The Battles of Latrun were a series of military engagements between the

Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the Israel, State of Israel. It consists of three servic ...

and the

Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

ian

Arab Legion

The Arab Legion () was the police force, then regular army of the Emirate of Transjordan, a British protectorate, in the early part of the 20th century, and then of independent Jordan, with a final Arabization of its command taking place in 1 ...

on the outskirts of

Latrun

Latrun ( he, לטרון, ''Latrun''; ar, اللطرون, ''al-Latrun'') is a strategic hilltop in the Latrun salient in the Ayalon Valley, and a depopulated Palestinian village. It overlooks the road between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, 25 kilometers ...

between 25 May and 18 July 1948, during the

1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

. Latrun takes its name from the monastery close to the junction of two major highways: Jerusalem to Jaffa/Tel Aviv and Gaza to Ramallah. During the

British Mandate it became a

Palestine Police

The Palestine Police Force was a British colonial police service established in Mandatory Palestine on 1 July 1920,Sinclair, 2006. when High Commissioner Sir Herbert Samuel's civil administration took over responsibility for security from Gener ...

base with a

Tegart fort

A Tegart fort is a type of militarized police fort constructed throughout Palestine during the British Mandatory period, initiated as a measure against the 1936–1939 Arab Revolt.

Etymology

The forts are named after their designer, British po ...

. The United Nations

Resolution 181

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as R ...

placed this area within the proposed Arab state. In May 1948, it was under the control of the

Arab Legion

The Arab Legion () was the police force, then regular army of the Emirate of Transjordan, a British protectorate, in the early part of the 20th century, and then of independent Jordan, with a final Arabization of its command taking place in 1 ...

. It commanded the only road linking the

Yishuv

Yishuv ( he, ישוב, literally "settlement"), Ha-Yishuv ( he, הישוב, ''the Yishuv''), or Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri ( he, הישוב העברי, ''the Hebrew Yishuv''), is the body of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel (corresponding to the ...

-controlled area of

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

to

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, giving Latrun strategic importance in the battle for Jerusalem.

Despite assaulting Latrun on five separate occasions Israel was ultimately unable to capture Latrun, and it remained under Jordanian control until the

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 ...

. The battles were such a decisive Jordanian victory that the Israelis decided to construct a bypass surrounding Latrun so as to allow vehicular movement between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, thus avoiding the main road. Regardless, during the

Battle for Jerusalem

The Battle for Jerusalem took place during the 1947–1948 civil war phase of the 1947–1949 Palestine war. It saw Jewish and Arab militias in Mandatory Palestine, and later the militaries of Israel and Transjordan, fight for control over ...

, the Jewish population of Jerusalem could still be supplied by a new road, named the "

Burma Road

The Burma Road () was a road linking Burma (now known as Myanmar) with southwest China. Its terminals were Kunming, Yunnan, and Lashio, Burma. It was built while Burma was a British colony to convey supplies to China during the Second S ...

", that bypassed Latrun and was suitable for

convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

s. The Battle of Latrun left its imprint on the Israeli collective imagination and constitutes part of the "

founding myth

An origin myth is a myth that describes the origin of some feature of the natural or social world. One type of origin myth is the creation or cosmogonic myth, a story that describes the creation of the world. However, many cultures have sto ...

" of the Jewish State.

[ ] The attacks cost the lives of 168 Israeli soldiers, but some accounts inflated this number to as many as 2,000. The combat at Latrun also carries a symbolic significance because of the participation of

Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

survivors.

Today, the battleground site has an Israeli military museum dedicated to the Israeli Armored Corps and a memorial to the

1947–1949 Palestine war

The 1948 Palestine war was fought in the territory of what had been, at the start of the war, British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. It is known in Israel as the War of Independence ( he, מלחמת העצמאות, ''Milkhemet Ha'Atzma'ut'') and ...

.

Background

1948 Arab–Israeli War

After the adoption of the

United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as R ...

in November 1947, a

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

erupted in the

British Mandate of Palestine British Mandate of Palestine or Palestine Mandate most often refers to:

* Mandate for Palestine: a League of Nations mandate under which the British controlled an area which included Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan.

* Mandatory P ...

. The Jews living in Jerusalem constituted one of the weak points of the

Yishuv

Yishuv ( he, ישוב, literally "settlement"), Ha-Yishuv ( he, הישוב, ''the Yishuv''), or Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri ( he, הישוב העברי, ''the Hebrew Yishuv''), is the body of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel (corresponding to the ...

and a main cause for concern to its leaders. With nearly 100,000 inhabitants, a sixth of the total Jewish population in the Mandate, the city was isolated in the heart of territory under Arab control.

[See War of the roads and blockade of Jerusalem and ]Operation Nachshon

Operation Nachshon ( he, מבצע נחשון, ''Mivtza Nahshon'') was a Jewish military operation during the 1948 war. Lasting from 5–16 April 1948, its objective was to break the Siege of Jerusalem by opening the Tel Aviv – Jerusalem road ...

.

In January, in the context of the "War of the Roads", the

Holy War Army

The Army of the Holy War or Holy War Army ( ar, جيش الجهاد المقدس; ''Jaysh al-Jihād al-Muqaddas'') was a Palestinian Arab irregular force in the 1947-48 Palestinian civil war led by Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni and Hasan Salama. The ...

of

Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni

Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni ( ar, عبد القادر الحسيني), also spelled Abd al-Qader al-Husseini (1907 – 8 April 1948) was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and fighter who in late 1933 founded the secret militant group known as the Orga ...

besieged the Jewish part of the city and stopped convoys passing between

Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

and Jerusalem. By the end of March, the tactic proved its worth and the city was cut off. The

Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the I ...

then launched ''Operation Nachshon'', 4–20 April, and managed to force through a number of

large convoys.

Following the death of Abd al-Qader al-Husayni at

al-Qastal

Al-Qastal ("Kastel", ar, القسطل) was a Palestinian village located eight kilometers west of Jerusalem and named for a Crusader castle located on the hilltop. Used in 1948 during the Arab-Israeli War as a military base by the Army of th ...

, the

Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

's military committee ordered the other Arab force in Palestine, the

Arab Liberation Army

The Arab Liberation Army (ALA; ar, جيش الإنقاذ العربي ''Jaysh al-Inqadh al-Arabi''), also translated as Arab Salvation Army, was an army of volunteers from Arab countries led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji. It fought on the Arab side in the ...

, to move its forces from

Samaria

Samaria (; he, שֹׁמְרוֹן, translit=Šōmrōn, ar, السامرة, translit=as-Sāmirah) is the historic and biblical name used for the central region of Palestine, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The first ...

(the northern part of today's

West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

) to the road of Jerusalem and the areas of Latrun,

Ramla

Ramla or Ramle ( he, רַמְלָה, ''Ramlā''; ar, الرملة, ''ar-Ramleh'') is a city in the Central District of Israel. Today, Ramle is one of Israel's mixed cities, with both a significant Jewish and Arab populations.

The city was f ...

, and Lydda.

[Gelber (2006), p. 95.]

In the middle of May, the situation for the 50,000 Arab inhabitants of the city and the 30,000–40,000 in the outlying neighbourhoods was no better. After the

massacre at Deir Yassin and the Jewish offensive of April that triggered the

large-scale exodus of the Palestinian Arabs in other mixed cities, the Arab population of Jerusalem was frightened and feared for its fate. With the departure of the British on 14 May, the Haganah launched several operations to take control of the city and the local Arab leadership requested

King Abdullah of Jordan to deploy his army to come to their aid.

On 15 May, the situation in the newly declared State of Israel and the remnants of Palestine was chaotic with the British leaving. The Jewish forces gained advantage over the Arab forces, but they feared the intervention of the Arab armies that had been announced for that day.

[ Yoav Gelber (2006), pp. 138–145.]

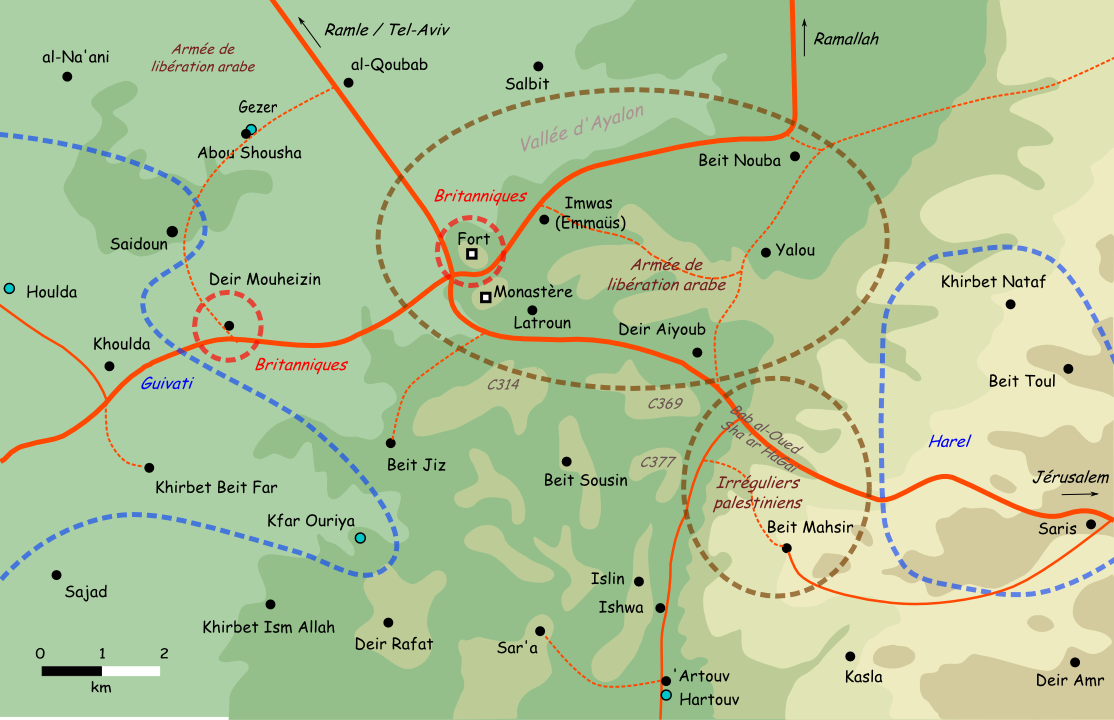

Geography

Latrun

Latrun ( he, לטרון, ''Latrun''; ar, اللطرون, ''al-Latrun'') is a strategic hilltop in the Latrun salient in the Ayalon Valley, and a depopulated Palestinian village. It overlooks the road between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, 25 kilometers ...

is located at the crossroads between the Tel Aviv–Ramla–Jerusalem and Ramallah–Isdud roads in the area allocated to the Arab state by the United Nations Partition Plan. At that point, the Jerusalem road enters the foothills of Judea at

Bab al-Wad

Sha'ar HaGai ( he, שער הגיא) in Hebrew, and Bab al-Wad or Bab al-Wadi in Arabic ( he, באב אל-ואד, ar, باب الواد or ), lit. ''Gate of the Valley'' in both languages, is a point on the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem highway, 23 km ...

