Background of the Spanish Civil War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The background of the Spanish Civil War dates back to the end of the 19th century, when the owners of large estates, called '' latifundios'', held most of the power in a land-based oligarchy. The landowners' power was unsuccessfully challenged by the industrial and merchant sectors. In 1868 popular uprisings led to the overthrow of Queen

In 1868, popular uprisings led to the overthrow of Queen

In 1868, popular uprisings led to the overthrow of Queen

In 1897, an Italian anarchist assassinated Prime Minister

In 1897, an Italian anarchist assassinated Prime Minister  Increasing exports during the

Increasing exports during the

/ref> Lerroux resigned in April 1934, after President Zamora hesitated to sign an Amnesty Bill which let off the arrested members of the 1932 plot. He was replaced by Ricardo Samper. The Socialist Party ruptured over the question of whether or not to move towards

Isabella II

Isabella II ( es, Isabel II; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904), was Queen of Spain from 29 September 1833 until 30 September 1868.

Shortly before her birth, the King Ferdinand VII of Spain issued a Pragmatic Sanction to ensure the successi ...

of the House of Bourbon. In 1873 Isabella's replacement, King Amadeo I

Amadeo ( it, Amedeo , sometimes latinized as Amadeus; full name: ''Amedeo Ferdinando Maria di Savoia''; 30 May 184518 January 1890) was an Italian prince who reigned as King of Spain from 1870 to 1873. The first and only King of Spain to come fro ...

of the House of Savoy, abdicated due to increasing political pressure, and the short-lived First Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic ( es, República Española), historiographically referred to as the First Spanish Republic, was the political regime that existed in Spain from 11 February 1873 to 29 December 1874.

The Republic's founding ensued after th ...

was proclaimed. After the restoration of the Bourbons in December 1874, Carlists and anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

emerged in opposition to the monarchy. Alejandro Lerroux

Alejandro Lerroux García (4 March 1864, in La Rambla, Córdoba – 25 June 1949, in Madrid) was a Spanish politician who was the leader of the Radical Republican Party. He served as Prime Minister three times from 1933 to 1935 and held severa ...

helped bring republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

to the fore in Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the nort ...

, where poverty was particularly acute. Growing resentment of conscription and of the military culminated in the Tragic Week in Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

in 1909. After the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the working class, the industrial class, and the military united in hopes of removing the corrupt central government, but were unsuccessful. Fears of communism grew. A military coup brought Miguel Primo de Rivera

Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja, 2nd Marquess of Estella (8 January 1870 – 16 March 1930), was a dictator, aristocrat, and military officer who served as Prime Minister of Spain from 1923 to 1930 during Spain's Restoration era. He deepl ...

to power in 1923, and he ran Spain as a military dictatorship. Support for his regime gradually faded, and he resigned in January 1930. There was little support for the monarchy in the major cities, and King Alfonso XIII abdicated; the Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 ...

was formed, whose power would remain until the culmination of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

. Monarchists would continue to oppose the Republic.

The revolutionary committee headed by Niceto Alcalá-Zamora

Niceto Alcalá-Zamora y Torres (6 July 1877 – 18 February 1949) was a Spanish lawyer and politician who served, briefly, as the first prime minister of the Second Spanish Republic, and then—from 1931 to 1936—as its president.

Early life

...

became the provisional government, with Zamora as the President and Head of State.Beevor (2006). p. 23. The Republic had broad support from all segments of society; elections in June 1931 returned a large majority of Republicans and Socialists. With the onset of the Great Depression, the government attempted to assist rural Spain by instituting an eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the ...

and giving tenure to farm workers. Land reform and working conditions remained important issues throughout the lifetime of the Republic. Fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

remained a reactive threat, helped by controversial reforms to the military. In December a new reformist, liberal, and democratic constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

was declared. The constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

secularised the government, and this, coupled with their slowness to respond to a wave of anti-clerical violence prompted committed Catholics to become disillusioned with the incumbent coalition government. In October 1931 Manuel Azaña

Manuel Azaña Díaz (; 10 January 1880 – 3 November 1940) was a Spanish politician who served as Prime Minister of the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1933 and 1936), organizer of the Popular Front in 1935 and the last President of the Repu ...

became Prime Minister of a minority government. The Right won the elections of 1933 following an unsuccessful uprising by General José Sanjurjo

José Sanjurjo y Sacanell (; 28 March 1872 – 20 July 1936), was a Spanish general, one of the military leaders who plotted the July 1936 ''coup d'état'' which started the Spanish Civil War.

He was endowed the nobiliary title of "Marquis o ...

in August 1932, who would later lead the coup that started the civil war.

Events in the period following November 1933, called the "black biennium", seemed to make a civil war more likely. Alejandro Lerroux

Alejandro Lerroux García (4 March 1864, in La Rambla, Córdoba – 25 June 1949, in Madrid) was a Spanish politician who was the leader of the Radical Republican Party. He served as Prime Minister three times from 1933 to 1935 and held severa ...

of the Radical Republican Party

The Radical Republican Party ( es, Partido Republicano Radical), sometimes shortened to the Radical Party, was a Spanish Radical party in existence between 1908 and 1936. Beginning as a splinter from earlier Radical parties, it initially played a ...

(RRP) formed a government with the support of CEDA

The Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas (, CEDA), was a Spanish political party in the Second Spanish Republic. A Catholic conservative force, it was the political heir to Ángel Herrera Oria's Acción Popular and defined itself in te ...

and rolled back all major changes made under the previous administration, he also granted amnesty to General José Sanjurjo

José Sanjurjo y Sacanell (; 28 March 1872 – 20 July 1936), was a Spanish general, one of the military leaders who plotted the July 1936 ''coup d'état'' which started the Spanish Civil War.

He was endowed the nobiliary title of "Marquis o ...

, who had attempted an unsuccessful coup in 1932. Some monarchists moved to the Fascist Falange Española

Falange Española (FE; English: Spanish Phalanx) was a Spanish fascist political organization active from 1933 to 1934.

History

The Falange Española was created on 29 October 1933 as the successor of the Movimiento Español Sindicalista (ME ...

to help achieve their aims. In response, the socialist party (PSOE

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español ; PSOE ) is a social-democraticThe PSOE is described as a social-democratic party by numerous sources:

*

*

*

* political party in Spain. The PSOE has been in gov ...

) became more extreme, setting up a revolutionary committee and training the socialist youth in secret. Open violence occurred in the streets of Spanish cities and militancy continued to increase right up until the start of the civil war, reflecting a movement towards radical upheaval rather than peaceful democratic means as a solution to Spain's problems. In the last months of 1934, two government collapses brought members of the Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right

The Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas (, CEDA), was a Spanish political party in the Second Spanish Republic. A Catholic conservative force, it was the political heir to Ángel Herrera Oria's Acción Popular and defined itself in te ...

