Barbarossa Hayreddin Pasha on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hayreddin Barbarossa ( ar, خير الدين بربروس, Khayr al-Din Barbarus, original name: Khiḍr; tr, Barbaros Hayrettin Paşa), also known as Hızır Hayrettin Pasha, and simply Hızır Reis (c. 1466/1478 – 4 July 1546), was an Ottoman corsair and later admiral of the Ottoman Navy. Barbarossa's naval victories secured Ottoman dominance over the Mediterranean during the mid 16th century.

As the son of a soldier named Yakup, who took part in the Turkish conquest of Lesbos Born on Midilli (

All four brothers became seamen, engaged in marine affairs and international sea trade. The first brother to become involved in seamanship was Oruç, who was joined by his brother Ilyas. Later, obtaining his own ship, Khizr also began his career at sea. The brothers initially worked as sailors, but then turned privateers in the Mediterranean to counteract the privateering of the

All four brothers became seamen, engaged in marine affairs and international sea trade. The first brother to become involved in seamanship was Oruç, who was joined by his brother Ilyas. Later, obtaining his own ship, Khizr also began his career at sea. The brothers initially worked as sailors, but then turned privateers in the Mediterranean to counteract the privateering of the

Oruç was a very successful seaman. He also learned to speak Italian, Spanish, French, Greek, and Arabic early in his career. While returning from a trading expedition in

Oruç was a very successful seaman. He also learned to speak Italian, Spanish, French, Greek, and Arabic early in his career. While returning from a trading expedition in

In 1503, Oruç managed to seize three more ships and made the island of

In 1503, Oruç managed to seize three more ships and made the island of

The Spaniards ordered Abu Zayan, whom they had appointed the new ruler of

The Spaniards ordered Abu Zayan, whom they had appointed the new ruler of

With a fresh force of Turkish soldiers sent by the Ottoman sultan, Barbarossa recaptured Tlemcen in December 1518. He continued the policy of bringing

With a fresh force of Turkish soldiers sent by the Ottoman sultan, Barbarossa recaptured Tlemcen in December 1518. He continued the policy of bringing

In 1534, Barbarossa set sail from Constantinople with 80 galleys, and in April, he recaptured Coron, Patras and Lepanto from the Spaniards. In July 1534, he crossed the

In 1534, Barbarossa set sail from Constantinople with 80 galleys, and in April, he recaptured Coron, Patras and Lepanto from the Spaniards. In July 1534, he crossed the

"The Mediterranean Policy of Charles V."

A New World: Emperor Charles V and the Beginnings of Globalisation (2021): 83. He then appeared in

and once again raided Calabria. These losses prompted Venice to ask Pope Paul III to organize a " Holy League" against the Ottomans. In February 1538, Pope Paul III succeeded in assembling a Holy League (composed of the In 1540 Barbarossa led a crew of 2,000 men and captured and ransacked the town of

In 1540 Barbarossa led a crew of 2,000 men and captured and ransacked the town of

"The Jewish impact on the social and economic manifestation of the Gibraltarian identity."

(2011). He left Gibraltar after taking 75 prisoners which removed a significant percent of Gibraltar’s population, he ultimately eliminated the town of almost an entire generation of Gibraltarians. In September 1540, Emperor Charles V contacted Barbarossa and offered him to become his Admiral-in-Chief as well as the ruler of Spain's territories in North Africa, but he refused. Unable to persuade Barbarossa to switch sides, in October 1541, Charles himself laid siege to Algiers, seeking to end the corsair threat to the Spanish domains and Christian shipping in the western Mediterranean. The season was not ideal for such a campaign, and both Andrea Doria, who commanded the fleet, and Hernán Cortés, who had been asked by Charles to participate in the campaign, attempted to change the Emperor's mind but failed. Eventually, a violent storm disrupted Charles's landing operations. Andrea Doria took his fleet away into open waters to avoid being wrecked on the shore, but much of the Spanish fleet went aground. After some indecisive fighting on land, Charles had to abandon the effort and withdraw his severely battered force.

In 1543, Barbarossa headed towards Marseilles to assist France, then an ally of the Ottoman Empire, and cruised the western Mediterranean with a fleet of 210 ships (70 galleys, 40 galliots and 100 other warships carrying 14,000 Turkish soldiers, thus an overall total of 30,000 Ottoman troops). On his way, while passing through the

In 1543, Barbarossa headed towards Marseilles to assist France, then an ally of the Ottoman Empire, and cruised the western Mediterranean with a fleet of 210 ships (70 galleys, 40 galliots and 100 other warships carrying 14,000 Turkish soldiers, thus an overall total of 30,000 Ottoman troops). On his way, while passing through the

In the spring of 1544, after assaulting San Remo for the second time and landing at Borghetto Santo Spirito and

In the spring of 1544, after assaulting San Remo for the second time and landing at Borghetto Santo Spirito and

