Aterian on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Aterian is a

The technological character of the Aterian has been debated for almost a century, but has until recently eluded definition. The problems defining the industry have related to its research history and the fact that a number of similarities have been observed between the Aterian and other North African stone tool industries of the same date. Levallois reduction is widespread across the whole of North Africa throughout the Middle Stone Age, and scrapers and denticulates are ubiquitous. Bifacial foliates moreover represent a huge taxonomic category and the form and dimension of such foliates associated with tanged tools is extremely varied. There is also a significant variation of tanged tools themselves, with various forms representing both different tool types (e.g., knives, scrapers, points) and the degree tool resharpening.

More recently, a large-scale study of North African stone tool assemblages, including Aterian assemblages, indicated that the traditional concept of stone tool industries is problematic in the North African Middle Stone Age. Although the term Aterian defines Middle Stone Age assemblages from North Africa with tanged tools, the concept of an Aterian industry obfuscates other similarities between tanged tool assemblages and other non-Aterian North African assemblages of the same date. For example, bifacial leaf points are found widely across North Africa in assemblages that lack tanged tools and Levallois flakes and cores are near ubiquitous. Instead of elaborating discrete industries, the findings of the comparative study suggest that North Africa during the Last Interglacial comprised a network of related technologies whose similarities and differences correlated with geographical distance and the palaeohydrology of a

The technological character of the Aterian has been debated for almost a century, but has until recently eluded definition. The problems defining the industry have related to its research history and the fact that a number of similarities have been observed between the Aterian and other North African stone tool industries of the same date. Levallois reduction is widespread across the whole of North Africa throughout the Middle Stone Age, and scrapers and denticulates are ubiquitous. Bifacial foliates moreover represent a huge taxonomic category and the form and dimension of such foliates associated with tanged tools is extremely varied. There is also a significant variation of tanged tools themselves, with various forms representing both different tool types (e.g., knives, scrapers, points) and the degree tool resharpening.

More recently, a large-scale study of North African stone tool assemblages, including Aterian assemblages, indicated that the traditional concept of stone tool industries is problematic in the North African Middle Stone Age. Although the term Aterian defines Middle Stone Age assemblages from North Africa with tanged tools, the concept of an Aterian industry obfuscates other similarities between tanged tool assemblages and other non-Aterian North African assemblages of the same date. For example, bifacial leaf points are found widely across North Africa in assemblages that lack tanged tools and Levallois flakes and cores are near ubiquitous. Instead of elaborating discrete industries, the findings of the comparative study suggest that North Africa during the Last Interglacial comprised a network of related technologies whose similarities and differences correlated with geographical distance and the palaeohydrology of a

The Aterian is associated with early ''Homo sapiens'' at a number of sites in Morocco. While the

The Aterian is associated with early ''Homo sapiens'' at a number of sites in Morocco. While the

Middle Stone Age

The Middle Stone Age (or MSA) was a period of African prehistory between the Early Stone Age and the Late Stone Age. It is generally considered to have begun around 280,000 years ago and ended around 50–25,000 years ago. The beginnings of ...

(or Middle Palaeolithic

The Middle Paleolithic (or Middle Palaeolithic) is the second subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age as it is understood in Europe, Africa and Asia. The term Middle Stone Age is used as an equivalent or a synonym for the Middle Pale ...

) stone tool industry

Industry may refer to:

Economics

* Industry (economics), a generally categorized branch of economic activity

* Industry (manufacturing), a specific branch of economic activity, typically in factories with machinery

* The wider industrial sector ...

centered in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, from Mauritania

Mauritania (; ar, موريتانيا, ', french: Mauritanie; Berber: ''Agawej'' or ''Cengit''; Pulaar: ''Moritani''; Wolof: ''Gànnaar''; Soninke:), officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania ( ar, الجمهورية الإسلامية ...

to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, but also possibly found in Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

and the Thar Desert

The Thar Desert, also known as the Great Indian Desert, is an arid region in the north-western part of the Subcontinent that covers an area of and forms a natural boundary between India and Pakistan. It is the world's 20th-largest desert, ...

. The earliest Aterian dates to c. 150,000 years ago, at the site of Ifri n'Ammar in Morocco. However, most of the early dates cluster around the beginning of the Last Interglacial, around 150,000 to 130,000 years ago, when the environment of North Africa began to ameliorate. The Aterian disappeared around 20,000 years ago.

