Babasaheb Ambedkar on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (14 April 1891 – 6 December 1956) was an Indian

As Ambedkar was educated by the Princely State of Baroda, he was bound to serve it. He was appointed Military Secretary to the Gaikwad but had to quit in a short time. He described the incident in his autobiography, '' Waiting for a Visa''. Thereafter, he tried to find ways to make a living for his growing family. He worked as a private tutor, as an accountant, and established an investment consulting business, but it failed when his clients learned that he was an untouchable. In 1918, he became Professor of Political Economy in the Sydenham College of Commerce and Economics in Mumbai. Although he was successful with the students, other professors objected to his sharing a drinking-water jug with them.

Ambedkar had been invited to testify before the

As Ambedkar was educated by the Princely State of Baroda, he was bound to serve it. He was appointed Military Secretary to the Gaikwad but had to quit in a short time. He described the incident in his autobiography, '' Waiting for a Visa''. Thereafter, he tried to find ways to make a living for his growing family. He worked as a private tutor, as an accountant, and established an investment consulting business, but it failed when his clients learned that he was an untouchable. In 1918, he became Professor of Political Economy in the Sydenham College of Commerce and Economics in Mumbai. Although he was successful with the students, other professors objected to his sharing a drinking-water jug with them.

Ambedkar had been invited to testify before the

In 1935, Ambedkar was appointed principal of the Government Law College, Bombay, a position he held for two years. He also served as the chairman of Governing body of Ramjas College,

In 1935, Ambedkar was appointed principal of the Government Law College, Bombay, a position he held for two years. He also served as the chairman of Governing body of Ramjas College,

"Arundhati Roy, the Not-So-Reluctant Renegade"

, New York Times ''Magazine'', 5 March 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2014. Later, in a 1955 BBC interview, he accused Gandhi of writing in opposition of the caste system in English language papers while writing in support of it in Gujarati language papers. During this time, Ambedkar also fought against the ''khoti'' system prevalent in

Ambedkar's first wife Ramabai died in 1935 after a long illness. After completing the draft of India's constitution in the late 1940s, he suffered from lack of sleep, had

Ambedkar's first wife Ramabai died in 1935 after a long illness. After completing the draft of India's constitution in the late 1940s, he suffered from lack of sleep, had

Ambedkar considered converting to

Ambedkar considered converting to

Since 1948, Ambedkar had

Since 1948, Ambedkar had

Ambedkar's legacy as a socio-political reformer had a deep effect on modern India. In post-Independence India, his socio-political thought is respected across the political spectrum. His initiatives have influenced various spheres of life and transformed the way India today looks at socio-economic policies, education and affirmative action through socio-economic and legal incentives. His reputation as a scholar led to his appointment as free India's first law minister, and chairman of the committee for drafting the constitution. He passionately believed in individual freedom and criticised caste society. His accusations of

Ambedkar's legacy as a socio-political reformer had a deep effect on modern India. In post-Independence India, his socio-political thought is respected across the political spectrum. His initiatives have influenced various spheres of life and transformed the way India today looks at socio-economic policies, education and affirmative action through socio-economic and legal incentives. His reputation as a scholar led to his appointment as free India's first law minister, and chairman of the committee for drafting the constitution. He passionately believed in individual freedom and criticised caste society. His accusations of

PDF

Primary sources * Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. ''Annihilation of caste: The annotated critical edition'' (Verso Books, 2014).

Ambedkar: The man behind India's constitution

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar: Timeline Index and more work by him

at the

Exhibition: "Educate. Agitate. Organise." Ambedkar and LSE

exhibition at the

Writings and Speeches of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar

in various languages at the Dr. Ambedkar Foundation,

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar's related articles

*

at the Ministry of External Affairs,

jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyses and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal qualification in law and often a legal practitioner. In the U ...

, economist

An economist is a professional and practitioner in the social sciences, social science discipline of economics.

The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy. Within this ...

, social reformer and political leader who headed the committee drafting the Constitution of India

The Constitution of India ( IAST: ) is the supreme law of India. The document lays down the framework that demarcates fundamental political code, structure, procedures, powers, and duties of government institutions and sets out fundamental ...

from the Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

debates, served as Law and Justice minister in the first cabinet of Jawaharlal Nehru, and inspired the Dalit Buddhist movement after renouncing Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

.

Ambedkar graduated from Elphinstone College

Elphinstone College is one of the constituent colleges of Dr. Homi Bhabha State University, a state cluster university. Established in 1823, it is one of the oldest colleges in Mumbai. It played a major role in shaping and developing the ed ...

, University of Bombay

The University of Mumbai is a collegiate, state-owned, public research university in Mumbai.

The University of Mumbai is one of the largest universities in the world. , the university had 711 affiliated colleges. Ratan Tata is the appointed h ...

, and studied economics at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

and the London School of Economics

, mottoeng = To understand the causes of things

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £240.8 million (2021)

, budget = £391.1 milli ...

, receiving doctorates in 1927 and 1923 respectively and was among a handful of Indian students to have done so at either institution in the 1920s. He also trained in the law at Gray's Inn

The Honourable Society of Gray's Inn, commonly known as Gray's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister in England and W ...

, London. In his early career, he was an economist, professor, and lawyer. His later life was marked by his political activities; he became involved in campaigning and negotiations for India's independence, publishing journals, advocating political rights and social freedom for Dalits, and contributing significantly to the establishment of the state of India. In 1956, he converted to Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

, initiating mass conversions of Dalits.

In 1990, the ''Bharat Ratna

The Bharat Ratna (; ''Jewel of India'') is the highest Indian honours system, civilian award of the Republic of India. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is conferred in recognition of "exceptional service/performance of the highest orde ...

'', India's highest civilian award, was posthumously conferred on Ambedkar. The salutation '' Jai Bhim'' ( lit. "Hail Bhim") used by followers honours him. He is also referred to by the honorific Babasaheb ( ), meaning "Respected Father".

Early life

Ambedkar was born on 14 April 1891 in the town and military cantonment ofMhow

Mhow, officially Dr. Ambedkar Nagar, is a town in the Indore district in Madhya Pradesh state of India. It is located south-west of Indore city, towards Mumbai on the old Mumbai-Agra Road. The town was renamed as ''Dr. Ambedkar Nagar'' in 20 ...

(now officially known as Dr Ambedkar Nagar) (now in Madhya Pradesh

Madhya Pradesh (, ; meaning 'central province') is a state in central India. Its capital is Bhopal, and the largest city is Indore, with Jabalpur, Ujjain, Gwalior, Sagar, and Rewa being the other major cities. Madhya Pradesh is the second ...

). He was the 14th and last child of Ramji Maloji Sakpal, an army officer who held the rank of Subedar

Subedar is a rank of junior commissioned officer in the Indian Army; a senior non-commissioned officer in the Pakistan Army, and formerly a Viceroy's commissioned officer in the British Indian Army.

History

''Subedar'' or ''subadar'' was t ...

, and Bhimabai Sakpal, daughter of Laxman Murbadkar. His family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

was of Marathi background from the town of Ambadawe

Ambadawe is a village in the Mandangad taluk of Ratnagiri district in Maharashtra, India. This village is family origin of B. R. Ambedkar, Architect of constitution of India.

Census data

Notable people

* The family origins of B. R. Amb ...

( Mandangad taluka) in Ratnagiri district

Ratnagiri District (Marathi pronunciation: �ət̪n̪aːɡiɾiː is a district in the state of Maharashtra, India. The administrative headquarter of the district is located in the town of Ratnagiri. The district is 11.33% urban. The district ...

of modern-day Maharashtra

Maharashtra (; , abbr. MH or Maha) is a state in the western peninsular region of India occupying a substantial portion of the Deccan Plateau. Maharashtra is the second-most populous state in India and the second-most populous country subdi ...