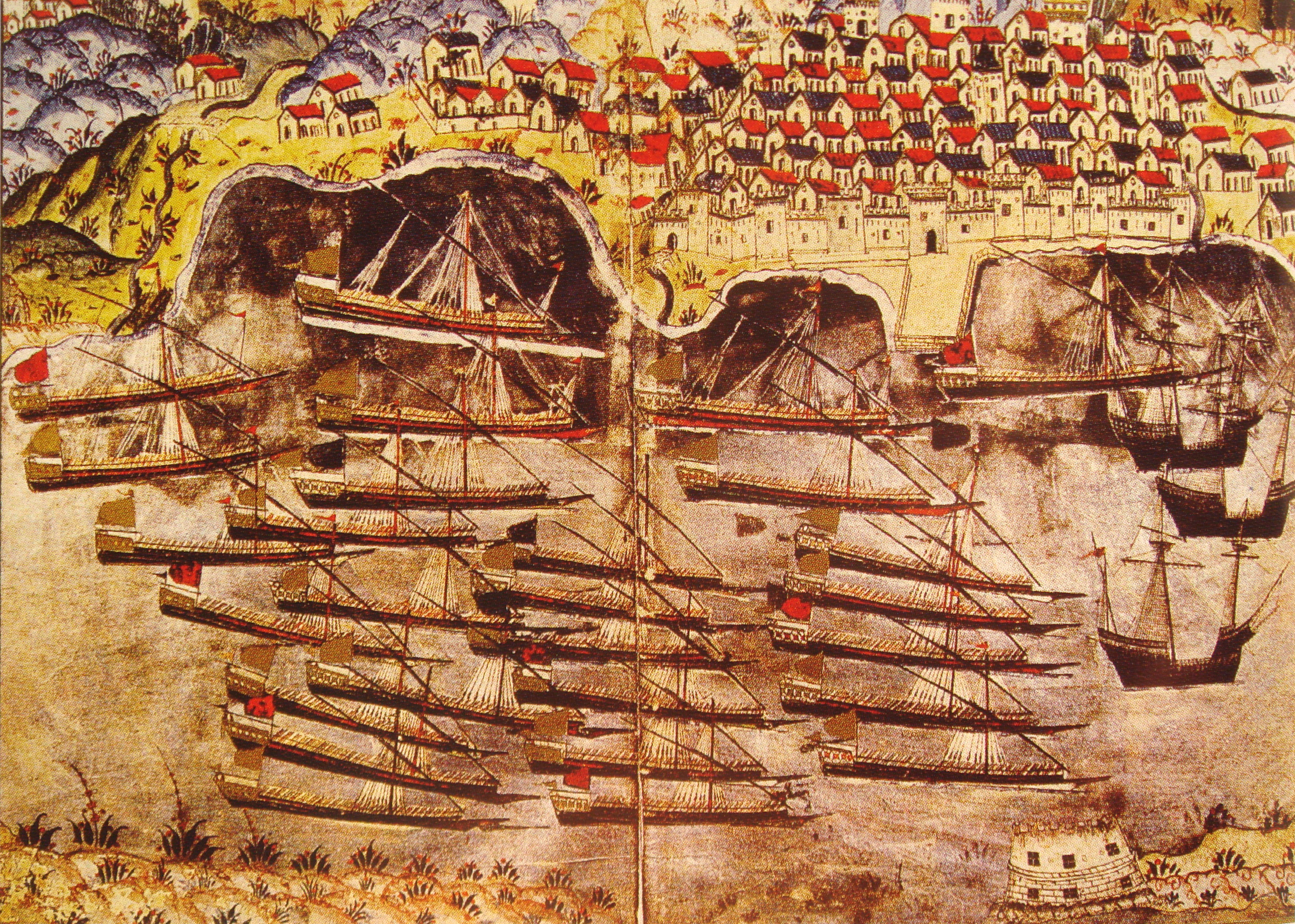

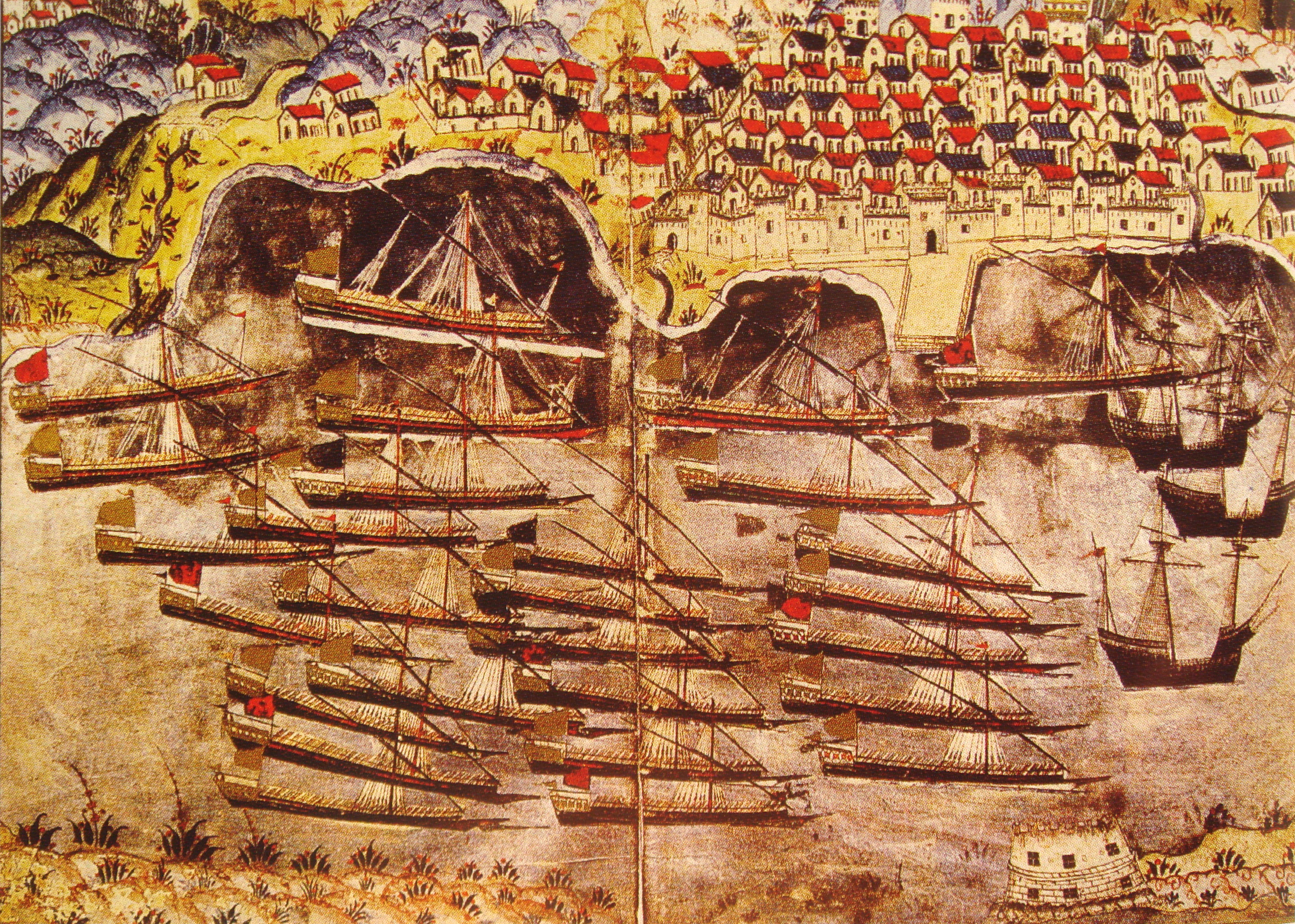

Barbarossa retired in Constantinople in 1545, leaving his son Hasan Pasha as his successor in Algiers. He then dictated his memoirs to Muradi Sinan Reis. They consist of five hand-written volumes known as ''Gazavat-ı Hayreddin Paşa'' (''Conquests of Hayreddin Pasha''). Today, they are exhibited at the

Barbarossa retired in Constantinople in 1545, leaving his son Hasan Pasha as his successor in Algiers. He then dictated his memoirs to Muradi Sinan Reis. They consist of five hand-written volumes known as ''Gazavat-ı Hayreddin Paşa'' (''Conquests of Hayreddin Pasha''). Today, they are exhibited at the

The

The  Within the four crescents are the names, from right to left, beginning at the top right, of the first four caliphs –

Within the four crescents are the names, from right to left, beginning at the top right, of the first four caliphs –

''Can it be Barbarossa now returning''

''From Tunis or Algiers or from the Isles?''

''Two hundred vessels ride upon the waves,''

''Coming from lands the rising Crescent lights:''

''O blessed ships, from what seas are ye come?'' Barbaros Boulevard starts from his mausoleum on the Bosphorus and runs up to the

Pasha, pirates and Paros

Encyclopædia Britannica

Original Gazawat by Seyyid Muradi

Hayreddin Barbarossa's tomb in Beşiktaş

(Memoirs of Hayreddin Barbarossa in Turkish) {{DEFAULTSORT:Barbarossa 1476 births 1546 deaths Muslims from the Ottoman Empire 15th-century people from the Ottoman Empire 16th-century people from the Ottoman Empire 16th-century pirates People from Lesbos Barbary pirates Kapudan Pashas Heads of state of Algeria Privateers Suleiman the Magnificent Piri Reis Ottoman Empire admirals Turks from the Ottoman Empire People from the Ottoman Empire of Albanian descent People from the Ottoman Empire of Greek descent Turkish people of Albanian descent Albanians from the Ottoman Empire Greeks from the Ottoman Empire Turkish people of Greek descent Ottoman people of the Ottoman–Venetian Wars Ottoman Navy officers Rulers of the Regency of Algiers

Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( el, Λέσβος, Lésvos ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece. It is separated from Asia Minor by the nar ...

), Khizr began his naval career as a corsair under his elder brother Oruç Reis

Oruç Reis ( ota, عروج ريس; es, Aruj; 1474 – 1518) was an Ottoman corsair who became Sultan of Algiers. The elder brother of the famous Ottoman admiral Hayreddin Barbarossa, he was born on the Ottoman island of Midilli (Lesbos i ...

. In 1516, the brothers captured Algiers from Spain, with Oruç declaring himself Sultan. Following Oruç's death in 1518, Khizr inherited his brother's nickname, "Barbarossa" ("Redbeard" in Italian). He also received the honorary name ''Hayreddin'' (from Arabic '' Khayr ad-Din'', "goodness of the faith" or "best of the faith"). In 1529, Barbarossa took the Peñón of Algiers from the Spaniards.

In 1533, Barbarossa was appointed Kapudan Pasha

The Kapudan Pasha ( ota, قپودان پاشا, modern Turkish: ), was the Grand Admiral of the navy of the Ottoman Empire. He was also known as the ( ota, قپودان دریا, links=no, modern: , "Captain of the Sea"). Typically, he was bas ...

(Grand admiral) of the Ottoman Navy by Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ ...

. He led an embassy to France in the same year, conquered Tunis in 1534, achieved a decisive victory over the Holy League at Preveza

Preveza ( el, Πρέβεζα, ) is a city in the region of Epirus, northwestern Greece, located on the northern peninsula at the mouth of the Ambracian Gulf. It is the capital of the regional unit of Preveza, which is part of the region of Epiru ...

in 1538, and conducted joint campaigns with the French in the 1540s. Barbarossa retired to Constantinople in 1545 and died the following year.

Background

Khizr was born sometime between 1466 and 1478 in Palaiokipos on the island of Midilli (Lesbos), a son of an Ottoman ''sipahi

''Sipahi'' ( ota, سپاهی, translit=sipâhi, label=Persian, ) were professional cavalrymen deployed by the Seljuks, and later the Ottoman Empire, including the land grant-holding (''timar'') provincial '' timarli sipahi'', which constituted ...

'' father, Yakup Ağa

Yakup Ağa ( ota, یعقوب آغا) or Ebu Yusuf Nurullah Yakub ( ota, ابو یوسف نورالله یعقوب), was the father of the Barbarossa Brothers, Oruç and Hızır. A Sipahi of Turkishİsmail Hâmi Danişmend, ''Osmanlı Devlet Er ...

