Battle of Guilford on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

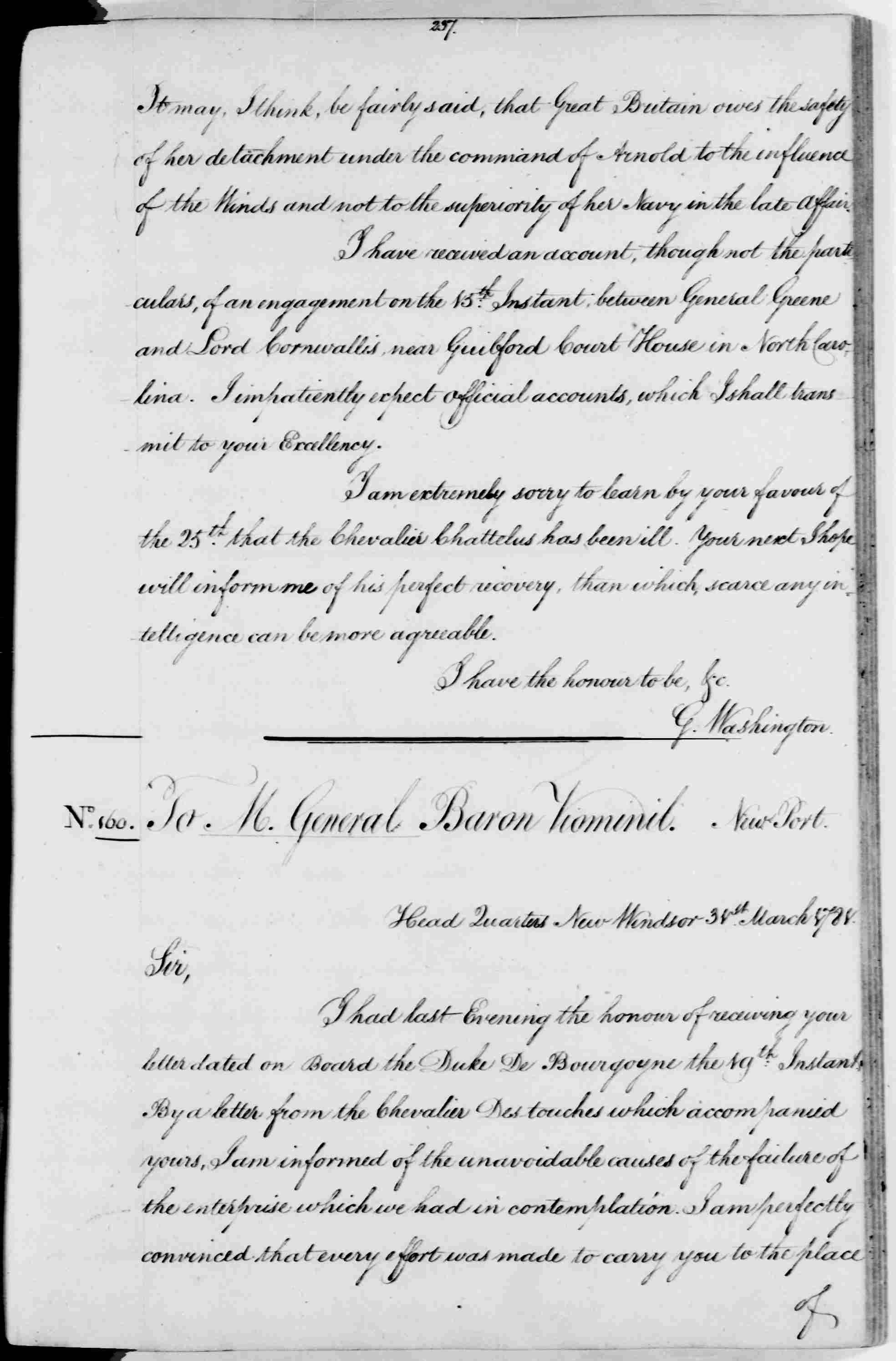

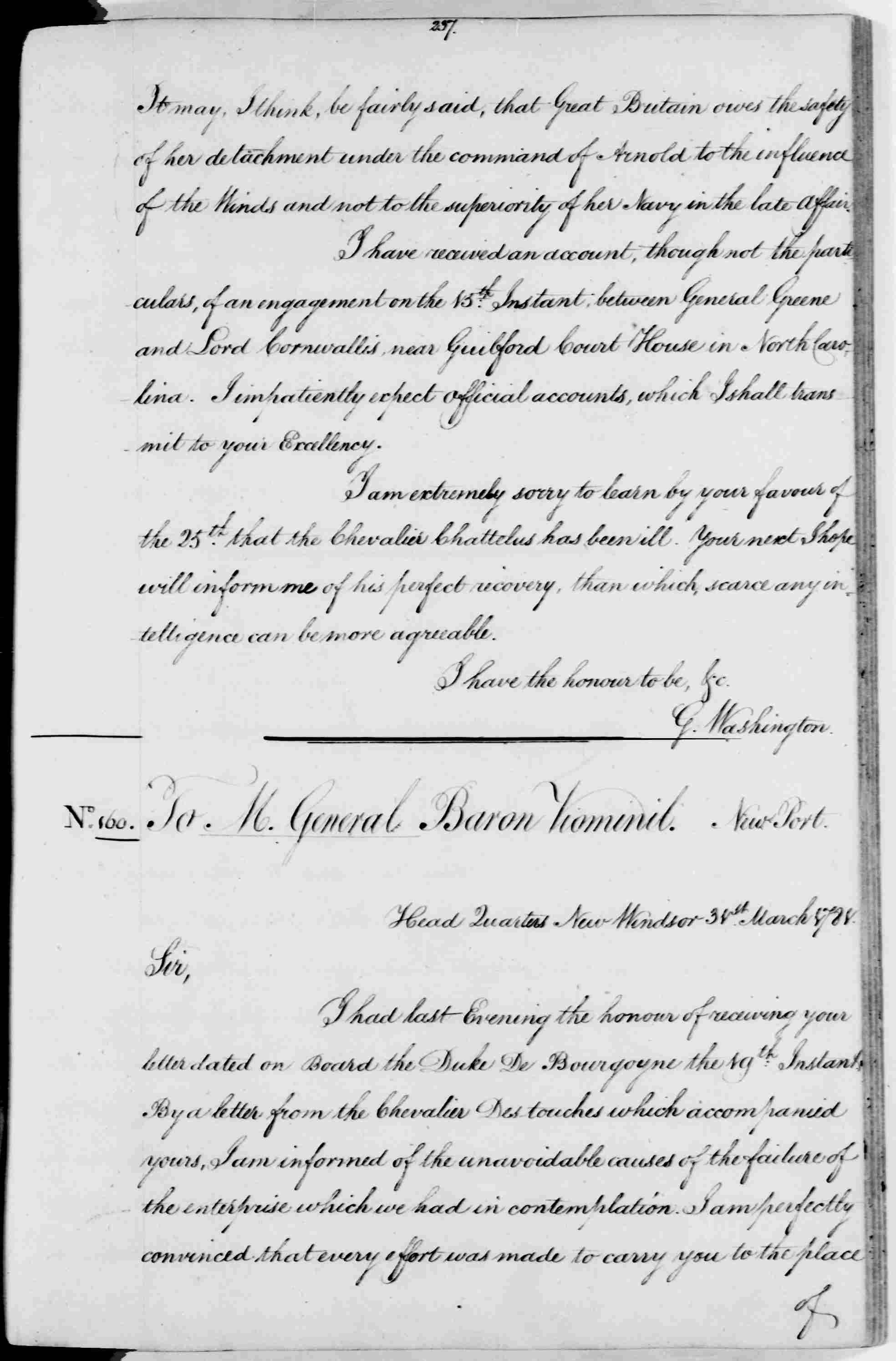

The Battle of Guilford Court House was on March 15, 1781, during the

The British, by holding ground with their usual tenacity despite fewer troops, were victorious. However, Cornwallis suffered unsustainable casualties and subsequently withdrew to the coast to re-group, leaving the Americans with the strategic advantage. Seeing the Guilford battle as a classic Pyrrhic victory, British Whig Party leader and war critic

