Baryonyx on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Baryonyx'' () is a

In January 1983, the British plumber and amateur

In January 1983, the British plumber and amateur

In 2011, a specimen (Catalogued as ML1190 in

In 2011, a specimen (Catalogued as ML1190 in

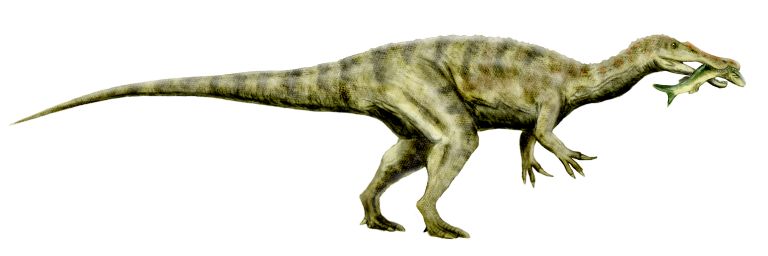

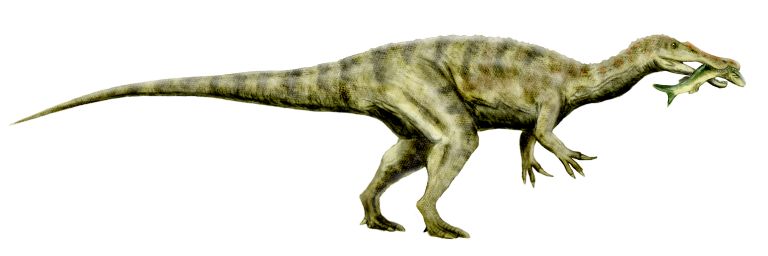

''Baryonyx'' is estimated to have been between long, in hip height, and to have weighed between . The fact that elements of the skull and

''Baryonyx'' is estimated to have been between long, in hip height, and to have weighed between . The fact that elements of the skull and

''Baryonyx'' had a rudimentary , similar to crocodiles but unlike most theropod dinosaurs. A rugose (roughly wrinkled) surface suggests the presence of a horny pad in the roof of the mouth. The nasal bones were fused, which distinguished ''Baryonyx'' from other spinosaurids, and a

''Baryonyx'' had a rudimentary , similar to crocodiles but unlike most theropod dinosaurs. A rugose (roughly wrinkled) surface suggests the presence of a horny pad in the roof of the mouth. The nasal bones were fused, which distinguished ''Baryonyx'' from other spinosaurids, and a  Most of the teeth found with the holotype specimen were not in articulation with the skull; a few remained in the upper jaw, and only small replacement teeth were still borne by the lower jaw. The teeth had the shape of recurved cones, where slightly flattened from sideways, and their curvature was almost uniform. The roots were very long, and tapered towards their extremity. The carinae (sharp front and back edges) of the teeth were finely serrated with denticles on the front and back, and extended all along the crown. There were around six to eight denticles per mm (0.039 in), a much larger number than in large-bodied theropods like '' Torvosaurus'' and ''

Most of the teeth found with the holotype specimen were not in articulation with the skull; a few remained in the upper jaw, and only small replacement teeth were still borne by the lower jaw. The teeth had the shape of recurved cones, where slightly flattened from sideways, and their curvature was almost uniform. The roots were very long, and tapered towards their extremity. The carinae (sharp front and back edges) of the teeth were finely serrated with denticles on the front and back, and extended all along the crown. There were around six to eight denticles per mm (0.039 in), a much larger number than in large-bodied theropods like '' Torvosaurus'' and ''

In their original description, Charig and Milner found ''Baryonyx'' unique enough to warrant a new family of theropod dinosaurs: Baryonychidae. They found ''Baryonyx'' to be unlike any other theropod group, and considered the possibility that it was a thecodont (a grouping of early archosaurs now considered unnatural), due to having apparently primitive features, but noted that the articulation of the maxilla and premaxilla was similar to that in ''Dilophosaurus''. They also noted that the two snouts from Niger (which later became the basis of ''Cristatusaurus''), assigned to the family Spinosauridae by Taquet in 1984, appeared almost identical to that of ''Baryonyx'' and they referred them to Baryonychidae instead. In 1988, the American palaeontologist Gregory S. Paul agreed with Taquet that ''Spinosaurus'', described in 1915 based on fragmentary remains from Egypt that were destroyed in

In their original description, Charig and Milner found ''Baryonyx'' unique enough to warrant a new family of theropod dinosaurs: Baryonychidae. They found ''Baryonyx'' to be unlike any other theropod group, and considered the possibility that it was a thecodont (a grouping of early archosaurs now considered unnatural), due to having apparently primitive features, but noted that the articulation of the maxilla and premaxilla was similar to that in ''Dilophosaurus''. They also noted that the two snouts from Niger (which later became the basis of ''Cristatusaurus''), assigned to the family Spinosauridae by Taquet in 1984, appeared almost identical to that of ''Baryonyx'' and they referred them to Baryonychidae instead. In 1988, the American palaeontologist Gregory S. Paul agreed with Taquet that ''Spinosaurus'', described in 1915 based on fragmentary remains from Egypt that were destroyed in

Spinosaurids appear to have been widespread from the

Spinosaurids appear to have been widespread from the

/ref> Sereno and colleagues proposed in 1998 that the large thumb-claw and robust forelimbs of spinosaurids evolved in the Middle Jurassic, before the elongation of the skull and other adaptations related to fish-eating, since the former features are shared with their megalosaurid relatives. They also suggested that the spinosaurines and baryonychines diverged before the Barremian age of the Early Cretaceous. Several theories have been proposed about the

In their original description, Charig and Milner did not consider ''Baryonyx'' to be aquatic (due to its nostrils being on the sides of its snout—far from the tip—and the form of the post-cranial skeleton), but thought it was capable of swimming, like most land vertebrates. They speculated that the elongated skull, long neck, and strong humerus of ''Baryonyx'' indicated that the animal was a facultative

In their original description, Charig and Milner did not consider ''Baryonyx'' to be aquatic (due to its nostrils being on the sides of its snout—far from the tip—and the form of the post-cranial skeleton), but thought it was capable of swimming, like most land vertebrates. They speculated that the elongated skull, long neck, and strong humerus of ''Baryonyx'' indicated that the animal was a facultative  A 2010 study by the French palaeontologist Romain Amiot and colleagues proposed that spinosaurids were

A 2010 study by the French palaeontologist Romain Amiot and colleagues proposed that spinosaurids were

The Weald Clay Formation consists of sediments of

The Weald Clay Formation consists of sediments of  Other dinosaurs from the Wessex Formation of the Isle of Wight where ''Baryonyx'' may have occurred include the theropods ''Riparovenator'', ''Ceratosuchops'', ''

Other dinosaurs from the Wessex Formation of the Isle of Wight where ''Baryonyx'' may have occurred include the theropods ''Riparovenator'', ''Ceratosuchops'', ''

Charig and Milner presented a possible scenario explaining the

Charig and Milner presented a possible scenario explaining the

Natural History Museum – "''Baryonyx'': the discovery of an amazing fish-eating dinosaur"

– four minute video presented by Angela C. Milner {{Academic peer reviewed, Q63252951 Spinosaurids Monotypic dinosaur genera Barremian life Early Cretaceous dinosaurs of Europe Cretaceous England Fossils of England Fossil taxa described in 1986 Taxa named by Alan J. Charig Taxa named by Angela Milner Articles containing video clips

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

of theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

which lived in the Barremian

The Barremian is an age in the geologic timescale (or a chronostratigraphic stage) between 129.4 ± 1.5 Ma (million years ago) and 121.4 ± 1.0 Ma). It is a subdivision of the Early Cretaceous Epoch (or Lower Cretaceous Series). It is preceded ...

stage of the Early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous (geochronology, geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous (chronostratigraphy, chronostratigraphic name), is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 145& ...

period, about 130–125 million years ago. The first skeleton was discovered in 1983 in the Smokejack Clay Pit

Smokejack Clay Pit is a geological Site of Special Scientific Interest east of Cranleigh in Surrey. It is a Geological Conservation Review site.

