Battle of Kiev (1941) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

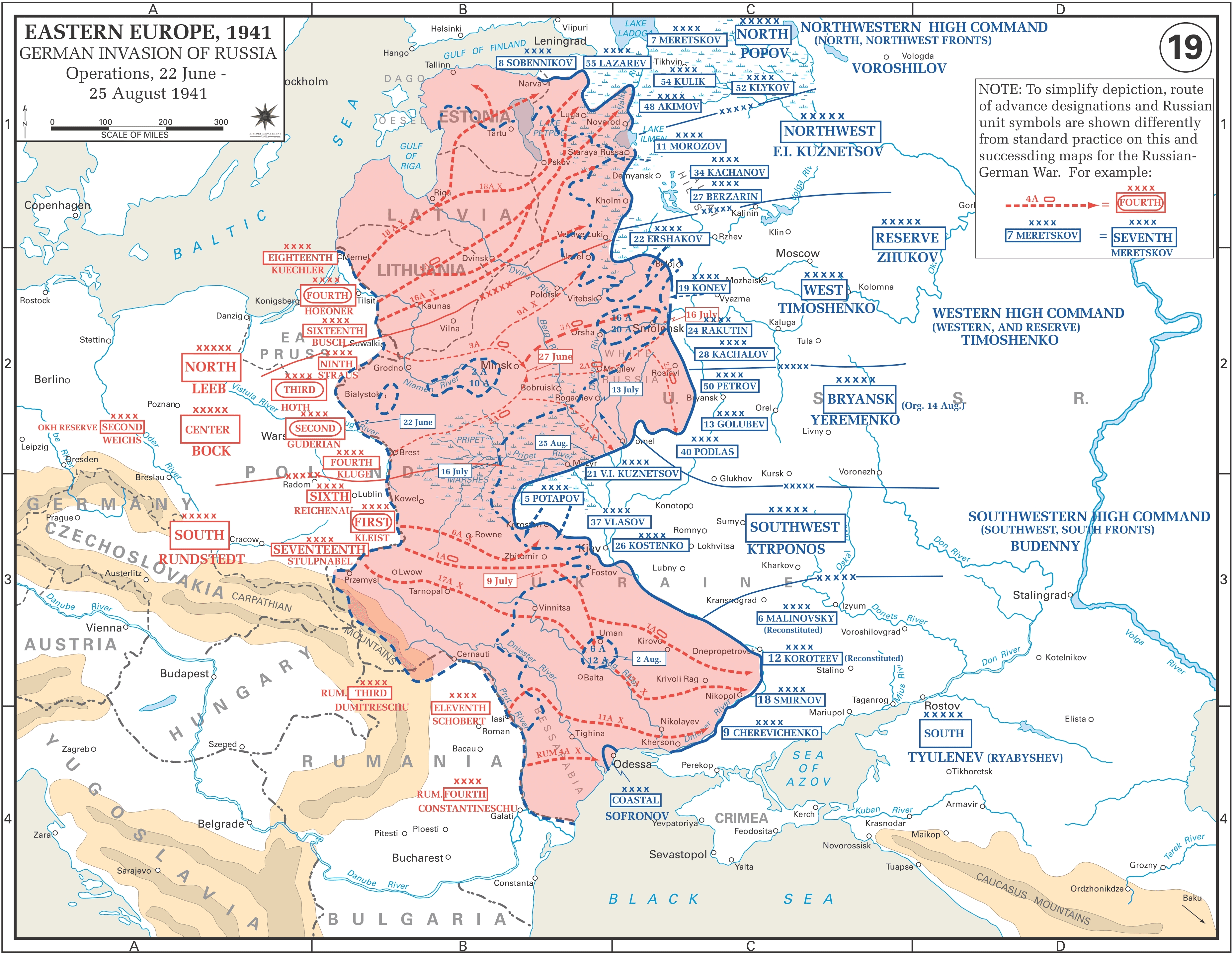

The First Battle of Kiev was the German name for the operation that resulted in a huge