The British, by holding ground with their usual tenacity despite fewer troops, were victorious. However, Cornwallis suffered unsustainable casualties and subsequently withdrew to the coast to re-group, leaving the Americans with the strategic advantage. Seeing the Guilford battle as a classic Pyrrhic victory, British Whig Party leader and war critic

; essay by Janie B. Cheaney; retrieved; Greene reported his casualties as 57 killed, 111 wounded, and 161 missing among the Continental troops, and 22 killed, 74 wounded, and 885 missing for the militia--a total of 79 killed, 185 wounded, and 1,046 missing. Of those reported missing, 75 were wounded men who were captured by the British. When Cornwallis resumed his march, he left these 75 wounded prisoners at Cross Creek, Cornwallis having earlier left 70 of his own most severely wounded men at the Quaker settlement of New Garden near

Guilford Courthouse National Military Park websiteAnimation of the Battle of Guilford Courthouse

{{DEFAULTSORT:Battle Of Guilford Court House 1781 in the United States Conflicts in 1781 Guilford Court House Guilford Court House Guilford Court House Guilford Court House History of Greensboro, North Carolina 1781 in North Carolina

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, at a site that is now in Greensboro

Greensboro (; formerly Greensborough) is a city in and the county seat of Guilford County, North Carolina, United States. It is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, third-most populous city in North Carolina after Charlotte, North Car ...

, the seat of Guilford County, North Carolina

Guilford County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of the 2020 census, the population is 541,299, making it the third-most populous county in North Carolina. The county seat, and largest municipality, is Greensboro. ...

. A 2,100-man British force under the command of Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United S ...

defeated Major General Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene (June 19, 1786, sometimes misspelled Nathaniel) was a major general of the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War. He emerged from the war with a reputation as General George Washington's most talented and dependab ...

's 4,500 Americans. The British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

, however, suffered considerable casualties (with estimates as high as 27% of their total force).

The battle was "the largest and most hotly contested action" in the American Revolution's southern theater. Before the battle, the British had great success in conquering much of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

and South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

with the aid of strong Loyalist factions and thought that North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and ...

might be within their grasp. In fact, the British were in the process of heavy recruitment in North Carolina when this battle put an end to their recruiting drive. In the wake of the battle, Greene moved into South Carolina, while Cornwallis chose to march into Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

and attempt to link with roughly 3,500 men under British Major General Phillips and American turncoat Benedict Arnold. These decisions allowed Greene to unravel British control of the South, while leading Cornwallis to Yorktown, where he eventually surrendered to General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

and French Lieutenant General Comte de Rochambeau

Marshal Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, 1 July 1725 – 10 May 1807, was a French nobleman and general whose army played the decisive role in helping the United States defeat the British army at Yorktown in 1781 during the ...

.

The battle is commemorated at Guilford Courthouse National Military Park

Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, at 2332 New Garden Road in Greensboro, Guilford County, North Carolina, commemorates the Battle of Guilford Court House, fought on March 15, 1781. This battle opened the campaign that led to American vi ...

and associated Hoskins House Historic District

Hoskins House Historic District, also known as Tannenbaum Park, is a historic log cabin and national historic district located at Greensboro, Guilford County, North Carolina. The Hoskins House is a late-18th or early-19th century chestnut log dw ...

.

Prelude

On 18 January,Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United S ...

learned he had lost one-quarter of his army at the Battle of Cowpens

The Battle of Cowpens was an engagement during the American Revolutionary War fought on January 17, 1781 near the town of Cowpens, South Carolina, between U.S. forces under Brigadier General Daniel Morgan and Kingdom of Great Britain, British for ...