This site exposes Lower Cretaceous rocks of the Weald Clay Group. Fossils of six orders of insects h ...

, of Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant ur ...

, England, in sediments of the Weald Clay Formation

Weald Clay or the Weald Clay Formation is a Lower Cretaceous sedimentary rock unit underlying areas of South East England, between the North and South Downs, in an area called the Weald Basin. It is the uppermost unit of the Wealden Group of ...

, and became the holotype specimen

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of sever ...

of ''Baryonyx walkeri'', named by palaeontologists

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of foss ...

Alan J. Charig

Alan Jack Charig (1 July 1927 – 15 July 1997) was an English palaeontologist and writer who popularised his subject on television and in books at the start of the wave of interest in dinosaurs in the 1970s.

Charig was, though, first and fo ...

and Angela C. Milner in 1986

The year 1986 was designated as the International Year of Peace by the United Nations.

Events January

* January 1

** Aruba gains increased autonomy from the Netherlands by separating from the Netherlands Antilles.

**Spain and Portugal en ...

. The generic name, ''Baryonyx'', means "heavy claw" and alludes to the animal's very large claw on the first finger; the specific name, ''walkeri'', refers to its discoverer, amateur fossil collector

Fossil collecting (sometimes, in a non-scientific sense, fossil hunting) is the collection of fossils for scientific study, hobby, or profit. Fossil collecting, as practiced by amateurs, is the predecessor of modern paleontology and many sti ...

William J. Walker. The holotype specimen is one of the most complete theropod skeletons from the UK (and remains the most complete Spinosaurid

The Spinosauridae (or spinosaurids) are a clade or family of tetanuran theropod dinosaurs comprising ten to seventeen known genera. They came into prominence during the Cretaceous period. Spinosaurid fossils have been recovered worldwide, includin ...

), and its discovery attracted media attention. Specimens later discovered in other parts of the United Kingdom and Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese language, Aragonese and Occitan language, Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a pe ...

have also been assigned to the genus, though many have since been moved to new genera.

The holotype specimen, which may not have been fully grown, was estimated to have been between long and to have weighed between . ''Baryonyx'' had a long, low, and narrow snout, which has been compared to that of a gharial

The gharial (''Gavialis gangeticus''), also known as gavial or fish-eating crocodile, is a crocodilian in the family Gavialidae and among the longest of all living crocodilians. Mature females are long, and males . Adult males have a distinct ...

. The tip of the snout expanded to the sides in the shape of a rosette. Behind this, the upper jaw had a notch which fitted into the lower jaw (which curved upwards in the same area). It had a triangular crest on the top of its nasal bones

The nasal bones are two small oblong bones, varying in size and form in different individuals; they are placed side by side at the middle and upper part of the face and by their junction, form the bridge of the upper one third of the nose.

Ea ...

. ''Baryonyx'' had a large number of finely serrated, conical teeth, with the largest teeth in front. The neck formed an S-shape, and the neural spines

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates,Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic i ...

of its dorsal vertebrae increased in height from front to back. One elongated neural spine indicates it may have had a hump or ridge along the centre of its back. It had robust forelimbs, with the eponymous first-finger claw measuring about long.

Now recognised as a member of the family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

Spinosauridae, ''Baryonyx'' affinities were obscure when it was discovered. Some researchers have suggested that ''Suchosaurus cultridens

''Suchosaurus'' (meaning "crocodile lizard") is a spinosaurid dinosaur from Cretaceous England and Portugal, originally believed to be a genus of crocodile. The type material, consisting of teeth, was used by British palaeontologist Richard Ow ...

'' is a senior synonym

The Botanical and Zoological Codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

* In botanical nomenclature, a synonym is a scientific name that applies to a taxon that (now) goes by a different scientific name. For example, Linnae ...

(being an older name), and that ''Suchomimus tenerensis

''Suchomimus'' (meaning "crocodile mimic") is a genus of spinosaurid dinosaur that lived between 125 and 112 million years ago in what is now Niger, during the Aptian to early Albian stages of the Early Cretaceous period. It was named and d ...

'' belongs in the same genus; subsequent authors have kept them separate. ''Baryonyx'' was the first theropod dinosaur demonstrated to have been piscivorous (fish-eating), as evidenced by fish scales in the stomach region of the holotype specimen. It may also have been an active predator of larger prey and a scavenger

Scavengers are animals that consume dead organisms that have died from causes other than predation or have been killed by other predators. While scavenging generally refers to carnivores feeding on carrion, it is also a herbivorous feedin ...

, since it also contained bones of a juvenile iguanodontid. The creature would have caught and processed its prey primarily with its forelimbs and large claws. ''Baryonyx'' may have had semiaquatic

In biology, semiaquatic can refer to various types of animals that spend part of their time in water, or plants that naturally grow partially submerged in water. Examples are given below.

Semiaquatic animals

Semi aquatic animals include:

* Ve ...

habits, and coexisted with other theropod, ornithopod

Ornithopoda () is a clade of ornithischian dinosaurs, called ornithopods (), that started out as small, bipedal running grazers and grew in size and numbers until they became one of the most successful groups of herbivores in the Cretaceous w ...

, and sauropod

Sauropoda (), whose members are known as sauropods (; from '' sauro-'' + '' -pod'', ' lizard-footed'), is a clade of saurischian ('lizard-hipped') dinosaurs. Sauropods had very long necks, long tails, small heads (relative to the rest of their ...

dinosaurs, as well as pterosaurs

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to 6 ...

, crocodiles, turtles and fishes, in a fluvial

In geography and geology, fluvial processes are associated with rivers and streams and the deposits and landforms created by them. When the stream or rivers are associated with glaciers, ice sheets, or ice caps, the term glaciofluvial or fluviog ...

environment.

History of discovery

fossil collector

Fossil collecting (sometimes, in a non-scientific sense, fossil hunting) is the collection of fossils for scientific study, hobby, or profit. Fossil collecting, as practiced by amateurs, is the predecessor of modern paleontology and many sti ...

William J. Walker explored the Smokejacks Pit, a clay pit

A clay pit is a quarry or mine for the extraction of clay, which is generally used for manufacturing pottery, bricks or Portland cement. Quarries where clay is mined to make bricks are sometimes called brick pits.

A brickyard or brickworks i ...

in the Weald Clay Formation

Weald Clay or the Weald Clay Formation is a Lower Cretaceous sedimentary rock unit underlying areas of South East England, between the North and South Downs, in an area called the Weald Basin. It is the uppermost unit of the Wealden Group of ...

near Ockley in Surrey, England. He found a rock wherein he discovered a large claw, but after piecing it together at home, he realised the tip of the claw was missing. Walker returned to the same spot in the pit some weeks later, and found the missing part after searching for an hour. He also found a and part of a . Walker's son-in-law later brought the claw to the Natural History Museum of London

The Natural History Museum in London is a museum that exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history. It is one of three major museums on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, the others being the Science Museum an ...

, where it was examined by the British palaeontologists

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of foss ...

Alan J. Charig

Alan Jack Charig (1 July 1927 – 15 July 1997) was an English palaeontologist and writer who popularised his subject on television and in books at the start of the wave of interest in dinosaurs in the 1970s.