The 1941 Kiev Defense Operation (КИЇВСЬКА ОБОРОННА ОПЕРАЦІЯ 1941)

'. Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine By 11 July 1941, the Axis ground forces reached the Dnieper tributary Irpin River ( to the west from

On 20 August, Hitler rejected the proposal based on the idea that the most important objective was to deprive the Soviet Union of its industrial areas. On 21 August,

On 20 August, Hitler rejected the proposal based on the idea that the most important objective was to deprive the Soviet Union of its industrial areas. On 21 August,  The bulk of the 2nd Panzer Group and the 2nd Army were detached from Army Group Centre and sent south. Its mission was to encircle the Southwestern Front, commanded by

The bulk of the 2nd Panzer Group and the 2nd Army were detached from Army Group Centre and sent south. Its mission was to encircle the Southwestern Front, commanded by

The Panzer armies made rapid progress. On 12 September, Ewald von Kleist's 1st Panzer Group, which had by now turned north and crossed the Dnieper river, emerged from its bridgeheads at

The Panzer armies made rapid progress. On 12 September, Ewald von Kleist's 1st Panzer Group, which had by now turned north and crossed the Dnieper river, emerged from its bridgeheads at

By virtue of Guderian's southward turn, the Wehrmacht destroyed the entire Southwestern Front east of Kiev during September. It inflicted nearly 700,544 casualties on the Red Army, while Soviet forces west of Moscow conducted many attacks on Army Group Centre. Although most of these attacks failed, the Soviet attacks in the Yelnya Offensive succeeded with the German forces abandoning the town, and resulted in the first major defeat for the Wehrmacht in

By virtue of Guderian's southward turn, the Wehrmacht destroyed the entire Southwestern Front east of Kiev during September. It inflicted nearly 700,544 casualties on the Red Army, while Soviet forces west of Moscow conducted many attacks on Army Group Centre. Although most of these attacks failed, the Soviet attacks in the Yelnya Offensive succeeded with the German forces abandoning the town, and resulted in the first major defeat for the Wehrmacht in F-10 OBJECT RADIO-CONTROLLED MINE

at shvachko.net: retrieved 30 November 2022

Immediately after World War II ended, prominent German commanders argued that had operations at Kiev been delayed, and had Operation Typhoon been launched in September, rather than October, the German Army would have reached and captured Moscow before the onset of winter.

Immediately after World War II ended, prominent German commanders argued that had operations at Kiev been delayed, and had Operation Typhoon been launched in September, rather than October, the German Army would have reached and captured Moscow before the onset of winter.

encirclement

Encirclement is a military term for the situation when a force or target is isolated and surrounded by enemy forces. The situation is highly dangerous for the encircled force. At the strategic level, it cannot receive supplies or reinforcemen ...

of Soviet troops in the vicinity of Kiev during World War II. This encirclement is considered the largest encirclement

Encirclement is a military term for the situation when a force or target is isolated and surrounded by enemy forces. The situation is highly dangerous for the encircled force. At the strategic level, it cannot receive supplies or reinforcemen ...

in the history of warfare (by number of troops). The operation ran from 7 July to 26 September 1941, as part of Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

, the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

.

Much of the Southwestern Front of the Red Army (commanded by Mikhail Kirponos) was encircled, but small groups of Red Army troops managed to escape the pocket

A pocket is a bag- or envelope-like receptacle either fastened to or inserted in an article of clothing to hold small items. Pockets are also attached to luggage, backpacks, and similar items. In older usage, a pocket was a separate small bag ...

days after the German panzers met east of the city, including the headquarters of Marshal Semyon Budyonny

Semyon Mikhailovich Budyonnyy ( rus, Семён Миха́йлович Будённый, Semyon Mikháylovich Budyonnyy, p=sʲɪˈmʲɵn mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ bʊˈdʲɵnːɨj, a=ru-Simeon Budyonniy.ogg; – 26 October 1973) was a Russian ca ...