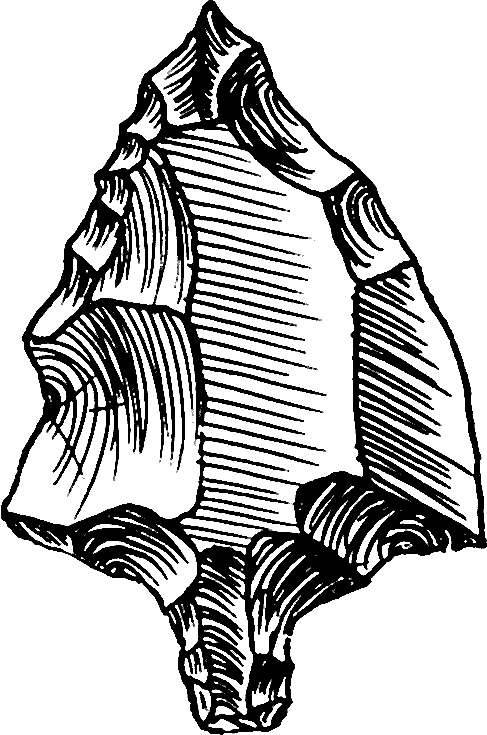

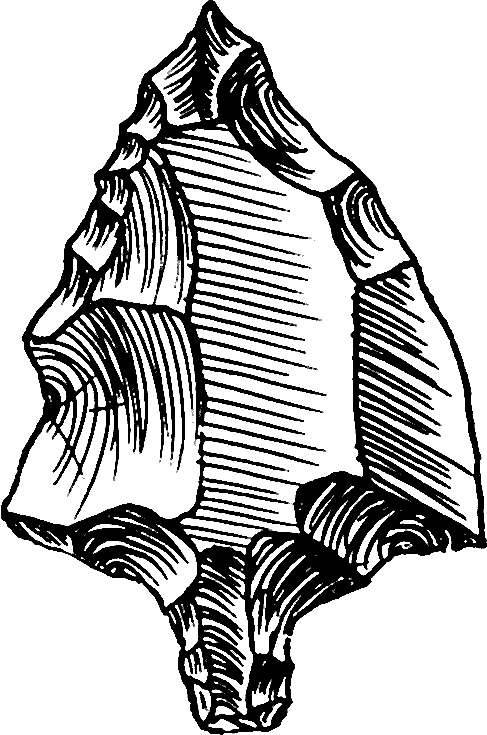

The Aterian is primarily distinguished through the presence of tanged or pedunculated tools, and is named after the type site of Bir el Ater

Bir el Ater ( ar, بئر العاتر) is a city located in far eastern Algeria. It is located towards the border with Tunisia, around 87 kilometers south of Tebessa and just beyond the Sahara. The town has a population of approximately 80,000 inh ...

, south of Tébessa

Tébessa or Tebessa ( ar, تبسة ''Tibissa'', ''Tbessa'' or ''Tibesti''), the classical Theveste, is the capital city of Tébessa Province region of northeastern Algeria. It hosts several historical landmarks, the most important one being the ...

. Bifacially-worked, leaf-shaped tools are also a common artefact type in Aterian assemblages, and so are racloirs and Levallois flakes and cores. Items of personal adornment (pierced and ochred Nassarius

''Nassarius'', common name nassa mud snails (USA) or dog whelks (UK), is a genus of minute to medium-sized sea snails, marine gastropod molluscs in the family Nassariidae.Bouchet, P.; Gofas, S. (2010). Nassarius Duméril, 1806. In: Bouchet, P.; ...

shell beads) are known from at least one Aterian site, with an age of 82,000 years. The Aterian is one of the oldest examples of regional technological diversification, evidencing significant differentiation to older stone tool industries in the area, frequently described as Mousterian

The Mousterian (or Mode III) is an archaeological industry of stone tools, associated primarily with the Neanderthals in Europe, and to the earliest anatomically modern humans in North Africa and West Asia. The Mousterian largely defines the l ...

. The appropriateness of the term Mousterian is contested in a North African context, however.

Description

The technological character of the Aterian has been debated for almost a century, but has until recently eluded definition. The problems defining the industry have related to its research history and the fact that a number of similarities have been observed between the Aterian and other North African stone tool industries of the same date. Levallois reduction is widespread across the whole of North Africa throughout the Middle Stone Age, and scrapers and denticulates are ubiquitous. Bifacial foliates moreover represent a huge taxonomic category and the form and dimension of such foliates associated with tanged tools is extremely varied. There is also a significant variation of tanged tools themselves, with various forms representing both different tool types (e.g., knives, scrapers, points) and the degree tool resharpening.