Charig was, though, first and fo ...

and Angela C. Milner, who identified it as belonging to a theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

. The palaeontologists found more bone fragments at the site in February, but the entire skeleton could not be collected until May and June due to weather conditions at the pit. A team of eight museum staff members and several volunteers excavated of rock matrix

Matrix most commonly refers to:

* ''The Matrix'' (franchise), an American media franchise

** '' The Matrix'', a 1999 science-fiction action film

** "The Matrix", a fictional setting, a virtual reality environment, within ''The Matrix'' (franchi ...

in 54 blocks over a three-week period. Walker donated the claw to the museum, and the Ockley Brick Company (owners of the pit) donated the rest of the skeleton and provided equipment. The area had been explored for 200 years, but no similar remains had been found before.

Most of the bones collected were encased in siltstone

Siltstone, also known as aleurolite, is a clastic sedimentary rock that is composed mostly of silt. It is a form of mudrock with a low clay mineral content, which can be distinguished from shale by its lack of fissility.Blatt ''et al.'' 1980, ...

nodules surrounded by fine sand and silt, with the rest lying in clay. The bones were and scattered over a area, but most were not far from their natural positions. The position of some bones was disturbed by a bulldozer

A bulldozer or dozer (also called a crawler) is a large, motorized machine equipped with a metal blade to the front for pushing material: soil, sand, snow, rubble, or rock during construction work. It travels most commonly on continuous track ...

, and some were broken by mechanical equipment before they were collected. Preparing the specimen was difficult, due to the hardness of the siltstone matrix and the presence of siderite

Siderite is a mineral composed of iron(II) carbonate (FeCO3). It takes its name from the Greek word σίδηρος ''sideros,'' "iron". It is a valuable iron mineral, since it is 48% iron and contains no sulfur or phosphorus. Zinc, magnesium and ...

; acid preparation was attempted, but most of the matrix was removed mechanically. It took six years of almost constant preparation to get all the bones out of the rock, and by the end, dental tools and air mallets had to be used under a microscope. The specimen represents about 65 percent of the skeleton, and consists of partial skull bones, including premaxillae

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has ...

(first bones of the upper jaw); the left maxillae (second bone of the upper jaw); both nasal

Nasal is an adjective referring to the nose, part of human or animal anatomy. It may also be shorthand for the following uses in combination:

* With reference to the human nose:

** Nasal administration, a method of pharmaceutical drug delivery

* ...

bones; the left lacrimal; the left prefrontal; the left postorbital

The ''postorbital'' is one of the bones in vertebrate skulls which forms a portion of the dermal skull roof and, sometimes, a ring about the orbit. Generally, it is located behind the postfrontal and posteriorly to the orbital fenestra. In some ...

; the braincase

In human anatomy, the neurocranium, also known as the braincase, brainpan, or brain-pan is the upper and back part of the skull, which forms a protective case around the brain. In the human skull, the neurocranium includes the calvaria or skul ...

including the occiput; both dentaries (the front bones of the lower jaw); various bones from the back of the lower jaw; teeth; cervical (neck), dorsal

Dorsal (from Latin ''dorsum'' ‘back’) may refer to:

* Dorsal (anatomy), an anatomical term of location referring to the back or upper side of an organism or parts of an organism

* Dorsal, positioned on top of an aircraft's fuselage

* Dorsal c ...

(back), and caudal

Caudal may refer to:

Anatomy

* Caudal (anatomical term) (from Latin ''cauda''; tail), used to describe how close something is to the trailing end of an organism

* Caudal artery, the portion of the dorsal aorta of a vertebrate that passes into the ...

(tail) ; ribs; a ; both (shoulder blades); both ; both (upper arm bones); the left and (lower arm bones); finger bones and (claw bones); hip bones; the upper end of the left (thigh bone) and lower end of the right; right (of the lower leg); and foot bones including an ungual. The original specimen number was BMNH R9951, but it was later re-catalogued as NHMUK VP R9951.

In 1986

The year 1986 was designated as the International Year of Peace by the United Nations.

Events January

* January 1

** Aruba gains increased autonomy from the Netherlands by separating from the Netherlands Antilles.

**Spain and Portugal en ...

, Charig and Milner named a new genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

and species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriat ...

with the skeleton as holotype specimen

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of sever ...

: ''Baryonyx walkeri''. The generic name derives from ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

; βαρύς (''barys'') means "heavy" or "strong", and ὄνυξ (''onyx'') means "claw" or "talon". The specific name honours Walker, for discovering the specimen. At that time, the authors did not know if the large claw belonged to the hand or the foot (as in dromaeosaurs, which it was then assumed to be). The dinosaur had been presented earlier the same year during a lecture at a conference about dinosaur systematics in Drumheller, Canada. Due to ongoing work on the bones (70 percent had been prepared at the time), they called their article preliminary and promised a more detailed description at a later date. ''Baryonyx'' was the first large Early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous (geochronology, geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous (chronostratigraphy, chronostratigraphic name), is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 145& ...

theropod found anywhere in the world by that time. Before the discovery of ''Baryonyx'' the last significant theropod find in the United Kingdom was '' Eustreptospondylus'' in 1871, and in a 1986 interview Charig called ''Baryonyx'' "the best find of the century" in Europe. ''Baryonyx'' was widely featured in international media, and was nicknamed "Claws" by journalists pun

A pun, also known as paronomasia, is a form of word play that exploits multiple meanings of a term, or of similar-sounding words, for an intended humorous or rhetorical effect. These ambiguities can arise from the intentional use of homophoni ...

ning on the title of the film ''Jaws

Jaws or Jaw may refer to:

Anatomy

* Jaw, an opposable articulated structure at the entrance of the mouth

** Mandible, the lower jaw

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Jaws (James Bond), a character in ''The Spy Who Loved Me'' and ''Moonraker''

* ...

''. Its discovery was the subject of a 1987 BBC documentary, and a cast of the skeleton is mounted at the Natural History Museum in London. In 1997, Charig and Milner published a monograph

A monograph is a specialist work of writing (in contrast to reference works) or exhibition on a single subject or an aspect of a subject, often by a single author or artist, and usually on a scholarly subject.

In library cataloging, ''monogra ...

describing the holotype skeleton in detail. The holotype specimen remains the most completely known spinosaurid

The Spinosauridae (or spinosaurids) are a clade or family of tetanuran theropod dinosaurs comprising ten to seventeen known genera. They came into prominence during the Cretaceous period. Spinosaurid fossils have been recovered worldwide, includin ...

skeleton.

Additional specimens

Fossils from other parts of the UK andIberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese language, Aragonese and Occitan language, Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a pe ...

, mostly isolated teeth, have subsequently been attributed to ''Baryonyx'' or similar animals. Isolated teeth and bones from the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Is ...

, including hand bones reported in 1998 and a vertebra reported by the British palaeontologists Steve Hutt and Penny Newbery in 2004, have been attributed to this genus. A maxilla fragment from La Rioja, Spain, was attributed to ''Baryonyx'' by the Spanish palaeontologists Luis I. Viera and José Angel Torres in 1995 (although the American palaeontologist Thomas R. Holtz

Thomas Richard Holtz Jr. (born September 13, 1965) is an American vertebrate palaeontologist, author, and principal lecturer at the University of Maryland's Department of Geology. He has published extensively on the phylogeny, morphology, ecomor ...

and colleagues raised the possibility that it could have belonged to ''Suchomimus'' in 2004). In 1999, a postorbital, , tooth, vertebral remains, (hand bones), and a phalanx from the Salas de los Infantes

Salas de los Infantes is a municipality and city located in Burgos Province between La Rioja, Soria and Burgos in Spain. It is hilly with many foothills and mountains. The mountain range Sierra de la Demanda with the black lagoon, ''La Laguna N ...

deposit in Burgos Province, Spain, were attributed to an immature ''Baryonyx'' (though some of these elements are unknown in the holotype) by the Spanish palaeontologist Carolina Fuentes Vidarte and colleagues. Dinosaur tracks

A trace fossil, also known as an ichnofossil (; from el, ἴχνος ''ikhnos'' "trace, track"), is a fossil record of biological activity but not the preserved remains of the plant or animal itself. Trace fossils contrast with body fossils, ...

near Burgos have also been suggested to belong to ''Baryonyx'' or a similar theropod.

