Arthur Garfield Hays on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Arthur Garfield Hays (December 12, 1881 – December 14, 1954) was an American

Arthur Garfield Hays was born on December 12, 1881, in

Arthur Garfield Hays was born on December 12, 1881, in

In 1905, Hays formed a law firm with two former classmates. He and his partners gained prominence during

In 1905, Hays formed a law firm with two former classmates. He and his partners gained prominence during  Hays took part in numerous notable cases, including the Sweet segregation case in Detroit as well as the Scopes trial (often called the "monkey trial") in 1925, in which a school teacher in Tennessee was tried for teaching evolution;

the ''

Hays took part in numerous notable cases, including the Sweet segregation case in Detroit as well as the Scopes trial (often called the "monkey trial") in 1925, in which a school teacher in Tennessee was tried for teaching evolution;

the ''

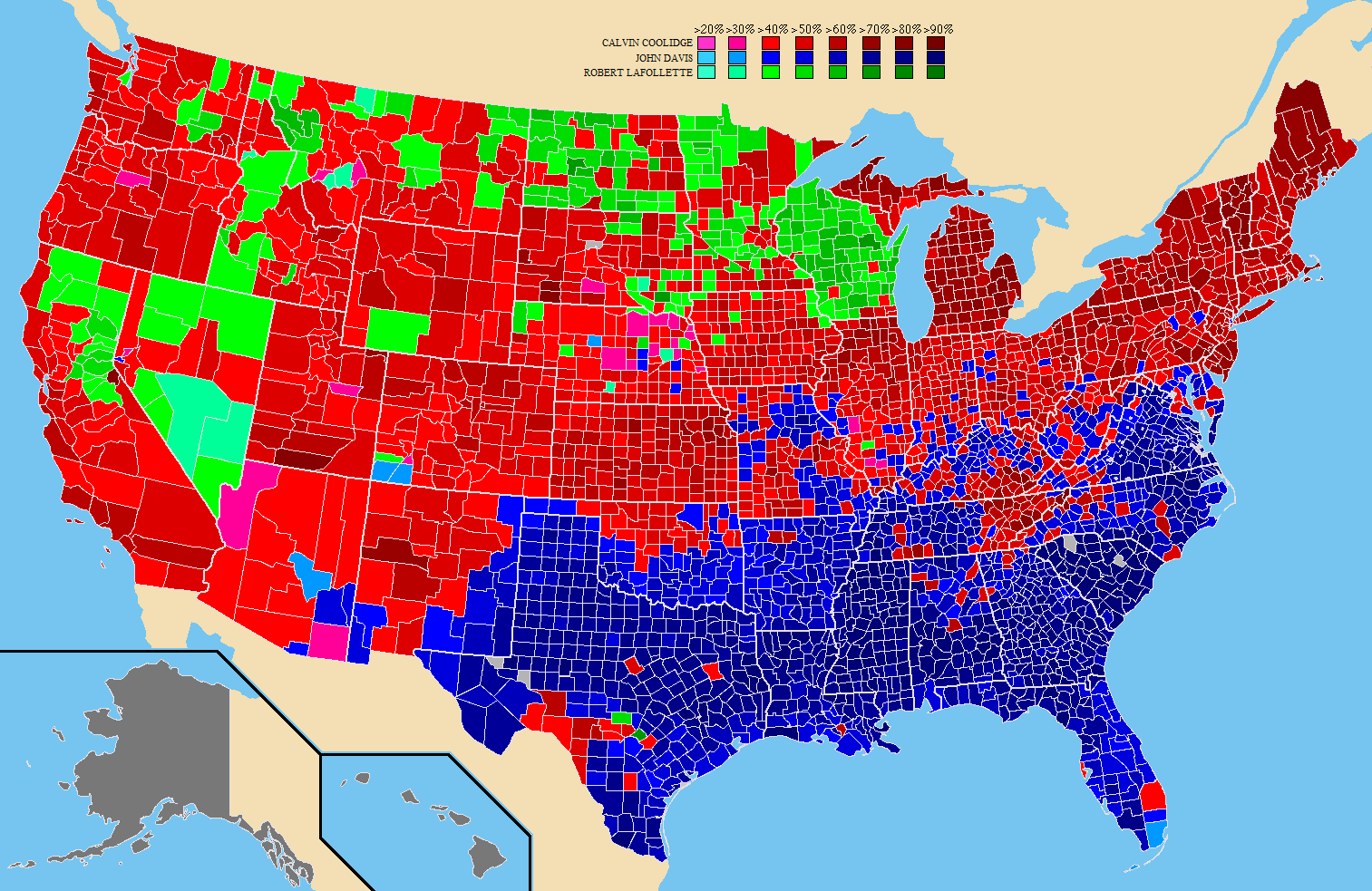

In 1924, Hays served as New York State chairman of the second

In 1924, Hays served as New York State chairman of the second

In 1951, Hays appeared on ''

