Battle of Isandlwana on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Isandlwana (alternative spelling: Isandhlwana) on 22 January 1879 was the first major encounter in the

The backbone of the British force under Lord Chelmsford consisted of twelve regular

The backbone of the British force under Lord Chelmsford consisted of twelve regular  The Zulu army, while a product of a warrior culture, was essentially a militia force which could be called out in time of national danger. It had a very limited logistical capacity and could only stay in the field a few weeks before the troops would be obliged to return to their civilian duties. Zulu warriors were armed primarily with ''

The Zulu army, while a product of a warrior culture, was essentially a militia force which could be called out in time of national danger. It had a very limited logistical capacity and could only stay in the field a few weeks before the troops would be obliged to return to their civilian duties. Zulu warriors were armed primarily with '' Pulleine, left in command of a rear position, was an administrator with no experience of front-line command on a campaign. Nevertheless, he commanded a strong force, particularly the six veteran regular infantry companies, which were experienced in colonial warfare. The mounted vedettes, cavalry scouts, patrolling some from camp reported at 7:00 am that groups of Zulus, numbering around 4,000 men, could be seen. Pulleine received further reports during the early morning, each of which noted movements, both large and small, of Zulus. There was speculation among the officers whether these troops were intending to march against Chelmsford's rear or towards the camp itself.Knight (1992, 2002), p. 40

Around 10:30 am,

Pulleine, left in command of a rear position, was an administrator with no experience of front-line command on a campaign. Nevertheless, he commanded a strong force, particularly the six veteran regular infantry companies, which were experienced in colonial warfare. The mounted vedettes, cavalry scouts, patrolling some from camp reported at 7:00 am that groups of Zulus, numbering around 4,000 men, could be seen. Pulleine received further reports during the early morning, each of which noted movements, both large and small, of Zulus. There was speculation among the officers whether these troops were intending to march against Chelmsford's rear or towards the camp itself.Knight (1992, 2002), p. 40

Around 10:30 am,

The Zulu Army was commanded by ''ESA'' (Princes) Ntshingwayo kaMahole Khoza and Mavumengwana kaNdlela Ntuli. The ''inDuna''

The Zulu Army was commanded by ''ESA'' (Princes) Ntshingwayo kaMahole Khoza and Mavumengwana kaNdlela Ntuli. The ''inDuna''  Durnford's men, who had been fighting the longest, began to withdraw and their

Durnford's men, who had been fighting the longest, began to withdraw and their

Once their ammunition had been expended, surviving British soldiers had no choice but to fight on with bayonet and rifle butt. A Zulu account relates the single-handed fight by the guard of Chelmsford's tent, a big Irishman of the 24th who kept the Zulus back with his

Once their ammunition had been expended, surviving British soldiers had no choice but to fight on with bayonet and rifle butt. A Zulu account relates the single-handed fight by the guard of Chelmsford's tent, a big Irishman of the 24th who kept the Zulus back with his

Debate persists as to how and why the British lost the battle. Many arguments focus on possible local tactical occurrences, as opposed to the

Debate persists as to how and why the British lost the battle. Many arguments focus on possible local tactical occurrences, as opposed to the  Though Isandlwana was a disaster for the British, the Zulu victory did not end the war. With the defeat of Chelmsford's central column, the invasion of Zululand collapsed and would have to be restaged. Not only were there heavy manpower casualties to the Main Column, but most of the supplies, ammunition and draught animals were lost. As King Cetshwayo feared, the embarrassment of the defeat would force the policy makers in London, who to this point had not supported the war, to rally to the support of the pro-war contingent in the Natal government and commit whatever resources were needed to defeat the Zulus. Despite local numerical superiority, the Zulus did not have the manpower, technological resources, or logistical capacity to match the British in another, more extended, campaign.

The Zulus may have missed an opportunity to exploit their victory and possibly win the war that day on their own territory. The reconnaissance force under Chelmsford was more vulnerable to being defeated by an attack than the camp. It was strung out and somewhat scattered, it had marched with limited rations and ammunition it could not now replace, and it was panicky and demoralized by the defeat at Isandlwana.

Near the end of the battle, about 4,000 Zulu warriors of the unengaged reserve Undi impi, after cutting off the retreat of the survivors to the Buffalo River southwest of Isandlwana, crossed the river and attacked the fortified mission station at

Though Isandlwana was a disaster for the British, the Zulu victory did not end the war. With the defeat of Chelmsford's central column, the invasion of Zululand collapsed and would have to be restaged. Not only were there heavy manpower casualties to the Main Column, but most of the supplies, ammunition and draught animals were lost. As King Cetshwayo feared, the embarrassment of the defeat would force the policy makers in London, who to this point had not supported the war, to rally to the support of the pro-war contingent in the Natal government and commit whatever resources were needed to defeat the Zulus. Despite local numerical superiority, the Zulus did not have the manpower, technological resources, or logistical capacity to match the British in another, more extended, campaign.

The Zulus may have missed an opportunity to exploit their victory and possibly win the war that day on their own territory. The reconnaissance force under Chelmsford was more vulnerable to being defeated by an attack than the camp. It was strung out and somewhat scattered, it had marched with limited rations and ammunition it could not now replace, and it was panicky and demoralized by the defeat at Isandlwana.

Near the end of the battle, about 4,000 Zulu warriors of the unengaged reserve Undi impi, after cutting off the retreat of the survivors to the Buffalo River southwest of Isandlwana, crossed the river and attacked the fortified mission station at

Zulu: The True Story By Dr. Saul David

Secrets of the Dead – Day of the Zulu

Travellers Impressions

* The Battle of Isandlwana 22 January 1879, Ian Knight vide

* Forgotten Heroes Zulu & Basuto Wars, Roy Dutton,

Battle_Of Conflicts_in_1879

1879_in_the_Zulu_Kingdom.html" ;"title="Conflicts in 1879">Battle Of Conflicts in 1879

1879 in the Zulu Kingdom">Conflicts in 1879">Battle Of Conflicts in 1879

1879 in the Zulu Kingdom Battles of the Anglo-Zulu War Military history of South Africa Battles involving the United Kingdom History of KwaZulu-Natal January 1879 events Battles involving the Zulu

Anglo-Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Following the passing of the British North America Act of 1867 forming a federation in Canada, Lord Carnarvon thought that a similar political effort, cou ...

between the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

and the Zulu Kingdom

The Zulu Kingdom (, ), sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire or the Kingdom of Zululand, was a monarchy in Southern Africa. During the 1810s, Shaka established a modern standing army that consolidated rival clans and built a large followin ...

. Eleven days after the British commenced their invasion of Zululand in Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the Congo and Tanzania. The physical location is the large part of Africa to the south of the extensive Congo River basin. Southern Africa is home to a number o ...

, a Zulu force of some 20,000 warriors attacked a portion of the British main column consisting of about 1,800 British, colonial and native troops with approximately 350 civilians. The Zulus were equipped mainly with the traditional assegai

An assegai or assagai (Arabic ''az-zaġāyah'', Berber ''zaġāya'' "spear", Old French ''azagaie'', Spanish ''azagaya'', Italian ''zagaglia'', Middle English ''lancegay'') is a pole weapon used for throwing, usually a light spear or javelin ...

iron spears and cow-hide shields, but also had a number of musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually di ...

s and antiquated rifle

A rifle is a long-barreled firearm designed for accurate shooting, with a barrel that has a helical pattern of grooves ( rifling) cut into the bore wall. In keeping with their focus on accuracy, rifles are typically designed to be held with ...

s.Smith-Dorrien, Chapter 1B "It was a marvellous sight, line upon line of men in slightly extended order, one behind the other, firing as they came along, for ''a few of them had firearms'', bearing all before them." eyewitness account, emphasis added

The British and colonial troops were armed with the modern Martini–Henry

The Martini–Henry is a breech-loading single-shot rifle with a lever action that was used by the British Army. It first entered service in 1871, eventually replacing the Snider–Enfield, a muzzle-loader converted to the cartridge system ...

breechloading

A breechloader is a firearm in which the user loads the ammunition ( cartridge or shell) via the rear (breech) end of its barrel, as opposed to a muzzleloader, which loads ammunition via the front ( muzzle).

Modern firearms are generally bre ...

rifle

A rifle is a long-barreled firearm designed for accurate shooting, with a barrel that has a helical pattern of grooves ( rifling) cut into the bore wall. In keeping with their focus on accuracy, rifles are typically designed to be held with ...

and two 7-pounder mountain guns deployed as field guns, as well as a Hale rocket battery. The Zulus had a vast disadvantage in weapons technology,Doyle, p. 118: "It was here ... the British Army suffered its worst ever defeat at the hands of a ''technologically inferior indigenous force''." (emphasis added) but they greatly outnumbered the British and ultimately overwhelmed them, killing over 1,300 troops, including all those out on the forward firing line. The Zulu army suffered anywhere from 1,000 to 3,000 killed.