, Marshal Semyon Timoshenko

Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko (russian: link=no, Семён Константи́нович Тимоше́нко, ''Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko''; uk, Семе́н Костянти́нович Тимоше́нко, ''Semen Kostiantyno ...

and Commissar

Commissar (or sometimes ''Kommissar'') is an English transliteration of the Russian (''komissar''), which means ' commissary'. In English, the transliteration ''commissar'' often refers specifically to the political commissars of Soviet and E ...

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

. Kirponos was trapped behind German lines and was killed while trying to break out.

The battle was an unprecedented defeat for the Red Army, exceeding even the Battle of Białystok–Minsk

The Battle of Białystok–Minsk was a German strategic operation conducted by the Wehrmacht's Army Group Centre under Field Marshal Fedor von Bock during the penetration of the Soviet border region in the opening stage of Operation Barbarossa, ...

of June–July 1941. The encirclement trapped 452,700 soldiers, 2,642 guns and mortars, and 64 tanks, of which scarcely 15,000 had escaped from the encirclement by 2 October. The Southwestern Front suffered 700,544 casualties, including 616,304 killed, captured, or missing during the battle. The 5th

Fifth is the ordinal form of the number five.

Fifth or The Fifth may refer to:

* Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as in the expression "pleading the Fifth"

* Fifth column, a political term

* Fifth disease, a contagious rash tha ...

, 37th, 26th, 21st

21 (twenty-one) is the natural number following 20 and preceding 22.

The current century is the 21st century AD, under the Gregorian calendar.

In mathematics

21 is:

* a composite number, its proper divisors being 1, 3 and 7, and a defici ...

, and 38th armies, consisting of 43 divisions, were almost annihilated and the 40th Army

The 40th Army (, ''40-ya obshchevoyskovaya armiya'', "40th Combined Arms Army") of the Soviet Ground Forces was an army-level command that participated in World War II from 1941 to 1945 and was reformed specifically for the Soviet–Afghan War fr ...

suffered many losses. Like the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

before it, the Southwestern Front had to be recreated almost from scratch.

Prelude

July

After the rapid progress ofArmy Group Centre

Army Group Centre (german: Heeresgruppe Mitte) was the name of two distinct strategic German Army Groups that fought on the Eastern Front in World War II. The first Army Group Centre was created on 22 June 1941, as one of three German Army for ...

through the central sector of the Eastern front, a huge salient developed around its junction with Army Group South

Army Group South (german: Heeresgruppe Süd) was the name of three German Army Groups during World War II.

It was first used in the 1939 September Campaign, along with Army Group North to invade Poland. In the invasion of Poland Army Group So ...

by late July 1941. On 7–8 July 1941, the German forces managed to break through the fortified Stalin Line, in the southeast portion of Zhytomyr Oblast

Zhytomyr Oblast ( uk, Жито́мирська о́бласть, translit=Zhytomyrska oblast), also referred to as Zhytomyrshchyna ( uk, Жито́мирщина}) is an oblast (province) of northern Ukraine. The administrative center of the obla ...

, which ran along the 1939 Soviet border.Koval, M. The 1941 Kiev Defense Operation (КИЇВСЬКА ОБОРОННА ОПЕРАЦІЯ 1941)

'. Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine By 11 July 1941, the Axis ground forces reached the Dnieper tributary Irpin River ( to the west from

Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

). The initial attempt to enter the city right away was thwarted by troops of the Kiev ukrep-raion (KUR, Kiev fortified district) and counter offensive of 5th

Fifth is the ordinal form of the number five.

Fifth or The Fifth may refer to:

* Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as in the expression "pleading the Fifth"

* Fifth column, a political term

* Fifth disease, a contagious rash tha ...

and 6th

6 (six) is the natural number following 5 and preceding 7. It is a composite number and the smallest perfect number.

In mathematics

Six is the smallest positive integer which is neither a square number nor a prime number; it is the second ...

armies. Following that the advance on Kiev was halted and main effort shifted towards the Korosten ukrep-raion where the Soviet 5th Army was concentrated. At the same time the 1st Panzer Army

The 1st Panzer Army (german: 1. Panzerarmee) was a German tank army that was a large armoured formation of the Wehrmacht during World War II.

