Bekennende Kirche on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Confessing Church (german: link=no, Bekennende Kirche, ) was a movement within

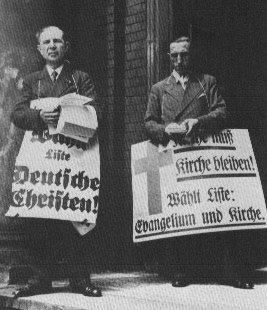

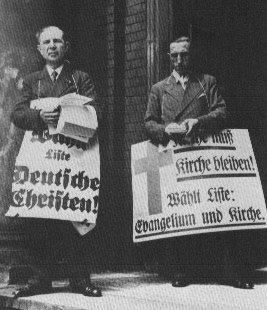

Hitler was infuriated with the rejection of his candidate, and after a series of political maneuvers, Bodelschwingh resigned and Müller was elected as the new ''Reichsbischof'' on 27 September 1933, after the government had already imposed him on 28 June 1933. The formidable propaganda apparatus of the Nazi state was deployed to help the German Christians win presbyter and synodal elections in order to dominate the upcoming synod and finally put Müller into office. Hitler discretionarily decreed unconstitutional premature re-elections of all presbyters and synodals for 23 July; the night before the elections, Hitler made a personal appeal to Protestants by radio.

The German Christians won handily (70–80% of all seats in presbyteries and synods), except in four regional churches and one provincial body of the united old-Prussian church: the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria, Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria right of the river Rhine ("right" meaning "east of"), the Evangelical Lutheran State Church of Hanover, Evangelical Reformed Church in Bavaria and Northwestern Germany, Evangelical Reformed State Church of the Province of Hanover the Lutheran Evangelical State Church in Württemberg, and in the Evangelical Church of Westphalia, old-Prussian ecclesiastical province of Westphalia, where the German Christians gained no majorities. Among adherents of the Confessing Church these church bodies were termed ''intact churches'' (german: :de:Intakte Kirchen, Intakte Kirchen), as opposed to the German Christian-ruled bodies which they designated as "destroyed churches" (german: link=no, zerstörte Kirchen). This electoral victory enabled the German Christians to secure sufficient delegates to prevail at the so-called ''national synod'' that conducted the "revised" September election for ''Reichsbischof''. Further pro-Nazi developments followed the elevation of Müller to the bishopric: in late summer the old-Prussian church (led by Müller since his government appointment on 6 July 1933) adopted the Aryan Paragraph, effectively defrocking clergy of Jewish descent and even clergy married to non-Aryans.

Hitler was infuriated with the rejection of his candidate, and after a series of political maneuvers, Bodelschwingh resigned and Müller was elected as the new ''Reichsbischof'' on 27 September 1933, after the government had already imposed him on 28 June 1933. The formidable propaganda apparatus of the Nazi state was deployed to help the German Christians win presbyter and synodal elections in order to dominate the upcoming synod and finally put Müller into office. Hitler discretionarily decreed unconstitutional premature re-elections of all presbyters and synodals for 23 July; the night before the elections, Hitler made a personal appeal to Protestants by radio.

The German Christians won handily (70–80% of all seats in presbyteries and synods), except in four regional churches and one provincial body of the united old-Prussian church: the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria, Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria right of the river Rhine ("right" meaning "east of"), the Evangelical Lutheran State Church of Hanover, Evangelical Reformed Church in Bavaria and Northwestern Germany, Evangelical Reformed State Church of the Province of Hanover the Lutheran Evangelical State Church in Württemberg, and in the Evangelical Church of Westphalia, old-Prussian ecclesiastical province of Westphalia, where the German Christians gained no majorities. Among adherents of the Confessing Church these church bodies were termed ''intact churches'' (german: :de:Intakte Kirchen, Intakte Kirchen), as opposed to the German Christian-ruled bodies which they designated as "destroyed churches" (german: link=no, zerstörte Kirchen). This electoral victory enabled the German Christians to secure sufficient delegates to prevail at the so-called ''national synod'' that conducted the "revised" September election for ''Reichsbischof''. Further pro-Nazi developments followed the elevation of Müller to the bishopric: in late summer the old-Prussian church (led by Müller since his government appointment on 6 July 1933) adopted the Aryan Paragraph, effectively defrocking clergy of Jewish descent and even clergy married to non-Aryans.

The Aryan Paragraph created a furor among some of the clergy. Under the leadership of Martin Niemöller, the Pfarrernotbund, Pastors' Emergency League (''Pfarrernotbund'') was formed, presumably for the purpose of assisting clergy of Jewish descent, but the League soon evolved into a locus of dissent against Nazi interference in church affairs. Its membership grewBy the end of 1933 the League already had 6,000 members. ''Barnett'' p. 35. while the objections and rhetoric of the German Christians escalated.

The League pledged itself to contest the state's attempts to infringe on the confessional freedom of the churches, that is to say, their ability to determine their own doctrine. It expressly opposed the adoption of the Aryan Paragraph which changed the meaning of baptism. It distinguished between Jews and Christians of Jewish descent and insisted, consistent with the demands of orthodox Christianity, that converted Jews and their descendants were as Christian as anyone else and were full members of the Church in every sense.