The battle was a decisive victory for the Zulus and caused the defeat of the first British invasion of Zululand. The British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

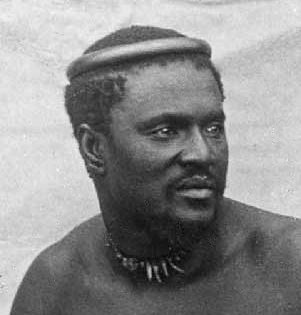

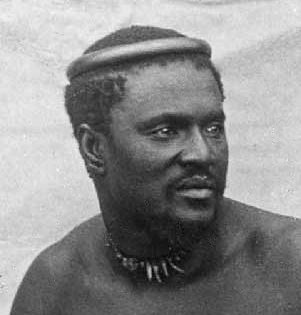

had suffered its worst defeat against an indigenous foe equipped with vastly inferior military technology. Isandlwana resulted in the British taking a much more aggressive approach in the Anglo–Zulu War, leading to a heavily reinforced second invasion, and in the destruction of King Cetshwayo

King Cetshwayo kaMpande (; ; 1826 – 8 February 1884) was the king of the Zulu Kingdom from 1873 to 1879 and its Commander in Chief during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. His name has been transliterated as Cetawayo, Cetewayo, Cetywajo and Ketchw ...

's hopes of a negotiated peace.

Background

Following the scheme by which Lord Carnarvon had brought about theConfederation of Canada

Canadian Confederation (french: Confédération canadienne, link=no) was the process by which three British North American provinces, the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, were united into one federation called the Dominion of ...

through the 1867 British North America Act

The ''Constitution Act, 1867'' (french: Loi constitutionnelle de 1867),''The Constitution Act, 1867'', 30 & 31 Victoria (U.K.), c. 3, http://canlii.ca/t/ldsw retrieved on 2019-03-14. originally enacted as the ''British North America Act, 186 ...

, it was thought that a similar plan might succeed in South Africa and in 1877 Sir Henry Bartle Frere

Sir Henry Bartle Edward Frere, 1st Baronet, (29 March 1815 – 29 May 1884) was a Welsh British colonial administrator. He had a successful career in India, rising to become Governor of Bombay (1862–1867). However, as High Commissioner for ...

was appointed as High Commissioner for Southern Africa

The British office of high commissioner for Southern Africa was responsible for governing British possessions in Southern Africa, latterly the protectorates of Basutoland (now Lesotho), the Bechuanaland Protectorate (now Botswana) and Swaziland ...

to instigate the scheme. Some of the obstacles to such a plan were the presence of the independent states of the South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when i ...

and the Kingdom of Zululand, both of which the British Empire would attempt to overcome by force of arms.

Bartle Frere, on his own initiative, without the approval of the British government and with the intent of instigating a war with the Zulu, had presented an ultimatum to the Zulu king Cetshwayo on 11 December 1878 with which the Zulu king could not possibly comply. When the ultimatum expired a month later, Bartle Frere ordered Lord Chelmsford

Viscount Chelmsford, of Chelmsford in the County of Essex, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1921 for Frederic Thesiger, 3rd Baron Chelmsford, the former Viceroy of India. The title of Baron Chelmsford, of Chelms ...

to proceed with an invasion of Zululand, for which plans had already been made.

Prelude

Lord Chelmsford

Viscount Chelmsford, of Chelmsford in the County of Essex, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1921 for Frederic Thesiger, 3rd Baron Chelmsford, the former Viceroy of India. The title of Baron Chelmsford, of Chelms ...

, the Commander-in-Chief of British forces during the war, initially planned a five-pronged invasion of Zululand consisting of over 16,500 troops in five columns and designed to encircle the Zulu army and force it to fight as he was concerned that the Zulus would avoid battle, slip around the British and over the Tugela, and strike at Natal. Lord Chelmsford settled on three invading columns, with the main centre column now consisting of some 7,800 men – comprising the previously called No. 3 Column, commanded by the Colonel of the 24th Richard Thomas Glyn

Lt Gen Richard Thomas Glyn (23 December 1831 – 21 November 1900) was a British Army officer. He joined the 82nd Regiment of Foot (Prince of Wales's Volunteers) by purchasing an ensign's commission in 1850. Glyn served with the regiment in the ...

, and Colonel Anthony Durnford

Lieutenant-Colonel Anthony William Durnford (24 May 1830 – 22 January 1879) was an Irish career British Army officer of the Royal Engineers who served in the Anglo-Zulu War. Breveted colonel, Durnford is mainly known for his defeat by the Z ...

's No. 2 Column, under his direct command. He moved his troops from Pietermaritzburg

Pietermaritzburg (; Zulu: umGungundlovu) is the capital and second-largest city in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. It was founded in 1838 and is currently governed by the Msunduzi Local Municipality. Its Zulu name umGungundlovu ...

to a forward camp at Helpmekaar, past Greytown. On 9 January 1879 they moved to Rorke's Drift

The Battle of Rorke's Drift (1879), also known as the Defence of Rorke's Drift, was an engagement in the Anglo-Zulu War. The successful British defence of the mission station of Rorke's Drift, under the command of Lieutenants John Chard of the ...

, and early on 11 January commenced crossing the Buffalo River into Zululand.

The backbone of the British force under Lord Chelmsford consisted of twelve regular

The backbone of the British force under Lord Chelmsford consisted of twelve regular infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specific, declared go ...

: six each of the 1st and 2nd Battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions ...

s, 24th Regiment of Foot

Fourth or the fourth may refer to:

* the ordinal form of the number 4

* ''Fourth'' (album), by Soft Machine, 1971

* Fourth (angle), an ancient astronomical subdivision

* Fourth (music), a musical interval

* ''The Fourth'' (1972 film), a Sovie ...

(2nd Warwickshire Regiment), which were hardened and reliable troops. In addition, there were approximately 2,500 local African auxiliaries of the Natal Native Contingent

The Natal Native Contingent was a large force of auxiliary soldiers in British South Africa, forming a substantial portion of the defence forces of the British colony of Natal. The Contingent saw action during the 1879 Anglo-Zulu War. The Natal ...

, many of whom were exiled or refugee Zulu. They were led by European officers, but were considered generally of poor quality by the British as they were prohibited from using their traditional fighting technique and inadequately trained in the European method as well as being indifferently armed. Also, there were some irregular colonial cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

units, and a detachment of artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

consisting of six field gun

A field gun is a field artillery piece. Originally the term referred to smaller guns that could accompany a field army on the march, that when in combat could be moved about the battlefield in response to changing circumstances ( field artill ...

s and several Congreve rocket

The Congreve rocket was a type of rocket artillery designed by British inventor Sir William Congreve in 1808.

The design was based upon the rockets deployed by the Kingdom of Mysore against the East India Company during the Second, Third, ...

s. Adding on wagon drivers, camp followers and servants, there were around 4,700 men in the No. 3 Column, and around 3,100 men in the No. 2 Column that comprised the main centre column. Colonel Anthony Durnford took charge of No. 2 Column with orders to stay on the defensive near the Middle Drift of the Thukela River. Because of the urgency required to accomplish their scheme, Bartle Frere and Chelmsford began the invasion during the rainy season. This had the consequence of slowing the British advance to a crawl.

The Zulu army, while a product of a warrior culture, was essentially a militia force which could be called out in time of national danger. It had a very limited logistical capacity and could only stay in the field a few weeks before the troops would be obliged to return to their civilian duties. Zulu warriors were armed primarily with ''

The Zulu army, while a product of a warrior culture, was essentially a militia force which could be called out in time of national danger. It had a very limited logistical capacity and could only stay in the field a few weeks before the troops would be obliged to return to their civilian duties. Zulu warriors were armed primarily with ''assegai

An assegai or assagai (Arabic ''az-zaġāyah'', Berber ''zaġāya'' "spear", Old French ''azagaie'', Spanish ''azagaya'', Italian ''zagaglia'', Middle English ''lancegay'') is a pole weapon used for throwing, usually a light spear or javelin ...