, of

Turkish

İsmail Hâmi Danişmend, ''Osmanlı Devlet Erkânı'', pp. 172 ff. Türkiye Yayınevi (Istanbul), 1971.''Khiḍr was one of four sons of a Turk from the island of Lesbos.'', "Barbarossa", ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', 1963, p. 147.

Angus Konstam, ''Piracy: The Complete History'', Osprey Publishing, 2008, , p. 80. or Albanian

origin from Giannitsa

Giannitsa ( el, Γιαννιτσά , in English also Yannitsa, Yenitsa) is the largest city in the regional unit of Pella and the capital of the Pella municipality, in the region of Central Macedonia in northern Greece.

The municipal unit Gian ...

(now Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

), and an Orthodox Christian Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

mother, Katerina, from Mytilene

Mytilene (; el, Μυτιλήνη, Mytilíni ; tr, Midilli) is the capital of the Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University o ...

(also Lesbos). His mother was a widow of an Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pa ...

priest. The couple married and had two daughters and four sons: Ishak, Oruç, Khizr and Ilyas. Yakup took part in the Ottoman conquest of Lesbos

The Ottoman conquest of Lesbos took place in September 1462. The Ottoman Empire, under Sultan Mehmed II, laid siege to the island's capital, Mytilene. After its surrender, the other forts of the island surrendered as well. The event put an end to ...

in 1462 from the Genoese Gattilusio dynasty (who held the hereditary title of Lord of Lesbos between 1355 and 1462) and as a reward, was granted the fief of the village of Bonova on the island. He became an established potter and purchased a boat to trade his products with. The four sons helped their father with his business, but not much is known about the daughters. At first Oruç helped with the boat, while Khizr helped with the pottery.

Early career

All four brothers became seamen, engaged in marine affairs and international sea trade. The first brother to become involved in seamanship was Oruç, who was joined by his brother Ilyas. Later, obtaining his own ship, Khizr also began his career at sea. The brothers initially worked as sailors, but then turned privateers in the Mediterranean to counteract the privateering of the

All four brothers became seamen, engaged in marine affairs and international sea trade. The first brother to become involved in seamanship was Oruç, who was joined by his brother Ilyas. Later, obtaining his own ship, Khizr also began his career at sea. The brothers initially worked as sailors, but then turned privateers in the Mediterranean to counteract the privateering of the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

(Knights of St John) who were based on the island of Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

( until 1522). Oruç and Ilyas operated in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

, between Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

, Syria, and Egypt. Khizr operated in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

and based his operations mostly in Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

. Ishak, the eldest, remained on Mytilene

Mytilene (; el, Μυτιλήνη, Mytilíni ; tr, Midilli) is the capital of the Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University o ...

and was involved with the financial affairs of the family business.

Death of Ilyas, captivity, and liberation of Oruç

Oruç was a very successful seaman. He also learned to speak Italian, Spanish, French, Greek, and Arabic early in his career. While returning from a trading expedition in

Oruç was a very successful seaman. He also learned to speak Italian, Spanish, French, Greek, and Arabic early in his career. While returning from a trading expedition in Tripoli, Lebanon

Tripoli ( ar, طرابلس/ ALA-LC: ''Ṭarābulus'', Lebanese Arabic: ''Ṭrablus'') is the largest city in northern Lebanon and the second-largest city in the country. Situated north of the capital Beirut, it is the capital of the North Gove ...

, with his younger brother, Ilyas, they were attacked by the Knights of St John

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

.

Ilyas was killed in the fight, and Oruç was wounded. Their father's boat was captured, and Oruç was taken as a prisoner and detained in Bodrum Castle

Bodrum Castle ( tr, Bodrum Kalesi) is a historical fortification located in southwest Turkey in the port city of Bodrum, built from 1402 onwards, by the Knights of St John (Knights Hospitaller) as the ''Castle of St. Peter'' or ''Petronium''. A t ...

at Bodrum

Bodrum () is a port city in Muğla Province, southwestern Turkey, at the entrance to the Gulf of Gökova. Its population was 35,795 at the 2012 census, with a total of 136,317 inhabitants residing within the district's borders. Known in ancient ...

for nearly three years. Upon learning the location of his brother, Khizr went to Bodrum and managed to help Oruç escape.

Oruç, the corsair

Oruç later went toAntalya

la, Attalensis grc, Ἀτταλειώτης

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 07xxx

, area_code = (+90) 242

, registration_plate = 07

, blank_name = Licence plate

...

, where he was given 18 galleys by Şehzade Korkut, an Ottoman prince and governor of the city, and charged with fighting against the Knights of St John, who were inflicting serious damage on Ottoman shipping and trade. In the following years, when Korkut became governor of Manisa

Manisa (), historically known as Magnesia, is a city in Turkey's Aegean Region and the administrative seat of Manisa Province.

Modern Manisa is a booming center of industry and services, advantaged by its closeness to the international port ci ...

, he gave Oruç a larger fleet of 24 galleys at the port of İzmir

İzmir ( , ; ), also spelled Izmir, is a metropolitan city in the western extremity of Anatolia, capital of the province of the same name. It is the third most populous city in Turkey, after Istanbul and Ankara and the second largest urban aggl ...

and ordered him to participate in the Ottoman naval expedition to Apulia in Italy, where Oruç bombarded several coastal castles and captured two ships.

On his way back to Lesbos, he stopped at Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poin ...

and captured three galleons and another ship. Reaching Mytilene

Mytilene (; el, Μυτιλήνη, Mytilíni ; tr, Midilli) is the capital of the Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University o ...

with these captured vessels, Oruç learned that Korkut, who was the brother of the new Ottoman sultan Selim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite las ...

, had fled to Egypt to avoid being killed because of succession disputes – a common practice at that time.

Fearing trouble due to his well-known association with the exiled Ottoman prince, Oruç sailed to Egypt, where he met Korkut in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the Capital city, capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, List of ...

and managed to get an audience with the Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

Sultan Qansuh al-Ghawri, who gave him another ship and entrusted him with the task of raiding the coasts of Italy and the islands of the Mediterranean that were controlled by Christians. After spending the winter in Cairo, he set sail from Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

and frequently operated along the coasts of Liguria

it, Ligure

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

and Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

.

Khizr's career under Oruç

In 1503, Oruç managed to seize three more ships and made the island of

In 1503, Oruç managed to seize three more ships and made the island of Djerba

Djerba (; ar, جربة, Jirba, ; it, Meninge, Girba), also transliterated as Jerba or Jarbah, is a Tunisian island and the largest island of North Africa at , in the Gulf of Gabès, off the coast of Tunisia. It had a population of 139,544 ...

his new base, thus moving his operations to the Western Mediterranean. Khizr joined Oruç at Djerba. In 1504, the brothers contacted Abu Abdallah Muhammad IV al-Mutawakkil, ruler of Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

, and asked permission to use the strategically located port of La Goulette

La Goulette (, it, La Goletta), in Arabic Halq al-Wadi ( '), is a municipality and the port of Tunis, Tunisia.

La Goulette is located at around on a sandbar between Lake Tūnis and the Gulf of Tunis. The port, located 12km east of Tunis, is th ...

for their operations.

They were granted the right to do so on the condition of giving one-third of their spoils to the sultan. Oruç, in command of small

galiot

A galiot, galliot or galiote, was a small galley boat propelled by sail or oars. There are three different types of naval galiots that sailed on different seas.

A ''galiote'' was a type of French flat-bottom river boat or barge and also a flat- ...

s, captured two much larger papal galleys near the island of Elba

Elba ( it, isola d'Elba, ; la, Ilva) is a Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino on the Italian mainland, and the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago. It is also part of the Arcipelago Toscano Nationa ...

. Later, near Lipari

Lipari (; scn, Lìpari) is the largest of the Aeolian Islands in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the northern coast of Sicily, southern Italy; it is also the name of the island's main town and ''comune'', which is administratively part of the Metropo ...

, the two brothers captured a Sicilian warship, the ''Cavalleria'', with 380 Spanish soldiers and 60 Spanish knights from Aragon on board, who were on their way from Spain to Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

. In 1505, they raided the coasts of Calabria. These exploits increased their fame, and they were joined by several other well-known Muslim corsairs, including Kurtoğlu (known in the West as Curtogoli). In 1508, they raided the coasts of Liguria, particularly Diano Marina

Diano Marina ( lij, A Maina de Dian, or simply ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Imperia in the Italian region of Liguria, located about southwest of Genoa and about northeast of Imperia.