At this stage, the objections of Protestant leaders were primarily motivated by the desire for church autonomy and church/state demarcation rather than opposition to the persecution of non-Christian Jews, which was only just beginning. Eventually, the League evolved into the Confessing Church.

On 13 November 1933 a rally of German Christians was held at the Berlin Sportpalast, where — before a packed hall — banners proclaimed the unity of National Socialism and Christianity, interspersed with the omnipresent swastikas. A series of speakers addressed the crowd's pro-Nazi sentiments with ideas such as:

*the removal of all pastors unsympathetic with National Socialism

*the expulsion of members of Jewish descent, who might be arrogated to a separate church

*the implementation of the Aryan Paragraph church-wide

*the Marcionism, removal of the Old Testament from the Bible

*the removal of "non-German" elements from religious services

*the adoption of a more "heroic" and "positive" interpretation of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, who in pro-Aryan race#Nazism, Aryan fashion should be portrayed to be battling mightily against corrupt Jewish influences.

This rather shocking attempt to rally the pro-Nazi elements among the German Christians backfired, as it now appeared to many Protestants that the State was attempting to intervene in the most central theological matters of the church, rather than only in matters of church organization and polity.

While Hitler, a consummate politician, was sensitive to the implications of such developments, Ludwig Müller (theologian), Ludwig Müller was apparently not: he fired and transferred pastors adhering to the Emergency League, and in April 1934 actually deposed the heads of the Württembergian church (Bishop Theophil Wurm) and of the Bavarian church (Bishop Hans Meiser). They and the synodals of their church bodies continuously refused to declare the merger of their church bodies in the German Evangelical Church (DEK). The continuing aggressiveness of the DEK and Müller spurred the schismatic Protestant leaders to further action.

The Aryan Paragraph created a furor among some of the clergy. Under the leadership of Martin Niemöller, the Pfarrernotbund, Pastors' Emergency League (''Pfarrernotbund'') was formed, presumably for the purpose of assisting clergy of Jewish descent, but the League soon evolved into a locus of dissent against Nazi interference in church affairs. Its membership grewBy the end of 1933 the League already had 6,000 members. ''Barnett'' p. 35. while the objections and rhetoric of the German Christians escalated.

The League pledged itself to contest the state's attempts to infringe on the confessional freedom of the churches, that is to say, their ability to determine their own doctrine. It expressly opposed the adoption of the Aryan Paragraph which changed the meaning of baptism. It distinguished between Jews and Christians of Jewish descent and insisted, consistent with the demands of orthodox Christianity, that converted Jews and their descendants were as Christian as anyone else and were full members of the Church in every sense.

At this stage, the objections of Protestant leaders were primarily motivated by the desire for church autonomy and church/state demarcation rather than opposition to the persecution of non-Christian Jews, which was only just beginning. Eventually, the League evolved into the Confessing Church.

On 13 November 1933 a rally of German Christians was held at the Berlin Sportpalast, where — before a packed hall — banners proclaimed the unity of National Socialism and Christianity, interspersed with the omnipresent swastikas. A series of speakers addressed the crowd's pro-Nazi sentiments with ideas such as:

*the removal of all pastors unsympathetic with National Socialism

*the expulsion of members of Jewish descent, who might be arrogated to a separate church

*the implementation of the Aryan Paragraph church-wide

*the Marcionism, removal of the Old Testament from the Bible

*the removal of "non-German" elements from religious services

*the adoption of a more "heroic" and "positive" interpretation of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, who in pro-Aryan race#Nazism, Aryan fashion should be portrayed to be battling mightily against corrupt Jewish influences.

This rather shocking attempt to rally the pro-Nazi elements among the German Christians backfired, as it now appeared to many Protestants that the State was attempting to intervene in the most central theological matters of the church, rather than only in matters of church organization and polity.

While Hitler, a consummate politician, was sensitive to the implications of such developments, Ludwig Müller (theologian), Ludwig Müller was apparently not: he fired and transferred pastors adhering to the Emergency League, and in April 1934 actually deposed the heads of the Württembergian church (Bishop Theophil Wurm) and of the Bavarian church (Bishop Hans Meiser). They and the synodals of their church bodies continuously refused to declare the merger of their church bodies in the German Evangelical Church (DEK). The continuing aggressiveness of the DEK and Müller spurred the schismatic Protestant leaders to further action.

Lutheran educational website

* {{Authority control Christian movements Christian organizations established in 1933 1933 in Germany German resistance to Nazism Lutheran theology History of Lutheranism in Germany Christian denominations founded in Germany Former Christian denominations Protestant denominations established in the 20th century Nazi Germany and Protestantism 1933 establishments in Germany Dietrich Bonhoeffer Karl Barth Kirchenkampf Persecution of Protestants

German Protestantism

The religion of Protestantism, a form of Christianity, was founded within Germany in the 16th-century Reformation. It was formed as a new direction from some Catholic Church, Roman Catholic principles. It was led initially by Martin Luther and ...

during Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

that arose in opposition

Opposition may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''Opposition'' (Altars EP), 2011 EP by Christian metalcore band Altars

* The Opposition (band), a London post-punk band

* '' The Opposition with Jordan Klepper'', a late-night television series on Com ...

to government-sponsored efforts to unify all Protestant churches into a single pro-Nazi German Evangelical Church

The German Evangelical Church (german: Deutsche Evangelische Kirche) was a successor to the German Evangelical Church Confederation from 1933 until 1945.