In 2011, a specimen (Catalogued as ML1190 in

In 2011, a specimen (Catalogued as ML1190 in Museu da Lourinhã

Museu da Lourinhã is a museum in the town of Lourinhã, west Portugal. It was founded in 1984 by GEAL - Grupo de Etnologia e Arqueologia da Lourinhã (Lourinhã's Group of Ethnology and Archeology). The president of the Direction Board is Lubélia ...

) from the Papo Seco Formation in Boca do Chapim, Portugal, with a fragmentary dentary, teeth, vertebrae, ribs, hip bones, a scapula, and a phalanx bone, was attributed to ''Baryonyx'' by the Portuguese palaeontologist Octávio Mateus

Octávio Mateus (born 1975) is a Portuguese dinosaur paleontologist and biologist Professor of Paleontology at the Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa. He graduated in Universidade de Évora and received his PhD at ...

and colleagues, the most complete Iberian remains of the animal. The skeletal elements of this specimen are also represented in the more complete holotype (which was of similar size), except for the mid-neck vertebrae. In 2018, the British palaeontologist Thomas M. S. Arden and colleagues found that the Portuguese skeleton did not belong to ''Baryonyx'', since the front of its dentary bone was not strongly upturned. This specimen was made the basis of the new genus ''Iberospinus

''Iberospinus'' or (meaning " Iberian spine") is an extinct genus of spinosaurid dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous (Barremian) Papo Seco Formation of Portugal. The genus contains a single species, ''I. natarioi'', known from several assorted b ...

'' by Mateus and Darío Estraviz-López in 2022. Some additional spinosaurid remains from Iberia may belong to taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular nam ...

other than ''Baryonyx'', including ''Vallibonavenatrix

''Vallibonavenatrix'' (meaning "Vallibona huntress" after the town near where its remains were found) is a genus of spinosaurid dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous (Barremian) Arcillas de Morella Formation of Castellón, Spain. The type and on ...

'' from Morella.

In 2021, the British palaeontologist Chris T. Barker and colleagues described two new spinosaurid genera from the Wessex Formation

The Wessex Formation is a fossil-rich English geological formation that dates from the Berriasian to Barremian stages (about 145–125 million years ago) of the Early Cretaceous. It forms part of the Wealden Group and underlies the younger Vect ...

of the Isle of Wight, ''Ceratosuchops

''Ceratosuchops'' (meaning "horned crocodile face") is a genus of spinosaurid from the Early Cretaceous (Barremian) of Britain.

Discovery and naming

In 2021, the type species ''C. inferodios'' was named and described by a team of paleont ...

'' and ''Riparovenator

''Riparovenator'' ("riverbank hunter") is a genus of baryonychine spinosaurid dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous (Barremian) period of Britain, the type species is ''Riparovenator milnerae''.

Discovery and naming

Between 2013 and 2017, s ...

'' (the latter named ''R. milnerae'' honouring Milner for her contributions to spinosaurid research), and stated that spinosaurid material from there that had previously been attributed to the contemporary ''Baryonyx'' could have belonged to other taxa instead. These specimens had previously been assigned to ''Baryonyx'' in a 2017 conference abstract. Barker and colleagues stated that the recognition of the Wessex Formation specimens as new genera renders the presence of ''Baryonyx'' there ambiguous, and most of the previously assigned isolated material from the Wealden Supergroup

The Wealden Group, occasionally also referred to as the Wealden Supergroup, is a group (a sequence of rock strata) in the lithostratigraphy of southern England. The Wealden group consists of paralic to continental (freshwater) facies sedimentar ...

is therefore indeterminate. These authors also found the Portuguese specimen ML 1190 to group with ''Baryonyx'', supporting its original assignment to the genus.

Possible synonyms

In 2003, Milner noted that some teeth at the Natural History Museum previously identified as belonging to the genera ''Suchosaurus

''Suchosaurus'' (meaning "crocodile lizard") is a spinosaurid dinosaur from Cretaceous England and Portugal, originally believed to be a genus of crocodile. The type material, consisting of teeth, was used by British palaeontologist Richard Owe ...

'' and ''Megalosaurus

''Megalosaurus'' (meaning "great lizard", from Greek , ', meaning 'big', 'tall' or 'great' and , ', meaning 'lizard') is an extinct genus of large carnivorous theropod dinosaurs of the Middle Jurassic period (Bathonian stage, 166 million years ...

'' probably belonged to ''Baryonyx''. The type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specim ...

of ''Suchosaurus'', ''S. cultridens'', was named by the British biologist Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Ow ...

in 1841, based on teeth discovered by the British geologist Gideon A. Mantell in Tilgate Forest, Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the Englis ...

. Owen originally thought the teeth to have belonged to a crocodile

Crocodiles (family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to include all extant me ...

; he was yet to name the group Dinosauria, which happened the following year. A second species, ''S. girardi'', was named by the French palaeontologist Henri Émile Sauvage

Henri Émile Sauvage (22 September 1842 in Boulogne-sur-Mer – 3 January 1917 in Boulogne-sur-Mer) was a French paleontologist, ichthyologist, and herpetologist. He was a leading expert on Mesozoic fish and reptiles.Éric Buffetaut

Éric Buffetaut (born 19 November 1950) is a French paleontologist, author and researcher at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique since 1976 where he is a Doctor of Science and Director of Research. Buffetaut is a specialist of fossil a ...

considered the teeth of ''S. girardi'' very similar to those of ''Baryonyx'' (and ''S. cultridens'') except for the stronger development of the flutes (or "ribs"; lengthwise ridges), suggesting that the remains belonged to the same genus. Buffetaut agreed with Milner that the teeth of ''S. cultridens'' were almost identical to those of ''B. walkeri'', but with a ribbier surface. The former taxon might be a senior synonym

The Botanical and Zoological Codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

* In botanical nomenclature, a synonym is a scientific name that applies to a taxon that (now) goes by a different scientific name. For example, Linnae ...

of the latter (since it was published first), depending on whether the differences were within a taxon or between different ones. According to Buffetaut, since the holotype specimen of ''S. cultridens'' is a single tooth and that of ''B. walkeri'' is a skeleton, it would be more practical to retain the newer name. In 2011, Mateus and colleagues agreed that ''Suchosaurus'' was closely related to ''Baryonyx'', but considered both species in the former genus ''nomina dubia

In binomial nomenclature, a ''nomen dubium'' (Latin for "doubtful name", plural ''nomina dubia'') is a scientific name that is of unknown or doubtful application.

Zoology

In case of a ''nomen dubium'' it may be impossible to determine whether a s ...

'' (dubious names) since their holotype specimens were not considered diagnostic (lacking distinguishing features) and could not be definitely equated with other taxa. In any case, the identification of ''Suchosaurus'' as a spinosaurid makes it the first named member of the family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

.

