Battle of Cádiz (1702) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Cádiz, fought in August/September 1702, was an Anglo-Dutch attempt to seize the southern Spanish port of

Prince George, in his ship the ''Adventure'', had joined the fleet at

Prince George, in his ship the ''Adventure'', had joined the fleet at

The landing took place on 26 August in a fresh wind, resulting in the loss of some 25 landing craft, and 20 men drowned. Fire from a Spanish 4-gun battery, and a charge from a squadron of cavalry offered resistance to the landing. The foremost ranks of the Allied forces consisted of grenadiers who repulsed the Spanish horsemen. Nevertheless, one of the Allied officers, Colonel James Stanhope, who later became British commander-in-chief in Spain, praised the courage of the English and Spanish troops engaged in the small action, admitting that 200 more such horsemen would have spoiled the Allied descent.

From the landing place Ormonde's forces marched on Rota. The town was found deserted (although after a while the governor and some of the inhabitants returned to greet them). The Allies stayed here for two days, disembarking horses and stores. Although military power remained in Anglo-Dutch hands, Prince George had been granted the head of the civil administration in any town occupied by the Allies. He distributed manifestos calling on Spaniards to declare for the House of Austria; the fact that some came forward to join the Allies at Rota was of value, for the Imperial representative was dependent on local volunteers to make contact with other inhabitants. However, the Spanish authorities had taken severe measures to prevent desertion to the allied cause, threatening with hanging anyone caught in possession of one of Prince George's manifestos.Francis: ''The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713,'' p. 47

The Allies proceeded to take Fort Saint Catherine, before entering the town of Port Saint Mary. Ormonde's men initially encamped beyond the town, but the mistake was to allow them to return to it. The troops found the town full of unguarded warehouses stuffed full of goods, and the cellars full of wine and brandy, most of which was owned by English and Dutch merchants doing business under Spanish names. The men helped themselves, lost control, and fell to looting, destroying, and plundering, not just the warehouses, but also convents and churches.Francis: ''The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713,'' p. 48 Prince George despaired and sent home a report damning the conduct of the officers, particularly Ormonde's subordinates, Sir Henry Belasys (Ormonde's second-in-command), O’Hara, and the Dutch Baron Sparr, whom he held responsible for persuading Ormonde to quarter the troops in the town. The navy were not at first involved in the looting, but they were soon tempted to take their share.

The cause of Archduke Charles had suffered a serious setback due to the behaviour and misconduct of Ormonde's men, who, according to Trevelyan, plundered Saint Mary to 'the bare walls'. A local English merchant wrote disparagingly, "our fleet has left such a filthy stench among the Spaniards that a whole age will hardly blot it out." These excesses ended any hope that the local population would desert Philip V and join with the Allies, and were a boost to Bourbon propaganda. Rooke himself reported that, "the inhumane plundering of Port Saint Mary made a great noise here by sea and land, and will do so throughout Christendom."

The landing took place on 26 August in a fresh wind, resulting in the loss of some 25 landing craft, and 20 men drowned. Fire from a Spanish 4-gun battery, and a charge from a squadron of cavalry offered resistance to the landing. The foremost ranks of the Allied forces consisted of grenadiers who repulsed the Spanish horsemen. Nevertheless, one of the Allied officers, Colonel James Stanhope, who later became British commander-in-chief in Spain, praised the courage of the English and Spanish troops engaged in the small action, admitting that 200 more such horsemen would have spoiled the Allied descent.

From the landing place Ormonde's forces marched on Rota. The town was found deserted (although after a while the governor and some of the inhabitants returned to greet them). The Allies stayed here for two days, disembarking horses and stores. Although military power remained in Anglo-Dutch hands, Prince George had been granted the head of the civil administration in any town occupied by the Allies. He distributed manifestos calling on Spaniards to declare for the House of Austria; the fact that some came forward to join the Allies at Rota was of value, for the Imperial representative was dependent on local volunteers to make contact with other inhabitants. However, the Spanish authorities had taken severe measures to prevent desertion to the allied cause, threatening with hanging anyone caught in possession of one of Prince George's manifestos.Francis: ''The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713,'' p. 47

The Allies proceeded to take Fort Saint Catherine, before entering the town of Port Saint Mary. Ormonde's men initially encamped beyond the town, but the mistake was to allow them to return to it. The troops found the town full of unguarded warehouses stuffed full of goods, and the cellars full of wine and brandy, most of which was owned by English and Dutch merchants doing business under Spanish names. The men helped themselves, lost control, and fell to looting, destroying, and plundering, not just the warehouses, but also convents and churches.Francis: ''The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713,'' p. 48 Prince George despaired and sent home a report damning the conduct of the officers, particularly Ormonde's subordinates, Sir Henry Belasys (Ormonde's second-in-command), O’Hara, and the Dutch Baron Sparr, whom he held responsible for persuading Ormonde to quarter the troops in the town. The navy were not at first involved in the looting, but they were soon tempted to take their share.

