Battle of Tannenberg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Tannenberg, also known as the Second Battle of Tannenberg, was fought between

The Battle of Tannenberg, also known as the Second Battle of Tannenberg, was fought between

By the next morning, 21 August, Eighth Army staff realized that because Samsonov's II Army was closer to the Vistula crossings than they were, they must first relocate most of their forces to join with XX Corps to block Samsonov before they could withdraw further. Now Moltke was told that they would only retreat a short distance. François protested directly to the Kaiser about his panicking superiors. That evening Prittwitz reported that the German 1st Cavalry Division had disappeared, only to later disclose that they had repulsed the Russian cavalry, capturing several hundred. By this point, Moltke had already decided to replace both Prittwitz and his chief of staff, Alfred von Waldersee. On the morning of 22 August their replacements, Col. Gen.

By the next morning, 21 August, Eighth Army staff realized that because Samsonov's II Army was closer to the Vistula crossings than they were, they must first relocate most of their forces to join with XX Corps to block Samsonov before they could withdraw further. Now Moltke was told that they would only retreat a short distance. François protested directly to the Kaiser about his panicking superiors. That evening Prittwitz reported that the German 1st Cavalry Division had disappeared, only to later disclose that they had repulsed the Russian cavalry, capturing several hundred. By this point, Moltke had already decided to replace both Prittwitz and his chief of staff, Alfred von Waldersee. On the morning of 22 August their replacements, Col. Gen.

On 24 August Hindenburg, Ludendorff and Hoffmann motored along the German lines to meet Scholtz and his principal subordinates, sharing the roads with panic-stricken refugees; in the background were columns of smoke from burning villages ignited by artillery shells. They could keep control of their army because most of the local telephone operators remained at their switchboards, carefully tracking the motorcade. Along the way they drove through the village of Tannenberg, which reminded the two younger men of the defeat of the Teutonic Knights there by the Poles and Lithuanians in 1410; Hindenburg had been thinking about that battle since the evening before when he strolled near the ruins of the castle of the Teutonic Order. (In 1910 Slavs had commemorated their triumph on the old battlefield.)