. Ambedkar was born into a Mahar (dalit) caste, who were treated as untouchables and subjected to socio-economic discrimination. Ambedkar's ancestors had long worked for the army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

of the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

, and his father served in the British Indian Army

The British Indian Army, commonly referred to as the Indian Army, was the main military of the British Raj before its dissolution in 1947. It was responsible for the defence of the British Indian Empire, including the princely states, which cou ...

at the Mhow cantonment.

Although they attended school, Ambedkar and other untouchable children were segregated and given little attention or help by teachers. They were not allowed to sit inside the class. When they needed to drink water, someone from a higher caste had to pour that water from a height as they were not allowed to touch either the water or the vessel that contained it. This task was usually performed for the young Ambedkar by the school peon

Peon (English , from the Spanish ''peón'' ) usually refers to a person subject to peonage: any form of wage labor, financial exploitation, coercive economic practice, or policy in which the victim or a laborer (peon) has little control over em ...

, and if the peon was not available then he had to go without water; he described the situation later in his writings as ''"No peon, No Water"''. He was required to sit on a gunny sack which he had to take home with him.

Ramji Sakpal retired in 1894 and the family moved to Satara two years later. Shortly after their move, Ambedkar's mother died. The children were cared for by their paternal aunt and lived in difficult circumstances. Three sons – Balaram, Anandrao and Bhimrao – and two daughters – Manjula and Tulasa – of the Ambedkars survived them. Of his brothers and sisters, only Ambedkar passed his examinations and went to high school. His original surname was ''Sakpal'' but his father registered his name as ''Ambadawekar'' in school, meaning he comes from his native village 'Ambadawe

Ambadawe is a village in the Mandangad taluk of Ratnagiri district in Maharashtra, India. This village is family origin of B. R. Ambedkar, Architect of constitution of India.

Census data

Notable people

* The family origins of B. R. Amb ...

' in Ratnagiri district. His Marathi Brahmin

Marathi Brahmins (also known as Maharashtrian Brahmins), are communities native to the Indian state of Maharashtra. They are classified into mainly three sub-divisions based on their places of origin, " Desh", " Karad" and "Konkan". The Brahmi ...

teacher, Krishnaji Keshav Ambedkar, changed his surname from 'Ambadawekar' to his own surname 'Ambedkar' in school records.

Education

Post-secondary education

In 1897, Ambedkar's family moved to Mumbai where Ambedkar became the only untouchable enrolled atElphinstone High School

Elphinstone High School was a school established in 1822 in Bombay, India in honour of Mountstuart Elphinstone, Governor of Bombay (1819–1827). In 1834 the Elphinstone Institute was founded, which started the Elphinstone College

Elphins ...

. In 1906, when he was about 15 years old, he married a nine-year-old girl, Ramabai. The match per the customs prevailing at that time was arranged

In music, an arrangement is a musical adaptation of an existing composition. Differences from the original composition may include reharmonization, melodic paraphrasing, orchestration, or formal development. Arranging differs from orchest ...

by the couple's parents.

Studies at the University of Bombay

In 1907, he passed his matriculation examination and in the following year he enteredElphinstone College

Elphinstone College is one of the constituent colleges of Dr. Homi Bhabha State University, a state cluster university. Established in 1823, it is one of the oldest colleges in Mumbai. It played a major role in shaping and developing the ed ...

, which was affiliated to the University of Bombay

The University of Mumbai is a collegiate, state-owned, public research university in Mumbai.

The University of Mumbai is one of the largest universities in the world. , the university had 711 affiliated colleges. Ratan Tata is the appointed h ...

, becoming, according to him, the first from his Mahar caste to do so. When he passed his English fourth standard examinations, the people of his community wanted to celebrate because they considered that he had reached "great heights" which he says was "hardly an occasion compared to the state of education in other communities". A public ceremony was evoked, to celebrate his success, by the community, and it was at this occasion that he was presented with a biography of the Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in L ...

by Dada Keluskar, the author and a family friend.

By 1912, he obtained his degree in economics and political science from Bombay University, and prepared to take up employment with the Baroda state government. His wife had just moved his young family and started work when he had to quickly return to Mumbai to see his ailing father, who died on 2 February 1913.

Studies at Columbia University

In 1913, at the age of 22, Ambedkar was awarded a Baroda State Scholarship of £11.50 (Sterling) per month for three years under a scheme established bySayajirao Gaekwad III

Sayajirao Gaekwad III (born Shrimant Gopalrao Gaekwad; 11 March 1863 – 6 February 1939) was the Maharaja of Baroda State from 1875 to 1939, and is remembered for reforming much of his state during his rule. He belonged to the royal Ga ...

( Gaekwad of Baroda

Vadodara (), also known as Baroda, is the second largest city in the Indian state of Gujarat. It serves as the administrative headquarters of the Vadodara district and is situated on the banks of the Vishwamitri River, from the state capital ...

) that was designed to provide opportunities for postgraduate education at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. Soon after arriving there he settled in rooms at Livingston Hall with Naval Bhathena, a Parsi

Parsis () or Parsees are an ethnoreligious group of the Indian subcontinent adhering to Zoroastrianism. They are descended from Persians who migrated to Medieval India during and after the Arab conquest of Iran (part of the early Muslim conq ...

who was to be a lifelong friend. He passed his M.A. exam in June 1915, majoring in economics, and other subjects of Sociology, History, Philosophy and Anthropology. He presented a thesis, ''Ancient Indian Commerce''. Ambedkar was influenced by John Dewey

John Dewey (; October 20, 1859 – June 1, 1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer whose ideas have been influential in education and social reform. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the fi ...

and his work on democracy.

In 1916, he completed his second master's thesis, ''National Dividend of India – A Historic and Analytical Study'', for a second M.A. On 9 May, he presented the paper '' Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development'' before a seminar conducted by the anthropologist Alexander Goldenweiser. Ambedkar received his Ph.D. degree in economics at Columbia in 1927.

Studies at the London School of Economics

In October 1916, he enrolled for the Bar course atGray's Inn

The Honourable Society of Gray's Inn, commonly known as Gray's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister in England and W ...

, and at the same time enrolled at the London School of Economics

, mottoeng = To understand the causes of things

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £240.8 million (2021)

, budget = £391.1 milli ...

where he started working on a doctoral thesis. In June 1917, he returned to India because his scholarship from Baroda ended. His book collection was dispatched on a different ship from the one he was on, and that ship was torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine. He got permission to return to London to submit his thesis within four years. He returned at the first opportunity, and completed a master's degree in 1921. His thesis was on "The problem of the rupee: Its origin and its solution". In 1923, he completed a D.Sc. in Economics which was awarded from University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degr ...

, and the same year he was called to the Bar by Gray's Inn.

Opposition to untouchability

As Ambedkar was educated by the Princely State of Baroda, he was bound to serve it. He was appointed Military Secretary to the Gaikwad but had to quit in a short time. He described the incident in his autobiography, '' Waiting for a Visa''. Thereafter, he tried to find ways to make a living for his growing family. He worked as a private tutor, as an accountant, and established an investment consulting business, but it failed when his clients learned that he was an untouchable. In 1918, he became Professor of Political Economy in the Sydenham College of Commerce and Economics in Mumbai. Although he was successful with the students, other professors objected to his sharing a drinking-water jug with them.