'' thrusting spears, known in Zulu as '' iklwa'', knobkierrie

A knobkerrie, also spelled knobkerry, knobkierie, and knopkierie (Afrikaans), is a form of wooden club, used mainly in Southern and Eastern Africa. Typically they have a large knob at one end and can be used for throwing at animals in hunting or ...

clubs, some throwing spears and shields made of cowhide. The Zulu warrior, his regiment and the army drilled in the personal and tactical use and coordination of this weapons system. Some Zulus also had old muskets and antiquated rifles stockpiled, a relatively few of which were carried by Zulu impi

is a Zulu word meaning war or combat and by association any body of men gathered for war, for example is a term denoting an army. were formed from regiments () from (large militarised homesteads). In English is often used to refer to a ...

. However, their marksmanship was very poor, quality and supply of powder and shot dreadful, maintenance non-existent and attitude towards firearms summed up in the observation that: "The generality of Zulu warriors, however, would not have firearms – the arms of a coward, as they said, for they enable the poltroon

Poltroon was an event

Event may refer to:

Gatherings of people

* Ceremony, an event of ritual significance, performed on a special occasion

* Convention (meeting), a gathering of individuals engaged in some common interest

* Event man ...

to kill the brave without awaiting his attack." The British had timed the invasion to coincide with the harvest, intending to catch the Zulu warrior-farmers dispersed. Fortunately for Cetshwayo, the Zulu army had already begun to assemble at Ulundi, as it did every year for the ''First Fruits

First Fruits is a religious offering of the first agricultural produce of the harvest. In classical Greek, Roman, and Hebrew religions, the first fruits were given to priests as an offering to deity. In Christian faiths, the tithe is similar ...

'' ceremony when all warriors were duty-bound to report to their regimental barracks near Ulundi.Colenso, p. 294

Cetshwayo sent the 24,000 strong main Zulu impi from near present-day Ulundi, on 17 January, across the White Umfolozi River

The White Umfolozi River originates just west of Vryheid, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa and has a confluence with the Black Umfolozi River at to form the Umfolozi River, which flows eastward towards the Indian Ocean.

See also

* List of rivers o ...

with the following command to his warriors: "March slowly, attack at dawn and eat up the red soldiers."

On 18 January, some 4,000 warriors, under the leadership of Mavumengwana kaNdlela Ntuli, were detached from the main body to meet with Dabulamanzi kaMpande

Dabulamanzi kaMpande (1839 – September 22, 1886) was a Zulu commander for the Zulu kingdom in the Anglo-Zulu War. He is most noted for having commanded the Zulus at the Battle of Rorke's Drift. He was a half-brother of the Zulu king Cetsh ...

and attack Charles Pearson

Charles Pearson (4 October 1793 – 14 September 1862) was a British lawyer and politician. He was solicitor to the City of London, a reforming campaigner, and – briefly – Member of Parliament for Lambeth. He campaigned against corruption ...

's No. 1 Column near Eshowe

Eshowe is the oldest town of European settlement in Zululand, historically also known as Eziqwaqweni, Ekowe or kwaMondi. Eshowe's name is said to be inspired by the sound of wind blowing through the more than 4 km² of the indigenous Dlinza ...

. The remaining 20,000 Zulus camped at the isiPhezi ikhanda. The next day, the main force arrived and camped near Babanango Mountain, then moved the next day to a camp near Siphezi Mountain. Finally, on 21 January they moved into the Ngwebeni Valley, where they remained concealed, planning to attack the British on 23 January, but they were discovered by a scouting party on 22 January. Under the command of Ntshigwayo kaMahole the Zulu army had reached its position in easy stages. It marched in two columns within sight of each other, but a few miles apart to prevent a surprise attack. They were preceded by a screening force of mounted scouts supported by parties of warriors 200–400 strong tasked with preventing the main columns from being sighted. The speed of the Zulu advance compared to the British was marked. The Zulu impi had advanced over in five days, while Chelmsford had only advanced slightly over in 10 days.

The British under Chelmsford pitched camp at Isandlwana

Isandlwana () (older spelling ''Isandhlwana'', also sometimes seen as ''Isandula'') is an isolated hill in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. It is located north by northwest of Durban. The name is said to mean abomasum, the second st ...

on 20 January, but did not follow standing orders to entrench. No laager

A wagon fort, wagon fortress, or corral, often referred to as circling the wagons, is a temporary fortification made of wagons arranged into a rectangle, circle, or other shape and possibly joined with each other to produce an improvised milita ...

(circling of the wagons) was formed. Chelmsford did not see the need for one, stating, "It would take a week to make." But the chief reason for the failure to take defensive precautions appears to have been that the British command severely underestimated the Zulus' capabilities. The experience of numerous colonial wars fought in Africa was that the massed firepower of relatively small bodies of professional European troops, armed with modern firearms and artillery and supplemented by local allies and levies, would march out to meet the natives whose poorly equipped armies would put up a fight but in the end would succumb. Chelmsford believed that a force of over 4,000, including 2,000 British infantry armed with Martini–Henry

The Martini–Henry is a breech-loading single-shot rifle with a lever action that was used by the British Army. It first entered service in 1871, eventually replacing the Snider–Enfield, a muzzle-loader converted to the cartridge system ...

rifle

A rifle is a long-barreled firearm designed for accurate shooting, with a barrel that has a helical pattern of grooves ( rifling) cut into the bore wall. In keeping with their focus on accuracy, rifles are typically designed to be held with ...

s, as well as artillery, had more than sufficient firepower to overwhelm any attack by Zulus armed only with spears, cowhide shields and a few firearms such as Brown Bess musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually di ...

s. Indeed, with a British force of this size, it was the logistical arrangements which occupied Chelmsford's thoughts. Rather than any fear that the camp might be attacked, his main concern was managing the huge number of wagons and oxen required to support his forward advance.

Once he had established the camp at Isandlwana, Chelmsford sent out two battalions of the Natal Native Contingent to scout ahead. They skirmished with elements of a Zulu force which he believed to be the vanguard of the main enemy army. Such was his confidence in British military training and firepower that he divided his force, departing the camp at dawn on January 22 with approximately 2,800 soldiers—including half of the British infantry contingent, together with around 600 auxiliaries—to find the main Zulu force with the intention of bringing them to battle so as to achieve a decisive victory, and leaving the remaining 1,300 men of the No. 3 Column to guard the camp. It never occurred to him that the Zulus he saw were diverting him from their main force.

Chelmsford left behind approximately 600 British red coat line infantry

Line infantry was the type of infantry that composed the basis of European land armies from the late 17th century to the mid-19th century. Maurice of Nassau and Gustavus Adolphus are generally regarded as its pioneers, while Turenne and Mon ...

– five companies, around 90 fighting men in each, of the 1st Battalion and one stronger company of around 150 men from the 2nd Battalion of the 24th Regiment of Foot

Fourth or the fourth may refer to:

* the ordinal form of the number 4

* ''Fourth'' (album), by Soft Machine, 1971

* Fourth (angle), an ancient astronomical subdivision

* Fourth (music), a musical interval

* ''The Fourth'' (1972 film), a Sovie ...

to guard the camp, under the command of Brevet Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

Henry Pulleine

Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Burmester Pulleine (12 December 1838 – 22 January 1879) was an administrator and commander in the British Army in the Cape Frontier and Anglo-Zulu Wars. He is most notable as a commander of British forces at the disas ...

. Pulleine's orders were to defend the camp and wait for further instructions to support the general as and when called upon. Pulleine also had around 700 men composed of the Natal Native Contingent

The Natal Native Contingent was a large force of auxiliary soldiers in British South Africa, forming a substantial portion of the defence forces of the British colony of Natal. The Contingent saw action during the 1879 Anglo-Zulu War. The Natal ...

, local mounted irregulars, and other units. He also had two artillery pieces, with around 70 men of the Royal Artillery. In total, over 1,300 men and two artillery guns of the No. 3 Column were left to defend the camp excluding civilian auxiliaries.

Pulleine, left in command of a rear position, was an administrator with no experience of front-line command on a campaign. Nevertheless, he commanded a strong force, particularly the six veteran regular infantry companies, which were experienced in colonial warfare. The mounted vedettes, cavalry scouts, patrolling some from camp reported at 7:00 am that groups of Zulus, numbering around 4,000 men, could be seen. Pulleine received further reports during the early morning, each of which noted movements, both large and small, of Zulus. There was speculation among the officers whether these troops were intending to march against Chelmsford's rear or towards the camp itself.Knight (1992, 2002), p. 40

Around 10:30 am,

Pulleine, left in command of a rear position, was an administrator with no experience of front-line command on a campaign. Nevertheless, he commanded a strong force, particularly the six veteran regular infantry companies, which were experienced in colonial warfare. The mounted vedettes, cavalry scouts, patrolling some from camp reported at 7:00 am that groups of Zulus, numbering around 4,000 men, could be seen. Pulleine received further reports during the early morning, each of which noted movements, both large and small, of Zulus. There was speculation among the officers whether these troops were intending to march against Chelmsford's rear or towards the camp itself.Knight (1992, 2002), p. 40

Around 10:30 am, Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

Anthony Durnford

Lieutenant-Colonel Anthony William Durnford (24 May 1830 – 22 January 1879) was an Irish career British Army officer of the Royal Engineers who served in the Anglo-Zulu War. Breveted colonel, Durnford is mainly known for his defeat by the Z ...