(Sha'ar HaGai). The fort dominated the

Valley of Ayalon, and the force that occupied it commanded the road to Jerusalem.

[Se]

this picture of the valley taken from the hills of Latrun

.

In 1948, Latrun comprised a detention camp and a fortified police station occupied by the British,

[ Benny Morris (2008), p. 132.] a

Trappist

The Trappists, officially known as the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance ( la, Ordo Cisterciensis Strictioris Observantiae, abbreviated as OCSO) and originally named the Order of Reformed Cistercians of Our Lady of La Trappe, are a ...

monastery, and several Arab villages: Latrun,

Imwas,

Dayr Ayyub and

Bayt Nuba

Bayt Nuba ( ar, بيت نوبا) was a Palestinian Arab village, located halfway between Jerusalem and al-Ramla. Historically identified with the biblical city of Nob mentioned in the Book of Samuel, that association has been eschewed in modern ti ...

. During the civil war, after the death of Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni, the forces of the Arab Liberation Army positioned themselves around the police fort and the surrounding villages, to the indifference of the British.

They regularly attacked supply convoys heading for Jerusalem. At that time, neither the Israeli nor Jordanian military staffs had prepared for the strategic importance of the place.

Prelude

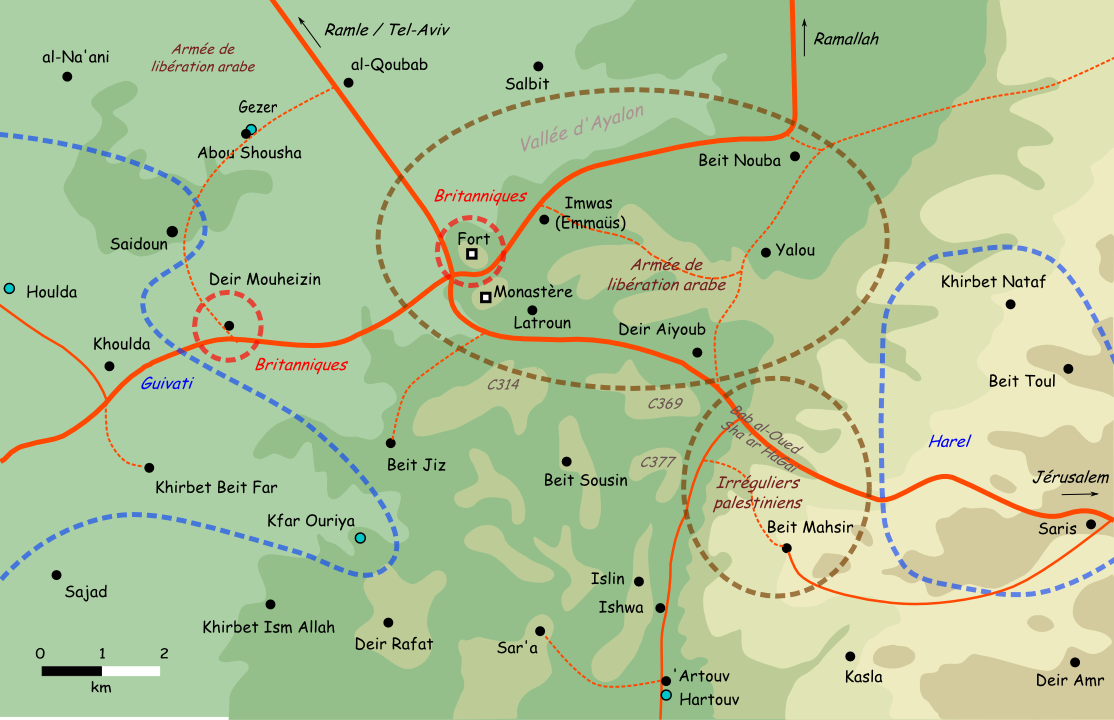

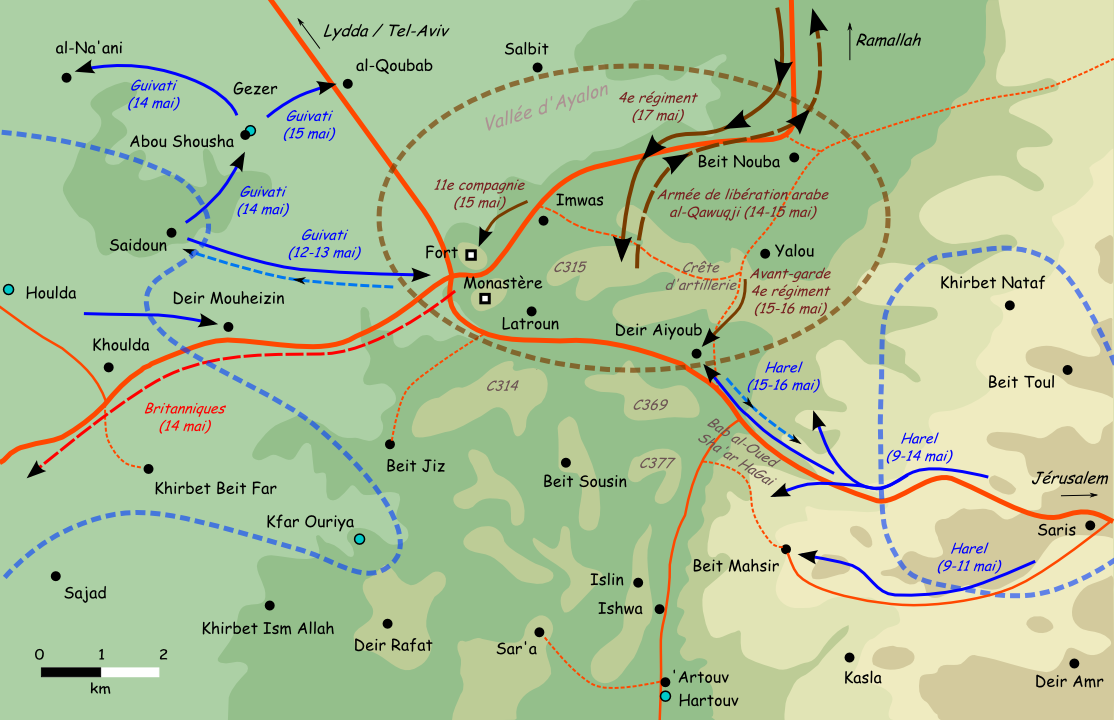

Operation Maccabi (8–16 May)

On 8 May,

Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the I ...

launched Operation Maccabi against the

Arab Liberation Army

The Arab Liberation Army (ALA; ar, جيش الإنقاذ العربي ''Jaysh al-Inqadh al-Arabi''), also translated as Arab Salvation Army, was an army of volunteers from Arab countries led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji. It fought on the Arab side in the ...

and the Palestinian irregulars who occupied several villages along the Jerusalem road and prevented the resupplying of Jerusalem's Jewish community. The

Givati Brigade

The 84th "Givati" Brigade ( he, חֲטִיבַת גִּבְעָתִי, , "Hill Brigade" or "Highland Brigade") is an Israel Defense Forces infantry brigade. Until 2005, the Brigade used to be stationed within the Gaza Strip and primarily perf ...

(on the west side) and

Harel Brigade (on the east side) were engaged in fighting, notably in the Latrun area.

[ Efraïm Karsh (2002), pp. 60–62.]

Between 9–11 May, a battalion of the Harel brigade attacked and took the village of

Bayt Mahsir, used by Palestinians as a base for the control of ''

Bab al-Wad

Sha'ar HaGai ( he, שער הגיא) in Hebrew, and Bab al-Wad or Bab al-Wadi in Arabic ( he, באב אל-ואד, ar, باب الواد or ), lit. ''Gate of the Valley'' in both languages, is a point on the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem highway, 23 km ...

''. The "Sha'ar HaGai" battalion of the Harel brigade also took up a position on the hills north and south of the road. It had to withstand the fire of the Arab Liberation Army artillery and the "unusual"

[It is ]Benny Morris

Benny Morris ( he, בני מוריס; born 8 December 1948) is an Israeli historian. He was a professor of history in the Middle East Studies department of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in the city of Beersheba, Israel. He is a member of ...

who points out. fire of British armoured vehicles, but succeeded in holding the position and entrenched there.

To the west, on 12 May, Givati brigade troops took the British detention camp on the road leading to Latrun, but abandoned it the next day.

[ Ytzhak Levi (1986), detailed chronology of the battle of Jerusalem given at the end of the book.] Between 14 and 15 May, its 52nd battalion took the villages of

Abu Shusha

Abu Shusha ( ar, أبو شوشة) was a Palestinian Arab village in the Ramle Subdistrict of Mandatory Palestine, located 8 km southeast of Ramle. It was depopulated in May 1948.

Abu Shusha was located on the slope of Tell Jezer/Tell el-Ja ...

,

Al-Na'ani and

al-Qubab

Al-Qubab ( ar, القباب) was a Palestinian Arab village in the Ramle Subdistrict. It was depopulated in July 1948 during the Operation Dani led by the Yiftach Brigade.

History

Remains, possibly dating from the Roman era have been found here. ...

north of Latrun, thus cutting off the zone from Ramla, the main Arab town in the area.

Lapierre and

Collins report also that a platoon of the Givati brigade fired on and then penetrated the fort without encountering any resistance on the morning of 15 May.