(CEDA) into the government, making it more right-wing. Farm workers' wages were halved, and the military was purged of republican members and reformed. A Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

alliance was organised, which won the 1936 elections. Azaña led a weak minority government, but soon replaced Zamora as president in April. Prime Minister Casares failed to heed warnings of a military conspiracy involving several generals, who decided that the government had to be replaced if the dissolution of Spain was to be prevented. They organised a military coup in July, which started the Spanish Civil War.

Constitutional monarchy

19th century

The 19th century was a turbulent time for Spain.Beevor (2006). p. 8. Those in favour of reforming the Spanish government vied for political power withconservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

who intended to prevent such reforms from being implemented. In a tradition that started with the Spanish Constitution of 1812

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy ( es, link=no, Constitución Política de la Monarquía Española), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz ( es, link=no, Constitución de Cádiz) and as ''La Pepa'', was the first Constitut ...

, many liberals sought to curtail the authority of the Spanish monarchy

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

as well as to establish a nation-state under their ideology and philosophy.Fraser (1979). pp. 38–39. The reforms of 1812 were short-lived as they were almost immediately overturned by King Ferdinand VII

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Charles IV of Spain

, mother = Maria Luisa of Parma

, birth_date = 14 October 1784

, birth_place = El Escorial, Spain

, death_date =

, death_place = Madrid, Spain

, burial_plac ...

when he dissolved the aforementioned constitution. This ended the Trienio Liberal government. Twelve successful coups were eventually carried out in the sixty-year period between 1814 and 1874. There were several attempts to realign the political system to match social reality. Until the 1850s, the economy of Spain was primarily based on agriculture. There was little development of a bourgeois industrial or commercial class. The land-based oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, r ...

remained powerful; a small number of people held large estates (called ''latifundia

A ''latifundium'' (Latin: ''latus'', "spacious" and ''fundus'', "farm, estate") is a very extensive parcel of privately owned land. The latifundia of Roman history were great landed estates specializing in agriculture destined for export: grain, o ...

'') as well as all of the important government positions. The landowners' power was challenged by the industrial and merchant sectors, largely unsuccessfully. In addition to these regime changes and hierarchies, there was a series of civil wars that transpired in Spain known as the Carlist Wars throughout the middle of the century. There were three such wars: the First Carlist War

The First Carlist War was a civil war in Spain from 1833 to 1840, the first of three Carlist Wars. It was fought between two factions over the succession to the throne and the nature of the Spanish monarchy: the conservative and devolutionist ...

(1833-1840), the Second Carlist War

The Second Carlist War, or the War of the Matiners (Catalan for "early-risers," so-called from the harassing action that took place at the earliest hours of the morning), was a civil war occurring in Spain. Some historians consider it a direct ...

(1846-1849), and the Third Carlist War

The Third Carlist War ( es, Tercera Guerra Carlista) (1872–1876) was the last Carlist War in Spain. It is sometimes referred to as the "Second Carlist War", as the earlier "Second" War (1847–1849) was smaller in scale and relatively trivial ...

(1872-1876). During these wars, a right-wing political movement known as Carlism fought to institute a monarchial dynasty under a different branch of the House of Bourbon that was predicated and descended upon Don Infante Carlos María Isidro of Molina.

In 1868, popular uprisings led to the overthrow of Queen

In 1868, popular uprisings led to the overthrow of Queen Isabella II

Isabella II ( es, Isabel II; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904), was Queen of Spain from 29 September 1833 until 30 September 1868.

Shortly before her birth, the King Ferdinand VII of Spain issued a Pragmatic Sanction to ensure the successi ...

of the House of Bourbon. Two distinct factors led to the uprisings: a series of urban riots, and a liberal movement within the middle classes and the military (led by General Joan Prim

Juan Prim y Prats, 1st Count of Reus, 1st Marquis of los Castillejos, 1st Viscount of Bruch (; ca, Joan Prim i Prats ; 6 December 1814 – 30 December 1870) was a Spanish general and statesman who was briefly Prime Minister of Spain until ...

),Thomas (1961). p. 13. who were concerned about the ultra-conservatism of the monarchy.Preston (2006). p. 21. In 1873 Isabella's replacement, King Amadeo I

Amadeo ( it, Amedeo , sometimes latinized as Amadeus; full name: ''Amedeo Ferdinando Maria di Savoia''; 30 May 184518 January 1890) was an Italian prince who reigned as King of Spain from 1870 to 1873. The first and only King of Spain to come fro ...

of the House of Savoy, abdicated

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

due to increasing political pressure, and the First Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic ( es, República Española), historiographically referred to as the First Spanish Republic, was the political regime that existed in Spain from 11 February 1873 to 29 December 1874.

The Republic's founding ensued after th ...

was proclaimed. However, the intellectuals behind the Republic were powerless to prevent a descent into chaos. Uprisings were crushed by the military. The old monarchy returned with the restoration of the Bourbons in December 1874,Preston (2006). p. 22. as reform was deemed less important than peace and stability. Despite the introduction of universal male suffrage

Universal manhood suffrage is a form of voting rights in which all adult male citizens within a political system are allowed to vote, regardless of income, property, religion, race, or any other qualification. It is sometimes summarized by the slo ...

in 1890, elections were controlled by local political bosses (''caciques

A ''cacique'' (Latin American ; ; feminine form: ''cacica'') was a tribal chieftain of the Taíno people, the indigenous inhabitants at European contact of the Bahamas, the Greater Antilles, and the northern Lesser Antilles. The term is a Spa ...

'').

The most traditionalist sectors of the political sphere systematically tried to prevent liberal reforms and to sustain the patrilineal

Patrilineality, also known as the male line, the spear side or agnatic kinship, is a common kinship system in which an individual's family membership derives from and is recorded through their father's lineage. It generally involves the inheritan ...

monarchy. The Carlists – supporters of Infante Carlos and his descendants – fought to promote Spanish tradition and Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

against the liberalism of successive Spanish governments. The Carlists attempted to restore the historic liberties and broad regional autonomy granted to the Basque Country and Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the nort ...

by their ''fuero

(), (), () or () is a Spanish legal term and concept. The word comes from Latin , an open space used as a market, tribunal and meeting place. The same Latin root is the origin of the French terms and , and the Portuguese terms and ; all ...

s'' (regional charters). At times they allied with nationalists (separate from the National Faction during the civil war itself), including during the Carlist Wars.

Periodically, anarchism became popular among the working class, and was far stronger in Spain than anywhere else in Europe at the time. Anarchists were easily defeated in clashes with government forces.Preston (2006). p. 24.