The cause of Archduke Charles had suffered a serious setback due to the behaviour and misconduct of Ormonde's men, who, according to Trevelyan, plundered Saint Mary to 'the bare walls'. A local English merchant wrote disparagingly, "our fleet has left such a filthy stench among the Spaniards that a whole age will hardly blot it out." These excesses ended any hope that the local population would desert Philip V and join with the Allies, and were a boost to Bourbon propaganda. Rooke himself reported that, "the inhumane plundering of Port Saint Mary made a great noise here by sea and land, and will do so throughout Christendom."

Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

during the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

. The Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a ...

n city of Cádiz was the great European centre of the Spanish–American trade. The port's capture would not only help to sever Spain's links with her empire in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

, but it would also provide the Allies with a strategically important base from which the Anglo-Dutch fleets could control the western Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

.

The military build-up was accompanied by diplomatic measures in Portugal aimed at securing King Peter II for the Grand Alliance. The Allies also intended to garner support in Spain for an insurrection in the name of the Austrian pretender to the Spanish throne, the Archduke Charles

Archduke Charles Louis John Joseph Laurentius of Austria, Duke of Teschen (german: link=no, Erzherzog Karl Ludwig Johann Josef Lorenz von Österreich, Herzog von Teschen; 5 September 177130 April 1847) was an Austrian field-marshal, the third s ...

. The battle was the first of the war in the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

, but due to Allied intra-service rivalry, ill discipline, poor co-operation, and a skilful defence from the Marquis of Villadarias, Admiral George Rooke

Admiral of the Fleet Sir George Rooke (1650 – 24 January 1709) was an English naval officer. As a junior officer he saw action at the Battle of Solebay and again at the Battle of Schooneveld during the Third Anglo-Dutch War. As a captain, ...

was unable to complete his objective and, after a month, he set sail for home.

Background

On 15 May 1702 the Powers of the Grand Alliance, led by England and the Dutch Republic, declared war on France and Spain.Emperor Leopold I

Leopold I (Leopold Ignaz Joseph Balthasar Franz Felician; hu, I. Lipót; 9 June 1640 – 5 May 1705) was Holy Roman Emperor, King of Hungary, Croatia, and Bohemia. The second son of Ferdinand III, Holy Roman Emperor, by his first wife, Maria An ...

also declared war on the Bourbon powers, but his forces under Prince Eugene had already begun hostilities in northern Italy along the Po Valley

The Po Valley, Po Plain, Plain of the Po, or Padan Plain ( it, Pianura Padana , or ''Val Padana'') is a major geographical feature of Northern Italy. It extends approximately in an east-west direction, with an area of including its Venetic ex ...

in an attempt to secure for Austria the Spanish Duchy of Milan

The Duchy of Milan ( it, Ducato di Milano; lmo, Ducaa de Milan) was a state in northern Italy, created in 1395 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, then the lord of Milan, and a member of the important Visconti family, which had been ruling the city sin ...

. Eugene's successful 1701 campaign had aroused enthusiasm in England for war against France, and helped Emperor Leopold's efforts in persuading King William III

William III (William Henry; ; 4 November 16508 March 1702), also widely known as William of Orange, was the sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from the ...

to send an Allied fleet to the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

. Count Wratislaw, the Emperor's envoy in England, urged that the sight of an Allied fleet in the Mediterranean would effect a revolution in the Spanish province of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

; win south Italy from the precarious grip of Philip V Philip V may refer to:

* Philip V of Macedon (221–179 BC)

* Philip V of France (1293–1322)

* Philip II of Spain, also Philip V, Duke of Burgundy (1526–1598)

* Philip V of Spain

Philip V ( es, Felipe; 19 December 1683 – 9 July 1746) was ...