Geography

The municipality of Diano ...

.

In 1509, Ishak also left Mytilene and joined his brothers at La Goulette. The fame of Oruç increased when, between 1504 and 1510, he transported Muslim Mudéjar

Mudéjar ( , also , , ca, mudèjar , ; from ar, مدجن, mudajjan, subjugated; tamed; domesticated) refers to the group of Muslims who remained in Iberia in the late medieval period despite the Christian reconquest. It is also a term for ...

s from Christian Spain to North Africa. His efforts of helping the Muslims of Spain in need and transporting them to safer lands earned him the honorific name Baba Oruç (Father Oruç), which eventually – due to the similarity in sound – evolved in Spain, France, and Italy into Barbarossa (meaning "Redbeard" in Italian).

In 1510, the three brothers raided Capo Passero

Capo Passero or Cape Passaro ( scn, Capu Pàssaru; Greek: ; Latin: Pachynus or Pachynum) is a celebrated promontory of Sicily, forming the extreme southeastern point of the whole island, and one of the three promontories which were supposed to ha ...

in Sicily and repulsed Spanish attacks on Bougie, Oran and Algiers. In August 1511, they raided the areas around Reggio Calabria in southern Italy. In August 1512, the exiled ruler of Bougie invited the brothers to drive out the Spaniards, and during the battle Oruç lost his left arm. This incident earned him the nickname ''Gümüş Kol'' ("Silver Arm" in Turkish), in reference to the silver prosthetic device that he used in place of his missing limb.

Later that same year, the brothers raided the coasts of Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a "historical nationality". The t ...

, capturing a galliot of the Lomellini family of Genoa, which owned Tabarca island. They subsequently landed at Menorca

Menorca or Minorca (from la, Insula Minor, , smaller island, later ''Minorica'') is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. Its name derives from its size, contrasting it with nearby Majorca. Its capi ...

and captured a coastal castle and then headed towards Liguria, where they captured four Genoese galleys near Genoa. The Genoese sent a fleet to liberate their ships, but the brothers captured their flagship as well. After capturing a total of 23 ships in less than a month, the brothers sailed back to La Goulette, where they built three more galliots and a gunpowder production facility.

In 1513, they launched a raid on Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

, where they captured four ships, and then headed for Alicante

Alicante ( ca-valencia, Alacant) is a city and municipality in the Valencian Community, Spain. It is the capital of the province of Alicante and a historic Mediterranean port. The population of the city was 337,482 , the second-largest in t ...

and captured a Spanish galley near Málaga. In 1513–14, the brothers engaged the Spanish fleet on several other occasions and moved to their new base to Cherchell, east of Algiers. In 1514, with 12 galliots and 1,000 Turks, they destroyed two Spanish fortresses at Bougie, and when the Spanish fleet under the command of Miguel de Gurrea, viceroy of Majorca, arrived as reinforcement, they headed towards Ceuta

Ceuta (, , ; ar, سَبْتَة, Sabtah) is a Spanish autonomous city on the north coast of Africa.

Bordered by Morocco, it lies along the boundary between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. It is one of several Spanish territorie ...

and raided that city before capturing Jijel

Jijel ( ar, جيجل), the classical Igilgili, is the capital of Jijel Province in north-eastern Algeria. It is flanked by the Mediterranean Sea in the region of Corniche Jijelienne and had a population of 131,513 in 2008.

Jijel is the administr ...

in Algeria, which was under Genoese control. They later captured Mahdiya in Tunisia. Afterwards they raided the coasts of Sicily, Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

, the Balearic Islands and the Spanish mainland, capturing three large ships there.

In 1515, they captured several galleons, a galley and three barques at Majorca. Still in 1515, Oruç sent precious gifts to the Ottoman Sultan Selim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite las ...

, who, in return, sent him two galleys and two swords encrusted with diamonds. In 1516, joined by Kurtoğlu (Curtogoli), the brothers besieged the Castle of Elba, before heading once more towards Liguria, where they captured 12 ships and damaged 28 others.

Rulers of Algiers

In 1516, the three brothers succeeded in capturingJijel

Jijel ( ar, جيجل), the classical Igilgili, is the capital of Jijel Province in north-eastern Algeria. It is flanked by the Mediterranean Sea in the region of Corniche Jijelienne and had a population of 131,513 in 2008.

Jijel is the administr ...

and Algiers from the Spaniards and eventually assumed control over the city and surrounding region, forcing the previous ruler, Abu Hamo Musa III of the Beni Ziyad dynasty, to flee.

The Spaniards of Algiers sought refuge on the island of Peñón

A ''peñón'' (, "rock", pl. ''peñones'') is a term for certain offshore rocky island forts established by the Spanish Empire (especially in Africa). Several are still part of the ''plazas de soberanía'' ("places of sovereignty") of Spain in N ...

and asked Charles V, King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor to intervene, but the Spanish fleet failed to expel the brothers from Algiers.

For Oruç, the best protection against Spain was to join the Ottoman Empire, his homeland and Spain's main rival. For this, he had to relinquish his title of Sultan of Algiers to the Ottomans. He did this in 1517 and offered Algiers to the Ottoman Sultan Selim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite las ...

. The Sultan accepted Algiers as an Ottoman ''sanjak

Sanjaks (liwāʾ) (plural form: alwiyāʾ)

* Armenian: նահանգ (''nahang''; meaning "province")

* Bulgarian: окръг (''okrǔg''; meaning "county", "province", or "region")

* el, Διοίκησις (''dioikēsis'', meaning "province" ...

'' ("province"), appointed Oruç Governor of Algiers and Chief Sea Governor of the Western Mediterranean, and promised to support him with janissaries, galleys and cannon.

Final engagements and death of Oruç and Ishak

The Spaniards ordered Abu Zayan, whom they had appointed the new ruler of

The Spaniards ordered Abu Zayan, whom they had appointed the new ruler of Tlemcen

Tlemcen (; ar, تلمسان, translit=Tilimsān) is the second-largest city in northwestern Algeria after Oran, and capital of the Tlemcen Province. The city has developed leather, carpet, and textile industries, which it exports through the p ...

and Oran, to attack Oruç Reis overland, but Oruç learned of the plan and pre-emptively attacked Tlemcen, capturing the city and executing Abu Zayan in the Fall of Tlemcen (1517)

The Fall of Tlemcen occurred in 1518, when the Ottoman admiral Oruç Barbarossa captured the city of Tlemcen from its sultan, Abu Zayan, the last member of the Banu Zayan lineage."The town of Tenes fell into the hands of the brothers, with an ...

. The only survivor of Abu Zayan's dynasty was Sheikh Buhammud, who escaped to Oran and called for Spain's assistance.

After consolidating his power and declaring himself Sultan of Algiers, Oruç sought to expand his territory inland and took Miliana

Miliana ( ar, مليانة) is a commune in Aïn Defla Province in northwestern Algeria. It is the administrative center of the daïra, or district, of the same name. It is approximately southwest of the Algerian capital, Algiers.r/sup>, which ...

, Medea

In Greek mythology, Medea (; grc, Μήδεια, ''Mēdeia'', perhaps implying "planner / schemer") is the daughter of King Aeëtes of Colchis, a niece of Circe and the granddaughter of the sun god Helios. Medea figures in the myth of Jason an ...

and Ténès

Ténès ( ar, تنس; from Berber TNS 'camping') is a town in Algeria located around 200 kilometers west of the capital Algiers. , it has a population of 65,000 people.

History

Ténès was founded as a Phoenician port in or before the 8th cen ...

. He became known for fitting sails to cannons for transport through the deserts of North Africa. In 1517, the brothers raided Capo Limiti, and, later, Capo Rizzuto, Calabria.

In May 1518, Emperor Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infa ...

arrived at Oran and was received at the port by Sheikh Buhammud and the Spanish governor of the city, Diego de Córdoba, marquis of Comares, who commanded a force of 10,000 Spanish soldiers. Joined by thousands of local Bedouins

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert and Ar ...

, the Spaniards marched overland towards Tlemcen. Oruç and Ishak awaited them in the city with 1,500 Turkish and 5,000 Moorish soldiers. They defended Tlemcen for 20 days, but were eventually killed in combat by the forces of Garcia de Tineo.

Algiers annexed by the Ottoman Empire

After the death of his older brother and feeling that his position was under threat, Khayr al-Din contactedSelim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite las ...