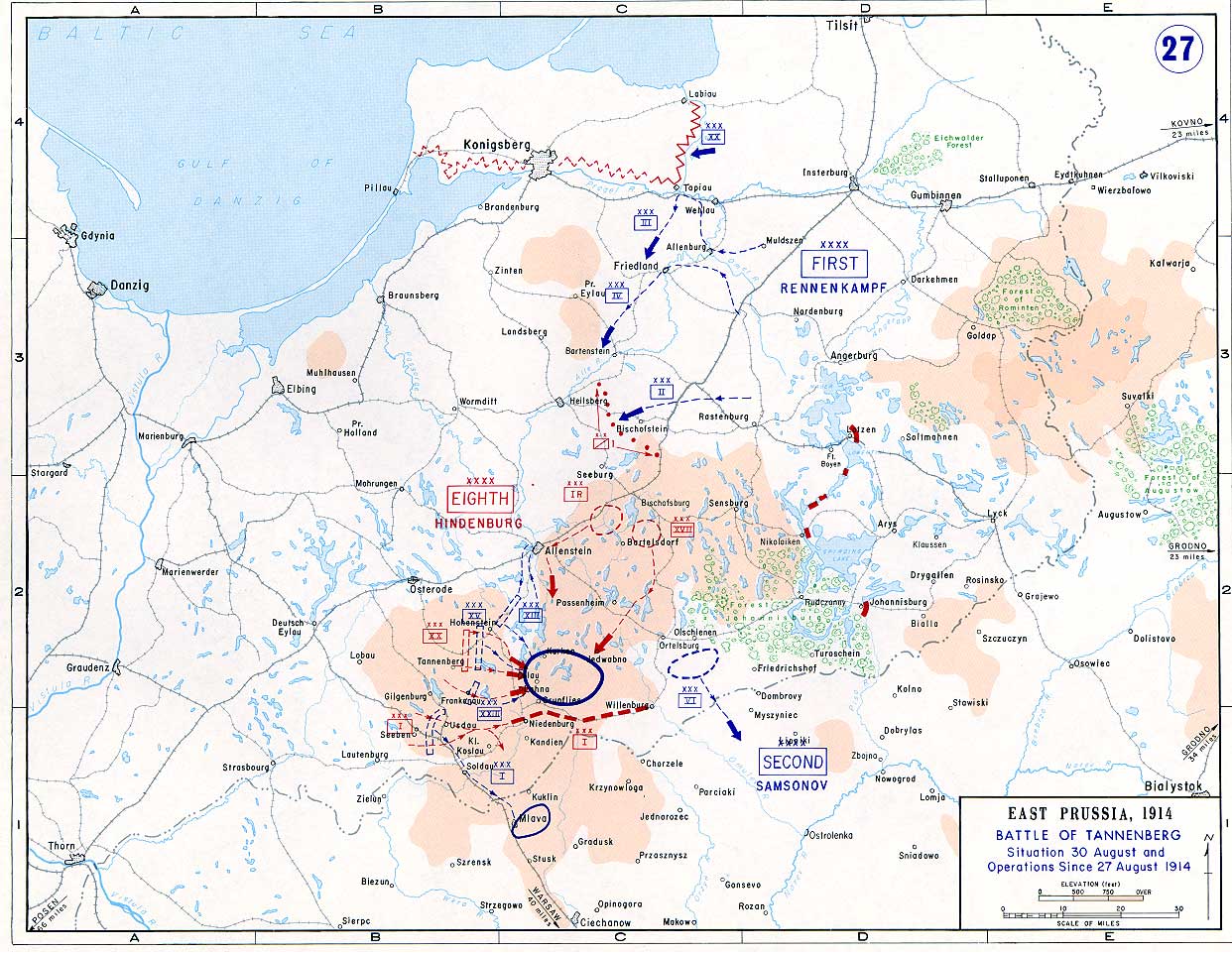

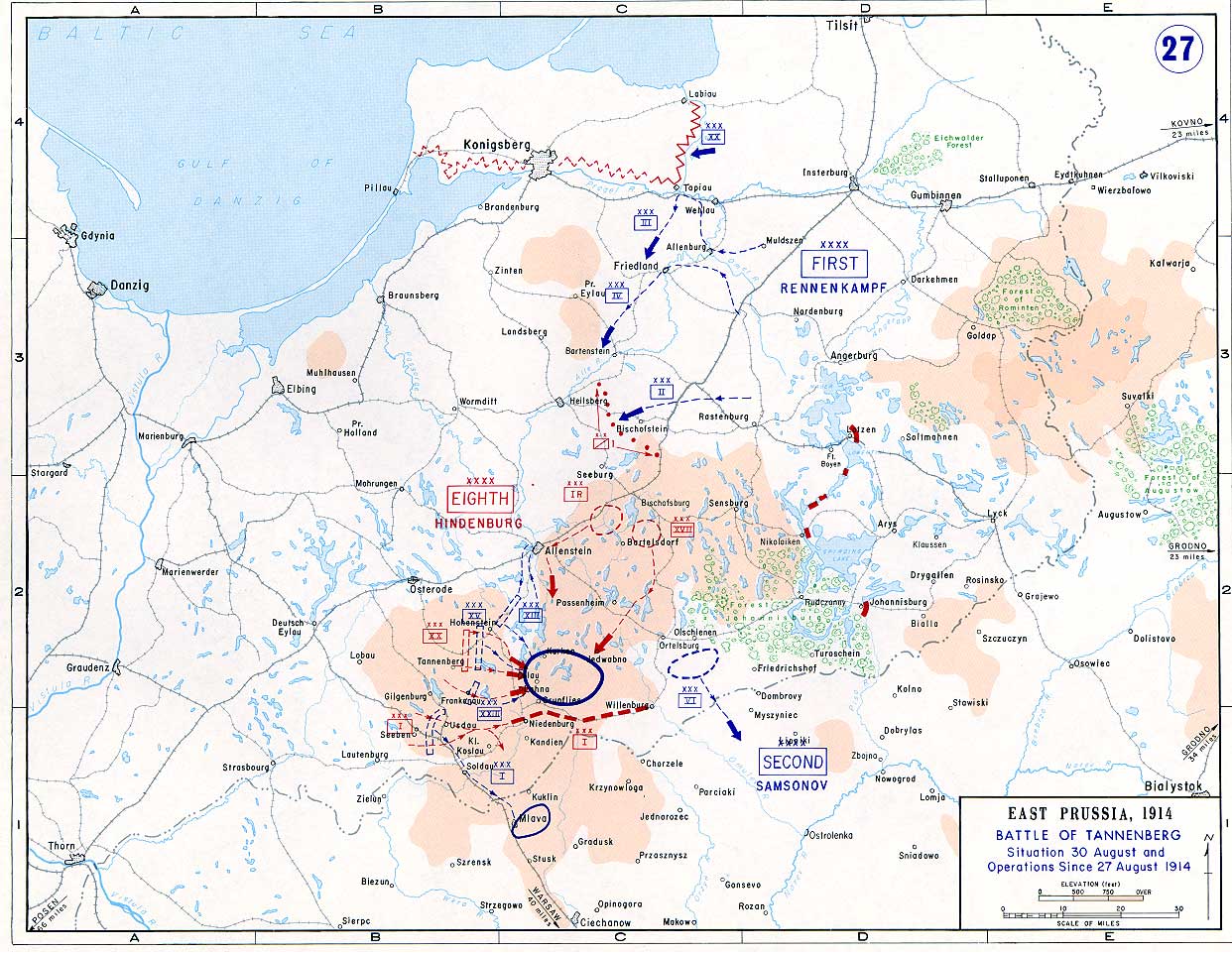

Aided by Russian radio intercepts, a captured map of Russian positions, and information from fleeing German civilians of Rennenkampf's slow progress, Hindenburg and Ludendorff planned the encirclement of the Russian Second Army. I Corps and XX Corps would attack from Gilgenburg towards Neidenburg, while XVII Corps and I Reserve Corps attacked the Russian right flank. They met with Scholtz and his XX Corps staff on 24 August, and François on 25 August, where he was ordered to attack towards Usdau on 26 August. François stated only part of his corps and artillery had arrived. Ludendorf insisted the attack must go forward as planned, since more trains were expected beforehand. François replied, "If it is so ordered, of course an attack will be made, and the troops will obviously have to fight with bayonets."

On the way back to headquarters Hoffmann received new radio intercepts. Rennenkampf's most recent orders from Zhilinskiy were to continue due west, not turn south-westward towards Samsonov, who was instructed to continue his own drive northwest further away from Rennenkampf. Based on this information Scholtz formed a new defensive flank along the Drewenz River, while his main line strengthened their defenses. Back at headquarters Hindenburg told the staff, "Gentlemen. Our preparations are so well in hand that we can sleep soundly tonight."

Samsonov was concerned by the German resistance with their earlier advance, and aerial reconnaissance spotted the arrival of the German I Corps. However, Samsonov was ordered by Zhilinski to attack northwest with Martos' XV Corps, and Klyuev's XII Corps, while I Corps protected the left flank, and VI Corps was positioned on the right at

On 24 August Hindenburg, Ludendorff and Hoffmann motored along the German lines to meet Scholtz and his principal subordinates, sharing the roads with panic-stricken refugees; in the background were columns of smoke from burning villages ignited by artillery shells. They could keep control of their army because most of the local telephone operators remained at their switchboards, carefully tracking the motorcade. Along the way they drove through the village of Tannenberg, which reminded the two younger men of the defeat of the Teutonic Knights there by the Poles and Lithuanians in 1410; Hindenburg had been thinking about that battle since the evening before when he strolled near the ruins of the castle of the Teutonic Order. (In 1910 Slavs had commemorated their triumph on the old battlefield.)

Aided by Russian radio intercepts, a captured map of Russian positions, and information from fleeing German civilians of Rennenkampf's slow progress, Hindenburg and Ludendorff planned the encirclement of the Russian Second Army. I Corps and XX Corps would attack from Gilgenburg towards Neidenburg, while XVII Corps and I Reserve Corps attacked the Russian right flank. They met with Scholtz and his XX Corps staff on 24 August, and François on 25 August, where he was ordered to attack towards Usdau on 26 August. François stated only part of his corps and artillery had arrived. Ludendorf insisted the attack must go forward as planned, since more trains were expected beforehand. François replied, "If it is so ordered, of course an attack will be made, and the troops will obviously have to fight with bayonets."

On the way back to headquarters Hoffmann received new radio intercepts. Rennenkampf's most recent orders from Zhilinskiy were to continue due west, not turn south-westward towards Samsonov, who was instructed to continue his own drive northwest further away from Rennenkampf. Based on this information Scholtz formed a new defensive flank along the Drewenz River, while his main line strengthened their defenses. Back at headquarters Hindenburg told the staff, "Gentlemen. Our preparations are so well in hand that we can sleep soundly tonight."

Samsonov was concerned by the German resistance with their earlier advance, and aerial reconnaissance spotted the arrival of the German I Corps. However, Samsonov was ordered by Zhilinski to attack northwest with Martos' XV Corps, and Klyuev's XII Corps, while I Corps protected the left flank, and VI Corps was positioned on the right at

Zhilinskiy was visited by the commander of the Russian Army, the Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich of Russia, who ordered him to support Samsonov.

Von François commenced his attack early on the 25th, with his 1st Infantry Division advancing towards Seeben, his 2nd Infantry division on its southern flank, and the rest of his corps arriving by train during the day. He captured Seeben by mid-afternoon, but saved an advance on Usdau for the next day. North of von François, Scholtz's 37th and 41st Infantry Divisions faced the Russian 2nd Infantry Division, which fell back with heavy losses. On the left flank of Scholtz's XX Corps, Curt von Morgen's 3rd Reserve Division was ordered to advance onto Hohenstein, but held back out of concern that the Russian XV and XII Corps would threaten his left flank. Klyuev's Russian XIII Corps was ordered to advance onto

Zhilinskiy was visited by the commander of the Russian Army, the Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich of Russia, who ordered him to support Samsonov.