; overawe the Francophile Pope Clement XI; and encourage the Duke of Savoy

The titles of count, then of duke of Savoy are titles of nobility attached to the historical territory of Savoy. Since its creation, in the 11th century, the county was held by the House of Savoy. The County of Savoy was elevated to a Duchy of Sav ...

– and other Italian princes – to change sides.Trevelyan: ''England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim,'' p. 262 More modestly, Prince Eugene pleaded for a squadron to protect the passage of his supplies from Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into provi ...

across the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) ...

.

The English had their own interests in the Mediterranean: the Levant Company

The Levant Company was an English chartered company formed in 1592. Elizabeth I of England approved its initial charter on 11 September 1592 when the Venice Company (1583) and the Turkey Company (1581) merged, because their charters had expired, ...

needed escorts, and an Allied naval presence could challenge the dominance of King Louis’ Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

fleet, an attack on which could deliver a mortal blow to French naval power. It was clear, however, that before the Allies could commit to the Mediterranean strategy, it would first be necessary to secure a base in the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

. The decision to favour Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

– the capture of which would open the Straits

A strait is an oceanic landform connecting two seas or two other large areas of water. The surface water generally flows at the same elevation on both sides and through the strait in either direction. Most commonly, it is a narrow ocean chan ...

, and place in Allied hands the gate to the trade with the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

– was taken before the death of King William III in March 1702, but the policy was continued under his successor Queen Anne, and her ministers led by the Earl of Marlborough

Earl of Marlborough is a title that has been created twice, both times in the Peerage of England. The first time in 1626 in favour of James Ley, 1st Earl of Marlborough, James Ley, 1st Baron Ley and the second in 1689 for John Churchill, 1st Duke ...

.

England's representatives at the Portuguese court in Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Grande Lisboa, Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administr ...

, John Methuen and his son Paul

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

* Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chri ...

, were also clamouring for a strong naval demonstration on the Spanish coast to encourage the wavering King Peter II to annul his recent treaties with France and Spain, and join the Grand Alliance. The Methuens were assisted by Prince George of Hesse-Darmstadt

Prince George Louis of Hessen-Darmstadt (1669 – 13 September 1705) was a Field Marshal in the Austrian army. He is known for his career in Habsburg Spain, as Viceroy of Catalonia (1698–1701), head of the Austrian army in the War of the Span ...

, a cousin of the Empress Eleonora. The Allies hoped that whilst the Methuens negotiated with the Portuguese, the Prince could inspire and even direct the pro-Austrian insurrection in Spain on behalf of the Emperor's youngest son and pretender to the Spanish throne, the Archduke Charles

Archduke Charles Louis John Joseph Laurentius of Austria, Duke of Teschen (german: link=no, Erzherzog Karl Ludwig Johann Josef Lorenz von Österreich, Herzog von Teschen; 5 September 177130 April 1847) was an Austrian field-marshal, the third s ...

.

Prelude

The Anglo-Dutch fleet set sail at the end of July and passed down the Portuguese coast on 20 August. Admiral Rooke commanded 50 warships (30 English, 20 Dutch), and transports, totalling 160 sail in all; Ormonde, commander of the troops, had under him 14,000 men in total – 10,000 English (including 2,400 marines) and 4,000 Dutch. Yet Rooke had no faith in the expedition: his ships had insufficient victuals for a prolonged campaign, and he had concerns over the French port ofBrest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

which lay between himself and England.

Prince George, in his ship the ''Adventure'', had joined the fleet at

Prince George, in his ship the ''Adventure'', had joined the fleet at Cape St. Vincent

Cape St. Vincent ( pt, Cabo de São Vicente, ) is a headland in the municipality of Vila do Bispo, in the Algarve, southern Portugal. It is the southwesternmost point of Portugal and of mainland Europe.

History

Cape St. Vincent was already sacr ...

. Both the Prince and Paul Methuen (who had also joined the expedition), reported to Rooke that Cádiz was poorly defended, but the admiral's own intelligence, received from captured fisherman, suggested that a powerful garrison of Spanish regulars had already strengthened the city. Allied doubts about the real strength opposing them were exacerbated by the Spanish stratagem of lighting extensive fires along the heights. Therefore, after the Allied fleet anchored off Cádiz on 23 August, three days were spent in futile discussions before any decision was reached.