Again to the east, on 15 May, the troops of the Harel brigade took

Dayr Ayyub, which they abandoned the next day.

It is at this time that the Israeli officers in the field appreciated the strategic importance of Latrun. A report

was sent from OC Harel brigade to OC Palmach that concluded that "The Latrun junction became the main point in the battle

f Jerusalem xact words must be taken from the source but "that appreciation was not shared by the staff one week previously".

[ Benny Morris (2008), p. 463 nn196.] Meanwhile, because of the

Egyptian Army's advance, the Givati brigade got an order to redeploy on a more southern front, and the Harel brigade to remain in the Jerusalem sector.

This decision to leave the area, and the fact of not planning for its strategic importance, would later be a source of controversy between Haganah chief of operations

Yigael Yadin

Yigael Yadin ( he, יִגָּאֵל יָדִין ) (20 March 1917 – 28 June 1984) was an Israeli archeologist, soldier and politician. He was the second Chief of Staff of the Israel Defense Forces and Deputy Prime Minister from 1977 to 1981.

B ...

and

Yitzhak Rabin

Yitzhak Rabin (; he, יִצְחָק רַבִּין, ; 1 March 1922 – 4 November 1995) was an Israeli politician, statesman and general. He was the fifth Prime Minister of Israel, serving two terms in office, 1974–77, and from 1992 until h ...

, commander of the Harel brigade.

The Arab Legion takes control

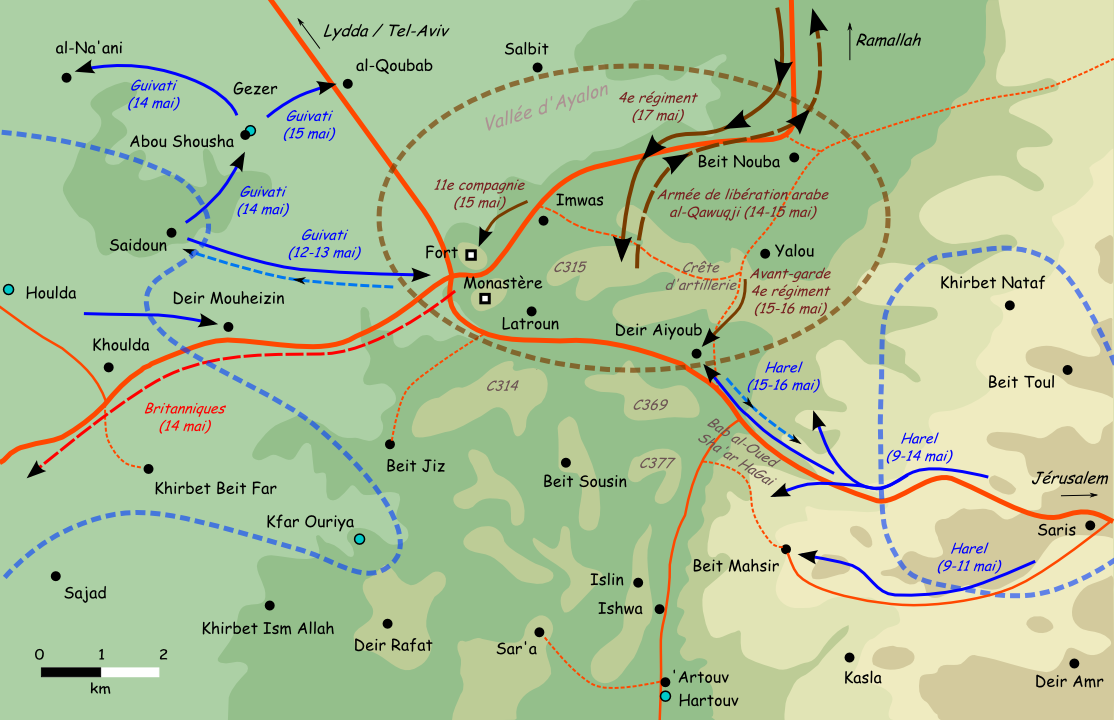

During the confusion of the last days of the British Mandate and with the "entry in war" of the Arab armies, the position at Latrun changed hands without combat.

Firstly, around 14–15 May,

[ Benny Morris (2002), p. 152.] an order was given to

Fawzi al-Qawuqji

Fawzi al-Qawuqji ( ar, فوزي القاوقجي; 19 January 1890 – 5 June 1977) was a leading Arab nationalist military figure in the interwar period.The Arabs and the Holocaust: The Arab-Israeli War of Narratives, by Gilbert Achcar, (NY: Hen ...

and his Arab Liberation Army to withdraw and to leave the place to the

Arab Legion

The Arab Legion () was the police force, then regular army of the Emirate of Transjordan, a British protectorate, in the early part of the 20th century, and then of independent Jordan, with a final Arabization of its command taking place in 1 ...

. According to

Yoav Gelber, this departure occurred before the arrival of the Jordanian troops at Latrun and the position was held by just 200 irregulars.

[ Lapierre et Collins (1971), p. 611.] Benny Morris

Benny Morris ( he, בני מוריס; born 8 December 1948) is an Israeli historian. He was a professor of history in the Middle East Studies department of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in the city of Beersheba, Israel. He is a member of ...

nevertheless points out that a platoon of legionnaires of the 11th Company along with irregulars was there and took over the fort.

[ Benny Morris, (2008), pp. 207–208.]

Indeed, as auxiliary forces of the British in Mandatory Palestine, several elements of the Arab Legion served in Palestine during the Mandate. The British had promised that these units would be withdrawn before the end of April, but for "technical reasons", several companies didn't leave the country.

John Bagot Glubb

Lieutenant-General Sir John Bagot Glubb, KCB, CMG, DSO, OBE, MC, KStJ, KPM (16 April 1897 – 17 March 1986), known as Glubb Pasha, was a British soldier, scholar, and author, who led and trained Transjordan's Arab Legion between 1939 a ...

, the commander of the Arab Legion, formed them into one division with two brigades, each made up of two infantry battalions, in addition to several independent infantry companies. Each battalion was given an armored-car company, and the artillery was made into a separate battalion with three batteries. Another "dummy" brigade was formed to make the Israelis believe it was a reserve brigade, thus deterring them from counterattacking into

Transjordan.

[Pollack (2002), p. 270.]

On 15 May, the Arab states entered the war, and

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

n,

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

i, Jordanian and Egyptian contingents deployed in Palestine. Among these, the Jordanian expeditionary corps was mainly constituted by an elite mechanized force "encadrée" by British officers and named Arab Legion. It comprised:

* the 1st Brigade comprising the 1st and 3rd Battalions in areas that lead to

Nablus

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem, ISO 259-3: ; Samaritan Hebrew: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a populati ...

;

[In the Jordanian expeditionary corps, each ]brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

...

is composed of 2 regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscript ...

s each of them likely composed of 3 or 4 companies. This information is nevertheless "dubious" (sujette à caution ?). The sources are contradictory at that level. The divergences are likely to be due to the fact that the "battalion", which is generally the unit that subdivides the brigade is named ''regiment'' in the Arab Legion.

* the 3rd Brigade under the orders of Colonel Ashton comprising the 2nd Battalion under the orders of Major Geoffrey Lockett

and the 4th battalion under the orders of Lieutenant Colonel

Habes al-Majali that took position at

Ramallah

Ramallah ( , ; ar, رام الله, , God's Height) is a Palestinian city in the central West Bank that serves as the ''de facto'' administrative capital of the State of Palestine. It is situated on the Judaean Mountains, north of Jerus ...

;

* the 5th and 6th Battalions acting independently.

Glubb first realized ("pris conscience") the strategical importance of Latrun in the

Battle of Jerusalem

The Battle of Jerusalem occurred during the British Empire's "Jerusalem Operations" against the Ottoman Empire, in World War I, when fighting for the city developed from 17 November, continuing after the surrender until 30 December 1917, to ...

. His objective was twofold: he wanted to prevent the Israelis from strengthening Jerusalem and from supplying the city, and he wanted to "make a diversion" to keep the strengths of the Haganah far from the city, warranting to the Arabs the control of

East Jerusalem

East Jerusalem (, ; , ) is the sector of Jerusalem that was held by Jordan during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, as opposed to the western sector of the city, West Jerusalem, which was held by Israel.

Jerusalem was envisaged as a separ ...

. In addition to the 11th Company already there, he sent to Latrun the whole 4th Regiment.

[ Benny Morris (2008), p. 219.] During the night between 15 and 16 May, the first contingent of 40 legionnaires seconded by an undetermined number of

Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arabs, Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert ...

s strengthened the position,

and the remainder of the regiment reached the area on 17 May.

Benny Morris

Benny Morris ( he, בני מוריס; born 8 December 1948) is an Israeli historian. He was a professor of history in the Middle East Studies department of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in the city of Beersheba, Israel. He is a member of ...

, ''Histoire revisitée du conflit arabo-sioniste'', Editions complexe, 2003, map p. 241 et pp. 247–255.

On 18 May, the strength of the Arab Legion deployed around Latrun and Bab al-Wad was sufficient, and the road was blocked again.

The Israeli general staff needed several days to assess the actual disposition of the Jordanian forces around Latrun and Jerusalem because these latter were thought to be at several locations in the country.

Situation in Jerusalem

At Jerusalem, after the successful offensives that enabled the Jewish forces to take control of the buildings and strongholds that had been abandoned by the British,

[see ]Operation Kilshon

From 13–18 May 1948 Jewish forces from the Haganah and Irgun executed Operation Kilshon ("Pitchfork"). Its aim was to capture the Jewish suburbs of Jerusalem, particularly Talbiya in central Jerusalem.

Operation

At midnight on Friday 14 May, t ...

. Glubb Pasha

Lieutenant-General Sir John Bagot Glubb, KCB, CMG, DSO, OBE, MC, KStJ, KPM (16 April 1897 – 17 March 1986), known as Glubb Pasha, was a British soldier, scholar, and author, who led and trained Transjordan's Arab Legion between 1939 an ...

sent the 3rd Regiment of the Arab Legion to strengthen the Arab irregulars and fight the Jewish forces. After "violent" fighting, the Jewish positions in the

Old City of Jerusalem

The Old City of Jerusalem ( he, הָעִיר הָעַתִּיקָה, translit=ha-ir ha-atiqah; ar, البلدة القديمة, translit=al-Balda al-Qadimah; ) is a walled area in East Jerusalem.