, offered his allegiance and obtained Ottoman assistance in 1519. Given the title of '' Beylerbey'' by Sultan Selim I, along with janissaries, galleys and cannon, he inherited his brother's position, his name (Barbarossa) and his mission.

Later career

Pasha of Algiers

With a fresh force of Turkish soldiers sent by the Ottoman sultan, Barbarossa recaptured Tlemcen in December 1518. He continued the policy of bringing

With a fresh force of Turkish soldiers sent by the Ottoman sultan, Barbarossa recaptured Tlemcen in December 1518. He continued the policy of bringing mudéjar

Mudéjar ( , also , , ca, mudèjar , ; from ar, مدجن, mudajjan, subjugated; tamed; domesticated) refers to the group of Muslims who remained in Iberia in the late medieval period despite the Christian reconquest. It is also a term for ...

s from Spain to North Africa, thereby assuring himself of a sizable following of grateful and loyal Muslims who harbored an intense hatred for Spain. He captured Bône

Annaba ( ar, عنّابة, "Place of the Jujubes"; ber, Aânavaen), formerly known as Bon, Bona and Bône, is a seaport city in the northeastern corner of Algeria, close to the border with Tunisia. Annaba is near the small Seybouse River ...

, and in 1519, he defeated a Spanish-Italian army that tried to recapture Algiers. In a separate incident, he sank a Spanish ship and captured eight others. Still in 1519, he raided Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bor ...

, Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

and the Îles d'Hyères in southern France. In 1521, he raided the Balearic Islands and later captured several Spanish ships returning from the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

off the coast of Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

.

In 1522, he sent his ships, under the command of Kurtoğlu, to participate in the Ottoman conquest of Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

, which resulted in the departure of the Knights of St John

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

from that island on 1 January 1523.

In June 1525, he raided the coasts of Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

. In May 1526, he landed at Crotone in Calabria and sacked the city, sank a Spanish galley and a Spanish fusta

The fusta or fuste (also called foist) was a narrow, light and fast ship with shallow draft, powered by both oars and sail—in essence a small galley. It typically had 12 to 18 two-man rowing benches on each side, a single mast with a lateen ( ...

in the harbor, then assaulted Castignano in Marche on the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

and later landed at Cape Spartivento. In June 1526, he landed at Reggio Calabria and later destroyed the fort at the port of Messina. He then appeared on the coasts of Tuscany

it, Toscano (man) it, Toscana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Citizenship

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 = Italian

, demogra ...

, but retreated after seeing the fleet of Andrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; lij, Drîa Döia ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was a Genoese statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

As the ruler of Genoa, Doria reformed the Re ...

and the Knights of St John off the coast of Piombino

Piombino is an Italian town and ''comune'' of about 35,000 inhabitants in the province of Livorno (Tuscany). It lies on the border between the Ligurian Sea and the Tyrrhenian Sea, in front of Elba Island and at the northern side of Maremma.

Ove ...

.

In July 1526, Barbarossa appeared once again in Messina and raided the coasts of Campania

(man), it, Campana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demog ...

. In 1527, he raided many ports and castles on the coasts of Italy and Spain. In May 1529, he captured the Spanish fort on the island of Peñón of Algiers

Peñón of Algiers ( es, Peñón de Argel, ) was a small islet off the coast of Algiers, fortified by the Kingdom of Spain during the 16th century. The islet was connected to the African continent to form a seawall and the harbour of Algiers.

Hist ...

. In August 1529, he attacked the Mediterranean coasts of Spain, and later, answering Andalusia's requests for help in crossing the Strait of Gibraltar, he transported 70,000 mudéjar

Mudéjar ( , also , , ca, mudèjar , ; from ar, مدجن, mudajjan, subjugated; tamed; domesticated) refers to the group of Muslims who remained in Iberia in the late medieval period despite the Christian reconquest. It is also a term for ...

s to Algiers in seven consecutive journeys.

In January 1530, he again raided the coasts of Sicily and, in March and June of that year, the Balearic Islands and Marseilles. In July 1530, he appeared along the coasts of the Provence and Liguria

it, Ligure

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, capturing two Genoese ships. In August 1530, he raided the coasts of Sardinia and, in October, appeared at Piombino

Piombino is an Italian town and ''comune'' of about 35,000 inhabitants in the province of Livorno (Tuscany). It lies on the border between the Ligurian Sea and the Tyrrhenian Sea, in front of Elba Island and at the northern side of Maremma.

Ove ...

, capturing a barque

A barque, barc, or bark is a type of sailing vessel with three or more masts having the fore- and mainmasts rigged square and only the mizzen (the aftmost mast) rigged fore and aft. Sometimes, the mizzen is only partly fore-and-aft rigged, b ...

from Viareggio

Viareggio () is a city and ''comune'' in northern Tuscany, Italy, on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea. With a population of over 62,000, it is the second largest city within the province of Lucca, after Lucca.

It is known as a seaside resort as ...

and three French galleon

Galleons were large, multi-decked sailing ships first used as armed cargo carriers by European states from the 16th to 18th centuries during the age of sail and were the principal vessels drafted for use as warships until the Anglo-Dutch W ...

s before capturing two more ships off Calabria. In December 1530, he captured the Castle of Cabrera, in the Balearic Islands, and began to use the island as a logistic base for his operations on the area.

In 1531, he encountered Andrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; lij, Drîa Döia ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was a Genoese statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

As the ruler of Genoa, Doria reformed the Re ...

, who had been appointed by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor to recapture Jijel

Jijel ( ar, جيجل), the classical Igilgili, is the capital of Jijel Province in north-eastern Algeria. It is flanked by the Mediterranean Sea in the region of Corniche Jijelienne and had a population of 131,513 in 2008.

Jijel is the administr ...

and the Peñón of Algiers, and repulsed a Spanish-Genoese fleet of 40 galleys. Still in 1531, he raided the island of Favignana

Favignana ( scn, Faugnana) is a ''comune'' including three islands (Favignana, Marettimo and Levanzo) of the Aegadian Islands, southern Italy. It is situated approximately west of the coast of Sicily, between Trapani and Marsala, the coastal are ...

, where the flagship of the Maltese Knights under the command of unsuccessfully attacked his fleet. Barbarossa then sailed eastwards and landed in Calabria and Apulia. On the way back to Algiers, he sank a ship of the Maltese Knights near Messina before assaulting Tripoli, which had been given to the Knights of St John by Charles V in 1530. In October 1531, he again raided the coasts of Spain. He also pillaged the Îles d'Hyères during the same year.

In 1532, during Suleiman I's expedition to Habsburg Austria, Andrea Doria captured Coron, Patras and Lepanto on the coasts of the Morea

The Morea ( el, Μορέας or ) was the name of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. The name was used for the Byzantine province known as the Despotate of the Morea, by the Ottom ...

(Peloponnese). In response, Suleiman sent the forces of Yahya Pashazade Mehmed Bey, who recaptured these cities, but the event made Suleiman realize the importance of having a powerful commander at sea. He summoned Barbarossa to Istanbul, who set sail in August 1532. Having raided Sardinia, Bonifacio in Corsica, and the islands of Montecristo

Montecristo, also Monte Cristo (, ) and formerly Oglasa ( grc, Ὠγλάσσα, Ōglássa), is an island in the Tyrrhenian Sea and part of the Tuscan Archipelago. Administratively it belongs to the municipality of Portoferraio in the province ...

, Elba and Lampedusa

Lampedusa ( , , ; scn, Lampidusa ; grc, Λοπαδοῦσσα and Λοπαδοῦσα and Λοπαδυῦσσα, Lopadoûssa; mt, Lampeduża) is the largest island of the Italian Pelagie Islands in the Mediterranean Sea.

The ''comune'' of L ...

, he captured 18 galleys near Messina and learned from the captured prisoners that Doria was headed to Preveza

Preveza ( el, Πρέβεζα, ) is a city in the region of Epirus, northwestern Greece, located on the northern peninsula at the mouth of the Ambracian Gulf. It is the capital of the regional unit of Preveza, which is part of the region of Epiru ...

.

Barbarossa proceeded to raid the nearby coasts of Calabria and then sailed towards Preveza. Doria's forces fled after a short battle, but only after Barbarossa had captured seven of their galleys. He arrived at Preveza with a total of 44 galleys, but sent 25 of them back to Algiers and headed to Constantinople with 19 ships. There, he was received by Sultan Suleiman at Topkapı Palace

The Topkapı Palace ( tr, Topkapı Sarayı; ota, طوپقپو سرايى, ṭopḳapu sarāyı, lit=cannon gate palace), or the Seraglio, is a large museum in the east of the Fatih district of Istanbul in Turkey. From the 1460s to the complet ...

