of Antwerp. It is located in Flanders (Belgium), mainly in the province of Antwerp but also partially in the province of East Flanders. It is a seaport in the heart of Europe accessible to ...

intact, before it could be sabotaged by the German garrison. Across Belgium, 20,000 German soldiers (including two generals) were taken prisoner by the resistance, before being handed over to the Allies.

The Free Belgian 5th SAS was dropped by parachute into the Ardennes

The Ardennes (french: Ardenne ; nl, Ardennen ; german: Ardennen; wa, Årdene ; lb, Ardennen ), also known as the Ardennes Forest or Forest of Ardennes, is a region of extensive forests, rough terrain, rolling hills and ridges primarily in Be ...

where it linked up with members of the local resistance during the liberation and the Battle of the Bulge

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive, was the last major German offensive campaign on the Western Front during World War II. The battle lasted from 16 December 1944 to 28 January 1945, towards the end of the war in ...

.

All together, almost 4,000 members of the alone were killed during the liberation.

Disarmament

Soon after the liberation, the reestablished government in Brussels attempted to disarm and demobilize the resistance. In particular, the government feared the organizations would degenerate into armed political militias which could threaten the country's political stability. In October 1944 the government ordered members of the resistance to surrender their weapons to the police and, in November, threatened to search the houses and fine those who had retained them. This provoked significant anger among resistance members, who had hoped that they would be able to continue fighting alongside the Allies in the invasion of Germany. On 25 November, a large demonstration of former resistance members took place in Brussels. As the crowds moved towards theParliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

, British soldiers fired on the crowd, which they suspected to be trying to make left-wing ''coup d'état''. 45 people were wounded.

Nevertheless, large numbers of former members of the resistance enlisted into the regular army, where they formed around 80% of the strength of the Belgian Fusilier Battalions which served on the Western Front until VE Day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945, marking the official end of World War II in Europe in the Easter ...

.

Legacy

The Belgian resistance was praised by contemporaries for its contribution to the Allied war effort; particularly during the later period. In a letter to Lieutenant-General Pire, commander of the , General Eisenhower praised the role that the Belgian resistance had played in disrupting German supply lines after D-Day. The continuing actions of the resistance stopped the Germans ever being able to use the country as a secure base, never fully becoming pacified. The attempt of the resistance to enter mainstream politics with a formal party, the Belgian Democratic Union, failed to attract the level of support that similar parties had managed in France and elsewhere. Associations of former members were founded in the years immediately after the war and campaigned for greater recognition of the role of the resistance. The largest association, the , continues to fund historical research on the role of the resistance and defending the interests of its members. In December 1946, the government ofCamille Huysmans

Jean Joseph Camille Huysmans (born as Camiel Hansen 26 May 1871 – 25 February 1968) was a Belgian politician who served as the prime minister of Belgium from 1946 to 1947.

Biography

He studied German philology at the University of Liège a ...

inaugurated a medal to be awarded to former members of the resistance and bestowed various other benefits on other members, including pensions and a scheme of state-funded apprenticeships. Individuals were accorded military rank equivalent to their status in the movement during the war, entitling them to title and other privileges. Today the role of the resistance during the conflict is commemorated by memorials, plaques and road names across the country, as well as by the National Museum of the Resistance in Anderlecht

Anderlecht (, ) is one of the 19 municipalities of the Brussels-Capital Region, Belgium. Located in the south-western part of the region, it is bordered by the City of Brussels, Forest, Molenbeek-Saint-Jean, and Saint-Gilles, as well as the ...

.

See also

* National Museum of the Resistance inAnderlecht

Anderlecht (, ) is one of the 19 municipalities of the Brussels-Capital Region, Belgium. Located in the south-western part of the region, it is bordered by the City of Brussels, Forest, Molenbeek-Saint-Jean, and Saint-Gilles, as well as the ...

, Belgium

* Belgium in World War II

Despite being neutral at the start of World War II, Belgium and its colonial possessions found themselves at war after the country was invaded by German forces on 10 May 1940. After 18 days of fighting in which Belgian forces were pushed bac ...

* Free Belgian Forces

* Österreichische Freiheitsfront

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * Marie-Pierre d’Udekem d’Acoz, ''Pour le Roi et la Patrie, la Noblesse belge dans la Résistance'', Éditions Racines, 2002Further reading

* * * * * * *External links

* * {{Authority controlBelgian resistance

The Belgian Resistance (french: Résistance belge, nl, Belgisch verzet) collectively refers to the resistance movements opposed to the German occupation of Belgium during World War II. Within Belgium, resistance was fragmented between many se ...