20th century

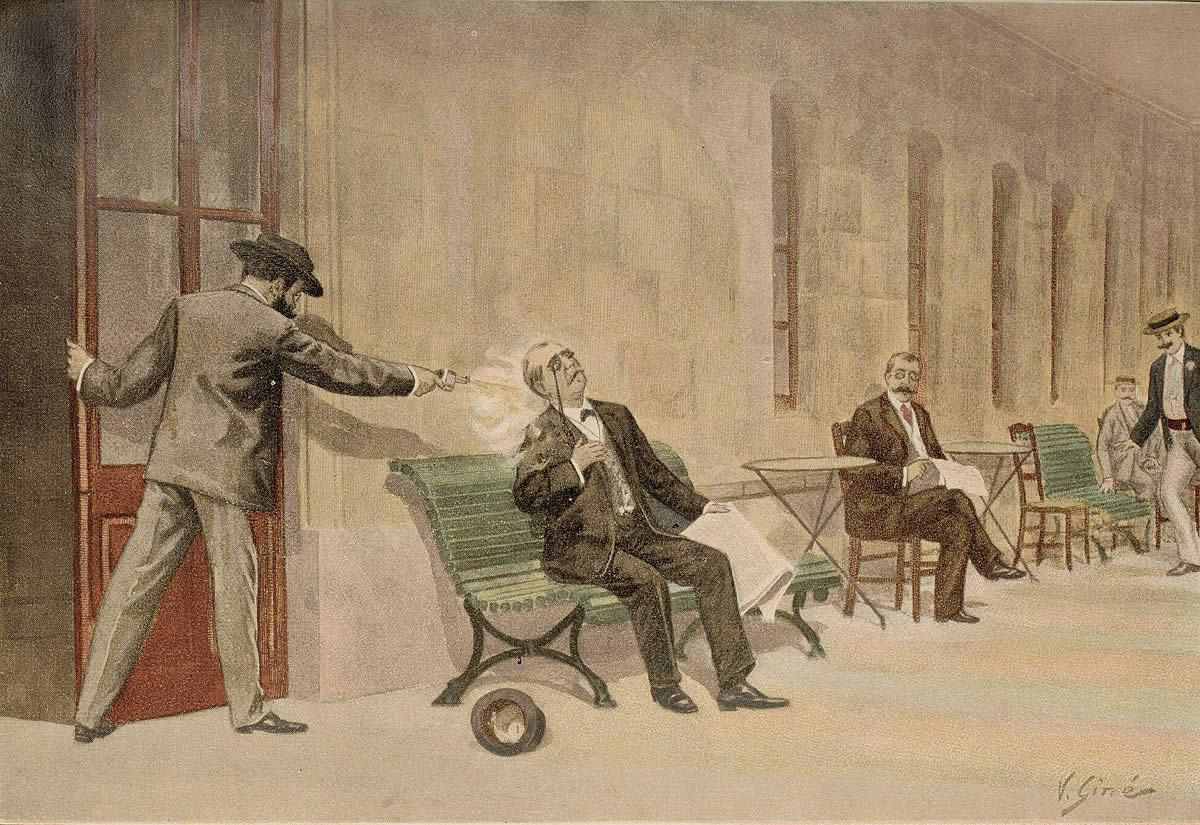

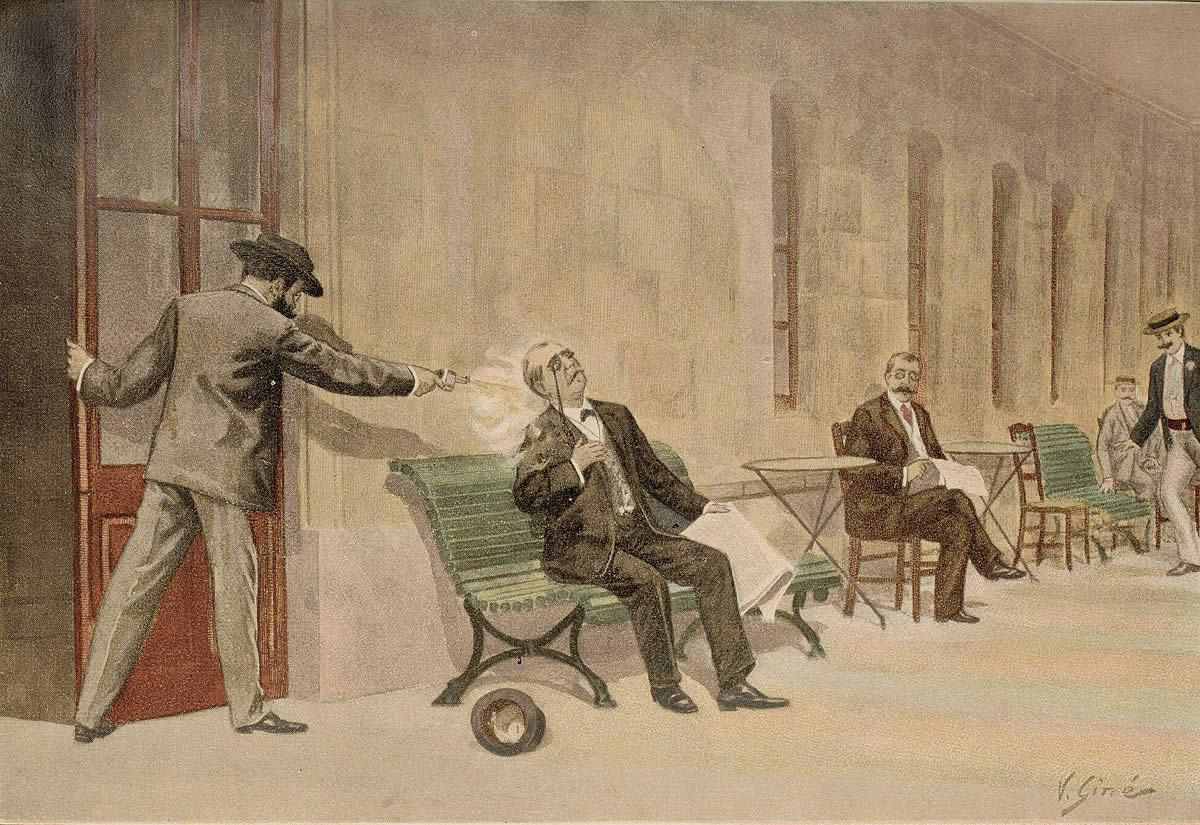

In 1897, an Italian anarchist assassinated Prime Minister

In 1897, an Italian anarchist assassinated Prime Minister Antonio Cánovas del Castillo

Antonio Cánovas del Castillo (8 February 18288 August 1897) was a Spanish politician and historian known principally for serving six terms as Prime Minister and his overarching role as "architect" of the regime that ensued with the 1874 restor ...

, motivated by a growing number of arrests and the use of torture by the government. The loss of Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, Spain's last valuable colony, in the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

of 1898 hit exports from Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the nort ...

hardest; there were acts of terrorism and actions by ''agents provocateurs

An agent provocateur () is a person who commits, or who acts to entice another person to commit, an illegal or rash act or falsely implicate them in partaking in an illegal act, so as to ruin the reputation of, or entice legal action against, the ...