. Yet he was still determined to pursue Greene into North Carolina and destroy Greene's army. According to Cornwallis, "The loss of my light troops could only be remedied by the activity of the whole corps." At Ramsour's Mill, Cornwallis burned his baggage train, except the wagons he needed to carry medical supplies, salt, ammunition, and the sick. In the words of Charles O'Hara, "In this situation, without Baggage, necessaries, or Provisions of any sort...it was resolved to follow Greene's army to the end of the World." As Cornwallis departed Ramsour's Mill on 28 January, Greene sought to reunite his command but ordered Edward Carrington

Edward Carrington (February 11, 1748 – October 28, 1810) was an American soldier and statesman from Virginia. During the American Revolutionary War he became a lieutenant colonel of artillery in the Continental Army. He distinguished himself a ...

to prepare for possible retreat across the Dan River

The Dan River flows in the U.S. states of North Carolina and Virginia. It rises in Patrick County, Virginia, and crosses the state border into Stokes County, North Carolina. It then flows into Rockingham County. From there it flows back int ...

into Virginia. In Greene's words, "It is necessary we should take every possible precaution. But I am not without hopes of ruining Lord Cornwallis, if he persists in his mad scheme of pushing through the Country..." On 3 February, Greene joined Daniel Morgan's Continentals at Trading Ford on the Yadkin River

The Yadkin River is one of the longest rivers in North Carolina, flowing . It rises in the northwestern portion of the state near the Blue Ridge Parkway's Thunder Hill Overlook. Several parts of the river are impounded by dams for water, p ...

, and on 7 February, Lighthorse Harry Lee

Henry Lee III (January 29, 1756 – March 25, 1818) was an early American Patriot and U.S. politician who served as the ninth Governor of Virginia and as the Virginia Representative to the United States Congress. Lee's service during the Amer ...

rendezvoused with the rebel army at Guilford Courthouse. By 9 February, Greene commanded 2036 men, 1426 of whom were regular infantry, whereas Cornwallis had about 2440 men, 2000 of whom were regulars. Now began the "Race to the Dan": Greene's council of war

A council of war is a term in military science that describes a meeting held to decide on a course of action, usually in the midst of a battle. Under normal circumstances, decisions are made by a commanding officer, optionally communicated ...

recommended continuing the retreat, opting to fight at a future date and location. By 14 February, Greene's army was safely across the Dan after a retreat that was, according to Tarleton, "judiciously designed and vigorously executed." Cornwallis was now from his supply base at Camden, South Carolina

Camden is the largest city and county seat of Kershaw County, South Carolina. The population was 7,764 in the 2020 census. It is part of the Columbia, South Carolina, Metropolitan Statistical Area. Camden is the oldest inland city in South C ...

. He established camp at Hillsborough and attempted to forage for supplies and recruit Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

. Though Greene's army enjoyed an abundance of food in Halifax County, Virginia

Halifax County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 34,022. Its county seat is Halifax.

History

Occupied by varying cultures of indigenous peoples for thousands of years, in histo ...

, Cornwallis found a "scarcity of provisions," resorted to plundering the farms of the local inhabitants, and lost men "...in consequence of their Straggling out of Camp in search of whiskey." On 19 February, Greene sent Lee's Legion

Lee's Legion (also known as the 2nd Partisan Corps) was a military unit within the Continental Army during the American Revolution. It primarily served in the Southern Theater of Operations, and gained a reputation for efficiency, bravery on t ...

on a reconnaissance mission south across the Dan. By then, according to Buchanan, " Buford's Massacre inflamed rebel passions. Pyle's Massacre

Pyle's Massacre, (also Pyle's defeat, Pyle's hacking match, or Battle of Haw River), was fought during the American Revolutionary War in present-day Alamance County on February 24, 1781. The battle was between Patriot troops attached to the Con ...

devastated Tory morale." On 22 February, Greene moved his army south across the Dan. On 25 February, forced to abandon Hillsborough, Cornwallis moved his camp to the south of Alamance Creek between the Haw River

The Haw River is a tributary of the Cape Fear River, approximately 110 mi (177 km) long, that is entirely contained in north central North Carolina in the United States. It was first documented as the "Hau River" by John Lawson, an E ...

and the Deep River. Greene camped on the north side of the Creek, within of Cornwallis's camp. By 6 March, Cornwallis's men suffered from hunger. His men plundered tory and rebel inhabitants, and desertions rose, forcing Cornwallis to seek a definitive battle with Greene. Cornwallis had lost almost 400 men through disease, desertion or death, reducing his strength to about 2000 men. On 10 March, Greene was joined by North Carolina militia, led by John Butler John Butler may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*John "Picayune" Butler (died 1864), American performer

* John Butler (artist) (1890–1976), American artist

*John Butler (author) (born 1937), British author and YouTuber

*John Butler (born 1954), ...

and Thomas Eaton, and Virginia militia, led by Robert Lawson. On 12 March, Greene marched his army of about 4440, 1762 of whom were Continentals, to Guilford Courthouse.