, whose left arm was paralyzed from wounds sustained at Bushman's River Pass during the pursuit of Chief Langalibalele

Langalibalele ( isiHlubi: meaning 'The scorching sun', also known as Mthethwa, Mdingi (c 1814 – 1889), was king of the amaHlubi, a Bantu tribe in what is the modern-day province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

He was born on the eve of the a ...

, arrived from Rorke's Drift

The Battle of Rorke's Drift (1879), also known as the Defence of Rorke's Drift, was an engagement in the Anglo-Zulu War. The successful British defence of the mission station of Rorke's Drift, under the command of Lieutenants John Chard of the ...

with 500 men of the Natal Native Contingent

The Natal Native Contingent was a large force of auxiliary soldiers in British South Africa, forming a substantial portion of the defence forces of the British colony of Natal. The Contingent saw action during the 1879 Anglo-Zulu War. The Natal ...

and a rocket battery of the No. 2 Column to reinforce the camp at Isandlwana. This brought the issue of command to the fore because Durnford was senior and by tradition should have assumed command. However, he did not over-rule Pulleine's dispositions and after lunch he quickly decided to take the initiative and move forward to engage a Zulu force which Pulleine and Durnford judged to be moving against Chelmsford's rear. Durnford asked for a company of the 24th, but Pulleine was reluctant to agree since his orders had been specifically to defend the camp.

Chelmsford had underestimated the disciplined, well-led, well-motivated and confident Zulus. The failure to secure an effective defensive position, the poor intelligence on the location of the main Zulu army, Chelmsford's decision to split his force in half, and the Zulus' tactical exploitation of the terrain and the weaknesses in the British formation, all combined to prove catastrophic for the troops at Isandlwana. In contrast, the Zulus responded to the unexpected discovery of their camp with an immediate and spontaneous advance. Even though the indunas lost control over the advance, the warriors' training allowed the Zulu troops to form their standard attack formation on the run, with their battle line deployed in reverse of its intended order.

Battle

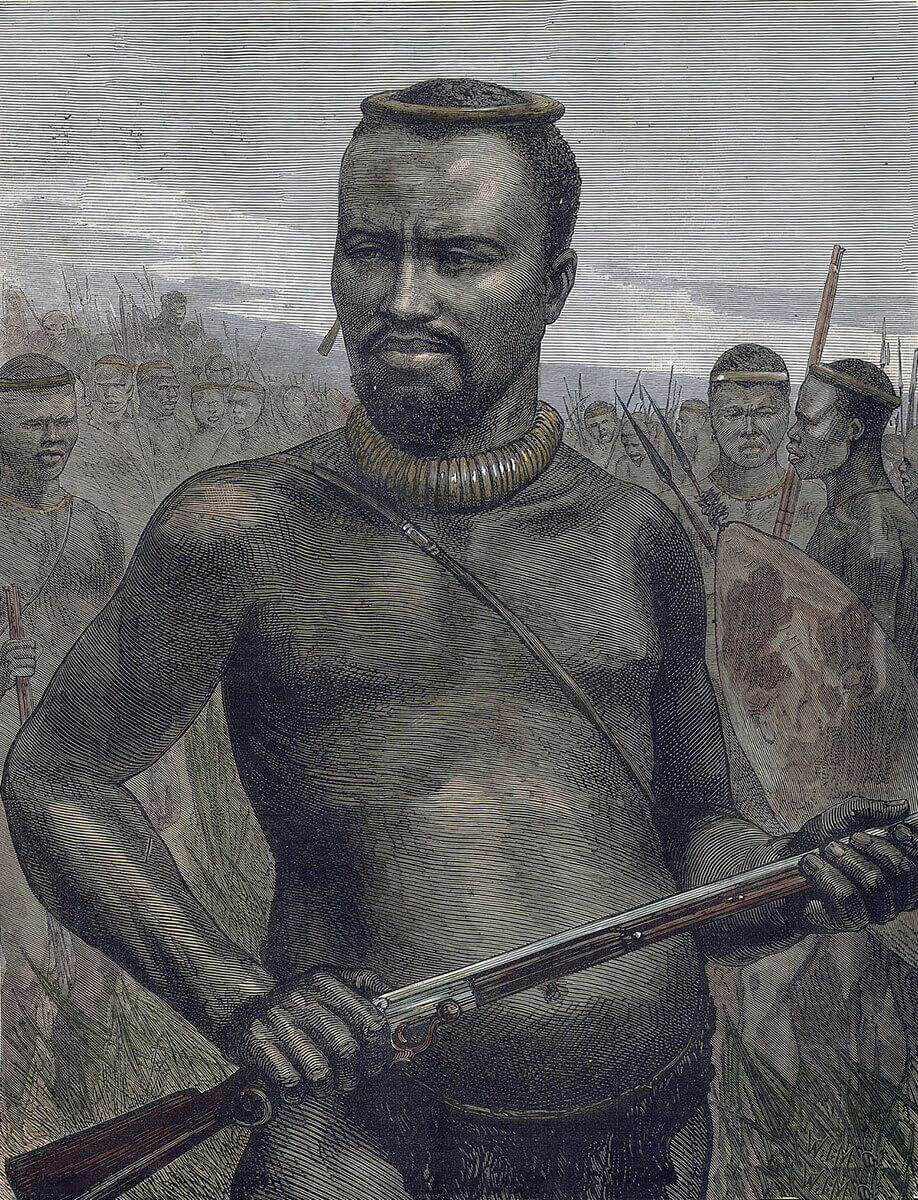

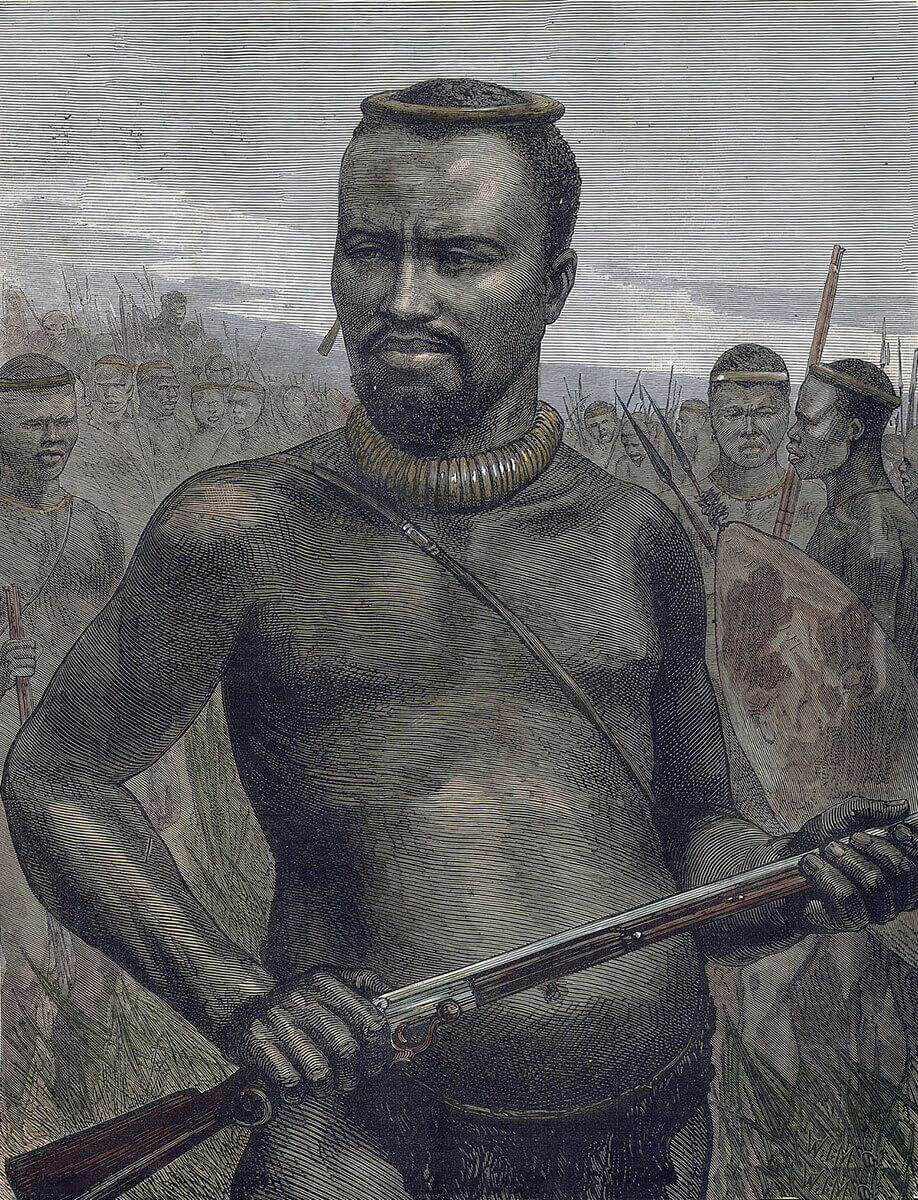

The Zulu Army was commanded by ''ESA'' (Princes) Ntshingwayo kaMahole Khoza and Mavumengwana kaNdlela Ntuli. The ''inDuna''