Von François commenced his attack early on the 25th, with his 1st Infantry Division advancing towards Seeben, his 2nd Infantry division on its southern flank, and the rest of his corps arriving by train during the day. He captured Seeben by mid-afternoon, but saved an advance on Usdau for the next day. North of von François, Scholtz's 37th and 41st Infantry Divisions faced the Russian 2nd Infantry Division, which fell back with heavy losses. On the left flank of Scholtz's XX Corps, Curt von Morgen's 3rd Reserve Division was ordered to advance onto Hohenstein, but held back out of concern that the Russian XV and XII Corps would threaten his left flank. Klyuev's Russian XIII Corps was ordered to advance onto

That evening the Eighth Army's staff was on edge. Little had been achieved during the day, when they had intended to spring the trap. XX Corps had done well on another torrid day, but now was exhausted. On their far left they knew that XVII Corps and I Reserve Corps were coming into action, but headquarters had learned little about their progress. In fact, XVII Corps had defeated the Russian VI Corps, which fled back along the roads. XVII Corps had endured long marches in sweltering weather, but some men still had the energy to pursue on bicycles requisitioned from civilians. Hoffmann, who had been an observer with the Japanese in Manchuria, tried to ease their nerves by telling how Samsonov and Rennenkampf had quarreled during that war, so they would do nothing to help one another. It was a good story that Hoffmann treasured and retold frequently. In Hindenburg's words "It was now apparent that danger was threatening from the side of Rennenkampf. It was reported that one of his corps was on the march through Angerburg. It is surprising that misgivings filled many a heart, that firm resolution began to yield to vacillation, and that doubts crept in where a clear vision had hitherto prevailed? We overcame the inward crisis, adhered to our original intention, and turned in full strength to effect its realization by attack." The German right flank would advance to Neidenburg, while von Below's I Reserve Corps advanced to Allenstein, and Mackensen's XVII Corps chased Blagoveschensky's retreating VI Corps.

Von François was ready to attack the Russian left decisively on 27 August, hitting I Russian Corps. His artillery barrage was overwhelming, and soon he had taken the key town of Usdau. In the center the Russians continued to strongly attack the German XX Corps and to move northwest from Allenstein. The German XVII Corps and I Reserve Corps pushed the Russian right wing they had bloodied the day before further back. Gen. Basil Gourko, commanding the Russian First Army Cavalry Division (and from 1916 to 1917 chief of the general staff), was told later that Samsonov did not know what was happening on his flanks because he was observing the action from a rise in the ground a distance from his wireless set and reports were not relayed to him.

On the morning of 28 August the German commanders were motoring along the front when they were shown a report from an aerial observer that Rennenkampf's army was moving towards their rear. Ludendorff announced that the attack on the Second Army must be broken off. Hindenburg led him behind a nearby hedge; when they emerged Hindenburg calmly said that operations would continue as planned. Later radio intercepts confirmed Rennenkampf was still slowly advancing on Königsberg. Von François' I Corps resumed his assault on the Russian I Corps, taking Soldau by late morning, and then advancing onto Neidenburg, as the Russian I Corps became an ineffective force in the battle. Scholtz's XX Corps, to the north, also advanced. Though his 41st Infantry Division was badly mauled by Martos' Russian XV Corps, it held its ground, while the German 37th Infantry Division reached Hohenstein by the end of the day. The German 3rd Reserve Division was also able to advance on the Russian XV Corps, forcing Samsonov to order a retreat to Neidenburg. Von Below's German I Reserve Corps engaged Klyuev's Russian XIII Corps west of Allenstein, and became isolated. Klyuev received orders from Samsonov to retreat towards Kurken. Mackensen's German XVII Corps continued pursuing the retreating Russians. One half of the German encirclement was complete by the end of the day, as Ludendorff wrote, "The enemy front seemed to be breaking up... We did not have a clear picture of the situation with individual units. But there was no doubt that the battle was won."

On 29 August, von François' cavalry regiment reached Willenberg by evening, while his 1st Infantry Division occupied the road between Neidenburg and Willenberg. Von François' I Corps patrols linked up with Mackensen's German XVII Corps, who had advanced to Jedwabno, completing the encirclement. On 29 August the troops from the Russian Second Army's center who were retreating south ran into a German defensive line. Those Russians who tried to break through by dashing across open fields heavy with crops were mowed down. They were in a cauldron centered at Frogenau, west of Tannenberg, and throughout the day they were relentlessly pounded by artillery. Many surrendered — long columns of prisoners jammed the roads away from the battleground. Hindenburg and Ludendorff watched from a hilltop, with only a single field telephone line; thereafter they stayed closer to the telephone network. Hindenburg met one captured Russian corps commander that day, another on the day following. On 30 August the Russians remaining outside of the cauldron tried unsuccessfully to break open the snare. Rather than report the loss of his army to Tsar Nicholas II, Samsonov disappeared into the woods that night and committed suicide. His body was found in the following year and returned to Russia by the Red Cross.

On 31 August Hindenburg formally reported to the Kaiser that three Russian army corps (XIII, XV and XXIII) had been destroyed. The two corps (I and VI) that had not been caught in the cauldron had been severely bloodied and were retreating back to Poland. He requested that the battle be named Tannenberg (an imaginative touch that both Ludendorff and Hoffmann claimed as their own).

That evening the Eighth Army's staff was on edge. Little had been achieved during the day, when they had intended to spring the trap. XX Corps had done well on another torrid day, but now was exhausted. On their far left they knew that XVII Corps and I Reserve Corps were coming into action, but headquarters had learned little about their progress. In fact, XVII Corps had defeated the Russian VI Corps, which fled back along the roads. XVII Corps had endured long marches in sweltering weather, but some men still had the energy to pursue on bicycles requisitioned from civilians. Hoffmann, who had been an observer with the Japanese in Manchuria, tried to ease their nerves by telling how Samsonov and Rennenkampf had quarreled during that war, so they would do nothing to help one another. It was a good story that Hoffmann treasured and retold frequently. In Hindenburg's words "It was now apparent that danger was threatening from the side of Rennenkampf. It was reported that one of his corps was on the march through Angerburg. It is surprising that misgivings filled many a heart, that firm resolution began to yield to vacillation, and that doubts crept in where a clear vision had hitherto prevailed? We overcame the inward crisis, adhered to our original intention, and turned in full strength to effect its realization by attack." The German right flank would advance to Neidenburg, while von Below's I Reserve Corps advanced to Allenstein, and Mackensen's XVII Corps chased Blagoveschensky's retreating VI Corps.