Ambedkar had been invited to testify before the

As Ambedkar was educated by the Princely State of Baroda, he was bound to serve it. He was appointed Military Secretary to the Gaikwad but had to quit in a short time. He described the incident in his autobiography, '' Waiting for a Visa''. Thereafter, he tried to find ways to make a living for his growing family. He worked as a private tutor, as an accountant, and established an investment consulting business, but it failed when his clients learned that he was an untouchable. In 1918, he became Professor of Political Economy in the Sydenham College of Commerce and Economics in Mumbai. Although he was successful with the students, other professors objected to his sharing a drinking-water jug with them.

Ambedkar had been invited to testify before the Southborough Committee

The Southborough Committee, referred to at the time as the Franchise Committee, was one of three British committees which sat in India from 1918 to 1919, including also the Committee on Home Administration and the Feetham Function Committee.

Th ...

, which was preparing the Government of India Act 1919

The Government of India Act 1919 (9 & 10 Geo. 5 c. 101) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It was passed to expand participation of Indians in the government of India. The Act embodied the reforms recommended in the report o ...

. At this hearing, Ambedkar argued for creating separate electorate

Electorate may refer to:

* The people who are eligible to vote in an election, especially their number e.g. the term ''size of (the) electorate''

* The dominion of a Prince-elector in the Holy Roman Empire until 1806

* An electoral district or c ...

s and reservation __NOTOC__

Reservation may refer to: Places

Types of places:

* Indian reservation, in the United States

* Military base, often called reservations

* Nature reserve

Government and law

* Reservation (law), a caveat to a treaty

* Reservation in India, ...

s for untouchables and other religious communities. In 1920, he began the publication of the weekly ''Mooknayak'' (Leader of the Silent) in Mumbai with the help of Shahu of Kolhapur, that is, Shahu IV (1874–1922).

Ambedkar went on to work as a legal professional. In 1926, he successfully defended three non-Brahmin leaders who had accused the Brahmin community of ruining India and were then subsequently sued for libel. Dhananjay Keer notes, "The victory was resounding, both socially and individually, for the clients and the doctor".

While practising law in the Bombay High Court

The High Court of Bombay is the high court of the states of Maharashtra and Goa in India, and the union territory of Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu. It is seated primarily at Mumbai (formerly known as Bombay), and is one of the ...

, he tried to promote education to untouchables and uplift them. His first organised attempt was his establishment of the central institution Bahishkrit Hitakarini Sabha

{{Use Indian English, date=November 2018

Bahishkrit Hitakarini Sabha ( hi, बहिष्कृत हितकारिणी सभा) is a central institution formed by Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar for removing difficulties of the untouchables an ...

, intended to promote education and socio-economic improvement, as well as the welfare of " outcastes", at the time referred to as depressed classes. For the defence of Dalit rights, he started many periodicals like ''Mook Nayak'', ''Bahishkrit Bharat'', and ''Equality Janta''.

He was appointed to the Bombay Presidency Committee to work with the all-European Simon Commission

The Indian Statutory Commission also known as Simon Commission, was a group of seven Members of Parliament under the chairmanship of Sir John Simon. The commission arrived in India in 1928 to study constitutional reform in Britain's largest a ...

in 1925. This commission had sparked great protests across India, and while its report was ignored by most Indians, Ambedkar himself wrote a separate set of recommendations for the future Constitution of India.

By 1927, Ambedkar had decided to launch active movements against untouchability

Untouchability is a form of social institution that legitimises and enforces practices that are discriminatory, humiliating, exclusionary and exploitative against people belonging to certain social groups. Although comparable forms of discrimin ...

. He began with public movements and marches to open up public drinking water resources. He also began a struggle for the right to enter Hindu temples. He led '' a satyagraha'' in Mahad to fight for the right of the untouchable community to draw water from the main water tank of the town. In a conference in late 1927, Ambedkar publicly condemned the classic Hindu text, the Manusmriti

The ''Manusmṛiti'' ( sa, मनुस्मृति), also known as the ''Mānava-Dharmaśāstra'' or Laws of Manu, is one of the many legal texts and constitution among the many ' of Hinduism. In ancient India, the sages often wrote the ...

(Laws of Manu), for ideologically justifying caste discrimination and "untouchability", and he ceremonially burned copies of the ancient text. On 25 December 1927, he led thousands of followers to burn copies of Manusmriti. Thus annually 25 December is celebrated as ''Manusmriti Dahan Din

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (14 April 1891 – 6 December 1956) was an Indian jurist, economist, social reformer and political leader who headed the committee drafting the Constitution of India from the Constituent Assembly debates, served ...

'' (Manusmriti Burning Day) by Ambedkarites and Dalit

Dalit (from sa, दलित, dalita meaning "broken/scattered"), also previously known as untouchable, is the lowest stratum of the castes in India. Dalits were excluded from the four-fold varna system of Hinduism and were seen as forming ...

s.

In 1930, Ambedkar launched the Kalaram Temple movement after three months of preparation. About 15,000 volunteers assembled at Kalaram Temple

The Kalaram Temple is an old Hindu shrine dedicated to Rama in the Panchavati area of Nashik city in Maharashtra, India.

The temple derives its name from a black statue of Lord Rama. The literal translation of ''kalaram'' is "black Rama". The s ...

satygraha making one of the greatest processions of Nashik

Nashik (, Marathi: aːʃik, also called as Nasik ) is a city in the northern region of the Indian state of Maharashtra. Situated on the banks of river Godavari, Nashik is the third largest city in Maharashtra, after Mumbai and Pune. Nash ...

. The procession was headed by a military band and a batch of scouts; women and men walked with discipline, order and determination to see the god for the first time. When they reached the gates, the gates were closed by Brahmin authorities.

Poona Pact

In 1932, the British colonial government announced the formation of a separate electorate for "Depressed Classes" in the Communal Award.Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

fiercely opposed a separate electorate for untouchables, saying he feared that such an arrangement would divide the Hindu community. Gandhi protested by fasting while imprisoned in the Yerwada Central Jail

Yerwada Central Jail is a noted high-security prison in Yerwada, Pune in Maharashtra. This is the largest prison in the state of Maharashtra, and also one of the largest prisons in South Asia, housing over 5,000 prisoners (2017) spread over va ...

of Poona

Pune (; ; also known as Poona, ( the official name from 1818 until 1978) is one of the most important industrial and educational hubs of India, with an estimated population of 7.4 million As of 2021, Pune Metropolitan Region is the largest i ...

. Following the fast, congressional politicians and activists such as Madan Mohan Malaviya and Palwankar Baloo

Palwankar Baloo was an Indian cricketer and political activist. In 1896, he was selected by Parmanandas Jivandas Hindu Gymkhana and played in the Bombay Quadrangular tournaments. He was employed by the Bombay Berar and Central Indian Railways, a ...

organised joint meetings with Ambedkar and his supporters at Yerwada. On 25 September 1932, the agreement, known as the Poona Pact

The Poona Pact was an agreement between Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. B. R. Ambedkar on behalf of Dalits, depressed classes, and upper caste Hindu leaders on the reservation of electoral seats for the depressed classes in the legislature of Brit ...

was signed between Ambedkar (on behalf of the depressed classes among Hindus) and Madan Mohan Malaviya (on behalf of the other Hindus). The agreement gave reserved seats for the depressed classes in the Provisional legislatures within the general electorate. Due to the pact the depressed class received 148 seats in the legislature instead of the 71, as allocated in the Communal Award proposed earlier by the colonial government under Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

. The text used the term "Depressed Classes" to denote Untouchables among Hindus who were later called Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes under the India Act 1935, and the later Indian Constitution of 1950. In the Poona Pact, a unified electorate was in principle formed, but primary and secondary elections allowed Untouchables in practice to choose their own candidates.