In 1997, Charig and Milner noted that two fragmentary spinosaurid snouts from the Elrhaz Formation of Niger (reported by the French palaeontologist Philippe Taquet in 1984) were similar enough to ''Baryonyx'' that they considered them to belong to an indeterminate species of the genus (despite their much younger Aptian

The Aptian is an age in the geologic timescale or a stage in the stratigraphic column. It is a subdivision of the Early or Lower Cretaceous Epoch or Series and encompasses the time from 121.4 ± 1.0 Ma to 113.0 ± 1.0 Ma (million years ag ...

geological age). In 1998, these fossils became the basis of the genus and species '' Cristatusaurus lapparenti'', named by Taquet and the American palaeontologist Dale Russell. The American palaeontologist Paul Sereno

Paul Callistus Sereno (born October 11, 1957) is a professor of paleontology at the University of Chicago and a National Geographic "explorer-in-residence" who has discovered several new dinosaur species on several continents, including at si ...

and colleagues named the new genus and species ''Suchomimus tenerensis

''Suchomimus'' (meaning "crocodile mimic") is a genus of spinosaurid dinosaur that lived between 125 and 112 million years ago in what is now Niger, during the Aptian to early Albian stages of the Early Cretaceous period. It was named and d ...

'' later in 1998, based on more complete fossils from the Elrhaz Formation. In 2002, the German palaeontologist Hans-Dieter Sues

Hans-Dieter Sues (born January 13, 1956) is a German-born American paleontologist who is Senior Scientist and Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the National Museum of Natural History of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.

He receiv ...

and colleagues proposed that ''Suchomimus tenerensis'' was similar enough to ''Baryonyx walkeri'' to be considered a species within the same genus (as ''B. tenerensis''), and that ''Suchomimus'' was identical to ''Cristatusaurus''. Milner concurred that the material from Niger was indistinguishable from ''Baryonyx'' in 2003. In a 2004 conference abstract, Hutt and Newberry supported the synonymy based on a large theropod vertebra from the Isle of Wight which they attributed to an animal closely related to ''Baryonyx'' and ''Suchomimus''. Later studies have kept ''Baryonyx'' and ''Suchomimus'' separate, whereas ''Cristatusaurus'' has been proposed to be either a ''nomen dubium'' or possibly distinct from both. A 2017 review paper

A review article is an article that summarizes the current state of understanding on a topic within a certain discipline. A review article is generally considered a secondary source since it may analyze and discuss the method and conclusions ...

by the Brazilian palaeontologist Carlos Roberto A. Candeiro and colleagues stated that this debate was more in the realm of semantics than science, as it is generally agreed that ''B. walkeri'' and ''S. tenerensis'' are distinct, related species. Barker and colleagues found ''Suchomimus'' to be closer related to the British genera ''Riparovenator'' and ''Ceratosuchops'' than to ''Baryonyx'' in 2021.

Description

vertebral column

The vertebral column, also known as the backbone or spine, is part of the axial skeleton. The vertebral column is the defining characteristic of a vertebrate in which the notochord (a flexible rod of uniform composition) found in all chordate ...

of the ''B. walkeri'' holotype specimen (NHM R9951) do not appear to have co-ossified (fused) suggests that the individual was not fully grown, and the mature animal may have been much larger (as is the case for some other spinosaurids). On the other hand, the specimen's fused sternum indicates that it may have been mature.

Skull

The skull of ''Baryonyx'' is incompletely known, and much of the middle and hind portions are not preserved. The full length of the skull is estimated to have been long, based on comparison with that of the related genus ''Suchomimus'' (which was 20% larger). It was elongated, and the front of the premaxillae formed a long, narrow, and low snout ( rostrum) with a smoothly rounded upper surface. The (bony nostrils) were long, low, and placed far back from the snout tip. The front of the snout expanded into a spatulate (spoon-like), "terminal rosette", a shape similar to the rostrum of the moderngharial

The gharial (''Gavialis gangeticus''), also known as gavial or fish-eating crocodile, is a crocodilian in the family Gavialidae and among the longest of all living crocodilians. Mature females are long, and males . Adult males have a distinct ...

. The front of the lower margin of the premaxillae was downturned (or hooked), whereas that of the front portion of the maxillae was upturned. This morphology resulted in a sigmoid

Sigmoid means resembling the lower-case Greek letter sigma (uppercase Σ, lowercase σ, lowercase in word-final position ς) or the Latin letter S. Specific uses include:

* Sigmoid function, a mathematical function

* Sigmoid colon, part of the l ...

or S shaped margin of the lower upper tooth row, in which the teeth from the front of the maxilla were projecting forward. The snout was particularly narrow directly behind the rosette; this area received the large teeth of the mandible. The maxilla and premaxilla of ''Baryonyx'' fit together in a complex articulation, and the resulting gap between the upper and lower jaw is known as the . A downturned premaxilla and a sigmoid lower margin of the upper tooth row was also present in distantly related theropods such as ''Dilophosaurus

''Dilophosaurus'' ( ) is a genus of theropod dinosaurs that lived in what is now North America during the Early Jurassic, about 193 million years ago. Three skeletons were discovered in northern Arizona in 1940, and the two best preserve ...

''. The snout had extensive (openings), which would have been exits for blood vessels and nerves, and the maxilla appears to have housed sinuses

Paranasal sinuses are a group of four paired air-filled spaces that surround the nasal cavity. The maxillary sinuses are located under the eyes; the frontal sinuses are above the eyes; the ethmoidal sinuses are between the eyes and the spheno ...

.

sagittal crest

A sagittal crest is a ridge of bone running lengthwise along the midline of the top of the skull (at the sagittal suture) of many mammalian and reptilian skulls, among others. The presence of this ridge of bone indicates that there are exception ...

was present above the eyes, on the upper mid-line of the nasals. This crest was triangular, narrow, and sharp in its front part, and was distinct from those of other spinosaurids in ending hind wards in a cross-shaped process. The lacrimal bone in front of the eye appears to have formed a horn core similar to those seen, for example, in ''Allosaurus

''Allosaurus'' () is a genus of large carnosaurian theropod dinosaur that lived 155 to 145 million years ago during the Late Jurassic epoch ( Kimmeridgian to late Tithonian). The name "''Allosaurus''" means "different lizard" alludin ...

'', and was distinct from other spinosaurids in being solid and almost triangular. The occiput was narrow, with the paroccipital processes pointing outwards horizontally, and the were lengthened, descending far below the (the lowermost bone of the occiput). Sereno and colleagues suggested that some of ''Baryonyx'' cranial bones had been misidentified by Charig and Milner, resulting in the occiput being reconstructed as too deep, and that the skull was instead probably as low, long and narrow as that of ''Suchomimus''. The front of the dentary in the mandible sloped upwards towards the curve of the snout. The dentary was very long and shallow, with a prominent Meckelian groove on the inner side. The , where the two halves of the lower jaw connected at the front, was particularly short. The rest of the lower jaw was fragile; the hind third was much thinner than the front, with a blade-like appearance. The front part of the dentary curved outwards to accommodate the large front teeth, and this area formed the mandibular part of the rosette. The dentary–like the snout—had many foramina.

Most of the teeth found with the holotype specimen were not in articulation with the skull; a few remained in the upper jaw, and only small replacement teeth were still borne by the lower jaw. The teeth had the shape of recurved cones, where slightly flattened from sideways, and their curvature was almost uniform. The roots were very long, and tapered towards their extremity. The carinae (sharp front and back edges) of the teeth were finely serrated with denticles on the front and back, and extended all along the crown. There were around six to eight denticles per mm (0.039 in), a much larger number than in large-bodied theropods like '' Torvosaurus'' and ''

Most of the teeth found with the holotype specimen were not in articulation with the skull; a few remained in the upper jaw, and only small replacement teeth were still borne by the lower jaw. The teeth had the shape of recurved cones, where slightly flattened from sideways, and their curvature was almost uniform. The roots were very long, and tapered towards their extremity. The carinae (sharp front and back edges) of the teeth were finely serrated with denticles on the front and back, and extended all along the crown. There were around six to eight denticles per mm (0.039 in), a much larger number than in large-bodied theropods like '' Torvosaurus'' and ''Tyrannosaurus

''Tyrannosaurus'' is a genus of large theropoda, theropod dinosaur. The species ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' (''rex'' meaning "king" in Latin), often called ''T. rex'' or colloquially ''T-Rex'', is one of the best represented theropods. ''Tyrannosa ...