Von François was ready to attack the Russian left decisively on 27 August, hitting I Russian Corps. His artillery barrage was overwhelming, and soon he had taken the key town of Usdau. In the center the Russians continued to strongly attack the German XX Corps and to move northwest from Allenstein. The German XVII Corps and I Reserve Corps pushed the Russian right wing they had bloodied the day before further back. Gen. Basil Gourko, commanding the Russian First Army Cavalry Division (and from 1916 to 1917 chief of the general staff), was told later that Samsonov did not know what was happening on his flanks because he was observing the action from a rise in the ground a distance from his wireless set and reports were not relayed to him.

On the morning of 28 August the German commanders were motoring along the front when they were shown a report from an aerial observer that Rennenkampf's army was moving towards their rear. Ludendorff announced that the attack on the Second Army must be broken off. Hindenburg led him behind a nearby hedge; when they emerged Hindenburg calmly said that operations would continue as planned. Later radio intercepts confirmed Rennenkampf was still slowly advancing on Königsberg. Von François' I Corps resumed his assault on the Russian I Corps, taking Soldau by late morning, and then advancing onto Neidenburg, as the Russian I Corps became an ineffective force in the battle. Scholtz's XX Corps, to the north, also advanced. Though his 41st Infantry Division was badly mauled by Martos' Russian XV Corps, it held its ground, while the German 37th Infantry Division reached Hohenstein by the end of the day. The German 3rd Reserve Division was also able to advance on the Russian XV Corps, forcing Samsonov to order a retreat to Neidenburg. Von Below's German I Reserve Corps engaged Klyuev's Russian XIII Corps west of Allenstein, and became isolated. Klyuev received orders from Samsonov to retreat towards Kurken. Mackensen's German XVII Corps continued pursuing the retreating Russians. One half of the German encirclement was complete by the end of the day, as Ludendorff wrote, "The enemy front seemed to be breaking up... We did not have a clear picture of the situation with individual units. But there was no doubt that the battle was won."

On 29 August, von François' cavalry regiment reached Willenberg by evening, while his 1st Infantry Division occupied the road between Neidenburg and Willenberg. Von François' I Corps patrols linked up with Mackensen's German XVII Corps, who had advanced to Jedwabno, completing the encirclement. On 29 August the troops from the Russian Second Army's center who were retreating south ran into a German defensive line. Those Russians who tried to break through by dashing across open fields heavy with crops were mowed down. They were in a cauldron centered at Frogenau, west of Tannenberg, and throughout the day they were relentlessly pounded by artillery. Many surrendered — long columns of prisoners jammed the roads away from the battleground. Hindenburg and Ludendorff watched from a hilltop, with only a single field telephone line; thereafter they stayed closer to the telephone network. Hindenburg met one captured Russian corps commander that day, another on the day following. On 30 August the Russians remaining outside of the cauldron tried unsuccessfully to break open the snare. Rather than report the loss of his army to Tsar Nicholas II, Samsonov disappeared into the woods that night and committed suicide. His body was found in the following year and returned to Russia by the Red Cross.

On 31 August Hindenburg formally reported to the Kaiser that three Russian army corps (XIII, XV and XXIII) had been destroyed. The two corps (I and VI) that had not been caught in the cauldron had been severely bloodied and were retreating back to Poland. He requested that the battle be named Tannenberg (an imaginative touch that both Ludendorff and Hoffmann claimed as their own).

Samsonov's Second Army had been almost annihilated: 92,000 captured, 78,000 killed or wounded and only 10,000 (mostly from the retreating flanks) escaping. The Russians had lost 350 big guns. The Germans suffered just 12,000 casualties out of the 150,000 men committed to the battle. Sixty trains were required to take captured Russian equipment to Germany. The German official history estimated 50,000 Russians killed and wounded, which were never properly recorded. Another estimate gives 30,000 Russians killed or wounded, with 13 generals and 500 guns captured.

Samsonov's Second Army had been almost annihilated: 92,000 captured, 78,000 killed or wounded and only 10,000 (mostly from the retreating flanks) escaping. The Russians had lost 350 big guns. The Germans suffered just 12,000 casualties out of the 150,000 men committed to the battle. Sixty trains were required to take captured Russian equipment to Germany. The German official history estimated 50,000 Russians killed and wounded, which were never properly recorded. Another estimate gives 30,000 Russians killed or wounded, with 13 generals and 500 guns captured.

To David Stevenson it was "a major victory but far from decisive", because the Russian First Army was still in East Prussia. It set the stage for the

To David Stevenson it was "a major victory but far from decisive", because the Russian First Army was still in East Prussia. It set the stage for the  Hindenburg was hailed as an epic hero, Ludendorff was praised, but Hoffmann was generally ignored by the press. Apparently not pleased by this, he later gave tours of the area, noting, "This is where the Field Marshal slept before the battle, this is where he slept after the battle, and this is where he slept during the battle." However, Hindenburg countered by saying, "If the battle had gone badly, the name 'Hindenburg' would have been reviled from one end of Germany to the other." Hoffmann is not mentioned in Hindenburg's memoirs. In his memoirs Ludendorff takes credit for the encirclement and most historians give him full responsibility for conducting the battle. Hindenburg wrote and spoke of "we", and when questioned about the crucial tête-à-tête with Ludendorff after dinner on 26 August resolutely maintained that they had calmly discussed their options and resolved to continue with the encirclement. Military historian Walter Elze wrote that a few months before his death Hindenburg finally acknowledged that Ludendorff had been in a state of panic that evening. Hindenburg would also remark, "After all, I know something about the business, I was the instructor in tactics at the War Academy for six years".

Hindenburg was hailed as an epic hero, Ludendorff was praised, but Hoffmann was generally ignored by the press. Apparently not pleased by this, he later gave tours of the area, noting, "This is where the Field Marshal slept before the battle, this is where he slept after the battle, and this is where he slept during the battle." However, Hindenburg countered by saying, "If the battle had gone badly, the name 'Hindenburg' would have been reviled from one end of Germany to the other." Hoffmann is not mentioned in Hindenburg's memoirs. In his memoirs Ludendorff takes credit for the encirclement and most historians give him full responsibility for conducting the battle. Hindenburg wrote and spoke of "we", and when questioned about the crucial tête-à-tête with Ludendorff after dinner on 26 August resolutely maintained that they had calmly discussed their options and resolved to continue with the encirclement. Military historian Walter Elze wrote that a few months before his death Hindenburg finally acknowledged that Ludendorff had been in a state of panic that evening. Hindenburg would also remark, "After all, I know something about the business, I was the instructor in tactics at the War Academy for six years".

The Battle of Tannenberg, also known as the Second Battle of Tannenberg, was fought between

The Battle of Tannenberg, also known as the Second Battle of Tannenberg, was fought between Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

and Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

between 26 and 30 August 1914, the first month of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. The battle resulted in the almost complete destruction of the Russian Second Army and the suicide of its commanding general, Alexander Samsonov

Aleksandr Vasilyevich Samsonov (russian: Алекса́ндр Васи́льевич Самсо́нов, tr. ; ) was a career officer in the cavalry of the Imperial Russian Army and a general during the Russo-Japanese War and World War I. He ...