The German Christians, an antisemitic and racist pressure group and ''Kirchenpartei'', ga ...

. See drop-down essay on "Unification, World Wars, and Nazism"

Demographics

The following statistics (as of January 1933 unless otherwise stated) are an aid in understanding the context of the political and theological developments discussed in this article. *Number of Protestants in Germany: 45 million *Number offree church

A free church is a Christian denomination that is intrinsically separate from government (as opposed to a state church). A free church does not define government policy, and a free church does not accept church theology or policy definitions fr ...

Protestants: 150,000

*Largest regional Protestant church: Evangelical Church of the Old Prussian Union (german: link=no, Evangelische Kirche der altpreußischen Union), with 18 million members, the church strongest in members in the country at the time.

*Number of Protestant pastors: 18,000

**Number of these strongly adhering to the "German Christian" church faction as of 1935: 3000

**Number of these strongly adhering to the "Confessing Church" church faction as of 1935: 3000

***Number of these arrested during 1935: 700

**Number of these not closely affiliated with or adhering to either faction: 12,000

*Total population of Germany: 65 million

*Number of Jews in Germany

The history of the Jews in Germany goes back at least to the year 321, and continued through the Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries CE) and High Middle Ages (''circa'' 1000–1299 CE) when Jewish immigrants founded the Ashkenazi Jewish ...

: 525,000

Historical background

German Protestantism

The Holy Roman Empire and the German Empire

After the Peace of Augsburg in 1555, the principle that the religion of the ruler dictated the religion of the ruled (''cuius regio, eius religio

() is a Latin phrase which literally means "whose realm, their religion" – meaning that the religion of the ruler was to dictate the religion of those ruled. This legal principle marked a major development in the collective (if not individua ...

'') was observed throughout the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

. Section 24 of the Peace of Augsburg (''ius emigrandi'') guaranteed members of denominations other than the ruler's the freedom of emigration with all their possessions. Political stalemates among the government members of different denominations within a number of the republican free imperial cities

In the Holy Roman Empire, the collective term free and imperial cities (german: Freie und Reichsstädte), briefly worded free imperial city (', la, urbs imperialis libera), was used from the fifteenth century to denote a self-ruling city that ...

such as Augsburg

Augsburg (; bar , Augschburg , links=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swabian_German , label=Swabian German, , ) is a city in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, around west of Bavarian capital Munich. It is a university town and regional seat of the ...

, the Free City of Frankfurt, and Regensburg, made their territories de facto bi-denominational, but the two denominations did not usually have equal legal status.

The Peace of Augsburg protected Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

, but not Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

. Thus, in 1613, when John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg

John Sigismund (german: Johann Sigismund; 8 November 1572 – 23 December 1619) was a Prince-elector of the Margraviate of Brandenburg from the House of Hohenzollern. He became the Duke of Prussia through his marriage to Duchess Anna, the eld ...

converted from Lutheranism to Calvinism, he could not exercise the principle of ''cuius regio, eius religio'' ("whose realm, their religion"). This situation paved the way for bi- or multi-denominational monarchies, wherein a ruler adhering to a creed different from most of his subjects would permit conversions to his minority denomination and immigration of his fellow faithful. In 1648, the Peace of Westphalia extended the principle of ''cuius regio, eius religio'' to Calvinism.

However, the principle grew impracticable in the 17th and 18th centuries, which experienced continuous territorial changes arising from annexations and inheritances, and the religious conversion of rulers. For instance, Saxon Augustus II the Strong

Augustus II; german: August der Starke; lt, Augustas II; in Saxony also known as Frederick Augustus I – Friedrich August I (12 May 16701 February 1733), most commonly known as Augustus the Strong, was Elector of Saxony from 1694 as well as K ...

converted from Lutheranism to Catholicism in 1697, but did not exercise his ''cuius regio, eius religio'' privilege. A conqueror or successor to the throne who adhered to a different creed from his new subjects usually would not complicate his takeover by imposing conversions. These enlarged realms spawned diaspora congregations, as immigrants settled in areas where the prevailing creeds differed from their own. This juxtaposition of beliefs in turn brought about more frequent personal changes in denomination, often in the form of marital conversion

Marital conversion is religious conversion upon marriage, either as a conciliatory act, or a mandated requirement according to a particular religious belief. Endogamous religious cultures may have certain opposition to interfaith marriage and e ...

s.