The Old City is traditionally divided into ...

were threatened (this felt indeed on 28 May).

"We have surrounded the town": on 22 and 23 May, the second Egyptian brigade, composed mainly of several battalions of irregulars and several units of the regular army, reached the southern outskirts of Jerusalem and continued to attack at

Ramat Rachel.

Glubb nevertheless knew that the Israeli army would sooner or later be stronger than his and that he had to prevent the strengthening of the Harel and Etzioni brigades to secure East Jerusalem. He redeployed his strength on 23 May to reinforce the

blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are leg ...

.

[ Benny Morris (2008), Description of the Operation Bin Nun, pp. 221–224.] The Iraqi army, at that time seconded by tanks, relieved the Legion units in northern Samaria and these were redeployed towards the Jerusalem sector. The 2nd Regiment of the Legion moved to Latrun.

A full Jordanian brigade was placed in the area.

On the Israeli side, several leaders of the Jewish city sent emergency telegrams to

David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; he, דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first prime minister of Israel. Adopting the nam ...

where they described the situation as desperate and that they could not hold out more than two weeks.

[ Anita Shapira, ''L'imaginaire d'Israël : histoire d'une culture politique'' (2005), ''Latroun : la mémoire de la bataille'', Chap. III. 1 l'événement pp. 91–96.] Fearing that without a supply the city would collapse, Ben-Gurion ordered the taking of Latrun. This decision seemed strategically necessary but was politically delicate, because Latrun was in the area allocated to the Arab State according to the terms of the

Partition Plan

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as R ...

and this attack was contrary to the

non-aggression agreements, concluded with King Abdullah

[Until the last days preceding the war, the Zionist authorities and the King Abdullah of Jordan maintained a dialogue. Some historians, such as ]Avi Shlaim

Avraham "Avi" Shlaim (born 31 October 1945) is an Israeli- British historian, Emeritus Professor of International Relations at the University of Oxford and fellow of the British Academy. He is one of Israel's New Historians, a group of Israe ...

, consider that this dialogue went up to a tacit non-aggression agreement but this thesis is controversial. This decision was also opposed by the Chief of Operations, Yigael Yadin who considered that there were other military priorities at that moment, in particular on the southern front, where the Egyptian army was threatening Tel Aviv if

Yad Mordechai fell. But Ben-Gurion set Israeli military policy.

[ Lapierre & Collins (1971), events related to the battle of Latrun, pp. 700–706; pp. 720–723; pp. 726–732; pp. 740–741.] This difference in strategy influenced the outcome of the battle, and has been debated in Israel for many years.

[See section #Israeli historiography and collective memory.]

Jewish convoy making its way to Jerusalem below the Latrun Monastery. 1948.

Battles

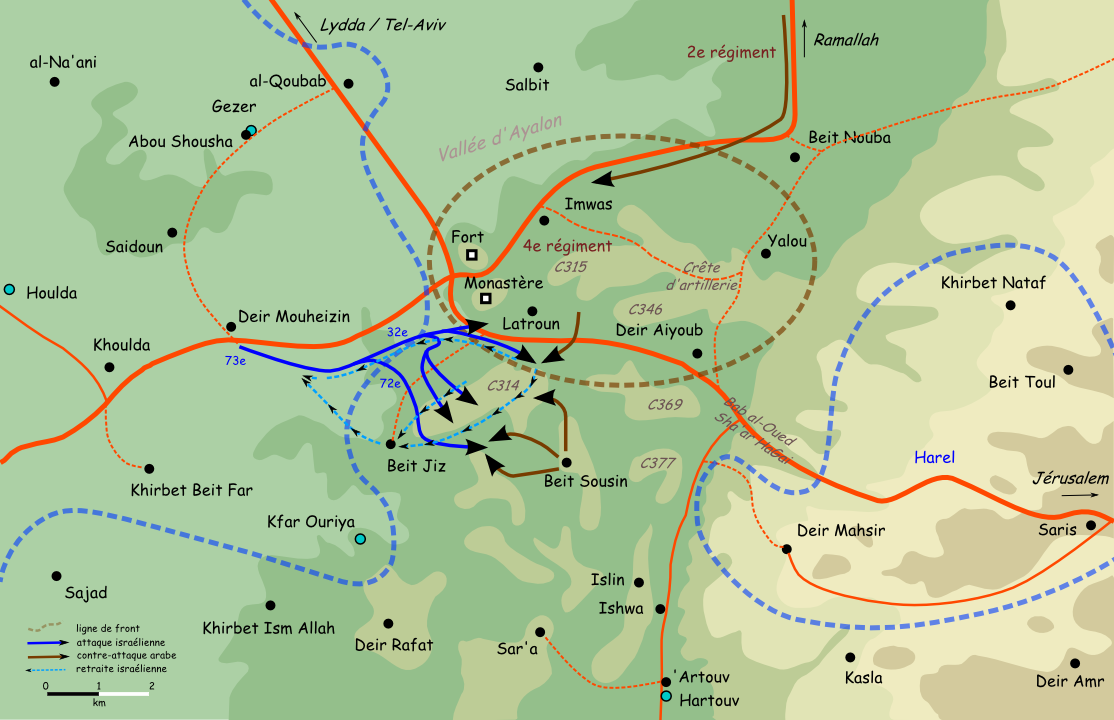

Operation Bin Nun Alef (24–25 May)

The task to lead Operation Bin Nun (''lit.'' Nun's son, in reference to

Joshua

Joshua () or Yehoshua ( ''Yəhōšuaʿ'', Tiberian: ''Yŏhōšuaʿ,'' lit. 'Yahweh is salvation') ''Yēšūaʿ''; syr, ܝܫܘܥ ܒܪ ܢܘܢ ''Yəšūʿ bar Nōn''; el, Ἰησοῦς, ar , يُوشَعُ ٱبْنُ نُونٍ '' Yūšaʿ ...

, Nun's son, conqueror of

Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

according to the

Book of Joshua

The Book of Joshua ( he, סֵפֶר יְהוֹשֻׁעַ ', Tiberian: ''Sēp̄er Yŏhōšūaʿ'') is the sixth book in the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament, and is the first book of the Deuteronomistic history, the story of Isra ...

) was given to

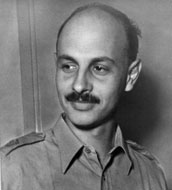

Shlomo Shamir, a former officer of the British army.

His force consisted of 450 men of the

Alexandroni Brigade

The Alexandroni Brigade (3rd Brigade) is an Israel Defense Forces brigade that has fought in multiple Israeli wars. History

Along with the 7th Armoured Brigade both units had 139 killed during the first battle of Latrun (1948), Operation Ben Nu ...

and 1,650 men of the

7th Brigade. Of these, about 140 to 145 were immigrants who had just arrived in Israel, nearly 7% of the total. Their heavy weaponry was limited to two French mortars of 1906 (nicknamed ''

Napoleonchik''), one mortar with 15 rounds of ammunition, one ''

Davidka

The Davidka ( yi, דוידקה, ''"Little David"'' or ''"Made by David"'' ) was a homemade Israeli mortar used in Safed and Jerusalem during 1947–1949 Palestine war. Its bombs were reported to be extremely loud, but very inaccurate and other ...

'',

ten mortars and twelve armored vehicles.

Three hundred soldiers of the

Harel Brigade were also in the area but were not aware of the operation, but assisted after finding out about it by intercepting a radio transmission.

[ Ami Isseroff, site www.mideastweb referring to Yitzhak Levi (1986), ''Nine measures'', p. 266.]

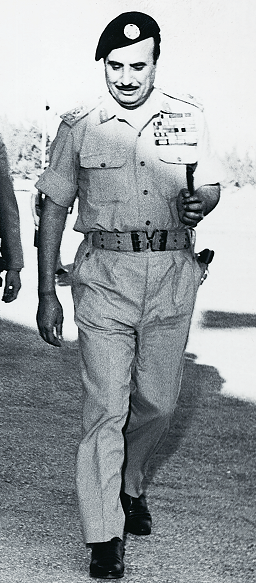

The Jordanian forces were under the order of Lieutenant Colonel

Habes al-Majali.

He "disposed" of the 4th Regiment and 600 Jordanian volunteers seconded by 600 local volunteers. The 2nd Regiment of the brigade, commanded by Major Geoffrey Lockett, had just left Jerusalem and arrived at Latrun during the battle.

The brigade totalled 2,300 men seconded by 800 auxiliaries. It had at its disposal 35 armoured vehicles with 17

Marmon-Herrington Armoured Cars each armed with an anti-tank 2 pounder gun. For artillery it had eight

25 pounder

The Ordnance QF 25-pounder, or more simply 25-pounder or 25-pdr, was the major British field gun and howitzer during the Second World War. Its calibre is 3.45-inch (87.6 mm). It was introduced into service just before the war started, com ...

Howitzers/Field guns,

eight

6 pounder anti-tank guns, ten

2 pounder anti-tank guns also sixteen 3-inch mortars.

Zero Hour (the start of the attack) was first fixed for midnight 23 May, but it was delayed by 24 hours because it had not been possible to gather troops and weapons in time. Because no reconnaissance patrol was made, the Israelis didn't know the exact composition of enemy forces.

Intelligence reports just talked about "local irregular forces".

On 24 May at 19:30, Shlomo Shamir was warned that an enemy force of around 120 vehicles, comprising armoured vehicles and artillery, was probably moving towards Latrun, and urged an attack. The attack was postponed by 2 hours and fixed at 22:00.