There were several options for the Allied attack. According to Rooke's journal of 25 August, Sir Stafford Fairborne:

… having proposed to the Admiral his forcing the harbour and destroying the eight French galleys which lay under the walls of Cádiz, he he Admiralcalled a council of flag officers to consider the same; but … it was unanimously judged unreasonable and impracticable to hazard any the least frigate on such an attempt.Churchill: ''Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, vol. ii,'' p. 610Another option for the Allies was to land the army under the cover of a bombardment by the fleet on the isthmus dividing Cádiz from the mainland; from there, the troops could storm the city. This tactic was Ormonde's preference, but Major-General Sir Charles O’Hara insisted that a landing on the isthmus was inadvisable unless the navy could guarantee the landing of supplies on a daily basis, which, because of the

lee shore

A lee shore, sometimes also called a leeward ( shore, or more commonly ), is a nautical term to describe a stretch of shoreline that is to the lee side of a vessel—meaning the wind is blowing towards land. Its opposite, the shore on the windward ...

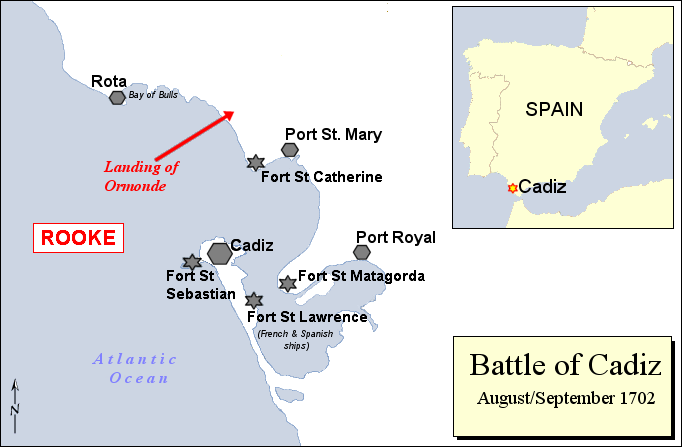

, they could not.Francis: ''The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713,'' p. 46 Ormonde's second choice was a blockade, supported by a bombardment of the town; but there was doubt that the ships could anchor close enough for an effective bombardment. In any case, Prince George objected to such a plan for fear of alienating the population. The decision, therefore, was to land the Allied troops between the Bay of Bulls and Fort Saint Catherine. This suited the navy because they could bring their ships near to the shore, and from the beachhead troops could seize the towns of Rota and Port Saint Mary. However, the landing place was a long way from the base of the isthmus on which Cádiz stood. (''See map below'').

Don Francisco del Castillo, Marquis of Villadarias, was given command in the threatened province of Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a ...

. Cádiz, Andalusia's main city, held a garrison of some 300 poorly equipped men with a similar number lining the shore, but the sudden appearance of the Allied fleet engendered a state of emergency, and, in Philip Stanhope's words, ‘the spirit and determination to repel it’. The wealthy cities of Cordova and Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

contributed to the Spanish cause, the nobles took up arms, and the local peasantry were organised into battalions, so that after boosting the city's garrison Villadarias could still muster in the field five or six hundred good horsemen, and several thousand militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

. To increase the strength of his position further, the Spanish commander secured the harbour by drawing a strong boom and sinking two large hulks across its entrance.

Battle

Landing and looting

Re-embarkation

The immediate effects of the looting were detrimental to the expedition; the army thought mainly of taking their spoils home and, according to David Francis, lost their combative spirit.Francis: ''The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713,'' p. 50 For their part, the navy feared for the ships anchored off a lee shore, which in bad weather was dangerous. Nevertheless, the army's long march from the landing place to their objective required assistance from the men in Rooke's fleet. Crew members built bridges, cutfascine

A fascine is a rough bundle of brushwood or other material used for strengthening an earthen structure, or making a path across uneven or wet terrain. Typical uses are protecting the banks of streams from erosion, covering marshy ground and so ...

s, dug trenches, fetched and carried, but, due to sickness, there was never enough labour available. Rooke was eventually obliged to limit these onerous demands on his sailors, declaring that "such slavish labour was not for seamen." The admiral may have had no choice, but it was a blow to army–navy relations.Francis: ''The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713,'' p. 51

After the occupation of Port Saint Mary the advance lost momentum. The marshy coast as far as Port Royal was occupied, and the English generals became more recalcitrant. However, Baron Sparr insisted on attacking Fort Matagorda situated on the Puntales (a sandy spit near the entrance to the inner harbour), thus enabling the entry of Rooke's fleet into the anchorage, before destroying the enemy ships within.Trevelyan: ''England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim,'' p. 266 With 600 Dutch and 1,600 English troops, the Allies made a causeway across the deep sand and brought a battery close to the stronghold, but they now found themselves within range of the Franco-Spanish ships anchored behind the boom – commanded by Conde de Fernan Núñez – and in a vulnerable position; they were also subject to attack from the galley

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard (clearance between sea and gunwale). Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be used ...

s which still lurked outside the harbour.