When originally formed on 1 March 1940, the predecessor of the 1st Panzer Army was named Panzer Gro ...

was forced to transition to defense due to a counteroffensive of the Soviet 26th Army. A substantial Soviet force, nearly the entire Southwestern Front, positioned in and around Kiev was located in the salient. By the end of July, the Soviet front lost some of its units due to the critical situation of the Southern Front (6th and 12th armies) caused by the German 17th army.

While lacking mobility and armor, due to high losses in tanks at the Battle of Uman, on 3 August 1941, they nonetheless posed a significant threat to the German advance and were the largest single concentration of Soviet troops on the Eastern Front at that time. Both Soviet 6th and 12th armies were encircled at Uman

Uman ( uk, Умань, ; pl, Humań; yi, אומאַן) is a city located in Cherkasy Oblast in central Ukraine, to the east of Vinnytsia. Located in the historical region of the eastern Podolia, the city rests on the banks of the Umanka River ...

, where some 102,000 Red Army soldiers and officers were taken prisoner. On 30 July 1941, the German forces resumed their advance onto Kiev, with the German 6th army attacking positions between the Soviet 26th army and the Kiev ukrep-raion troops.

August

On 7 August 1941, their advance was halted again by the Soviet 5th, 37th, and 26th armies, supported by the Pinsk Naval Flotilla. With the help of the local population around the city of Kiev, anti-tanks ditches were dug and other obstacles were installed, including the establishment of 750 pillboxes and 100,000 mines planted along the frontline segment. Some 35,000 soldiers were mobilized from local population along with some partisan detachments and twoarmored train

An armoured train is a railway train protected with armour. Armoured trains usually include railway wagons armed with artillery, machine guns and autocannons. Some also had slits used to fire small arms from the inside of the train, a facili ...

s.

On 19 July, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

had issued Directive No. 33, which cancelled the assault on Moscow in favor of driving south to complete the encirclement of Soviet forces surrounded in Kiev. On 12 August 1941, Supplement to Directive No. 34 was issued. This directive represented a compromise between Hitler, who was convinced the correct strategy was to clear the salient occupied by Soviet forces on right flank of Army Group Center, in the vicinity of Kiev, before resuming the drive to Moscow, and Franz Halder

Franz Halder (30 June 1884 – 2 April 1972) was a German general and the chief of staff of the Army High Command (OKH) in Nazi Germany from 1938 until September 1942. During World War II, he directed the planning and implementation of Operati ...

, Fedor von Bock

Moritz Albrecht Franz Friedrich Fedor von Bock (3 December 1880 – 4 May 1945) was a German who served in the German Army during the Second World War. Bock served as the commander of Army Group North during the Invasion of Poland ...

and Heinz Guderian

Heinz Wilhelm Guderian (; 17 June 1888 – 14 May 1954) was a German general during World War II who, after the war, became a successful memoirist. An early pioneer and advocate of the "blitzkrieg" approach, he played a central role in th ...

, who advocated an advance on Moscow, as soon as possible. The compromise required 2nd and 3rd

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (disambiguation)

* Third Avenue (disambiguation)

* H ...

Panzer Groups of Army Group Centre, which were redeploying in order to aid Army Group North

Army Group North (german: Heeresgruppe Nord) was a German strategic formation, commanding a grouping of field armies during World War II. The German Army Group was subordinated to the ''Oberkommando des Heeres'' (OKH), the German army high comman ...

and Army Group South respectively, be returned to Army Group Centre, together with the 4th Panzer Group

The 4th Panzer Army (german: 4. Panzerarmee) (operating as Panzer Group 4 (german: 4. Panzergruppe) from its formation on 15 February 1941 to 1 January 1942, when it was redesignated as a full army) was a German panzer formation during World War ...

of Army Group North, once their objectives were achieved. Then the three Panzer Groups, under the control of Army Group Center, would lead the advance on Moscow. Initially, Halder, chief of staff of the Oberkommando des Heeres

The (; abbreviated OKH) was the high command of the Army of Nazi Germany. It was founded in 1935 as part of Adolf Hitler's rearmament of Germany. OKH was ''de facto'' the most important unit within the German war planning until the defeat at ...