In 1951, Hays appeared on ''

Arthur Garfield Hays Papers

held b

Princeton University Library Special Collections

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Hays, Arthur Garfield 1881 births 1954 deaths American activists American autobiographers 20th-century American lawyers American legal writers Columbia Law School alumni American Civil Liberties Union people Columbia College (New York) alumni

lawyer

A lawyer is a person who practices law. The role of a lawyer varies greatly across different legal jurisdictions. A lawyer can be classified as an advocate, attorney, barrister, canon lawyer, civil law notary, counsel, counselor, solic ...

and champion of civil liberties issues, best known as a co-founder and general counsel of the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". T ...

and for participating in notable cases including the Sacco and Vanzetti

Nicola Sacco (; April 22, 1891 – August 23, 1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (; June 11, 1888 – August 23, 1927) were Italian immigrant anarchists who were controversially accused of murdering Alessandro Berardelli and Frederick Parmenter, a ...

trial. He was a member of the Committee of 48 and a contributor to ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' is an American magazine of commentary on politics, contemporary culture, and the arts. Founded in 1914 by several leaders of the progressive movement, it attempted to find a balance between "a liberalism centered in hum ...

''. In 1937, he headed an independent investigation of an incident in which 19 people were killed and more than 200 wounded in Ponce, Puerto Rico

Ponce (, , , ) is both a city and a municipality on the southern coast of Puerto Rico. The city is the seat of the municipal government.

Ponce, Puerto Rico's most populated city outside the San Juan metropolitan area, was founded on 12 August 1 ...

, when police fired at them. His commission concluded the police had behaved as a mob and committed a massacre.

Background

Arthur Garfield Hays was born on December 12, 1881, in

Arthur Garfield Hays was born on December 12, 1881, in Rochester, New York

Rochester () is a City (New York), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, the county seat, seat of Monroe County, New York, Monroe County, and the fourth-most populous in the state after New York City, Buffalo, New York, Buffalo, ...

. His father and mother, both of German Jewish descent, belonged to prosperous families in the clothing manufacturing industry. In 1902, he graduated from Columbia College, where he was one of the early members of the Pi Lambda Phi

Pi Lambda Phi (), commonly known as Pi Lam, is a social fraternity with 145 chapters (44 active chapters/colonies). The fraternity was founded in 1895 at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Pi Lambda Phi is headlined by prestigious chapte ...

fraternity. In 1905, he received an LLB from Columbia Law School

Columbia Law School (Columbia Law or CLS) is the law school of Columbia University, a private Ivy League university in New York City. Columbia Law is widely regarded as one of the most prestigious law schools in the world and has always ranked i ...

and was admitted to the New York bar.

Career

In 1905, Hays formed a law firm with two former classmates. He and his partners gained prominence during

In 1905, Hays formed a law firm with two former classmates. He and his partners gained prominence during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

representing interests of ethnic Germans in the US who were discriminated against because Germany was an enemy of the Allies during the war. In 1914-1915, he practiced law in London.

Hays was active in civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may ...

issues. In 1920 (or as early as 1912), was hired as general counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". T ...

. From this point, his career had two tracks: he vigorously defended the individual liberty of victims of discriminatory laws, and he also kept private work. He became a wealthy lawyer who represented the interests of power and fame (his more prominent clients ranged from Wall Street

Wall Street is an eight-block-long street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs between Broadway in the west to South Street and the East River in the east. The term "Wall Street" has become a metonym for t ...

brokers and best-selling authors to notorious gamblers and the Dionne quintuplets

The Dionne quintuplets (; born May 28, 1934) are the first quintuplets known to have survived their infancy. The identical girls were born just outside Callander, Ontario, near the village of Corbeil. All five survived to adulthood.

The Dionn ...

).