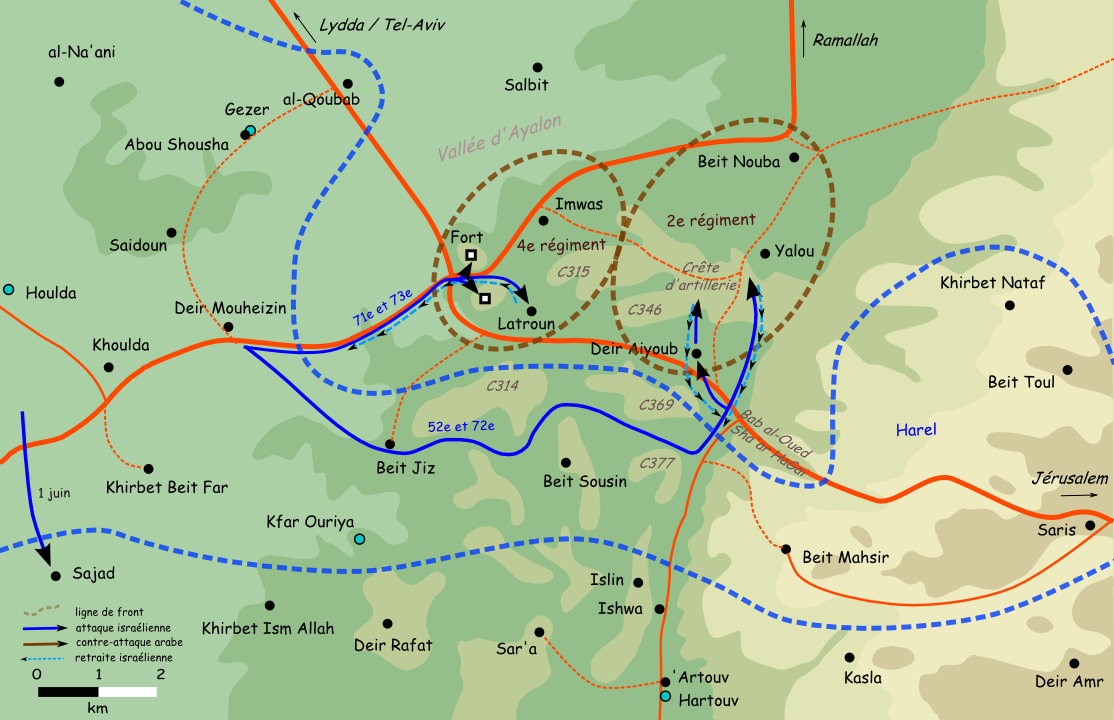

The attack was planned on two axes:

* The battalion of the Alexandroni brigade had to take the town of Latrun, the police fort and then

Imwas in order to block any new Arab reinforcement, and also to protect the passage of supply convoys;

* The 72nd Battalion would circle the position by the south to join the Jerusalem road at the level of Bab al-Wad; it would then cross the road and climb the ridges to take Dayr Ayyub, Yalu and Bayt Nuba, and would ambush there to cover the passage of convoys. It would be supported by three armored cars and two half-tracks of the 73rd Battalion.

During the night, something unexpected happened: a roadblock was found and had to be dismantled, as the brigade had to use the road. Zero hour was once more modified and set at midnight.

At last, the troops fought battle between 2 am and 5 am

but with no benefit of cover. The attackers were rapidly discovered, depriving the Israelis of the surprise effect. The battle started at 4am. The Israeli forces were submitted to a strong fire. The artillery tried to intervene but quickly fell out of ammunition or was not within range to provide counter-battery fire.

[Counter-battery fire is a military tactic in which one targets enemy artillery with one's own artillery.]

Foreseeing the total failure of the attack, Shlomo Shamir ordered a retreat at 11:30 am. As this occurred on open ground under heavy sun, and the soldiers had no water, numerous men were killed or injured by Arab fire. It was only at 2 pm that the first injured men reached the transport they had left in the morning.

However, the Arab Legion didn't take advantage of this victory when, according to Benny Morris, it could easily have performed a counter-attack up to the Israeli headquarters at

Hulda.

Jordanians and Arab irregulars had 5 deaths and 6 injured. The Israelis counted 72 deaths (52 from the 32nd Battalion and 20 from the 72nd Battalion), 6 prisoners and 140 injured.

Ariel Sharon

Ariel Sharon (; ; ; also known by his diminutive Arik, , born Ariel Scheinermann, ; 26 February 1928 – 11 January 2014) was an Israeli general and politician who served as the 11th Prime Minister of Israel from March 2001 until April 2006.

S ...

, the future Prime Minister of Israel, a lieutenant at the time, headed a platoon of the 32nd Battalion and suffered serious injury to his stomach during the battle.

Reorganisation of the central front

At the end of May, David Ben-Gurion was convinced that the Arab Legion expected to take control of all Jerusalem. Moreover, after the fighting, the situation there deteriorated: the Jewish community had very small reserves of fuel, bread, sugar and tea, which would last for only 10 days, and water for 3 months.

[ David Tal (2003) pp. 225–231.] In Glubb's opinion, the aim was still to prevent the Israelis from reinforcing the city and taking control of its Arab part. On 29 May, the

UN Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

announced its intention to impose a

ceasefire for 4 weeks, which would prevent further capture of territory and thus prevent resupplying the besieged city.

[ Benny Morris (2008), Description of the Operation Bin Nun Bet pp. 224–229.]

From a military point of view, the 10th

Harel Brigade required reinforcements and Ben-Gurion dispatched a battalion of the 6th

Etzioni Brigade. He considered it imperative that the 7th Brigade join the forces in Jerusalem as well as a contingent of 400 new recruits to reinforce the Harel Brigade. Weapons and spare parts that had arrived in Israel by air were also now ready for combat on the Jerusalem front.

The commander of the 7th Brigade wished to neutralize the negative effects of the debacle on the morale of the troops and on his prestige.

The central front was reorganized and its command given to an American volunteer fighting on the Israeli side, Colonel

David Marcus, who was subsequently appointed ''

Aluf

''Aluf'' ( he, אלוף, lit=champion or "First\leader of a group" in Biblical Hebrew; ) is a senior military rank in the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) for officers who in other countries would have the rank of general, air marshal, or admiral ...

'' (

Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

).

He took command of the Etzioni and 7th Brigades, and the 10th

Palmach

The Palmach (Hebrew: , acronym for , ''Plugot Maḥatz'', "Strike Companies") was the elite fighting force of the Haganah, the underground army of the Yishuv (Jewish community) during the period of the British Mandate for Palestine. The Palmach ...

Harel Brigade.

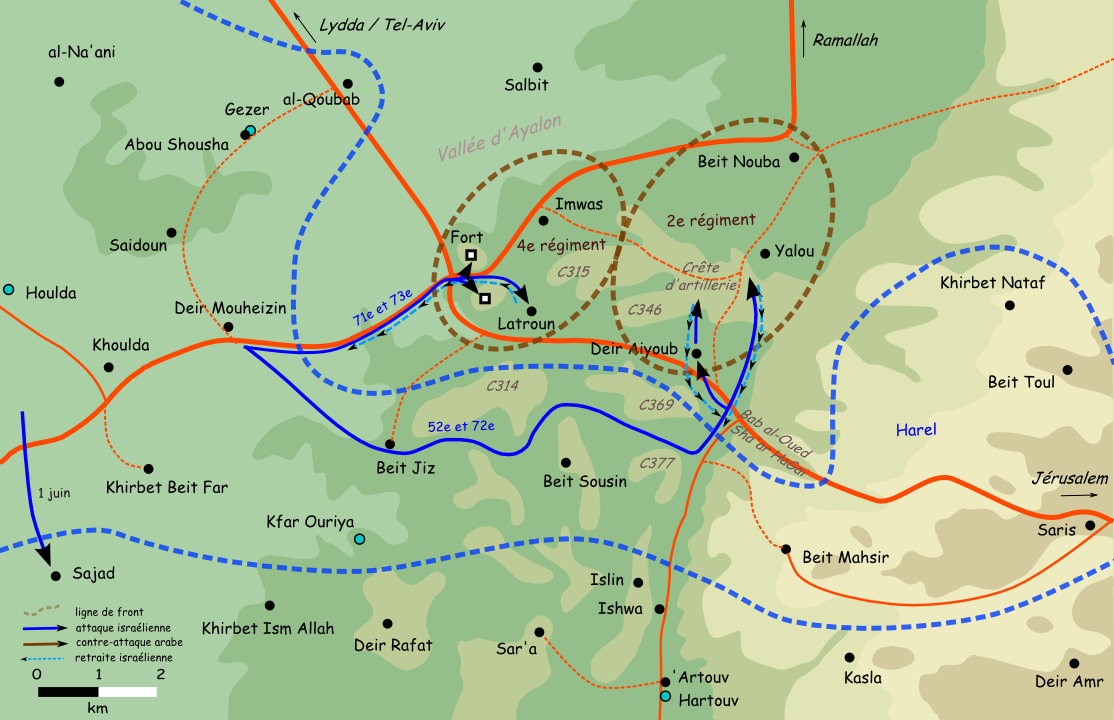

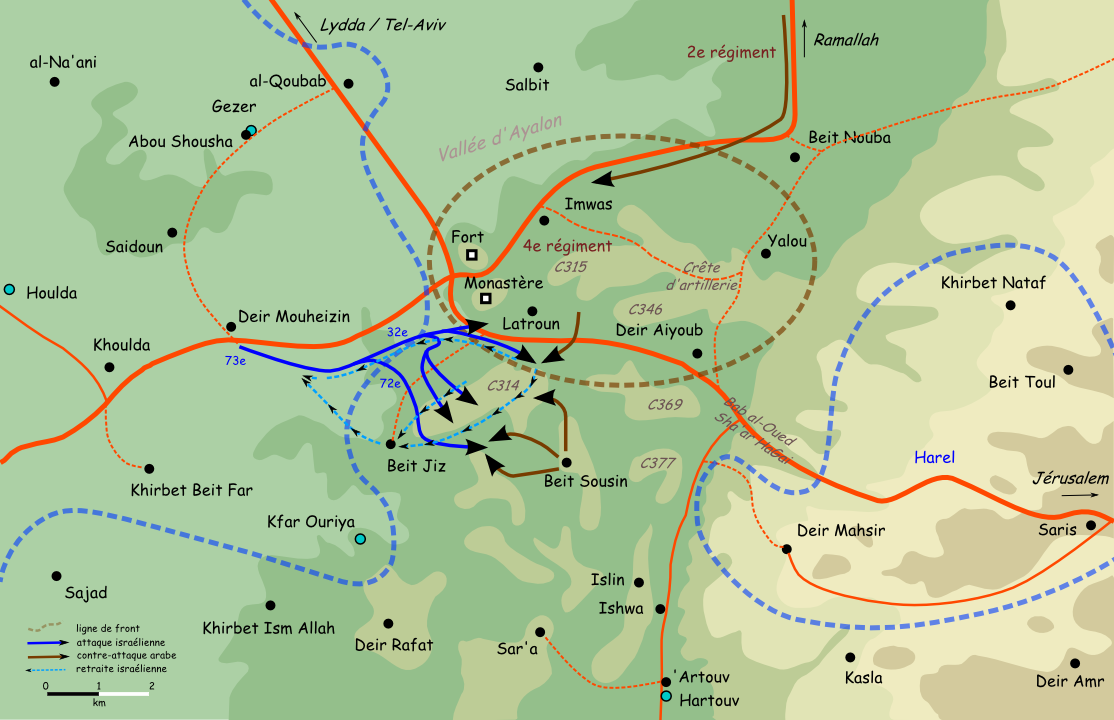

Operation Bin Nun Bet

Shlomor Shamir was once again given the command of the operation. He sent the 7th Brigade and the 52nd Battalion of the Givati Brigade that replaced the 32nd that had been decimated in the previous battle.