Political career

In 1935, Ambedkar was appointed principal of the Government Law College, Bombay, a position he held for two years. He also served as the chairman of Governing body of Ramjas College,

In 1935, Ambedkar was appointed principal of the Government Law College, Bombay, a position he held for two years. He also served as the chairman of Governing body of Ramjas College, University of Delhi

Delhi University (DU), formally the University of Delhi, is a collegiate central university located in New Delhi, India. It was founded in 1922 by an Act of the Central Legislative Assembly and is recognized as an Institute of Eminence (IoE ...

, after the death of its Founder Shri Rai Kedarnath. Settling in Bombay (today called Mumbai), Ambedkar oversaw the construction of a house, and stocked his personal library with more than 50,000 books. His wife Ramabai died after a long illness the same year. It had been her long-standing wish to go on a pilgrimage to Pandharpur

Pandharpur (Pronunciation: əɳɖʱəɾpuːɾ is a well known pilgrimage town, on the banks of Candrabhagā River, near Solapur city in Solapur District, Maharashtra, India. Its administrative area is one of eleven tehsils in the District ...

, but Ambedkar had refused to let her go, telling her that he would create a new Pandharpur for her instead of Hinduism's Pandharpur which treated them as untouchables. At the Yeola Conversion Conference on 13 October in Nasik, Ambedkar announced his intention to convert to a different religion and exhorted his followers to leave Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

. He would repeat his message at many public meetings across India.

In 1936, Ambedkar founded the Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

, which contested the 1937 Bombay election to the Central Legislative Assembly

The Central Legislative Assembly was the lower house of the Imperial Legislative Council, the legislature of British India. It was created by the Government of India Act 1919, implementing the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms. It was also sometim ...

for the 13 reserved and 4 general seats, and secured 11 and 3 seats respectively.

Ambedkar published his book ''Annihilation of Caste

''Annihilation of Caste'' is an undelivered speech written in 1936 by B. R. Ambedkar, an Indian academic turned politician. He wrote ''Annihilation of Caste'' for the 1936 meeting of a group of liberal Hindu caste-reformers in Lahore. After rev ...

'' on 15 May 1936. It strongly criticised Hindu orthodox religious leaders and the caste system in general, and included "a rebuke of Gandhi" on the subject. Deb, Siddhartha"Arundhati Roy, the Not-So-Reluctant Renegade"

, New York Times ''Magazine'', 5 March 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2014. Later, in a 1955 BBC interview, he accused Gandhi of writing in opposition of the caste system in English language papers while writing in support of it in Gujarati language papers. During this time, Ambedkar also fought against the ''khoti'' system prevalent in

Konkan

The Konkan ( kok, कोंकण) or Kokan () is a stretch of land by the western coast of India, running from Damaon in the north to Karwar in the south; with the Arabian Sea to the west and the Deccan plateau in the east. The hinterland ...

, where ''khots'', or government revenue collectors, regularly exploited farmers and tenants. In 1937, Ambedkar tabled a bill in the Bombay Legislative Assembly aimed at abolishing the ''khoti'' system by creating a direct relationship between government and farmers.

Ambedkar served on the Defence Advisory Committee and the Viceroy's Executive Council as minister for labour. Before the Day of Deliverance events, Ambedkar stated that he was interested in participating: "I read Mr. Jinnah's statement and I felt ashamed to have allowed him to steal a march over me and rob me of the language and the sentiment which I, more than Mr. Jinnah, was entitled to use." He went on to suggest that the communities he worked with were twenty times more oppressed by Congress policies than were Indian Muslims; he clarified that he was criticizing Congress, and not all Hindus. Jinnah and Ambedkar jointly addressed the heavily attended Day of Deliverance event in Bhindi Bazaar, Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — List of renamed Indian cities and states#Maharashtra, the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' fin ...

, where both expressed "fiery" criticisms of the Congress party, and according to one observer, suggested that Islam and Hinduism were irreconcilable.

After the Lahore resolution (1940) of the Muslim League demanding Pakistan, Ambedkar wrote a 400-page tract titled ''Thoughts on Pakistan'', which analysed the concept of "Pakistan" in all its aspects. Ambedkar argued that the Hindus should concede Pakistan to the Muslims. He proposed that the provincial boundaries of Punjab and Bengal should be redrawn to separate the Muslim and non-Muslim majority parts. He thought the Muslims could have no objection to redrawing provincial boundaries. If they did, they did not quite "understand the nature of their own demand". Scholar Venkat Dhulipala states that ''Thoughts on Pakistan'' "rocked Indian politics for a decade". It determined the course of dialogue between the Muslim League and the Indian National Congress, paving the way for the Partition of India

The Partition of British India in 1947 was the change of political borders and the division of other assets that accompanied the dissolution of the British Raj in South Asia and the creation of two independent dominions: India and Pakistan. T ...

.

In his work ''Who Were the Shudras?

''Who Were the Shudras?'' is a history book published by Indian social reformer and polymath B. R. Ambedkar in 1946. The book discusses the origin of the Shudra Varna. Ambedkar dedicated the book to Jyotirao Phule (1827–1890).

Subject of the b ...

'', Ambedkar tried to explain the formation of untouchables. He saw Shudras and Ati Shudras who form the lowest caste in the ritual hierarchy of the caste system

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultural ...

, as separate from Untouchables. Ambedkar oversaw the transformation of his political party into the Scheduled Castes Federation

The Republican Party of India (RPI, often called the Republican Party or simply Republican) is a political party in India. It has its roots in the Scheduled Castes Federation led by B. R. Ambedkar. The 'Training School for Entrance to Polit ...

, although it performed poorly in the 1946 elections for Constituent Assembly of India

The Constituent Assembly of India was elected to frame the Constitution of India. It was elected by the 'Provincial Assembly'. Following India's independence from the British rule in 1947, its members served as the nation's first Parliament as ...

. Later he was elected into the constituent assembly of Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

where Muslim League Muslim League may refer to:

Political parties Subcontinent

; British India

*All-India Muslim League, Mohammed Ali Jinah, led the demand for the partition of India resulting in the creation of Pakistan.

**Punjab Muslim League, a branch of the organ ...

was in power.

Ambedkar contested in the Bombay North first Indian General Election of 1952, but lost to his former assistant and Congress Party candidate Narayan Kajrolkar. Ambedkar became a member of Rajya Sabha

The Rajya Sabha, constitutionally the Council of States, is the upper house of the bicameral Parliament of India. , it has a maximum membership of 245, of which 233 are elected by the legislatures of the states and union territories using si ...

, probably an appointed member. He tried to enter Lok Sabha

The Lok Sabha, constitutionally the House of the People, is the lower house of India's bicameral Parliament, with the upper house being the Rajya Sabha. Members of the Lok Sabha are elected by an adult universal suffrage and a first-p ...

again in the by-election of 1954 from Bhandara, but he placed third (the Congress Party won). By the time of the second general election in 1957, Ambedkar had died.

Ambedkar also criticised Islamic practice in South Asia. While justifying the Partition of India

The Partition of British India in 1947 was the change of political borders and the division of other assets that accompanied the dissolution of the British Raj in South Asia and the creation of two independent dominions: India and Pakistan. T ...

, he condemned child marriage and the mistreatment of women in Muslim society.

The drafting of India's Constitution

Upon India's independence on 15 August 1947, the new prime ministerJawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India du ...

invited Ambedkar to serve as the Dominion of India

The Dominion of India, officially the Union of India,* Quote: “The first collective use (of the word "dominion") occurred at the Colonial Conference (April to May 1907) when the title was conferred upon Canada and Australia. New Zealand and N ...