. Suleiman appointed Barbarossa ''Kapudan-i Derya

The Kapudan Pasha ( ota, قپودان پاشا, modern Turkish: ), was the Grand Admiral of the navy of the Ottoman Empire. He was also known as the ( ota, قپودان دریا, links=no, modern: , "Captain of the Sea"). Typically, he was based ...

'' ("Grand Admiral") of the Ottoman Navy and '' Beylerbey'' ("Chief Governor") of North Africa. Barbarossa was also given the government of the ''sanjak

Sanjaks (liwāʾ) (plural form: alwiyāʾ)

* Armenian: նահանգ (''nahang''; meaning "province")

* Bulgarian: окръг (''okrǔg''; meaning "county", "province", or "region")

* el, Διοίκησις (''dioikēsis'', meaning "province" ...

'' ("province") of Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

and those of Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poin ...

and Chios

Chios (; el, Χίος, Chíos , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greek island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. Chios is notable for its exports of masti ...

in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

.

Diplomacy with France

In 1533, Barbarossa sent an embassy to the king of France, Francis I, the Ottoman embassy to France (1533). Francis I would in turn dispatch Antonio Rincon to Barbarossa in North Africa and then toSuleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ ...

in Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

. Following a second embassy, the Ottoman embassy to France (1534), Francis I sent his ambassador Jehan de la Forest to Hayreddin Barbarossa, asking for his naval support against the Habsburg:

Kapudan-i Derya of the Ottoman Navy

In 1534, Barbarossa set sail from Constantinople with 80 galleys, and in April, he recaptured Coron, Patras and Lepanto from the Spaniards. In July 1534, he crossed the

In 1534, Barbarossa set sail from Constantinople with 80 galleys, and in April, he recaptured Coron, Patras and Lepanto from the Spaniards. In July 1534, he crossed the Strait of Messina

The Strait of Messina ( it, Stretto di Messina, Sicilian: Strittu di Missina) is a narrow strait between the eastern tip of Sicily ( Punta del Faro) and the western tip of Calabria ( Punta Pezzo) in Southern Italy. It connects the Tyrrhenian S ...

and raided the Calabrian coasts, capturing a substantial number of ships around Reggio Calabria as well as the Castle of San Lucido. He later destroyed the port of Cetraro

Cetraro ( Calabrian: ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Cosenza in the Calabria region of southern Italy.

Waste dumping

The 'Ndrangheta, an Italian mafia syndicate, has been accused by pentito Francesco Fonti, a former member of ' ...

and the ships harbored there.

Also in July 1534, he appeared in Campania

(man), it, Campana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demog ...

and sacked the islands of Capri and Procida

Procida (; nap, Proceta ) is one of the Flegrean Islands off the coast of Naples in southern Italy. The island is between Cape Miseno and the island of Ischia. With its tiny satellite island of Vivara, it is a ''comune'' of the Metropolitan Ci ...

before bombarding the ports in the Gulf of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, where 7,800 captives were taken.Servantie, Alain"The Mediterranean Policy of Charles V."

A New World: Emperor Charles V and the Beginnings of Globalisation (2021): 83. He then appeared in

Lazio

it, Laziale

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, shelled Gaeta and in August landed at Villa Santa Lucia, Sperlonga

Sperlonga (locally ) is a coastal town in the province of Latina, Italy, about halfway between Rome and Naples. It is best known for the ancient Roman sea grotto discovered in the grounds of the Villa of Tiberius containing the important and spect ...

, Fondi

Fondi ( la, Fundi; Southern Laziale: ''Fùnn'') is a city and ''comune'' in the province of Latina, Lazio, central Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. I ...

, Terracina

Terracina is an Italian city and ''comune'' of the province of Latina, located on the coast southeast of Rome on the Via Appia ( by rail). The site has been continuously occupied since antiquity.

History Ancient times

Terracina appears in anci ...

and Ostia on the River Tiber

The Tiber ( ; it, Tevere ; la, Tiberis) is the third-longest List of rivers of Italy, river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where ...

, causing the church bells in Rome to sound the alarm. In Sperlonga

Sperlonga (locally ) is a coastal town in the province of Latina, Italy, about halfway between Rome and Naples. It is best known for the ancient Roman sea grotto discovered in the grounds of the Villa of Tiberius containing the important and spect ...

he took 10,000 captives and when he arrived in Fondi the janissaries entered the city through the main gates and completely ransacked the palace of Giulia Gonzaga. He then sacked, torched and destroyed Vallecorsa slaughtering some townspeople and taking others captive. He sailed south, appearing at Ponza

Ponza (Italian: ''isola di Ponza'' ) is the largest island of the Italian Pontine Islands archipelago, located south of Cape Circeo in the Tyrrhenian Sea. It is also the name of the commune of the island, a part of the province of Latina in th ...

, Sicily and Sardinia, before capturing Tunis in August 1534 and sending the Hafsid

The Hafsids ( ar, الحفصيون ) were a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Berber descentC. Magbaily Fyle, ''Introduction to the History of African Civilization: Precolonial Africa'', (University Press of America, 1999), 84. who ruled Ifriqiya (western ...

Sultan Mulay Hassan fleeing.

He also captured Tunis' strategic port of La Goulette the same year.

Charles dispatched an agent to offer Barbarossa "the lordship of North Africa" for his changed loyalty, or if that failed, to assassinate him. However, upon rejecting the offer, Barbarossa decapitated the agent with a scimitar

A scimitar ( or ) is a single-edged sword with a convex curved blade associated with Middle Eastern, South Asian, or North African cultures. A European term, ''scimitar'' does not refer to one specific sword type, but an assortment of different ...

.

Mulei Hassan asked Emperor Charles V for help in recovering his kingdom, and a Spanish-Italian force of 300 galleys and 24,000 soldiers recaptured Tunis as well as Bône

Annaba ( ar, عنّابة, "Place of the Jujubes"; ber, Aânavaen), formerly known as Bon, Bona and Bône, is a seaport city in the northeastern corner of Algeria, close to the border with Tunisia. Annaba is near the small Seybouse River ...

and Mahdiya in 1535. Recognizing the futility of armed resistance, Barbarossa had abandoned Tunis well before the arrival of the invaders, sailing away into the Tyrrhenian Sea

The Tyrrhenian Sea (; it, Mar Tirreno , french: Mer Tyrrhénienne , sc, Mare Tirrenu, co, Mari Tirrenu, scn, Mari Tirrenu, nap, Mare Tirreno) is part of the Mediterranean Sea off the western coast of Italy. It is named for the Tyrrhenian pe ...

, where he bombarded ports, landed once again at Capri and reconstructed a fort (which still today carries his name) after largely destroying it during the siege of the island. He then sailed to Algiers, from where he raided the coastal towns of Spain, destroyed the ports of Majorca and Menorca

Menorca or Minorca (from la, Insula Minor, , smaller island, later ''Minorica'') is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. Its name derives from its size, contrasting it with nearby Majorca. Its capi ...

, captured several Spanish and Genoese galleys and liberated their Muslim oar slaves. In September 1535, he repulsed another Spanish attack on Tlemcen

Tlemcen (; ar, تلمسان, translit=Tilimsān) is the second-largest city in northwestern Algeria after Oran, and capital of the Tlemcen Province. The city has developed leather, carpet, and textile industries, which it exports through the p ...

.

In 1536, Barbarossa was called back to Constantinople to take command of 200 ships in a naval attack on the Habsburg Kingdom of Naples. In July 1537, he landed at Otranto

Otranto (, , ; scn, label=Salentino, Oṭṛàntu; el, label= Griko, Δερεντό, Derentò; grc, Ὑδροῦς, translit=Hudroûs; la, Hydruntum) is a coastal town, port and ''comune'' in the province of Lecce (Apulia, Italy), in a ferti ...

and captured the city, as well as the Fortress of Castro and the city of Ugento

Ugento (Salentino: ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Lecce, Apulia, southern Italy. It has a small harbour on the Gulf of Taranto of the Ionian Sea.

History

The city is the ancient ''Uxentum'', and claims to have been founded by Uxen ...

in Apulia.

In August 1537, Lütfi Pasha

Lütfi Pasha ( ota, لطفى پاشا, ''Luṭfī Paşa''; Modern Turkish: ''Lütfi Paşa'', more fully ''Damat Çelebi Lütfi Paşa''; 1488 – 27 March 1564, Didymoteicho) was an Ottoman Albanian statesman, general, and Grand Vizier of the O ...

and Barbarossa led a huge Ottoman force that captured the Aegean and Ionian islands belonging to the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

, namely Syros

Syros ( el, Σύρος ), also known as Siros or Syra, is a Greek island in the Cyclades, in the Aegean Sea. It is south-east of Athens. The area of the island is and it has 21,507 inhabitants (2011 census).