Because of the fighting, thousands of slaves had escaped from plantations in South Carolina and other southern states, many joining the British to fight for their personal freedom. In the waning months of the war, the British evacuated more than 3,000 freedmen to Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, with others going to London and Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

. Northern slaves escaped to the British lines in occupied cities, such as New York.

On 14 March, Cornwallis learned that Greene was at Guilford Court House. On 15 March, Cornwallis marched down the road from New Garden toward Guilford Courthouse. The advance guard of both armies collided near the Quaker New Garden Meeting House, west of Guilford Courthouse. Greene had sent Lee's Legion and William Campbell's Virginia riflemen to reconnoiter Cornwallis' camp. At 2 A.M., the rebels noticed Tarleton's movements, and at 4 A.M. Lee's and Tarleton's men made contact. Tarleton started a retreat, while suffering a musket wound to the right hand, and as Lee pursued, Lee came in contact with the British Guards, who forced Lee to retreat.

Battle

Greene had deployed his army in three lines. Greene's first line was along asplit-rail fence

A split-rail fence, log fence, or buck-and-rail fence (also historically known as a zigzag, worm, snake or snake-rail fence due to its meandering layout) is a type of fence constructed in the United States and Canada, and is made out of timber lo ...

, where the New Camden road emerged from the woods. On the right was Butler's regiment of 500 North Carolina militia, plus Charles Lynch's 200 Virginia riflemen, William Washington

William Washington (February 28, 1752 – March 6, 1810) was a cavalry officer of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, who held a final rank of brigadier general in the newly created United States after the war. Primarily ...

's 90 dragoons, and Robert Kirkwood's 80 man Delaware Line. On the left was Eaton's regiment of 500 North Carolina militia, along with William Campbell's 200 riflemen, and Lee's Legion of 75 horse and 82 foot. In the middle was a dual six-pounder battery led by Anthony Singleton. Greene's second line was behind the first: 1200 Virginia militia, led by Robert Lawson and Edward Stevens. Greene's third line was another to the right rear, in a clearing: 1400 Continentals, including Isaac Huger's Virginia Brigade, Otho Holland Williams's Maryland Brigade, and Peter Jacquett's Delaware Company. Between the Virginia and Maryland units was a battery of two six-pounders, led by Samuel Finley.

On 15 March, Cornwallis's column appeared along the New Camden Road at 1:30 P.M, and Singleton commenced firing his two six-pounders, while John McLeod's Royal Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as "The Gunners", is one of two regiments that make up the artillery arm of the British Army. The Royal Regiment of Artillery comprises t ...

battery responded with three six-pounders. According to Buchanan, Cornwallis, "...did not know how many men Greene had. He was ignorant of the terrain too, he also lacked intelligence on Greene's dispositions. Cornwallis "...had marched hundreds of miles, had driven his army to rags and hunger..." Cornwallis deployed the 33rd Foot and Royal Welsh Fusiliers on his left wing, led by James Webster, and supported by Charles O'Hara with his 2nd Guards Battalion, Grenadiers, and the Jägers. Cornwallis's right wing, led by Alexander Leslie

Alexander Leslie, 1st Earl of Leven (15804 April 1661) was a Scottish soldier in Swedish and Scottish service. Born illegitimate and raised as a foster child, he subsequently advanced to the rank of a Swedish Field Marshal, and in Scotland b ...

, included the 2nd Battalion of Fraser's Highlanders and Hessian Regiment von Bose, supported by the 1st Guards Battalion. Tarleton's British Legion Horse was in reserve, but Cornwallis lacked Tory auxiliaries.

