Battle of Biccoca on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Bicocca or La Bicocca ( it, Battaglia della Bicocca) was fought on 27 April 1522, during the

The Swiss came to a sudden halt as the columns reached the sunken road in front of the park; the depth of the road and the height of the rampart behind it—together higher than the length of the Swiss pikes—effectively blocked their advance. Moving down into the road, the Swiss suffered massive casualties from the fire of d'Avalos's arquebusiers. Nevertheless, the Swiss made a series of desperate attempts to breach the Imperial line; some managed to reach the top of the rampart, only to be met by the landsknechts, who had come up from behind the arquebusiers. One of the Swiss captains was apparently killed by Frundsberg in single combat; and the Swiss, unable to form up atop the earthworks, were pushed back down into the sunken road.

After attempting to move forward for about half an hour, the remnants of the Swiss columns retreated back towards the main French line Their total losses numbered more than 3,000, and included Winkelried, von Stein, and twenty other captains; of the French nobles who had accompanied them, only Montmorency survived.

The Swiss came to a sudden halt as the columns reached the sunken road in front of the park; the depth of the road and the height of the rampart behind it—together higher than the length of the Swiss pikes—effectively blocked their advance. Moving down into the road, the Swiss suffered massive casualties from the fire of d'Avalos's arquebusiers. Nevertheless, the Swiss made a series of desperate attempts to breach the Imperial line; some managed to reach the top of the rampart, only to be met by the landsknechts, who had come up from behind the arquebusiers. One of the Swiss captains was apparently killed by Frundsberg in single combat; and the Swiss, unable to form up atop the earthworks, were pushed back down into the sunken road.

After attempting to move forward for about half an hour, the remnants of the Swiss columns retreated back towards the main French line Their total losses numbered more than 3,000, and included Winkelried, von Stein, and twenty other captains; of the French nobles who had accompanied them, only Montmorency survived.

Italian War of 1521–26

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

. A combined French and Venetian force under Odet de Foix, Vicomte de Lautrec

Odet de Foix, Vicomte de Lautrec (1485 – 15 August 1528) was a French military leader. As Marshal of France, he commanded the campaign to conquer Naples, but died from the bubonic plague in 1528.

Biography

Odet was the son of Jean de Foix ...

, was decisively defeated by an Imperial–Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

and Papal army under the overall command of Prospero Colonna

Prospero Colonna (1452–1523), sometimes referred to as Prosper Colonna, was an Italian condottiero in the service of the Papal States, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Kingdom of Spain during the Italian Wars.

Biography

A member of the ancient ...

. Lautrec then withdrew from Lombardy, leaving the Duchy of Milan in Imperial hands.

Having been driven from Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

by an Imperial advance in late 1521, Lautrec had regrouped, attempting to strike at Colonna's lines of communication. When the Swiss mercenaries

The Swiss mercenaries (german: Reisläufer) were a powerful infantry force constituted by professional soldiers originating from the cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy. They were notable for their service in foreign armies, especially among t ...

in French service did not receive their pay, however, they demanded an immediate battle, and Lautrec was forced to attack Colonna's fortified position in the park of the Arcimboldi Villa Bicocca, north of Milan. The Swiss pikemen advanced over open fields under heavy artillery fire to assault the Imperial positions, but were halted at a sunken road backed by earthworks. Having suffered massive casualties from the fire of Spanish arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbus ...

iers, the Swiss retreated. Meanwhile, an attempt by French cavalry to flank Colonna's position proved equally ineffective. The Swiss, unwilling to fight further, marched off to their cantons a few days later, and Lautrec retreated into Venetian territory with the remnants of his army.

The battle is noted chiefly for marking the end of the Swiss dominance among the infantry of the Italian Wars

The Italian Wars, also known as the Habsburg–Valois Wars, were a series of conflicts covering the period 1494 to 1559, fought mostly in the Italian peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and the Mediterranean Sea. The pr ...

, and of the Swiss method of assaults by massed columns of pikemen without support from other troops. It was also one of the first engagements in which firearms played a decisive role on the battlefield.

Prelude

At the start of the war in 1521, Holy Roman EmperorCharles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infa ...

and Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X ( it, Leone X; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political an ...

moved jointly against the Duchy of Milan, the principal French possession in Lombardy. A large Papal force under Federico II Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua

Federico II of Gonzaga (17 May 1500 – 28 August 1540) was the ruler of the Italian city of Mantua (first as Marquis, later as Duke) from 1519 until his death. He was also Marquis of Montferrat from 1536.