The largest towns are Ermoupoli, An ...

, Aegina

Aegina (; el, Αίγινα, ''Aígina'' ; grc, Αἴγῑνα) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina, the mother of the hero Aeacus, who was born on the island and ...

, Ios

iOS (formerly iPhone OS) is a mobile operating system created and developed by Apple Inc. exclusively for its hardware. It is the operating system that powers many of the company's mobile devices, including the iPhone; the term also include ...

, Paros

Paros (; el, Πάρος; Venetian: ''Paro'') is a Greek island in the central Aegean Sea. One of the Cyclades island group, it lies to the west of Naxos, from which it is separated by a channel about wide. It lies approximately south-east of ...

, Tinos

Tinos ( el, Τήνος ) is a Greek island situated in the Aegean Sea. It is located in the Cyclades archipelago. The closest islands are Andros, Delos, and Mykonos. It has a land area of and a 2011 census population of 8,636 inhabitants.

Tinos ...

, Karpathos

Karpathos ( el, Κάρπαθος, ), also Carpathos, is the second largest of the Greek Dodecanese islands, in the southeastern Aegean Sea. Together with the neighboring smaller Saria Island it forms the municipality of Karpathos, which is part o ...

, Kasos, Kythira

Kythira (, ; el, Κύθηρα, , also transliterated as Cythera, Kythera and Kithira) is an island in Greece lying opposite the south-eastern tip of the Peloponnese peninsula. It is traditionally listed as one of the seven main Ionian Islands ...

, and Naxos

Naxos (; el, Νάξος, ) is a Greek island and the largest of the Cyclades. It was the centre of archaic Cycladic culture. The island is famous as a source of emery, a rock rich in corundum, which until modern times was one of the best ab ...

. In the same year, Barbarossa raided Corfu and obliterated the agricultural cultivations of the island while enslaving nearly all the population of the countryside. However, the Old Fortress of Corfu was well defended by a 4,000-strong Venetian garrison with 700 guns, and when several assaults failed to capture the fortifications, the Turks reluctantly re-embarkedHistory of Corfuand once again raided Calabria. These losses prompted Venice to ask Pope Paul III to organize a " Holy League" against the Ottomans. In February 1538, Pope Paul III succeeded in assembling a Holy League (composed of the

Papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

, Spain, the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

, the Republic of Venice and the Maltese Knights) against the Ottomans, but Barbarossa's forces led by Sinan Reis

Sinan Reis, also ''Ciphut Sinan'', ( he, סנאן ראיס, ''Sinan Rais''; ar, سنان ريس, ''Sinan Rayyis'';) "Sinan the Chief", and pt, Sinão o Judeo, "Sinan the Jew", was a Barbary corsair who sailed under the famed Ottoman admir ...

defeated its combined fleet, commanded by Andrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; lij, Drîa Döia ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was a Genoese statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

As the ruler of Genoa, Doria reformed the Re ...

, at the Battle of Preveza in September 1538. This victory secured Ottoman dominance over the Mediterranean for the next 33 years, until the Battle of Lepanto

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states (comprising Spain and its Italian territories, several independent Italian states, and the Soverei ...

in 1571.

In the summer of 1539, Barbarossa captured the islands of Skiathos

Skiathos ( el, Σκιάθος, , ; grc, Σκίαθος, ; and ) is a small Greek island in the northwest Aegean Sea. Skiathos is the westernmost island in the Northern Sporades group, east of the Pelion peninsula in Magnesia on the mainland ...

, Skyros

Skyros ( el, Σκύρος, ), in some historical contexts Latinized Scyros ( grc, Σκῦρος, ), is an island in Greece, the southernmost of the Sporades, an archipelago in the Aegean Sea. Around the 2nd millennium BC and slightly later, the ...

, Andros

Andros ( el, Άνδρος, ) is the northernmost island of the Greek Cyclades archipelago, about southeast of Euboea, and about north of Tinos. It is nearly long, and its greatest breadth is . It is for the most part mountainous, with many ...

and Serifos

Serifos ( el, Σέριφος, la, Seriphus, also Seriphos; Seriphos: Eth. Seriphios: Serpho) is a Greek island municipality in the Aegean Sea, located in the western Cyclades, south of Kythnos and northwest of Sifnos. It is part of the Milos ...

and recaptured Castelnuovo from the Spanish, who had taken it from the Ottomans after the battle of Preveza. He also captured the nearby Castle of Risan

Risan ( Montenegrin: Рисан, ) is a town in the Bay of Kotor, Montenegro. It traces its origins to the ancient settlement of Rhizon, the oldest settlement in the Bay of Kotor.

Lying in the innermost portion of the bay, the settlement was pro ...

, and with Sinan Reis, later assaulted the Venetian fortress of Cattaro

Kotor (Montenegrin Cyrillic: Котор, ), historically known as Cattaro (from Italian: ), is a coastal town in Montenegro. It is located in a secluded part of the Bay of Kotor. The city has a population of 13,510 and is the administrative ...

and the Spanish fortress of Santa Veneranda near Pesaro. Barbarossa later took the remaining Christian outposts in the Ionian and Aegean Seas. Venice finally signed a peace treaty with Sultan Suleiman in October 1540, agreeing to recognize the Ottoman territorial gains and to pay 300,000 gold ducats.

In 1540 Barbarossa led a crew of 2,000 men and captured and ransacked the town of

In 1540 Barbarossa led a crew of 2,000 men and captured and ransacked the town of Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

.Hernandez, Andrea"The Jewish impact on the social and economic manifestation of the Gibraltarian identity."

(2011). He left Gibraltar after taking 75 prisoners which removed a significant percent of Gibraltar’s population, he ultimately eliminated the town of almost an entire generation of Gibraltarians. In September 1540, Emperor Charles V contacted Barbarossa and offered him to become his Admiral-in-Chief as well as the ruler of Spain's territories in North Africa, but he refused. Unable to persuade Barbarossa to switch sides, in October 1541, Charles himself laid siege to Algiers, seeking to end the corsair threat to the Spanish domains and Christian shipping in the western Mediterranean. The season was not ideal for such a campaign, and both Andrea Doria, who commanded the fleet, and Hernán Cortés, who had been asked by Charles to participate in the campaign, attempted to change the Emperor's mind but failed. Eventually, a violent storm disrupted Charles's landing operations. Andrea Doria took his fleet away into open waters to avoid being wrecked on the shore, but much of the Spanish fleet went aground. After some indecisive fighting on land, Charles had to abandon the effort and withdraw his severely battered force.

Franco-Ottoman alliance

In 1543, Barbarossa headed towards Marseilles to assist France, then an ally of the Ottoman Empire, and cruised the western Mediterranean with a fleet of 210 ships (70 galleys, 40 galliots and 100 other warships carrying 14,000 Turkish soldiers, thus an overall total of 30,000 Ottoman troops). On his way, while passing through the

In 1543, Barbarossa headed towards Marseilles to assist France, then an ally of the Ottoman Empire, and cruised the western Mediterranean with a fleet of 210 ships (70 galleys, 40 galliots and 100 other warships carrying 14,000 Turkish soldiers, thus an overall total of 30,000 Ottoman troops). On his way, while passing through the Strait of Messina

The Strait of Messina ( it, Stretto di Messina, Sicilian: Strittu di Missina) is a narrow strait between the eastern tip of Sicily ( Punta del Faro) and the western tip of Calabria ( Punta Pezzo) in Southern Italy. It connects the Tyrrhenian S ...

, he asked Diego Gaetani, governor of Reggio Calabria, to surrender his city. Gaetani responded with cannon fire, which killed three Turkish sailors.

Barbarossa, angered by the response, besieged and captured the city. He then landed on the coasts of Campania

(man), it, Campana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demog ...

and Lazio

it, Laziale

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

and, from the mouth of the Tiber

The Tiber ( ; it, Tevere ; la, Tiberis) is the third-longest List of rivers of Italy, river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where ...

, threatened Rome, but France intervened in favor of the pope's city. Barbarossa then raided several Italian and Spanish islands and coastal settlements before laying the Siege of Nice and capturing the city on 5 August 1543 on behalf of the French king, Francis I.