More recently, a large-scale study of North African stone tool assemblages, including Aterian assemblages, indicated that the traditional concept of stone tool industries is problematic in the North African Middle Stone Age. Although the term Aterian defines Middle Stone Age assemblages from North Africa with tanged tools, the concept of an Aterian industry obfuscates other similarities between tanged tool assemblages and other non-Aterian North African assemblages of the same date. For example, bifacial leaf points are found widely across North Africa in assemblages that lack tanged tools and Levallois flakes and cores are near ubiquitous. Instead of elaborating discrete industries, the findings of the comparative study suggest that North Africa during the Last Interglacial comprised a network of related technologies whose similarities and differences correlated with geographical distance and the palaeohydrology of a

The technological character of the Aterian has been debated for almost a century, but has until recently eluded definition. The problems defining the industry have related to its research history and the fact that a number of similarities have been observed between the Aterian and other North African stone tool industries of the same date. Levallois reduction is widespread across the whole of North Africa throughout the Middle Stone Age, and scrapers and denticulates are ubiquitous. Bifacial foliates moreover represent a huge taxonomic category and the form and dimension of such foliates associated with tanged tools is extremely varied. There is also a significant variation of tanged tools themselves, with various forms representing both different tool types (e.g., knives, scrapers, points) and the degree tool resharpening.

More recently, a large-scale study of North African stone tool assemblages, including Aterian assemblages, indicated that the traditional concept of stone tool industries is problematic in the North African Middle Stone Age. Although the term Aterian defines Middle Stone Age assemblages from North Africa with tanged tools, the concept of an Aterian industry obfuscates other similarities between tanged tool assemblages and other non-Aterian North African assemblages of the same date. For example, bifacial leaf points are found widely across North Africa in assemblages that lack tanged tools and Levallois flakes and cores are near ubiquitous. Instead of elaborating discrete industries, the findings of the comparative study suggest that North Africa during the Last Interglacial comprised a network of related technologies whose similarities and differences correlated with geographical distance and the palaeohydrology of a Green Sahara

The African humid period (AHP) (also known by other names) is a climate period in Africa during the late Pleistocene and Holocene geologic epochs, when northern Africa was wetter than today. The covering of much of the Sahara desert by grasses, ...

. Assemblages with tanged tools may therefore reflect particular activities involving the use of such tool types, and may not necessarily reflect a substantively different archaeological culture to others from the same period in North Africa. The findings are significant because they suggest that current archaeological nomenclatures do not reflect the true variability of the archaeological record of North Africa during the Middle Stone Age from the Last Interglacial, and hints at how early modern humans dispersed into previously uninhabitable environments. This notwithstanding, the term still usefully denotes the presence of tanged tools in North African Middle Stone Age assemblages.

Tanged tools persisted in North Africa until around 20,000 years ago, with the youngest sites located in Northwest Africa. By this time, the Aterian lithic industry had long ceased to exist in the rest of North Africa due to the onset of the Ice Age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gre ...

, which in North Africa, resulted in hyperarid conditions. Assemblages with tanged tools, 'the Aterian', therefore have a significant temporal and spatial range. However, the exact geographical distribution of this lithic industry is uncertain. The Aterian's spatial range is thought to have existed in North Africa up to the Nile Valley Possible Aterian lithic tools have also been discovered in Middle Paleolithic deposits in Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

and the Thar Desert

The Thar Desert, also known as the Great Indian Desert, is an arid region in the north-western part of the Subcontinent that covers an area of and forms a natural boundary between India and Pakistan. It is the world's 20th-largest desert, ...

.

Most engraved

Engraving is the practice of incising a design onto a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or glass are engraved, or may provide an i ...

Bubaline rock art appear in the northern region of Tassili, at Wadi Djerat. Levallois instruments in the area may indicate that Bubaline rock art was developed by Aterians.

In the Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

, Aterians camped near lakes, rivers, and springs, and engaged in the activity of hunting (e.g., antelope, buffalo, elephant, rhinoceros) and some gathering. As a result of a hyper-aridification event of Saharan Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, which occurred around the time of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

's Würm glaciation

The Würm glaciation or Würm stage (german: Würm-Kaltzeit or ''Würm-Glazial'', colloquially often also ''Würmeiszeit'' or ''Würmzeit''; cf. ice age), usually referred to in the literature as the Würm (often spelled "Wurm"), was the last g ...

event, Aterian hunter-gatherers may have migrated into areas of tropical Africa and coastal Africa. More specifically, amid aridification in MIS 5

Marine Isotope Stage 5 or MIS 5 is a marine isotope stage in the geologic temperature record, between 130,000 and 80,000 years ago. Sub-stage MIS 5e, called the Eemian or Ipswichian, covers the last major interglacial period before the Holocene, w ...

and regional change of climate in MIS 4, in the Sahara and the Sahel

The Sahel (; ar, ساحل ' , "coast, shore") is a region in North Africa. It is defined as the ecoclimatic and biogeographic realm of transition between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian savanna to the south. Having a hot semi-arid cli ...

, Aterians may have migrated southward into West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

(e.g., Baie du Levrier, Mauritania

Mauritania (; ar, موريتانيا, ', french: Mauritanie; Berber: ''Agawej'' or ''Cengit''; Pulaar: ''Moritani''; Wolof: ''Gànnaar''; Soninke:), officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania ( ar, الجمهورية الإسلامية ...