The 73rd Battalion was an armored force of light infantry with

flame-thrower

A flamethrower is a ranged incendiary device designed to project a controllable jet of fire. First deployed by the Byzantine Empire in the 7th century AD, flamethrowers saw use in modern times during World War I, and more widely in Worl ...

s and 22 "military cars" made locally.

[ Lapierre & Collins (1971), Events relative to the second battle of Latrun, pp. 774–787.]

The Israelis sent numerous reconnaissance patrols

but they nevertheless had no clear idea of the adversary's forces. They expected to fight 600 men of the Legion and of the Arab Liberation Army, so a force was allocated that was not enough to hold the Latrun front.

Jordanians still had in fact a full brigade and are supported by several hundreds of irregulars. Taking into account the mistakes of the previous attacks, the renewed assault was organised with precision, and the area from where the units had to launch their attack had been cleared on 28 May. In particular the two hamlets of Bayt Jiz and Bayt Susin, where a counter-attacks had been launched by the Arab militants during the first battle, and Hill 369.

The attack was once more foreseen on two axes:

* The 72nd and 52nd Infantry Battalions were to counter-attack on foot from the south up to

Bayt Susin

Bayt Susin ( ar, بَيْت سُوسِين) was a Palestinian Arab village in the Ramle Subdistrict of Mandatory Palestine, located southeast of Ramla. In 1945, it had 210 inhabitants. The village was depopulated during the 1948 war by the Isr ...

and then take

Bab al-Wad

Sha'ar HaGai ( he, שער הגיא) in Hebrew, and Bab al-Wad or Bab al-Wadi in Arabic ( he, באב אל-ואד, ar, باب الواد or ), lit. ''Gate of the Valley'' in both languages, is a point on the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem highway, 23 km ...

and attack respectively Dayr Ayyub and Yalu, then head for Latrun and attack this from the east;

* The 71st Infantry Battalion and 73rd Mechanised Battalion were to assault the police fort, the monastery and the town of Latrun by south-west.

Around midnight, the men of the 72nd and the 52nd passed Bab al-Wad noiselessly and then separated towards their respective targets. One company took Deir Ayyub, which was empty, but then were discovered as they did so by enemies on a nearby hill. They suffered the joint fire of the Legion's artillery and machines guns. Thirteen men were killed and several other injured. The company, composed mainly of immigrants, then retreated to Bab al-Wad. The 52nd Battalion was preparing to take the hill in front of Yalu, but received an order to retreat.

On the other front, the forces divided in two parts. The infantry of the 71st rapidly took the monastery and then fought for the control of the town. On the other side, the Israeli artillery succeeded in neutralizing the fort's weapons. The volunteers crossed the defence fence and their flame-throwers took the defenders by surprise. Nevertheless, the light coming from the fire they created lost their cover and they became easy targets for the mortars of the Jordanians. They were quickly knocked out and destroyed. The sappers succeeded nevertheless to make the door explode, but in the confusion were not followed by the infantrymen. Chaim Laskov, the chief of operations on that front, ordered company D of the 71st Battalion (that had been kept in reserve) to intervene, but one of the soldiers accidentally exploded a landmine, killing three men and injuring several others. They were then attacked by heavy fire from the Jordanian artillery and the men retreated towards the west in panic.

The battle was still not lost for the Israelis although the wake was coming, and Laskov considered that his men could not hold in front of a Legion's counter-attack and he preferred to order the retreat.

It was also time for the Jordanians to regroup, their 4th Regiment was completely out of ammunition.

73rd Battalion suffered 50% losses and the whole of the engaged forces had counted 44 deaths and twice that number injured.

According to the sources, the Legion suffered between 12 and 20 deaths, including the lieutenant commanding the fort.

In contrast, the Jordanians reported 2 just deaths on their side, and 161 of the Israelis.

David Marcus later attributed the responsibility for the defeat to the infantry, stating: "the artillery cover was correct. The armoury were good. The infantry, very bad". Benny Morris considers that the mistake was rather to disperse the forces on several objectives instead of concentrating the full brigade on the main objective: the fort.

"Burma Road"

On 28 May, after they took Bayt Susin, the Israelis controlled a narrow corridor between the coastal plain and Jerusalem. But this corridor was not crossed by a road that could have let trucks supply the city.

A foot patrol of the

Palmach

The Palmach (Hebrew: , acronym for , ''Plugot Maḥatz'', "Strike Companies") was the elite fighting force of the Haganah, the underground army of the Yishuv (Jewish community) during the period of the British Mandate for Palestine. The Palmach ...

discovered some paths that linked several villages in the hills south of the main road controlled by the Arab Legion.

In the night of 29–30 May,

Jeep

Jeep is an American automobile marque, now owned by multi-national corporation Stellantis. Jeep has been part of Chrysler since 1987, when Chrysler acquired the Jeep brand, along with remaining assets, from its previous owner American Motors ...

s sent into the hills confirmed there was a path suitable for vehicles.

[ Benny Morris, ''1948'' (2008), Information relating to the Burma road pp. 230–231.] The decision was then taken to build a road in the zone. This was given the name of "

Burma Road

The Burma Road () was a road linking Burma (now known as Myanmar) with southwest China. Its terminals were Kunming, Yunnan, and Lashio, Burma. It was built while Burma was a British colony to convey supplies to China during the Second S ...

", referring to the supply road between

Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

and

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

built by the British during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

Engineers immediately started to build the road while convoys of jeeps, mules and camels

were organised from Hulda to carry mortars to Jerusalem. Without knowing the goals of these works, the Jordanians realised a game was afoot in the hills. They performed artillery bombings, that would anyway have been rapidly stopped under the orders of the top British officer, and they sent patrols to stop the works, but without success.

Nevertheless, it was mainly food that the inhabitants of Jerusalem needed. Starting 5 June, the Israeli engineers started to fix the road so that it let civil transport trucks pass to supply the city.

150 workers, working in four teams, installed a

pipeline to supply the city with water, because the other pipeline, crossing Latrun, had been cut by the Jordanians.

[ Dominique Lapierre et Larry Collins, ''O Jérusalem'' (1971) pp. 827–828.] In ''O Jerusalem'', Dominique Lapierre and Larry Collins talked about heroic action, when during the night of 6–7 June, in fear of the critical situation of Jerusalem and to improve the morale of the population, 300 inhabitants of Tel Aviv were conscripted to carry on their backs, for the few kilometers not yet ready for the trucks, what would be needed to feed the inhabitants of Jerusalem one more day.

The first phase of these works was achieved for the 10 June truce

and on 19 June a convoy of 140 trucks, each carrying three tons of merchandise as well as numerous weapons and ammunition, reached Jerusalem.

The siege of the city was then definitively over.

This Israeli success was punctuated by an incident that became marked in memory: the death of Aluf

Mickey Marcus, accidentally killed by an Israeli sentry during the night of 10–11 June.

Operation Yoram (8–9 June 1948)

Between 30 May and 8 June the status between the Israeli and Arabic armies became a stand-off. They were used to fighting small, violent battles and taking heavy losses of people and arms, and the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

renewed its call for a truce on 11 June. It was in this context that David Ben-Gurion took the decision to withdraw from Galilee the elite 11th

Yiftach Brigade

The Yiftach Brigade (also known as the Yiftah Brigade, the 11th Brigade in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War) was an Israeli infantry brigade. It included two Palmach battalions (the 1st and 7th), and later also the 2nd, which was transferred from the ...

under the orders of Yigal Allon to launch a third assault against Latrun.

He had at his disposal an artillery support composed of four mortars and four guns

that were part of the heavy weapons recently delivered to Israel by

Operation Balak

Operation Balak was a smuggling operation, during the founding of Israel in 1948, that purchased arms in Europe to avoid various embargoes and boycotts transferring them to the Yishuv. Of particular note was the delivery of 23 Czechoslovakia-made ...

.

This time, the general staff decided on an attack concentrated on the centre of the Legion disposal, with several diversion attacks to the north to disrupt the Jordanians. While a battalion from the Yiftach Brigade was performed some diversions attacks on Salbit, Imwas and Bayt Nuba, a battalion from the Harel brigade was to take Hill 346, between the fourth and second Legion regiments and a battalion from the Yiftach Brigade was then to pass through it, take Hill 315 and Latrun village and the police fort by the East.

[ Benny Morris, ''1948'' (2008), Information relative to Operation Yoram pp. 229–230.] The Israeli operation started with an artillery barrage on the fort, the village of Latrun and the positions around. Hills 315 and 346 occupied with a company from the Legion, were not targeted not to alert the Jordanians.

The men of the Harel brigade made leave on foot from Bab al-Oued but took a wrong way and mistakenly attacked Hill 315. Located by the Jordanian sentries, they launch the attack of the hill. The Legionnaires were outnumbered but counterattacked with violence, going as far as requiring an artillery bombing on their own position. The Israelis suffered some heavy losses. When the Yiftach arrived at the bottom of Hill 346, they are targeted by firearms, grenades and artillery. Thinking that Harel men were there, they called by radio to the headquarters to ceasefire, and laid down arms. They refused, not believing that account of the events and Harel soldiers stayed in place.