Still, regional mobility was low, especially in the countryside, which generally did not attract newcomers, but experienced rural exodus, so that today's denominational make-up in Germany and Switzerland still represents the former boundaries among territories ruled by Calvinist, Catholic, or Lutheran rulers in the 16th century quite well. In a major departure, the legislature of the North German Confederation

The North German Confederation (german: Norddeutscher Bund) was initially a German military alliance established in August 1866 under the leadership of the Kingdom of Prussia, which was transformed in the subsequent year into a confederated st ...

instituted the right of irreligion

Irreligion or nonreligion is the absence or rejection of religion, or indifference to it. Irreligion takes many forms, ranging from the casual and unaware to full-fledged philosophies such as atheism and agnosticism, secular humanism and ...

ism in 1869, permitting the declaration of secession from all religious bodies.

The Protestant Church in Germany was and is divided into geographic regions and along denominational affiliations (Calvinist, Lutheran, and United churches). In the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, the then-existing monarchies and republics established regional churches ('' Landeskirchen''), comprising the respective congregations within the then-existing state borders. In the case of Protestant ruling dynasties, each regional church affiliated with the regnal houses, and the crown provided financial and institutional support for its church. Church and State were, therefore, to a large extent combined on a regional basis.

Weimar Germany

In the aftermath of World War I with its political and social turmoil, the regional churches lost their secular rulers. With revolutionary fervor in the air, the conservative church leaders had to contend withsocialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the eco ...

(Social Democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

(SPD) and Independent Social Democrats (USPD)), who mostly held to disestablishmentarianism. When Adolph Hoffmann, a strident secularist, was appointed Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

n Minister of Education and Public Worship in November 1918 by the USPD, he attempted to implement a number of plans, which included:

*cutting government subsidies

A subsidy or government incentive is a form of financial aid or support extended to an economic sector (business, or individual) generally with the aim of promoting economic and social policy. Although commonly extended from the government, the ter ...

for the church

*confiscation

Confiscation (from the Latin ''confiscatio'' "to consign to the ''fiscus'', i.e. transfer to the treasury") is a legal form of seizure by a government or other public authority. The word is also used, popularly, of spoliation under legal forms, ...

of church property

*abolition of theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

as a course of study in universities

*banning school prayer

*banning compulsory religious instruction in schools

*prohibiting schools from requiring attendance at worship services

After storms of protests from both Protestants and Catholics, Hoffmann was forced to resign and, by political means, the churches were able to prevent complete disestablishment. A compromise was reached — one which favored the Protestant church establishment. There would no longer be state churches, but the churches remained public corporations and retained their subsidies from the state governments for services they performed on behalf of the government (running hospitals, kindergartens etc.). In turn, on behalf of the churches, the state governments collected church fees from those taxpayers enlisted as parishioners and distributed these funds to the churches. These fees were, and still are, used to finance church activities and administration. The theological faculties in the universities continued to exist, as did religious instruction in the schools, however, allowing the parents to opt out for their children. The rights formerly held by the monarchs in the German Empire simply devolved to church councils instead, and the high-ranking church administrators — who had been civil servants in the Empire — simply became church officials instead. The governing structure of the churches effectively changed with the introduction of chairpersons elected by church synods instead of being appointed by the state.

Accordingly, in this initial period of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is ...

, in 1922, the Protestant Church in Germany formed the German Evangelical Church Confederation The German Evangelical Church Confederation (german: Deutscher Evangelischer Kirchenbund, abbreviated DEK) was a formal federation of 28 regional Protestant churches ('' Landeskirchen'') of Lutheran, Reformed or United Protestant administration or ...

of 28 regional (or provincial) churches (german: link=no, Landeskirchen), with their regional boundaries more or less delineated by those of the federal states. This federal system allowed for a great deal of regional autonomy in the governance of German Protestantism, as it allowed for a national church parliament that served as a forum for discussion and that endeavored to resolve theological

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the s ...

and organizational conflicts.

The Nazi regime

Many Protestants voted for the Nazis in the elections of summer and autumn 1932 andMarch 1933

The following events occurred in March 1933:

March 1, 1933 (Wednesday)

*The fictional defense attorney Perry Mason was introduced, along with his secretary Della Street, and detective Paul Drake, in Erle Stanley Gardner's novel, ''The Case ...

. This differed noticeably from Catholic populated areas, where the results of votes cast in favor of the Nazis were lower than the national average, even after the '' Machtergreifung'' ("seizure of power") of Hitler.

, or DNVP. – that idealized the past.

A limited number of Protestants, such as Karl Barth, Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (; 4 February 1906 – 9 April 1945) was a German Lutheran pastor, theologian and anti-Nazi dissident who was a key founding member of the Confessing Church. His writings on Christianity's role in the secular world have ...

and Wilhelm Busch

Heinrich Christian Wilhelm Busch (14 April 1832 – 9 January 1908) was a German humorist, poet, illustrator, and painter. He published wildly innovative illustrated tales that remain influential to this day.

Busch drew on the tropes of f ...

, objected to the Nazis on moral and theological principles; they could not reconcile the Nazi state's claim to total control over the person with the ultimate sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

that, in Christian orthodoxy, must belong only to God.