; Tiemassas, Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 ...

; Lower Senegal River

,french: Fleuve Sénégal)

, name_etymology =

, image = Senegal River Saint Louis.jpg

, image_size =

, image_caption = Fishermen on the bank of the Senegal River estuary at the outskirts of Saint-Louis, Senega ...

Valley).

Associated behaviour

The Aterian is associated with early ''Homo sapiens'' at a number of sites in Morocco. While the

The Aterian is associated with early ''Homo sapiens'' at a number of sites in Morocco. While the Jebel Irhoud

Jebel Irhoud or Adrar n Ighoud ( zgh, ⴰⴷⵔⴰⵔ ⵏ ⵉⵖⵓⴷ, Adrar n Iɣud; ar, جبل إيغود, žbəl iġud), is an archaeological site located just north of the locality known as Tlet Ighoud, approximately south-east of the cit ...

specimens were originally noted to have been similar to later Aterian and some Iberomaurusian

The Iberomaurusian is a backed bladelet lithic industry found near the coasts of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. It is also known from a single major site in Libya, the Haua Fteah, where the industry is locally known as the Eastern Oranian.The " ...

specimens, further examinations revealed that the Jebel Irhoud specimens are similar to them in some respects but differ in that the Jebel Irhoud specimens have a continuous supraorbital torus while the Aterian and Iberomaurasian specimens have a discontinuous supraorbital torus or in some cases, none at all, and from this, it was concluded that the Jebel Irhoud specimens represent archaic ''Homo sapiens'' while the Aterian and Iberomaurusian specimens represent anatomically modern ''Homo sapiens''. The 'Aterian' fossils also display morphological similarities with the early out of Africa

''Out of Africa'' is a memoir by the Danish author Karen Blixen. The book, first published in 1937, recounts events of the seventeen years when Blixen made her home in Kenya, then called British East Africa. The book is a lyrical meditation on ...

modern humans found at Skhul

Es-Skhul (es-Skhūl, ar, السخول; meaning ''kid'', ''young goat'') or the Skhul Cave is a prehistoric cave site situated about south of the city of Haifa, Israel, and about from the Mediterranean Sea.

Together with the nearby sites of Ta ...

and Qafzeh in the Levant, and they are broadly contemporary to them. Apart from producing a highly distinctive and sophisticated stone tool technology, these early North African populations also seem to have engaged with symbolically constituted material culture, creating what are amongst the earliest African examples of personal ornamentation. Such examples of shell 'beads' have been found far inland, suggesting the presence of long distance social networks.

Studies of the variation and distribution of the Aterian have also now suggested that associated populations lived in subdivided populations, perhaps living most of their lives in relative isolation and aggregating at particular times to reinforce social ties. Such a subdivided population structure has also been inferred from the pattern of variation observed in early African fossils of ''Homo sapiens''.

Associated faunal studies suggest that the people making the Aterian exploited coastal resources as well as engaging in hunting. As the points are small and lightweight, it is likely that they were not hand-delivered but instead thrown. There is no evidence that a spear thrower was used, but the points have characteristics similar to atlatl dart points. It has so far been difficult to estimate whether Aterian populations further inland were exploiting freshwater resources as well. Studies have suggested that hafting

Hafting is a process by which an artifact, often bone, stone, or metal is attached to a ''haft'' (handle or strap). This makes the artifact more useful by allowing it to be shot (arrow), thrown by hand (spear), or used with more effective levera ...

was widespread, perhaps to maintain flexibility in the face of strongly seasonal environment with a pronounced dry season. Scrapers, knives and points all seem to have been hafted, suggesting a wide range of activities were facilitated by technological advances. It is probable that plant resources were also exploited. Although there is no direct evidence from the Aterian yet, plant processing is evidenced in North Africa from as much as 182,000 years ago. In 2012, a 90,000-year-old bone knife was discovered in the Dar es-Soltan I cave, which is basically made of a cattle-sized animal's rib.

Locations

North Africa

*Ifri n'Ammar (Morocco) *Contrebandiers (Morocco) * Taforalt (Morocco) *Rhafas (Morocco) *Dar es Soltan I (Morocco) *El Mnasra (Morocco) *Kharga Oasis

The Kharga Oasis (Arabic: , ) ; Coptic: ( "Oasis of Hib", "Oasis of Psoi") is the southernmost of Egypt's five western oases. It is located in the Western Desert, about 200 km (125 miles) to the west of the Nile valley. "Kharga" or ...

(Egypt)

*Uan Tabu (Libya)

*Oued el Akarit(Tunisia)

* Adrar Bous (Niger)

References

{{Commons category, Aterian Middle Stone Age cultures History of the Sahara History of North Africa Archaeological cultures in Egypt Archaeological cultures in Morocco