'' in Barcelona. In the first two decades of the 20th century, the industrial working class grew in number. There was a growing discontent in the Basque country and Catalonia, where much of Spain's industry was based. They believed that the government favoured agrarianism and therefore failed to represent their interests.Preston (2006). p. 25. The average illiteracy rate was 64%, with considerable regional variation. Poverty in some areas was great and mass emigration to the New World occurred in the first decade of the century.

Spain's socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

party, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español ; PSOE ) is a social-democraticThe PSOE is described as a social-democratic party by numerous sources:

*

*

*

* political party in Spain. The PSOE has been in gove ...

( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español, PSOE) and its associated trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ...

, the ''Unión General de Trabajadores

The Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT, General Union of Workers) is a major Spanish trade union, historically affiliated with the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE).

History

The UGT was founded 12 August 1888 by Pablo Iglesias Posse ...

'' (UGT), gained support. The UGT grew from 8,000 members in 1908 to 200,000 in 1920. Branch offices ('' Casas del pueblo'') of the unions were established in major cities. The UGT was constantly fearful of losing ground to the anarchists. It was respected for its discipline during strikes. However, it was centrist

Centrism is a political outlook or position involving acceptance or support of a balance of social equality and a degree of social hierarchy while opposing political changes that would result in a significant shift of society strongly to Left-w ...

and anti-Catalan, with only 10,000 members in Barcelona as late as 1936. The PSOE and the UGT were based on a simple form of Marxism

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectical ...

, one that assumed an inevitable revolution, and were isolationist

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entan ...

in character. When the UGT moved their headquarters from Barcelona to Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the Largest cities of the Europ ...

in 1899, many industrial workers in Catalonia were no longer able to access it. Some elements of the PSOE recognised the need for cooperation with republican parties.

In 1912 the Reformist Party was founded, which attracted intellectuals. Figures like its leader, Alejandro Lerroux

Alejandro Lerroux García (4 March 1864, in La Rambla, Córdoba – 25 June 1949, in Madrid) was a Spanish politician who was the leader of the Radical Republican Party. He served as Prime Minister three times from 1933 to 1935 and held severa ...

, helped attract wide support from the working class. His advocacy of anti-clericalism made him a successful demagogue

A demagogue (from Greek , a popular leader, a leader of a mob, from , people, populace, the commons + leading, leader) or rabble-rouser is a political leader in a democracy who gains popularity by arousing the common people against elites, ...

in Barcelona. He argued that the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

was inseparable from the system of oppression the people were under. It was around this time that republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

came to the fore.

The military was keen to avoid the break-up of the state and was increasingly inward-looking following the loss of Cuba. Regional nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

, perceived as separatism, was frowned upon. In 1905 the army attacked the headquarters of two satirical magazines in Catalonia believed to be undermining the government. To appease the military, the government outlawed negative comments about the military or Spain itself in the Spanish press. Resentment of the military and of conscription grew with the disastrous Rif War

The Rif War () was an armed conflict fought from 1921 to 1926 between Spain (joined by France in 1924) and the Berber tribes of the mountainous Rif region of northern Morocco.

Led by Abd el-Krim, the Riffians at first inflicted several de ...

of 1909 in Spanish Morocco.Beevor (2006). p. 13. Lerroux's support of the army's aims lost him support. Events culminated in the Tragic Week ( es, Semana Trágica) in Barcelona in 1909, when working class groups rioted against the call-up of reservists.Thomas (1961). p. 15. 48 churches and similar institutions were burned in anti-clerical attacks. The riot was finally ended by the military; 1,725 members of such groups were put on trial, with five people sentenced to death.Preston (2006). p. 29. These events led to the establishment of the National Confederation of Labour ( es, Confederación Nacional del Trabajo, CNT), an anarchist-controlled trade union committed to anarcho-syndicalism. It had over a million members by 1923.Thomas (1961). p. 16.

Increasing exports during the

Increasing exports during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

led to a boom in industry and declining living standards in the industrial areas, particularly Catalonia and the Basque country.Preston (2006). p. 30. There was high inflation. The industrial sector resented its subjugation by the agrarian central government. Along with concerns about antiquated promotion systems and political corruption, the war in Morocco had caused divisions in the military. Regenerationism

Regenerationism ( es, Regeneracionismo) was an intellectual and political movement in late 19th century and early 20th century Spain. It sought to make objective and scientific study of the causes of Spain's decline as a nation and to propose reme ...

became popular, and the working class, industrial class, and the military were united in their hope of removing the corrupt central government. However, these hopes were defeated in 1917 and 1918 when the various political parties representing these groups were either appeased or suppressed by the central government, one by one. The industrialists eventually backed the government as a way to restore order.Preston (2006). pp. 32–33. After the formation of the Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

in 1919, there was a growing fear of communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

within Spain and growing repression on the part of the government through military means. The PSOE split, with the more left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

members founding the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

in 1921.Preston (2006). pp. 34–35. The Restoration government failed to cope with an increasing number of strikes amongst the industrial workers in the north and the agricultural workers in the south.

Miguel Primo de Rivera

Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja, 2nd Marquess of Estella (8 January 1870 – 16 March 1930), was a dictator, aristocrat, and military officer who served as Prime Minister of Spain from 1923 to 1930 during Spain's Restoration era. He deepl ...

came to power in a military coup in 1923 and ran Spain as a military dictatorship. He handed monopolistic control of trade union power to the UGT, and introduced a sweeping programme of public works. These public works were extremely wasteful, including hydroelectric dams and highways causing the deficit to double between 1925 and 1929. Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

's financial situation was made far worse by the pegging of the peseta to the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the l ...

and by 1931 the peseta had lost nearly half its value.Beevor (2006). p. 20. The UGT was brought into the government to set up industrial arbitration boards, though this move was opposed by some in the group and was seen as opportunism by anarchist leaders. He also attempted to defend the agrarian–industrial monarchist coalition formed during the war. No significant reform to the political system (and in particular the monarchy) was instituted. This made forming a new government difficult, as existing problems had not been rectified. Gradually, his support faded because his personal approach to political life ensured he was personally held accountable for the government's failings, and due to an increasing frustration over his interference in economic matters he did not understand. José Calvo Sotelo

José Calvo Sotelo, 1st Duke of Calvo Sotelo, GE (6 May 1893 – 13 July 1936) was a Spanish jurist and politician, minister of Finance during the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera and a leading figure during the Second Republic. During t ...

, his finance minister, was one person to withdraw support, and de Rivera resigned in January 1930.Preston (2006). p. 36. There was little support for a return to the pre-1923 system, and the monarchy had lost credibility by backing the military government. Dámaso Berenguer

Dámaso Berenguer y Fusté, 1st Count of Xauen (4 August 1873 – 19 May 1953) was a Spanish general and politician. He served as Prime Minister during the last thirteen months of the reign of Alfonso XIII.