The Zulu Army was commanded by ''ESA'' (Princes) Ntshingwayo kaMahole Khoza and Mavumengwana kaNdlela Ntuli. The ''inDuna'' Dabulamanzi kaMpande

Dabulamanzi kaMpande (1839 – September 22, 1886) was a Zulu commander for the Zulu kingdom in the Anglo-Zulu War. He is most noted for having commanded the Zulus at the Battle of Rorke's Drift. He was a half-brother of the Zulu king Cetsh ...

, half brother of Cetshwayo, commanded the Undi Corps after Zibhebhu kaMaphitha

Zibhebhu kaMaphitha Zulu (1841–1904) (also called Usibepu/Ziphewu) was a Zulu chief. After the defeat of the Zulu Kingdom by the British, he attempted to create his own independent kingdom. From 1883 to 1884, he fought the Zulu king Cetshwayo, i ...

, the regular ''inkhosi'', or commander, was wounded.

While Chelmsford was in the field seeking them, the entire Zulu army had outmanoeuvred him, moving behind his force with the intention of attacking the British Army on the 23rd. Pulleine had received reports of large forces of Zulus throughout the morning of the 22nd from 8:00am on. Vedettes had observed Zulus on the hills to the left front, and Lt. Chard, while he was at the camp, observed a large force of several thousand Zulu moving to the British left around the hill of Isandlwana. Pulleine sent word to Chelmsford, which was received by the General between 9:00am and 10:00am. The main Zulu force was discovered at around 11:00am by men of Lt. Charles Raw's troop of scouts, who chased a number of Zulus into a valley, only then seeing most of the 20,000 men of the main enemy force sitting in total quiet. This valley has generally been thought to be the Ngwebeni some from the British camp but may have been closer in the area of the spurs of Nqutu hill. Having been discovered, the Zulu force leapt to the offensive. Raw's men began a fighting retreat back to the camp and a messenger was sent to warn Pulleine.

The Zulu attack then developed into a pitched battle

A pitched battle or set-piece battle is a battle in which opposing forces each anticipate the setting of the battle, and each chooses to commit to it. Either side may have the option to disengage before the battle starts or shortly thereafter. A ...

with the traditional horns and chest of the buffalo, with the aim of encircling the British position. From Pulleine's vantage point in the camp, at first only the right horn and then the chest (centre) of the attack seemed to be developing. Pulleine sent out first one, then all six companies of the 24th Foot into an extended firing line, with the aim of meeting the Zulu attack head-on and checking it with firepower. Durnford's men, upon meeting elements of the Zulu centre, had retreated to a donga, a dried-out watercourse, on the British right flank where they formed a defensive line. The rocket battery under Durnford's command, which was not mounted and dropped behind the rest of the force, was isolated and overrun very early in the engagement. The two battalions of native troops were in Durnford's line. While all the officers and NCOs

A non-commissioned officer (NCO) is a military officer who has not pursued a commission. Non-commissioned officers usually earn their position of authority by promotion through the enlisted ranks. (Non-officers, which includes most or all enli ...

carried rifles, only one in 10 in the ranks had a firearm, and those few weapons were muzzle-loading muskets with limited ammunition.Smith-Dorrien, Chapter 1B Many of the native troops began to leave the battlefield at this point.

Pulleine only made one change to the original disposition after about 20 minutes of firing, bringing in the companies in the firing line slightly closer to the camp. For an hour or so until after noon, the disciplined British volleys pinned down the Zulu centre, inflicting many casualties and causing the advance to stall. Indeed, morale remained high within the British line. The Martini–Henry

The Martini–Henry is a breech-loading single-shot rifle with a lever action that was used by the British Army. It first entered service in 1871, eventually replacing the Snider–Enfield, a muzzle-loader converted to the cartridge system ...

rifle was a powerful weapon and the men were experienced. Additionally, the shell fire of the Royal Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as "The Gunners", is one of two regiments that make up the artillery arm of the British Army. The Royal Regiment of Artillery comprises t ...

forced some Zulu regiments to take cover behind the reverse slope of a hill. Nevertheless, the left horn of the Zulu advance was moving to outflank and envelop the British right.

Durnford's men, who had been fighting the longest, began to withdraw and their

Durnford's men, who had been fighting the longest, began to withdraw and their rate of fire

Rate of fire is the frequency at which a specific weapon can fire or launch its projectiles. This can be influenced by several factors, including operator training level, mechanical limitations, ammunition availability, and weapon condition. In m ...

diminished. Durnford's withdrawal exposed the right flank of the British regulars, which, with the general threat of the Zulu encirclement, caused Pulleine to order a withdrawal back to the camp. The regulars' retreat was performed with order and discipline and the men of the 24th conducted a fighting withdrawal into the camp. Durnford's retreat, however, exposed the flank of G Company, 2nd/24th, which was overrun relatively quickly.

An officer in advance of Chelmsford's force gave this eyewitness account of the final stage of the battle at about 3:00 pm:

Nearly the same moment is described in a Zulu warrior's account.

The local time of the solar eclipse on that day is calculated as 2:30 pm.

The presence of large numbers of bodies grouped together suggests the resistance was more protracted than originally thought, and a number of desperate last stand

A last stand is a military situation in which a body of troops holds a defensive position in the face of overwhelming and virtually insurmountable odds. Troops may make a last stand due to a sense of duty; because they are defending a tactic ...

s were made. Evidence shows that many of the bodies, today marked by cairn

A cairn is a man-made pile (or stack) of stones raised for a purpose, usually as a marker or as a burial mound. The word ''cairn'' comes from the gd, càrn (plural ).

Cairns have been and are used for a broad variety of purposes. In prehi ...

s, were found in several large groups around the camp – including one stand of around 150 men. A Zulu account describes a group of the 24th forming a square on the neck of Isandlwana. Colonial cavalry, the NMP and the carabiniers, who could easily have fled as they had horses, died around Durnford in his last stand, while nearby their horses were found dead on their picket rope.Lock, p. 219. What is clear is that the slaughter was complete in the area around the camp and back to Natal along the Fugitive's Drift. The fighting had been hand-to-hand combat

Hand-to-hand combat (sometimes abbreviated as HTH or H2H) is a physical confrontation between two or more persons at short range (grappling distance or within the physical reach of a handheld weapon) that does not involve the use of weapons.Hun ...

and no quarter

The phrase no quarter was generally used during military conflict to imply combatants would not be taken prisoner, but killed.

According to some modern American dictionaries, a person who is given no quarter is "not treated kindly" or "treated ...

was given to the British regulars. The Zulus had been commanded to ignore the civilians in black coats and this meant that some officers, whose patrol dress was dark blue and black at the time, were spared and escaped.

Once their ammunition had been expended, surviving British soldiers had no choice but to fight on with bayonet and rifle butt. A Zulu account relates the single-handed fight by the guard of Chelmsford's tent, a big Irishman of the 24th who kept the Zulus back with his

Once their ammunition had been expended, surviving British soldiers had no choice but to fight on with bayonet and rifle butt. A Zulu account relates the single-handed fight by the guard of Chelmsford's tent, a big Irishman of the 24th who kept the Zulus back with his bayonet

A bayonet (from French ) is a knife, dagger, sword, or spike-shaped weapon designed to fit on the end of the muzzle of a rifle, musket or similar firearm, allowing it to be used as a spear-like weapon.Brayley, Martin, ''Bayonets: An Illustr ...

until he was speared and the general's Union flag captured. Both the colours of the 2nd 24th were lost, while the Queen's colour of the 1st 24th was carried off the field by Lieutenant Melvill on horseback but lost when he crossed the river, despite Lieutenant Coghill having come to his aid. Both Melvill and Coghill were killed after crossing the river, and received posthumous Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previousl ...

es in 1907 as the legend of their gallantry grew, and, after twenty-seven years of steady campaigning by the late Mrs. Melvill (who had died in 1906), on the strength of Queen Victoria being quoted as saying that 'if they had survived they would have been awarded the Victoria Cross'. Garnet Wolseley

Field Marshal Garnet Joseph Wolseley, 1st Viscount Wolseley, (4 June 183325 March 1913), was an Anglo-Irish officer in the British Army. He became one of the most influential and admired British generals after a series of successes in Canada, W ...