(OKH), and Bock, commander of Army Group Center, were satisfied by the compromise, but soon their optimism faded as the operational realities of the plan proved too challenging.

On 18 August, the OKH submitted a strategic survey (''Denkschrift'') to Hitler, regarding the continuation of operations in the East. The paper made the case for the drive to Moscow, arguing once again that Army Groups North and South were strong enough to accomplish their objectives without any assistance from Army Group Center. It pointed out that there was enough time left before winter to conduct only a single decisive operation against Moscow.

On 20 August, Hitler rejected the proposal based on the idea that the most important objective was to deprive the Soviet Union of its industrial areas. On 21 August,

On 20 August, Hitler rejected the proposal based on the idea that the most important objective was to deprive the Soviet Union of its industrial areas. On 21 August, Alfred Jodl

Alfred Josef Ferdinand Jodl (; 10 May 1890 – 16 October 1946) was a German '' Generaloberst'' who served as the chief of the Operations Staff of the '' Oberkommando der Wehrmacht'' – the German Armed Forces High Command – throughout Worl ...

of Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) issued a directive, which summarized Hitler's instructions, to Walther von Brauchitsch

Walther Heinrich Alfred Hermann von Brauchitsch (4 October 1881 – 18 October 1948) was a German field marshal and the Commander-in-Chief (''Oberbefehlshaber'') of the German Army during World War II. Born into an aristocratic military family, ...

, commander-in-chief of the Army. The paper reiterated that the capture of Moscow, before the onset of winter, was not a primary objective. Rather, that the most important missions before the onset of winter were to seize the Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a p ...

, and the industrial and coal region of the Don River

The Don ( rus, Дон, p=don) is the fifth-longest river in Europe. Flowing from Central Russia to the Sea of Azov in Southern Russia, it is one of Russia's largest rivers and played an important role for traders from the Byzantine Empire.

Its ...

; isolate the oil-producing regions of the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

from the rest of the Soviet Union, and in the north, to encircle Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, and link up with the Finns

Finns or Finnish people ( fi, suomalaiset, ) are a Baltic Finnic ethnic group native to Finland.

Finns are traditionally divided into smaller regional groups that span several countries adjacent to Finland, both those who are native to these ...

. Among other instructions, it also instructed that Army Group Center is to allocate sufficient forces to ensure the destruction of the "Russian 5th Army" and, at the same time, to prepare to repel enemy counterattacks in the central sector of its front. Hitler referred to the Soviet forces in the salient collectively as the "Russian 5th Army". Halder was dismayed, and later described Hitler's plan as "utopian and unacceptable", concluding that the orders were contradictory and Hitler alone must bear the responsibility for inconsistency of his orders and that the OKH can no longer assume responsibility for what was occurring; however, Hitler's instructions still accurately reflected the original intent of the Barbarossa directive of which the OKH was aware all along. Gerhard Engel

Gerhard Engel (13 April 1906 – 9 December 1976) was a German general during World War II who commanded several divisions after serving as an adjutant to Adolf Hitler. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves.

...

, in his diary for 21 August 1941, simply summarized it as, "it was a black day for the Army". Halder offered his own resignation and advised Brauchitsch to do the same. Brauchitsch declined, stating Hitler would not accept the gesture, and nothing would change anyhow. Halder withdrew his offer of resignation.