The British moved forward. The North Carolina militia, according to Singleton, "contrary to custom, behaved well for militia" and fired their volley. Captain Dugald Stuart noted, "One half of the Highlanders dropt on that spot." Thomas Saumarez called it a "most galling and destructive fire." As the British advanced, Sergeant Roger Lamb noted, "...within forty yards of the enemy's line it was perceived that their whole line had their arms presented, and resting on a rail fence...They were taking aim with nice precision. At this awful moment, a general pause took place...then Colonel Webster rode forward in front of the 23rd regiment and said...'Come on, my brave Fuzileers.' This operated like an inspiring voice..." As instructed by Greene, the North Caroline militia retired through Greene's second line. The British now came under enfilading

Enfilade and defilade are concepts in military tactics used to describe a military formation's exposure to enemy fire. A formation or position is "in enfilade" if weapon fire can be directed along its longest axis. A unit or position is "in de ...

fire from the riflemen and Continentals on their flanks, forcing Cornwallis to order forward his supporting units. On Greene's left, Lee's Legion and Campbell's Virginians retired in a northeasterly direction, instead of straight back, resulting in their fight with the Regiment von Bose and the 1st Guards Battalion--a backwoods fight a mile from the main fighting.

As the British moved through the woods, the contest reduced to small firefights, as the British forced the Virginians back. Cornwallis, despite having a horse shot from under him, led the British clearing of the woods. The British then faced the Continentals in Greene's third line.

James Webster led the first British units out of the woods—the Jägers, the light infantry of the Guards, and the 33rd Foot—in a charge against the Continentals. The British were able to come within a before they were repulsed by the Continental volley of the 1st Maryland and Delaware companies. However, as the 2nd Guards cleared the woods, they forced the 2nd Maryland to run and captured Finley's two six-pounders. The 1st Maryland then turned and engaged the 2nd Guards. William Washington's dragoons charged through the rear of the 2nd Guards, turned, and charged through the 2nd Guards a second time. A 1st Maryland bayonet charge

A bayonet (from French ) is a knife, dagger, sword, or spike-shaped weapon designed to fit on the end of the muzzle of a rifle, musket or similar firearm, allowing it to be used as a spear-like weapon.Brayley, Martin, ''Bayonets: An Illu ...

followed Washington.

Cornwallis then ordered McLeod to fire grapeshot

Grapeshot is a type of artillery round invented by a British Officer during the Napoleonic Wars. It was used mainly as an anti infantry round, but had other uses in naval combat.

In artillery, a grapeshot is a type of ammunition that consists of ...

into the mass of fighting men. The grape killed Americans and British but cleared the field of both. Cornwallis then advanced toward the gap left by the 2nd Maryland. At 3:30 P.M. Greene ordered his troops to withdraw under covering fire by the 4th Virginians. Cornwallis initially ordered a pursuit but recalled his men. In the words of Buchanan, "...reduced to slightly over 1400 effectives...Cornwallis, had ruined his army."

Aftermath

The battle lasted ninety minutes. The British engaged half as many as the Americans yet won possession of the battlefield. However, almost a quarter of the British became casualties. The Americans withdrew intact, which accomplished Greene's primary objective. The British, by holding ground with their usual tenacity despite fewer troops, were victorious. However, Cornwallis suffered unsustainable casualties and subsequently withdrew to the coast to re-group, leaving the Americans with the strategic advantage. Seeing the Guilford battle as a classic Pyrrhic victory, British Whig Party leader and war critic

The British, by holding ground with their usual tenacity despite fewer troops, were victorious. However, Cornwallis suffered unsustainable casualties and subsequently withdrew to the coast to re-group, leaving the Americans with the strategic advantage. Seeing the Guilford battle as a classic Pyrrhic victory, British Whig Party leader and war critic Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled ''The Honourable'' from 1762, was a prominent British Whig statesman whose parliamentary career spanned 38 years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He was the arch-riv ...

echoed Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

's famous quotation of Pyrrhus by saying, "Another such victory would ruin the British Army!"

In a letter to Lord George Germain

George Germain, 1st Viscount Sackville, PC (26 January 1716 – 26 August 1785), styled The Honourable George Sackville until 1720, Lord George Sackville from 1720 to 1770 and Lord George Germain from 1770 to 1782, was a British soldier and p ...

delivered by Cornwallis's aide-de-camp, Captain Broderick, Cornwallis commented: "From our observation, and the best accounts we could procure, we did not doubt but the strength of the enemy exceeded 7,000 men...I cannot ascertain the loss of the enemy, but it must have been considerable; between 200 and 300 dead were left on the field of battle...many of their wounded escaped...Our forage parties have reported to me that houses in a circle six to eight miles around us are full of others...We took few prisoners."