Biography

Federico was son of Francesco ...

, together with Spanish troops from Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

and some smaller Italian contingents, concentrated near Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and '' comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture. In 2017, it was named as the Eur ...

. The German forces which Charles sent south to aid this venture passed through Venetian territory near Valeggio unmolested; the combined Papal, Spanish, and Imperial army then proceeded into French territory under the command of Prospero Colonna

Prospero Colonna (1452–1523), sometimes referred to as Prosper Colonna, was an Italian condottiero in the service of the Papal States, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Kingdom of Spain during the Italian Wars.

Biography

A member of the ancient ...

. For the next several months, Colonna fought an evasive war of maneuver against the French, besieging cities but refusing to give battle.

By the autumn of 1521, Lautrec, who was holding a line along the Adda river to Cremona, began to suffer massive losses from desertion, particularly among his Swiss mercenaries

The Swiss mercenaries (german: Reisläufer) were a powerful infantry force constituted by professional soldiers originating from the cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy. They were notable for their service in foreign armies, especially among t ...

. Colonna took the opportunity this offered and, advancing close to the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Swi ...

, crossed the Adda at Vaprio; Lautrec, lacking infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

and assuming the year's campaign to be over, withdrew to Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

. Colonna, however, had no intention of stopping his advance; in late November, he launched a surprise attack on the city, overwhelming the Venetian troops defending one of the walls. Following some abortive street-fighting

Street fighting is hand-to-hand combat in public places, between individuals or groups of people. The venue is usually a public place (e.g. a street) and the fight sometimes results in serious injury or occasionally even death. Some street fig ...

, Lautrec withdrew to Cremona with about 12,000 men.

By January 1522, the French had lost Alessandria, Pavia

Pavia (, , , ; la, Ticinum; Medieval Latin: ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy in northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino river near its confluence with the Po. It has a population of c. 73,086. The city was the cap ...

, and Como

Como (, ; lmo, Còmm, label= Comasco , or ; lat, Novum Comum; rm, Com; french: Côme) is a city and ''comune'' in Lombardy, Italy. It is the administrative capital of the Province of Como.

Its proximity to Lake Como and to the Alps h ...

; and Francesco II Sforza, bringing further German reinforcements, had slipped past a Venetian force at Bergamo to join Colonna in Milan. Lautrec had meanwhile been reinforced by the arrival of 16,000 fresh Swiss pikemen

A pike is a very long thrusting spear formerly used in European warfare from the Late Middle Ages and most of the Early Modern Period, and were wielded by foot soldiers deployed in pike square formation, until it was largely replaced by bayon ...

and some further Venetian forces, as well as additional companies of French troops under the command of Thomas de Foix-Lescun and Pedro Navarro

Pedro Navarro, Count of Oliveto (c. 1460 – 28 August 1528) was a Navarrese military engineer and general who participated in the War of the League of Cambrai. At the Battle of Ravenna in 1512 he commanded the Spanish and Papal infantry, but w ...

; he had also secured the services of the condottiere

''Condottieri'' (; singular ''condottiero'' or ''condottiere'') were Italian captains in command of mercenary companies during the Middle Ages and of multinational armies during the early modern period. They notably served popes and other Europ ...

Giovanni de' Medici, who brought his Black Bands into the French service. The French proceeded to attack Novara

Novara (, Novarese: ) is the capital city of the province of Novara in the Piedmont region in northwest Italy, to the west of Milan. With 101,916 inhabitants (on 1 January 2021), it is the second most populous city in Piedmont after Turin. It i ...

and Pavia

Pavia (, , , ; la, Ticinum; Medieval Latin: ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy in northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino river near its confluence with the Po. It has a population of c. 73,086. The city was the cap ...

, hoping to draw Colonna into a decisive battle. Colonna, leaving Milan, fortified himself in the monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone ( hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer whi ...

of Certosa south of the city. Considering this position to be too strong to be easily assaulted, Lautrec attempted instead to threaten Colonna's lines of communication by sweeping around Milan to Monza, cutting the roads from the city into the Alps.