Biography

Berenguer was born in Sa ...

was ordered by the king to form a replacement government, but his dictablanda dictatorship failed to provide a viable alternative.Preston (2006). p. 37. The choice of Berenguer annoyed another important general, José Sanjurjo

José Sanjurjo y Sacanell (; 28 March 1872 – 20 July 1936), was a Spanish general, one of the military leaders who plotted the July 1936 ''coup d'état'' which started the Spanish Civil War.

He was endowed the nobiliary title of "Marquis o ...

, who believed himself to be a better choice. In the municipal elections of 12 April 1931, little support was shown for pro-monarchy parties in the major cities, and large numbers of people gathered in the streets of Madrid. King Alfonso XIII abdicated to prevent a "fratricidal civil war".His statement included the sentence "I am determined to have nothing to do with setting one of my countrymen against another in a fratricidal civil war." from Thomas (1961). pp. 18–19. The Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 ...

was formed.

Second Republic

The Second Republic was a source of hope to the poorest in Spanish society and a threat to the richest, but had broad support from all segments of society.Preston (2006). pp. 38–39.Niceto Alcalá-Zamora

Niceto Alcalá-Zamora y Torres (6 July 1877 – 18 February 1949) was a Spanish lawyer and politician who served, briefly, as the first prime minister of the Second Spanish Republic, and then—from 1931 to 1936—as its president.

Early life

...

was the first prime minister of the Republic. The wealthier landowners and the middle class accepted the Republic because of the lack of any suitable alternative. Elections to a constituent Cortes

Cortes, Cortés, Cortês, Corts, or Cortès may refer to:

People

* Cortes (surname), including a list of people with the name

** Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), a Spanish conquistador

Places

* Cortes, Navarre, a village in the South border of ...

in June 1931 returned a large majority of Republicans and Socialists, with the PSOE gaining 116 seats and Lerroux's Radical Party 94. Lerroux became foreign minister. The government was controlled by a Republican–Socialist coalition, whose members had differing objectives. Some more conservative members believed that the removal of the monarchy was enough by itself, but the Socialists and leftist Republicans demanded much wider reforms.

The state's financial position was poor. Supporters of the dictatorship attempted to block progress on reforming the economy.Preston (2006). pp. 41–42. The redistribution of wealth supported by the new government seemed a threat to the richest, in light of the recent Wall Street Crash

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange colla ...

and the onset of the Great Depression. The government attempted to tackle the dire poverty in rural areas by instituting an eight-hour day and giving the security of tenure to farm workers.Beevor (2006). p. 22. Landlords complained. The effectiveness of the reforms was dependent on the skill of the local governance, which was often badly lacking. Changes to the military were needed and education reform was another problem facing the Republic. The relationship between central government and the Basque and Catalan regions also needed to be decided.

Effective opposition was led by three groups. The first group included Catholic movements such as the Asociación Católica de Propagandistas,See also: :es:Asociación Católica de Propagandistas who had influence over the judiciary and the press.Preston (2006). p. 43. Rural landowners were told to think of the Republic as godless and communist.Preston (2006). p. 44. The second group consisted of organisations that had supported the monarchy, such as the Renovación Española

Spanish Renovation ( es, Renovación Española, RE) was a Spanish monarchist political party active during the Second Spanish Republic, advocating the restoration of Alfonso XIII of Spain as opposed to Carlism. Associated with the Acción Españo ...

and Carlists, who wished to see the new republic overthrown in a violent uprising. The third group were Fascist organisations, among them supporters of the dictator's son, José Antonio Primo de Rivera

José Antonio Primo de Rivera y Sáenz de Heredia, 1st Duke of Primo de Rivera, 3rd Marquess of Estella (24 April 1903 – 20 November 1936), often referred to simply as José Antonio, was a Spanish politician who founded the falangist Falang ...

. Primo de Rivera was the most significant leader of fascism in Spain. The press often editorialised about a foreign Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

–Masonic

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

–Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

plot. Members of the CNT willing to cooperate with the Republic were forced out, and it continued to oppose the government. The deeply unpopular Civil Guard ( es, Guardia Civil), founded in 1844, was charged with putting down revolts and was perceived as ruthless. Violence, including at Castilblanco

Castilblanco is a municipality located in the province of Badajoz, Extremadura, Spain. According to the 2005 census (INE), the municipality has a population of 1146 inhabitants.

Toponymy

There is no accord about the origins of the name of Casti ...

in December 1931, was usual.

On 11 May 1931 rumours that a taxi driver was supposedly killed by monarchists sparked a wave of anti-clerical violence throughout south west urban Spain beginning. An angry crowd assaulted and burned ABC newspaper. The government's reluctance to declare martial law in response and a comment attributed to Azaña that he would "rather all the churches in Spain be burnt than a single Republican harmed" prompted many Catholics to believe that the Republic was trying to prosecute Christianity. Next day the Jesuit Church in the Calle de La Flor was also burned. Several other churches and convents were burned throughout the day. Over the next days some hundred churches were burned all over Spain. The government blamed the monarchists for sparking the riots and closed the ABC newspaper and El Debate

''El Debate'' is a defunct Spanish Catholic daily newspaper, published in Madrid between 1910 and 1936. It was the most important Catholic newspaper of its time in Spain.

History and profile

''El Debate'' was founded in 1910 by Guillermo de Rivas ...

.Thomas (2013). Chapter 5

Parties in opposition to Alcalá-Zamora's provisional government gained the support of the church and the military.Preston (2006). pp. 46–47. The head of the church in Spain, Cardinal Pedro Segura, was particularly vocal in his disapproval. Until the 20th century, the Catholic Church had proved an essential part of Spain's character, although it had internal problems. Segura was expelled from Spain in June 1931. This prompted an outcry from the Catholic right, who cited oppression. The military were opposed to reorganisation, including an increase in regional autonomy granted by the central government, and reforms to improve efficiency were seen as a direct attack. Officers were retired and a thousand had their promotions reviewed, including Francisco Franco, who served as director of the General Military Academy in Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributari ...

, which was closed by Manuel Azaña.

Constitution of 1931

In October 1931 The conservative Catholic Republican prime-minister Alcalá-Zamora and the Interior MinisterMiguel Maura

Miguel Maura (1887–1971) was a Spanish politician who served as the minister of interior in 1931 being the first Spanish politician to hold the post in the Second Spanish Republic. He was the founder of the Conservative Republican Party.