Hays took part in numerous notable cases, including the Sweet segregation case in Detroit as well as the Scopes trial (often called the "monkey trial") in 1925, in which a school teacher in Tennessee was tried for teaching evolution;

the ''

Hays took part in numerous notable cases, including the Sweet segregation case in Detroit as well as the Scopes trial (often called the "monkey trial") in 1925, in which a school teacher in Tennessee was tried for teaching evolution;

the ''American Mercury

''The American Mercury'' was an American magazine published from 1924Staff (Dec. 31, 1923)"Bichloride of Mercury."''Time''. to 1981. It was founded as the brainchild of H. L. Mencken and drama critic George Jean Nathan. The magazine featured wri ...

'' censorship case (1926); the Sacco and Vanzetti

Nicola Sacco (; April 22, 1891 – August 23, 1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (; June 11, 1888 – August 23, 1927) were Italian immigrant anarchists who were controversially accused of murdering Alessandro Berardelli and Frederick Parmenter, a ...

case, in which two Italian anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

s in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

were convicted and executed in 1927 for a murder they denied committing; and the Scottsboro case, in which eight black men from Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

were convicted and sentenced to death in 1931 for allegedly attacking two white women. Hays attended the Reichstag trial in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

on behalf of Georgi Dimitrov

Georgi Dimitrov Mihaylov (; bg, Гео̀рги Димитро̀в Миха̀йлов), also known as Georgiy Mihaylovich Dimitrov (russian: Гео́ргий Миха́йлович Дими́тров; 18 June 1882 – 2 July 1949), was a Bulgarian ...

, a Bulgarian Communist accused by the Nazis in 1933 of burning the Reichstag.

Hays also defended labor. He defended coal miners in disputes in Pennsylvania and West Virginia (1922-1935), including the Anthracite Coal Strike of 1922

Anthracite, also known as hard coal, and black coal, is a hard, compact variety of coal that has a submetallic luster. It has the highest carbon content, the fewest impurities, and the highest energy density of all types of coal and is the hig ...

. He defended right-to-strike cases against Jersey City

Jersey City is the second-most populous city in the U.S. state of New Jersey, after Newark.CPGB

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was the largest communist organisation in Britain and was founded in 1920 through a merger of several smaller Marxist groups. Many miners joined the CPGB in the 1926 general strike. In 1930, the CPGB ...

member) John Strachey against deportation. He led the plaintiff in '' Emerson Jennings vs. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania'' conspiracy case. He represented the Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a millenarian restorationist Christian denomination with nontrinitarian beliefs distinct from mainstream Christianity. The group reports a worldwide membership of approximately 8.7 million adherents involved in ...

. He argued for the right not to salute the American flag.

In 1937, Hays was appointed to lead an independent investigation with a group (called the "Hays Commission") to study an incident in which 18 people were killed and more than 200 wounded in Ponce, Puerto Rico

Ponce (, , , ) is both a city and a municipality on the southern coast of Puerto Rico. The city is the seat of the municipal government.

Ponce, Puerto Rico's most populated city outside the San Juan metropolitan area, was founded on 12 August 1 ...

when police opened fire on them. They had gathered for a parade for which the permits had been withdrawn at the last minute. His commission concluded the police had behaved as a mob and committed a massacre.

From 1939 to 1943, he represented sociologist Jerome Davis in a libel suit filed against Curtis Publishing, publishers of the ''Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine, currently published six times a year. It was issued weekly under this title from 1897 until 1963, then every two weeks until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely c ...

'' magazine and its reporter Benjamin Stolberg.

Film censorship case over ''Whirlpool of Desire''

From theIMDB

IMDb (an abbreviation of Internet Movie Database) is an online database of information related to films, television series, home videos, video games, and streaming content online – including cast, production crew and personal biographies, ...

entry for '' Remous'' (France, 1935) directed by Edmond T. Greville:

Albany, New York - Monday, January 23, 1939: "The French film ''Remous'' was shown Friday anuary 20to five judges of the New York State Appellate Division in proceedings in the attempt by Arthur Mayer

Arthur L. Mayer (March 28, 1886, Demopolis, Alabama - April 14, 1981, New York City) was an American film producer and film distributor who worked with Joseph Burstyn in distributing films directed by Roberto Rossellini and other famous European ...

and Joseph Burstyn

Joseph Burstyn (born Jossel Lejba Bursztyn; December 15, 1899 – November 29, 1953) was a Polish-American film distributor who specialized in the commercial release of foreign-language and American independent film productions.

Life and career

B ...

to get a license to screen it in New York State. The picture has twice been denied a license, first in August 1936, when it was rejected as being "indecent," "immoral," and tending to "corrupt morals." It was again rejected in November 1937. In March 1938, it was screened for the New York Board of Regents, which on April 14 disapproved application for a license. Hays, counsel for Mayer and Burstyn at yesterday's proceedings, ridiculed the objections of Irwin Esmond and the Regents to certain scenes, pointing out that the film was French and would appeal only to an educated audience. Counsel for the Regents based his plea on the film's theme of sex frustration, arguing that it would be unwise public policy to show it to all classes of people.