German Christians

The German Christian movement in the Protestant Church developed in the late Weimar period. They were, for the most part, a "group of fanatic Nazi Protestants"''Barnes'' p. 74 who were organized in 1931 to help win elections of Elder (Christianity), presbyters and synodals of the old-Prussian church (last free election on 13 November 1932). In general, the group's political and religious motivations developed in response to the social and political tensions wrought by the end of World War I and the attendant substitution of a republicanism, republican regime for the authoritarian one of Wilhelm II, German Emperor, Wilhelm II — much the same as the conditions leading to Adolf Hitler's rise to power, Hitler's rise to power. The German Christian movement was sustained and encouraged by factors such as: *the 400th anniversary (in 1917) of Martin Luther's posting of the Ninety-five Theses in 1517, an event which served to endorse German nationalism, to emphasize that Germany had a preferred place in the Protestant tradition, and to legitimize antisemitism. This was reinforced by the Luther Renaissance Movement of Professor Emmanuel Hirsch. The extreme and shocking Martin Luther and antisemitism, antisemitism of Martin Luther came to light rather late in his life, but had been a consistent theme in Christian Germany for centuries thereafter. *the revival of ''völkisch'' traditions *the de-emphasis of the Old Testament in Protestant theology, and the removal of parts deemed "too Jewish", replacing the New Testament with a dejudaized version entitled ''Die Botschaft Gottes'' (The Message of God) *the respect for temporal (secular) authority, which had been emphasized by Luther and has arguable scriptural support (Epistle to the Romans, Romans 13) "For German Christians, race was the fundamental principle of human life, and they interpreted and effected that notion in religious terms. German Christianity emphasized the distinction between the visible and invisible church. For the German Christians, the church on earth was not the fellowship of the holy spirit described in the New Testament but a contrast to it, a vehicle for the expression of race and ethnicity". The German Christians were sympathetic to the Nazi regime's goal of "co-ordinating" the individual Protestant churches into a single and uniform Reich church, consistent with the ''Volk'' ethos and the ''Führerprinzip''.Creating a New National Church (''Deutsche Evangelische Kirche'')

When the Nazis took power, the German Protestant church consisted of a federation of independent regional churches which included Lutheran, Reformed and United traditions. In late April 1933 the leadership of the Protestant federation agreed to write a new constitution for a new "national" church, theGerman Evangelical Church

The German Evangelical Church (german: Deutsche Evangelische Kirche) was a successor to the German Evangelical Church Confederation from 1933 until 1945.

The German Christians, an antisemitic and racist pressure group and ''Kirchenpartei'', ga ...

(german: link=no, Deutsche Evangelische Kirche or DEK). This had been one goal of many German Christians for some time, as centralization would enhance the coordination of Church and State, as a part of the overall Nazi process of Gleichschaltung ("coordination", resulting in co-option). These German Christians agitated for Hitler's advisor on religious affairs, Ludwig Müller, to be elected as the new Church's bishop (german: link=no, Reichsbischof).

Müller had poor political skills, little political support within the Church and no real qualifications for the job, other than his commitment to Nazism and a desire to exercise power. When the federation council met in May 1933 to approve the new constitution, it elected Friedrich von Bodelschwingh, Friedrich von Bodelschwingh the Younger as ''Reichsbischof'' of the new Protestant Reich Church by a wide margin, largely on the advice and support of the leadership of the 28 church bodies.Bodelschwingh was a well-known and popular Westphalian pastor who headed Bethel Institution, a large charitable organization for the mentally ill and disabled. His father, also a pastor, had founded Bethel. ''Barnett'' p. 33.

Hitler was infuriated with the rejection of his candidate, and after a series of political maneuvers, Bodelschwingh resigned and Müller was elected as the new ''Reichsbischof'' on 27 September 1933, after the government had already imposed him on 28 June 1933. The formidable propaganda apparatus of the Nazi state was deployed to help the German Christians win presbyter and synodal elections in order to dominate the upcoming synod and finally put Müller into office. Hitler discretionarily decreed unconstitutional premature re-elections of all presbyters and synodals for 23 July; the night before the elections, Hitler made a personal appeal to Protestants by radio.

The German Christians won handily (70–80% of all seats in presbyteries and synods), except in four regional churches and one provincial body of the united old-Prussian church: the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria, Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria right of the river Rhine ("right" meaning "east of"), the Evangelical Lutheran State Church of Hanover, Evangelical Reformed Church in Bavaria and Northwestern Germany, Evangelical Reformed State Church of the Province of Hanover the Lutheran Evangelical State Church in Württemberg, and in the Evangelical Church of Westphalia, old-Prussian ecclesiastical province of Westphalia, where the German Christians gained no majorities. Among adherents of the Confessing Church these church bodies were termed ''intact churches'' (german: :de:Intakte Kirchen, Intakte Kirchen), as opposed to the German Christian-ruled bodies which they designated as "destroyed churches" (german: link=no, zerstörte Kirchen). This electoral victory enabled the German Christians to secure sufficient delegates to prevail at the so-called ''national synod'' that conducted the "revised" September election for ''Reichsbischof''. Further pro-Nazi developments followed the elevation of Müller to the bishopric: in late summer the old-Prussian church (led by Müller since his government appointment on 6 July 1933) adopted the Aryan Paragraph, effectively defrocking clergy of Jewish descent and even clergy married to non-Aryans.