. A series of follow-up battles ( First Masurian Lakes) destroyed most of the First Army as well and kept the Russians off balance until the spring of 1915.

The battle is particularly notable for fast rail movements by the German Eighth Army, enabling them to concentrate against each of the two Russian armies in turn, first delaying the First Army and then destroying the Second before once again turning on the First days later. It is also notable for the failure of the Russians to encode their radio messages, broadcasting their daily marching orders in the clear, which allowed the Germans to make their movements with the confidence they would not be flanked.

The almost miraculous outcome brought considerable prestige to Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and his rising staff-officer Erich Ludendorff

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (9 April 1865 – 20 December 1937) was a German general, politician and military theorist. He achieved fame during World War I for his central role in the German victories at Liège and Tannenberg in 1914. ...

. Although the battle actually took place near Allenstein (Olsztyn

Olsztyn ( , ; german: Allenstein ; Old Prussian: ''Alnāsteini''

* Latin: ''Allenstenium'', ''Holstin'') is a city on the Łyna River in northern Poland. It is the capital of the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, and is a city with county rights. ...

), Hindenburg named it after Tannenberg, to the west, in order to avenge the Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians o ...

' defeat at the First Battle of Tannenberg 500 years earlier.

Background

Germany entered World War I largely following the Schlieffen Plan. According to Prit Buttar, "In combination with his own strong desire to fight an offensive war featuring outflanking and encircling movements, Schlieffen went on to develop his plan for a sweeping advance through Belgium. In the east, limited German forces would defend against any Russian attack until more forces became available from the west, fresh from victory over the French. The total strength of the fully mobilised German Army in 1914 amounted to 1,191 battalions, the great majority of which would be deployed against France. The Eighth Army in East Prussia would go to war with barely 10 per cent of this total." The French army'sPlan XVII

Plan XVII () was the name of a "scheme of mobilization and concentration" that was adopted by the French (the peacetime title of the French ) from 1912 to 1914, to be put into effect by the French Army in the event of war between France and G ...

at the outbreak of the war involved swift mobilization followed by an immediate attack to drive the Germans from Alsace and Lorraine. If the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) joined in accordance with their Allied treaty, they would fill the left flank. Their Russian allies in the East would have a massive army, more than 95 divisions, but their mobilization would inevitably be slower. Getting their men to the front would itself take time because of their relatively sparse and unreliable railway network (for example, 75% of the Russian railways were still single-tracked). Russia intended to have 27 divisions at the front by day 15 of hostilities and 52 by day 23, but it would take 60 days before 90 divisions were in action. Despite their difficulties, the Russians promised the French that they would promptly engage the armies of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

in the south and on day 15 would invade German East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label= Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

.

According to Prit Buttar, "In addition to the fortifications amongst the Masurian Lake District, the Germans had built a series of major forts around Königsberg

Königsberg (, ) was the historic Prussian city that is now Kaliningrad, Russia. Königsberg was founded in 1255 on the site of the ancient Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teutonic Knights during the Northern Crusades, and was ...

in the 19th century and had then modernised them over the years. Similarly, major fortresses had been established along the Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

, particularly at Thorn (now Toruń). Combined with the flexibility provided by the German railways, allowing General Maximilian von Prittwitz

Maximilian “Max” Wilhelm Gustav Moritz von Prittwitz und Gaffron (27 November 1848 – 29 March 1917) was an Imperial German general. He fought in the Austro-Prussian War, the Franco-Prussian War, and briefly in the First World War.

Famil ...

to concentrate against the inner flanks of either Russian invasion force, the Germans could realistically view the coming war with a degree of confidence."

The Russians would rely on two of their three railways that ran up to the border; each would provision an army. The railways ended at the border, as Russian trains operated on a different rail gauge

In rail transport, track gauge (in American English, alternatively track gage) is the distance between the two rails of a railway track. All vehicles on a rail network must have wheelsets that are compatible with the track gauge. Since many ...

from Western Europe. Consequently, its armies could be transported by rail only as far as the German border and could use Prussian railways only with captured locomotives and rolling stock. The First Army would use the line that ran from Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urba ...

, Lithuania, to the border southeast of Königsberg. The Second Army railway ran from Warsaw, Poland, to the border southwest of Königsberg. The two armies would take the Germans in a pincer. The Russian supply chains would be ungainly because—for defense—on their side of the border there were only a few sandy tracks rather than proper macadam

Macadam is a type of road construction, pioneered by Scottish engineer John Loudon McAdam around 1820, in which crushed stone is placed in shallow, convex layers and compacted thoroughly. A binding layer of stone dust (crushed stone from the ...

ized roads. Adding to their supply problems, the Russians deployed large numbers of cavalry and Cossacks; every day each horse needed ten times the resources that a man required.

The First Army commander was Paul von Rennenkampf, who in the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

had earned a reputation for "exceptional energy, determination, courage, and military capability."The First Army was mobilized from the Vilno Military District, and consisted of four infantry corps, five cavalry divisions and an independent cavalry brigade. The Second Army, commanded by Alexander Samsonov

Aleksandr Vasilyevich Samsonov (russian: Алекса́ндр Васи́льевич Самсо́нов, tr. ; ) was a career officer in the cavalry of the Imperial Russian Army and a general during the Russo-Japanese War and World War I. He ...

, was mobilized from the Warsaw Military District, and consisted of five infantry corps and four cavalry divisions. These two armies formed the Northwestern Front facing the Germans, under the command of Yakov Zhilinsky

Yakov Grigoryevich Zhilinsky (russian: Я́ков Григо́рьевич Жили́нский; 27 March 1853 – 1918) was a Russian cavalry general, chief of staff of the Imperial Russian Army from 2 February 1911 to 4 March 1914. He was co ...

. The Southwestern Front, facing the Austro-Hungarians in Galicia, was commanded by Nikolai Iudovich Ivanov.

Communications would be a daunting challenge. The Russian supply of cable was insufficient to run telephone or telegraph connections from the rear; all they had was needed for field communications. Therefore, they relied on mobile wireless stations, which would link Zhilinskiy to his two army commanders and with all corps commanders. The Russians were aware that the Germans had broken their ciphers, but they continued to use them until war broke out. A new code was ready but they were still very short of code books. Zhilinskiy and Rennenkampf each had one; Samsonov did not. According to Prit Buttar, "Consequently, Samsonov concluded that he would have to take the risk of using uncoded radio messages."