, who replaced Chelmsford, felt otherwise at the time and stated, "I don't like the idea of officers escaping on horseback when their men on foot are being killed."

Of the 1,800-plus force of British troops and African auxiliaries, over 1,300 were killed, most of them Europeans, including field commanders Pulleine and Durnford. Only five Imperial officers survived (including Lieutenant Henry Curling and Lieutenant Horace Smith-Dorrien

General Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien, (26 May 1858 – 12 August 1930) was a British Army General. One of the few British survivors of the Battle of Isandlwana as a young officer, he also distinguished himself in the Second Boer War.

Smi ...

), and the 52 officers lost was the most lost by any British battalion up to that time. Amongst those killed was Surgeon Major Peter Shepherd, a first-aid pioneer. The Natal Native Contingent lost some 400 men, and there were 240 lost from the group of 249 amaChunu African auxiliaries. Perhaps the last to die was Gabangaye, the portly chief of the amaChunu Natal Native Contingent, who was given over to be killed by the ''udibi'' (porter or carrier) boys. The captured Natal Native Contingent soldiers were regarded as traitors by the Zulu and executed.

There was no casualty count of the Zulu losses by the British such as made in many of the other battles since they abandoned the field. Nor was there any count by the Zulu. Modern historians have rejected and reduced the older unfounded estimates. Historians Lock and Quantrill estimate the Zulu casualties as "... perhaps between 1,500 and 2,000 dead. Historian Ian Knight stated: "Zulu casualties were almost as heavy. Although it is impossible to say with certainty, at least 1,000 were killed outright in the assault..."

Some 1,000 Martini-Henry rifles, the two field artillery guns, 400,000 rounds of ammunition, three colours, most of the 2,000 draft animals and 130 wagons, provisions such as tinned food, biscuits, beer, overcoats, tents and other supplies, were taken by the Zulu or left abandoned on the field. Of the survivors, most were from the auxiliaries. The two field artillery guns which were taken to Ulundi as trophies, were later found abandoned by a British patrol after the Battle of Ulundi.

Order of battle

The following order of battle was arrayed on the day.British forces

No. 2 Column

Commanding Officer: Brevet Colonel Anthony Durnford, RE * Staff – 2 officers, 1 NCO * 11th/7th Brigade, Royal Artillery – 1 officer, 9 NCOs and men with a rocket battery (3 rocket troughs) * Natal Native Horse (5 troops) – 5 officers, c. 259 NCOs and men * 1st/1st Natal Native Contingent (2 companies) – 6 officers, c. 240 NCOs and men * 2nd/1st Natal Native Contingent – 1 NCONo. 3 Column

Commanding Officer: Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Pulleine, 1st/24th Foot * Staff – 6 officers, 14 NCOs and men * N/5th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery – 2 officers, 70 NCOs and men with two 7-pounder (3-inch) mountain guns deployed as field guns * 5th Field Company, Royal Engineers – 3 men * 1st/24th Regiment of Foot (2nd Warwickshire) (5 companies) – 14 officers, 450 NCOs and men * 2nd/24th Regiment of Foot (2nd Warwickshire) (1 company) – 5 officers, 150 NCOs and men *90th Regiment of Foot

The 90th Perthshire Light Infantry was a Scottish light infantry regiment of the British Army, raised in 1794. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 26th (Cameronian) Regiment of Foot to form the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in 188 ...

(Perthshire Light Infantry) – 10 men

* Army Service Corps – 3 men

* Army Hospital Corps

The Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) is a specialist corps in the British Army which provides medical services to all Army personnel and their families, in war and in peace. The RAMC, the Royal Army Veterinary Corps, the Royal Army Dental Corps ...

– 1 officer, 10 NCOs and men

* Imperial Mounted Infantry (1 squadron) – 28 NCOs and men

* Natal Mounted Police

The Natal Mounted Police (NMP) were the colonial police force of the Colony of Natal created in 1874 by Major John Dartnell, a farmer and retired officer in the British Army as a semi-military force to bolster the defences of Natal in South Africa ...

– 34 NCOs and men

* Natal Carbineers

The Ingobamakhosi Carbineers (formerly Natal Carbineers) is an infantry unit of the South African Army.

History Origins

The regiment traces its roots to 1854 but it was formally raised on 15 January 1855 and gazetted on 13 March of that year, ...

– 2 officers, 26 NCOs and men

* Newcastle Mounted Rifles – 2 officers, 15 NCOs and men

* Buffalo Border Guards – 1 officer, 7 NCOs and men

* Natal Native Pioneer Corps

The Natal Native Pioneer Corps, commonly referred to as the Natal Pioneers, was a British unit of the Zulu War. Raised in November/December 1878 the unit served throughout the war of 1879 to provide engineering support to the British invasion of ...

– 1 officer, 10 men

* 1st/3rd Natal Native Contingent (2 companies) – 11 officers, c. 300 NCOs and men

* 2nd/3rd Natal Native Contingent (2 companies) – 9 officers, c. 300 NCOs and men

Zulu forces

Right horn

uDududu, uNokenke regiments, part uNodwengu corps – 3,000 to 4,000 menChest

umCijo, uKhandampevu, regiments; part uNodwengu corps – 7,000 to 9,000 menLeft horn

inGobamakhosi, uMbonambi, uVe regiments – 5,000 to 6,000 menLoins (Reserves)

Undi corps, uDloko, iNdluyengwe, Indlondlo and Uthulwana regiments – 4,000 to 5,000 menAftermath

Analysis

The Zulus avoided the dispersal of their main fighting force and concealed the advance and location of this force until they were within a few hours' striking distance of the British. When the location of the main Zulu Impi was discovered by British scouts, the Zulus immediately advanced and attacked, achieving tactical surprise. The British, although they now had some warning of a Zulu advance, were unable to concentrate their central column. It also left little time and gave scant information for Pulleine to organise the defence. The Zulus had outmanoeuvred Chelmsford and their victory at Isandlwana was complete and forced the main British force to retreat out of Zululand until a far larger British Army could be shipped to South Africa for a second invasion. Recent historians, notably Lock and Quantrill in ''Zulu Victory'', argue that from the Zulu perspective the theatre of operations included the diversions around Magogo Hills and Mangeni Falls and that these diversions, which drew more than half of Chelmsford's forces away from Isandlwana, were deliberate. Also, the main Zulu force was not unexpectedly discovered in their encampment but was fully deployed and ready to advance on the British camp. These historians' view of the expanded battlefield considers Chelmsford to have been the overall commander of the British forces and that responsibility for the defeat lies firmly with him.strategic

Strategy (from Greek στρατηγία ''stratēgia'', "art of troop leader; office of general, command, generalship") is a general plan to achieve one or more long-term or overall goals under conditions of uncertainty. In the sense of the "art ...

lapses and failings in grand tactics on the part of high command under Bartle Frere and Chelmsford. Still, the latter comes under scrutiny for mistakes that may have led directly to the British defeat. The initial view, reported by Horace Smith-Dorrien

General Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien, (26 May 1858 – 12 August 1930) was a British Army General. One of the few British survivors of the Battle of Isandlwana as a young officer, he also distinguished himself in the Second Boer War.

Smi ...

, was that the British had difficulty unpacking their ammunition boxes fast enough. The box lids were screwed down, the screws were rusty and difficult to remove, there were too few screwdrivers, "standing orders" insisted that until a box was empty, no other boxes were to be opened, and the quartermasters were reluctant to distribute ammunition to units other than their own. Well-equipped and well-trained British soldiers could fire 10–12 rounds a minute. The lack of ammunition caused a lull in the defence and, in subsequent engagements with the Zulus, ammunition boxes were unscrewed in advance for rapid distribution. Numerous first hand accounts, including Smith-Dorrien's earliest in a letter to his father, indicate ammunition was available and being supplied.

Donald Morris in ''The Washing of the Spears

''The Washing of the Spears'' is a 1965 book about the " Zulu Nation under Shaka" and the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, written by Donald R. Morris.