Hitler was infuriated with the rejection of his candidate, and after a series of political maneuvers, Bodelschwingh resigned and Müller was elected as the new ''Reichsbischof'' on 27 September 1933, after the government had already imposed him on 28 June 1933. The formidable propaganda apparatus of the Nazi state was deployed to help the German Christians win presbyter and synodal elections in order to dominate the upcoming synod and finally put Müller into office. Hitler discretionarily decreed unconstitutional premature re-elections of all presbyters and synodals for 23 July; the night before the elections, Hitler made a personal appeal to Protestants by radio.

The German Christians won handily (70–80% of all seats in presbyteries and synods), except in four regional churches and one provincial body of the united old-Prussian church: the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria, Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria right of the river Rhine ("right" meaning "east of"), the Evangelical Lutheran State Church of Hanover, Evangelical Reformed Church in Bavaria and Northwestern Germany, Evangelical Reformed State Church of the Province of Hanover the Lutheran Evangelical State Church in Württemberg, and in the Evangelical Church of Westphalia, old-Prussian ecclesiastical province of Westphalia, where the German Christians gained no majorities. Among adherents of the Confessing Church these church bodies were termed ''intact churches'' (german: :de:Intakte Kirchen, Intakte Kirchen), as opposed to the German Christian-ruled bodies which they designated as "destroyed churches" (german: link=no, zerstörte Kirchen). This electoral victory enabled the German Christians to secure sufficient delegates to prevail at the so-called ''national synod'' that conducted the "revised" September election for ''Reichsbischof''. Further pro-Nazi developments followed the elevation of Müller to the bishopric: in late summer the old-Prussian church (led by Müller since his government appointment on 6 July 1933) adopted the Aryan Paragraph, effectively defrocking clergy of Jewish descent and even clergy married to non-Aryans.

The Confessing Church

Formation

The Aryan Paragraph created a furor among some of the clergy. Under the leadership of Martin Niemöller, the Pfarrernotbund, Pastors' Emergency League (''Pfarrernotbund'') was formed, presumably for the purpose of assisting clergy of Jewish descent, but the League soon evolved into a locus of dissent against Nazi interference in church affairs. Its membership grewBy the end of 1933 the League already had 6,000 members. ''Barnett'' p. 35. while the objections and rhetoric of the German Christians escalated.

The League pledged itself to contest the state's attempts to infringe on the confessional freedom of the churches, that is to say, their ability to determine their own doctrine. It expressly opposed the adoption of the Aryan Paragraph which changed the meaning of baptism. It distinguished between Jews and Christians of Jewish descent and insisted, consistent with the demands of orthodox Christianity, that converted Jews and their descendants were as Christian as anyone else and were full members of the Church in every sense.

At this stage, the objections of Protestant leaders were primarily motivated by the desire for church autonomy and church/state demarcation rather than opposition to the persecution of non-Christian Jews, which was only just beginning. Eventually, the League evolved into the Confessing Church.

On 13 November 1933 a rally of German Christians was held at the Berlin Sportpalast, where — before a packed hall — banners proclaimed the unity of National Socialism and Christianity, interspersed with the omnipresent swastikas. A series of speakers addressed the crowd's pro-Nazi sentiments with ideas such as:

*the removal of all pastors unsympathetic with National Socialism

*the expulsion of members of Jewish descent, who might be arrogated to a separate church

*the implementation of the Aryan Paragraph church-wide

*the Marcionism, removal of the Old Testament from the Bible

*the removal of "non-German" elements from religious services

*the adoption of a more "heroic" and "positive" interpretation of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, who in pro-Aryan race#Nazism, Aryan fashion should be portrayed to be battling mightily against corrupt Jewish influences.

This rather shocking attempt to rally the pro-Nazi elements among the German Christians backfired, as it now appeared to many Protestants that the State was attempting to intervene in the most central theological matters of the church, rather than only in matters of church organization and polity.

While Hitler, a consummate politician, was sensitive to the implications of such developments, Ludwig Müller (theologian), Ludwig Müller was apparently not: he fired and transferred pastors adhering to the Emergency League, and in April 1934 actually deposed the heads of the Württembergian church (Bishop Theophil Wurm) and of the Bavarian church (Bishop Hans Meiser). They and the synodals of their church bodies continuously refused to declare the merger of their church bodies in the German Evangelical Church (DEK). The continuing aggressiveness of the DEK and Müller spurred the schismatic Protestant leaders to further action.

The Aryan Paragraph created a furor among some of the clergy. Under the leadership of Martin Niemöller, the Pfarrernotbund, Pastors' Emergency League (''Pfarrernotbund'') was formed, presumably for the purpose of assisting clergy of Jewish descent, but the League soon evolved into a locus of dissent against Nazi interference in church affairs. Its membership grewBy the end of 1933 the League already had 6,000 members. ''Barnett'' p. 35. while the objections and rhetoric of the German Christians escalated.