Early ...

resigned from the provisional government when the controversial articles 26 and 27 of the constitution, which strictly controlled Church property and prohibited religious orders from engaging in education were passed. During the debate held on 13 October, a night that Alcalá-Zamora considered the saddest night of his life, Azaña declared that Spain had "ceased to be Catholic"; although to an extent his statement was accurate,According to Thomas (1961). p. 31., it was estimated that around two-thirds of Spaniards were not practising Catholics. it was a politically unwise thing to say. Manuel Azaña became the new provisional Prime Minister. Desiring the job for himself, Lerroux became alienated, and his Radical Party switched to the opposition,Thomas (1961). p. 47. leaving Azaña dependent on the Socialists for support. The Socialists, who favoured reform, objected to the lack of progress. The reforms that were made alienated the land-holding right.Preston (2006). pp. 54–55. Conditions for labourers remained dreadful; the reforms had not been enforced.Preston (2006). p. 57. Rural landowners declared war on the government by refusing to plant crops.Preston (2006). p. 58. Meanwhile, several agricultural strikes were harshly put down by the authorities. Reforms, including the unsuccessful attempt to break up large holdings, failed to significantly improve the situation for rural workers. By the end of 1931, King Alfonso, in exile, stopped attempting to prevent an armed insurrection of monarchists in Spain, and was tried and condemned to life imprisonment ''in absentia''.

A new constitution was approved on 9 December 1931.Preston (2006). p. 53. The first draft, prepared by Ángel Ossorio y Gallardo and others, was rejected, and a much more daring text creating a "democratic republic of workers of every class" was promulgated. It contained much in the way of emotive language and included many controversial articles, some of which were aimed at curbing the Catholic Church.Thomas (1961). p. 46.Beevor (2006). p. 24. The constitution was reformist, liberal, and democratic in nature, and was welcomed by the Republican–Socialist coalition. It appalled landowners, industrialists, the organised church, and army officers. At this point once the constituent assembly had fulfilled its mandate of approving a new constitution, it should have arranged for regular parliamentary elections and adjourned.Hayes (1951). p. 91. However fearing the increasing popular opposition the Radical and Socialist majority postponed the regular elections, therefore prolonging their way in power for two more years. This way the provisional republican government of Manuel Azaña initiated numerous reforms to what in their view would "modernize" the country.Hayes (1951). p. 91.

As the provisional government believed it was necessary to break the control the church had over Spanish affairs, the new constitution removed any special rights held by the Catholic Church. The constitution proclaimed religious freedom and a complete separation of Church and State

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular sta ...

. Catholic schools continued to operate, but outside the state system; in 1933 further legislation banned all monks and nuns from teaching. The Republic regulated church use of property and investments, provided for recovery and controls on the use of property the church had obtained during past dictatorships, and banned the Vatican-controlled Society of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

. The controversial articles 26 and 27 of the constitution strictly controlled Church property and prohibited religious orders from engaging in education. Supporters of the church and even Jose Ortega y Gasset

Jose is the English transliteration of the Hebrew and Aramaic name ''Yose'', which is etymologically linked to ''Yosef'' or Joseph. The name was popular during the Mishnaic and Talmudic periods.

*Jose ben Abin

*Jose ben Akabya

*Jose the Galilean ...

, a liberal advocate of the separation of church and state, considered the articles overreaching. Other articles legalising divorce and initiating agrarian reforms were equally controversial, and on 13 October 1931, Gil Robles, the leading spokesman of the parliamentary right, called for a Catholic Spain to make its stand against the Republic.Preston (2006). p. 54. Commentator Stanley Payne

Stanley George Payne (born September 9, 1934) is an American historian of modern Spain and European Fascism at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He retired from full-time teaching in 2004 and is currently Professor Emeritus at its Department ...

has argued that "the Republic as a democratic constitutional regime was doomed from the outset", because the far left considered any moderation of the anticlerical aspects of the constitution as totally unacceptable.Payne (1973). p. 632.

Restrictions on Christian iconography in schools and hospitals and the ringing of bells came into force in January 1932. State control of cemeteries was also imposed. Many ordinary Catholics began to see the government as an enemy because of the educational and religious reforms. Government actions were denounced as barbaric, unjust, and corrupt by the press.Preston (2006). p. 61.

In August 1932 there was an unsuccessful uprising by General José Sanjurjo

José Sanjurjo y Sacanell (; 28 March 1872 – 20 July 1936), was a Spanish general, one of the military leaders who plotted the July 1936 ''coup d'état'' which started the Spanish Civil War.

He was endowed the nobiliary title of "Marquis o ...

, who had been particularly appalled by events in Castilblanco.Thomas (1961). p. 62. The aims of the insurrection were vague, and it quickly turned into a fiasco.Thomas (1961). p. 63. Among the generals tried and sent to Spanish colonies were four men who would go on to distinguish themselves fighting against the Republic in the civil war: Francisco de Borbón y de la Torre

Francisco de Borbón y de la Torre ( es, Francisco de Paula de Borbón y La Torre; 16 January 1882 – 6 December 1952) was a Spanish aristocrat, military officer ( Captaincy General) and member of parliament in Spain. He was a cousin of King ...

, Duke of Seville

Duke of Seville ( es, Duque de Sevilla) is a title of Spanish nobility that was granted in 1823 by King Ferdinand VII of Spain to his nephew, Infante Enrique of Spain. The Dukes of Seville are members of the Spanish branch of the House of Bo ...

, Martin Alonso,See also: :es:Pablo Martín Alonso Ricardo Serrador Santés, and Heli Rolando de Tella y Cantos.

Azaña's government continued to ostracized the church. The Jesuits who were in charge of the best schools throughout the country were banned and had all their property confiscated. The army was reduced. Landowners were expropriated. Home rule was granted to Catalonia, with a local parliament and a president of its own.Hayes (1951). p. 91. In November 1932, Miguel de Unamuno

Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo (29 September 1864 – 31 December 1936) was a Spanish essayist, novelist, poet, playwright, philosopher, professor of Greek and Classics, and later rector at the University of Salamanca.

His major philosophical essa ...

, one of the most respected Spanish intellectuals, rector of the University of Salamanca, and himself a Republican, publicly raised his voice to protest. In a speech delivered on 27 November 1932, at the Madrid Ateneo, he protested: "Even the Inquisition was limited by certain legal guarantees. But now we have something worse: a police force which is grounded only on a general sense of panic and on the invention of non-existent dangers to cover up this over-stepping of the law."Hayes (1951) p. 93 In June 1933 Pope Pius XI issued the encyclical Dilectissima Nobis, "On Oppression of the Church of Spain", raising his voice against the persecution of the Catholic Church in Spain.

The political left became fractured, whilst the right united. The Socialist Party continued to support Azaña but headed further to the political left.Thomas (1961). p. 67. Gil Robles set up a new party, the Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right

The Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas (, CEDA), was a Spanish political party in the Second Spanish Republic. A Catholic conservative force, it was the political heir to Ángel Herrera Oria's Acción Popular and defined itself in te ...

( es, Confederatión Espanola de Derechas Autónomas, CEDA) to contest the 1933 election, and tacitly embraced Fascism. The right won an overwhelming victory, with the CEDA and the Radicals together winning 219 seats.Thomas (1961). p. 66. allocates 207 seats to the political right. They had spent far more on their election campaign than the Socialists, who campaigned alone. The roughly 3,000 members of the Communist Party were at this point not significant.