's Law Minister

A minister is a politician who heads a ministry, making and implementing decisions on policies in conjunction with the other ministers. In some jurisdictions the head of government is also a minister and is designated the ‘prime minister’, ...

; two weeks later, he was appointed Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Constitution for the future Republic of India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

.

On 25 November 1949, Ambedkar in his concluding speech in constituent assembly said:-

Indian constitution guarantees and protections for a wide range of civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties ma ...

for individual citizens, including freedom of religion, the abolition of untouchability, and the outlawing of all forms of discrimination. Ambedkar argued for extensive economic and social rights for women, and won the Assembly's support for introducing a system of reservations of jobs in the civil services, schools and colleges for members of scheduled caste

The Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) are officially designated groups of people and among the most disadvantaged socio-economic groups in India. The terms are recognized in the Constitution of India and the groups are designa ...

s and scheduled tribe

The Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) are officially designated groups of people and among the most disadvantaged socio-economic groups in India. The terms are recognized in the Constitution of India and the groups are designa ...

s and Other Backward Class

The Other Backward Class is a collective term used by the Government of India to classify castes which are educationally or socially backward. It is one of several official classifications of the population of India, along with General castes, ...

, a system akin to affirmative action. India's lawmakers hoped to eradicate the socio-economic inequalities and lack of opportunities for India's depressed classes through these measures. The Constitution was adopted on 26 November 1949 by the Constituent Assembly.

Economics

Ambedkar was the first Indian to pursue a doctorate in economics abroad. He argued that industrialisation and agricultural growth could enhance the Indian economy. He stressed investment in agriculture as the primary industry of India. According toSharad Pawar

Sharad Govindrao Pawar (Marathi pronunciation: �əɾəd̪ pəʋaːɾ born 12 December 1940) is an Indian politician. He has served as the Chief Minister of Maharashtra on four occasions. He has held the posts of Minister of Defence and Mini ...

, Ambedkar's vision helped the government to achieve its food security goal. Ambedkar advocated national economic and social development, stressing education, public hygiene, community health, residential facilities as the basic amenities. His DSc thesis, ''The problem of the Rupee: Its Origin and Solution'' (1923) examines the causes for the Rupee's fall in value. In this dissertation, he argued in favour of a gold standard in modified form, and was opposed to the gold-exchange standard favoured by Keynes in his treatise ''Indian Currency and Finance'' (1909), claiming it was less stable. He favoured the stoppage of all further coinage of the rupee and the minting of a gold coin, which he believed would fix currency rates and prices.

He also analysed revenue in his PhD dissertation ''The Evolution of Provincial Finance in British India''. In this work, he analysed the various systems used by the British colonial government to manage finances in India. His views on finance were that governments should ensure their expenditures have "faithfulness, wisdom and economy." "Faithfulness" meaning governments should use money as nearly as possible to the original intentions of spending the money in the first place. "Wisdom" meaning it should be used as well as possible for the public good, and "economy" meaning the funds should be used so that the maximum value can be extracted from them.

In 1951, Ambedkar established the Finance Commission of India. He opposed income tax for low-income groups. He contributed in Land Revenue Tax and excise duty policies to stabilise the economy. He played an important role in land reform and the state economic development. According to him, the caste system, due to its division of labourers and hierarchical nature, impedes movement of labour (higher castes would not do lower-caste occupations) and movement of capital (assuming investors would invest first in their own caste occupation). His theory of State Socialism had three points: state ownership of agricultural land, the maintenance of resources for production by the state, and a just distribution of these resources to the population. He emphasised a free economy with a stable Rupee which India has adopted recently. He advocated birth control to develop the Indian economy, and this has been adopted by Indian government as national policy for family planning. He emphasised equal rights for women for economic development.

Ambedkar's views on agricultural land was that too much of it was idle, or that it was not being utilized properly. He believed there was an "ideal proportion" of production factors that would allow agricultural land to be used most productively. To this end, he saw the large portion of people who lived on agriculture at the time as a major problem. Therefore, he advocated industrialization of the economy to allow these agricultural labourers to be of more use elsewhere.

Ambedkar was trained as an economist, and was a professional economist until 1921, when he became a political leader. He wrote three scholarly books on economics:

* ''Administration and Finance of the East India Company''

* ''The Evolution of Provincial Finance in British India''

* ''The Problem of the Rupee: Its Origin and Its Solution''

The Reserve Bank of India

The Reserve Bank of India, chiefly known as RBI, is India's central bank and regulatory body responsible for regulation of the Indian banking system. It is under the ownership of Ministry of Finance, Government of India. It is responsible f ...

(RBI), was based on the ideas that Ambedkar presented to the Hilton Young Commission.

Second marriage

Ambedkar's first wife Ramabai died in 1935 after a long illness. After completing the draft of India's constitution in the late 1940s, he suffered from lack of sleep, had

Ambedkar's first wife Ramabai died in 1935 after a long illness. After completing the draft of India's constitution in the late 1940s, he suffered from lack of sleep, had neuropathic pain

Neuropathic pain is pain caused by damage or disease affecting the somatosensory system. Neuropathic pain may be associated with abnormal sensations called dysesthesia or pain from normally non-painful stimuli (allodynia). It may have continuous ...

in his legs, and was taking insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the ''INS'' gene. It is considered to be the main anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabolism ...

and homoeopathic medicines. He went to Bombay for treatment, and there met Sharada Kabir, whom he married on 15 April 1948, at his home in New Delhi. Doctors recommended a companion who was a good cook and had medical knowledge to care for him. She adopted the name Savita Ambedkar

Savita Bhimrao Ambedkar ( Kabir; 27 January 1909 – 29 May 2003), was an Indian social activist, doctor and the second wife of Babasaheb Ambedkar. Ambedkarites and Buddhists refer to her as Mai or Maisaheb, which stands for 'Mother' in Marat ...

and cared for him the rest of his life. Savita Ambedkar, who was called also 'Mai', died on May 29, 2003, aged 93 in Mumbai.

Conversion to Buddhism

Ambedkar considered converting to

Ambedkar considered converting to Sikhism

Sikhism (), also known as Sikhi ( pa, ਸਿੱਖੀ ', , from pa, ਸਿੱਖ, lit=disciple', 'seeker', or 'learner, translit=Sikh, label=none),''Sikhism'' (commonly known as ''Sikhī'') originated from the word ''Sikh'', which comes fro ...

, which encouraged opposition to oppression and so appealed to leaders of scheduled castes. But after meeting with Sikh leaders, he concluded that he might get "second-rate" Sikh status.

Instead, around 1950, he began devoting his attention to Buddhism and travelled to Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

(now Sri Lanka) to attend a meeting of the World Fellowship of Buddhists. While dedicating a new Buddhist vihara near Pune

Pune (; ; also known as Poona, ( the official name from 1818 until 1978) is one of the most important industrial and educational hubs of India, with an estimated population of 7.4 million As of 2021, Pune Metropolitan Region is the largest i ...

, Ambedkar announced he was writing a book on Buddhism, and that when it was finished, he would formally convert to Buddhism. He twice visited Burma in 1954; the second time to attend the third conference of the World Fellowship of Buddhists in Rangoon

Yangon ( my, ရန်ကုန်; ; ), formerly spelled as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar (also known as Burma). Yangon served as the capital of Myanmar until 2006, when the military government ...

. In 1955, he founded the Bharatiya Bauddha Mahasabha, or the Buddhist Society of India. In 1956, he completed his final work, '' The Buddha and His Dhamma'', which was published posthumously.