Confusion among Jordanians was as important as among Israelis with the attack on Hill 315 and those of diversion. With the incoming morning and unable to evaluate properly the situation, the Israeli HQ gave orders at 5.30 am for the soldiers to retreat to

Bad al-Oued.

The losses were also significant. Indeed, the 400-strong Harel battalion numbered 16 dead and 79 injured, and the Yiftach a handful of dead and injured. The Legion numbered several dozen victims.

The following day, Jordan mounted two counter-attacks. The first was over

Beit Susin. The Legionnaires took several Israeli guard posts but could not keep them more than a few hours. The fighting took lives and some 20 injuries on the Israeli side. The second was at

Kibbutz Gezer

Gezer ( he, גֶּזֶר) is a kibbutz in central Israel. Located in the Shephelah between Modi'in, Ramle and Rehovot, it falls under the jurisdiction of Gezer Regional Council. In it had a population of .

History

The kibbutz was established in ...

from where the diversion attacks had been launched. A force the strength of a battalion, made up of Legionnaires and irregulars and supported by a dozen armoured vehicles, attacked the kibbutz in the morning. It was defended by 68 soldiers of the Haganah (including 13 women).

After the four-hour battle, the kibbutz fell. A dozen of the defenders escaped. Most others surrendered and one or two were executed. The Legionnaires protected the prisoners from irregulars and the next day freed the women. The toll was 39 dead on the Israeli side and 2 on the Legionnaires' side. The kibbutz was looted by the irregulars and the Legionnaires evacuated the area after the fights. In the evening the Yiftach Brigade retook the kibbutz.

Attacks organised during Operation Danny

After the month of truce, during which

Tsahal

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the State of Israel. It consists of three service branch ...

increased forces and re-equipped, the weakest point of the Israeli dispositions were on the central front and the corridor to Jerusalem. The High Command decided to launch "

Operation Larlar" with the objective of taking Lydda, Ramle,

Latrun

Latrun ( he, לטרון, ''Latrun''; ar, اللطرون, ''al-Latrun'') is a strategic hilltop in the Latrun salient in the Ayalon Valley, and a depopulated Palestinian village. It overlooks the road between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, 25 kilometers ...

and

Ramallah

Ramallah ( , ; ar, رام الله, , God's Height) is a Palestinian city in the central West Bank that serves as the ''de facto'' administrative capital of the State of Palestine. It is situated on the Judaean Mountains, north of Jerus ...

and relieving the threat on Tel Aviv on a side and West Jerusalem on the other.

[ Benny Morris, ''1948'' (2008) p. 286.]

To achieve this objective

Yigal Allon

Yigal Allon ( he, יגאל אלון; 10 October 1918 – 29 February 1980) was an Israeli politician, commander of the Palmach, and general in the Israel Defense Forces, IDF. He served as one of the leaders of Ahdut HaAvoda party and the Labor P ...

in entrusted 5 brigades: the Harel and Yiftach (now totalling five battalions), the

8th armoury brigade (newly constituted as the 82nd and 89th battalions), several infantry battalions from the

Kiryati and Alexandroni brigades, and 30 pieces of artillery.

The 7th brigade was sent to the northern front. In a first phase, between 9 and 13 July, the Israelis took Lydda and Ramle and reasserted the area around Latrun by taking

Salbit

Salbit ( ar, سلبيت, also spelled Selbît) was a Palestinian Arab village located southeast of al-Ramla. Salbit was depopulated during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War after a military assault by Israeli forces. The Israeli locality of Shaalvim w ...

, but the forces are exhausted and the High Command renounced to the objective of taking

Ramallah

Ramallah ( , ; ar, رام الله, , God's Height) is a Palestinian city in the central West Bank that serves as the ''de facto'' administrative capital of the State of Palestine. It is situated on the Judaean Mountains, north of Jerus ...

.

Two attacks were launched against Latrun.

On the east of the Jordanian positions (16 July)

On the night of 15–16 July, several companies of the Harel brigade laid on an assault against Latrun by the east, around the "artillery ridge" and the villages of

Yalo

Yalo ( ar, يالو, also transliterated Yalu) was a Palestinian Arab village located 13 kilometres southeast of Ramla. Identified by Edward Robinson as the ancient Canaanite and Israelite city of Aijalon.Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, pp8081 ...

and

Bayt Nuba

Bayt Nuba ( ar, بيت نوبا) was a Palestinian Arab village, located halfway between Jerusalem and al-Ramla. Historically identified with the biblical city of Nob mentioned in the Book of Samuel, that association has been eschewed in modern ti ...

. They carried on to the hills by way of the villages of

Bayt Thul

Bayt Thul was a Palestinian village in the Jerusalem Subdistrict. It was depopulated during the 1947–1948 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine on April 1, 1948, under Operation Nachshon. It was located 15.5 km west of Jerusalem.

History Ott ...

and

Nitaf

Nitaf ( ar, نطاف, ''Natâf'') was a small Palestinian Arab village in the Jerusalem Subdistrict. It was depopulated during the 1947–1948 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine on April 15, 1948, during the second stage of Operation Dani. It was ...

transporting their armoury using pack mules. After several hours of fighting and counter-attacks by armoured vehicles of the Arab Legion, they were finally pushed back but could keep control of several hills.

[ Benny Morris, ''1948'' (2008) p. 293.] In total, the Israelis lost 23 dead and numerous injured.

Frontal assault against the police fort (18 July)

One hour before the truce, the High Command decided to try a frontal assault against the police fort. Intelligence indicated that, in effect, it was "more likely than not" that the Legion's forces in the sector were "substantial".

[Description of the assault against the police fort](_blank)

, on the website of the Palmach (retrieved on 2 May 2008). In the morning, reconnaissance patrols had sized up the sector, but could not confirm or deny the information that had been gathered by the intelligence. At 6 pm two

Cromwell tank

The Cromwell tank, officially Tank, Cruiser, Mk VIII, Cromwell (A27M), was one of the series of cruiser tanks fielded by Britain in the Second World War. Named after the English Civil War-era military leader Oliver Cromwell, the Cromwell was t ...

s driven by British deserters, seconded by a mechanised battalion of the Yiftach and supported by artillery launched the attack of the police fort.

When the Israeli forces arrived from the fort, they were shelled by Jordanian artillery. Around 6:15 pm. one of the tanks was hit by a shell (or sustained a mechanical damage

) and had to retreat to al-Qubab for repairs. The remaining forces waited for its return and the attack resumed around 7:30 pm, but was abandoned around 8 pm.

The Israelis counted between 8

and 12 victims. At the same time, elements of the Harel brigade took about 10 villages to the south of Latrun to enlarge and secure the area of the Burma road. The majority of inhabitants had fled the fights in April but those who remained were systematically expelled.

The final assault

After the ten-day campaign, the Israelis were military superior to their enemies and the Cabinet subsequently considered where and when to attack next. Three options were offered: attacking the Arabic enclave in

Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Gali ...

held by the

Arab Liberation Army

The Arab Liberation Army (ALA; ar, جيش الإنقاذ العربي ''Jaysh al-Inqadh al-Arabi''), also translated as Arab Salvation Army, was an army of volunteers from Arab countries led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji. It fought on the Arab side in the ...

; moving eastward as far as possible in

Samaria

Samaria (; he, שֹׁמְרוֹן, translit=Šōmrōn, ar, السامرة, translit=as-Sāmirah) is the historic and biblical name used for the central region of Palestine, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The first ...

n and

Judea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous Latin, and the modern-day name of the mountainous so ...

n areas, taken by the

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

is and

Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

ians; or attacking southern

Negev

The Negev or Negeb (; he, הַנֶּגֶב, hanNegév; ar, ٱلنَّقَب, an-Naqab) is a desert and semidesert region of southern Israel. The region's largest city and administrative capital is Beersheba (pop. ), in the north. At its sout ...

taken by the Egyptians.

[Benny Morris (2008), pp. 315–316.]

On 24 September, an incursion made by the Palestinian irregulars in the Latrun sector (killing 23 Israeli soldiers) precipitated the debate. On 26 September, David Ben-Gurion put his argument to the Cabinet to attack Latrun again and conquer the whole or a large part of West Bank.

[Benny Morris (2008), pp. 317.]

The motion was rejected by a vote of seven to five after discussions. According to Benny Morris, the arguments that were advanced not to launch the attack were: the negative international repercussions for Israel already accentuated by the recent assassination of

Count Bernadotte; the consequences of an attack on an agreement with Abdallah; the fact that defeating the Arab Legion could provoke a British military intervention because of Britain and Jordan's common defense pact and lastly because conquering this area would add hundreds of thousands of Arab citizens to Israel.

[Benny Morris (2008), pp. 317–318.]

Ben-Gurion judged the decision ("A cause for lamentation for generations") in considering that Israel could never renounce its claim in Judea, Samaria and over

Old Jerusalem.

Aftermath

At the operational level, the five assaults on Latrun resulted in Israeli defeats and Jordanian victories: the Jordanians repelled all assaults and kept control of the road between the coastal plain and Jerusalem, with Israel losing 168 killed and many more injured.

[Taking into account the references given in the article, the sum of the Israeli losses for the five assaults gives numbers between 164 and 171 Israeli victims, without taking into account the 39 victims for the attack against Gezer, the 8 of the Jordanian counter attack against Bayt Susin and the 45 of Qirbet Quriqur.] Strategically, the outcome was more nuanced:

*The opening of the

Burma Road

The Burma Road () was a road linking Burma (now known as Myanmar) with southwest China. Its terminals were Kunming, Yunnan, and Lashio, Burma. It was built while Burma was a British colony to convey supplies to China during the Second S ...

enabled the Israelis to bypass Latrun and supply the 100,000 Jewish inhabitants of West Jerusalem with food, arms, munitions, and equipment and reinforce their military position there;

*If the control of West Jerusalem by Israel held some of the Arab forces, the Arab Legion control of Latrun, from Tel Aviv, was a thorn in the side of Israeli forces;

*Latrun was a pivot point of the Legion's deployment;

Glubb Pacha massed a third of his troops there; its defeat would have caused the fall of East Jerusalem and probably all of the West Bank.

[ Benny Morris, ''The road to Jerusalem'' (2002) p. 241.]