''. Some of the teeth were fluted, with six to eight ridges along the length of their inner sides and fine-grained (outermost layer of teeth), while others bore no flutes; their presence is probably related to position or ontogeny

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to the s ...

(development during growth). The inner side of each tooth row had a bony wall. The number of teeth was large compared to most other theropods, with six to seven teeth in each premaxilla and thirty-two in each dentary. Based on the closer packing and smaller size of the dentary teeth compared to those in the corresponding length of the premaxilla, the difference between the number of teeth in the upper and lower jaws appears to have been more pronounced than in other theropods. The terminal rosette in the upper jaw of the holotype had thirteen (tooth sockets), six on the left and seven on the right side, showing tooth count asymmetry. The first four upper teeth were large (with the second and third the largest), while the fourth and fifth progressively decreased in size. The diameter of the largest was twice that of the smallest. The first four alveoli of the dentary (corresponding to the tip of the upper jaw) were the largest, with the rest more regular in size. Small subtriangular were present between the alveoli.

Postcranial skeleton

Initially thought to have lacked the sigmoid curve typical of theropods, the neck of ''Baryonyx'' does appear to have formed an S shape, though straighter than in other theropods. The cervical vertebrae of the neck tapered towards the head and became progressively longer front to back. Their (the processes that connected the vertebrae) were flat, and their (processes to which neck muscles attached) were well developed. The (the second neck vertebra) was small relative to the size of the skull and had a well-developed . The of the cervical vertebrae were not always sutured to the (the bodies of the vertebrae), and the there were low and thin. The were short, similar to those of crocodiles, and possibly overlapped each other somewhat. The centra of the dorsal vertebrae of the back were similar in size. Like in other theropods, the skeleton of ''Baryonyx'' showed skeletal pneumaticity, reducing its weight through (openings) in the neural arches and (hollow depressions) in the centra (primarily near the ). From front to back, the neural spines of the dorsal vertebrae changed from short and stout to tall and broad. One isolated dorsal neural spine was moderately elongated and slender, indicating that ''Baryonyx'' may have had a hump or ridge along the centre of its back (though incipiently developed compared to those of other spinosaurids). ''Baryonyx'' was unique among spinosaurids in having a marked constriction from side to side in a vertebra that either belonged to the or front of the tail. The coracoid tapered hind-wards when viewed in profile, and, uniquely among spinosaurids, connected with the scapula in a peg-and-notch articulation. The scapulae were robust and the bones of the forelimb were short in relation to the animal's size, but broad and sturdy. The humerus was short and stout, with its ends broadly expanded and flattened—the upper side for the and muscle attachment and the lower for articulation with the radius and ulna. The radius was short, stout and straight, and less than half the length of the humerus, while the ulna was a little longer. The ulna had a powerful and an expanded lower end. The hands had three fingers; the first finger bore a large claw measuring about along its curve in the holotype specimen. The claw would have been lengthened by akeratin

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. Alpha-keratin (α-keratin) is a type of keratin found in vertebrates. It is the key structural material making up Scale (anatomy), scales, hair, Nail ...

(horny) sheath in life. Apart from its size, the claw's proportions were fairly typical of a theropod, i.e. it was bilaterally symmetric

Symmetry in biology refers to the symmetry observed in organisms, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria. External symmetry can be easily seen by just looking at an organism. For example, take the face of a human being which has a pl ...

, slightly compressed, smoothly rounded, and sharply pointed. A groove for the sheath ran along the length of the claw. The other claws of the hand were much smaller. The (main hip bone) of the pelvis had a prominent , an anterior process that was slender and vertically expanded, and a posterior process that was long and straight. The ilium also had a prominent and a deep grove that faced downwards. The (the socket for the femur) was long from front to back. The (lower and rearmost hip bone) had a well developed at the upper part. The margin of the blade at the lower end was turned outward, and the pubic foot was not expanded. The femur lacked a groove on the fibular condyle, and, uniquely among spinosaurids, the fibula had a very shallow fibular (depression).

Classification

In their original description, Charig and Milner found ''Baryonyx'' unique enough to warrant a new family of theropod dinosaurs: Baryonychidae. They found ''Baryonyx'' to be unlike any other theropod group, and considered the possibility that it was a thecodont (a grouping of early archosaurs now considered unnatural), due to having apparently primitive features, but noted that the articulation of the maxilla and premaxilla was similar to that in ''Dilophosaurus''. They also noted that the two snouts from Niger (which later became the basis of ''Cristatusaurus''), assigned to the family Spinosauridae by Taquet in 1984, appeared almost identical to that of ''Baryonyx'' and they referred them to Baryonychidae instead. In 1988, the American palaeontologist Gregory S. Paul agreed with Taquet that ''Spinosaurus'', described in 1915 based on fragmentary remains from Egypt that were destroyed in

In their original description, Charig and Milner found ''Baryonyx'' unique enough to warrant a new family of theropod dinosaurs: Baryonychidae. They found ''Baryonyx'' to be unlike any other theropod group, and considered the possibility that it was a thecodont (a grouping of early archosaurs now considered unnatural), due to having apparently primitive features, but noted that the articulation of the maxilla and premaxilla was similar to that in ''Dilophosaurus''. They also noted that the two snouts from Niger (which later became the basis of ''Cristatusaurus''), assigned to the family Spinosauridae by Taquet in 1984, appeared almost identical to that of ''Baryonyx'' and they referred them to Baryonychidae instead. In 1988, the American palaeontologist Gregory S. Paul agreed with Taquet that ''Spinosaurus'', described in 1915 based on fragmentary remains from Egypt that were destroyed in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, and ''Baryonyx'' were similar and (due to their kinked snouts) possibly late-surviving dilophosaurs. Buffetaut also supported this relationship in 1989. In 1990, Charig and Milner dismissed the spinosaurid affinities of ''Baryonyx'', since they did not find their remains similar enough. In 1997, they agreed that Baryonychidae and Spinosauridae were related, but disagreed that the former name should become a synonym of the latter, because the completeness of ''Baryonyx'' compared to ''Spinosaurus'' made it a better type genus

In biological taxonomy, the type genus is the genus which defines a biological family and the root of the family name.

Zoological nomenclature

According to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, "The name-bearing type of a nominal ...

for a family, and because they did not find the similarities between the two significant enough. Holtz and colleagues listed Baryonychidae as a synonym of Spinosauridae in 2004.

Discoveries in the 1990s shed more light on the relationships of ''Baryonyx'' and its relatives. In 1996, a snout from Morocco was referred to ''Spinosaurus'', and '' Irritator'' and ''Angaturama'' from Brazil (the two are possible synonyms) were named. ''Cristatusaurus'' and ''Suchomimus'' were named based on fossils from Niger in 1998. In their description of ''Suchomimus'', Sereno and colleagues placed it and ''Baryonyx'' in the new subfamily

In biological classification, a subfamily (Latin: ', plural ') is an auxiliary (intermediate) taxonomic rank, next below family but more inclusive than genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classifica ...

Baryonychinae

Baryonychinae is an extinct clade or subfamily of spinosaurids from the Early Cretaceous (Valanginian-Albian) of Britain, Portugal, and Niger. In 2021, it consisted of six genera: '' Ceratosuchops'', '' Cristatusaurus'', '' Riparovenator'', '' Su ...

within Spinosauridae; ''Spinosaurus'' and ''Irritator'' were placed in the subfamily Spinosaurinae

The Spinosauridae (or spinosaurids) are a clade or family of tetanuran theropod dinosaurs comprising ten to seventeen known genera. They came into prominence during the Cretaceous period. Spinosaurid fossils have been recovered worldwide, in ...