The League pledged itself to contest the state's attempts to infringe on the confessional freedom of the churches, that is to say, their ability to determine their own doctrine. It expressly opposed the adoption of the Aryan Paragraph which changed the meaning of baptism. It distinguished between Jews and Christians of Jewish descent and insisted, consistent with the demands of orthodox Christianity, that converted Jews and their descendants were as Christian as anyone else and were full members of the Church in every sense.

At this stage, the objections of Protestant leaders were primarily motivated by the desire for church autonomy and church/state demarcation rather than opposition to the persecution of non-Christian Jews, which was only just beginning. Eventually, the League evolved into the Confessing Church.

On 13 November 1933 a rally of German Christians was held at the Berlin Sportpalast, where — before a packed hall — banners proclaimed the unity of National Socialism and Christianity, interspersed with the omnipresent swastikas. A series of speakers addressed the crowd's pro-Nazi sentiments with ideas such as:

*the removal of all pastors unsympathetic with National Socialism

*the expulsion of members of Jewish descent, who might be arrogated to a separate church

*the implementation of the Aryan Paragraph church-wide

*the Marcionism, removal of the Old Testament from the Bible

*the removal of "non-German" elements from religious services

*the adoption of a more "heroic" and "positive" interpretation of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, who in pro-Aryan race#Nazism, Aryan fashion should be portrayed to be battling mightily against corrupt Jewish influences.

This rather shocking attempt to rally the pro-Nazi elements among the German Christians backfired, as it now appeared to many Protestants that the State was attempting to intervene in the most central theological matters of the church, rather than only in matters of church organization and polity.

While Hitler, a consummate politician, was sensitive to the implications of such developments, Ludwig Müller (theologian), Ludwig Müller was apparently not: he fired and transferred pastors adhering to the Emergency League, and in April 1934 actually deposed the heads of the Württembergian church (Bishop Theophil Wurm) and of the Bavarian church (Bishop Hans Meiser). They and the synodals of their church bodies continuously refused to declare the merger of their church bodies in the German Evangelical Church (DEK). The continuing aggressiveness of the DEK and Müller spurred the schismatic Protestant leaders to further action.

Barmen Declaration of Faith

In May 1934, the opposition met in a church synod in Barmen. The rebellious pastors denounced Müller and his leadership and declared that they and their congregations constituted the true Evangelical Church of Germany. The Barmen Declaration, primarily authored by Karl Barth, with the consultation and advice of other protesting pastors like Martin Niemöller and individual congregations, re-affirmed that the German Church was not an "organ of the State" and that the concept of State control over the Church was doctrinally false. The Declaration stipulated, at its core, that any State — even the totalitarian one — necessarily encountered a limit when confronted with God's commandments. The Barmen declaration became in fact the foundation of the Confessing Church, confessing because it was based on a confession of faith. After the Barmen Declaration, there were in effect two opposing movements in the German Protestant Church: *the German Christian movement and *the Confessing Church (the ''Bekennende Kirche'', BK), often naming itself ''Deutsche Evangelische Kirche'' too, in order to reinforce its claim to be the true church It should nevertheless be emphasized that the Confessing Church's rebellion was directed at the regime's ecclesiastical policy, and the German Christian movement, not at its overall political and social objectives.Post-Barmen

The situation grew complex after Barmen. Müller's ineptitude in political matters did not endear him to the Führer. Furthermore, the Sportpalast speech had proved a public relations disaster; the Nazis, who had promised "freedom of religion" in point 24 of their National Socialist Program, 25-point program, now appeared to be dictating religious doctrine. Hitler sought to defuse the situation in the autumn of 1934 by lifting the house arrest of Meiser and Wurm, leaders of the Bavarian and Württembergian Lutheran churches, respectively. Having lost his patience with Müller in particular and the German Christians in general, he removed Müller's authority, brought ''Gleichschaltung'' to a temporary halt and created a new Reich Ministry – aptly named Church Affairs – under Hanns Kerrl, one of Hitler's lawyer friends. The ''Kirchenkampf'' ("church struggle") would now be continued on the basis of Church against State, rather than internally between two Political faction, factions of a single church. Kerrl's charge was to attempt another coordination, hopefully with more tact than the heavy-handed Müller. Kerrl was more mild-mannered than the somewhat vulgar Müller, and was also politically astute; he shrewdly appointed a committee of conciliation, to be headed by Wilhelm Zoellner, a retired Westphalian Superintendent (ecclesiastical), general superintendent who was generally respected within the church and did not identify with any one faction. Müller himself resigned, more or less in disgrace, at the end of 1935, having failed to integrate the Protestant church and in fact having created somewhat of a rebellion. Martin Niemöller's group generally cooperated with the new Zoellner committee, but still maintained that it represented the true Protestant Church in Germany and that the DEK was, to put it more bluntly than Niemöller would in public, no more than a collection of heretics. The Confessing Church, under the leadership of Niemöller, addressed a polite, but firm, memorandum to Hitler in May 1936. The memorandum protested the regime's anti-Christian tendencies, denounced the regime's antisemitism and demanded that the regime terminate its interference with the internal affairs of the Protestant church. This was essentially the proverbial straw that broke the back of the camel. The regime responded by: * arresting several hundred dissenting pastors * murdering Dr. Friedrich Weißler, office manager and legal advisor of the "second preliminary church executive" of the Confessing Church, in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp * confiscating the funds of the Confessing Church * forbidding the Confessing Church from taking up collections of offertories Eventually, the Nazi tactics of repression were too much for Zoellner to bear and he resigned on 12 February 1937, after the Gestapo had denied him the right to visit some imprisoned pastors. The Minister of Church Affairs spoke to the churchmen the next day in a shocking presentation that clearly disclosed the regime's hostility to the church:A resistance movement?