Cornwallis wrote about the British force, "The conduct and actions of the officers and soldiers that composed this little army will do more justice to their merit than I can by words. Their persevering intrepidity in action, their invincible patience in the hardships and fatigues of a march of above 600 miles, in which they have forded several large rivers and numberless creeks, many of which would be reckoned large rivers in any other country in the world, without tents or covering against the climate, and often without provisions, will sufficiently manifest their ardent zeal for the honour and interests of their Sovereign and their country."

After the battle, the British occupied a large expanse of woodland that offered no food and shelter, and the night brought torrential rains. Fifty of the wounded died before sunrise. Had the British followed the retreating rebels, the redcoats might have come across the rebel baggage and supply wagons, which remained where the Americans had camped on the west bank of the Salisbury road prior to the battle.

On March 17, two days after the battle, Cornwallis reported his casualties as 3 officers and 88 men of other ranks killed, and 24 officers and 384 men of other ranks wounded, with a further 25 men missing in action. Webster was wounded during the battle and died two weeks later. Lieutenant-Colonel Tarleton, commander of the loyalist provincial British Legion, was another notable officer who was wounded, losing two fingers from taking a bullet in his right hand.''Tarleton''; essay by Janie B. Cheaney; retrieved; Greene reported his casualties as 57 killed, 111 wounded, and 161 missing among the Continental troops, and 22 killed, 74 wounded, and 885 missing for the militia--a total of 79 killed, 185 wounded, and 1,046 missing. Of those reported missing, 75 were wounded men who were captured by the British. When Cornwallis resumed his march, he left these 75 wounded prisoners at Cross Creek, Cornwallis having earlier left 70 of his own most severely wounded men at the Quaker settlement of New Garden near

Snow Camp

Snow Camp is an unincorporated community in southern Alamance County, North Carolina, United States, noted for its rich history and as the site of the Snow Camp Outdoor Theater. The community has a large Quaker population centered on the pre-revo ...

. An analysis of Revolutionary pension records by Lawrence E. Babits and Joshua B. Howard led the authors to conclude that Greene's killed and wounded at the Battle were "probably 15-20 percent higher than shown by official returns," with a likely "90-94 killed and 211-220 wounded." Apart from the wounded prisoners, most of the other men returned as 'missing' were North Carolina militiamen who returned to their homes after the battle.

To avoid another Camden, Greene retreated with his forces intact. With his small army, fewer than 2,000, Cornwallis declined to follow Greene into the back country. Retiring to Hillsborough, Cornwallis raised the royal standard, offered protection to loyalists, and for the moment appeared to be master of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

and the two Carolinas. In a few weeks, however, he abandoned the heart of the state and marched to the coast at Wilmington, North Carolina

Wilmington is a port city in and the county seat of New Hanover County in coastal southeastern North Carolina, United States.

With a population of 115,451 at the 2020 census, it is the eighth most populous city in the state. Wilmington is t ...

, where he could recruit and refit his army.

At Wilmington Cornwallis faced a serious problem. Instead of remaining in North Carolina, he wished to march into Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, justifying the move on the grounds that until he occupied Virginia, he could not firmly hold the more southerly states he had just overrun. General Clinton sharply criticized the decision as unmilitary and as having been made contrary to his instructions. To Cornwallis he wrote in May: "Had you intimated the probability of your intention, I should certainly have endeavoured to stop you, as I did then, as well as now, consider such a move likely to be dangerous to our interests in the Southern Colonies." For three months, Cornwallis raided every farm or plantation he came across, from which he took hundreds of horses for his dragoons. He converted another 700 infantry to mounted troops. During these raids, he freed thousands of slaves, of whom 12,000 joined his own force.

General Greene boldly pushed toward Camden and Charleston, South Carolina with a view to drawing Cornwallis to the points where he was the year before, as well as driving back Lord Rawdon, whom Cornwallis had left in that field. In his main object—the recovery of the southern states—Greene succeeded by the close of the year, but not without hard fighting and reverses. Greene said, "We fight, get beat, rise, and fight again."