. Baryonychinae was distinguished by the small size and larger number of teeth in the dentary behind the terminal rosette, the deeply keeled front dorsal vertebrae, and by having serrated teeth. Spinosaurinae was distinguished by their straight tooth crowns without serrations, small first tooth in the premaxilla, increased spacing of teeth in the jaws, and possibly by having their nostrils placed further back and the presence of a deep neural spine sail. They also united the spinosaurids and their closest relatives in the superfamily Spinosauroidea, but in 2010, the British palaeontologist Roger Benson considered this a junior synonym of Megalosauroidea

Megalosauroidea (meaning 'great/big lizard forms') is a superfamily (or clade) of tetanuran theropod dinosaurs that lived from the Middle Jurassic to the Late Cretaceous period. The group is defined as '' Megalosaurus bucklandii'' and all taxa s ...

(an older name). In a 2007 conference abstract, the American palaeontologist Denver W. Fowler suggested that since ''Suchosaurus'' is the first named genus in its group, the clade names Spinosauroidea, Spinosauridae, and Baryonychinae should be replaced by Suchosauroidea, Suchosauridae, and Suchosaurinae, regardless of whether or not the name ''Baryonyx'' is retained. A 2017 study by the Brazilian palaeontologists Marcos A. F. Sales and Cesar L. Schultz found that the clade Baryonychinae was not well supported, since serrated teeth may be an ancestral trait

In phylogenetics, a primitive (or ancestral) character, trait, or feature of a lineage or taxon is one that is inherited from the common ancestor of a clade (or clade group) and has undergone little change since. Conversely, a trait that appea ...

among spinosaurids.

Barker and colleagues found support for a Baryonychinae-Spinosaurinae split in 2021, and the following cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to ...

shows the position of ''Baryonyx'' within Spinosauridae according to their study:

Evolution

Spinosaurids appear to have been widespread from the

Spinosaurids appear to have been widespread from the Barremian

The Barremian is an age in the geologic timescale (or a chronostratigraphic stage) between 129.4 ± 1.5 Ma (million years ago) and 121.4 ± 1.0 Ma). It is a subdivision of the Early Cretaceous Epoch (or Lower Cretaceous Series). It is preceded ...

to the Cenomanian

The Cenomanian is, in the ICS' geological timescale, the oldest or earliest age of the Late Cretaceous Epoch or the lowest stage of the Upper Cretaceous Series. An age is a unit of geochronology; it is a unit of time; the stage is a unit in ...

stages of the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

period, about 130 to 95 million years ago, while the oldest known spinosaurid remains date to the Middle Jurassic

The Middle Jurassic is the second Epoch (geology), epoch of the Jurassic Period (geology), Period. It lasted from about 174.1 to 163.5 million years ago. Fossils of land-dwelling animals, such as dinosaurs, from the Middle Jurassic are relatively ...

. They shared features such as long, narrow, crocodile-like skulls; sub-circular teeth, with fine to no serrations; the terminal rosette of the snout; and a secondary palate that made them more resistant to torsion. In contrast, the primitive and typical condition for theropods was a tall, narrow snout with blade-like (ziphodont) teeth with serrated carinae. The skull adaptations of spinosaurids converged with those of crocodilian

Crocodilia (or Crocodylia, both ) is an order of mostly large, predatory, semiaquatic reptiles, known as crocodilians. They first appeared 95 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous period (Cenomanian stage) and are the closest livin ...

s; early members of the latter group had skulls similar to typical theropods, later developing elongated snouts, conical teeth, and secondary palates. These adaptations may have been the result of a dietary change from terrestrial prey to fish. Unlike crocodiles, the post-cranial skeletons of baryonychine spinosaurids do not appear to have aquatic adaptations.Supplementary Information/ref> Sereno and colleagues proposed in 1998 that the large thumb-claw and robust forelimbs of spinosaurids evolved in the Middle Jurassic, before the elongation of the skull and other adaptations related to fish-eating, since the former features are shared with their megalosaurid relatives. They also suggested that the spinosaurines and baryonychines diverged before the Barremian age of the Early Cretaceous. Several theories have been proposed about the

biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, ...

of the spinosaurids. Since ''Suchomimus'' was more closely related to ''Baryonyx'' (from Europe) than to ''Spinosaurus''—although that genus also lived in Africa—the distribution of spinosaurids cannot be explained as vicariance

Allopatric speciation () – also referred to as geographic speciation, vicariant speciation, or its earlier name the dumbbell model – is a mode of speciation that occurs when biological populations become geographically isolated from ...

resulting from continental rifting

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics.

Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-grabe ...

. Sereno and colleagues proposed that spinosaurids were initially distributed across the supercontinent

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass. However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", which leav ...

Pangea

Pangaea or Pangea () was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous approximately 335 million y ...

, but split with the opening of the Tethys Sea

The Tethys Ocean ( el, Τηθύς ''Tēthús''), also called the Tethys Sea or the Neo-Tethys, was a prehistoric ocean that covered most of the Earth during much of the Mesozoic Era and early Cenozoic Era, located between the ancient continents ...

. Spinosaurines would then have evolved in the south (Africa and South America: in Gondwana

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final sta ...

) and baryonychines in the north (Europe: in Laurasia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

), with ''Suchomimus'' the result of a single north-to-south dispersal event. Buffetaut and the Tunisian palaeontologist Mohamed Ouaja also suggested in 2002 that baryonychines could be the ancestors of spinosaurines, which appear to have replaced the former in Africa. Milner suggested in 2003 that spinosaurids originated in Laurasia during the Jurassic, and dispersed via the Iberian land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regression, in which sea leve ...

into Gondwana, where they radiated. In 2007, Buffetaut pointed out that palaeogeographical studies had demonstrated that Iberia was near northern Africa during the Early Cretaceous, which he found to confirm Milner's idea that the Iberian region was a stepping stone between Europe and Africa, which is supported by the presence of baryonychines in Iberia. The direction of the dispersal between Europe and Africa is still unknown, and subsequent discoveries of spinosaurid remains in Asia and possibly Australia indicate that it may have been complex.

In 2016, the Spanish palaeontologist Alejandro Serrano-Martínez and colleagues reported the oldest known spinosaurid fossil, a tooth from the Middle Jurassic of Niger, which they found to suggest that spinosaurids originated in Gondwana, since other known Jurassic spinosaurid teeth are also from Africa, but they found the subsequent dispersal routes unclear. Some later studies instead suggested this tooth belonged to a megalosaurid. Candeiro and colleagues suggested in 2017 that spinosaurids of northern Gondwana were replaced by other predators, such as abelisauroids, since no definite spinosaurid fossils are known from after the Cenomanian anywhere in the world. They attributed the disappearance of spinosaurids and other shifts in the fauna of Gondwana to changes in the environment, perhaps caused by transgressions in sea level. Malafaia and colleagues stated in 2020 that ''Baryonyx'' remains the oldest unquestionable spinosaurid, while acknowledging that older remains had also been tentatively assigned to the group. Barker and colleagues found support for a European origin for spinosaurids in 2021, with an expansion to Asia and Gondwana during the first half of the Early Cretaceous. In contrast to Sereno, these authors suggested there had been at least two dispersal events from Europe to Africa, leading to ''Suchomimus'' and the African part of Spinosaurinae.