On 23 August, Halder convened with Bock and Guderian, in Borisov, in Belorussia, and afterwards flew with Guderian to Hitler's headquarters in East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label= Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

. During a meeting between Guderian and Hitler, with neither Halder nor Brauchitsch present, Hitler allowed Guderian to make the case for advancing on to Moscow, and then rejected his argument. Hitler claimed his decision to secure the northern and southern sectors of western Soviet Union were "tasks which stripped the Moscow problem of much of its significance" and was "not a new proposition, but a fact I have clearly and unequivocally stated since the beginning of the operation." Hitler also argued that the situation was even more critical because the opportunity to encircle the Soviet forces in the salient was "an unexpected opportunity, and a reprieve from past failures to trap the Soviet armies in the south." Hitler also declared, "the objections that time will be lost and the offensive on Moscow might be undertaken too late, or that the armoured units might no longer be technically able to fulfil their mission, are not valid." Hitler reiterated that once the flanks of Army Group Center were cleared, especially the salient in the south, then he would allow the army to resume its drive on Moscow; an offensive, he concluded, which "must not fail". Guderian returned to the 2nd Panzer Group and began the southern thrust in an effort to encircle the Soviet forces in the salient.

The bulk of the 2nd Panzer Group and the 2nd Army were detached from Army Group Centre and sent south. Its mission was to encircle the Southwestern Front, commanded by

The bulk of the 2nd Panzer Group and the 2nd Army were detached from Army Group Centre and sent south. Its mission was to encircle the Southwestern Front, commanded by Semyon Budyonny

Semyon Mikhailovich Budyonnyy ( rus, Семён Миха́йлович Будённый, Semyon Mikháylovich Budyonnyy, p=sʲɪˈmʲɵn mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ bʊˈdʲɵnːɨj, a=ru-Simeon Budyonniy.ogg; – 26 October 1973) was a Russian ca ...

, in conjunction with the 1st Panzer Group

The 1st Panzer Army (german: 1. Panzerarmee) was a German tank army that was a large armoured formation of the Wehrmacht during World War II.

When originally formed on 1 March 1940, the predecessor of the 1st Panzer Army was named Panzer Group ...

, of Army Group South, under Paul Ludwig Ewald von Kleist

Paul Ludwig Ewald von Kleist (8 August 1881 – 13 November 1954) was a German field marshal during World War II. Kleist was the commander of Panzer Group Kleist (later 1st Panzer Army), the first operational formation of several Panzer corps in t ...

, which was advancing from a southeasterly direction.

Following the crossing of the Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

river by German forces on 22 August 1941, the city of Kiev came under threat of encirclement. The command of the Southwestern Front appealed to the Stavka

The ''Stavka'' (Russian and Ukrainian: Ставка) is a name of the high command of the armed forces formerly in the Russian Empire, Soviet Union and currently in Ukraine.

In Imperial Russia ''Stavka'' referred to the administrative staff ...

to allow for a withdrawal of forces from Kiev.

September

The Red Army Chief of Staff,Boris Shaposhnikov

, birth_name = Boris Mikhailovitch Shaposhnikov

, birth_date =

, death_date =

, birth_place = Zlatoust, Ufa Governorate Russian Empire

, death_place = Moscow, Soviet Union

, placeofburial = Kremlin Wall Necropolis

, place ...

, wrote a letter to the Southwestern Front on September 17, authorising a withdraw from Kiev, when the encirclement was already completed at Lokhvytsia, in Poltava region.

Battle

The Panzer armies made rapid progress. On 12 September, Ewald von Kleist's 1st Panzer Group, which had by now turned north and crossed the Dnieper river, emerged from its bridgeheads at

The Panzer armies made rapid progress. On 12 September, Ewald von Kleist's 1st Panzer Group, which had by now turned north and crossed the Dnieper river, emerged from its bridgeheads at Cherkassy

Cherkasy ( uk, Черка́си, ) is a city in central Ukraine. Cherkasy is the capital of Cherkasy Oblast (province), as well as the administrative center of Cherkasky Raion (district) within the oblast. The city has a population of

C ...

and Kremenchuk

Kremenchuk (; uk, Кременчу́к, Kremenchuk ) is an industrial city in central Ukraine which stands on the banks of the Dnipro River. The city serves as the administrative center of the Kremenchuk Raion (district) in Poltava Oblast (pr ...