Prelude: 17–22 August

Rennenkampf's First Army crossed the frontier on 17 August, moving westward slowly. This was sooner than the Germans anticipated, because the Russian mobilization, including the Baltic and Warsaw districts, had begun secretly on 25 July, not with the Tsar's proclamation on 30 July. Prittwitz attacked near Gumbinnen on 20 August, when he knew from intercepted wireless messages that Rennenkampf's infantry was resting. GermanI Corps I Corps, 1st Corps, or First Corps may refer to:

France

* 1st Army Corps (France)

* I Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* I Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Ar ...

commanded by Gen. Hermann von François was on their left, XVII Corps commanded by Lt. Gen. August von Mackensen

Anton Ludwig Friedrich August von Mackensen (born Mackensen; 6 December 1849 – 8 November 1945), ennobled as "von Mackensen" in 1899, was a German field marshal. He commanded successfully during World War I of 1914–1918 and became one of ...

in the center and I Reserve Corps led by Gen. Otto von Below on the right. A night march enabled one of François’ divisions to hit the Russian XX Corps' right flank at 04:00. Rennenkampf's men rallied to stoutly resist the attack. Their artillery was devastating until they ran out of ammunition, then the Russians retired. I Corps attacks were halted at 16:00 to rest men sapped by the torrid summer heat. François was sure they could win the next day. On his left, Mackensen's XVII Corps launched a vigorous frontal attack but the Russian infantry held firm. That afternoon the Russian heavy artillery struck back—the German infantry fled in panic, their artillery limbered up and joined the stampede. Prittwitz ordered I Corps and I Reserve Corps to break off the action and retreat also.

At noon, Prittwitz had telephoned Field Marshal von Moltke at OHL ( Oberste Heeresleitung, Supreme Headquarters) to report that all was going well; that evening he telephoned again to report disaster. His problems were compounded because an intercepted wireless message disclosed that the Russian II Army included five Corps and a cavalry division, and aerial scouts saw their columns marching across the frontier. They were opposed by a single reinforced German Corps, the XX, commanded by Lt. Gen. Friedrich von Scholtz. Their advance offered the possibility of cutting off any retreat westward while possibly encircling them between the two Russian armies. Prittwitz excitedly but inconclusively and repeatedly discussed the horrifying news with Moltke that evening on the telephone, shouting back and forth. At 20:23 Eighth Army telegraphed OHL that they would withdraw to West Prussia.

By the next morning, 21 August, Eighth Army staff realized that because Samsonov's II Army was closer to the Vistula crossings than they were, they must first relocate most of their forces to join with XX Corps to block Samsonov before they could withdraw further. Now Moltke was told that they would only retreat a short distance. François protested directly to the Kaiser about his panicking superiors. That evening Prittwitz reported that the German 1st Cavalry Division had disappeared, only to later disclose that they had repulsed the Russian cavalry, capturing several hundred. By this point, Moltke had already decided to replace both Prittwitz and his chief of staff, Alfred von Waldersee. On the morning of 22 August their replacements, Col. Gen.

By the next morning, 21 August, Eighth Army staff realized that because Samsonov's II Army was closer to the Vistula crossings than they were, they must first relocate most of their forces to join with XX Corps to block Samsonov before they could withdraw further. Now Moltke was told that they would only retreat a short distance. François protested directly to the Kaiser about his panicking superiors. That evening Prittwitz reported that the German 1st Cavalry Division had disappeared, only to later disclose that they had repulsed the Russian cavalry, capturing several hundred. By this point, Moltke had already decided to replace both Prittwitz and his chief of staff, Alfred von Waldersee. On the morning of 22 August their replacements, Col. Gen. Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fr ...

and Maj. Gen. Erich Ludendorff

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (9 April 1865 – 20 December 1937) was a German general, politician and military theorist. He achieved fame during World War I for his central role in the German victories at Liège and Tannenberg in 1914. ...

, were notified of their new assignments.

The Eighth Army issued orders to move to block Samsonov's Second Army. I Corps on the German left was closest to the railway, so it would take the long route by train to form up on the right side of XX Corps. The other two German corps would march the shorter distance to XX Corps' left. The First Cavalry Division and some older garrison troops would remain to screen Rennenkampf. On the afternoon of 22 August, the head of the Eighth Army field railways was informed by telegraph that new commanders were coming by special train. The telegram relieving their former commanders came later. I Corps was moving over more than 150 km (93 miles) of rail, day and night, one train every 30 minutes, with 25 minutes to unload instead of the customary hour or two.

After the battle at Gumbinnen, Rennenkampf decided to pause his First Army to take resupply and to be in good positions if the Germans attacked again. This caused them to lose contact with the German Army, which he incorrectly reported was retreating in haste to the Vistula. Both Russian armies were having serious supply problems; everything had to be carted up from the railheads because they could not use the East Prussian railway track, and many units were hampered by a lack of field bakeries, ammunition carts and the like. The Second Army also was hampered by incompetent staff work and poor communications. Poor staff work not only exacerbated supply problems but, more importantly, caused Samsonov during the fighting to lose operational control over all but the two corps in his immediate vicinity (XIII & XV Corps).

On 21 August, Samsonov's Second Army crossed the border, and quickly took several border towns. The VI Corps took Ortelsburg, while I and XV Corps advanced onto Soldau and Neidenburg. On 22 August, Samsonov ordered XV Corps to advance towards Hohenstein, which they did on 23 August pushing Friedrich von Scholtz's XX Corps out of Lahna.

Battle

Consolidation of the German Eighth Army

The new commanders arrived at Marienburg on the afternoon of 23 August; they had met for the first time on their special train the previous night and now they rendezvoused with the Eighth Army staff. I Corps was moving by the rail line, and Ludendorff had previously counter-ordered it further east, at Deutsch-Eylau, where it could support the right of XX Corps. XVII Corps and I Reserve Corps would march towards the left of XX Corps. Ludendorff had delayed their marches for a day to rest while remaining in place should Rennenkampf attack. The German 1st Cavalry Division and some garrison troops of older men would remain as a screen just south of the eastern edge of the Königsberg defenses, facing Rennenkampf's First Army. Hindenburg summarized his strategy, "We had not merely to win a victory over Samsonov. We had to annihilate him. Only thus could we get a free hand to deal with the second enemy, Rennenkampf, who was even then plundering and burning East Prussia." The new commander had raised the stakes dramatically. They must do more than stop Samsonov in his tracks, as they had tried to block and push back Rennenkampf. Samsonov must be annihilated before they turned back to deal with Rennenkampf. For the moment Samsonov would be opposed only by the forces he was already facing, XX Corps, mostly East Prussians who were defending their homes. The bulk of the Second Russian Army was still coming towards the front; if necessary, they would be allowed to push further into the province while the German reinforcements assembled on the flanks, poised to encircle the invaders—just the tactics instilled by Schlieffen.Early phases of battle: 23–26 August