The Barmen Declaration itself did not mention the Nazi persecution of Jews or other totalitarian measures taken by the Nazis; it was a declaration of ecclesiastical independence, consistent with centuries of Protestant doctrine. It was not a statement of rebellion against the regime or its political and social doctrines and actions. The Confessing Church engaged in only one form of unified resistance: resistance to state manipulation of religious affairs. While many leaders of the Confessing Church attempted to persuade the church to take a radical stance in opposition to Hitler, it never adopted this policy.Aftermath

Some of the leaders of the Confessing Church, such as Martin Niemöller and Heinrich Grüber, were sent to Nazi concentration camps. While Grüber and Niemöller survived, not all did:Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (; 4 February 1906 – 9 April 1945) was a German Lutheran pastor, theologian and anti-Nazi dissident who was a key founding member of the Confessing Church. His writings on Christianity's role in the secular world have ...

was sent initially to Tegel Prison, then to Buchenwald concentration camp, and finally to Flossenbürg concentration camp, where he was hanged. This left Christians who did not agree with the Nazis without leadership for much of the era.

A select few of the Confessing Church risked their lives to help Jews hiding illegally in Berlin during the war. A hat would be passed around at the end of secret meetings into which the congregation would donate identity cards and passbooks. These were then modified by forgers and given to underground Jews so they could pass as legal Berlin citizens.''See generally'' ''Schonhaus''. Several members of the Confessing Church were caught and tried for their part in creating forged papers, including Franz Kaufmann who was shot, and Helene Jacobs, who was jailed.

Many of those few Confessing Church members who actively attempted to subvert Hitler's policies were extremely cautious and relatively ineffective. Some urged the need for more radical and risky resistance action. A Berlin Deaconess, , showed courage and offered "perhaps the most impassioned, the bluntest, the most detailed and most damning of the protests against the silence of the Christian churches" because she went the furthest in speaking on behalf of the Jews. Another Confessing Church member who was notable for speaking out against anti-Semitism was Hans Ehrenberg.

Meusel and two other leading women members of the Confessing Church in Berlin, Elisabeth Schmitz and , were members of the Berlin parish where Martin Niemöller served as pastor. Their efforts to prod the church to speak out for the Jews were unsuccessful.

Meusel and Bonhoeffer condemned the failure of the Confessing Church – which was organized specifically in resistance to governmental interference in religion – to move beyond its very limited concern for religious civil liberties and to focus instead on helping the suffering Jews. In 1935 Meusel protested the Confessing Church's timid action:

Karl Barth also wrote in 1935: "For the millions that suffer unjustly, the Confessing Church does not yet have a heart".

The Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt, was a declaration issued on 19 October 1945 by the Council of the Evangelical Church in Germany (Evangelischen Kirche in Deutschland or EKD), in which it confessed guilt for its inadequacies in opposition to the Nazis. It was written mainly by former members of Confessing Church.

The Nazi policy of interference in Protestantism did not achieve its aims. A majority of German Protestants sided neither with ''Deutsche Christen'', nor with the Confessing Church. Both groups also faced significant internal disagreements and division. The Nazis gave up trying to co-opt Christianity and instead expressed contempt toward it. When German Christians persisted, some members of the SS found it hard to believe that they were sincere and even thought they might be a threat."The Nazis eventually gave up their attempt to co-opt Christianity, and made little pretence at concealing their contempt for Christian beliefs, ethics and morality. Unable to comprehend that some Germans genuinely wanted to combine commitment to Christianity and Nazism, some members of the SS even came to view German Christians as almost more of a threat than the Confessing Church." Mary Fulbrook, ''The Fontana History of Germany 1918–1990: The Divided Nation'', Fontana Press, 1991, p. 81

See also

* Günther Dehn * KirchenkampfReferences

Notes Bibliography * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Lutheran educational website

* {{Authority control Christian movements Christian organizations established in 1933 1933 in Germany German resistance to Nazism Lutheran theology History of Lutheranism in Germany Christian denominations founded in Germany Former Christian denominations Protestant denominations established in the 20th century Nazi Germany and Protestantism 1933 establishments in Germany Dietrich Bonhoeffer Karl Barth Kirchenkampf Persecution of Protestants