Lautrec was suddenly confronted, however, with the intransigence of the Swiss, who formed the largest contingent of the French army. The Swiss complained that they had not received any of the pay promised them since their arrival in Lombardy, and their captains, led by Albert von Stein, demanded that Lautrec attack the Imperial army immediately—else the mercenaries would abandon the French and return to their cantons. Lautrec reluctantly acquiesced and marched south towards Milan.

Battle

Dispositions

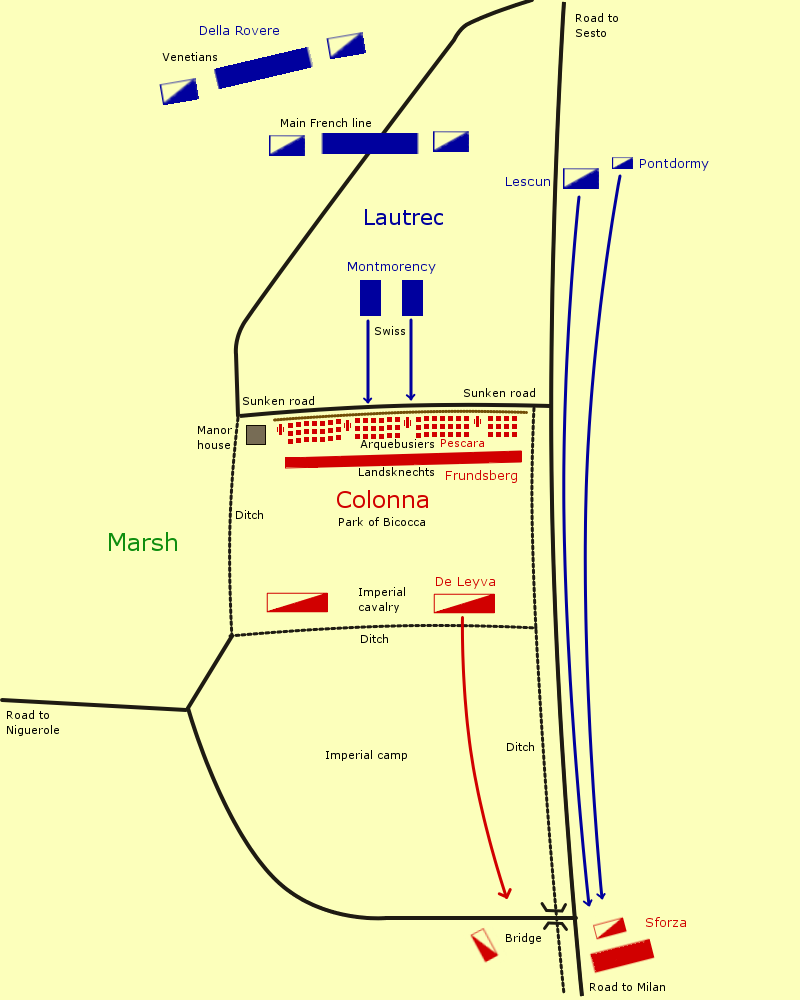

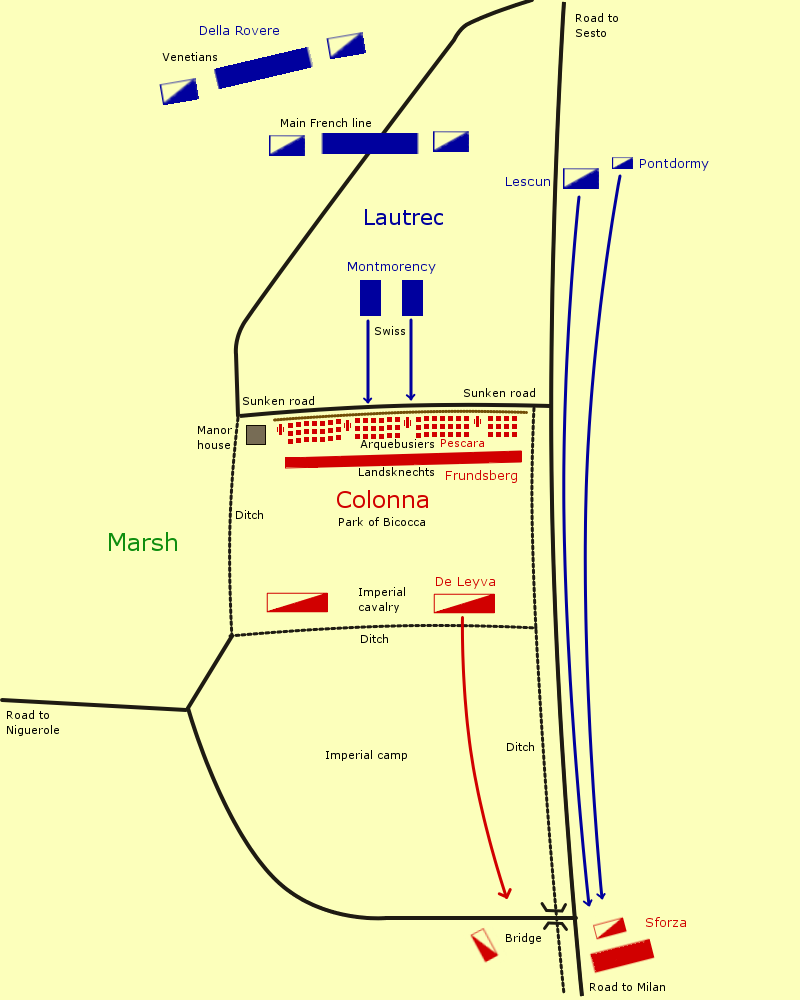

Colonna had meanwhile relocated to a formidable new position: the manor park of Bicocca, about four miles (6 km) north of Milan. The park was situated between a large expanse of marshy ground to the west and the main road into Milan to the east; along this road ran a deep wet ditch, which was crossed by a narrow stone bridge some distance south of the park. The north side of the park was bordered by a sunken road, which Colonna deepened, constructing an earthen rampart on the southern bank. The entire length of the north side of the park was less than , allowing Colonna to place his troops quite densely; immediately behind the rampart were four ranks of Spanisharquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbus ...

iers, commanded by Fernando d'Ávalos, and behind them were blocks of Spanish pikemen

A pike is a very long thrusting spear formerly used in European warfare from the Late Middle Ages and most of the Early Modern Period, and were wielded by foot soldiers deployed in pike square formation, until it was largely replaced by bayon ...

and German landsknechts

The (singular: , ), also rendered as Landsknechts or Lansquenets, were Germanic mercenaries used in pike and shot formations during the early modern period. Consisting predominantly of pikemen and supporting foot soldiers, their front line wa ...