The first edition, published in 1966 is over 600 pages with detailed bibliography. The book chronicle ...

'' argues that the men, fighting too far from the camp, ran out of ammunition, starting first with Durnford's men who were holding the right flank and who had been in action longer, which precipitated a slowdown in the rate of fire against the Zulus. This argument suggests that the ammunition was too far from the firing line and that the seventy rounds each man took to the firing line were not sufficient.Morris A different view, supported with evidence from the battlefield, such as Ian Knight and Lt. Colonel Snook's works, (the latter having written ''How Can Man Die Better?''), suggests that, although Durnford's men probably did run out of ammunition, the majority of men in the firing line did not. The discovery of the British line so far out from the camp has led Ian Knight to conclude that the British were defending too large a perimeter.

The official interrogation by Horse Guards under the direction of the Duke of Cambridge

Duke of Cambridge, one of several current royal dukedoms in the United Kingdom , is a hereditary title of specific rank of nobility in the British royal family. The title (named after the city of Cambridge in England) is heritable by male de ...

, the Field Marshal Commanding in Chief, in August 1879, concluded that the primary cause of the defeat was the "under estimate formed of the offensive fighting power of the Zulu army", additionally the investigation questions Chelmsford as to why the camp was not laagered and why there was a failure to reconnoitre and discover the nearby Zulu army. Colenso calls Chelmsford's neglecting to follow his own "Regulations for Field Forces in South Africa", which required that a defensible camp be established at every halt, fatal.

Numerous messages, some quite early in the day, had been sent to Chelmsford informing him, initially, of the presence of the Zulu near the camp and, subsequently, of the attack on the camp, with increasingly urgent pleas for help. The most egregious failure to respond occurred at around 1:30 pm when a message from Hamilton-Browne stating, "For God's sake come back, the camp is surrounded, and things I fear are going badly", was received by Lieutenant-Colonel Harness of the Royal Artillery and Major Black of the 2/24. They were leading the other four RA guns as well as two companies of the 2/24 and on their own initiative immediately marched back towards Isandlwana and had gone some two miles when they were ordered to return to Mangeni Falls by an aide sent by Chelmsford.

At long last but too late, finally Chelmsford became convinced of the seriousness of the situation on his left flank and rear when at 3:30pm he joined Hamilton-Browne's NNC and realised the camp had been taken. A surviving officer, Rupert Lonsdale, rode up and described the camp's fall to which Chelmsford replied, "But I left over 1,000 men to guard the camp". He quickly gathered his scattered forces and marched the column back to Isandlwana but arrived at sundown long after the battle ended and the Zulu army had marched off. The British camped on the field that night but left before sunrise without any examination of the ground as Chelmsford felt that it would demoralize his troops. The column then proceeded to Rorke's Drift

The Battle of Rorke's Drift (1879), also known as the Defence of Rorke's Drift, was an engagement in the Anglo-Zulu War. The successful British defence of the mission station of Rorke's Drift, under the command of Lieutenants John Chard of the ...

.

Though Isandlwana was a disaster for the British, the Zulu victory did not end the war. With the defeat of Chelmsford's central column, the invasion of Zululand collapsed and would have to be restaged. Not only were there heavy manpower casualties to the Main Column, but most of the supplies, ammunition and draught animals were lost. As King Cetshwayo feared, the embarrassment of the defeat would force the policy makers in London, who to this point had not supported the war, to rally to the support of the pro-war contingent in the Natal government and commit whatever resources were needed to defeat the Zulus. Despite local numerical superiority, the Zulus did not have the manpower, technological resources, or logistical capacity to match the British in another, more extended, campaign.

The Zulus may have missed an opportunity to exploit their victory and possibly win the war that day on their own territory. The reconnaissance force under Chelmsford was more vulnerable to being defeated by an attack than the camp. It was strung out and somewhat scattered, it had marched with limited rations and ammunition it could not now replace, and it was panicky and demoralized by the defeat at Isandlwana.

Near the end of the battle, about 4,000 Zulu warriors of the unengaged reserve Undi impi, after cutting off the retreat of the survivors to the Buffalo River southwest of Isandlwana, crossed the river and attacked the fortified mission station at

Though Isandlwana was a disaster for the British, the Zulu victory did not end the war. With the defeat of Chelmsford's central column, the invasion of Zululand collapsed and would have to be restaged. Not only were there heavy manpower casualties to the Main Column, but most of the supplies, ammunition and draught animals were lost. As King Cetshwayo feared, the embarrassment of the defeat would force the policy makers in London, who to this point had not supported the war, to rally to the support of the pro-war contingent in the Natal government and commit whatever resources were needed to defeat the Zulus. Despite local numerical superiority, the Zulus did not have the manpower, technological resources, or logistical capacity to match the British in another, more extended, campaign.

The Zulus may have missed an opportunity to exploit their victory and possibly win the war that day on their own territory. The reconnaissance force under Chelmsford was more vulnerable to being defeated by an attack than the camp. It was strung out and somewhat scattered, it had marched with limited rations and ammunition it could not now replace, and it was panicky and demoralized by the defeat at Isandlwana.

Near the end of the battle, about 4,000 Zulu warriors of the unengaged reserve Undi impi, after cutting off the retreat of the survivors to the Buffalo River southwest of Isandlwana, crossed the river and attacked the fortified mission station at Rorke's Drift

The Battle of Rorke's Drift (1879), also known as the Defence of Rorke's Drift, was an engagement in the Anglo-Zulu War. The successful British defence of the mission station of Rorke's Drift, under the command of Lieutenants John Chard of the ...

. The station was defended by only 140 British soldiers, who nonetheless inflicted considerable casualties and repelled the attack. Elsewhere, the left and right flanks of the invading forces were now isolated and without support. The No. 1 column under the command of Charles Pearson

Charles Pearson (4 October 1793 – 14 September 1862) was a British lawyer and politician. He was solicitor to the City of London, a reforming campaigner, and – briefly – Member of Parliament for Lambeth. He campaigned against corruption ...

was besieged for two months by a Zulu force led by kaMpande and Mavumengwana, at Eshowe

Eshowe is the oldest town of European settlement in Zululand, historically also known as Eziqwaqweni, Ekowe or kwaMondi. Eshowe's name is said to be inspired by the sound of wind blowing through the more than 4 km² of the indigenous Dlinza ...

, while the No. 4 column under Evelyn Wood halted its advance and spent most of the next two months skirmishing in the northwest around Tinta's Kraal.

Following Isandlwana and Rorke's Drift, the British and Colonials were in complete panic over the possibility of a counter invasion of Natal by the Zulus. All the towns of Natal 'laagered' up and fortified and provisions and stores were laid in. Bartle Frere stoked the fear of invasion despite the fact that, aside from Rorke's Drift, the Zulus made no attempt to cross the border. Immediately following the battle, Zulu Prince Ndanbuko urged them to advance and take the war into the colony but they were restrained by a commander, kaNthati, reminding them of Cetshwayo's prohibiting the crossing of the border. Unbeknownst to the inhabitants of Natal, Cetshwayo, still hoping to avoid outright war, had prohibited any crossing of the border in retaliation and was incensed over the violation of the border by the attack on Rorke's Drift.

The British government's reasoning for a new invasion was threefold. The first was the loss of national pride as a result of the defeat, and the desire to avenge it by winning the war. The second concerned the domestic political implications at the next parliamentary elections held in Britain.Knight (2003), p. 67 However, despite the second invasion attempt, the British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As moder ...

Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a centr ...

and his Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

lost the 1880 general election. The final reason concerned the Empire; unless the British were seen to win a clear-cut victory against the Zulus, it would send a signal to the outside world that the British Empire was vulnerable to the point where the destruction of a British field army could alter the policy of Britain's government. The British government was concerned that the Zulu victory could inspire imperial unrest, particularly among the Boers

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this a ...

, and as such sought to quash any such possibilities by swiftly defeating the Zulu Kingdom.

After Isandlwana, the British field army in South Africa was heavily reinforced and again invaded Zululand. Sir Garnet Wolseley was sent to take command and relieve Chelmsford, as well as Bartle Frere. Chelmsford, however, avoided handing over command to Wolseley and managed to defeat the Zulus in a number of engagements, the last of which was the Battle of Ulundi

The Battle of Ulundi took place at the Zulu Kingdom, Zulu capital of Ulundi (Zulu:''oNdini'') on 4 July 1879 and was the last major battle of the Anglo-Zulu War. The British army broke the military power of the Zulu Kingdom, Zulu nation by def ...