Zhilinskiy had agreed to Samsonov's proposal to start the Second Army's advance further westward than originally planned, separating them even further from Rennenkampf's First Army. On 22 August Samsonov's forces encountered Germans all along their front and pushed them back in several places. Zhilinskiy ordered him to pursue vigorously. They already had been advancing for six days in sweltering heat without sufficient rest along primitive roads, averaging a day and had outrun their supplies. On 23 August they attacked the German XX Corps, which retreated to the Orlau-Frankenau line that night. The Russians followed, and on the 24th they attacked again; the now partially entrenched XX Corps temporarily stopped their advance before retreating to avoid possible encirclement. At one stage the chief of staff of the corps directed artillery fire onto his own dwelling. Samsonov saw a wonderful opportunity because, as far as he was aware, both of his flanks were unopposed. He ordered most of his units to the northwest, toward the Vistula, leaving only his VI Corps to continue north towards their original objective of Seeburg. He did not have enough aircraft or skilled cavalry to detect the German buildup on his left. Rennenkampf mistakenly reported that two of the German Corps had sheltered in the Königsberg fortifications. On 24 August Hindenburg, Ludendorff and Hoffmann motored along the German lines to meet Scholtz and his principal subordinates, sharing the roads with panic-stricken refugees; in the background were columns of smoke from burning villages ignited by artillery shells. They could keep control of their army because most of the local telephone operators remained at their switchboards, carefully tracking the motorcade. Along the way they drove through the village of Tannenberg, which reminded the two younger men of the defeat of the Teutonic Knights there by the Poles and Lithuanians in 1410; Hindenburg had been thinking about that battle since the evening before when he strolled near the ruins of the castle of the Teutonic Order. (In 1910 Slavs had commemorated their triumph on the old battlefield.)

Aided by Russian radio intercepts, a captured map of Russian positions, and information from fleeing German civilians of Rennenkampf's slow progress, Hindenburg and Ludendorff planned the encirclement of the Russian Second Army. I Corps and XX Corps would attack from Gilgenburg towards Neidenburg, while XVII Corps and I Reserve Corps attacked the Russian right flank. They met with Scholtz and his XX Corps staff on 24 August, and François on 25 August, where he was ordered to attack towards Usdau on 26 August. François stated only part of his corps and artillery had arrived. Ludendorf insisted the attack must go forward as planned, since more trains were expected beforehand. François replied, "If it is so ordered, of course an attack will be made, and the troops will obviously have to fight with bayonets."

On the way back to headquarters Hoffmann received new radio intercepts. Rennenkampf's most recent orders from Zhilinskiy were to continue due west, not turn south-westward towards Samsonov, who was instructed to continue his own drive northwest further away from Rennenkampf. Based on this information Scholtz formed a new defensive flank along the Drewenz River, while his main line strengthened their defenses. Back at headquarters Hindenburg told the staff, "Gentlemen. Our preparations are so well in hand that we can sleep soundly tonight."

Samsonov was concerned by the German resistance with their earlier advance, and aerial reconnaissance spotted the arrival of the German I Corps. However, Samsonov was ordered by Zhilinski to attack northwest with Martos' XV Corps, and Klyuev's XII Corps, while I Corps protected the left flank, and VI Corps was positioned on the right at

On 24 August Hindenburg, Ludendorff and Hoffmann motored along the German lines to meet Scholtz and his principal subordinates, sharing the roads with panic-stricken refugees; in the background were columns of smoke from burning villages ignited by artillery shells. They could keep control of their army because most of the local telephone operators remained at their switchboards, carefully tracking the motorcade. Along the way they drove through the village of Tannenberg, which reminded the two younger men of the defeat of the Teutonic Knights there by the Poles and Lithuanians in 1410; Hindenburg had been thinking about that battle since the evening before when he strolled near the ruins of the castle of the Teutonic Order. (In 1910 Slavs had commemorated their triumph on the old battlefield.)

Aided by Russian radio intercepts, a captured map of Russian positions, and information from fleeing German civilians of Rennenkampf's slow progress, Hindenburg and Ludendorff planned the encirclement of the Russian Second Army. I Corps and XX Corps would attack from Gilgenburg towards Neidenburg, while XVII Corps and I Reserve Corps attacked the Russian right flank. They met with Scholtz and his XX Corps staff on 24 August, and François on 25 August, where he was ordered to attack towards Usdau on 26 August. François stated only part of his corps and artillery had arrived. Ludendorf insisted the attack must go forward as planned, since more trains were expected beforehand. François replied, "If it is so ordered, of course an attack will be made, and the troops will obviously have to fight with bayonets."

On the way back to headquarters Hoffmann received new radio intercepts. Rennenkampf's most recent orders from Zhilinskiy were to continue due west, not turn south-westward towards Samsonov, who was instructed to continue his own drive northwest further away from Rennenkampf. Based on this information Scholtz formed a new defensive flank along the Drewenz River, while his main line strengthened their defenses. Back at headquarters Hindenburg told the staff, "Gentlemen. Our preparations are so well in hand that we can sleep soundly tonight."

Samsonov was concerned by the German resistance with their earlier advance, and aerial reconnaissance spotted the arrival of the German I Corps. However, Samsonov was ordered by Zhilinski to attack northwest with Martos' XV Corps, and Klyuev's XII Corps, while I Corps protected the left flank, and VI Corps was positioned on the right at Bischofsburg

Biskupiec (german: Bischofsburg, ) is a town in northern Poland, in Warmia, in the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship. It is located in Olsztyn County and, as of December 2021, it has a population of 10,496. The countryside surrounding Biskupiec is ...

.

Main battle: 27–30 August

Zhilinskiy was visited by the commander of the Russian Army, the Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich of Russia, who ordered him to support Samsonov.

Von François commenced his attack early on the 25th, with his 1st Infantry Division advancing towards Seeben, his 2nd Infantry division on its southern flank, and the rest of his corps arriving by train during the day. He captured Seeben by mid-afternoon, but saved an advance on Usdau for the next day. North of von François, Scholtz's 37th and 41st Infantry Divisions faced the Russian 2nd Infantry Division, which fell back with heavy losses. On the left flank of Scholtz's XX Corps, Curt von Morgen's 3rd Reserve Division was ordered to advance onto Hohenstein, but held back out of concern that the Russian XV and XII Corps would threaten his left flank. Klyuev's Russian XIII Corps was ordered to advance onto

Zhilinskiy was visited by the commander of the Russian Army, the Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich of Russia, who ordered him to support Samsonov.

Von François commenced his attack early on the 25th, with his 1st Infantry Division advancing towards Seeben, his 2nd Infantry division on its southern flank, and the rest of his corps arriving by train during the day. He captured Seeben by mid-afternoon, but saved an advance on Usdau for the next day. North of von François, Scholtz's 37th and 41st Infantry Divisions faced the Russian 2nd Infantry Division, which fell back with heavy losses. On the left flank of Scholtz's XX Corps, Curt von Morgen's 3rd Reserve Division was ordered to advance onto Hohenstein, but held back out of concern that the Russian XV and XII Corps would threaten his left flank. Klyuev's Russian XIII Corps was ordered to advance onto Allenstein

Olsztyn ( , ; german: Allenstein ; Old Prussian: ''Alnāsteini''

* Latin: ''Allenstenium'', ''Holstin'') is a city on the Łyna River in northern Poland. It is the capital of the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, and is a city with county rights. ...