under Georg Frundsberg

Georg von Frundsberg (24 September 1473 – 20 August 1528) was a German military and Landsknecht leader in the service of the Holy Roman Empire and Imperial House of Habsburg. An early modern proponent of infantry tactics, he established ...

. The Imperial artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

, placed on several platforms jutting forward from the earthworks, was able to sweep the fields north of the park as well as parts of the sunken road itself. Most of the Imperial cavalry was placed at the south end of the park, far behind the infantry; a separate force of cavalry was positioned to the south, guarding the bridge.

On the evening of 26 April, Lautrec sent a force under the Sieur de Pontdormy to reconnoiter the Imperial positions. Colonna, having observed the French presence, sent messengers to Milan to request reinforcements; Sforza arrived the next morning with 6,400 additional troops, joining the cavalry near the bridge to the south of Colonna's camp.

At dawn on 27 April, Lautrec began his attack, sending the Black Bands to push aside the Spanish pickets and clear the ground before the Imperial positions. The French advance was headed by two columns of Swiss, each comprising about 4,000 to 7,000 men, accompanied by some artillery; this party was to assault the entrenched front of the Imperial camp directly. Lescun, meanwhile, led a body of cavalry south along the Milan road, intending to flank the camp and strike at the bridge to the rear. The remainder of the French army, including the French infantry, the bulk of the heavy cavalry, and the remnants of the Swiss, formed up in a broad line some distance behind the two Swiss columns; behind this was a third line, composed of the Venetian forces under Francesco Maria della Rovere, the Duke of Urbino.