Legacy

Every year, on or about March 15, re-enactors in period uniforms present a tactical demonstration of Revolutionary War fighting techniques on or near the battle site, major portions of which are preserved in theGuilford Courthouse National Military Park

Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, at 2332 New Garden Road in Greensboro, Guilford County, North Carolina, commemorates the Battle of Guilford Court House, fought on March 15, 1781. This battle opened the campaign that led to American vi ...

, established in 1917. Recent research has shown that the battlefield extended into the area now within the boundaries of the adjacent Greensboro Country Park to the east.

Three current Army National Guard units (116th IN, 175th IN and 198th SIG) are derived from American units that participated in the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. There are only thirty Army National Guard and active Regular Army units with lineages that go back to the colonial era.

On Sunday, March 13, 2016, a Crown Forces Monument was opened at the Guilford Courthouse National Military Park

Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, at 2332 New Garden Road in Greensboro, Guilford County, North Carolina, commemorates the Battle of Guilford Court House, fought on March 15, 1781. This battle opened the campaign that led to American vi ...

in honor of the officers and men of Cornwallis's army.

The town of Gilford, New Hampshire

Gilford is a town in Belknap County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 7,699 at the 2020 census, up from 7,126 at the 2010 census.United States Census BureauAmerican FactFinder 2010 Census figures. Retrieved March 23, 2011. Situat ...

, despite a clerical error in the spelling, is named after the battle. A New Hampshire historical marker there, number 118, commemorates the naming.

See also

* American Revolutionary War § War in the South. Places the Battle of Guilford Court House in overall sequence and strategic context. *Snow Camp Outdoor Theater

The Snow Camp Theatre is semi-professional theatre company in Snow Camp, an unincorporated community in southern Alamance County, North Carolina that brings the voices of the past into the hearts and minds of a modern audience from around the wo ...

which tells some of the story of the aftermath of the battle through the play ''The Sword of Peace'' by William Hardy.

References

Further reading

*Agniel, Lucien. ''The late affair has almost broke my heart;: The American Revolution in the South, 1780-1781'' Chatham Press, 1972, . *Babits, Lawrence E. and Howard, Joshua B. ''Long, Obstinate, and Bloody: The Battle of Guilford Courthouse'' University of North Carolina Press, 2009, *Baker, Thomas E. ''Another Such Victory: The Story of the American Defeat at Guilford Courthouse that Helped Win the War for Independence'' Eastern National, 1999, . *Chidsey, Donald Barr. ''The war in the South: The Carolinas and Georgia in the American Revolution'' Crown Publishers, 1971. Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London, . *Davis, Burke. ''The Cowpens-Guilford Courthouse Campaign'' University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002, . *Hairr, John. ''Guilford Courthouse'' Da Capo Press, 2002, . *Konstam, Angus. ''Guilford Courthouse 1781: Lord Cornwallis's Ruinous Victory'' Osprey Publishing, 2002, . *Lumpkin, Henry. ''From Savannah to Yorktown: The American Revolution in the South'' Paragon House, 1987, . *Rodgers, H.C.B. "the British Army in the 18th Century" George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1977 *Sawicki, James A. ''Infantry Regiments of the US Army.'' Dumfries, VA: Wyvern Publications, 1981. . *Showman, Richard K.; Conrad, Denis M.; Parks, Roger N. (editors). "The Papers of Nathanael Greene, Volume 7: 26 December 1780-29 March 1781." University of North Carolina Press. First Edition Printing (May 27, 1994). *Trevelyan, Sir George O. "George the Third and Charles Fox: The Concluding Part of The American Revolution". New York and elsewhere: Longmans, Green and Co., 1914 *Ward, Christopher. ''War of the Revolution'' (two volumes), MacMillan, New York, 1952External links

Guilford Courthouse National Military Park website

{{DEFAULTSORT:Battle Of Guilford Court House 1781 in the United States Conflicts in 1781 Guilford Court House Guilford Court House Guilford Court House Guilford Court House History of Greensboro, North Carolina 1781 in North Carolina