At the discussions of the Israeli-Jordano Armistice at

Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

, the Israelis requested unsuccessfully the removal of the legion from Latrun. It subsequently remained under Jordanian control until the

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 ...

.

Historiography

Israeli historiography and collective memory

According to Israeli historian

Anita Shapira

Anita Shapira ( he, אניטה שפירא, born 1940) is an Israeli historian. She is the founder of the Yitzhak Rabin Center, professor emerita of Jewish history at Tel Aviv University, and former head of the Weizmann Institute for the Study of ...

, there is a gap, at times quite wide, between the 'facts established by historical research' and the image of the battle as retained in

collective memory

Collective memory refers to the shared pool of memories, knowledge and information of a social group that is significantly associated with the group's identity. The English phrase "collective memory" and the equivalent French phrase "la mémoire ...

. This is certainly the case for the battle of Latrun, which has become, in Israel, a

founding myth

An origin myth is a myth that describes the origin of some feature of the natural or social world. One type of origin myth is the creation or cosmogonic myth, a story that describes the creation of the world. However, many cultures have sto ...

.

The clear-sightedness of the Commander-in-Chief

The first version of the battle of Latrun was contrived by

David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; he, דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first prime minister of Israel. Adopting the nam ...

and his entourage.

Initially, the governing power within Israel remained silent. However, on May 27, the Israeli daily

Maariv

''Maariv'' or ''Maʿariv'' (, ), also known as ''Arvit'' (, ), is a Jewish prayer service held in the evening or night. It consists primarily of the evening ''Shema'' and '' Amidah''.

The service will often begin with two verses from Psalms ...

printed a sceptical coverage of Arab accounts, which spoke of a great victory by the Arab Legion, involving some 800 Israeli dead. In response, the Israeli press stressed that the aim of the operation was not to take Latrun, but to strike the Legion and, on June 1, it published casualty figures of 250 deaths for the Arab side and 10 deaths, with 20 badly wounded, and another 20 lightly wounded on the Israeli side.

[ Anita Shapira, ''L'imaginaire d'Israël : histoire d'une culture politique'' (2005), pp. 97–102.]

From 14 June, the press shifted its focus to the 'opening of the Burma route' and, in the context of a conflict between the military's senior command and Ben-Gurion,

Yigael Yadin

Yigael Yadin ( he, יִגָּאֵל יָדִין ) (20 March 1917 – 28 June 1984) was an Israeli archeologist, soldier and politician. He was the second Chief of Staff of the Israel Defense Forces and Deputy Prime Minister from 1977 to 1981.

B ...

called the operation a 'great catastrophe' while the latter replied that, in his view, it had been "a great, although costly, victory".

The "official version" entered in the

historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians h ...

in 1955 following the work of lieutenant colonel

Israel Beer

Israel Beer (sometimes spelled Yisrael Bar, 9 October 1912 – 1 May 1966) was an Austrian-born Israeli citizen convicted of espionage. On March 31, 1961, Beer, a senior employee in the Israeli Ministry of Defense, was arrested under suspicio ...

, whereas adviser and support of Yadin at the time of the events, who published 'The battles of Latrun'. This study, considered by the historian

Anita Shapira

Anita Shapira ( he, אניטה שפירא, born 1940) is an Israeli historian. She is the founder of the Yitzhak Rabin Center, professor emerita of Jewish history at Tel Aviv University, and former head of the Weizmann Institute for the Study of ...

as "the most clever ever written on the topic", puts the battles in their military and political context. It concludes that given the strategic and symbolic importance of Jerusalem, "the three tactical defeats that occurred at Latrun (...) permitted the supply

f the cityand were a diversal manoeuvre (...)

ndare the consequence of the strategic clear-sightedness of the Commander-in-Chief, able to identify the key points and subordinate to his general sight the tactical considerations, limited, of the military command.

Ber put the responsibility of the tactical defeats on the failures of the intelligence services and on the "absence de commandement séparé sur les différents fronts." He also points out the badly trained immigrants, the defective equipment, and the difficulty for a new army to succeed a first operation targeting to capture a defended area that was organised by advance. He gives the first estimates for the losses: 50 deaths in the 32nd battalion of the ''Alexandroni'' brigade and the 25 deaths in the 72nd battalion of the 7th brigade (composed mainly of immigrants).

Finally, Ber

founded the myth and pictured the events of Latrun as "an heroic saga, as the ones that occurs at the birth of a nation or at the historical breakthrough of movements of national liberation".

Criminal negligence

bout the First Battle of Latrun:

bout the First Battle of Latrun:"the Jordanians broke the attack by noon, with fewer than two thousand Israeli deaths."

Whereas many events in the war were more bloody for the Israelis, like the massacre at

Kfar Etzion with 150 deaths or the one of the Mount Scopus with 78, the Battle of Latrun is the event of the war to provoke most rumours, narratives and controversies in Israel.

[ Anita Shapira, ''L'imaginaire d'Israël : histoire d'une culture politique'' (2005) pp. 103–112.] The main reason is that Latrun had still been the mainstay for the road to Jerusalem until the

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 ...

, keeping the Israelis at the margins and having to go round and maintain the town, but struggling to bypass it, which played each day on their minds. According to

Anita Shapira

Anita Shapira ( he, אניטה שפירא, born 1940) is an Israeli historian. She is the founder of the Yitzhak Rabin Center, professor emerita of Jewish history at Tel Aviv University, and former head of the Weizmann Institute for the Study of ...

, the primary reason was nothing but people's grievous memories, of David Ben-Gurion and the veterans of the British Armies on one side and former

Palmah and

Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the I ...

soldiers on the other.

In this sphere of influence during the 1970s and in the controversies that continued until the 1980s, the "Strategic Necessity" was said, if it were not done, it would be "

Criminal negligence

In criminal law, criminal negligence is a surrogate state of mind required to constitute a ''conventional'' (as opposed to ''strictly liable'') offense. It is not, strictly speaking, a (Law Latin for "guilty mind") because it refers to an o ...

", with a heavy toll on bring in immigrants to the battle, and forging a new

founding myth

An origin myth is a myth that describes the origin of some feature of the natural or social world. One type of origin myth is the creation or cosmogonic myth, a story that describes the creation of the world. However, many cultures have sto ...

.

On one side, the opponents of Ben-Gurion attacked his "

moral authority Moral authority is authority premised on principles, or fundamental truths, which are independent of written, or positive, laws. As such, moral authority necessitates the existence of and adherence to truth. Because truth does not change, the princi ...

". They said that the intrusion into Latrun by the "scum of the earth" immigrants who died had changed the situation for the worse. And the number of victims, and the proportion of immigrants, inflated in the narratives: from "several hundreds of dead" to "500 to 700 dead and even "1,000 to 2,000 dead". The proportion of immigrants making up this total of victims was up to 75%. His opponents accused Ben-Gurion of wanting to take out the myth of the "invincible

Arab Legion

The Arab Legion () was the police force, then regular army of the Emirate of Transjordan, a British protectorate, in the early part of the 20th century, and then of independent Jordan, with a final Arabization of its command taking place in 1 ...

" and to justify the abandonment of the city of David to Abdallah.

(

Anita Shapira

Anita Shapira ( he, אניטה שפירא, born 1940) is an Israeli historian. She is the founder of the Yitzhak Rabin Center, professor emerita of Jewish history at Tel Aviv University, and former head of the Weizmann Institute for the Study of ...

considers this story to be at the origin of the theory of

Avi Shlaim

Avraham "Avi" Shlaim (born 31 October 1945) is an Israeli- British historian, Emeritus Professor of International Relations at the University of Oxford and fellow of the British Academy. He is one of Israel's New Historians, a group of Israe ...

who brought forth what she considers as the myth of the collusion between Ben-Gurion and Abdallah.

) On the other side, those supporting Ben-Gurion put everything to advance the case of the "historic sacrifice" by the immigrants, laying the failure to their poor training.

Many contemporary books about the 1948 War were published at this time:

John and David Kimche, ''The two sides of the hill'' (1960) (the more reliable);

Dominique Lapierre

Dominique Lapierre (30 July 1931 – 2 December 2022) was a French author.

Life

Dominique Lapierre was born in Châtelaillon-Plage, Charente-Maritime, France. At the age of thirteen, he travelled to the U.S. with his father who was a diploma ...

and

Larry Collins,

''O Jerusalem'' (1972) (the best known internationally) and

Dan Kurzman, ''Genesis, 1948'' (1970) (the only one that got reviews in the Israeli press).

With this political writing, historical research on Latrun tends to concentrate on the 1980s with the work of Arié Itzhaki, "Latrun" (in 2 volumes). It gives the exact number of victims, but contrary to

Israel Beer

Israel Beer (sometimes spelled Yisrael Bar, 9 October 1912 – 1 May 1966) was an Austrian-born Israeli citizen convicted of espionage. On March 31, 1961, Beer, a senior employee in the Israeli Ministry of Defense, was arrested under suspicio ...

(meanwhile caught as spying for

USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nati ...

), it depicts the battle as "The hardest in the history of

Tsahal

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the State of Israel. It consists of three service branch ...

", and ''it puts the responsibility of the defeat on Ben-Gurion, who panicked about Jerusalem, and tactical errors on the brigade commanders and not on the immigrants who received'' (from his point of view

[ Anita Shapira, ''L'imaginaire d'Israël : histoire d'une culture politique'' (2005), underlines that Itzhaki thought wrongly that the immigrants had got training before in Cyprus.]) a sufficient training.

The drama of alienation

In the first years after its foundation, Israel met a problem with

social integration

Social integration is the process during which newcomers or minorities are incorporated into the social structure of the host society.

Social integration, together with economic integration and identity integration, are three main dimensions ...

of new immigrants who had arrived after the war, who had received much trauma from their exodus from Arab lands or from the death camps, and had suffered six years of war. Their integration was difficult with

Sabra Israelis, born in the Palestinian Mandate, and taking the essential jobs and around who Israel had built an image of "Sabras, strong and courageous, fearless heroes, disdaining feebleness and trouble". The phenomenon rose up again with the Israeli victory of the

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 ...

.

[ Anita Shapira, ''L'imaginaire d'Israël : histoire d'une culture politique'' (2005) pp. 113–121.]

All the while, these uncertainties and the reparations from the

Yom Kippur War