. Continuing north, it cut across the rear of Semyon Budyonny's Southwestern Front. On 16 September, it made contact with Guderian's 2nd Panzer Group, advancing south, at the town of Lokhvitsa, east of Kiev. Budyonny was now trapped and soon relieved by Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

's order of 13 September, and Budyonny was replaced by Semyon Timoshenko

Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko (russian: link=no, Семён Константи́нович Тимоше́нко, ''Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko''; uk, Семе́н Костянти́нович Тимоше́нко, ''Semen Kostiantyno ...

, in command of the Southwestern Direction.

After that, the fate of the encircled Soviet armies was sealed. With no mobile forces or supreme commander left, there was no possibility to effect a breakout. The infantry of the German 17th and 6th Armies, of Army Group South, soon arrived, along with the 2nd Army, also on loan from Army Group Center, and marching behind Guderian's tanks. They systematically began to reduce the pocket

A pocket is a bag- or envelope-like receptacle either fastened to or inserted in an article of clothing to hold small items. Pockets are also attached to luggage, backpacks, and similar items. In older usage, a pocket was a separate small bag ...

, assisted by the two Panzer armies. The encircled Soviet armies at Kiev did not give up easily. A savage battle in which the Soviets were bombarded by artillery, tanks, and aircraft had to be fought before the pocket had finally fallen.

By 19 September, Kiev had fallen, but the encirclement battle continued. After 10 days of heavy fighting, the last remnants of troops east of Kiev surrendered on 26 September. Several Soviet armies, namely the 5th, 37th, and 26th, were now encircled, as well as separate detachments of 38th and 21st armies. The Germans claimed to have captured 600,000 Red Army soldiers (up to 665,000), although these claims have included a large number of civilians suspected of evading capture.

During withdrawal from Kiev, on 20–22 September 1941, at Shumeikove Hai, near Dryukivshchyna, (today in Lokhvytsia Raion

Lokhvytsia Raion ( uk, Ло́хвицький райо́н; translit.: ''Lóchvyc’kyj Rajón'') was a raion (district) in Poltava Oblast in central Ukraine. The raion's administrative center was the city of Lokhvytsia. The raion was abolished ...

) several members of headquarters staff were killed, including Mikhail Kirponos (commander), Mykhailo Burmystenko

Mykhailo Oleksiyovych Burmystenko ( uk, Михайло Олексійович Бурмистенко; 22 November 1902 – 20 September 1941) was a Ukrainian and Soviet politician, who served as the Chairman of the Supreme Soviet Ukrainian SSR fr ...

(a member of military council), and Vasiliy Tupikov (chief of staff). Some 15,000 Soviet troops managed to break through the encirclement.

Aftermath

By virtue of Guderian's southward turn, the Wehrmacht destroyed the entire Southwestern Front east of Kiev during September. It inflicted nearly 700,544 casualties on the Red Army, while Soviet forces west of Moscow conducted many attacks on Army Group Centre. Although most of these attacks failed, the Soviet attacks in the Yelnya Offensive succeeded with the German forces abandoning the town, and resulted in the first major defeat for the Wehrmacht in

By virtue of Guderian's southward turn, the Wehrmacht destroyed the entire Southwestern Front east of Kiev during September. It inflicted nearly 700,544 casualties on the Red Army, while Soviet forces west of Moscow conducted many attacks on Army Group Centre. Although most of these attacks failed, the Soviet attacks in the Yelnya Offensive succeeded with the German forces abandoning the town, and resulted in the first major defeat for the Wehrmacht in Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

. With its southern flank secured, Army Group Center launched Operation Typhoon

The Battle of Moscow was a military campaign that consisted of two periods of strategically significant fighting on a sector of the Eastern Front during World War II. It took place between September 1941 and January 1942. The Soviet defensive ...

, in the direction of Vyazma

Vyazma (russian: Вя́зьма) is a town and the administrative center of Vyazemsky District in Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Vyazma River, about halfway between Smolensk, the administrative center of the oblast, and Mozhaysk. Thr ...