The Swiss attack

The overall command of the Swiss assault was given to Anne de Montmorency. As the Swiss columns advanced towards the park, he ordered them to pause and wait for the French artillery to bombard the Imperial defences, but the Swiss refused to obey. Perhaps the Swiss captains doubted that the artillery would have any effect on the earthworks; historianCharles Oman

Sir Charles William Chadwick Oman, (12 January 1860 – 23 June 1946) was a British military historian. His reconstructions of medieval battles from the fragmentary and distorted accounts left by chroniclers were pioneering. Occasionally his ...

suggests that it is more likely they were "inspired by blind pugnacity and self-confidence". In any case, the Swiss moved rapidly towards Colonna's position, leaving the artillery behind; there was apparently some rivalry between the two columns, as one, commanded by Arnold Winkelried of Unterwalden, was composed of men from the rural cantons, while the other, under Albert von Stein, consisted of the contingents from Bern and the urban cantons. The advancing Swiss quickly came into range of the Imperial artillery; unable to take cover on the level fields, they began to take substantial casualties, and as many as a thousand Swiss may have been killed by the time the columns reached the Imperial lines.

The Swiss came to a sudden halt as the columns reached the sunken road in front of the park; the depth of the road and the height of the rampart behind it—together higher than the length of the Swiss pikes—effectively blocked their advance. Moving down into the road, the Swiss suffered massive casualties from the fire of d'Avalos's arquebusiers. Nevertheless, the Swiss made a series of desperate attempts to breach the Imperial line; some managed to reach the top of the rampart, only to be met by the landsknechts, who had come up from behind the arquebusiers. One of the Swiss captains was apparently killed by Frundsberg in single combat; and the Swiss, unable to form up atop the earthworks, were pushed back down into the sunken road.

After attempting to move forward for about half an hour, the remnants of the Swiss columns retreated back towards the main French line Their total losses numbered more than 3,000, and included Winkelried, von Stein, and twenty other captains; of the French nobles who had accompanied them, only Montmorency survived.

The Swiss came to a sudden halt as the columns reached the sunken road in front of the park; the depth of the road and the height of the rampart behind it—together higher than the length of the Swiss pikes—effectively blocked their advance. Moving down into the road, the Swiss suffered massive casualties from the fire of d'Avalos's arquebusiers. Nevertheless, the Swiss made a series of desperate attempts to breach the Imperial line; some managed to reach the top of the rampart, only to be met by the landsknechts, who had come up from behind the arquebusiers. One of the Swiss captains was apparently killed by Frundsberg in single combat; and the Swiss, unable to form up atop the earthworks, were pushed back down into the sunken road.

After attempting to move forward for about half an hour, the remnants of the Swiss columns retreated back towards the main French line Their total losses numbered more than 3,000, and included Winkelried, von Stein, and twenty other captains; of the French nobles who had accompanied them, only Montmorency survived.

Denouement

Lescun, with about 400 heavy cavalry under his command, had meanwhile reached the bridge south of the park and fought his way across it and into the Imperial camp beyond. Colonna responded by detaching some cavalry underAntonio de Leyva

Antonio de Leyva, Duke of Terranova, Prince of Ascoli, Count of Monza (1480–1536) was a Spanish general during the Italian Wars. During the Italian War of 1521, he commanded Pavia during the siege of the city by Francis I of France, and took ...

to halt the French advance, while Sforza came up the road towards the bridge, aiming to surround Lescun. Pontdormy held off the Milanese, allowing Lescun to extricate himself from the camp; the French cavalry then retraced its path and rejoined the main body of the army.

Despite the urging of d'Avalos and several other Imperial commanders, Colonna refused to order a general attack on the French, pointing out that much of Lautrec's army—including his cavalry—was still intact. Colonna suggested that the French were already beaten, and would soon withdraw; this assessment was shared by Frundsberg. Nevertheless, some small groups of Spanish arquebusiers and light cavalry attempted to pursue the withdrawing Swiss, only to be beaten back by the Black Bands, which were covering the removal of the French artillery from the field.

Colonna's judgement proved to be accurate; the Swiss were unwilling to make another assault, and marched for home on 30 April. Lautrec, believing that his resulting weakness in infantry made a further campaign impossible, retreated to the east, crossing the Adda into Venetian territory at Trezzo sull'Adda, Trezzo. Having reached Cremona, Lautrec departed for France, leaving Lescun in command of the remnants of the French army.

Aftermath

Lautrec's departure heralded a complete collapse of the French position in northern Italy. No longer menaced by the French army, Colonna and d'Avalos marched on Genoa, capturing it after a Siege of Genoa (1522), brief siege. Lescun, learning of the loss of Genoa, arranged an agreement with Sforza by which the Castello Sforzesco in Milan, which still remained in French hands, surrendered, and the remainder of the French forces withdrew over theAlps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Swi ...