, followed by capture of King Cetshwayo. With the fall of the Disraeli government, Bartle Frere was recalled in August 1880 and the policy of Confederation was abandoned. The British government encouraged the subkings of the Zulus to rule their subkingdoms without acknowledging a central Zulu power. By the time King Cetshwayo was allowed to return home, the Zulu Kingdom had ceased to exist as an independent entity.

The measure of respect that the British gained for their opponents as a result of Isandlwana can be seen in that in none of the other engagements of the Zulu War did the British attempt to fight again in their typical linear formation, known famously as the Thin Red Line, in an open-field battle with the main Zulu impi. In the battles that followed, the British, when facing the Zulu, entrenched themselves or formed very close-order formations, such as the square

In Euclidean geometry, a square is a regular quadrilateral, which means that it has four equal sides and four equal angles (90- degree angles, π/2 radian angles, or right angles). It can also be defined as a rectangle with two equal-length a ...

.

Recriminations

Chelmsford realised that he would need to account to the government and to history for the disaster. He quickly fixed blame on Durnford, claiming Durnford disobeyed his orders to fix a proper defensive camp, although there is no evidence such an order was issued and there would hardly have been time for Durnford to entrench. Further, it had been Chelmsford's decision not to entrench the camp, as it was meant to be temporary. Wolseley wrote on 30 September 1879 when, later in the war, the Prince Imperial of France was killed by the Zulu: "I think this is very unfair, and is merely a repetition of what was done regarding the Isandlwana disaster where the blame was thrown upon Durnford, the real object in both instances being apparently to screen Chelmsford." Later, Chelmsford launched a new and successful campaign in Zululand, routing the Zulu army, capturing the Royal Kraal of Ulundi, and thus partially retrieving his reputation. He never held another field command. Following the war's conclusion and his return to Great Britain, Chelmsford sought an audience withGladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-cons ...

, who had become Prime Minister in April 1880, but his request was refused, a very public slight and a clear sign of official disapproval. Chelmsford, however, obtained an audience with Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

to personally explain the events. She asked Gladstone to meet Chelmsford; this meeting was brief, and during it Gladstone voiced his displeasure.

Some historians hold that the victory at Ulindi was a token one, driven by the need for Lord Chelmsford to salvage some success after Isandhlwana, and the British withdrew quickly followed by Chelmsford's resignation as commander of the British forces. The end of the war saw the Zulu retaining their lands.

::"Seen in terms of the political ends for which the war was fought, the battle of Ulundi, like the campaign in Zululand itself, was a failure. The effectiveness of Zulu resistance had destroyed the policy which brought about the war, and discredited the men responsible. The only point on which all whites agreed was that some form of face-saving military victory was required in Zululand. Ulundi was that token military victory. It did not end the war in Zululand—peace was attained by Sir Garnet Wolseley who, as Chelmsford scurried out of the country, entered Zululand proclaiming that if the Zulu returned to their homes they would be left in full possession of their land and their property. By July 1879 both sides desired an end to hostilities. For reasons of economy, because of military requirements elsewhere and the political capital being made out of the war, the British government wanted an end to this embarrassing demonstration of military ineptitude. Any chance of an easy military conquest of the entire territory seemed slight: the army was tied to its inadequate supply lines, and conquest would have necessitated a change in strategy and tactics which presupposed a change in military leadership. It was easier and cheaper to elevate Ulundi to the rank of a crushing military victory and abandon plans to subjugate the Zulu people than to create the force of mobile fighting units which would have been required to conquer the Zulu completely."Guy, J. J. A Note on Firearms in the Zulu Kingdom with special reference to the Anglo-Zulu War, 1879. Journal African History, XII, 1971, 557-570

See also

*Bambatha Rebellion

The Bambatha Rebellion (or the Zulu Rebellion) of 1906 was led by Bambatha kaMancinza (c. 1860–1906?), leader of the Zondi clan of the Zulu people, who lived in the Mpanza Valley (now a district near Greytown, KwaZulu-Natal) against British ...

* Battle of Blood River

The Battle of Blood River (16 December 1838) was fought on the bank of the Ncome River, in what is today KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa between 464 Voortrekkers ("Pioneers"), led by Andries Pretorius, and an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 Zulu. Es ...

* Colony of Natal

The Colony of Natal was a British colony in south-eastern Africa. It was proclaimed a British colony on 4 May 1843 after the British government had annexed the Boer Natalia Republic, Republic of Natalia, and on 31 May 1910 combined with three o ...

* African Litany

''African Litany'' is the second studio album from South African band Juluka, released in 1981.

It features lyrics sung in English and Zulu.

The first track, Impi, which became one of the band's hits, retells the story of the Battle of Isandl ...

, the second album by Johnny Clegg

Jonathan Paul Clegg, (7 June 195316 July 2019) was a South African musician, singer-songwriter, dancer, anthropologist and anti-apartheid activist, some of whose work was in musicology focused on the music of indigenous South African people ...

and his band Juluka

Juluka was a South African music band formed in 1969 by Johnny Clegg and Sipho Mchunu. means "sweat" in Zulu, and was the name of a bull owned by Mchunu. The band was closely associated with the mass movement against apartheid.

History

At th ...

, containing the track "Impi" about this battle.

* List of Zulu War Victoria Cross recipients

The Victoria Cross (VC) was awarded to 23 members of the British Armed Forces and colonial forces for actions performed during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. The Victoria Cross is a military decoration awarded for valour "in the face of the ene ...

* Military history of the United Kingdom

The military history of the United Kingdom covers the period from the creation of the united Kingdom of Great Britain, with the political union of England and Scotland in 1707, to the present day.

From the 18th century onwards, with the expansi ...

* Military history of South Africa

The military history of South Africa chronicles a vast time period and complex events from the dawn of history until the present time. It covers civil wars and wars of aggression and of self-defence both within South Africa and against it. It in ...

* ''Zulu Dawn

''Zulu Dawn'' is a 1979 American adventure war film about the historical Battle of Isandlwana between British and Zulu forces in 1879 in South Africa. The screenplay was by Cy Endfield, from his book, and Anthony Storey. The film was directed ...

''

*Battle of Rorke's Drift

The Battle of Rorke's Drift (1879), also known as the Defence of Rorke's Drift, was an engagement in the Anglo-Zulu War. The successful British defence of the mission station of Rorke's Drift, under the command of Lieutenants John Chard of the ...

* Zululand Empire

*'' Zulu''

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * Morris, Donald R. ''The Washing of the Spears: A History of the Rise of the Zulu Nation under Shaka and Its Fall in the Zulu War of 1879'' Da Capo Press, 1998, . * Smith-Dorrien, Horace. ''Memories of Forty-eight Years Service'', London, 1925. * Spiers, Edward M. . ''The Scottish Soldier and Empire'', 1854–1902, Edinburgh University Press, 2006. *Further reading

* Clarke, Sonia ''The Invasion of Zululand'', Johannesburg, 1979. * Coupland, Sir Reginald ''Zulu Battle Piece: Isandhlwana'', London, 1948. * Dutton, Roy ''Forgotten Heroes Zulu & Basuto Wars'', Infodial, 2010 . * * Furneaux, R.. ''The Zulu War: Isandhlwana & Rorke's Drift'' W&N (Great Battles of History Series), 1963. * * Greaves, Adrian. ''Isandlwana'', Cassell & Co, 2001, . * Greaves, Adrian. ''Rorke's Drift'', Cassell & Co., 2003 . * Jackson, F.W.D. ''Hill of the Sphinx'' London, 2002. * Jackson, F.W.D. and Whybra, Julian ''Isandhlwana and the Durnford Papers'', (Journal of the Victorian Military Society, March 1990, Issue 60). * Knight, Ian ''Brave Men's Blood'', London, 1990. . * Knight, Ian ''Zulu'', (London, 1992) * Knight, Ian ''Zulu Rising'', London, 2010. . * Whybra, Julian. ''England's Sons'', Billericay, (7th ed.), 2010. * Yorke, Edmund. ''Isandlwana 1879''. 2016.External links

Zulu: The True Story By Dr. Saul David

Secrets of the Dead – Day of the Zulu

Travellers Impressions

* The Battle of Isandlwana 22 January 1879, Ian Knight vide

* Forgotten Heroes Zulu & Basuto Wars, Roy Dutton,

Battle_Of Conflicts_in_1879

1879_in_the_Zulu_Kingdom.html" ;"title="Conflicts in 1879">Battle Of Conflicts in 1879

1879 in the Zulu Kingdom">Conflicts in 1879">Battle Of Conflicts in 1879

1879 in the Zulu Kingdom Battles of the Anglo-Zulu War Military history of South Africa Battles involving the United Kingdom History of KwaZulu-Natal January 1879 events Battles involving the Zulu