Villadarias, meanwhile, continued to harass detached Allied parties and cut off their communications; by a sudden attack he also recaptured Rota whose garrison commander, the former governor, was condemned to death and executed as a traitor. The Allies made little or no progress. Matagorda held out, and after several days Rooke declared that even if the fort was taken, the other stronghold guarding the Puntales entrance would prevent the fleet from navigating the narrow passage. On the 26 September, therefore, facing certain failure, the decision was taken to re-embark the troops. A plan to bombard the city (against Prince George's wishes) was abandoned due to bad weather, and, after a further council of war, the fleet left on 30 September. The attempt to seize Cádiz had ended in abject failure.

Aftermath

The fact that no Spanish notables had joined the Allies during their time at Cádiz meant a loss of prestige for Prince George; but he did receive aboard his ship a deputation of Spanish grandees from Madrid which had missed him in Lisbon, and had been ferried over from Faro. The Prince informed Rooke and Ormonde that they were ready to declare for the House of Austria, but they were not prepared to commit themselves unless the Allies could guarantee them adequate support, and leave a force to winter in Spain. This assistance was not forthcoming. There had, however, already been a number of Castilian defections, the most startling of which was that of the Admiral of Castile, Juan de Cabrera, Duke of Rioseco and Count of Melgar. After leavingMadrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

on 13 September 1702, he fled to Portugal where he issued a denunciation of the Bourbon government and entered the service of the Archduke Charles.

Ormonde and Prince George wanted to land at another key place in Spain but Rooke, concerned about the autumnal gales, decided to head for England. By now Ormonde and Rooke were barely on speaking terms: the general thought he could have taken Cádiz were it not for Rooke vetoing his plan; for his part, the admiral had written bitterly to Ormonde regarding the behaviour of the soldiers on shore. However, it was fortunate for Rooke, Ormonde, and the Allied cause, that news of a Spanish silver fleet from America had arrived off the coast of Galicia. The subsequent Battle of Vigo Bay was considerably more successful than the attempt on Cádiz (although the financial rewards were far less than expected), and the victory had taken the edge off the failed expedition. Nevertheless, when the fleet returned to England the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

insisted on an inquiry into the conduct of the Allies at Cádiz.

The bad feeling between Rooke and Ormonde had led to hopes of a fruitful inquiry, but the success at Vigo had given the Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

the opportunity to build up Rooke as a hero; Ormonde was also given a triumphal reception and rallied to the Tory side. The inquiry, therefore, became a party struggle: the Tories glorifying Rooke and Ormonde, whilst the Whigs remained critical. The two Allied commanders made an obdurate joint defence before the House of Lord's Committee.Churchill: ''Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, vol. ii,'' p. 612 However, a Court-Martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

was held into the conduct of Belasys and O’Hara. O’Hara was cleared but Belasys was dismissed from the service. Both men were expected to lose their regiments, yet Belasys was later reinstated, and O’Hara was promoted to lieutenant-general in 1704.

Notes

References

*Churchill, Winston

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from 1 ...

. '' Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, vol. ii''. University of Chicago Press, (2002).

*Francis, David. ''The First Peninsular War: 1702–1713.'' Ernest Benn Limited, (1975).

*Kamen, Henry. ''The War of Succession in Spain: 1700–15.'' Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

*Roger, N.A.M. ''The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649–1815.'' Penguin Group, (2006).

* Stanhope, Philip. ''History of the War of the Succession in Spain.'' London, (1836)

* Trevelyan, G. M. ''England Under Queen Anne: Blenheim.'' Longmans, Green and co., (1948).

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cadiz, Battle of 1702

Conflicts in 1702

1702 in Europe

Battles involving Spain

Battles involving the Dutch Republic

Battles involving England

Sieges involving Spain

Battles of the War of the Spanish Succession

Battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

1702 in Spain

1702 in the British Empire