. The Venetians, under the newly elected Doge of Venice, Doge Andrea Gritti, were no longer interested in continuing the war; in July 1523, Gritti concluded the Treaty of Worms with Charles V, removing the Republic from the fighting. The French would make two further attempts to regain Lombardy before the end of the war, but neither would be successful; the terms of the Treaty of Madrid (1526), Treaty of Madrid, which Francis I of France, Francis was forced to sign after his defeat at the Battle of Pavia, would leave Italy in Imperial hands.

Another effect of the battle was the changed attitude of the Swiss. Francesco Guicciardini wrote of the aftermath of Bicocca: They went back to their mountains diminished in numbers, but much more diminished in audacity; for it is certain that the losses which they suffered at Bicocca so affected them that in the coming years they no longer displayed their wonted vigour.While Swiss mercenaries would continue to take part in the

Italian Wars

The Italian Wars, also known as the Habsburg–Valois Wars, were a series of conflicts covering the period 1494 to 1559, fought mostly in the Italian peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and the Mediterranean Sea. The pr ...

, they no longer possessed the willingness to make headlong attacks that they had at Battle of Novara (1513), Novara in 1513 or Battle of Marignano, Marignano in 1515; their performance at the Battle of Pavia in 1525 would surprise observers by its lack of initiative.

More generally, the battle made apparent the decisive role of small arms on the battlefield. Although the full capabilities of the arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbus ...

would not be demonstrated until the Battle of the Sesia (where arquebusiers would prevail against heavy cavalry on open ground) two years later, the weapon nevertheless became a ''sine qua non'' for any army which did not wish to grant a massive advantage to its opponents. While the pikeman would continue to play a vital role in warfare, it would be equal to that of the arquebusier; together, the two types of infantry would be combined into the so-called "pike and shot" units that would endure until the development of the bayonet at the end of the seventeenth century. The offensive doctrine of the Swiss—a "push of pike" unsupported by firearms—had become obsolete, and offensive doctrines in general were increasingly replaced with defensive ones; the combination of the arquebus and effective field fortification had made frontal assaults on entrenched positions too costly to be practical, and they were not attempted again for the duration of the Italian Wars.

As a result of the battle, the word ''bicoca''—meaning a bargain, or something acquired at little cost—entered the Spanish language.Rodríguez Hernández, "Spanish Imperial Wars", 293.

Notes

References

* Arfaioli, Maurizio. ''The Black Bands of Giovanni: Infantry and Diplomacy During the Italian Wars (1526–1528)''. Pisa: Pisa University Press, Edizioni Plus, 2005. . * Jeremy Black (historian), Black, Jeremy. "Dynasty Forged by Fire." ''MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History'' 18, no. 3 (Spring 2006): 34–43. . * Wim Blockmans, Blockmans, Wim. ''Emperor Charles V, 1500–1558''. Translated by Isola van den Hoven-Vardon. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. . * Clodfelter, Micheal. ''Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015''. 4th ed. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2017. . * Francesco Guicciardini, Guicciardini, Francesco. ''The History of Italy''. Translated by Sydney Alexander. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984. . * Hall, Bert. ''Weapons and Warfare in Renaissance Europe: Gunpowder, Technology, and Tactics''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. . * Robert Knecht, Knecht, Robert J. ''Renaissance Warrior and Patron: The Reign of Francis I''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994. . * John Julius Norwich, Norwich, John Julius. ''A History of Venice''. New York: Vintage Books, 1989. . * Mallett, Michael and Christine Shaw. ''The Italian Wars, 1494–1559: War, State and Society in Early Modern Europe''. Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited, 2012. . * Charles Oman, Oman, Charles. ''A History of the Art of War in the Sixteenth Century''. London: Methuen & Co., 1937. * Rodríguez Hernández, Antonio José. "The Spanish Imperial Wars of the 16th Century". In ''War in the Iberian Peninsula, 700–1600'', edited by Francisco García Fitz and João Gouveia Monteiro, 267–299. New York: Routledge, 2018. . * Taylor, Frederick Lewis. ''The Art of War in Italy, 1494–1529''. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1973. . {{DEFAULTSORT:Bicocca (1522), Battle of 1522 in Italy Battles involving France Battles involving the Holy Roman Empire Battles involving Spain Battles involving the Duchy of Milan Battles involving the Papal States Battles involving the Republic of Venice Battles of the Italian Wars Battles in Lombardy Conflicts in 1522