After meetings with the Sri Lankan Buddhist monk Hammalawa Saddhatissa

Hammalawa Saddhatissa Maha Thera (1914–1990) was an ordained Buddhist monk, missionary and author from Sri Lanka, educated in Varanasi, London, and Edinburgh. He was a contemporary of Walpola Rahula, also of Sri Lanka.

Early life

Saddhati ...

, Ambedkar organised a formal public ceremony for himself and his supporters in Nagpur

Nagpur (pronunciation: aːɡpuːɾ is the third largest city and the winter capital of the Indian state of Maharashtra. It is the 13th largest city in India by population and according to an Oxford's Economics report, Nagpur is projected to ...

on 14 October 1956. Accepting the Three Refuges and Five Precepts

The Five precepts ( sa, pañcaśīla, italic=yes; pi, pañcasīla, italic=yes) or five rules of training ( sa, pañcaśikṣapada, italic=yes; pi, pañcasikkhapada, italic=yes) is the most important system of morality for Buddhist lay peo ...

from a Buddhist monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedic ...

in the traditional manner, Ambedkar completed his own conversion, along with his wife. He then proceeded to convert some 500,000 of his supporters who were gathered around him. He prescribed the 22 Vows

The Twenty-two vows or twenty-two pledges are the 22 Buddhist vows administered by B. R. Ambedkar, the revivalist of Buddhism in India, to his followers. On converting to Buddhism, Ambedkar made 22 vows, and asked his 600,000 supporters to do ...

for these converts, after the Three Jewels and Five Precepts. He then travelled to Kathmandu

, pushpin_map = Nepal Bagmati Province#Nepal#Asia

, coordinates =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name =

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 = Bagmati Prov ...

, Nepal to attend the Fourth World Buddhist Conference. His work on ''The Buddha or Karl Marx'' and "Revolution and counter-revolution in ancient India" remained incomplete.

Death

Since 1948, Ambedkar had

Since 1948, Ambedkar had diabetes

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level ( hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ...

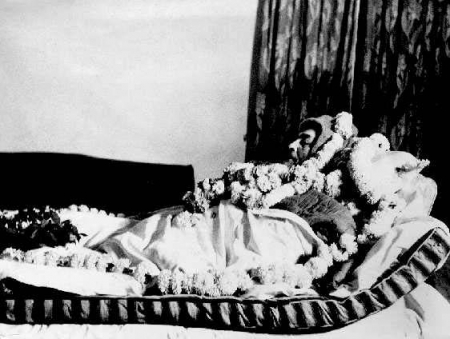

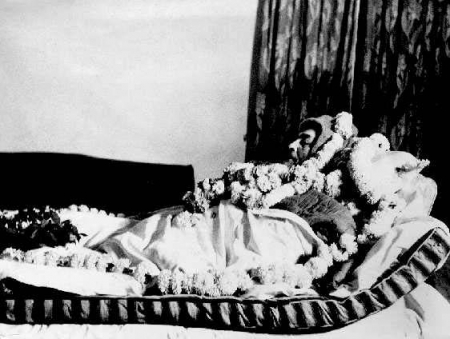

. He remained in bed from June to October in 1954 due to medication side-effects and poor eyesight. His health worsened during 1955. Three days after completing his final manuscript '' The Buddha and His Dhamma'', Ambedkar died in his sleep on 6 December 1956 at his home in Delhi.

A Buddhist cremation was organised at Dadar Chowpatty

Girgaon Chowpatty (IAST: ''Giragāva Chaupāṭī''), is a public beach along the Queen’s Necklace adjoining Marine Drive in the Girgaon area of Mumbai (Bombay), Konkan division, India. It is served by the Charni Road railway station. The ...

beach on 7 December, attended by half a million grieving people. A conversion program was organised on 16 December 1956, so that cremation attendees were also converted to Buddhism at the same place.

Ambedkar was survived by his second wife Savita Ambedkar

Savita Bhimrao Ambedkar ( Kabir; 27 January 1909 – 29 May 2003), was an Indian social activist, doctor and the second wife of Babasaheb Ambedkar. Ambedkarites and Buddhists refer to her as Mai or Maisaheb, which stands for 'Mother' in Marat ...

(known as Maisaheb Ambedkar), who died in 2003, and his son Yashwant Ambedkar

Yashwant Bhimrao Ambedkar (12 December 1912 — 17 September 1977), also known as Bhaiyasaheb Ambedkar, was an Indian socio-religious activist, newspaper editor, politician, and activist of Ambedkarite Buddhist movement. He was the first and on ...

(known as Bhaiyasaheb Ambedkar), who died in 1977. Savita and Yashwant carried on the socio-religious movement started by B. R. Ambedkar. Yashwant served as the 2nd President of the Buddhist Society of India (1957–1977) and a member of the Maharashtra Legislative Council (1960–1966). Ambedkar's elder grandson, Prakash Yashwant Ambedkar

Prakash Yashwant Ambedkar (born 10 May 1954), popularly known as Balasaheb Ambedkar, is an Indian politician, writer and lawyer. He is the president of political party called Bharipa Bahujan Mahasangh. He is a three-time Member of Parliament ...

, is the chief-adviser of the Buddhist Society of India, leads the Vanchit Bahujan Aghadi and has served in both houses of the Indian Parliament

The Parliament of India (IAST: ) is the supreme legislative body of the Republic of India. It is a bicameral legislature composed of the president of India and two houses: the Rajya Sabha (Council of States) and the Lok Sabha (House of t ...

. Ambedkar's younger grandson, Anandraj Ambedkar

Anandraj Yashwant Ambedkar (born 2 June 1960) is an Indian social activist, engineer and politician from Maharashtra. He is head of the Republican Sena (tran: The "Republican Army"). He is the grandson of B. R. Ambedkar, the father of the In ...

leads the Republican Sena (tran: The "Republican Army").

A number of unfinished typescripts and handwritten drafts were found among Ambedkar's notes and papers and gradually made available. Among these were '' Waiting for a Visa'', which probably dates from 1935 to 1936 and is an autobiographical work, and the ''Untouchables, or the Children of India's Ghetto'', which refers to the census of 1951.

A memorial for Ambedkar was established in his Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders w ...

house at 26 Alipur Road. His birthdate is celebrated as a public holiday known as Ambedkar Jayanti

Ambedkar Jayanti or Bhim Jayanti is an annual festival observed on 14 April to commemorate the memory of B. R. Ambedkar, Indian politician and civil rights activist. It marks Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar's birthday who was born on 14 April 1891. Si ...

or Bhim Jayanti. He was posthumously awarded India's highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna

The Bharat Ratna (; ''Jewel of India'') is the highest Indian honours system, civilian award of the Republic of India. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is conferred in recognition of "exceptional service/performance of the highest orde ...

, in 1990.

On the anniversary of his birth and death, and on Dhamma Chakra Pravartan Din (14 October) at Nagpur, at least half a million people gather to pay homage to him at his memorial in Mumbai. Thousands of bookshops are set up, and books are sold. His message to his followers was "educate, agitate, organise!"

Legacy

Ambedkar's legacy as a socio-political reformer had a deep effect on modern India. In post-Independence India, his socio-political thought is respected across the political spectrum. His initiatives have influenced various spheres of life and transformed the way India today looks at socio-economic policies, education and affirmative action through socio-economic and legal incentives. His reputation as a scholar led to his appointment as free India's first law minister, and chairman of the committee for drafting the constitution. He passionately believed in individual freedom and criticised caste society. His accusations of

Ambedkar's legacy as a socio-political reformer had a deep effect on modern India. In post-Independence India, his socio-political thought is respected across the political spectrum. His initiatives have influenced various spheres of life and transformed the way India today looks at socio-economic policies, education and affirmative action through socio-economic and legal incentives. His reputation as a scholar led to his appointment as free India's first law minister, and chairman of the committee for drafting the constitution. He passionately believed in individual freedom and criticised caste society. His accusations of Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

as being the foundation of the caste system made him controversial and unpopular among Hindus. His conversion to Buddhism sparked a revival in interest in Buddhist philosophy in India and abroad.