, in October.

Over the objections of Gerd von Rundstedt

Karl Rudolf Gerd von Rundstedt (12 December 1875 – 24 February 1953) was a German field marshal in the '' Heer'' (Army) of Nazi Germany during World War II.

Born into a Prussian family with a long military tradition, Rundstedt entered th ...

, Army Group South was ordered to resume the offensive and overran nearly all of the Crimea and Left-bank Ukraine

Left-bank Ukraine ( uk, Лівобережна Україна, translit=Livoberezhna Ukrayina; russian: Левобережная Украина, translit=Levoberezhnaya Ukraina; pl, Lewobrzeżna Ukraina) is a historic name of the part of Ukrain ...

before reaching the edges of the Donbas

The Donbas or Donbass (, ; uk, Донба́с ; russian: Донба́сс ) is a historical, cultural, and economic region in eastern Ukraine. Parts of the Donbas are controlled by Russian separatist groups as a result of the Russo-Ukrai ...

industrial region. However, after four months of continuous operations, his forces were at the brink of exhaustion, and suffered a major defeat in the Battle of Rostov. Army Group South's infantry fared little better and failed to capture the vital city of Kharkov

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

, before nearly all of its factories, skilled laborers, and equipment were evacuated east of the Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

.

After the occupation of Kiev by German troops, a series of explosions of Soviet radio-mines occurred in the city, as a result of which German soldiers and local civilians were killed.at shvachko.net: retrieved 30 November 2022

Assessment

Immediately after World War II ended, prominent German commanders argued that had operations at Kiev been delayed, and had Operation Typhoon been launched in September, rather than October, the German Army would have reached and captured Moscow before the onset of winter.

Immediately after World War II ended, prominent German commanders argued that had operations at Kiev been delayed, and had Operation Typhoon been launched in September, rather than October, the German Army would have reached and captured Moscow before the onset of winter.

David Glantz

David M. Glantz (born January 11, 1942) is an American military historian known for his books on the Red Army during World War II and as the chief editor of '' The Journal of Slavic Military Studies''.

Born in Port Chester, New York, Glantz re ...

argued that had Operation Typhoon been launched in September, it would have met greater resistance due to Soviet forces not having been weakened by their offensives east of Smolensk

Smolensk ( rus, Смоленск, p=smɐˈlʲensk, a=smolensk_ru.ogg) is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow. First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest ...

. The offensive would have also been launched with an extended right flank. Glantz also claims that regardless of the final position of German troops when winter came, they would have still faced a counteroffensive by the 10 reserve armies raised by the Soviets toward the end of the year, who would also be better equipped by the vast industrial resources in the area of Kiev. Glantz asserts that had Kiev not been taken before the Battle of Moscow

The Battle of Moscow was a military campaign that consisted of two periods of strategically significant fighting on a sector of the Eastern Front during World War II. It took place between September 1941 and January 1942. The Soviet defensive ...

, the entire operation would have ended in a disaster for the Germans.

See also

*Babi Yar

Babi Yar (russian: Ба́бий Яр) or Babyn Yar ( uk, Бабин Яр) is a ravine in the Ukrainian capital Kyiv and a site of massacres carried out by Nazi Germany's forces during its campaign against the Soviet Union in World War II. T ...

* Battle of Uman

*Battle of Białystok–Minsk

The Battle of Białystok–Minsk was a German strategic operation conducted by the Wehrmacht's Army Group Centre under Field Marshal Fedor von Bock during the penetration of the Soviet border region in the opening stage of Operation Barbarossa, ...

* Battle of Kiev (1943)

* Yelnya Offensive

* Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran

References

Sources

* * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kiev, Battle Of (1941) Conflicts in 1941 1941 in Ukraine Battle of Kiev Encirclements in World War II Battles and operations of the Soviet–German War Battles of World War II involving Germany Battles involving the Soviet Union Military history of Kyiv August 1941 events September 1941 events