. On Samsonov's right flank, Alexander Blagoveschensky's Russian VI corps soon faced Mackensen's German XVII Corps and von Below's German I Reserve Corps. Von Below, to the right of Mackensen, advanced to cut the road between Bischofsburg and Wartenburg. Blagoveschensky's 16th Infantry Division occupied Bischofsburg, while his 4th Infantry Division was north of Rothfliess, and his 4th Cavalry division was at Sensburg. The 16th Infantry division was ordered to move towards Allenstein, while the 16th Infantry Division was split between Lautern and Gross-Bössau. Mackensen's 36th Infantry Division, on the right, and his 35th infantry Division, on the left, advanced towards Bischofsburg. The Russian 4th Infantry Division suffered heavy losses and retreated towards Ortelsburg. In an attempt to send reinforcements, Blagoveschensky split the 16th Infantry Division between Bischofsburg and Ramsau. However, they were met in the flank and rear by von Belows's I Reserve Corps, and retreated in disarray.

Samsonov's Second Army had been almost annihilated: 92,000 captured, 78,000 killed or wounded and only 10,000 (mostly from the retreating flanks) escaping. The Russians had lost 350 big guns. The Germans suffered just 12,000 casualties out of the 150,000 men committed to the battle. Sixty trains were required to take captured Russian equipment to Germany. The German official history estimated 50,000 Russians killed and wounded, which were never properly recorded. Another estimate gives 30,000 Russians killed or wounded, with 13 generals and 500 guns captured.

Samsonov's Second Army had been almost annihilated: 92,000 captured, 78,000 killed or wounded and only 10,000 (mostly from the retreating flanks) escaping. The Russians had lost 350 big guns. The Germans suffered just 12,000 casualties out of the 150,000 men committed to the battle. Sixty trains were required to take captured Russian equipment to Germany. The German official history estimated 50,000 Russians killed and wounded, which were never properly recorded. Another estimate gives 30,000 Russians killed or wounded, with 13 generals and 500 guns captured.

Aftermath

To David Stevenson it was "a major victory but far from decisive", because the Russian First Army was still in East Prussia. It set the stage for the

To David Stevenson it was "a major victory but far from decisive", because the Russian First Army was still in East Prussia. It set the stage for the First Battle of the Masurian Lakes

The First Battle of the Masurian Lakes was a German offensive in the Eastern Front 2–16 September 1914, during the second month of World War I. It took place only days after the Battle of Tannenberg where the German Eighth Army encircled a ...

a week later, when the reinforced German Eighth Army confronted the Russian First Army. Rennenkampf retreated hastily back over the pre-war border before they could be encircled. The battle was humiliating to Russia as it meant their army was weak.

Field Marshal Sir Edmund Ironside saw Tannenberg as the "… greatest defeat suffered by any of the combatants during the war". It was a tactical masterpiece that demonstrated the superior skills of the German army. Their pre-war organization and training had proven themselves, which bolstered German morale while severely shaking Russian confidence. Nonetheless, as long as the great battle in the West continued the outnumbered Germans had to remain on the defensive in the East, anticipating that the Russians would make another thrust from Poland against Germany, and because the Russians had defeated the Austro-Hungarians in the Battle of Galicia

The Battle of Galicia, also known as the Battle of Lemberg, was a major battle between Russia and Austria-Hungary during the early stages of World War I in 1914. In the course of the battle, the Austro-Hungarian armies were severely defeated an ...

; their allies would need help.

The Russian official inquiry into the disaster blamed Zhilinskiy for not controlling his two armies. He was replaced in the Northwest Command and sent to liaise with the French. Rennenkampf was exonerated, but was retired after a dubious performance in Poland in 1916.

Hindenburg was hailed as an epic hero, Ludendorff was praised, but Hoffmann was generally ignored by the press. Apparently not pleased by this, he later gave tours of the area, noting, "This is where the Field Marshal slept before the battle, this is where he slept after the battle, and this is where he slept during the battle." However, Hindenburg countered by saying, "If the battle had gone badly, the name 'Hindenburg' would have been reviled from one end of Germany to the other." Hoffmann is not mentioned in Hindenburg's memoirs. In his memoirs Ludendorff takes credit for the encirclement and most historians give him full responsibility for conducting the battle. Hindenburg wrote and spoke of "we", and when questioned about the crucial tête-à-tête with Ludendorff after dinner on 26 August resolutely maintained that they had calmly discussed their options and resolved to continue with the encirclement. Military historian Walter Elze wrote that a few months before his death Hindenburg finally acknowledged that Ludendorff had been in a state of panic that evening. Hindenburg would also remark, "After all, I know something about the business, I was the instructor in tactics at the War Academy for six years".

Hindenburg was hailed as an epic hero, Ludendorff was praised, but Hoffmann was generally ignored by the press. Apparently not pleased by this, he later gave tours of the area, noting, "This is where the Field Marshal slept before the battle, this is where he slept after the battle, and this is where he slept during the battle." However, Hindenburg countered by saying, "If the battle had gone badly, the name 'Hindenburg' would have been reviled from one end of Germany to the other." Hoffmann is not mentioned in Hindenburg's memoirs. In his memoirs Ludendorff takes credit for the encirclement and most historians give him full responsibility for conducting the battle. Hindenburg wrote and spoke of "we", and when questioned about the crucial tête-à-tête with Ludendorff after dinner on 26 August resolutely maintained that they had calmly discussed their options and resolved to continue with the encirclement. Military historian Walter Elze wrote that a few months before his death Hindenburg finally acknowledged that Ludendorff had been in a state of panic that evening. Hindenburg would also remark, "After all, I know something about the business, I was the instructor in tactics at the War Academy for six years".

Post-war legacy

A German monument commemorating the battle was completed in 1927 in Hohenstein. However, it was blown up inWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

by the Germans during their retreat from Prussia in January 1945.

German film director Heinz Paul

Heinz Paul (13 August 1893 – 14 March 1983) was a German screenwriter, film producer and director. He was married to the actress Hella Moja.

Selected filmography Director

* '' The Street of Forgetting'' (1923)

* '' The Dice Game of Life'' (1925) ...

made a film, '' Tannenberg'', about the battle, shot in East Prussia in 1932.

The battle is at the center of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian novelist. One of the most famous Soviet dissidents, Solzhenitsyn was an outspoken critic of communism and helped to raise global awareness of political repr ...

's novel '' August 1914'', published in 1971, and is featured in the video games ''Darkest of Days

''Darkest of Days'' is a first-person shooter video game developed by 8monkey Labs and published by Phantom EFX. Originally released for the Xbox 360, it was also released for Microsoft Windows via Steam. On December 30, 2010, Virtual Programmin ...

'' and '' Tannenberg''.

See also

*References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Tannenberg 1914 1914 in Germany 1914 in the Russian Empire August 1914 events Battles of the Eastern Front (World War I) Battles of World War I involving Germany Battles of World War I involving Russia Conflicts in 1914 East Prussia Paul von Hindenburg