The "black biennium"

Following the elections of November 1933, Spain entered a period called the "black biennium" ( es, bienio negro) by the left. The CEDA had won a plurality of seats, but not enough to form a majority. PresidentNiceto Alcalá-Zamora

Niceto Alcalá-Zamora y Torres (6 July 1877 – 18 February 1949) was a Spanish lawyer and politician who served, briefly, as the first prime minister of the Second Spanish Republic, and then—from 1931 to 1936—as its president.

Early life

...

declined to invite the leader of the most voted party, Gil Robles, to form a government, and instead invited the Radical Republican Party

The Radical Republican Party ( es, Partido Republicano Radical), sometimes shortened to the Radical Party, was a Spanish Radical party in existence between 1908 and 1936. Beginning as a splinter from earlier Radical parties, it initially played a ...

's Alejandro Lerroux

Alejandro Lerroux García (4 March 1864, in La Rambla, Córdoba – 25 June 1949, in Madrid) was a Spanish politician who was the leader of the Radical Republican Party. He served as Prime Minister three times from 1933 to 1935 and held severa ...

to do so. Immediately after the election, the Socialists alleged electoral fraud; they had, according to the PSOE, needed twice as many votes as their opponents to win each seat. They identified the lack of unity in the left as another reason for their defeat. The Socialist opposition began to propagate a revolutionary ideal.Preston (2006). p. 67. Stanley Payne asserts that the left demanded the cancellation of the elections not because the elections were fraudulent but because in its view those that had won the elections did not share the republican ideals.Preston (2012). p. 84.

The government, with the backing of CEDA, set about removing price controls, selling state favours and monopolies, and removing the land reforms—to the landowners' considerable advantage. This created growing malnourishment in the south of Spain. The agrarian reforms, still in force, went tacitly unenforced.Thomas (1961). p. 75. Radicals became more aggressive and conservatives turned to paramilitary and vigilante actions.

The first working class protest came from the anarchists on 8 December 1933, and was easily crushed by force in most of Spain; Zaragoza held out for four days before the Spanish Republican Army

The Spanish Republican Army ( es, Ejército de la República Española) was the main branch of the Armed Forces of the Second Spanish Republic between 1931 and 1939.

It became known as People's Army of the Republic (''Ejército Popular de la Rep� ...

, employing tanks, stopped the uprising. The Socialists stepped up their revolutionary rhetoric, hoping to force Zamora to call new elections. Carlists and Alfonsist monarchist

The term Alfonsism refers to the movement in Spanish monarchism that supported the restoration of Alfonso XIII of Spain as King of Spain after the foundation of the Second Spanish Republic in 1931. The Alfonsists competed with the rival monarchis ...

s continued to prepare, with Carlists undergoing military drills in Navarre; they received the backing of Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini. Gil Robles struggled to control the CEDA's youth wing, which copied Germany and Italy's youth movements. Monarchists turned to the Fascist Falange Española

Falange Española (FE; English: Spanish Phalanx) was a Spanish fascist political organization active from 1933 to 1934.

History

The Falange Española was created on 29 October 1933 as the successor of the Movimiento Español Sindicalista (ME ...

, under the leadership of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, as a way to achieve their aims. Open violence occurred in the streets of Spanish cities. Official statistics state that 330 people were assassinated in addition to 213 failed attempts, and 1,511 people wounded in political violence. Those figures also indicate a total of 113 general strikes were called and 160 religious buildings were destroyed, typically by arson.abc.es: "La quema de iglesias durante la Segunda República" 10 May 2012/ref> Lerroux resigned in April 1934, after President Zamora hesitated to sign an Amnesty Bill which let off the arrested members of the 1932 plot. He was replaced by Ricardo Samper. The Socialist Party ruptured over the question of whether or not to move towards

Bolshevism

Bolshevism (from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, ...

. The youth wing, the Federation of Young Socialists ( es, Federación de Juventudes Socialistas), were particularly militant. The anarchists called a four-week strike in Zaragoza.Preston (2006). p. 72. Gil Robles' CEDA continued to mimic the German Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

, staging a rally in March 1934, to shouts of "Jefe" ("Chief", after the Italian "Duce" used in support of Mussolini). Gil Robles used an anti-strike law to successfully provoke and break up unions one at a time, and attempted to undermine the republican government of the Esquerra in Catalonia, who were attempting to continue the republic's reforms. Efforts to remove local councils from socialist control prompted a general strike, which was brutally put down by Interior Minister Salazar Alonso,See also: :es:Rafael Salazar Alonso with the arrest of four deputies and other significant breaches of articles 55 and 56 of the constitution. The Socialist Landworkers' Federation ( es, Federación Nacional da Trabajadores de la Tierra, FNTT), a trade union founded in 1930, was effectively prevented from operating until 1936.

On 26 September, the CEDA announced it would no longer support the RRP's minority government. It was replaced by an RRP cabinet, again led by Lerroux, that included three members of the CEDA. After a year of intense pressure, CEDA, who had more seats in parliament, was finally successful in forcing the acceptance of three ministries. As a reaction, the Socialists (PSOE) and Communists triggered an insurrection that they had been preparing for nine months. In Catalonia Lluís Companys (leader of the Republican Left of Catalonia

The Republican Left of Catalonia ( ca, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya, ERC; ; generically branded as ) is a pro-Catalan independence, social-democratic political party in the Spanish autonomous community of Catalonia, with a presence also i ...

and the President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

of the Generalitat of Catalonia) saw an opportunity in the general strike and declared Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the nort ...

an independent state inside the federal republic of Spain;Beevor (2006). p. 33. the Esquerra, however, refused to arm the populace, and the head of the military in Catalonia, Domingo Batet,See also: :es:Domingo Batet charged with putting down the revolt, showed similar restraint. In response, Lluís Companys was arrested and Catalan autonomy was suspended.

The 1934 strike was unsuccessful in most of Spain. However, in Asturias

Asturias (, ; ast, Asturies ), officially the Principality of Asturias ( es, Principado de Asturias; ast, Principáu d'Asturies; Galician-Asturian: ''Principao d'Asturias''), is an autonomous community in northwest Spain.

It is coextensiv ...

in northern Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, it developed into a bloody revolutionary uprising, trying to overthrow the legitimate democratic regime. Around 30,000 workers were called to arms in ten days. Armed with dynamite, rifles, carbines and light and heavy machine guns, the revolutionaries managed to take the whole province of Asturias committing numerous murders of policemen, clergymen and civilians and destroying religious buildings including churches, convents and part of the university at Oviedo. In the occupied areas the rebels officially declared the proletarian revolution and abolished regular money.

The war minister, Diego Hidalgo wanted General Franco to lead the troops. However, President Alcalá-Zamora, aware of Franco's monarchist sympathies, opted to send General López Ochoa to Asturias to lead the government forces; hoping that his reputation as a loyal Republican would minimize the bloodshed. Franco was put in informal command of the military effort against the revolt.