The Ottoman captain later landed at Antibes and the Île Sainte-Marguerite

The Île Sainte-Marguerite () is the largest of the Lérins Islands, about half a mile off shore from the French Riviera town of Cannes. The island is approximately in length (east to west) and across.

The island is most famous for its fortr ...

near Cannes

Cannes ( , , ; oc, Canas) is a city located on the French Riviera. It is a commune located in the Alpes-Maritimes department, and host city of the annual Cannes Film Festival, Midem, and Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity. T ...

before sacking the city of San Remo, other ports of Liguria, Monaco and La Turbie

La Turbie (; oc, A Torbia; in Italian "Turbia" from ''tropea'', Latin for trophy) is a commune in the Alpes-Maritimes department in southeastern France.

History

La Turbie was famous in Roman times for the large monument, the Trophy of Augus ...

. King Francis ordered the evacuation of Toulon and placed the city in the hands of Barbarossa, for the next six months Toulon was converted to a Turkish city which included its own mosque and slave market.

In the spring of 1544, after assaulting San Remo for the second time and landing at Borghetto Santo Spirito and

In the spring of 1544, after assaulting San Remo for the second time and landing at Borghetto Santo Spirito and Ceriale

Ceriale ( lij, O Çejâ, locally ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Savona in the Italian region of Liguria, located about southwest of Genoa and about southwest of Savona.

Ceriale borders the following municipalities: Albenga ...

, Barbarossa defeated another Spanish-Italian fleet and raided deeply into the Kingdom of Naples. He then sailed to Genoa with his 210 ships and threatened to attack the city unless it freed Turgut Reis

Dragut ( tr, Turgut Reis) (1485 – 23 June 1565), known as "The Drawn Sword of Islam", was a Muslim Ottoman naval commander, governor, and noble, of Turkish or Greek descent. Under his command, the Ottoman Empire's maritime power was extend ...

, who had been serving as a galley slave on a Genoese ship and then was imprisoned in the city since his capture in Corsica by Giannettino Doria in 1540. Barbarossa was invited by Andrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; lij, Drîa Döia ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was a Genoese statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

As the ruler of Genoa, Doria reformed the Re ...

to discuss the issue at his palace in Fassolo. The two admirals negotiated the release of Turgut Reis in exchange for 3,500 gold ducats.

Barbarossa then successfully repulsed further Spanish attacks on southern France, but was recalled to Istanbul after Charles V and Suleiman had agreed to a truce in 1544.

After leaving Provence from the port of Île Sainte-Marguerite in May 1544, Barbarossa assaulted San Remo for the third time, and when he appeared before Vado Ligure

Vado Ligure ( lij, Voæ), in antiquity Vada Sabatia, is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Savona, Liguria, in northern Italy.

Economy

Vado has a large industrial and commercial port.

Vado Ligure is home to a railway construction plant, ...

, the Republic of Genoa sent him a substantial sum to save other Genoese cities from further attacks. In June 1544, Barbarossa appeared before Elba. Threatening to bombard Piombino

Piombino is an Italian town and ''comune'' of about 35,000 inhabitants in the province of Livorno (Tuscany). It lies on the border between the Ligurian Sea and the Tyrrhenian Sea, in front of Elba Island and at the northern side of Maremma.

Ove ...

unless the city's Lord released the son of Sinan Reis

Sinan Reis, also ''Ciphut Sinan'', ( he, סנאן ראיס, ''Sinan Rais''; ar, سنان ريس, ''Sinan Rayyis'';) "Sinan the Chief", and pt, Sinão o Judeo, "Sinan the Jew", was a Barbary corsair who sailed under the famed Ottoman admir ...

who had been captured and baptized 10 years earlier by the Spaniards in Tunis, he obtained his release. He then captured Castiglione della Pescaia

Castiglione della Pescaia (), regionally simply abbreviated as Castiglione, is an ancient seaside town in the province of Grosseto, in Tuscany, central Italy. The modern city grew around a medieval 12th century fortress ( it, castello) and a large ...

, Talamone

Talamone is a town in Tuscany, on the west coast of central Italy, administratively a frazione of the comune of Orbetello, province of Grosseto, in the Tuscan Maremma.

Talamone is easily reached from Via Aurelia, and is about from Grosseto and ...

and Orbetello

Orbetello is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Grosseto (Tuscany), Italy. It is located about south of Grosseto, on the eponymous lagoon, which is home to an important Natural Reserve.

History

Orbetello was an ancient Etruscan settleme ...

in the province of Grosseto

Grosseto () is a city and ''comune'' in the central Italian region of Tuscany, the capital of the Province of Grosseto. The city lies from the Tyrrhenian Sea, in the Maremma, at the centre of an alluvial plain on the Ombrone river.

It is the ...

in Tuscany. There, he destroyed the tomb and burned the remains of Bartolomeo Peretti, who had burned his father's house in Mytilene

Mytilene (; el, Μυτιλήνη, Mytilíni ; tr, Midilli) is the capital of the Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University o ...

the previous year, in 1543.

He then captured Montiano

Montiano ( rgn, Muncin) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Forlì-Cesena in the Italian region Emilia-Romagna, located about southeast of Bologna and about southeast of Forlì. As of 31 December 2004, it had a population of 1,573 ...

and occupied Porto Ercole

Porto Ercole () is an Italian town located in the municipality of Monte Argentario, in the Province of Grosseto, Tuscany. It is one of the two major towns that form the township, along with Porto Santo Stefano. Its name means "Port Hercules".

Ge ...

and the Isle of Giglio. He later assaulted Civitavecchia

Civitavecchia (; meaning "ancient town") is a city and ''comune'' of the Metropolitan City of Rome in the central Italian region of Lazio. A sea port on the Tyrrhenian Sea, it is located west-north-west of Rome. The harbour is formed by two pier ...

, but Leone Strozzi

Leone Strozzi (15 October 1515 – 28 June 1554) was an Italian condottiero belonging to the famous Strozzi family of Florence.

Biography

He was the son of Filippo Strozzi the Younger and Clarice de' Medici, and brother to Piero, Roberto and Lor ...

, the French envoy, convinced Barbarossa to lift the siege.

The Ottoman fleet then assaulted the coasts of Sardinia before appearing at Ischia

Ischia ( , , ) is a volcanic island in the Tyrrhenian Sea. It lies at the northern end of the Gulf of Naples, about from Naples. It is the largest of the Phlegrean Islands. Roughly trapezoidal in shape, it measures approximately east to west ...

and landing there in July 1544, capturing the city as well as Forio

Forio (known also as ''Forio of Ischia'') is a town and '' comune'' of c. 17,000 inhabitants in the Metropolitan City of Naples, southern Italy, situated on the island of Ischia.

Overview

Its territory includes the town of Panza, the only ''fraz ...

and the Isle of Procida

Procida (; nap, Proceta ) is one of the Flegrean Islands off the coast of Naples in southern Italy. The island is between Cape Miseno and the island of Ischia. With its tiny satellite island of Vivara, it is a ''comune'' of the Metropolitan Ci ...

before threatening Pozzuoli

Pozzuoli (; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' of the Metropolitan City of Naples, in the Italian region of Campania. It is the main city of the Phlegrean Peninsula.

History

Pozzuoli began as the Greek colony of ''Dicaearchia'' ( el, Δικα ...

. Encountering 30 galleys under Giannettino Doria, Barbarossa forced them to sail away towards Sicily and seek refuge in Messina. Due to strong winds, the Ottomans were unable to attack Salerno but managed to land at Cape Palinuro

Cape Palinuro ( Italian : ''Capo Palinuro'') is located in southwestern Italy, approximately 50 miles (80 km) southeast of Salerno, in southern part of Cilento region. It is supposedly named after Palinurus, the helmsman of Aeneas' ship in V ...

nearby. Barbarossa then entered the Strait of Messina and landed at Catona, Fiumara

Fiumara ( Reggino: ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Reggio Calabria in the Italian region Calabria, located about southwest of Catanzaro and about northeast of Reggio Calabria.

Fiumara borders the following municip ...

and Calanna (near Reggio Calabria) and later at Cariati

Cariati () is a town and '' comune'' in the province of Cosenza in the Calabria region of southern Italy. Cariati is divided into two parts: Cariati Superiore, situated on top of a hill, and Cariati Marina, which is stretched along the Ionian c ...

and at Lipari

Lipari (; scn, Lìpari) is the largest of the Aeolian Islands in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the northern coast of Sicily, southern Italy; it is also the name of the island's main town and ''comune'', which is administratively part of the Metropo ...