Many public institutions are named in his honour, and the Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar International Airport

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar International Airport is an international airport serving the city of Nagpur, Maharashtra, India. The airport is located at Sonegaon, 8 km (5 mi) southwest of Nagpur. The airport covers an area of 1,355 acres ...

in Nagpur

Nagpur (pronunciation: aːɡpuːɾ is the third largest city and the winter capital of the Indian state of Maharashtra. It is the 13th largest city in India by population and according to an Oxford's Economics report, Nagpur is projected to ...

, otherwise known as Sonegaon Airport. Dr. B. R. Ambedkar National Institute of Technology, Jalandhar, Ambedkar University Delhi

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar University Delhi, formerly Bharat Ratna Dr. B. R. Ambedkar University Delhi and Ambedkar University Delhi, and simply AUD, is a state university established by the Government of the NCT of Delhi through an Act of the Delhi ...

is also named in his honour.

The Maharashtra government has acquired a house in London where Ambedkar lived during his days as a student in the 1920s. The house is expected to be converted into a museum-cum-memorial to Ambedkar.

Ambedkar was voted " the Greatest Indian" in 2012 by a poll organised by History TV18

History TV18 (formerly known as The History Channel) is a television channel in India. It broadcasts infotainment and documentry shows. It is owned by a joint venture between A+E Networks, owner of the American History channel, and TV18, an Ind ...

and CNN IBN

CNN-News18 (originally CNN-IBN) is an Indian English-language news television channel founded by Raghav Bahl based in Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India. It is currently co-owned by Network18 Group and Warner Bros. Discovery. CNN provides internati ...

, ahead of Patel and Nehru. Nearly 20 million votes were cast. Due to his role in economics, Narendra Jadhav

Narendra Damodar Jadhav (born 28 May 1953) is an Indian economist, educationist, public policy expert, professor and writer in English, Marathi and Hindi. He is an expert on Babasaheb Ambedkar.

Dr. Narendra Jadhav has completed (on 24 April 202 ...

, a notable Indian economist, has said that Ambedkar was "the highest educated Indian economist of all times." Amartya Sen

Amartya Kumar Sen (; born 3 November 1933) is an Indian economist and philosopher, who since 1972 has taught and worked in the United Kingdom and the United States. Sen has made contributions to welfare economics, social choice theory, economi ...

, said that Ambedkar is "father of my economics", and "he was highly controversial figure in his home country, though it was not the reality. His contribution in the field of economics is marvelous and will be remembered forever."

On 2 April 1967, an 3.66 metre (12 foot) tall bronze statue of Ambedkar was installed in the Parliament of India

The Parliament of India ( IAST: ) is the supreme legislative body of the Republic of India. It is a bicameral legislature composed of the president of India and two houses: the Rajya Sabha (Council of States) and the Lok Sabha (House of ...

. The statue, sculpted by B.V. Wagh, was unveiled by the then President of India, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan

Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (; 5 September 1888 – 17 April 1975), natively Radhakrishnayya, was an Indian philosopher and statesman. He served as the 2nd President of India from 1962 to 1967. He also 1st Vice President of India from 1952 ...

. On 12 April 1990, a portrait of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar is put in the Central Hall of Parliament House. The portrait of Ambedkar, painted by Zeba Amrohawi, was unveiled by the then Prime Minister of India, V. P. Singh

Vishwanath Pratap Singh (25 June 1931 – 27 November 2008), shortened to V. P. Singh, was an Indian politician who was the 7th Prime Minister of India from 1989 to 1990 and the 41st Raja Bahadur of Manda. He is India's only prime minister to ...

. Another portrait of Ambedkar is put in the Parliamentary Museum and archives of the Parliament House.

Ambedkar's legacy was not without criticism. Ambedkar has been criticised for his one-sided views on the issue of caste at the expense of cooperation with the larger nationalist movement. Ambedkar has been also criticised by some of his biographers over his neglect of organization-building.

Ambedkar's political philosophy has given rise to a large number of political parties, publications and workers' unions that remain active across India, especially in Maharashtra

Maharashtra (; , abbr. MH or Maha) is a state in the western peninsular region of India occupying a substantial portion of the Deccan Plateau. Maharashtra is the second-most populous state in India and the second-most populous country subdi ...

. His promotion of Buddhism has rejuvenated interest in Buddhist philosophy among sections of population in India. Mass conversion ceremonies have been organised by human rights activists in modern times, emulating Ambedkar's Nagpur ceremony of 1956. Some Indian Buddhists regard him as a Bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

, although he never claimed it himself. Outside India, during the late 1990s, some Hungarian Romani people

The Romani (also spelled Romany or Rromani , ), colloquially known as the Roma, are an Indo-Aryan peoples, Indo-Aryan ethnic group, traditionally nomadic Itinerant groups in Europe, itinerants. They live in Europe and Anatolia, and have Ro ...

drew parallels between their own situation and that of the downtrodden people in India. Inspired by Ambedkar, they started to convert to Buddhism.Views

Religion

Ambedkar said in 1935 that he was born a Hindu but would not die a Hindu. He viewed Hinduism as an "oppressive religion" and started to consider conversion to any other religion. In ''Annihilation of Caste'', Ambedkar claims that the only lasting way a true casteless society could be achieved is through destroying the belief of the sanctity of the ''Shastras'' and denying their authority. Ambedkar was critical of Hindu religious texts and epics and wrote a work titled ''Riddles in Hinduism

''Riddles in Hinduism'' is an English language book by the Indian anti-caste activist and politician B. R. Ambedkar, aimed at enlightening the Hindus, and challenging the '' sanatan'' (static) view of Hindu civilization propagated by European s ...

'' during 1954-1955. The work was published posthumously by combining individual chapter manuscripts and resulted in mass demonstrations and counter demonstrations.

Ambedkar viewed Christianity to be incapable of fighting injustices. He wrote that "It is an incontrovertible fact that Christianity was not enough to end the slavery of the Negroes in the United States. A civil war was necessary to give the Negro the freedom which was denied to him by the Christians."

Ambedkar criticized distinctions within Islam and described the religion as "a close corporation and the distinction that it makes between Muslims and non-Muslims is a very real, very positive and very alienating distinction".

He opposed conversions of depressed classes to convert to Islam or Christianity added that if they converted to Islam then "the danger of Muslim domination also becomes real" and if they converted to Christianity then it "will help to strengthen the hold of Britain on the country".

Initially, Ambedkar planned to convert to Sikhism but he rejected this idea after he discovered that British government would not guarantee the privileges accorded to the untouchables in reserved parliamentary seats.

On 16 October 1956, he converted to Buddhism just weeks before his death.

Aryan Invasion Theory

Ambedkar viewed theShudras

Shudra or ''Shoodra'' (Sanskrit: ') is one of the four ''Varna (Hinduism), varnas'' of the Hindu caste system and social order in ancient India. Various sources translate it into English as a caste, or alternatively as a social class. Theoret ...

as Aryan and adamantly rejected the Aryan invasion theory

The Indo-Aryan migrations were the migrations into the Indian subcontinent of Indo-Aryan peoples, an ethnolinguistic group that spoke Indo-Aryan languages, the predominant languages of today's North India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, S ...