Palaeobiology

Diet and feeding

In 1986, Charig and Milner suggested that its elongated snout with many finely serrated teeth indicated that ''Baryonyx'' was piscivorous (fish-eating), speculating that it crouched on a riverbank and used its claw to gaff fish out of the water (similar to the moderngrizzly bear

The grizzly bear (''Ursus arctos horribilis''), also known as the North American brown bear or simply grizzly, is a population or subspecies of the brown bear inhabiting North America.

In addition to the mainland grizzly (''Ursus arctos horri ...

). Two years earlier, Taquet pointed out that the spinosaurid snouts from Niger were similar to those of the modern gharial and suggested a behaviour similar to herons

The herons are long-legged, long-necked, freshwater and coastal birds in the family Ardeidae, with 72 recognised species, some of which are referred to as egrets or bitterns rather than herons. Members of the genera ''Botaurus'' and ''Ixobrychus ...

or storks

Storks are large, long-legged, long-necked wading birds with long, stout bills. They belong to the family called Ciconiidae, and make up the order Ciconiiformes . Ciconiiformes previously included a number of other families, such as herons an ...

. In 1987, the Scottish biologist Andrew Kitchener disputed the piscivorous behaviour of ''Baryonyx'' and suggested that it would have been a scavenger

Scavengers are animals that consume dead organisms that have died from causes other than predation or have been killed by other predators. While scavenging generally refers to carnivores feeding on carrion, it is also a herbivorous feedin ...

, using its long neck to feed on the ground, its claws to break into a carcass, and its long snout (with nostrils far back for breathing) for investigating the body cavity. Kitchener argued that ''Baryonyx'' jaws and teeth were too weak to kill other dinosaurs and too heavy to catch fish, with too many adaptations for piscivory. According to the Irish palaeontologist Robin E. H. Reid, a scavenged carcass would have been broken up by its predator and large animals capable of doing so—such as grizzly bears—are also capable of catching fish (at least in shallow water).

In 1997, Charig and Milner demonstrated direct dietary evidence in the stomach region of the ''B. walkeri'' holotype. It contained the first evidence of piscivory in a theropod dinosaur, acid-etched scales and teeth of the common fish '' Scheenstia mantelli'' (then classified in the genus ''Lepidotes

''Lepidotes'' (from el, λεπιδωτός , 'covered with scales') (previously known as ''Lepidotus'') is an extinct genus of Mesozoic ray-finned fish. It has been considered a wastebasket taxon, characterised by "general features, such as thi ...

''), and abraded or etched bones of a young iguanodontid. They also presented circumstantial evidence for piscivory, such as crocodile-like adaptations for catching and swallowing prey: long, narrow jaws with their "terminal rosette", similar to those of a gharial, and the downturned tip and notch of the snout. In their view, these adaptations suggested that ''Baryonyx'' would have caught small to medium-sized fish in the manner of a crocodilian: gripping them with the notch of the snout (giving the teeth a "stabbing function"), tilting the head backwards, and swallowing them headfirst. Larger fish would be broken up with the claws. That the teeth in the lower jaw were smaller, more crowded and numerous than those in the upper jaw may have helped the animal grip food. Charig and Milner maintained that ''Baryonyx'' would primarily have eaten fish (although it would also have been an active predator and opportunistic scavenger), but it was not equipped to be a macro-predator

An apex predator, also known as a top predator, is a predator at the top of a food chain, without natural predators of its own.

Apex predators are usually defined in terms of trophic dynamics, meaning that they occupy the highest trophic lev ...

like ''Allosaurus''. They suggested that ''Baryonyx'' mainly used its forelimbs and large claws to catch, kill and tear apart larger prey. An apparent gastrolith

A gastrolith, also called a stomach stone or gizzard stone, is a rock held inside a gastrointestinal tract. Gastroliths in some species are retained in the muscular gizzard and used to grind food in animals lacking suitable grinding teeth. In oth ...

(gizzard

The gizzard, also referred to as the ventriculus, gastric mill, and gigerium, is an organ found in the digestive tract of some animals, including archosaurs (pterosaurs, crocodiles, alligators, dinosaurs, birds), earthworms, some gastropods, so ...

stone) was also found with the specimen. The German palaeontologist Oliver Wings suggested in 2007 that the low number of stones found in theropods like ''Baryonyx'' and ''Allosaurus'' could have been ingested by accident. In 2004, a pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 ...

neck vertebra from Brazil with a spinosaurid tooth embedded in it reported by Buffetaut and colleagues confirmed that the latter were not exclusively piscivorous.

A 2005 beam-theory study by the Canadian palaeontologist François Therrien and colleagues was unable to reconstruct force profiles of ''Baryonyx'', but found that the related ''Suchomimus'' would have used the front part of its jaws to capture prey, and suggested that the jaws of spinosaurids were adapted for hunting smaller terrestrial prey in addition to fish. They envisaged that spinosaurids could have captured smaller prey with the rosette of teeth at the front of the jaws, and finished it by shaking it. Larger prey would instead have been captured and killed with their forelimbs instead of their bite, since their skulls would not be able to resist the bending stress. They also agreed that the conical teeth of spinosaurids were well-developed for impaling and holding prey, with their shape enabling them to withstand bending loads from all directions. A 2007 finite element analysis

The finite element method (FEM) is a popular method for numerically solving differential equations arising in engineering and mathematical modeling. Typical problem areas of interest include the traditional fields of structural analysis, heat ...

of CT scanned snouts by the British palaeontologist Emily J. Rayfield and colleagues indicated that the biomechanics

Biomechanics is the study of the structure, function and motion of the mechanical aspects of biological systems, at any level from whole organisms to organs, cells and cell organelles, using the methods of mechanics. Biomechanics is a branch of ...

of ''Baryonyx'' were most similar to those of the gharial and unlike those of the American alligator

The American alligator (''Alligator mississippiensis''), sometimes referred to colloquially as a gator or common alligator, is a large crocodilian reptile native to the Southeastern United States. It is one of the two extant species in the gen ...

and more-conventional theropods, supporting a piscivorous diet for spinosaurids. Their secondary palate helped them resist bending and torsion of their tubular snouts. A 2013 beam-theory study by the British palaeontologists Andrew R. Cuff and Rayfield compared the biomechanics of CT-scanned spinosaurid snouts with those of extant crocodilians, and found the snouts of ''Baryonyx'' and ''Spinosaurus'' similar in their resistance to bending and torsion. ''Baryonyx'' was found to have relatively high resistance in the snout to dorsoventral bending compared with ''Spinosaurus'' and the gharial. The authors concluded (in contrast to the 2007 study) that ''Baryonyx'' performed differently than the gharial; spinosaurids were not exclusive piscivores, and their diet was determined by their individual size.

In a 2014 conference abstract, the American palaeontologist Danny Anduza and Fowler pointed out that grizzly bears do not gaff fish out of the water as was suggested for ''Baryonyx'', and also ruled out that the dinosaur would not have darted its head like herons, since the necks of spinosaurids were not strongly S-curved, and their eyes were not well-positioned for binocular vision

In biology, binocular vision is a type of vision in which an animal has two eyes capable of facing the same direction to perceive a single three-dimensional image of its surroundings. Binocular vision does not typically refer to vision where an ...

. Instead, they suggested the jaws would have made sideways sweeps to catch fish, like the gharial, with the hand claws probably used to stamp down and impale large fish, whereafter they manipulated them with their jaws, in a manner similar to grizzly bears and fishing cats. They did not find the teeth of spinosaurids suitable for dismembering prey, due to their lack of serrations, and suggested they would have swallowed prey whole (while noting they could also have used their claws for dismemberment). A 2016 study by the Belgian palaeontologist Christophe Hendrickx and colleagues found that adult spinosaurs could displace their mandibular rami (halves of the lower jaw) sideways when the jaw was depressed, which allowed the pharynx

The pharynx (plural: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the oesophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its st ...