Government troops, some brought in from Spain's Army of Africa, killed men, women and children and carried out summary executions after the main cities of Asturias were retaken. About 1,000 workers were killed, with about 250 government soldiers left dead. Atrocities were carried out by both sides. The failed rising in Asturias marked the effective end of the Republic. Months of retaliation and repression followed; torture was used on political prisoners. Even moderate reformists within the CEDA became sidelined. The two generals in charge of the campaign, Franco and Manuel Goded Llopis

Manuel Goded Llopis (15 October 1882 – 12 August 1936) was a Spanish Army general who was one of the key figures in the July 1936 revolt against the democratically elected Second Spanish Republic. Having unsuccessfully led an attempted insur ...

, were seen as heroes. Azaña was unsuccessfully made out to be a revolutionary criminal by his right-wing opponents. Gil Robles once again prompted a cabinet collapse, and five positions in Lerroux's new government were conceded to CEDA, including one awarded to Gil Robles himself. Farm workers' wages were halved, and the military was purged of republican members and reformed. Those loyal to Robles were promoted, and Franco was made Chief of Staff.Preston (2006). p. 81. Stanley Payne believes that in the perspective of contemporary European history the repression of the 1934 revolution was relatively mild and that the key leaders of the rebellion were treated with leniency. There were no mass killing after the fighting was over as was in the case of the suppression of the Paris Commune or the Russian 1905 revolution; all death sentences were commuted aside from two, army sergeant and deserter Diego Vásquez, who fought alongside the miners, and a worker known as "El Pichilatu" who had committed serial killings. Little effort was actually made to suppress the organisations that had carried out the insurrection, resulting in most being functional again by 1935. Support for fascism was minimal and did not increase, while civil liberties were restored in full by 1935, after which the revolutionaries had a generous opportunity to pursue power through electoral means.

With this rebellion against established political legitimate authority, the Socialists showed identical repudiation of representative institutional system that anarchists had practiced. The Spanish historian Salvador de Madariaga

Salvador de Madariaga y Rojo (23 July 1886 – 14 December 1978) was a Spanish diplomat, writer, historian, and pacifist. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature, and the Nobel Peace Prize. He was awarded the Charlemagne Prize in 1 ...

, an Azaña's supporter, and an exiled vocal opponent of Francisco Franco asserted that: "The uprising of 1934 is unforgivable. The argument that Mr Gil Robles tried to destroy the Constitution to establish fascism was, at once, hypocritical and false. With the rebellion of 1934, the Spanish left lost even the shadow of moral authority to condemn the rebellion of 1936"

In 1935 Azaña and Indalecio Prieto started to unify the left and to combat its extreme elements. They staged large, popular rallies of what would become the Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

. Lerroux's Radical government collapsed after two major scandals, including the Straperlo affair. However, Zamora did not allow the CEDA to form a government, instead calling elections. The elections of 1936 were won by the Popular Front, with vastly smaller resources than the political right who followed Nazi propaganda

The propaganda used by the German Nazi Party in the years leading up to and during Adolf Hitler's dictatorship of Germany from 1933 to 1945 was a crucial instrument for acquiring and maintaining power, and for the implementation of Nazi polici ...

techniques. The right began to plan how to best overthrow the Republic, rather than taking control of it.

The government was weak, and the influence of the revolutionary Largo Caballero prevented socialists from being part of the cabinet. The republicans were left to govern alone; Azaña led a minority government.Preston (2006). p. 84. Pacification and reconciliation would have been a huge task. Largo Caballero accepted support from the Communist Party (with a membership of around 10,000). Acts of violence and reprisals increased.Preston (2006). p. 85. By early 1936, Azaña found that the left was using its influence to circumvent the Republic and the constitution; they were adamant about increasingly radical changes. Parliament replaced Zamora with Azaña in April. Zamora's removal was made on specious grounds, using a constitutional technicality. Azaña and Prieto hoped that by holding the positions of Prime Minister and President, they could push through enough reforms to pacify the left and deal with right-wing militancy. However, Azaña was increasingly isolated from everyday politics; his replacement, Casares Quiroga, was weak. Although the right also voted for Zamora's removal, this was a watershed event which inspired conservatives to give up on parliamentary politics.Preston (1999). pp. 17–23. Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

wrote that Zamora had been Spain's "stable pole", and his removal was another step towards revolution.Trotsky (1936). pp. 125–126. Largo Caballero held out for a collapse of the republican government, to be replaced with a socialist one as in France.

CEDA turned its campaign chest over to army plotter Emilio Mola

Emilio Mola y Vidal, 1st Duke of Mola, Grandee of Spain (9 July 1887 – 3 June 1937) was one of the three leaders of the Nationalist coup of July 1936, which started the Spanish Civil War.

After the death of Sanjurjo on 20 July 1936, Mo ...

. Monarchist José Calvo Sotelo

José Calvo Sotelo, 1st Duke of Calvo Sotelo, GE (6 May 1893 – 13 July 1936) was a Spanish jurist and politician, minister of Finance during the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera and a leading figure during the Second Republic. During t ...

replaced CEDA's Gil Robles as the right's leading spokesman in parliament. The Falange expanded rapidly, and many members of the Juventudes de Acción Popular

The Juventudes de Acción Popular (JAP) was the radicalised youth wing of the CEDA, the main Catholic party during part of the Second Spanish Republic. The organization underwent a process of fascistization whereas their members (''japistas'') shar ...

joined. They successfully created a sense of militancy on the streets to try to justify an authoritarian regime. Prieto did his best to avoid revolution by promoting a series of public works and civil order reforms, including of parts of the military and civil guard. Largo Caballero took a different attitude, continuing to preach of an inevitable overthrow of society by the workers.Preston (2006). p. 90. Largo Caballero also disagreed with Prieto's idea of a new Republican–Socialist coalition.Preston (2006). p. 92. With Largo Caballero's acquiescence, communists alarmed the middle classes by quickly taking over the ranks of socialist organisations. This alarmed the middle classes. The division of the Popular Front prevented the government from using its power to prevent right-wing militancy. The CEDA came under attack from the Falange, and Prieto's attempts at moderate reform were attacked by the Socialist Youth. Sotelo continued to do his best to make conciliation impossible.

Casares failed to heed Prieto's warnings of a military conspiracy involving several generals who disliked professional politicians and wanted to replace the government to prevent the dissolution of Spain. The military coup of July that started the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

was devised with Mola as director and Sanjurjo as a figurehead leader.Beevor (2006). p. 49.

See also

*Revisionism (Spain)

Revisionism ( es, Revisionismo) is a term which emerged in the late 1990s and is applied to a group of pro-Francoist historiographic theories related to the recent history of Spain.

History

Until the late 1990s in Spain the term ''revisionismo ...

Notes

Citations

Sources

Books

* * * * * * * * * * * * *Journals

* * * *Further reading

* {{Authority control Spanish Civil WarSpanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...