In November 1939, Mayer and Burstyn released the film in the US as ''Whirlpool of Desire''. Film censorship in the United States

Film censorship in the United States was a frequent feature of the industry almost from the beginning of the U.S. motion picture industry until the end of strong self-regulation in 1966. Court rulings in the 1950s and 1960s severely constrained g ...

was not overturned until the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

case, the ''Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson

''Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson'', 343 U.S. 495 (1952), also referred to as the ''Miracle Decision'', was a landmark decision by the United States Supreme Court that largely marked the decline of motion picture censorship in the United States. ...

'' (the "Miracle Decision") in 1952.

Politics

Progressive Party

Progressive Party Progressive Party may refer to:

Active parties

* Progressive Party, Brazil

* Progressive Party (Chile)

* Progressive Party of Working People, Cyprus

* Dominica Progressive Party

* Progressive Party (Iceland)

* Progressive Party (Sardinia), Ita ...

.

Anti-McCarthyism

In 1951, Hays appeared on ''

In 1951, Hays appeared on ''Longines Chronoscope

''Longines Chronoscope'', also titled ''Chronoscope'', is an American TV series, sponsored by Longines watches, that ran on CBS Television from 1951–1955. The series aired Monday nights at 11 p.m. ET to 11:15 p.m., and expanded to Mondays, ...

'' to provide comments on the political activities of US Senator Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957. Beginning in 1950, McCarthy became the most visi ...

. Hays stated: I think he is the most dangerous man in the United States. I think he Senator McCarthy is more dangerous to freedom in the United States than all the Communists we have in this country... I think he's dangerous, because without evidence, he is smearing a lot of respected and highly decent people.His greatest criticism regarded McCarthy's methods. He defended

Owen Lattimore

Owen Lattimore (July 29, 1900 – May 31, 1989) was an American Orientalist and writer. He was an influential scholar of China and Central Asia, especially Mongolia. Although he never earned a college degree, in the 1930s he was editor of ''Pacif ...

and Philip Jessup

Philip Caryl Jessup (February 5, 1897 – January 31, 1986), also Philip C. Jessup, was a 20th-century American diplomat, scholar, and jurist notable for his accomplishments in the field of international law.

Early life and education

Philip ...

but conceded that there were "a few" communists in the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government responsible for the country's fore ...

and cited Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss (November 11, 1904 – November 15, 1996) was an American government official accused in 1948 of having spied for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. Statutes of limitations had expired for espionage, but he was convicted of perjury in con ...

.

Personal life and death

Hays married Blanche Marks in 1908; they divorced in 1924, after having a daughter Lora. He married Aline Davis Fleisher in 1924, and they had a daughter Jane. Aline Fleisher Hays died in 1944. Jane married the prominent American lawyer . Hays died of aheart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which may tr ...

on December 14, 1954 at the age of 73.

Legacy

In 1958, New York University established the Arthur Garfield Hays Civil Liberties Program at its School of Law. Princeton University houses the Arthur Garfield Hays Papers. Hays was a partner of Hays, St John & Buckley, also known as Hays, St. John, Abramson & Heilbron, of which Osmond K. Fraenkel was later a member.Works

Hays wrote numerous books and articles. As a gifted writer and eloquent debater, he added his perspective to virtually every individual rights issue of his day. He wrote several books and essays about civil liberties issues. Hisautobiography

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life.

It is a form of biography.

Definition

The word "autobiography" was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English peri ...

, entitled ''City Lawyer: The Autobiography of a Law Practice'' (1942), provides a colorful account of his more noteworthy cases. His articles and book reviews demonstrate his wide-ranging knowledge of a nation and a world experiencing dramatic change in the way individual rights were perceived.

* ''Let Freedom Ring'' (1928, rev. ed. 1937)

* ''Trial by Prejudice'' (1937)

* ''Democracy Works'' (1939)

* ''City Lawyer: The Autobiography of a Law Practice'' (1942)

References

External links

Arthur Garfield Hays Papers

held b

Princeton University Library Special Collections

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Hays, Arthur Garfield 1881 births 1954 deaths American activists American autobiographers 20th-century American lawyers American legal writers Columbia Law School alumni American Civil Liberties Union people Columbia College (New York) alumni