, describing it as "so absurd that it ought to have been dead long ago" in his 1946 book ''Who Were the Shudras?

''Who Were the Shudras?'' is a history book published by Indian social reformer and polymath B. R. Ambedkar in 1946. The book discusses the origin of the Shudra Varna. Ambedkar dedicated the book to Jyotirao Phule (1827–1890).

Subject of the b ...

''.Bryant, Edwin (2001). ''The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture'', Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 50–51. Ambedkar viewed Shudras as originally being "part of the Kshatriya Varna in the Indo-Aryan society", but became socially degraded after they inflicted many tyrannies on Brahmins

Brahmin (; sa, ब्राह्मण, brāhmaṇa) is a varna as well as a caste within Hindu society. The Brahmins are designated as the priestly class as they serve as priests ( purohit, pandit, or pujari) and religious teachers (guru ...

.

According to Arvind Sharma, Ambedkar noticed certain flaws in the Aryan invasion theory that were later acknowledged by western scholarship. For example, scholars now acknowledge ''anās'' in Rig Veda

The ''Rigveda'' or ''Rig Veda'' ( ', from ' "praise" and ' "knowledge") is an ancient Indian collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns (''sūktas''). It is one of the four sacred canonical Hindu texts ('' śruti'') known as the Vedas. Only one ...

5.29.10 refers to speech rather than the shape of the nose

A nose is a protuberance in vertebrates that houses the nostrils, or nares, which receive and expel air for respiration alongside the mouth. Behind the nose are the olfactory mucosa and the sinuses. Behind the nasal cavity, air next passe ...

.Sharma, Arvind (2005), ''"Dr. B. R. Ambedkar on the Aryan Invasion and the Emergence of the Caste System in India"'', J Am Acad Relig (September 2005) 73 (3): 849. Ambedkar anticipated this modern view by stating:

Ambedkar disputed various hypotheses of the Aryan homeland being outside India, and concluded the Aryan homeland was India itself. According to Ambedkar, the Rig Veda says Aryans, Dāsa and Dasyus were competing religious groups, not different peoples.

Communism

Ambedkar's views onCommunism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

were expressed in two 1956 texts, “Buddha or Karl Marx” and “Buddhism and Communism". He accepted the Marxist theory

Marxist philosophy or Marxist theory are works in philosophy that are strongly influenced by Karl Marx's materialist approach to theory, or works written by Marxists. Marxist philosophy may be broadly divided into Western Marxism, which drew fro ...

that the privileged few's exploitation of the masses perpetuated poverty and its issues. However, he did not see this exploitation as purely economic, theorizing that the cultural aspects of exploitation are as bad or worse than economic exploitation. In addition, he did not see economic relationships as the only important aspect of human life. He also saw Communists as willing to resort to any means to achieve proletarian revolution

A proletarian revolution or proletariat revolution is a social revolution in which the working class attempts to overthrow the bourgeoisie and change the previous political system. Proletarian revolutions are generally advocated by socialists, ...

, including violence, while he himself saw democratic and peaceful measures as the best option for change. Ambedkar also opposed the Marxist idea of controlling all the means of production

The means of production is a term which describes land, labor and capital that can be used to produce products (such as goods or services); however, the term can also refer to anything that is used to produce products. It can also be used as a ...

and ending private ownership of property: seeing the latter measure as not able to fix the problems of society. In addition, rather than advocating for the eventual annihilation of the state as Marxism does, Ambedkar believed in a classless society, but also believed the state would exist as long as society and that it should be active in development. But in the 1950s, in an interview he gave to BBC, he accepted that the current liberal democratic system will collapse and the alternative, as he thinks, "is some kind of communism".

In popular culture

Several films, plays, and other works have been based on the life and thoughts of Ambedkar. * Indian director Jabbar Patel made a documentary titled ''Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar'' in 1991; he followed this with a full-length feature film ''Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (14 April 1891 – 6 December 1956) was an Indian jurist, economist, social reformer and political leader who headed the committee drafting the Constitution of India from the Constituent Assembly debates, served ...

'' in 2000 with Mammootty

Muhammad Kutty Panaparambil Ismail (; born 7 September 1951), known mononymously by the hypocorism Mammootty (), is an Indian actor and film producer who works predominantly in Malayalam films. He has also appeared in Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, H ...

in the lead role. This biopic was sponsored by the National Film Development Corporation of India

The National Film Development Corporation of India (NFDC) based in Mumbai is the central agency established in 1975, to encourage high quality Indian cinema. It functions in areas of film financing, production and distribution and under Ministr ...

and the government's Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. The film was released after a long and controversial gestation.

* Other Indian films on Ambedkar include: ''Balaka Ambedkar'' (1991) by Basavaraj Kestur, ''Dr. Ambedkar'' (1992) by Bharath Parepalli, and ''Yugpurush Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar'' (1993).

* David Blundell, professor of anthropology at UCLA

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a teachers college then known as the southern branch of the California ...

and historical ethnographer, has established ''Arising Light'' – a series of films and events that are intended to stimulate interest and knowledge about the social conditions in India and the life of Ambedkar. In '' Samvidhaan'', a TV mini-series on the making of the Constitution of India directed by Shyam Benegal

Shyam Benegal (born 14 December 1934) is an Indian film director, screenwriter and documentary filmmaker. Often regarded as the pioneer of parallel cinema, he is widely considered as one of the greatest filmmakers post 1970s. He has received ...

, the pivotal role of B. R. Ambedkar was played by Sachin Khedekar. The play ''Ambedkar Aur Gandhi'', directed by Arvind Gaur

Arvind Gaur is an Indian theatre director known for innovative, socially and politically relevant plays in India. Gaur's plays are contemporary and thought-provoking, connecting intimate personal spheres of existence to larger social politi ...

and written by Rajesh Kumar, tracks the two prominent personalities of its title.

* '' Bhimayana: Experiences of Untouchability'' is a graphic biography of Ambedkar created by Pardhan-Gond artists Durgabai Vyam

Durga Bai Vyam (born in 1973) is an Indian artist. She is one of the foremost female artists based in Bhopal working in the Gond tradition of Tribal Art. Most of Durga's work is rooted in her birthplace, Barbaspur, a village in the Mandla distr ...

and Subhash Vyam, and writers Srividya Natarajan and S. Anand

S. Anand is an Indian author, publisher and journalist. He, along with D. Ravikumar, founded the publishing house Navayana in 2003, which is "India’s first and only publishing house to focus on the issue of caste from an anticaste perspective." ...

. The book depicts the experiences of untouchability faced by Ambedkar from childhood to adulthood. CNN named it one of the top 5 political comic books.

* The Ambedkar Memorial

Ambedkar Memorial Park, formally known as Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar Samajik Parivartan Prateek Sthal, is a public park and memorial in Gomti Nagar, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India. The memorial is dedicated to B. R. Ambedkar, the 20th century Indian p ...

at Lucknow

Lucknow (, ) is the capital and the largest city of the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh and it is also the second largest urban agglomeration in Uttar Pradesh. Lucknow is the administrative headquarters of the eponymous district and divis ...

is dedicated in his memory. The chaitya

A chaitya, chaitya hall, chaitya-griha, (Sanskrit:''Caitya''; Pāli: ''Cetiya'') refers to a shrine, sanctuary, temple or prayer hall in Indian religions. The term is most common in Buddhism, where it refers to a space with a stupa and a rounded ...

consists of monuments showing his biography.

* Jai Bhim slogan was given by the Dalit community in Delhi